2 Overview of Neurovascular Structures

2.1 Branches of the Abdominal Aorta: Overview and Paired Branches

A Overview of the abdominal aorta and pelvic arteries (abdominal organs removed)

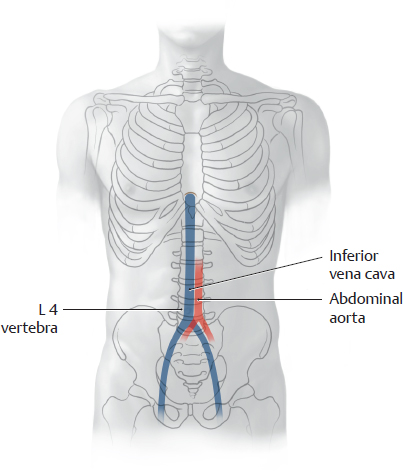

Anterior view (female pelvis). The esophagus has been pulled slightly inferiorly, and the peritoneum has been completely removed. The abdominal aorta is the distal continuation of the thoracic aorta. It descends slightly to the left of the midline to approximately the level of the L 4 vertebra, as shown in B (or possibly to the L 5 vertebra in older individuals). There it divides into the paired common iliac arteries (aortic bifurcation). The common iliac arteries divide further into the internal and external iliac arteries. The abdominal aorta (see C) and its major branches give origin to various “subbranches” that supply the abdomen and pelvis (see D).

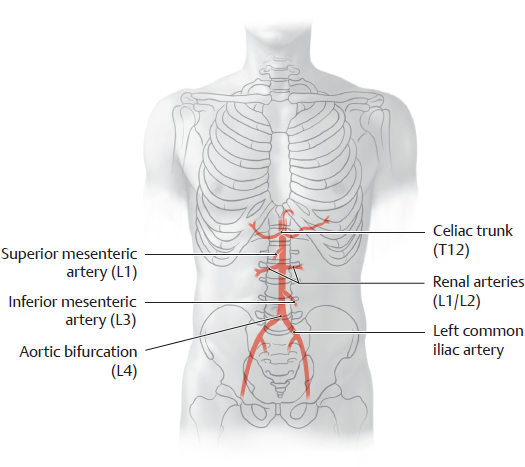

B Projection of the abdominal aorta and its major branches onto the vertebral column and pelvis

Anterior view of the five major arterial trunks. The major branches of the abdominal aorta can be identified in imaging studies based on their relationship to the vertebrae.

C Sequence of branches from the abdominal aorta

D Functional groups of arteries that supply the abdomen and pelvis

The branches of the abdominal aorta and pelvic arteries can be divided into five broad functional groups (→ = give rise to). For details about the areas supplied by the unpaired branches see p. 213.

Paired branches (and one unpaired branch) that supply the diaphragm, kidneys, suprarenal glands, posterior abdominal wall, spinal cord, and gonads (see C) |

• Right and left inferior phrenic arteries

→ Right and left superior suprarenal arteries

• Right and left middle suprarenal arteries

• Right and left renal arteries

→ Right and left inferior suprarenal arteries

• Right and left testicular (ovarian) arteries

• Right and left lumbar arteries (first through fourth)

• Median sacral artery (with lowest lumbar arteries) |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen, stomach, and duodenum (see C, pp. 213 and 265) |

• Celiac trunk with

– Left gastric artery

– Splenic artery

– Common hepatic artery |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the small intestine and large intestine as far as the left colic flexure (see C, pp. 213 and 269) |

• Superior mesenteric artery |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the large intestine from the left colic flexure (see C, p. 213) |

• Inferior mesenteric artery |

One indirect (see below) paired trunk that supplies the pelvis (see A, p. 213) |

• Internal iliac artery (from the common iliac artery, not directly from the aorta, hence an “indirect paired trunk”) |

2.2 Branches of the Abdominal Aorta: Unpaired and Indirect Paired Branches

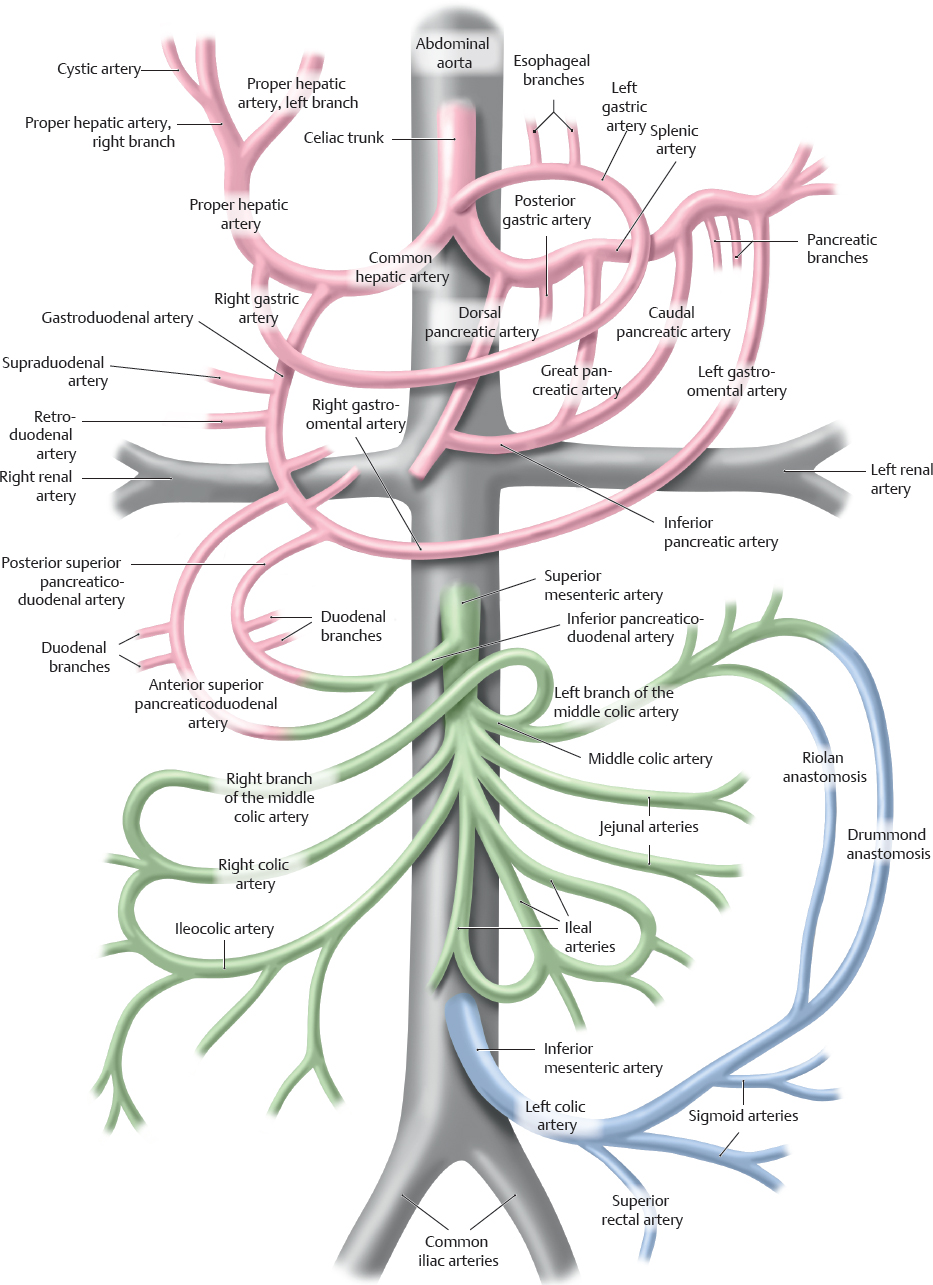

A Classification of arteries supplying the abdomen and pelvis

Red: Branches of the celiac trunk. These supply the proximal bowel segments from the abdominal esophagus to the pancreas and duodenum.

Green: Branches of the superior mesenteric artery. These supply the middle bowel segments from the pancreas and duodenum to the left colic flexure.

Blue: Branches of the inferior mesenteric artery. These supply the distal bowel segments from the left colic flexure to the rectum.

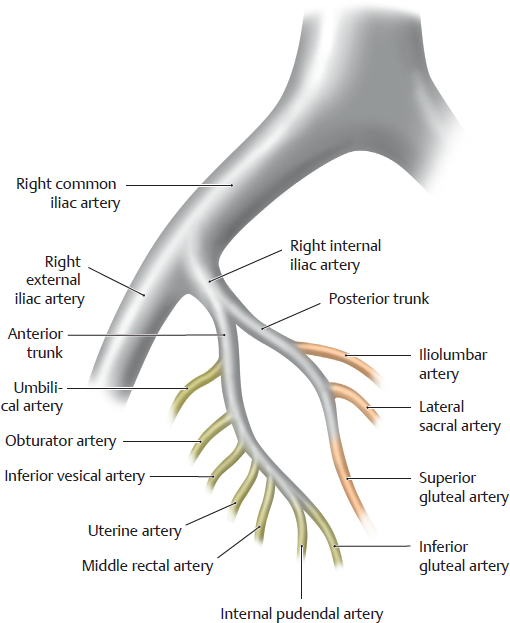

B Right common iliac artery with subbranches

The aortic bifurcation is the point where the abdominal aorta bifurcates into the two common iliac arteries, which give off multiple subbranches that supply the viscera and pelvic walls (see D).

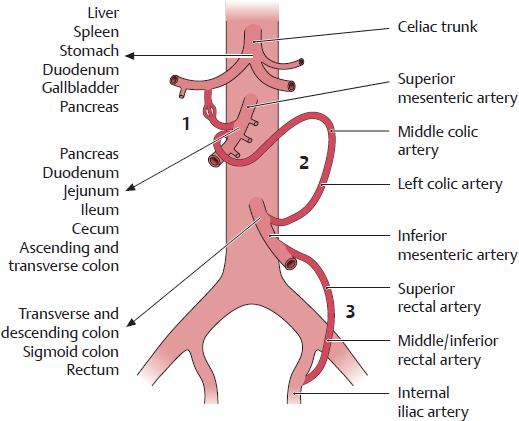

C Abdominal arterial anastomoses

1 Between the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery via the pancreaticoduodenal arteries

2 Between the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries (middle and left colic arteries; Riolan and Drummond anastomoses, see A)

3 Between the inferior mesenteric artery and internal iliac artery (superior rectal artery and middle or inferior rectal artery)

These anastomoses are important in that they can function as collaterals, delivering blood to intestinal areas that have been deprived of their normal blood supply.

D Classification of the arteries supplying the abdomen and pelvis

For the area supplied by the paired branches see p. 211 (→ = is continuous with).

Note the anastomoses particularly between the unpaired trunks (see Fig. A and C).

One unpaired trunk that supplies the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen, stomach, and duodenum (see A) |

• Celiac trunk with

– Splenic artery |

→ Left gastro-omental artery

→ Posterior gastric artery (and short gastric arteries)

→ Pancreatic branches

→ Caudal pancreatic artery

→ Great pancreatic artery

→ Dorsal pancreatic artery

→ Inferior pancreatic artery

→ Transverse pancreatic artery |

– Left gastric artery |

→ Esophageal branches |

– Common hepatic artery |

→ Gastroduodenal artery

→ Supraduodenal artery (inconstant branch of the gastroduodenal artery)

→ Retroduodenal artery

→ Right gastro-omental artery

→ Anterior or posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery

→ Duodenal branches

→ Right gastric artery

→ Proper hepatic artery

→ Cystic artery |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the small intestine and large intestine as far as the left colic flexure (see A) |

• Superior mesenteric |

→ Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery artery

→ Jejunal and Ileal arteries

→ Ileocolic artery

→ Right colic artery

→ Middle colic artery |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the large intestine from the left colic flexure (see A) |

• Inferior mesenteric artery |

→ Left colic artery

→ Sigmoid arteries

→ Superior rectal artery |

One indirect (see below) paired trunk that supplies the pelvis (see B) |

• Internal iliac artery (from the common iliac artery, not directly from the aorta, hence an “indirect paired trunk”) with branches that supply |

|

→ Umbilical artery

→ Superior vesical artery

→ Artery of ductus deferens ♂

→ Inferior vesical artery

→ Uterine artery

→ Middle rectal artery

→ Internal pudendal artery |

The pelvic walls (parietal branches) |

|

→ Iliolumbar artery

→ Lateral sacral artery

→ Obturator artery

→ Superior and inferior gluteal arteries |

2.3 Inferior Vena Caval System

A Tributaries of the inferior vena cava in the posterior abdomen and pelvis

Anterior view of an opened female abdomen. All organs but the left kidney and suprarenal gland have been removed, and the esophagus has been pulled slightly inferiorly.

The inferior vena cava receives numerous tributaries that return venous blood from the abdomen and pelvis (and, of course, from the lower limbs), analogous to the distribution of the paired abdominal aortic branches in this region. The inferior vena cava is formed by the union of the two common iliac veins at the approximate level of the L 5 vertebra (see C), behind and slightly inferior to the aortic bifurcation.

Note the special location of the left renal vein and its risk of compression by the superior mesenteric artery (see p. 269): The left renal vein passes in front of the abdominal aorta but behind the superior mesenteric artery. Veins in the male pelvis are described on p. 347. The veins in the pelvis have numerous variants. For example, the tributaries of the internal iliac vein are frequently multiple (unlike those shown above) but unite to form a single trunk before entering the iliac vein (see also p. 349).

B Tributaries of the inferior vena cava

The difference in the venous drainage of the right and left kidneys is displayed more clearly here than in A. The continuity of the right ascending lumbar vein with the azygos vein is also shown.

Direct tributaries return venous blood directly to the inferior vena cava without passing through an intervening capillary bed. Direct tributaries drain the following organs:

• The diaphragm, abdominal wall, kidneys, suprarenal glands, testes/ovaries, and liver

• For the pelvis (via the common iliac vein) from the pelvic wall and floor, uterus, uterine tubes, bladder, ureters, accessory sex glands, lower rectum, and lower limb.

Indirect tributaries return blood that has passed through the capillary bed of the liver via the hepatic portal system (see p. 217). The following organs have indirect tributaries:

• The spleen

• The organs of the digestive tract: pancreas, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon, and upper rectum

Note: Venous blood from the inferior vena cava may drain through the ascending lumbar veins into the azygos or hemiazygos vein and thence to the superior vena cava. Thus a connection between the two venae cavae exists on the posterior wall of the abdomen and thorax: a cavocaval or intercaval anastomosis. The location and significance of cavocaval anastomoses are discussed on p. 218. Frequently an anastomosis exists between the suprarenal vein and inferior phrenic vein (not shown here, see A) on the left side of the body.

C Projection of the inferior vena cava onto the vertebral column

The inferior vena cava ascends on the right side of the abdominal aorta and pierces the diaphragm at the caval opening located at the T 8 level. The common iliac veins unite at the L 5 level to form the inferior vena cava (see also A).

D Direct tributaries of the inferior vena cava

• Right and left inferior phrenic veins

• Hepatic veins

• Right suprarenal vein

• Right and left renal veins at the L 1/L 2 level (the left testicular/ovarian vein and left suprarenal vein terminate in the left renal vein)

• Lumbar veins

• Right testicular/ovarian vein

• Common iliac veins (L 5 level)

• Median sacral vein (often terminates in the left common iliac vein)

2.4 Portal Venous System (Hepatic Portal Vein)

A The portal venous system in the abdomen

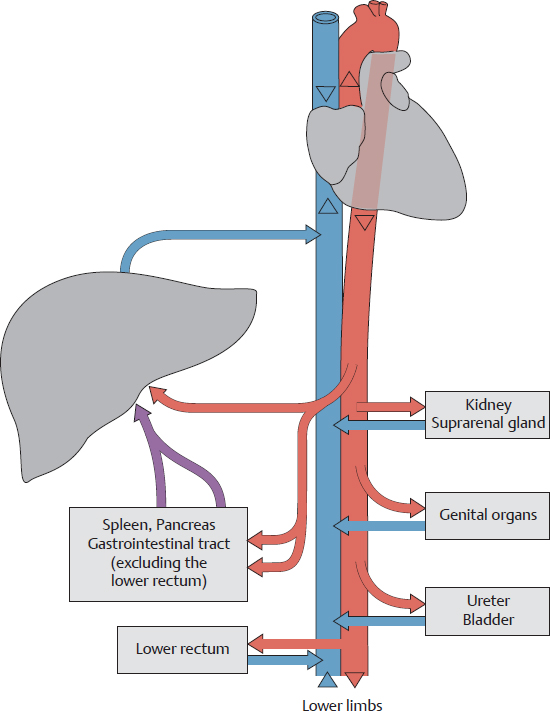

The arterial blood supply and venous drainage of the abdominal and pelvic organs differ in their functional organization: While they derive their arterial blood supply entirely from the abdominal aorta or one of its major branches, venous drainage is accomplished by one of two different venous systems:

1. Organ veins that drain directly or indirectly (via the iliac veins) into the inferior vena cava, which then returns the blood to the right heart (see also p. 214);

2. Organ veins that first drain directly or indirectly (via the mesenteric veins or splenic vein) into the portal vein—and thus to the liver—before the blood enters the inferior vena cava and returns to the right heart.

The first pathway serves the urinary organs, suprarenal glands, genital organs, and the walls of the abdomen and pelvis. The second pathway serves the organs of the digestive system (hollow organs of the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, gallbladder) and the spleen (see D). Only the lower portions of the rectum are exempt from this pathway and drain directly through the iliac veins to the inferior vena cava. This (re)routing of venous blood through the hepatic portal system ensures that the organs of the digestive tract deliver their nutrient-rich blood to the liver for metabolic processing before it is returned to the heart. It also provides a route by which elements of degenerated red blood cells can be conveyed from the spleen to the liver. Thus, the portal vein functions to deliver blood to the liver to support metabolism. This contrasts with the proper hepatic artery, which supplies the liver with oxygen and other nutrients. Anastomoses may develop between the portal venous system and vena caval system (portacaval anastomosis) and function as collateral pathways in certain diseases (see p. 218).

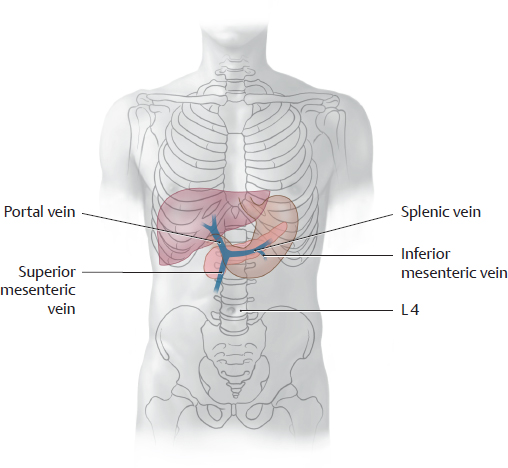

B Projection of the portal vein and its two major tributaries onto the vertebral column

The portal vein of the liver is formed by the union of the superior mesenteric vein and splenic vein to the right of the midline at the L 1 level. The inferior mesenteric vein typically opens into the splenic vein, also conveying its blood to the portal vein via this route.

Note the relationship of the portal vein to the liver, stomach, and pancreas.

C Tributaries of the portal vein

• Superior mesenteric vein (see p. 276) with its tributaries:

– Pancreaticoduodenal veins

– Pancreatic veins

– Right gastro-omental vein

– Jejunal veins

– Ileal veins

– Ileocolic vein

– Right colic vein

– Middle colic vein

• Inferior mesenteric vein (see p. 277) with its tributaries:

– Left colic vein

– Sigmoid veins

– Superior rectal vein

• Splenic vein (see p. 275) with its tributaries:

– Left gastro-omental vein

– Pancreatic veins

– Short gastric veins

• Direct tributaries (see p. 275)

– Cystic vein

– Left gastric vein with esophageal veins

– Right gastric vein

– Posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein

– Prepyloric vein

– Paraumbilical veins

D Distribution of the portal vein (see also C)

The portal vein of the liver is a short vessel (total length 6–12 cm) with a large caliber. On entering the liver, it divides into two main branches, one for each of the hepatic lobes. The region drained by the portal vein corresponds to the region supplied by the celiac trunk and the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. The portal vein receives venous blood from the hollow organs of the gastrointestinal tract (excluding the lower rectum) and from the pancreas, gallbladder, and spleen. Some of this blood flows directly to the portal vein through the corresponding organ veins, and the rest reaches the portal vein indirectly by way of the mesenteric veins or splenic vein.

2.5 Venous Anastomoses in the Abdomen and Pelvis

A Cavocaval (intercaval) anastomoses

Large venous anastomoses are present between the inferior and superior vena cava on the anterior and posterior trunk walls. Known as cavocaval or intercaval anastomoses, they provide collateral pathways for returning venous blood to the superior vena cava and right heart in patients with outflow obstructions affecting the inferior vena cava in the abdomen or the common iliac veins in the pelvis. Veins of the chest wall form the cranial portion of this collateral network. The veins of the anterior abdominal wall provide both a superficial pathway (anterior to the rectus abdominis) and a deep pathway (posterior to the rectus abdominis). (In the chest, these pathways lie outside or inside the thoracic skeleton.)

Note: On the anterior trunk wall, the paraumbilical veins (see B) establish a collateral pathway between the portal vein and drainage to the venae cavae. This portosystemic (portacaval) pathway is important in patients with obstructed portal venous flow and may affect the superficial and deep anterior pathways.

• Anastomoses on the posterior wall of the abdomen. They utilize the connection between the ascending lumbar vein and the azygos/hemiazygos vein. Two pathways are available:

1. A direct pathway between the ascending lumbar vein and azygos/hemiazygos vein:

Inferior vena cava → (possibly via the common iliac vein) ascending lumbar vein → azygos/hemiazygos vein → superior vena cava.

2. An indirect pathway between the ascending lumbar vein and azygos/hemiazygos vein by way of horizontal trunk wall veins (intercostal and lumbar veins, mediated by venous plexuses on the spinal column; for clarity, not shown here):

Inferior vena cava → (possibly via the common iliac vein) ascending lumbar vein → lumbar veins → vertebral venous plexus → posterior intercostal veins → azygos/hemiazygos vein → superior vena cava.

• Anastomoses on the anterior wall of the abdomen. They utilize superficial and deep cutaneous veins, which may exchange blood between them. Two pathways are available:

1. Deep pathway (posterior to the rectus abdominis):

Inferior vena cava → common iliac vein → external iliac vein → inferior epigastric vein → superior epigastric vein → internal thoracic vein → subclavian vein → brachiocephalic vein → superior vena cava.

2. Superficial pathway (anterior to the rectus abdominis):

Inferior vena cava → common iliac vein → external iliac vein → femoral vein → superficial epigastric vein/superficial circumflex iliac vein → thoracoepigastric vein/lateral thoracic vein → axillary vein → subclavian vein → brachiocephalic vein → superior vena cava.

B Schematic of collateral pathways for the portal vein (portosystemic collaterals)

Venous collateral pathways are also available between the portal venous system and the inferior and superior venae cavae. These portosystemic collaterals are physiological pathways that can develop in response to (1) overlapping venous territories in organs (venous plexuses in the esophagus, colon, rectum) or (2) the persistence of patent blood vessels that are normally obliterated after birth (umbilical vein, paraumbilical veins). These collateral pathways become clinically significant when the portal system is compromised (as in hepatic cirrhosis, for example). As venous pressure increases, the portal vein can divert blood away from the liver and return it to the supplying vessels. Thus, veins that are normally afferent vessels for the liver undergo a flow reversal (see red arrows) and transport blood back through the inferior or superior vena cava and back to the heart. Portosystemic shunts can be lifesaving, but nevertheless cause significant additional problems, because some of the vessels in the shunt pathways (in the esophagus and rectum, specifically) are barely capable of handling the significant redirected blood flow, with consequent rise of pressure in the system, and are thus liable to rupture. The following four collateral pathways are of key importance:

① Through veins of the stomach and distal esophagus (dilation of these veins may lead to esophageal varices, with risk of life-threatening hemorrhage):

Portal vein ← gastric veins ← esophageal veins → azygos/hemiazygos vein → superior vena cava.

② Through veins of the anterior abdominal wall:

Portal vein ← umbilical vein (patent part) ← paraumbilical veins → periumbilical veins → superior epigastric vein → internal thoracic vein → subclavian vein → superior vena cava or

Portal vein ← umbilical vein (patent part) → paraumbilical veins → periumbilical veins →inferior epigastric vein → external iliac vein → inferior vena cava.

Note: Drainage from paraumbilical veins into the superficial veins (rare) of the anterior abdominal wall (thoracoepigastric vein, lateral thoracic vein, superficial epigastric vein, see A) leads to dilation of these tortuous veins (Medusa head, caput medusae).

③ Through veins of the posterior abdominal wall:

Portal vein ← superior and inferior mesenteric vein ← left and right colic veins → left and right ascending lumbar veins → azygos/hemiazygos vein → superior vena cava. The ascending lumbar veins may also divert blood to the inferior vena cava.

④ Through the rectal venous plexus (with dilation):

Portal vein ← inferior mesenteric vein ← superior rectal vein ← middle/inferior rectal veins → internal iliac vein → inferior vena cava.

2.6 Lymphatic Trunks and Lymph Nodes

A Overview of parietal lymph nodes in the abdomen and pelvis

Anterior view of an opened female abdomen. All visceral structures have been removed except for major vessels, and the lymphatic vessels are shown larger for clarity. Size disparities between the lymph nodes (1 mm to over 1 cm) and actual numbers (several hundred) are ignored. Regional lymph nodes (see C) may be arranged so densely that individual groups can scarcely be identified. Lymph nodes in the abdomen and pelvis are classified by their location as parietal or visceral. Parietal lymph nodes are located near the trunk wall (often distributed along blood vessels), while visceral lymph nodes are located near organs in the connective tissue of the extraperitoneal space or in the mesentery attached to an organ. A large percentage of parietal lymph nodes are located on the posterior wall of the abdomen and pelvis: they are clustered around the large vessels that course on the posterior abdominal and pelvic walls, such as the abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava in the abdomen and the iliac arteries and veins and their branches in the pelvis. Only a few lymph nodes are located on the anterior wall, such as the inguinal lymph nodes and the nodes around the external iliac artery (iliac lymph nodes). The lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels are arranged in an intricate network in the abdomen and pelvis, as they generally are elsewhere in the body. As a result, lymphatic drainage tends to follow multiple regional patterns of flow rather than a single well-defined pathway (see p. 222). Potential drainage routes are particularly numerous for the organs of the pelvis, where several organs may share lymphatic pathways. For example, certain lymph nodes are utilized (with varying degrees of preference) by the bladder, genital organs, and rectum.

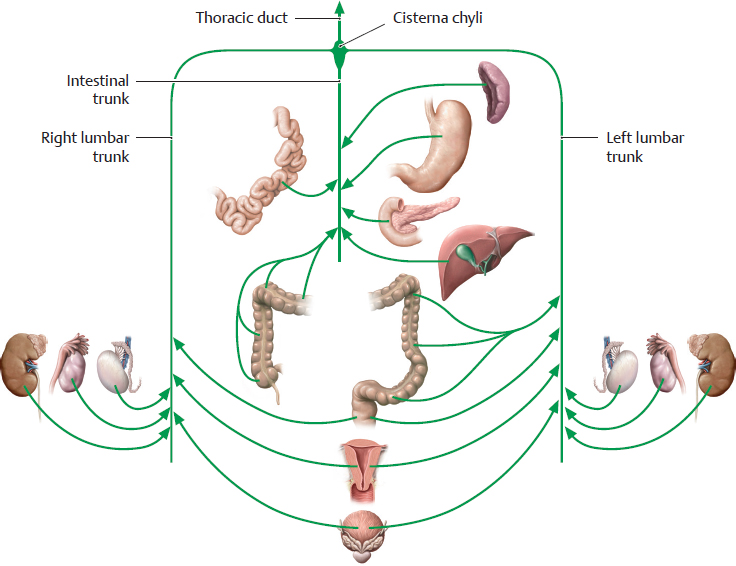

B Lymphatic trunks in the abdomen and pelvis

Lymph from the abdominal and pelvic organs drains to the lumbar and intestinal trunks (see p. 222) after first passing through one or more lymph node groups (see C). An expansion, the cisterna chyli, is frequently present at the union of these trunks. Lymph from the cisterna chyli drains through the thoracic duct to the junction of the left subclavian and internal jugular veins. The thoracic duct is the principal lymphatic trunk that returns lymph to the venous system.

C Lymph node groups in the abdomen and pelvis

Before lymph from the organs of the abdomen and pelvis enters the lymphatic trunks, it is filtered by lymph nodes that collect the lymph from a particular organ (or region). After leaving the regional nodes, the lymph drains to collecting lymph nodes. These are the nodes that collect lymph from several lymph node groups and carry it to the lymphatic trunks. In the abdomen and pelvis, these are the lumbar and intestinal trunks.

Note: One lymph node may function as a regional lymph node for various organs, but at the same time it may collect lymph from several regional nodes, functioning also as a collecting lymph node. This principle is illustrated in the abdomen and pelvis by the lumbar lymph nodes: They function as regional lymph nodes for the kidneys, suprarenal glands, gonads, and adnexa (see p. 314) and as collecting lymph nodes for the iliac nodes.

D Lymph node groups and tributary regions

Lymph node groups and collecting lymph nodes |

Location (see C) |

Organs or organ segments that drain to these lymph node groups (tributary regions) |

Celiac lymph nodes |

Around the celiac trunk |

Distal third of esophagus, stomach, greater omentum, duodenum (superior and descending parts), pancreas, spleen, liver, and gallbladder |

Superior mesenteric lymph nodes |

At the origin of the superior mesenteric artery |

Second through fourth parts of duodenum, jejunum and ileum, cecum with vermiform appendix, ascending colon, transverse colon (proximal two-thirds) |

Inferior mesenteric lymph nodes |

At the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery |

Transverse colon (distal third), descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum (proximal part) |

Lumbar lymph nodes (right, intermediate, left) |

Around the abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava |

Diaphragm (abdominal side), kidneys, suprarenal glands, testis and epididymis, ovary, uterine tube, uterine fundus, ureters, retroperitoneum |

Iliac lymph nodes |

Around the iliac vessels |

Rectum (anal end), bladder and urethra, uterus (body and cervix), ductus deferens, seminal vesicle, prostate, external genitalia (via inguinal lymph nodes) |

2.7 Overview of the Lymphatic Drainage of Abdominal and Pelvic Organs

A Principal lymphatic pathways draining the digestive organs and spleen

Lymph from the spleen and most of the digestive organs drains directly from regional lymph nodes or through intervening collecting lymph nodes to the intestinal trunks. Exceptions are the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and the upper part of the rectum, which are drained by the left lumbar trunk. The organs and visceral lymph nodes in the above schematic are served mainly by three large collecting stations (individual lymph nodes see p. 280 ff):

• Celiac lymph nodes: collect lymph from the stomach, duodenum, pancreas, spleen, and liver. Topographically and at dissection, they are often indistinguishable from the regional lymph nodes of nearby upper abdominal organs.

• Superior mesenteric lymph nodes: collect lymph from the jejunum, ileum, ascending colon, and transverse colon.

• Inferior mesenteric lymph nodes: collect lymph from the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum.

These collecting lymph nodes drain principally through the intestinal trunks to the cisterna chyli. There is also an accessory drainage route to the cisterna chyli by way of the left lumbar lymph nodes.

The lymphatic drainage of the rectum is described on p. 283.

B Principal lymphatic pathways draining the organs of the retroperitoneum and pelvis (and lower limb)

Lymph from these organs drains principally to the right and left lumbar trunks. The following are important lymph node groups for the organs of the retroperitoneum and pelvis (and lower limb):

• Common iliac lymph nodes: collect lymph from the pelvic organs and lower limb.

• Right and left lumbar lymph nodes: collecting lymph nodes for the common iliac nodes, also regional lymph nodes for the organs of the retroperitoneum and the gonads, although the latter are located in the pelvis or scrotum. As the gonads undergo their developmental descent, they maintain their lymphatic connection to the lumbar lymph nodes (analogous to their blood supply, see p. 350). As a result, when tumors of the testis (or ovary), for example, undergo lymphogenous spread, they tend to metastasize directly to the abdomen rather than to the pelvis.

Both the iliac lymph nodes and the lumbar lymph nodes are classified as parietal nodes, a category that includes the phrenic and epigastric nodes. Lymph nodes such as the pararectal and parauterine lymph nodes are classified as visceral nodes.

2.8 Autonomic Ganglia and Plexuses

A Overview of autonomic ganglia and plexuses in the abdomen and pelvis

Anterior view of an opened male abdomen and pelvis with all of the peritoneum removed. Almost all of the stomach has been removed, and the gastric stump and esophagus have been pulled slightly inferior. The pelvic organs have been removed except for a rectal stump. The autonomic nervous system forms extensive plexuses and a number of ganglia around the abdominal aorta and within the pelvis, the ganglia marking the sites where the first presynaptic neuron synapses with the second postsynaptic neuron. All of the autonomic plexuses in front of and alongside the abdominal aorta are collectively termed the abdominal aortic plexus. This structure also includes the individual plexuses located at the origins of the paired and unpaired branches of the abdominal aorta (see B). As a general rule, sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers come together in the plexuses on their way to the target organ. Note: The left and right vagus nerves are organized around the esophagus to form the anterior and posterior vagal trunks. Both trunks contain fibers from both vagus nerves, the anterior vagal trunk containing more fibers from the left vagus nerve, the posterior trunk containing more fibers from the right vagus nerve. While the anterior vagal trunk generally terminates at the stomach, the posterior vagal trunk goes on to supply the entire small intestine and the large intestine approximately to the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the transverse colon.

B Organization of autonomic ganglia and plexuses in the abdomen and pelvis

The ganglia and plexuses of the autonomic nervous system are named for the arteries that they accompany or around which they are distributed (e.g., the celiac ganglion and mesenteric plexus). In the sympathetic system, the presynaptic neuron synapses with the postsynaptic neuron in ganglia distant from the organs (or ganglion cells in a plexus distant from the organs); in the parasympathetic system, this synapse occurs in ganglia near the organs (or ganglion cells in a plexus near the organs). Thus, the parasympathetic ganglia are usually located on the target organ or in its wall, where they receive branches from the vagal trunks or pelvic splanchnic nerves.

Note: Even plexuses may contain aggregations of ganglion cells, sometimes very small. An example is the renal plexus, which contains the renal ganglia (too small to be shown in the drawing). The autonomic plexuses contain efferent (visceromotor) fibers as well as numerous afferent (viscerosensory) fibers for both their sympathetic and parasympathetic components.

2.9 Organization of the Sympatheticand Parasympathetic Nervous Systems

A Organization of the sympathetic nervous system in the abdomen and pelvis

The first, or presynaptic, neurons of the sympathetic system that supply the organs of the abdomen are located in the lateral horns of spinal cord segments T 5–T 12. Their presynaptic axons pass without synapsing through the ganglia of the sympathetic trunk and form the thoracic splanchnic nerves (greater and lesser thoracic splanchnic nerves, and occasionally a least thoracic splanchnic nerve from T 12). The synapse with the second, or postsynaptic, neuron is located in the celiac ganglion, the superior (or inferior) mesenteric ganglion, or the aorticorenal ganglion (see p. 287).

The first, or presynaptic, neurons of the sympathetic system that supply the organs of the pelvis are located in the lateral horns of spinal cord segments L 1 and L 2. Their presynaptic axons pass through the lumbar ganglia of the sympathetic trunk and form the lumbar splanchnic nerves. The synapse with the second, or postsynaptic, neuron may be located in the lumbar ganglia, inferior mesenteric ganglion, or inferior hypogastric plexus. Beyond that point the postsynaptic fibers of the postsynaptic neuron generally pass to the target organ with its artery, usually accompanied by parasympathetic fibers of the autonomic nervous system.

Note: The peripheral ganglia of the sympathetic nervous system are distributed along the sides of the vertebral column (paravertebral). Peripheral ganglia in the abdomen and pelvis are also placed anterior to the vertebral column (prevertebral) and sacrum.

The paravertebral ganglia are interconnected by interganglionic connections to form the sympathetic trunk—two long pathways extending along each side of the vertebral column. The ganglia are named for the corresponding levels of the spine (thoracic ganglia, lumbar ganglia, etc.) and are variable in number. The prevertebral ganglia are located at the origins of the major arteries from the abdominal aorta and are named accordingly (celiac ganglion, superior and inferior mesenteric ganglia, etc.).

B Effects of the sympathetic nervous system on organs in the abdomen and pelvis

Organ, organ system |

Sympathetic nervous system effects |

• Gastrointestinal tract |

|

– Longitudinal and circular muscle fibers |

Decreased motility |

– Sphincter muscles |

Contraction |

– Glands |

Decreased secretions |

• Splenic capsule |

Contraction |

• Liver |

Increased glycogenolysis/gluconeogenesis |

• Pancreas

– Endocrine pancreas

– Exocrine pancreas |

Decreased insulin secretion

Decreased secretion |

• Bladder

– Detrusor vesicae

– Functional bladder sphincter |

Relaxation

Contraction |

• Seminal vesicle |

Contraction (ejaculation) |

• Ductus deferens |

Contraction (ejaculation) |

• Uterus |

Contraction or relaxation, depending on hormonal status |

• Arteries |

Vasoconstriction |

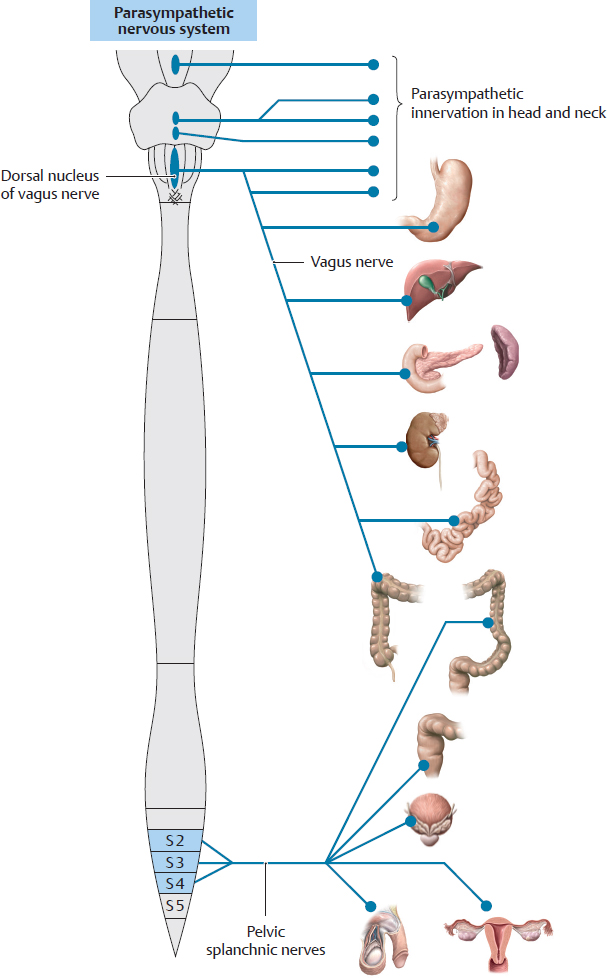

C Organization of the parasympathetic nervous system in the abdomen and pelvis

Contrasting with the thoracolumbar organization of the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system in the abdomen and pelvis consists of two topographically distinct systems: a cranial part and a sacral part. This system also differs from the sympathetic nervous system in that the synapse of the first, or presynaptic, neuron with the second or postsynaptic neuron is located in the intramural ganglia of the organ walls.

• Cranial part of the parasympathetic nervous system in the abdomen and pelvis: The presynaptic neuron is located in the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve (i.e., the nucleus of cranial nerve X in the medulla oblongata). The axons (presynaptic nerve fibers) course with the vagus nerve to visceral or intramural ganglia, where they synapse with the postsynaptic neuron. The distribution of the cranial part includes the stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, duodenum, kidney, suprarenal gland, small intestine, and the large intestine from the ascending colon to near the left colic flexure.

• Sacral part of the parasympathetic nervous system in the abdomen and pelvis: Its origin is located in the lateral horns of spinal cord segments S2–S4 (sacral intermediolateral nucleus). The axons (presynaptic nerve fibers) run a very short distance with spinal nerves S2–S4, then separate from them and course as the pelvic splanchnic nerves to ganglion cells in the inferior hypogastric plexus or organ wall, where they synapse with the postsynaptic neuron. The distribution of the sacral part of the parasympathetic nervous system in the abdomen and pelvis includes left colic flexure, the descending and sigmoid colon, rectum, anus, bladder, urethra, and the internal and external genitalia.

D Effects of the parasympathetic nervous system on organs in the abdomen and pelvis

Organ, organ system |

Parasympathetic nervous system effects |

• Gastrointestinal tract |

|

– Longitudinal and circular muscle fibers |

Increased motility |

– Sphincter muscles |

Relaxation |

– Glands |

Increased secretions |

• Splenic capsule |

– |

• Liver |

– |

• Pancreas |

|

– Endocrine pancreas |

– |

– Exocrine pancreas |

Increased secretion |

• Bladder |

|

– Detrusor vesicae |

Contraction |

– Functional bladder sphincter |

– |

• Seminal vesicle |

– |

• Ductus deferens |

– |

• Uterus |

– |

• Arteries |

Vasodilation of the arteries in the penis or clitoris (erection) |

Note the special role played by the suprarenal medulla and kidneys: the suprarenal medulla is phylogenetically and functionally analogous to a “sympathetic ganglion.” It is thus part of the sympathetic nervous system and is therefore not listed in this table. The renal vessels are not regulated by the sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous systems, but by autoregulation (occurs only for renal blood flow). For functional reasons, the kidneys self-regulate renal blood pressure.