Chapter 13

The need for visualization in the Internet of Things

Abstract

This final chapter looks forward to set our sights on the future—how the world of data will change in the days ahead, and the important emerging (and especially visual) technologies that will pave the way to getting us there.

Keywords

Internet of Things (IoT)

big data

mobile

interaction

animation

streaming

wearable

playful data visualization

gamification

gameplay

personal visual analytics (PVA)

“Dreams about the future are always filled with gadgets.”

—Neil deGrasse Tyson

Data is powerful. It separates leaders from laggards and drives business disruption, transformation, and reinvention. Today’s fast acceleration of big data projects is putting data to work and already generating business value. The concept of achieving results from big data analytics is fast becoming the norm. Today’s most progressive companies are using the power of data to propel their industries into new areas of innovation, specialization, and optimization, driven by the horsepower of new tools and technologies that are providing more opportunities than ever before to harness, integrate, and interact with massive amounts of disparate data for business insights and value. Simultaneously, with a resurgence of the role and importance of data visualization and the need to “see” and understand this mounting volume, variety, and velocity of data in new ways we—business people, knowledge workers, and even for our personal data use—are becoming more visual. The premium on visual insights is becoming increasingly dominant in all things information management, as well as in every day business life. This is the heart of the imperative that is a driving force for creating a visual culture of data discovery. The traditional standards of data visualizations are making way for richer, more robust, and more advanced visualizations and new ways of seeing and interacting with data, whether on the desktop or on the go. In a nutshell, that has been the core premise of this entire book, and the imperative to create a visual culture of data discovery is something that will only continue as the era of the Internet of Things (IoT) unfolds.

As we have progressed through each chapter of this text, we have focused primarily on how the data industry as we know it has changed, or how it is changing. Now, as we embark on our final chapter and bring this book to a close, I would like to take another step forward and set our sights on the future—how the world of data will continue to change in the days going forward, and the important emerging technologies that will pave the way to getting us there—and those that we are just now beginning to catch glimpses of the most bleeding edge of technology. These highly visual technologies will be those that turn human data into meaning, both for the business and for the individual.

This final chapter will take a high-level look at advanced and emerging visual technologies and the need for data visualization in the Internet of Things. We will look at data in motion through animation and streaming, explore highly interconnected mobile strategies and an interconnected web of wearable devices, and, finally, take a look into gameplay and playful data visualization backed by machine learning and affective computing technologies, including augmented reality.

13.1. Understanding “data in motion”

Now, there are a few ways to interpret the phrase “data in motion” that warrants a bit of upfront clarification so that we are all on the same page. One definition of “data in motion,” and perhaps the more traditional, is a term used for data in transit. It speaks to the flow of data through the analytical process as it moves between all versions of the original file, especially when data is on the Internet and analytics occur in real-time. This definition of data in motion represents the continuous interactions between people, processes, data, and things (like wearable devices or online engagement modules) to drive real-time data discovery. While this definition is certainly important, as we discuss emerging technologies and the predictive value of analytics in the IoT, think of data in motion a bit more visually and beyond a simple process movement. If you are familiar with the concept of “poetry in motion,” consider how it could be applied to describe data in motion as the ability to watch something previously static (in the case of poetry, the written word) move in a way that brings out all the beautiful feelings and touches on multiple senses. To illustrate this a bit more clearly, think back to storytelling. We have explored the rationale for the old colloquialism “a picture is worth a thousand words” in several ways throughout this text; however, that has typically been in regard to a static image, whether one or many. Now, consider the story that could be told through a picture that moves. Like poetry in motion, think for a moment about how watching a visualization move might elicit additional emotions, or touch on multiple senses as you watch a story unfold through movement.

As an example, consider the image depicted in Figure 13.1. Drawn by the late American artist, writer, choreographer, theatre director, designer, and teacher Remy Charlip, this visual is a dance annotation, the symbolic representation of human movement drawn to guide dancers to learn and replicate dance positions. The visual, beautiful on its own, is nothing compared to the effect of watching a pair of dancers move off of paper and in the flesh. On paper it is static, or as Edward Tufte wrote in his 1990 text Envisioning Information, a “visual instant.” In motion—whether on stage, on film, or even in a practice ballroom—is something else entirely.

Figure 13.1 “Flowering Trees,” Remy Charlip’s Air Mail Dances

To visually see data in motion is to watch as trends take shape or as patterns form or dissolve. With data visualization, we can watch this movement through stop and play animation, or online on an app, as you watch your heart rate keep pace with your exercise routine through the sensors in your Fitbit, or even move as you interact and play with information and swipe your hand to literally move data with your fingertips for train-of-thought analysis on the screen of your mobile tablet.

13.2. The internet of things primer

Before we look at some of the visual technologies and advances that will contribute to the growth and dynamism of the IoT, let us take orient ourselves to understand a little bit more about what the Internet of Things is and exactly how much of an impact it holds in our data-centric future. Without this context, the importance of later discussion could be too diluted to earn the appropriate meaning.

Coined by British entrepreneur Kevin Ashton in 1999, the IoT is defined succinctly in Wikipedia as “the network of physical objects or ‘things’ embedded within electronic, software, sensors, and network creativity, which enables these objects to collect and exchange data.” It allows objects to be sensed and controlled across existing network infrastructure. It creates opportunities between the physical world and the digital. And, it applies to everything—from human generated data, to built-in sensors in automobiles, to medical devices like heart monitoring implants and sensors in neonatal hospital units, to biochip transponders on farm animals, and household thermostat systems and electronic toothbrushes. It is fair to say that the IoT is fast becoming the Internet of Everything, which itself is another term quickly becoming enshrined as part of the data industry vernacular.

Beyond the huge amount of new application areas, the IoT is also expected to generate large amount of data from diverse locations that will need to be aggregated very quickly, thereby increasing the need to better collect, index, store, and process data—particularly unstructured data—that go above and beyond traditional data management infrastructure and are partially responsible for the ongoing maturation of public, private, and hybrid cloud technologies. According to a 2014 study, approximately 77% of all newly generated data is unstructured, including audio, video, emails, digital images, social networking data, and more (Hitachi Data Systems, 2014). More important: previous predictions that unstructured data will double every three months are being realized today (Gartner, 2005) (Figure 13.2).

Figure 13.2 This Screenshot, Grabbed From www.pennstocks.la, Shows How Quickly Data is Generated Through User Interactions and Activities Online

Approximately 677,220GB was Transferred Within 30 s

Approximately 677,220GB was Transferred Within 30 s

In fact, the World Economic Congress forecasts that, over the next ten years, another 2 billion people will get online, and along with them, over 50 billion new devices (World Economic Forum, 2015). Even sooner than that, IoT data generation is going to exceed 400 ZB by 2018—nearly 50 times higher than the sum total of data center traffic (Cisco, 2014). To break that down a bit, 1 ZB is 1,000 EB; 1 EB is 1,000 PB; 1 PB is 1,000 TB; and 1 TB is 1,000 GB.

For many who are not in the trenches of these types of measurements, they are probably unintuitive and isolated, too big and too foreign to grasp conceptually, so let us break it down. Again, 1 ZB is approximately 1,000 EB. 1 EB alone has the capacity to stream the entirety of the Netflix catalog more than 3,000 times; it is roughly equivalent to about 250 billion DVDs. And 250 billion is a huge number, no matter what it counts. If you took every spoken word in the human language over time, and put it into a database, you would still only stock up about 42 ZB of language, a small fraction of the 400 estimated in the IoT by 2018.

So, with all these data, devices, and people, where is the return on investment for the costs and efforts of data infrastructure and management for the data-driven business? Industry research says that the economic value of the IoT is to the tune of $6 trillion (though some have numbers as high as $7.1 trillion). The breakdown looks something like this: predictive maintenance ($2 trillion), smart home and security ($300 billion), smart cities ($1 trillion), and smart offices and energy ($7 billion) (McKinsey Global Institute, 2015).

While this is not the place to go further into the mechanics of the data lake or the value of analytics that we can leverage the mass amount of information into, in order to make better decisions and predictions (see Box 13.1), what I want to focus on is the value of people in the IoT and how data visualization (and other visual technologies) will lead the way in change. Some of these have to do with making visualizations even more powerful through techniques like streaming an animation, others are more human-centric in design to provide the consumer value proposition to contribute even in deeper ways to data generation through wearables and personal analytics, and even still some are more interactive and focus on things like gameplay, augmented reality, or what are becoming known as “playful visualizations.” (Box 13.2)

13.3. The art of animation

Seeing information in motion ties back to our visual capacities for how we learn, communicate, and remember—which provides fodder to the old saying, “seeing is believing.” To provide the optimal example of the visual benefits of data in motion, let us return again to the construct of visual storytelling. When you think of visual stories that move, the first thing that comes to mind is very likely of television or movies and how stories are told in films. Thus, let us use that to our advantage and talk about storytelling in the language of perhaps the most innovative, visual storyteller: Hollywood.

In chapter: Visual Storytelling with Data, I shared an anecdote on storytelling from entertainment legend Francis Ford Coppola. Now, let me share another example to set the stage appropriately. A few years ago, I had the opportunity to meet actor Cary Elwes (heartthrob of the 1987 cult classic, Princess Bride, but also celebrated for his other roles in films including Twister, Liar Liar, and Saw I & II, and as maybe-maybe-not art thief Pierre Despereaux in TV’s Psych). I mention Elwes’ film credits to emphasize his breadth of experience in bringing stories—whether the fantastical or the gruesome—to life. When I met Elwes we did not talk about data—we talked about making movies, his movies specifically. But, in between his stories from the set (including when Fire Swamp flames leapt higher than anticipated and nearly caught Robin Wright’s hair on fire, to point out a photo of Wallace Shawn’s face, when he was certain that he was going to be fired from the film for his portrayal of Vizzini), the Man in Black made a remark that stuck with me as he considered the stunts they had managed to pull off with limited technology and a heavy dose of creativity and courage on the set of The Princess Bride. He said—and I am paraphrasing—“we didn’t have a green screen, as you know, so we just did it [special effects].” (FYI, though the green screen was invented by Larry Butler for special effects in the 1940 film, The Thief of Bagdad, the entirety of The Princess Bride was filmed on live sets in the UK).

Currently, it is almost hard to imagine a movie being made without the benefits of digital sorcery to fabricate everything from stunts to skin tones to entire landscapes and story settings. Even still, it is no great secret that Hollywood is now and has always been an inherently visual place: through various forms of visualization—sets, costumes, props, special effects, etc.—Hollywood has been telling us stories for years. And, they did it as effectively in the grainy black and white of old silent films (think 1902 French silent film A Trip to the Moon) as in today’s most special effect riddled blockbusters (Avatar comes to mind). When you strip away the shiny glamour and boil it to roots, this capacity for engaging visual storytelling is the direct result of one thing: they know how to bring our imaginations to life through animation. With animation, whether through capturing actors on film, using a green screen to enable special effects, or even newer technologies like computer graphics (more commonly, CG) that uses image data with specialized graphical hardware and software, we are effectively watching data in motion. The heart of animation is movement.

If the Dread Pirate Roberts is a bit outside of your movie repertoire, think instead of another prime example of visual animation: Walt Disney. It would be an understatement to say that Disney has set the bar for how stories are animated. Whether Walt himself or the Disney as we know it today, the company has been upping the anty of animated storytelling since its beginning with the release of the animated cartoon Snow White and the Seven Dwarves in 1937. Seven decades later, with films like Frozen (its most lucrative cartoon ever) and its recent purchase of the Star Wars franchise, Disney’s animation legacy continues.

Of course, the data industry is no stranger to visual stories—or to Hollywood for that matter. Vendors such as IBM, Microsoft, Oracle, and Teradata all have strong ties in the media and entertainment industry. When it comes to in-house, Hollywood-grown talent, data visualization solutions provider Tableau has put a formidable entertainment industry stake in the ground with its cofounder, early Pixar employee Pat Hanrahan, former LucasFilm CTO Dave Story, and fellow LucasFilm special effects guru Philip Hubbard. Of course, Tableau is not the only visual analytics technologies leveraging showbiz talent into doing its part to facilitate the evolution of an increasingly visual, data-centric culture in the IoT. Disruptive start-ups are taking the cue, too. For example, Visual Cue, an Orlando-based data viz start up with the mantra “pictures are a universal language” creates mosaic tile-based dashboards to tell a data story. Its founder, Kerry GIlger, spent time earlier in his career building animatronic robots and doing camera work for the Osmonds. Such examples demonstrate the ability to take a rich storytelling and/or animation heritage and bring it off the silver screen for the benefit of the data-driven business.

Animation has proven its popularity in user interfaces due to its intuitive and engaging nature. Data science research suggests that data visualization in motion through animation improves interaction, attracts attention, fosters engagement, and facilitates learning and decision-making. It also simplifies object consistency for changing objects in transition, including changes in position, size, shape, and color. For visual discovery and analysis, this gives rise to perceptions of causality and intentionality, communicating cause-and-effect relationships, and establishing storytelling narratives. However, animations can also be problematic and should not be used without a clear understanding of design principles for animation, and many researchers recommend using animation to ensure that data tells a clean story, as too many data points can confuse an audience (see Box 13.3) (Robertson et al., 2008). Further, we must understand which type of visualizations can benefit most from animation, and when to use animation for maximum advantage. Academic analysis of data visualization has indicated that participants feel engaged and enabled to collaborate using data visualization—and thus build on previously existing knowledge to earn strong support for gaining insight with an overview, patterns, and relationships in data easier to discover. In particular, animation has been found to offer significant advantages across both syntactic and semantic tasks to improve graphic perception of statistical data graphics (Heer & Robertson, 2007). However, there are many principles and design considerations for correctly using animation for data visualization, and while animation has proven its popularity in user interfaces in part to its intuitive and engaging nature, it can also make solo analysis challenging if data is not kept in context.

13.3.1. Beyond animation to streaming data visualization

Seeing data in motion ties back to the inherent need of visually seeing information move through motion and storytelling. If animation data visualization is the younger, hip brother of static data visualization or even dashboards, then streaming data visualization is its adorable baby sister (this line, referring to Tableau’s recent release of Vizable—a mobile app with the ability to edit and create new visualization on a tablet—is one I heard at the Tableau User Conference #data15 alongwith 10,000 other data users in Oct. of 2015, and I loved it so much that I am happy to repurpose it here). In this section, let us consider how animation goes next-generation with streaming data visualization.

Within streaming visualization lies the power of not only insight, but also of prediction. When you see data move, you can see trends, anticipate changes, react immediately, and write your own data story. Traditional visualization—and even the emergence of advanced visualization for visual analytics—falls short of meeting the expectations of true visual discovery. Real-time, streaming visual analytics takes visual discovery to a previously untapped level through the ability to witness data in motion for immediate time to insight. More important, seeing data in motion through steaming visualization does what static visualization simply cannot: it fundamentally shifts the discovery process from reactive to predictive. It does this through animation—the ability to see trends moving in real-time within the data that provides the opportunity to visually identify, consume, and predict changes that can be proactively reacted by the data-driven organization. This will be increasingly more valuable within the IoT, too, as the addition of sensor and device data in streaming data visualizations will give businesses unprecedented predictive insight into their business in new ways.

The difference between animated data visualization and streaming data visualization can be subtle. While both visualization types use movement to show data move, animation shows a play (or replay) of data already formed to move in a predefined way. Streaming, instead, shows data as it moves in real-time. Back to our earlier examples of animation in film, the difference in these two forms on visualization could be the difference between watching a movie (animation) and watching events play out in live TV (streaming). As another example, think about the value of real-time quotes when stock trading. For example, on NASDAQ.com, a real-time quote page shows real time information for US stocks (listed on NASDAQ, NYSE, and AMEX). It provides investors with the securities’ real-time NASDAQ Last Sale, Net Change, and NASDAQ Volume. There is tangible benefit for traders in seeing streaming data: rather than watching historical information to make the best decision possible, they can instead see information as it changes and respond immediately. Delays can result in missed opportunities and lost profits.

13.3.1.1. Visual sedimentation

One interesting way to facilitate streaming data visualization is through a process known as visual sedimentation. This process is inspired by the physical process of sedimentation, commonly understood as the deposition of a solid material from air or water, and provides a way to visualize streaming data that simply cannot be achieved in classic charts. While static charts cannot show live updates and thus natively loses the value of data in motion, our physical world is good at showing changes while preserving context (through elements like sediment, physical forces, decay, and barriers).

By definition, visual sedimentation as a visualization process is the result of deconstructing and visualizing data streams by representing data as objects falling due to gravity forces that aggregate into compact layers over time. Further, these layers are constrained by borders (walls) and the ground (see Figure 13.3). As an example, consider this: streaming data, like incoming tweets carried in through a Twitter stream, have several stages that are difficult to represent visually in a straightforward way, specifically when the effort is focused on smoothing the transition between the data stream’s focus—recent data—and the context, or older data. Within these stages, data may appear at unpredictable times, accumulate until it is processed, and need to be kept in aggregated form to provide ongoing historical and contextual significance. These challenges align to many characteristics of the visual sedimentation process as conceptualized, and with visual sedimentation, we can apply the metaphor to the visualization of data streams by mapping concepts to visual counterparts, including the following:

Figure 13.3 The Visual Sedimentation Metaphor Applied to a Bar Chart (Left), a Pie Chart (Center), and a Bubble Chart (Right) (Source: Illustrated by Huron, Vuillemot, and Fekete).

Tokens, a visual mark representing a data item arriving in the stream that has a four-stage lifecycle of entrance, suspension, accumulation, and decay

Layout, a two-dimensional geological cross-section of strata layers that houses tokens within walls, the ground, aggregated areas, and containers

Forces, like gravity, decay, and flocculation, that specify the behaviors of the tokens

Aggregated areas that represent the final state undergone by tokens that affect the visual representation of the data itself

In research presented at IEEE, researchers Huron et al., 2013 applied the method of visual sedimentation and demonstrated a toolkit for three different classic chart types: bar charts, pie charts, and bubble charts. They then demonstrated the effectiveness of this technique in a multitude of case studies, including Bubble T, an online tweet monitoring application. In Bubble T each token is a tweet filled with an avatar picture that is filtered into columns designated for each candidate. Visual sedimentation has also been used to monitor language edits on Wikipedia, to view birth and death rates in real time, and a project called SEDIMMS, a record of 20 k tweets containing both the words “M&M” and a color name name. Each tweet falls into an appropriately colored bin, and layers condense into previous dates in the bottom. (A visual sedimentation toolkit, which is an open-source JavaScript library that can be built on top of existing toolkits such as D3.js, jQuery, and Box2DWeb, is available at visualsedimentation.org.)

13.4. Human centered design in mobile(first) strategies

Data generation is becoming incredibly mobile, and everyday users are using mobile technologies to create and share more and more information about themselves—as well as having new expectations as to how they can explore their own personal analytics, too. Historically, most designers have approached the desktop side of any project first and left the mobile part as a secondary goal that gets (hopefully) accomplished later. Even with the rise of responsive design and the emphasis on mobile technologies, many designers sill begin with the “full size” site and work down to mobile. However, with the emphasis of “mobile first,” there is a growing trend in the industry to flip this workflow around and actually begin with mobile considerations and then work up to a larger desktop version—or not.

As “on the go” becomes more of a mantra than a philosophy, mobile is becoming the new normal in a rapidly mobile world. And, it does not just give us new opportunities for consuming and interacting with data and analytics. Rather, it fundamentally alters the paradigm by which we expect to consume and interact with data and analytics. Going “mobile first” brings with it the expectation of responsive and device-agnostic mobility, and demands an intuitive, hands-on “touch” approach to visually interact with data in a compelling and meaningful way. Mobile is no longer a niche market. Recent mobile statistics show that there are 1.2 billion mobile users worldwide, and 25% of these are mobile only (meaning that they rarely use a desktop device to access the Internet or desktop-based software) (Code My Views, 2015). Further, mobile apps have been downloaded a total of 10.9 billion times and mobile sales are increasing across the board with over 85% of devices web-ready. Obviously, the desktop is not going away, but, just as obviously, mobile is here to stay.

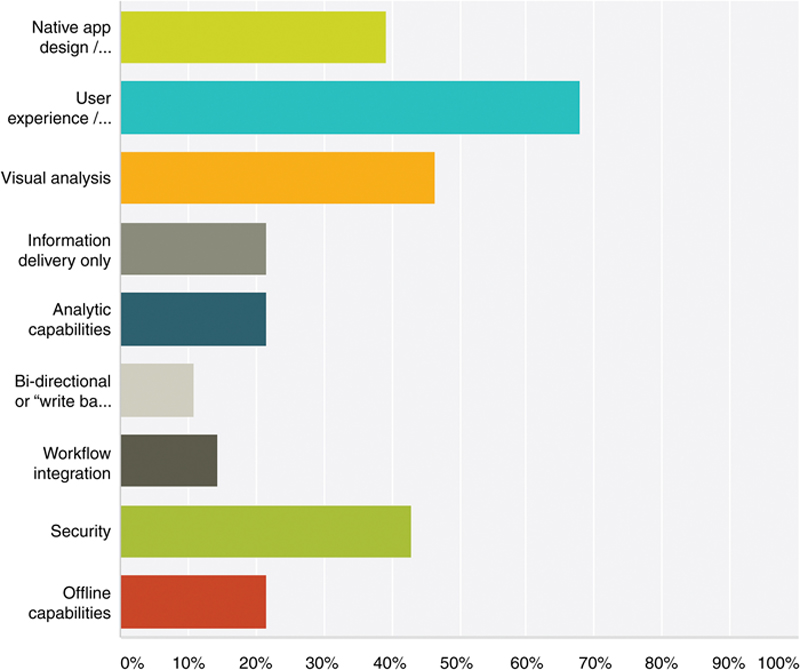

Today, regardless of form factor, mobility is being used to enrich visual analytics and enable self-sufficient users in a new era of visual discovery. New features are being added, like increased security (including biometric access through platforms like MicroStrategy, which considers itself to be the most secure mobile platform) and bidirectional, write back capabilities (offered by pure mobile-first players like Roambi and iVEDiX). While mobile moves up the ranks of desired visualization features/functionality, it has yet to reach the top; our research at Radiant Advisors has seen that user experience and interactivity is the top priority for adopters at approximately 70% (see Figure 13.4). Other leading user priority features include native app design, visual analysis capabilities, and security.

Figure 13.4 User Priorities in Mobile Data Visualization

In terms of chart types best suited for analysis on a mobile screen, traditional chart types are still on the top. Even reduced to the small constraints of precious mobile real estate, these still provide the best means of working with data visualization efficiently and intuitively, and they are among the most prolific either in mobile-first native tools or in mobile versions of popular desktop products. Among these are column charts, its cousin the stacked column chart, area charts, line charts, pie charts, comparison charts, waterfall charts, and scatter and bubble charts. There are many peripheral discussions of value in mobile but in our limited space, let us move onto look specifically at the role of the wearables market in the IoT, as well as how it is perhaps the largest contributor to the shift toward personal visual analytics (PVA).

13.4.1. Wearable devices

A wearable takes mobile beyond smartphones and tablets. Devices that can be worn on the person—your wrist, neck, finger, or even clipped to your clothing (or within your clothing)—wearables are a category of devices that can be worn by a consumer and often include tracking information related to health and fitness, or that have small motion sensors to take snapshots of data and sync with mobile devices. In a 2015 BI Intelligence Estimates Tech Report (aptly titled The Wearables Report), released by Business Insider, wearables are shown to be on an obvious growth curve with a compounded annual growth rate (or, CAGR) of 35% between 2014 and 2019. In number of devices shipped, this translates to something like 148 million new units shipped annually in 2019, up from 33 million currently in 2015. Of course, there are many consumer challenges to overcome in the wearables market, most notably things like small screen size, clunky style, and limited battery life. There are many other challenges on the business and analytics side, too.

With a huge opportunity for manufacturers to carve out niche space and make new investments, there is already diverse assortment of wearable devices available in the market today. As a quick snapshot of the current options, the following are a few favorites, some of which were introduced already in chapter: Separating Leaders From Laggards. Though the wearables market is quite vast and diverse, we will limit this to three basic categories: convenience devices, smartwatches and communication devices, and fitness trackers. Many of these may be already familiar to you. In fact, I would wager to bet that you might have one or more of the devices—or one similar—from the selection mentioned later. While this section is only a static snapshot of the current wearables market and uses a few specific products to describe how wearables affect consumers and their personal analytics, they are representative of sample of products that address the personal needs, wants, and functions of the user. Thus in this debrief we will focus on how each technology works, how it is changing or advancing the wearables market, and what type of data is generated and collected.

13.4.1.1. Disney magicband

As a personalized park option and billion-dollar big data investment, Disney introduced its MagicBands in the last bit of 2013. The bands are RFID tag bracelets, personalized with a unique ID, monogram, and chip (think: user profile) for each designated park guest. When you register a guest with a MagicBand, you also include their name and birthday, which gives Disney the data it needs to provide custom birthday offers, including notifying nearby characters in the park to sneak over and say hello. The bands can be used, simultaneously, as room keys, credit cards, FastPass ride tickets (to reduce time spent waiting in line), photo logs for character snapshots, and more. Each MagicBand contains an HF radio frequency device and a transmitter, which sends and receives RF signals through a small antenna inside the MagicBand (Disney, 2015).

Through the band, Disney can more or less keep track of everything you do in the larger park ecosystem. It can track everything you do, everything you buy, everywhere you eat, ride, and go. It can build artificial intelligence (AI) models on itineraries, show schedules, line length, weather, character appearances, etc., to figure out what influences stay length and cash expenditure to maximize guest experience and park profit. With this information, Disney is working to better the park experience for every guest, as well as to increase the value of any individual customer within the parks by encouraging them to stay longer, spend more, and come back more often. This aggregated data helps the park understand crowd movement patterns and where, in real time, crowds may be slow moving and need to be dispersed by, say a parade, happening nearby. (www.disneystore.com/magicband)

13.4.1.2. Apple watch

In our research at Radiant Advisors, we have already seen that iOS takes the market share for user preference for mobile apps (in a mobile tech survey, nearly 60% of respondents said iOS was the preferred mobile platform, more than the sum of Android—39% and Windows 14%—combined). In September 2014, Apple’s current CEO, Tim Cook, delivered his keynote introducing the Apple Watch, calling it a new relationship people have with technology—and Apple’s most personal device to “connect and communicate” seamlessly from your wrist.

On the surface, the Apple Watch can more or less do most of the things the iPhone can through both touch interaction and the Digital Crown, a little dial on the side that acts like the iPod’s clickwheel to scroll through a list or zoom in an out of a map. It has both a gyroscope and an accelerometer (to count steps and extrapolate distance, thus calculating pace and calories burned in a workout session), plus a custom sensor that uses visible-light and infrared LED along with photodiodes to determine heart rate. It works in tandem with your phone’s GPS and Wi-Fi to determine your location and other geographical information, thus it can track daily activities as well as workouts between its sensors and the capabilities connected by the iPhone. As far as aesthetics, the watches boast everything from a sapphire crystal face, to a stainless steel case, or even 18-karate gold casting in yellow or rose (if you are willing to pay in the $10,000–$17,000 price range).

Going forward, smartwatches are expected to be the leading wearables product category and take an increasing larger percentage of shipments—rising by 41% over the next five years to ultimately account for 59% of total wearable devices shipments in the holiday season of 2015 and on to just over 70% of shipments in 2019 (Business Insider, 2015). Today, the Apple Watch is responsible for truly kick starting the overall worth in the smartwatch market, already taking 40% of adoption in 2015 and is expected to reach a peak of 48% of the share in 2017 (Business Insider, 2015). And, with Google joining Apple in the smartwatch market, estimates are that these platforms will eventually make up over 90% of all wearables, with some distinctions between smartwatches and other devices, especially with fitness bands, such as FitBit, which is next on the list below. (www.apple.com/watch)

13.4.1.3. FitBit

At its core, FitBit is a physical activity tracker that tracks much of a person’s physical activity and integrates with software to provide personal analytics with the goal of helping health-conscious wearers to become more active, eat a more well-rounded diet, and sleep better. It is a sort of 21st century pedometer originally introduced in 2008 by Eric Friedman and James Park (Chandler, 2012). The device itself is only about two inches long and about half an inch wide, and can be easily clipped onto a pants pocket or snapped into a wristband. Like the sensors in the Apple Watch, the FitBit has a sensitive sensor that logs a range of data about activities to generate estimates on distance traveled, activity level, calories burned, etc. It also has an altimeter, designed to measure how much elevation is gained or lost during a day, which is an important contributor to physical activity metrics. The clip has a built in organic light-emitted diode (OLED) that scrolls current activity data, which alerts the wearer if they have not met daily fitness goal requirements via a little avatar that grows or shrinks depending on the wearer’s activity level. For additional gamification, the device displays “chatter” messages to encourage the wearer to keep moving. The data is offloaded to a wireless base station whenever the wearer passes within 15 feet of the base, and is uploaded to the accompanying software where it converts raw data into usable information through its proprietary algorithms.

FitBit and other wearable fitness devices have come under some scrutiny as to whether they actually work or not (there is a relatively high degree of error, though the FitBit itself has one of the lowest at only around 10%) (Prigg, 2014), yet they nevertheless are anticipated to continue catering to niche audiences due to their appeal to those interested in health and exercise. However, research suggests that FitBit and similar devices aimed only at fitness tracking (as opposed to, for example, smartwatches that include these in their lists of capabilities) will see their share of the wearable device market contract to a 20% share in 2019, down from 36% in 2015 (www.fitbit.com)

13.4.2. Wearables for him/her

The evolution of wearables does not stop at increased capabilities and customization (like what clips to add on your MagicBand or which metal band of Apple Watch to get). Luxury designers are getting in on the wearables market—like Swarovski, Montblanc, Rebecca Minkoff, Fossil, and Tory Burch, to name a few—often by partnering with device makers. These devices are becoming even more personal and designed to fit the customer. Within this is what I like to call the “genderfication” of wearables: narrowing the market to better segment and meet the unique needs of customer demographics. Here is a quick look at how these devices are being designed for him and for her.

13.4.2.1. Wearables for her

The fashion conscious techn-anista could benefit from wearables jewelry accessories, such as Ringly, a gemstone ring device that connects to your phone and sends customized notifications through a smartphone app (available currently for both iOS and Android devices) about incoming emails, texts, calendar alerts, and more through a choice of four vibration types and light. Rings are made from genuine gemstones and mounted in 18-karate matte gold plating. (www.ringly.com)

13.4.2.2. Wearables for him

Recently, designer clothing line Ralph Lauren has been sharpening its chops in the wearables apparels market, releasing its PoloTech™ shirt to the public. According to the site, silver fibers woven directly into the fabric read heart rate, breathing depth, and balance, as well as other key metrics, which are streamed to your device via a detachable, Bluetooth-enabled black box to offer live biometrics, adaptive workouts, and more. (www.ralphlauren.com)

13.4.3. Personal visual analytics

A discussion on wearables is a necessary predecessor in order to fully grasp the importance and possibilities of personal visual analytics (or, PVA). Data surrounds each and every one of us in our day lives, ranging from exercise logs, to records of our interactions with others on various social media platforms, to digitized genealogical data, and more. And thanks in part to things like wearable devices that track and record data from our lives we are becoming more and more familiar and comfortable with seeing and working with information that is intrinsically personal to us. With corresponding mobile apps that link directly to wearable-collected data, individuals have begun exploring how they can understand the data that affects them in their personal lives (Tory & Carpendale, 2015).

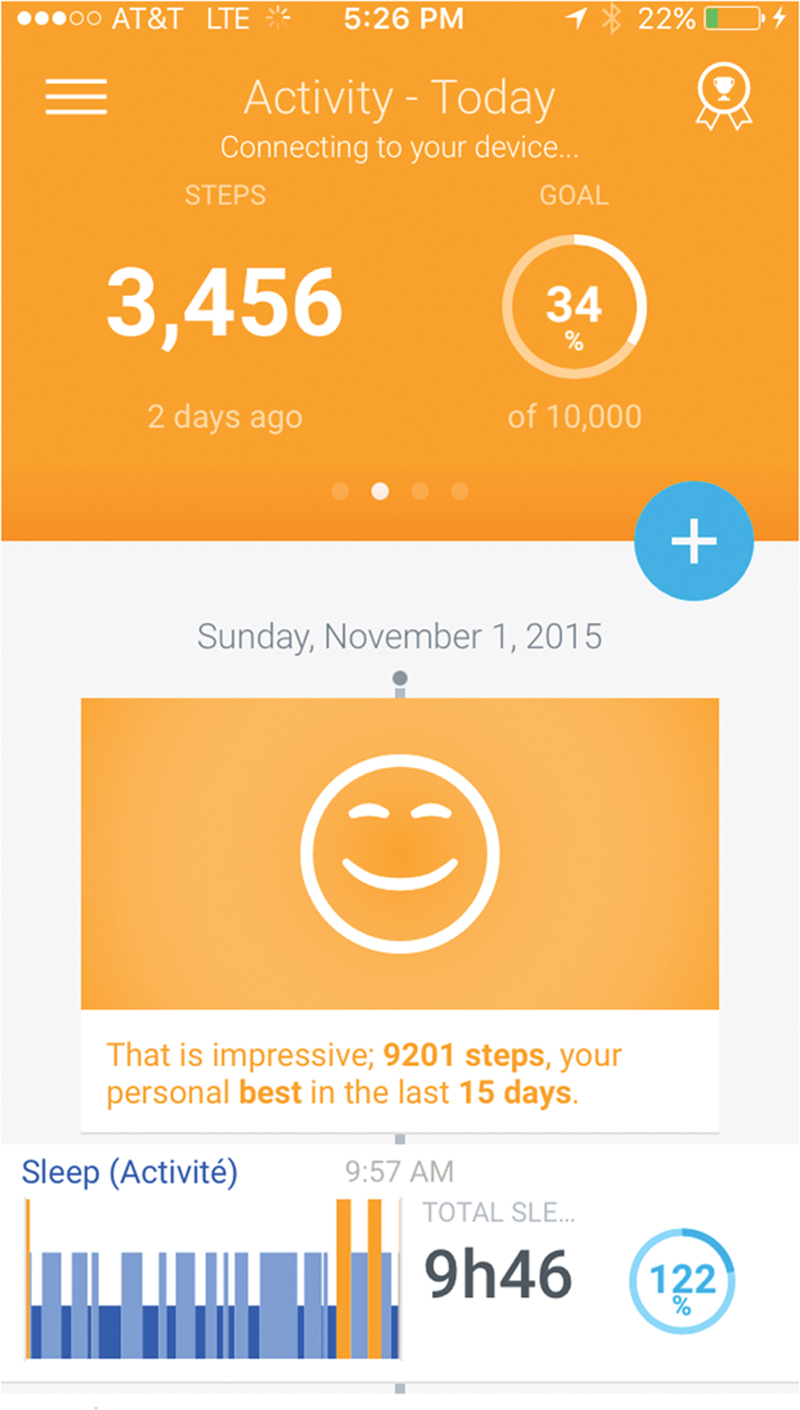

There is a Quantified Self movement to incorporate technology into data acquisition on various aspects of a person’s daily life in terms of outputs, states (moods, vital signs, etc.), and performance by comparing wearable sensors and wearable computing. Also known as life logging, the Quantified Self movement is focused on self-knowledge and self-tracking that is enabled by technology to improve daily functioning. This self-monitoring activity of recording personal behaviors, thoughts, or feelings is made exponentially more approachable and intuitive with visual analytics tools (Choe et al., 2014). In fact, there is an enormous potential for us to use our personal data and personal analytics in the same way as we might interact with any other data, and through the same types of visualizations and visual discovery processes. This is a concept referred to as PVA, the science of analytical reasoning facilitated by visual representations used within a personal context, thereby empowering individuals to make better use of their personal data that is relevant to their personal lives, interests, and needs (Tory & Carpendale, 2015). As an example, consider the image in Figure 13.5, which shows a snapshot of the visual dashboard of personal data corresponding to one smartwatch currently available in the market.

Figure 13.5 A Snapshot of Personal Visual Analytics, Taken From a Smartwatch Correspondent App

Of course, if designing visual analysis tools for business users who lack formal data analysis education is challenging, then designing tools to support the analysis of data in one’s nonprofessional life can only be compounded with additional research and design challenges. These go beyond supporting visualization and analysis of data in nonprofessional context, but also are constrained by other personal factors, like form factor preferences or resource budgets to acquire such devices. An emergent field today, PVA is an area currently undergoing a call to arms from researchers in the space. Many—perhaps most—believe that integrating techniques from a variety of areas (among these visualization, analytics, ubiquitous computing, human-computer interaction, and personal informatics) will eventually lead to more powerful, engaging, and useful interactive data experiences for everyone—not just formal data users (Huang et al., 2015).

13.5. Interaction for playful data visualization

PVA is one way that people are taking a more intimate interest in seeing and interacting with data on an individual level. And, while many users may not have a deep knowledge of how to navigate the analytics provided on their wearable app dashboards (or other personal visual analytics venues, including things like platforms for social analytics for various social web activities), they do have a high level of familiarity with the context, a prerequisite of any purposeful analytical endeavor. And, more important, because the data is personal they are compelled by the innate desire to play with their data to find answers to questions like—to use Figure 13.5 as food for thought—how many steps do I typically walk in a day? Or, what time of night to I get the best sleep? After all, play—a notoriously difficult concept to define—is important: it is associated with characteristics like creativity and imagination. And, in our ever-expanding data-driven culture, these are the traits which pave the road to curiosity—a requirement of an agile discovery mentality focused on exploring and uncovering new insights into diverse and dynamic data. However, while many might shy away from associating the word “play” with analytics, there is nonetheless a role for playfulness even in the more daunting of analytical tasks. Imagining a new visual orientation for data can then be followed by further, more serious, analytical approaches. For example, consider how an analyst will manipulate objects by sorting them into patterns, theorizing about meanings, exploring possibilities… Though these experimental activities may be seemingly unproductive (discovery), they are often among those most critical to iteratively finding meaningful combinations (insights) in a structured (or at least semi-structured) way. The dichotomy between play and analysis is especially apparent in playful visualizations—those that support and promote play (Medler & Magerko, 2011) and allow for interaction with information through visualizations.

Playfulness in analytics and with visualization is an approach as much as it is a mentality. At the 2015 International Institute of Analytics Chief Analytics Officer Summit, predictive analytics expert Jeffrey Ma gave the closing keynote. (You may remember Jeff as the member of the MIT Blackjack Team that was the inspiration for the book Bringing Down the House and later its Hollywood adaptation in the movie 21 which starred, among others, Kevin Spacey.) Ma is currently the Director of Business Insights at Twitter and a regular speaker about data and analytics at corporate events and conferences. In his closing keynote at the IIA CAO Summit, Ma discussed a handful of key principles of analytically minded organizations. One principle in particular was that these organizations embody intrinsic motivation and channel this motivation into the use of appropriate metrics to quantify their successes. Another of Ma’s principles was competition, and the need for company employees to compete as both teams and individuals—working for personal achievement and to push the organization as a whole toward a common goal—and how we can use visual techniques to foster this engagement. To the latter, essentially what Ma was speaking on was gamification, a subset of gaming techniques applied to information visualization that can be valuable for analytical insight.

While there are many properties that make up playful data visualization, among the most important is interaction, and this—how interaction delivers a rich visual experience that promotes intrinsic human behaviors and supports visual discovery through play—is the focus of the final section of this text.

13.5.1. Gamification and gameplay

When we think of visual, “playful” interaction with information, one concept that bubbles to the top is gamification and how it can be used as a paradigm of rewarding behaviors within a visual analytics system. However, it is important to note here the distinction between gamification and gameplay because, though it is probably the more recognizable of the two terms, gamification alone is only one piece of the overall architecture of truly playful visualizations that benefit from the gaming techniques. Gameplay, too, has important influencers in how it contributes to playful visualization and visual data discovery.

First, gamification generally refers to the application of typical elements of game playing (like point scoring, competition with others, rules of play) to other areas of activity, typically with the goal of encouraging engagement with a product or service. Applications of gamification include things like earning virtual badges or other trophies of interactions within a gaming environment that are awarded based on accomplishing milestones along a journey to proficiency. It is also often used as a recruitment tool in human resources environments—for instance, the US Army’s transportable “Virtual Army Experience” units are taken to recruiting environments to attract and informally test potential recruits—to motivation and goal tracking applications used everywhere from virtual training academies (see Treehouse.com) to engendering customer loyalty and rewards (see Recyclebank.com).

Gameplay, on the other hand, is a bit more ambiguous to define, but generally refers to the tactical aspects of a computer game, like its plot and the way it is played, and is distinct from its corresponding graphics and sound effects. It is commonly associated with video games and is the pattern (or patterns) defined through the game rules, the connection between different player types and the game, and game-related challenges and how they are overcome. While the principles of information visualization can inform the design of game-related visual analytic systems (like monitoring player performance over time), gameplay practices themselves are also being used to offer a unique perspective on interactive analytics, too, and how video game data can be visualized. This was a used case presented by researchers Medler and Magerko and the focus of a 2011 paper in information mapping (Medler & Magerko, 2011).

13.5.2. Interactivity

Gamification, gameplay, and playful data visualization are not synonymous (or even close to being synonymous for that matter); however, the undercurrent of interactivity is a mutual enabler of them all, and reinforces our key emphasis within these discussions.

At the core of any type of data visualization tends to appear two main components: representation—how the data is represented through visual cues and graphicacy techniques—and interaction. This interaction is a part of a visualization’s overall visual dialog (introduced in chapter: Visual Communication and Literacy, which refers to the exchange of information—or, dialog—between the designer of visual, the visual itself, and its recipient). Unfortunately, aside from things like drill-down or expand activities, or animation and streaming conversations, interactivity is often deemed secondary to representation. And, while static images offer expressive value, their usefulness is limited by design. In contrast, interactive data visualization can be used as stimuli to prompt insight and inspire creativity.

Depending on the users’ intent, there are several different categories of interaction in data visualization that have been articulated within the literature. These are:

Select: to mark something as interesting for deeper exploration and/or analysis

Explore: to actively engage in investigative behaviors with the visual

Reconfigure: to arrange the data or the visual differently

Encode: to provide a different illustration of the data

Abstract (or elaborate): to show more or less detail

Filter: to show something conditionally with the removal of certain aspects

Connect: to show related items and explore new correlations (Yi et al., 2007)

As a related aside, it is worth to remark that many—if not all—of these categories of interaction are those most capitalized on by the gesture-based methodology of mobile-first visual discovery applications, such as those provided by Roambi or Tableau’s new app, Vizable.

Ultimately, interactivity supports visual thinking which drives visual discovery. Without interactivity, visual discovery falls short of its intended purpose, yet with the right interactivity, data visualization becomes a natural extension of the analyst’s thought process. Interactivity, then, is the element that allows analysts to “play” with data: to manipulate information into patterns, theorize about meanings, project interpretations, explore possibilities—all while balancing the fixed content, context, and relationships of the data with creativity and imagination. Playful visualizations are where the dichotomy of discovery—or, play—and analysis disappears (Boxes 13.4, 13.5, and 13.6).

This book begins and ends with a bit of a personal touch: from the larger picture of how we—as consumers—are affected by the shift of data-centric companies to a progressively visual culture of data discovery, to how we—as individuals—can contribute to that discovery and participate as part of a more holistic visual data culture. In effect, we all are part of the ongoing visual imperative to see and understand data more clearly, and to interact with this information in a way that makes the most sense: visually. From top to bottom, from the most data-driven organizations that are leading every niche of industry, disrupting, transforming, and reinventing the way we do business, to the most personal analytics captured and reported through commonplace wearable devices, the ability to visually understand complex information through curated data visualization is making analytics more approachable, more insightful, and more valuable.

So as this text draws to a close, I will leave you with this—a call to action. Be aware of the visual imperative and incorporate the tools, tips, techniques that we have reviewed and discussed in this book within your work and personal lives to better understand the world around you and affect positive change. And, go beyond awareness and find new opportunities and opportunities to engage, too. Be a leader by fostering and nourishing a culture of visual data discovery in your organization. It is of the utmost importance now, and will continue to play an even larger and more critical role in the future.