In this chapter, you will work with integer exponents, square roots, and cube roots. You will extend your understanding of the connections between proportional relationships, lines, and linear equations. You will analyze and solve linear equations in one variable and pairs of simultaneous linear equations in two variables. You will also solve mathematical and real-world problems leading to linear equations in one variable and to two linear equations in two variables.

Understanding and Working with Integer Exponents

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.A.1)

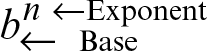

In this section, you will extend your understanding of exponents to include all integer exponents. An exponent is a small raised number written to the upper right of its base. In the exponential expression bn, b is the base and n is the exponent.

Here is an example.

In the exponential expression 25, 2 is the base and 5 is the exponent.

Tip: Exponents are written as superscripts, so they are smaller than the other numbers in an expression. Write an exponent slightly raised and immediately to the right of the number that is its base. Do this carefully so that, for example, 25 is not mistaken for 25.

Understanding Positive Integer Exponents

Consider the product 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2. This product is an example of repeated multiplication. Repeated multiplication means using the same number as a factor many times. You use positive integer exponents to express repeated multiplication. For the product 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2, write 25. The expression 25 means “use 2 as a factor 5 times.”

In general, if b is a real number and n is a positive integer, then  . The positive integer exponent, n, tells how many times the base, b, is used as a factor. Read bn as “b to the nth power.”

. The positive integer exponent, n, tells how many times the base, b, is used as a factor. Read bn as “b to the nth power.”

The first power of a number is the number. So, 61 is simply 6.

Tip: When no exponent is written on a number, the exponent is 1, even though it’s not written.

The second power of a number is its square. So, 62 is “six squared.” The third power of a number is its cube. So, 63 is “six cubed.” Beyond the third power, 64 is “six to the fourth power,” 65 is “six to the fifth power,” and so on.

To evaluate an exponential expression, do to the base what the exponent tells you to do. Evaluating exponential expressions is known as exponentiation.

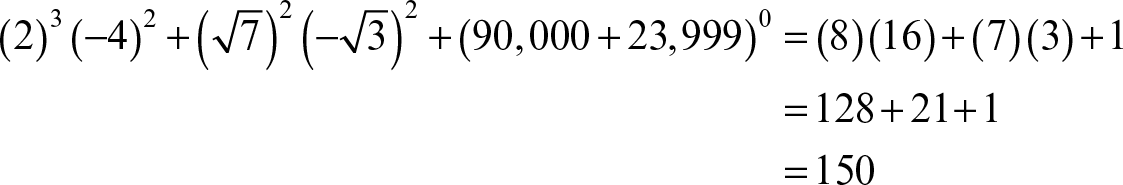

Here are examples when the exponent is a positive integer.

25 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 = 32 (Tip: Don’t multiply the base by the exponent. 25 is not 2 × 5. 25 is 32; 2 × 5 is 10.)

34 = 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 = 81

106 = 10 × 10 × 10 × 10 × 10 × 10 = 1,000,000

62 = 6 × 6 = 36

53 = 5 × 5 × 5 = 125

04 = 0 × 0 × 0 × 0 = 0

Tip: In an exponentiation expression, which number is the exponent and which is the base makes a difference in the value of the expression. Unlike multiplication, where 5 × 2 = 2 × 5 = 10, exponential expressions do NOT have a commutative property. So 25 ≠ 52; 25= 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 = 32, 52 = 5 × 5 = 25.

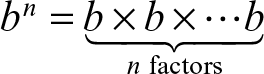

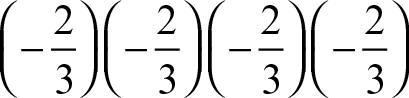

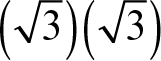

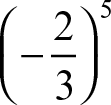

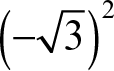

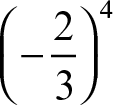

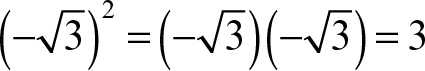

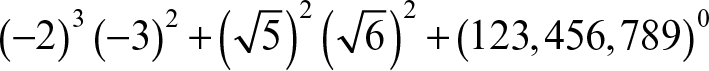

When the exponent is a positive integer, the base can be any number. To make the problem easier to read, enclose negative numbers and fractions and decimals in parentheses. Also use parentheses to indicate multiplication. Here are examples.

Keep in mind that an exponent applies only to the number or grouped quantity to which it is attached. Here are examples.

- Fill in the blank(s).

- In the exponential expression bn, __________ is the base and __________ is the exponent.

- A positive integer exponent attached to a number tells how many times the number is used as a __________.

- The second power of a number is its __________.

- The third power of a number is its __________.

- Express the product as an exponential expression.

- 7 × 7 × 7 × 7 × 7

- (1.5)(1.5)(1.5)

- Evaluate the expression.

- (0.3)4

- 53

- –54

- 2 · 32

Solutions

-

- b; n

- factor

- square

- cube

- 75

- (1.5)3

- (0.3)4 = (0.3)(0.3)(0.3)(0.3) = 0.0081

- 53 = 5 × 5 × 5 = 125

- –54 = –(5 × 5 × 5 × 5) = –(625) = –625

- 2 · 32 = 2 · 9 = 18

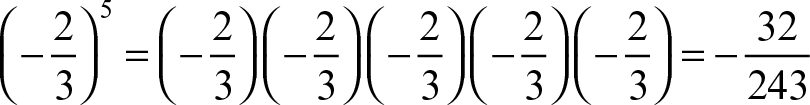

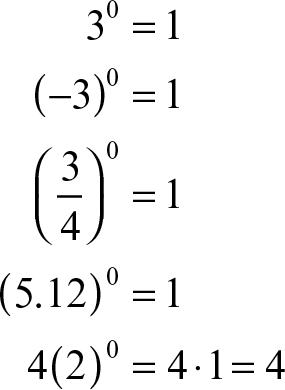

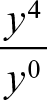

When zero is the exponent on a nonzero number, the value of the exponential expression is 1. That is, if b is a number such that b ≠ 0, then b0 = 1. Here are examples.

Tip: (0)0 has no meaning. It is undefined.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank.

- If b is a number such that b ≠ 0, then b0 = __________.

- When zero is the exponent, the base cannot be ___________.

- Evaluate the expression.

- (–7)0

- (7.5)0

- (900 + 1,000)0

- 8(0.3)0

Solutions

- 1

- zero

- (–7)0 = 1

- (7.5)0 = 1

- (900 + 1,000)0 = 1

- 8(0.3)0 = 8(1) = 8

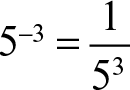

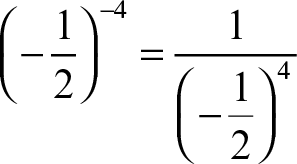

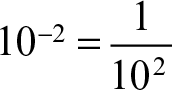

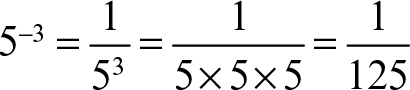

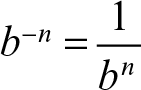

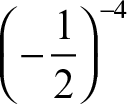

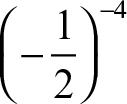

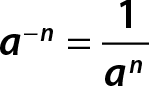

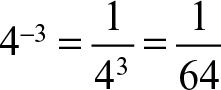

Understanding Negative Integer Exponents

Negative integer exponents denote reciprocals. If b is a number such that b ≠ 0,  . Here are examples.

. Here are examples.

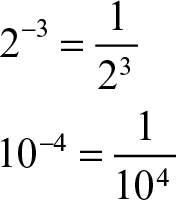

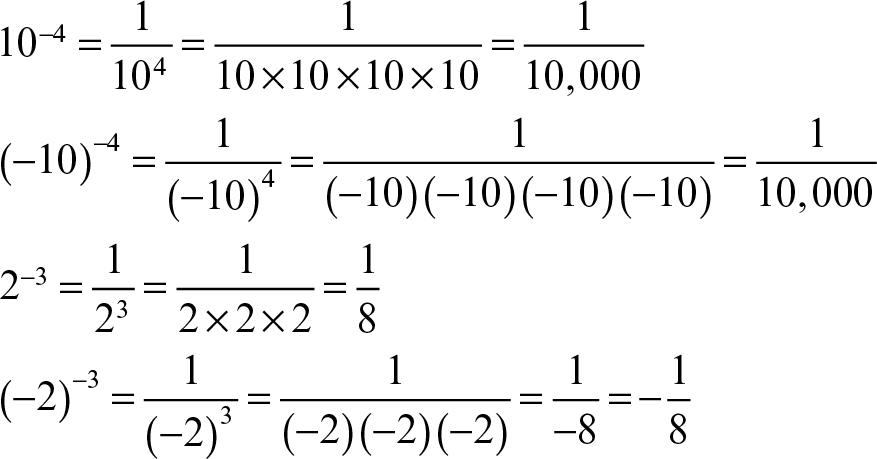

To evaluate an exponential expression that has a negative integer exponent, first express it as the reciprocal of the matching exponential expression that has a positive integer exponent. Then perform the repeated multiplication. Here are examples.

Tip: Notice (–2)–3 is negative because (–2)3 is –8, not because the exponent, –3, is negative. The negative part of the exponent tells you to write a reciprocal; it does not tell you to make your answer negative. For instance,  .

.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank.

- Negative integer exponents denote __________.

- If b is a number such that b ≠ 0, b–n = __________.

- Write the expression as an equivalent expression with a positive exponent.

- 5–2

- 10–2

- (0.2)–2

- Evaluate the expression.

- 5–2

- 10–2

- (0.2)–2

Solutions

- reciprocals

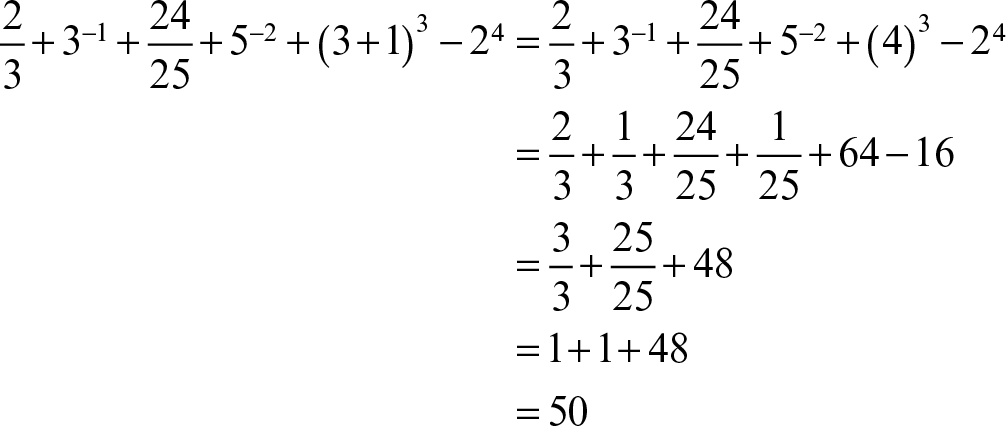

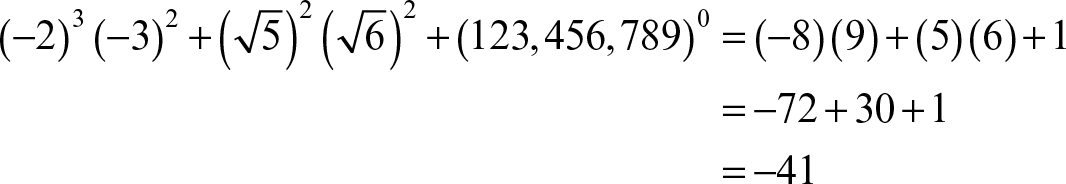

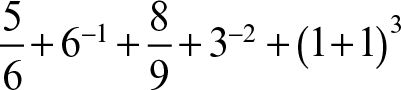

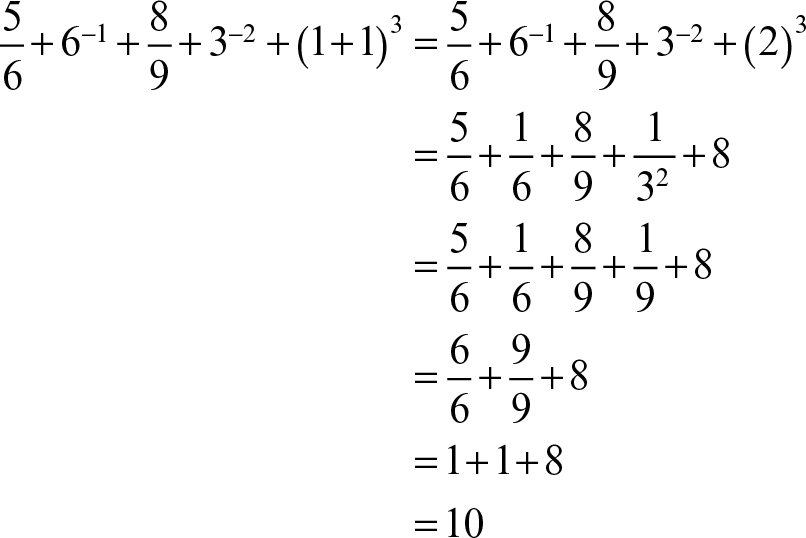

Reviewing the Order of Operations

When you evaluate numerical expressions, follow the order of operations.

- Compute inside Parentheses (or other grouping symbols).

- Do Exponentiation.

- Multiply and Divide in the order in which they occur from left to right.

- Add and Subtract in the order in which they occur from left to right.

Tip: Use the mnemonic “Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally”—abbreviated as PEMDAS—to help you remember the order of operations. The first letters stand for “Parentheses, Exponentiation, Multiplication, Division, Addition, and Subtraction.”

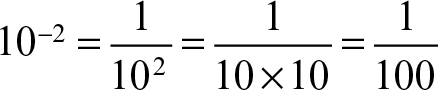

Evaluate 80 – 32(9 – 7)3 + (–1)4(9)2.

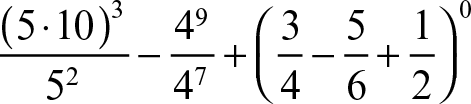

Evaluate  .

.

Evaluate  .

.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Evaluate 60 – 23(9 + 1)2 + (–1)2(5)3.

- Evaluate

.

. - Evaluate

.

.

Solutions

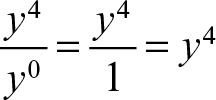

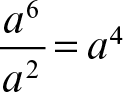

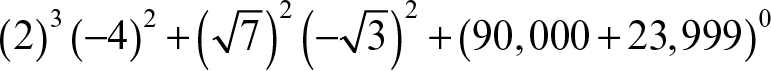

Understanding and Applying the Properties of Integer Exponents

If a and b are any nonzero real numbers and m and n are integers, you can transform exponential expressions by applying the properties detailed here.

Property 1: When you multiply exponential expressions that have the same base, add the exponents and keep the same base.

bmbn = bm + n

For instance, when m and n are positive integer exponents, bm is m factors of b and bn is n factors of b. When you multiply bm by bn, you get a total of (m + n) factors of b.

Tip: This property works only if the bases are the same. Notice the base b appears twice in bmbn.

Here is an example.

4243 = 42 + 3 = 45 [because 4243 = (4 × 4) × (4 × 4 × 4) = 45]

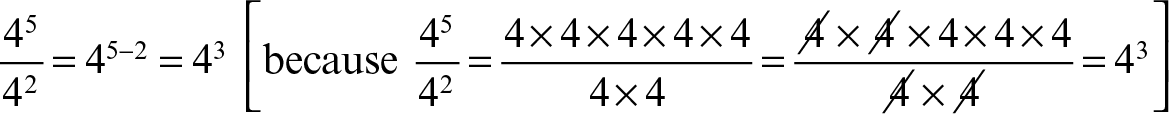

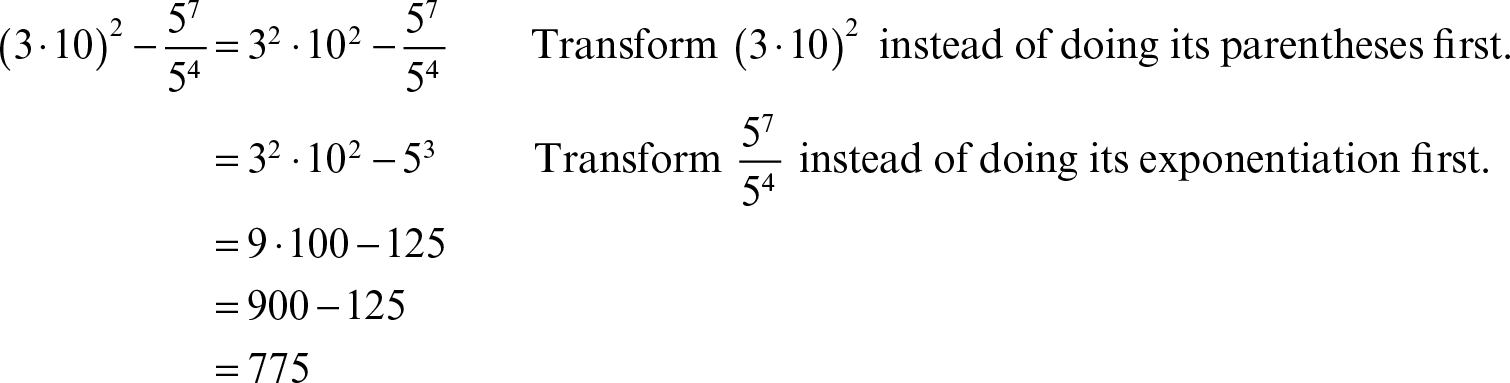

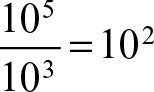

Property 2: When you divide exponential expressions that have the same base, subtract the divisor exponent from the dividend exponent and keep the same base.

For instance, when m and n are positive integer exponents with m > n, bm is m factors of b and bn is n factors of b. When you divide bm by bn, n factors of b in the denominator will cancel n factors of b in the numerator, leaving (m – n) factors of b in the numerator .

Tip: This property works only if the bases are the same. Notice the base b appears twice in ![]() .

.

Here is an example.

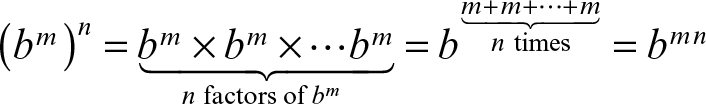

Property 3: When you raise an exponential expression to a power, keep the base and multiply its exponent by the power.

(bm)n = bmn

Tip: Notice the base b appears only once in (bm)n.

For instance, when m and n are positive integer exponents, bm is m factors of b and (bm)n is n factors of bm. So, using Property 1,

for a total of mn factors of b.

for a total of mn factors of b.

Here is an example.

(52)3 = 52 · 3 = 56 [because (52)3 = (52)(52)(52) = 52 + 2 + 2 = 56]

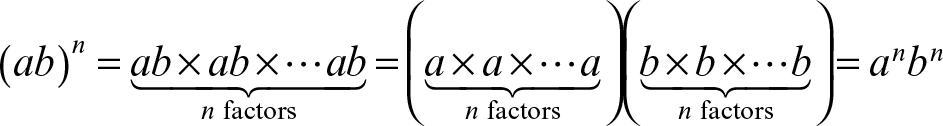

Property 4: A product of two or more factors raised to a power is the product of each factor raised to the power.

(ab)n = anbn

For instance, when n is a positive integer exponent,

This property means that you get the same answer whether you multiply two factors first and then raise the product to a power, or you raise each factor to a power and then multiply the results. Here is an example.

(2 · 5)3 = (10)3 = 1,000 and (2 · 5)3 = 23 · 53 = 8 · 125 = 1,000

Tip: Don’t confuse Property 4 [(ab)n = anbn] with Property 1 [bmbn = bm + n]. Property 4 has the same exponent and different bases. Property 1 has the same base and different exponents.

Property 5: If a ≠ 0,  , by definition.

, by definition.

Applying a negative exponent to a nonzero number results in a reciprocal. Here is an example.

Property 6: If a ≠ 0, a0 = 1, by definition.

When zero is the exponent on any nonzero number or quantity, the value of the expression is always 1. Here is an example.

(−658.89)0 = 1

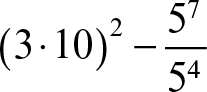

Sometimes, you might find it convenient to transform exponential expressions by applying the above properties before proceeding through the order of operations.

Here is an example.

Evaluate  .

.

Tip: Transforming exponential expressions first simplifies the calculations in this problem.

A word of caution: Be careful when transforming exponential expressions when you have grouping symbols. It is very important when you have addition or subtraction inside the grouping symbol that you perform operations in grouping symbols first.

The exception is when the exponent on a grouping symbol is zero. If you are certain that the sum or difference inside the grouping symbol is nonzero, you can evaluate the expression to be 1 without performing the operations inside the grouping symbol first.

Here are examples.

| (1 + 5)3 = (6)3 = 216 | Add first, then do exponentiation. |

| Note: (1 + 5)3 ≠ 13 + 53 = 1 + 125 = 126 | Exponentiation does not “distribute” over addition. |

| (7 − 4)3 = 33 = 27 | Subtract first, then do exponentiation. |

| Note: (7 − 4)3 ≠ 73 − 43 = 343 − 64 = 279 | Exponentiation does not “distribute” over subtraction. |

| (1,254 + 51,000)0 = 1 | A nonzero number raised to the zero power is 1. |

Here is a summary of the properties of exponents.

Properties of Exponents

If a and b are any nonzero real numbers and m and n are integers, the following properties hold.

- bmbn = bm+n

- (bm)n = bm−n

- (ab)n = anbn

- If a ≠ 0,

- If a ≠ 0, a0 = 1

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank(s).

- When you multiply exponential expressions that have the same base, __________ the exponents and keep the same base.

- When you divide exponential expressions that have the same base, subtract the __________ exponent from the __________ exponent and keep the same base.

- When you raise an exponential expression to a power, keep the base and __________ its exponent by the power.

- A product of two or more factors raised to a power is the __________ of each factor raised to the power.

- Use the properties of exponents to obtain an equivalent exponential expression.

- 103 × 105

- 10–2 × 105

- (103)5

- Use the properties of exponents to perform the indicated operation.

- (2a)3

- b0 · b5

- (x−6)−2

- x · x2

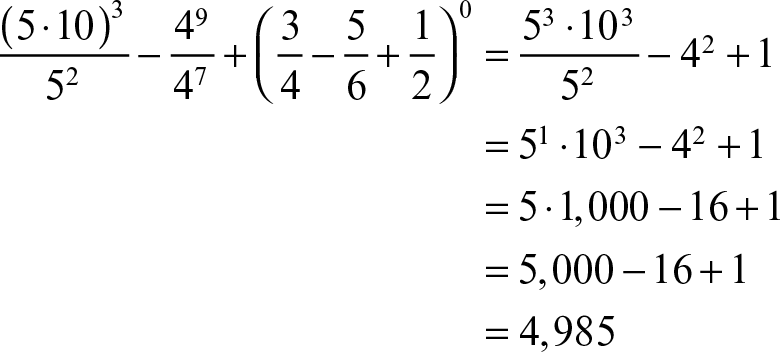

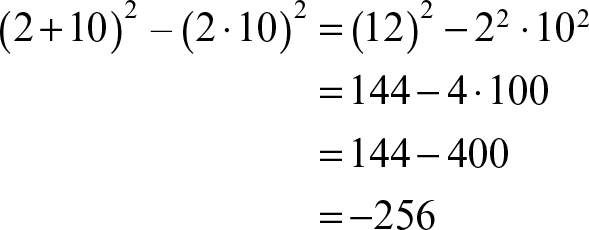

- Evaluate. Use the property of exponents when appropriate.

- (2 + 10)2 – (2 · 10)2

Solutions

- add

- divisor; dividend

- multiply

- product

- 103 × 105 = 108

- 10–2 × 105 = 102

- (103)5 = 1015

Understanding and Working with Scientific Notation

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.A.3, CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.A.4)

Scientific notation is a way to write very large or very small numbers in a shortened form. Scientific notation helps keep track of the decimal places and makes performing computations with these numbers easier.

A number written in scientific notation is written as a product of two factors. The first factor is a number that is greater than or equal to 1 but less than 10. The second factor is an integer power of 10. The idea is to make a product that will equal the given number. Any decimal number can be written in scientific notation.

Writing Large Numbers in Scientific Notation

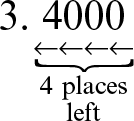

Follow these steps to write a large number in scientific notation.

Step 1. Create the first factor. Move the decimal point left, to the immediate right of the first nonzero digit of the number.

Step 2. Create the second factor. The second factor will be an integer power of 10. The exponent for the power of 10 is the number of places you moved the decimal point in Step 1. For numbers greater than or equal to 10, it will be a positive integer.

Tip: As the exponent increases by 1, the value of the number increases by a factor of 10.

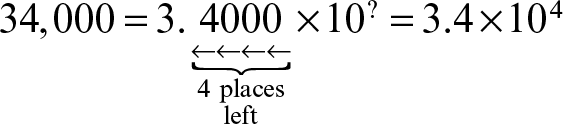

Here is an example.

Write 34,000 in scientific notation.

Step 1. Create the first factor. Move the decimal point left, to the immediate right of the first nonzero digit of the number.

Step 2. Create the second factor. The exponent for the power of 10 is the number of places you moved the decimal point in Step 1. It is a positive integer.

Tip: When you move the decimal point to the left, the exponent on 10 is positive.

As long as you make sure your first factor is greater than or equal to 1 and less than 10, you can always check whether you wrote the number in scientific notation correctly. Expand your answer to decimal notation by multiplying to see whether you get your original number back.

Tip: A shortcut for multiplying by 10n is to move the decimal point n places to the right, inserting zeros as needed.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank.

- The first factor of a number written in scientific notation is greater than or equal to 1, but less than __________.

- Exponential expressions such as 101, 102, 103, and so on are __________ of 10.

- Write the number in scientific notation.

- 456,000,000

- 93,000,000

- 26

- 130

- 1,760

- Write the number in decimal notation.

- 2.68 × 109

- 5.3 × 104

- 1.5 × 102

- 3.25 × 108

- 2 × 105

- The diameter of the sun is about 1,400,000 kilometers. Express this measurement in scientific notation.

- 10

- powers

- 456,000,000 = 4.56 × 108

- 93,000,000 = 9.3 × 107

- 26 = 2.6 × 101

- 130 = 1.3 × 102

- 1,760 = 1.76 × 103

- 2.68 × 109 = 2,680,000,000

- 5.3 × 104 = 53,000

- 1.5 × 102 = 150

- 3.25 × 108 = 325,000,000

- 2 × 105 = 200,000

- 1.4 × 106

Writing Small Numbers in Scientific Notation

Follow these steps to write a small number in scientific notation.

Step 1. Create the first factor. Move the decimal point right, to the immediate right of the first nonzero digit of the number.

Step 2. Create the second factor. The second factor will be an integer power of 10. The exponent for the power of 10 is the negative of the number of places you moved the decimal point in Step 1. For numbers between 0 and 1, it will be a negative integer.

Tip: As the exponent decreases by 1, the value of the number decreases by a factor of 10.

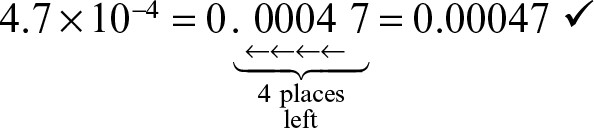

Here is an example.

Write 0.00047 in scientific notation.

Step 1. Create the first factor. Move the decimal point right, to the immediate right of the first nonzero digit of the number.

Step 2. Create the second factor. The exponent for the power of 10 is the negative of the number of places you moved the decimal point in Step 1. It is a negative integer.

Tip: When you move the decimal point to the right, the exponent on 10 is negative.

After you make sure your first factor is greater than or equal to 1 and less than 10, check whether you wrote the number in scientific notation correctly. Expand your answer to decimal notation by multiplying to see whether you get your original number back.

Tip: A shortcut for multiplying by 10−n is to move the decimal point n places to the left, inserting zeros as needed.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Write the number in scientific notation.

- 0.00004

- 0.000000975

- 0.3

- 0.0064

- 0.000000047

- Write the number in decimal notation.

- 2.6 × 10−2

- 1.572 × 10−2

- 2 × 10−2

- 8.6 × 10−2

- 9 × 10−2

- A dollar bill is about 0.0043 inches thick. Express this measurement in scientific notation.

Solutions

- 0.00004 = 4 × 10−2

- 0.000000975 = 9.75 × 10−2

- 0.3 = 3 × 10−2

- 0.0064 = 6.4 × 10−2

- 0.000000047 = 4.7 × 10−2

- Write the number in decimal notation.

- 2.6 × 10−2 = 0.0000000026

- 1.572 × 10−2 = 0.001572

- 2 × 10−2 = 0.0002

- 8.6 × 10−2 = 0.086

- 9 × 10−2 = 0.0000000009

- 4.3 × 10−2

Selecting Appropriate Units for Measurements of Very Large or Very Small Quantities

The units for measurements of very large or very small quantities should be appropriate for the situation. Make sure your choice of units communicates the size of the measurement in a meaningful way to your intended audience. Here are examples.

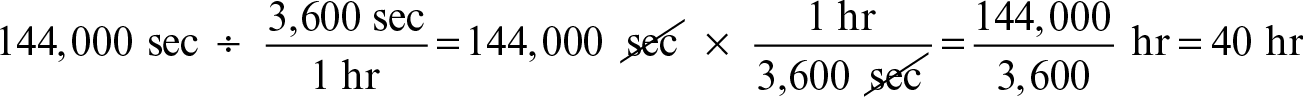

Delphina tells her friend Jason that she spends about 144,000 seconds working on homework each month during the school year. About how many hours does Delphina spend on homework each month?

There are 60 minutes in an hour and 60 seconds in a minute. (See the appendix for measurement conversions.) So, there are 60 × 60 = 3,600 seconds in an hour.

If Delphina spends about 40 hours on homework each month, which choice of measurement unit would better communicate the size of the measurement in a meaningful way to Jason: seconds or hours?

Hours would better communicate the size of the measurement in a meaningful way to Jason.

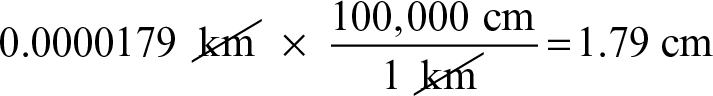

Andrew tells his 10-year-old brother that the diameter of a dime is about 0.0000179 kilometer.

- How many centimeters is 0.0000179 kilometer?

- Which choice of measurement unit would better communicate the size of the measurement in a meaningful way to Andrew’s brother: kilometers or centimeters?

(a) There are 1,000 meters in a kilometer and 100 centimeters in a meter. (See the appendix for measurement conversions.) So, there are 1,000 × 100 = 100,000 centimeters in a kilometer.

0.0000179 kilometer is 1.79 centimeters.

(b) Centimeters would better communicate the size of the measurement in a meaningful way to Andrew’s brother.

![]() Try These

Try These

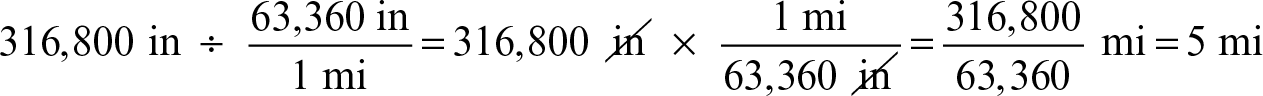

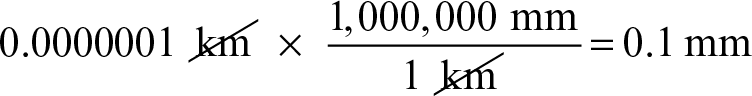

- Talia tells her classmate Dangelo that the distance from her house to school is 316,800 inches.

- How many miles is Talia’s house from school?

- Which choice of measurement unit would better communicate the size of the measurement in a meaningful way to Dangelo: inches or miles?

- Marcos tells his friend Mona that the naked human eye can see objects as small as 0.0000001 kilometer.

- How many millimeters is 0.0000001 kilometer?

- Which choice of measurement unit would better communicate the size of the measurement in a meaningful way to Mona: kilometers or millimeters?

Solutions

- There are 5,280 feet in a mile and 12 inches in a foot. (See the appendix for measurement conversions.) So, there are 5,280 × 12 = 63,360 inches in a mile.

Talia’s house is 5 miles from school.

- Miles would better communicate the size of the measurement in a meaningful way to Dangelo.

- There are 5,280 feet in a mile and 12 inches in a foot. (See the appendix for measurement conversions.) So, there are 5,280 × 12 = 63,360 inches in a mile.

- There are 1,000 meters in a kilometer and 1,000 millimeters in a meter. (See the appendix for measurement conversions.) So, there are 1,000 × 1,000 = 1,000,000 millimeters in a kilometer.

0.0000001 kilometer is 0.1 millimeter.

- Millimeters would better communicate the size of the measurement in a meaningful way to Mona.

- There are 1,000 meters in a kilometer and 1,000 millimeters in a meter. (See the appendix for measurement conversions.) So, there are 1,000 × 1,000 = 1,000,000 millimeters in a kilometer.

Interpreting Scientific Notation Generated by Technology

Many scientific and graphing calculators and other technology devices display scientific calculators using E notation. Here are examples.

2.1E5 means 2.1 × 105 = 210,000

6.4E−5 means 6.4 × 10−5 = 0.000064

Tip: Calculators have a special key for entering negative signs. Do not use the subtraction key. Check your calculator manual for instructions.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Write 1.3E6 in decimal notation.

- Write 4.35E−4 in decimal notation.

Solutions

- 1.3E6 = 1.3 × 106 = 1,300,000

- 4.35E−4 = 4.35 × 10−4 = 0.000435

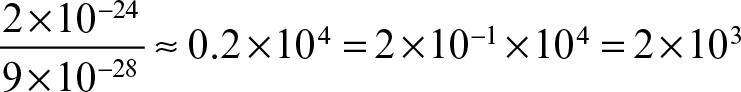

Multiplying and Dividing Numbers Written in Scientific Notation

You can compute with numbers written in scientific notation. When your answer is a very large or a very small number, you should express it in proper scientific notation. Otherwise, express your answer in decimal notation.

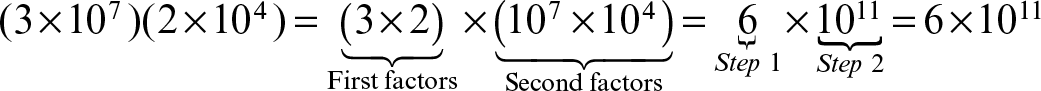

To multiply two numbers written in scientific notation, follow these steps.

Step 1. Multiply the first factors of each number.

Step 2. Using the properties of exponents, multiply the second factors of each number.

Step 3. If the result of Step 1 is greater than 10, rewrite it in scientific notation. Simplify the resulting expression so that your final answer is in proper scientific notation.

Here is an example.

Compute (3 × 107)(2 × 104).

Tip: Step 3 is not needed in the above example because the answer is in proper scientific notation.

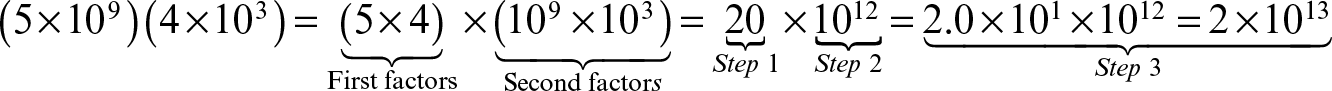

Here is an example in which Step 3 is needed.

Compute (5 × 109)(4 × 103).

Here are additional examples.

Compute (2 × 105)(3 × 10−2).

(2 × 105)(3 × 10−2) = (2 × 3) × (105 × 10−2) = 6 × 10−2

Compute (3.5 × 10−2)(2 × 10−2).

(3.5 × 10−2)(2 × 10−2) = (3.5 × 2) × (10−2 × 10−2) = 7 × 10−2

Compute (50 × 10−2)(6 × 10−2).

(50 × 10−2)(6 × 10−2) = (50 × 6) × (10−2 × 10−2) = 300 × 10−2 = 3.00 × 102 × 10−2 = 3 × 10−2

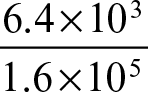

Dividing

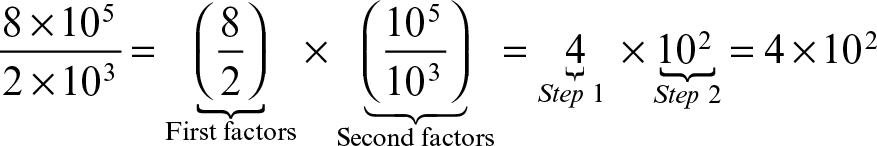

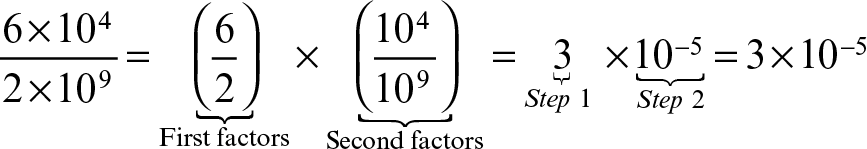

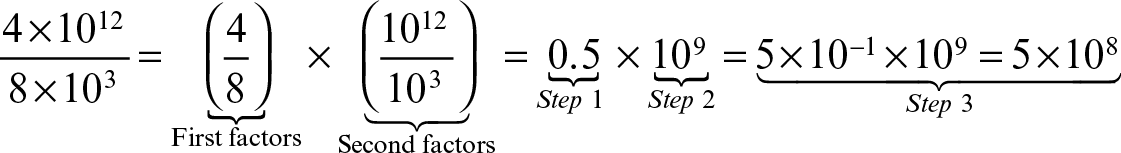

To divide two numbers written in scientific notation, follow these steps.

Step 1. Divide the first factors of each number.

Step 2. Using the properties of exponents, divide the second factors of each number.

Step 3. If the result of Step 1 is less than 1, rewrite it in scientific notation. Simplify the resulting expression so that your final answer is in proper scientific notation.

Here are examples.

Compute ![]() .

.

Compute ![]() .

.

Compute ![]() .

.

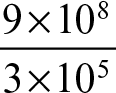

![]() Try These

Try These

- Compute as indicated. Express your answer in proper scientific notation.

- (4 × 107)(1.5 × 106)

- (4 × 10−5)(2 × 104)

- (5 × 106)(2.4 × 104)

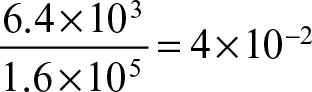

- The mass of the planet Jupiter is approximately 2 × 1027 kilograms. The mass of Earth is approximately 6 × 1024 kilograms. The mass of Jupiter is approximately how many times larger than the mass of Earth? Express your answer in proper scientific notation and, if appropriate, in decimal notation as well.

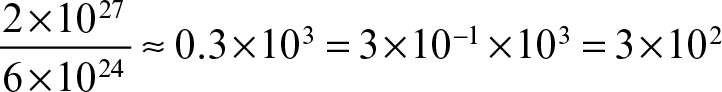

- The mass of a hydrogen atom is about 2 × 10−2 grams. The mass of an electron is about 9 × 10−2 grams. How many times heavier is a hydrogen atom than an electron? Express your answer in proper scientific notation and, if appropriate, in decimal notation as well.

Solutions

- (4 × 107)(1.5 × 106) = 6 × 1013

- (4 × 10−5)(2 × 104) = 8 × 10−1

- (5 × 106)(2.4 × 104) = 12 × 1010 = 1.2 × 101 × 1010 = 1.2 × 1011

The mass of Jupiter is about 3 × 102 = 300 times the mass of Earth.

A hydrogen atom is about 2 × 103 = 2,000 times heavier than an electron.

Solving One-Variable Linear Equations

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.C.7.A, CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.C.7.B)

An equation is a statement that two mathematical expressions are equal. An equation has two sides. Whatever is on the left side of the equal sign is the left side (LS) of the equation , and whatever is on the right side of the equal sign is the right side (RS) of the equation.

In a one-variable linear equation, there is only one variable, the variable has an unwritten exponent of 1, and no product of variables or variable divisors are allowed.

A solution to a one-variable linear equation is a number that when substituted for the variable makes the equation true. An equation is true when the left side has the same value as the right side. For example, −5 is a solution to the equation 2x + 8 = −2. It is a number that when substituted for x makes the equation 2x + 8 = −2 a true statement.

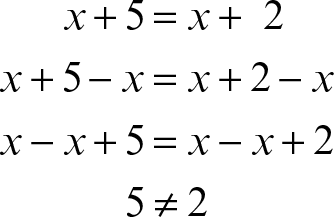

The set consisting of all solutions to an equation is the equation’ssolution set. If the solution set is all real numbers, the equation is anidentity. For example, x + 5 =x + 2 + 3 is an identity because any number substituted for x will make the equation true. Thus, an identity has an infinite number of solutions. If the solution set is empty, the equation hasno solution. For example, x + 5 =x + 2 has no solution because there is no number that will make this equation true. Equations that have the same solution set areequivalent equations.

To solve a linear equation in one variable means to find its solution set. Unless the equation is an identity or has no solution, the solution set will consist of one number. To determine whether a number is a solution to a one-variable equation, replace the variable with the number and perform the operations indicated on each side of the equation. If a true equation results, the number is a solution. This process is called checking a solution. For example, −5 is a solution to the equation 2x + 8 = −2 because 2(−5) + 8 = −10 + 8 = −2 is a true statement.

The equal sign in an equation is like a balance point. To keep the equation in balance, whatever you do to one side of the equation you must do to the other side of the equation. The strategy in solving an equation is to proceed through a series of “undoing” steps until you produce an equivalent equation that has this form:

variable = solution

A one-variable linear equation is solved when you succeed in getting the variable by itself on one side of the equation only, the variable’s coefficient is understood to be 1, and the other side of the equation is a single number all by itself.

Tip: Getting the variable term by itself on one side of the equation is referred to as isolating the variable.

The main actions that will result in equivalent equations as you proceed through the undoing process are

- Adding the same number to both sides of the equation.

- Subtracting the same number from both sides of the equation.

- Multiplying both sides of the equation by the same nonzero number.

- Dividing both sides of the equation by the same nonzero number.

Tip: Never multiply or divide both sides of an equation by 0.

What has been done to the variable determines which operation you should do. You do it to both sides of the equation to keep it balanced. You “undo” an operation by using the inverse of the operation. Addition and subtraction undo each other, and multiplication and division (or multiplying by the reciprocal) undo each other.

With that said, how do you proceed?

To solve an equation, follow these six steps.

Step 1. If the equation has parentheses, use the distributive property to remove them.

Step 2. Combine like terms, if any, on each side of the equation.

Step 3. If the variable appears on both sides of the equation, eliminate the variable from one side of the equation. Add a variable expression to both sides of the equation or subtract a variable expression from both sides so that the variable appears on only one side of the equation. Then combine like terms.

Step 4. Isolate the variable term. If a number is added to the variable term, subtract that number from both sides of the equation. If a number is subtracted from the variable term, add that number to both sides of the equation. Then combine like terms.

Step 5. Divide both sides of the equation by the coefficient of the variable. If the coefficient is a fraction, divide by multiplying both sides of the equation by the fraction’s reciprocal. (Tip: This step should always result in 1 being understood as the coefficient of the variable because you have divided out like factors.)

Step 6. Check the solution by substituting it into the original equation.

Tip: Skip steps that are not needed for the equation you are solving.

One Solution

Here are examples of solving one-variable linear equations in which there is exactly one solution.

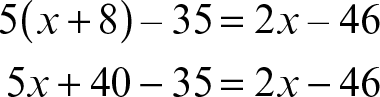

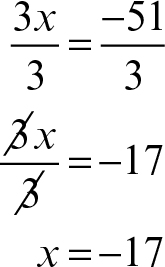

Solve 5(x + 8) − 35 = 2x − 46.

Step 1. Use the distributive property to remove parentheses.

5x + 5 = 2x − 46

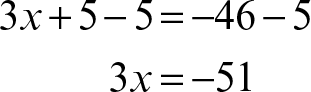

Step 3. Eliminate the variable from the RS of the equation by subtracting 2x from both sides of the equation. Then combine like terms.

Step 4. Isolate the variable term by subtracting 5 from both sides of the equation. Then combine like terms.

Step 5. Divide both sides of the equation by the coefficient of the variable.

Step 6. Check the solution.

Here’s another example.

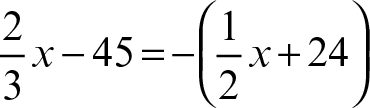

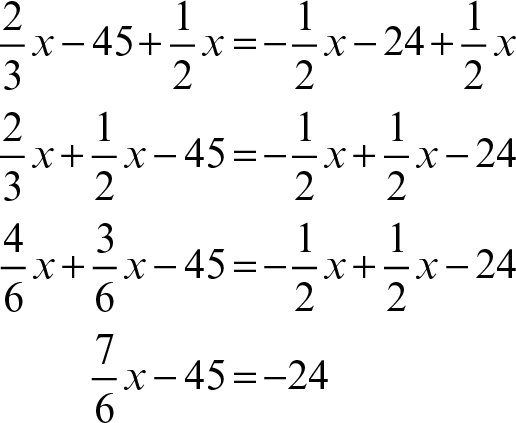

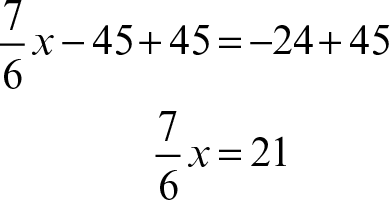

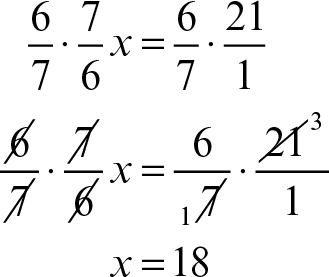

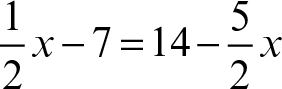

Solve  .

.

Step 1. Use the distributive property to remove parentheses.

Tip: When a negative sign immediately precedes a parentheses, remove the parentheses, but change the sign of every term inside the parentheses.

Step 3. Eliminate the variable from the RS of the equation by adding ![]() to both sides of the equation. Then combine like terms.

to both sides of the equation. Then combine like terms.

Step 4. Isolate the variable term by adding 45 to both sides of the equation. Then combine like terms.

Step 5. Multiply both sides of the equation by ![]() , the reciprocal of

, the reciprocal of ![]() , the coefficient of the variable.

, the coefficient of the variable.

Step 6. Check the solution.

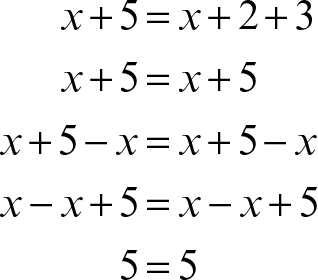

Infinite Number of Solutions

When you attempt to solve an identity, you obtain an equation that has the form a = a, where a is a real number. You have an infinite number of solutions because any number substituted for x will make the equation true. Here is an example.

No Solution

When you attempt to solve an equation that has no solution, you obtain an equation that has the form a = b, where a and b are unequal real numbers. There is no number that will make the equation true. Here is an example.

Solve x + 5 = x + 2.

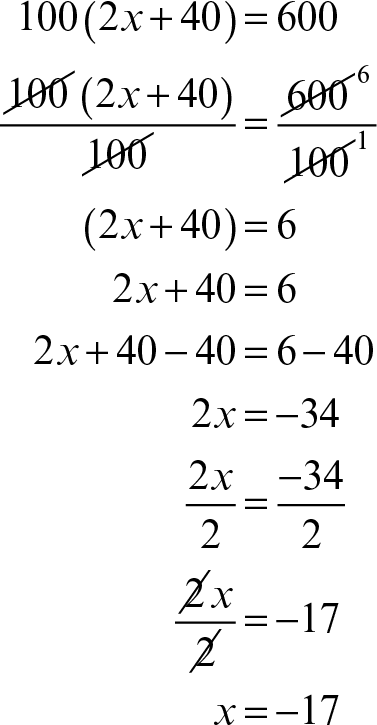

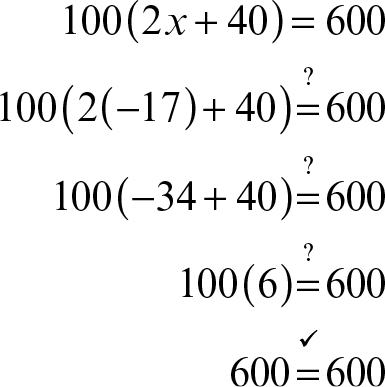

Using Shortcuts

As you become a skillful equation solver, you likely will modify the equation-solving process based on the particular equation you are trying to solve. For instance, you might divide both sides of an equation by a number before removing parentheses.

Here is an example.

Solve 100(2x + 40) = 600.

Looking at the equation, you see that both sides are divisible by 100. Dividing both sides of the equation by 100 first will simplify the calculations.

Real-World Problems

Many real-world problems can be modeled and solved using one-variable linear equations. To solve such problems, read the problem carefully. Look for a sentence that contains words or phrases such as “what is,” “what was,” “find,” “how many,” and “determine” to help you identify what you are to find. Let the variable represent this unknown quantity. (Tip: Be precise in specifying a variable. State its units, if any.) Then write and solve an equation that represents the facts given in the problem.

Here is an example.

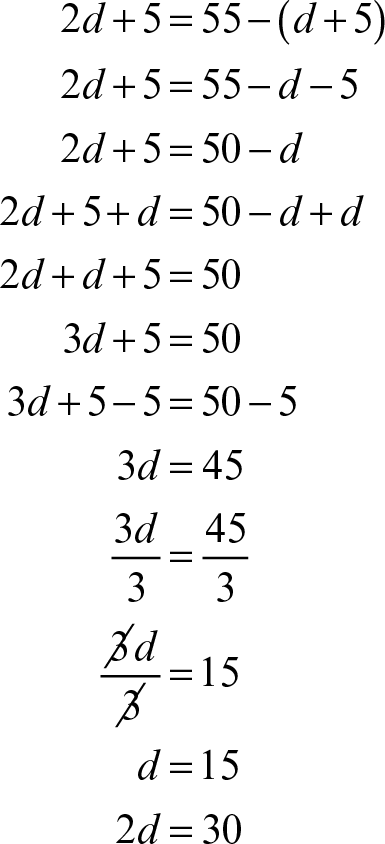

Jaidee is twice as old as Davon. In 5 years, Jaidee’s age will be 55 years minus Davon’s age. What is Jaidee’s age now?

You don’t know Jaidee’s age or Davon’s age now. Tip: For one-variable linear equations, when you have two unknowns and one of them is described in terms of the other one, designate the variable as the other one. For instance, Jaidee’s age now is described as “twice as old as Davon,” so designate the variable as Davon’s age now.

Let d = Davon’s age in years now, and 2d = Jaidee’s age in years now.

Make a chart to organize the information in the question.

| When? | Davon’s Age | Jaidee’s Age |

| Now | d | 2d |

| 5 years from now | d + 5 years | 2d + 5 years |

From the question, you know that Jaidee’s age 5 years from now is 55 years minus Davon’s age 5 years from now. Use the information in the chart to set up an equation to match the facts in the question.

2d + 5 years = 55 years − (d + 5 years)

Solve the equation, omitting the units for convenience.

Jaidee is 30 years old.

Tip: Make sure you answer the question asked. In this question, after you obtain Davon’s age now, calculate Jaidee’s age now.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank.

- An equation is a statement that two mathematical expressions are __________.

- A solution to an equation is a number that when substituted for the variable makes the equation __________.

- If the solution set is all real numbers, the equation is an __________.

- If the solution set is __________, the equation has no solution.

- Equations that have the same solution set are __________ equations.

- To solve a one-variable linear equation, you __________ what has been done to the variable .

- To keep an equation in balance, whatever you do to one side of the equation you must do to the __________ side of the equation.

- Solve for the variable.

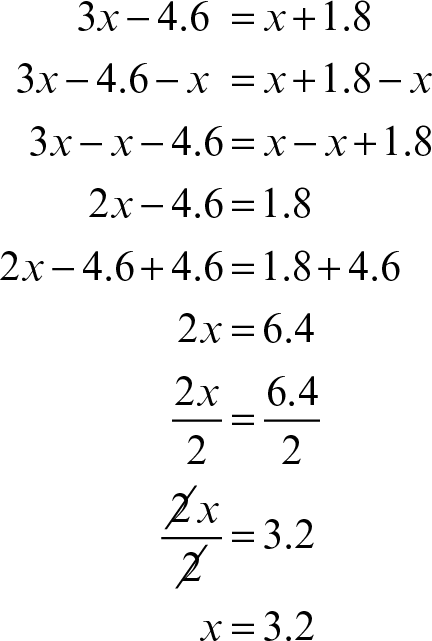

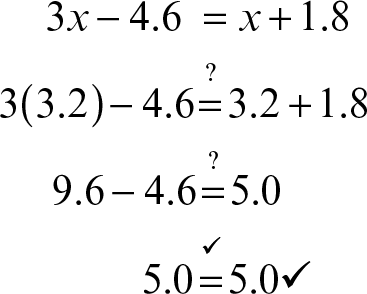

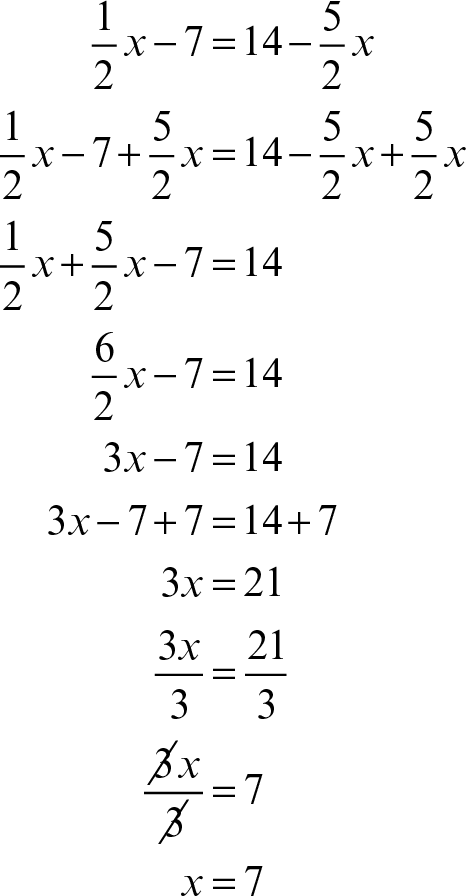

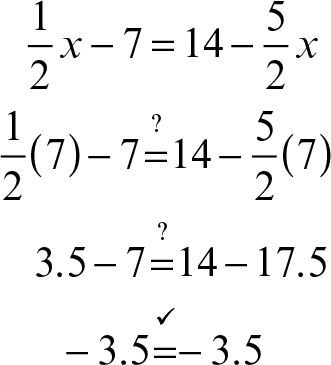

- 3x − 4.6 = x + 1.8

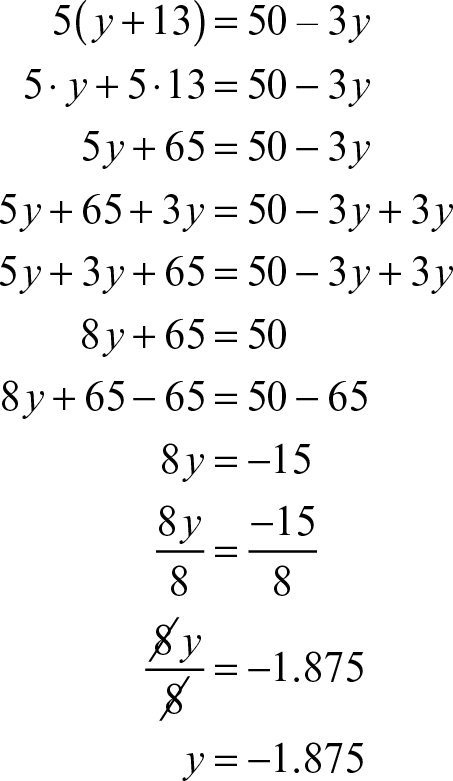

- 5(y + 13) = 50 − 3y

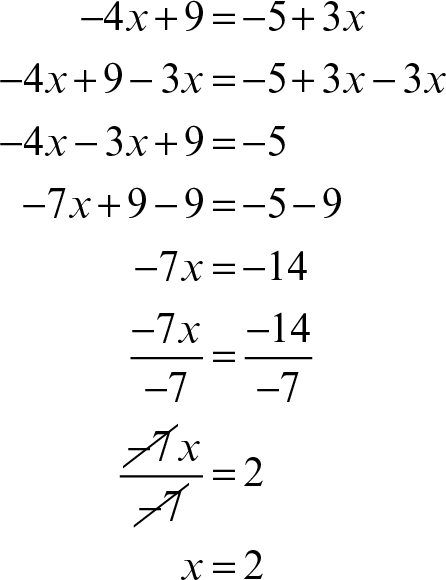

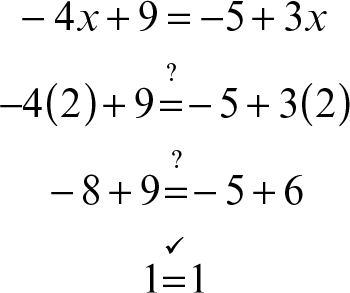

- −4x + 9 = −5 + 3x

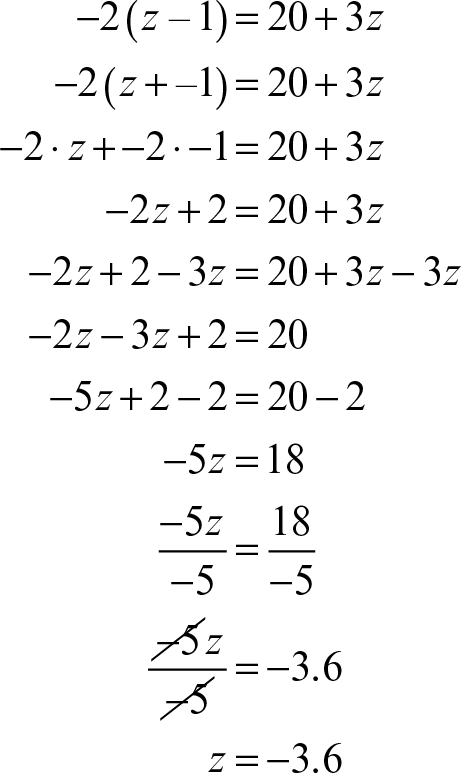

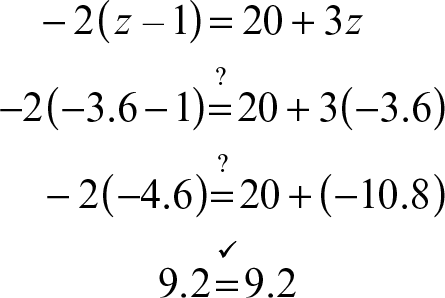

- −2(z − 1) = 20 + 3z

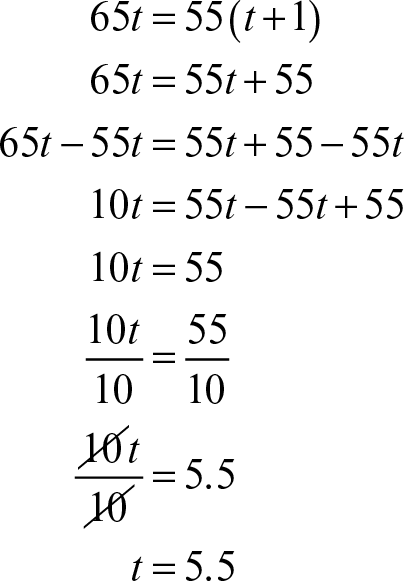

- A truck leaves a location traveling due east at a constant speed of 55 miles per hour. One hour later, a car leaves the same location traveling in the same direction at a constant speed of 65 miles per hour. If both vehicles continue in the same direction at their same respective speeds, how many hours will it take the car to catch up to the truck?

-

- equal

- true

- identity

- empty

- equivalent

- undo

- other

- Let t = the time in hours the car will travel before it catches up to the truck. Then t + 1 hour = the time in hours that the truck travels before the car catches up to it.

Make a chart to organize the information in the question.

Vehicle Rate (in mph) Time (in hours) Distance (in miles) car 65 t 65t truck 55 t + 1 55(t + 1)

Tip: Distance = Rate × Time.

Using the chart, write an equation to represent the facts given in the question.

When the car catches up to the truck, both vehicles have traveled the same distance. Thus, 65t = 55(t + 1).

The car will catch up to the truck in 5.5 hours.

Solving Equations of the Forms x2 = k and x3 = c

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.A.2B)

To solve an equation that has the form x2 = k or x3 = c, you find the solution set for the equation. Recall from the previous section that the set consisting of all solutions to an equation is the equation’s solution set.

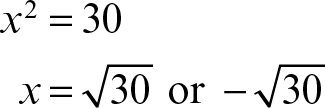

Solving Equations of the Form x2 = k

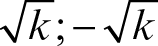

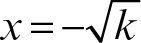

If k is a positive real number, the solution of the equation x2 = k is ![]() or

or  . The solution set contains two numbers,

. The solution set contains two numbers, ![]() and

and ![]() . The number

. The number ![]() is the positive number whose square is k. The number

is the positive number whose square is k. The number ![]() is the negative number whose square is k.

is the negative number whose square is k.

The two numbers, ![]() and

and ![]() , are the two square roots of k. If k is a perfect square, its square roots are rational. If k is not a perfect square, its square roots are irrational.

, are the two square roots of k. If k is a perfect square, its square roots are rational. If k is not a perfect square, its square roots are irrational.

Tip: See the section “Recognizing Rational and Irrational Numbers” in Chapter 1 for a list of square roots of perfect squares (page 8).

Here are examples.

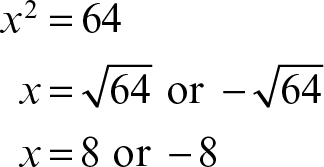

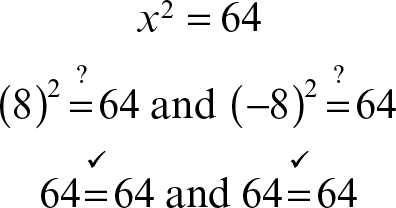

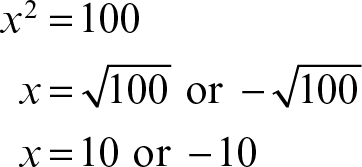

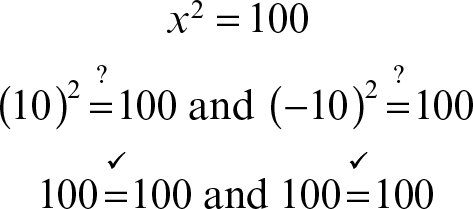

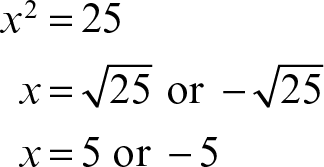

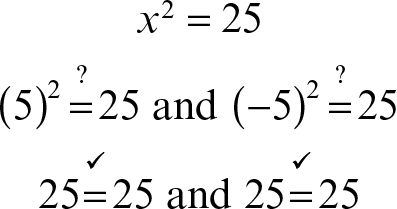

Solve x2 = 25.

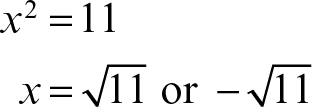

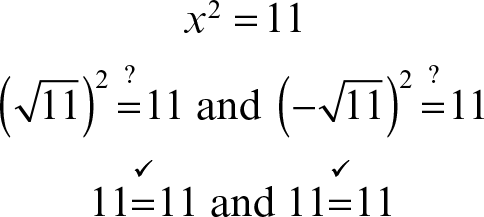

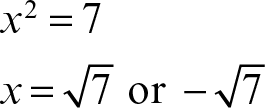

Solve x2 = 7.

Check:

Tip: ![]() is simply

is simply ![]() , an irrational number, because 7 is not a perfect square.

, an irrational number, because 7 is not a perfect square.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank(s).

- If k is a positive real number, the solution of the equation x2 = k is x = __________ or x = __________.

- If k is a positive real number, the solution set of x2 = k contains __________ (one real number, two real numbers, three real numbers).

- If k is a perfect square, its square roots are __________ (irrational, rational). If k is not a perfect square, its square roots are __________ (irrational, rational).

- Solve the equation.

- x2 = 64

- x2 = 30

- x2 = 100

- x2 = 11

Solutions

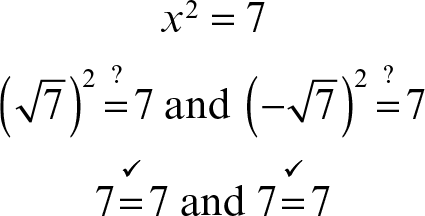

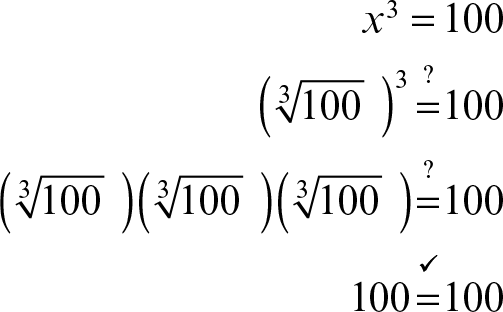

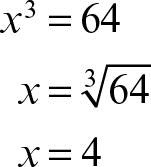

Solving Equations of the Form x3 = c

If c is a positive real number, the solution of the equation x3 = c is ![]() , where

, where ![]() denotes the “cube root of c.” The solution set contains one real number,

denotes the “cube root of c.” The solution set contains one real number, ![]() . The number

. The number ![]() is the number whose cube is c. If c is a perfect cube, its cube root is rational. If c is not a perfect cube, its cube root is irrational.

is the number whose cube is c. If c is a perfect cube, its cube root is rational. If c is not a perfect cube, its cube root is irrational.

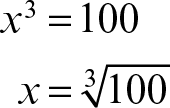

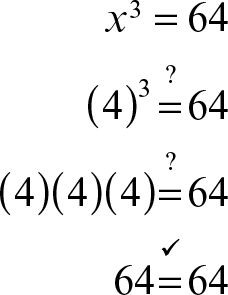

Solve x3 = 8.

Check:

Solve x3 = 100.

Check:

Tip: ![]() is simply

is simply ![]() , an irrational number, because 100 is not a perfect cube.

, an irrational number, because 100 is not a perfect cube.

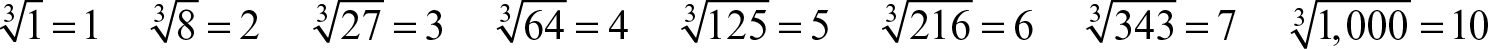

You will find it helpful to memorize the following cube roots of perfect cubes.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank(s)

- If c is a positive real number, the solution of the equation x3 = c is x = __________.

- The solution set of x3 = c contains __________ (one real number, two real numbers, three real numbers).

- If c is a perfect cube, its cube root is __________ (irrational, rational). If c is not a perfect cube, its cube root is __________ (irrational, rational).

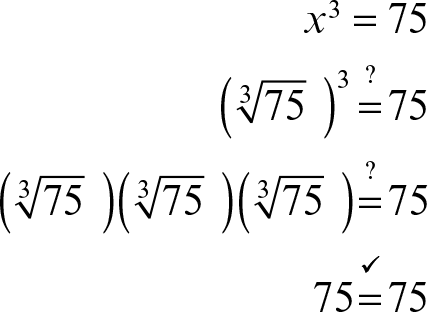

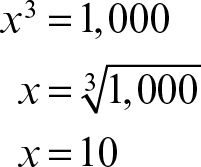

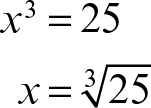

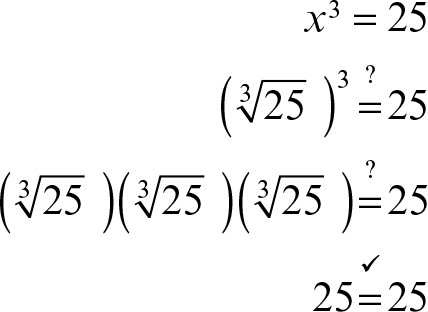

- Solve the equation.

- x3 = 64

- x3 = 75

- x3 = 1,000

- x3 = 25

-

- one real number

- rational; irrational

-

Check:

Check:

Check:

Check:

Graphing Two-Variable Linear Equations of the Form y = mx + b

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.B.5, CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.B.6, CCSS.Math.Content.8.F.A.3)

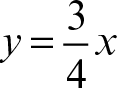

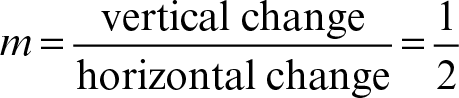

The equation y = mx + b is a linear equation in two variables. The graph of y = mx + b is a line. The slope of the line is the coefficient m. The number b is the y-coordinate of the point where the graph intersects the y-axis. It is the y-intercept.

Here is an example.

Understanding the Slope and y-Intercept

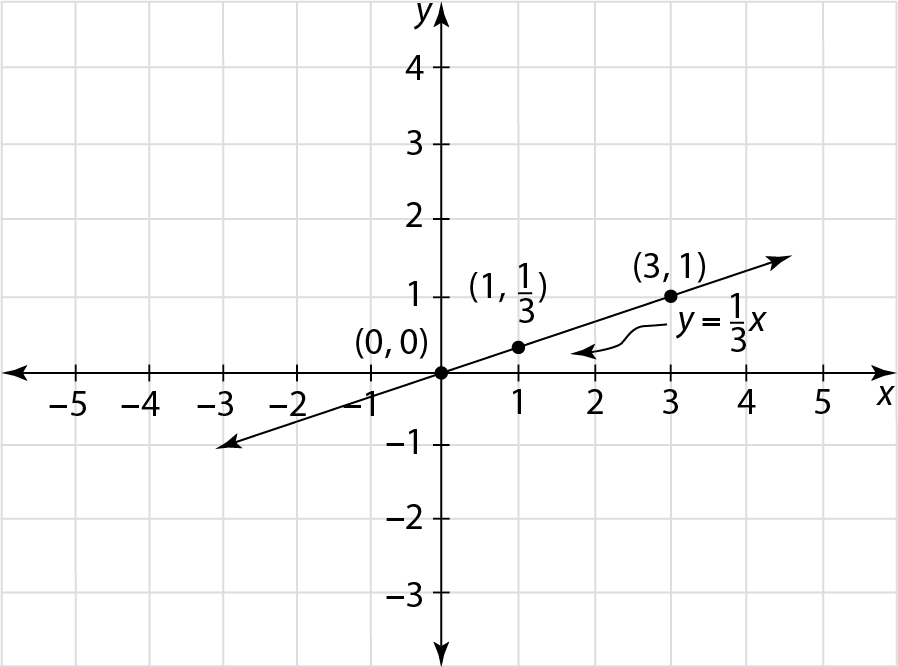

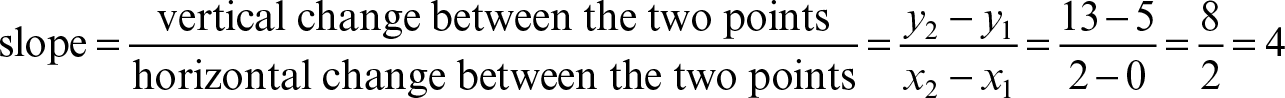

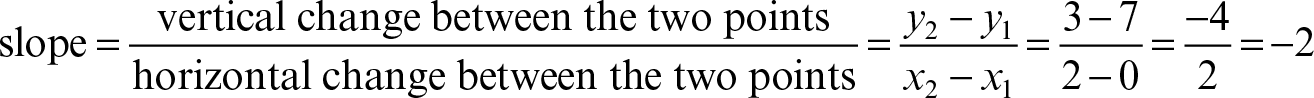

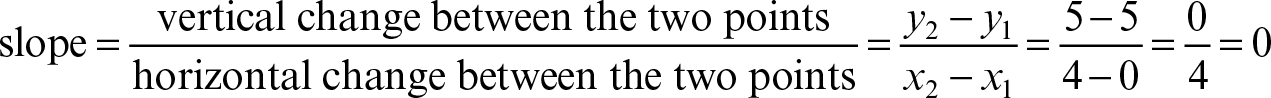

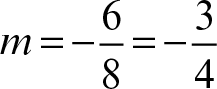

The slope m of a line tells you important information about the line. The slope is its rate of change. For any two points on the line,

Tip: The vertical change between two points on a line is the rise between the points. The horizontal change between two points on a line is the run between the points.

The slope of a line is the same no matter which two points on the line you choose.

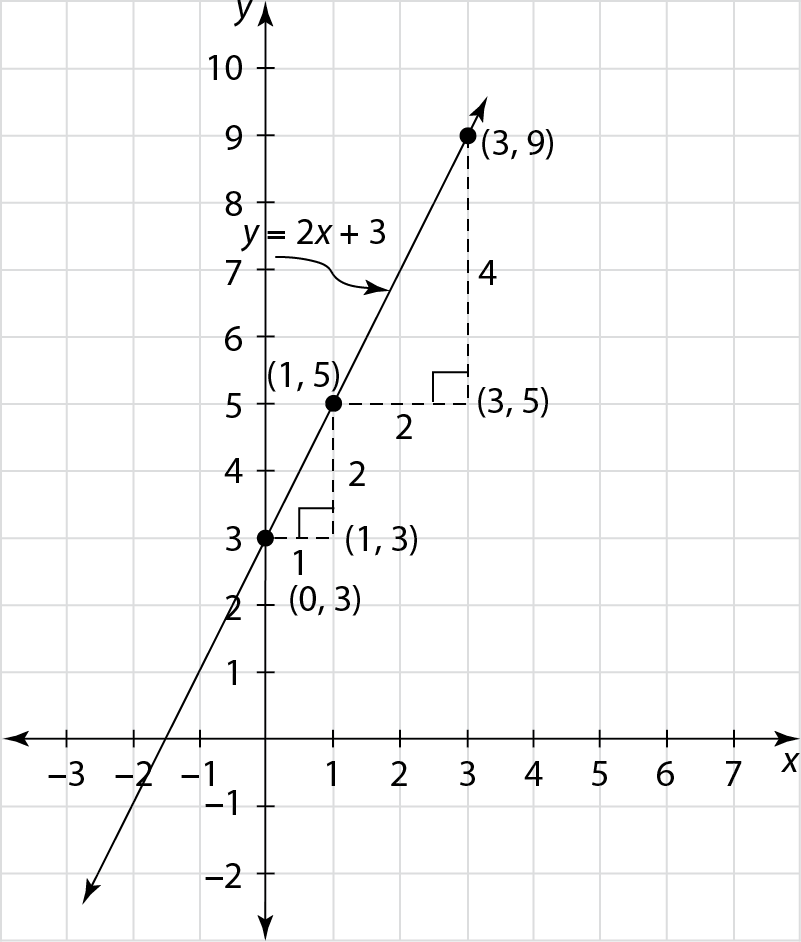

Here is an example.

On the graph of the line y = 2x + 3, the slope between the points (0, 3) and (1, 5) is

Similarly, the slope between the points (1, 5) and (3, 9) is

The slope is the same whether you use (0, 3) and (1, 5) or (1, 5) and (3, 9). The rate of change for the line is ![]() . For every 1-unit change horizontally, there is a 2-unit change vertically.

. For every 1-unit change horizontally, there is a 2-unit change vertically.

Tip: The order in which you subtract is important. Put y2 first in the numerator and x2 first in the denominator.

The slope describes the steepness or slant of the line. If m is positive, the line slants up from left to right. If m is negative, the line slants down from left to right. If m = 0, the line is horizontal with no slant. The greater the absolute value of m, the steeper the line and the faster the rate of change.

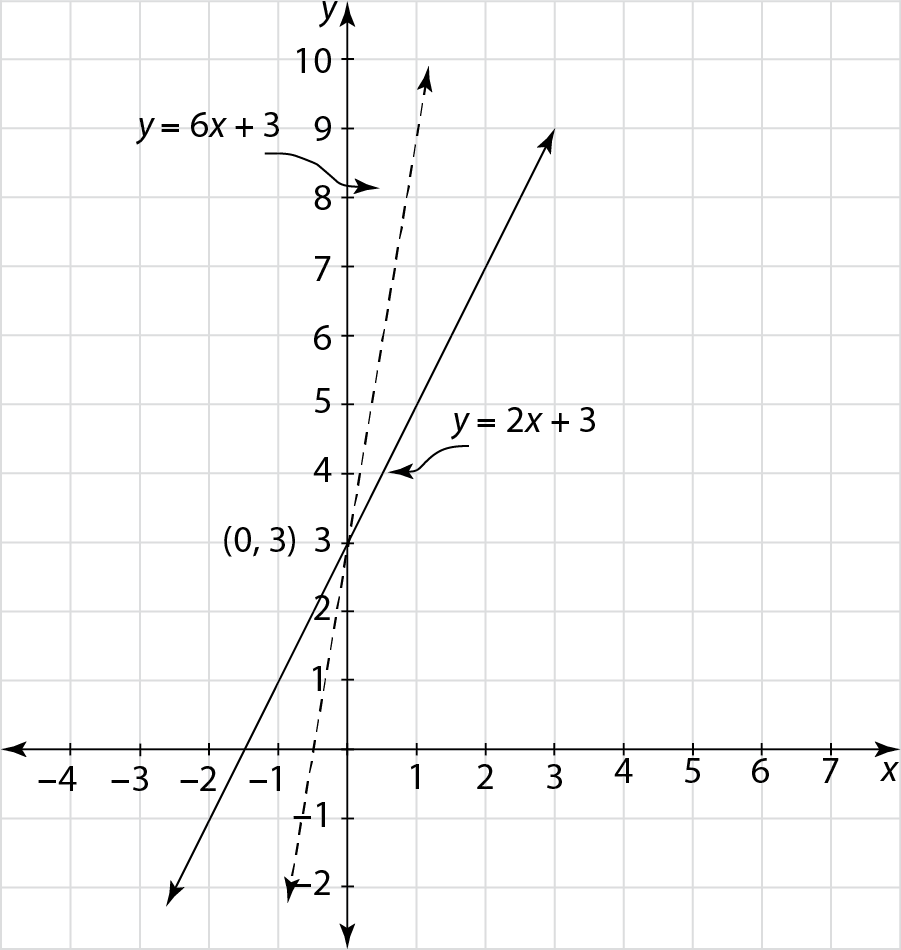

For example, as shown below, the graph of y = 6x + 3 is much steeper than the graph of y = 2x + 3.

The slope of y = 6x + 3 is three times as steep as that of y = 2x + 3. The graph of y = 6x + 3 is changing three times as fast as the graph of y = 2x + 3 because its slope is three times as large (6 = 2 × 3).

The y-intercept also provides useful information. It tells you what happens when the x-value is zero. If zero is the starting value for the variable x, the y-intercept lets you know whether the initial y-value is zero or perhaps some other value.

Tip: When the y-intercept is 0, the line passes through the origin.

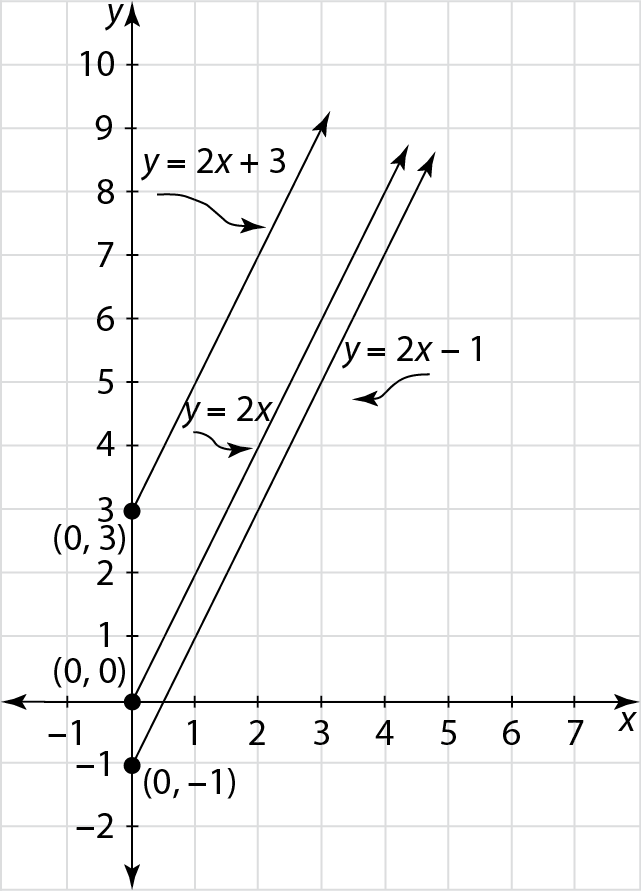

For instance, suppose the starting value of the variable x is zero for the graphs of y = 2x + 3, y = 2x – 1, and y = 2x as shown below. Look at the y-intercept of each line. Although the three lines have the same slope, each has a different y-value corresponding to x = 0.

- Fill in the blank.

- The graph of the equation y = 3x + 5 is a __________.

- The slope of a line is its __________ of change.

- The slope of

is __________.

is __________. - The y-intercept of

is __________.

is __________.

- Write the equation of the line that has the given slope and y-intercept.

- slope 2; y-intercept 10

- slope

; y-intercept –5

; y-intercept –5 - slope –4; y-intercept 7

- slope

; y-intercept 0

; y-intercept 0

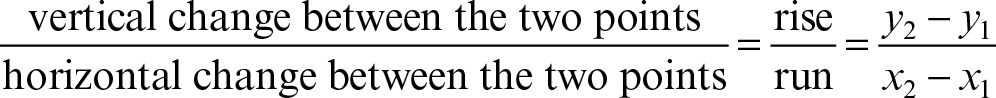

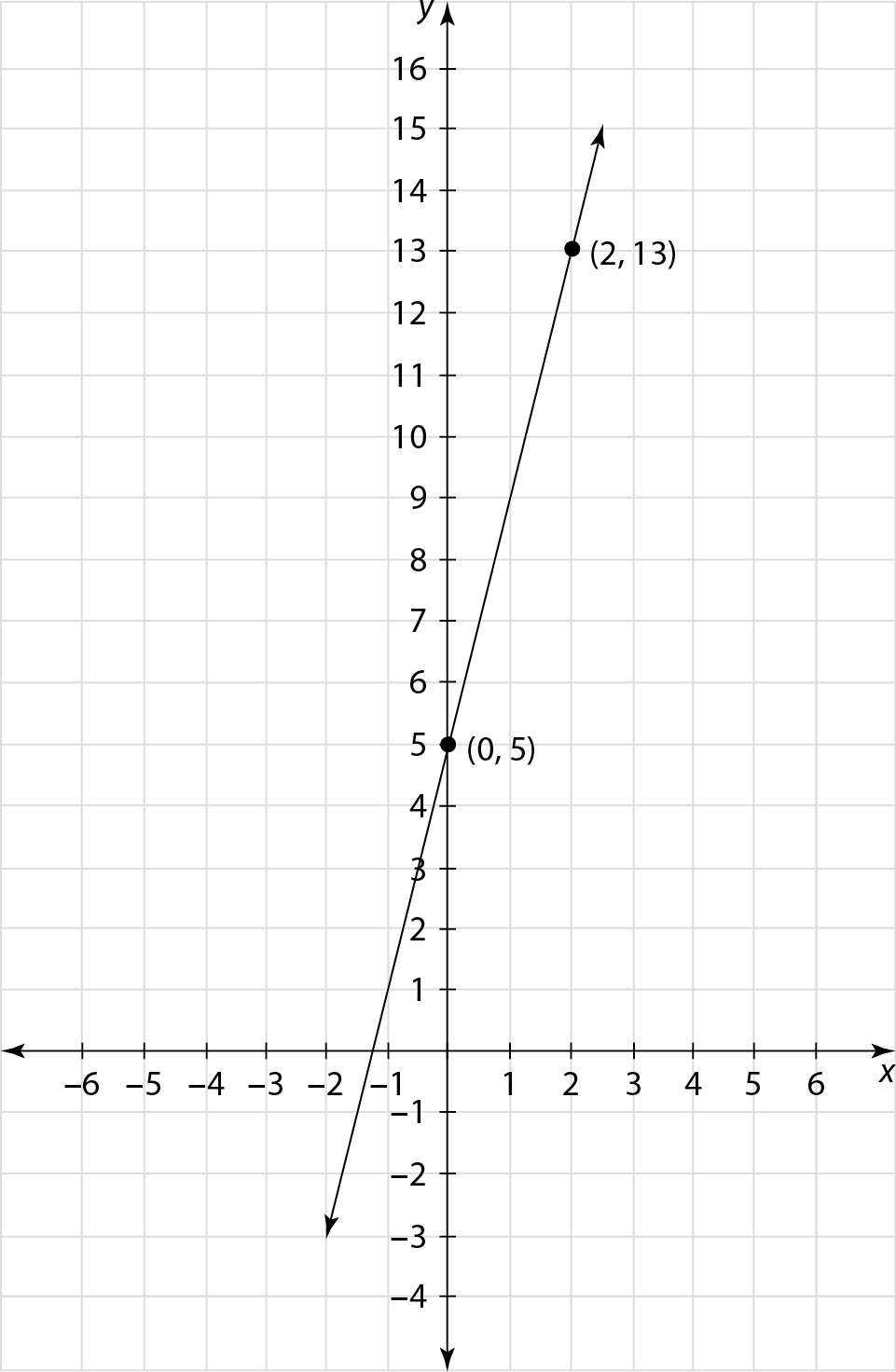

- Find the slope and y-intercept of the line shown.

-

- line

- rate

- 4

-

- y = 2x + 10

- y = –4x + 7

-

- The points (0, 5) and (2, 13) are two points on the line.

; y-intercept = 5

; y-intercept = 5 - The points (0, 7) and (2, 3) are two points on the line.

; y-intercept = 7

; y-intercept = 7 - The points (0, 5) and (4, 5) are two points on the line.

; y-intercept = 5

; y-intercept = 5

- The points (0, 5) and (2, 13) are two points on the line.

Graphing y = mx + b

There are two common methods for graphing y = mx + b. Here are examples of each.

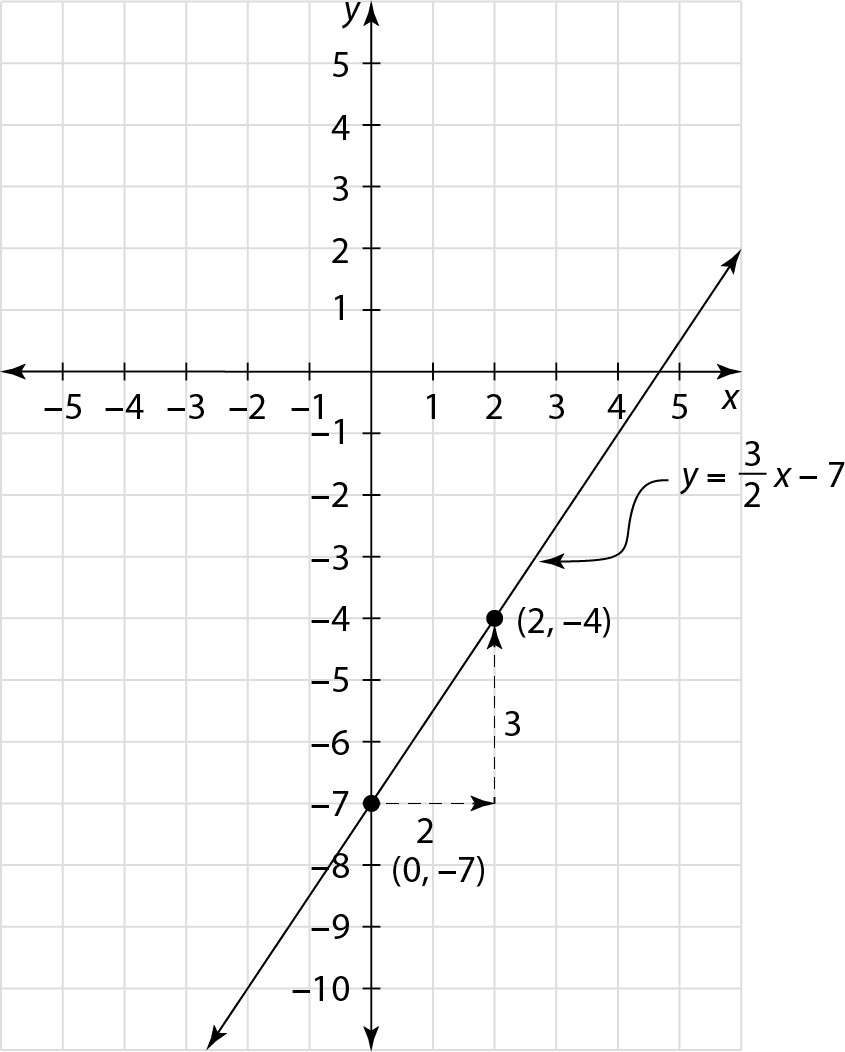

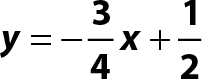

Graph  .

.

Method 1:

Step 1. Set up an x-y table and determine two ordered pairs that make the equation true. Tip: Pick convenient values for x, and then compute the corresponding y values.

| x |  |

| 0 |  |

| 2 |  |

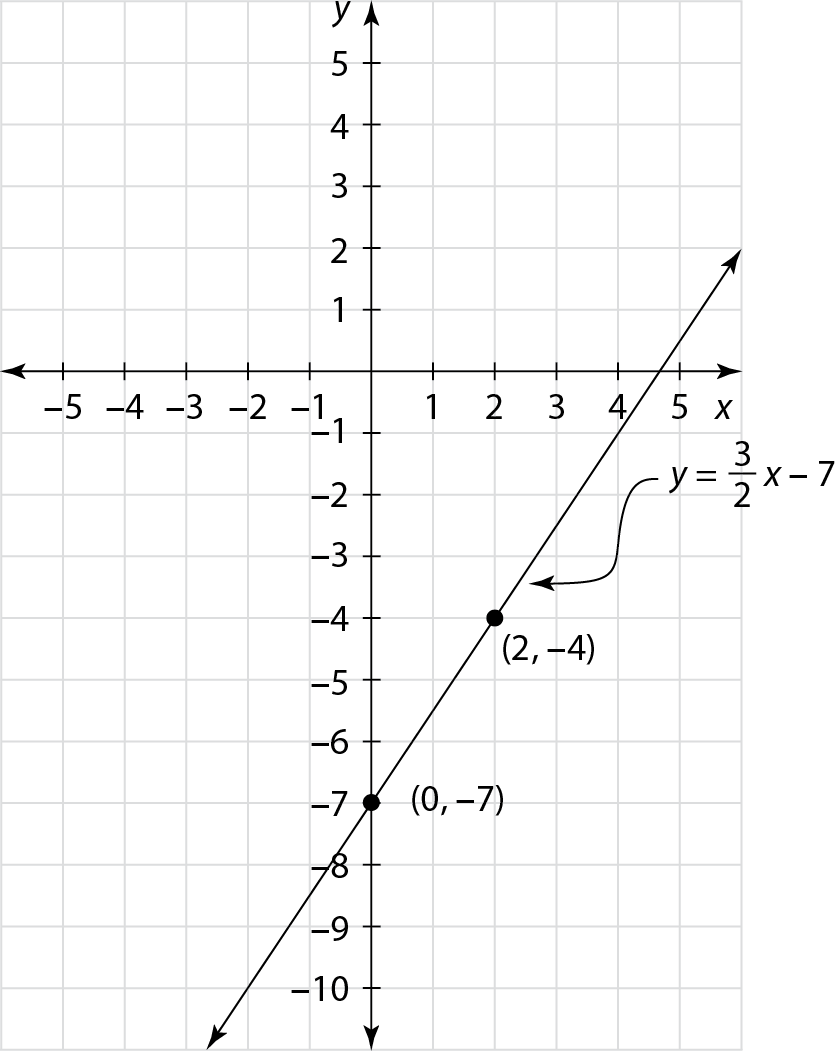

Step 2. Graph the ordered pairs from Step 1. Connect them with a line extending in both directions.

Method 2:

Step 1. Identify the slope m of the line (the coefficient of x) and b, the y-intercept (the constant).

; y-intercept b = –7

; y-intercept b = –7Step 2. Graph the point (0, b). Use the slope to find a second point. Connect the two points with a line extending in both directions.

(0, b) = (0, –7). Given  , when x changes 2 units, y changes 3 units. Start at (0, –7). Move 2 units right, and from there move 3 units up to locate a second point. Connect the two points with a line extending in both directions.

, when x changes 2 units, y changes 3 units. Start at (0, –7). Move 2 units right, and from there move 3 units up to locate a second point. Connect the two points with a line extending in both directions.

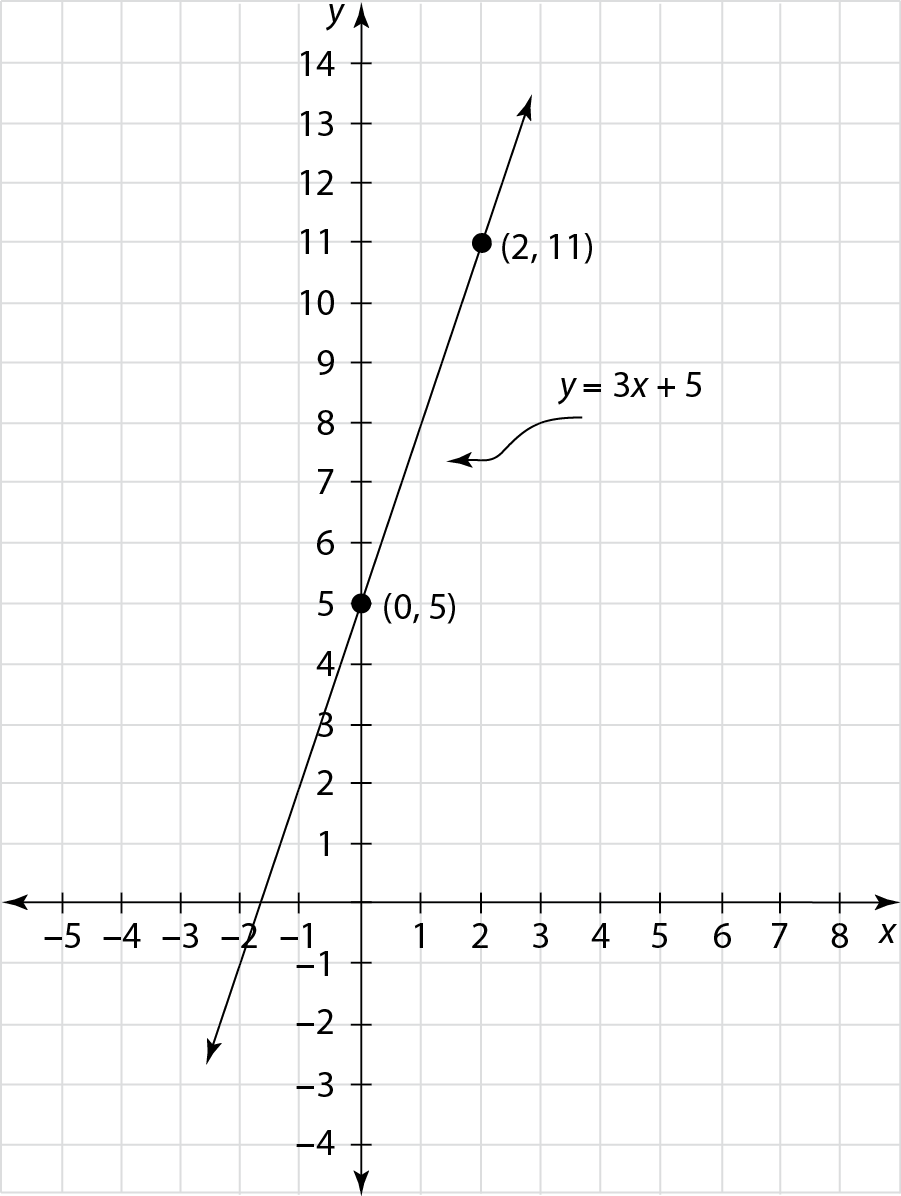

- Graph using Method 1.

- y = 3x + 5

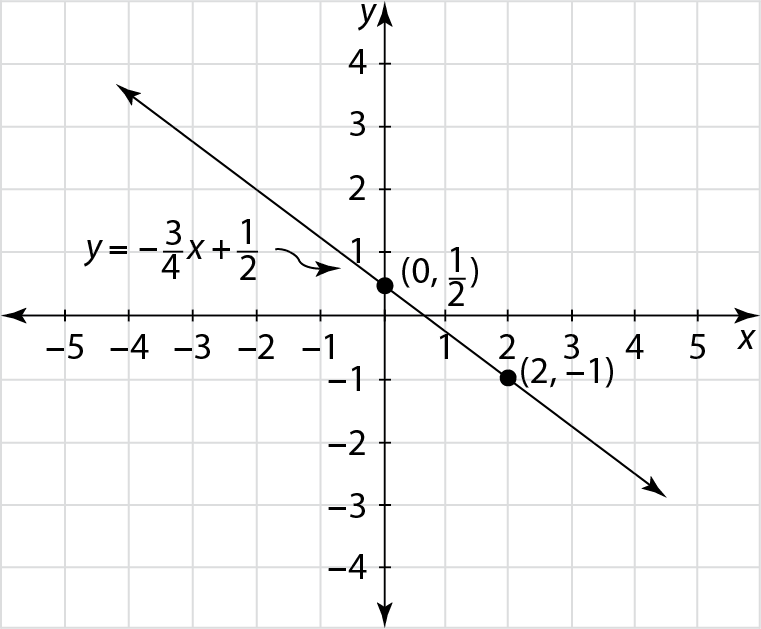

- Graph using Method 2.

- y = 4x – 9

Solutions

-

- Step 1. Set up an x-y table and determine two ordered pairs that make the equation true.

x y = 3x + 5 0 5 2 11 Step 2. Graph the ordered pairs from Step 1. Connect them with a line extending in both directions.

- Step 1. Set up an x-y table and determine two ordered pairs that make the equation true.

x

0

2 -1 Step 2. Graph the ordered pairs from Step 1. Connect them with a line extending in both directions.

- Step 1. Set up an x-y table and determine two ordered pairs that make the equation true.

-

- Step 1. Identify the slope m of the line (the coefficient of x) and b, the y-intercept (the constant).

slope m = 4; y-intercept b = –9

Step 2. Graph the point (0, –9). Use the slope to find a second point. Connect the two points with a line extending in both directions.

Given

, when x changes 1 unit, y changes 4 units. Start at (0, –9). Move 1unit right, and from there move 4 units up to locate a second point. Connect the two points with a line extending in both directions.

, when x changes 1 unit, y changes 4 units. Start at (0, –9). Move 1unit right, and from there move 4 units up to locate a second point. Connect the two points with a line extending in both directions.

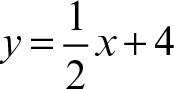

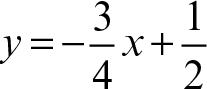

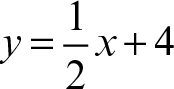

- Step 1. Identify the slope m of the line (the coefficient of x) and b, the y-intercept (the constant).

slope

; y-intercept b = 4

; y-intercept b = 4Step 2. Graph the point (0, 4). Use the slope to find a second point. Connect the two points with a line extending in both directions.

Given

, when x changes 2 units, y changes 1 unit. Start at (0, 4). Move 2units right, and from there move 1 unit up to locate a second point. Connect the two points with a line extending in both directions.

, when x changes 2 units, y changes 1 unit. Start at (0, 4). Move 2units right, and from there move 1 unit up to locate a second point. Connect the two points with a line extending in both directions.

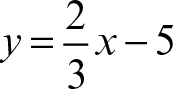

- Step 1. Identify the slope m of the line (the coefficient of x) and b, the y-intercept (the constant).

Graphing and Comparing Proportional Relationships

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.B.6, CCSS.Math.Content.8.F.A.2)

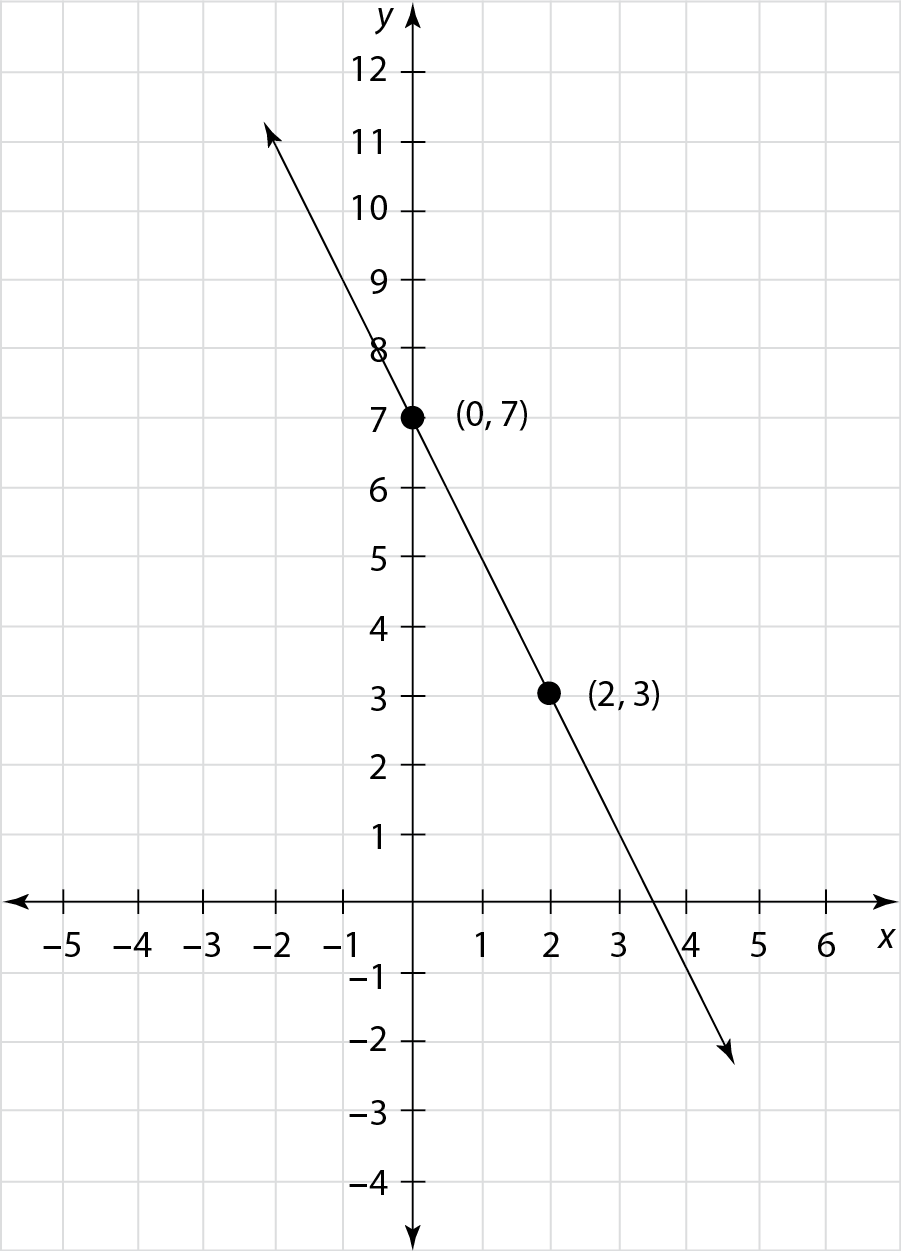

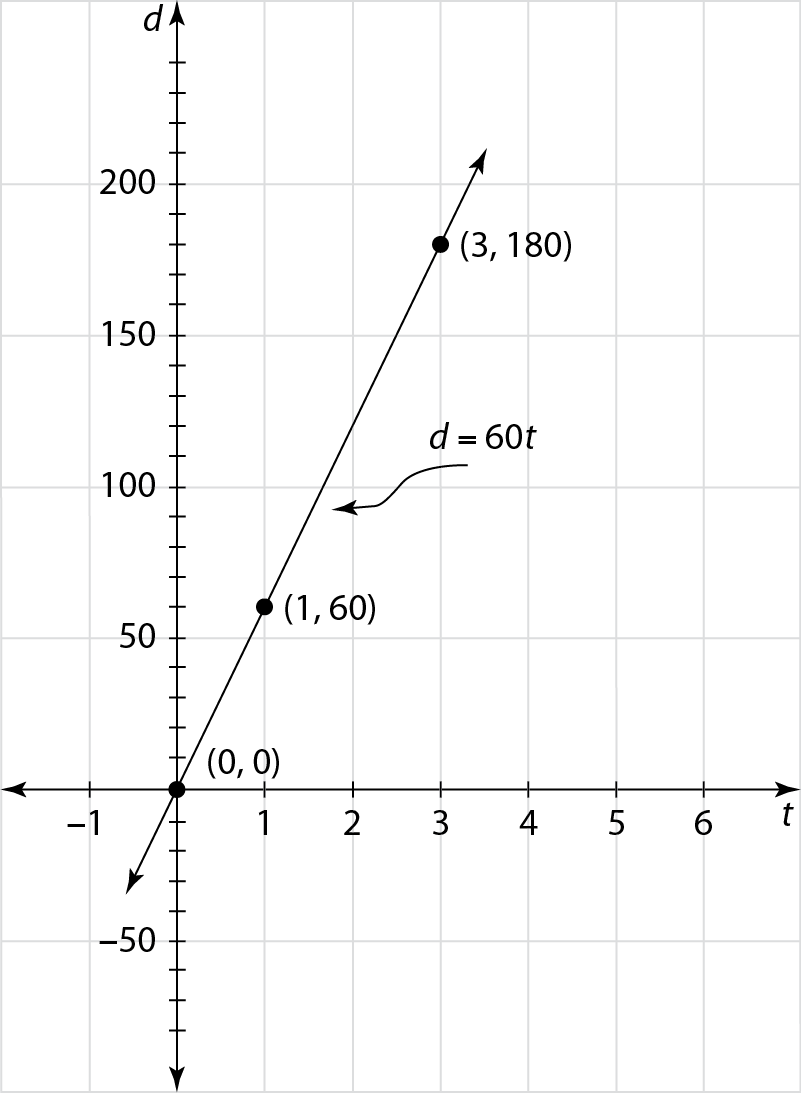

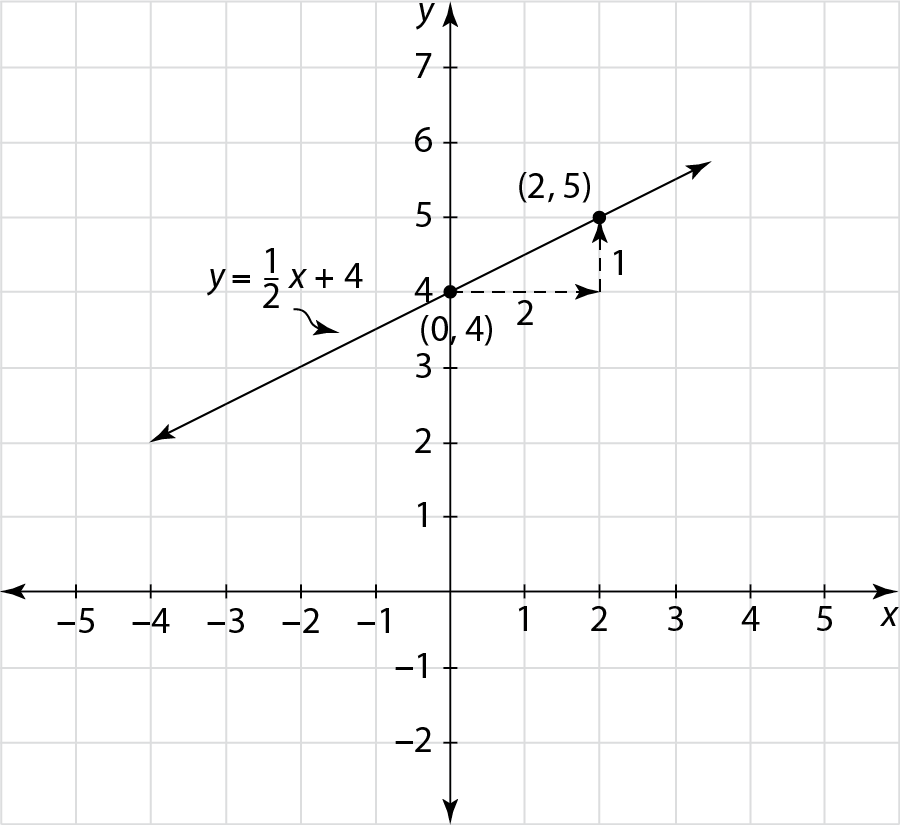

When the y-intercept is zero, the equation y = mx + b has the form y = mx. The graph of the equation y = mx is a proportional relationship. The slope m is the unit rate of the proportional relationship. Graph proportional relationships using Method 1 or Method 2 of the previous section.

Here is an example.

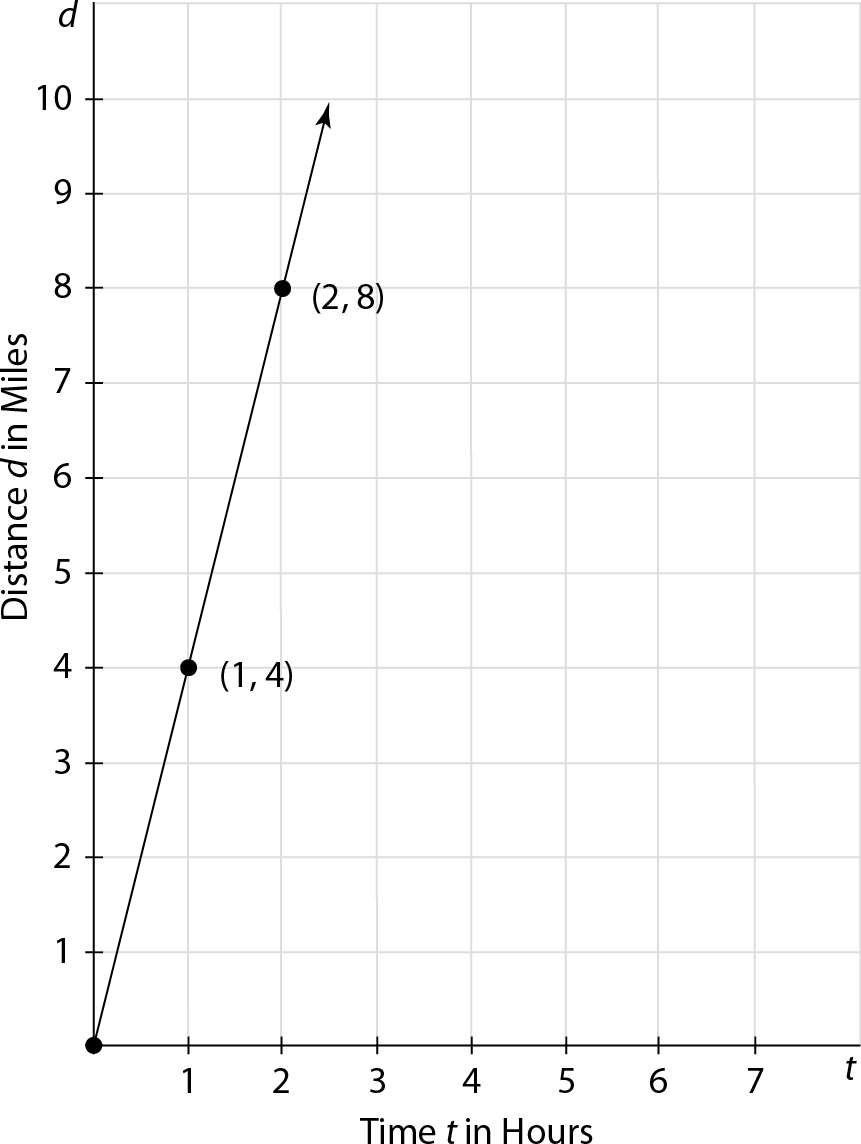

Rafael walks at a constant rate of 4 miles per hour. The equation d = 4t represents the proportional relationship between the distance, d (in miles), traveled in time, t (in hours). Graph d = 4t.

Graph d = 4t using Method 2 of the previous section. Tip: In the graph of d = 4t, t is the horizontal axis and d is the vertical axis.

Step 1. Identify the slope m of the line and b, the d-intercept.

slope ![]() ; d-intercept b = 0

; d-intercept b = 0

Step 2. Graph the point (0, 0) and use the slope to find a second point. Connect the two points with a line.

Given  , for every 1 hour change in time t, the distance d changes 4 miles. Start at(0, 0). Move 1 unit right, and from there move 4 units up to locate a second point. Connect the two points with a ray extending away from the origin (because both time and distance are nonnegative).

, for every 1 hour change in time t, the distance d changes 4 miles. Start at(0, 0). Move 1 unit right, and from there move 4 units up to locate a second point. Connect the two points with a ray extending away from the origin (because both time and distance are nonnegative).

Compare the rates of change of two proportional relationships by identifying and comparing the unit rates (slopes) of their equations. The proportional relationship that has the greater unit rate has the faster rate of change. Here is an example.

Compare the two situations to determine who walks faster: Rafael or Bartolo. Justify your answer.

Situation 1: The graph shows the proportional relationship between the distance, d (in miles), traveled in time, t (in hours), by Rafael.

Situation 2: Bartolo walks at a constant rate. The table shows the proportional relationship between the distance, d (in miles), traveled in time, t (in hours), by Bartolo.

| Time, t (in hours) | Distance, d (in miles) |

| 1.4 | |

| 1.75 | |

| 5.25 | |

| 11.2 |

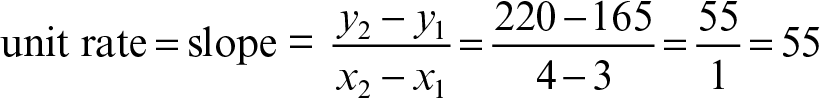

Situation 1: Calculate Rafael’s unit rate of miles per hour walking speed. Using the two points shown, calculate the unit rate (slope) of the graph.

Rafael’s unit rate of miles per hour walking speed is 4.

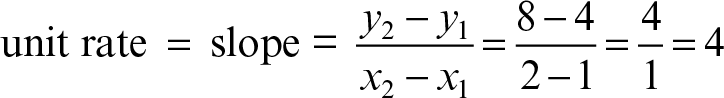

Situation 2: Calculate Bartolo’s unit rate of miles per hour walking speed.

Bartolo’s unit rate of miles per hour walking speed is 3.5.

Because Rafael’s unit rate of 4 is greater than Bartolo’s unit rate of 3.5, Rafael walks faster than Bartolo.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank.

- The graph of the equation y = mx is a __________ relationship.

- The slope m of y = mx is its __________ __________ (two words).

- Graph the proportional relationship.

- y = 2.5x

- c = 6n

- d = 60t

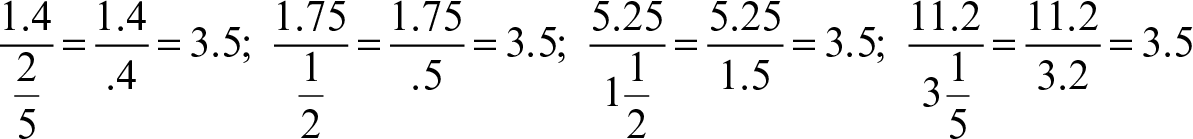

- Compare the proportional relationships in the two situations to determine which vehicle is traveling faster: the car or the truck.

Situation 1: A car is traveling at a constant rate of 65 miles per hour. The equation d = 65t represents the proportional relationship between the distance, d (in miles), traveled in time, t (in hours), by the car.

Situation 2: The graph shows the proportional relationship between the distance d (in miles), a truck travels in time t (in hours).

Solutions

-

- proportional

- unit rate

-

- Situation 1: The car’s unit rate of miles per hour is 65.

Situation 2: Calculate the truck’s unit rate of miles per hour. Using the points (3, 165) and (4, 220) shown on the graph, calculate the unit rate (slope) of the graph.

Because the car’s unit rate of 65 is greater than the truck’s unit rate of 55, the car is traveling at a faster speed.

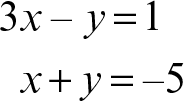

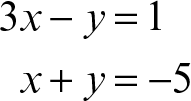

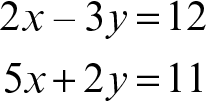

Solving Pairs of Simultaneous Two-Variable Linear Equations

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.C.8.A, CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.C.8.B, CCSS.Math.Content.8.EE.C.8.C)

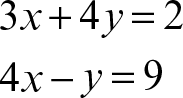

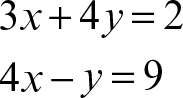

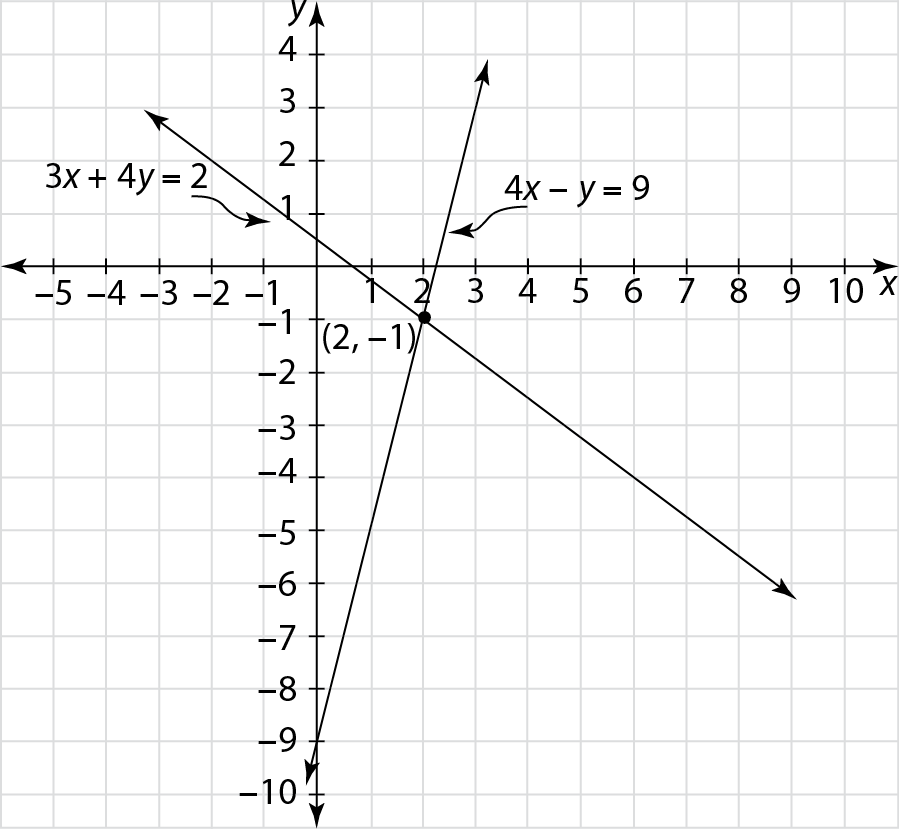

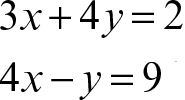

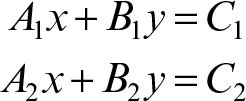

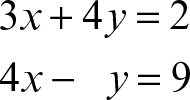

The standard form of a two-variable linear equation is Ax + By = C, where A and B are not both zero. For example, 3x + 4y = 2 and 4x – y = 9 are linear equations in standard form.

A set of two linear equations, each with the same two variables, is a system when the two equations are considered simultaneously, meaning at the same time.

Here is an example of a system of two linear equations with variables x and y.

To solve a system of two equations in two variables, find an ordered pair of values; for example, an x-value paired with a corresponding y-value, written as (x, y), that makes both equations true at the same time. An ordered pair that makes an equation in two variables true satisfies the equation. When an ordered pair makes both equations in a system of two equations true, the ordered pair satisfies the system.

The system has a solution when the two equations in the system are both satisfied by at least one ordered pair. A system that has a solution is consistent. A system that has no solution is inconsistent. The solution set is the collection of all solutions. There are three possibilities: the system has exactly one solution, infinitely many solutions, or no solution.

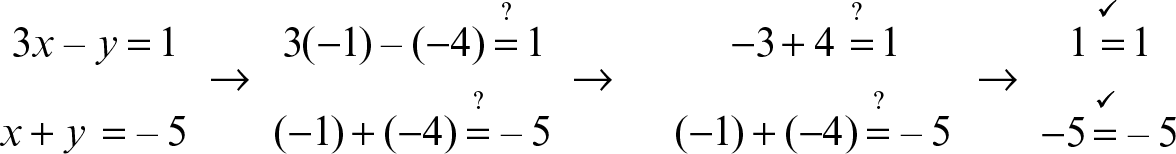

Determining Whether an Ordered Pair Satisfies a System of Two Linear Equations

To determine whether an ordered pair satisfies a system of two equations, check whether the ordered pair satisfies both equations in the system. Do this by plugging the x and y values of the ordered pair into the two equations. Be careful to enclose in parentheses the values that you put in. Here is an example.

(a) Determine whether the ordered pair (1, –2) satisfies the system.

(b) Determine whether the ordered pair (2, –1) satisfies the system.

(a) First, check whether (1, –2) satisfies 3x + 4y = 2.

On the LS of the equation, substitute 1 for x and –2 for y. Then evaluate and compare the result to the RS of the equation.

3x + 4y = 3(1) + 4(–2) = 3 + –8 = –5

The RS of the equation is 2. Because –5 ≠ 2, (1, –2) does not satisfy 3x + 4y = 2. Therefore, (1, –2) does not satisfy the given system because it fails to satisfy one of the equations in the system.

(b) First, check whether (2, –1) satisfies 3x + 4y = 2.

On the LS of the equation, substitute 2 for x and –1 for y. Then evaluate and compare the result to the RS of the equation.

3x + 4y = 3(2) + 4(–1) = 6 + –4 = 2

The RS of the equation is also 2, so (2, –1) satisfies 3x + 4y = 2.

Next, check whether (2, –1) satisfies 4x – y = 9.

On the LS of the equation, substitute 2 for x and –1 for y. Then evaluate and compare the result to the RS of the equation.

4x – y = 4(2) – (–1) = 8 + 1 = 9

The RS of the equation is also 9, so (2, –1) satisfies 4x – y = 9. Therefore, (2, –1) satisfies the given system because it satisfies both equations in the system.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank(s).

- A set of two linear equations, each with the same two variables, is a system when the two equations are considered __________.

- When an ordered pair makes both equations in a system of two equations true, the ordered pair __________ the system.

- A system that has a solution is __________ (consistent, inconsistent).

- A system that has no solution is __________ (consistent, inconsistent).

- There are three possibilities for the solution set of a system: the system has exactly __________ solution, __________ many solutions, or __________ solution.

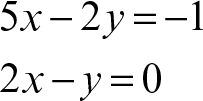

- Given the system

- Determine whether the ordered pair (1, 3) satisfies the system.

- Determine whether the ordered pair (–1, –2) satisfies the system.

-

- simultaneously

- satisfies

- consistent

- inconsistent

- one; infinitely; no

- First, check whether (1, 3) satisfies 5x – 2y = –1.

On the LS of the equation, substitute 1 for x and 3 for y. Then evaluate and compare the result to the RS of the equation.

5x – 2y = 5(1) – 2(3) = 5 – 6 = –1

The RS of the equation is also –1, so (1, 3) satisfies 5x – 2y = –1.

Next, check whether (1, 3) satisfies 2x – y = 0.

On the LS of the equation, substitute 1 for x and 3 for y. Then evaluate and compare the result to the RS of the equation.

2x – y = 2(1) – (3) = 2 – 3 = –1

The RS of the equation is 0. Because –1 ≠ 0, (1, 3) does not satisfy 2x – y = 0. Therefore, (1, 3) does not satisfy the given system because it fails to satisfy one of the equations in the system.

- First, check whether (–1, –2) satisfies 5x – 2y = –1.

On the LS of the equation, substitute –1 for x and –2 for y. Then evaluate and compare the result to the RS of the equation.

5x – 2y = 5(–1) – 2(–2) = –5 + 4 = –1

The RS of the equation is also –1, so (–1, –2) satisfies 5x – 2y = –1.

Next, check whether (–1, –2) satisfies 2x – y = 0.

On the LS of the equation, substitute –1 for x and –2 for y. Then evaluate and compare the result to the RS of the equation.

2x – y = 2(–1) – (–2) = –2 + 2 = 0

The RS of the equation is also 0, so (–1, –2) satisfies 2x – y = 0. Therefore, (–1, –2) satisfies the given system because it satisfies both equations in the system.

- First, check whether (1, 3) satisfies 5x – 2y = –1.

Interpreting Systems of Two Linear Equations Geometrically

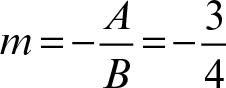

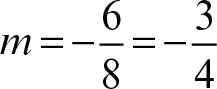

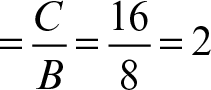

In the coordinate plane, the graphs of the two equations in a system of two linear equations are two lines. The graph of Ax + By = C is a line with slope ![]() and y-intercept

and y-intercept ![]() (provided B ≠ 0). For the two equations, there are three possibilities that can occur. The three possibilities are exactly one solution, infinitely many solutions, or no solution. If the system is consistent and has exactly one solution, the two lines intersect in exactly one point in the plane. The point of intersection is the solution to the system.

(provided B ≠ 0). For the two equations, there are three possibilities that can occur. The three possibilities are exactly one solution, infinitely many solutions, or no solution. If the system is consistent and has exactly one solution, the two lines intersect in exactly one point in the plane. The point of intersection is the solution to the system.

Graph the system  .

.

The equation 3x + 4y = 2 has slope  and y-intercept

and y-intercept  . The equation 4 x – y = 9 has slope

. The equation 4 x – y = 9 has slope  and y-intercept

and y-intercept  . Use Method 1 or Method 2 from the section “Graphing y = mx + b” earlier in this chapter to graph the two equations in the same coordinate plane.

. Use Method 1 or Method 2 from the section “Graphing y = mx + b” earlier in this chapter to graph the two equations in the same coordinate plane.

The two lines intersect in exactly one point (2, –1). This point is the solution to the system  .

.

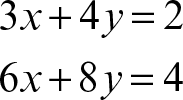

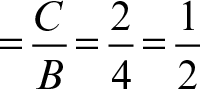

If the system is consistent and has infinitely many solutions, the two lines are coincident (that is, they have all points in common).

Here is an example.

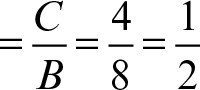

Graph the system  .

.

The equation 3x + 4y = 2 has slope  and y-intercept

and y-intercept  . The equation 6 x + 8y = 4 has slope

. The equation 6 x + 8y = 4 has slope  and y-intercept

and y-intercept  . The two lines representing the equations have the same slope and the same y-intercept, so their graphs will lie on top of each other. Use Method 2 from the section “Graphing y = mx + b” earlier in this chapter to graph the two equations in the same coordinate plane.

. The two lines representing the equations have the same slope and the same y-intercept, so their graphs will lie on top of each other. Use Method 2 from the section “Graphing y = mx + b” earlier in this chapter to graph the two equations in the same coordinate plane.

Notice that when both sides of the equation 6x + 8y = 4 are divided by 2, the result is 3x + 4y = 2. Thus, 3x + 4y = 2 and 6x + 8y = 4 are equivalent equations with the same solutions. All points on the line that has slope ![]() and y-intercept

and y-intercept ![]() will satisfy both equations at the same time. So, the system has infinitely many solutions.

will satisfy both equations at the same time. So, the system has infinitely many solutions.

If the system is inconsistent and has no solution, the two lines are parallel in the plane.

Here is an example.

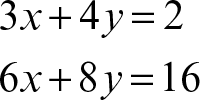

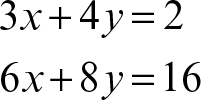

Graph the system  .

.

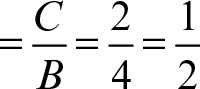

The equation 3x + 4y = 2 has slope  and y-intercept

and y-intercept  . The equation 6x + 8y = 16 has slope

. The equation 6x + 8y = 16 has slope  and y-intercept

and y-intercept  . The two lines representing the equations have the same slope, but different y-intercepts. Use Method 2 from the section “Graphing y = mx + b” earlier in this chapter to graph the two equations in the same coordinate plane.

. The two lines representing the equations have the same slope, but different y-intercepts. Use Method 2 from the section “Graphing y = mx + b” earlier in this chapter to graph the two equations in the same coordinate plane.

The two lines have exactly the same slant but different y-intercepts, so they are parallel and will never intersect. The system has no common solution. Therefore, the system is inconsistent and has no solution.

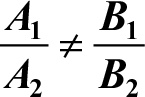

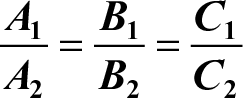

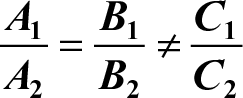

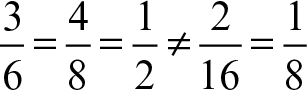

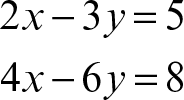

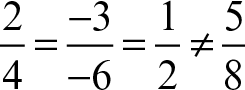

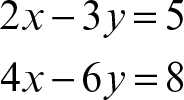

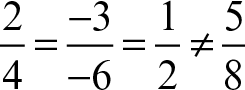

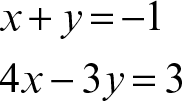

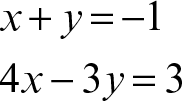

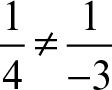

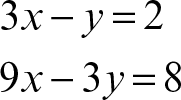

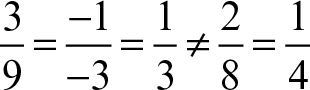

A quick way to decide whether a system of two linear equations has exactly one solution, infinitely many solutions, or no solution is to look at ratios of the coefficients of the two equations. Consider the system  .

.

If  , the system has exactly one solution.

, the system has exactly one solution.

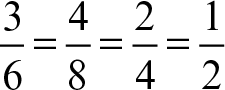

For example, in the system  ,

, ![]() . So, the system has exactly one solution. As previously shown in this section, the solution is (2, –1).

. So, the system has exactly one solution. As previously shown in this section, the solution is (2, –1).

If  , the system has infinitely many solutions.

, the system has infinitely many solutions.

For example, in the system  ,

,  . So, the system has infinitely many solutions. As previously shown in this section, 3x + 4y = 2 and 6x + 8y = 4 are equivalent equations with the samesolutions. All points on the line that has slope

. So, the system has infinitely many solutions. As previously shown in this section, 3x + 4y = 2 and 6x + 8y = 4 are equivalent equations with the samesolutions. All points on the line that has slope ![]() and y-intercept

and y-intercept ![]() will satisfy both equations at the same time.

will satisfy both equations at the same time.

If  , the system has no solution.

, the system has no solution.

For example, in the system  ,

,  . So, the system has no solution. As previously shown in this section, the two lines have exactly the same slant, but different y-intercepts. So they are parallel and will never intersect. The system is inconsistent and has no common solution.

. So, the system has no solution. As previously shown in this section, the two lines have exactly the same slant, but different y-intercepts. So they are parallel and will never intersect. The system is inconsistent and has no common solution.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank(s).

- The graph of Ax + By = C is a line with slope m = __________ and y-intercept = __________ (provided B ≠ 0).

- If a system of two equations is consistent with exactly one solution, the graphs of the two equations are two lines that __________ in exactly one point in the plane.

- If a system of two equations is consistent and has infinitely many solutions, the graphs of the two equations are two lines that have __________ points in common.

- If a system of two equations is inconsistent and has no solution, the graphs of the two equations are two lines that are __________ in the plane.

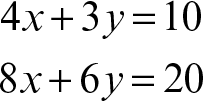

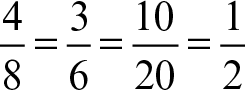

- Determine whether the given system has exactly one solution, infinitely many solutions, or no solution. Justify your answer.

Solutions

- intersect

- all

- parallel

- The system

has exactly one solution because

has exactly one solution because  .

. - The system

has no solution because

has no solution because  .

. - The system

has infinitely many solutions because

has infinitely many solutions because  .

.

- The system

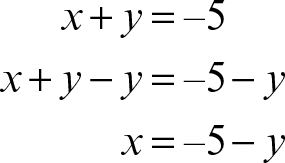

Solving a System of Two Linear Equations by Substitution

To solve a system of two linear equations by the method of substitution, do these steps.

Step 1. Select the simpler equation and solve for one of the variables in terms of the other. Tip: You can solve for either variable. Use your judgment to decide.

Step 2. Substitute this expression into the other equation, simplify, and solve for the variable.

Step 3. Substitute the answer to Step 2 into one of the original equations and solve for the other variable.

Step 4. State the solution and check it in the original equations.

Here is an example.

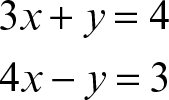

Solve the system  by the method of substitution.

by the method of substitution.

The system has exactly one solution because ![]() .

.

Step 1. Select the simpler equation and solve for one of the variables in terms of the other. Tip: Treat the other variable as a constant while you solve.

Solve x + y = –5 for x in terms of y.

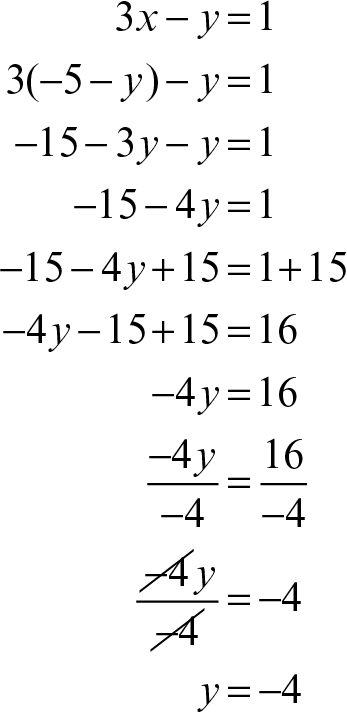

Step 2. Substitute this expression into the other equation, simplify, and solve for the variable.

Step 3. Substitute the answer to Step 2 into one of the original equations and solve for the other variable. Tip: You can substitute into either equation. Use your judgment to decide.

Step 4. State the solution and check it in the original equations.

The ordered pair (–1, –4) is the solution of the system  .

.

Check:

![]() Try These

Try These

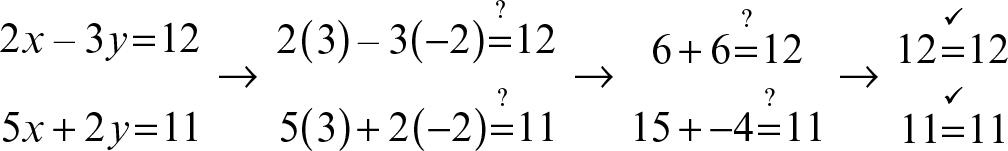

- Solve the system

by the method of substitution.

by the method of substitution. - Solve the system

by the method of substitution.

by the method of substitution. - Solve the system

by the method of substitution.

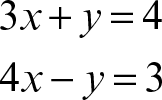

by the method of substitution.

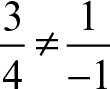

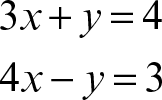

- The system

has exactly one solution because

has exactly one solution because  .

.

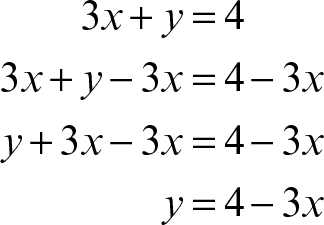

Step 1. Solve 3x + y = 4 for y in terms of x.

Isolate the y term by subtracting 3x from both sides of the equation. Then combine like terms.

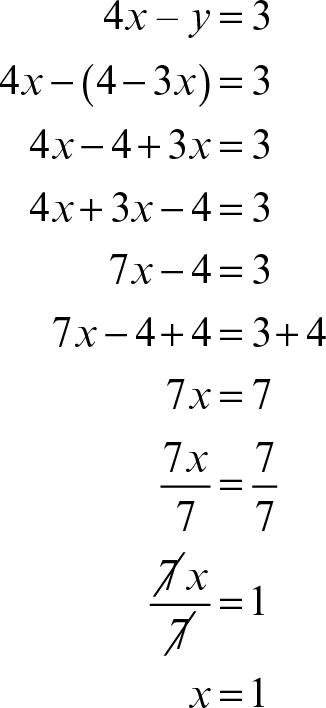

Step 2. Substitute y = 4 – 3x into the equation 4x – y = 3, simplify, and solve for x.

Step 3. Substitute x = 1 into the equation 3x + y = 4 and solve for y.

Step 4. The ordered pair (1, 1) is the solution of the system

.

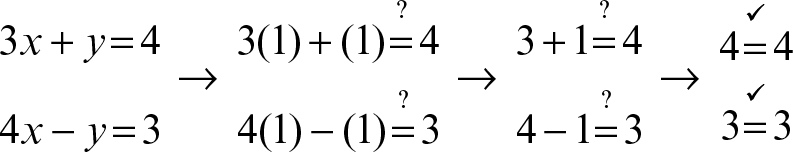

.Check:

- The system

has no solution because

has no solution because  .

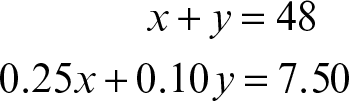

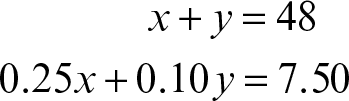

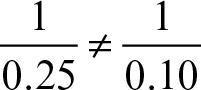

. - The system

has exactly one solution because

has exactly one solution because  .

.

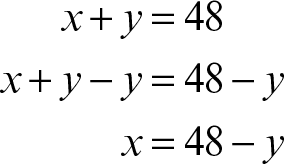

Step 1. Solve x + y = 48 for x in terms of y.

Isolate the x term by subtracting y from both sides of the equation. Then combine like terms.

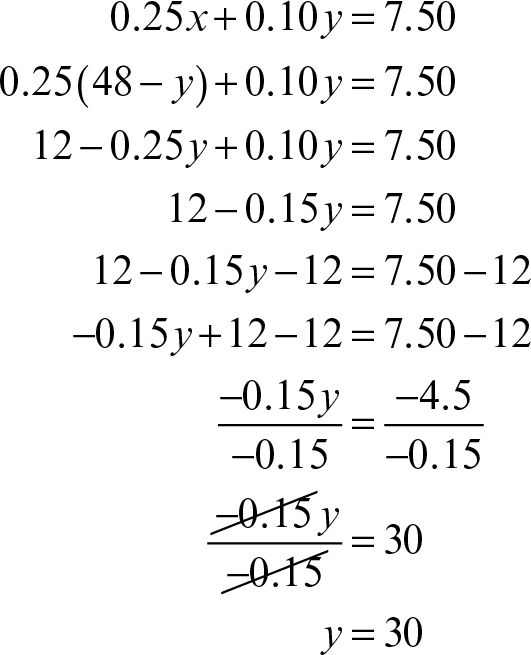

Step 2. Substitute x = 48 – y into the equation 0.25x + 0.10y = 7.50, simplify, and solve for y.

Step 3. Substitute y = 30 into the equation x + y = 48 and solve for x.

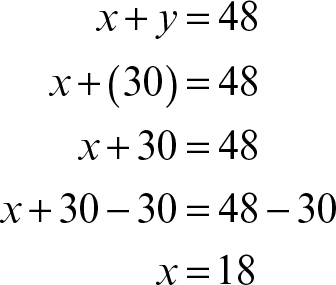

Step 4. The ordered pair (18, 30) is the solution of the system

.

.Check:

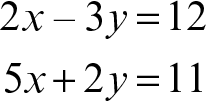

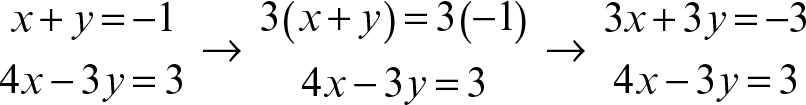

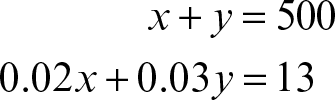

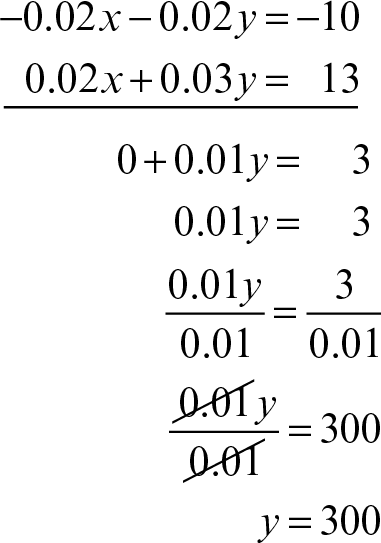

Solving a System of Two Linear Equations by Elimination

To solve a system of linear equations by the method of elimination, do these steps.

Step 1. Write both equations in standard form: Ax + By = C.

Step 2. Eliminate one of the variables. If necessary, multiply one or both of the equations by a nonzero constant or constants to make the coefficients of one of the variables sum to 0. Tip: You can eliminate either variable. Use your judgment to decide.

Step 3. Add the equations and solve for the variable that was not eliminated.

Step 4. Substitute the answer to Step 3 into one of the original equations and solve for the other variable.

Step 5. State the solution and check it in the original equations.

Here is an example.

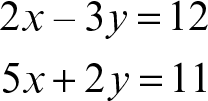

Solve the system  by the method of elimination.

by the method of elimination.

The system has exactly one solution because ![]() .

.

Step 1. Write both equations in standard form: Ax + By = C.

Step 2. To eliminate y, multiply the first equation by 2 and the second equation by 3.

Step 3. Add the transformed equations and solve for x.

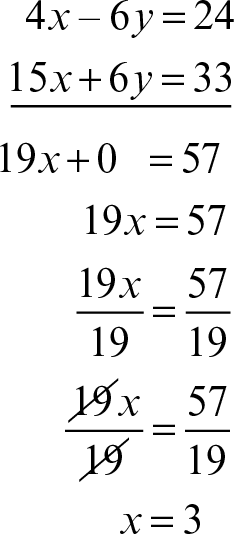

Step 4. Substitute x = 3 into the equation 2x – 3y = 12 and solve for y.

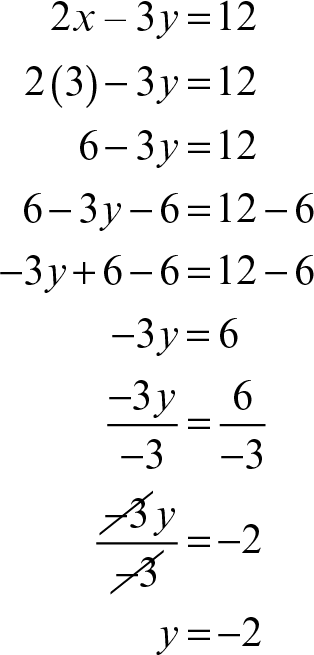

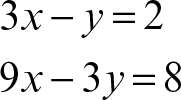

Step 5. State the solution and check it in the original equations.

The ordered pair (3, –2) is the solution of the system  .

.

Check:

![]() Try These

Try These

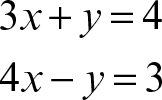

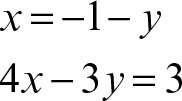

- Solve the system

by the method of elimination.

by the method of elimination. - Solve the system

by the method of elimination.

by the method of elimination. - Solve the system

by the method of elimination.

by the method of elimination.

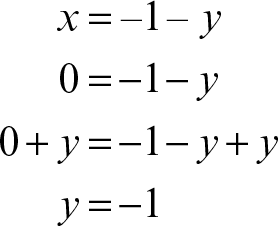

Solutions

- Step 1. Write both equations in standard form: Ax + By = C.

The system

has exactly one solution because

has exactly one solution because  .

.Step 2. To eliminate y, multiply the first equation by 3.

Step 3. Add the transformed equations and solve for x.

Step 4. Substitute x = 0 into the equation x = –1 – y and solve for y.

Step 5. State the solution and check it in the original equations.

The ordered pair (0, –1) is the solution of the system

.

.Check:

- The system

has no solution because

has no solution because  .

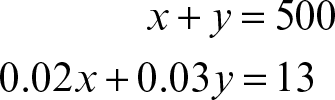

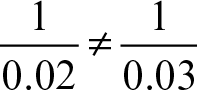

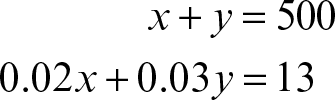

. - Step 1. Write both equations in standard form: Ax + By = C.

The system

has exactly one solution because

has exactly one solution because  .

.Step 2. To eliminate x, multiply the first equation by –0.02.

Step 3. Add the transformed equations and solve for y.

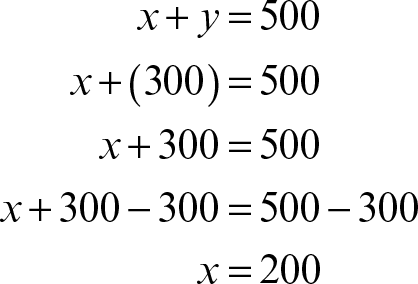

Step 4. Substitute y = 300 into the equation x + y = 500 and solve for x.

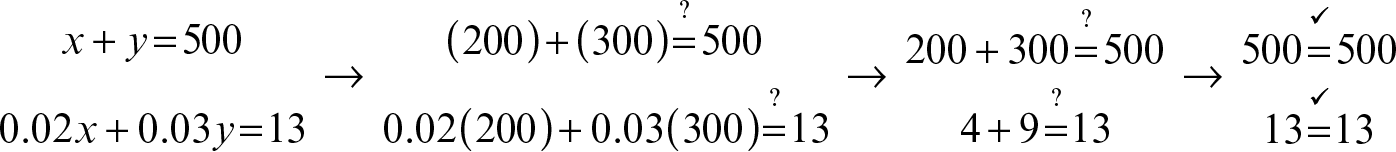

Step 5. State the solution and check it in the original equations.

The ordered pair (200, 300) is the solution of the system

.

.Check:

Solving Real-World Problems Leading to Two Linear Equations in Two Variables

You can use systems of two linear equations to model real-world problems in which there are two unknowns. Here is an example.

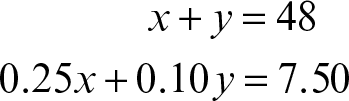

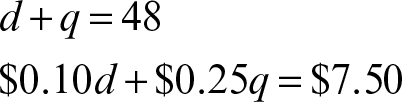

Rashid has $7.50 in dimes and quarters. The total number of coins is 48. How many dimes and how many quarters does Rashid have?

There are two unknowns. The number of dimes is unknown, and the number of quarters is unknown. Represent the two unknowns with variables.

Let d = the number of dimes and q = the number of quarters.

Make a chart to organize the information.

| Dimes | Quarters | Total | |

| Value per coin | $0.10 | $0.25 | |

| Number of coins | d | q | 48 |

| Value of coins | $0.10d | $0.25q | $7.50 |

Using the chart, write two equations that represent the facts of the question.

Tip: When you have two variables, you must write two equations in order to determine a solution.

Solve the system, omitting the units for convenience.

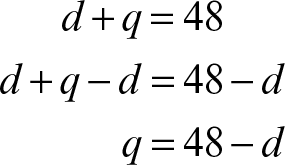

Using the method of substitution, solve d + q = 48 for q in terms of d.

Substitute q = 48 – d into the equation 0.10d + 0.25q = 7.50 and solve for d.

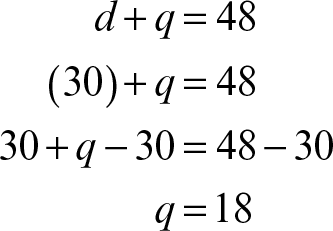

Substitute d = 30 into the equation d + q = 48 and solve for q.

Rashid has 30 dimes and 18 quarters.

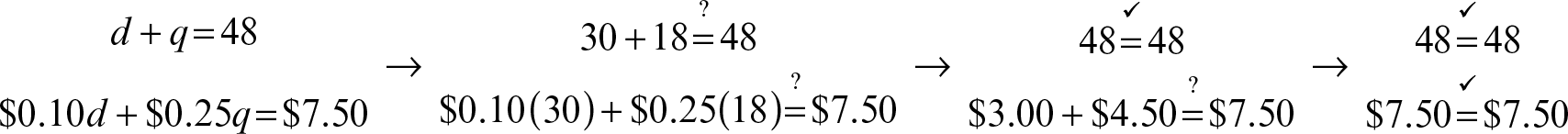

Check:

![]() Try These

Try These

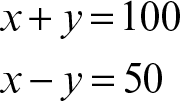

- The sum of two numbers is 100. Their difference is 50. Find the numbers.

- The length of a garden is 3 meters more than its width. The garden’s perimeter is 54 meters. Find the garden’s dimensions.

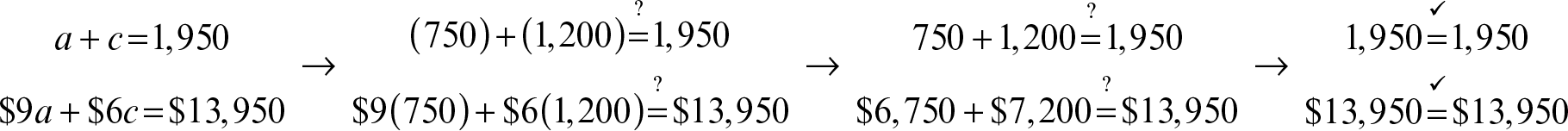

- The admission at a zoo is $9 for adults and $6 for children. On a certain day, 1,950 people enter the zoo and $13,950 is collected for their admission. How many adult tickets and how many children tickets were sold on that day?

Solutions

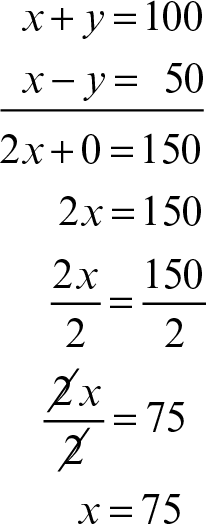

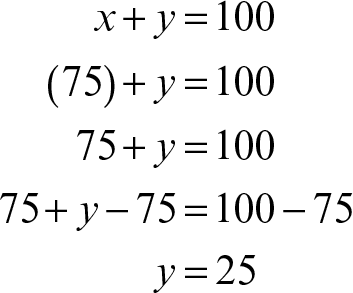

- There are two unknowns. The larger number is unknown, and the smaller number is unknown. Represent the two unknowns with variables.

Let x = the larger number and y = the smaller number.

Write two equations that represent the facts of the question.

Solve the system.

Using the method of elimination, add the two equations to eliminate y.

Substitute x = 75 into the equation x + y = 100 and solve for y.

The larger number is 75 and the smaller number is 25.

Check:

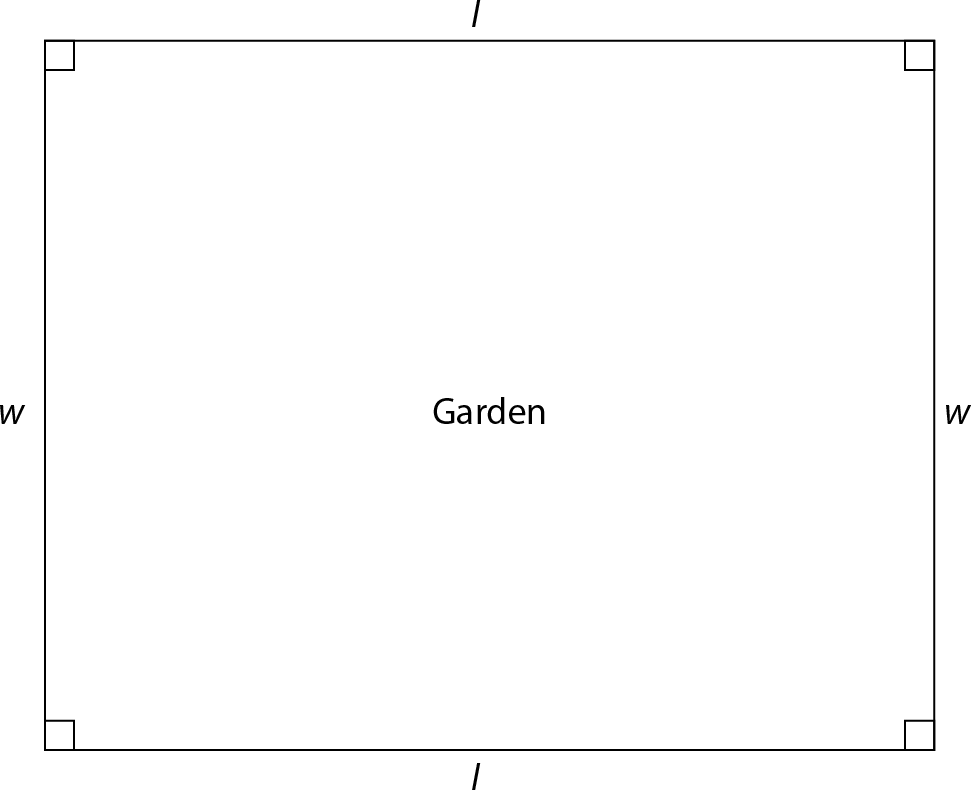

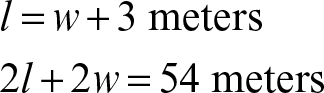

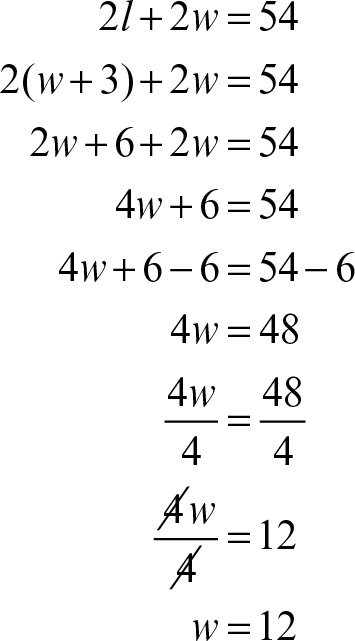

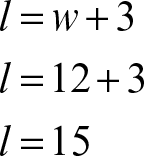

- There are two unknowns. The length of the garden is unknown, and its width is unknown. Represent the two unknowns with variables.

Let l = the garden’s length in meters and w = the garden’s width in meters.

Make a sketch.

Write two equations that represent the facts of the question.

Solve the system, omitting the units for convenience.

Using the method of substitution, substitute l = w + 3 into the equation 2l + 2w = 54 and solve for w.

Substitute w = 12 into the equation l = w + 3 and solve for l.

The garden’s length is 15 meters and its width is 12 meters.

Check:

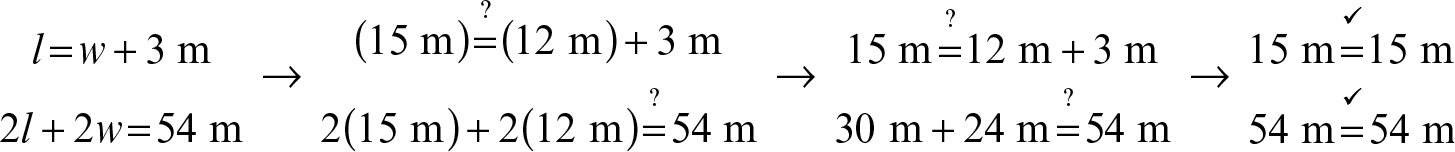

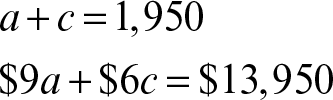

- There are two unknowns. The number of adult tickets is unknown, and the number of children tickets is unknown. Represent the two unknowns with variables.

Let a = the number of adult tickets and c = the number of children tickets.

Write two equations that represent the facts of the question.

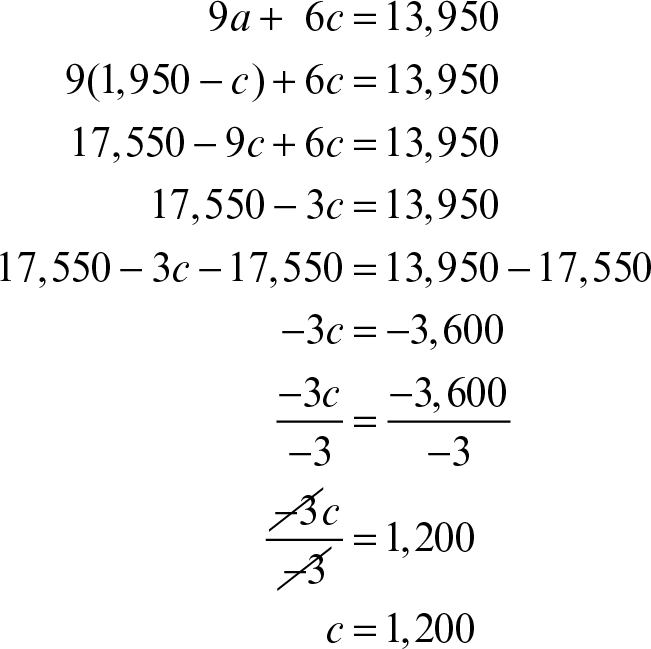

Solve the system, omitting the units for convenience.

Using the method of substitution, solve a + c = 1,950 for a in terms of c.

Substitute a = 1,950 – c into the equation 9a + 6c = 13,950 and solve for c.

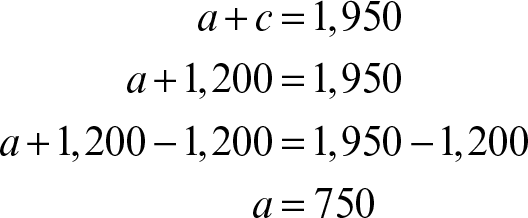

Substitute c = 1,200 into the equation a + c = 1,950 and solve for a.

The zoo sold 750 adult tickets and 1,200 children tickets.

Check: