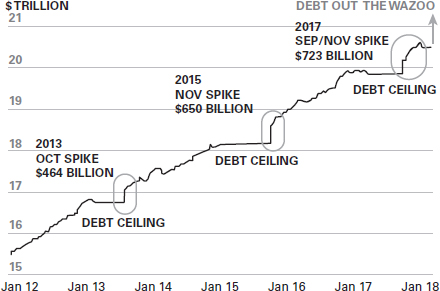

Figure 2.2 US national debt – $617 billion spike in five months

Source: US Treasury, Wolf Street, wolfstreet.com/2018/01/30/us-national-debt-will-jump-by-617-billion-in-5-months

This is, of course, specific to the United States, but everywhere debt is the defining characteristic of our times. Why? Some say debt is always wrong, but to the leader it can be wrong while also being right. There’s efficient and inefficient debt.29 If interest rates are lower than profit levels percentage-wise, then debt is efficient. Where profitability is lower than interest rates, it’s inefficient. In theory, in the former case, the more leverage, the more profit. The same can be said of national economies where GDP is growing ahead of interest rates. This only really applies in times when interest rates have been at record low levels. This is why some say borrowing at record low interest rates makes no sense if you already have a debt problem, while others say that it is crazy to not borrow more when interest rates are so low. Can you solve a debt problem by taking on more debt? Economists deeply disagree on this.

The problem with debt is that it’s easy to get into and hard to get out of. This is especially true of governments with an essentially short-term view, ie to the next election. At the national economic level, there are several known methods for dealing with debt. Let’s look at a few.

First, a nation can say it will never pay it back. This is called an Argentine-style default. No-one will ever lend to you again after this, unless it’s at silly-stupid rates. Second, they can say the nation will pay it back, but later and less. This is called a haircut, and Greece has defaulted on much of its national debt this way. It pushes the payments further into the future, which means the original bondholders are defaulted upon. Third, nations can pursue austerity. This means the state will deliver less to their voters and/or tax them more. Fourth, the economy could simply grow its way out of debt. This is possible. It’s what happened during the Industrial Revolution, but it is very hard to do.

Last, politicians can announce that they will permit higher inflation. This erodes debt. It is an implicit and surreptitious tax. This option means the lenders get their money back, but it’s worth less than before. And now for the big one! We can abandon the entire system of money, currency and accounting altogether and introduce a new one. More about this possibility later in the chapter.

Nothing new under the sun

Creative thinkers always come with one simple conceit. They believe there’s genuinely such a thing as a brand-new idea – there isn’t. There’s just the history they don’t yet know. All ideas have been done before, but the context is often fresh.

This is not the first time countries have been in debt. For instance, the United States dealt with the accumulated debts from the American Revolution by inflating the value of the Colonial currency by printing ever more notes, which were known as the ‘Continentals’.30 So many were issued that all confidence in their value was lost. They became worthless, which led to the saying ‘Not worth a Continental’. This happened again during the Civil War. The war debts disappeared when the United States effectively defaulted when inflation reached more than 5,000 per cent. Similarly, many investors believe the United States defaulted on the debts it accumulated in the 1960s. The cost of the war in Vietnam and the cost of the Great Society Program exceeded the capacity to repay. Figure 2.3 shows the various periods where the United States escaped a debt problem by inflating the currency.