2 The Improviser’s Lazy Brain

Improvisation and cognition

Good actors are not always good improvisers and good improvisers are not always good actors. Although these skills overlap, there seem to be specific abilities and cognitive functions required for improvisational theatre. Improvisers have more freedom; they deal with countless options and constantly make choices while playing with other improvisers. So improvisation might be described as a process of decision-making. How do improvisers make these choices? How do they arrive at, and select, new options? How can they do this without hesitation, ‘thinking’ or the audience noticing? Is improvisation simply a process of quick decision-making? How does an improvising actor’s mind work? Can cognitive science help us understand improvisation? In this section, I will look at three approaches that might help explain how improvisers’ minds work.

The Specific Language of Improvisation

There are numerous ‘How to improvise’ books, and a specific language of improvisation has evolved within modern improvisational theatre over the last 40 years. Might the key concepts in this literature tell us something about the way improvisers think and communicate? This section reconstructs the specific language of improvisational actors, deducing certain higher-level patterns of thinking.

Improvisation as Problem Solving

In classical cognitive theories, improvisation can be seen as a process of solving the ‘problem of the scene,’ that is, proposing options and selecting ‘actions’ as solutions. This approach is more focused on the single actor than on the group. Viewing improvisation as problem solving should allow cognitive computing to simulate improvisation in digital agents. This section will outline a cognitive model and previous attempts to build improvising robots.

Beyond Problem Solving: Embodiment and Social Cognition

Psychoneurological studies, communication studies and theories of embodiment understand improvisation differently, focusing on group interaction more than on the single actor. In this section, I will examine the current state of research in embodied cognition, social cognition and its relevance for improvisation.

The specific language of improvisation

For over 40 years, the producers of modern improvisational theatre have been experimenting with concepts to describe what they are doing, to communicate with each other and to teach improvisation to students. The concepts in numerous ‘how to improvise’ books can mostly be traced back to two schools of improvisation: The British-Canadian school, represented by Keith Johnstone, and the Chicago school, based on Viola Spolin, Paul Sills, David Shephard and Del Close’s work. Keith Sawyer (Sawyer 2003) was the first to analyse improvisation’s evolving language and construct a ‘grass-root theory of discursive action,’ as well as an ethno-theory of improvisational theatre. His empirical base was the Chicago school’s language, an approach I followed in 2013, adding British-Canadian concepts and differentiating between rules and attitudes.

Rules

The grass-root level: turn after turn

On a very basic level, the process of improvising can be described as a sequence of turns, usually sequentially taken by the actors. Each turn consists of an offer and a response. The most important rule is that each prior offer is accepted. Great emphasis is placed on this rule by both schools (Salinsky and Frances-White 2008, 57). An offer can be accepted in many ways—either in the obvious content or in the subtext—which makes offer/response much more complex than it first appears. The Chicago school coined the term the ‘yes-and principle,’ highlighting that accepting an offer and adding new information, and thus creating a new offer, are always connected and depend on each other.

Example:

A: ‘Do you remember aunt Martha’s birthday?’

B: ‘Yes! And how she could not open the present!’

A: ‘Yes! And how you brought her the big knife!’

B: ‘Yes! And how her husband suddenly came in and thought you wanted to kill her?’

This principle guarantees that each player’s contribution is integrated into a chain of communication that builds up a fictional reality: ‘The whole point of the Yes And game is to build a chain of ideas, each linked to the previous one’ (Salinsky and Frances-White 2008, 59). ‘Yes’ is not always literal. If, for example, a murderer pointed a gun at a character stating that he wants to shoot her, it would not be adequate to say ‘Yes.’ On the contrary, it would be considered blocking because the offer is an invitation to play a game, not to end it. It also is inadequate to soberly accept an offer; it should be accepted emotionally, enthusiastically and meaningfully (Halpern, Close, and Johnson 1994, 45–56; Johnstone 1999, 101–29; Salinsky and Frances-White 2008, 94). The offer itself does not hold any meaning; the meaning emerges through the manner of acceptance. Highlighting this point, Johnstone coined the term ‘to overaccept’ (Johnstone 1999, 110).

Working together, turn after turn, prevents a single player from contributing too little or too much to a scene, which is important to balance the collaboration, as I will show presently. In theory, there are no ‘bad offers’; in practice, however, improvisers look for a certain quality in offers. Johnstone emphasises the importance of ‘blind offers’ (Johnstone 1987, 172), which are open to interpretation and provide a starting point for associations. Improvising actors discern four types of offers, depending on how much space they provide for interpretation (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Four kinds of offers

Blind offers |

Open offers |

Closed offers |

Controlling offers |

Open up the maximum possible interpretations |

Open up a broad spectrum of possible interpretations |

Open up a small spectrum of possible interpretations |

Open up the minimum of possible interpretations |

Example: Improviser putting forward his or her hand |

Example: Improviser putting forward his or her hand and saying: ‘I made this for you!’ |

Example: Improviser putting forward his or her hand and saying: ‘I made this wooden puppet for you!’ |

Example: Improviser putting forward his or her hand and saying: ‘I made this wooden puppet for you! You said you would give me 20 dollars for it.’ |

Most improvisers agree that controlling offers generally have a negative effect on improvisation: They do not free the stage partner’s creativity and take control of the situation. Blind offers, on the other hand, are generally valued, but can lead to an option-overload for the stage partner, if they are too vague. Long-form improvisation relies on the slow construction of a fictional reality, so blind and open offers are preferred. In short-form improvisation, the fictional reality builds quickly, so closed and controlling offers are acceptable. More terms have evolved around the concept of offers like ‘advancing,’ ‘extending,’ ‘heightening’ and ‘raising the stakes,’ to refer to different forms (Sawyer 2003, 94–5), indicating the importance of the concept.

Making offers and accepting them builds a collaborative relationship and responsiveness between the stage partners—but this process is highly unstable. Improvisers have therefore sought to identify forms of behaviour that hinder the collaborative process and have coined terms to describe them. Johnstone introduced the term ‘Blocking,’ which involves hindering the offer of your stage partner from affecting the scene, thus neutralising it. For Johnstone, the player not only blocks the story, but also the partner’s creativity, and possibly his or her own (Johnstone 1987, 127 ff; Johnstone 1999, 101–29). The Chicago School prefers the term ‘denial’ (Salinsky and Frances-White 2008, 57). A well-known example is found in ‘Truth in Comedy’: a couple is discussing their divorce. He says: ‘But honey, what about the children? She replies, ‘We don’t have any children!’ (Halpern, Close and Johnson 1994, 48). Different terms have evolved around the concept of blocking or denial, like cancelling, shelving and ignoring (Sawyer 2003, 96), indicating the importance of the concept.

Beyond the grass-roots level

There is common ground between the two schools of improvisational theatre at the grassroots level, but differences become apparent at higher levels of performance. While the British-Canadian school emphasises the importance of storytelling, the Chicago school focuses on the concept of the ‘game of the scene,’ described later.

Rules for storytelling

Johnstone claims that humans have a natural ability for narration that can be freed through training. When improvisers learn not to block, the story evolves, taking on a quasi-natural shape, often a circle or spiral. According to Johnstone, stories take shape by exploiting their beginning, so it is crucial to start with a routine, a ‘platform,’ as Johnstone calls it, that consists of all information shared among the players and with the audience; a good ‘platform’ contains a lot of specific information that the actors can reintroduce later.

A general rule is to ‘Start positive!’; it is considered a mistake to start a scene with interpersonal conflict. Improvisers talk of ‘Instant trouble’ (Johnstone 1999, 128), a very common mistake for beginners (and actors trained in scripted theatre), who tend to think that conflict is interesting and have to be trained to ‘just be average’ (Johnstone 1999, 64).

When moving through the story, prior elements get reincorporated and new moves are generated by following the ‘what comes next’ rule; every next move should inspire the players and audience. While following this, a story will emerge.

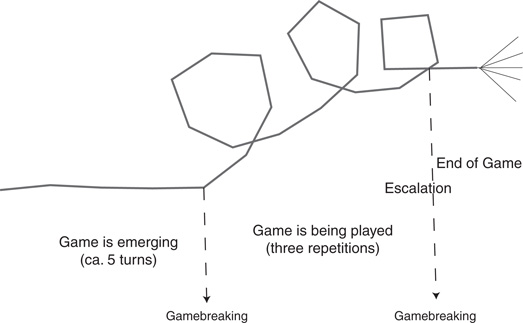

The game of the scene

The Chicago school places less emphasis on storytelling; its tradition rests on the concept of the ‘game of the scene.’ This is derived from Spolin, but has grown into a more sophisticated concept. In Spolin’s work, games have a clear setting and well-defined rules, while in the concurrent Chicago school, games emerge during the scene without a clear setting or rules; actors have no time to explicitly agree upon rules. Instead, they are taught to ‘Find the game’ (or ‘Listen to the game’), focusing on the ability to detect patterns and participate in an ongoing game. A game here means a sequence of interactions, in which the participants have interdependent objectives, usually in an antagonistic way; the closer A gets to his or her objective, the more distanced B will be towards his or her objective, and vice versa. For example, when two characters are both trying to gain a high status, they will inevitably have interdependent objectives and start a game. Any interaction can be turned into a game. It can take the shape of a conflict, but improvisers are taught not to rely on conflict too much in order to be open to any type of game that might emerge. Usually a game appears within the first five stage actions. It should not be constructed or forced upon the fellow players, but should emerge ‘by itself.’ Once found, the game can be heightened until a maximum is reached (usually three rounds, with every round taking things to an extreme). The scene ends when the game ends.

Attitudes

While at the grass-root level there are a lot of rules — only a few of which can be described here — there is a consensus among improvisers that attending to impro-rules will not necessarily generate a good scene. Mick Napier (2004) has made it his mission to remind the community of this fact because ‘How-to-improvise’ books regularly give a wrong impression. Advanced improvisers don’t cling to rules, but, like sportsmen or musicians, follow their embodied knowledge, which consists mostly of attitudes that foster good improvisation. As attitudes have to sink deep into the mind and body of an improviser, they often take the form of mantras. Though the wording varies, I list some of the most common attitudes in the following section.

‘Don’t tell jokes’

Improvisational theatre is often misunderstood as a form of comedy, because it tends to be funny, but all pioneers of this theatre agree that improvisers should not try to be funny or original (Halpern, Close, and Johnson 1994, 23–8; Johnstone 1999, 30–3, 125). Jokes usually destroy the most precious resource of improvisation, the players’ commitment to the team and the scene’s fictional reality. A joke always lets the teller shine, but destroys the story, the game and the stage partners’ motivation. An improviser who seeks a laugh loses his or her freedom and power to play, so improvisers are taught not to try to be funny and to ignore laughter.

‘Show, don’t tell!’

This rule dates back to Viola Spolin (Sawyer 2003, 109) but is a shared attitude in both schools. Physicalisation and emotion are valued more than just talking (Spolin 1977, 237–52). Emotions or ideas should be acted out spontaneously rather than be expressed verbally. Too much talking is considered a mistake and called ‘hedging’ (alternative: talking heads) (Johnstone 1999, 123). A similar error is ‘waffling’ (Sawyer 2003, 109), talking about things to do instead of doing them.

‘No playwriting’

Spolin used the term ‘playwriting’ for the mental activity of planning the scene ahead (Spolin 1977, 388). Johnstone would agree that planning ahead is not useful for improvisation. Usually when involved in pre-planning, improvisers will lose their attentiveness; they will cut off the ongoing exchange of clues between the players and miss out on important information (Sawyer 2003, 99). They will not be able to really listen to the stage partners or the game (Halpern, Close, and Johnson 1994, 70).

‘Don’t do your best’

This attitude is one of Johnstone’s most important lessons, which he seems to never tire of teaching to his students (Johnstone 1999, 64). If you try to do your best, you will inevitably fail in improvisation. Instead, you should feel safe and confident on stage, not expect too much and not punish yourself for being average. The Chicago school emphasises a similar concept of self-forgetting, flow and freedom from fear. I will return to this important attitude in Section ‘Beyond Problem Solving: Embodiment and Social Cognition,’ because it is potentially key to understanding underlying brain-functions.

‘Do not fear mistakes – there are none’ (Miles Davis)

This attitude originated in jazz; the concept was imported into improvisational theatre by the Chicago school: ‘There is no such thing as a mistake’ (Halpern, Close, and Johnson 1994, 79). Not only will an improviser who tries to avoid mistakes get fearful and block his or her creativity, but improvisational theatre in general has flourished in objection to, and rejection of, most principles of theatre aesthetics; it had to reject scripted theatre’s claims of perfection and artistic virtuosity, in order to develop its own criteria and a ‘poiesis of imperfection’ (‘Poiesis des Imperfekten’ (Bormann, Brandstetter, and Matzke 2010, 193)). In part, this references oral cultures that embraced improvisation. Jonathan Fox, founder of the playback theatre movement, writes:

Failure is inadmissible in a literary-technological society, but in oral culture – in the world of improvisation, of putting together in the crucible of the moment – the tangible possibility of failure is what makes success possible. Failure is not the poison but the spice of oral composition.

(Fox 1994, 96)

The poiesis of imperfection, rooted in oral cultures, is also a very modern trait, with connections to early twentieth-century avant-garde movements in Europe (Lösel 2013, 53 ff ).

‘Give up your self’

Both schools describe the ideal of self-forgetting, or at least reduced self-consciousness, and the idea of conscious authorship is criticised as not useful for improvisation. For Spolin, one of the main goals was to free the actor from the tendency to ‘perform’:

A moment of grandeur comes to everyone when they act out their humanness without need for acceptance, exhibitionism, or applause.

(Spolin 1977, 44)

Spolin describes an ideal state of self-forgetting in spontaneity, which can be reached through attention to a ‘Point of Concentration’ and complete commitment to the game. In her later work, she further emphasises this in the rule ‘Follow the Follower.’ In this, the improvisers are taught never to make an active offer, but to follow the previous offer. This leads to emerging group-creativity and a trance-like state, in which the improvisers will not conceive of themselves as authors of the work. Similarly, Johnstone saw attempts at originality as a problem of improvisation (Johnstone 1999, 124). He discusses this problem at length, summarising his belief that people who try to be original always come up with the same old boring answers. Improvisers should act as if they are controlled by an outer force: ‘Great improvisers “go with the flow” accepting that they’re in the hands of God, or the Great Moose’ (Johnstone 1999, 341).

Other evidence for the ideal of self-forgetting is the existence of ‘Footing-Games’ (Sawyer 2003, 29). Sawyer introduced this term to describe a category of games that cover up agency. Two players merge into one person, speaking with one voice, dubbing each other, miming the other’s hands and so forth. Neither the actors nor the audience can detect who is the author of this scene or responsible for its content.

‘Take risks’

Improvisers must be able to make unpredictable moves, produce crazy ideas and surprise their fellow players and even themselves. Johnstone emphasises the use of material that might seem obscene and even psychotic. One of his important ideas is the concept of tilts – surprising actions or lines that reframe the fiction of the scene (like a player saying: ‘I died last year in a car accident.’). In the Chicago school, Close devised the rule ‘Always take the active choice’ (Johnson 2008, 53), meaning that an improviser should always choose the option that maximises change on stage. These attitudes are in contradiction to the instruction to ‘be obvious’ and stay inside the ‘circle of expectations.’

Conclusion

While attitudes and their wording vary between countries and schools, they have one thing in common: They take on very simple, repeatable forms, so they can become ‘second nature’ for the players. Like sportsmen, improvisers have no time to consciously think about options and rules while they are performing, but must rely on embodied knowledge available often after years of training. The ten Impro Commandments, probably dating to the 1980s in Australia, are an example of this sacred simplicity:

Thou shalt not block.

Thou shalt always retain focus.

Thou shalt not shine above thy team-mates.

To gag is to commit a sin that will be paid for.

Thou shalt always be changed by what is said to you.

Thou shalt not waffle.

When in doubt, break the routine.

To wimp is to show thy true self.

S/he that tries to be clever, is not; while s/he that is clever, doesn’t try.

When thy faith is low, thy spirit weak, thy good fortune strained, and thy team losing, be comforted and smile, because it just doesn’t matter.

(Charles 2003, 247)

Game building and game breaking

As noted before, some rules of improvisation contradict others. This is not just a side phenomenon but pertains to some of the basic instructions. To understand this, I suggest distinguishing between two phases of improvisation: a phase of game building and a phase of game breaking. In game building, players will act in collaboration, attend to the rules (especially the ‘yes-and principle’) and slowly build up a fictional reality. In game breaking, an individual improviser will break the rules, act in unpredictable, anarchistic ways and destroy the emerging patterns of the improvisation. The criteria for a good choice thus depend on the improvisation phase. In a game-building phase, an option is good when it is obvious and adds to shared mental models of the scenic reality. In a game-breaking phase, an option is good when it is divergent, unexpected and leads to much stage action. The improviser should develop a sharp sense of when game building or game breaking is needed (Lösel 2013, 311).

Embodiment of rules and attitudes

The role of domain knowledge in improvisation has long been discussed, beginning with Jeff Pressing’s early work ‘Cognitive processes in improvisation’ (Pressing 1984). As described earlier, the rules and attitudes have to become ‘second nature’ through a training that resembles training for team sports. While there is a specific language to analyse problems post performance, the improviser on stage draws from embodied knowledge peri-performance. As Berkowitz points out:

Once installed in memory, however, the elements of the knowledge base must be organized and refined – ‘enriched’ in Pressing’s words.

(Berkowitz 2010, 40)

It takes years for an improviser to learn to become relaxed and skilful at the same time, to not give his or her best and to let his or her brain work without interfering too much.

Improvisation as problem solving

Classical cognitive theories conceive of cognition as problem solving, and it is certainly worth looking at improvisation through this conceptual lens. The specific language and concepts of improvisation can be thought of as a toolbox for problems that arise.

Brian Magerko et al. (2009) conducted a study of improvising actors by conceptualising improvisation as a process of problem solving. Using video-cued-recall, they explored what improvisers conceive as the ‘problem of a scene,’ and what they do to solve it: Experienced improvisers were video-recorded while improvising in a laboratory situation. After the performances, the participants were shown their scenes and asked to comment on their thoughts at specific points in the performance. This method has limitations; it can only uncover what the improvisers consciously experience and what they can verbalise. Nevertheless, it is probably the best current method of ‘looking inside improvisers’ heads.’ So, Magerko et al. gathered verbal reports on cognition in improvised scenes. One result shows that improvisers do use their specific language to describe and explain the problems of improvisation.

Modelling improvisation

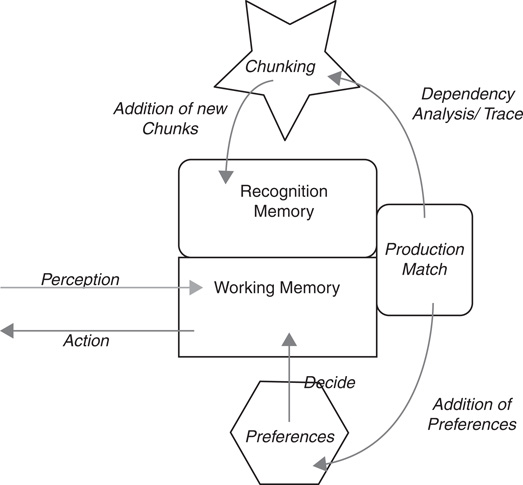

In a second step, Magerko et al. suggested that improvisation can be modelled using a well-established cognition model – the decision circle from Newell’s Unified Theory of Cognition. This model is connected to a computational model called SOAR (State, Operator and Result), and can therefore be directly codified (Figure 2.1).

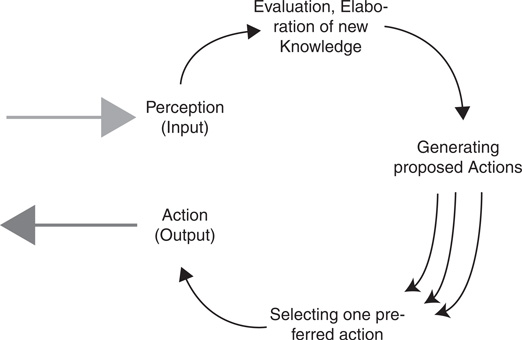

SOAR is an input/output concept, with perception as input and action as output. Between input and output, working memory, recognition memory and production-match work together closely to generate two learning circles, of which one is designated to proposing options. If none of the stored options fit, the problem and strategies have to be broken down into smaller pieces—subgoals—until new options can be generated. The other feedback loop serves as decision-maker, using past experiences from an episodic memory continually supplying preferences and updated with every new experience. SOAR uses production rules to generate states that gradually bring the system closer to the goal state. The main link to the outside world is the Working Memory, which controls the input (perception) and the output (action), completing and evaluating the input and selecting the most promising action. SOAR follows Allan Newell’s decision circle, which states that, whenever reasonable, cognitive acts can be separated into five steps:

receiving input

the elaboration of new knowledge based on other knowledge or inputs

the proposal of new operators/actions/goals to pursue

the selection of one of the proposed courses of action

the execution of the selected action (Figure 2.2)

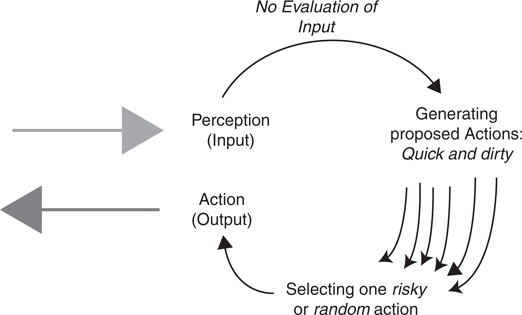

While Magerko et al. assume that this decision circle applies to improvisation in the same way it does to other cognitive actions, there are major differences: (1) improvisers are trained not to evaluate the input, but to greet every impulse with joy and acceptance; they skip the process of input evaluation. (2) The production of options is maximised. Improvisers follow a brainstorming technique, generating many of the options as quickly as possible; they produce ‘quick-and-dirty’ options. (3) The decision about which option should be selected also works without evaluation. Improvisers are trained to take any choice without worrying. So, to a certain extent, it appears as ‘selection by chance.’ The decision cycle in improvisation might be visualised as shown in the figure (Figure 2.3):

Compared to everyday life decision-making, improvisation decision-making seems to follow a reduced and simplified form of the decision cycle, omitting the evaluation of both input and output. The ‘normal’ circle of decisions is not the rule in improvisation, and it seems possible to propose an improvisational mode of cognition, which applies when normal problem-solving strategies have failed and/or when there is time-pressure and/or no real problem at all, as in a playing situation.

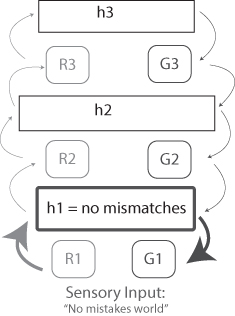

Improvisation, anticipation, prediction

Yoshiro Endo (Endo 2008) worked out a computational framework for improvising robots, assuming that improvisation is a kind of emergency mode for the system in order to be able to react when anticipation fails. He constructed a system that does not rely on episodic memory but on a transcoded form of memory derived from Antonio Damasio’s concept of ‘somatic markers’ (Damasio 1996): Instead of searching for specific memories, the system will search for more abstract markers like emotions, vectors and intuitions. It also includes sensory data from the robot’s ‘body.’ This model is in accord with the more recent approach of predictive processing (Clark 2016), suggesting that the brain works as an automatic prediction machine on multiple levels. Only when prediction fails on one level will the next (higher) level spring into action, recoding the input in an attempt to make better predictions.

What does this mean for improvisation? At the beginning of a scene, when every option is possible and predictability is very low, the improviser’s brain has to deal with high prediction error. Andy Clark describes a similar situation to illustrate the start of predictive processing under very special conditions:

Imagine you are kidnapped, blindfold, and taken to some unknown location. As the blindfolds are removed, your brain’s first attempts at predicting the scene will surely fail. But rapidly processed, low special frequency cues soon get the predictive brain into the right general ballpark. Framed by these early emerging gist elements […] subsequent processing can be guided by specific mismatches with early attempts to fill in the details of the scene. These allow the system to progressively tune its top-down predictions, until it settles on a coherent overall interpretation pinning down detail at many scales of space and time.

(Clark 2016, 42)

Quite similarly, the improviser’s brain will start generating quick and uncertain guesses about the environment, starting from gist elements, on a very general level, and slowly filling in the details. There is one crucial difference to a real situation though: no ‘true’ information exists to validate the guesses. Instead, every suggestion will be accepted by fellow players and become part of the fictional reality of the scene. So there is no resistance by the outside world to the proposals of the inside world, or, as I call it, improvisation creates a ‘no mistakes world.’ Improvisation here exceeds a simple input/output model of cognition, instead generating a very special environment that triggers automatic prediction processes, but avoids mismatches. Presumably this will lead to a processing mode that does not involve higher levels of processing, because those would only spring into action when a mismatch occurs (Figure 2.4).

Having no ‘resistance’ of real-world data, predictive processing will presumably lead to a fast mode of processing that excludes higher levels of processing, involving a high degree of automatisation, which may account for the trancelike state, improvisers often report (Scheiffele 1995; Lösel 2013). This model suggests the minor importance of domain knowledge (like the rules and attitudes) in the process of improvising as they would presumably be stored in higher levels of the cognitive system. Instead, the interaction with the very specific environment of improvisation would be processed mainly on a very basic level, with high speed and an increasing confidence in the ‘no mistakes world.’ This is what I refer to as a ‘lazy brain.’

Chance, selection and emergence

Johnson-Laird, a cognitive scientist and jazz musician, was one of the first to apply cognitive concepts to improvisation (Johnson-Laird 1989). According to him, only three types of algorithms truly facilitate improvisation: neo-Darwinian, neo-Lamarckian and a hybrid of the two. Both Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Charles Darwin developed a theory of evolution in the nineteenth century. While Darwin proposed mutation and selection as the only mechanisms for evolution, Lamarck doubted that species evolved in such a trial and error way. Instead, he suggested the inheritance of acquired characteristics as a motor of evolution. A neo-Darwinian algorithm generates a new piece by randomly blending different pieces together, generating a large number of options and leaving selection to the environment. In the case of collective improvisation, the environment consists of the other improvisers and their choices. If they pick up an idea it will evolve; otherwise it disappears. In a neo-Lamarckian algorithm, a new piece is derived from relevant domain knowledge, leading to more elaborated improvised outcomes that hardly require selection. Johnson-Laird notes that even though the neo-Darwinian approach, because of the randomness of the production process, is fated to produce a substantial amount of unwanted pieces, it is the only way to improvise when no expert knowledge is available. On the other hand, the neo-Lamarckian approach might be doomed to stay inside the frame of the already known, since it heavily draws on expert knowledge. Both approaches seem to be compatible though: Shimon, an improvising robot musician, incorporates both neo-Lamarckian and neo-Darwinian aspects (Hoffman and Weinberg 2011).

Conclusion

Starting from classical models of cognitive science, there are interesting conclusions to be drawn: (1) rather than embedding improvisation into ‘normal’ processes of cognition, improvisation seems to call for a separate mode of cognition. (2) The improvisational mode seems to be called for when anticipation fails or is suppressed. (3) The improvisational mode of cognition either produces numerous options (neo-Darwinian) or one specific option (neo-Lamarckian). (4) The improvisational mode must enable proactive behaviour, even though there is insufficient information to build anticipations, so it will presumably make extensive use of predictive processing. (5) The improvisational mode is a ‘lazy’ way of processing, since it omits exhaustive procedures of comparing the current situation to experience and evaluating options.

The improvisational mode probably uses less neural capacity than everyday problem solving, with a faster, but less precise outcome. Clayton Drinko explored cognition and improvisation in 2013, and he suggests that the improvisational mode might rely on the same structures as Kahnemann’s system 1 (Drinko 2013). Kahnemann, exploring economic decision-making, identifies two systems: System 1 makes fast choices, relying on heuristics. It can complete a sentence someone else has started, know when someone is angry before they speak, understand simple phrases, drive, read simple words or react when something is disgusting. System 2, on the other hand, relies on a slow mode of cognition. It is responsible for the continuous monitoring of one’s behaviour, building an internal monologue, and is the conscious problem solver (Kahnemann 2011). If the improvisational mode of cognition is identical with Kahnemann’s system 1, this explains why improvisers put so much emphasis on staying in a state of effortlessness and ease while improvising. When they fail to reach this state, System 2 springs into action and a completely different way of processing starts. This accords with Johnstone’s mantra to never give your best and with the general emphasis on reducing stress and fear of failure. The ideal of effortlessness thus appears to have a neurological basis; to improvise, the brain has to be in a laid-back state. It has to be lazy.

Beyond problem solving: embodiment and social cognition

Psychoneurological research hints towards an understanding beyond problem solving. Charles Limb, a jazz-musician and researcher, conducted several functional Magnetic Resonator Imaging (fMRI) studies to detect areas of the brain that increase or decrease activity during improvisation (Limb and Braun 2008, Donnay et al. 2014). He constructed devices to make improvisation and musical interplay possible under fMRI’s restricted conditions. His findings indicate: (1) a decrease in activity in the lateral prefrontal cortex, an area associated with self-monitoring and self-control, (2) an increase of activity in the medial prefrontal cortex, an area ascribed to creativity and connected to the limbic system, which processes emotions and (3) a close connection to Broca’s area, which is crucial in producing language and gesture. These results fit the theories of improvisation. Actors are trained to minimise self-control, activate areas of spontaneity and creativity and to be in a close dialogue with their fellow improvisers. Drinko emphasises links between language and gesture as key concepts for acting, arguing that all forms of communication—music, language or acting—might share the same neurological basis, referencing the ‘shared syntactic integration resource hypothesis’ (Patel 2008). These findings suggest that improvisation should be more aptly framed as communication instead of being reduced to problem solving.

Bodies in sync and an altered state of mind (ASM)

The idea of synchronised movement and a hidden link between the bodies (and minds) of improvisers is shared among improvisational actors and strongly emphasised by all pioneers of modern improvisational theatre, from Jacob Moreno to Viola Spolin and Keith Johnstone. The Chicago school refers to the Group Mind, which is a similar concept. Synchronisation or entrainment becomes obvious in mirror games—where improvisers strive for synchronised movement – and in ‘follow the follower’ games, as well as in Johnstone’s concept of status. Bodies are trained to be responsive to each other, without higher cognitive functions interfering, often resulting in a trancelike state of mind. Synchronisation of movements also links to experimental approaches in cognitive psychology and behavioural sciences. Using an advanced method, Walton et al. studied the synchronisation of movement in the bodies of improvising musicians (Walton et al. 2015), identifying certain parts of the body that tend to sync more closely than others, especially heads and hips. Research is also being undertaken on brain synchronisation during improvisation. Early results indicate that brains probably synchronise at lower frequencies (e.g., delta and theta waves) (Müller, Sänger, and Lindenberger 2013), but the results are not consistent. Synchronisation appears to foster a positive relationship, while de-synchronisation tends to destroy it. Thus, mirroring helps create a collaborative mode.

An altered state of mind (ASM)

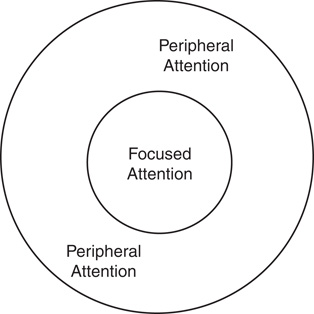

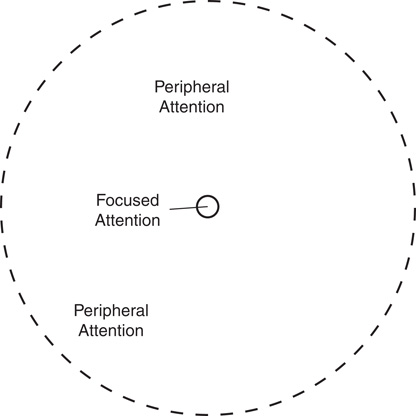

In improvisation, body, mind and environment are connected in specific ways that differ from everyday consciousness. There is some evidence that the improvisational mode of cognition is a form of trance, or altered state of mind. Eberhard Scheiffele, a psychologist, explored improvisation as an altered state of mind, finding that most criteria of hypnosis and trance fit to mind-states in improvised acting (Scheiffele 2001). Clayton Drinko explored the closeness of improvisation to trance and to alcohol intoxication, suggesting that similar neurological structures are involved (Drinko 2013). There are other works linking improvisation with the concept of flow (cf. Kießling 2011). Johnstone also establishes trance as a key concept of improvisational acting, especially in his mask work. Trance phenomena have specific effects on cognitive functions like attention and memory, as Drinko points out, and while there is not yet a brain study to prove ASM during improvisation, improvisers’ subjective accounts support this hypothesis. Improvisers often do not remember exactly what they did on stage, just as trance media usually have no memory of what they did during trance. In another similarity to trance, improvisation calls for a paradoxical form of attention. On one side it needs to be extremely focused. Spolin used the term ‘point of concentration (POC),’ reminding her students to ‘keep your eyes on the ball,’ creating narrowed attention (Spolin 1977, 21, 28). Johnstone creates a similar effect using masks through which the actor can see only a very small part of the environment. So, just as a medium in trance is asked to focus on a monotonous object like a clock, the improviser’s attention is also narrowed. Paradoxically, openness to environmental information is simultaneously extremely high, so a double-attention is generated that is typical for trance (Figures 2.5 and 2.6).

Improvisation as communication and collaboration

Improvisers enter a specific state of connectedness with their environment. In what follows I describe two concepts of improvisation as interaction or communication: Keith Sawyer’s concept of the interactional frame and my own concept, in the tradition of Niklas Luhmann’s systems theory.

Social emergence

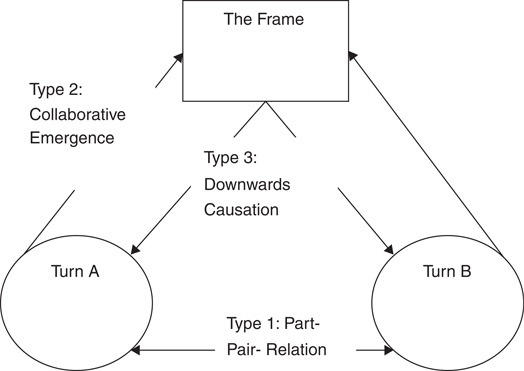

Sawyer’s (2003) work on improvisation applies the concepts of communication science, in the tradition of George Bateson and Irving Goffmann, to improvised dialogues, building a theory of social emergence in improvisation. His model integrates bottom-up and top-down approaches, introducing two levels (Figure 2.7):

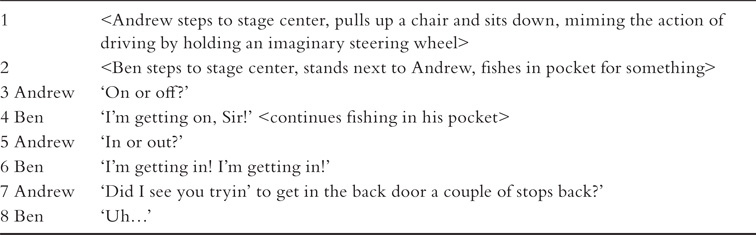

At the lower level, actors exchange pieces of dialogue (Type 1 relation: Part-to-Pair Relation), which lead to the emergence of an interactional frame on the higher level of the system (Type 2 relation: Collaborative Emergence). The interactional frame will then be the frame for new interactions on the lower level, facilitating certain moves and making others improbable (Type 3 relation: Downward Causation). Sawyer suggests understanding improvised interactions as complex systems, meaning these causal relationships are not deterministic. The pair-to-pair interaction cannot predict the emergence of the interactional frame, the frame does not determine the following interactions and so on. Unpredictability is introduced into the model, while still allowing causal relationships to be assumed. Sawyer underpins his model with elaborated analyses of improvised dialogues to explore the interactional frame’s emergence. Table 2.2 shows one example.

The dialogue is segmented into separate turns and the interactional frame becomes increasingly specific; every turn leads to a changed interactional frame. It is important to note that a turn (or offer) not only provides information, but also retains information to keep the space of possibilities open. Improvisers do not give the information directly, but are trained not to deliver too much information and wait for the frame to emerge ‘by itself’ through interaction. Sawyer provides much evidence for social emergence as a key concept for improvisation, claiming that the specific language of improvisational acting sets up perfect conditions for social emergence. Unpredictability emerges through interaction, not through the improvisers’ wittiness, an assertion in sync with the concepts of both schools mentioned earlier.

Table 2.2 The beginning of a two-minute scene at the Improv Institute

Niclas Luhmann and the concept of connectability

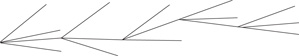

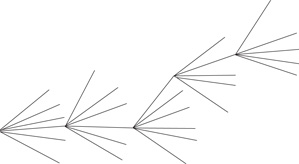

While Sawyer provides a model for improvised dialogues in general, he does not explain the difference between everyday interaction versus stage improvisation. A model derived from Niklas Luhmann’s operative system theory might fill this gap. The term ‘operative’ emphasises that the focus of this concept is not so much on the elements of the system, but on the operations within the system. A key concept is connectability: an operation only adds to the system when it can connect to a prior operation and when it provides possibilities for future operations to connect. Thus, Luhmann’s systems comprise chains of operations and cease to exist when there are no more operations that follow. This chimes with the improvisers’ view that they are dealing with operations (= offers) and their connectability (= yes and) all the time. Luhmann’s theory can also integrate Newmann’s circle of decision by modelling operations before one of them is selected. The following diagram visualises a chain of operations, which I call the ‘fir branch model of improvisation’ (Figure 2.8).

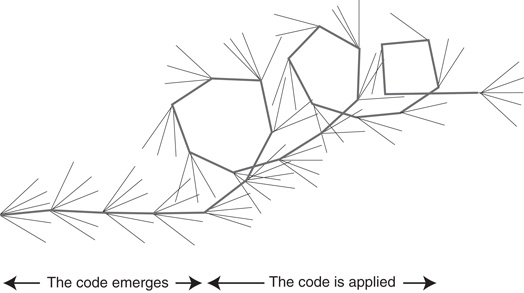

Each operation provides a couple of options to build upon. The following contributor selects one, adds an operation and provides more options to build on. For the system to be sustained, it is crucial to generate both operations that possess connectability and a code that allows operations to connect to each other. The code enables the selection of certain operations. In improvisation, connectability is maximised by preferring open offers and by applying the yes-and principle (Figure 2.9):

At each turn of the chain of interactions, the improvisation can be described as a process of decision-making in response to a spectrum of options opened up by the prior operation. This spectrum is much wider than everyday communication, leading to more choice. The rules of improvisation guarantee connectability; every offer has to be accepted. Where improbable and inadequate options would be rejected in the everyday system, in improvisation they are included and the probability of their selection rises. In this way, improvised interaction becomes more robust than interaction in everyday life because someone will always find a connection. This is why improvisation can assimilate a lot of ‘crazy’ choices without stopping; it allows for spontaneity, which might kill a normal conversation. Such a system is likely to become complex and produce emergent phenomena.

Improvisers strive to build larger components, like a fictional reality, dramatic interaction and/or a story. Since there is no plan, the shape and structure of the improvisation emerges through the application of a code that is implicitly agreed upon, usually after 5–10 turns. After that, the selection of options will follow this code. So, while the improvisation is progressing, the usage of prior knowledge gets more important, and the improvisation changes from a neo-Darwinian to a neo-Lamarckian mode (Figure 2.10).

The code, which in Sawyer’s terms would correspond to the interactional frame, specifies what types of operations are selected and thus connected to a following operation, while the others die off. In this way, a selection is possible that will shape the system/improvisation. The code could be Del Close’s instruction to ‘Always take the active choice,’ for example. Every selection by every player follows this code, and the improvisation becomes increasingly risky. The code could also be ‘Always take the most emotional option’ or ‘Always take the most insulting option.’ In other words, the code is the emerging rule of the game and performance will form into self-similar shapes (in the visualisation, they take the shape of a spiral) (Figure 2.11).

The code stays valid until a dramatic peak is reached; usually three repetitions please both audience and players. After this, the system, or game, ends (not necessarily the improvisation because it might comprise several or even many games). In the course of the improvisation, improvisers must listen carefully to the new code and break the game twice; after the ‘platform’ is established, and after the game plays out. The timing of these two points of game-breaking seems crucial for successful improvisation. In the field of dance, João Fiadeiro (Fiadeiro 2016) developed similar models within the research project Blackbox Cognition & Art (Fernandes 2014), indicating that some features of improvisation might be considered universal. The importance of these rather abstract models is that they break down the process of improvisation into single turns that can be described as individual decisions, while still allowing the improvisation to be viewed as a collaborative enterprise involving the improvisers’ bodies and minds. Cognitive science can help develop and test abstract models of improvisation.

Conclusion

The specific language of improvised acting consists of rules and attitudes that help improvisers communicate and shape their cognitions while improvising. When analysing scenes and teaching improvisation, they refer to their explicit concepts, describing improvisation as a form of problem solving. There is some evidence, however, that while improvising on stage, they have only minimal access to self-reflective parts of the brain and to explicit domain knowledge. Rules and attitudes therefore have to become embodied knowledge to allow for responsiveness ‘without thinking,’ that is without reflective thought. Predictive processing seems to be a promising concept to describe and explain the way the individual actor is connecting with his or her fellow player by predicting their actions on a very basic level. Presumably their training enables them to deal with a very high degree of prediction error without interrupting the interaction. This mode is quite different from that used for everyday problem solving and could possibly be described as an altered state of mind. While the individual improviser learns to enter this altered state of mind, improvisation is also a collaborative enterprise, building mutual understanding and anticipation. Borders of the self are no longer maintained and, in this state, social emergence can occur spontaneously. The rules and attitudes of improvisation not only generate a specific mindset for the single improviser, but also a collaborative environment that allows the improviser to switch on his or her ‘lazy brain’ without danger.