Democracy and democratic institutions

Winston Churchill famously quipped, ‘Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.’ Ideally, democracy is a system that enables citizens to decide the way in which their society is organized and governed, a government ‘of, by and for the people’, (see here) but how far modern forms of democracy have achieved this in practice is debatable, and varies from state to state.

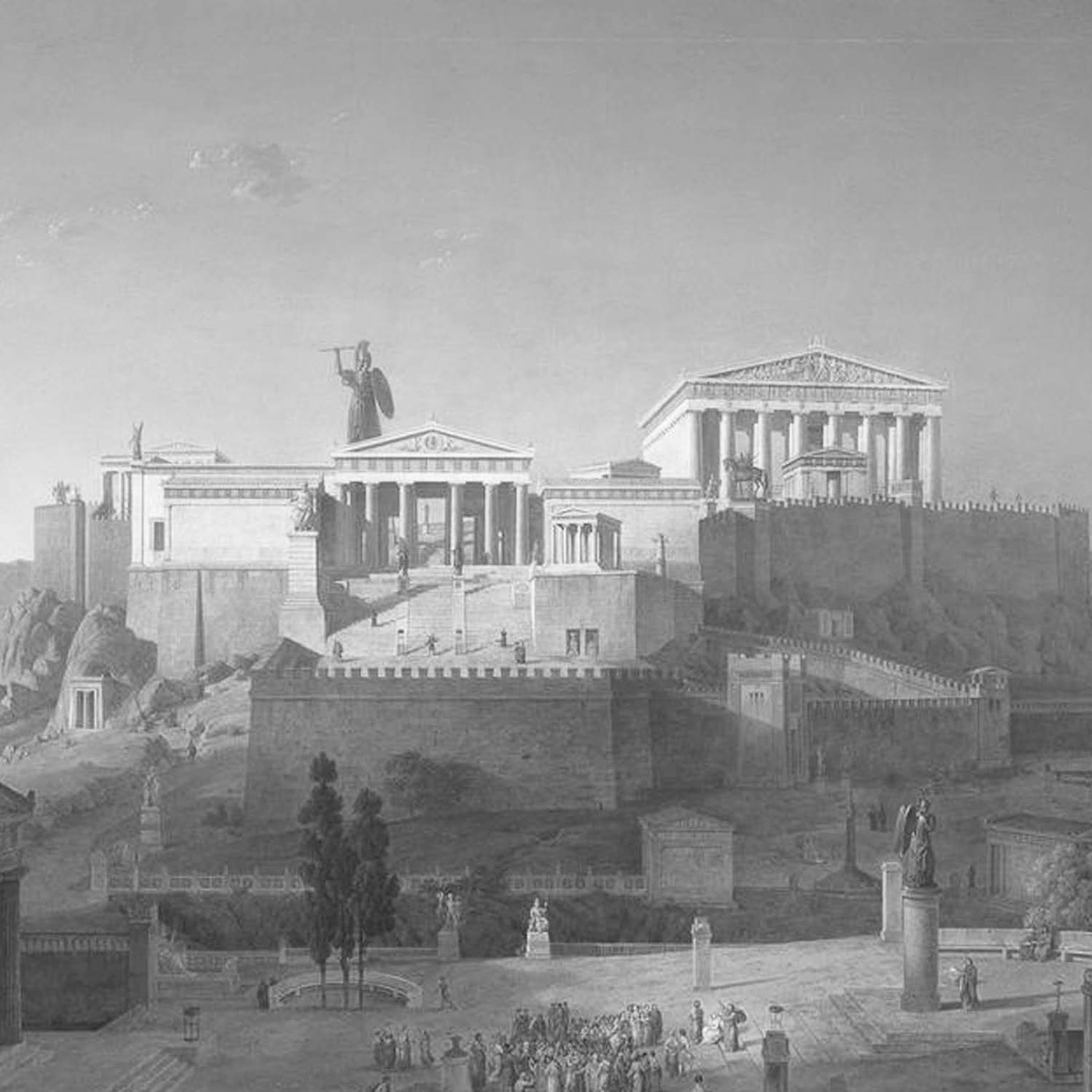

The original Ancient Greek model of democracy, in which all eligible citizens participated directly in decision-making, would be impracticable in most societies, and so has been modified to a system of representatives elected by popular vote. The disadvantage, as some critics have pointed out, is that it runs the risk of merely legitimizing a small ruling elite. To minimize this risk, most democracies have strict and often complex legal frameworks based on a constitution, setting out the powers and limitations of governments and how they are elected.

The idea that the people of a society should have the power to determine the way it is governed is the basis for all democratic systems. However, based on the wishes of the majority of the people, it may ignore or even contradict the wishes and rights of the minority, and may result in what Marx and Engels described as the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’. It could also be argued that the majority of people are not qualified to make important decisions of government.

Advocates of representative democracy counter that we can elect the most able to govern on our behalf. Power of government, although granted to a minority, can only be granted by the people, to whom those elected representatives are accountable. The British socialist politician Tony Benn neatly encapsulated the essence of representative democracy in five questions for those in power: What power have you got? Where did you get it from? In whose interest do you exercise it? To whom are you accountable? How can we get rid of you?

The cornerstone of modern democracy is the notion that citizens can participate in the political process by having the right to vote in elections. For modern democracies, this implies universal suffrage, giving all citizens over a certain age an equal vote. This has not always been the case – women were only reluctantly given the vote from the end of the 19th century, and eligibility for male voters has been conditional on status, education or property ownership. Nowadays, universal suffrage is taken to mean the enfranchising of every adult citizen, regardless of sex, social standing, religion or political persuasion. There are still, however, some who are legally excluded in many countries, including the insane and those serving prison sentences. Then there are those disenfranchised by the processes of registering their right to vote, which often exclude the disadvantaged, such as homeless, illiterate, disabled or unemployed people, or recent immigrants. Conversely, voting is seen in many places as a civic duty rather than a right and in some countries is compulsory.

For a democracy to be a true reflection of the wishes of its citizens, there have to be regular opportunities for them to vote in elections. This is often enshrined in the constitution, which specifies either a fixed term of office for a national government, or at least a maximum length of time before an election is called. With regular national elections, perhaps every three or five years, the government is made accountable to the electorate. Typically, a country is divided into electoral districts or constituencies, which elect representatives to seats in a parliament or assembly for that term of office, but in some circumstances, such as the death of a representative, a local by-election will be held. Of course, citizens can be involved in political activity at any time, but it is only in these elections that the voter actually has a say in government. Increased use of referendums on constitutional or urgent matters, and the right for voters in an electoral district to call a vote of no confidence in an elected representative have been suggested as ways of improving voter involvement between elections.

In representative democracies, any person who is eligible to vote is also eligible to stand for election, but few independent citizens do. Instead, candidates tend to have the backing of a political party, and are appointed or elected to stand by the party membership. The system of political parties has evolved around groups sharing distinct political ideologies, and their candidates stand on a ‘platform’ of their party’s proposed policies. The number of seats won by each party nationally determines the ruling party. In states with only two major parties a simple majority decides which is government and which opposition, but alliances can be made to form a coalition government in parliaments and assemblies that contain a number of parties. What marks democracy from totalitarianism and dictatorship is the choice of views available to the electorate, and the freedom of political parties to represent this range of opinion. However, certain parties have been outlawed if they represent dangerously extremist views or have links with terrorist or criminal organizations.

The process of electing representatives varies enormously from country to country. Some elections are for individual candidates on a ‘first-past-the-post’ basis, where the winner is simply the one with the most votes. But this can mean that minority parties never manage to gain an elected representative, despite having a proportion of popular support; and some candidates may be elected on substantially less than 50 per cent of the vote, implying that more people voted against than for them. So more complex systems of proportional representation, reflecting voter preferences, have been devised – although they are not without their critics. The leaders of parties are generally chosen by the party membership, rather than the population as a whole. Voters vote for the party of their choice, and the leader of the winning party generally becomes the prime minister or leader of the legislature. Presidents are typically elected separately from the members of the legislature, either by a direct popular election or as in the USA indirectly by a system of electoral colleges.

Presidential elections in the USA.

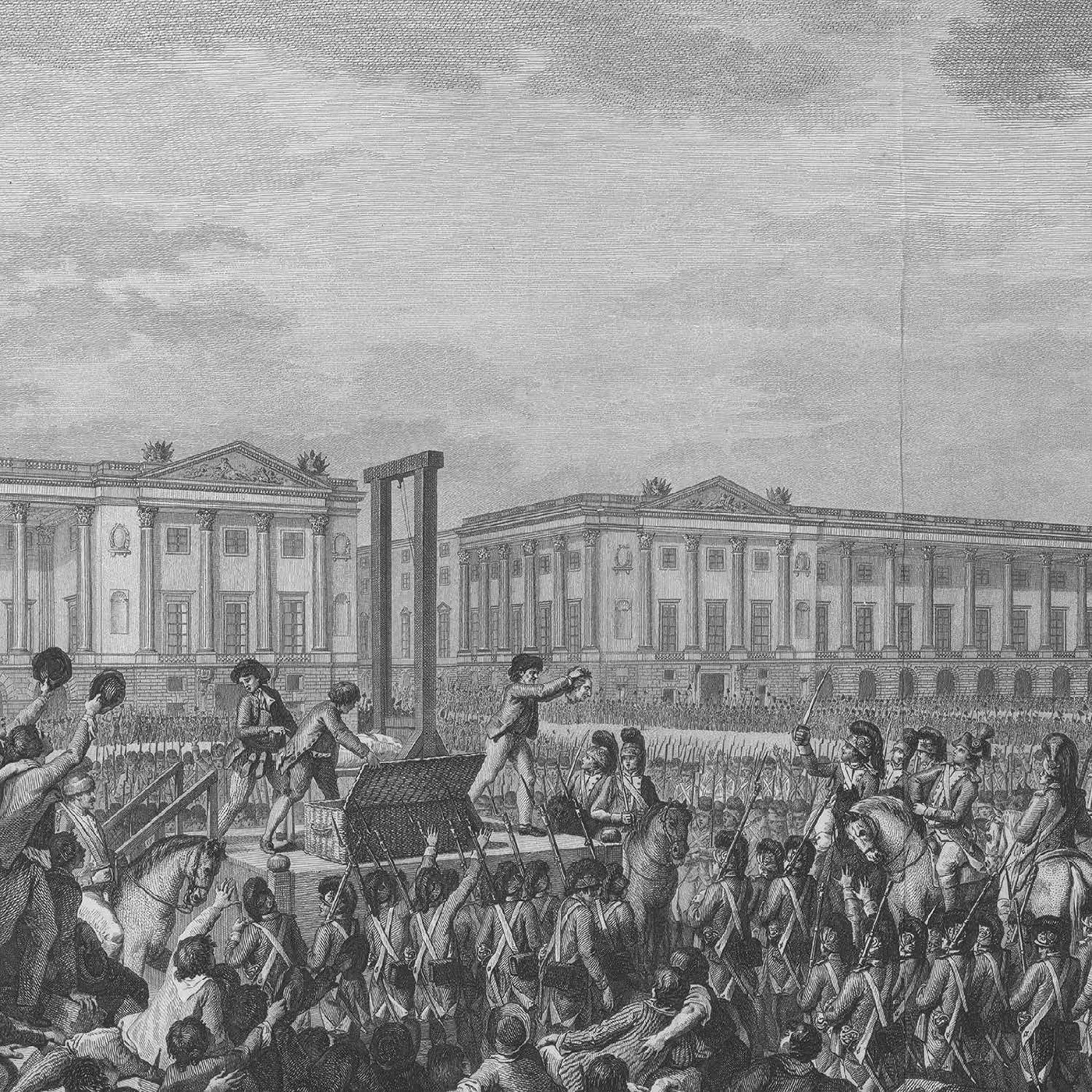

The term ‘republic’ can be used to describe any number of different types of state governed by elected leaders rather than a hereditary monarchy or dictatorship. As such, all republics are to a greater or lesser extent democratic states by definition. But not all democracies choose to call themselves ‘republic’, and many are at least nominally monarchies. Like democracy itself, republics have roots in the Ancient Greek and Roman states that for a time displaced the old kingdoms. Although some republican city-states were established in the Renaissance period, it wasn’t until the late 18th century that absolute monarchies began to be replaced by national republics. Some 200 years later, they are the most common form of government. Some of the older nations retain royal families with no real political power alongside democratically elected parliaments in a ‘constitutional monarchy’. One of the oldest of these, Britain, was for a time a republican-style ‘Commonwealth’, but actually restored its monarchy, albeit with greater powers retained by the Parliament.

Despite the almost universal rejection of absolute monarchy in favour of democracy, and antipathy to any form of tyrannical dictatorship, it seems that human nature favours some form of leadership. This is reflected in the models of representative democracy that have evolved, which almost invariably include the election of a single leader, such as a prime minister or president.

In a presidential system of government, the president is elected separately from the legislative body. Often this is a position of real power and responsibility, with the president acting as head of the executive branch of the government. As the chief executive, he or she plays an active role in the government of the country, often appointing ministers who similarly belong to the executive and oversee government departments. Some countries, however, have an essentially parliamentary system (see here), in which the president is an honorary head of state with little or no real power.

In many older democracies, the system of government evolved as power was gradually shifted from the monarchy to a parliament. Britain is the prime example of such a parliamentary government, which has served as a model for many other parliaments around the world. While a parliamentary democracy may have either a hereditary monarch or an elected president as nominal head of state, the executive power usually rests with a prime minister and cabinet or council of ministers, often referred to simply as ‘the government’, who are also members of the parliament.

In practice, the cabinet can only operate with the support of a majority of the parliament. The policy and decision-making of the cabinet of ministers requires the endorsement of parliament, without which it cannot pass laws. And, if the cabinet or prime minister no longer have the support of a majority of the parliament, there may be mechanisms allowing a vote of no confidence that can remove them from power.

The legislature or parliament in most democratic countries is divided into two houses, or chambers. The two-chamber, or bicameral, system evolved from the medieval European parliaments, which had separate assemblies for the aristocracy and the commoners. Some modern democracies still have unelected upper houses, with appointed or hereditary members, while presidential republics tend to have two houses with roughly equal powers but elected in different ways, such as the US Senate and House of Representatives.

The advantage of the bicameral system is in the enactment of laws, which requires the approval of both chambers. This helps to provide a moderating force of ‘checks and balances’ that prevent bad laws from being passed. Although bicameralism is widely considered an important feature of democratic government, there are some who point out that it often acts as an obstacle to radical legislation, and so can prevent necessary political reform.

President Obama addresses a joint session comprising both houses of the US Senate.

In parliamentary systems, the executive branch of government – the part that carries out the laws made by parliament – is overseen by ministers who together form a cabinet or council of ministers. The functions of the cabinet differ from country to country, ranging from a mainly advisory role to the head of government, to a policy- and decision-making group that effectively is the government.

Normally, ministers are appointed by the prime minister from the elected members of parliament, and given responsibility for different government departments. Among the most important members of the cabinet are the ministers for foreign and domestic affairs (known in the UK as Foreign and Home Secretaries), and the minister of finance (Chancellor of the Exchequer). In a presidential system, however, the ministers are not members of the legislative assembly. Lacking the same collective executive power, they act instead as advisors to the president, or as chief executives of their departments.

An important principle of democracy is the clear distinction between different branches of government – the legislature, the executive and the judiciary – and the separation of their powers. If these institutions of government, each with specific responsibilities and powers, function independently no single branch can exercise absolute power. The role of the legislature is to make the laws, the executive to carry them out and the judiciary to decide when they have been broken.

The theory of separation of powers is most strictly adhered to in republics such as the USA, where the executive branch of government is identified with the president, the head of state, the legislature with the Senate and House of Representatives, and the judiciary with the courts. In practice, however, the three branches of government are interlinked in presidential governments, and are even more closely tied in parliamentary systems, where the prime minister and cabinet have executive power and are at the same time part of the legislature.