We can trace without a break, always following out the same law, the evolution of man from the mammal, the mammal from the reptile, the reptile from the amphibian, the amphibian from the fish, the fish from the arthropod, the arthropod from the annelid [segmented worms], and we may be hopeful that the same law will enable us to arrange in orderly sequence all the groups in the animal kingdom.

—Walter Gaskell, The Origin of Vertebrates

Most people don’t get too excited about evolution in sand dollars, snails, scallops, or microfossils. But they are far more interested in where our group, the vertebrates, came from. For this transition, there is abundant evidence not only from the fossil record but also from embryology and from a number of “living fossils” that preserve the steps in the evolution of vertebrates and are still alive today.

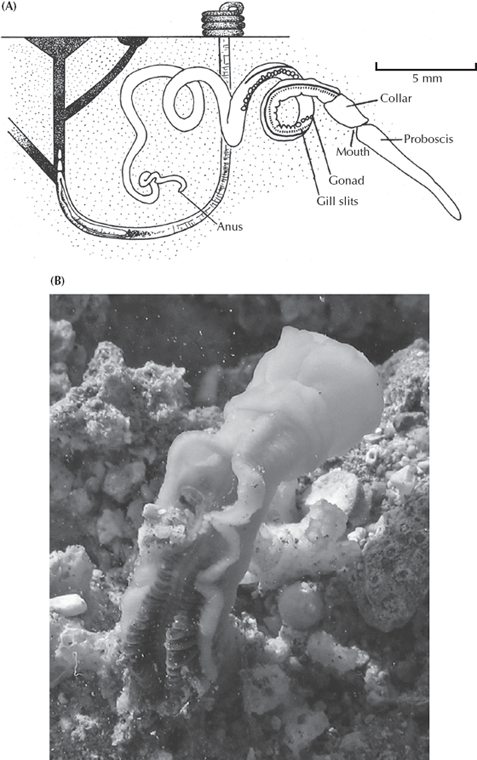

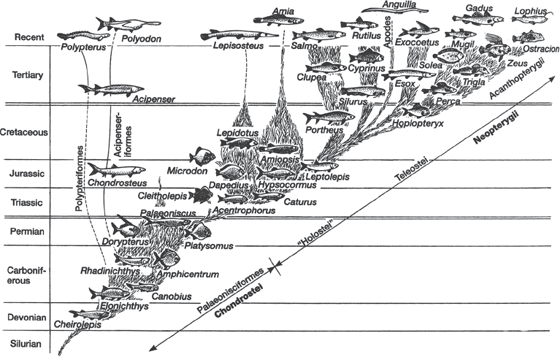

Humans are members of the phylum Chordata. This group includes the vertebrates (animals with a true backbone and other kinds of bone as well) such as mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish (fig. 9.1). The Chordata also includes a variety of near-vertebrates that have some of the specializations of vertebrates but do not have a backbone. Many of these near-vertebrates have a long flexible rod of cartilage known as the notochord instead of the bony backbone; this defines the group known as the phylum Chordata. When you were an embryo, you had a notochord before the cartilage was replaced by the bone of your adult spinal column.

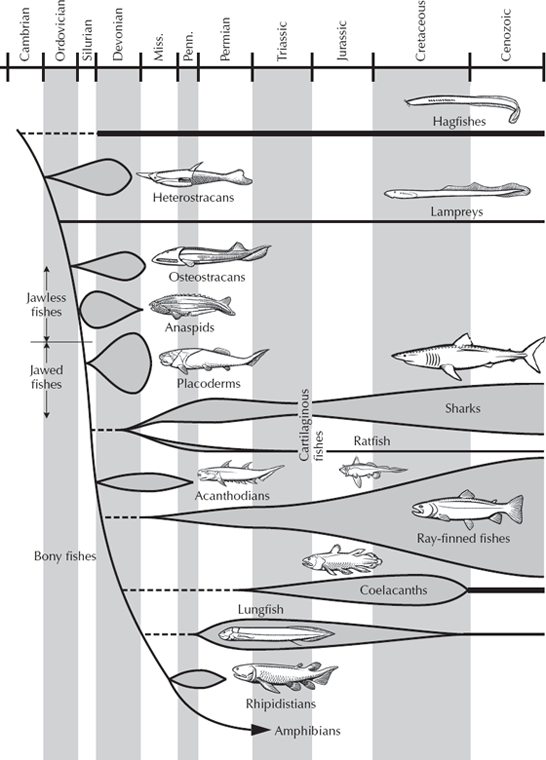

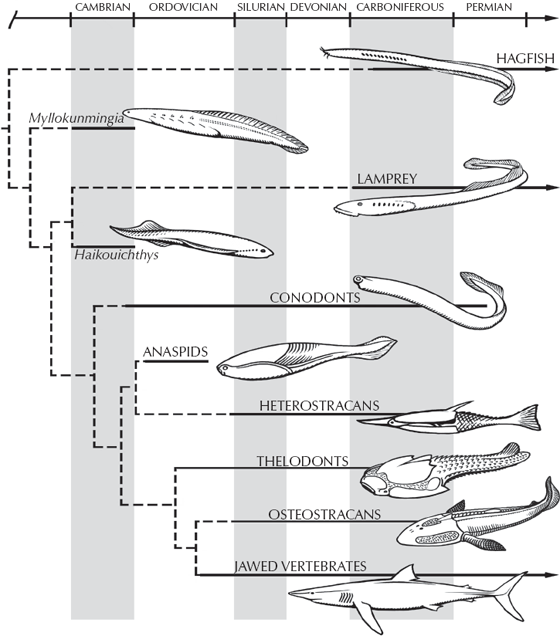

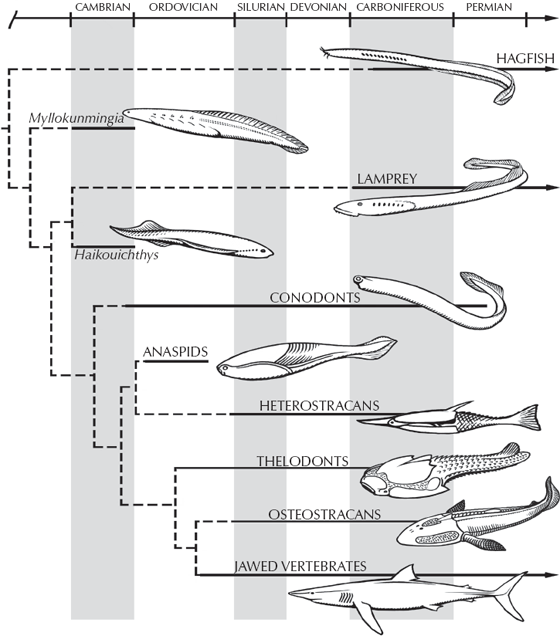

FIGURE 9.1. Evolutionary history of fishes and other early vertebrates. (Drawing by Carl Buell)

Where do chordates come from? For over a century, all the anatomical and embryological evidence (and more recently, all the molecular evidence as well) clearly shows that our closest relatives among living animals are the echinoderms—the sea star, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers. You may not think of the sea star as your close relative (or even think of it as an animal), but that’s what the biological facts clearly show. The most striking demonstration of this comes from our embryology. When you were a simple ball of cells (blastula) just a few cleavages after you were formed by fertilization, there was a small opening in the ball called a blastopore. If you had been an embryo of a worm or an arthropod, your blastopore would have developed into the mouth end of your digestive tract. But in the deuterostomes (echinoderms plus chordates), the blastopore becomes the anus, and the mouth develops on the opposite side of the blastula. There are many other embryological similarities as well. The cells in the fertilized egg in most animals cleave in a spiral pattern, but those in deuterostomes do so in a radial pattern. Deuterostome embryos have cells that are indeterminate, meaning that their fates are not determined at the very beginning (as in most animals) but can become part of a new organ or even regenerate an organ if necessary. If you break up the larvae of a sea urchin early in development, each ball of cells can turn into a complete animal. Finally, the internal fluid-filled body cavity (the coelom) of the Deuterostomata forms from an outpocketing of the inner layer of cells, or endoderm, rather than from a split in the middle layer of cells, or mesoderm, as occurs in worms and arthropods.

All of these unique specializations show that the echinoderm and chordate larval pattern is the common link between these two very different phyla of animals. And in the past 20 years, every molecular system that has been examined confirms that the Deuterostomata is a natural monophyletic group, so there’s no longer any doubt among biologists that sea stars and sea urchins are among our close relatives. From the common larval pattern, one set of developmental commands begins to produce the larvae of echinoderms, and another set of pathways produces the classic chordate embryo. We would not expect to find these fragile embryos preserved in the fossil record, but just a few years ago, a remarkable discovery of late Precambrian embryos was found in Doushantuo, China, which seem to show that our earliest common ancestors lived around 600–700 million years ago (as the molecular clock estimates also suggest).

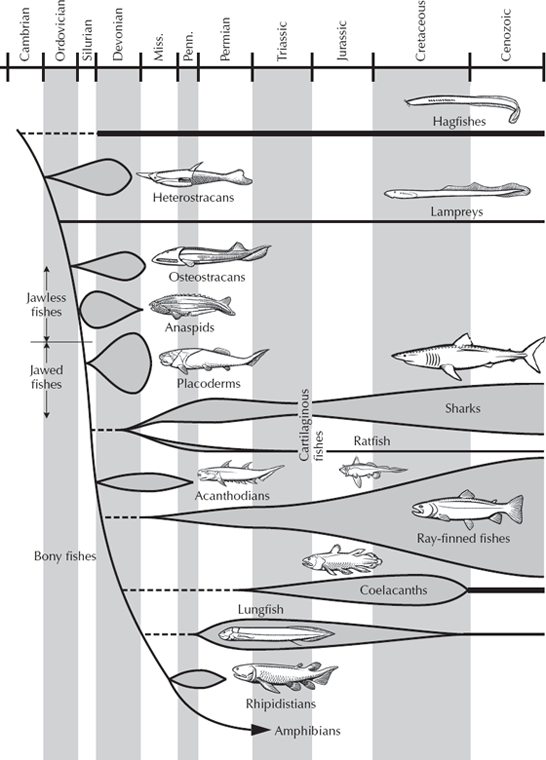

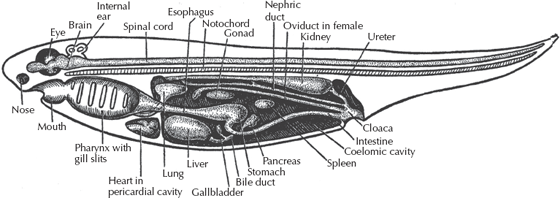

What defines a chordate besides the notochord? At one end of the basic chordate body plan (fig. 9.2) are the sensory organs (eyes, nostrils) and a mouth opening into a throat cavity known as the pharynx. In humans, the pharynx houses the vocal cords, but in fish the pharynx is the region of the gills and gill basket, and in some groups, feeding takes place in the pharynx as well. Chordates are also distinctive in that they have a nerve cord along the back, above the notochord, and the digestive tract along the belly, below the notochord. By contrast, annelids and arthropods have their digestive tract along their backs and their main nerve cord along their bellies. Finally, many chordates have a long row of segmented V-shaped muscles known as myomeres that pull and flex the notochord and allow the side-to-side swimming motion found in nearly all fish. Last but not least, chordates differ from worms in that the digestive tract ends with an anus not at the very end of the body (as in worms and arthropods), but only partway back; the tail (composed of notochord and myomeres) usually extends behind the anus.

FIGURE 9.2. The basic organization of the chordate body plan. The front part of the body has the sense organs (eyes, nose) and a mouth with a pharyngeal basket for filtering out food and oxygen. The nerve cord and notochord run along the back, while the digestive tract runs along the belly. The anus is not at the rear tip of the body, but midway down the body, with a long tail and V-shaped segmented muscles (myomeres) running the length of the body. (After Romer 1959; reprinted with permission of the University of Chicago Press)

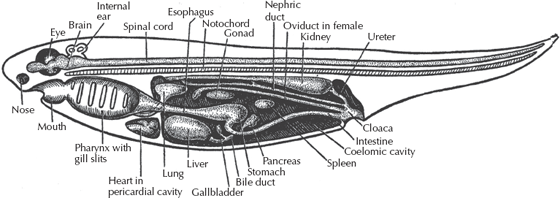

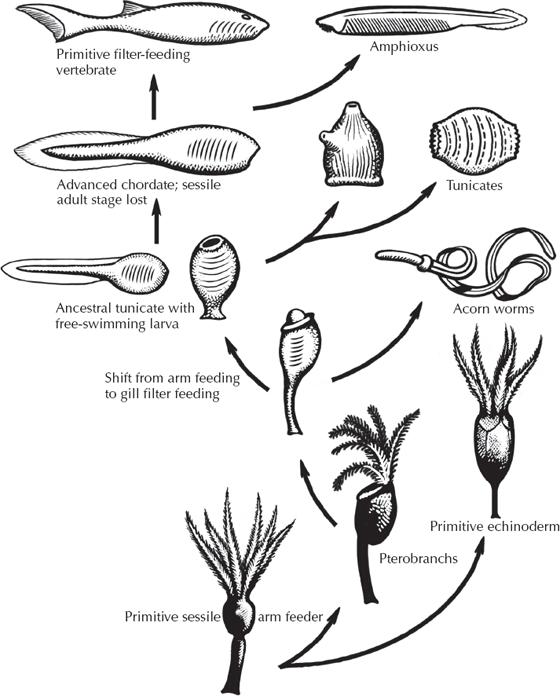

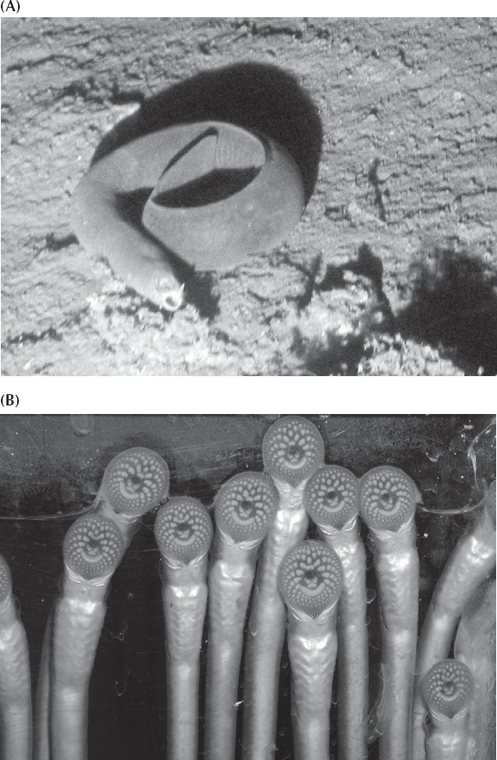

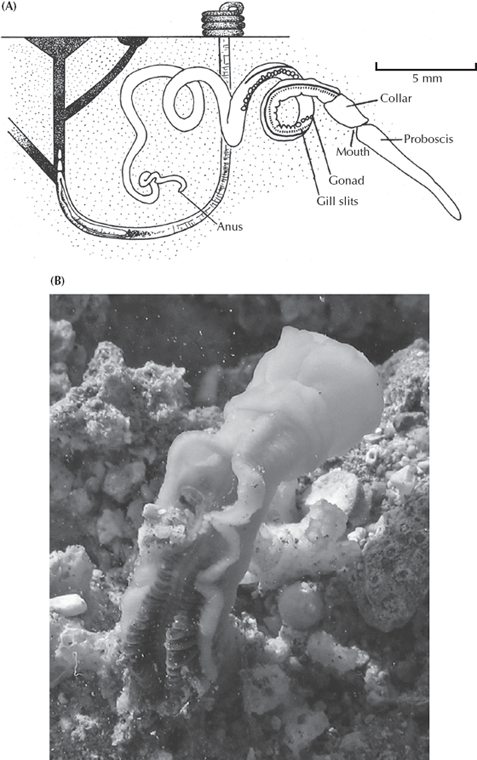

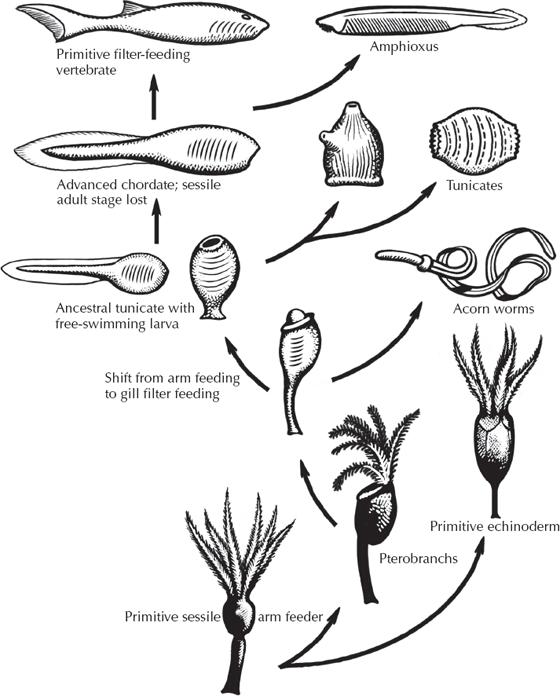

With these basic parts of the chordate body plan outlined, we can now look at the steps that produced a vertebrate from a nonvertebrate deuterostome (fig. 9.3). The most primitive living relatives of the chordates belong to a closely related phylum, the Hemichordata (“half chordates”). Today these include the acorn worms (fig. 9.3) and a group of plankton feeders known as pterobranchs that bear little resemblance to vertebrates. Acorn worms are known from about 80 species that live in U-shaped burrows in the sand and use their muscular proboscis to dig and the collar behind it to trap food particles as they burrow. Pterobranchs, on the other hand, are tiny colonial animals that live on long ringed tubes, and the animal consists largely of a U-shaped digestive tract with a fanlike filter-feeding device at one end. To the casual person walking among the tide pools or the beach sand, neither of these creatures resembles a fish, let alone a human. Yet careful examination of these animals reveals important clues. Although hemichordates do not yet have a notochord, they have the embryonic precursor of the notochord. In addition, both groups have a true pharynx, which occurs in no other group but chordates and their relatives. Finally, they have nerve cords along the back, and the digestive tract along the belly, a configuration that occurs elsewhere only in chordates.

FIGURE 9.3. The hemichordates include the pterobranchs and the acorn worm (shown here). This creature looks superficially wormlike but has the chordate feature of a pharynx with gill slits, and the precursors of a notochord, as well as a dorsal nerve cord and ventral digestive tract (the reverse of all other true “worms”). Behind the acorn worm is a sketch of its burrow, and the castings that it leaves outside the tail end of the burrow. (Part (A) redrawn after Barnes 1986; (B) courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

There is also a lot of embryological evidence that hemichordates are our closest relatives. Their distinctive tornaria larva is nearly identical to the larvae of primitive chordates and also very similar to some echinoderm larvae. All the recent molecular analyses consistently show hemichordates as our closest relative other than echinoderms, or slightly closer to echinoderms but also clustered with chordates. Finally, acorn worms don’t fossilize, but the extinct relatives of the pterobranchs, known as graptolites, are extremely common in early Paleozoic rocks. Once again, we have convergence of evidence from anatomy, embryology, paleontology, and molecular biology that points to one conclusion. Although we may not like to think of ourselves as having evolved from a creature like the acorn worm or pterobranch, that’s where the evidence leads.

FIGURE 9.4. A diagrammatic family tree showing how chordates evolved from more primitive forms, as postulated by Walter Garstang and Alfred S. Romer. In many cases, such as the transition from hemichordates to tunicates (“sea squirts”), or tunicates to higher chordates, the larval form with its swimming tail enables them to escape the dead end of their highly specialized adult body forms. (After Romer 1959, redrawn by Carl Buell)

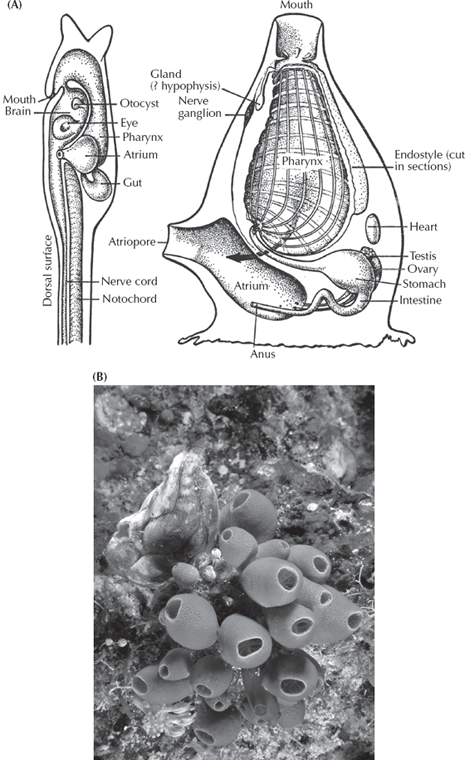

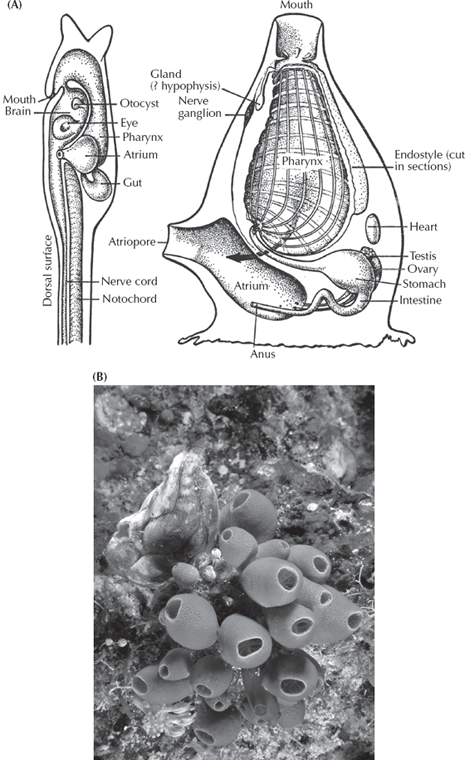

How do we get to the next stage? According to one hypothesis (fig. 9.4), the ancestral larvae that we chordates share with echinoderms developed into the filter-feeding pterobranchs (much like the primitive filter-feeding echinoderms). By retaining the embryonic stages of pterobranchs, the filtering arms were lost, and an acorn worm develops from the embryo instead. The next step is known as the “sea squirts” or the tunicates (fig. 9.5), which today are represented by over 2,000 species in the ocean, although they are so tiny and translucent that most people never see one. These delicate little blobs of jelly hardly resemble us, or even a fish for that matter. As adults, they are shaped like a little sac, with an opening at the top through which water is sucked in, then filtered through a basketlike pharynx, and finally out the little “chimney” on the side of their body. The adult sea squirt doesn’t suggest much about chordates at all, although the pharynx is a clue. But the best evidence comes from their larvae (fig. 9.5A, left diagram), which look nothing like the adult but instead a lot like a fish or a tadpole. The sea squirt larva has a well-developed notochord, a muscular tail with paired myomere muscles, a nerve cord on the back, and a digestive tract along the belly. This peculiar larva swims around looking for a good rocky surface on which to land. Using the adhesive pad on its snout, it attaches and within 5 minutes the tail begins to degenerate. About 18 hours later the metamorphosis into the adult sea squirt is complete.

FIGURE 9.5. (A) The tunicates, or “sea squirts,” have adult body forms (right diagram) that look nothing like chordates. However, the larvae (left diagram) are free-swimming tadpole-like creatures with tails and a pharynx, that allowed them to escape their adult dead-end body form and evolve into higher chordates. (After Romer 1959, redrawn by Carl Buell) (B) Photograph of the adult tunicate in feeding position. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

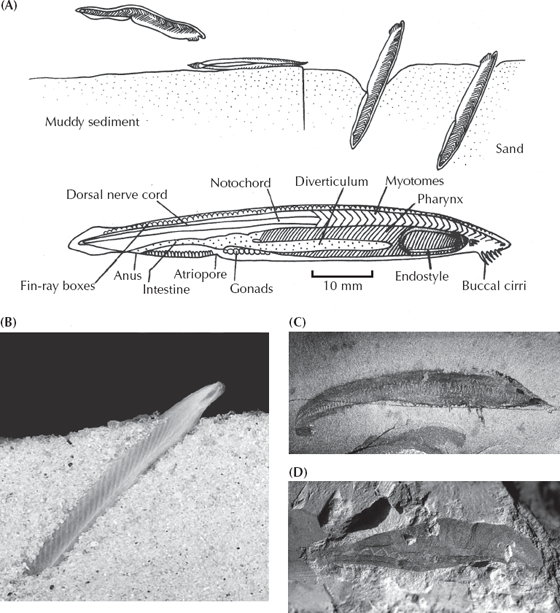

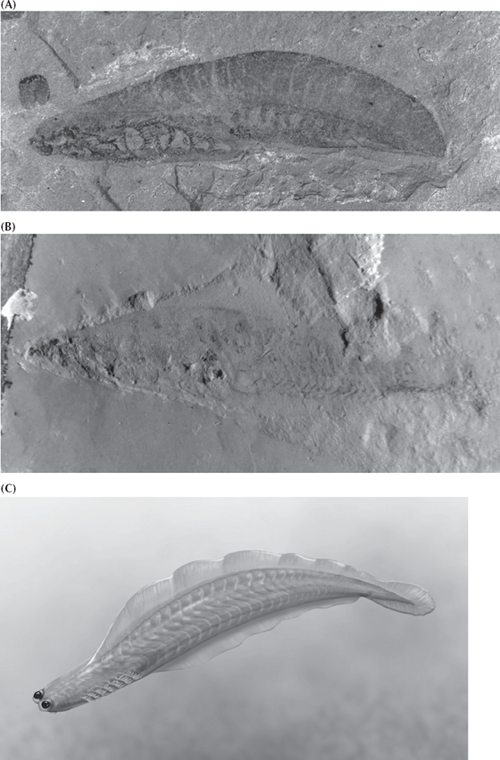

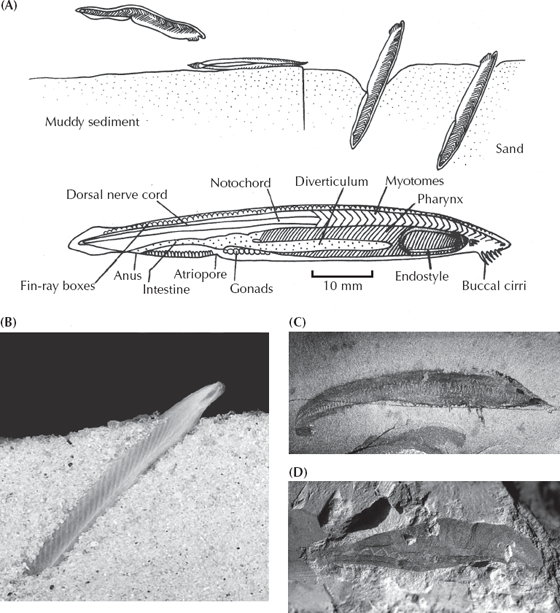

The adult sea squirt, of course, is too specialized to have had much to do with our ancestry, but the larva is a different matter. Through a mechanism like neoteny (discussed in chapter 3), the next stage of evolution of chordates would come not from the adults but from organisms that retain the features found in the juveniles but never metamorphose into adults. And indeed the next step (fig. 9.4) is not much more advanced than the sea squirt larva. Known as the lancelet or amphioxus, it looks more and more like the primitive jawless fish (fig. 9.6). This little sliver of flesh is usually only a few inches in length and swims much like an eel, although it does not have a true head, jaws, teeth, or bones. Adult lancelets (fig. 9.6A and B) burrow tail-first into the sandy sea bottom and then use the tentacles around the mouth and pharynx to filter feed. But the anatomy of these animals bears a remarkable resemblance to primitive fish. Lancelets have a well-defined notochord, a nerve cord along the back, a digestive tract along the belly, and many V-shaped myomeres down the length of the body. Their pharyngeal basket is well developed, with over a 100 “gill slits” like those of a primitive fish. In addition, they are the most primitive chordates to have a liver and a kidney, as well as other organ systems not found in hemichordates or sea squirts. They do not have true eyes, but they do have light-sensitive pigment spots on the front of the head to detect light and shadows. The molecular and embryological evidence consistently puts lancelets as our closest nonvertebrate chordate relatives. To top it off, even these delicate animals fossilize occasionally. The Burgess Shale produces a remarkable fossil known as Pikaia (fig. 9.6C), which is a very primitive relative of the lancelets. The Cambrian Chengjiang fauna of China yields another form known as Yunnanozoon (fig. 9.6D). And in rocks from the Permian of South Africa, there a fossil known as Palaeobranchiostoma that looks much like the living lancelet.

FIGURE 9.6. (A) The lancelets, or amphioxus (Branchiostoma) are the most fishlike and specialized of the nonvertebrate chordates. They have a long eellike body with muscles running down the entire length and a notochord supporting the entire body, but the mouth is still a simple filter-feeding pharynx. In life (top diagram) they embed themselves in the sediment with their heads protruding, catching tiny food particles with their mouth filter feeding in the current. (After Barnes 1986, drawn by Carl Buell) (B) Photograph of the living lancelet. (From IMSI Photo Images, Inc.) (C) The middle Cambrian Burgess Shale fossil lancelet Pikaia. (D) The Early Cambrian Chengjiang lancelet fossil known as Yunnanozoon. ([C and D] photos courtesy D. Briggs)

Oh a fish-like thing appeared among the annelids one day

It hadn’t any parapods nor setae to display

It hadn’t any eyes or jaws or ventral nervous chord,

But it had a lot of gill slits and it had a notochord.

It’s a long way from Amphioxus

It’s a long way to us,

It’s a long way from Amphioxus

To the meanest human cuss.

Well, it’s good-bye to fins and gill slits, And it’s welcome lungs and hair,

It’s a long, long way from Amphioxus

But we all came from there.

My notochord shall change into a chain of vertebrae,

And as fins my metaplural folds shall agitate the sea;

My tiny dorsal nervous chords shall be a mighty brain,

And the vertebrae shall dominate the animal domain.

—Philip Pope, to the tune of “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”

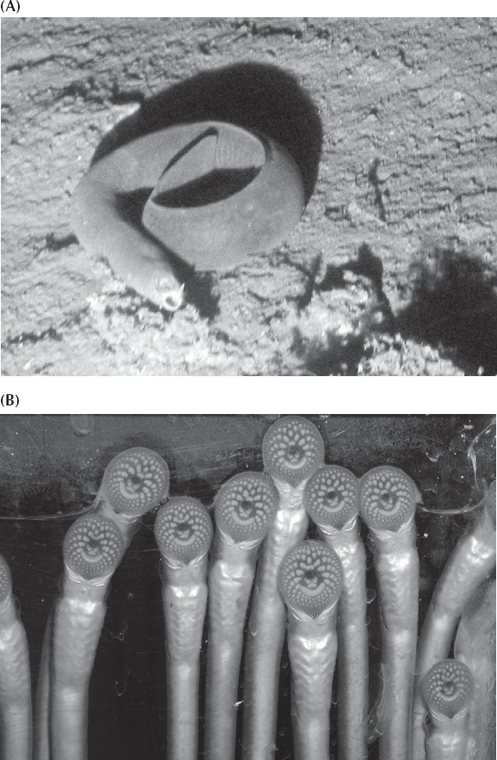

From the primitive chordates like the Cambrian lancelets Pikaia and Yunnanozoon, the next evolutionary step is the jawless fish, which are known from both fossils and living forms. Two groups of living jawless vertebrates are known, and these give us many insights into the fossils. The more primitive of the two is the hagfish (fig. 9.7A), commonly known as the “slime eel” because it can produce copious amounts of mucus to escape predators. Hagfish burrow on the seafloor, slurping up worms, and wriggle into the bodies of dead and dying fish, eating them from the inside out with their rasping teeth. Hagfish are the most primitive chordates that have a definite head region with a brain, sense organs (eyes, nose, and ears), and a full skeleton made of cartilage, not just a notochord. They also have a two-chambered heart and distinctive cells in embryology known as neural crest cells, which are crucial in vertebrate development. But hagfish lack more advanced features, such as bone, red blood cells, a thyroid gland, and many other characters found in the other living jawless vertebrate, the lamprey (fig. 9.7B). Although lampreys look superficially like eels, they are jawless. They live as parasites by attaching to the side of a fish with their suction cup mouth and using their rasping teeth to suck the fluids out of their host.

FIGURE 9.7. Two examples of living jawless craniates. (A) The living hagfish, Myxine. (Photo courtesy NOAA) (B) The living lamprey, shown here clinging to glass with its sucker-like mouth and displaying its rasping teeth, which it uses to eat a hole in the side of its prey. (Photo courtesy J. Marsden)

These two unsavory characters may not be our favorite cousins, but they are the only jawless vertebrates alive today. However, the fossil record shows that jawless vertebrates had quite a successful run. We can trace them back to the Cambrian, where we find soft-bodied impressions in China (Shu et al. 1999) that have been named Myllokunmingia, Haikouella, and Haikouichthys (figs. 9.8 and 9.9). These recent discoveries push the earliest vertebrates all the way back to the Early Cambrian, much earlier than previous fossils (which were based on fragments of dermal armor known from the Late Cambrian). Through the rest of the Cambrian and Ordovician, we see nothing more in the fossil record of vertebrates other than isolated plates made of true bone and the microscopic toothlike structures known as conodonts, so apparently the earliest vertebrates remained small and completely soft-bodied for some time. Then in the Early Silurian, about 430 million years ago, we find the first nearly complete armored jawless fish, and this group radiates into an explosion of diversity by the Late Devonian. This Devonian radiation of jawless fish (fig. 9.1) was spectacular, with a wide variety of armored fish that still lacked jaws or a muscular bony skeleton, but nonetheless they were covered in solid bone all over their bodies; some had large curved head shields to protect them and “chain mail” down to their tails. None, however, had a strong pectoral or pelvic fin for steering, as do most modern fish, because they lacked bone to support the fin. Instead, armor covered much of their bodies, although no one is sure what predator they needed all that armor for. Some of these jawless fish, the cephalaspids or ostracoderms, had a large horseshoe-shaped head shield with a flat bottom, and apparently filtered out food from the seafloor. The heterostracans, thelodonts, and anaspids, on the other hand, had simple slit-like mouths and tails with the main lobe pointed downward to keep their heads up while they swam. These fish apparently sucked water through their mouths and filtered it through the gills, as many living fish do today.

FIGURE 9.8. The evolutionary history of the earliest vertebrates, showing the evolutionary position the new Chinese Cambrian fossils Myllokunmingia and Haikouichthys with respect to other jawless and jawed fish. (Redrawn by Carl Buell, based on Shu et al. 1999)

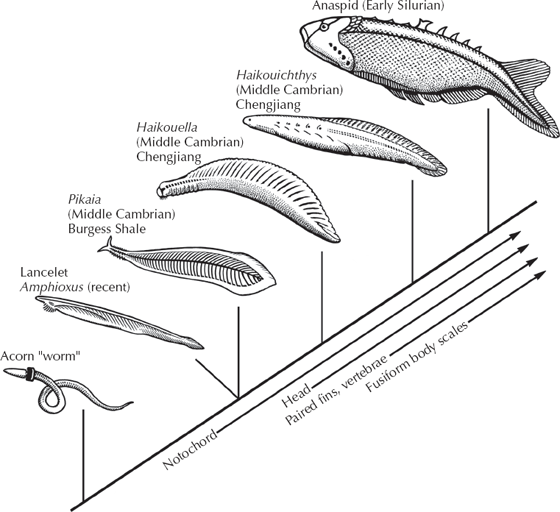

FIGURE 9.9. The steps in the evolution from primitive chordate relatives to the first vertebrates. (Redrawn by Carl Buell, based on Shu et al. 1999)

Thus, from the primitive acorn worms, we can trace a series of transitional forms that become more and more like vertebrates. Add the notochord and we have lancelets (fig. 9.9). Add the head and the paired fins and we have the early Cambrian Chinese forms Haikouella and Haikouichthys (figs. 9.9 and 9.10). Finally, by making the body more streamlined and adding bony scales, we have a jawless fish (fig. 9.8). Thus the transition from invertebrates to vertebrates is documented not only by living fossils but also by an increasingly good fossil record.

FIGURE 9.10. Early Cambrian soft-bodied vertebrates, the earliest known vertebrate fossils. (A) Haikouichthys. (B) Haikouella. (Photos courtesy D. Briggs and Jun Yuan Chen) (C) A reconstruction of Haikouichthys by Carl Buell.

The term “fish” is of value on restaurant menus, to anglers and aquarists, to stratigraphers and in theological discussions of biblical symbolism. Many systematists use it advisedly and with caution. Fishes are gnathostomes that lack tetrapod characteristics. We can conceptualize fishes with relative ease because of the great evolutionary gaps between them and their closest living relatives, but that does not mean they comprise a natural group. The only way to make fishes monophyletic would be to include tetrapods, and to regard the latter merely as a kind of fish. Even then, the term “fish” would be a redundant colloquial equivalent of “gnathostome” (or “craniate,” depending upon how far down the phylogenetic ladder one wished to go).

—John Maisey, “Gnathostomes”

One of the great evolutionary breakthroughs in vertebrate history was the origin of jaws. Before jaws appeared, vertebrates were severely limited in what they could eat (mostly filter feeding or deposit feeding or living as parasites like lampreys and hagfish), and thus in their lifestyles and body size. Jaws allowed vertebrates to grab and break up a food item, which in turn meant they could eat a wide variety of foods, from other fish to plants to mollusks and so on. This then allowed vertebrates to evolve into a great many different ecological niches and body sizes, including superpredators that ate all other kinds of marine life. Eventually, vertebrates used their jaws and teeth for many other things besides eating, including manipulating objects, digging holes, carrying material to build nests, carrying their young around, and making sound or speech.

Once jaws appeared in the Silurian, there was a tremendous evolutionary radiation (fig. 9.1) of different kinds of jawed vertebrates, or more properly, gnathostomes (which means “jawed mouth” in Greek). As the quote from John Maisey points out, we have been accustomed to using the word “fish” to describe most of these vertebrates, but that word has no meaning in systematics. Fish are simply vertebrates or gnathostomes that live in the water and are not land animals, or tetrapods. The group is ecological and paraphyletic and not a natural taxon whatsoever. However, for the purposes of this book, we will keep the terminology simple, recognizing that fish is a label of convenience and not some real biological entity.

The radiation of gnathostomes began with the dominant group in the Devonian, the extinct placoderms (fig. 9.1). These creatures had thick bony plates covering their head and shoulders, but the rest of the skeleton was made of cartilage. Some of them had sharp biting plates on the edge of their mouth shields and reached up to 10 meters (30 feet) long, the largest predator the world had seen up to that time. Others were weighted down with armor over the entire front half of their body (including jointed armor on their pectoral fins that resembled crab legs) and apparently ate small slow prey on the sea bottom. Still others developed flat bodies like rays and skates. All of these different body shapes evolved rapidly in the Devonian and then vanished at the end of that period.

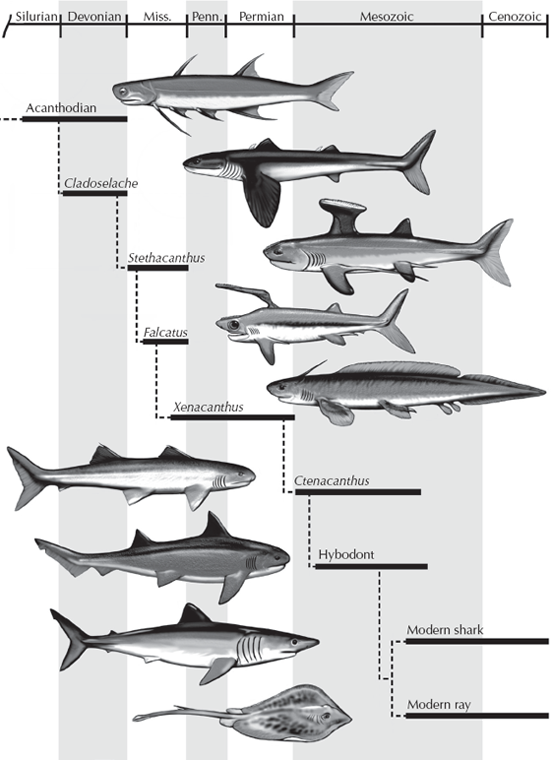

FIGURE 9.11. The evolution of the sharks. (Drawing by Carl Buell)

The next group to branch off the family tree of gnathostomes (figs. 9.1 and 9.11) were the sharks, or chondrichthyans (“cartilaginous fish”). We think of the terrors of the movie Jaws or the documentaries that feature sharks attacking divers, but sharks are actually much more complex and interesting than that. Most are highly effective predators with rows of razor-sharp teeth, but the largest sharks (whale sharks, megamouth sharks, and basking sharks) have tiny teeth and feed on plankton by filtering them through their gills. Other sharks are specialized mollusk eaters with crushing teeth, especially the flat-bodied skates and rays. Because shark skeletons are made of cartilage and do not fossilize well, we know them primarily from their teeth (which are made of bone and enamel) and often from the bony spines that many sharks had in their bodies and fins. Although the basic shark design has been successful for over 400 million years, sharks show considerable evolutionary change through time, contrary to the creationist books and websites (fig. 9.11). The earliest sharks, the cladodonts from the Devonian, had a large, very primitive “skull” (actually a cartilaginous precursor of the skull called a chondrocranium), very broad-based stiff pectoral fins, thick spines in front of their dorsal fins, and a rigid tail that was almost symmetrical. In the Mesozoic, the hybodont sharks are considerably more advanced, with a reduced, more flexible chondrocranium, pectoral fins with narrower bases that allowed more maneuverability, more specialized teeth, and a more flexible tail for powerful swimming. These trends are all continued in the living sharks, or the Neoselachii, which have a chondrocranium that is highly reduced, so they can protrude their upper and lower jaws very far; highly maneuverable pectoral fins; a wide variety of tooth types; and an even more flexible tail. Sharks may have been around for a long time, but they show considerable evolution during this history, and any creationist who claims otherwise has no familiarity with the real fossil record of sharks.

After the sharks and rays split off the family tree (fig. 9.1), the next groups up the cladogram are all known as osteichthyans, the “bony fish.” They break into two main groups: the “lobe-finned fish,” which include lungfish, coelacanths, and, of course, the tetrapods, to be discussed in the next chapter; and the “ray-finned fish,” so called because they support their fins with many long bony rays. Ray-finned fish make up about 98 percent of the species of living fish; only the hagfish, lamprey, lungfish, coelacanth, and chondrichthyans are not members of this group. Like the other main groups of fishes, ray-finned fish appeared in the Devonian, but they have been evolving rapidly ever since then, with hundreds of genera and thousands of species known from both the fossil record and the living world (figs. 9.12 and 9.13). As with sharks, the lineage has been around for 400 million years, but they show remarkable changes over that long history and major changes in the ways in which they feed and swim.

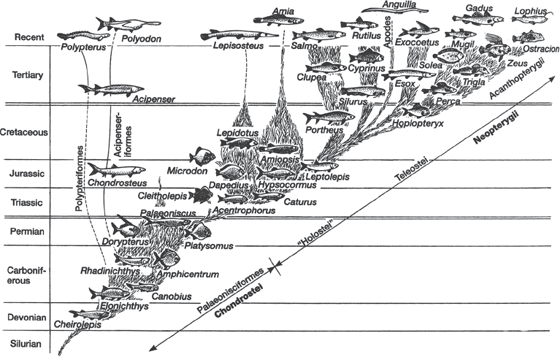

FIGURE 9.12. The evolutionary radiation of bony fishes. (From Kardong 1995; reproduced with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies)

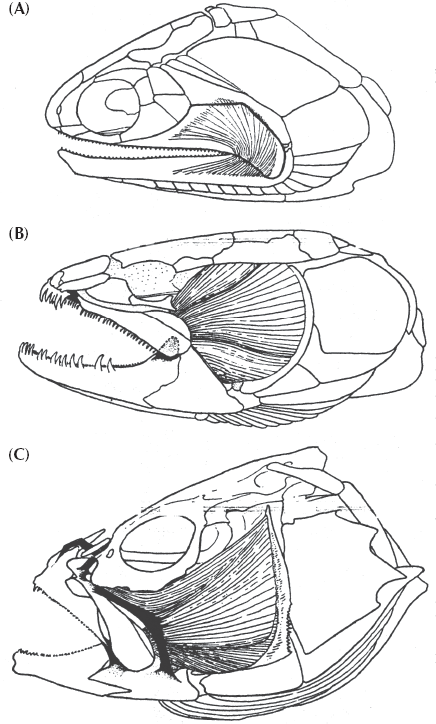

FIGURE 9.13. The transition from (A) primitive bony fish (“palaeoniscoids”) with simple robust “snap-trap” jaws and heavy bones throughout their skulls to (B) more advanced “holostean” fish (such as the bowfin Amia, shown here), with more protrusible jaws and less ossified skulls, to (C) the modern teleost fish, with a very lightly ossified skull and a protrusible jaw for sucking down prey. (From Schaeffer and Rosen 1961; used by permission)

The earliest (mostly Paleozoic) ray-finned fishes (known by the paraphyletic wastebasket name “chondrosteans”) have heavy bone surrounding the head region and simple “snap-trap” jaws with limited flexibility and limited room for muscles that close them shut. Although they have a lot of bone in their skeletons, large parts are also made of cartilage, another primitive sharklike feature. Their bodies are also covered with heavy rhombohedral scales, and their tails are very sharklike in having the upper lobe much larger than the lower lobe. By the Mesozoic, these primitive groups had mostly died out with the exception of a few living fossils, such as the sturgeon and the paddlefish. In their place came another great radiation of more advanced ray-finned fish (known by the paraphyletic wastebasket name “holosteans”), which can easily be distinguished from their primitive relatives. Their skulls are still made of fairly solid bone, but the upper jawbones (premaxillary and maxillary bones) are hinged at the front of the skull, allowing them to open their mouths wider and grab larger prey. The back part of the skull is also less solidly bony and more open, so they have enlarged jaw muscles for a stronger bite. Unlike chondrosteans, the holosteans have almost no cartilage in their skeletons but are completely bony. Their scales are thinner and smaller, so they are not as heavily armored as primitive ray-finned fish. The tail is nearly symmetrical, but the vertebral column does curve upward within the upper lobe of the tail (fig. 9.13). Most of these Mesozoic fish groups have died out, but there are a few survivors, such as the garfish and the bowfin.

The final step in fish evolution (fig. 9.12) is the great radiation of the teleost fishes, which make up 98 percent of all the fishes alive today. Nearly every fish you eat or see in the aquarium or in the lakes, rivers, or oceans is a teleost. There are about 20,000 species of teleosts, more than all the amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals combined. Teleosts branched off from the more primitive fishes during the Cretaceous and then underwent explosive evolution into hundreds of different families, most of which are still alive today. We mammal chauvinists like to think of the last 65 million years as the “age of mammals,” but in terms of diversity, the teleosts were evolving far faster than the mammals, and we could easily think of it as the “age of teleosts.”

Teleosts are easily distinguished from the more primitive chondrosteans and holosteans (fig. 9.13). Most have greatly reduced the bone in their skulls, so their heads are supported by a framework of thin bony braces and struts connected by muscles and tendons, not solid walls of bone found in the primitive forms. In particular, the bones of their mouth are much reduced and connected by flexible tendons, so they can protrude and open very easily. Many teleosts have abandoned the old snap-trap jaw mechanism of catching prey by biting with jaws and teeth. Instead they have mouths that open suddenly and create suction, slurping down their prey. (The next time you feed fish flakes to your aquarium fish, notice how they protrude their mouths and suck the food in and do not bite it). Teleosts also continue the trend of reducing bone in the rest of their skeletons as well, so that most of their bones are very light and delicate. Finally, teleosts have a completely symmetrical tail, with only a tiny trace of the upward flexure of the spine near the base.

In summary, vertebrates have come a long way from acorn worms, sea squirts, lancelets, and lampreys to the incredible array of teleosts in the waters of the world. This short chapter does not do justice to their long and incredibly rich evolutionary story. I strongly recommend that you read further on this topic if you are interested.

For Further Reading

Benton, M. J. 2014. Vertebrate Palaeontology. 4th ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. New York: Freeman.

Forey, P., and P. Janvier. 1984. Evolution of the earliest vertebrates. American Scientist 82:554–565.

Gee, H. 1997. Before the Backbone: Views on the Origin of Vertebrates. New York: Chapman & Hall.

Long, J. A. 2010. The Rise of Fishes, 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Maisey, J. G. 1996. Discovering Fossil Fishes. New York: Holt.

Moy-Thomas, J., and R. S. Miles. 1971. Palaeozoic Fishes. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Norman, J. R., and P. H. Greenwood. 1975. A History of Fishes. London: Ernest Benn.

Pough, F. H., C. M. Janis, and J. B. Heiser. 2002. Vertebrate Life. 6th ed. Upper Saddle, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Prothero, D. R. 2013. Bringing Fossils to Life: An Introduction to Paleobiology. 3rd ed. New York: Columbia University Press.

Schaeffer, B., and D. E. Rosen. 1961. Major adaptive levels in the evolution of actinopterygian feeding mechanisms. American Zoologist 1:187–204.

Shu, D.-G., H.-L. Luo, S. Conway Morris, X.-L. Zhang, S.-X. Hu, L. Chen, J. Han, M. Zhu, Y. Li, and L.-Z. Chen. 1999. Lower Cambrian vertebrates from China. Nature 402:42–46.