8

Ear, Nose, & Throat Disorders

Lawrence R. Lustig, MD

Joshua S. Schindler, MD

DISEASES OF THE EAR

HEARING LOSS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Two main types of hearing loss: conductive and sensorineural.

Two main types of hearing loss: conductive and sensorineural.

Most commonly due to cerumen impaction, transient eustachian tube dysfunction from upper respiratory tract infection, or age-related hearing loss.

Most commonly due to cerumen impaction, transient eustachian tube dysfunction from upper respiratory tract infection, or age-related hearing loss.

Classification & Epidemiology

Classification & Epidemiology

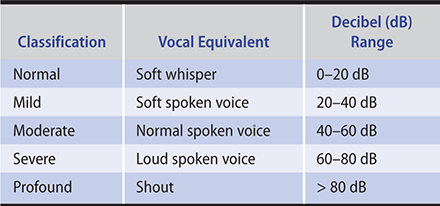

Table 8–1 categorizes hearing loss as normal, mild, moderate, severe, and profound and outlines the vocal equivalent as well as the decibel range.

Table 8–1. Hearing loss classification.

A. Conductive Hearing Loss

Conductive hearing loss results from external or middle ear dysfunction. Four mechanisms each result in impairment of the passage of sound vibrations to the inner ear: (1) obstruction (eg, cerumen impaction), (2) mass loading (eg, middle ear effusion), (3) stiffness (eg, otosclerosis), and (4) discontinuity (eg, ossicular disruption). Conductive losses in adults are most commonly due to cerumen impaction or transient eustachian tube dysfunction from upper respiratory tract infection. Persistent conductive losses usually result from chronic ear infection, trauma, or otosclerosis. Conductive hearing loss is often correctable with medical or surgical therapy, or both.

B. Sensorineural Hearing Loss

Sensory and neural causes of hearing loss are difficult to differentiate due to testing methodology and thus are often referred to as “sensorineural.” Sensorineural hearing losses are common in adults.

Sensory hearing loss results from deterioration of the cochlea, usually due to loss of hair cells from the organ of Corti. The most common form is a gradually progressive, predominantly high-frequency loss with advancing age (presbyacusis); other causes include excessive noise exposure, head trauma, and systemic diseases. Sensory hearing loss is usually not correctable with medical or surgical therapy but often may be prevented or stabilized. An exception is a sudden sensory hearing loss, which may respond to corticosteroids if delivered within several weeks of onset.

Neural hearing loss lesions involve the eighth cranial nerve, auditory nuclei, ascending tracts, or auditory cortex. Neural hearing loss is much less commonly recognized. Causes include acoustic neuroma, multiple sclerosis, and auditory neuropathy.

Cunningham LL et al. Hearing loss in adults. N Engl J Med. 2017 Dec 21;377(25):2465–73. [PMID: 29262274]

Nieman CL et al. Otolaryngology for the internist: hearing loss. Med Clin North Am. 2018 Nov;102(6):977–92. [PMID: 30342615]

Evaluation of Hearing (Audiology)

Evaluation of Hearing (Audiology)

In a quiet room, the hearing level may be estimated by having the patient repeat aloud words presented in a soft whisper, a normal spoken voice, or a shout. A 512-Hz tuning fork is useful in differentiating conductive from sensorineural losses. In the Weber test, the tuning fork is placed on the forehead or front teeth. In conductive losses, the sound appears louder in the poorer-hearing ear, whereas in sensorineural losses it radiates to the better side. In the Rinne test, the tuning fork is placed alternately on the mastoid bone and in front of the ear canal. In conductive losses greater than 25 dB, bone conduction exceeds air conduction; in sensorineural losses, the opposite is true.

Formal audiometric studies are performed in a soundproofed room. Pure-tone thresholds in decibels (dB) are obtained over the range of 250–8000 Hz for both air and bone conduction. Conductive losses create a gap between the air and bone thresholds, whereas in sensorineural losses, both air and bone thresholds are equally diminished. Speech discrimination measures the clarity of hearing, reported as percentage correct (90–100% is normal). Auditory brainstem-evoked responses may determine whether the lesion is sensory (cochlea) or neural (central). However, MRI scanning is more sensitive and specific in detecting central lesions.

Every patient who complains of a hearing loss should be referred for audiologic evaluation unless the cause is easily remediable (eg, cerumen impaction, otitis media). Immediate audiometric referral is indicated for patients with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss because it requires treatment (corticosteroids) within a limited several-week time period. Routine audiologic screening is recommended for adults with prior exposure to potentially injurious noise levels or in adults at age 65, and every few years thereafter.

Almeyda R et al. Assessing and treating adult patients with hearing loss. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2018 Nov 2;79(11):628–33. [PMID: 30418825]

Musiek FE et al. Perspectives on the pure-tone audiogram. J Am Acad Audiol. 2017 Jul/Aug;28(7):655–71. [PMID: 28722648]

Hearing Amplification

Hearing Amplification

Patients with hearing loss not correctable by medical therapy may benefit from hearing amplification. Contemporary hearing aids are comparatively free of distortion and have been miniaturized to the point where they often may be contained entirely within the ear canal or lie inconspicuously behind the ear.

For patients with conductive loss or unilateral profound sensorineural loss, bone-conducting hearing aids directly stimulate the ipsilateral cochlea (for conductive losses) or contralateral ear (profound unilateral sensorineural loss).

In most adults with severe to profound sensory hearing loss, the cochlear implant—an electronic device that is surgically implanted into the cochlea to stimulate the auditory nerve—offers socially beneficial auditory rehabilitation.

Johnson CE et al. Benefits from, satisfaction with, and self-efficacy for advanced digital hearing aids in users with mild sensorineural hearing loss. Semin Hear. 2018 May;39(2):158–71. [PMID: 29915453]

Jorgensen LE et al. Conventional amplification for children and adults with severe-to-profound hearing loss. Semin Hear. 2018 Nov;39(4):364–76. [PMID: 30374208]

McRackan TR et al. Meta-analysis of quality-of-life improvement after cochlear implantation and associations with speech recognition abilities. Laryngoscope. 2018 Apr;128(4):982–90. [PMID: 28731538]

Michaud HN et al. Aural rehabilitation for older adults with hearing loss: impacts on quality of life—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Audiol. 2017 Jul/Aug;28(7):596–609. [PMID: 28722643]

DISEASES OF THE AURICLE

Disorders of the auricle include skin cancers due to sun exposure. Traumatic auricular hematoma must be drained to prevent significant cosmetic deformity (cauliflower ear) or canal blockage resulting from dissolution of supporting cartilage. Similarly, cellulitis of the auricle must be treated promptly to prevent perichondritis and resultant deformity. Relapsing polychondritis is characterized by recurrent, frequently bilateral, painful episodes of auricular erythema and edema and sometimes progressive involvement of the cartilaginous tracheobronchial tree. Treatment with corticosteroids may help forestall cartilage dissolution. Polychondritis and perichondritis may be differentiated from cellulitis by sparing of involvement of the lobule, which does not contain cartilage.

Dalal PJ et al. Risk factors for auricular hematoma and recurrence after drainage. Laryngoscope. 2020 Mar;130(3):628–31. [PMID: 31621925]

DISEASES OF THE EAR CANAL

1. Cerumen Impaction

Cerumen is a protective secretion produced by the outer portion of the ear canal. In most persons, the ear canal is self-cleansing. Recommended hygiene consists of cleaning the external opening only with a washcloth over the index finger. Cerumen impaction is most often self-induced through ill-advised cleansing attempts by entering the canal itself. It may be relieved by the patient using detergent ear drops (eg, 3% hydrogen peroxide; 6.5% carbamide peroxide) and irrigation, or by the clinician using mechanical removal, suction, or irrigation. Irrigation is performed with water at body temperature to avoid a vestibular caloric response. The stream should be directed at the posterior ear canal wall adjacent to the cerumen plug. Irrigation should be performed only when the tympanic membrane is known to be intact.

Use of jet irrigators (eg, WaterPik) should be avoided since they may result in tympanic membrane perforations. Following irrigation, the ear canal should be thoroughly dried (eg, by the patient using a hair blow-dryer on low-power setting or by the clinician instilling isopropyl alcohol) to reduce the likelihood of external otitis. Specialty referral is indicated if impaction is frequently recurrent, if it has not responded to routine measures, or if there is tympanic membrane perforation or chronic otitis media.

Schwartz SR et al. Clinical Practice Guideline (Update): Earwax (cerumen impaction). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Jan;156(1 Suppl):S1–29. [PMID: 28045591]

2. Foreign Bodies

Foreign bodies in the ear canal are more frequent in children than in adults. Firm materials may be removed with a loop or a hook, taking care not to displace the object medially toward the tympanic membrane; microscopic guidance is helpful. Aqueous irrigation should not be performed for organic foreign bodies (eg, beans, insects), because water may cause them to swell. Living insects are best immobilized before removal by filling the ear canal with lidocaine.

Karimnejad K et al. External auditory canal foreign body extraction outcomes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2017 Nov;126(11):755–61. [PMID: 28954532]

Shunyu NB et al. Ear, nose and throat foreign bodies removed under general anaesthesia: a retrospective study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Feb;11(2):MC01–4. [PMID: 28384894]

3. External Otitis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Painful erythema and edema of the ear canal skin.

Painful erythema and edema of the ear canal skin.

Purulent exudate.

Purulent exudate.

In diabetic or immunocompromised patients, osteomyelitis of the skull base (“malignant external otitis”) may occur.

In diabetic or immunocompromised patients, osteomyelitis of the skull base (“malignant external otitis”) may occur.

General Considerations

General Considerations

External otitis presents with otalgia, frequently accompanied by pruritus and purulent discharge. There is often a history of recent water exposure (ie, swimmer’s ear) or mechanical trauma (eg, scratching, cotton applicators). External otitis is usually caused by gram-negative rods (eg, Pseudomonas, Proteus) or fungi (eg, Aspergillus), which grow in the presence of excessive moisture. In diabetic or immunocompromised patients, persistent external otitis may evolve into osteomyelitis of the skull base (so-called malignant external otitis). Usually caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, osteomyelitis begins in the floor of the ear canal and may extend into the middle fossa floor, the clivus, and even the contralateral skull base.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Examination reveals erythema and edema of the ear canal skin, often with a purulent exudate (Figure 8–1). Manipulation of the auricle elicits pain. Because the lateral surface of the tympanic membrane is ear canal skin, it is often erythematous. However, in contrast to acute otitis media, it moves normally with pneumatic otoscopy. When the canal skin is very edematous, it may be impossible to visualize the tympanic membrane. Malignant external otitis typically presents with persistent foul aural discharge, granulations in the ear canal, deep otalgia, and in advanced cases, progressive palsies of cranial nerves VI, VII, IX, X, XI, or XII. Diagnosis is confirmed by the demonstration of osseous erosion on CT scanning.

Figure 8–1. Malignant external otitis in a 40-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus, with typical swelling and honey-colored crusting of the pinna. Both the external auditory canal and temporal bone were involved in the pseudomonal infection. (Used, with permission, from E.J. Mayeaux Jr, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment of external otitis involves protection of the ear from additional moisture and avoidance of further mechanical injury by scratching. In cases of moisture in the ear (eg, swimmer’s ear), acidification with a drying agent (ie, a 50/50 mixture of isopropyl alcohol/white vinegar) is often helpful. When infected, an otic antibiotic solution or suspension of an aminoglycoside (eg, neomycin/polymyxin B) or fluoroquinolone (eg, ciprofloxacin), with or without a corticosteroid (eg, hydrocortisone), is usually effective. Purulent debris filling the ear canal should be gently removed to permit entry of the topical medication. Drops should be used abundantly (five or more drops three or four times a day) to penetrate the depths of the canal. When substantial edema of the canal wall prevents entry of drops into the ear canal, a wick is placed to facilitate their entry. In recalcitrant cases—particularly when cellulitis of the periauricular tissue has developed—oral fluoroquinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, 500 mg twice daily for 1 week) are used because of their effectiveness against Pseudomonas. Any case of persistent otitis externa in an immunocompromised or diabetic individual must be referred for specialty evaluation.

Treatment of “malignant external otitis” requires prolonged antipseudomonal antibiotic administration, often for several months. Although intravenous therapy is often required initially (eg, ciprofloxacin 200–400 mg every 12 hours), selected patients may be graduated to oral ciprofloxacin (500–1000 mg twice daily). To avoid relapse, antibiotic therapy should be continued, even in the asymptomatic patient, until gallium scanning indicates marked reduction or resolution of the inflammation. Surgical debridement of infected bone is reserved for cases of deterioration despite medical therapy.

Mildenhall N et al. Clinician adherence to the clinical practice guideline: Acute otitis externa. Laryngoscope. 2019 Nov 15. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 31730729]

Peled C et al. Necrotizing otitis externa-analysis of 83 cases: clinical findings and course of disease. Otol Neurotol. 2019 Jan;40(1):56–62. [PMID: 30239427]

Wang X et al. Use of systemic antibiotics for acute otitis externa: impact of a clinical practice guideline. Otol Neurotol. 2018 Oct;39(9):1088–94. [PMID: 30124617]

4. Pruritus

Pruritus of the external auditory canal, particularly at the meatus, is common. While it may be associated with external otitis or with seborrheic dermatitis or psoriasis, most cases are self-induced from excoriation or overly zealous ear cleaning. To permit regeneration of the protective cerumen blanket, patients should be instructed to avoid use of soap and water or cotton swabs in the ear canal and avoid any scratching. Patients with excessively dry canal skin may benefit from application of mineral oil, which helps counteract dryness and repel moisture. When an inflammatory component is present, topical application of a corticosteroid (eg, 0.1% triamcinolone) may be beneficial.

5. Exostoses & Osteomas

Bony overgrowths of the ear canal are a frequent incidental finding and occasionally have clinical significance. Clinically, they present as skin-covered bony mounds in the medial ear canal obscuring the tympanic membrane to a variable degree. Solitary osteomas are of no significance as long as they do not cause obstruction or infection. Multiple exostoses, which are generally acquired from repeated exposure to cold water (eg, “surfer’s ear”), may progress and require surgical removal.

Kim SH. Exostoses of the external auditory canals. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2017 Mar 2;78(3):174. [PMID: 28277770]

6. Neoplasia

The most common neoplasm of the ear canal is squamous cell carcinoma. When an apparent otitis externa does not resolve on therapy, a malignancy should be suspected and biopsy performed. This disease carries a very high 5-year mortality rate because the tumor tends to invade the lymphatics of the cranial base and must be treated with wide surgical resection and radiation therapy. Adenomatous tumors, originating from the ceruminous glands, generally follow a more indolent course.

Oya R et al. Surgery with or without postoperative radiation therapy for early-stage external auditory canal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol. 2017 Oct;38(9):1333–8. [PMID: 28796084]

Seligman KL et al. Temporal bone carcinoma: treatment patterns and survival. Laryngoscope. 2020 Jan;130(1):E11–20. [PMID: 30874314]

DISEASES OF THE EUSTACHIAN TUBE

1. Eustachian Tube Dysfunction

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Aural fullness.

Aural fullness.

Fluctuating hearing.

Fluctuating hearing.

Discomfort with barometric pressure change.

Discomfort with barometric pressure change.

At risk for serous otitis media.

At risk for serous otitis media.

The tube that connects the middle ear to the nasopharynx—the eustachian tube—provides ventilation and drainage for the middle ear cleft. It is normally closed, opening only during swallowing or yawning. When eustachian tube function is compromised, air trapped within the middle ear becomes absorbed and negative pressure results. The most common causes of eustachian tube dysfunction are diseases associated with edema of the tubal lining, such as viral upper respiratory tract infections and allergy. The patient usually reports a sense of fullness in the ear and mild to moderate impairment of hearing. When the tube is only partially blocked, swallowing or yawning may elicit a popping or crackling sound. Examination may reveal retraction of the tympanic membrane and decreased mobility on pneumatic otoscopy. Following a viral illness, this disorder is usually transient, lasting days to weeks. Treatment with systemic and intranasal decongestants (eg, pseudoephedrine, 60 mg orally every 4–6 hours; oxymetazoline, 0.05% spray every 8–12 hours) combined with autoinflation by forced exhalation against closed nostrils may hasten relief. Autoinflation should not be recommended to patients with active intranasal infection, since this maneuver may precipitate middle ear infection. Allergic patients may also benefit from intranasal corticosteroids (eg, beclomethasone dipropionate, two sprays in each nostril twice daily for 2–6 weeks). Air travel, rapid altitudinal change, and underwater diving should be avoided until resolution.

Conversely, an overly patent eustachian tube (“patulous eustachian tube”) is a relatively uncommon, though quite distressing problem. Typical complaints include fullness in the ear and autophony, an exaggerated ability to hear oneself breathe and speak. A patulous eustachian tube may develop during rapid weight loss, or it may be idiopathic. In contrast to eustachian tube dysfunction, the aural pressure is often made worse by exertion and may diminish during an upper respiratory tract infection. Although physical examination is usually normal, respiratory excursions of the tympanic membrane may occasionally be detected during vigorous breathing. Treatment includes avoidance of decongestant products, insertion of a ventilating tube to reduce the outward stretch of the eardrum during phonation, and rarely, surgery on the eustachian tube itself.

Huisman JML et al. Treatment of eustachian tube dysfunction with balloon dilation: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2018 Jan;128(1):237–47. [PMID: 28799657]

Meyer TA et al. A randomized controlled trial of balloon dilation as a treatment for persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction with 1-year follow-up. Otol Neurotol. 2018 Aug;39(7):894–902. [PMID: 29912819]

Ward BK et al. Patulous eustachian tube dysfunction: patient demographics and comorbidities. Otol Neurotol. 2017 Oct;38(9):1362–9. [PMID: 28796094]

2. Serous Otitis Media

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Eustachian tube remains blocked for a prolonged period.

Eustachian tube remains blocked for a prolonged period.

Resultant negative pressure results in transudation of fluid.

Resultant negative pressure results in transudation of fluid.

Prolonged eustachian tube dysfunction with resultant negative middle ear pressure may cause a transudation of fluid. In adults, serous otitis media usually occurs with an upper respiratory tract infection, with barotrauma, or with chronic allergic rhinitis, but when persistent and unilateral, nasopharyngeal carcinoma must be excluded. The tympanic membrane is dull and hypomobile, occasionally accompanied by air bubbles in the middle ear and conductive hearing loss. The treatment of serous otitis media is similar to that for eustachian tube dysfunction. When medication fails to bring relief after several months, a ventilating tube placed through the tympanic membrane may restore hearing and alleviate the sense of aural fullness. Endoscopically guided laser expansion of the nasopharyngeal orifice of the eustachian tube or balloon dilation may improve function in recalcitrant cases.

Roditi RE et al. Otitis media with effusion: our national practice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Aug;157(2):171–2. [PMID: 28535139]

Vanneste P et al. Otitis media with effusion in children: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. A review. J Otol. 2019 Jun;14(2):33–9. [PMID: 31223299]

3. Barotrauma

Persons with poor eustachian tube function (eg, congenital narrowness or acquired mucosal edema) may be unable to equalize the barometric stress exerted on the middle ear by air travel, rapid altitudinal change, or underwater diving. The problem is generally most acute during airplane descent, since the negative middle ear pressure tends to collapse and block the eustachian tube, causing pain. Several measures are useful to enhance eustachian tube function and avoid otic barotrauma. The patient should be advised to swallow, yawn, and autoinflate frequently during descent. Oral decongestants (eg, pseudoephedrine, 60–120 mg) should be taken several hours before anticipated arrival time so that they will be maximally effective during descent. Topical decongestants such as 1% phenylephrine nasal spray should be administered 1 hour before arrival.

For acute negative middle ear pressure that persists on the ground, treatment includes decongestants and attempts at autoinflation. Myringotomy (creation of a small eardrum perforation) provides immediate relief and is appropriate in the setting of severe otalgia and hearing loss. Repeated episodes of barotrauma in persons who must fly frequently may be alleviated by insertion of ventilating tubes.

Underwater diving may represent an even greater barometric stress to the ear than flying. Patients should be warned to avoid diving when they have an upper respiratory infection or episode of nasal allergy. During the descent phase of the dive, if inflation of the middle ear via the eustachian tube has not occurred, pain will develop within the first 15 feet; the dive must be aborted. In all cases, divers must descend slowly and equilibrate in stages to avoid the development of severely negative pressures in the tympanum that may result in hemorrhage (hemotympanum) or in perilymphatic fistula. In the latter, the oval or round window ruptures, resulting in sensory hearing loss and acute vertigo. During the ascent phase of a saturation dive, sensory hearing loss or vertigo may develop as the first (or only) symptom of decompression sickness. Immediate recompression will return intravascular gas bubbles to solution and restore the inner ear microcirculation.

Tympanic membrane perforation is an absolute contraindication to diving, as the patient will experience an unbalanced thermal stimulus to the semicircular canals and may experience vertigo, disorientation, and even emesis.

Rozycki SW et al. Inner ear barotrauma in divers: an evidence-based tool for evaluation and treatment. Diving Hyperb Med. 2018 Sep 30;48(3):186–93. [PMID: 30199891]

Ryan P et al. Prevention of otic barotrauma in aviation: a systematic review. Otol Neurotol. 2018 Jun;39(5):539–49. [PMID: 29595579]

DISEASES OF THE MIDDLE EAR

1. Acute Otitis Media

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Otalgia, often with an upper respiratory tract infection.

Otalgia, often with an upper respiratory tract infection.

Erythema and hypomobility of tympanic membrane.

Erythema and hypomobility of tympanic membrane.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Acute otitis media is a bacterial infection of the mucosally lined air-containing spaces of the temporal bone. Purulent material forms not only within the middle ear cleft but also within the pneumatized mastoid air cells and petrous apex. Acute otitis media is usually precipitated by a viral upper respiratory tract infection that causes eustachian tube obstruction. This results in accumulation of fluid and mucus, which becomes secondarily infected by bacteria. The most common pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pyogenes.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

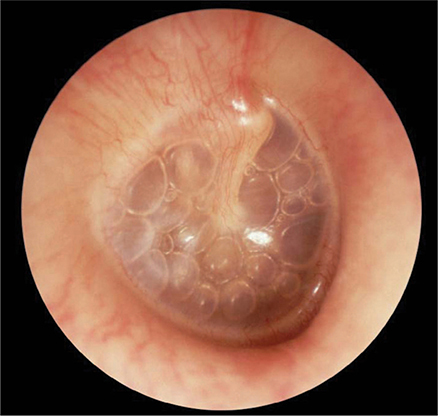

Acute otitis media may occur at any age. Presenting symptoms and signs include otalgia, aural pressure, decreased hearing, and often fever. The typical physical findings are erythema and decreased mobility of the tympanic membrane (Figure 8–2). Occasionally, bullae will appear on the tympanic membrane.

Figure 8–2. Acute otitis media with effusion of right ear, with multiple air-fluid levels visible through a translucent, slightly retracted, nonerythematous tympanic membrane. (Used, with permission, from Frank Miller, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

Rarely, when middle ear empyema is severe, the tympanic membrane bulges outward. In such cases, tympanic membrane rupture is imminent. Rupture is accompanied by a sudden decrease in pain, followed by the onset of otorrhea. With appropriate therapy, spontaneous healing of the tympanic membrane occurs in most cases. When perforation persists, chronic otitis media may develop. Mastoid tenderness often accompanies acute otitis media and is due to the presence of pus within the mastoid air cells. This alone does not indicate suppurative (surgical) mastoiditis. Frank swelling over the mastoid bone or the association of cranial neuropathies or central findings indicates severe disease requiring urgent care.

Treatment

Treatment

The treatment of acute otitis media is specific antibiotic therapy, often combined with nasal decongestants. The first-choice antibiotic is amoxicillin 1 g orally every 8 hours for 5–7 days. Alternatives (useful in resistant cases) are amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg or 2 g/125 mg ER every 12 hours for 5–10 days; or cefuroxime 500 mg or cefpodoxime 200 mg orally every 12 hours for 5–7 days.

Tympanocentesis for bacterial (aerobic and anaerobic) and fungal culture may be performed by any experienced physician. A 20-gauge spinal needle bent 90 degrees to the hub attached to a 3-mL syringe is inserted through the inferior portion of the tympanic membrane. Interposition of a pliable connecting tube between the needle and syringe permits an assistant to aspirate without inducing movement of the needle. Tympanocentesis is useful for otitis media in immunocompromised patients and when infection persists or recurs despite multiple courses of antibiotics.

Surgical drainage of the middle ear (myringotomy) is reserved for patients with severe otalgia or when complications of otitis (eg, mastoiditis, meningitis) have occurred.

Recurrent acute otitis media may be managed with long-term antibiotic prophylaxis. Single daily oral doses of sulfamethoxazole (500 mg) or amoxicillin (250 or 500 mg) are given over a period of 1–3 months. Failure of this regimen to control infection is an indication for insertion of ventilating tubes.

Hutz MJ et al. Neurological complications of acute and chronic otitis media. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018 Feb 14;18(3):11. [PMID: 29445883]

Szmuilowicz J et al. Infections of the ear. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019 Feb;37(1):1–9. [PMID: 30454772]

2. Chronic Otitis Media

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Chronic otorrhea with or without otalgia.

Chronic otorrhea with or without otalgia.

Tympanic membrane perforation with conductive hearing loss.

Tympanic membrane perforation with conductive hearing loss.

Often amenable to surgical correction.

Often amenable to surgical correction.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Chronic infection of the middle ear and mastoid generally develops as a consequence of recurrent acute otitis media, although it may follow other diseases and trauma. Perforation of the tympanic membrane is usually present. The bacteriology of chronic otitis media differs from that of acute otitis media. Common organisms include P aeruginosa, Proteus species, Staphylococcus aureus, and mixed anaerobic infections.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

The clinical hallmark of chronic otitis media is purulent aural discharge. Drainage may be continuous or intermittent, with increased severity during upper respiratory tract infection or following water exposure. Pain is uncommon except during acute exacerbations. Conductive hearing loss results from destruction of the tympanic membrane or ossicular chain, or both.

Treatment

Treatment

The medical treatment of chronic otitis media includes regular removal of infected debris, use of earplugs to protect against water exposure, and topical antibiotic drops (ofloxacin 0.3% or ciprofloxacin with dexamethasone) for exacerbations. Oral ciprofloxacin, active against Pseudomonas, 500 mg twice a day for 1–6 weeks, may help dry a chronically discharging ear.

Definitive management is surgical in most cases. Successful reconstruction of the tympanic membrane may be achieved in about 90% of cases, often with elimination of infection and significant improvement in hearing. When the mastoid air cells are involved by irreversible infection, they should be exenterated at the same time through a mastoidectomy.

Emmett SD et al. Chronic ear disease. Med Clin North Am. 2018 Nov;102(6):1063–79. [PMID: 30342609]

Master A et al. Management of chronic suppurative otitis media and otosclerosis in developing countries. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018 Jun;51(3):593–605. [PMID: 29525390]

Complications of Otitis Media

Complications of Otitis Media

A. Cholesteatoma

Cholesteatoma is a special variety of chronic otitis media (Figure 8–3). The most common cause is prolonged eustachian tube dysfunction, with inward migration of the upper flaccid portion of the tympanic membrane. This creates a squamous epithelium-lined sac, which—when its neck becomes obstructed—may fill with desquamated keratin and become chronically infected. Cholesteatomas typically erode bone, with early penetration of the mastoid and destruction of the ossicular chain. Over time they may erode into the inner ear, involve the facial nerve, and on rare occasions spread intracranially. Otoscopic examination may reveal an epitympanic retraction pocket or a marginal tympanic membrane perforation that exudes keratin debris, or granulation tissue. The treatment of cholesteatoma is surgical marsupialization of the sac or its complete removal. This may require the creation of a “mastoid bowl” in which the ear canal and mastoid are joined into a large common cavity that must be periodically cleaned.

Figure 8–3. Cholesteatoma. (Used, with permission, from Vladimir Zlinsky, MD, in Roy F. Sullivan, PhD: Audiology Forum: Video Otoscopy, www.RCSullivan.com; from Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H, Tysinger J. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. McGraw-Hill, 2009.)

Luu K et al. Updates in pediatric cholesteatoma: minimizing intervention while maximizing outcomes. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2019 Oct;52(5):813–23. [PMID: 31280890]

Rutkowska J et al. Cholesteatoma definition and classification: a literature review. J Int Adv Otol. 2017 Aug;13(2):266–71. [PMID: 28274903]

B. Mastoiditis

Acute suppurative mastoiditis usually evolves following several weeks of inadequately treated acute otitis media. It is characterized by postauricular pain and erythema accompanied by a spiking fever. CT scan reveals coalescence of the mastoid air cells due to destruction of their bony septa. Initial treatment consists of intravenous antibiotics (eg, cefazolin 0.5–1.5 g every 6–8 hours) directed against the most common offending organisms (S pneumoniae, H influenzae, and S pyogenes), and myringotomy for culture and drainage. Failure of medical therapy indicates the need for surgical drainage (mastoidectomy).

C. Petrous Apicitis

The medial portion of the petrous bone between the inner ear and clivus may become a site of persistent infection when the drainage of its pneumatic cell tracts becomes blocked. This may cause foul discharge, deep ear and retro-orbital pain, and sixth nerve palsy (Gradenigo syndrome); meningitis may be a complication. Treatment is with prolonged antibiotic therapy (based on culture results) and surgical drainage via petrous apicectomy.

Gadre AK et al. The changing face of petrous apicitis—a 40-year experience. Laryngoscope. 2018 Jan;128(1):195–201. [PMID: 28378370]

Ren Y et al. Acute otitis media and associated complications in United States emergency departments. Otol Neurotol. 2018 Sep;39(8):1005–11. [PMID: 30113560]

D. Facial Paralysis

Facial palsy may be associated with either acute or chronic otitis media. In the acute setting, it results from inflammation of the seventh nerve in its middle ear segment. Treatment consists of myringotomy for drainage and culture, followed by intravenous antibiotics (based on culture results). The use of corticosteroids is controversial. The prognosis is excellent, with complete recovery in most cases.

Facial palsy associated with chronic otitis media usually evolves slowly due to chronic pressure on the seventh nerve in the middle ear or mastoid by cholesteatoma. Treatment requires surgical correction of the underlying disease. The prognosis is less favorable than for facial palsy associated with acute otitis media.

Owusu JA et al. Facial nerve paralysis. Med Clin North Am. 2018 Nov;102(6):1135–43. [PMID: 30342614]

Prasad S et al. Facial nerve paralysis in acute suppurative otitis media—management. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Mar;69(1):58–61. [PMID: 28239580]

Zhang W et al. The etiology of Bell’s palsy: a review. J Neurol. 2019 Mar 28. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 30923934]

E. Sigmoid Sinus Thrombosis

Trapped infection within the mastoid air cells adjacent to the sigmoid sinus may cause septic thrombophlebitis. This is heralded by signs of systemic sepsis (spiking fevers, chills), at times accompanied by signs of increased intracranial pressure (headache, lethargy, nausea and vomiting, papilledema). Diagnosis can be made noninvasively by magnetic resonance venography (MRV). Primary treatment is with intravenous antibiotics (based on culture results). Surgical drainage with ligation of the internal jugular vein may be indicated when embolization is suspected.

F. Central Nervous System Infection

Otogenic meningitis is by far the most common intracranial complication of ear infection. In the setting of acute suppurative otitis media, it arises from hematogenous spread of bacteria, most commonly H influenzae and S pneumoniae. In chronic otitis media, it results either from passage of infection along preformed pathways, such as the petrosquamous suture line, or from direct extension of disease through the dural plates of the petrous pyramid.

Epidural abscesses arise from direct extension of disease in the setting of chronic infection. They are usually asymptomatic but may present with deep local pain, headache, and low-grade fever. They are often discovered as an incidental finding at surgery. Brain abscess may arise in the temporal lobe or cerebellum as a result of septic thrombophlebitis adjacent to an epidural abscess. The predominant causative organisms are S aureus, S pyogenes, and S pneumoniae. Rupture into the subarachnoid space results in meningitis and often death. (See Chapter 30.)

Hutz MJ et al. Neurological complications of acute and chronic otitis media. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018 Feb 14;18(3):11. [PMID: 29445883]

Mather M et al. Is anticoagulation beneficial in acute mastoiditis complicated by sigmoid sinus thrombosis? Laryngoscope. 2018 Nov;128(11):2435–6. [PMID: 29521448]

3. Otosclerosis

Otosclerosis is a progressive disease with a marked familial tendency that affects the bony otic capsule. Lesions involving the footplate of the stapes result in increased impedance to the passage of sound through the ossicular chain, producing conductive hearing loss. This may be treated either through the use of a hearing aid or surgical replacement of the stapes with a prosthesis (stapedectomy). When otosclerotic lesions involve the cochlea (“cochlear otosclerosis”), permanent sensory hearing loss occurs.

Gillard DM et al. Cost-effectiveness of stapedectomy vs hearing aids in the treatment of otosclerosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Nov 7. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 31697352]

Yeh CF et al. Predictors of hearing outcomes after stapes surgery in otosclerosis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2019 Dec;139(12):1058–62. [PMID: 31617779]

4. Trauma to the Middle Ear

Tympanic membrane perforation may result from impact injury or explosive acoustic trauma (Figure 8–4). Spontaneous healing occurs in most cases. Persistent perforation may result from secondary infection brought on by exposure to water. During the healing period, patients should be advised to wear earplugs while swimming or bathing. Hemorrhage behind an intact tympanic membrane (hemotympanum) may follow blunt trauma or extreme barotrauma. Spontaneous resolution over several weeks is the usual course. When a conductive hearing loss greater than 30 dB persists for more than 3 months following trauma, disruption of the ossicular chain should be suspected. Middle ear exploration with reconstruction of the ossicular chain, combined with repair of the tympanic membrane when required, will usually restore hearing.

Figure 8–4. Traumatic perforation of the left tympanic membrane. (Used, with permission, from William Clark, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H, Tysinger J. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. McGraw-Hill, 2009.)

Sagiv D et al. Traumatic perforation of the tympanic membrane: a review of 80 cases. J Emerg Med. 2018 Feb;54(2):186–90. [PMID: 29110975]

5. Middle Ear Neoplasia

Primary middle ear tumors are rare. Glomus tumors arise either in the middle ear (glomus tympanicum) or in the jugular bulb with upward erosion into the hypotympanum (glomus jugulare). They present clinically with pulsatile tinnitus and hearing loss. A vascular mass may be visible behind an intact tympanic membrane. Large glomus jugulare tumors are often associated with multiple cranial neuropathies, especially involving nerves VII, IX, X, XI, and XII. Treatment usually requires surgery, radiotherapy, or both. Pulsatile tinnitus thus warrants magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and MRV to rule out a vascular mass.

Killeen DE et al. Endoscopic management of middle ear paragangliomas: a case series. Otol Neurotol. 2017 Mar;38(3):408–15. [PMID: 28192382]

Marinelli JP et al. Adenomatous neuroendocrine tumors of the middle ear: a multi-institutional investigation of 32 cases and development of a staging system. Otol Neurotol. 2018 Sep;39(8):e712–21. [PMID: 30001283]

EARACHE

Earache can be caused by a variety of otologic problems, but external otitis and acute otitis media are the most common. Differentiation of the two should be apparent by pneumatic otoscopy. Pain out of proportion to the physical findings may be due to herpes zoster oticus, especially when vesicles appear in the ear canal or concha. Persistent pain and discharge from the ear suggest osteomyelitis of the skull base or cancer, and patients with these complaints should be referred for specialty evaluation.

Nonotologic causes of otalgia are numerous. The sensory innervation of the ear is derived from the trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal, vagal, and upper cervical nerves. Because of this rich innervation, referred otalgia is quite frequent. Temporomandibular joint dysfunction is a common cause of referred ear pain. Pain is exacerbated by chewing or psychogenic grinding of the teeth (bruxism) and may be associated with dental malocclusion. Repeated episodes of severe lancinating otalgia may occur in glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Infections and neoplasia that involve the oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx frequently cause otalgia. Persistent earache demands specialty referral to exclude cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract.

DISEASES OF THE INNER EAR

1. Sensory Hearing Loss

Diseases of the cochlea result in sensory hearing loss, a condition that is usually irreversible. Most cochlear diseases result in bilateral symmetric hearing loss. The presence of unilateral or asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss suggests a lesion proximal to the cochlea. The primary goals in the management of sensory hearing loss are prevention of further losses and functional improvement with amplification and auditory rehabilitation.

A. Presbyacusis

Presbyacusis, or age-related hearing loss, is the most frequent cause of sensory hearing loss and is progressive, predominantly high-frequency, and symmetrical. Various etiologic factors (eg, prior noise trauma, drug exposure, genetic predisposition) may contribute to presbyacusis. Most patients notice a loss of speech discrimination that is especially pronounced in noisy environments. About 25% of people between the ages of 65 and 75 years and almost 50% of those over 75 experience hearing difficulties.

Tawfik KO et al. Advances in understanding of presbycusis. J Neurosci Res. 2019 Apr 4. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 30950547]

Tu NC et al. Age-related hearing loss: unraveling the pieces. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018 Feb 21;3(2):68–72. [PMID: 29721536]

Vaisbuch Y et al. Age-related hearing loss: innovations in hearing augmentation. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018 Aug;51(4):705–23. [PMID: 29735277]

B. Noise Trauma

Noise trauma is the second most common cause of sensory hearing loss. Sounds exceeding 85 dB are potentially injurious to the cochlea, especially with prolonged exposures. The loss typically begins in the high frequencies (especially 4000 Hz) and, with continuing exposure, progresses to involve the speech frequencies. Among the more common sources of injurious noise are industrial machinery, weapons, and excessively loud music. Personal music devices used at excessive loudness levels may also be injurious. Monitoring noise levels in the workplace by regulatory agencies has led to preventive programs that have reduced the frequency of occupational losses. Individuals of all ages, especially those with existing hearing losses, should wear earplugs when exposed to moderately loud noises and specially designed earmuffs when exposed to explosive noises.

Bielefeld EC et al. Advances and challenges in pharmaceutical therapies to prevent and repair cochlear injuries from noise. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019 Jun 26;13:285. [PMID: 31297051]

Neitzel RL et al. Risk of noise-induced hearing loss due to recreational sound: review and recommendations. J Acoust Soc Am. 2019 Nov;146(5):3911. [PMID: 31795675]

C. Physical Trauma

Head trauma (eg, deployment of air bags during an automobile accident) has effects on the inner ear similar to those of severe acoustic trauma. Some degree of sensory hearing loss may occur following simple concussion and is frequent after skull fracture.

Mizutari K. Update on treatment options for blast-induced hearing loss. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Oct;27(5):376–80. [PMID: 31348022]

D. Ototoxicity

Ototoxic substances may affect both the auditory and vestibular systems. The most commonly used ototoxic medications are aminoglycosides; loop diuretics; and several antineoplastic agents, notably cisplatin. These medications may cause irreversible hearing loss even when administered in therapeutic doses. When using these medications, it is important to identify high-risk patients, such as those with preexisting hearing losses or kidney disease. Patients simultaneously receiving multiple ototoxic agents are at particular risk owing to ototoxic synergy. Useful measures to reduce the risk of ototoxic injury include serial audiometry, monitoring of serum peak and trough levels, and substitution of equivalent nonototoxic drugs whenever possible.

It is possible for topical agents that enter the middle ear to be absorbed into the inner ear via the round window. When the tympanic membrane is perforated, use of potentially ototoxic ear drops (eg, neomycin, gentamicin) is best avoided.

Laurell G. Pharmacological intervention in the field of ototoxicity. HNO. 2019 Jun;67(6):434–9. [PMID: 30993373]

Rybak LP et al. Local drug delivery for prevention of hearing loss. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019 Jul 9;13:300. [PMID: 31338024]

E. Sudden Sensory Hearing Loss

Idiopathic sudden loss of hearing in one ear may occur at any age, but typically it occurs in persons over age 20 years. The cause is unknown; however, one hypothesis is that it results from a viral infection or a sudden vascular occlusion of the internal auditory artery. Prognosis is mixed, with many patients suffering permanent deafness in the involved ear, while others have complete recovery. Prompt treatment with corticosteroids has been shown to improve the odds of recovery. A common regimen is oral prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day, followed by a tapering dose over a 10-day period. Intratympanic administration of corticosteroids alone or in association with oral corticosteroids has been associated with an equal or more favorable prognosis. Because treatment appears to be most effective as close to the onset of the loss as possible, and appears not to be effective after 6 weeks, a prompt audiogram should be obtained in all patients who present with sudden hearing loss without obvious middle ear pathology.

Ahmadzai N et al. A systematic review and network meta-analysis of existing pharmacologic therapies in patients with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. PLoS One. 2019 Sep 9;14(9):e0221713. [PMID: 31498809]

Plontke SK. Diagnostics and therapy of sudden hearing loss. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Feb 19;16:Doc05. [PMID: 29503670]

F. Autoimmune Hearing Loss

Sensory hearing loss may be associated with a wide array of systemic autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and Cogan syndrome (hearing loss, keratitis, aortitis). The loss is most often bilateral and progressive. The hearing level often fluctuates, with periods of deterioration alternating with partial or even complete remission. Usually, there is the gradual evolution of permanent hearing loss, which often stabilizes with some remaining auditory function but occasionally proceeds to complete deafness. Vestibular dysfunction, particularly dysequilibrium and postural instability, may accompany the auditory symptoms.

In many cases, the autoimmune pattern of audiovestibular dysfunction presents in the absence of recognized systemic autoimmune disease. Responsiveness to oral corticosteroid treatment is helpful in making the diagnosis and constitutes first-line therapy. If stabilization of hearing becomes dependent on long-term corticosteroid use, steroid-sparing immunosuppressive regimens may become necessary.

Das S et al. Demystifying autoimmune inner ear disease. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 Dec;276(12):3267–74. [PMID: 31605190]

Mancini P et al. Hearing loss in autoimmune disorders: prevalence and therapeutic options. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 Jul;17(7):644–52. [PMID: 29729446]

2. Tinnitus

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Perception of abnormal ear or head noises.

Perception of abnormal ear or head noises.

Persistent tinnitus often, though not always, indicates the presence of sensory hearing loss.

Persistent tinnitus often, though not always, indicates the presence of sensory hearing loss.

Intermittent periods of mild, high-pitched tinnitus lasting seconds to minutes are common in normal-hearing persons.

Intermittent periods of mild, high-pitched tinnitus lasting seconds to minutes are common in normal-hearing persons.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Tinnitus is defined as the sensation of sound in the absence of an exogenous sound source. Tinnitus can accompany any form of hearing loss, and its presence provides no diagnostic value in determining the cause of a hearing loss. Approximately 15% of the general population experiences some type of tinnitus, with prevalence beyond 20% in aging populations.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Though tinnitus is commonly associated with hearing loss, tinnitus severity correlates poorly with the degree of hearing loss. About one in seven tinnitus sufferers experiences severe annoyance, and 4% are severely disabled. When severe and persistent, tinnitus may interfere with sleep and ability to concentrate, resulting in considerable psychological distress.

Pulsatile tinnitus—often described by the patient as listening to one’s own heartbeat—should be distinguished from tonal tinnitus. Although often ascribed to conductive hearing loss, pulsatile tinnitus may be far more serious and may indicate a vascular abnormality, such as glomus tumor, venous sinus stenosis, carotid vaso-occlusive disease, arteriovenous malformation, or aneurysm. In contrast, a staccato “clicking” tinnitus may result from middle ear muscle spasm, sometimes associated with palatal myoclonus. The patient typically perceives a rapid series of popping noises, lasting seconds to a few minutes, accompanied by a fluttering feeling in the ear.

B. Diagnostic Testing

For routine, nonpulsatile tinnitus, audiometry should be ordered to rule out an associated hearing loss. For unilateral tinnitus, particularly associated with hearing loss in the absence of an obvious causative factor (ie, noise trauma), an MRI should be obtained to rule out a retrocochlear lesion, such as vestibular schwannoma. MRA and MRV and temporal bone computed tomography (CT) should be considered for patients who have pulsatile tinnitus to exclude a causative vascular lesion or sigmoid sinus abnormality.

Treatment

Treatment

The most important treatment of tinnitus is avoidance of exposure to excessive noise, ototoxic agents, and other factors that may cause cochlear damage. Masking the tinnitus with music or through amplification of normal sounds with a hearing aid may also bring some relief. Among the numerous drugs that have been tried, oral antidepressants (eg, nortriptyline at an initial dosage of 50 mg orally at bedtime) have proved to be the most effective. In addition to masking techniques, habituation techniques, such as tinnitus retraining therapy, may prove beneficial in those with refractory symptoms.

Chari DA et al. Tinnitus. Med Clin North Am. 2018 Nov;102(6):1081–93. [PMID: 30342610]

Wu V et al. Approach to tinnitus management. Can Fam Physician. 2018 Jul;64(7):491–5. [PMID: 30002023]

Zenner HP et al. A multidisciplinary systematic review of the treatment for chronic idiopathic tinnitus. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 May;274(5):2079–91. [PMID: 27995315]

3. Hyperacusis

Excessive sensitivity to sound may occur in normal-hearing individuals, either in association with ear disease, following noise trauma, in patients susceptible to migraines, or for psychological reasons. Patients with cochlear dysfunction commonly experience “recruitment,” an abnormal sensitivity to loud sounds despite a reduced sensitivity to softer ones. Fitting hearing aids and other amplification devices to patients with recruitment requires use of compression circuitry to avoid uncomfortable overamplification. For normal-hearing individuals with hyperacusis, use of an earplug in noisy environments may be beneficial, though attempts should be made at habituation.

Aazh H et al. Insights from the third international conference on hyperacusis: causes, evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Noise Health. 2018 Jul–Aug;20(95):162–70. [PMID: 30136676]

Baguley DM et al. Hyperacusis: major research questions. HNO. 2018 May;66(5):358–63. [PMID: 29392341]

4. Vertigo

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Either a sensation of motion when there is no motion or an exaggerated sense of motion in response to movement.

Either a sensation of motion when there is no motion or an exaggerated sense of motion in response to movement.

Duration of vertigo episodes and association with hearing loss are the keys to diagnosis.

Duration of vertigo episodes and association with hearing loss are the keys to diagnosis.

Must differentiate peripheral from central etiologies of vestibular dysfunction.

Must differentiate peripheral from central etiologies of vestibular dysfunction.

Peripheral: Onset is sudden; often associated with tinnitus and hearing loss; horizontal nystagmus may be present.

Peripheral: Onset is sudden; often associated with tinnitus and hearing loss; horizontal nystagmus may be present.

Central: Onset is gradual; no associated auditory symptoms.

Central: Onset is gradual; no associated auditory symptoms.

Evaluation includes audiogram and electronystagmography (ENG) or videonystagmography (VNG) and head MRI.

Evaluation includes audiogram and electronystagmography (ENG) or videonystagmography (VNG) and head MRI.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Vertigo can be caused by either a peripheral or central etiology, or both (Table 8–2).

Peripheral causes

Vestibular neuritis/labyrinthitis

Ménière disease

Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo

Ethanol intoxication

Inner ear barotraumas

Semicircular canal dehiscence

Central causes

Seizure

Multiple sclerosis

Wernicke encephalopathy

Chiari malformation

Cerebellar ataxia syndromes

Mixed central and peripheral causes

Migraine

Stroke and vascular insufficiency

Posterior inferior cerebellar artery stroke

Anterior inferior cerebellar artery stroke

Vertebral artery insufficiency

Vasculitides

Cogan syndrome

Susac syndrome

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis)

Behçet disease

Cerebellopontine angle tumors

Vestibular schwannoma

Meningioma

Infections

Lyme disease

Syphilis

Vascular compression

Hyperviscosity syndromes

Waldenström macroglobulinemia

Endocrinopathies

Hypothyroidism

Pendred syndrome

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

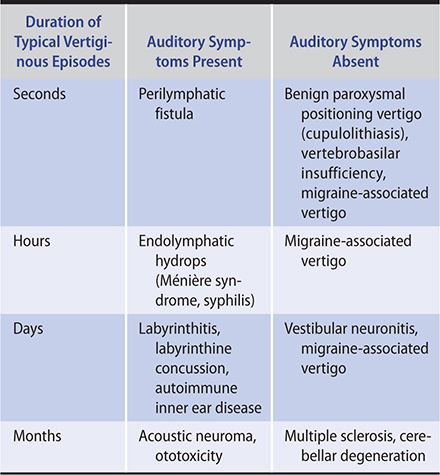

Vertigo is the cardinal symptom of vestibular disease. Vertigo is typically experienced as a distinct “spinning” sensation or a sense of tumbling or of falling forward or backward. It should be distinguished from imbalance, light-headedness, and syncope, all of which are nonvestibular in origin (Table 8–3).

Table 8–3. Common vestibular disorders: differential diagnosis based on classic presentations.

1. Peripheral vestibular disease—Peripheral vestibulopathy usually causes vertigo of sudden onset, may be so severe that the patient is unable to walk or stand, and is frequently accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Tinnitus and hearing loss may be associated and provide strong support for a peripheral (ie, otologic) origin.

Critical elements of the history include the duration of the discrete vertiginous episodes (seconds, minutes to hours, or days), and associated symptoms (hearing loss). Triggers should be sought, including diet (eg, high salt in the case of Ménière disease), stress, fatigue, and bright lights (eg, migraine-associated dizziness).

The physical examination of the patient with vertigo includes evaluation of the ears, observation of eye motion and nystagmus in response to head turning, cranial nerve examination, and Romberg testing. In acute peripheral lesions, nystagmus is usually horizontal with a rotatory component; the fast phase usually beats away from the diseased side. Visual fixation tends to inhibit nystagmus except in very acute peripheral lesions or with CNS disease. In benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo, Dix-Hallpike testing (quickly lowering the patient to the supine position with the head extending over the edge and placed 30 degrees lower than the body, turned either to the left or right) will elicit a delayed-onset (~10 sec) fatiguable nystagmus. Nonfatigable nystagmus in this position indicates CNS disease.

Since visual fixation often suppresses observed nystagmus, many of these maneuvers are performed with Frenzel goggles, which prevent visual fixation, and often bring out subtle forms of nystagmus. The Fukuda test can demonstrate vestibular asymmetry when the patient steps in place with eyes closed and consistently rotates in one direction.

2. Central disease—In contrast, vertigo arising from CNS disease (Table 8–2) tends to develop gradually and then becomes progressively more severe and debilitating. Nystagmus is not always present but can occur in any direction, may be dissociated in the two eyes, and is often nonfatigable, vertical rather than horizontal in orientation, without latency, and unsuppressed by visual fixation. ENG is useful in documenting these characteristics. Evaluation of central audiovestibular dysfunction requires MRI of the brain.

Episodic vertigo can occur in patients with diplopia from external ophthalmoplegia and is maximal when the patient looks in the direction where the separation of images is greatest. Cerebral lesions involving the temporal cortex may also produce vertigo; it is sometimes the initial symptom of a seizure. Finally, vertigo may be a feature of a number of systemic disorders and can occur as a side effect of certain anticonvulsant, antibiotic, hypnotic, analgesic, and tranquilizer medications or of alcohol.

Welgampola MS et al. Dizziness demystified. Pract Neurol. 2019 Dec;19(6):492–501. [PMID: 31326945]

B. Laboratory Findings

Laboratory investigations, such as audiologic evaluation, caloric stimulation, ENG, VNG, vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs), and MRI, are indicated in patients with persistent vertigo or when CNS disease is suspected. These studies help distinguish between central and peripheral lesions and identify causes requiring specific therapy. ENG consists of objective recording of the nystagmus induced by head and body movements, gaze, and caloric stimulation. It is helpful in quantifying the degree of vestibular hypofunction.

Sorathia S et al. Dizziness and the otolaryngology point of view. Med Clin North Am. 2018 Nov;102(6):1001–12. [PMID: 30342604]

Whitman GT. Dizziness. Am J Med. 2018 Dec;131(12):1431–7. [PMID: 29859806]

Vertigo Syndromes Due to Peripheral Lesions

Vertigo Syndromes Due to Peripheral Lesions

A. Endolymphatic Hydrops (Ménière Syndrome)

The cause of Ménière syndrome is unknown. The classic syndrome consists of episodic vertigo, with discrete vertigo spells lasting 20 minutes to several hours in association with fluctuating low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus (usually low-tone and “blowing” in quality), and a sensation of unilateral aural pressure (Table 8–3). These symptoms in the absence of hearing fluctuations suggest migraine-associated dizziness. Symptoms wax and wane as the endolymphatic pressure rises and falls. Caloric testing commonly reveals loss or impairment of thermally induced nystagmus on the involved side. Primary treatment involves a low-salt diet and diuretics (eg, acetazolamide). For symptomatic relief of acute vertigo attacks, oral meclizine (25 mg) or diazepam (2–5 mg) can be used. In refractory cases, patients may undergo intratympanic corticosteroid injections, endolymphatic sac decompression, or vestibular ablation, either through transtympanic gentamicin, vestibular nerve section, or surgical labyrinthectomy.

Gibson WPR. Meniere’s disease. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;82:77–86. [PMID: 30947172]

B. Labyrinthitis

Patients with labyrinthitis suffer from acute onset of continuous, usually severe vertigo lasting several days to a week, accompanied by hearing loss and tinnitus. During a recovery period that lasts for several weeks, the vertigo gradually improves. Hearing may return to normal or remain permanently impaired in the involved ear. The cause of labyrinthitis is unknown. Treatment consists of antibiotics, if the patient is febrile or has symptoms of a bacterial infection, and supportive care. Vestibular suppressants are useful during the acute phase of the attack (eg, diazepam or meclizine) but should be discontinued as soon as feasible to avoid long-term dysequilibrium from inadequate compensation.

Welgampola MS et al. Dizziness demystified. Pract Neurol. 2019 Dec;19(6):492–501. [PMID: 31326945]

C. Benign Paroxysmal Positioning Vertigo

Patients suffering from recurrent spells of vertigo, lasting a few minutes per spell, associated with changes in head position (often provoked by rolling over in bed), usually have benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo (BPPV). The term “positioning vertigo” is more accurate than “positional vertigo” because it is provoked by changes in head position rather than by the maintenance of a particular posture.

The typical symptoms of BPPV occur in clusters that persist for several days. There is a brief (10–15 sec) latency period following a head movement before symptoms develop, and the acute vertigo subsides within 10–60 seconds, though the patient may remain imbalanced for several hours. Constant repetition of the positional change leads to habituation. Since some CNS disorders can mimic BPPV (eg, vertebrobasilar insufficiency), recurrent cases warrant head MRI/MRA. In central lesions, there is no latent period, fatigability, or habituation of the symptoms and signs. Treatment of BPPV involves physical therapy protocols (eg, the Epley maneuver or Brandt-Daroff exercises), based on the theory that it results from cupulolithiasis (free-floating statoconia, also known as otoconia) within a semicircular canal.

Argaet EC et al. Benign positional vertigo, its diagnosis, treatment and mimics. Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2019 Apr 6;4:97–111. [PMID: 31193795]

Instrum RS et al. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;82:67–76. [PMID: 30947198]

D. Vestibular Neuronitis

In vestibular neuronitis, a paroxysmal, usually single attack of vertigo occurs without accompanying impairment of auditory function and will persist for several days to a week before gradually abating. During the acute phase, examination reveals nystagmus and absent responses to caloric stimulation on one or both sides. The cause of the disorder is unclear though presumed to be viral. Treatment consists of supportive care, including oral diazepam, 2–5 mg every 6–12 hours, or meclizine, 25–100 mg divided two to three times daily, during the acute phases of the vertigo only, followed by vestibular therapy if the patient does not completely compensate.

Bronstein AM et al. Long-term clinical outcome in vestibular neuritis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019 Feb;32(1):174–80. [PMID: 30566414]

van Esch BF et al. Clinical characteristics of benign recurrent vestibulopathy: clearly distinctive from vestibular migraine and Menière’s disease? Otol Neurotol. 2017 Oct;38(9):e357–63. [PMID: 28834943]

E. Traumatic Vertigo

Labyrinthine concussion is the most common cause of vertigo following head injury. Symptoms generally diminish within several days but may linger for a month or more. Basilar skull fractures that traverse the inner ear usually result in severe vertigo lasting several days to a week and deafness in the involved ear. Chronic posttraumatic vertigo may result from cupulolithiasis. This occurs when traumatically detached statoconia (otoconia) settle on the ampulla of the posterior semicircular canal and cause an excessive degree of cupular deflection in response to head motion. Clinically, this presents as episodic positioning vertigo. Treatment consists of supportive care and vestibular suppressant medication (diazepam or meclizine) during the acute phase of the attack, and vestibular therapy.

Marcus HJ et al. Vestibular dysfunction in acute traumatic brain injury. J Neurol. 2019 Oct;266(10):2430–3. [PMID: 31201499]

F. Perilymphatic Fistula

Leakage of perilymphatic fluid from the inner ear into the tympanic cavity via the round or oval window is a rare cause of vertigo and sensory hearing loss. Most cases result from either physical injury (eg, blunt head trauma, hand slap to ear); extreme barotrauma during airflight, scuba diving, etc; or vigorous Valsalva maneuvers (eg, during weight lifting). Treatment may require middle ear exploration and window sealing with a tissue graft.

Deveze A et al. Diagnosis and treatment of perilymphatic fistula. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;81:133–45. [PMID: 29794455]

G. Cervical Vertigo

Position receptors located in the facets of the cervical spine are important physiologically in the coordination of head and eye movements. Cervical proprioceptive dysfunction is a common cause of vertigo triggered by neck movements. This disturbance often commences after neck injury, particularly hyperextension; it is also associated with degenerative cervical spine disease. Although symptoms vary, vertigo may be triggered by assuming a particular head position as opposed to moving to a new head position (the latter typical of labyrinthine dysfunction). Cervical vertigo may often be confused with migraine-associated vertigo, which is also associated with head movement. Management consists of neck movement exercises to the extent permitted by orthopedic considerations.

Devaraja K. Approach to cervicogenic dizziness: a comprehensive review of its aetiopathology and management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018 Oct;275(10):2421–33. [PMID: 30094486]

Ranalli P. An overview of central vertigo disorders. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;82:127–33. [PMID: 30947212]

H. Migrainous Vertigo

Episodic vertigo is frequently associated with migraine headache. Head trauma may also be a precipitating feature. The vertigo may be temporally related to the headache and last up to several hours, or it may also occur in the absence of any headache. Migrainous vertigo may resemble Ménière disease but without associated hearing loss or tinnitus. Accompanying symptoms may include head pressure; visual, motion, or auditory sensitivity; and photosensitivity. Symptoms typically worsen with lack of sleep and anxiety or stress. Food triggers include caffeine, chocolate, and alcohol, among others. There is often a history of motion intolerance (easily carsick as a child). Migrainous vertigo may be familial. Treatment includes dietary and lifestyle changes (improved sleep pattern, avoidance of stress) and antimigraine prophylactic medication.

Hain T et al. Migraine associated vertigo. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;82:119–26. [PMID: 30947176]

I. Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence

Deficiency in the bony covering of the superior semicircular canal may be associated with vertigo triggered by loud noise exposure, straining, and an apparent conductive hearing loss. Autophony is also a common feature. Diagnosis is with coronal high-resolution CT scan and VEMPs. Surgically resurfacing or plugging the dehiscent canal can improve symptoms.

Ahmed W et al. Systematic review of round window operations for the treatment of superior semicircular canal dehiscence. J Int Adv Otol. 2019 Aug;15(2):209–14. [PMID: 31418721]

Naert L et al. Aggregating the symptoms of superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2018 Aug;128(8):1932–8. [PMID: 29280497]

Vertigo Syndromes Due to Central Lesions

Vertigo Syndromes Due to Central Lesions

CNS causes of vertigo include brainstem vascular disease, arteriovenous malformations, tumors of the brainstem and cerebellum, multiple sclerosis, and vertebrobasilar migraine (Table 8–2). Vertigo of central origin often becomes unremitting and disabling. The associated nystagmus is often nonfatigable, vertical rather than horizontal in orientation, without latency, and unsuppressed by visual fixation. ENG is useful in documenting these characteristics. There are commonly other signs of brainstem dysfunction (eg, cranial nerve palsies; motor, sensory, or cerebellar deficits in the limbs) or of increased intracranial pressure. Auditory function is generally spared. The underlying cause should be treated.

Choi JY et al. Central vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018 Feb;31(1):81–9. [PMID: 29084063]

Ranalli P. An overview of central vertigo disorders. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;82:127–33. [PMID: 30947212]

DISEASES OF THE CENTRAL AUDITORY & VESTIBULAR SYSTEMS

Lesions of the eighth cranial nerve and central audiovestibular pathways produce neural hearing loss and vertigo (Table 8–3). One characteristic of neural hearing loss is deterioration of speech discrimination out of proportion to the decrease in pure tone thresholds. Another is auditory adaptation, wherein a steady tone appears to the listener to decay and eventually disappear. Auditory evoked responses are useful in distinguishing cochlear from neural losses and may give insight into the site of lesion within the central pathways.

The evaluation of central audiovestibular disorders usually requires imaging of the internal auditory canal, cerebellopontine angle, and brain with enhanced MRI.

1. Vestibular Schwannoma (Acoustic Neuroma)

Eighth cranial nerve schwannomas are among the most common intracranial tumors. Most are unilateral, but about 5% are associated with the hereditary syndrome neurofibromatosis type 2, in which bilateral eighth nerve tumors may be accompanied by meningiomas and other intracranial and spinal tumors. These benign lesions arise within the internal auditory canal and gradually grow to involve the cerebellopontine angle, eventually compressing the pons and resulting in hydrocephalus. Their typical auditory symptoms are unilateral hearing loss with a deterioration of speech discrimination exceeding that predicted by the degree of pure tone loss. Nonclassic presentations, such as sudden unilateral hearing loss, are fairly common. Any individual with a unilateral or asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss should be evaluated for an intracranial mass lesion. Vestibular dysfunction more often takes the form of continuous dysequilibrium than episodic vertigo. Diagnosis is made by enhanced MRI. Treatment consists of observation, microsurgical excision, or stereotactic radiotherapy, depending on such factors as patient age, underlying health, and size of the tumor. Bevacizumab (vascular endothelial growth factor blocker) has shown promise for treatment of tumors in neurofibromatosis type 2.

Kalogeridi MA et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery and radiotherapy for acoustic neuromas. Neurosurg Rev. 2019 Apr 13. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 30982152]

Leon J et al. Observation or stereotactic radiosurgery for newly diagnosed vestibular schwannomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Radiosurg SBRT. 2019;6(2):91–100. [PMID: 31641546]

2. Vascular Compromise

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency is a common cause of vertigo in the elderly. It is often triggered by changes in posture or extension of the neck. Reduced flow in the vertebrobasilar system may be demonstrated noninvasively through MRA. Empiric treatment is with vasodilators and aspirin.

Cornelius JF et al. Compression syndromes of the vertebral artery at the craniocervical junction. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2019;125:151–8. [PMID: 30610316]

3. Multiple Sclerosis

Patients with multiple sclerosis may suffer from episodic vertigo and chronic imbalance. Hearing loss in this disease is most commonly unilateral and of rapid onset. Spontaneous recovery may occur.

Kattah JC et al. Eye movements in demyelinating, autoimmune and metabolic disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020 Feb;33(1):111–6. [PMID: 31770124]

OTOLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS OF AIDS

The otologic manifestations of AIDS are protean. The pinna and external auditory canal may be affected by Kaposi sarcoma and by persistent and potentially invasive fungal infections (particularly Aspergillus fumigatus). Serous otitis media due to eustachian tube dysfunction may arise from adenoidal hypertrophy (HIV lymphadenopathy), recurrent mucosal viral infections, or an obstructing nasopharyngeal tumor (eg, lymphoma). Unfortunately, ventilating tubes are seldom helpful and may trigger profuse watery otorrhea. Acute otitis media is usually caused by typical bacterial organisms, including Proteus, Staphylococcus, and Pseudomonas, and rarely, by Pneumocystis jirovecii. Sensorineural hearing loss is common and, in some cases, results from viral CNS infection. In cases of progressive hearing loss, cryptococcal meningitis and syphilis must be excluded. Acute facial paralysis due to herpes zoster infection (Ramsay Hunt syndrome) occurs commonly and follows a clinical course similar to that in nonimmunocompromised patients. Treatment is with high-dose acyclovir (see Chapter 32). Corticosteroids may also be effective as an adjunct.

Bao S et al. Otorhinolaryngological profile and surgical intervention in patients with HIV/AIDS. Sci Rep. 2018 Aug 13;8(1):12045. [PMID: 30104657]

Matas CG et al. Audiological and electrophysiological alterations in HIV-infected individuals subjected or not to antiretroviral therapy. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018 Sep–Oct;84(5):574–82. [PMID: 28823692]

DISEASES OF THE NOSE & PARANASAL SINUSES

INFECTIONS OF THE NOSE & PARANASAL SINUSES

1. Acute Viral Rhinosinusitis (Common Cold)

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Nasal congestion, clear rhinorrhea, and hyposmia.

Nasal congestion, clear rhinorrhea, and hyposmia.

Associated malaise, headache, and cough.

Associated malaise, headache, and cough.

Erythematous, engorged nasal mucosa without intranasal purulence.

Erythematous, engorged nasal mucosa without intranasal purulence.

Symptoms are self-limited, lasting less than 4 weeks and typically less than 10 days.

Symptoms are self-limited, lasting less than 4 weeks and typically less than 10 days.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Because there are numerous serologic types of rhinoviruses, adenoviruses, and other viruses, patients remain susceptible to the common cold throughout life. These infections, while generally quite benign and self-limited, have been implicated in the development or exacerbation of more serious conditions, such as acute bacterial sinusitis and acute otitis media, asthma, cystic fibrosis, and bronchitis. Nasal congestion, decreased sense of smell, watery rhinorrhea, and sneezing, accompanied by general malaise, throat discomfort and, occasionally, headache, are typical in viral infections. Nasal examination usually shows erythematous, edematous mucosa and a watery discharge. The presence of purulent nasal discharge suggests bacterial rhinosinusitis.

Treatment

Treatment

There are no effective antiviral therapies for either the prevention or treatment of most viral rhinitis despite a common misperception among patients that antibiotics are helpful. Prevention of influenza virus infection by boosting the immune system using the annually created vaccine may be the most effective management strategy. Oseltamivir is the first neuramidase inhibitor approved for the treatment and prevention of influenza virus infection, but its use is generally limited to those patients considered high risk. These high-risk patients include young children, pregnant women, and adults older than 65 years of age. Oseltamivir is hard to use because it must be started within 48 hours for optimal effect. Buffered hypertonic saline (3–5%) nasal irrigation has been shown to improve symptoms and reduce the need for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Other supportive measures, such as oral decongestants (pseudoephedrine, 30–60 mg every 4–6 hours or 120 mg twice daily), may provide some relief of rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction. Nasal sprays, such as oxymetazoline or phenylephrine, are rapidly effective but should not be used for more than a few days to prevent rebound congestion. Withdrawal of the drug after prolonged use leads to rhinitis medicamentosa, an almost addictive need for continuous usage. Treatment of rhinitis medicamentosa requires mandatory cessation of the sprays, and this is often extremely frustrating for patients. Topical intranasal corticosteroids (eg, flunisolide, 2 sprays in each nostril twice daily), intranasal anticholinergic (ipratropium 0.06% nasal spray, 2–3 sprays every 8 hours as needed), or a short tapering course of oral prednisone may help during the withdrawal process.

Complications

Complications

Other than mild eustachian tube dysfunction or transient middle ear effusion, complications of viral rhinitis are unusual. Secondary acute bacterial rhinosinusitis is a well-accepted complication of acute viral rhinitis and is suggested by persistence of symptoms beyond 10 days with purulent green or yellow nasal secretions and unilateral facial or tooth pain.

Bergmark RW et al. Diagnosis and first-line treatment of chronic sinusitis. JAMA. 2017 Dec 19;318(23):2344–5. [PMID: 29260210]

Tan KS et al. Impact of respiratory virus infections in exacerbation of acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017 Apr;17(4):24. [PMID: 28389843]

2. Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis (Sinusitis)

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Purulent yellow-green nasal discharge or expectoration.

Purulent yellow-green nasal discharge or expectoration.

Facial pain or pressure over the affected sinus or sinuses.