lymphocytes, protein, immunoglobulin, and oligoclonal bands may be found in patients with no neurological symptoms or signs. The presence or absence of neurological disease is independent of CSF viral load.

lymphocytes, protein, immunoglobulin, and oligoclonal bands may be found in patients with no neurological symptoms or signs. The presence or absence of neurological disease is independent of CSF viral load.HIV enters the central nervous system (CNS) soon after 1° infection, either carried by infected mononuclear cells or by cell-free transfer across the blood–brain barrier. Infected monocytes then differentiate into macrophages, and produce virions that can infect astrocytes and microglia (brain macrophages). Neurons are not infected, but they are lost and become dysfunctional in HIV brain disease.

Neurological disease is common and may be the presenting clinical syndrome in 30% of HIV infections occurring at any stage, but most often presents following seroconversion or with severe immunodeficiency. Neurological features have been reported in 40–70% of patients with AIDS, 90% at post-mortem examination (Box 46.1). Abnormal CSF findings including  lymphocytes, protein, immunoglobulin, and oligoclonal bands may be found in patients with no neurological symptoms or signs. The presence or absence of neurological disease is independent of CSF viral load.

lymphocytes, protein, immunoglobulin, and oligoclonal bands may be found in patients with no neurological symptoms or signs. The presence or absence of neurological disease is independent of CSF viral load.

Mechanisms of CNS injury and the spectrum of neurological disease vary with the stage of HIV infection and the degree of immune deficiency.

• At seroconversion: viraemia and inflammation resulting from the initial immunological response to HIV infection predominate, inducing aseptic meningitis, meningoencephalitis, ataxic neuropathy, Guillain–Barré syndrome, acute myelopathy, multiple-sclerosis-like syndrome, acute brachial neuritis, Bell’s palsy, and acute meningoradiculitis. Patients presenting with these syndromes should be offered HIV screening.

• In chronic HIV infection: asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment can be found in 5–20% of patients (60% in those with AIDS diagnosis). This tends to improve with ART.

• As HIV progresses: altered CNS cytokine production and direct neurotoxic effects of HIV components (e.g. gp120) are pathogenic.

• With immunodeficiency: OIs/tumours and complications of treatment predominate.

ART has changed the epidemiology of the neurological manifestations of HIV resulting in  CNS OIs,

CNS OIs,  incidence of HIV dementia complex, and improved prognosis for some infections that were previously difficult to treat, such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). However, there has been

incidence of HIV dementia complex, and improved prognosis for some infections that were previously difficult to treat, such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). However, there has been  of drug-induced CNS and peripheral nerve disease.

of drug-induced CNS and peripheral nerve disease.

Box 46.1 HIV-related neurological and neuromuscular disease may present with a number of symptom complexes

May be an important symptom of neuropathology, such as 1° or opportunist meningitis, intracerebral opportunist pathologies, or the side-effects of drugs, such as zidovudine or co-trimoxazole. Non-HIV-related problems, such as migraine or psychogenic headache may occur.

May occur with or without motor abnormalities and is a significant symptom in peripheral neuropathy 2° to HIV, drugs or OI.

May result from muscular weakness due to myopathic processes, but intrinsic or extrinsic spinal cord disease should be considered and sensory levels searched for.

Risk. First seizure may be a first presentation of HIV, 5–9% lifetime risk. Most commonly 2o to OI in AIDS:

Risk. First seizure may be a first presentation of HIV, 5–9% lifetime risk. Most commonly 2o to OI in AIDS:

• OIs such as toxoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and PML.

Particularly with cerebral toxoplasmosis, 1° cerebral lymphoma, and PML.

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) vary from relatively asymptomatic deficits, through minor cognitive impairment to HIV-associated dementia (HAD). Prior to ART dementia was a common cause of morbidity and mortality, seen in up to 50% of patients before death. Generally seen with  CD4 count. Pathogenesis may include altered cytokine levels, free radicals, and the neurotoxic effects of gp120. Histological abnormalities include perivascular infiltrates, microglial nodules, multinuclear giant cells, and pruning of dendritic processes in the white matter (leading to significant gliosis) and subcortical gray matter with relative sparing of the cortex.

CD4 count. Pathogenesis may include altered cytokine levels, free radicals, and the neurotoxic effects of gp120. Histological abnormalities include perivascular infiltrates, microglial nodules, multinuclear giant cells, and pruning of dendritic processes in the white matter (leading to significant gliosis) and subcortical gray matter with relative sparing of the cortex.

HAND presents with variable severity of poor concentration, decreased executive functioning, impaired short-term memory, and slowed thought and reaction times. HAD is associated with clumsiness, gait disturbance may follow, with corticospinal tract abnormalities. Psychiatric illness and personality change may also be presenting features. Depression, effects of substance abuse, cerebrovascular disease, and neurosyphilis should be excluded.

Blood and CSF serological tests for syphilis should be carried out and vitamin B12 deficiency excluded. Other conditions, such as CNS infections (TB, toxoplasmosis, CMV encephalitis), PML, lymphoma, and toxic metabolic states (e.g. alcoholism, adverse medication effects, drug interaction, recreational drug use) should be excluded as dictated by the clinical presentation.

MRI (more sensitive) or CT brain scan reveal cerebral atrophy with abnormality of the periventricular white matter. Neuropsychological examination reveals  executive thought processes and

executive thought processes and  short-term memory. CSF should be examined to exclude other pathologies and OIs. Electro-encephalogram (EEG) may reveal non-specific sencephalopathic changes.

short-term memory. CSF should be examined to exclude other pathologies and OIs. Electro-encephalogram (EEG) may reveal non-specific sencephalopathic changes.

ART, consider including zidovudine (proven efficacy) or other drugs that cross the blood–brain barrier, can produce marked improvement in intellectual function and return to independent living. The patient may require psychological and social support, including help to take medication.

VZV is a rare cause of meningo-encephalitis, is seen when CD4 count <50 cells/µL. Due to direct CNS infection, rather than reactivation of dormant virus, as is the case with shingles. The pathological process is large- and small-vessel vaculopathy leading to ischaemic and demyelinating lesions. 33–50% of patients do not have the typical rash. CT or MRI may show necrotizing encephalitis and help differentiate from toxoplasmosis and PML, but changes are not specific. CSF should be examined by PCR (highly sensitive and specific). Treatment with aciclovir 10 mg/kg 8-hourly should be given for at least 14 days, followed by prophylaxis until CD4 >100 cells/mm3.

CMV encephalitis occurs when CD4 <50 cells/mm3 and may be suspected when there is evidence of CMV disease in other organs, or blood and CSF PCR is positive and patient presents with drowsiness, cognitive dysfunction, and seizures. CMV directly toxic to neurons. Treatment as for CMV retinitis.

HSV is an uncommon cause, but diagnosis should be considered in patients with meningo-encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, myelitis, or polyradiculitis. DNA detection in the CSF is very useful, with high sensitivity and specificity.

Unlike other OIs, the prevalence of PML has not significantly  with ART. It is a demyelinating disease caused by reactivation of John Cunningham virus (JCV), occurs in 4–8% of patients with advanced HIV infection. Fulminant disease with dementia and coma can occur, but the usual picture is of subacute or chronic progressive disease with focal deficits. These include personality change, aphasia, hemiparesis, dizziness, gait disturbance, visual field defects, and seizures.

with ART. It is a demyelinating disease caused by reactivation of John Cunningham virus (JCV), occurs in 4–8% of patients with advanced HIV infection. Fulminant disease with dementia and coma can occur, but the usual picture is of subacute or chronic progressive disease with focal deficits. These include personality change, aphasia, hemiparesis, dizziness, gait disturbance, visual field defects, and seizures.

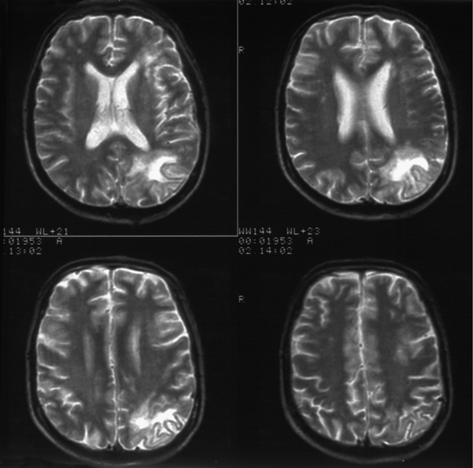

MRI scan usually reveals single or multiple lesions (non-enhancing, hyperintense on T2-weighting) without mass effect in the white matter, particularly in the parieto-occipital region (Plate 30). CSF JCV PCR is +ve in ~60% of cases and  JCV VL associated with poorer prognosis.

JCV VL associated with poorer prognosis.

Plate 30 MRI— progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (46).

Prognosis is poor, especially without ART. ART leads to significant improvement in 10%, but 33% die within 2 years. Some individuals, especially those with very low CD4 counts, can develop IRIS with worsening of PML or new-onset PML after the initiation of ART. Treatment trials with cidofovir, interferon alfa α, and topotecan were unsuccessful. Case reports of improvement with mefloquine and/or mirtazapine.

The most common cause of mass lesions in HIV prior to the introduction of PCP prophylaxis, which has  incidence. Results from reactivation of a previously acquired infection when CD4 declines (<200 cells/mm3). Often contracted from contaminated soil or direct contact with cats.

incidence. Results from reactivation of a previously acquired infection when CD4 declines (<200 cells/mm3). Often contracted from contaminated soil or direct contact with cats.

Typically includes confusion, headache, personality change, hemiparesis, focal sensory disturbances, seizures, and fever.

MRI or CT scanning reveal ring-enhancing lesions with oedema, usually multiple, particularly in the cortex at gray–white matter interface and thalamus. The differential diagnosis, particularly if lesions are single, includes primary cerebral lymphoma, cryptococcoma, and tuberculomas. CSF changes are non-specific. Positive serum toxoplasma IgG in 90%. CSF PCR is helpful if +ve (sensitivity 50%, specificity 100%).

Standard therapy for cerebral toxoplasmosis is sulfadiazine 1–2 g qds and pyrimethamine 200 mg loading dose followed by 50–100 mg/day with folinic acid to reduce bone marrow toxicity. Clindamycin 600 mg IV/PO qds if allergic to sulfonamide. Neuro-imaging should be repeated after 2 weeks followed by brain biopsy to exclude other pathologies if no improvement. 2° prophylaxis (pyrimethamine 50 mg od and sulfadiazine 2–3g/day in 2–4 divided doses or clindamycin 300 mg tds), should be given until immune reconstitution with ART (CD4 >200 cells/µL for >6 months). 1° prophylaxis as for PCP.

Cryptococcus neoformans (an encapsulated yeast, common in environment, found in bird droppings)—most common fungal pathogen in the CNS. Usually when CD4 <100 cells/mm3.

Usually as subacute meningitis (may initially be surprisingly mild) with headache and fever. Evidence of meningism occurs in only 30%. A high index of suspicion must be maintained to avoid delays in diagnosis. Other presentations include acute confusional state and cranial nerve palsies.

CSF pressures can be markedly raised, normally raised protein, low glucose and pleocytosis; but pleocytosis may be absent, and protein and glucose levels normal. The organism may be visualized by India ink staining. Mainstay of diagnosis is detection of CSF and serum cryptococcal antigen, which is highly sensitive. Neuro-imaging is usually normal, but cryptococcomas can occur, usually in the basal ganglia.

Daily lumbar punctures (LPs) may be required until CSF pressures normalize. If CSF pressure does not  with LPs, a lumbar drain may be used. Antifungal therapy with IV liposomal amphotericin B 4mg/kg/day IV in combination with flucytosine 100mg/kg/day for 2 weeks followed by fluconazole 400 mg daily. Renal function should be monitored. Ongoing suppressive therapy with fluconazole (superior to itraconazole) is required to minimize significant relapse rates. Continue until immune reconstitution is achieved with ART.

with LPs, a lumbar drain may be used. Antifungal therapy with IV liposomal amphotericin B 4mg/kg/day IV in combination with flucytosine 100mg/kg/day for 2 weeks followed by fluconazole 400 mg daily. Renal function should be monitored. Ongoing suppressive therapy with fluconazole (superior to itraconazole) is required to minimize significant relapse rates. Continue until immune reconstitution is achieved with ART.

Commence ART 2 weeks after initiation of antifungals.

Most commonly presents at seroconversion, but may be recurrent or become chronic. Usually presents with headache. Cranial nerve palsies and altered mental state can occur. Lumbar puncture, following neuro-imaging, when focal deficits are present, needed to exclude other pathologies. Mildly  CSF lymphocyte counts and protein level with normal glucose are typical findings.

CSF lymphocyte counts and protein level with normal glucose are typical findings.

Evidence of autonomic dysfunction can be found at various stages of HIV infection. Measurement of pulse rate variation in response to standing, deep breathing, Valsalva manoeuvre, and cold exposure reveal autonomic dysfunction in ~15% (probably underdiagnosed). Frequency related to the level of immune function, but unlike sensory neuropathy, not the use of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

Symptomatic autonomic neuropathy occurs in advanced immunodeficiency, and may result in severe postural hypotension and syncope. Cardiac denervation may lead to serious cardiac dysrhythmias.

Those developing postural dizziness or syncope should have postural blood pressure recordings, tests of autonomic function, and assessment of sodium intake. Adrenal insufficiency should be excluded by carrying out a short Synacthen® test.

Therapy with mineralocorticoid (fludrocortisone 50–200 mcg daily), sodium supplements, compression stockings, and α-adrenergic agents, such as midodrine, may reduce postural blood pressure falls and alleviate symptoms. There may be improvement in autonomic function with ART.

Post-mortem studies have shown vacuolar myelopathy in up to 30% of cases, but clinically far less common. Pathological mechanisms are probably the same as in HIV dementia complex. Often associated with dementia, but may be isolated when the clinical picture mimics that of vitamin B12 deficiency spinal cord disease.

Typically, with subacute progressive motor and sensory deficits with paraesthesiae, but brisk tendon reflexes—commonly lower limb. Uncharacteristic findings may occur if there is concomitant peripheral neuropathy or other cause.

Investigations should include measurement of vitamin B12 level and radiological imaging to exclude structural lesions. Areas of  T2 signal may occasionally be seen on MRI scan. CSF may be normal or show only non-specific abnormalities, such as low-level pleocytosis or mildly

T2 signal may occasionally be seen on MRI scan. CSF may be normal or show only non-specific abnormalities, such as low-level pleocytosis or mildly  protein levels.

protein levels.

Spasticity may require anti-spasmodic therapy, such as baclofen 10–30 mg tid, and dysesthesia may require amitriptyline or gabapentin. Physiotherapy and occupational therapy input. Improvements in function may occur with ART.

In patients from areas of significant risk for HTLV1 infection, such as Japan, the Caribbean, and parts of Central and Latin America, subacute myelopathy may result from HTLV1 infection and anti-HTLV1 antibodies should be assayed. HTLV1 viral load can be performed from serum or CSF.

Acute spinal cord disease may occasionally occur as a seroconversion event. Other important causes are spinal cord compression from lymphomatous metastases, tuberculous or bacterial abscesses, and acute infections with VZV.

Typically, rapidly developing neurological deficit, such as leg weakness and sphincter disturbance, with evidence of a sensory level.

Emergency investigation required with spinal MRI or CT. In the absence of compression CSF and/or biopsy of compressive lesion, patient should be examined for evidence of infectious and neoplastic causes, including HIV, VZV, and CMV viral PCR and cytology.

Supportive with specific treatment directed at the identified cause.

May occur at any stage of HIV infection with a typical distribution and course. Atypical multi-dermatomal involvement, viraemic dissemination of lesions, and recurrences more common as CD4 counts  .

.

Frequently prodromal pain of dermatomal distribution followed by an erythematous maculopapular eruption, evolving into vesicles, which then pustulate and crust. Bullous haemorrhagic and necrotic lesions may occur. Lesions will be at various stages at any one time. With low CD4 dissemination of lesions possible. Pain during the acute phase can be severe and disabling; post-herpetic neuralgia may follow.

Clinical picture is usually characteristic. VZV can be detected by viral swab of burst vesicle by PCR.

Pain often does not respond well to conventional analgesics and adjuvants. Amitriptyline 25–150 mg/day or gabapentin up to 2.4 g/day in divided doses may be required. In disseminated or eyesight-threatening ophthalmic shingles, consider IV aciclovir 10 mg/kg 8-hourly as early as possible (most effective within 24 hours, but useful even if given later in immunocompromised) and switch to valaciclovir 1 g tid when lesions cease to progress for a total course of at least 7 days or until all lesions have dried and crusted. Oral valaciclovir may be used in dermatomal shingles, most effective if started within 72 hours, in immunosuppressed often required to prevent deterioration/dissemination.

Ophthalmology review if ophthalmic branch of trigeminal nerve affected (forehead and to tip of nose), aciclovir eye drops may be used if cornea involved.

Usually occurs in patients with advanced HIV disease. Typical presentation is with subacute onset of multifocal or asymmetric sensory deficits, including Bell’s palsy. Nerve conduction studies show demyelination and axonal loss. May be associated with CMV infection in advanced immunodeficiency. Differential diagnosis includes nerve compression in severe wasting syndrome, neoplastic infiltration, and neurotropic viral infections (e.g. VZV). Consider treatment with ganciclovir if circumstantial evidence of CMV infection (e.g. positive blood PCR).

The toxicity of therapeutic drugs, notably didanosine, zalcitabine, and stavudine (20% effected after 6 months), is responsible for  proportion of peripheral neuropathy.

proportion of peripheral neuropathy.

Occurs in 35% of patients with advanced HIV disease. 15% of those with asymptomatic HIV infection have abnormal nerve conduction studies. Typical symptoms are tingling, numbness, and burning pain, beginning in the toes or plantar surfaces, often ascending over time. Involvement of hands is rare. Examination shows  ankle reflex, vibration sense, appreciation of temperature, and fine touch. Unexpectedly brisk reflexes should raise the question of additional spinal cord or brain disease. Differential diagnosis includes effects of alcohol, drug toxicity, and vitamin deficiency. Treatment is directed towards controlling neuropathic pain with drugs, such as amitriptyline 25–150 mg daily or gabapentin (300 mg 8-hourly, maximum of 2.4 g daily) or pregabalin (75 mg bd to max of 300 mg daily).

ankle reflex, vibration sense, appreciation of temperature, and fine touch. Unexpectedly brisk reflexes should raise the question of additional spinal cord or brain disease. Differential diagnosis includes effects of alcohol, drug toxicity, and vitamin deficiency. Treatment is directed towards controlling neuropathic pain with drugs, such as amitriptyline 25–150 mg daily or gabapentin (300 mg 8-hourly, maximum of 2.4 g daily) or pregabalin (75 mg bd to max of 300 mg daily).

May occur with seroconversion or during late stages of HIV infection. Manifestations as in non-HIV status with progressive symmetric weakness in the limbs and loss of tendon jerks, but CSF pleocytosis may occur. Treatment is immunoglobulin 400 mg/kg/day for 5 days or plasmapheresis up to six exchanges over 2 weeks. Patients with the chronic form may need monthly cycles of treatment until stabilization.

Caused by CMV infection in patients with CD4 counts <50 cells/mm3. Rarely caused by tuberculosis. There may be evidence of CMV disease elsewhere. Bilateral leg weakness progresses over several weeks, sometimes to flaccid paraplegia. Sphincter disturbance is common and sensory loss combined with painful dysaesthesia is usual. Sensory symptoms differentiate this from myopathy, and sphincter disturbance with sparing of the upper limbs distinguishes it from other forms of neuropathy. Cord compression (2° to lymphoma, toxoplasma, TB, etc.) should be excluded by MRI of spine, MRI is non-specific, but may show thickening of nerve roots or enhancement of cauda equina. CSF usually pleocytosis—40–50% neutrophils,  protein, and normal glucose. CSF PCR for CMV is +ve and the patient should be treated with ganciclovir or foscarnet.

protein, and normal glucose. CSF PCR for CMV is +ve and the patient should be treated with ganciclovir or foscarnet.

Strokes and transient ischaemic attacks are reported in 0.5–8% of HIV-infected patients. Prevention should include attention to vascular risk factors, such as smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia. Cocaine use and alcoholic binges may lead to thrombotic strokes. Embolic strokes may result from cardiac or carotid artery disease. Cardiogenic emboli may result from infective or non-infective endocarditis, following myocardial infarction or from dysrhythmias.

Cerebral vasculitis, particularly due to VZV or syphilis, may cause cerebral thrombosis. The hyper-coagulable state that may occur with HIV may contribute.

Haemorrhage may complicate VZV cerebral vasculitis and thrombocytopenia, rarely due to metastatic KS.

Can affect most parts of the nervous system (see Chapter 7, ‘Neurosyphilis’, p. 122).

KS, although the most common systemic neoplasm in HIV infection, rarely involves the nervous system.

The CNS may be invaded by non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, leading to malignant meningitis and compressive symptoms requiring intrathecal cytotoxic therapy and radiotherapy.

1° cerebral lymphoma occurs in patients with advanced immunodeficiency and presents with confusion, lethargy, personality change, focal neurological deficits, seizures, ataxia, and aphasia. On MRI or CT scanning, lesions are ring-enhancing, and about 50% are associated with cerebral oedema and mass effect. The finding of a single lesion favours the diagnosis of lymphoma over cerebral toxoplasmosis. +ve EBV PCR is suggestive, but not diagnostic of 1° cerebral lymphoma. Treatment for toxoplasma empirically may be considered with brain biopsy if no clinical response after 2 weeks. Cerebral radiotherapy may improve survival. Prognosis very poor with 3 months median survival.