Chapter 7

Visual storytelling with data

Abstract

This chapter discusses how narrative visualization differs from other forms of storytelling and the key elements of story structure for telling meaningful data stories with data visualization. We explore storytelling paradigms and story psychology as the basis for establishing a framework for narrative data visualization.

Keywords

storytelling

data storytelling

data journalism

Zeingarnik effect

visual narrative

genre

“To write it, it took three months; to conceive it three minutes; to collect the data in it, all my life.”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald

First off, take a deep breath. We made it through chapter: Visual Communication and Literacy. I know the information was dense, but I assure you that an understanding of the long and winding evolution of visual communication will only serve you in the future as you put these concepts into practice within your organization and ground how data visualization is made an important part of your visual communication strategy. Thus, I will end our prior discussion on visual communication and literacy with a quote from American poet, novelist, and contributor to the founding of New Criticism, Robert Penn Warren, who infamously wrote that, “History cannot give us a program for the future, but it can give us a fuller understanding of ourselves, and of our common humanity, so that we can better face the future.” Going forward, we will see the echoes of Penn’s words as we not only apply the context of the evolution of visual communication to storytelling, but also to cognitive and artful design considerations necessary in a visual data culture.

I intentionally ended the previous chapter with a bit of a cliffhanger, talking about the power of stories as a mechanism to move information from communication and into understanding. We saw, too, in chapter: The Data Science Education and Leadership Landscape, how the ability to tell meaningful data stories will be of paramount importance in new roles in data science and data visualization going forward. Storytellers like Robert McKee or Neil deGrasse Tyson or even Francis Ford Coppola (from whom I will share an anecdote later in this chapter) are masters of their craft. They (to again reference the previous McKee quote) “unite idea with emotion.” They have embraced the storytelling paradigm to engage their audiences in learning complex information in a way that is visual, memorable, and fun—something we can learn from as we build a storytelling strategy around how we see and understand data and information. Storytelling is a skill and it takes (copious amounts of) practice.

As humans, we are hard-wired to communicate, to learn, and to remember visually, a premise we have touched on already and will continue to explore deeper in the chapter to follow. Storytelling leverages these native cognitive characteristics, yet alone it does not provide the value that we need when using visualization to communicate in an increasingly more complex world. The most interesting thing about storytelling—visual or otherwise—is not simply the actual story we are telling: it is how we tell it. Storytelling is not just about scripting a compelling narrative to exchange ideas and information, but it is about painting the narrative into a picture that effectively communicates the story itself in a meaningful, memorable, and inspiring way. Yes, it is uniting idea with emotion, but it is even more important for data—even visual analytics expert and technical evangelist Andy Cotgreave (2015) remarked it so in a Computerworld article pointedly entitled “Data without emotion doesn’t bring about change.”

When we think about storytelling in the context of data, we should first and foremost understand that narrative visualizations should always put data at the forefront of the story. However, data stories differ from traditional storytelling that typically chains together a series of causally related events to progress through a beginning, middle, to arrive at an end. Data stories, instead, can be similarly linearly visualized or not, or they can be interactive to invite discovery, solicit new questions, and offer alternative explanations. However, while today’s robust visualization tools support richer, more diverse forms of storytelling, crafting a compelling data narrative requires a diverse set of skills. In this chapter, I will clarify how narrative visualization differs from other storytelling forms and identify elements of story structure for telling data stories with visualization—including nuances of genre, visual narrative design, and narrative structure tactics best suited for the complexity of the data, the intended audience, and the storytelling medium. First, let us examine exactly what the data story is.

7.1. The storytelling paradigm: defining the data story

The storytelling paradigm—or, the narrative paradigm—is a theory proposed by Walter Fisher, a 20th century philosopher, who believed that all meaningful communication is a form of storytelling or of providing a narrative report of events and information. According to Fisher, human beings experience and comprehend life as a series of ongoing narratives. Each has its own conflicts, characters, beginning, middle, and, ultimately, an ending. Additionally, all forms of human communication are to be seen, fundamentally, as stories shaped by history, culture, and character. And, it is important to note that these narrations are not limited to nonfiction, but rather, we tend to gravitate toward fiction more so perhaps than anything. It is, as Newman University provost Michael Austin writes in his book Useful Fictions, one of humanity’s most defining paradoxes: that we cannot survive without a steady flow of information, but that it does not necessarily have to be accurate. We need myths to help comprehend life’s mysteries, as well as stories that thrill and scare us without any true or factual basis, just as much as we need comedic, dramatic, or otherwise fantastic stories to entertain and inform us. Stories—of fact or fiction—help us navigate the world around us.

The storytelling paradigm meets the data story where good ideas fall victim to the melee of buzzwords. Recently, the word “storytelling” has been applied in the data industry everywhere from a tool feature or functionality, to part of the skillset of a visual analyst, or even to a job role itself. One can rarely talk about data visualization without the word storytelling cropping up somewhere in the conversation. This leads to a larger problem: as Segal and Heer (2010) have rightly pointed out, though data visualization often evokes comparisons to storytelling, the relationship between the two is rarely articulated. And firsthand research supports this: in our recent research at Radiant Advisors wherein we surveyed the end user market on their priorities in tool evaluations and purchase decisions, we found that storytelling ranked right in the middle as both the “most important” and “least important” feature of data visualization tools. Among other things, this tells us that it is likely that the concept is still largely ambiguous. Outside of data journalism where data storytelling has become the new bread and butter of the editorial and news world, the rest of us have yet to quite figure out how to use data storytelling in our increasingly data-dependent and visual organizations.

While data stories do share many similarities with traditional stories, they are, in fact, quite different. Visual storytelling could be thought of, if anything, as a visual data documentary. By definition, these are quantitative visual narratives told through sequential facts and data points. While it bridges the gap between the data and the art (both of storycraft and of design), in visual storytelling we use visualizations primarily as purveyors of truth. What makes data visualization itself different from other types of visual storytelling is the complexity of the content that needs to be communicated. Thus, data storytelling is essentially information compression—smashing complicated information into manageable pieces by focusing on what is most important and then pretending it is whole and bound entirely within the visualization(s) used to illustrate the message. Later in this chapter, we will review a few examples to help illustrate this point.

To facilitate storytelling, graphical techniques and interactivity can enforce various levels of structure and narrative flow (for example, consider an early reader picture book, which illustrates salient points with a visual—sometimes interactive—to emphasis key points of learning). And, though static visualizations have long been used to support storytelling, today an emerging class of visualizations that combine narratives with interactive data and graphics are taking more of the spotlight in the conveying of visual narratives (Segel & Heer, 2010). In the sections that follow, we will focus on the frameworks for narrative visualization as well as a few key steps to telling stories with data visualization.

7.2. A brief bit of story psychology

Humans have a deep-seeded need for stories, data-driven or otherwise. Let us take this opportunity to briefly review both an anthropological perspective on our love of stories, as well as how this is supported by our cognitive hardwiring.

7.2.1. An anthropological perspective

Stories give us pleasure; we like them. Stories teach us important lessons; we learn from them. We think in stories—it is how we pass information, through myths, legends, folklore, narratives. Stories transport us—we give the author license to stretch the truth—though, in data storytelling, this license extends only as far as it can before the data loses its elasticity and begins to break down. (Data stories have a certain degree of entropy, the unpredictable ability to quickly unravel into disorder if not told properly.)

Storytelling has been called the world’s second-oldest profession, and, alongside visual expression is an integral part of human expression. All human cultures tell stories, and most people derive a great deal of pleasure from stories—even when they are not true (honestly, perhaps the more fantastical they are, then more pleasure they induce—think of fairy tales set in enchanted lands, or the far reaches of space in science fiction). Not only are we drawn to fiction, but also we are willing to invest significant resources into producing and consuming fictional narratives. How significant? The 2011 adventure flick Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, staring Johnny Depp and Penelope Cruz, currently holds the rank of the most expensive movie ever made by Hollywood (a title formerly held by James Cameron’s Titanic) at $397 USD (Gibson, 2015). Likewise, The Hobbit series earns the top spot of a back-to-back film production with combined costs up to $745 million USD in 2014, and still counting (Perry, 2014).

So, why do we tell stories? Well, it is all part of the anthropological evolution of communication, one that, as Michael Austin wrote in the introduction to Useful Fiction, is very young yet already crowded with books and articles attempting to explain the cognitive basis of all storytelling and literature. In fact, there is no shortage of contributions to the field of story psychology that try and tweeze out the exact underpinnings of the importance of a good story. We could, however, venture to provide two possible contenders for why we tell stories: the need to survive and the need to know.

7.2.1.1. Survival of the fittest

As much as philosophers might like to suggest, human reason did not evolve to find truth. Rather, it evolved to defend positions and obtain resources—often through manipulation. Likewise, natural selection does not care if we are happy, but only that we survive (Austin, 2010). Our cognitive architecture is designed through instinct and evolution to have anxiety—worry about death, pain, etc. These are drivers for natural selection. Thus, predation narratives get our attention very quickly. Think of some of the earliest classic texts that are still popular today that focus on overcoming the most seemingly unbeatable of characters or situations (ie, Dracula or Frankenstein)—they have some degree of predation, many playing on intrinsic chase-play psychology that is universal in many breeds of animals, including humans.

As a precursor to survival, one thing we have always had to do is to understand other people. In fact, the most expensive cognitive thing we do is to try and figure other people out: predict what they are going to do, understand relationships, and so forth. And, when (or if) we succeed, this is an important part of survival—winning—another narrative that gives us pleasure because it brings much needed confidence back to our abilities to dominate and prevail. In this light, our stories are almost predictive in quality: if we know what worked in the past, it might help us to imagine what might happen in the future. Stories are guides.

7.2.1.2. The cliffhanger

Another reason for telling stories is because we all need resolution to ongoing questions and curiosities. It does not have to be a happy ending, but we need an ending—we simply cannot handle cliffhangers. This is known as the Zeigarnik effect, named for the Soviet psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik, who demonstrated in the early 1900s that people have a better memory for unfinished tasks that they do for finished ones (Austin, 2010). From its initial home in the annals of Gestalt psychology, the Zeigarnik effect is now known as a “psychological device that creates dissonance and uneasiness in the target audience.”

Basically, this Zeigarnik effect speaks to our human need for endings—for closure. It is why television shows go to commercial breaks with cliffhangers, or why we will hang on through a Top 10 radio show and listen to songs we do not like just to get to that week’s #1 hit. We come back, almost unfailingly, for resolution. Theoretically, a story ends with two simple words—the end—but even that does not always mean the story is over. Sometimes we are not ready emotionally for an ending, and we develop things like sequels. No matter the story’s purpose—to focus, align, teach, or inspire—we build narratives the way we do to foster imagination, excitement, speculation—and successful narratives are those that introduce (get attention) and then resolve our anxiety (give a satisfactory ending).Thus, stories are therapeutic.

7.2.2. A cognitive perspective

Stories are not just fun ways to learn or pass the time—they are a little bit like metaphorical fireworks for our brain, or at least a certain percent of it.

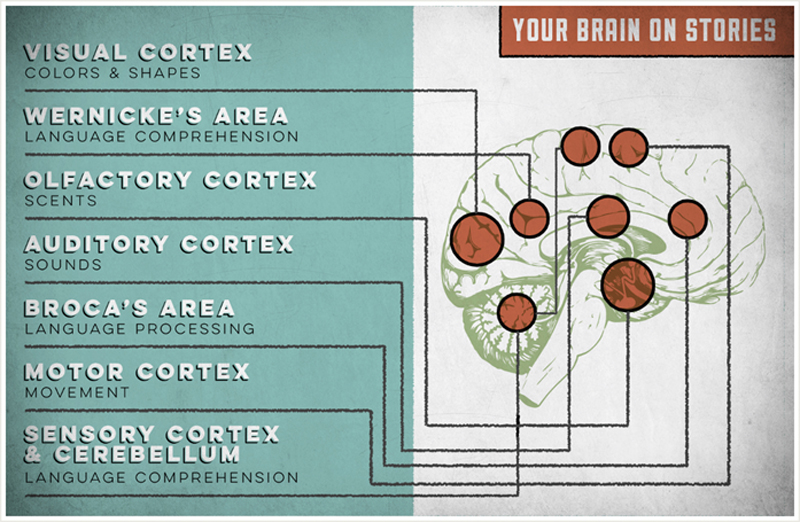

When we are presented with data, two parts of our brain respond: Wernicke’s area—responsible for language comprehension—and Broca’s area—responsible for language processing. Consider this: when you share facts and information—pure data—your audience will do one of two things. They will either 1) agree or 2) disagree. They will make a decision, a judgment, and move on. Hence, only the above named two parts of the brain have to bother to react to this—it is a simple input and respond transaction. However, when presented with a story, five additional areas of the brain are activated, including the visual cortex (colors and shapes), the olfactory cortex (scents), the auditory cortex (sounds), the motor cortex (movement), and the sensory cortex/cerebellum (language comprehension).

In a presentation on the neuroscience of storytelling, Scott Schwertly, the author of How to Be a Presentation God and CEO of Ethos3, said that the best way to engage your audience—no matter what you are presenting—is by telling a story. It is the most efficient way to activate and ignite the often-elusive audience brain. Figure 7.1, created by Schwertly, illustrates the brain on stories.

Figure 7.1 Your brain on stories. This visual illustrates which parts of the brain activated by a story

7.3. The data narrative framework

Storytellers through the ages have recognized that successful narratives can be shaped into recognizable structures. American writer Kurt Vonnegut is quoted, somewhat famously, as having said that “there is no reason that the simple shapes of stories can’t be fed into a computer – they have beautiful shapes.” Indeed, the structure of a narrative—whether it is a fictional novel or a data documentary—is beautiful in its growth, form, style, and message (even if that beauty is somewhat chaotic, which is something many writers may attest to, too). Similar to how traditional storytelling strategies vary depending on genre and media used, data stories can also be organized in linear sequences or otherwise constrained to support richer and more diverse forms of data storytelling and through more forms of storytelling media. However, with fiction, the goal is to draw people in through various psychological tactics—developing character, plot, storyline, etc.,—yet a documentary is more interested on concentrating on every element that success is dependent on the viewer deriving a larger understanding about the topic. It worries itself over building an argument based on evidence.

In his book The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker (2004) established seven plots that are the basics of plotwriting. Booker classified these as: overcoming the monster (Dracula); rags to riches (Cinderella); the quest (Iliad); voyage and return (Odyssey); comedy (Much Ado About Nothing); tragedy (Macbeth); and rebirth (A Christmas Carol). You can relate these plot types to some of the points made in discussions this far in this chapter already. For the purposes of storytelling, the basic “plots” of visual data stories can be rearticulated as the following:

• Change over time—see a visual history as told through a simple metric or trend

• Drill down—start big, and get more and more granular to find meaning

• Zoom out—reverse the particular, from the individual to a larger group

• Contrast—the “this” or “that”

• Spread—help people see the light and the dark, or reach of data (disbursement)

• Intersections—things that cross over, or go from “less than” to “more than” (progression)

• Factors—things that work together to build up to a higher level effect

• Outliers—powerful way to show something outside the realm of normal

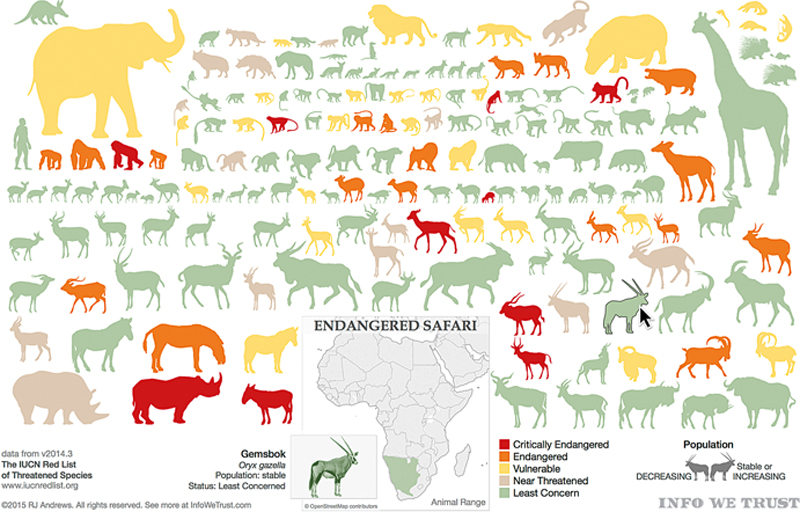

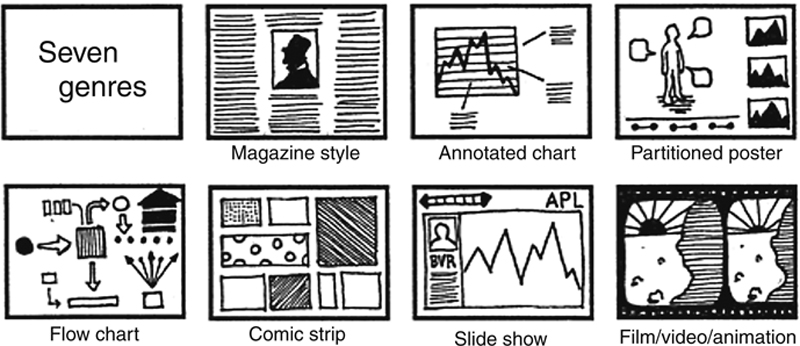

Beyond story plots, the other half of the data narrative framework equation is visual narrative tactics and design space considerations. While the chapter next is devoted to design considerations for data visualization, we could also consider how story genre can affect the nature of a visual data story as a distinct subject. To this point, Segel and Heel (2010) organized data stories into eight genres of narrative visualization that vary primarily in terms of the number or frames and the ordering of their visual elements. These genres, illustrated in Figure 7.2, are the magazine style, the annotated chart, the partitioned poster, the flow chart, the comic strip, the slide short, and finally, the conglomerate film/video/animation.

Data visual narratives are most effective when they have constrained interaction at various checkpoints within the narrative, allowing the user to explore the data without veering too far away from the intended narrative (the wisdom of guiding the reader versus allowing the reader to define their own story, like those “choose your own adventure” books you may remember from your childhood). Visual cues for storytelling include things like annotations (labels or “story points” as they are often called) to point out specific information; using color to associate items of importance without having to tell them; or even visual highlighting (ie, color, size, boldness) to connect elements. As a necessary aside, it is important to note that some data visualization tools are being enhanced with storytelling capabilities. Tableau, for example, has its storypoints; Qlik storytelling “snapshots”; YellowfinBI its storyboard. With these tools and more building capabilities intended to be used to facilitate data storytelling, visualizations are designed—or at minimum, intended to be designed—to feel less like data and more like story illustrations.

7.3.1. Inverted journalism pyramid

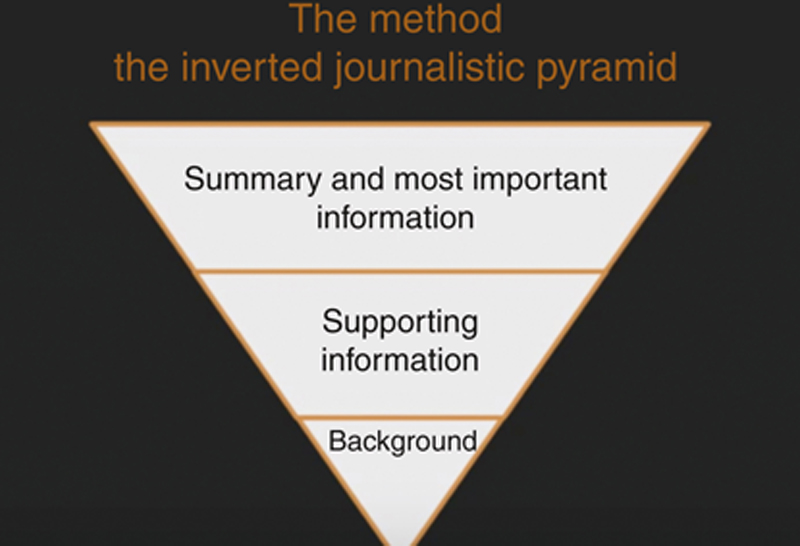

One simple shape that can be used to tell a data story is that of an adapted model of the inverted journalism pyramid. The inverted pyramid is primarily a common method for writing news stories and as such is widely taught to mass communication and journalism students to illustrate how information should be prioritized and structured in a text. It is also a useful mechanism to tell a meaningful data story—or to activate belief with as little information (or as much information condensed) as possible.

Drawn as an upside down triangle (see Figure 7.3), the inverted journalism pyramid teeters with the tip of the triangle at the bottom of the shape. The most important, substantial, and interesting information lives at the widest portion of the triangle (the inverted “top”), while the tapering lower portions show how other material—like supporting information and background information, respectively—illustrate the other materials’ diminishing level of importance. Ultimately, this system is designed so that information less vital to the reader’s understanding comes later in the story, where it is easier to edit out for space or other reasons, and where the audience already has the knowledge to make new connections and draw their own conclusions. This also gives the story the ability to end with a call to action and spur decision-making. The same technique applies to data stories.

Figure 7.3 The inverted journalism pyramid

7.4. Five steps to data storytelling with visualization

Today’s visual narratives, according to a recent article in The Economist, “meld the skills of computer science, statistics, artistic design, and storytelling” (Segel & Heer, 2010). Building upon that sentiment, at a recent annual data storytelling and visualization conference, Tableau Tapestry, hosted by data visualization vendor Tableau, Hannah Fairfield, Senior Graphics Editor for the New York Times began her keynote presentation by saying, “Revelation is always based on prior knowledge.” These two quotes speak to the compounding nature of crafting a compelling data story, which we can break down into five pertinent steps requisite of storytelling through data visualization:

7.4.1. First, find data that supports your story

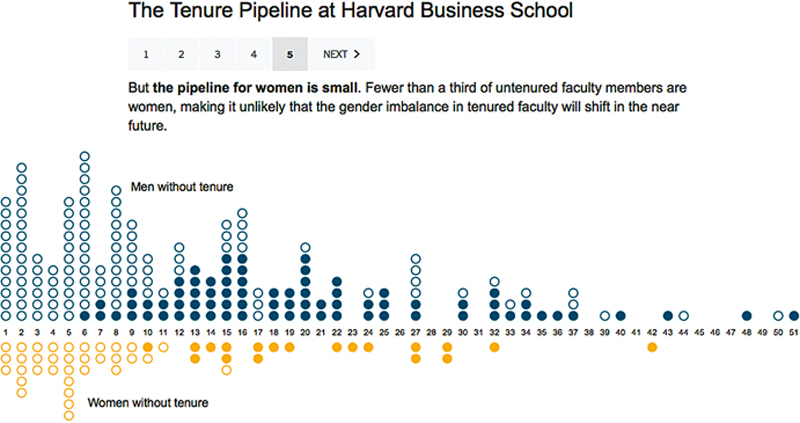

The first step in telling a useful data narrative depends on finding the data that supports your story—as both supporting background material and as fodder for stoking the fire of inquiry and discovery. Part of the revelation of storytelling is testing a hypothesis—of going through the scientific process to ask questions, perform background research, construct and test one or many hypotheses, and analyze results to draw and communicate a conclusion. However, finding data to support a story does not necessarily require scientific data. As an example, see Figure 7.4. This visual, produced by the New York Times builds upon itself in a series of five compounding animations that move the data story one step farther with each click. Using individual faculty member data from Harvard Business School (HBS), this visualization shows the tenure pipeline at HBS over the span of the next 40 years: the darker circles represent the currently tenured faculty members for men and women; the open circles show the pipeline of that gender equity over the next four decades.

Figure 7.4 The tenure pipeline at Harvard Business School, produced by the New York Times. Step through the visualization online at http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/02/27/education/harvard-tenure-pipeline.html (Source: Harvard Business School; individual faculty members).

This data, while not scientific, is nevertheless meaningful and applicable to a scientific process that melds data and storytelling to produce revelation. If you visit the visualization online and watch as it builds upon itself, it is easy to see that it is unlikely that the gender imbalance in tenured faculty will shift in the near future. In fact, that very revelation is the story of the graphic that we can discover throughout the scientific method of exploring the question of gender equity in academia—“what will tenured faculty look like in the future?” We start out with one level of knowledge—the current situation of tenured faculty at HBS—and through a series of steps that add more data and information to the scenario, this allows us to form a hypothesis (that it likely will not change dramatically), and then test that through even more data until we reach an informed enough point that we can share our discovery.

7.4.2. Then, layer information for understanding

There is no shortage of information or data sets floating around that we can use to tell data narratives. But, like any craft, storytelling is not dependent on plucking out some random information and weaving a tale around it. Instead, it is more precise: figure out the story you want to tell, and then look for the data that supports or challenges that story. In other words, find a story you are interested in telling. Then, make sure that you understand your data. Remembering the inverted journalism pyramid above, think like a journalist: interview your data, ask it questions, examine it from different angles. Look at the outliers, the trends, and the correlations. These data points often have a great story to tell by themselves.

As the first step above hinted at, knowledge is incremental. Every piece of information that we learn is founded on something we have already learned before (for a simple example, we learn letters, then words, then phrases, and then sentences). Thus, layering information is incredibly critical: it is a tool you can use to bring your audience through a fairly complex story by guiding them step-by-step. If you viewed the above visualization on the New York Times website, you will easily see how each step in the series builds upon previous interpretations of the data. However, compounding builds in visualization are not the only technique to achieve this layering of insight and understanding. We can also achieve this effect through sequencing types of visualizations, or by drilling deeper into one single visualization, too.

7.4.3. The goal is to design to reveal

It should go without saying that data visualizations cannot be relied upon to tell the story for you. As tools, charts cannot do it all. Rather they should act as an aid—the illustrative accompaniment to your narrative. Likewise, various types of visualization can present the data properly, but still fail to tell a story. Visual data storytelling should give analysts and audiences a nugget of information that can continue to be refined and expanded to tell or receive a story. Thus, you must choose your data and your visual form carefully so that the two work together toward communicating one message.

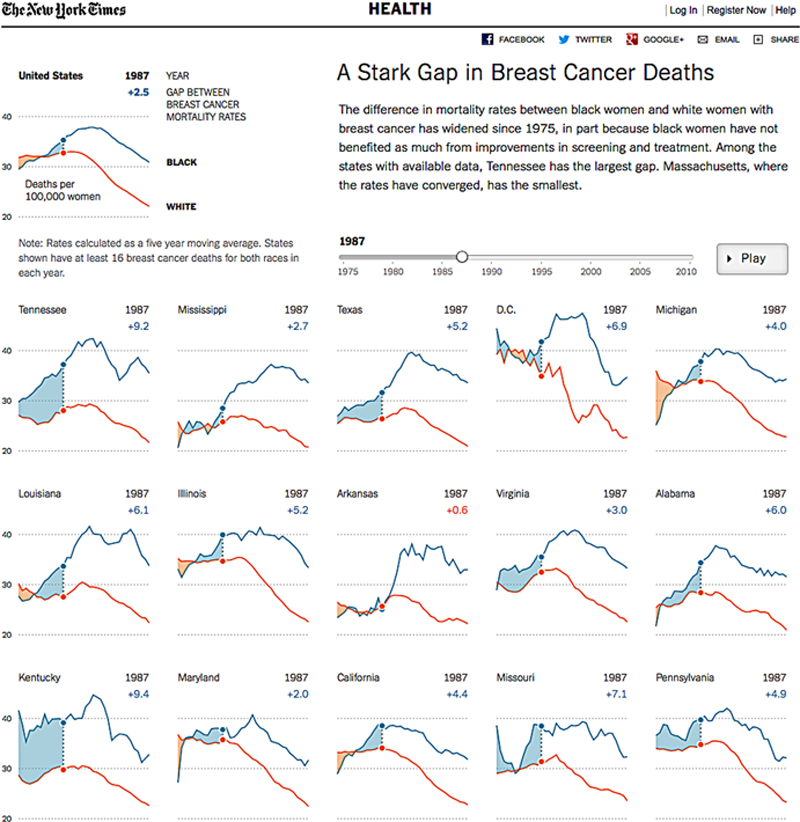

To accomplish this, start by stripping out information that is not necessary, and design the data story in a way that leaves the audience with a single, very potent, message. Focus on the most powerful elements; however, understand that these are not always the most obvious trends or elements. To illustrate this example more clearly, see the snapshot of another New York Times graphic in Figure 7.5.

Figure 7.5 A stark gap in breast cancer deaths, produced by the New York Times. Animated visualization online at http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/12/20/health/a-racial-gap-in-breast-cancer-deaths.html

This graphic shows the difference in mortality rates between women of color and white women with breast cancer, and through animation (which you can watch at the URL provided) emphasizes how this gap has widened since 1975. While the overall occurrences of women’s deaths due to breast cancer have gone down, the more powerful element of the story is the continued gap between women of color and white women. (This visualization shows, too, how motion and animation can be extremely powerful in data visualization as a way to tell a story through movement. We will look at this further in chapter: Visualization in the Internet of Things). Thus, the thing to remember is that when we use data visualization with the goal to design to reveal, we have to focus on the message we are trying to communicate. There is not always one truth in data, and this is where context becomes a huge element of how to tell a data story.

7.4.4. …But Beware the False Reveal

A false reveal—one that leads the audience to a false understanding of cause and effect—can be a dangerous thing. It can incite the audience to draw the wrong conclusions or take an incorrect action; it can also damage the effect of the data itself. As a visual data documentary, our data stories should be engaging and entertaining, but they should also focus on sharing the truth. Sanity checking a story is paramount to making sure stories are meaningful and compelling, but that they also make sense. While a little levity is important in data visualization and storytelling to keep the audience engaged (see Box 7.1), data stories are not the place to practice comedy. As the adage goes, correlation does not imply equal causation, though admittedly, it does make for some pretty silly stories and visualizations. Think of some of the funny data stories you have probably heard where the data, for all intents and purposes, seems to support the tale but are nothing more than nonsensical correlations. Like, for example, the parallel upward journey of amount of ice cream eaten and a rise in crime rates over the summer months. There is no causal relationship between ice cream consumption and crime; they just both happen to go up when another variable—temperature—goes up. Another fun example is the familiar beer and diapers story—a popular data mining parable now firmly enshrined in BI mythology that says that some time ago, Wal-Mart decided to combine the data from its loyalty card system with its point of sales system and discovered, unexpectedly, that, on Friday afternoons, young American males who buy diapers also have a predisposition to buy beer (Whitehorn, 2006). Another interesting tidbit is that the number of people who drown by falling into a swimming pool correlate almost exactly with the number of films actor Nicolas Cage appears in (for more of these with accompanying data visualizations, check out Tyler Vigen’s site, “Spurious Correlations” at www.tylervigen.com) (Box 7.1).

Of course, faulty correlations are not the only danger of a false reveal—there is also the element of bias, or intent, to tell a data tall tale. After all, we can force the data to tell the story we want it to, even if it is the wrong one. Or, we can do this inadvertently through the process of dramatizing. Engaging and inspiring storytelling is, at least in part, a function of entertainment. We are tasked not only with the need to tell a story, but to make it our story and to make it interesting. We are invited to add our opinion and spice it up a bit—add a creative flavor that spurs response and reaction. But, in addition to making sure that we do this with accuracy we should temper it with, shall we say, decorum. We can always find a way to make the data more interesting, but should do so with tact. As a rule of thumb, perhaps, we might take give more lenience with business or economics data, but should shy away from amusement factor in things like healthcare data. Again, think of building this visual story as scripting a data documentary: a nonfiction work based on a collection of data. Do like Disney in its Nature documentary series and make it interesting and emotional, but without compromising truth and relevance (Box 7.2).

7.4.5. Tell It fast – and make it mobile

Stories, of any kind, have an inherent amount of entropy as mentioned before. Whether it is because of timeliness (in either topic and data), audience attention span, or market need, they can quickly unravel and fall apart. Stories have the most potency when they are happening (as events occur). Data journalists are taking this to heart in live models that keep track of events as they happen in real time—think political elections or disaster scenarios. The timestamp on when data is reported—or a visualization created—can be a big difference in how it is interpreted or the impact it makes.

Second, mobile requires wise editing. We have to be aware of form factor limitations and rethink the way storytelling via mobile devices happens. Mobile has already been a game changer in data visualization design in many ways and we can expect to see even more impacts in the coming years. This means that we have to change the way we think about storytelling—can we tell the same story through various mediums, including desktop, print, and mobile? It is unlikely.

7.5. Storytelling reconsidered, the probability problem

As you can tell from the above, we make sense of our world by telling stories about it. We could rightly even speak of a human predisposition to think and to know in terms of stories. Storytelling is in our DNA, and it has worked pretty well for us for thousands of years.

However, what if the structure of a story, like the schema of a data model itself, embodies a kind of a priori representation or understanding of the world? We are all aware of the shortcomings of the data model as a structure. By imposing a rigid schema and organizing data in specific ways, a data warehouse data model attempts to optimize for most BI workloads. It is able to tell a certain kind of story—but it is much less adept at telling others. Have we ever thought about the similar trade-offs and optimizations that go into structuring the stories that we tell every day?

These questions were the focus of an article penned by industry writer Stephen Swoyer in a 2013 issue of RediscoveringBI, for which at the time I was still Editor-in-Chief. Like many of Stephen’s pieces, this article has stuck with me because it does what so little articles seem to do these days, or what I have even provided thus far in this chapter. It hints not to the value of data storytelling, or how to do it, but instead it tackles something bigger that often gets overlooked: the problem of storytelling. Perhaps even more important, it poses a question were were not expecting: what if the very structure of the story itself—with its beginning, middle, and end; its neatly articulated sequencing and its emphasis on dramatic developments—is problematic?

Rather than recreating his piece, Stephen and I updated, edited, and condensed the original article and have repurposed it within the context of our discussions in this chapter.

7.5.1. The storytelling paradox

Certainly, in telling stories we have been known to exaggerate, to misrepresent, or to invent events. That is the very stuff of dramatic flair. However, for data storytelling, the problem is much deeper than this. It has to do with the structure of the story itself. To put it in the language of probability theory, our tendency to interpret events by telling stories about them is a way of imposing a deterministic structure on something that is not properly deterministic.

For most of human history, this was not a problem. We simply did not have the means to identify, qualify, or quantify its effects. Today, the combination of statistics and data gives us this means. As a tool for interpreting and understanding events, storytelling can, in some cases, be unhelpful or disadvantageous.

For example, consider the 2012 Presidential contest, when we had two different kinds of storytelling—deterministic and probabilistic—telling two very different stories about the state of the race. The former depicted an exciting, leapfrogging, neck-and-neck contest; the latter—plotted over a protracted period—suggested a mostly ho-hum race, with periodic volatility ultimately regressing over time. And that is the point. Probabilistic stories tend to be much less exciting—with fewer surprises, dramatic reversals, or spectacular developments—than those stories more deterministic and narrative-driven. In a probabilistic universe, for instance, there is a vanishingly small chance (let us say 0.00001 probability) that vampires or zombies can exist, let alone live among us (which puts a serious damper on letting our imaginations run wild—stories are pleasure-inducers, remember?). Likewise, we tend to need to give more weight to anomalies than we probably should. After all, we like stories to be exciting in some capacity—thrills, adventures, insights, suspense…again, those trappings of dramatic flair.

Statistical storytelling is probabilistic, not deterministic. In this sense, it is fundamentally at odds with the deterministic story craft, we have practiced for all of human history. The two are not irreconcilable, but they do not tell quite the same story (pun intended).

The long and short of it is this: human beings are super bad at thinking probabilistically—even when the issue is not something fantastic, like the existence of vampires or zombies. Most of us cannot properly interpret a weather forecast, especially one that calls for precipitation. If the forecast for the La Grange, GA, for example, predicts a 90% chance of rain, this does not mean there is a 90% chance, it is going to rain across all or most of La Grange; nor does it mean that 90% of the La Grange region is likely to get rained on. It is rather a prediction (with 90% probability) that rain will develop in some part of the forecast area during the stated period. This might well translate into widespread precipitation. It might not. This is not the way most of us tend to interpret a weather forecast, however. (Or, if you are like me, you can ignore this altogether and check an app, like the aptly named Umbrella, which tells me in a glance if I should grab my umbrella.)

The problem, then, is two-fold: (1) human beings seem to have a (hard-wired) preference for narrative or deterministic storytelling; (2) human beings likewise tend to have real difficulty with probabilistic thinking. In most cases, we want to translate the probabilistic into deterministic terms. We dislike open-endedness, indeterminacy—we want to resolve, fix, and close things. We have this nasty habit of wanting our stories to have tidy conclusions, resolute endings (remember the cliffhanger?).

We need to be especially mindful of these issues, if we expect to use analytic technologies to meaningfully enrich business decision-making. Viewed narrowly through the lens of data, statistical numeracy—that is, the application of statistical concepts, methods, and (most important) rigor to the analysis of data—promises to contribute to an improved understanding of business operations, customer behaviors, cyclical changes, seemingly random or anomalous events, and so on.

Our embrace of statistics will count for little—regardless of the size of our data sets, the complexity of our models, the power of our algorithms, or even how we visualize it all—if we fail to account for that most critical of variables: the human being who must first conceive of and then interpret (the results of) an analysis. Professional statisticians pay scrupulous attention to this problem: it is a critical aspect of research and preparation—of rigor—in statistics.

But even professionals can make mistakes. What is more, with the rise of big data analytics and the insurgence of commonly called self-service technologies, we are attempting to enfranchise nonprofessional users—business analysts, power users, and other savvy information consumers—by giving them more discretion to interact with and visualize information. This usually means letting them have a freer hand when it comes to the consumption, if not to the selection and preparation, of data sources and analytic models. In a sense, then, practices such as analytic discovery propose to enlist the business analyst as an armchair statistician, giving her access to larger data sets—compiled (or “blended”) from more and varied sources of data—in the context of a discovery tool that exposes algorithms, functions, visualizations, and other amenities as self-servicable selections.

We will get into more technical discussion on architecting for discovery later, so let us put a pin in this digression for now and stick to storytelling. This last bit is not to dismiss or undermine the potential value of analytic discovery as a means to data storytelling. It is rather to emphasize that our ability to make use of information is irreducibly constrained by our capacity to interpret it. We are projecting our own biases, desires, and preconceptions into the “insights” that we produce. We must be alert to the possibility of hidden or nonobvious human factors in analysis: this as true of interpretation as it is of preparation and experimentation.

When we are counting on our ability to make a data story sing with meaningfulness and prompt an appropriate action (or reaction), we must control for our all-too-human love of a good story. This means recognizing the storytelling capacity of the tools (such as metaphor, analogy, and idea itself) that we use to interpret, frame, or flesh out our stories. Metaphor and analogy have the potential to mislead or confound. Ideas, for that matter, can have irresistible power.

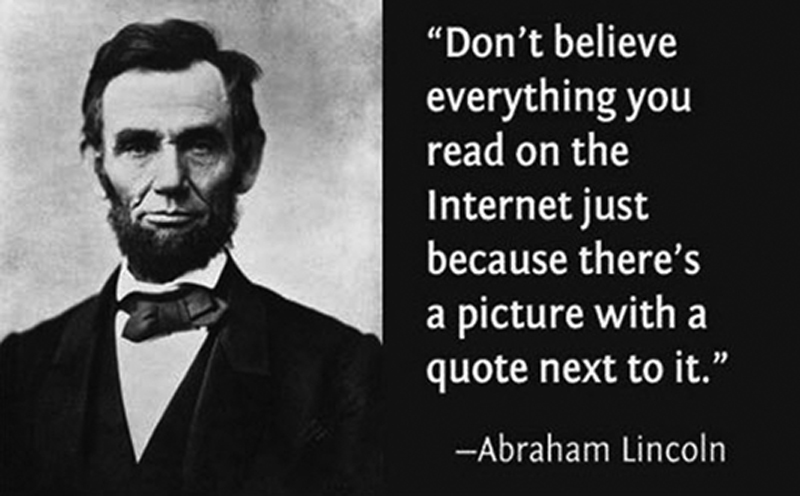

To this point, consider the “meme,” which was conceived by Richard Dawkins to describe an idea that gets promoted and disseminated—in evolutionary terms, selected for—on the basis of its cultural or intellectual appeal. If you think memes cannot mislead (for emphasis, see Figure 7.6) look to that most versatile of memetic constructs: Malcolm Gladwell’s “tipping point,” which has by now been interpreted into…almost everything. The “tipping point” even enjoys some currency among sales and marketing professionals, chiefly as a promotional tool. This is in spite of the fact that researchers Duncan Watts and Peter Dodds penned an influential paper (“Influentials, Networks, and Public Opinion Formation”) that raised serious questions about Gladwell’s theory. From a sales or marketing perspective, the tipping-point-as-meme has unquestionable promotional power; its usefulness as an analytic tool is altogether more suspect, however. No matter: as memes go, the “tipping point” is the very stuff of what American philosopher William James dubbed “sensational tang:” the kind of idea that is simply irresistible to the intellect, regardless of its validity or veracity.

Figure 7.6 I am pretty sure Mr. Lincoln did not actually say this

It is an illustrative lesson: if we expect to arm nontraditional users with statistical tools and techniques, we must attempt to control for “effects” like sensational tang. It will not be easy (Box 7.3).

7.6. Storytelling’s secret ingredient: the audience

As you can by now tell, there is a lot that goes into creating a good—hopefully great—story—from plot, to genre, to media. Depending on the story you are trying to tell, and the insight you are trying to share, shaping up your story can be like cooking a favorite recipe from memory—a little of this, a dash of that, a bit of intrigue and an element of surprise! And, like any favorite recipe, there is at least one secret ingredient. As we close out this chapter, let me share with you what I think it is by telling a story of my own.

One of my favorite storytellers of all time is Garrison Keillor, whose name you might recognize from the popular radio show A Prairie Home Companion or any number of his brilliant narrative monologs capturing the goings-on of fictional Minnesota town Lake Wobegon. If you have never heard Garrison Keillor tell a story, you are missing out on one of the finest things in life. I encourage you to switch over to NPR on weekend mornings (though it has been rumored that Mr. Keillor is neigh on retirement, so act fast!), or pick up a copy of one of his works at your local bookstore. Keillor’s steady, rhythmic storytelling style is one that has the power to weave narration like Rumpelstiltskin spun straw into gold: one strand a time. And, while Keillor is somewhat known for offering a goldmine of witticisms and words of wisdom, he has one quote of particular brilliance that we should raptly apply to our data storytelling strategies. He says, “I don’t have a great eye for detail. I leave blanks in all of my stories. I leave out all detail, which leaves the reader to fill in something better.”

At first take, this may seem contrary to everything that has come before. And, while I am certainly not suggesting that, as a data storyteller, you leave out the details, there is a golden nugget of wisdom—that secret ingredient, if you will—in Keillor’s quote. “I leave blanks in all of my stories…which leaves the reader to fill in something better.” This is the essence of reader-driven stories.

Ultimately, one of the most important aspects of a great story is its ability to invite the reader to become part of the discovery. As a storyteller, your job is to give your audience all the data pieces needed to assemble the insight, and then sit back and wait for it to unfold. This is the “ah-ha!” moment of a great story, when your audience goes from passively listening to thinking (or saying), “oh my goodness, that’s what’s going on.” American film director M. Night Shyamalan has a fastidious knack for this special brand of user-oriented storytelling to lead up to the moment of discovery (usually accompanied by some kind of bizarre plot twist). For example, when we all realize that there are not really monsters roaming The Village or that moment at the end of The Sixth Sense, when the audience suddenly realizes that Bruce Willis has been dead the whole time. We had listened to the story for a good while, seen all the little hints and clues dropped along the way, and layered them on top of each other to reveal one, jaw-dropping insight: the kid can only see dead people, and no one else seems to acknowledge Bruce Willis the entire movie. Oh my sweet, sweet climactic moment: Bruce Willis is a dead guy!!! It is satisfying, gratifying, and the best way to end a story—when you (the viewer, listener, or otherwise raptly engaged recipient of the story) are a part of telling it.