I’ve just hypothesized that moral origins began with the appearance of a self-regulating conscience, but this would only have started the process of moral evolution. Once we had something like a conscience, this opened the way for a very different type of social selection, one that affected our capacity as moral beings in a sphere very different from self-control. To understand its power, we must look, again, to Darwin.

When Charles Darwin came up with sexual selection theory, he considered this to be a special type of selection process, guided by the mating choices of females, that could support otherwise very costly maladaptive traits. Human altruism can also be viewed as a maladaptive trait; it is similarly kept in place because patterns of decisionmaking compensate the altruists and enable the trait to be selected.

We’ve already met with the idea of indirect reciprocity, which was first introduced by Richard D. Alexander in 1979.1 Alexander had taken note of two ethnographic patterns. One was that human foragers’ band-level cooperation was long term, not short term. The other was that these people weren’t acting as careful bean counters when it came to being generous to others who were in need, which ruled out anything like reciprocal altruism. Indeed, even though the most intensive aid was reserved for close kin, just as Trivers said,2 these foragers were also prone to help nonrelatives, and they did so substantially in the absence of any social contract that bound their unrelated beneficiaries to pay them back in kind. This fits our definition of altruism. According to Alexander, whoever had the means to help nonkin did so without very carefully adding up any past history of giving or taking, knowing that in the future whoever then happened to be in a position to give help would also do so.

This brings us again to the Golden Rule, which seems to be expounded in all human cultures be they recent and complex or ancient and “Paleolithic.” Some form of this prosocial dictum is found in the ideology of every institutionalized religion,3 and as a generalization it has found its way into certain formal philosophies of ethics, as with Kant.4 The essence of this dictum seems to combine elements of altruism and personal self-interest because in part it’s a way to convince others to behave more generously.5 Practically speaking, this rule also might be seen as an implicit invitation for free riders to “take advantage,” but it’s a universal idea, nonetheless, and universal ideas are likely to be there because at some level natural selection, combined with persistent aspects of human cultural lifestyles, has favored them in shaping our species prehistorically.

Even though most people are quite unlikely to have read Kant, they intuitively appreciate the Golden Rule. Alexander recounts a conversation he overheard in which truckers were discussing stopping to give aid to colleagues who had trouble on the road.6 The idea the truckers articulated was that you help me when I’m in need, and I’ll help someone else when he’s in need, and he’ll help still another. Thus, you’re contributing to an ongoing system that sees to it that people get help when they need it—but the payback is merely probabilistic. Essentially, you have to trust the overall system to work.

Alexander’s overheard conversation jibes with the dinner-table and drinking practices of Montenegrin truck drivers in the former Yugoslavia when I was doing research there in the mid-1960s. At a local truck stop and inn, I used to watch over-the-road Montenegrin šofirs (chauffeurs) as they enjoyed hearty peasant meals supplemented with liberal shots of plum brandy. They’d be sitting at large tables of six to eight people, and when it was time to pay, every last Serb always got out his wallet with a small flourish—with the certain knowledge that one person would be paying for all. I’d be holding my breath, but each time, by some subtle dynamic, the ritualized decision was made. When I followed up with an ethnographic query in other quarters, I was told that this was an ingrained custom; indeed, these tribal Serbs considered northern European tourists, who they’d seen dividing up the tabs when they dined together, to be hideously “selfish.” Their informal philosophy seemed to be “what goes around, comes around,” a philosophy that Americans sometimes apply—and sometimes don’t—when it’s time to pay for dinner with friends.

The isolated mountain tribe where I was doing two years’ field research at the time was almost five hours by foot or horseback from the main highway, with neither electricity nor running water, let alone a wheeled vehicle or a restaurant.7 And there I discovered that this truck drivers’ ritual had ancient roots. When people were gathering in social groups, it was always just one man who passed around his bag of contraband tobacco so that each person could empty out enough for one cigarette into his newsprint “rolling paper.” As with the truckers, the donations were made in a spontaneous fashion with no hint of repayment, except for the assumption that next time someone in a position to do so would surely be coming forward because that was the custom.

To me as a foreign observer, this ritualistic act of tobacco-sharing always seemed to be deeply enjoyable to the parties involved, and in the tribe a similarly prosocial pattern of indirect reciprocity also was followed in several more practical and economically important areas. These mountain Serbs were pastoralists, and their modest flocks of sheep were subject to two types of catastrophe. One was from wolves, who for reasons known mainly to wolves sometimes enter a corral at night and then go on killing sprees that end with the annihilation of the entire herd. The other was lightning, which can easily take out a clustered herd up on the treeless mountain pastures used all summer. When either of these rare calamities took place, up to thirty or more households would each donate a sheep to the unfortunate, who was thereby made fortunate again because his herd was restored.

My entire tribe of just over 1,800 souls was made up of somewhere around 300 households and just over 50 different clans, so these donations were coming partly from close blood kin but mostly from people who were unrelated—neighbors or godfathers or in-laws from other settlements. This meant that much of the generosity had to be extrafamilial and therefore altruistic. These local tribal networks are sized similarly to small foraging bands, whose “insurance” systems follow similar principles of sharing, and cooperation with nonkin as well as kin.

In fact, these continuing practices of traditional Serbian pastoralists—and of modernizing Serbian truck drivers—may have evolved culturally from similar customs in much earlier times, when these people were nomadic foragers who shared their large game. However, it’s equally likely that they were invented later, simply because humans are inclined to come up with systems based on indirect reciprocity whenever they need “insurance” against bad luck. Meat-sharing is just one in a long line of mutual-aid inventions of humans in groups, and one way to keep the system working is to remind others to do their part when it is time to reciprocate.

Another tribal instance of indirect reciprocity that involved nonkin arose in the form of a moba, which was called when a Montenegrin family was building a house and for some legitimate reason found itself short-handed, or when it had too much hay to safely harvest before rain came. The moba was a volunteer work group, and again a mix of relatives and nonrelatives did the giving. Again, the social network from which the volunteers were drawn would be about the same size as a twenty-to-thirty-person hunting band, and in the case I observed of house building, the moba spanned two days and involved almost two dozen helpers. The host family put on a big feed each day, but the donated labor amounted to far more than the value of the cheese, bread, meat, milk, tobacco, and plum brandy supplied by the hosts, and fewer than half of the helpers were blood kin. I emphasize that precise individual repayment in kind was not envisioned, even though in general future help was anticipated as a response to future special need. As with the response to herds getting wiped out, this fits perfectly with Alexander’s description of indirect reciprocity in hunting bands.

I must add that there was a palpable air of good feeling during a moba. The helpers appeared to be happy in their generous role, and there was an atmosphere of jolly camaraderie as people working together joked, drank their host’s plum brandy, and ate as one big group there to help. And as with hunter-gatherers’ indirect reciprocity, these various services were provided without any thought of carefully counting the immediate beans: you helped out others in need because you could, and in general you expected them to help you in your hour of need. That ideology supported a system that served people’s special shortfall problems, and they trusted the system to work.

The analogy to modern insurance systems may be striking, but with these indigenous systems of indirect reciprocity there were no fixed payments: the donations were basically voluntary even though social reputations were at stake. Furthermore, it was a face-to-face social community, rather than an impersonal insurance company acting on advice from actuaries, that decided who was eligible. Even though I participated in only two mobas, it was clear from the way people talked about this practice that the selo (the village, in Serbian) would know if, by custom, someone was genuinely qualified as a recipient. In my particular Montenegrin tribe, the “village” was actually a widely scattered localized settlement, but it was clear what people meant. They were speaking about the gossiping kind of morally based “collective consciousness” that Durkheim characterized so aptly,8 and I can guarantee that if someone tried to get help when this was inappropriate, tongues would wag, social reputations would suffer, and some or all of the people in the hoped-for network might well fail to participate.

The same sense of what is appropriate goes for hunter-gatherers; when a vigorous and dedicated hunter is injured, there’s little doubt that the rest of the band will help him and his family because his need is all too apparent—and the help will be all the more generous because this productive citizen obviously isn’t trying to take a free ride. This is well understood by everyone, as is the fact that helping him to recover will be useful because there’ll be more meat for everyone. In the case of a conspicuously lazy man, he’ll be seen as a freeloader and the band is likely to help much less. By the same token, a generous person will be helped more in an hour of need than one who is stingy.9 But the basic system applies to anyone with a decent social standing.

Thus, because of what might be called “macro bean-counting,” in which general past patterns are taken into account and factored into a system of indirect reciprocity, such systems, even though somewhat vulnerable to free riders who are moderately lazy, are resistant to really flagrant opportunism because people won’t put up with it. However, there remains the ultimate evolutionary question of how such “unbalanced” systems can stay in existence. The models tell us that the altruists who are helping nonkin more than they are receiving help must be “compensated” in some way, or else they—meaning their genes—will go out of business. What we can be sure of is that somehow natural selection has managed to work its way around these problems, for surely humans have been sharing meat and otherwise helping others in an unbalanced fashion for at least 45,000 years.

As Frans de Waal argues so eloquently, empathy is an important and too often underestimated element in the social mix that makes us human.10 I’ve been using Darwin’s term—sympathy—because it is less technical, but to me such feelings, which include an appreciation of how others are feeling and what their needs are, become apparent in descriptions of the pleasure hunter-gatherers take in sharing meat, even though sometimes there’s some simultaneous grousing about the appropriateness of the shares. Similarly, the pleasure that Montenegrin Serbs took in helping out their neighbors was obvious enough, even though some of the moba participants surely were thinking some about their undone work at home. More generally, I believe that humans are innately prone to respond positively to engaging in helpful cooperation—as long as they feel a social bond with those they are helping, as long as the costs aren’t too high, and as long as they feel that, long term, the system will be insuring them against really bad luck.

Altruism, sympathy, and empathy aside, I believe that nonliterate foragers in their bands also have good intuitive understandings of their systems of indirect reciprocity and how they work. My overall impression is that even though these systems seem to be free of any compulsive long-term bean-counting, in the distribution of large game some specific types of reckoning do occur, in several special contexts. For instance, larger families are routinely given larger shares because their needs are greater, and, as we’ve seen, when generously participating individuals fall on temporary hard times (be this through injuries such as broken bones or snakebite, or illness), reasonable adjustments will be made for them even though generally their close kin will be the primary source of aid. In addition, rather often the hunter who made the kill gets a somewhat larger share,11 perhaps as an incentive to keep him at this arduous task.

Although hunter-gatherer generosity is sometimes depicted as being all but boundless, the generous feelings that help to motivate band-level systems of indirect reciprocity in response to individual needs are not without limits, and the same is true within families. For instance, considerable bean-counting takes place with respect to the tradeoffs that attend supporting the elderly. Old people may at times be quite useful, in providing wisdom or helping with childcare, but at other times they become a serious liability to the immediate family members who primarily support them. Hunter-gatherers set limits as to how much they’ll invest in family members who are becoming so infirm they can no longer walk effectively, as this is a serious problem for nomads who must carry small children and needed paraphernalia with them when they frequently change campsites. Most readers will be familiar with Inuit family practices of putting old people out on the ice and letting them painlessly freeze to death,12 and the logistics are obvious enough. An adult who cannot keep up will be a substantial or impossible burden trekking across snow and ice, and when it’s time for triage, everyone in the band understands the situation, which is faced with sorrow.

I remember very well asking Kim Hill, an anthropologist who has spent years in the field working with South American nomadic foragers, about whether such practices also exist in tropical situations. He said they do, but in this case what happens is that someone will come quietly up behind them with a stone axe and all but painlessly “brain” them. My obvious shock faded when he added that if they were left alive, to “die peacefully” Eskimo-style, predators might eat them alive—while scavenging birds would first go for their eyes. They preferred a quick death and sometimes chose to suffocate by being buried alive.

Here’s a final note on altruism and its limits that comes, again, from my own fieldwork with a modernizing “tribal” people who still basically had a subsistence economy. In my highland Serbian tribe one day an eighty-year-old woman I’d never seen before passed the front of my house walking quite briskly, complaining to herself out loud as she propelled herself along with two stout canes. I was told she’d been left with no kin at all (nema nikoga, “she has no one”) and that she had to walk from one house to the next every single day because, although by (altruistic) custom people felt obliged to give her food and a night’s lodging when she showed up, no one was willing to let her stay a second night for fear she’d become their dependent. Thus, under certain conditions the quality of mercy outside the family can be strained and strained severely—even as a system of indirect reciprocity in fact is working.

At the same time, however, people who are embedded in these systems believe in taking care of each other as long as this makes sense by the rules they’ve invented. And the care foragers take of others seems to be nicely geared to the mechanical power of the three basic selection forces we’ve been discussing, as these favor, respectively, egoism, nepotism, and, at the end of the line but still very important, altruism. Charity may begin at home, but in a weaker form it extends to others in the group. And sometimes, as with modern blood banks, it can even be extended to total strangers.

In 1987 Alexander was considering two theories to explain the altruism inherent in human systems of indirect reciprocity. We’ve already considered his views on prehistoric group selection, and we’ve also touched upon what in his mind seemed to be the more useful theory—social selection of the type that has been called “selection by reputation.”13 Such selection includes mating advantages and much more, and this selection-by-reputation approach of Alexander’s has stimulated some considerable further research, even though many biologists have remained enamored with reciprocal-altruism or, more recently, the one-shot, mutual-benefit models that were discussed in Chapter 3.

Alexander’s original main premise was that a reputation for being altruistically generous might bring fitness benefits that could compensate the costs of such generosity if, when parents or individuals were making marriage choices, they were prone to favor “prospectives” who had a social track record of being unusually generous. For instance, a socially attractive, generous male may be more quickly accepted as a marriage partner, and then this prime early marriage gives him a fitness advantage compared to other males who have to marry later and not nearly as well. If this reputational benefit outweighs the costs of the generous behaviors that made for the superior reputation, such generosity can bring a net fitness benefit to the altruist and the altruism is nicely explained in terms of natural selection.

Alexander’s insights about social selection in humans helped to stimulate “costly signaling” theory,14 which can apply to any species that has bisexual reproduction leading to mate choice. Other animals obviously don’t gossip about reputations, but sometimes in their mating patterns they may be genetically evolved to favor individuals who give off costly signals that correlate with being of high genetic quality as mates. If the male’s reproductive gains (namely, being chosen) exceed the reproductive costs (paying for the otherwise maladaptive signal), such signaling can be a significant aid to fitness for both choosers and the chosen.15

The idea is that the cost of an unfakable signal of high quality, which again might involve unusually vigorous peacocks growing otherwise maladaptively outsized spotted tails, or a human hunter’s putting more effort into hunting and providing more meat for others, will be compensated as such worthy individuals gain preference as mates—which of course strongly improves their reproductive success. And as we’ve seen, the females who are better evolved to choose them will also be coming out ahead because the attractively colorful (or productively generous) males they prefer will be unusually fit, which helps the females’ fitness. Because there’s an escalating interaction between the evolving, discernible signs of quality and the evolving preferences of females who do the choosing, this provides the possibility of the “runaway” selection process that was touched upon earlier.

Although runaway selection has been difficult to model mathematically, in theory the selection process involved could become quite powerful—particularly if natural selection is making other adjustments that are useful to fitness. For instance, a prime and unusually fit male peacock’s huge tail is obviously a liability in terms of predator evasion, and in reducing such risks, these big tails have evolved to reach their zenith during mating season but shrink for the rest of the year.16

With such costly signaling, the potential problem of free riders remains. If signals indicating high quality as a breeding partner somehow can be faked by others who in fact lack the desirable but maladaptive traits, then the genuine costly traits will not be able to evolve because these free riders will be out in front. Thus, if a genetically inferior peacock could readily grow a tail as resplendent as a highly fit peacock, this sexual type of social selection wouldn’t work, and the entire pattern of having camouflage-friendly drab peahens choosing the best decorated, colorful (and most fit) males wouldn’t exist; both sexes would be drab, with coloration devoted entirely to camouflage.

The same is true of empathetic altruism in humans. If such generosity could be readily faked, then selection by altruistic reputation simply wouldn’t work. However, in an intimate band of thirty that is constantly gossiping, it’s difficult to fake anything. Some people may try, but few are likely to succeed.

Even though Alexander’s assumptions about selection by reputation seem correct, for ethnographic examples in 1987 he was obliged to rely on just a few prominent studies of foragers like the Bushmen,17 for broader surveys of the type that archaeologists Lawrence Keeley and Robert Kelly18 began making in 1988 and 1995 were then a thing of the future. Fortunately, anthropologists like Frank Marlowe and Kim Hill are now working with really sizable general evolutionary databases for hunter-gatherers, and their analyses are helping scholars in other fields to consider the facts on a less “anecdotal” basis.19

The substantial, highly specialized hunter-gatherer database I am developing at the Goodall Research Center at the University of Southern California focuses just on social behavior of LPA foragers. When this systematic research on hunter-gatherer social behavior began over ten years ago, with substantial outside assistance from the John Templeton Foundation, the idea was to look for diversities and universals in moral behavior, conflict, and conflict resolution. The long-term objective was to categorize or “code” the social behaviors that were most relevant to evolutionary analyses of social ideology, social control, cooperation, and conflict so that interesting extant patterns might be discerned statistically and better prehistoric hypotheses developed.

Because we’ll be examining these data in some detail, the coding system I developed needs some further explanation. For the past six years my research assistant has had memorized a five-page list of 232 varied and highly specific social coding categories, which range from “group member selected to assassinate culprit” to “sharing with kin” to “aid to nonrelatives favored.” She patiently goes through thousands of pages of hunter-gatherer field reports to identify descriptive paragraphs that are relevant to each of these 232 coding categories, and then she summarizes each chunk of data individually.

Eventually, I hope that a searchable database can be made public to put all of this organized data at the electronic fingertips of scholars interested in social evolution, but this will require a large investment and for some time to come I will be obliged to analyze the data by hand, which is time consuming even though, for 50 out of a total of over 150 LPA societies, this vast information is now at least coded and summarized. If this coding weren’t done, the time needed to ask and answer precise questions of such a huge amount of data would be quite prohibitive, and the treatment we’re about to meet with would have been impracticable.

A few years ago, inspired by both the late Donald T. Campbell’s psychological interest in altruism and prosocial preaching and Richard D. Alexander’s biological thoughts on selection by reputation,20 I decided it would be useful to investigate quantitatively the extent to which hunter-gatherers approve of generosity, especially extrafamilial generosity. The result has been that ten of the fifty LPA societies in this ever-growing coded sample have been used for intensive analysis here. These groups represent major world geographic regions and favor well-described hunter-gatherers who were relatively little affected by cultural contact before being studied. The idea was to see whether these “preaching” behaviors were widely mentioned for LPA foragers, and it turns out that both intrafamilial and extrafamilial generosity are unambiguously espoused by all ten groups.

This unanimity is of great interest. When Don Campbell and I taught a graduate seminar together at Northwestern in 1974, we discovered that among all six early civilizations, starting with Mesopotamia and Egypt, “official” preaching in favor of altruistic generosity was predictable and universal.21 If hunter-gatherers did the same, and did so universally, then this would be a likely candidate for being a human universal, which would suggest, in turn, that such preaching was closely tied to human nature—and that it might be important to evolutionary analyses.

This recent analysis of ten foraging societies shows that generosity to nonkin is regularly mentioned indigenously as something that people in the band should practice, and there was no rocket science involved in assessing the coded materials. There are five coding categories that relate to generosity, and what was done, using whatever field reports existed for each society (there were between one and fourteen), was simply to count how many times people’s being in favor of such generosity was mentioned by ethnographers who lived with and studied these bands. The very strong patterns seen in Table II (next page) are typical of today’s LPA hunter-gatherers, so they can be projected backward in time for at least 45,000 years.

All ten societies had at least one such mention of extrafamilial generosity’s being favored, but before we consider these numbers, we must keep in mind that many societies had only a few sources in the form of field reports; that for some societies, such as the Kalahari !Ko, multiple reports were published by the same ethnographer; and that some ethnographers are far more prone to focus on indigenous social attitudes than are others. Thus, the unanimity uncovered here is quite remarkable.

We see, for instance, that the Netsilik in central northern Canada had twenty-six mentions in favor of extrafamilial generosity in eight ethnographies, whereas the Yahgan at the tip of South America had one mention in only three ethnographies. Given that in spite of inconsistent ethnographic coverage these prosocial preachings are unanimous, even a sample of ten out of fifty coded societies provides a firm basis for suggesting that today and yesterday altruism has been, and was, actively promoted—and amplified—among mobile, egalitarian hunter-gatherers everywhere. It’s also of interest that these “golden rule” preachings and statements are found not only in peaceful foraging societies, but also in highly warlike ones like the Andaman Islanders in Asia. Clearly, the roots of the preachings are ancient, and the central tendency is very strong, indeed.

TABLE II ACTIVE FAVORING OF EXTRAFAMILIAL GENEROSITY*

*This table was adapted from Boehm 2008b.

It’s worth emphasizing that giving nepotistic aid to kin also was favored unanimously as an ode to family values. But what’s most important, here, is that aid to nonkin was explicitly advocated as a behavior that group members collectively favored and expected of individuals. Surely, such manipulative preaching was done for a practical purpose that we’ve met with already: it was to behaviorally amplify the sympathetically generous tendencies of group members.22 The larger purpose was to improve the overall quality of a social and economic lifestyle that depended very heavily on cooperative indirect reciprocity.

The remaining items in this table, also unanimously subscribed to, demonstrate even more broadly that there’s a predictable human concern with generosity because this is essential to cooperation and sharing. Thus, this social amplification of altruism would seem to be deliberate, well-focused, and probably universal.23 Hunter-gatherers appreciate both cooperation and social harmony, and they understand that the general promotion of generosity will serve both of these causes.

We must look more deeply now into systems of indirect reciprocity to see exactly how altruists can be transformed genetically from losers into winners. In The Biology of Moral Systems, Alexander sees several ways that generous acts can be rewarded so that an altruist can be gaining more than is lost.24 First, he mentions outstanding altruists being formally rewarded, as when a modern war hero receives a Congressional Medal of Honor. As long as the award is not posthumous, this individual is likely to reap direct social benefits that will provide fitness advantages that may offset his risks. In a foraging band there are no governments giving out awards, of course, but a parallel might involve a well-appreciated man or woman who at personal hazard has saved another band member from a predator or snake, or perhaps a well-respected chosen group leader where this responsible role exists. In the case of a group leader, there may be some modest costs of energy or time, or some risks in trying to manage conflict, but there also are likely to be gains from having an enhanced reputation.

Alexander proposes a second kind of popularity contest, in which individuals showing generosity in everyday life are favored as future associates in cooperation. This is the main basis for the selection by reputation we’ve been talking about, and it includes not only marrying to good advantage but also making other beneficial personal alliances, be they social, economic, or political. Thus, individuals with a track record of contributing generously in everyday life can be more attractive as future collaborators in a variety of partnership contexts, which means the resulting fitness advantages could be repaying what these altruists have lost by behaving so generously in the first place.

There’s a third potential payoff for altruists. To the extent that these acts of generosity help one local group to flourish in competition with other local groups, Alexander seems to follow Darwin in thinking that altruistic genes might become better represented in future gene pools simply because groups with more altruists will prosper and grow in competition with other, less altruistic groups. The way he expresses this is that the altruists’ coresident altruistic relatives and all their altruistic descendants will profit because they are part of a group that can grow faster than other groups,25 and the wording suggests that he has both a kin selection and a group selection model in mind. But because the bands he is considering are now known to contain mostly unrelated families,26 the group selection model may be more appropriate.

Alexander’s first two paths to altruism are based on individual preferences that lead to selection by reputation, whereas ultimately the last is based on how groups compete as units. All are subject to the free-rider problem because a “hero” could lie about his exploits or a selfish person could try to fake being altruistic and might be chosen preferentially by a potential spouse, and in this way either of them might reap rewards that boost personal relative fitness and make it possible for these free riders to outcompete the altruists. Any substantial degree of cheating can undermine either social selection or group selection and thereby make altruistic traits individually maladaptive. But fortunately, there appears to have been an effective and rather distinctively human cure for this free-rider problem.

In evolutionary science, working hypotheses lie somewhere in between “educated guesses” that are made on a relatively shoot-from-the-hip basis and well-controlled laboratory experiments, such as those (in physics) that demonstrated the speed of light. In Chapter 4 my strong working hypothesis was that as they became culturally modern, the members of LPA foraging bands were keeping careful watch on other members as they gossiped confidentially to keep intimates informed about who was behaving well or badly, and that they could eventually arrive at a group consensus on this basis—and act on it to punish an identified deviant.

As today, these band members had both the social insight to identify and even anticipate problems that threatened the welfare of everyone in the band, and the ability to deal with them directly and decisively before the good guys were individually taken advantage of—and before their cooperating bands were torn to shreds by conflicts started by the bad guys’ behavior. For instance, if powerful deviants who tried to gain unfair shares of large game seriously threatened a customary system of meat acquisition and sharing, which was vitally useful to all group members, the band’s response could be still more dire than the Mbuti Pygmies’ obviously very angry reaction against Cephu, the arrogant meat-cheater who in effect stole from his group. Because bullying also is likely to stir stressful and disruptive conflict, group reactions to this forceful type of free riding would have been very well motivated, indeed.

Prehistorically, as culturally modern hunter-gatherers, people’s goal would have been to protect themselves from the worst opportunists. As humans who like us generalized extremely well, these foragers surely understood two things. One was that over the long run predatory patterns of social deviance potentially threatened everybody, not just the current victim. The other was that there was security in numbers if they wished to use collective sanctions in coping with the problem. What they didn’t understand, and I emphasize this to make it clear that I am not reading enlightened and deliberate “purpose” into basic selection mechanisms, was that when such communal moralistic aggression was consistently and harshly targeted against the same types of deviants over thousands of generations, this would have a significant impact on gene pools.

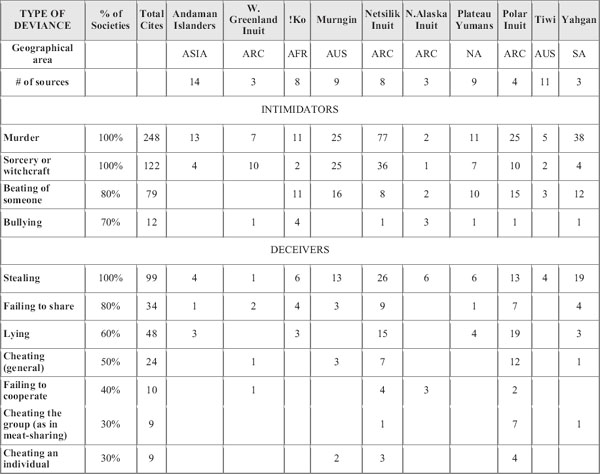

TABLE III SOCIAL PREDATORS*

*The above figures are derived from the author’s hunter-gather database.

Table III follows the (often overlapping) coding categories I use in my research to show, in descending order of frequency, some of the main types of punishable social predation mentioned for this same sample of ten LPA societies. Exploitation through dominant intimidation was statistically prominent, and it could be accomplished physically through murder or through administration of a beating, through the use of malicious sorcery, and through other forms of bullying. Exploitation through deception could be accomplished by failure to share and failure to cooperate, as well as by active thieving or lying or by deliberate cheating in several contexts. For a person disposed to social predation, a rich array of free-riding choices existed.

However, for humans the biological theorist’s conception of intimidating or deceptive free riders automatically coming out way ahead of innately gullible and all but pathetically vulnerable altruists does not play out that way, for very often these opportunists can be readily identified by their altruistic peers and punished (with genetic consequences) in a truly wide variety of ways (see Table IV, next page). Thus, we must ask whether traits that make for seriously antisocial free riding—free riding that invites severe punishment—may often be far more costly to the would-be free riders than are the costs of being generous for the altruists they are genetically competing with. If so, for humans alone we have a possibly definitive solution for the genetic free-rider problem.

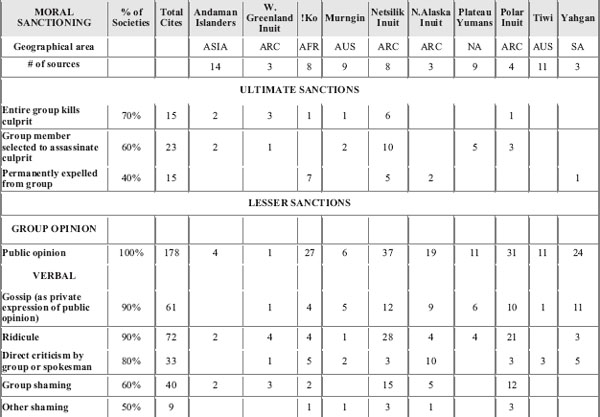

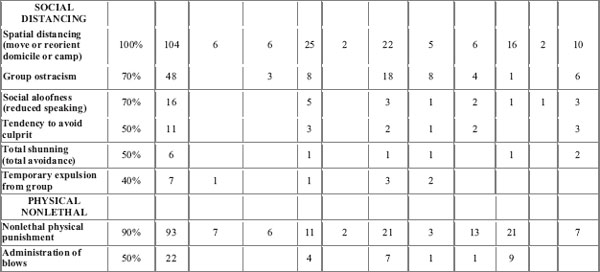

Table IV shows coded data for the same ten forager groups with respect to the sanctions employed, and again some of the coding categories overlap. Some types of sanctioning are underreported, especially because there is indigenous reticence about using capital punishment, but also because ethnographic reporting by its nature is spotty. Thus, with further information the apparent central tendencies represented by these findings would be still more robust; most likely, the majority of these social measures are either very widespread or universal among LPA foragers, so the central tendencies are pronounced.

All these sanctions contribute to punitive social selection, which takes place when entire groups develop strong negative preferences toward antisocial free riders—and act on these biases. The table shows that the system of punishment is quite flexible in its possibilities. Public opinion, facilitated by gossiping, always guides the band’s decision process, and fear of gossip all by itself serves as a preemptive social deterrent because most people are so sensitive about their reputations.

TABLE IV METHODS OF SOCIAL SUPPRESSION*

*The above figures are derived from the author’s hunter-gather database.

Every one of the social control mechanisms seen in this table is mentioned in one superb ethnography by Asen Balikci,27 who lived with and wrote about the Netsilik of central Canada, and also relied upon earlier data, collected right at the time of contact, when people were not yet reticent about their indigenous practice of capital punishment. The majority of these social control types were mentioned for over half of the LPA societies sampled, and the most prominent were social distancing, ridicule and shaming, expulsion from the group, physical punishment, and capital punishment. Thus, we may reconstruct yesterday’s hunter-gatherers as being well equipped to identify free riders, suppress their behavior (as with Cephu), and, if these foragers couldn’t intimidate the free riders enough to keep them under reasonably good control, get rid of them.

Obviously, severe social punishment can heavily damage the genetic interests of deviants who would controversially put their own personal prerogatives ahead of group interests. However, even after thousands of generations of such punishment, there obviously are still some rather strong innate tendencies to take free rides, as indicated so eloquently in Table III and also by the hunter-gatherer capital punishment statistics we examined at the end of Chapter 4. If group punishment has been so damaging to free riders for thousands of generations, we certainly must ask how the genes they carry have managed to persist so strongly in our human gene pools.

The answer is unobvious but simple: to the extent that many potential free riders take note of such punishment, and use their consciences to restrain themselves and stay out of trouble, this keeps them alive and well because in effect they have been “defanged”— and therefore are not targets of social control even though by genetic metaphor their poison sacs remain intact.28 The implications for the selection of altruistic traits are profound, for if free riders usually don’t dare to express their predatory tendencies, their enormous competitive advantage over altruists largely goes away. And this means that as long as the altruists are being compensated by reputational benefits, the playing field can be close to level. Indeed, given that the more serious free riders may lose far more than they gain because of punishment, the field may be much better than leveled.

If harshly punitive social selection effectively intimidates most would-be free riders, conscience functions also slow down these deviants because values and rules they have internalized enable them to anticipate shame and loss of reputation. For mathematical modelers this means that behaviorally little-expressed free-rider genes can remain statistically salient in human gene pools—at the same time that the genes of altruists can also remain numerous as long as the altruists are somehow being compensated. Williams’s well-respected models do not really account for this peculiarly human outcome.

In future research on humans, I believe this phenotypic suppression of free-riding behavior is something that any theorist trying to resolve the paradox of altruism must reckon with. Of course, I realize that Williams’s elegant and aggressively promulgated models have captured many hearts and minds, and that there’s a beautiful logic in straightforwardly equating free-riding tendencies (genotype) with actual free-riding behavior (phenotype). But people in small bands are so good at discouraging free riders at the level of phenotype that some major rethinking is in order about what is likely to be taking place at the level of genotype.

Social behaviors like capital punishment, banishment, ostracism, and avoidance as a partner in cooperation clearly have helped in significantly suppressing the frequencies of genes that favor predatory bullying or cheating, and over time this autodomestication surely has somewhat reduced and modified our innate potential for both types of predatory free riding.29 However, in terms of explaining altruism, I believe that the still more important effect has been to frighten potential free riders so much that they’ll desist from their depredations—even though their predatory inclinations are retained and passed on to offspring.

Add this all up, and what we have is a system of social control that can drastically reduce the genetic fitness of more driven free riders whose consciences can’t keep these dangerous traits under control, but that allows the more “moderate,” would-be free riders to control themselves in matters that would otherwise bring punishment and still express their competitive tendencies in ways that are socially acceptable. It’s for this reason that free riders haven’t just gone away, and this is reflected strongly in the tables. In fact, egalitarian human bands predictably have a few individuals who are unusually disposed to actively bully or cheat others in their community and pay the price. This is true after thousands of generations of social selection.

It was earlier types of social control that caused a conscience to evolve, and it’s an evolved conscience that makes individuals so adept at this important type of self-inhibition. Yet today a fair number of risk-taking hunter-gatherers find themselves being executed, banished, ostracized, or shamed because the temptations to take free rides continue. They hope they can get away with it, but often they’re punished. Much less conspicuous are the far greater number who hold back for fear of being sanctioned and therefore do no serious damage to the altruists in the group.

I cannot use my ethnographies to demonstrate all of this statistically, for it’s very difficult to show why a behavior is absent or how prevalent it might be if it weren’t for fear of being sanctioned or pangs of conscience. But after Cephu was so thoroughly humiliated, any other band members sharing his free rider’s propensity to cheat in a net hunt surely would have been seriously deterred from actively expressing such predatory behavior, for fear of being discovered, confronted, shamed, and threatened with banishment by an extremely angry group. And the same obviously went for Cephu himself. Thus, even though his free-rider genes remained in the gene pool, at the level of phenotype Cephu’s free-riding behavior very likely was curtailed. And the ill-gotten meat was confiscated, so he was in no way a winner, while his sanctioners were repaid for their modest policing efforts by eating that same ill-gotten meat.

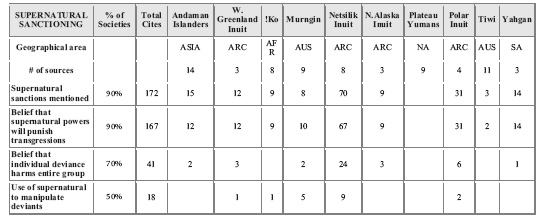

There’s one more means of free-rider suppression, which might even be seen as a special extension of the conscience. It comes in the form of supernatural sanctioning.30 For instance, foragers often have food taboos, which I suspect began to evolve long ago because they provided a dramatic way of warning inexperienced or careless group members against eating poisonous edibles. This is just a guess.

Table V (next page) follows my coding categories in showing just those supernatural sanctions that pertain to social behavior, and they might be seen as an extension of the conscience because consciences provide people with a means of moralistic feedback that is totally private, rather than public. Likewise, imaginary supernatural entities can quietly track behavior and then privately judge and punish the offender, just as the conscience does.31

As a deterrent, these agencies obviously can make people who believe in them less prone to commit murder, incest, or various other antisocial acts, especially in situations where the social group is less likely to learn of the crime. And in an earlier study that focused just on supernatural sanctioning and was based on a more sizable sample of eighteen LPA foraging societies, I discovered that such sanctions were often directed against precisely the types of deviance that were conducive to free riding. Here, in Table V, I have used just the same ten societies as were used in Tables II, III, and IV, and nine of them report moralistic supernatural sanctioning.

In the previous, more detailed study, it was clear that supernatural sanctions often are involved with food taboos. In the area of morals, they help to suppress free riding. At the bullying end of the spectrum the suppressed behaviors include murder and sorcery, and at the devious end they include thieving, lying, cheating, and lazy shirking. Thus, imaginary “overseers,” as well as real and vigilant social groups, have been suppressing free-riding behavior in most (and possibly all) LPA-type groups ever since humans became culturally modern—and probably somewhat earlier, if we assume that these supernatural ways of thinking must have taken some time to evolve.

TABLE V MORALISTIC SUPERNATURAL SANCTIONING*

*This table was adapted from Boehm 2008b.

If we add up all the effects seen in Tables I through V, free riders are obviously a continuing problem. However, their suppression is multi-faceted and quite potent and begins initially with a conscience, which internalizes rules that favor cooperation and disfavor social predation. The conscience serves not only as an inhibitor, but also as an early warning system that helps to keep prudent individuals from being sanctioned. Such individuals gain a fearful anticipatory awareness that the band has a variety of effective and sometimes dangerous social tools with which to manipulate, punish, or kill those who transgress. Conscience also involves a recognition that people have moral reputations and that these reputations can have social consequences in everyday life. There’s also a fear of supernatural retribution that can come even if others do not discover an individual’s deviance. In addition, there are those constant positive ideological reminders that promote extrafamilial generosity. And finally it seems likely that many people behave themselves because they enjoy feeling positively about their own conduct.

As long as those gifted with free-rider genes hold themselves in check, they can contribute to a cooperative economic system, play the role of being a good citizen, and still carry—and transmit to their offspring—an above-average complement of free-riding genes. I hope that ultimately these findings, based on relevant statistical patterns for appropriate types of contemporary hunter-gatherers, will make others less prone to take mathematical modeling at its face value, and therefore less liable to jump to what may amount to hasty negative conclusions about the ultimate limits of human generosity.

I say this for the benefit of general readers who have encountered such doubts in various highly popular works, such as those of Richard Dawkins, Robert Wright, and Matt Ridley,32 all of which to some degree take the standard negative stance that was so strongly promulgated by early sociobiologists like Michael Ghiselin.33 But I also say this for the benefit of thousands of evolutionary scholars—be they biologists, psychologists, economists, or anthropologists—in hopes that increasingly they will be willing to look beyond the ever-popular kin selection, reciprocal-altruism, mutualism, and narrowly defined costly signaling paradigms in their consideration of human generosity.

Our distinctively human means of free-rider suppression are so effective that as LPA hunter-gatherers we have succeeded in transforming our living groups from ancestral hierarchical societies, in which the bullying type of free riding can be rampant, to egalitarian groups in which an individual actively expresses such tendencies only at high personal risk. Indeed, egalitarianism can stay in place only with the vigilant and active suppression of bullies, who as free riders could otherwise openly take what they wanted from others who were less selfish or less powerful.34

In this connection, I want to propose an evolutionary credo far more optimistic than sociobiologist Michael Ghiselin’s skeptical “Scratch an altruist and watch a hypocrite bleed.”35 I do acknowledge that our human genetic nature is primarily egoistic, secondarily nepotistic, and only rather modestly likely to support acts of altruism, but the credo I favor would be “Scratch an altruist, and watch a vigilant and successful suppressor of free riders bleed. But watch out, for if you scratch him too hard, he and his group may retaliate and even kill you.”

Group punishment is a crucial part of this suppression-of-free-riding scenario, and especially in evolutionary economics some scholars have raised the specter of “second-order free riders”36 as a theoretical obstacle to groups being evolved to punish predatory deviants as I have shown human foragers in fact do today—and surely did yesterday.

The insights have come from experiments in which subjects who make unusually greedy offers to others may be punished even though the punisher, in refusing their low offer, comes out behind and therefore is paying a cost to punish. The second-order free-rider problem arises when one person abstains from punishing in order to let others pay the costs, a behavior that in real life would gain this free rider a genetic advantage. These insights are derived from formal game theory experiments that are explored mainly with college students,37 but also at times out in the field with tribesmen and a few foragers,38 all of whom have the opportunity to give up money in order to punish others who seem unduly selfish.

As these scholars define things, participation in group punishment itself is genetically altruistic because costs are paid to do so, which means that if free riders can hold back from punishment and thereby avoid investing the time and energy, and sometimes the risk, they can avoid paying costs that others are investing for the common good. This means that even as the group is punishing would-be aggressive free riders like malicious sorcerers or other bullies, or deceptive free riders like meat-cheaters, yet another type of free rider emerges: the one who stands aside to let others do the punishing—and thus cashes in on the rewards without paying any costs.39 In theory, this should result in the advance of the genes of these free-riding nonpunishers and the decline of the genes of cost-paying punishers—to the point that genetic dispositions to join in group punishment would seriously decline and free-rider suppression as I have just described it might, in theory, just fade away.

However, if we move from mathematical models and experimental subjects to the kind of people who’ve evolved our genes for us, my database shows that everywhere hunter-gatherers do in fact readily punish their deviants—and that at any given time some individuals will be much more active than others in doing so and that some may refrain entirely. Furthermore, my colleague Polly Wiessner, who has been doing fieldwork with the LPA !Kung Bushmen for thirty years, has never seen or heard of punishment of those who fail to join with the group in sanctioning deviants. And so far in my survey of group punishment among fifty LPA hunter-gatherers (see Tables I and IV), the punishment of nonpunishers is never mentioned in the hundreds of ethnographies even though punishment does take place so regularly—and even though there are plenty of abstentions.

My own opinion is that these abstentions need have no relation to free-rider genes. For instance, in dealing with the Mbuti Pygmy Cephu’s arrogant cheating, most members of the band actively shamed him, but members of the several households that were genealogically close to him were obviously staying to one side and appeared to be neutral.40 I believe that this simply involves social factors that apply to everyone, not just to those disposed to be free riders. By this I mean that it is quite predictable—and understandable by the rest of the group—that the close relatives or associates of a deviant may choose to stand back and let others deal with him harshly.

Such abstention may give the appearance of classical free riding, then, but over the long run there’s no such genetic effect because the structure of social role expectations explains these abstentions—without any need for free-rider modeling. One day I abstain because it’s my brother who has been caught as a thief, but I don’t actively support him either. Another time I actively participate in group sanctioning because it’s not a close relative who is the deviant.

As another example of costs and benefits evening out over time, consider more specifically hunter-gatherers’ use of capital punishment, as this was discussed in Chapter 4. We’ve seen that once in a long while the entire group may simultaneously mob a deviant,41 usually a bully who goes around intimidating group members, and takes him out through collective action. This equalized sharing of effort and risk does happen to neatly preclude the second-order genetic free-rider problem, but the immediate motivation is something else entirely. What foragers are worried about is, in fact, revenge.42 They know that if one of them were to kill a serious deviant, even if he was a truly bad guy his angry and grieving close relatives might well love him enough to engage in lethal retaliation. However, if most of the group participates simultaneously in his killing, there’s no way for his relatives to target and revenge-slay the person who killed him.

More often, however, execution by forager groups involves “delegation” (see Table IV, “Group member selected to assassinate culprit”), and this second pattern seems to be very widespread and may well be universal. First, the group arrives at a consensus that the deviant must be eliminated, and then usually a close relative is asked to do him in. The cultural logic is impeccable. When a family has just lost one of its hunters, it would be unthinkable for them to double their loss by revenge-killing another family member—especially an upright citizen who was willing to kill his own kinsman for the good of everybody. Here, too, revenge is averted, but in this case one person is generously and responsibly assuming the risks of playing executioner. Again, it’s a matter of structural position when the rest of the group delegates a kinsman to kill his own kin, so from the standpoint of gene selection, those who delegate him to do the dirty work are not acting as genetic free riders.

There remains the fact that often lesser degrees of social sanctioning are actively initiated by a few, with the general support of others, and that a cornered deviant might be dangerous. For instance, initially just one man took the lead in lashing out against the arrogant Cephu. However, this initial shamer had already learned that he had the rest of the band’s strong backing, for Turnbull’s psychologically rich description makes it clear that the others with him were equally incensed. He also knew that his guilty adversary, Cephu, understood that he was being criticized on behalf of the band, and that Cephu would be sufficiently intimidated that he would be unlikely to attack the lead criticizer. This group backing also was obvious when subsequently a mere boy insulted this arrogant cheater by not relinquishing his seat, which might have been quite risky under different circumstances.

Such group dynamics explain why the individual risks for those who lead a well-unified group majority in sanctioning are minimal—as long as the deviant’s close allies are standing aside. In turn, these same political dynamics also help to explain why second-order free riding appears not to have been a serious obstacle to the earlier evolution of group punishment—and why, in real life, “defectors” from group punishment don’t require punishment because things will even out in the evolutionary long run.

My conclusion is that no matter what takes place in experimental laboratories, evolutionary assumptions about the need to punish nonpunishers require further and critical consideration, for in everyday forager life the “group dynamics” are likely to be different from small-group game-playing contexts, as these have been scientifically contrived so far. Perhaps more of these group dynamics could be built into future experiments, taking into better account what hunter-gatherers actually do and were likely to have been doing in their culturally modern past. Meanwhile, we are left with the fact that classical LPA hunting-and-gathering communities do regularly punish deviance, that with them desisting from punishment is not viewed as a punishable deviant act, and that this version of social control has been in effect, and successful and powerful, for thousands of generations.

This conclusion brings in a further fact about these small foraging societies, namely, their political dynamics. These groups do not always stay united, for a morally ambiguous act of aggression can split a group, with the aggressor’s kinsmen and allies siding strongly with him while the rest of the group proclaims his deviance. In such cases, the group is straightforwardly divided to a point that the two factions are likely simply to fission and go their separate ways. But this was not quite the case with Cephu’s deviance, or with many other cases in which relatives merely stand aside and let the rest of the band do the active sanctioning. We must be careful to distinguish between some-what-less-than-unanimous moral sanctioning—and outright conflict.

Building on the discussion in Chapter 3, I have radically broadened the scope of what is normally referred to as social selection as this is practiced by a variety of species.43 For humans, I’ve now included Alexander’s positive social selection through reputational payoffs, and I’ve added group punishment, which I began to think about as long ago as in 1982 as a selection mechanism.44 Group punishment also leads to subsequent reputational disadvantages, so punishment and reputations are intertwined.

It was the combination of selection by reputation and active free-rider suppression that provided a “double whammy.” By considering these two basic human types of social selection in combination, I’m proposing what amounts to a far more comprehensive version of social selection theory than is found in costly signaling explanations of mating advantages, which recently have been of great interest to evolutionary scholars who study other animals like birds and who study hunter-gatherers.45 The comprehensive, “moralistic” social selection theory of altruism that I’m proposing here can now compete with theories based on group selection, reciprocal altruism, mutualism, and costly signaling, along with any new theories that others may come up with, as we continue to seek better ultimate explanations for the widespread human practice of extrafamilial generosity.

Obviously, this moral approach applies just to our own highly cultural species. Other animals can’t build a consensus by gossiping about favorable reputations, even though costly signaling mechanisms may function analogically. And only a very few species gang up socially in coalitions to punish individuals in the same group who rub them the wrong way. If Ancestral Pan hadn’t provided us with a modest but significant preadaptation in this direction, it’s difficult to see how our species could have either developed a conscience, or substantially neutralized the bullying free riders in its midst to become as altruistic as we are today.

The solution for the altruism paradox I’ve offered here looks mainly to this comprehensive, human version of social selection for ultimate causation. This has involved ongoing suppression of free-rider behavior and also some significant past modification of the underlying genes—especially where the free-riding tendencies involved a bully’s approach and could easily result in capital or other severe punishment. It also takes into account some hard to gauge but probably rather limited contributions from genetic group selection and also, phenotypically, some very potent contributions from a variety of cultural amplifiers that encourage extrafamilial generosity. I hope this combination of models will help to further explain the altruistic aspect of our common humanity, which contributes so profoundly to our quality of social life and its overall cooperative efficiency.

Altruism is important to moral evolution for several reasons. One is that the sympathetic feelings that so often underlie altruistic acts are built into the conscience; this enables us to connect emotionally with the problems and needs of others as we act on the prosocial values we have automatically internalized at an early age in growing up.46 Another is that so much of the content of our moral codes is oriented to amplifying the human potential for behaving prosocially, and it is sympathetic feelings that provide the potential in the first place.

I’ve argued that we do in fact possess innately altruistic traits (“scratch me—or scratch yourself—or scratch anyone but a serious psychopath—and see an altruist, not a hypocrite, bleed!”), and without such traits conscience functions would be quite different. Indeed, our moral life would be based mostly in shame feelings and fear of dire punishment, whereas the prosocial preaching that leads to the effective and often sympathetically based cooperation we’ve seen with hunter-gatherers would be absent because it couldn’t work.47

A shameful conscience gives us a sense of right and wrong, but there’s much more to moral life as we know it. The key ingredient of sympathetic feelings provides a motivational basis for much of our altruism, and this is an important element in systems of indirect reciprocity, for the participants are emotionally responsive to the needs of other individuals. Sensing the needs of others can lead us to spontaneously respond with generosity, and this, along with counting on future benefits from the generosity of others, makes the system work. Altruism, in short, is important.

Once people had become culturally (and morally) modern, the state of human affairs was basically that of the LPA hunter-gatherers I’ve described in their contemporary incarnations. To judge from today’s behavior, our recent forbears were mainly egoists and secondarily nepotists, but as I’ve argued, they also were significantly altruistic in their genetic nature. The resulting extrafamilial generosity gave them something important to build upon culturally when they needed to cooperate with a specific vision of the common good in mind—as when a large carcass was there to be shared and serious conflict was to be avoided. These more recent hunter-gatherers had consciences just like ours, and in many ways their virtues, crimes, and punishments surely were very much like ours, as were their personal sense of what was shameful and their sense of good or bad reputations in others.

Large social brains enabled these people to see that the limited altruistic tendencies of group members could be socially reinforced for the common good. And basically it’s because of these powerful brains that people invented and maintained the systems of indirect reciprocity that have served them so handsomely and so flexibly over the ages. This socially constructive aspect of human brainpower has helped to make our evolutionary career fully as distinctive as Darwin thought it to be, and we will be exploring this flexibility further in its social and ecological aspects. But without a significant degree of innate altruism and extrafamilially generous feelings to work with, I suspect that this remarkable evolutionary career would have gone in a very different direction, indeed.