Now let us turn to our richest geological museums, and what a paltry display we behold! That our collections are imperfect is admitted by everyone. Many fossil species are known from single and often broken specimens. Only a small portion of the earth has been geologically explored, and no part with sufficient care. Shells and bones decay and disappear when left on the bottom of the sea where sediment is not accumulating. We err when we assume that sediment is being deposited over the whole bed of the sea sufficiently quickly to embed fossil remains. The remains which do become embedded, if in sand or gravel, will, when the beds are upraised generally be dissolved by rainwater charged with carbonic acid.

—Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

To debunk creationist distortions about fossils, we must start with a clear understanding of the fossil record and the process of fossilization. As discussed in the prologue, the fossil record was embarrassingly incomplete when Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, but it soon became one of his strongest lines of evidence. During the twentieth century, our fossil collections were vastly improved and hundreds of evolutionary sequences and transitional forms were documented.

This transformation from an embarrassing fossil record in 1860 to an embarrassment of riches by 1960 represented the hard work of thousands of dedicated paleontologists and geologists. Yet they battle against enormous odds. Creationists often assert that the fossil record is nearly complete and should show the innumerable insensibly graded transitions that Darwin expected in 1859. Yet, even with nearly 200 years of collecting behind us, the fossil record is relatively complete only in certain areas as indicated by the quote from Darwin. Fossilization is still a highly improbable event, and most creatures that have ever lived do not become fossils.

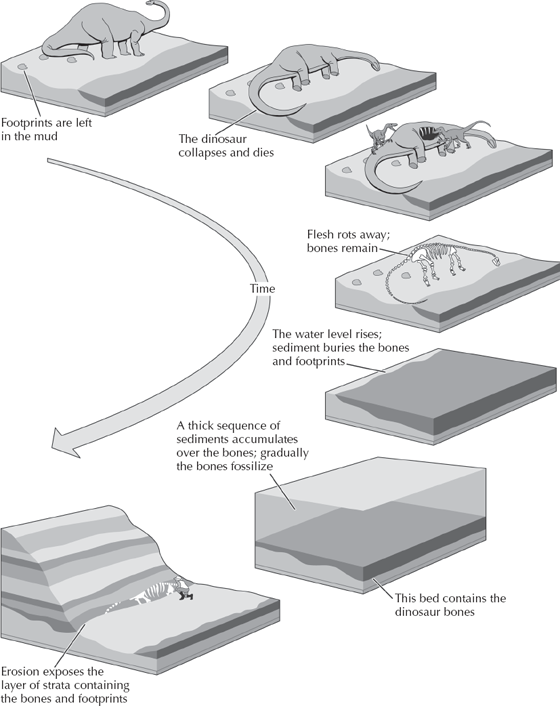

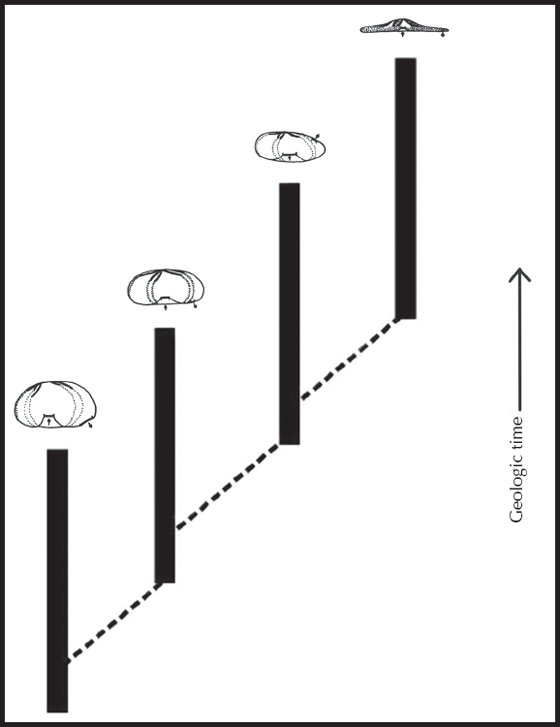

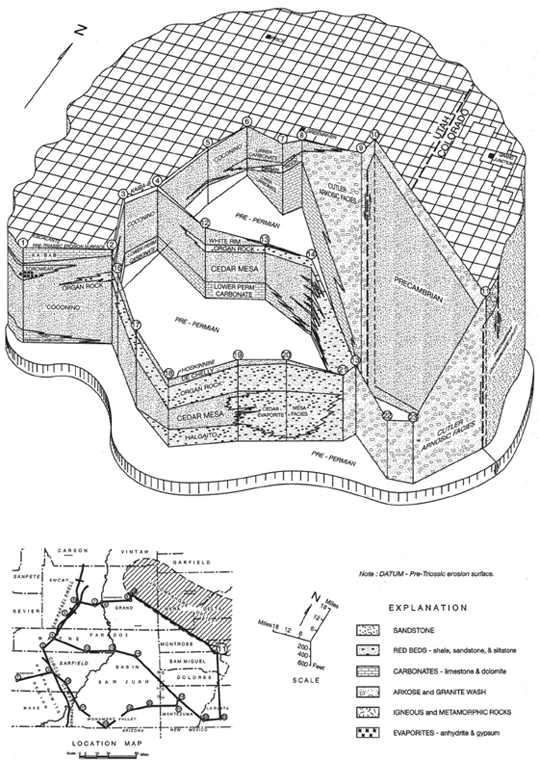

How do we know this? A whole subfield of paleontology, known as taphonomy (Greek for “laws of burial”), is dedicated to understanding how and why organisms become fossils (see Prothero 2013a: chap. 1). Consider the chain of events that happen to an organism after it dies (fig. 3.1). First, there are the biological agents (bacteria, fungi, insects, and other decomposers, scavengers, etc.) that break down or destroy an organism after death. The soft parts of animals decay or are eaten quickly, so they almost never fossilize. Only the hard parts, the shell or skeleton, have a reasonable chance of preservation. After an animal dies, its bones are typically scavenged and broken, so few or no remnants of the skeleton may actually survive. Taphonomists have done lots of research in places such as East Africa, where they have observed and documented the details of how hyenas and other scavengers tear up a carcass and break up nearly every bone. When the taphonomists mark and photograph these sites and return a year later to document the changes, even the bones that survive scavenging may have been broken or scattered by trampling or by other agents of destruction.

FIGURE 3.1. The process of fossilization destroys 99 percent of the bones and shells of most organisms, so less than 1 percent of all the species that have ever lived are preserved as fossils—and then have the great luck to have been spotted in the last 200 years when a paleontologist happens to be out collecting.

In the marine realm, there are many agents of destruction as well. Soft-bodied organisms, like sea jellies and marine worms, almost never leave a fossil record. Even organisms with hard parts, like mollusks and corals, are prone to destruction. Waves and currents wash the shells back and forth and pound them into pieces, so only the most durable shells survive. Many shells are broken by predators, such as crabs and lobsters, which use their claws or pincers to crack the shells or peel them open to get at the prey inside. Abandoned shells are degraded by organisms that use them as anchors or places to attach. A whole group of boring organisms, including sponges and algae, drill or dissolve holes in shells and reuse their minerals, thus weakening the shells even further.

Once a bone or shell survives this grueling gantlet, there are still further hazards. After burial, the shell or bone might be dissolved by water percolating through the sediments. Many fossils are actually made of new minerals that have replaced the original minerals, showing how little of the original material remains in the fossil record. As the potential fossil gets buried deeper and deeper, the huge pressure on the pile of sediments above it may distort the fossil or crush it entirely. Many deeply buried sedimentary rocks are actually transformed by high heat and pressure into metamorphic rocks, and then all original fossil traces vanish entirely.

If the shell or bone avoids or survives all these ordeals—dissolution, replacement, distortion, pressure, metamorphism—there are still more hazards ahead. Once the fossil-bearing sediment is uplifted and exposed again, the fossil is prone to erosion. If it weathers out at any time except when a paleontologist happens to wander by (which has only been happening at rare intervals in the past 200 years), then the fossil will be destroyed and lost forever. There are only a few thousand paleontologists in the entire world who can only devote at most a few weeks or months a year to collecting fossils, so most fossiliferous exposures go unexamined and their fossils are lost. If you think hard about it, the odds that any given organism will be fossilized and actually end up in our collections is minuscule. It is a miracle that we have any fossil record at all.

There are other ways to estimate the quality of our fossil record (see Prothero 2013a:22). At this moment, biologists know and have described and named about 1.5 million species on earth (mostly insects), and some estimates say that the earth harbors at least 4 or 5 million species in total. Yet there are at best only about 250,000 known species of fossil animals and plants, or about 5 percent of the species living today. But today is only one time slice among millions in the past 600 million years during which multicellular life has existed. If we total up all those time slices, then the total number of species that are represented in the fossil record is a tiny fraction of 1 percent.

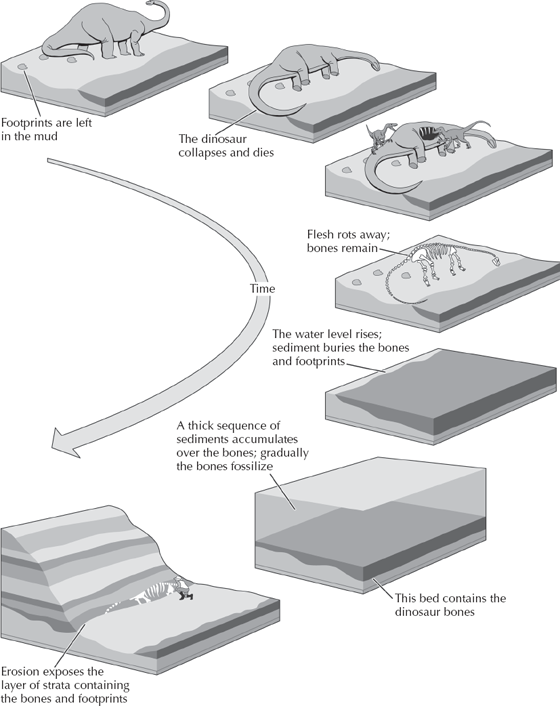

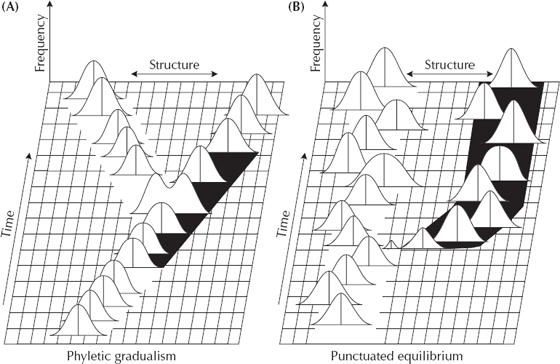

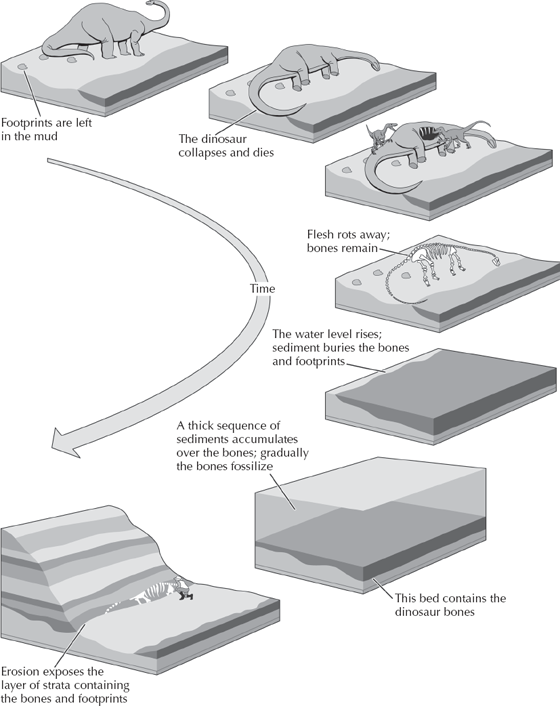

Consequently, the fossil record of some groups that are entirely soft-bodied without hard skeletons or shells (especially insects, worms, sea jellies, and the like) is so poor that most paleontologists do not study them much and do not attempt to say much about their evolution. In certain groups with hard skeletons, however, the potential for preservation is much higher. If we focus just on groups with excellent skeletons and a good chance for preservation (including microfossils, sponges, corals, mollusks, sea stars and sea urchins and their relatives, trilobites, the “lamp shells” or brachiopods, and “moss animals” or bryozoans), the fossil record is not nearly so incomplete. These groups have about 150,000 living species but more than 180,000 fossil species. Depending on how you do the calculation, between 2 and 13 percent of all the species that have ever lived in these groups may be fossilized. That’s still not great but much better than the fraction of 1 percent estimate we just discussed. In some places, the record of fossil shells is very dense and continuous (fig. 3.2), and these are places where paleontologists focus their attention in studying things like evolution. They know that not every species is preserved, of course, but they have enough data to see how evolution occurs in the groups that do fossilize.

FIGURE 3.2. In some places the fossil record is very dense and continuous, with extraordinary numbers of specimens. (A and B) The cliffs of Chesapeake Bay in Maryland are legendary for their incredibly dense shell beds. (Photos courtesy S. Kidwell) (C) The famous Pliocene Leisey shell beds in central Florida, with thousands of exquisitely preserved fossil shells. (Photo courtesy Warren D. Allmon, Paleontological Research Institution)

Most single-celled organisms, like amoebas and paramecia, are soft-bodied and never fossilize. But a few groups, such as the amoeba-like foraminiferans and radiolarians, have beautiful shells made of calcium carbonate or silica that fossilize very well (fig. 8.1). These single-celled protistans live by the millions in the oceans, and their shells are so abundant that on many parts of the seafloor the entire sediment is made of nothing but the shells of foraminiferans. The coccolithophorid algae secrete tiny button-shaped plates of calcite only a few microns in diameter. In shallow marine waters, however, coccolithophorids can live in enormous densities, and they accumulate thick piles of the limy sediment we know as chalk.

For organisms as abundant as these, the fossil record is extremely good. All the micropaleontologists need do is collect a few grams of sediment from the outcrop or from a core drilled in the deep-sea bottom and put them on microscope slides and they have thousands of specimens spanning millions of years of time. With a record as good as this, micropaleontologists can document evolution in great detail and tell how old the sediment is and show how the microfossils respond to climate change and whether the ocean waters in a given area grew deeper or shallower. Indeed, micropaleontology is the single largest subfield in paleontology because the work is indispensable to oil companies who need to know the age of the rocks that produce oil. In addition, micropaleontology is critical to marine geology in studying how climates and oceans have changed over geologic time. Without microfossils, we would have no oil and would still not understand the causes of the ice ages or earth’s past climatic changes. We will look at some of the amazing examples of evolutionary change in microfossils in chapter 8, but microfossils are the ultimate answer to the usual complaint that the fossil record is too incomplete to document evolution.

Let us now see whether the several facts and laws relating to the geological succession of organic beings accord best with the common view of the immutability of species, or with that of their slow and gradual modification through natural selection…. Yet if we compare any but the most closely related formations, all the species will have been found to have undergone some change. When a species has once disappeared from the face of the earth, we have no reason to believe that the same identical form ever reappears.

—Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

One of the common myths that creationists spread about the fossil record is that geologists shuffle the layers of strata and their sequence of fossils to prove evolution, and then the evolutionists point to the sequence as proof of evolution (Gish 1972; Morris 1974:95–96). According to creationists, this is a circular argument. But it is manifestly untrue and shows how little creationists actually know about the history of geology—and creationism.

The geologists who first discovered the fact that assemblages of fossils change through time, or faunal succession, were actually devoutly religious men who were not trying to prove evolution (an idea that would not be published for 50 to 70 years after they discovered faunal succession). One of them was William Smith, who was not an independently wealthy gentleman-scientist (like most of the early geologists and paleontologists) but a humble working man, an engineer for a local canal-digging company in the south of England. He had a keen eye for rocks and fossils and a talent for recognizing what he was digging up. Smith got one of the first good looks at a cross section of fresh rock through the normally heavily vegetated landscape of England as his canals were being dug. About 1795, he noticed that every formation excavated had a completely different assemblage of fossils, and he could tell what formation any given fossil came from because they were all distinct. He got so good at it that he would amaze the gentleman fossil collectors by telling them from exactly which stratum every fossil in their collection had been derived. He soon realized that the sequence of fossils through the rock layers of England was a powerful tool because the fossils representing each age were consistent, whereas the rock layers changed across distance. This allowed Smith to map the distinctive formations and their fossils, and by 1815 he had published the first geologic map of England, the first truly modern geologic map ever constructed (see Winchester 2002).

Because he was a common working man, Smith faced enormous difficulties getting his ideas published and recognized by the gentleman-geologists who dominated the field at that time. A few of them realized the importance of his discovery and tried to steal the credit for themselves. But after losing his impressive fossil collection and all his possessions trying to get his maps published, spending time in debtor’s prison, and having difficulties with failing health, Smith finally got credit for his crucial discovery. By 1831, shortly before his death, Smith was hailed as the “father of British geology.” Smith never attempted grand theological explanations for the change of fossils through time; he simply documented the pattern of change as an empirical fact about the rock record and a powerful tool for mapping and correlating strata all around the world.

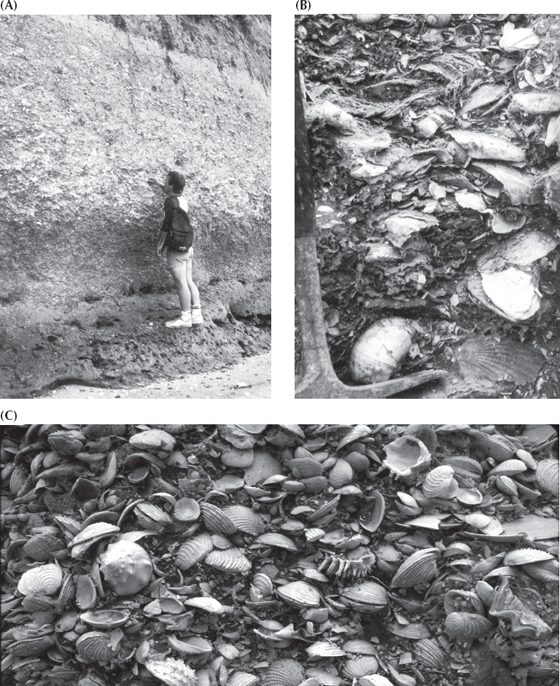

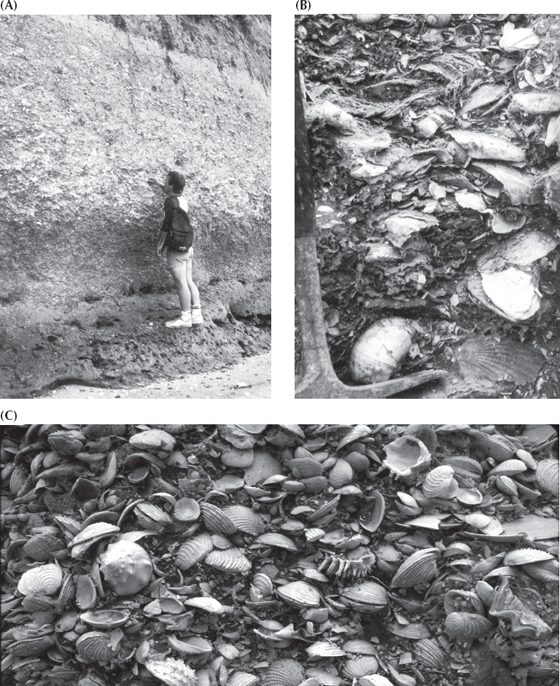

Across the English Channel, similar ideas were being developed in France. The great anatomist and paleontologist Baron Georges Cuvier was studying the fossils found around Paris and describing the distinctive rock layers beneath the city. Together with Alexandre Brongniart, who specialized in fossil mollusks, he too began to realize that each formation had a distinctively different assemblage of fossils. Some scholars point to this apparently independent discovery of faunal succession as a classic example of how, when the time is ripe for a new idea, it will emerge in several places at once. Others suggest that Brongniart may have heard about it when he made a trip to England in 1802 (one of the few times that France and England were not hostile during the period from the French Revolution through the battles with Napoleon that did not end until 1815). Either way, faunal succession was a powerful tool that was adopted by geologists all over Europe and eventually the world, so that by 1850, they had worked out the succession of rocks and fossils in many places, and named the periods of the geologic time scale (fig. 3.3). Evolution was still a radical notion floating around among French and British biologists (but not geologists), and it was still a decade before Darwin would publish his ideas.

FIGURE 3.3. The geologic time scale was originally reconstructed by devout creationist geologists who realized that the record of fossils was too complex to be explained by a single Genesis flood. This version of the time scale was published by Richard Owen (1861), one of the last legitimate creationist biologists.

Indeed, Cuvier himself was staunchly against the evolutionary ideas of his colleague Lamarck and tried to use the fossil record against him. Cuvier pointed to mummified animals recovered from the Egyptian tombs (recently robbed by Napoleon’s soldiers). These mummified cats and ibises had not changed since the time of the ancient Egyptians. To Cuvier, this was proof that life was not constantly changing and evolving, as Lamarck had suggested. As the most prominent man in French science, Cuvier also had to avoid the speculative approaches of Geoffroy and Lamarck. Instead, he proposed his own solution to the dilemma. The layers of rock with fossils of extinct animals represented a dark, dangerous period before the Creation and flood of Genesis (the antediluvian period, Latin for “before the flood”) not described in the Bible. God had created and destroyed these earlier antediluvian worlds before the Genesis record begins. This solution was not too heretical for the time; it allowed Cuvier to recognize that the rock record was full of fossils of extinct organisms that could not have made it to Noah’s ark and that were certainly not alive in his day.

Other geologists and paleontologists followed Cuvier’s lead and tried to describe each layer with its distinctive fossils as evidence of yet another Creation and flood event not mentioned in the Bible. In 1842, Alcide d’Orbigny began describing the Jurassic fossils from the southwestern French Alps and soon recognized ten different stages, each of which he interpreted as a separate nonbiblical creation and flood. As the work continued, it became more and more complicated until 27 separate creations and floods were recognized, which distorted the biblical account out of shape. By this time, European geologists finally began to admit that the sequence of fossils was too long and complex to fit with Genesis at all. They abandoned the attempt to reconcile the fossil sequence with the Bible. Remember, these were devout men who did not doubt the Bible and were certainly not interested in shuffling the sequence of fossils to prove Darwinian evolution (an idea still not published at this point). They simply did not see how the Bible could explain the rock record as it was then understood.

Instead of worrying about theology, geologists and paleontologists realized that faunal succession was an extremely powerful tool that allowed them to date and correlate rocks all over the world. The principle of faunal succession grew into the discipline of biostratigraphy, where the distribution of fossils in the different strata helps us determine their age (see Prothero 2013a: chap. 10). Biostratigraphy, in turn, helps us map the distribution of rocks on earth. It is the principal tool used by oil and coal geologists to date and correlate the rocks they are drilling and exploring for valuable resources. Without biostratigraphy, we would have no oil or gas, and our modern industrial age, dependent as it is on cheap petroleum, would never have occurred.

As we saw with Smith and Cuvier, biostratigraphy does not require evolution or any other theoretical explanation for why the fossils change through time. It simply deals with the empirical fact that they do change. Biostratigraphic theory considers how to decipher these patterns of fossil distribution and get the most reliable results and has little or no biological component at all. Indeed, many fossils that are valuable biostratigraphic time indicators are actually treated as unusual objects of curious shapes, not like remains of extinct organisms. If they were nonbiological objects such as nuts, bolts, and screws and changed predictably through time, they would work just as well. The proof of this is that many of the best fossils for biostratigraphy are poorly understood biologically (this includes most microfossil groups) and the biological relationships of some important extinct organisms (such as graptolites, conodonts, and acritarchs) were completely unknown for more than a century. That didn’t stop them from being useful for biostratigraphy.

Of course, once the idea of evolution came along, it explained why fossils change through time. But to recapitulate my main point, the succession of fossils through time was established by devoutly Christian geologists decades before Darwin published his ideas about evolution. There is no possibility of the alleged fraud of arranging fossils to prove evolution, as creationists claim.

If the system of “flood geology” can be established on a sound scientific basis, and be effectively promoted and publicized, then the entire evolutionary cosmology, at least in its present neo-Darwinian form, will collapse. This, in turn, would mean that every anti-Christian system and movement (communism, racism, humanism, libertinism, behaviorism, and all the rest) would be deprived of their pseudo-intellectual foundation.

—Henry Morris, Scientific Creationism

Creationists like to dismiss evolution as only a theory. My favorite rejoinder is that creationism isn’t even a theory. When examined in the light of well-known and thoroughly researched scientific phenomena, creationist “flood geology” fails the most basic and simple test known to forensic science: bodies don’t pile up the way creationists insist they must.

—Walter F. Rowe, “Bobbing for Dinosaurs: A Forensic Scientist Looks at the Genesis Flood”

If the creationists cannot claim that the fossil record has been fraudulently shuffled by geologists to prove evolution, then they must acknowledge that it shows changing fossil faunas through time, not instantaneous creation. As we saw with the early fundamentalists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (chapter 2), most had come to terms with the idea that the change in fossil faunas through time did support the idea of evolution, even if they were unhappy with that notion. But we must never underestimate the wild imaginations of religious fanatics who will bend the truth in whatever way they need to win their battles. If the fossil record does show a sequence of faunas through time, then they believe that there must be a biblical explanation for it.

The first detailed attempt at such an explanation came from a Seventh-Day Adventist schoolteacher named George Macready Price, who published a series of books starting in 1902. Price had no formal training or experience in geology or paleontology and in fact attended only a few college classes at a tiny Adventist college. But inspired by Ellen G. White, the prophetess and founder of the Seventh-Day Adventist movement, he dreamed up an explanation called flood geology and aggressively promoted it for more than 60 years until his death in 1963. According to Price, the flood accounted for all of the fossil record, with the helpless invertebrates being buried first, and the larger land animals floating to the top to be buried in higher strata, or fleeing the floodwaters to higher ground. Price also originated the lie we just debunked about geologists dating rocks by their fossil content while simultaneously determining the age of fossils by their position in the geologic column. Ignorant of history or geology, Price was unaware of the fact that religious geologists had believed in a Noachian deluge explanation of the fossil record in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries but abandoned it when their own work showed it to be impossible—long before evolution came on the scene. The most famous geologic treatise of the seventeenth century, The Sacred Theory of the Earth, by Reverend Thomas Burnet, dealt with the problem of the Noachian deluge explaining the rock record. Burnet, unlike the modern creationists, did not fall back on the supernatural. Although others urged him to resort to miracles, Burnet declared, “They say in short that God Almighty created waters on purpose to make the Deluge…. And this, in a few words, in the whole account of the business. This is to cut the knot when we cannot loose it.”

In Price’s later years, his bizarre ideas about geology were generally ignored as embarrassments by most creationists (see Numbers 1992:89–101). Most subscribed to the “day-age” idea of Genesis, where the “days” of scripture were geologic “ages,” and did not try to contort all the evidence of geology into a simplistic flood model. Some disciples of Price actually tried to test his ideas and look at the rocks for themselves, which Price apparently never bothered to do. In 1938, Price’s follower Harold W. Clark “at the invitation of one of his students visited the oil fields of Oklahoma and northern Texas and saw with his own eye why geologists believed as they did. Observations of deep drilling and conversations with practical geologists [none of whom were trying to prove evolution, but simply using biostratigraphy to find oil] gave him a ‘real shock’ that permanently erased any confidence in Price’s vision of a topsy-turvy fossil record” (Numbers 1992:125). Clark wrote to Price,

The rocks do lie in a much more definite sequence than we have ever allowed. The statements made in the New Geology [Price’s term for flood geology] do not harmonize with the conditions in the field…. All over the Middle West the rocks lie in great sheets extending over hundreds of miles, in regular order. Thousands of well cores prove this. In East Texas alone are 25,000 deep wells. Probably well over 100,000 wells in the Midwest give data that have been studied and correlated. The science has become a very exact one, and millions of dollars are spent in drilling, with the paleontological findings of the company geologists taken as the basis for the work. The sequence of microscopic fossils in the strata is very remarkably uniform…. The same sequence is found in America, Europe, and anywhere that detailed studies have been made. This oil geology has opened up the depths of the earth in a way that we never dreamed of twenty years ago. (quoted in Numbers 1992:125)

Clark’s statement is a classic example of a reality check shattering the fantasy world of the flood geologists. Unfortunately, most creationists do not seek scientific reality. They prefer to speculate from their armchairs and read simplified popular books about fossils and rocks rather than go out in the field and do the research themselves or do the hard work of getting the necessary advanced training in geology and paleontology.

In the 1950s, the young seminarian John C. Whitcomb tried to revive Price’s ideas yet again. When Douglas Block, a devout and sympathetic friend with geologic training, reviewed Whitcomb’s manuscript, he “found Price’s recycled arguments almost more than he could stomach. ‘It would seem,’ wrote the upset geologist, ‘that somewhere along the line there would have been a genuinely well-trained geologist who would have seen the implications of flood geology, and, if tenable, would have worked them into a reasonable system that was positive rather than negative in character.’ He assured Whitcomb that he and his colleagues at Wheaton [College, an evangelical school] were not ignoring Price. In fact, they required every geology student to read at least one of his books, and they repeatedly tested his ideas in seminars and in the field. By the time Block finished Whitcomb’s manuscript, he had grown so agitated he offered to drive down to instruct Whitcomb on the basics of historical geology” (Numbers 1992:190).

In 1961, Whitcomb and hydraulic engineer Henry Morris published The Genesis Flood, where they rehashed Price’s notions with a twist or two of their own. Their main contribution was the idea of hydraulic sorting by Noah’s flood, where the flood would bury the heavier shells of marine invertebrates and fishes in the lower levels, followed by more advanced animals such as amphibians, reptiles (including dinosaurs) fleeing to intermediate levels, and finally the “smart mammals” would climb to the highest levels to escape the rising floodwaters before they were buried.

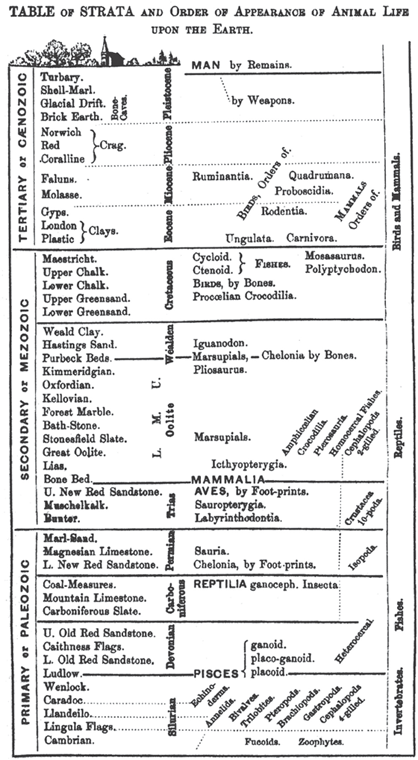

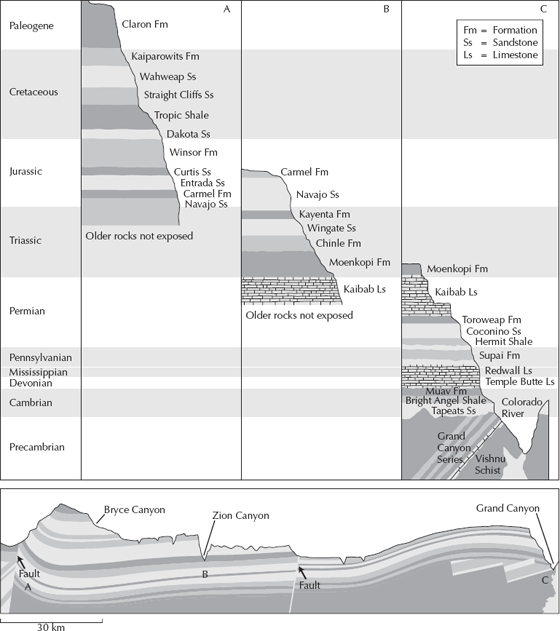

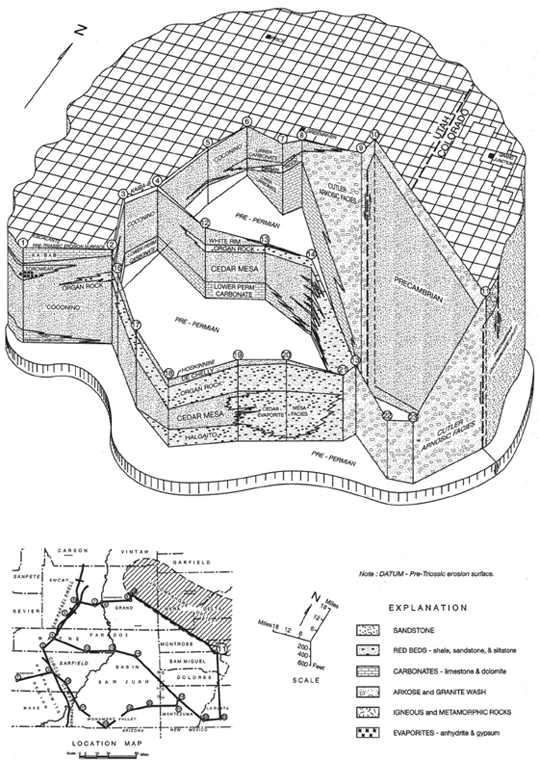

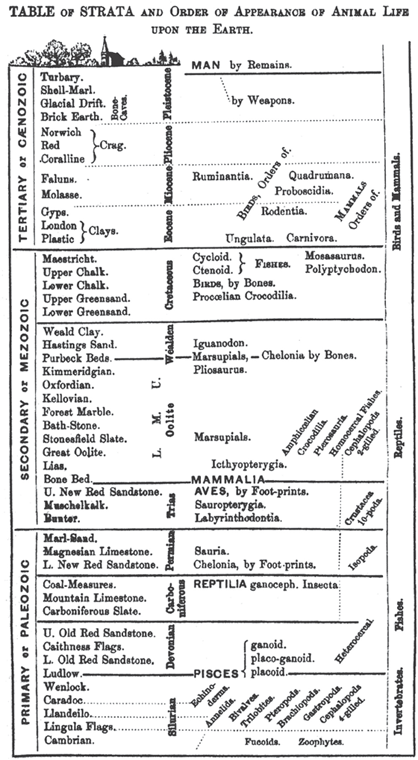

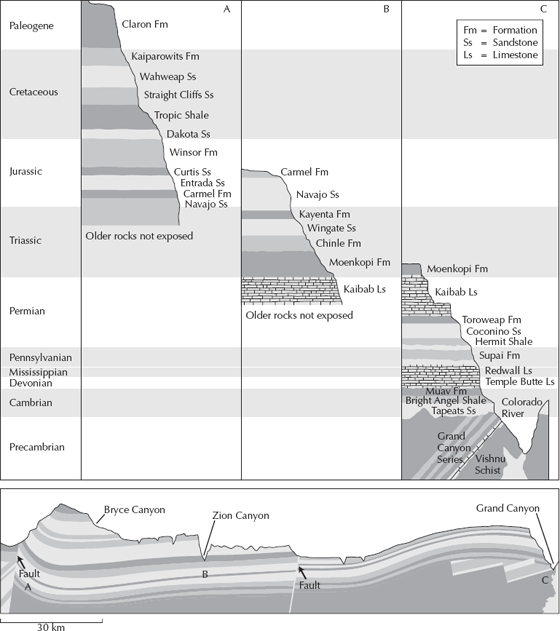

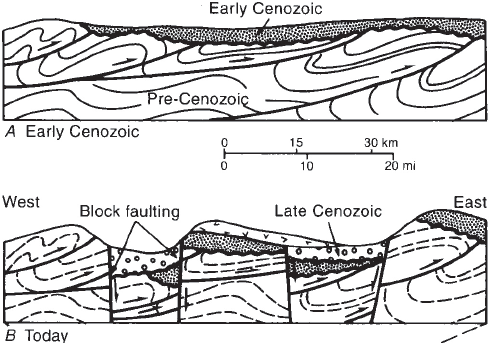

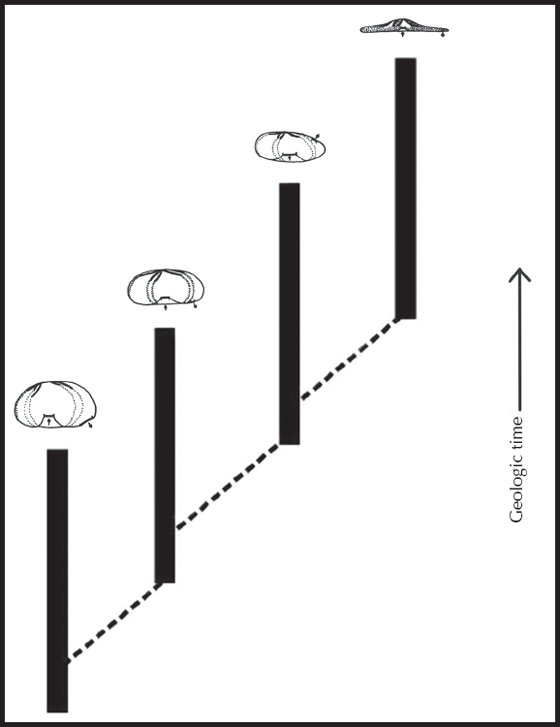

The first time a professional geologist or paleontologist reads this weird scenario, they cannot help but be amazed at its naiveté. Price, Whitcomb, and Morris apparently never spent any time collecting fossils or rocks. What their model is trying to explain is a cartoon, an oversimplication drawn for kiddie books—not any real stratigraphic sequence of fossils documented in science. Those simplistic diagrams with the invertebrates at the bottom, the dinosaurs in the middle, and the mammals on top bear no resemblance to any local sequence on earth. In fact, those oversimplified cartoons show only the first appearance of invertebrates, dinosaurs, and mammals, not their order of fossilization in the rock record (since invertebrates are obviously still with us and are found in all strata from the bottom to the top; see page 1). This diagram is an abstraction based on the complex three-dimensional pattern of rocks from all over the world. In a few extraordinary places, such as William Smith’s England, or the Grand Canyon, Zion, and Bryce National Parks in Utah and Arizona, we have a fairly continuous sequence of a long stretch of geologic time (fig. 3.4), so we know the true order in which rocks and fossils stack one on top of another. But even in that sequence, we have “dumb” marine ammonites, clams, and snails from the Cretaceous Mancos Shale found on top of “smarter, faster” amphibians and reptiles (including dinosaurs) from the Triassic and Jurassic Moenkopi, Chinle, Kayenta, and Navajo Formations.

FIGURE 3.4. The sequence of rocks in the “Grand Staircase” and Grand Canyon country of Utah and Arizona shows that the superpositional order of formations and geologic time periods is no geologic fantasy but is instead based on empirical evidence.

Just to the north, in the Utah-Wyoming border region, the middle Eocene Green River Shale yields famous fish fossils quarried by commercial collectors for almost a century. The Green River Shale produces fossils of not only freshwater fish but also freshwater clams and snails, frogs, crocodiles, birds, and land plants. The rocks are finely laminated shale diagnostic of deposition in quiet water over thousands of years, with fossil mudcracks and salts formed by complete evaporation of the water. These fossils and sediments are all characteristic of a lake deposit that occasionally dried up, not a giant flood. These Green River fish fossils lie above the famous dinosaur-bearing beds of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation in places such as Dinosaur National Monument and above many of the mammal-bearing beds of the lower Eocene Wasatch Formation as well, so once again the fish and invertebrates are found above the supposedly smarter and faster dinosaurs and mammals.

If you think hard about it, why should we expect that marine invertebrates or fish would drown at all? They are, after all, adapted to marine waters, and many are highly mobile when the sediment is shifting. As Stephen Jay Gould put it,

Surely, somewhere, at least one courageous trilobite would have paddled on valiantly (as its colleagues succumbed) and won a place in the upper strata. Surely, on some primordial beach, a man would have suffered a heart attack and been washed into the lower strata before intelligence had a chance to plot a temporary escape…. No trilobite lies in the upper strata because they all perished 225 million years ago. No man keeps lithified company with a dinosaur, because we were still 60 million years in the future when the last dinosaur perished. (Gould 1984:132)

In addition to the examples just given, there are hundreds of other places in the world where the “dumb invertebrates” that supposedly drowned in the initial stages of the rising flood are found on top of “smarter, faster land animals,” including many places in the Atlantic Coast of the United States, Europe, and Asia, where marine shell beds overlie those bearing land mammals. In some places, like the Calvert Cliffs of Chesapeake Bay in Maryland (fig. 3.2A) or Sharktooth Hill near Bakersfield, California, the land mammal fossils and the marine shells are all mixed together, and there are also beds with marine shells above and below those containing land mammals! How could that make any sense with the “rising floodwaters” of the creationist model?

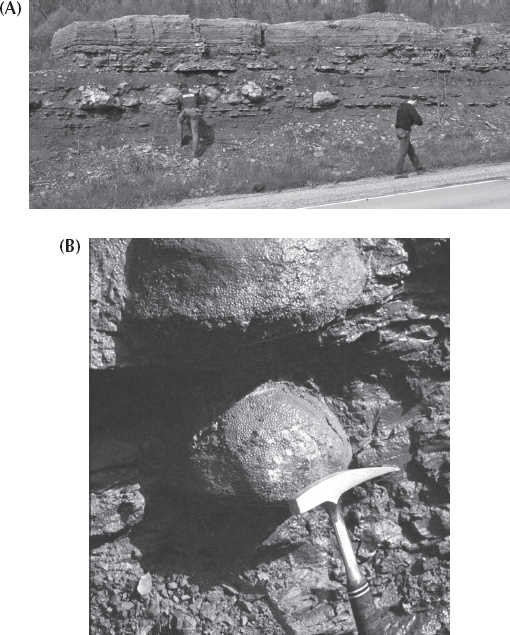

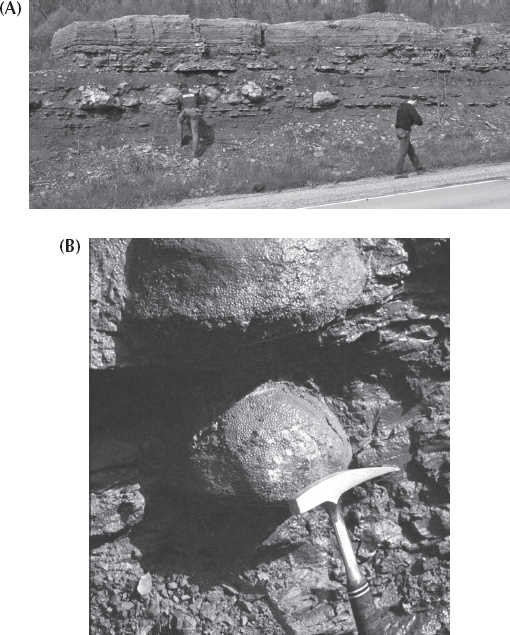

In a supreme twist of irony, the disproof of flood geology is found just beneath the Answers in Genesis creation “museum” in Kentucky. The museum is built upon the famous Ordovician rocks of the Cincinnati Arch, which span millions of years of the later Ordovician. If you poke around the slopes all around the area (as I often have), you will find hundreds of finely laminated layers of shales and limestones, each full of delicate fossils of trilobites and bryozoans and brachiopods preserved in life positions that could never have been disturbed by floodwaters—and each layer of hundreds represents another community of marine organisms that grew and lived and then was gently buried in fine silts and clays (fig. 3.5). There is no possibility these hundreds of individual layers of delicately preserved fossils were deposited in a single “Noah’s flood.” Over a century ago, paleontologists documented that these fossil communities change and evolve through time, so they can tell exactly what part of the Ordovician each layer came from by its characteristic fossils. You could not ask for a better refutation of flood geology—yet the Answers in Genesis ministry that built the museum is so ignorant of geology and paleontology that they never noticed that the foundation of their own showcase building falsifies their ideas.

FIGURE 3.5. The rocks of the Cincinnati Arch just beneath the “Creation Museum” debunk flood geology all by themselves. In many cases, you can find layer after layer of marine fossils in life position, undisturbed and buried by fine layers of mud, before another layer of organisms grew on the next layer, and so on. In these shots from road cuts in northern Kentucky just a few miles from the museum, you can see huge fossil coral heads in life position, each lying on a different layer of shallow seafloor mudstones. Each individual coral shows many years of growth bands, proving that it was not brought there by a flood but grew for many years on this shallow seafloor before it was finally buried. And there are many such examples, one layer after another. (A) Broad overview of one road cut, showing coral heads growing in place in multiple levels. (B) Close up of two large coral heads, showing their exposed growth bands, and also the fact that each grew on a different layer at a different time, so they were not dumped there by a single flood event. (Photos by the author)

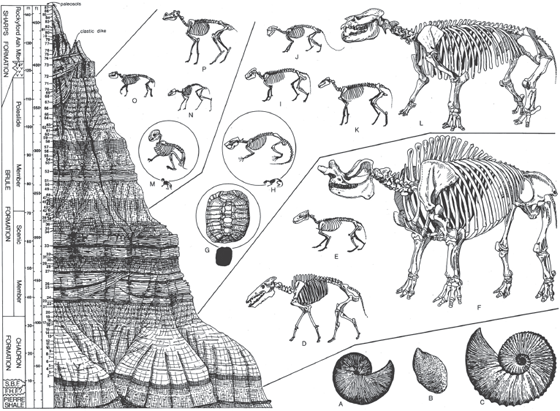

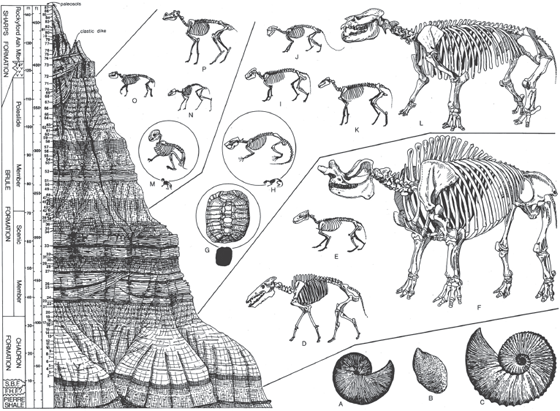

We could go on and on about the endless list of absurdities of flood geology (for a point-by-point demolition of Whitcomb and Morris’s fantasy world, see McGowan 1984:58–67), but I will sum it up with one more example. I did some of my graduate dissertation work in the Big Badlands of South Dakota, one of the richest vertebrate-bearing fossil deposits in the world (fig. 3.6). The sequence of fossils there is very well known, and we can now establish the precise ranges of organisms through several hundred feet of sandstones and mudstones. Indeed, establishing the biostratigraphic sequence of the mammal fossils was a major part of the research I did in my doctoral dissertation. At the base of the sequence are marine fossils, but right above them are the late Eocene fossils of the Chadron Formation, which include many large and spectacular mammals, including the huge rhino-like brontotheres. Above these in the overlying Brule Formation is a different assemblage of fossil mammals, none of which look like they could have outrun the huge brontotheres. Many of these are rodents. It’s hard to imagine them doing a better job at “scrambling for higher ground” than the bigger, longer-legged animals. The clincher, however, is the fact that the most abundant fossils in the Brule Formation are tortoises! We have a new version of Aesop’s fable of the tortoise and the hare, although here the dumb tortoises not only beat the hares to higher ground but also nearly all the rest of the smarter, larger, longer-legged mammals as well. If there ever was a clear-cut falsification of the flood geology model, this alone should be enough!

FIGURE 3.6. The sequence of fossils in the White River Group in Badlands National Park shows that even slow turtles are fossilized above supposedly smarter, faster mammals, so the “flood geology” model makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. The fossils are as follows: A–C: mollusks from the Cretaceous interior seaway: (A) the ammonite Hoploscaphites nicolleti; (B) the clam Tenuipteria fibrosa; (C) the ammonite Discoscaphites cheyennensis; D–F: mammals from the upper Eocene Chadron Formation; (D) the piglike entelodont Archaeotherium mortoni; (E) the predatory creodont Hyaenodon horridus; (F) the giant titanothere Megacerops; G–L: fossil vertebrates from the early Oligocene Scenic Member of the Bruel Formation; (G) the tortoise Stylemys nebrascensis; (H) the squirrel-like rodent Ischyromys typus; (I) the larger oreodont Merycoidodon culbertsoni; (J) the “false sabertooth” Hoplophoneus primaevus; (K) the three-toed horse Mesohippus bairdi; (L) the hippo-like rhinoceros Metamynodon planifrons; M–P, middle Oligocene fossil mammals from the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation; (M) the rabbit Palaeolagus haydeni; (N) the tiny deerlike Leptomeryx evansi; (O) the oreodont Leptauchenia decora; (P) the horned Protoceras celer. (Drawing by G. J. Retallack; reprinted with permission of the author and the Geological Society of America)

In addition to this stratigraphic fantasy world, Price and later flood geologists were particularly obsessed with overthrusts, places on earth where older rocks are shoved on top of younger ones along a fault plane. Price claimed that these overthrust faults were imaginary. Because they put the fossils in the wrong order, evolutionists had to explain away this anomaly by claiming that older rocks were thrust on top of younger rocks. Many creationists have repeated this claim (often verbatim from Price). For example, Whitcomb and Morris (1961:187) lifted the following partial quote from Ross and Rezak (1959) on the Lewis thrust in Glacier National Park:

Most visitors, especially those who stay on the roads, get the impression that the Belt [the oldest rocks, of Precambrian age] are undisturbed and lie almost as flat today as they did when deposited in the sea which vanished so many million years ago.

Whitcomb and Morris fail to give the rest of the citation, which reads,

Actually, they are folded, and in certain places, they are intensely so. From points on and near the trails in the park, it is possible to observe places where the Belt series, as revealed in the outcrops on ridges, cliffs, and canyon walls, are folded and crumpled almost as intricately as the soft younger strata in the mountains south of the park and in the Great Plains adjoining the park to the east.

So much for the supposed evidence that the fossils were deposited out of order! If the creationists were at all interested in real geology, they would spend the time and effort to see the rocks for themselves and realize that there is good independent evidence for the overthrusting. At the very least, they should not resort to deceptive quoting out of context, when the complete quotation clearly denies their claim.

In summary, the flood geology model constructed by Price and modified by Whitcomb and Morris bears no relation to any actual sequence of rocks or fossils on earth but was dreamed up to explain oversimplified cartoons. If these authors had any real experience with rocks or fossils, they would never have considered the model remotely reasonable. Indeed, religious geologists who have done their homework on fossils (as in the quotations from Clark and Block above) admit that the flood geology model does nothing to explain the real fossil record. Any consideration of a real sequence of fossils and rocks (such as the Big Badlands or the Grand Canyon) immediately demolishes the notion that a single Noachian deluge can account for the rock record and the actual sequence of fossils contained in those rocks.

The main reason for insisting on the universal Flood as a fact of history and as the primary vehicle for geological interpretation is that God’s Word plainly teaches it! No geological difficulties, real or imagined, can be allowed to take precedence over the clear statements and necessary inferences of Scripture.

—Henry Morris, Biblical Cosmology and Modern Science

In Alice’s Adventures Through the Looking-Glass, Alice steps through a mirror into a world in which all the rules are backward or reversed, and everything is the opposite of reality. A practicing geologist gets the same sensation when he or she reads about flood geology: the photographs of rocks are the same, and some of the same words are used, but the thinking is entirely alien to this planet. Nowhere is this more apparent than the creationist attempts to explain the geology of the Grand Canyon as a product of a single Noah’s flood.

The reasons for the creationists’ laser-like focus on the Grand Canyon (and almost no other geologic feature or national park) are obvious. People all over the world have seen pictures of and often visit this legendary place for its spectacular scenery; they cannot help but be impressed by the evidence it presents for millions of years of geologic history. The creationists are trying to show their followers that they can explain all of geology with the Noah’s flood myth, so naturally they spend their energies on the most spectacular national park that best shows that earth has a long history. They’ve even managed to get one of their books (edited by a river guide who had a religious conversion experience, not a real geologist) offered for sale at the visitors’ centers on the rim of the Grand Canyon. This has remained true for years now, despite the fact that the rangers and geologists at Grand Canyon National Park have repeatedly protested the sale of the book. The fact that this tract pushing the view of a specific religious minority is sold by a federal facility seems to be a violation of the separation of church and state and is probably unconstitutional.

Creationist flood geologists have made up their minds that the ancient flood myths of a sheep-herding culture must be literal truth. Then they bend and twist and special plead the entire history of the Grand Canyon into their preconceived notions that somehow this immense and magnificent pile of rocks must have been produced by one supernatural flood. If flood geologists were real scientists, they would look at real flood deposits and ask what they should look like. Because they never bother to do this, let’s do it for them.

Geologists who study sedimentary rocks (known as sedimentologists) have become very sophisticated forensic detectives, looking at the clues found in sandstone or limestone and discovering amazing evidence of the source of the sediments, how the sediments were transported, what environment they were formed in, how they were deposited, and then how they were turned into rock. Sedimentology is also the principal skill required to find nearly all the oil, natural gas, coal, groundwater, uranium, and many other economically important natural resources, so we ignore their expertise at our own peril (for a basic background in the subject, see Prothero and Schwab 2013). These same sedimentologists who have found all the oil and coal and groundwater we require also have studied actual flood deposits and know exactly what they should look like. If the Noah’s flood story were actually true, we would expect to find that the geology around the world (not just in the Grand Canyon) would begin with coarse-grained poorly sorted deposits of sand and gravel and boulders from the fast-water stage of a flood. Once a flood recedes, it can leave only one kind of deposit: a single layer of mud. Most floods inundate an area, and then the mud slowly settles out of suspension from the standing floodwaters until it accumulates in a thin layer. Even a worldwide flood would produce only one relatively thin layer of mudstone (not shale, because that requires burial and compaction over millions of years).

How does this compare to the real Grand Canyon? It’s not even remotely close! Even a cursory glance at the sequence of layers in the Grand Canyon (fig. 3.4) shows that it is highly complex and cannot be explained by a single superflood (or even many floods, if that were an option). For one thing, there is no great deposit of coarse gravel and boulders and sand near the base representing the high-energy phase of rapidly moving water. For another, the upper part of the Grand Canyon sequence is not just a single thin layer of mud. Instead, it is a complex sequence of shales (not mudstones), sandstones, and limestones that alternate in a sequence that resembles no known flood deposits.

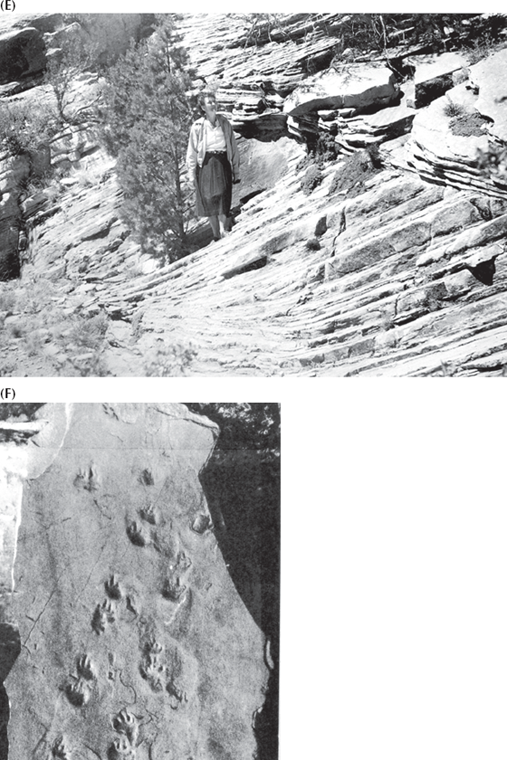

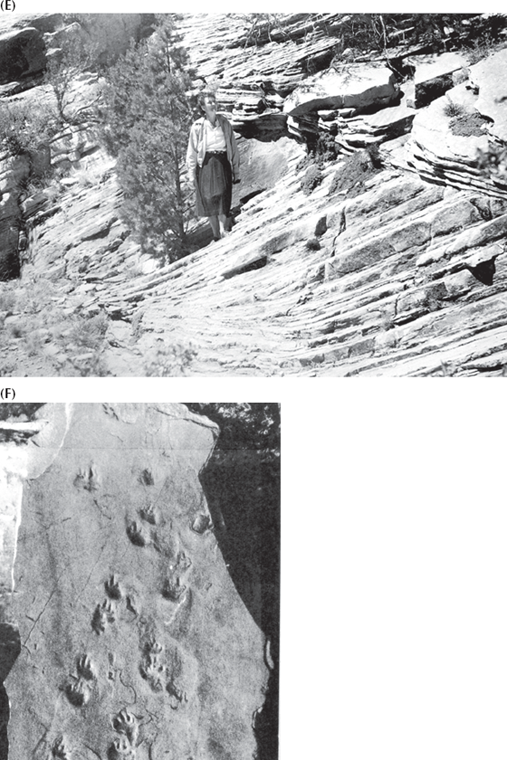

Let’s start at the very bottom of the Canyon. Instead of coarse gravel, sand, and boulder deposits that flood geologists might expect, we have the ancient rocks of the Grand Canyon Series (fig. 3.7A and B). These are mostly quiet-water shales, plus sandstones and even some limestones. Many of these limestones contain stromatolites (figs. 3.7B, 6.1, and 7.1), dome-like mounds of layered sediment formed by algal mats that can only grow in the quiet waters of a sunny coastal lagoon. The individual layers in these stromatolites testify to hundreds of years of growth on each one—and there are multiple layers of stromatolites, each representing a separate episode of slow growth followed by burial, and then another phase of growth on a new surface. And this was supposedly formed during a single huge flood event only 40 days in duration?

FIGURE 3.7. Close examination of the actual rocks in the Grand Canyon makes the “flood geology” hypothesis completely absurd. (A) Large mudcracks in the Precambrian Grand Canyon Series, in the lowest tilted sequence in the Grand Canyon. There are layer after layer of cracks like these in these shales, showing that there were hundreds of individual drying events—not possible with a single flood. (Photo by the author) (B) In other places, there are layered algal mats known as stromatolites, which were formed by daily fluctuations of sediment and algal growth. Some actually record decades or centuries of growth. These are abundant in the tilted late Precambrian limestones beneath the Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon. (Photo courtesy U.S. Geological Survey) (C) The lower Cambrian (left) Tapeats Sandstone and (right) Bright Angel Shale are full of layer after layer of sediments with complex burrows and trackways, showing that each layer had been part of another sea bottom that was crawled upon and burrowed into and then buried again and again. (Photo courtesy L. Middleton) (D) The Pennsylvanian-Permian Supai Group and Hermit Shale are also full of layer upon layer of mudcracks, showing that they went through hundreds of episodes of drying, completely falsifying the flood geology model. (Photo courtesy U.S. Geological Survey) (E) The Permian Coconino Sandstone is composed entirely of huge cross-beds that could only have formed in desert sand dunes, not underwater. (Photo courtesy U.S. Geological Survey) (F) The Coconino dune faces also are covered with the trackways of reptiles that could never have been formed underwater. (Photo courtesy U.S. Geological Survey)

A clear refutation of the flood geology model is the abundant mudcracks (fig. 3.7A) found in many of the shale units of the Grand Canyon Series. We’ve all seen mud dry up and form cracks. Common sense should tell even the creationists that the entire muddy surface was deposited and then dried up, not formed during the inundation of a flood. There’s not just one layer of mudcracks, but hundreds, sometimes stacked in a long sequence. Clearly, these rocks represent dozens of small episodes of mud deposition and then complete drying, not a single catastrophic flood. A few creationist books and websites try to squirm out of this by mentioning unusual features such as syneresis cracks. What they don’t mention is that even syneresis cracks still require drying and evaporation and shrinkage, so they are completely inconsistent with the flood geology model.

Even more strongly falsifying the flood geology model is that in the middle of this Grand Canyon Series sedimentary sequence are the Cardenas lava flows, dozens of individual flows totaling almost 1,000 feet in thickness. If these rocks had erupted into the floodwaters, they would be entirely composed of blobs of lava known as pillow lavas, which we can see erupting from undersea lava flows today. Instead, the Cardenas lavas show clear signs that they are normal subaerial eruptions and flowed downhill from their nearest volcano, much like the lavas erupting from Mount Kilauea in Hawaii. The very top of the lava flows shows evidence that they had completely cooled and were even weathered and eroded by wind and rain before the next sequence of sedimentary rocks was deposited on top of them. This is hardly consistent with the idea of lavas that erupted underwater during a major flood!

Finally, the clincher is that all these ancient Grand Canyon Series rocks at the base of the Grand Canyon are now found tilted on their sides and eroded on the edges, and then the rest of the Grand Canyon strata are deposited on top of them (fig. 3.4). A flood geologist simply cannot explain this. If these rocks were all soft soupy sediments deposited by Noah’s flood, then as soon as some supernatural force rapidly tilted them on their sides, they would have all slumped downhill and left big gravity slump folds, a feature well known to sedimentologists. Instead, the entire sequence is undisturbed and full of stromatolites, mudcracks, and lava flows that belie the entire flood geology model right then and there. We have evidence of deposition of the Grand Canyon Series sediments (along with long erosion between them, when the Galeros lavas flowed across the landscape), then the hardening of these soft sediments into sedimentary rock layers, then tilting, then erosion, then another long sequence that makes up the higher part of the Grand Canyon. All of this is supposedly formed in a single large flood event?

And so it goes, layer by layer, right up through the rest of the Grand Canyon. The first unit above the tilted Grand Canyon Series rocks is the Tapeats Sandstone (figs. 3.4 and 3.7C), a classic beach and nearshore deposit. It is chock-full of trackways and burrows of trilobites, worms, and other invertebrates, layer after layer. When would these animals have had any time to crawl across the bottom and leave tracks or burrow through the sediment if it had been rapidly dumped by a flood? Above the Tapeats is the Bright Angel Shale, which real geologists interpret as deposited on a shallow marine shelf below the action of storm waves. It too is full of tracks and burrows, but of the types that today occur in the deeper part of the ocean. How did these tracks and burrows get there, layer after layer, if all the deposits of the Grand Canyon are a single flood deposit that drowned and buried all the marine life before it had a chance to begin burrowing?

The Bright Angel Shale has a complex interfingering relationship with the next unit above, the Muav Limestone. These types of relationships, where a thin layer of limestone alternates with a thin layer of shale, are very typical of deposits we find today when sea level slowly fluctuates back and forth—but it is impossible to explain such a complex relationship by a single flood dumping these sediments in a flat “layer cake.” The Muav Limestone is one of three consecutive limestones forming the steepest cliffs in the Grand Canyon. Above the Muav is a sharp erosional surface with deeply eroded collapse features (from ancient collapsed caves that slowly dissolved out of the Muav), into which the much younger Temple Butte Limestone is deposited. The Temple Butte was then eroded away in most places (except the remnant fillings of those collapse features), and above it is deposited the big cliff of the Redwall Limestone. All three limestones have the features typical of modern limestones, made largely of the delicate remains of fossils. Today, we find such sediments forming in tropical, clear-water lagoons or shallow seas, such as those in the Bahamas or Yucatan or the South Pacific. In no case do these sediments form where there is the huge energy of floods or lots of mud stirred up by floodwaters. Particularly diagnostic is the fact that many of the fossils are extremely delicate (such as the lacy “moss animals,” or bryozoans), yet they are intact and undisturbed, which proves the flood cannot have occurred. Even more evocative are the delicate animals such as the sea lilies (crinoids) and lamp shells (brachiopods), which are sitting just as they sat in life, layer after layer growing over and over, undisturbed by high-energy currents and buried by lime mud (not flood-type mud) that gently filtered in around them without disturbing them. This is true of limestones like this around the world and in the geologic past, so the Grand Canyon is not a special case—and definitely not evidence of a supernatural flood. The same is true of the Toroweap and Kaibab Limestones, which form the rim of the Grand Canyon.

Above the Redwall Limestone are the alternating sandstones and shales of the Supai Group, followed by the red Hermit Shale. The sandstones of the Supai Group are full of small ripples and small cross-beds, features of gentle deposition in rivers, not raging floodwaters or muds settling out after flood movement has stopped. The Supai Group and Hermit Shale not only contain layer after layer of mudcracks (fig. 3.7D), clearly demonstrating that they dried out repeatedly, but also delicate ferns and other plant fossils preserved intact, which is hard to explain if they were created by energetic floodwaters.

One of the best lines of evidence is the distinctive white band that is visible just below the rim on both sides of the Canyon, known as the Coconino Sandstone. This unit has huge cross-beds (fig. 3.7E) that are only known to form in large-scale desert sand dunes, not underwater. They also have small pits that are characteristic of the impacts of raindrops. How did raindrops land on these surfaces if they were immersed in a great flood? Even stronger proof is that many of the dune surfaces are covered with trackways of land reptiles (fig. 3.7F). How does a creationist reconcile these dry sand dune features and dry land reptile trackways with a huge flood event? I’ve read the creationists’ attempts to explain these features, and they are classic examples of special pleading, twisting, and distorting scientific evidence as they thrash around in their completely unconvincing scenarios.

And the most impossible thing the creationists ask you to believe is this: the entire pile of sediments of the Grand Canyon sequence, soft, soupy, and supposedly deposited during a single flood event, was then eroded down to form the present-day Grand Canyon by the recession of the floodwaters. Wait a minute—didn’t the creationists just use the recession of the floodwaters and the settling out of still water to deposit the thick piles of postflood shales, sandstones, and limestones in the first place? Or if that’s not their scenario, then how did a soft pile of wet mud, sand, and lime hold up without slumping down and sliding into the gorge as the torrential retreating floodwaters rushed through? Did the supernatural flood also suspend the laws of gravity, too? Anyone with common sense can watch the Grand Canyon as it erodes today, with the long-hardened sediments (now sedimentary rocks) slowly weathering and eroding, dropping into the canyon by the action of gravity or by rains and small local canyon floods, and then slowly carried away by the Colorado River.

Even more revealing is the fact that if you trace the rock units of the Grand Canyon across distance, they change facies (gradually transform and intergrade sideways from one rock type to another). For example, in the Grand Canyon, the Pennsylvanian period (323–290 million years ago) is represented by the brick-red ledges and slopes of the Supai Group, which is composed of mudstones and sandstones deposited in broad rivers and plains. But, if you travel just 80 miles (130 km) to the west to the Arrow Canyon Range, just east of Las Vegas, Nevada, the same interval (between the Mississippian limestones below, and the Permian Coconino-Toroweap-Kaibab Formations above) is represented by a marine Bird Spring Limestone, full of the shells of foraminifera and brachiopods. About 300 miles (480 km) to the northwest, that same interval is represented by boulder conglomerate and sandstones shed from an ancient mountain range of the Antler orogeny that eroded away long ago and no longer exists. The fossils, and their position between nearly identical Mississippian limestones and Permian rocks, show that these Pennsylvanian rocks in Arizona and Nevada are all correlative and roughly the same age. Yet they look entirely different. These things are completely inexplicable if these rocks were all deposited as a worldwide uniformly consistent layer cake by a single Noah’s flood.

Or let’s follow the Permian rocks (Hermit Shale, Coconino Sandstone, and Toroweap and Kaibab Limestones) to the east of the Grand Canyon (fig. 3.8). By the time we get as far as Monument Valley, these units have all changed facies. The Toroweap and Kaibab Limestones have become thinner and thinner until they vanish completely near the Utah border. In their place is a thick sandstone (much thicker than the Coconino) known as the Cedar Mesa Sandstone, which forms the spectacular cliffs and spires of Monument Valley. This unit also interfingers in a complex non–layer cake way with several red shales known as the Organ Rock and Halgaito Formations, which are full of ancient mudcracks indicating repeated drying events. These are the soft units that erode away quickly and have caused the sandstone cliffs and spires of Monument Valley to keep collapsing over the centuries. If you follow those rocks to the northeast, you find that the Cedar Mesa Sandstone has been largely replaced by thick deposits of salt and gypsum. Today, we can find only one place where such deposits form: in dry lakes and salty lagoons where the high rate of evaporation removes the water and concentrates the salts into a brine that eventually dries up completely. There’s absolutely no way you can deposit hundreds of feet of salt and gypsum in a single flood event (especially since the same unit becomes mostly sandstones to the west). If a creationist tried to argue that it was formed as the flood finally dried up, then what about the hundreds of feet of sandstone, shale, and other rocks that lie above the salt and gypsum?

FIGURE 3.8. The flood geology model completely ignores the fact that rock formations, like the Permian sequence of the Grand Canyon, gradually change appearance, or facies, over distance. This panel diagram shows how the characteristic rocks of the Permian of the Grand Canyon are replaced by entirely different rock units as you move north and east through Utah, Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. (From Kunkle 1958; reprinted by permission of the Utah Geological Association)

The final clincher comes even farther to the northeast, into southwestern Colorado. The sandstones and shales of Monument Valley and the salt and gypsum deposits of the Four Corners change laterally into coarse pebbly sediments known as the Cutler Arkose. Today these materials are only found in thick alluvial deposits eroding out of mountains. They are clear-cut evidence that during the Permian there was a range of mountains in the area known to modern geologists as the Ancestral Rockies. But they look nothing like a flood deposit nor does their lateral transformation into salt and gypsum deposits to the south, or dune sands and mudcracked shales to the west, make any sense in the world of “layer cake” flood geology.

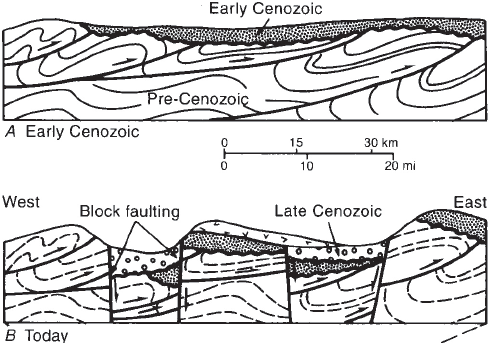

Creationists have always focused on the Grand Canyon because it seems to fit their “layer cake” notions of how sediments would settle out after Noah’s flood. But the Grand Canyon is also practically the only place in the world that looks this simple and undeformed. A more typical situation is the outcrops in the Basin and Range province of Nevada and Utah, just to the northwest of the Grand Canyon (fig. 3.9). There you do not have any horizontally layered rocks that might be called “Noah’s flood deposits.” Instead, you find ancient layers of fossiliferous Paleozoic rocks, cut up by faults, then buried by more layers of Mesozoic rocks, which are then cut by more faults. Which layers were deposited in Noah’s flood? Clearly the faulted Mesozoic layers are different in age from the Paleozoic ones that they cut across on fault planes. Where in the Bible is this complex sequence of older faults and folds cut by younger faults and still younger faults mentioned? Finally, the youngest deposits fill the basins in between the fault block ranges—and they are full of fossils of extinct mammals and plants from the Miocene and older beds. Where do they fit in the flood geology model? This is the kind of geology that is typical in most parts of the world and that real geologists deal with all the time. It is no surprise that real geologists don’t even bother to explain any of this with a simplistic flood model.

FIGURE 3.9. Creationists try to align relatively simple flat-lying sequences like the Grand Canyon with Noah’s flood and ignore the vast majority of geologic settings around the world that in no way resemble a “layer cake” that could be deposited by a flood. For example, in the Basin and Range province of Utah and Nevada, just north of the Grand Canyon, the geologic relationships are extremely complex. (A) Paleozoic and Mesozoic beds are faulted and folded many times, with Paleozoic beds full of marine shells overthrust above Mesozoic dinosaur-bearing beds (contrary to the idea that dinosaurs could outrun the marine invertebrates in the rising flood). These older beds are then eroded off and unconformably overlain with early Cenozoic beds containing fossil mammals. (B) The early Cenozoic beds were then cut by Miocene normal faults, and the basins were filled with late Cenozoic sediments containing extinct horses, camels, mastodonts, and other Miocene land mammals. None of this complex geometry could be explained by simplistic “Noah’s flood” models. (Modified from Prothero and Dott 2010)

We could go on and on with this point, but this should be sufficient for anyone with an open mind and common sense not blinded by religious dogmatism. In the 1600s and 1700s, long before Darwin, religious scientists like Thomas Burnet, Abraham Gottlob Werner, William Buckland, and others tried to explain the world’s rocks with the Noah’s flood story. In the 1830s, also before Darwin’s book was published, they gave it up completely, as the complexity of the real geologic record became apparent. The Noah’s flood model predicts a simple layer cake worldwide sequence of coarse flood gravels and sands, overlain by a worldwide mudstone deposit. By contrast, the real geologic record is highly complex and variable from region to region, with complex intertonguing contacts between units and facies that change dramatically over relatively short distances within the same part of the sequence. It is full of thousands of individual mudcracked layers and many different layers of salt and gypsum that simply cannot be explained by a single flood. There are thousands of different layers with delicate fossils in life positions, undisturbed by a single flood event.

All of this adds up to a simple conclusion: 200 years of mainstream geology (largely done by scientists who were very religious) has shown that the geologic record is far too complex for simplistic Bible myths. If the creationists were intellectually honest, they would face this fact, instead of imagining fantastic explanations for the Grand Canyon alone, and ignoring the remaining 99 percent of geology that cannot be twisted to fit their peculiar ideas. (For a blow-by-blow discussion, see www.talkorigins.org/faqs/faq-noahs-ark.html#georecord.) Real scientists are not allowed to twist and torture data to fit their preconceived conclusions or to ignore 99 percent of the data that cannot be made consistent with the flood geology model.

The most significant implication of flood geology and its fantasy view of the earth is a practical problem. Without real geologists doing their work, none of us would have the oil, coal, gas, groundwater, uranium, and most other natural resources that we extract from the earth. There are lots of devout Christians in oil and coal companies (I know many of them personally), but they all laugh at the idea of flood geology and would never attempt to use it to find what they’re paid to find. Instead, like the Clark and Block quotes above demonstrate, they have seen the complexity of real geology in hundreds of drill cores spanning whole continents and don’t even begin to try to interpret these rocks in a creationist mold (even though they may be devout Christians and believe much of the rest of the fundamentalists’ credo). If they tried, they’d find no oil and lose their jobs! As creationists keep trying to get their bizarre notion of flood geology inserted into classrooms and places like the Grand Canyon, we have to ask ourselves: Are we willing to give up the oil, gas, coal, groundwater, and uranium that our civilization requires? That would be one of the steepest prices we would pay if we listened to the creationists.

Alice laughed: “There’s no use trying,” she said: “one can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was younger, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

—Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass

Most creationists believe that the Noah’s ark story is historical fact. Never mind that there are actually two different stories in Genesis 6 and 7 from different sources that don’t even agree with one another, or that large parts of both flood myths are cribbed almost word for word from the much older accounts in the Epic of Gilgamesh (see chapter 2). Never mind that creationists must explain why one verse has seven pairs of clean animals on the ark, while another only has one pair. Creationist books are full of incredible mental gyrations needed to make the Noah’s ark story remotely believable. However, as I found out from my encounter with Gish, creationists will avoid discussing these points if they are brought up in debate, because they sound foolish and ruin the creationists’ credibility with most audiences. A number of expeditions have been sent to Mount Ararat in Turkey (the supposed landing site) and made fantastic claims that they have found evidence of the ark, but none of these have stood up to scrutiny, despite the claims made by some creationist books and TV shows.

First, let us start with what the Bible says and delve into the world of arkeology. McGowan (1984: chap. 5) and Moore (1983) discuss the logistical details of the Noah’s ark story at length, so I will not repeat their entire analysis here. A whole series of questions and problems come up when you look at the ark story in detail. The biggest problem is that a wooden boat the size of the ark would break up under the smallest stresses. This is a well-known problem in nautical engineering. Beyond a certain size, wooden vessels are simply not strong enough or flexible enough and begin to rip apart or leak catastrophically. The strength of wood as a vessel increases in size is not enough to hold the vessel rigid and intact. If Noah’s ark were indeed 137 meters (450 feet) long, as in most estimates, it would be larger than any wooden ship that has ever been built in history. The sailing ship Wyoming was 100 meters (329 feet) long, leaked constantly due to the problems with the flexing of the hull, and sank 14 years after its launch in 1910. So did the 99 meter (324 foot) barge Santiago, which sank in 1918. Two wooden British warships, the HMS Orlando and HMS Mersey, were 102 meters (335 feet) long, but were scrapped only a few years after they were built because they were not seaworthy. Yet Noah’s ark was allegedly about 30 percent larger than these boats that could not stay afloat and intact, despite the most advanced technology of wooden shipbuilding ever devised. Creationists sometimes mention legendary Chinese treasure ships of the fifteenth century that may have approached 137 meters, but if they were real and actually this big, they were just barges that barely moved, and none of them are known to have floated outside quiet harbors and rivers.

McGowan (1984:55) calculates that the biblical dimensions give a boat with about 55,000 cubic meters of internal volume. As we discussed earlier, there are at least 1.5 million species on earth today, which gives us only about 0.0367 cubic meters per species, or about one-third the capacity of a domestic oven—and these animals would have to be packed like shoeboxes stacked on top of one another to make this solution work. Clearly this is not enough space for most large animals. The pairs (or is it seven pairs?) of elephants, rhinos, and hippos would take up much of the ark all by themselves. The problem gets even more complicated if we consider that the true estimate is about 4 or 5 million species on earth.

The creationists, of course, are aware of this problem. When the flood myths were written, most ancient Middle Eastern cultures recognized only a handful of animals (domesticated plus wild). They paid no attention to insects, different kinds of fish, or many other less conspicuous forms of life, so they saw no problem in accounting for all living things that were important to them in a single boat. But the modern-day creationists must account for all of the millions of life forms on earth or else admit that some things have evolved from others since the days of Noah. They do this by claiming that Noah only took the “created kinds” (their translation of baramin in Hebrew) on the boat and that these kinds have since evolved into many more forms (a concession that evolution occurs!). By this method, they claim that there were only about 30,000 to 50,000 created kinds on board, but then that only gives each “kind” about a cubic meter to live in—still not much of an improvement.

Let’s look closer at the term baramin. It was created out of nothing by Seventh-Day Adventist Frank Marsh in 1941 by tacking two words together from a Hebrew glossary (bara, “created”; min, “kind”) without any idea how Hebrew actually works. Since almost none of the creationists read the Old Testament in the original Hebrew (or they would spot the problems and inconsistencies that make literal interpretation absurd), they don’t realize how ridiculous this term is, and why it doesn’t mean what they think it means. As I learned when I studied Hebrew, the Semitic root “b-r-a” (vowel points were not invented until centuries later) is translated “he created” or “he conjured,” so it is a past-tense verb, not a past participle of a verb, as Marsh used it. And min can be used to mean not only a “kind” but also a species, or even a sex. Slapped together in Marsh’s construction, the object min replaces the original subject Elohim (one of the names for the gods), so literally translated, baramin means “the species created,” not “god created”—and certainly not “created kinds” in any sense the scriptures use. If Marsh had known any Hebrew and wanted to create a grammatically correct translation of “created kind,” it would have been min baru (past participle). But given the consistently incompetent scholarship of creationists, I would never expect them to get this part right.

Leaving aside their ignorance of Hebrew, the whole topic of “baraminology” reminds one of a laughably poor imitation of science—science as imagined by kids at play or amateurs who are parroting the forms without understanding any of the principles or protocols or implications of the actual research, or the silly imitation of science in the movies and TV, where they spout scientific-sounding words that make no sense whatsoever. The focus of their “research” is to skim over the entire field of modern animal classification and then imagine ways to shoehorn hundreds of individual species and genera into the smallest possible number of categories. They don’t bother to work with actual animals, or get their hands dirty with the dissections and anatomical work that established the modern taxonomy of organisms, or spend the years in graduate school to obtain the kind of training necessary to understand and analyze molecular phylogenetic data, or wade into the gigantic literature of modern systematic theory since the days of George G. Simpson and Ernst Mayr and cladistics. No, that would require that they be trained in actual science, and confront the evidence for evolution that runs throughout life. Instead, they do superficial, high school–level “book report” types of analyses, where they cherry-pick ideas here and there from highly simplified Internet sources and Wikipedia articles. They know just enough science to pick up a stray factoid here and there without any understanding of the caveats and methods behind the data or the relative significance or importance of one kind of data versus another that only comes with years of graduate study in a field.

In reality, their baramin “solution” to minimizing the number of animals on the ark creates a whole new set of problems. Not only does it concede evolution from the created kinds, but the kinds have no basis in biology. When you examine the creationist literature or try to pin them down, sometimes “the kinds” are species, sometimes they are genera, and sometimes they are whole families, orders, or even phyla of animals (Siegler 1978; Ward 1965)! Creationists are so wildly inconsistent and their theories are so completely out of line with the known taxonomy of organisms that it is clear that a created kind is one of those slippery words that people use to weasel out of difficult spots. As Humpty Dumpty said to Alice (in Through the Looking-Glass), “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean.” Nevertheless, a lot of the creationist “research” focuses on just this fruitless, unscientific version of chasing their own tails, and they even have a name for it: baraminology.

Some creationists try to squirm out of the problem by claiming that the fish and marine invertebrates stayed outside the ark and lived through the flood. But this reveals their complete lack of understanding of basic biology. To a creationist, apparently, if it lives in the water, it’s all the same, but marine fish and invertebrates are highly sensitive to changes in salinity, so if the oceans were flooded by freshwater, these organisms would die immediately. If, on the other hand, these supernatural clouds rained marine seawater (a physical impossibility, because salt is mostly left behind when water evaporates), then the salty world-spanning waters would have killed all the freshwater fish and invertebrates, which cannot tolerate high salinities. Of course, pushing the aquatic forms off the boat and into the water doesn’t begin to solve the space or numbers problem because these forms account for only a few hundred thousand species.

To this point we have only addressed the issue of cramming thousands of species into shoebox-sized spaces stacked to the top of the ark. Where would they put all the food for so many animals? How did the carnivores survive without eating their neighbors? Finally, the most unpleasant thought of all: so many animals produce a lot of dung. Did Noah and his sons spend most of their 40 days and nights shoveling it out of the boat? Instead of evaluating a reasonable and testable hypothesis, the special pleading and twisting of the facts of nature makes it clear that we’re dealing with an explanation that is a load of dung (fig. 3.10).

FIGURE 3.10. Flood geology just doesn’t hold water. (Cartoon courtesy Los Angeles Times Syndicate)

We now have literally thousands of separate analyses using a wide variety of radiometric techniques. It is an interlocking, complex system of predictions and verified results—not a few crackpot samples with wildly varying results, as creationists would prefer to believe.

—Niles Eldredge, The Monkey Business

The principle that one rock layer is normally deposited on another older one (superposition) and the principle of faunal succession laid the framework for the relative geologic time scale by the 1840s, but geologists still could not attach numerical ages to these rock units or say whether they took thousands or millions or billions of years to deposit. It was clear by looking at the immense thicknesses of rock and their complexity (such as in the Grand Canyon example just discussed) that the rock record could not be explained by Noah’s flood. But there was no reliable “clock” in the eighteenth or nineteenth century that could tell us whether the earth was only 20 million years old (as physicist Lord Kelvin argued) or billions of years old (as most geologists since Hutton had estimated).

Then, in 1895, the discovery of radioactivity by Henri Becquerel provided the first mechanism to produce reliable numerical ages (formerly called “absolute” dates) on rocks. By 1913, geologists such as Arthur Holmes had developed the radioactive decay method and found rocks on earth that were at least 2 billion years old. Since then, numerous additional dates have been established for older and older rocks. The oldest known rocks on earth currently date to 4.28 billion years ago, and there are individual mineral grains that give dates of 4.3 to 4.4 billion years old (Dalrymple 2004). Rocks from the moon and meteorites are even older, with many samples giving ages of 4.5 to 4.6 billion years. Although we have no earth rocks that old yet, this is not surprising, because the earth has a dynamic crust that is constantly melting and recycling older material. It is amazing that earth materials as old as 4.4 billion years still survive. The moon and the meteorites, by contrast, have changed very little since their formation, so it would be expected that they preserve very ancient dates (for further details, see Dalrymple 2004). The earth, moon, and meteorites apparently formed at the same time from the primordial solar system, which is why we say the earth is also 4.6 billion years old.

The basic principles of radiometric dating are relatively straightforward and very well understood. Certain isotopes of elements, such as potassium-40, rubidium-87, uranium-238, and uranium-235, spontaneously break down or “decay” into atoms of different “daughter” elements (argon-40, strontium-87, lead-206, and lead-207, respectively, for the “parent” material just listed) by emitting nuclear radiation (alpha and beta particles and gamma radiation) plus heat. The rate of this radioactive decay is well known for all these elements and has been checked and double-checked in the laboratory hundreds of times. Geologists obtain a fresh sample of the rock, break it down into its component mineral crystals, and then measure the ratio of parent atoms to daughter atoms within the mineral. That ratio is a direct mathematical function of the age of the crystal.