41

Sports Medicine & Outpatient Orthopedics

Anthony Luke, MD, MPH

C. Benjamin Ma, MD

Musculoskeletal problems account for about 10–20% of outpatient primary care clinical visits. Orthopedic problems can be classified as traumatic (ie, injury-related) or atraumatic (ie, degenerative or overuse syndromes) as well as acute or chronic. The history and physical examination are sufficient in most cases to establish the working diagnosis; the mechanism of injury is usually the most helpful part of the history in determining the diagnosis.

SHOULDER

1. Subacromial Impingement Syndrome

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Shoulder pain with overhead motion.

Shoulder pain with overhead motion.

Night pain with sleeping on shoulder.

Night pain with sleeping on shoulder.

Numbness and pain radiation below the elbow are usually due to cervical spine disease.

Numbness and pain radiation below the elbow are usually due to cervical spine disease.

General Considerations

General Considerations

The shoulder is a ball and socket joint. The socket is very shallow, however, which enables this joint to have the most motion of any joint. The shoulder, therefore, relies heavily on the surrounding muscles and ligaments to provide stability. The subacromial impingement syndrome describes a collection of diagnoses that cause mechanical inflammation in the subacromial space. Causes of impingement syndrome can be related to muscle strength imbalances, poor scapula control, rotator cuff tears, subacromial bursitis, and bone spurs.

With any shoulder problem, it is important to establish the patient’s hand dominance, occupation, and recreational activities because shoulder injuries may present differently depending on the demands placed on the shoulder joint. For example, baseball pitchers with impingement syndrome may complain of pain while throwing. Alternatively, older adults with even full-thickness rotator cuff tears may not complain of any pain because the demands on the joint are low.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

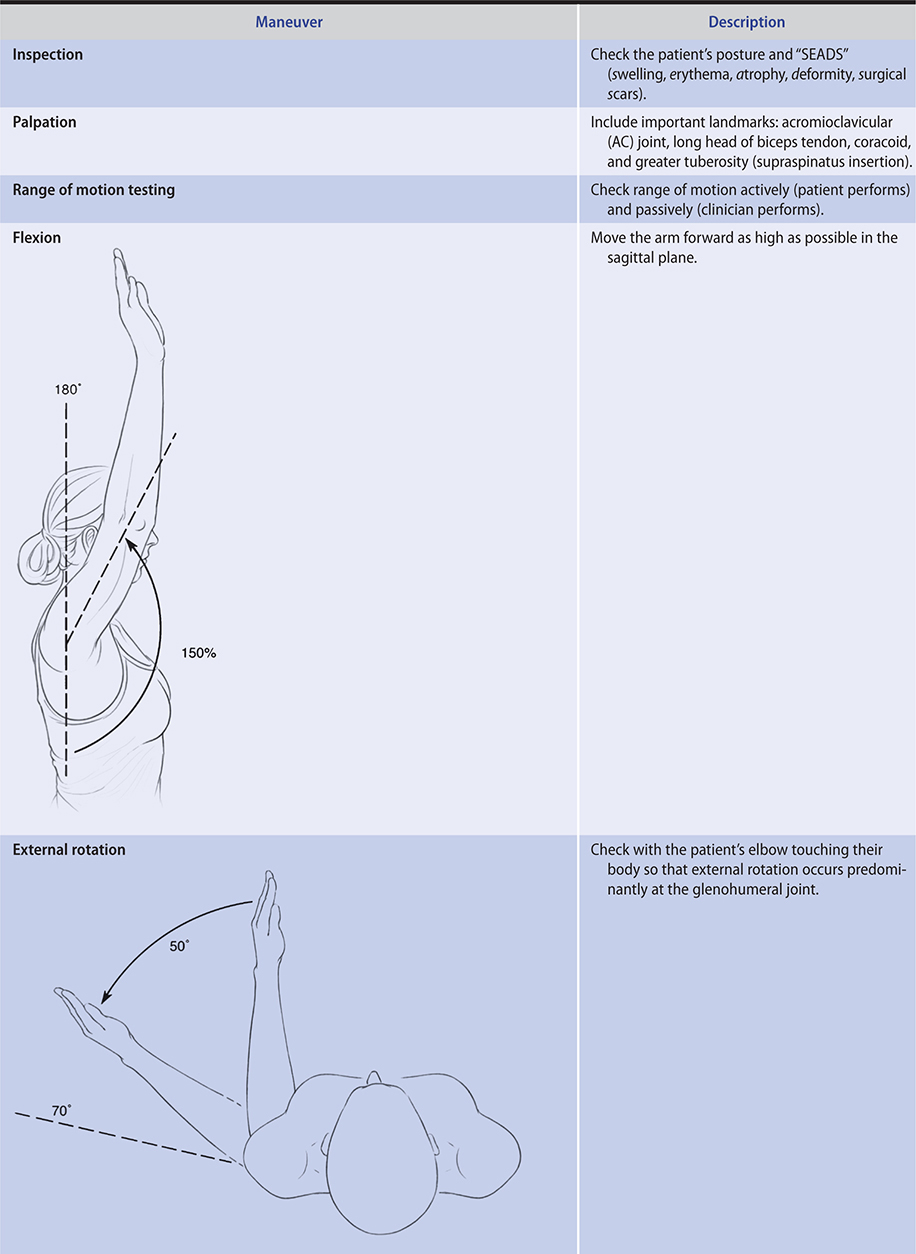

A. Symptoms and Signs

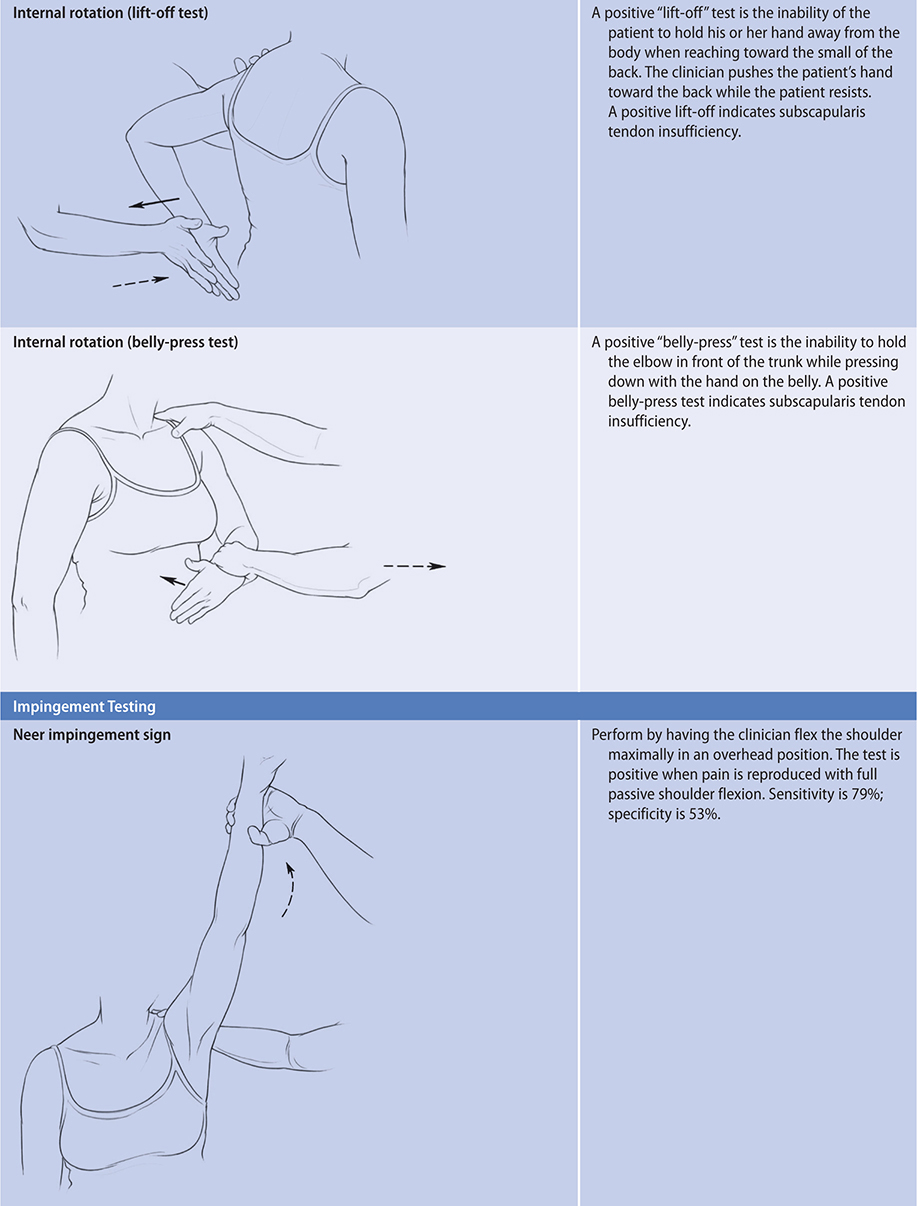

Subacromial impingement syndrome classically presents with one or more of the following: pain with overhead activities, nocturnal pain with sleeping on the shoulder, or pain on internal rotation (eg, putting on a jacket or bra). On inspection, there may be appreciable atrophy in the supraspinatus or infraspinatus fossa. The patient with impingement syndrome can have mild scapula winging or “dyskinesis.” The patient often has a rolled-forward shoulder posture or head-forward posture. On palpation, the patient can have tenderness over the anterolateral shoulder at the edge of the greater tuberosity. The patient may lack full active range of motion (Table 41–1) but should have preserved passive range of motion. Impingement symptoms can be elicited with the Neer and Hawkins impingement signs (Table 41–1).

Table 41–1. Shoulder examination.

B. Imaging

The following four radiographic views should be ordered to evaluate subacromial impingement syndrome: the anteroposterior (AP) scapula, the AP acromioclavicular joint, the lateral scapula (scapular Y), and the axillary lateral. The AP scapula view can rule out glenohumeral joint arthritis. The AP acromioclavicular view evaluates the acromioclavicular joint for inferior spurs. The scapula Y view evaluates the acromial shape, and the axillary lateral view visualizes the glenohumeral joint as well and for the presence of os acromiale.

MRI of the shoulder may demonstrate full- or partial-thickness tears or tendinosis. Ultrasound evaluation may demonstrate thickening of the rotator cuff tendons and tendinosis. Tears may also be visualized on ultrasound, although it is more difficult to identify partial tears from small full-thickness tears than on MRI.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Conservative

The first-line treatment for impingement syndrome is usually a conservative approach with education, activity modification, and physical therapy exercises. Impingement syndrome can be caused by muscle weakness or tear. Rotator cuff muscle strengthening can alleviate weakness or pain, unless the tendons are seriously compromised, in which case exercises may cause more symptoms. Physical therapy is directed at rotator cuff muscle strengthening, scapula stabilization, and postural exercises. There is no strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of ice and NSAIDs as a prolonged therapy. In a Cochrane review, corticosteroid injections produced slightly better relief of symptoms in the short term when compared with placebo. Most patients respond well to conservative treatment.

B. Surgical

Procedures include arthroscopic acromioplasty with coracoacromial ligament release, bursectomy, or debridement or repair of rotator cuff tears. However, the value of acromioplasty alone for rotator cuff problems is not supported by evidence.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Failure of conservative treatment over 3 months.

• Young and active patients with impingement due to full-thickness rotator cuff tears.

Consigliere P et al. Subacromial impingement syndrome: management challenges. Orthop Res Rev. 2018 Oct 23;10:83–91. [PMID: 30774463]

Lai CC et al. Effectiveness of stretching exercise versus kinesiotaping in improving length of the pectoralis minor: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2019 Nov;40:19–26. [PMID: 31442850]

McFarland EG et al. Clinical faceoff: what is the role of acromioplasty in the treatment of rotator cuff disease? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018 Sep;476(9):1707–12. [PMID: 30001291]

Saracoglu I et al. Does taping in addition to physiotherapy improve the outcomes in subacromial impingement syndrome? A systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018 Apr;34(4):251–63. [PMID: 29111849]

2. Rotator Cuff Tears

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

A common cause of shoulder impingement syndrome after age 40.

A common cause of shoulder impingement syndrome after age 40.

Difficulty lifting the arm with limited active range of motion.

Difficulty lifting the arm with limited active range of motion.

Weakness with resisted strength testing suggests full-thickness tears.

Weakness with resisted strength testing suggests full-thickness tears.

Tears can occur following trauma or can be more degenerative.

Tears can occur following trauma or can be more degenerative.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Rotator cuff tears can be caused by acute injuries related to falls on an outstretched arm or to pulling on the shoulder. It can also be related to chronic repetitive injuries with overhead movement and lifting. Partial rotator cuff tears are one of the most common reasons for impingement syndrome. Full-thickness rotator cuff tears are usually more symptomatic and may require surgical treatment. The most commonly torn tendon is the supraspinatus.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Most patients complain of weakness or pain with overhead movement. Night pain is also a common complaint. The clinical findings with rotator cuff tears include those of the impingement syndrome except that with full-thickness rotator cuff tears there may be more obvious weakness noted with light resistance testing of specific rotator cuff muscles. Supraspinatus tendon strength is tested with resisted shoulder abduction at 90 degrees with slight forward flexion to around 45 degrees (“open can” test). Infraspinatus/teres minor strength is tested with resisted shoulder external rotation with shoulder at 0 degrees of abduction and elbow by side. Subscapularis strength is tested with the “lift-off” or “belly-press” tests. The affected patient usually also has positive Neer and Hawkins impingement tests (Table 41–1).

B. Imaging

Recommended radiographs are similar to impingement syndrome: AP scapula (glenohumeral), axillary lateral, supraspinatus outlet, and AP acromioclavicular joint views. The AP scapula view is useful in visualizing rotator cuff tears because degenerative changes can appear between the acromion and greater tuberosity of the shoulder. Axillary lateral views show superior elevation of the humeral head in relation to the center of the glenoid. Supraspinatus outlet views allow evaluation of the shape of the acromion. High-grade acromial spurs are associated with a higher incidence of rotator cuff tears. The AP acromioclavicular joint view evaluates for the presence of acromioclavicular joint arthritis, which can mimic rotator cuff tears, and for spurs that can cause rotator cuff injuries.

MRI is the best method for visualizing rotator cuff tears. The MR arthrogram can show partial or small (less than 1 cm) rotator cuff tears. For patients who cannot undergo MRI testing or when postoperative artifacts limit MRI evaluations, ultrasonography can be helpful.

Treatment

Treatment

Partial rotator cuff tears may heal with scarring. Most partial rotator cuff tears can be treated with physical therapy and scapular and rotator cuff muscle strengthening. However, research suggests that 40% of the partial-thickness tears progress to full-thickness tears in 2 years. Physical therapy can strengthen the remaining muscles to compensate for loss of strength and can have high rate of success for chronic tears. Physical therapy is also an option for older sedentary patients. On the contrary, full-thickness rotator cuff tears do not heal well and also have a tendency to increase in size with time. Forty-nine percent of the full-thickness tears get bigger over an average of 2.8 years. When tears get larger, they are also associated with worsening pain. Fatty infiltration is a degenerative process where muscle is being replaced by fat following injury to the rotator cuff tendons. Fatty infiltration progresses in full-thickness rotator cuff tears and it is a negative prognostic factor for successful surgical treatment. Fatty infiltration is an irreversible process so operative interventions are usually performed when the degree of infiltration is low. Most young active patients with acute, full-thickness tears should be treated with operative fixation. Full-thickness subscapularis tendon tears should undergo surgical repair since untreated tears usually lead to premature osteoarthritis (OA) of the shoulder. Nonetheless, physical therapy is indicated for atraumatic degenerative rotator cuff tears and success can be as high as 70%. That said, long-term (10-year) outcome studies show that surgical repair of rotator cuff tears can result in better outcomes than physical therapy alone.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Young and active patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears.

• Partial tears with greater than 50% involvement and with significant pain.

• Acute rotator cuff tears and loss of function.

• Older and sedentary patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears who have not responded to nonoperative treatment.

• Full-thickness subscapularis tears.

Allen H et al. Overuse injuries of the shoulder. Radiol Clin North Am. 2019 Sep;57(5):897–909. [PMID: 31351540]

Amoo-Achampong K et al. Evaluating strategies and outcomes following rotator cuff tears. Shoulder Elbow. 2019 May;11(1 Suppl):4–18. [PMID: 31019557]

Katthagen JC et al. Improved outcomes with arthroscopic repair of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018 Jan;26(1):113–24. [PMID: 28526996]

Mannava S et al. Options for failed rotator cuff repair. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2018 Sep;26(3):134–8. [PMID: 30059448]

Moosmayer S et al. At a 10-year follow-up, tendon repair is superior to physical therapy in the treatment of small and medium-sized rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019 Jun19;101(12):1050–60. [PMID: 31220021]

Novi M et al. Irreparable rotator cuff tears: challenges and solutions. Orthop Res Rev. 2018 Dec 5;10:93–103. [PMID: 30774464]

Piper CC et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for the management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Mar;27(3):572–6. [PMID: 29169957]

Sochacki KR et al. Superior capsular reconstruction for massive rotator cuff tear leads to significant improvement in range of motion and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2019 Apr;35(4):1269–77. [PMID: 30878330]

Stoll LE et al. Lower trapezius tendon transfer for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Orthop Clin North Am. 2019 Jul;50(3):375–82. [PMID: 31084840]

3. Shoulder Dislocation & Instability

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Most dislocations (95%) are in the anterior direction.

Most dislocations (95%) are in the anterior direction.

Pain and apprehension with an unstable shoulder that is abducted and externally rotated.

Pain and apprehension with an unstable shoulder that is abducted and externally rotated.

Acute shoulder dislocations should be reduced as quickly as possible, using manual relocation techniques if necessary.

Acute shoulder dislocations should be reduced as quickly as possible, using manual relocation techniques if necessary.

General Considerations

General Considerations

The shoulder is a ball and socket joint, similar to the hip. However, the bony contours of the shoulder bones are much different than the hip. Overall, the joint has much less stability than the hip, allowing greater movement and action. Stabilizing the shoulder joint relies heavily on rotator cuff muscle strength and also scapular control. If patients have poor scapular control or weak rotator cuff tendons or tears, their shoulders are more likely to have instability. Ninety-five percent of the shoulder dislocations/instability occur in the anterior direction. Dislocations usually are caused by a fall on an outstretched and abducted arm. Patients complain of pain and feeling of instability when the arm is in the abducted and externally rotated position. Posterior dislocations are usually caused by falls from a height, epileptic seizures, or electric shocks. Traumatic shoulder dislocation can lead to instability. The rate of repeated dislocation is directly related to the patient’s age: patients aged 21 years or younger have a 70–90% risk of redislocation, whereas patients aged 40 years or older have a much lower rate (20–30%). Other risks include male gender and patients with hyperlaxity. Ninety percent of young active individuals who had traumatic shoulder dislocation have labral injuries often described as Bankart lesions when the anterior inferior labrum is torn, which can lead to continued instability. Older patients (over age 55 years) are more likely to have rotator cuff tears or fractures following dislocation. Atraumatic shoulder dislocations are usually caused by intrinsic ligament laxity or repetitive microtrauma leading to joint instability. This is often seen in swimmers, gymnasts, and pitchers as well as other athletes involved in overhead and throwing sports.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

For acute traumatic dislocations, patients usually have an obvious deformity with the humeral head dislocated anteriorly. The patient holds the shoulder and arm in an externally rotated position. The patient complains of acute pain and deformity that are improved with manual relocation of the shoulder. Reductions are usually performed in the emergency department. Even after reduction, the patient will continue to have limited range of motion and pain for 4–6 weeks, especially following a first-time shoulder dislocation.

Patients with recurrent dislocations can have less pain with subsequent dislocations. Posterior dislocations can be easily missed because the patient usually holds the shoulder and arm in an internally rotated position, which makes the shoulder deformity less obvious. Patients complain of difficulty pushing open a door.

Atraumatic shoulder instability is usually well tolerated with activities of daily living. Patients usually complain of a “sliding” sensation during exercises or strenuous activities such as throwing. Such dislocations may be less symptomatic and can often undergo spontaneous reduction of the shoulder with pain resolving within days after onset. The clinical examination for shoulder instability includes the apprehension test, the load and shift test, and the O’Brien test (Table 41–1). Most patients with persistent shoulder instability have preserved range of motion.

B. Imaging

Radiographs for acute dislocations should include a standard trauma series of AP and axillary lateral scapula (glenohumeral) views to determine the relationship of the humerus and the glenoid and to rule out fractures. Orthogonal views are used to identify a posterior shoulder dislocation, which can be missed easily with one AP view of the shoulder. An axillary lateral view of the shoulder can be safely performed even in the acute setting of a patient with a painful shoulder dislocation. A scapula Y view in the acute setting is insufficient to diagnose dislocation. For chronic injuries or symptomatic instability, these recommended radiographic views are helpful to identify bony injuries and Hill-Sachs lesions (indented compression fractures at the posterior-superior part of the humeral head associated with anterior shoulder dislocation). MRI is commonly used to show soft tissue injuries to the labrum and to visualize associated rotator cuff tears. MRI arthrograms better identify labral tears and ligamentous structures. Three-dimensional CT scans are used to determine the significance of bone loss.

Treatment

Treatment

For acute dislocations, the shoulder should be reduced as soon as possible. The Stimson procedure is the least traumatic method and is quite effective. The patient lies prone with the dislocated arm hanging off the examination table with a weight applied to the wrist to provide traction for 20–30 minutes. Afterward, gentle medial mobilization can be applied manually to assist the reduction. The shoulder can also be reduced with axial “traction” on the arm with “counter-traction” along the trunk. The patient should be sedated and relaxed. The shoulder can then be gently internally and externally rotated to guide it back into the socket.

Initial treatment of acute shoulder dislocations should include sling immobilization for 2–4 weeks along with pendulum exercises. Early physical therapy can be used to maintain range of motion and strengthening of rotator cuff muscles. Patients can also modify their activities to avoid active and risky sports. For patients with a traumatic incident and unilateral shoulder dislocation, a Bankart lesion is commonly present. The risk of recurrence is dependent on the age of first shoulder dislocation. Up to 70% of young patients (age less than 27 years) can have a recurrence whereas only 10% of patients older than age 40 have recurrences. However, once the patient has a second dislocation, the recurrence rate is extremely high, up to 95%, regardless of age. Operative intervention is the only treatment that has been shown to decrease recurrence. Open and arthroscopic stabilization have very similar outcomes. Repeated dislocations have been shown to increase the risk of arthritis and further bony deterioration.

The treatment of atraumatic shoulder instability is different than that of traumatic shoulder instability. Patients with chronic, recurrent shoulder dislocations should be managed with physical therapy and a regular maintenance program, consisting of scapular stabilization and postural and rotator cuff strengthening exercises. Activities may need to be modified. Surgical reconstructions are less successful for atraumatic shoulder instability than for traumatic shoulder instability. However, patients with recurrent dislocations have much higher incidence of bone loss or biceps pathology when compared to patients with first-time dislocations. They are also more likely to require open surgery with bone augmentation rather than arthroscopic stabilization.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Patients who are at risk for second dislocation, such as young patients and certain job holders (eg, police officers, firefighters, and rock climbers), to avoid recurrent dislocation or dislocation while at work.

• Patients who have not responded to a conservative approach or who have chronic instability.

Barlow JD et al. Surgical treatment outcomes after primary vs recurrent anterior shoulder instability. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019 Mar–Apr;10(2):222–30. [PMID: 30828182]

Borbas P et al. Surgical management of chronic high-grade acromioclavicular joint dislocations: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019 Oct;28(10):2031–8. [PMID: 31350107]

Garcia JC Jr et al. Comparative systematic review of fixation methods of the coracoid and conjoined tendon in the anterior glenoid to treat anterior shoulder instability. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019 Jan 25;7(1):2325967118820539. [PMID: 30719477]

Gottlieb M et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for the diagnosis of shoulder dislocation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2019 Apr;37(4):757–61. [PMID: 30797607]

Hasebroock AW et al. Management of primary anterior shoulder dislocations: a narrative review. Sports Med Open. 2019 Jul 11;5(1):31. [PMID: 31297678]

Rugg CM et al. Surgical stabilization for the first-time shoulder dislocators: a multicenter analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Apr;27(4):674–85. [PMID: 29321108]

Tamaoki MJ et al. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating acromioclavicular dislocation of the shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Oct 11;10:CD007429. [PMID: 31604007]

4. Adhesive Capsulitis (“Frozen Shoulder”)

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Very painful shoulder triggered by minimal or no trauma.

Very painful shoulder triggered by minimal or no trauma.

Pain out of proportion to clinical findings during the inflammatory phase.

Pain out of proportion to clinical findings during the inflammatory phase.

Stiffness during the “freezing” phase and resolution during the “thawing” phase.

Stiffness during the “freezing” phase and resolution during the “thawing” phase.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Adhesive capsulitis (“frozen shoulder”) is seen commonly in patients 40 to 65 years old. It is more commonly seen in women than men, especially in perimenopausal women or in patients with endocrine disorders, such as diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease. There is higher incidence following breast cancer care (such as mastectomy). Adhesive capsulitis is a self-limiting but very debilitating disease.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Patients usually present with a painful shoulder that has a limited range of motion with both passive and active movements. A useful clinical sign is limitation of movement of external rotation with the elbow by the side of the trunk (Table 41–1). Strength is usually normal but it can appear diminished when the patient is in pain.

There are three phases: the inflammatory phase, the freezing phase, and the thawing phase. During the inflammatory phase, which usually lasts 4–6 months, patients complain of a very painful shoulder without obvious clinical findings to suggest trauma, fracture, or rotator cuff tear. During the “freezing” phase, which also usually lasts 4–6 months, the shoulder becomes stiffer and stiffer even though the pain is improving. The “thawing” phase can take up to a year as the shoulder slowly regains its motion. The total duration of an idiopathic frozen shoulder is usually about 24 months; it can be much longer for patients who have trauma or an endocrinopathy.

B. Imaging

Standard AP, axillary, and lateral glenohumeral radiographs are useful to rule out glenohumeral arthritis, which can also present with limited active and passive range of motion. Imaging can also rule out calcific tendinitis, which is an acute inflammatory process in which calcifications are visible in the soft tissue. However, adhesive capsulitis is usually a clinical diagnosis, and it does not need an extensive diagnostic workup.

Treatment

Treatment

Adhesive capsulitis is caused by acute inflammation of the capsule followed by scarring and remodeling. During the acute “freezing” phase, NSAIDs and physical therapy are recommended to maintain motion. There is also evidence of short-term benefit from intra-articular corticosteroid injection or oral prednisone. A randomized control trial showed that intra-articular corticosteroid injection provided better pain relief than NSAIDs in the first 8 weeks. However, no difference was seen in range of motion or pain after 12 weeks, which is similar to other noncontrolled studies. One study demonstrated improvement at 6 weeks but not 12 weeks following 30 mg of daily prednisone for 3 weeks. During the “freezing” phase, the shoulder is less painful but remains stiff. Anti-inflammatory medication is not as helpful during the “thawing” phase as it is during the “freezing” phase, and the shoulder symptoms usually resolve with time. Surgical treatments, which are rarely indicated, include manipulation under anesthesia and arthroscopic release.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• When the patient does not respond after more than 6 months of conservative treatment.

• When there is no progress in or worsening of range of motion over 3 months.

Alsubheen SA et al. Effectiveness of nonsurgical interventions for managing adhesive capsulitis in patients with diabetes: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019 Feb;100(2):350–65. [PMID: 30268804]

Boutefnouchet T et al. Comparison of outcomes following arthroscopic capsular release for idiopathic, diabetic and secondary shoulder adhesive capsulitis: a systematic review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019 Sep;105(5):839–46. [PMID: 31202716]

Cho CH et al. Treatment strategy for frozen shoulder. Clin Orthop Surg. 2019 Sep;11(3):249–57. [PMID: 31475043]

Fields BKK et al. Adhesive capsulitis: review of imaging findings, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment options. Skeletal Radiol. 2019 Aug;48(8):1171–84. [PMID: 30607455]

Wang W et al. Effectiveness of corticosteroid injections in adhesive capsulitis of shoulder: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Jul;96(28):e7529. [PMID: 28700506]

Xiao RC et al. Evaluating nonoperative treatments for adhesive capsulitis. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2017 Winter;26(4):193–9. [PMID: 29461189]

SPINE PROBLEMS

1. Low Back Pain

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Nerve root impingement is suspected when pain is leg-dominant rather than back-dominant.

Nerve root impingement is suspected when pain is leg-dominant rather than back-dominant.

Alarming symptoms include unexplained weight loss, failure to improve with treatment, severe pain for more than 6 weeks, and night or rest pain.

Alarming symptoms include unexplained weight loss, failure to improve with treatment, severe pain for more than 6 weeks, and night or rest pain.

Cauda equina syndrome is an emergency; often presents with bowel or bladder symptoms (or both).

Cauda equina syndrome is an emergency; often presents with bowel or bladder symptoms (or both).

General Considerations

General Considerations

Low back pain remains the number one cause of disability globally and is the second most common cause for primary care visits. The annual prevalence of low back pain is 15–45%. Annual health care spending for low back and neck pain is estimated to be $87.6 billion. Low back pain is the condition associated with the highest years lived with disability. Approximately 80% of episodes of low back pain resolve within 2 weeks and 90% resolve within 6 weeks. The exact cause of the low back pain is often difficult to diagnose; its cause is often multifactorial. There are usually degenerative changes in the lumbar spine involving the disks, facet joints, and vertebral endplates (Modic changes).

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Aggravating factors of flexion and prolonged sitting commonly suggest anterior spine disk problems, while extension pain suggests facet joint, stenosis, or sacroiliac joint problems. Alarming symptoms for back pain caused by cancer include unexplained weight loss, failure to improve with treatment, pain for more than 6 weeks, and pain at night or rest. History of cancer and age older than 50 years are other risk factors for malignancy. Alarming symptoms for infection include fever, rest pain, recent infection (urinary tract infection, cellulitis, pneumonia), or history of immunocompromise or injection drug use. The cauda equina syndrome is suggested by urinary retention or incontinence, saddle anesthesia, decreased anal sphincter tone or fecal incontinence, bilateral lower extremity weakness, and progressive neurologic deficits. Risk factors for back pain due to vertebral fracture include use of corticosteroids, age over 70 years, history of osteoporosis, severe trauma, and presence of a contusion or abrasion. Back pain may also be the presenting symptom in other serious medical problems, including abdominal aortic aneurysm, peptic ulcer disease, kidney stones, or pancreatitis. The patient’s previous response to treatments and the results of risk prediction tools can help guide management.

The physical examination can be conducted with the patient in the standing, sitting, supine, and finally prone positions to avoid frequent repositioning of the patient. In the standing position, the patient’s posture can be observed. Commonly encountered spinal asymmetries include scoliosis, thoracic kyphosis, and lumbar hyperlordosis. The active range of motion of the lumbar spine can be assessed while standing. The common directions include flexion, extension, rotation, and lateral bending. The one-leg standing extension test assesses for pain as the patient stands on one leg while extending the spine. A positive test can be caused by pars interarticularis fractures (spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis) or facet joint arthritis.

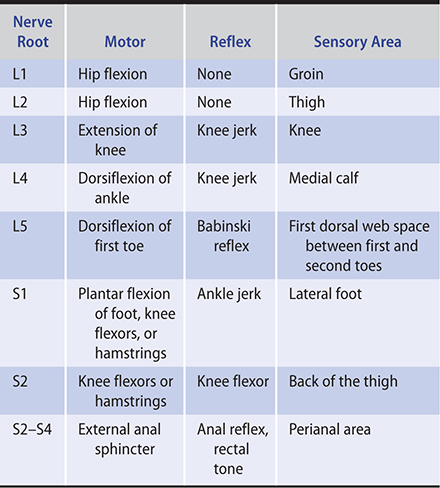

With the patient sitting, motor strength, reflexes, and sensation can be tested (Table 41–2). The major muscles in the lower extremities are assessed for weakness by eliciting a resisted isometric contraction for about 5 seconds. Comparing the strength bilaterally to detect subtle muscle weakness is important. Similarly, sensory testing to light touch can be checked in specific dermatomes for corresponding nerve root function. Knee (femoral nerve L2–4), ankle (deep peroneal nerve L4–L5), and Babinski (sciatic nerve L5–S1) reflexes can be checked with the patient sitting.

Table 41–2. Neurologic testing of lumbosacral nerve disorders.

In the supine position, the hip should be evaluated for range of motion, particularly internal rotation. The straight leg raise test puts traction and compression forces on the lower lumbar nerve roots.

Finally, in the prone position, the clinician can carefully palpate each vertebral level of the spine and sacroiliac joints for tenderness. A rectal examination is required if the cauda equina syndrome is suspected. Superficial skin tenderness to a light touch over the lumbar spine, overreaction to maneuvers in the regular back examination, low back pain on axial loading of spine in standing, and inconsistency in the straight leg raise test or on the neurologic examination suggest nonorthopedic causes for the pain or malingering.

B. Imaging

In the absence of alarming “red flag” symptoms suggesting infection, malignancy, or cauda equina syndrome, most patients do not need diagnostic imaging, including radiographs, in the first 6 weeks. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality guidelines for obtaining lumbar radiographs are summarized in Table 41–3. Most clinicians obtain radiographs for new back pain in patients older than 50 years. If done, radiographs of the lumbar spine should include AP and lateral views. Oblique views can be useful if the neuroforamina or bone lesions need to be visualized. MRI is the method of choice in the evaluation of symptoms not responding to conservative treatment or in the presence of red flags of serious conditions.

Table 41–3. AHRQ criteria for lumbar radiographs in patients with acute low back pain.

Possible fracture

Major trauma

Minor trauma in patients > 50 years of age

Long-term corticosteroid use

Osteoporosis

> 70 years of age

Possible tumor or infection

> 50 years of age

< 20 years of age

History of cancer

Constitutional symptoms

Recent bacterial infection

Injection drug use

Immunosuppression

Supine pain

Nocturnal pain

AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Adapted from Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G, et al. Acute Low Back Problems in Adults. Clinical Practice Guideline Quick Reference Guide No. 14. AHCPR Publication No. 95-0643. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. December 1994.

C. Special Tests

Electromyography or nerve conduction studies may be useful in assessing patients with possible nerve root symptoms lasting longer than 6 weeks; back pain may or may not also be present. These tests are usually not necessary if the diagnosis of radiculopathy is clear.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Conservative

Nonpharmacologic treatments are key in the management of low back pain. Education alone improves patient satisfaction with recovery and recurrence. Patients require information and reassurance, especially when serious pathology is absent. Discussion must include reviewing safe and effective methods of symptom control as well as how to decrease the risk of recurrence with proper lifting techniques, abdominal wall/core strengthening, weight loss, and smoking cessation. Exercise, psychological therapies (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy), and multidisciplinary rehabilitation have been shown to be modestly effective for acute low back pain (strength of evidence, low). Complementary therapies, such as Tai chi, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and yoga, have shown benefit for chronic low back pain patients.

Physical therapy exercise programs can be tailored to the patient’s symptoms and pathology. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that individualized physical therapy was clinically more beneficial than advice alone with sustained improvements at 6 months and 12 months. Strengthening and stabilization exercises effectively reduce pain and functional limitation compared with usual care. Heat and cold treatments have not shown any long-term benefits but may be used for symptomatic treatment. The efficacy of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), back braces, and physical agents is unproven. Spinal manipulation, massage, and acupuncture have limited, low-strength evidence for chronic low back pain. Improvements in posture including chair ergonomics or standing desks, core stability strengthening, physical conditioning, and modifications of activities to decrease physical strain are keys for ongoing management. Radiofrequency denervation of facet joints, sacroiliac joints, or intervertebral disks did not result in clinically important improvement in chronic low back even when combined with a standardized exercise program in randomized controlled trials. A multidisciplinary approach to back pain care is beneficial to address the physical, psychological, and social aspects of low back pain, especially when pain is chronic, avoiding medication if possible.

If medications are needed, NSAIDs are effective in the early treatment of low back pain (see Chapter 20). Acetaminophen and oral corticosteroids are relatively ineffective for chronic low back. There is limited evidence that muscle relaxants provide short-term relief; since these medications have addictive potential, they should be used with care. Muscle relaxants are best used if there is true muscle spasm that is painful rather than simply a protective response. Opioids alleviate pain in the short term, but have the usual side effects and concerns of long-term opioid use (Chapter 5). Treatment of more chronic neuropathic pain with alpha-2-delta ligands (eg, gabapentin), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (eg, duloxetine), or tricyclic antidepressants (eg, nortriptyline) may be helpful (Chapter 5). Epidural injections may reduce pain in the short term and reduce the need for surgery in some patients within a 1-year period but not longer. Therefore, spinal injections are not recommended for initial care of patients with low back pain without radiculopathy.

B. Surgical

Indications for back surgery include cauda equina syndrome, ongoing morbidity with no response to more than 6 months of conservative treatment, cancer, infection, or severe spinal deformity. Prognosis is improved when there is an anatomic lesion that can be corrected and symptoms are neurologic. Spinal surgery has limitations. Patient selection is very important and the specific surgery recommended should have very clear indications. Patients should understand that surgery can improve their pain but is unlikely to cure it. Surgery is not generally indicated for radiographic abnormalities alone when the patient is relatively asymptomatic. Depending on the surgery performed, possible complications include persistent pain; surgical site pain, especially if bone grafting is needed; infection; neurologic damage; non-union; cutaneous nerve damage; implant failure; deep venous thrombosis; and death.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Patients with the cauda equina syndrome.

• Patients with cancer, infection, fracture, or severe spinal deformity.

• Patients who have not responded to conservative treatment.

Barrey CY et al; French Society for Spine Surgery. Chronic low back pain: relevance of a new classification based on the injury pattern. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019 Apr;105(2):339–46. [PMID: 30792166]

Bydon M et al. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: definition, natural history, conservative management, and surgical treatment. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2019 Jul;30(3):299–304. [PMID: 31078230]

Chan AK et al. Summary of guidelines for the treatment of lumbar spondylolisthesis. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2019 Jul;30(3):353–64. [PMID: 31078236]

Galliker G et al. Low back pain in the emergency department: prevalence of serious spinal pathologies and diagnostic accuracy of red flags—a systematic review. Am J Med. 2020 Jan;133(1):60–72. [PMID: 31278933]

Johnson SM et al. Imaging of acute low back pain. Radiol Clin North Am. 2019 Mar;57(2):397–413. [PMID: 30709477]

Karsy M et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of lumbar spondylolisthesis. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2019 Jul;30(3):333–40. [PMID: 31078234]

Tucker HR et al. Harms and benefits of opioids for management of non-surgical acute and chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Jun;54(11):664. [PMID: 30902816]

Urits I et al. Low back pain, a comprehensive review: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019 Mar 11;23(3):23. [PMID: 30854609]

2. Spinal Stenosis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Pain is usually worse with back extension and relieved by sitting.

Pain is usually worse with back extension and relieved by sitting.

Occurs in older patients.

Occurs in older patients.

May present with neurogenic claudication symptoms with walking.

May present with neurogenic claudication symptoms with walking.

General Considerations

General Considerations

OA in the lumbar spine can cause narrowing of the spinal canal. A large disk herniation can also cause stenosis and compression of neural structures or the spinal artery resulting in “claudication” symptoms with ambulation. The condition usually affects patients aged 50 years or older.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Patients report pain that worsens with extension. They describe reproducible single or bilateral leg symptoms that are worse after walking several minutes and that are relieved by sitting (“neurogenic claudication”). On examination, patients often exhibit limited extension of the lumbar spine, which may reproduce the symptoms radiating down the legs. A thorough neurovascular examination is recommended (Table 41–2).

Treatment

Treatment

Exercises, usually flexion-based as demonstrated by a physical therapist, can help relieve symptoms. Physical therapy showed similar results as surgical decompression in a randomized trial, though there was a 57% crossover rate from physical therapy to surgery. Facet joint corticosteroid injections can also reduce pain symptoms. While epidural corticosteroid injections have been shown to provide immediate improvements in pain and function for patients with radiculopathy, the benefits are small and only short term. Consequently, there is limited evidence to recommend epidural corticosteroids for spinal stenosis.

Surgical treatments for spinal stenosis include spinal decompression (widening the spinal canal or laminectomy), nerve root decompression (freeing a single nerve), and spinal fusion (joining the vertebra to eliminate motion and diminish pain from the arthritic joints). However, a Cochrane review showed surgery was not clearly better than nonsurgical treatment and had complication rates of 10–24% compared to 0% for nonoperative treatments. Thus, the role of surgery for spinal stenosis is limited. In one multicenter randomized trial, subgroups initially improved significantly more with surgery than with nonoperative treatment. Variables associated with greater treatment effects included lower baseline disability scores, not smoking, neuroforaminal stenosis, predominant leg pain rather than back pain, not lifting at work, and the presence of a neurologic deficit. However, long-term follow-up of the patients with symptomatic spinal stenosis who received surgery in the multicenter randomized trial showed less benefit of surgery between 4 and 8 years, suggesting that the advantage of surgery for spinal stenosis diminishes over time. A Cochrane review of 24 randomized controlled trials of treatments for lumbar spinal stenosis showed that various surgeries including decompression plus fusion and interspinous process spacers were not superior to conventional spinal decompression surgery alone.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• If a patient exhibits radicular or claudication symptoms for longer than 12 weeks.

• MRI or CT confirmation of significant, symptomatic spinal stenosis.

• However, surgery has not been shown to have clear benefit over nonsurgical treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis.

Bagley C et al. Current concepts and recent advances in understanding and managing lumbar spine stenosis. F1000Res. 2019 Jan 31;8:137. [PMID: 30774933]

Cook CJ et al. Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of patient history, clinical findings, and physical tests in the diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis. Eur Spine J. 2020 Jan;29(1):93–112. [PMID: 31312914]

3. Lumbar Disk Herniation

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Pain with back flexion or prolonged sitting.

Pain with back flexion or prolonged sitting.

Radicular pain into the leg due to compression of neural structures.

Radicular pain into the leg due to compression of neural structures.

Lower extremity numbness and weakness.

Lower extremity numbness and weakness.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Lumbar disk herniation is usually due to bending or heavy loading (eg, lifting) with the back in flexion, causing herniation or extrusion of disk contents (nucleus pulposus) into the spinal cord area. However, there may not be an inciting incident. Disk herniations usually occur from degenerative disk disease (dessication of the annulus fibrosis) in patients between 30 and 50 years old. The L5–S1 disk is affected in 90% of cases. Compression of neural structures, such as the sciatic nerve, causes radicular pain. Severe compression of the spinal cord can cause the cauda equina syndrome, a surgical emergency.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Discogenic pain typically is localized in the low back at the level of the affected disk and is worse with activity. “Sciatica” causes electric shock-like pain radiating down the posterior aspect of the leg often to below the knee. Symptoms usually worsen with back flexion such as bending or sitting for long periods (eg, driving). A significant disk herniation can cause numbness and weakness, including weakness of plantar flexion of the foot (L5/S1) or dorsiflexion of the toes (L4/L5). The cauda equina syndrome should be ruled out if the patient complains of perianal numbness or bowel or bladder incontinence.

B. Imaging

Plain radiographs are helpful to assess spinal alignment (scoliosis, lordosis), disk space narrowing, and OA changes. MRI is the best method to assess the level and morphology of the herniation and is recommended if surgery is planned.

Treatment

Treatment

For an acute exacerbation of pain symptoms, bed rest is appropriate for up to 48 hours. Otherwise, first-line treatments include modified activities; NSAIDs and other analgesics; and physical therapy, including core stabilization and McKenzie back exercises. Following nonsurgical treatment for a lumbar disk for over 1 year, the incidence of low back pain recurrence is at least 40% and is predicted by longer time to initial resolution of pain. In a randomized trial, oral prednisone caused a modest improvement in function at 3 weeks, but there was no significant improvement in pain in patients with acute radiculopathy who were monitored for 1 year. The initial dose for oral prednisone is approximately 1 mg/kg once daily with tapering doses over 10–15 days. Analgesics for neuropathic pain, such as the calcium channel alpha-2-delta ligands (ie, gabapentin, pregabalin) or tricyclic antidepressants, may be helpful (see Chapter 5). Epidural and transforaminal corticosteroid injections can be beneficial. A systematic review demonstrated strong evidence that fluoroscopic-guided epidural injections gave short-term benefit (less than 6 months) in acute radicular pain for individuals. However, epidural injections have not shown any change in long-term surgery rates for disk herniations.

The severity of pain and disability as well as failure of conservative therapy were the most important reasons for surgery. A large trial has shown that patients who underwent surgery for a lumbar disk herniation achieved greater improvement than conservatively treated patients in all primary and secondary outcomes except return to work status after 4-year follow-up. Patients with sequestered fragments, symptom duration greater than 6 months, higher levels of low back pain, or who were neither working nor disabled at baseline showed greater surgical treatment effects. Microdiskectomy is the standard method of treatment with a low rate of complications and satisfactory results in over 90% in the largest series. Minimally invasive percutaneous endoscopic spine surgery uses an endoscope to remove fragments of disk herniation (interlaminar or transforaminal approaches) under local anesthesia for the treatment of primary and recurrent disk disease. The most commonly reported complications of endoscopic lumbar surgery include dural tear, infection, and epidural hematoma. Percutaneous endoscopic diskectomy has promise, though there is lack of randomized controlled trials comparing it with open microdiskectomy. Recurrent disk herniations are treated with decompression surgeries and spinal fusion surgeries. Disk replacement surgery has shown benefits in short-term pain relief, disability, and quality of life compared with spine fusion surgery.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Cauda equina syndrome.

• Progressive worsening of neurologic symptoms.

• Loss of motor function (sensory losses can be followed in the outpatient clinic).

Butler AJ et al. Endoscopic lumbar surgery: the state of the art in 2019. Neurospine. 2019 Mar;16(1):15–23. [PMID: 30943703]

Gadjradj PS et al. Management of symptomatic lumbar disk herniation: an international perspective. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017 Dec 1;42(23):1826–34. [PMID: 28632645]

Lee JS et al. Comparison of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar diskectomy and open lumbar microdiskectomy for recurrent lumbar disk herniation. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2018 Nov;79(6):447–52. [PMID: 29241269]

4. Neck Pain

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Chronic neck pain is mostly caused by degenerative joint disease; whiplash often follows a traumatic neck injury.

Chronic neck pain is mostly caused by degenerative joint disease; whiplash often follows a traumatic neck injury.

Poor posture is often a factor for persistent neck pain.

Poor posture is often a factor for persistent neck pain.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Most neck pain, especially in older patients, is due to mechanical degeneration involving the cervical disks, facet joints, and ligamentous structures and may occur in the setting of degenerative changes at other sites. Pain can also come from the supporting neck musculature, which often acts to protect the underlying neck structures. Posture is a very important factor, especially in younger patients. Many work-related neck symptoms are due to poor posture and repetitive motions over time. Acute injuries can also occur secondary to trauma. Whiplash occurs from rapid flexion and extension of the neck and affects 15–40% of people in motor vehicle accidents; chronic pain develops in 5–7%. Neck fractures are serious traumatic injuries acutely and can lead to OA in the long term. Ultimately, many degenerative conditions of the neck result in cervical canal stenosis or neural foraminal stenosis, sometimes affecting underlying neural structures.

Cervical radiculopathy can cause neurologic symptoms in the upper extremities usually involving the C5–C7 disks. Patients with neck pain may report associated headaches and shoulder pain. Both peripheral nerve entrapment and cervical radiculopathy, known as a “double crush” injury, may develop. Thoracic outlet syndrome, in which there is mechanical compression of the brachial plexus and neurovascular structures with overhead positioning of the arm, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of neck pain. Other causes of neck pain include rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, osteomyelitis, neoplasms, polymyalgia rheumatica, compression fractures, pain referred from visceral structures (eg, angina), and functional disorders. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, syringomyelia, spinal cord tumors, and Parsonage-Turner syndrome can mimic myelopathy from cervical arthritis.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

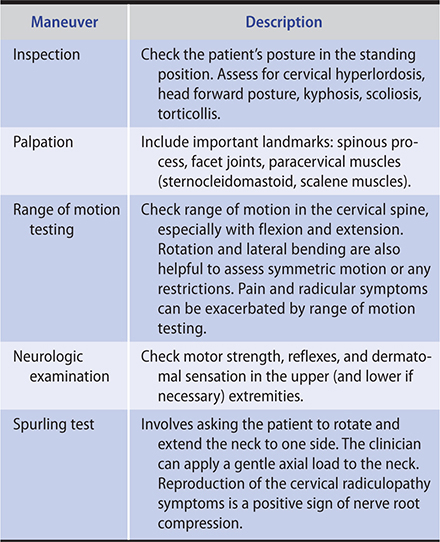

Neck pain may be limited to the posterior region or, depending on the level of the symptomatic joint, may radiate segmentally to the occiput, anterior chest, shoulder girdle, arm, forearm, and hand. It may be intensified by active or passive neck motions. The general distribution of pain and paresthesias corresponds roughly to the involved dermatome in the upper extremity.

The patient’s posture should be assessed, checking for shoulder rolled forward or head forward posture as well as scoliosis in the thoracolumbar spine. Patients with discogenic neck pain often complain of pain with flexion, which causes cervical disks to herniate posteriorly. Extension of the neck usually affects the neural foraminal and facet joints of the neck. Rotation and lateral flexion of the cervical spine should be measured both to the left and the right. Limitation of cervical movements is the most common objective finding.

A detailed neurovascular examination of the upper extremities should be performed, including sensory input to light touch and temperature; motor strength testing, especially the hand intrinsic muscles (thumb extension strength [C6], opponens strength [thumb to pinky] [C7], and finger abductors and adductors strength [C8–T1]); and upper extremity reflexes (biceps, triceps, brachioradialis). True cervical radiculopathy symptoms should match an expected dermatomal or myotomal distribution. The Spurling test involves asking the patient to rotate and extend the neck to one side (Table 41–4). The clinician can apply a gentle axial load to the neck. Reproduction of the cervical radiculopathy symptoms is a positive sign of nerve root compression. Palpation of the neck is best performed with the patient in the supine position where the clinician can palpate each level of the cervical spine with the muscles of the neck relaxed.

Table 41–4. Spine: neck examination.

B. Imaging and Special Tests

Radiographs of the cervical spine include the AP and lateral view of the cervical spine. The odontoid view is usually added to rule out traumatic fractures and congenital abnormalities. Oblique views of the cervical spine can provide further information about arthritis changes and assess the neural foramina for narrowing. Plain radiographs can be completely normal in patients who have suffered an acute cervical strain. Comparative reduction in height of the involved disk space and osteophytes are frequent findings when there are degenerative changes in the cervical spine. Loss of cervical lordosis is commonly seen but is nonspecific.

MRI is the best method to assess the cervical spine since the soft tissue structures (such as the disks, spinal cord, and nerve roots) can be evaluated. If the patient has signs of cervical radiculopathy with motor weakness, these more sensitive imaging modalities should be obtained urgently. CT scanning is the most useful method if bony abnormalities, such as fractures, are suspected.

EMG is useful in order to differentiate peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes from cervical radiculopathy. However, sensitivity of electrodiagnostic testing for cervical radiculopathy ranges from only 50% to 71%, so a negative test does not rule out nerve root problems.

Treatment

Treatment

In the absence of trauma or evidence of infection, malignancy, neurologic findings, or systemic inflammation, the patient can be treated conservatively. More frequent observation of individuals in whom very severe symptoms are present early on after an injury is recommended because high pain-related disability is a predictor of poor outcome at 1 year even if individuals decline care. Ergonomics should be assessed at work and home. A course of neck stretching, strengthening, and postural exercises in physical therapy have demonstrated benefit in relieving symptoms. A soft cervical collar can be useful for short-term use (up to 1–2 weeks) in acute neck injuries. Chiropractic manual manipulation and mobilization can provide short-term benefit for mechanical neck pain. Although the rate of complications is low (5–10/million manipulations), care should be taken whenever there are neurologic symptoms present. Specific patients may respond to use of home cervical traction. NSAIDs are commonly used and opioids may be needed in cases of severe neck pain. Muscle relaxants (eg, cyclobenzaprine 5–10 mg orally three times daily) can be used short term if there is muscle spasm or as a sedative to aid in sleeping. Acute radicular symptoms can be treated with neuropathic medications (eg, gabapentin 300–1200 mg orally three times daily), and a short course of oral prednisone (5–10 days) can be considered (starting at 1 mg/kg). Cervical foraminal or facet joint injections can also reduce symptoms. Surgeries are successful in reducing neurologic symptoms in 80–90% of cases, but are still considered as treatments of last resort. Common surgeries for cervical degenerative disk disease include anterior cervical diskectomy with fusion and cervical disk arthroplasty. A meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials showed that cervical disk arthroplasty was superior to anterior diskectomy and fusion for the treatment of symptomatic cervical disk disease, with better success and less reoperation rates.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Patients with severe symptoms with motor weakness.

• Surgical decompression surgery if the symptoms are severe and there is identifiable, correctable pathology.

Cohen SP et al. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ. 2017 Aug 14;358:j3221. [PMID: 28807894]

Martel JW et al. Evaluation and management of neck and back pain. Semin Neurol. 2019 Feb;39(1):41–52. [PMID: 30743291]

Peng B et al. Cervical discs as a source of neck pain. An analysis of the evidence. Pain Med. 2019 Mar 1;20(3):446–55. [PMID: 30520967]

Sterling M. Best evidence rehabilitation for chronic pain part 4: neck pain. J Clin Med. 2019 Aug 15;8(8):E1219. [PMID: 31443149]

Strudwick K et al. Review article: best practice management of neck pain in the emergency department (part 6 of the musculoskeletal injuries rapid review series). Emerg Med Australas. 2018 Dec;30(6):754–72. [PMID: 30168261]

UPPER EXTREMITY

1. Lateral & Medial Epicondylosis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Tenderness over the lateral or medial epicondyle.

Tenderness over the lateral or medial epicondyle.

Diagnosis of tendinopathy is confirmed by pain with resisted strength testing and passive stretching of the affected tendon and muscle unit.

Diagnosis of tendinopathy is confirmed by pain with resisted strength testing and passive stretching of the affected tendon and muscle unit.

Physical therapy and activity modification are more successful than anti-inflammatory treatments.

Physical therapy and activity modification are more successful than anti-inflammatory treatments.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Tendinopathies involving the wrist extensors, flexors, and pronators are very common complaints. The underlying mechanism is chronic repetitive overuse causing microtrauma at the tendon insertion, although acute injuries can occur as well if the tendon is strained due to excessive loading. The traditional term “epicondylitis” is a misnomer because histologically tendinosis or degeneration in the tendon is seen rather than acute inflammation. Therefore, these entities should be referred to as “tendinopathy” or “tendinosis.” Lateral epicondylosis involves the wrist extensors, especially the extensor carpi radialis brevis. This is usually caused be lifting with the wrist and the elbow extended. Medial epicondylosis involves the wrist flexors and most commonly the pronator teres tendon. Ulnar neuropathy and cervical radiculopathy should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

For lateral epicondylosis, the patient describes pain with the arm and wrist extended. For example, common complaints include pain while shaking hands, lifting objects, using a computer mouse, or hitting a backhand in tennis (“tennis elbow”). Medial epicondylosis presents with pain during motions in which the arm is repetitively pronated or the wrist is flexed. This is also known as “golfer’s elbow” due to the motion of turning the hands over during the golf swing. For either, tenderness directly over the epicondyle is present, especially over the posterior aspect where the tendon insertion occurs. The proximal tendon and musculotendinous junction can also be sore. To confirm that the pain is due to tendinopathy, pain can be reproduced over the epicondyle with resisted wrist extension and third digit extension for lateral epicondylosis and resisted wrist pronation and wrist flexion for medial epicondylosis. The pain is also often reproduced with passive stretching of the affected muscle groups, which can be performed with the arm in extension. It is useful to check the ulnar nerve (located in a groove at the posteromedial elbow) for tenderness as well as to perform a Spurling test for cervical radiculopathy.

B. Imaging

Radiographs are often normal, although a small traction spur may be present in chronic cases (enthesopathy). Diagnostic investigations are usually unnecessary, unless the patient does not improve after up to 3 months of conservative treatment. At that point, a patient who demonstrates significant disability due to the pain should be assessed with an MRI or ultrasound. Ultrasound and MRI can visualize the tendon and confirm tendinosis or tears.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment is usually conservative, including patient education regarding activity modification and management of symptoms. Ice and NSAIDs can help with pain. The mainstay of treatment is physical therapy exercises. The most important steps are to begin a good stretching program followed by strengthening exercises, particularly eccentric ones. Counterforce elbow braces might provide some symptomatic relief, although there is no published evidence to support their use. If the patient has severe or long-standing symptoms, injections can be considered. A randomized trial showed improvement with corticosteroid injection at 1 month as well as evidence of decreased tendon thickness and Doppler changes but no improvement at 3 months. Percutaneous needle tenotomy showed some positive results as an alternative to surgery but lacks demonstrated efficacy in a randomized control study. Evidence on platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections continues to accumulate and it is becoming more commonly used in practice. Reviews suggest that PRP and autologous blood injections both have positive benefits in lateral epicondylitis. In a randomized controlled trial comparing PRP injection to controls (n = 119), the PRP-treated patients reported 55.1% improvement in their pain scores at 12 weeks compared to 47.4% in the control patients (P = 0.163). More significant improvement was seen at 24 weeks; 71.5% improvement in the pain scores in the PRP-treated patients compared to 56.1% in the control patients (P = 0.019). (A 25% improvement of pain symptoms was considered to be clinically significant.) However, the varied methods of PRP preparations and varied post-injection recommendations for rest and physiotherapy make interpretation of various study results difficult to summarize. Compared to ultrasound therapy, extracorporeal shock wave therapy has shown better efficacy for pain relief (as measured with visual analog scales) and better grip strength. However, it is used less commonly than injection treatments and is still considered second-line therapy.

When to Refer

When to Refer

Patients not responding to 6 months of conservative treatment should be referred for an injection procedure (PRP or tenotomy), surgical debridement, or repair of the tendon.

Lai WC et al. Chronic lateral epicondylitis: challenges and solutions. Open Access J Sports Med. 2018 Oct 30;9:243–51. [PMID: 30464656]

Lenoir H et al. Management of lateral epicondylitis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019 Dec;105(8S):S241–6. [PMID: 31543413]

Moradi A et al. Clinical outcomes of open versus arthroscopic surgery for lateral epicondylitis, evidence from a systematic review. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2019 Mar;7(2):91–104. [PMID: 31211187]

Shergill R et al. Ultrasound-guided interventions in lateral epicondylitis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019 Apr;25(3):e27–34. [PMID: 30074911]

Yan C et al. A comparative study of the efficacy of ultrasonics and extracorporeal shock wave in the treatment of tennis elbow: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019 Aug 6;14(1):248. [PMID: 31387611]

2. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Pain, burning, and tingling in the distribution of the median nerve.

Pain, burning, and tingling in the distribution of the median nerve.

Initially, most bothersome during sleep.

Initially, most bothersome during sleep.

Late weakness or atrophy of the thenar eminence.

Late weakness or atrophy of the thenar eminence.

Can be caused by repetitive wrist activities.

Can be caused by repetitive wrist activities.

Commonly seen during pregnancy and in patients with diabetes mellitus or rheumatoid arthritis.

Commonly seen during pregnancy and in patients with diabetes mellitus or rheumatoid arthritis.

General Considerations

General Considerations

An entrapment neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome is a painful disorder caused by compression of the median nerve between the carpal ligament and other structures within the carpal tunnel. The contents of the tunnel can be compressed by synovitis of the tendon sheaths or carpal joints, recent or malhealed fractures, tumors, tissue infiltration, and occasionally congenital syndromes (eg, mucopolysaccharidoses). The disorder may occur in fluid retention of pregnancy, in individuals with a history of repetitive use of the hands, or following injuries of the wrists. Carpal tunnel syndrome can also be a feature of many systemic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic disorders (inflammatory tenosynovitis), myxedema, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, leukemia, acromegaly, and hyperparathyroidism. There is a familial type of carpal tunnel syndrome in which no etiologic factor can be identified.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

The initial symptoms are pain, burning, and tingling in the distribution of the median nerve (the palmar surfaces of the thumb, the index and long fingers, and the radial half of the ring finger). Aching pain may radiate proximally into the forearm and occasionally proximally to the shoulder and over the neck and chest. Pain is exacerbated by manual activity, particularly by extremes of volar flexion or dorsiflexion of the wrist. It is most bothersome at night. Impairment of sensation in the median nerve distribution may or may not be demonstrable. Subtle disparity between the affected and opposite sides can be shown by testing for two-point discrimination or by requiring the patient to identify different textures of cloth by rubbing them between the tips of the thumb and the index finger. A Tinel or Phalen sign may be positive. A Tinel sign is tingling or shock-like pain on volar wrist percussion. The Phalen sign is pain or paresthesia in the distribution of the median nerve when the patient flexes both wrists to 90 degrees for 60 seconds. The carpal compression test, in which numbness and tingling are induced by the direct application of pressure over the carpal tunnel, may be more sensitive and specific than the Tinel and Phalen tests. Muscle weakness or atrophy, especially of the thenar eminence, can appear later than sensory disturbances as compression of the nerve worsens.

B. Imaging

Ultrasound can demonstrate flattening of the median nerve beneath the flexor retinaculum. Sensitivity of ultrasound for carpal tunnel syndrome is variable but estimated between 54% and 98%.

C. Special Tests

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies show evidence of sensory conduction delay before motor delay, which can occur in severe cases. Electrodiagnosis can provide information on focal median mononeuropathy at the wrist and can classify carpal tunnel syndrome from mild to severe.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment is directed toward relief of pressure on the median nerve. When a causative lesion is discovered, it should be treated appropriately. Otherwise, patients in whom carpal tunnel syndrome is suspected should modify their hand activities. The affected wrist can be splinted in the neutral position for up to 3 months, but a series of Cochrane reviews show limited evidence for splinting, exercises, and ergonomic positioning. Moderate evidence supported benefit from several physical therapy and electrophysical modalities (eg, ultrasound therapy and radial extracorporeal shockwave therapy). These modalities provided short-term and mid-term relief of carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms in different studies. Oral corticosteroids or NSAIDs have also shown benefit for carpal tunnel syndrome. Methylprednisolone injections were found to have more effect at 10 weeks than placebo, but the benefits diminished by 1 year.

Compared to trigger finger management, which usually includes injections, as many as 71% of patients with carpal tunnel directly undergo surgery without first getting injections. There is strong evidence that a steroid injection to the carpal tunnel is more effective in the short term than surgery. A randomized, controlled trial showed both corticosteroid injection and surgery resolved symptoms but only decompressive surgery led to resolution of neurophysiologic changes. Carpal tunnel release surgery can be beneficial if the patient has a positive electrodiagnostic test, at least moderate symptoms, high clinical probability, unsuccessful nonoperative treatment, and symptoms lasting longer than 12 months. Surgery can be done with an open approach or endoscopically, both yielding similar good improvements.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• If symptoms persist more than 3 months despite conservative treatment, including the use of a wrist splint.

• If thenar muscle (eg, abductor pollicis brevis) weakness or atrophy develops.

Huisstede BM et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome: effectiveness of physical therapy and electrophysical modalities. An updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018 Aug;99(8):1623–34. [PMID: 28942118]

Huisstede BM et al. Effectiveness of surgical and postsurgical interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome—a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018 Aug;99(8):1660–80. [PMID: 28577858]

Petrover D et al. Ultrasound-guided surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome: a new interventional procedure. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2018 Oct;35(4):248–54. [PMID: 30402007]

Urits I et al. Recent advances in the understanding and management of carpal tunnel syndrome: a comprehensive review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019 Aug 1;23(10):70. [PMID: 31372847]

Wang L. Guiding treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2018 Nov;29(4):751–60. [PMID: 30293628]

3. Dupuytren Contracture

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Benign fibrosing disorder of the palmar fascia.

Benign fibrosing disorder of the palmar fascia.

Contracture of one or more fingers can lead to limited hand function.

Contracture of one or more fingers can lead to limited hand function.

General Considerations

General Considerations

This relatively common disorder is characterized by hyperplasia of the palmar fascia and related structures, with nodule formation and contracture of the palmar fascia. The cause is unknown, but the condition has a genetic predisposition and occurs primarily in white men over 50 years of age, particularly in those of Celtic descent. The incidence is higher among alcoholic patients and those with chronic systemic disorders (especially cirrhosis). It is also associated with systemic fibrosing syndrome, which includes plantar fibromatosis (10% of patients), Peyronie disease (1–2%), mediastinal and retroperitoneal fibrosis, and Riedel struma. The onset may be acute, but slowly progressive chronic disease is more common.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Dupuytren contracture manifests itself by nodular or cord-like thickening of one or both hands, with the fourth and fifth fingers most commonly affected. The patient may complain of tightness of the involved digits, with inability to satisfactorily extend the fingers, and on occasion there is tenderness. The resulting cosmetic problems may be unappealing, but in general the contracture is well tolerated since it exaggerates the normal position of function of the hand.

Treatment

Treatment

The literature is still limited to direct the best option for Dupuytren contracture. Corticosteroid injection with a percutaneous needle aponeurotomy, collagenase Clostridium histolyticum injections, and open fasciectomy are common treatment options. If the palmar nodule is growing rapidly, injections of triamcinolone or collagenase into the nodule may be of benefit; the injection of collagenase C histolyticum lyses collagen, thereby disrupting the contracted cords. Surgical options include open fasciectomy, partial fasciectomy, or percutaneous needle aponeurotomy and are indicated in patients with significant flexion contractures. A multicenter study showed that collagenase injection and limited fasciectomy had similar improvements with contractures at the metacarpophalangeal joints, while surgery had better results for contractures involving the proximal interphalangeal joints. Splinting after surgery is beneficial. Recurrence is possible after surgery with more adverse events compared to nonoperative treatments. Compared to placebo, tamoxifen therapy produced moderate evidence of improvement before or after a fasciectomy.

When to Refer

When to Refer

Referral can be considered when one or more digits are affected by severe contractures, which interfere with everyday activities and result in functional limitations.

Huisstede BM et al. Effectiveness of conservative, surgical, and postsurgical interventions for trigger finger, Dupuytren disease, and De Quervain disease: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018 Aug;99(8):1635–49. [PMID: 28860097]

Sanjuan-Cervero R. Current role of the collagenase Clostridium histolyticum in Dupuytren’s disease treatment. Ir J Med Sci. 2020 May;189(2):529–34. [PMID: 31713028]

Soreide E et al. Treatment of Dupuytren’s contracture: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2018 Sep;100-B(9):1138–45. [PMID: 30168768]

4. Bursitis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Often occurs around bony prominences where it is important to reduce friction.

Often occurs around bony prominences where it is important to reduce friction.

Typically presents with local swelling that is painful acutely.

Typically presents with local swelling that is painful acutely.

Septic bursitis can present without fever or systemic signs.

Septic bursitis can present without fever or systemic signs.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Inflammation of bursae—the synovium-like cellular membranes overlying bony prominences—may be secondary to trauma, infection, or arthritic conditions such as gout, rheumatoid arthritis, or OA. Bursitis can result from infection. The two common sites are the olecranon (Figure 41–1) and prepatellar bursae; however, others include subdeltoid, ischial, trochanteric, and semimembranosus-gastrocnemius (Baker cyst) bursae. The bursitis can be septic. Aseptic bursitis is usually afebrile.

Figure 41–1. Chronic aseptic olecranon bursitis without erythema or tenderness. (Used, with permission, from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Bursitis presents with focal tenderness and swelling and is less likely to affect range of motion of the adjacent joint. Olecranon or prepatellar bursitis, for example, causes an oval (or, if chronic, bulbous) swelling at the tip of the elbow or knee and does not affect joint motion. Tenderness, erythema and warmth, cellulitis, a report of trauma, and evidence of a skin lesion are more common in septic bursitis but can be present in aseptic bursitis as well. Patients with septic bursitis can be febrile but the absence of fever does not exclude infection; one-third of those with septic olecranon bursitis are afebrile. A bursa can also become symptomatic when it ruptures. This is particularly true for Baker cyst, the rupture of which can cause calf pain and swelling that mimic thrombophlebitis.

B. Imaging

Imaging is unnecessary unless there is concern for osteomyelitis, trauma, or other underlying pathology. Ruptured Baker cysts are imaged easily by sonography or MRI. It may be important to exclude a deep venous thrombosis, which can be mimicked by a ruptured Baker cyst.

C. Special Tests

Acute swelling and redness at a bursal site call for aspiration to rule out infection especially if the patient is either febrile (temperature more than 37.8°C) or has prebursal warmth (temperature difference greater than 2.2°C) or both. A bursal fluid white blood cell count of greater than 1000/mcL indicates inflammation from infection, rheumatoid arthritis, or gout. The bursal fluid of septic bursitis characteristically contains a purulent aspirate, fluid-to-serum glucose ratio less than 50%, white blood cell count more than 3000 cells/mcL, polymorphonuclear cells more than 50%, and a positive Gram stain for bacteria. Most cases are caused by Staphylococcus aureus; the Gram stain is positive in two-thirds.

Treatment

Treatment

In general, aspiration and corticosteroid injections in mild, nonseptic bursitis should be avoided to reduce complications of iatrogenic infection and skin atrophy. Bursitis caused by trauma responds to local heat, rest, NSAIDs, and local corticosteroid injections. Repetitive minor trauma to the olecranon bursa should be eliminated by avoiding resting the elbow on a hard surface or by wearing an elbow pad. For chronic aseptic bursitis or when there are athletic or occupational demands, aspiration with intrabursal steroid injection can be performed. Ultrasound-guided aspiration and injection can improve the accuracy of the procedures. Treatment of a ruptured Baker cyst includes rest, leg elevation, and possibly injection of triamcinolone, 20–40 mg into the knee anteriorly (the knee compartment communicates with the cyst).

Treatment for septic bursitis involves incision and drainage and antibiotics usually delivered intravenously, especially against S aureus.

When to Refer

When to Refer

• Surgical removal of the bursa is indicated only for cases in which infections occur.

• Elective surgical removal can be considered for persistent symptoms affecting activities of daily living.

Khodaee M. Common superficial bursitis. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Feb 15;95(4):224–31. [PMID: 28290630]

Raas C et al. Treatment and outcome with traumatic lesions of the olecranon and prepatellar bursa: a literature review apropos a retrospective analysis including 552 cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017 Jun;137(6):823–7. [PMID: 28447166]

HIP

1. Hip Fractures