36

Mycotic Infections

Stacey R. Rose, MD

Richard J. Hamill, MD

CANDIDIASIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Common normal flora but opportunistic pathogen.

Common normal flora but opportunistic pathogen.

Typically mucosal disease, particularly vaginitis and oral thrush/esophagitis.

Typically mucosal disease, particularly vaginitis and oral thrush/esophagitis.

Persistent, unexplained oral or vaginal candidiasis: check for HIV or diabetes mellitus.

Persistent, unexplained oral or vaginal candidiasis: check for HIV or diabetes mellitus.

(1,3)-Beta-D-glucan results may be positive in candidemia even when blood cultures are negative.

(1,3)-Beta-D-glucan results may be positive in candidemia even when blood cultures are negative.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Candida albicans can be cultured from the mouth, vagina, and feces of most people. Cutaneous and oral lesions are discussed in Chapters 6 and 8, respectively. Cellular immunodeficiency predisposes to mucocutaneous disease. When no other underlying cause is found, persistent oral or vaginal candidiasis should arouse a suspicion for HIV infection or diabetes. The risk factors for invasive candidiasis include prolonged neutropenia, recent abdominal surgery, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, kidney disease, and the presence of intravascular catheters (especially when providing total parenteral nutrition).

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Mucosal Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis occurs in an estimated 75% of women during their lifetime. Risk factors include pregnancy, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment, corticosteroid use, and HIV infection. Symptoms include acute vulvar pruritus, burning vaginal discharge, and dyspareunia.

Esophageal involvement is the most frequent type of significant mucosal disease. Presenting symptoms include substernal odynophagia, gastroesophageal reflux, or nausea without substernal pain. Oral candidiasis, though often associated, is not invariably present. Diagnosis is best confirmed by endoscopy with biopsy and culture.

B. Candidal Funguria

Most cases of candidal funguria are asymptomatic and represent specimen contamination or bladder colonization. However, symptoms and signs of true Candida urinary tract infections are indistinguishable from bacterial urinary tract infections and can include urgency, hesitancy, fever, chills, or flank pain.

C. Invasive Candidiasis

Invasive candidiasis can be (1) candidemia (bloodstream infection) without deep-seated infection; (2) candidemia with deep-seated infection (typically eyes, kidney, or abdomen); and (3) deep-seated candidiasis in the absence of bloodstream infection (ie, hepatosplenic candidiasis). Varying ratios of these clinical entities depends on the predominating risk factors for affected patients (ie, neutropenia, indwelling vascular catheters, postsurgical).

The clinical presentation of candidemia varies from minimal fever to septic shock that can resemble a severe bacterial infection. The diagnosis of invasive Candida infection is challenging, since Candida species are often isolated from mucosal sites in the absence of invasive disease while blood cultures are positive only 50% of the time in invasive infection. Consecutively positive (1,3)-beta-D-glucan results may be used to guide empiric therapy in high-risk patients even in the absence of positive blood cultures.

Hepatosplenic candidiasis can occur following prolonged neutropenia in patients with underlying hematologic cancers, but this entity is less common in the era of widespread antifungal prophylaxis. Typically, fever and variable abdominal pain present weeks after chemotherapy, when neutrophil counts have recovered. Blood cultures are generally negative.

D. Candidal Endocarditis

Candidal endocarditis is a rare infection affecting patients with prosthetic heart valves or prolonged candidemia, such as with indwelling catheters. The diagnosis is established definitively by culturing Candida from vegetations at the time of valve replacement.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Mucosal Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis can be treated with topical or oral azoles. A single 150-mg oral dose of fluconazole is equivalent to topical treatments with better patient acceptance. Topical azole preparations include clotrimazole, 100-mg vaginal tablet for 7 days, or miconazole, 200-mg vaginal suppository for 3 days. Disease recurrence is common but can be decreased with weekly oral fluconazole therapy (150 mg weekly). Vulvovaginal candidiasis caused by non-albicans strains (eg, Candida glabrata) is increasingly recognized and may require alternative therapies (such as intravaginal boric acid) in the setting of azole resistance.

Treatment of esophageal candidiasis depends on the severity of disease. If patients are able to swallow and take adequate amounts of fluid orally, fluconazole, 200–400 mg daily for 14–21 days, is recommended. Patients who are unable to tolerate oral therapy should receive intravenous fluconazole, 400 mg daily, or an echinocandin. Options for patients with fluconazole-refractory disease include oral itraconazole solution, 200 mg daily; oral or intravenous voriconazole, 200 mg twice daily; or an intravenous echinocandin (caspofungin, 70 mg loading dose, then 50 mg/day; anidulafungin, 200 mg/day; or intravenous micafungin, 150 mg/day). Posaconazole tablets, 300 mg/day, may also be considered for fluconazole-refractory disease. Relapse is common with all agents when there is underlying HIV infection without adequate immune reconstitution.

B. Candidal Funguria

Candidal funguria frequently resolves with discontinuance of antibiotics or removal of bladder catheters. Clinical benefit from treatment of asymptomatic candiduria has not been demonstrated, but persistent funguria should raise the suspicion of invasive infection. When symptomatic funguria persists, oral fluconazole, 200 mg/day for 7–14 days, can be used.

C. Invasive Candidiasis

The 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for management of candidemia recommend an intravenous echinocandin as first-line therapy (ie, caspofungin (70 mg once, then 50 mg daily), micafungin (100 mg daily), or anidulafungin (200 mg once, then 100 mg daily). Intravenous or oral fluconazole (800 mg once, then 400 mg daily) is an acceptable alternative for less critically ill patients without recent azole exposure.

Therapy for candidemia should be continued for 2 weeks after the last positive blood culture and resolution of symptoms and signs of infection. A dilated fundoscopic examination is recommended for patients with candidemia to exclude endophthalmitis and repeat blood cultures should be drawn to demonstrate organism clearance. Susceptibility testing is recommended on all bloodstream Candida isolates; once patients have become clinically stable, parenteral therapy can be discontinued and treatment can be completed with oral fluconazole, 400 mg daily for susceptible isolates. Removal or exchange of intravascular catheters is recommended for patients with candidemia in whom the catheter is the suspected source of infection. Hepatosplenic candidiasis requires treatment until lesions have resolved radiographically.

Non-albicans species of Candida account for over 50% of clinical bloodstream isolates and often have resistance patterns that are different from C albicans. An echinocandin is recommended for treatment of C glabrata infection with transition to oral fluconazole or voriconazole reserved for patients whose isolates are known to be susceptible to these agents. For isolates with resistance to azoles and echinocandins, lipid formulation amphotericin B (3–5 mg/kg intravenously daily) may be used. C krusei is generally fluconazole-resistant and so should be treated with an alternative agent, such as an echinocandin or voriconazole. Cases of health care–associated infections due to multidrug-resistant Candida auris have been described from several countries, including the United States, with most cases having been treated with echinocandins plus environmental source control.

D. Candidal Endocarditis

Best results are achieved with a combination of medical and surgical therapy (valve replacement). Lipid formulation amphotericin B (3–5 mg/kg/day) or high-dose echinocandin (caspofungin 150 mg/day, micafungin 150 mg/day, or anidulafungin 200 mg/day) is recommended as initial therapy. Step-down or long-term suppressive therapy for nonsurgical candidates may be done with fluconazole at 6–12 mg/kg/day for susceptible organisms.

E. Prevention of Invasive Candidiasis

In high-risk patients undergoing induction chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, or liver transplantation, prophylaxis with antifungal agents has been shown to prevent invasive fungal infections, although the effect on mortality and the preferred agent remain debated. Although the isolation of Candida species from mucosal sites raises the possibility of invasive candidiasis among critically ill patients, trials of empiric antifungal agents in such situations have not shown clear clinical benefit.

Bradley SF. JAMA patient page. Candida auris infection. JAMA. 2019 Oct 15;322(15):1526. [PMID: 31613347]

Pappas PG et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 15;62(4):e1–50. [PMID: 26679628]

Pristov KE et al. Resistance of Candida to azoles and echinocandins worldwide. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019 Jul;25(7):792–8. [PMID: 30965100]

Warris A et al; EUROCANDY Study Group. Etiology and outcome of candidemia in neonates and children in Europe: an 11-year multinational retrospective study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020 Feb;39(2):114–20. [PMID: 31725552]

HISTOPLASMOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Exposure to bird and bat droppings; common along river valleys (especially the Ohio River and the Mississippi River valleys).

Exposure to bird and bat droppings; common along river valleys (especially the Ohio River and the Mississippi River valleys).

Most patients asymptomatic; respiratory illness most frequent clinical problem.

Most patients asymptomatic; respiratory illness most frequent clinical problem.

Disseminated disease common in AIDS or other immunosuppressed states; poor prognosis.

Disseminated disease common in AIDS or other immunosuppressed states; poor prognosis.

Blood and bone marrow cultures and urine polysaccharide antigen are useful in diagnosis of disseminated disease.

Blood and bone marrow cultures and urine polysaccharide antigen are useful in diagnosis of disseminated disease.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that has been isolated from soil contaminated with bird or bat droppings in endemic areas (central and eastern United States, eastern Canada, Mexico, Central America, South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia). Infection presumably takes place by inhalation of conidia. These convert into small budding cells that are engulfed by phagocytes in the lungs. The organism proliferates and undergoes lymphohematogenous spread to other organs.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Most cases of histoplasmosis are asymptomatic or mild and thus go unrecognized. Past infection is recognized by pulmonary and splenic calcification noted on incidental radiographs. Symptomatic infection may present with mild influenza-like illness, often lasting 1–4 days. Moderately severe infections are frequently diagnosed as atypical pneumonia. These patients have fever, cough, and mild central chest pain lasting 5–15 days.

Clinically evident infections occur in several forms: (1) Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis frequently occurs in epidemics, often when soil containing infected bird or bat droppings is disturbed. Clinical manifestations can vary from a mild influenza-like illness to severe pneumonia. The illness may last from 1 week to 6 months but is almost never fatal. (2) Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis is commonly seen in patients with underlying HIV infection (with CD4 cell counts usually less than 100 cells/mcL) or other conditions of impaired cellular immunity. Disseminated histoplasmosis has also been reported in patients from endemic areas taking tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors. It is characterized by fever and multiple organ system involvement. Chest radiographs may show a miliary pattern. Presentation may be fulminant, simulating septic shock, with death ensuing rapidly unless treatment is provided. Symptoms usually consist of fever, dyspnea, cough, loss of weight, and prostration. Ulcers of the mucous membranes of the oropharynx may be present. The liver and spleen are nearly always enlarged, and all the organs of the body are involved, particularly the adrenal glands; this results in adrenal insufficiency in about 50% of patients. Gastrointestinal involvement may mimic inflammatory bowel disease. Central nervous system (CNS) invasion occurs in 5–10% of individuals with disseminated disease. (3) Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis is usually seen in older patients who have underlying chronic lung disease. Chest radiographs show various lesions including complex apical cavities, infiltrates, and nodules. (4) Complications of pulmonary histoplasmosis include granulomatous mediastinitis characterized by persistently enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes and fibrosing mediastinitis in which an excessive fibrotic response to Histoplasma infection results in compromise of pulmonary vascular structures.

B. Laboratory Findings

Most patients with chronic pulmonary disease show anemia of chronic disease. Bone marrow involvement with pancytopenia may be prominent in disseminated forms. Marked lactate dehydrogenase (LD) and ferritin elevations are also common, as are mild elevations of serum aspartate aminotransferase.

With pulmonary involvement, sputum culture is rarely positive except in chronic disease; antigen testing of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid may be helpful in acute disease. The combination of urine and serum polysaccharide antigen assays has an 83% sensitivity for the diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.

Blood or bone marrow cultures from immunocompromised patients with acute disseminated disease are positive more than 80% of the time, but may take several weeks for growth. The urine antigen assay has a sensitivity of greater than 90% for disseminated disease in immunocompromised patients and a declining titer can be used to follow response to therapy. Diagnosis of CNS disease requires antigen and antibody testing of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum as well as urine antigen testing.

Treatment

Treatment

For progressive localized disease and for mild to moderately severe nonmeningeal disseminated disease in immunocompetent or immunocompromised patients, itraconazole, 200–400 mg/day orally divided into two doses, is the treatment of choice with an overall response rate of approximately 80% (Table 36–1). The oral solution is better absorbed than the capsule formulation, which requires gastric acid for absorption. Therapeutic drug monitoring of itraconazole levels should be performed to assess adequacy of drug absorption. Duration of therapy ranges from weeks to several months depending on the severity of illness. Intravenous liposomal amphotericin B, 3 mg/kg/day, is used in patients with more severe disseminated disease and meningitis. Patients with AIDS-related histoplasmosis require lifelong suppressive therapy with itraconazole, 200 mg/day orally, although secondary prophylaxis may be discontinued if immune reconstitution occurs in response to antiretroviral therapy. Criteria for discontinuing secondary prophylaxis include 1 year of successful antifungal therapy and a CD4 cell count of greater than 150 cells/mcL and 6 months or more of antiretroviral treatment (ART). There is no clear evidence that antifungal agents are of benefit for patients with fibrosing mediastinitis, although oral itraconazole is often used. Rituximab, in conjunction with corticosteroids, may contribute to slowing progression of the fibrosing process and provide some clinical benefit. Reported outcomes in patients with fibrosing mediastinitis treated with either surgical procedures or nonsurgical intravascular interventions appear to be relatively good in the short term.

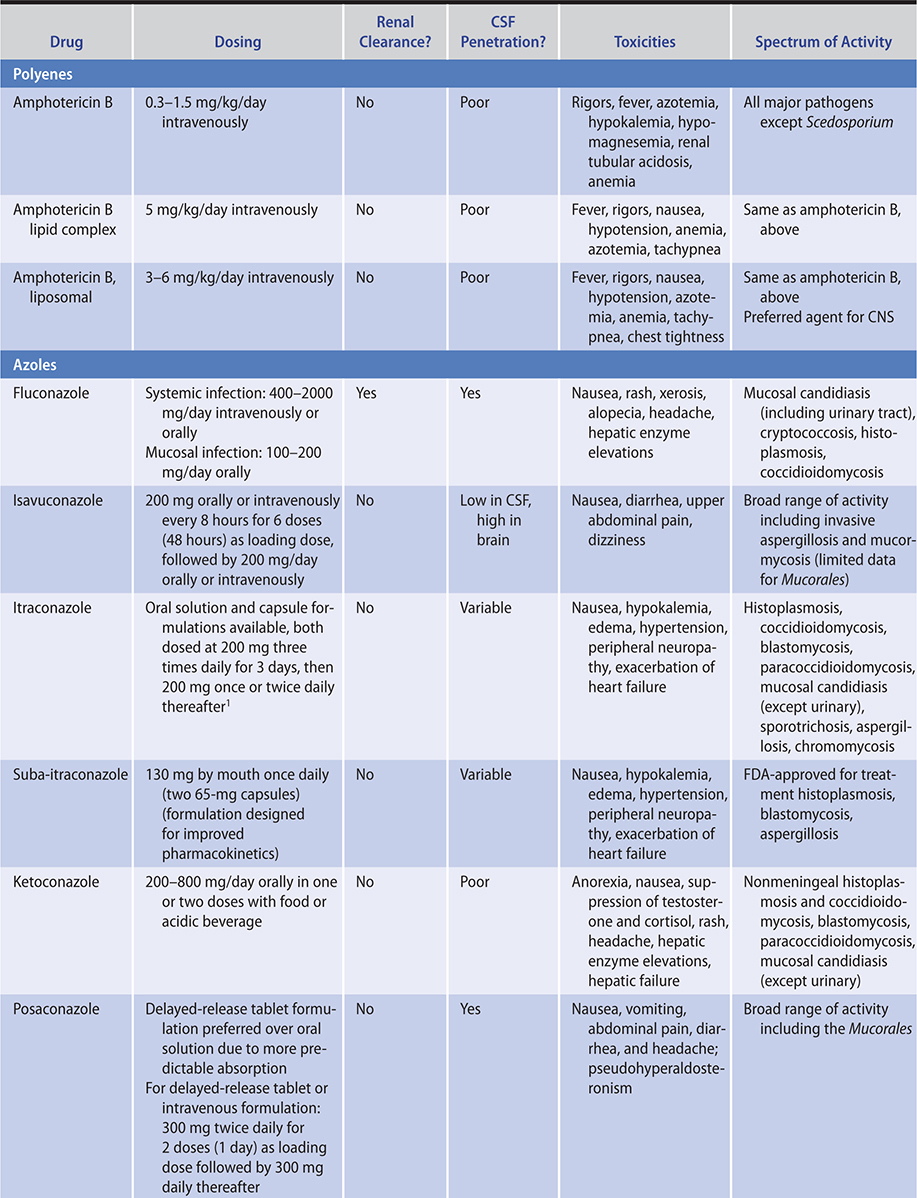

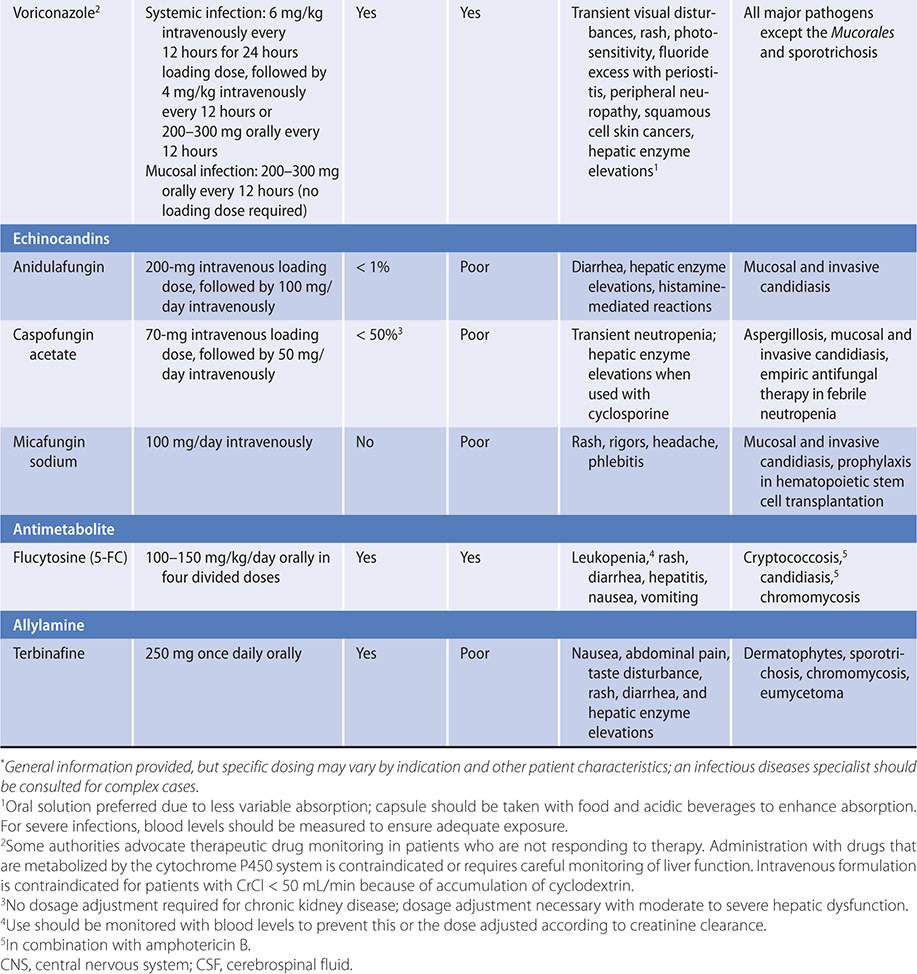

Table 36–1. Agents for systemic mycoses.*

Azar MM et al. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017 Sep; 38(3):403–15. [PMID: 28797485]

Flora AS et al. Rituximab to treat fibrosing mediastinitis-associated recurrent hemoptysis. Am J Ther. 2019 Jul 12. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 31356339]

Staffolani S et al. Acute histoplasmosis in immunocompetent travelers: a systematic review of literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2018 Dec 18;18(1):673. [PMID: 30563472]

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Acute infection: influenza-like illness, fever, backache, headache, fatigue, and cough. Erythema nodosum common.

Acute infection: influenza-like illness, fever, backache, headache, fatigue, and cough. Erythema nodosum common.

Dissemination may result in meningitis, bony lesions, or skin and soft tissue abscesses; common opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS.

Dissemination may result in meningitis, bony lesions, or skin and soft tissue abscesses; common opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS.

Chest radiograph findings vary from pneumonitis to cavitation.

Chest radiograph findings vary from pneumonitis to cavitation.

Serologic tests useful; large spherules containing endospores demonstrable in sputum or tissues.

Serologic tests useful; large spherules containing endospores demonstrable in sputum or tissues.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Coccidioidomycosis should be considered in the diagnosis of any obscure illness in a patient who has lived in or visited an endemic area. Infection results from the inhalation of arthroconidia of Coccidioides immitis or C posadasii; both organisms are molds that grow in soil in certain arid regions of the southwestern United States, in Mexico, and in Central and South America. Less than 1% of immunocompetent persons show dissemination, but among these patients, the mortality rate is high.

In patients with AIDS who reside in endemic areas, coccidioidomycosis is a common opportunistic infection. In these patients, disease manifestations range from focal pulmonary infiltrates to widespread miliary disease with multiple organ involvement and meningitis; severity is inversely related to the extent of control of the HIV infection.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Symptoms of primary coccidioidomycosis occur in about 40% of infections. Symptom onset (after an incubation period of 10–30 days) is usually that of a respiratory tract illness with fever and occasionally chills. Coccidioidomycosis is a common, frequently unrecognized, etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in endemic areas.

Erythema nodosum may appear 2–20 days after onset of symptoms. Persistent pulmonary lesions, varying from cavities and abscesses to parenchymal nodular densities or bronchiectasis, occur in about 5% of diagnosed cases.

Disseminated disease occurs in about 0.1% of white and 1% of nonwhite patients. Filipinos and blacks are especially susceptible, as are pregnant women of all races. Any organ may be involved. Pulmonary findings usually become more pronounced, with mediastinal lymph node enlargement, cough, and increased sputum production. Lung abscesses may rupture into the pleural space, producing an empyema. Complicated skin and bone infections may develop. Fungemia may occur and is characterized clinically by a diffuse miliary pattern on chest radiograph and by early death. The course may be particularly rapid in immunosuppressed patients. Clinicians caring for immunosuppressed patients in endemic areas need to consider that patients may be latently infected.

Meningitis occurs in 30–50% of cases of dissemination and may result in chronic basilar meningitis. Subcutaneous abscesses and verrucous skin lesions are especially common in fulminating cases. Patients with AIDS with disseminated disease have a higher incidence of miliary infiltrates, lymphadenopathy, and meningitis, but skin lesions are uncommon.

B. Laboratory Findings

In primary coccidioidomycosis, there may be moderate leukocytosis and eosinophilia. Serologic testing is useful for both diagnosis and prognosis. The immunodiffusion tube precipitin test and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detect IgM antibodies and are both useful for diagnosis early in the disease process. A persistently rising IgG complement fixation titer (1:16 or more) is suggestive of disseminated disease; in addition, immunodiffusion complement fixation titers can be used to assess the adequacy of therapy. Serum complement fixation titers may be low when there is meningitis but no other disseminated disease. In patients with HIV-related coccidioidomycosis, the false-negative rate may be as high as 30%. Blood cultures are rarely positive.

Patients in whom coccidioidomycosis is diagnosed should undergo evaluation for meningeal involvement when CNS symptoms or neurologic signs are present. Spinal fluid findings include increased cell count with lymphocytosis and reduced glucose. Spinal fluid culture is positive in approximately 30% of meningitis cases. Demonstrable complement-fixing antibodies in spinal fluid are diagnostic of coccidioidal meningitis. These are found in over 90% of cases; Coccidioides antigen or (1,3)-beta-D-glucan testing may augment (not replace) CSF antibody testing.

C. Imaging

Radiographic findings vary, but patchy, nodular, and lobar upper lobe pulmonary infiltrates are most common. Hilar lymphadenopathy may be visible and is seen in localized disease; mediastinal lymphadenopathy suggests dissemination. There may be pleural effusions and lytic lesions in bone with accompanying complicated soft tissue collections.

Treatment

Treatment

General symptomatic therapy should be provided as needed for disease limited to the chest with no evidence of progression. Itraconazole (400 mg orally daily divided into two doses) or fluconazole (200–400 mg or higher orally once or twice daily) should be given for disease in the chest, bones, and soft tissues; however, therapy must be continued for 6 months or longer after the disease is inactive to prevent relapse (Table 36–1). Response to therapy should be monitored by following the clinical response and progressive decrease in serum complement fixation titers.

For progressive pulmonary or extrapulmonary disease, liposomal amphotericin B intravenously should be given, although oral azoles may be used for mild cases. Duration of therapy is determined by a declining complement fixation titer and a favorable clinical response. For meningitis, treatment usually is with high-dose oral fluconazole (400–1200 mg/day), although lumbar or cisternal intrathecal administration of amphotericin B daily in increasing doses up to 1–1.5 mg/day is used initially by some experienced clinicians or in cases refractory to fluconazole. Systemic therapy with liposomal amphotericin B, 3–5 mg/kg/day intravenously, is generally given concurrently with intrathecal therapy, but is not sufficient alone for the treatment of meningeal disease. Once the patient is clinically stable, oral therapy with an azole, usually with fluconazole (400 mg daily) and given lifelong, is the recommended alternative to intrathecal amphotericin B therapy.

Surgical drainage is necessary for management of soft tissue abscesses, necrotic bone, and complicated pulmonary disease (eg, rupture of coccidioidal cavity).

Prognosis

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with limited disease is good. Serial complement fixation titers should be performed after therapy for patients with coccidioidomycosis; rising titers warrant reinstitution of therapy because relapse is likely. Late CNS complications of adequately treated meningitis include cerebral vasculitis with stroke and hydrocephalus that may require shunting. There may be a benefit from short-term systemic corticosteroids following cerebrovascular events associated with coccidioides meningitis. Disseminated and meningeal forms still have mortality rates exceeding 50% in the absence of therapy.

Galgiani JN et al. Treatment for early, uncomplicated coccidioidomycosis: what is success? Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Apr 15;70(9):2008–12. [PMID: 31544210]

Thompson GR 3rd et al. Current concepts and future directions in the pharmacology and treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Med Mycol. 2019 Feb 1;57(Suppl 1):S76–84. [PMID: 30690601]

PNEUMOCYSTOSIS (Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia)

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Fever, dyspnea, dry cough, hypoxia.

Fever, dyspnea, dry cough, hypoxia.

Often only slight lung physical findings.

Often only slight lung physical findings.

Chest radiograph: diffuse interstitial disease or normal.

Chest radiograph: diffuse interstitial disease or normal.

P jirovecii in sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, or lung tissue; PCR of bronchoalveolar lavage; (1,3)-beta-D-glucan in blood.

P jirovecii in sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, or lung tissue; PCR of bronchoalveolar lavage; (1,3)-beta-D-glucan in blood.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Pneumocystis jirovecii, the Pneumocystis species that affects humans, is distributed worldwide. Although symptomatic P jirovecii disease is rare in the general population, serologic evidence indicates that asymptomatic infections have occurred in most persons by a young age. Accumulating evidence suggests airborne transmission. Following asymptomatic primary infection, latent and presumably inactive organisms are sparsely distributed in the alveoli. De novo infection and reactivation of latent disease likely contribute to the mechanism of symptomatic disease in older children and adults.

The overt infection is a subacute interstitial pneumonia that occurs among older children and adults who have an abnormal or altered cellular immunity, either due to an underlying disease process (eg, cancer, malnutrition, stem cell or organ transplantation or, most commonly, AIDS) or due to treatment with immunosuppressive medications (eg, corticosteroids or cytotoxic agents).

Pneumocystis pneumonia occurs in up to 80% of AIDS patients not receiving prophylaxis and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Its incidence increases in direct proportion to the fall in CD4 cells, with most cases occurring at CD4 cell counts less than 200/mcL. In non-AIDS patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, symptoms frequently begin after corticosteroids have been tapered or discontinued.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Findings are usually limited to the pulmonary parenchyma. Onset may be subacute, characterized by dyspnea on exertion and nonproductive cough. Pulmonary physical findings may be slight and disproportionate to the degree of illness and the radiologic findings; some patients have bibasilar crackles. Without treatment, the course is usually one of rapid deterioration and death. Adult patients may present with spontaneous pneumothorax, usually in patients with previous episodes or those receiving aerosolized pentamidine prophylaxis. Patients with AIDS will usually have other evidence of HIV-associated disease, including fever, fatigue, and weight loss, for weeks or months preceding the illness.

B. Laboratory Findings

Arterial blood gas determinations usually show hypoxemia with hypocapnia but may be normal; however, rapid desaturation occurs if patients exercise before samples are drawn. Serologic tests are not helpful in diagnosis; measurement of serum (1,3)-beta-D-glucan levels has good sensitivity, although specificity is compromised by being positive in other fungal infections. The organism cannot be cultured, and definitive diagnosis depends on morphologic demonstration of the organisms in respiratory specimens using specific stains, such as immunofluorescence. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of bronchoalveolar lavage is overly sensitive in that the test can be positive in colonized, noninfected persons; quantitative values may help with identifying infected patients, although precise cutoffs have not been established. A negative PCR from bronchoalveolar lavage rules out disease. Open lung biopsy and needle lung biopsy are infrequently required but may aid in diagnosing a granulomatous form of Pneumocystis pneumonia.

C. Imaging

Chest radiographs most often show diffuse “interstitial” infiltration, which may be heterogeneous, miliary, or patchy early in infection. There may also be diffuse or focal consolidation, cystic changes, nodules, or cavitation within nodules. Pleural effusions are not seen. About 5–10% of patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia have normal chest films. High-resolution chest CT scans may be quite suggestive of P jirovecii pneumonia, helping distinguish it from other causes of pneumonia.

Treatment

Treatment

It is appropriate to start empiric therapy for P jirovecii pneumonia if the disease is suspected clinically; however, in both AIDS patients and non-AIDS patients with mild to moderately severe disease, continued treatment should be based on a proved diagnosis because of clinical overlap with other infections, the toxicity of therapy, and the possible coexistence of other infectious organisms. Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) is the preferred agent because of its low cost and excellent bioavailability in both AIDS patients and non-AIDS patients with mild to moderately severe disease. Patients suffering from nausea and vomiting or intractable diarrhea should be given intravenous TMP-SMZ until they can tolerate the oral formulation. The best-studied second-line option is a combination of primaquine and clindamycin, although dapsone/trimethoprim, pentamidine, and atovaquone have been used. Therapy should be continued with the selected medication for at least 5–10 days before considering changing agents, as fever, tachypnea, and pulmonary infiltrates persist for 4–6 days after starting treatment. Some patients have a transient worsening of their disease during the first 3–5 days, which may be related to an inflammatory response secondary to the presence of dead or dying organisms. Early addition of corticosteroids may attenuate this response (see below). Some clinicians prefer to treat episodes of AIDS-associated Pneumocystis pneumonia for 21 days rather than the usual 14 days recommended for non-AIDS cases.

A. Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole

There are strong data indicating that TMP-SMZ is the optimal first-line therapy for Pneumocystis pneumonia. The dosage of TMP/SMZ is 15–20 mg/kg/day (based on trimethoprim component) given orally or intravenously daily in three or four divided doses for 14–21 days. Patients with AIDS have a high frequency of hypersensitivity reactions (approaching 50%), which may include fever, rashes (sometimes severe), malaise, neutropenia, hepatitis, nephritis, thrombocytopenia, hyperkalemia, and hyperbilirubinemia.

B. Primaquine/Clindamycin

A meta-analysis suggested that primaquine, 15–30 mg orally daily, plus clindamycin, 600 mg three times orally daily, is the best second-line therapy with superior results when compared with pentamidine. Primaquine may cause hemolytic anemia in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.

C. Pentamidine Isethionate

The use of pentamidine has decreased as alternative agents have been studied. This medication is administered intravenously (preferred) or intramuscularly as a single dose of 3–4 mg (salt)/kg/day for 14–21 days. Pentamidine causes side effects in nearly 50% of patients. Hypoglycemia (often clinically inapparent), hyperglycemia, hyponatremia, and delayed nephrotoxicity with azotemia may occur.

D. Atovaquone

Atovaquone is FDA approved for patients with mild to moderate disease who cannot tolerate TMP-SMZ or pentamidine, but failure is reported in 15–30% of cases. Mild side effects are common, but no serious reactions have been reported. The dosage is 750 mg orally two times daily for 21 days. Atovaquone should be administered with a fatty meal.

E. Other Medications

Trimethoprim, 15 mg/kg/day in three divided doses daily, plus dapsone, 100 mg/day, is an alternative oral regimen for mild to moderate disease or for continuation of therapy after intravenous therapy is no longer needed.

F. Prednisone

Based on studies done in patients with AIDS, prednisone is given for moderate to severe pneumonia (when Pao2 on admission is less than 70 mm Hg or oxygen saturation is less than 90%) in conjunction with antimicrobials. The addition of corticosteroids in such patients is associated with significant reduction in morbidity and mortality; administration of adjunctive corticosteroids within 72 hours is preferred. The dosage of prednisone is 40 mg twice daily orally for 5 days, then 40 mg daily for 5 days, and then 20 mg daily until therapy is completed (total course, 21 days). The role of prednisone in non-AIDS patients is less clear, although observational studies suggest that adjunctive corticosteroids are associated with reduced mortality in non-AIDS patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia and severe hypoxia (Pao2 60 mm Hg or less).

Prevention

Prevention

Primary prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia in HIV-infected patients should be given to persons with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mcL, a CD4 percentage below 14%, or weight loss or oral candidiasis. Primary prophylaxis is also beneficial in patients with hematologic malignancy and transplant recipients, although the clinical characteristics of persons with these conditions who would benefit from Pneumocystis prophylaxis have not been clearly defined. Patients with a history of Pneumocystis pneumonia should receive secondary prophylaxis until they have had a durable virologic response to antiretroviral therapy and maintained a CD4 count of greater than 200 cells/mcL for at least 3–6 months.

Prognosis

Prognosis

In the absence of early and adequate treatment, the fatality rate for Pneumocystis pneumonia in immunodeficient persons is nearly 100%. Early treatment reduces the mortality rate to ~10–20% in AIDS patients. The mortality rate in other immunodeficient patients is still 30–50%, probably because of failure to make a timely diagnosis. In immunodeficient patients who do not receive prophylaxis, recurrences are common (30% in AIDS).

Inoue N et al. Adjunctive corticosteroids decreased the risk of mortality of non-HIV pneumocystis pneumonia. Int J Infect Dis. 2019 Feb;79:109–15. [PMID: 30529109]

Stern A et al. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV immunocompromised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Oct 1;(10):CD005590. [PMID: 25269391]

White PL et al. Therapy and management of Pneumocystis jirovecii infection. J Fungi (Basel). 2018 Nov 22;4(4):E127. [PMID: 30469526]

CRYPTOCOCCOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Predisposing factors: chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies, Hodgkin lymphoma, corticosteroid therapy, structural lung diseases, transplant recipients, TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy, and AIDS.

Predisposing factors: chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies, Hodgkin lymphoma, corticosteroid therapy, structural lung diseases, transplant recipients, TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy, and AIDS.

Most common cause of fungal meningitis.

Most common cause of fungal meningitis.

Headache, abnormal mental status; meningismus seen occasionally, though rarely in patients with AIDS.

Headache, abnormal mental status; meningismus seen occasionally, though rarely in patients with AIDS.

Demonstration of capsular polysaccharide antigen or positive culture in CSF is diagnostic.

Demonstration of capsular polysaccharide antigen or positive culture in CSF is diagnostic.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Cryptococcosis is mainly caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, an encapsulated budding yeast that has been found worldwide in soil and on dried pigeon dung. Cryptococcus gattii is a closely related species that also causes disease in humans, although C gattii may affect more ostensibly immunocompetent persons. It is a major cause of cryptococcosis in the Pacific northwestern region of the United States and may result in more severe disease than C neoformans.

Infections are acquired by inhalation. In the lung, the infection may remain localized, heal, or disseminate. Clinically apparent cryptococcal pneumonia rarely develops in immunocompetent persons. Progressive lung disease and dissemination most often occur in the setting of cellular immunodeficiency, including underlying hematologic malignancies under treatment, Hodgkin lymphoma, long-term corticosteroid therapy, solid-organ transplant, TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy, or HIV infection.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Pulmonary disease ranges from simple nodules to widespread infiltrates leading to respiratory failure. Disseminated disease may involve any organ, but CNS disease predominates. Headache is usually the first symptom of meningitis. Confusion and other mental status changes as well as cranial nerve abnormalities, nausea, and vomiting may be seen as the disease progresses. Nuchal rigidity and meningeal signs occur about 50% of the time but are uncommon in patients with AIDS. Communicating hydrocephalus may complicate the course. C gattii infection frequently presents with respiratory symptoms along with neurologic signs caused by space-occupying lesions in the CNS. Primary C neoformans infection of the skin may mimic bacterial cellulitis, especially in persons receiving immunosuppressive therapy such as corticosteroids. The immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which is paradoxical clinical worsening associated with improved immunologic status, has been reported in HIV-positive and transplant patients with cryptococcosis, as well as non-AIDS patient being treated for C gattii infection.

B. Laboratory Findings

Respiratory tract disease is diagnosed by culture of respiratory secretions or pleural fluid. For suspected meningeal disease, lumbar puncture is the preferred diagnostic procedure. Spinal fluid findings include increased opening pressure, variable pleocytosis, increased protein, and decreased glucose, though as many as 50% of AIDS patients have no pleocytosis. Gram stain of the CSF usually reveals budding, encapsulated fungi. Cryptococcal capsular antigen in CSF and culture together establish the diagnosis over 90% of the time. Patients with AIDS often have the antigen in both CSF and serum, and extrameningeal disease (lungs, blood, urinary tract) is common. In patients with AIDS, the serum cryptococcal antigen is also a sensitive screening test for meningitis, being positive in over 95% of cases. MRI is more sensitive than CT in finding CNS abnormalities such as cryptococcomas. Antigen testing by lateral flow assay has improved sensitivity and specificity over the conventional latex agglutination test and can provide more rapid diagnostic results.

Treatment

Treatment

Because of decreased efficacy, initial therapy with an azole alone is not recommended for treatment of acute cryptococcal meningitis. Liposomal amphotericin B, 3–4 mg/kg/day intravenously for 14 days, is the preferred agent for induction therapy, followed by an additional 8 weeks of fluconazole, 400 mg/day orally for consolidation (Table 36–1). This regimen is quite effective, achieving clinical responses and CSF sterilization in about 70% of patients. The addition of flucytosine has been associated with improved survival, but toxicity is common. Flucytosine is administered orally at a dose of 100 mg/kg/day divided into four equal doses and given every 6 hours. Hematologic parameters should be closely monitored during flucytosine therapy, and it is important to adjust the dose for any decreases in kidney function. Fluconazole (800–1200 mg orally daily) may be given with amphotericin B when flucytosine is not available or patients cannot tolerate it. Frequent, repeated lumbar punctures or ventricular shunting should be performed to relieve high CSF pressures or if hydrocephalus is a complication. Corticosteroids should not be used. Failure to adequately relieve raised intracranial pressure is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. The end points for amphotericin B therapy and for switching to maintenance with oral fluconazole are a favorable clinical response (decrease in temperature; improvement in headache, nausea, vomiting, and Mini-Mental State Examination scores), improvement in CSF biochemical parameters and, most importantly, conversion of CSF culture to negative.

A similar approach is reasonable for patients with cryptococcal meningitis in the absence of AIDS, though the mortality rate is higher. Therapy is generally continued until CSF cultures become negative. Maintenance antifungal therapy is important after treatment of an acute episode in AIDS-related cases, since otherwise the rate of relapse is greater than 50%. Fluconazole, 200 mg/day orally, is the maintenance therapy of choice, decreasing the relapse rate approximately tenfold compared with placebo and threefold compared with weekly amphotericin B in patients whose CSF has been sterilized by the induction therapy. After successful therapy of cryptococcal meningitis, it is possible to discontinue secondary prophylaxis with fluconazole in individuals with AIDS who have had a satisfactory response to antiretroviral therapy (eg, CD4 cell count greater than 100–200 cells/mcL for at least 6 months). Published guidelines suggest that 6–12 months of fluconazole can be used as maintenance therapy in patients without AIDS following successful treatment of the acute illness.

Prognosis

Prognosis

Factors that indicate a poor prognosis include the activity of the predisposing conditions, older age, organ failure, lack of spinal fluid pleocytosis, high initial antigen titer in either serum or CSF, decreased mental status, increased intracranial pressure, and the presence of disease outside the nervous system.

Beardsley J et al. Central nervous system cryptococcal infections in non-HIV infected patients. J Fungi (Basel). 2019 Aug 2;5(3):E71. [PMID: 31382367]

Setianingrum F et al. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: a review of pathobiology and clinical aspects. Med Mycol. 2019 Feb 1;57(2):133–50. [PMID: 30329097]

Skipper C et al. Diagnosis and management of central nervous system cryptococcal infections in HIV-infected adults. J Fungi (Basel). 2019 Jul 19;5(3):E65. [PMID: 31330959]

ASPERGILLOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Most common cause of non-candidal invasive fungal infection in transplant recipients and in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Most common cause of non-candidal invasive fungal infection in transplant recipients and in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Predisposing factors for invasive disease: leukemia, bone marrow or organ transplantation, corticosteroid use, advanced AIDS.

Predisposing factors for invasive disease: leukemia, bone marrow or organ transplantation, corticosteroid use, advanced AIDS.

Pulmonary, sinus, and CNS are most common disease sites.

Pulmonary, sinus, and CNS are most common disease sites.

Detection of galactomannan in serum or other body fluids is useful for early diagnosis in at-risk patients.

Detection of galactomannan in serum or other body fluids is useful for early diagnosis in at-risk patients.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Aspergillus fumigatus is the usual cause of aspergillosis, though many species of Aspergillus may cause a wide spectrum of disease. The lungs, sinuses, and brain are the organs most often involved. Clinical illness results either from an aberrant immunologic response or tissue invasion.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

1. Allergic forms of aspergillosis—Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) occurs in patients with preexisting asthma or cystic fibrosis. Patients develop worsening bronchospasm and fleeting pulmonary infiltrates accompanied by eosinophilia, high levels of IgE, and IgG Aspergillus precipitins in the blood. Allergic aspergillus sinusitis produces a chronic sinus inflammation characterized by eosinophilic mucus and noninvasive hyphal elements.

2. Chronic aspergillosis—Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis produces a spectrum of disease that usually occurs when there is preexisting lung damage but not significant immunocompromise. Disease manifestations range from aspergillomas that develop in a lung cavity to chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis in which the majority of lung tissue is replaced with fibrosis. Long-standing (longer than 3 months) pulmonary and systemic symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath, weight loss, and malaise are common.

3. Invasive aspergillosis—Invasive aspergillosis most commonly occurs in profoundly immunodeficient patients, such as those who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or have prolonged, severe neutropenia, but it can occur among critically ill immunocompetent patients as well. Specific risk factors in patients who have undergone a hematopoietic stem cell transplant include cytopenias, corticosteroid use, iron overload, cytomegalovirus disease, and graft-versus-host disease. Pulmonary disease is most common, with patchy infiltration leading to a severe necrotizing pneumonia. Invasive sinus disease also occurs. At any time, there may be hematogenous dissemination to the CNS, skin, and other organs. Early diagnosis and reversal of any correctable immunosuppression are essential.

B. Laboratory Findings

There is eosinophilia, high levels of total IgE, and IgE and IgG specific for Aspergillus in the blood of patients with ABPA.

For invasive aspergillosis, definitive diagnosis requires demonstration of Aspergillus in tissue or culture from a sterile site; however, given the morbidity of the disease and the low yield of culture, clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion and use a combination of host, radiologic, and mycologic criteria to yield a probable diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in at-risk patients. Indirect diagnostic assays include detection of galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or serum or serum assays for (1,3)-beta-D-glucan (though the latter is not specific for Aspergillus); the diagnostic utility of Aspergillus DNA by PCR is debated. To improve the reliability of galactomannan testing, multiple determinations should be done, though sensitivity is decreased in patients receiving anti-mold prophylaxis (ie, voriconazole or posaconazole). Isolation of Aspergillus from pulmonary secretions does not necessarily imply invasive disease, although its positive predictive value increases with more advanced immunosuppression. Clinical suspicion for invasive aspergillosis should prompt CT scanning of the chest, which may aid in early detection and help direct additional diagnostic procedures. Common radiologic findings include nodules; wedge-shaped infarcts; or a characteristic “halo sign,” a zone of diminution of ground glass around a consolidation.

Prevention

Prevention

The high mortality rate and difficulty in diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis often lead clinicians to institute prophylactic therapy for patients with profound immunosuppression. The best-studied agents include posaconazole (300 mg orally daily) and voriconazole (200 mg orally twice daily), although patient and agent selection criteria remain undefined. Widespread use of broad-spectrum azoles raises concern for development of breakthrough invasive disease by highly resistant fungi.

Treatment

Treatment

1. Allergic forms of aspergillosis—Itraconazole is the best studied agent for the treatment of allergic aspergillus sinusitis with topical corticosteroids being the cornerstone of therapy for ongoing care. For acute exacerbations of ABPA, oral prednisone is begun at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day and then tapered slowly over several months. Itraconazole at a dose of 200 mg orally daily for 16 weeks appears to improve pulmonary function and decrease corticosteroid requirements in these patients; voriconazole is an alternative agent.

2. Chronic aspergillosis—The most effective therapy for symptomatic aspergilloma is surgical resection. Other forms of chronic aspergillosis are generally treated with at least 4–6 months of oral azole therapy (itraconazole 200 mg twice daily, voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, or posaconazole 300 mg daily); observational data suggests voriconazole may be superior to itraconazole for maintenance therapy.

3. Invasive aspergillosis—The 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines consider voriconazole (6 mg/kg intravenously twice on day 1 and then 4 mg/kg every 12 hours thereafter) as optimal therapy for invasive aspergillosis. However, the 2017 European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, the European Confederation of Medical Mycology, and the European Respiratory Society (ESCMID-ECMM-ERS) joint clinical guidelines indicate either isavuconazole (200 mg intravenously every 8 hours for six doses, then 200 mg daily) or voriconazole as first-line therapy. These guidelines are based on data from a randomized controlled trial demonstrating noninferiority of isavuconazole in terms of treatment outcomes and fewer adverse events. Another randomized controlled trial did not find an overall benefit of adding anidulafungin (200 mg on day 1, then 100 mg daily) to voriconazole, but among patients in whom galactomannan was detected, those who received combination therapy had better outcomes. Other alternatives include a lipid formulation of amphotericin B (3–5 mg/kg/day), caspofungin (70 mg intravenously on day 1, then 50 mg/day thereafter), micafungin (100–150 mg intravenously daily), and posaconazole oral tablets (300 mg twice daily on day 1 then 300 mg daily thereafter). Antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus isolates is recommended in patients who are unresponsive to therapy or with clinical suspicion for azole-resistance. Therapeutic drug monitoring should be considered for both voriconazole and posaconazole given variations in metabolism and absorption.

Surgical debridement is generally done for sinusitis, and can be useful for focal pulmonary lesions, especially for treatment of life-threatening hemoptysis and infections recalcitrant to medical therapy. The mortality rate of pulmonary or disseminated disease in the immunocompromised patient remains high, particularly in patients with refractory neutropenia.

Jenks JD et al. Treatment of aspergillosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018 Aug 19;4(3):E98. [PMID: 30126229]

Mellinghoff SC et al. Primary prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in patients with haematological malignancies: 2017 update of the recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Haematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol. 2018 Feb;97(2):197–207. [PMID: 29218389]

Patterson TF et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 15;63(4):e1–60. [PMID: 27365388]

Ullmann AJ et al. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018 May;24(Suppl 1):e1–38. [PMID: 29544767]

MUCORMYCOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Most common cause of non-Aspergillus invasive mold infection.

Most common cause of non-Aspergillus invasive mold infection.

Risk factors: uncontrolled diabetes, leukemia, transplant recipient, wound contamination by soil.

Risk factors: uncontrolled diabetes, leukemia, transplant recipient, wound contamination by soil.

Pulmonary, rhinocerebral, and skin are most common disease sites.

Pulmonary, rhinocerebral, and skin are most common disease sites.

Rapidly fatal without multidisciplinary interventions.

Rapidly fatal without multidisciplinary interventions.

General Considerations

General Considerations

The term “mucormycosis” is applied to opportunistic infections caused by members of the genera Rhizopus, Mucor, Lichtheimia (formerly Absidia), and Cunninghamella. Predisposing conditions include hematologic malignancy, stem cell transplantation, solid organ transplantation, diabetic ketoacidosis, chronic kidney disease, and treatment with desferoxamine, corticosteroids, or cytotoxic drugs.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Invasive disease of the sinuses, orbits, and the lungs may occur. Necrosis is common due to hyphal tissue invasion that may manifest as ulceration of the hard palate, nasal palate, or hemoptysis. Widely disseminated disease can occur. No biochemical assays aid in diagnosis, and blood cultures are unhelpful. Molecular identification (eg, PCR) from tissue and/or mass spectrometry-base detection of a panfungal serum disaccharide may be helpful in specialized centers. A reverse “halo sign” (focal area of ground glass diminution surrounded by a ring of consolidation) may be seen on chest CT. Biopsy of involved tissue remains the cornerstone of diagnosis; the organisms appear in tissues as broad, branching nonseptate hyphae. Cultures are frequently negative.

Treatment

Treatment

Optimal therapy of mucormycosis involves reversal of predisposing conditions (if possible), surgical debridement, and prompt antifungal therapy. A prolonged course of a lipid preparation of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (5–10 mg/kg with higher doses given for CNS disease) should be started early. Oral posaconazole (300 mg/day) or isavuconazole (200 mg every 8 hours for 1–2 days, then 200 mg daily thereafter) can be used for less severe disease, as step-down therapy after disease stabilization, or as salvage therapy due to poor response to or tolerance of amphotericin. Combination therapy with amphotericin and posaconazole is not proven but is commonly used because of the poor response to monotherapy. Other azoles are not effective. Control of diabetes and other underlying conditions, along with extensive repeated surgical removal of necrotic, nonperfused tissue, is essential. Even when these measures are introduced in a timely fashion, the prognosis remains guarded.

Cornely OA et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Dec;19(12):e405–21. [PMID: 31699664]

Lionakis MS et al. Breakthrough invasive mold infections in the hematology patient: current concepts and future directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Oct 30;67(10):1621–30. [PMID: 29860307]

Marty FM et al. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis: a single-arm open-label trial and case-control analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Jul;16(7):828–37. [PMID: 26969258]

BLASTOMYCOSIS

Blastomycosis occurs most often in men infected during occupational or recreational activities outdoors and in a geographically limited area of the south, central, and midwestern United States and Canada. Disease usually occurs in immunocompetent individuals.

Chronic pulmonary infection is most common and may be asymptomatic. With dissemination, lesions most frequently occur in the skin, bones, and urogenital system.

Cough, moderate fever, dyspnea, and chest pain are common. These may resolve or progress, with purulent sputum production, pleurisy, fever, chills, loss of weight, and prostration. Radiologic studies, either chest radiographs or CT scans, usually reveal lobar consolidation or masses.

Raised, verrucous cutaneous lesions are commonly present in disseminated blastomycosis. Bones—often the ribs and vertebrae—are frequently involved. Epididymitis, prostatitis, and other involvement of the male urogenital system may occur. Although they do not appear to be at greater risk for acquisition of disease, infection in HIV-infected persons may progress rapidly, with dissemination common.

Laboratory findings usually include leukocytosis and anemia. The organism is found in clinical specimens, such as expectorated sputum or tissue biopsies, as a 5–20 mcm thick-walled cell that may have a single broad-based bud. It grows readily on culture. A urinary antigen test is available, but it has considerable cross reactivity with other dimorphic fungi; it may be useful in monitoring disease resolution or progression. The quantitative antigen enzyme immunoassay may be helpful in the diagnosis of CNS disease. A serum enzyme immunoassay based on the surface protein BAD-1 has much better sensitivity and specificity than the urinary antigen test, but it is not yet commercially available.

Itraconazole, 200–400 mg/day orally for at least 6–12 months, is the therapy of choice for nonmeningeal disease, with a response rate of over 80% (Table 36–1). Liposomal amphotericin B, 3–5 mg/kg/day intravenously, is given initially for severe disease, treatment failures, or CNS involvement.

Clinical follow-up for relapse should be made regularly for several years so that therapy may be resumed or another drug instituted.

McBride JA et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment of blastomycosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017 Sep;38(3):435–49. [PMID: 28797487]

PARACOCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS (South American Blastomycosis)

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii infections have been found only in patients who have resided in South or Central America or Mexico. Long asymptomatic periods enable patients to travel far from the endemic areas before developing clinical problems. An acute form of the disease affects predominately younger patients and involves the mononuclear phagocytic system, resulting in progressive lymphadenopathy. A more chronic form affects mostly adult men and involves the lung, skin, mucous membranes, and lymph nodes. Weight loss, pulmonary complaints, or mucosal ulcerations are the most common symptoms. Extensive coalescent ulcerations may eventually result in destruction of the epiglottis, vocal cords, and uvula. Extension to the lips and face may occur. Lymph node enlargement may follow mucocutaneous lesions, eventually ulcerating and forming draining sinuses; in some patients, it is the presenting symptom. Hepatosplenomegaly may be present as well. HIV-infected patients with paracoccidioidomycosis are more likely to have extrapulmonary dissemination and a more rapid clinical disease course.

Laboratory findings are nonspecific. Serology by immunodiffusion is positive in more than 80% of cases. Complement fixation titers correlate with progressive disease and fall with effective therapy. The fungus is found in clinical specimens as a spherical cell that may have many buds arising from it. If direct examination of secretions does not reveal the organism, biopsy with Gomori silver staining may be helpful.

Itraconazole, 100 mg twice daily orally, is the treatment of choice and generally results in a clinical response within 1 month and effective control after 2–6 months. TMP-SMZ (480 mg/1200 mg) twice daily orally is equally effective and less costly but associated with more adverse effects and longer time to clinical cure. Amphotericin B, 0.7–1.0 mg/kg/day intravenously, is the medication of choice for severe and life-threatening infection.

Shikanai-Yasuda MA et al. Brazilian guidelines for the clinical management of paracoccidioidomycosis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2017 Sep–Oct;50(5):715–40. [PMID: 28746570]

SPOROTRICHOSIS

Sporotrichosis is a chronic fungal infection caused by organisms of the Sporothrix schenckii complex. It is worldwide in distribution; most patients have had contact with soil, sphagnum moss, or decaying wood. Infection takes place when the organism is inoculated into the skin—usually on the hand, arm, or foot, especially during gardening, or puncture from a rose thorn.

The most common form of sporotrichosis begins with a hard, nontender subcutaneous nodule. This later becomes adherent to the overlying skin and ulcerates. Within a few days to weeks, lymphocutaneous spread along the lymphatics draining this area occurs, which may result in ulceration. Cavitary pulmonary disease occurs in individuals with underlying chronic lung disease.

Disseminated sporotrichosis is rare in immunocompetent persons but may present with widespread cutaneous, lung, bone, joint, and CNS involvement in immunocompromised patients, especially those with cellular immunodeficiencies, including AIDS and alcohol abuse.

Cultures are needed to establish diagnosis. The usefulness of serologic tests is limited, but may be helpful in diagnosing disseminated disease, especially meningitis.

Itraconazole, 200–400 mg orally daily for several months, is the treatment of choice for localized disease and some milder cases of disseminated disease (Table 36–1). Terbinafine, 500 mg orally twice daily, also has good efficacy in lymphocutaneous disease. Amphotericin B intravenously, 0.7–1.0 mg/kg/day, or a lipid amphotericin B preparation, 3–5 mg/kg/day, is used for severe systemic infection. Surgery may be indicated for complicated pulmonary cavitary disease, and joint involvement may require arthrodesis.

The prognosis is good for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis; pulmonary, joint, and disseminated disease respond less favorably.

Orofino-Costa R et al. Sporotrichosis: an update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol. 2017 Sep–Oct;92(5):606–20. [PMID: 29166494]

MYCETOMA (Eumycetoma & Actinomycetoma)

Mycetoma is a chronic local, slowly progressive destructive infection that usually involves the foot; it begins in subcutaneous tissues, frequently after implantation of vegetative material into tissues during occupational activities. The infection then spreads to contiguous structures with sinus tracts and extruding grains. Eumycetoma (also known as maduromycosis) is the term used to describe mycetoma caused by true fungi. The disease begins as a papule, nodule, or abscess that over months to years progresses slowly to form multiple abscesses and sinus tracts ramifying deep into the tissue. Secondary bacterial infection may result in large open ulcers. Radiographs may show destructive changes in the underlying bone. Causative species can often be suggested by the color of the characteristic grains and hyphal size within the infected tissues but definitive diagnosis requires culture.

The prognosis for eumycetoma is poor, though surgical debridement along with prolonged oral itraconazole therapy, 200 mg twice daily, or combination therapy including itraconazole and terbinafine may result in a response rate of 70% (Table 36–1). The various etiologic agents may respond differently to antifungal agents, so culture results are invaluable. Amputation is necessary in far advanced cases.

van de Sande W et al. Closing the mycetoma knowledge gap. Med Mycol. 2018 Apr 1;56(Suppl 1):153–64. [PMID: 28992217]

OTHER OPPORTUNISTIC MOLD INFECTIONS

Fungi previously considered to be harmless colonizers, including Pseudallescheria boydii (Scedosporium apiospermum), Scedosporium prolificans, Fusarium, Paecilomyces, Trichoderma longibrachiatium, and Trichosporon, are now significant pathogens in immunocompromised patients. Opportunistic infections with these agents are seen in patients being treated for hematologic malignancies, stem cell or organ transplant recipients, and in those receiving broad-spectrum antifungal prophylaxis. Infection may be localized in the skin, lungs, or sinuses, or widespread disease may appear with lesions in multiple organs. Fusariosis should be suspected in severely immunosuppressed persons in whom multiple, painful skin lesions develop; blood cultures are often positive. Sinus infection may cause bony erosion. Infection in subcutaneous tissues following traumatic implantation may develop as a well-circumscribed cyst or as an ulcer.

Nonpigmented septate hyphae are seen in tissue and are indistinguishable from those of Aspergillus when infections are due to S apiospermum or species of Fusarium, Paecilomyces, Penicillium, or other hyaline molds. The differentiation of S apiospermum and Aspergillus is particularly important, since the former is uniformly resistant to amphotericin B but may be sensitive to azole antifungals (eg, voriconazole). Treatment of fusariosis may include amphotericin, voriconazole, or combination therapy; there are limited data on the use of isavuconazole or posaconazole for this disease. In addition to antifungal therapy, reversal of underlying immunosuppression is an essential component of treatment for these invasive mold infections.

Infection by any of a number of black molds is designated as phaeohyphomycosis. These black molds (eg, Exophiala, Bipolaris, Cladophialophora, Curvularia, Alternaria) are common in the environment, especially on decaying vegetation. In tissues of patients with phaeohyphomycosis, the mold is seen as black or faintly brown hyphae, yeast cells, or both. Culture on appropriate medium is needed to identify the agent. Histologic demonstration of these organisms is definitive evidence of invasive infection; positive cultures must be interpreted cautiously and not assumed to be contaminants in immunocompromised hosts.

Lee HJ et al. Characteristics and risk factors for mortality of invasive non-Aspergillus mould infections in patients with haematologic diseases: a single-centre 7-year cohort study. Mycoses. 2020 Mar;63(3):257–64. [PMID: 31762083]

McCarthy MW et al. Recent advances in the treatment of scedosporiosis and fusariosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018 Jun 18;4(2):E73. [PMID: 29912161]

HOUSEHOLD MOLDS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Molds are very common indoors where moisture exists in enclosed spaces.

Molds are very common indoors where moisture exists in enclosed spaces.

Most common indoor molds are Cladosporium, Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Alternaria.

Most common indoor molds are Cladosporium, Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Alternaria.

People most at risk for health problems include those with allergies, asthma, and underlying immunocompromising conditions.

People most at risk for health problems include those with allergies, asthma, and underlying immunocompromising conditions.

Molds are commonly present in homes, particularly in the presence of moisture, and patients will commonly seek assessment for whether their illness is due to molds. Well-established health problems due to molds can be considered in three categories: (1) There is the potential for allergy to environmental mold species, which can manifest in the typical manner with allergic symptoms such as rhinitis and eye irritation. Furthermore, in predisposed individuals, exposure to certain molds can trigger asthma or asthmatic attacks. These types of manifestations are reversible with appropriate therapies. More chronic allergic effects can be seen with disorders such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (see Allergic Forms of Aspergillosis); (2) Susceptible individuals can develop hypersensitivity reactions upon exposure to mold antigens; these include occupational disorders (eg, farmer’s lung and pigeon breeder’s disease) as well as hypersensitivity pneumonitis in response to a large antigenic exposure. Affected patients have fever, lymph node swelling, and pulmonary infiltrates. These disease manifestations are transient and improve with removal of the offending antigen; (3) Invasive mold disease (see Invasive Aspergillosis).

At the present time, there are no data to support that mold exposure can induce immune dysfunction. Similarly, the concept of toxic-mold syndrome or cognitive impairment due to inhalation of mycotoxins has not been validated despite scrutiny by expert panels. The presence of mold in the household is typically easily discernable with visual inspection or detection by odor; if present, predisposing conditions should be corrected by individuals experienced in mold remediation.

A number of laboratories offer testing for the evaluation of patients who suspect they have a mold-induced disorder, such as testing homes for mold spores, measuring urinary “mycotoxins” and serum IgG assays to molds. However, these tests should not be obtained as most are not validated and do not provide meaningful results upon which to make therapeutic decisions.

Borchers AT et al. Mold and human health: a reality check. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017 Jun;52(3):305–22. [PMID: 28299723]

Chang C et al. The myth of mycotoxins and mold injury. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019 Dec;57(3):449–55. [PMID: 31608429]

ANTIFUNGAL THERAPY

Table 36–1 summarizes the major properties of currently available antifungal agents. Two different lipid-based amphotericin B formulations are used to treat systemic invasive fungal infections. Their principal advantage appears to be substantially reduced nephrotoxicity, allowing administration of much higher doses. Three agents of the echinocandin class, caspofungin, anidulafungin, and micafungin are approved for use. The echinocandins have relatively few adverse effects and are useful for the treatment of invasive Candida infections, although resistance has emerged clinically; C glabrata in particular has shown resistance to this class of antifungals. Voriconazole has excellent activity against a broad range of fungal pathogens and has been FDA approved for use in invasive Aspergillus, Fusarium and Scedosporium infections, Candida esophagitis, deep Candida infections, and candidemia. Posaconazole has good activity against a broad range of filamentous fungi, including the Mucorales. Therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended in individuals with severe invasive fungal infections receiving azole therapy because of unreliable serum levels due to either metabolic alterations as a result of genetic polymorphisms (voriconazole) or erratic absorption (itraconazole and posaconazole). A delayed-release tablet preparation of posaconazole provides more reliable pharmacokinetics compared to the oral solution. Isavuconazole is approved for the treatment of aspergillosis and mucormycosis, although the data for use in the latter are sparse; a trial of isavuconazole versus caspofungin failed to establish noninferiority of this agent for candidemia. Advantages of isavuconazole include the availability of an intravenous form that does not utilize the cyclodextrin carrier like previous azoles as well as an oral form with relatively reliable pharmacokinetic properties.

Chatelon J et al. Choosing the right antifungal agent in ICU patients. Adv Ther. 2019 Dec;36(12):3308–20. [PMID: 31617055]

Kuriakose K et al. Posaconazole-induced pseudohyperaldosteronism. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018 Apr 26;62(5):e02130–17. [PMID: 29530850]

Latgé JP et al. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis in 2019. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019 Nov 13;33(1):e00140–18. [PMID: 31722890]