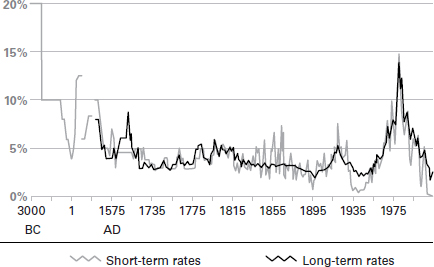

Figure 2.4 Short- and long-term interest rates

Note: the intervals on the x-axis change through time up to 1715. From 1715 onwards, the intervals are every 20 years. Prior to the 18th century, the rates reflect the country with the lowest rate reported for each type of credit: 3000 BC to 6th century BC – Babylonian empire; 6th century BC to 2nd century BC – Greece; 2nd century BC to 5th century AD – Roman Empire; 6th century BC to 10th century AD – Byzantium (legal limit); 12th century AD to 13th century AD – Netherlands; 13th century AD to 16th century AD – Italian states. From the 18th century, the interest rates are of an annual frequency and reflect those of the most dominant money market: 1694 to 1918 this is assumed to be the United Kingdom; from 1919 to 2015 this is assumed to be the United States. Rates used are as follows: Short rates: 1694–1717 – Bank of England Discount rate; 1717–1823 rate on 6-month East India bonds; 1824–1919 rate on 3-month prime or first-class bills; 1919–1996 rate on 4–6-month prime US commercial paper; 1997–2014 rate on 3-month AA US commercial paper to non-financials. Long rates: 1702–1919, rate on long-term government UK annuities and consols; 1919–1953, yield on long-term US government bond yields; 1954–2014, yield on 10-year US treasuries

Source: Homer, S and Sylla, R (1991) A history of interest rates, Wiley; Heim, C and Mirowski, P (1987) Interest rates and crowding-out during Britain’s industrial revolution, Journal of Economic History, 47, pp 117–39; Weiller, K and Mirowski, P (1990) Rates of interest in 18th century England, Explorations in Economic History, 27 (1); Hills, S, Thomas, R and Dimsdale, N (2010) The UK recession in context – what do three centuries of data tell us?, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Q4; Bank of England, Historical Statistics of the United States Millennial Edition (https://hsus.cambridge.org/HSUSWeb/HSUSEntryServlet), and Federal Reserve Economic Database (https://fred.stlouisfed.or).

The purpose was specifically to raise the inflation rate, in a bid to prevent further asset deflation from occurring. It has worked in the sense that asset prices have risen. Inflation has occurred in everything from property to paintings. Stock markets in the United States, Britain, all of Europe and across many parts of the world are at record highs in early 2018. The CPI data across most economies is now rising as well, albeit slowly and from a low base. In 2018, we now see inflation rising in the United States, the United Kingdom, the EU, Japan, China and elsewhere, but as we’ve established, it comes cleverly disguised.

In office, but not in power

Central bankers scoff at the notion that we might repeat severe inflationary episodes, especially considering the record debt burden. Some take the view that we should be lucky to get a bit more inflation. Others argue it may be the only way to escape the debt burden. Today’s central bankers also have a high degree of confidence, even hubris, on this subject. They genuinely believe that they can control the temperature dial of inflation through interest rates. Dial it up and inflation drops, and vice versa. But what if they are reading the wrong dial? The problem is a lack of joined-up thinking. They only consider their policy tools and their areas of interest. They do not consider other contributing forces. Let’s look at all the inflationary items that are not controlled by central bankers:

- Increased defence spending (which is a new wave of capital, just like quantitative easing)

- The Chinese investment in the Belt Road Initiative

- Rising wages in China

- New cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.

These are offset by some deflationary issues, which are also beyond their control, including:

- Falling energy costs

- Internet competition

- Debt (private and public sector)

- Countries holding US dollars in order to keep their currency competitive.

We know central bankers are more afraid of deflation than inflation. They prefer taking more risks with inflation to offset the risk of deflation. This means raising interest rates slowly and in small steps, while warning the markets well in advance. At best, the small and occasional rate hikes are a means of gently normalizing interest rates back to more typical levels. The markets tend to rise on such hikes because they confirm that economies are stronger.

Will such hikes save us from higher inflation? It is worth considering the opinion of Paul Volcker, Chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1987. He slew the inflation dragon during that period by raising interest rates to 21 per cent – harsh medicine indeed. In May 2013 he told the Economic Club of New York: ‘All experience amply demonstrates that inflation, when deliberately started, is hard to control and reverse.’32 Today’s central bankers seem to think Mr Volcker and his views are irrelevant.

The problem with their thinking is that things have changed since 2008. First, workers in China, and other emerging markets, are no longer willing to work for ever less pay. They have been demanding steadily higher wages, not lower ones. Asian workers are enjoying the highest wage increases anywhere in the world now.33 According to Forbes, some Chinese wages now exceed European wages.34 Today the only major emerging market that undercuts China on wages is Mexico. Its wages are 20 to 40 per cent lower than China and their quality control is US standard.

Manufacturers in emerging markets, other than Mexico, are increasingly moving their operations back to the West. In September 2017, even Foxconn, the second-largest employer in China, announced its intention to build a manufacturing facility in Wisconsin.35 When Wisconsin beats Shenzhen, something important is happening. The loss of competitiveness in low-value goods is forcing China to move up the ladder into products that can far better sustain long-term economic growth. It explains why they are keen to make higher-value products such as superfast trains and the railways associated with them, as well as small nuclear plants. On top of this, China is also investing $3 trillion+ in its Belt Road Initiative – another major injection of capital into the world’s economy.

Is the internet deflationary or inflationary?

Most economists are very certain that the internet is deflationary. It encourages competition, and that brings prices down. It makes supply chains more efficient and makes it easier to find the lowest prices. It is obvious to them that the internet is deflationary because it increases productivity. The advent of the internet has also coincided with several other deflationary events and forces that may mask the underlying deflationary pressures.

For example, when Paul Volcker committed to higher interest rates in 1982, the shock slowed inflation. Then, in 1989, the Soviet Union ceased to exist and the Berlin Wall fell. This was a hugely deflationary event because workers from emerging markets began to systematically push down wages and prices. Shortly after this, the Cold War ended. This was an added deflationary force because defence spending was cut, the reverse multiplier effect kicked in. All that capital could now be redeployed from weapons spending into more productive uses.

Furthermore, the big expansion of the internet happened with the introduction of the iPhone in 2007. A 2016 headline from Forbes magazine declared: ‘How the Internet Economy Killed Inflation’.36 It’s easy to see why people think inflation is over after such a long string of deflationary shocks. Also, it’s now been over 10 years since governments added all that stimulus to the world economy. Many might say it simply didn’t work. It may have staved off the possibility of another Great Depression but it has not unleashed inflation. So, there is little to worry about, right? Yet, in 2018, the Cambridge Analytica scandal revealed that Facebook makes its money from selling data. People were outraged. Mark Zuckerberg’s response was simple. If we cannot make money on advertising, then we have to charge you to use Facebook. He was suggesting a potential price hike from zero to something. Remember that Facebook is a virtual monopoly. That’s the internet showing it can be inflationary too. The point is that we find it very easy to assume that the internet is always a deflationary force, even though, sometimes, it might not be.

Time to get nerdy

But what do our economists really know? We know they missed most of the big events in the economy. We might also wonder whether they’ve measured the economy correctly. We know they use mainly historic data. We know they were wrong about the financial crisis, Brexit, the slowdown in China and many election results. So, here’s a question. What if the internet increases the volume of money, its velocity and the number of transactions?

Economists use an equation, which is at the heart of quantitative easing and crude monetarism (known as the quantity theory of money), as follows:

MV = PT

Where,

- M is the quantity of money in the system

- V is the velocity that money flows around the economy

- P is the level of prices

- T is the number of transactions

You don’t need to be an economist to work out that the internet is potentially inflationary in just about every way. This is because the volume of money (M) and prices (P) are both multiples of the speed of money (V) and the volume of transactions (T).

At a time when the internet is structurally changing the global economy, what have national governments been doing? They have been buying their own bonds. They have been spending on defence. This also has the effect of raising M, so if V was fixed, it would push up P or T or both.

QUICK TIP In economic terms, leaders should see the internet as transformational, not merely transactional. It’s not just an infrastructure, it’s also a way of multiplying money supplies through crowdfunding, mobile phone payments and internet currencies, for example.

The problem is that throughout history, it’s been difficult to measure the volume and velocity of money. It used to be measured in savings and cheque accounts. Then, the measure included credit cards. Today, crowdfunding, mobile phone payment systems and cryptocurrencies are widely used but not included. Central bankers try to keep up by widening the definition of the volume of money. M1 was called narrow money and included notes and coins in circulation and bank deposits. Then we had M2 and M3, which added in longer-dated deposits and money market funds. The US Federal Reserve Bank stopped measuring M3 in 2006 because it was such a useless measure of reality. Today, the volume of money keeps expanding into entirely new and difficult-to-measure forms. So, now we tend to refer to MZM, which broadly means everything except what can’t be measured. There’s quite a lot of this, including all the forms of money that technology is creating.

We talked in Chapter 1 about a lack of joined-up thinking. Monetary policy, then, when viewed in isolation away from geopolitics and technical change, can be seen as an example of the worst type of narrow, analytical, reductionist thinking.

The ultimate solution to inflation – smash it up

Governments can, of course, hope the economy just grows its way out of the debt problem. This is what happened at the start of the Industrial Revolution. After decades of Napoleonic warfare, Britain had racked up debts that seemed entirely insurmountable. The government took a decision to radically change the system of money to stimulate the economy and erode the debt with inflation.

That system was based on tally sticks, which hardly anybody remembers now. These were wooden boards made of willow, pine or hazel, roughly cracked in half so that the two sides would perfectly and uniquely match. The matching grain in the wood served as a reliable watermark. Then every asset sale and purchase, tax payment and loan was recorded on both sides of the wooden ledger. The smaller and narrower side always went to the borrower and led to our phrase ‘getting the short end of the stick’. The longer stick, or stock, always went to the lender, hence the terms ‘stockholder’ and ‘stock market’. Holes in the boards indicated your worth. A palm-sized hole equalled £1,000. A thumb-sized hole equalled £100. We get the phrase to ‘tally something up’ from these sticks. They decommissioned the system in 1783 to introduce a new innovation – paper money. Why paper? Because it permitted inflation to help erode the war debts. Nobody trusted bits of paper, though. So, people kept making and using the sticks. By 1834, the government was frustrated, made the whole system illegal and confiscated the sticks. They were brought to parliament where they were burnt on the night of 16 October 1834. Unfortunately, it was one of those occasions where the event and metaphor fused. The fire got out of hand. Parliament burnt down. J M W Turner captured the event in his painting The Burning of Parliament. Shortly after that, the Industrial Revolution took hold and Britain grew its way out of the debt.

Cryptocurrencies

This is exactly what many governments are hoping to do today. We already know the name of the new system of money, called electronic money. The new system of accounting is already known as ‘blockchain’. The combination of the two new technologies is set to radically transform the economy, just as in the early 1800s. Already central bankers are warning about the lack of control inherent in such cryptocurrencies. This may be because they are the ones who wish to issue and control them.37

There are now well over 1,000 new cryptocurrencies on the internet. By any measure, the creation of new money outside of the measured monetary base is inflationary. But e-money alone does not fix the debt problem. You need to move to blockchain for that. It is an entirely new ledger in which every single transaction is automatically recorded. In short, e-money and blockchain are the death knell of the black economy. Governments will be able to tax transactions at the exact moment they occur. While this will improve every government’s finances positively and permanently, it may also punish those at the bottom all over again.

The internet is clearly changing the value of money. In the past, the value of money was tied to gold. That’s because governments agreed that there should be some sort of proportional relationship between the volume of money and the value of gold they held in their reserves. The United States ended that policy in 1971 and many others followed. Ever since, the volume of money has been a function of the judgements made by economists at the Federal Reserve and other central banks. Naturally this has challenged the trust required for the public to place their faith in what are known as ‘fiat’ currencies such as the US dollar, the euro, sterling and so on. These are currencies declared to be legal tender, but not backed by a physical commodity. The value of fiat money is derived from the relationship between supply and demand rather than the value of the material that the money is made of. The fact that most governments have spent more than they have earned and now face record debt problems further undermines that faith and confidence. This increases the interest in shifting to the non-fiat e-money the internet facilitates.

A booming stock market

In addition to the stimulus of quantitative easing (QE), we now have the increased defence expenditure, the presidential tax cuts and the Belt Road Initiative (BRI). China is investing trillions of dollars into global infrastructure with the BRI, but that injection of capital is not necessarily picked up by traditional monetary aggregate measures. No one is adding up all the new BRI spending from Kazakhstan to Nicargua. In addition, Chinese wages are now consistently rising. Where once China was exporting deflation, it’s now exporting inflation.

The internet has broken down national borders to create a global financial ecosystem, but insular national governments still measure the economy at national boundaries. Consequently, in 2018, inflation is materializing and everyone is looking for safe haven. Investors are being pulled into stock markets as inflation and innovation pick up. Small interest rate hikes confirm that growth is real. Inflation, even at low levels, compels investors to get out of cash. Inflation erodes the value of cash. It makes investors disinclined to buy more bonds because inflation hurts bonds.

We know that the US and other central banks are not especially worried about rising inflation. The leaders at the Federal Reserve have intimated that we have been below the average inflation target for so long now that we should go above it for a while.

Meanwhile, we know that more money and faster money usually enable more leverage. In other words, more people can borrow against their collateral or take bets that are disproportionate to their actual capital. Could the internet be facilitating more leverage, more transactions and, therefore, more inflation?

What about underfunded pensions in a world where populations are ageing? Surely that is deflationary? Charles Goodhart, a greatly respected British economist, wrote a paper in which he argued that ageing populations may actually prove to be inflationary.38 After all, there will be fewer young people around, so they will naturally want to raise the price of their labour. Also, older people are re-entering the work force at a record rate. This is giving them more disposable income and causing them to spend more of that disposable income. Maybe an ageing population is inflationary, not deflationary?

It’s the same the whole world over/It’s the poor what gets the blame/It’s the rich what gets the pleasure/Ain’t it all a bloomin’ shame?39

Billy Bennett’s music-hall ditty from 1930 could have been written for these times. The biggest issue of all remains debt. Everyone everywhere feels the problem. At the national and international levels, policymakers have encouraged consumption and penalized saving. That has been the purpose of record low interest rates. No-one can be surprised that the level of personal debt has risen. Personal debt is approaching all-time highs. This is worrying given rising interest rates and inflation. It doesn’t take much imagination to see this is unsustainable. Neither are the consequences of personal economic failure difficult to see. Consumption has been encouraged by facilitating both consumer credit and spending. In Figure 2.5, we see the astronomic levels of personal debt, which echo those of the governments we saw earlier.