The extent to which progress in ecology depends upon identification and upon the existence of sound systematic groundwork for all groups of animals cannot be too much impressed upon the beginner in ecology. This is the essential basis of the whole thing; without it, the ecologist is helpless, and the whole of his work may be rendered useless.

—Charles Elton, Animal Ecology

In the previous chapter, we briefly introduced the concept of systematics. However, we will not be able to talk about most of the fossils or animals in the rest of the book if we do not review the basic concepts of systematics and the major breakthroughs in systematic thought that have occurred in the past decades. Of all the topics in biology, systematics is the least understood by the general public, yet it is one of the most essential.

Most people are vaguely aware that there is a scientific system for naming and classifying organisms. This field is known as taxonomy. Most scientists who name and describe new species of animals and plants have to be familiar with its rules and procedures. But systematics is broader than just taxonomy. Systematics is “the science of the diversity of organisms” according to Ernst Mayr (1966:2) or “the scientific study of the kinds and diversity of organisms and of any and all relationships among them” in the words of George Gaylord Simpson (1961:7). Systematics includes not only taxonomic classification but also determining evolutionary relationships (phylogeny) and determining geographic relationships (biogeography). The systematist uses the comparative approach to the diversity of life to understand all patterns and relationships that explain how life came to be the way it is. In this sense, it is one of the most exciting fields in all of science.

Taxonomists and systematists may not be as numerous or well funded as other kinds of biologists, but everything else in biology depends on their classifications and phylogenies. If the physiologist or doctor wants to study the organism most similar to humans, taxonomists point to the chimpanzee, our closest relative. If ecologists want to study how a particular symbiotic relationship developed, they depend on the systematist for accurate classification of their organisms. Systematics provides the framework or scaffold on which all the rest of biology is based. Without it, biology is just a bunch of unconnected facts and observations.

Today, taxonomists are becoming scarce as funding dries up or goes to more glamorous fields that use big expensive machines. But this starves science at its heart. The humble systematist, collecting specimens in the field on a shoestring budget or analyzing specimens in museum drawers and jars, may not be as famous as the behavioral ecologists, watching animals in the wild, or molecular biologists with the white lab coats and million-dollar machines, but their work is just as essential. One of the hottest topics today, biodiversity, is the fundamental domain of the systematist. Many people are worried about how rapidly we’re destroying habitat and wiping out the species on earth, but without enough systematists to identify and describe these species, we have no idea how bad the problem is. Many ecologists who are working on this problem complain that there are no longer enough trained systematists to even begin to identify all the species in danger—yet the funding agencies continue to starve systematics, and most students stay away from it because there isn’t as much glamour or money. Likewise, the systematist is necessary for many other functions, like correctly identifying which pest species is causing problems or describing and naming new species that may someday hold the cure for a deadly disease.

God created, but Linnaeus classified.

Carolus Linnaeus

There are many ways to classify things. We do it all the time. We quickly identify cars on the road as “sedans,” “SUVs,” “minivans,” “pickups,” and the like, but our kids might just identify them as “red cars” and “silver cars” and so on. A car buff or police officer might be able to recognize the make and model of each car as it flashes by. Similarly, small libraries use the Dewey decimal system to classify their books by topics, but larger libraries use an entirely different system developed by the Library of Congress; the categories in each are entirely different. Both of these systems try to be as “natural” as possible, clustering books that belong in the same category, such as “Science” with subcategories like “Geology,” “Biology,” “Physics,” and “Chemistry.”

In nature, there are also many ways to classify things. Many native cultures use simple rules like “good to eat” versus “eat only in emergency” versus “inedible” versus “poisonous.” Even our own culture uses simple ecological properties to crudely classify things. For example, some people call nearly all marine life “fish,” including “shellfish” (which are mollusks), “starfish” (which are echinoderms), and “jellyfish” (which are cnidarians related to corals and sea anemones). In the 1600s and early 1700s, a number of different naturalists had proposed classification schemes for life, but they were arbitrary and highly unnatural. For example, they often lumped together everything with wings, including birds, insects, and flying fish, or things with shells, like armadillos, turtles, and mollusks. The eventual solution was developed by the Swedish botanist Carl von Linné, better known by his Latinized name, Carolus Linnaeus. From his experiences with plants, Linnaeus realized that the best classification was based on reproductive structures, primarily flowers, rather than in the confusingly similar leaves or trunks or roots. This “sexual system” for plant classification was published in 1752 and became the basis for modern plant taxonomy. Linnaeus also applied the same idea to animals, focusing on fundamental properties like the reproductive system and hair or feathers, rather than on superficial ones like flight or armor. His first classification, entitled Systema Naturae (The System of Nature) was published in 1735, and the tenth edition of 1758 is regarded as the starting point of modern taxonomy.

Although the original Linnaean classification became outdated as hundreds of new species were described, his basic principles are still used around the world. Every species on earth has a two-part name (binomen), consisting of the genus name (always capitalized and either underlined or italicized) and the trivial name (never capitalized, but also always either underlined or italicized). For example, we belong to the genus Homo (Latin for “human”) and the trivial name of our species is sapiens (Latin for “thinking”), so our full species name is Homo sapiens or H. sapiens. The trivial name can never stand by itself, but must always be paired with the genus because trivial names are used over and over, but a generic name can never be used for another animal. The genus (plural, genera) can be composed of a single species or more than one species. Our genus Homo includes not only H. sapiens, but also H. erectus, H. neanderthalensis, H. habilis, H. rudolfensis, and several other extinct species, such as the newly discovered H. naledi. Genera are clustered into larger groups called families, which always end with the suffix “-idae” in the animals and “-aceae” in plants. Our family is the Hominidae, while the Old World monkeys are the Cercopithecidae, and the New World monkeys are the Cebidae. Families are clustered into orders (which have no standardized ending or format), such as the order Primates (which includes all monkeys, apes, lemurs, and humans), the order Carnivora (cats, dogs, bears, and their flesh-eating relatives), or the order Rodentia (the rodents, the largest order of mammals on earth). Orders are then clustered into classes such as the class Mammalia, or mammals, including all the orders just listed. The class Mammalia is clustered along with the classes for birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish into the phylum Chordata (all animals with a backbone or its precursors). Finally, there are a number of phyla (mollusks, arthropods, worms, echinoderms, etc.) that cluster with the chordates in the kingdom Animalia.

Although this system is over 360 years old, it has powerful advantages. The Linnaean classification scheme is flexible, allowing groups and new taxa to be changed, shuffled, and inserted as the situation demands. Taxonomic names were traditionally based on Greek or Latin roots, or Latinized forms of other words, because Latin was the language of scholars in Linnaeus’s time. Although most scholars around the world no longer read Latin, the fact that the names are accepted worldwide means that no matter what language a biologist speaks, the names of the animals are consistent. You can pick up a journal article in an entirely different orthography, like Russian Cyrillic or Mandarin Chinese, and still recognize the Linnaean names. By contrast, every language has its own local names for familiar animals. Even within the United States, “gopher” could mean a small burrowing rodent in some regions, or a tortoise in others—but the scientific names for the rodent genus Geomys and the tortoise genus Gopherus are universally recognized and unambiguous.

When Linnaeus set up his “natural system,” his goal was to understand the mind of God by understanding how his handiwork was arranged. Ironically, the system he developed was hierarchical, showing that life has a branching structure like a tree or bush. That branching structure of life became one of Darwin’s best arguments for the fact of evolution (discussed in chapter 4). Taxonomy shifted its goals from theology to understanding life’s evolutionary history. Consequently, the practice of systematics has had to make some important decisions about what criteria are used in classification. Should taxonomy be based solely on evolutionary history or should other components (such as ecology) also be included? Ecologically speaking, many people lump all swimming vertebrates with fins together as “fish.” But not all fish are the same. Lungfish are actually more closely related to amphibians, reptiles, and us than they are to a tuna fish. In taxonomic terms, lungfish do not belong with fish but with the four-legged land animals in a group known as the Sarcopterygii (the lobe-finned fish and their descendants). Even though that is an accurate picture of evolutionary relationships, many biologists have trouble with thinking about organisms this way and prefer groups that reflect some ecology as well.

Evolution usually proceeds by speciation—the splitting of one lineage from a parental stock—not by the slow and steady transformation of these large parental stocks. Repeated episodes of speciation produce a bush. Evolutionary “sequences” are not rungs on a ladder, but our retrospective reconstruction of a circuitous path running like a labyrinth, branch to branch, from the base of the bush to a lineage now surviving at its top.

—Stephen Jay Gould, “Ladders, Bushes, and Human Evolution”

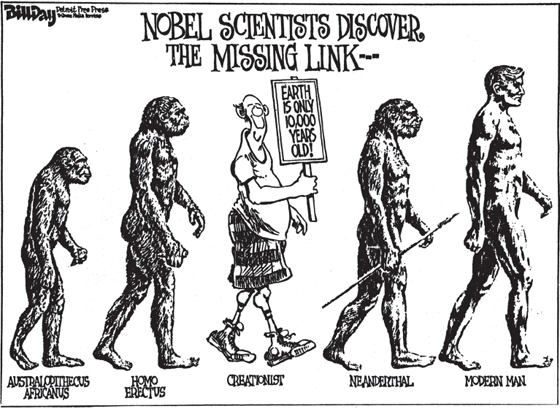

The realization that the classification of life forms a natural bushy or treelike pattern has other implications as well. As we saw in chapter 4, the older (pre-Linnaean) way of arranging nature was in the scala naturae or “ladder of creation,” with “lower” animals at the base, humans near the top, and divine beings up to God completing the ladder (figs. 5.1 and 5.2).

FIGURE 5.1. A parody of the classic “march from ape to man,” showing the cartoonist’s opinion of creationists. (Cartoon by Bill Day, Detroit Free Press; used by permission)

FIGURE 5.2. Evolution is not about life climbing the “ladder of nature” or the “great chain of being” from “lower” to “higher” organisms. Instead, evolution is a “bush” with many lineages branching from one another, and ancestors living alongside their descendants. (Drawing by Carl Buell)

But life is not a ladder, and there are no such things as “higher” or “lower” organisms. Organisms have branched off the family tree of life at different times in the geologic past, and some have survived quite well as simple corals or sponges, while others have evolved more sophisticated ways of living. Corals and sponges, although simple compared with other organisms, are not “lower” organisms, nor are they evolutionary failures for not advancing up the ladder. They are good at doing what they do (and have been doing for over 500 million years), and they exploit their own niches in nature without any reason to change whatsoever.

Nevertheless, this antiquated and long-rejected view of life as a ladder of creation still seems to lurk behind many people’s misunderstandings of biology and evolution. For example, it is common for creationists to ask, “If humans evolved from apes, why are apes still around?” The first time biologists hear this question, they are puzzled, because it seems to make no sense whatsoever—until they realize this creationist is still using concepts that were abandoned over 200 years ago. We now know that nature is not a ladder, but a bush (fig. 5.2). Lineages branch and speciate and form a bushy pattern, with the ancestral lineages living alongside their descendants. Humans and apes had a common ancestor about 7 million years ago (based on evidence from both the fossils and the molecular sequences), and both lineages have persisted ever since then. It is comparable to saying, “If you are descended from your father, why didn’t your father die when you were born? Why didn’t your grandfather die when your dad was born?” We all understand that we children branch off from our parents, and they do not have to die when we are born. Similarly, the human lineage branched off from the rest of the apes about 7 million years ago, but both are still around.

Likewise, the tendency to put things into simple linear order is a common metaphor for evolution—and also one of its greatest misperceptions. The iconic image is the classic “ape-to-man” sequence of organisms marching up the evolutionary ladder (fig. 5.1). This icon of evolution is so familiar that it is parodied endlessly in political cartoons and advertisements (for an extended discussion with many humorous examples, see Gould 1989:27–38). Most people think that this is an accurate representation of evolution. WRONG! Evolution is a bush, not a ladder! As we shall discuss in chapter 15, human evolution is quite bushy and branching, with multiple human species living side-by-side at certain times in the past 5 million years (fig. 15.3). The old-fashioned line of prehistoric humans marching “up the ladder” may be familiar and easy to visualize, but it is a gross oversimplification of the truth.

Another familiar example is the evolution of the horse, which we shall discuss in detail in chapter 14. About 100 years ago, when fossil horses were first discovered, it appeared that they were but a single lineage getting progressively larger and more advanced through time (fig. 14.2). But the past 100 years of collecting shows that horse history, too, was highly bushy and branching, with multiple lineages living at the same time (fig. 14.3). It may be convenient to visualize the general trend of horse evolution as a single linear sequence, but it is a very poor representation of their actual history.

Related to this concept is the misconception about “missing links.” Two centuries ago when people believed in the ladder of life, another related metaphor was the “great chain of being.” According to this idea, all life was linked into a great chain of increased complexity up the ladder to God. In his divine providence, God would not allow any link in this chain to vanish. As Alexander Pope wrote in An Essay on Man (1735),

Who sees with equal eye, as God of all

The hero perish, a sparrow fall…

Where, one step broken, the great scale’s destroy’d;

From Nature’s chain whatever link you strike,

Ten or ten thousandth, breaks the chain alike.

As Lovejoy (1936) showed, the concept goes back to the ancient Greeks and was widespread in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. At that time, it was used to justify the inequalities in human society and the divine right of kings and nobility, as well as to place all of nature in a religious context. Even as late as the 1790s, most naturalists (including Thomas Jefferson) refused to accept the idea that this great chain of being could be broken or that God would allow any of his creations to become extinct. But in the early 1800s, the great anatomist and paleontologist Baron Georges Cuvier showed conclusively that the skeletons of mastodonts and mammoths represented giant animals that could no longer be alive on earth today and must be extinct.

Even though the great chain of being was ultimately discredited when evolutionary theory came around in the mid-1800s, the imagery was still very powerful. A century before Darwin’s ideas of evolution, people saw the close similarity between apes and humans and postulated that there must be a “missing link” to complete the chain between us. This missing link metaphor then took on an evolutionary meaning after 1859, so that in the late nineteenth century, people wondered where the missing link fossil could be found that would connect humans to their ape ancestors. Eugène Dubois’s discovery of “Java Man,” “Pithecanthropus” (now Homo) erectus in 1891 was hailed as the first such discovery, although it is still a member of our own genus. Certainly, Raymond Dart’s 1924 discovery of the skull of the “Taung Child,” Australopithecus africanus, should have been sufficient to show that there were fossils that were truly intermediate between apes and modern humans and clearly not members of either group. As we shall discuss in chapter 15, the fossil record of extinct humans is now incredibly rich, so there are more “discovered links” than there are “missing” links. Nevertheless, the misconception about missing links leads some people to think that if a certain fossil hasn’t yet been found, then evolution cannot be true.

Creationists are particularly shifty when this topic comes up. If they bring up the discredited concept of a missing link (knowing that their audience doesn’t realize that the concept is invalid), they taunt the evolutionist to provide one. As I shall show in every remaining chapter of the book, the fossil record of transitional forms is truly amazing, so there is no shortage of fossils that could be called missing links (however erroneous the notion). But then the creationist will play a dirty trick. To divert attention away from the successful presentation of a transitional form, they will ask, “Where is the missing link between that fossil and another?” In other words, once you provide one intermediate between two groups, they ask for the other two “links” that connect the intermediate to each relative. Instead of conceding that they are beaten, they ask for more evidence, thus moving the goalposts and dishonestly demanding more evidence even after enough evidence has already been provided. It only goes to show how badly they misunderstand the fundamental concept: there is no such thing as a chain of being or a missing link!

Shermer (1997:149) describes their tactics this way,

Creationists demand just one transitional fossil. When you give it to them, they then claim there is a gap between these two fossils and ask you to present a transitional form between these two. If you do, there are now two more gaps in the fossil record, and so on ad infinitum. Simply pointing this out refutes the argument. You can do it with cups on a table, showing how each time the gap is filled with a cup it creates two gaps, which when each is filled with a cup creates four gaps, and so on. The absurdity of the argument is visually striking.

A good analogy of how creationists abuse the evidence before them and refuse to see the obvious connections between transitional fossils is lampooned in a number of clever editorial cartoons. One cartoon displays the word EVOL_T_ON on the board. One character says, “That can’t possibly spell evolution! There are too many gaps!” The other replies, “That must mean the answer to the puzzle is ‘CREATION.’ ” Another cartoon shows the sequence of hominid fossils with a couple of question marks scattered among the individual specimens. The caption reads, “If yu cn rea ths, don’ gme tht bulsit abut missng transitional forms in th evolutnry t ee!” Most people are capable of filling in the blanks and seeing patterns and connections, but creationists doggedly refuse to accept any evidence presented to them, no matter how clearcut.

Another analogy about seeing connections in transitional fossils is to imagine looking down on a bridge over a river. We can see the water flowing beneath it at one end, and the water flowing out the other side, but we can't actually see that the two bodies of water are connected if we are only looking down on the bridge. Our mind fills in that connection for us. The creationist refusal to see the connections between very similar fossils is just as illogical as not seeing the connections between the two masses of water. For them, if they can't see every bit of water flowing in full view, then there is no “transitional water” that links the water on one side to the water on the other side of the bridge.

Finally, the importance of recognizing the difference between chains/ladders and bushes/trees extends to another concept: mosaic evolution. Under the great chain of being metaphor, every creature up the chain or ladder is more advanced than those below it and more primitive than those above it. But evolution is a bush, not a ladder! Organisms evolve, but they do not always move up the ladder. As sponges and corals show, they may retain primitive features even though they have survived for 500 million years. In the case of many animals (especially many fossils), not every anatomical feature of the animal evolves at the same time. Some parts may be quite advanced, while others retain their primitive states. This is the idea of mosaic evolution. Like a mosaic, the whole organism is composed of many tiny parts, and not every part is identical or changes in the same way.

Human evolution, for example, is a classic mosaic. Some features, like our bipedal locomotion, appeared very early, while others, like our large brain size or tool use, appeared much later. Early anthropologists expected to find fossils of humans where every feature was evolving slowly and steadily toward the modern human condition, but that is not the case. Each feature can evolve at a different rate.

Likewise, the classic transitional fossil Archaeopteryx is a mosaic of both advanced birdlike features (asymmetric flight feathers, wishbone) and retained primitive dinosaurian features (long bony tail, long fingers with claws, long robust legs without grasping big toe, and many others). Creationists will exploit this misunderstanding of mosaic evolution to claim that because it has birdlike feathers, it is just a bird. Then they contradict themselves by misquoting Gould and Eldredge to the effect that Archaeopteryx is a mosaic, and thus is not a bird! The entire quotation is as follows:

At the higher level of evolutionary transition between basic morphological designs, gradualism has always been in trouble, though it remains the “official” position of most Western evolutionists. Smooth intermediates between Baupläne are almost impossible to construct, even in thought experiments; there is certainly no evidence for them in the fossil record (curious mosaics like Archaeopteryx do not count). (Gould and Eldredge 1977:147)

Creationist quote miners, in their effort to mislead and confuse people, only quote the last sentence, and then claim that Gould and Eldredge (1977) do not think Archaeopteryx is a good transitional form. As the complete quotation shows, they are only arguing that Archaeopteryx is a mosaic, not a smooth transition between body plans where every feature is intermediate. Lest there be any question that they have lied about Gould doubting that Archaeopteryx is an intermediate form, his article “The Telltale Wishbone” (in Gould 1980:267–277) should lay that issue to rest!

When more evidence is garnered, whether through the analysis of additional characters, through the discovery of new specimens, or by pointing out errors and problems with the original data sets, new trees can be calculated. If these new trees better explain the data (taking fewer evolutionary transformations), they supplant the previous trees. You might not always like what comes out, but you have to accept it. Any real systematist (or scientist in general) has to be ready to heave all that he or she has believed in, consider it crap, and move on, in the face of new evidence. That is how we differ from clerics.

—Mark Norell, Unearthing the Dragon

Taxonomy and systematics may not seem like glamorous disciplines, but neither are they boring, uncontroversial fields. Taxonomists are famous for getting into heated arguments with each other about how to define species, how to classify organisms, and how to draw their family trees. There are rules of taxonomy (International Codes of Zoological, Botanical, and Bacterial Nomenclature), but there is also a lot of room for interpretation as well. To a large extent, taxonomists learn their trade through sheer experience: studying enough specimens of their organisms and their close relatives, watching how other taxonomists practice their trade and solve tough problems, and doing their research in a way that the scientific community will approve and see fit to publish. For a century or more, there were some general rules about how to go about this, but nothing in the way of a truly rigorous method of deciding how to classify organisms, or how to draw their family trees. Many biologists (especially in the 1950s) regarded this state of affairs as deplorable and railed against the prevailing subjectivity of the “art of taxonomy.” In their minds, there must be a better way to make systematics more objective and quantifiable and less arbitrary to the whims of the systematist.

The first such unorthodox attempt of the 1950s and 1960s to reform the subjectivity and fuzzy methodology of the old systematics was known as numerical taxonomy, or phenetics. Its proponents tried to turn taxonomy into something that could be measured and coded into a computer program, and then “objective” results would emerge. Although this movement made some progress and pointed out many problems with the older system, eventually it failed because some of its assumptions were faulty and unworkable. In addition, it turned out that phenetics was not as objective as originally claimed. Subjectivity is still involved when scientists measure and record data and decide which characters to use and even when they run different computer programs on the same data. Numerical taxonomy ultimately lost steam as a movement when it turned out that the same computer program might give different answers for the same data, which made the entire objectivity advantage disappear.

But in the late 1960s, another systematic philosophy emerged to challenge the mainstream orthodoxy. Known as phylogenetic systematics, or cladistics, it was originally proposed by German entomologist Willi Hennig in 1950, but not widely followed until his German text was translated into English in 1966. Unlike the phenetic movement, which fizzled out soon after it was proposed, cladistics challenged the orthodoxy and eventually became mainstream itself, primarily because of its clear and rigorous methods and also because it worked to solve many previously insoluble problems. But in the 1960s and 1970s, the introduction of cladistics met with much resistance and controversy, as the more outrageous ideas proposed were rejected by older scientists who could not imagine changing the concepts that they learned as students. By the late 1980s, however, cladistic methods prevailed in the systematics of nearly every group of organisms.

I was fortunate to witness most of the stages of this revolution in systematics. I began as a graduate student at the American Museum of Natural History in New York in 1976, just as the cladistic revolution was in full swing, so I got to see all the major debates and got to know the key players. At the time, only the American Museum and a few other places accepted these ideas; the rest of the country looked at the “New York cladists” in horror as if we had a contagious disease. I gave my first professional talk at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in 1978 on cladistics of Jurassic mammals, and I was one of the few people to mention cladistics at the entire meeting. Less than a decade later, all of the systematic talks at this same meeting were entirely cladistic, and those who stubbornly tried to do things the old way struck us young Turks as musty old dogs who couldn’t learn new tricks.

New and outrageous ideas and challenges to the orthodoxy are always being proposed in science, but most unorthodox ideas don’t go very far. It’s not because science is inherently reactionary or conservative. On the contrary, there are always incentives for ambitious young scientists to make a name for themselves by challenging orthodoxy. But all new ideas must meet the test of peer review and scientific scrutiny and survive in the furnace of trial and error. Most such ideas fail because their limitations eventually become apparent. Cladistics became mainstream because it cleared up a lot of clutter in thinking and in practice and because it works.

What is cladistics, and why is it different from the older methods of classification? Hennig’s main insight was that the anatomical features, or characters, that we use to name and describe organisms, are not all the same. Every organism is a mosaic of advanced (or derived) features inherited from a very recent common ancestor and primitive features inherited from distant ancestors. For example, we humans have advanced features such as our large brain and bipedal posture, but we inherited our absence of tails from our ape ancestors (all apes lack tails) and our grasping hands and stereovision from our earliest primate ancestors (nearly all primates have stereovision and grasping hands with opposable thumbs). Likewise, we inherited our hair and mammary glands from our distant mammalian ancestors (all mammals have them) and our four-legged bodies and lungs from our distant tetrapod ancestors (all tetrapods, including amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, have them). If we wanted to define what makes us human, it would involve features related to our large brains and bipedality, our most recently developed evolutionary novelties, not our primitive features, such as a lack of tail, stereovision, grasping hands, hair, mammary glands, four legs, or lungs. The older classification schemes often mixed together primitive features and advanced features in their definitions, but Hennig pointed out that only the shared derived, or shared advanced, characters are really valid in defining natural groups.

We can define relationships based on these shared derived characters. Humans and monkeys (fig. 5.3) are more closely related to each other than they are to any other organisms in this diagram because they have many shared evolutionary novelties not found elsewhere in the animal kingdom, including opposable thumbs, stereovision, and many other features that define primates. A group including humans, monkeys, and cows could be defined by shared derived characters such as hair and mammary glands, unique features that define the class Mammalia. A group including mammals plus frogs could be defined on the shared presence of four legs and lungs, features that are found in all tetrapods. Likewise, sharks are more closely related to frogs and mammals than they are to lampreys because they have the advanced features of jaws and true vertebrae in their backbones. Notice that we did not use characters like jaws to define a group such as the mammals because jaws are primitive for mammals but derived at a much deeper level, at the level of the earliest jawed vertebrates (the gnathostomes). Characters are primitive or derived relative to the level at which they are being used, and according to Hennig, we must use them only at the level at which they first appear as evolutionary novelties.

FIGURE 5.3. Evolutionary relationships of an assortment of vertebrates, showing the shared specializations (evolutionary novelties) that support each branching point (node) on this cladogram.

Thus, by using only the shared derived characters, we can construct a branching diagram of relationships of any three or more organisms. This kind of diagram is known as a cladogram (fig. 5.3). Cladograms only make statements about who is related to whom and show the evidence of that relationship by listing the derived characters at the branching points, or nodes. The power of cladograms is that they make minimal assumptions about how, why, and when these changes evolved; they only show the pattern of relationships and not much more. More importantly, a cladogram is instantly testable. All of the characters are out on display on the nodes, naked and exposed for scrutiny. Anyone who wishes to do a better job can immediately look at all the evidence and try to come up with a better hypothesis by falsifying the existing cladogram. By contrast, the family trees drawn by the old school of taxonomy prior to cladistics were completely untestable. Taxonomists would draw up a vague branching diagram of relationships, but there was no way to see on what data they based their family tree and no way to test it easily without redoing all of their work.

For the uninitiated, this simplistic explanation of cladistic methods seems obvious. What was all the fuss about? Initially, it was because it was a shocking new method with unorthodox ideas and assumptions, a lot of new alien terminology (most of which I skipped for simplicity’s sake), and it was pushed by scientists who were not trying to make friends but win scientific battles. For a decade, the controversy was loud and bitter, and scientists often ended up calling each other names and insulting each other, both at meetings and in print. Most of the early, more controversial ideas either have been accepted by the mainstream or some of the more outrageous ideas have been quietly forgotten.

But a lot of the controversy involves things that are genuinely novel and hard for many who were accustomed to the older system to accept. Cladistics is called phylogenetic systematics because the cladogram is a kind of phylogeny or family tree of life, and it gives us a natural branching scheme for classification, the ultimate result of Linnaeus’s work. Cladists assert that classification should be a strict reflection of this phylogeny and nothing more. Any mixing of other factors (such as ecology) mixes shared primitive and derived characters and leads to confusion. Thus, many of the groups in the classification schemes we have learned are natural and phylogenetic, but others are not.

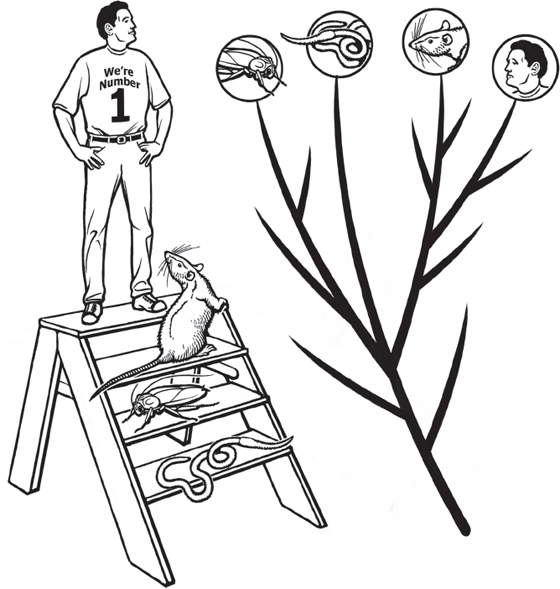

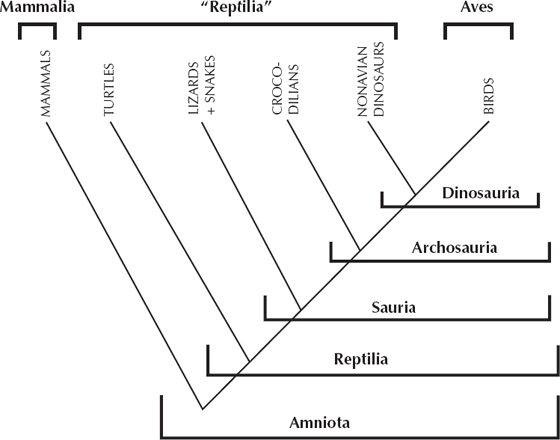

For example, we can draw a cladogram of the tetrapods (fig. 5.4) that shows their relationships based on hundreds of shared derived characters. This part of the process is not controversial and is accepted by all scientists. But a traditional scientist might want to cluster turtles, lizards, snakes, and crocodilians in the Reptilia but not want to place the birds within the Reptilia. Instead, they usually place birds in their own class Aves, parallel to and equal in rank to class Reptilia. A cladist, however, would say that defining Reptilia without including all of their descendants (including birds) mixes ecology with phylogeny and is unacceptable. For Reptilia to be a natural group, it must include birds as a subgroup because they are descended from reptiles. To a traditionalist, it seems natural (and comforting and familiar) to cluster with “reptiles” all of the four-legged land vertebrates that are sluggish and scaly and cold-blooded, and to elevate birds to their own class because they have changed so much from their reptilian ancestors. But this mixes ecology with phylogeny because scales and cold-bloodedness and the other features that turtles and crocodilians have (but birds don’t) are primitive for the entire group. To a cladist, those primitive characters are irrelevant to phylogeny and classification. Birds are a subgroup of reptiles in their classifications, and crocodiles are closer to birds than they are to snakes, turtles, and lizards. The only natural (or monophyletic) groups are those that are defined on shared derived characters and include all descendants of a common ancestor.

FIGURE 5.4. Different ways of classifying the same groups of organisms. Traditional classifications (top brackets) emphasize overall similarity and prefer to focus on the great evolutionary radiations of birds and mammals by placing them in their own classes, equal in rank to class Reptilia. A cladistic classification (lower brackets) only recognizes monophyletic groups, that is, groups that include all descendants of a common ancestor. “Reptilia,” as traditionally defined, is not monophyletic, because it does not include one descendant group, the birds. Instead, the natural monophyletic groups include amniotes (all land vertebrates), Reptilia (only if it includes birds), Sauria (the nonturtle reptiles), Archosauria (the group including crocodilians, dinosaurs, and birds), and Dinosauria (birds and the nonavian dinosaurs).

Let us look at another example closer to home. In older classification schemes, it was common to lump all of the great apes in the family Pongidae and place ourselves in the separate family Hominidae. In our anthropocentric arrogance, we always considered ourselves in a special group and exclude humans from the rest of the animal kingdom. But the evolutionary relationships of apes and humans are well established (fig. 5.5), and humans are just one branch among the great apes. Chimps and gorillas are much more closely related to us than they are to orangutans or gibbons, even though they all share primitive features of long, strong limbs and long hair and smaller brains and long snouts, and we have diverged the most in our bipedalism and nearly hairless skin and large brains with small faces. Cladistically speaking, it is invalid to place all the rest of the apes in a group without humans because that is a “wastebasket” group (like Reptilia without birds) that does not include all descendants of a common ancestor. To a cladist, the wastebasket (paraphyletic) family Pongidae is invalid, just as Reptilia without birds is paraphyletic and invalid. A natural (monophyletic) group would be to place us within the ape family Pongidae or to expand the Hominidae to include most or all of our close ape relatives. In fact, that is what has happened: most of the great apes are now in the family Hominidae. This makes a lot of sense logically, but it is tough for many to accept when they were trained to believe in the Pongidae.

FIGURE 5.5. Traditional classifications emphasize the shared primitive similarity of the “great apes” and place them in their own family Pongidae, while acknowledging the big differences between apes and humans by placing humans in their own family, Hominidae. However, to a cladist the family Pongidae is paraphyletic because it does not include all descendants (i.e., humans) of the common ancestor of the human-ape stem. In this framework, Hominidae must be expanded to include all the great apes (as most anthropologists now agree).

This is the brave new world of cladistic classification. Most classifications of animals and plants are partly monophyletic (e.g., birds and mammals are natural monophyletic groups) but mix in a lot of paraphyletic wastebaskets as well (including reptiles and amphibians, as traditionally defined). Some groups, like the invertebrates, are unnatural by definition, because invertebrates are defined by the shared primitive lack of a specialized feature, the vertebrae of the backbone. Bit by bit, however, more biologists are coming to terms with the cladistic revolution in systematics, accepting the results, and learning to use less familiar but natural groups such as “amniotes” and “tetrapods” rather than “reptiles” and “amphibians” as traditionally used. I am proud to say that my historical geology textbook (Dott and Prothero 1994) was the first to introduce cladistics to its textbook market and to avoid paraphyletic groups, and many other textbooks are beginning to catch on to what professional systematists had accepted more than 30 years ago.

That a known fossil or recent species, or higher taxonomic group, however primitive it might appear, is an actual ancestor of some other species or group, is an assumption scientifically unjustifiable, for science never can simply assume that which it has the responsibility to demonstrate…. It is the burden of each of us to demonstrate the reasonableness of any hypothesis we might care to erect about ancestral conditions, keeping in mind that we have no ancestors alive today, that in all probability such ancestors have been dead for many tens of millions of years, and that even in the fossil record they are not accessible to us.

—Gary Nelson, “Origin and Diversification of Teleostean Fishes”

Fossils may tell us many things, but one thing they can never disclose is whether they were ancestors of anything else.

—Colin Patterson, Evolution

Some aspects of cladistic theory have proven more difficult for many scientists to accept. For example, a cladogram is simply a branching diagram of relationships among three or more taxa. It does not specify whether one taxon is ancestral to another; it only shows the topology of their relationships as established by shared derived characters. In its simplicity and lack of additional assumptions, it is beautifully testable and falsifiable, so it meets Popper’s criterion for a valid scientific hypothesis. The nodes are simply branching points supported by shared derived characters, which presumably represent the most recent hypothetical common ancestor of the taxa that branch from that node. But strictly speaking, cladograms never put real taxa at any nodes, but only at the tips of the branches.

Many scientists, however, would like to say more than just “taxon A is more closely related to taxon B than it is to taxon C.” Instead, they would draw relationships with one taxon being suggested as ancestral to another. This is the more traditional family tree type of phylogeny, which not only suggests relationships, but shows a pattern of ancestry and descent as well. But as Tattersall and Eldredge (1977) point out, a family tree makes far more assumptions than does a cladogram. Some people are happy to make those assumptions, but the strict cladists are not so comfortable with them.

The biggest sticking point is the concept of ancestry. We tend to use the term “ancestor” to describe certain fossils, but we must be careful when making that statement. If we want to be rigorous and stick to testable hypotheses, it is hard to support the statement that “this particular fossil is the ancestor of all later fossils of its group,” because we usually can’t test that hypothesis. Because the fossil record is so incomplete, it is highly unlikely that any particular fossil in our collections is the remains of the actual ancestor of another taxon (Schaeffer et al. 1972; Engelmann and Wiley 1977).

But there’s another reason why cladists avoid the concept of ancestry. To be a true ancestor, the fossil must have nothing but shared primitive characters compared to its descendants. If it has any derived feature not found in a descendant, it cannot be an ancestor. Consequently, for decades, traditional taxonomists looked only at shared primitive characters so they could construct ancestor-descendant trees, thereby missing all the derived characters that showed they were on the wrong track. One of the great advantages of cladistics is that it has solved many previously insoluble problems by getting away from paraphyletic wastebasket groups and “ancestor worship” and focusing on derived characters only. For these reasons, hard-core cladists like Gary Nelson (quoted earlier) refuse to recognize the concept of ancestor at all, except in the hypothetical sense of the taxa at the nodes of the cladogram. Instead of ancestor and descendant, cladists prefer to talk about two taxa at the tips of the branches as being sister groups. Neither is ancestral to the other, but they are each other’s closest relatives.

But there are circumstances where the fossil record is so complete that it is possible to say that “the fossils in this population represent the ancestors of this later population.” My friend and fellow former graduate student Dave Lazarus (now a curator at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin) and I (Prothero and Lazarus 1980) provided just such an example from the extraordinary fossil record of planktonic microfossils. In these unusual circumstances, we have deep-sea cores covering all of geologic time since the Jurassic for most of the world’s oceans and every centimeter of sediment in most of those cores is filled with thousands of microfossils. With an extraordinarily dense and continuous record such as this, we really can say that we have sampled all the fossil populations that lived in the world’s oceans and can establish which samples are most likely the ancestors of later populations. Since our paper, a number of studies have been done to establish how complete the fossil record needs to be to determine the probability that one population is ancestral to another (Fortey and Jefferies 1982; Lazarus and Prothero 1984; Paul 1992; Huelsenbeck 1994; Fisher 1994; Smith 1994; Clyde and Fisher 1997; Hitchin and Benton 1997; Huelsenbeck and Rannata 1997). Nowadays, paleontologists are a lot more relaxed about the concept of ancestry than they were during the early, bitterly polarized debates over cladistics in the 1970s. Most paleontologists use the word ancestor (as I will throughout this book) very loosely to describe a fossil that has all the right anatomy and is older in time to potentially be ancestral to some later form. But we all recognize subconsciously that, in the strictest sense, telling whether a particular fossil is actually the ancestor of another is not a testable hypothesis. Instead, we look to fossils to show us the transitional anatomical features of ancestors that illustrate the path that evolution took.

Naturally, this debate, which revolves around subtle philosophical distinctions about ancestry, has been a bonanza for the quote-mining creationists. They pull dozens of quotations (like the one from Gary Nelson) completely out of the context I have just described and claim that these statements show that there are no such things as ancestors in the fossil record. (Prothero and Lazarus [1980] disproved that decisively.) The debate was all about whether we could tell whether a particular fossil could be recognized as an ancestor and how to do phylogeny, but even the most hard-core cladists do not doubt that ancestors existed! None of the debate is about whether life has evolved. After all, what would be the point of doing a cladogram, which is a phylogeny, if you didn’t accept the fact of evolution?

The most outrageous case was when a creationist spy named Luther Sunderland snuck into a closed scientific meeting of the Systematics Discussion Group at the American Museum in 1981 with a hidden tape recorder. At this time in the long history of debates on cladistics, many of the most extreme advocates were calling themselves “pattern cladists.” They no longer followed neo-Darwinism (as we discussed in chapter 4) and all the convoluted scenarios that had been built on top of simple phylogenetic diagrams to create complicated family trees with many additional assumptions. Instead, they argued that pure science was simply the testable hypotheses of the patterns of cladograms and nothing more. My friend, the distinguished paleoichthyologist Colin Patterson of the Natural History Museum in London, was talking about pattern cladism and how he had abandoned many of the assumptions about evolution that he had once held, including the recognition of ancestors in the fossil record. He was now only interested in the simplest hypotheses that were easily tested, such as cladograms. But, of course, taken out of context, it sounds as though Colin doubted that evolution had taken place, yet he said nothing of the sort! Colin was speaking in a kind of “shorthand” that makes sense to the scientists who understand the subtleties of the debate, but means something entirely different when taken out of context. I was at that meeting and was stunned to read afterward about Sunderland’s account of what had happened because I remembered Colin’s ideas clearly and could not imagine how they could be misinterpreted. For decades afterward, Colin had to explain over and over again what he had meant, and why he did not doubt the fact that evolution had occurred, only that he no longer accepted a lot of the other assumptions about evolution that neo-Darwinists made. Unfortunately, Colin died in 1998 while he was still in his scientific prime, unable to continue fighting these misinterpretations of his ideas that continue to be propagated by the creationists.

One no longer has the option of considering a fossil older than about eight million years as a hominid no matter what it looks like.

—Vincent Sarich, 1971

As was pointed out in chapter 4, one of the most powerful corroborations of Darwin’s evidence of the branching structure of life is that we can see that branching pattern by comparing the molecules in nearly every cell in every living thing (e.g., fig. 4.7). This was evidence that not even Darwin could have anticipated and convincing proof of the fact that life has evolved. Whether one looks at the DNA sequences directly or at other nucleic acids like mitochondrial DNA, or the RNAs, or the protein sequences in any other number of biochemicals—cytochrome c, hemoglobin, alpha lens crystalline, and many other proteins—the answer nearly always comes out the same. To paraphrase the Bible, every one of our cells declare the handiwork of evolution! It is a simple calculation to show that these identical branching patterns in every biochemical system in an organism are not random and could not occur unless that branching pattern were due to common ancestry.

Molecular phylogeny emerged in the 1960s with very crude methods, such as hybridizing DNA strands from different animals to see how similar their DNAs were (and therefore their evolutionary distance). Other methods compared the strength of the immune response (more closely related organisms have stronger immune responses than distantly related organisms, because the former have more genes in common than the latter). But since the 1990s, especially with the ability of the PCR (polymerase chain reaction) to produce lots of copies of DNA, allowing us to read the DNA rapidly, we now have the full DNA sequence of a number of organisms, including fruit flies, lab rats, mice, and rabbits, several domesticated animals, the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, and most of our ape relatives. The mitochondrial DNAs of many apes were sequenced as early as 1982, but the entire chimpanzee nuclear DNA sequence was not completed until August 2005. Human nuclear DNA was sequenced in 2001 by the Human Genome Project and also by Craig Venter’s lab. From all these studies, we now have a powerful tool to compare the genetic codes of a wide range of organisms. These data not only show us how we differ from other organisms but also (especially in the case of human DNA) allow us to find out what genes code for what parts of the body and where in the DNA the genes for inherited diseases occur. Many scientists hail the decoding of human DNA as one of our greatest scientific achievements ever because of its potential not only to answer scientific questions but also to cure many diseases.

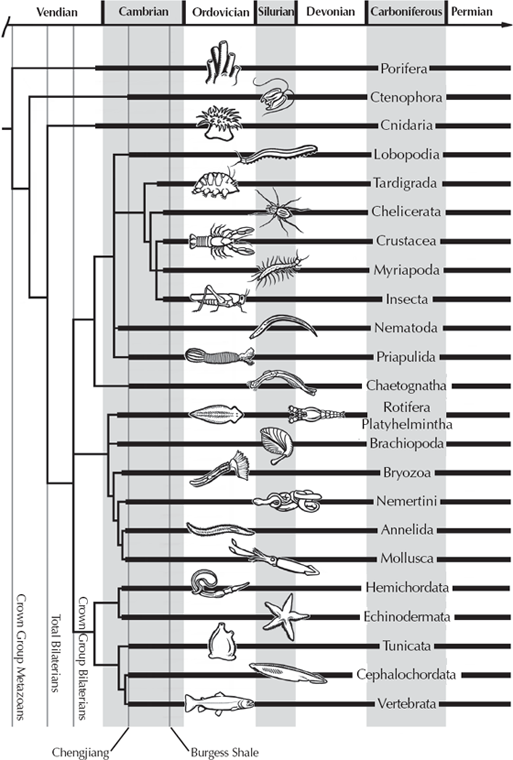

Molecular approaches have been particularly useful where there isn’t much evidence from the anatomy or the fossil record of organisms to determine their evolutionary relationships. For example, the external form of most bacteria is pretty stereotyped, and most early bacteriologists underestimated their diversity. With the advent of genetic analysis, however, scientists such as Carl Woese have shown that there are several different kingdoms of bacteria, including the most primitive organisms of all, the Archaebacteria, which mostly live in extreme environments such as hot springs and anoxic conditions. Scientists have debated for years about how animals, plants, fungi, and bacteria might be related, but molecular phylogeny has provided an answer that could never have been solved by traditional methods (fig. 5.6). The relationships of the major groups of multicellular animals were also hotly debated for over a century, but molecular techniques, in combination with newer ideas about embryology and anatomy, have provided an answer that is no longer disputed (fig. 5.7). Thus the molecular evidence provides an independent way of discovering the family tree of life and, in many instances, has given us answers that could not have been obtained by any other method.

FIGURE 5.6. The fundamental tree of life derived from molecular data, showing the major kingdoms of prokaryotes (Eubacteria, Archaebacteria, and many other microbes), and the small side branch of eukaryotes (plants, animals, and fungi).

FIGURE 5.7. The branching history of the animals, based on molecular data. (Drawing by Carl Buell; modified from Briggs and Fortey 2005: fig. 2)

This is not to say that every molecular study works perfectly or that molecular phylogenies are always superior to other methods. Like any other characters used in a phylogenetic analysis, molecular changes can be viewed as primitive and derived. But unlike anatomical characters, most molecular changes are limited to the four nucleotides (adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine), so there are only a limited number of possible changes. Consequently, if a gene is going to change, it can very easily return to the primitive condition, since that is the only alternative. This generates some “noise” in the molecular signal. In recent years, sophisticated methods have been used to detect this noise and filter it out. Likewise, the “clocklike” mutation rate hypothesis sometimes fails, because some organisms or taxonomic groups seem to have higher or lower than average rates of mutation, so there are still debates when molecular clock estimates give ages of branching points in evolution that are much too old to match the fossil record.

Still, there have been some remarkable successes. For years, paleoanthropologists such as Elwyn Simons and David Pilbeam argued that Ramapithecus, a fossil from beds in Pakistan that are 12 million years old, was the earliest member of our family Hominidae. If that were true, then the ape-human split would be older than 12 million years ago. But molecular biologists Vince Sarich and Allan Wilson of Berkeley looked at many different biochemical systems (starting with the simple immunological distance method) and always concluded that the divergence point between apes and humans was 5–7 million years ago. During the 1970s and early 1980s, there were many bitter debates over the point, so that Sarich was even quoted as saying that a fossil older than 8 million years old cannot be a hominid, no matter what it looks like! But in the late 1980s, additional, more complete fossils were found in Pakistan that showed that Ramapithecus was more like an orangutan and was actually a member of the genus Sivapithecus. In this case, the molecular biologists were right, and the paleontologists who staked their careers on Ramapithecus had to lick their wounds.

Likewise, Vincent Sarich was one of the first (based on molecular evidence) to say that whales were descended from even-toed hoofed mammals (the Artiodactyla) and particularly closely related to the hippopotamus. That radical idea was backed up by many more molecular studies and was finally corroborated in 2001 when two different groups of paleontologists (Gingerich et al. 2001; Thewissen et al. 2001) found the ankle bones of two different kinds of primitive whales from Pakistan that showed their relationships to the artiodactyls (see chapter 14). But for the many successes of molecular biologists, there have been some embarrassments. One study (Graur et al. 1991) concluded that guinea pigs were not rodents! This was quickly shot down by numerous other molecular labs (e.g., Cao et al. 1994) that showed the flaws in the analysis. No method in science is perfect, but molecular methods have proven very powerful, and there are so many checks and balances in the peer-review process that if one lab makes a mistake, other labs correct it. But if many labs get the same results from different molecules, then that is probably good evidence that they are onto something.

From the most remote period in the history of the world organic beings have been found to resemble each other in descending degrees, so that they can be classed in groups under groups. This classification is not arbitrary like the grouping of the stars in constellations. The existence of groups would have been of simpler significance, if one group had been exclusively fitted to inhabit the land and another the water; one to feed on flesh, another on vegetable matter, and so on; but the case is widely different, for it is notorious how commonly members of even the same subgroup have different habits…. Naturalists, as we have seen, try to arrange the species, genera, and families in each class, on what is called the Natural System. But what is meant by this system? Some authors look at it merely as a scheme for arranging together those living objects which are most alike, and for separating those which are most unlike…. But many naturalists think that something more is meant by the Natural System; they believe that it reveals the plan of the Creator; but unless it be specified whether order in time or space, or both, or what else is meant by the plan of the Creator, it seems to me that nothing is thus added to our knowledge…. I believe that this is the case, and that community of descent—the one known cause of close similarity in organic beings—is the bond, which though observed by various degrees of modification, is partially revealed to us by our classifications.

—Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

As this discussion of systematics has shown, there are many different methods for deciphering the history of life. From comparison of their external and internal anatomical features, to the similarities in embryonic history, to the details of the molecules in every cell, the branching history of life is revealed in nearly every aspect of organisms. The fact that so many systems give the same answer makes it very robust. If we can’t resolve the phylogeny from the anatomy, perhaps the molecules will help out. If the fossil record is poor in one particular group, we look to other sources of data. But if the fossil record or anatomical data is excellent, we are cautious about molecular conclusions that differ widely from our paleontological estimates. Thus, although no one method is perfect all the time, each method has its own strengths and weaknesses that allow us to decipher the problem, one way or another.

In addition, the advent of rigorous testable methods of phylogenetic reconstruction through cladistic analysis of anatomical details and of molecular sequences has made our efforts at determining the true history of life more successful than ever before. When I was a graduate student, many areas of evolutionary history were controversial and poorly resolved, based on the evidence that was available in the 1970s. But one after another, the Gordian knots have been cut. The phylogeny of the placental mammals was an unsolved mystery that was already two centuries old when scientists at the American Museum, such as Malcolm McKenna, Mike Novacek, Earl Manning, and I, tackled the problem. By the late 1980s, we had solved many aspects of the problem using cladistic analysis (see the papers in the volumes edited by Benton [1988a, 1988b] and Szalay et al. [1993]), and most studies published since then have corroborated our original topology (although there are some slightly different answers from the molecular world, and the differences are still to be resolved). Likewise, the deciphering of the phylogeny of life (fig. 5.6) and of the major groups of animals (fig. 5.7) are great achievements that have resolved over a century of controversy. Today, hundreds of systematists are at work solving these important problems, trying to test older hypotheses with new data, and working to resolve the issues even more definitively.

From the vaguely formulated hypotheses of ancestry published only a generation ago, we are now in a new age of understanding of life’s history (see Dawkins 2004). Where we once knew very little about its true pattern, we now have multiple lines of evidence that converge on a common answer and give a robust solution corroborated and tested many different ways that is almost certainly “the truth” (as much as we can use that term in science). In the chapters that follow, we may find that we are missing evidence from fossils at a certain interval or from anatomy at another. Contrary to creationists’ claims, there are always additional lines of evidence that allow us to decipher that phylogenetic problem. We are always continuing to move forward and find new answers, but we have already learned more in the past two decades than we did in all previous centuries. We no longer have to use the guesswork that creationists criticize because the tree of life is now as well known as almost any other fact of nature.

The great molecular biologist Emile Zuckerkandl and the Nobel-Prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling said it best over 50 years ago:

It will be determined to what extent the phylogenetic tree, as derived from molecular data in complete independence from the results of organismal biology, coincides with the phylogenetic tree constructed on the basis of organismal biology. If the two phylogenetic trees are mostly in agreement with respect to the topology of branching, the best available single proof of the reality of macro-evolution would be furnished. Indeed, only the theory of evolution, combined with the realization that events at any supramolecular level are consistent with molecular events, could reasonably account for such a congruence between lines of evidence obtained independently, namely amino acid sequences of homologous polypeptide chains on the one hand, and the finds of organismal taxonomy and paleontology on the other hand. Besides offering an intellectual satisfaction to some, the advertising of such evidence would of course amount to beating a dead horse. Some beating of dead horses may be ethical, when here and there they display unexpected twitches that look like life. (Zuckerkandl and Pauling 1965:101)

For Further Reading

Adoutte, A., G. Balavoine, N. Lartillot, O. Lespinet, B. Prudhomme, and R. de Rosa. 2000. The new animal phylogeny: Reliability and implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 97:4453–4456.

Arthur, W. 1997. The Origin of Animal Body Plans: A Study in Evolutionary Developmental Biology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dawkins, R. 2004. The Ancestor’s Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Foote, M. 1996. On the probability of ancestors in the fossil record. Paleobiology 22:141–151.

Hennig, W. 1966. Phylogenetic Systematics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Hillis, D. M., and C. Moritz, eds. 1990. Molecular Systematics. Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer.

Lazarus, D. B., and D. R. Prothero. 1984. The role of stratigraphic and morphologic data in phylogeny reconstruction. Journal of Paleontology 58:163–172.

Nielsen, C. 2001. Animal Evolution: Interrelationships of the Living Phyla. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Patterson, C. 1981. Significance of fossils in determining evolutionary relationships. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 12:195–223.

Patterson, C., ed. 1987. Molecules or Morphology in Evolution: Conflict or Compromise? New York: Cambridge University Press.

Prothero, D. R. 2004. Bringing Fossils to Life: An Introduction to Paleobiology. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Prothero, D. R., and D. B. Lazarus, 1980. Planktonic microfossils and the recognition of ancestors. Systematic Zoology 29:119–129.

Runnegar, B., and J. W. Schopf, eds. 1988. Molecular Evolution in the Fossil Record. Lancaster, Pa.: Paleontological Society Short Course Notes 1.

Schaeffer, B., M. K. Hecht, and N. Eldredge. 1972. Phylogeny and paleontology. Evolutionary Biology 6:31–46.

Schoch, R. M. 1986. Phylogeny Reconstruction in Paleontology. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Smith, A. B., and K. J. Peterson. 2002. Dating the time of origin of major clades: Molecular clocks and the fossil record. Annual Reviews of Earth and Planetary Sciences 30:65–88.

Tudge, C. 2000. The Variety of Life: A Survey and a Celebration of All the Creatures That Have Ever Lived. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wiley, E. O. 1981. Phylogenetics: The Theory and Practice of Phylogenetic Systematics. New York: Wiley Interscience.

Woese, C. R., and G. E. Fox. 1977. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: The primary kingdoms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 74:5088–5090.