21 Relishing Performance

Rasa as participatory sense-making

‘There is no drama without rasa’ according to The Nātyashāstra (The Science of Drama), the Sanskrit aesthetic treatise attributed to Bharata (1996, 54). Rasa has been variously translated as juice, flavour, taste, extract and essence; it is the ‘aesthetic flavour or sentiment’ savoured in and through performance. Bharata tells us that when foods and spices are mixed together in different ways, they create different flavours; similarly, the mixing of different emotions and feelings arising from different situations, when expressed through the performer, gives rise to an experience or ‘taste’ in the partaker, which is rasa (55). Rasa is what is ‘tasted’ when a performance is ‘digested’ or ‘taken in’ by a partaker. The goal of Sanskrit drama was to create rasa, and rasa remains central to genres such as kutiyattam (a particular way of performing Sanskrit drama in Kerala, South India) and kathakali (a genre of classical dance-drama in Kerala). Rasa exists only as and when it is experienced: ‘the existence of rasa and the experience of rasa are identical’ (qtd Deutsch 1981, 215). Similarly, rasa exists always and only as the result of an interaction between performer and partaker. For Abhinavagupta (ce 950–1025), who commented extensively on The Nātyashāstra, rasa is not a gift bestowed upon a passive spectator or a commodity bought by a consumer, but an attainment, an accomplishment; someone who wants to experience rasa has to be an active participant – or, to use the dining metaphor, partaker – in the work.

Because Bharata has taken his metaphor from food, I refer to the spectator or audience member as a partaker: someone who has to choose to take in a performance, who has to actively put it in the ‘mouth,’ chew on it, break it down and roll it around on the ‘tongue’ to relish it; who has to ‘ingest’ and ‘digest’ the performance, incorporating it into the self. Rasa is active, participatory, interactive, social, experiential, sensual, tactile, multi-sensory, internal, emotional, intellectual, embodied and an attainment. Abhinavagupta refers to rasa as an ‘act of relishing’ (Deshpande 1989, 85 emphasis mine), and as such, rasa is both a noun and a verb: the relishing of the flavour and the flavour that is itself relished.

While the dining metaphor is useful for a first pass at understanding rasa, it eventually breaks down because experiencing and processing a performance is not, at the cognitive level, the same as eating a meal. Ultimately, rasa is a theory of embodied response to a performance – a theory of partakership – that can be understood in light of cognitive science. I will put rasa in conversation with Giovanna Colombetti’s discussion of embodied, experiential, participatory sense-making in The Feeling Body to position rasa as an ‘affective dimension of intersubjectivity, construed as an embodied or jointly enacted practice’ (Colombetti 2017, 172) of participatory sense-making.

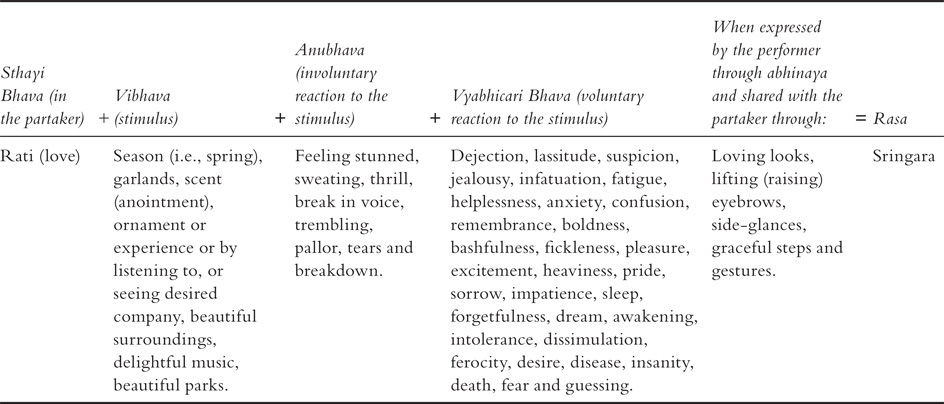

According to Bharata, ‘rasa is the cumulative result of vibhāva [a stimulus], anubhāva [an involuntary reaction to the stimulus], and vyabhicāri bhāva [a voluntary reaction to the stimulus]’ (1996, 55). Bharata lists eight rasas, each of which has varying degrees of intensity: shringāra (love, affection), hasya (joy, laughter, happiness), raudra (anger, rage), karuna (sadness, grief, depression), vira (strength, heroism), adbhuta (wonder, awe), bibhatsa (disgust) and bhayanaka (fear).

To examine how rasa works according to Bharata, let us focus on shringāra. Shringāra has been translated into English as ‘love,’ but in Bharata’s description, shringāra encompasses much more:

In our daily life whatever is pure, holy, resplendent is referred to as shringāra […] Moreover, a person enjoying happiness, achieving his desires and helped by proper season, flowers, etc. when he is in a woman’s company – that is called […] This shringāra results in the case of men and women, of healthy youth. It is of two kinds: sambhoga (fulfillment), vipralambha (non-fulfillment; lit. separation).

(Bharata 1996, 56, 57)

Shringāra that is fulfilled can be stimulated by ‘season (i.e., spring), garlands, scent (anointment), ornament or experience or by listening to, or seeing desired company, beautiful surroundings, delightful music, [and/or] beautiful parks’ (57). Clearly, shringāra can exist in the everyday world as well as on stage, and can be stimulated by many things, so rasa encompasses emotional experience in everyday life and on the stage.

Each rasa is built on a ‘sthāyi bhāva,’ or underlying emotional state. Shringāra is based on love; hasya is based on humour; karuna is based on compassion; raudra is based on horror; vira is based on the heroic; bhayanaka is based on fear; bibhatsa is based on repulsion; adbhuta is based on wonder. As Vinay Dharwadker points out:

The Nātyashāstra’s boldest implication is that the sthāyi bhāvas comprise an individual subject’s fundamental mode of existence in the world – that a self exists only in one or another of these long-lasting states at any given time, persists over time in a succession of such states, and has no other mode of existence.

(2015, 1384)

Shringāra is built on the sthāyi bhāva rati (love). For shringāra an underlying emotional state is subjected to a stimulus which, in the case of shringāra, might be a smell, a memory, a trip to the park, an interesting conversation, or an interaction with a loved one. This stimulus (vibhāva) would then mix with the sthāyi bhāva to create anubhāva – an involuntary or non-conscious psychophysical reaction to the stimulus, such as ‘sweating, thrill, break in voice, trembling, pallor, tears and breakdown’ (Bharata 1996, 57). The stimulus and the sthāyi bhāva also create vyabhicari bhāva, a more conscious and somewhat controllable reaction to the stimulus, which might include impatience, bashfulness, excitement, dissimulation or jealousy.

The Nātyashāstra’s main goal is to help performers evoke rasa; most of its chapters focus on how to create and present facial expressions, hand gestures and bodily postures that will embody the outward manifestation of an emotion so it can be shared with, and evoke a response in, the partaker. Bharata says that shringāra ‘must be expressed […] by loving looks, lifting (raising) eyebrows, side-glances, graceful steps and gestures, which are all anubhāvas or involuntary (natural)’ (Bharata 1996, 57). Rasa occurs when the sthāyi bhāva of the partaker is subjected to the vibhāva of the situation, and the anubhāva and vyabhicari bhāva of the character as performed by the performer, and shared with the partaker through abhinaya, the Sanskrit term for acting. Abhinaya1 literally means ‘to carry forward,’ and the actor is known as a ‘katha patram,’ or vessel for the story and its thematic and emotional content. The actor’s primary responsibility, which is built into the terminology, is to be a vessel to carry forward the character-story- situation in order to evoke a rasic exchange with the partaker (Table 21.1). To put it mathematically: sthāyi bhāva + vibhāva + anubhāva + vyabhicari bhāva + abhinaya (4 aspects) = rasa

Table 21.1 How the rasa shringāra is generated

Colombetti articulates a theory of embodied sense-making that parallels Bharata’s articulation of rasa. She argues that skills such as imitation, along with a responsiveness to others’ facial expressions and physical gestures, ‘embody […] a pragmatic form of understanding others’ (172) that is not based on internal simulation or mentalising, but constitutes an embodied practice. She refers to this as ‘participatory sense making, which is enacted in the concrete interaction between two or more autonomous agents coupled via reciprocity and coordination’ (172). These skills, present in daily life and in partakers of performance, create rasa – an emotional taste – through pragmatic, participatory and embodied sense-making in the coordinated and reciprocal interaction between performer and partaker.

An understanding between self and other involves empathy, which is, in Colombetti’s view, ‘an experiential access to the other’s subjectivity,’ a ‘feeling in’ (174). She stresses the ‘sensual nature of our experience of others,’ and refers to empathy as a process of sensing-in (174). For example,

I do not experience the other’s bodily sensation [as my own]. Hence when I see a hand tensely contracted in a fist, I do not experience this tenseness in my own hand, as if my hand were itself tensely contracted in a fist. At the same time, however, I do not just see the other’s hand and judge that it is tense [or mentalize about its tenseness]; rather, I experience the tenseness in the other’s hand.

(174)

Crucially, for a discussion of rasa as partakership, this direct body-to-body empathy occurs in the relationship between self and other: ‘I neither “lose myself” in the others nor incorporate the others’ experience into mine in a sort of extended awareness of myself’ (181). Empathy, then, is not self-referential: I do not convert the other person’s experience into my own in order to understand it (e.g., ‘I feel your pain’). ‘Rather, I retain an awareness of myself and the others as distinct subjects. At the same time, however, I am also aware, via basic empathy, that the others’ feeling is the same as mine’ (181). Colombetti’s analysis of empathy functions as a description of rasa as sensual and experiential, as a relationship between performer and partaker and as a process of sensing-in. This opens up an understanding of rasa as a practice of empathy in performance.

Colombetti points out that ‘one need not be able to name the emotion that one empathizes in the expression – even though, arguably, one’s emotional vocabulary can affect how one perceives expression’ (177). In other words, this connection is often, even usually, ‘prereflective’ (181). Colombetti also points out that there can be a ‘mismatch between the feeling that is empathized and the one that the observed person actually experiences’ (177). For example, an actor portraying anger may evoke fear; an actor portraying fear may evoke pity. Nonetheless, the partaker experiences the performer ‘as a source of feeling’ (181).

If rasa is a way of experiencing another’s emotions through the embodied relationship between self and other, if rasa is an affective dimension of intersubjectivity, it is an act of empathy, a practice of empathy and an empathetic response. Colombetti argues that the awareness of sharing a feeling (which is different from empathy) leads to a ‘higher unity’ between self and other (181). Rasa, which is an awareness of a shared feeling in that the partaker attends a performance to have a shared feeling and to be aware of that shared feeling – is then a mode of social bonding. Although rasa is most often discussed as an exchange between performer and partaker, performers partake of each other’s performances, and partakers experience each other’s responses, meaning that rasa becomes a flow of intersubjectivity between performer and partaker, partaker and partaker, and performer and performer.

As a fundamental mode of existence, as embodied sense-making, as a way of responding to others (whether fictional or real), as a response to performance and as an act or performance in and of itself, rasa is incorporated in(to) the self. Which is to say it participates in constituting the constantly becoming self. Crucially, rasa constitutes the constantly becoming social self.