On a sunny day in late July, I am off to North Pole to examine these vestiges [of ancient life]. Heat and dust permeate the cab as our Land Rover rattles over the rutted dirt track. There are flies everywhere. This North Pole, you see, lies in northwestern Australia—its name, with characteristic Aussie humor, marking one of the hottest places on earth.

—Andrew Knoll, Life on a Young Planet

How did life on earth begin? This is one of the most fascinating and controversial topics in science. Unlike many of the other areas of life’s history that we discuss in the remaining chapters, we have only a few fossils to guide us. The oldest fossils that are clearly formed by living things are microscopic fossils of cyanobacteria (formerly mislabeled “blue-green algae,” but they are not true algae) from 3.5-billion-year-old rocks of the Warrawoona Group near North Pole in Western Australia. In addition to these microfossils, there are layered domed structures known as stromatolites (fig. 6.1) that are produced by cyanobacterial mats (which are still producing such structures today) from the Warrawoona Group (fig. 6.2). Just slightly younger are numerous even better microfossils and stromatolites from rocks dated at 3.4 billion years from the Fig Tree Group of South Africa. As this book went to press, possible stromatolites dated at 3.8 billion years old were reported from Greenland, which would be the oldest fossils known if they are indeed stromatolites.

FIGURE 6.1. The concentric layers of the cabbage-like domed cyanobacterial mats known as stromatolites, here sliced off at the top by a glacier, now found in Lester Park, New York. (Photo by the author)

FIGURE 6.2. (A–E) Filamentous cyanobacterial microfossils from the 3.46-billion-year-old rocks of the Warrawoona Group, North Pole, Western Australia, showing the distinctive chains of cells. These are virtually identical to (F) (shown on next page), the modern filamentous cyanobacterium, Lyngbya, in every detail of the size, shape, and arrangement of the cells. (Photos courtesy J. W. Schopf)

All of these microfossils are simple filaments with a number of cells in a row, many with distinctive structures that are virtually indistinguishable from their modern counterparts. So we know for sure that bacteria and other simple prokaryotic (lacking a discrete nucleus) cells were present 3.4–3.5 billion years ago, but so far we have not found any older fossils. This is not surprising, given that there are very few places on earth with rocks any older than 3.5 billion years, and most rock that old has already been heavily deformed, cooked by metamorphism, or otherwise so altered that there is little chance of any fossils surviving. There are rocks from the Isua Supracrustals in west Greenland that have distinctive organic molecules in them that are unique to living systems, suggesting that life was present 3.8 billion years ago (Schidlowski et al. 1979; Mojzsis et al. 1996), and these are the rocks that also yield the possible stromatolites as well (Nutman et al. 2016).

Certainly, it is likely that life was already established by 3.8 billion years ago. Whether it was possible for life to get a foothold on earth before then is still debated. Before 3.9 billion years ago, the earth was still heavily bombarded by leftover debris from the formation of the solar system, which probably vaporized the oceans of the earth many times. (We know this because most of the impact craters on the moon, which must have suffered through the same bombardment, date from 3.9 billion years and older.) Scientists call this time the period of “impact frustration.” Most geologists did not think the earth could have cooled enough for liquid water to condense and form oceans much before 4.0 billion years ago, but tiny zircon grains from Australia were recently discovered that seem to have a distinctive chemistry indicating oceans as early as 4.3–4.4 billion years ago (Wilde et al. 2001; Valley et al. 2002). If so, then the earth’s surface cooled down to below 100°C (the boiling point of water) in only 250,000 years after its formation 4.65 billion years ago. There is nearly a billion years of time between when the first oceans form and the first clear fossils are known, plenty of time for life to evolve (more than once, if necessary), given these constraints.

Because these earliest fossils are tiny carbonized films preserved in cherts and flints, they provide little evidence for the chemical processes that formed life. All the organic chemicals in them have long been transformed by heat and pressure into other carbon compounds (usually pure carbon in the form of graphite, the “lead” in your pencil). We have only their shapes (fig. 6.2) to demonstrate that they were once living things. For earlier stages in this process, we cannot use the fossil record. Instead, we must try an experimental approach, using the constraints imposed by our knowledge of earth’s history and the nature of organic chemistry to find possible solutions. Naturally, some people (especially creationists) label this as “guesswork” and refuse to accept any of the experimental evidence to understanding life’s origins. They prefer to just say “God did it” and stop there. They are welcome to their opinions, of course, but as we explained in chapter 1, no true scientist falls back on this “god of the gaps” approach. The supernatural hypothesis is simply untestable and leads nowhere. Scientists may not have all the answers to this very complex and difficult problem, but they are not sitting on their hands or surrendering to the unscientific supernatural approach. They are constantly trying new experimental approaches and (as we shall soon see) have made a huge amount of progress—much more than creationists realize.

It is often said that all the conditions for the first production of a living organism are now present, which could ever have been present. But if (and oh! what a big if!) we could conceive in some warm little pond, with all sorts of ammonia and phosphoric salts, light, heat, electricity, &c., present, that a proteine [sic] compound was chemically formed ready to undergo still more complex changes, at the present day such matter would be instantly absorbed, which would not have been the case before living creatures were found.

—Charles Darwin, letter to Joseph Hooker

The first scientific suggestions about the origin of life were made by several people, including Darwin himself in this 1871 letter to his friend, botanist Joseph Hooker. Darwin speculated that a “warm little pond” with the right combination of chemical compounds (usually called the “primordial soup”) and the right sources of energy could produce proteins. But organic chemistry was still in its infancy back then, so little could be done to follow this suggestion. In the 1920s, the Russian biochemist A. I. Oparin and the British geneticist J. B. S. Haldane (also one of the fathers of neo-Darwinism mentioned in chapter 4) independently suggested that the earth with a reducing atmosphere of nitrogen, carbon dioxide, ammonia (NH3), and methane or “natural gas” (CH4) would be the ideal primordial soup for producing simple organic compounds.

The most important breakthrough occurred in 1953, when a young graduate student at the University of Chicago named Stanley Miller heard about Oparin’s hypothesis from his advisor, Nobel Prize–winning chemist Harold Urey. They decided to try an experiment along the lines suggested by Oparin and Haldane to see whether such a primordial soup could generate basic biochemicals. Miller built a simple apparatus (fig. 6.3) out of sealed tubes that formed a continuous loop, with all the air removed by vacuum. A new atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide, nitrogen, methane, ammonia, and water (but no free oxygen) was placed in the evacuated tubes. Miller then put a source of heat below the “ocean” flask at the base to start the steam circulating, and in another flask he used electrodes that created sparks to simulate “lightning” as an energy source (fig. 6.3). Below the “lightning” chamber, a condenser returned the gases to liquid state, where they recirculated back to the “ocean.” This graduate student experiment (not even his original thesis topic) yielded the most startling results. Within days, the ocean became brown with new chemicals, and within a week, it was an organic-rich gunk. When Miller analyzed it, he had already produced 4 of the 20 amino acids that life uses to make proteins, plus many other organic molecules, such as cyanide (HCN) and formaldehyde (H2CO). As Knoll (2003:74) writes, “In one remarkable experiment, Miller jump-started research on life’s origins. Powered by the energy of nature, simple gas mixtures could give rise to molecules of biological relevance and complexity.” Even though amino acids are much more complex than the chemicals he started with, Miller showed they were remarkably easy to produce. Later experiments produced 12 of the 20 amino acids found in life. Another experiment with a dilute cyanide mixture produced seven amino acids. No matter how you cut it, it does not require divine intervention or even more than a few days in the lab to make the basic building blocks of life. Since Miller’s experiments, other scientists have found 74 different amino acids in meteorites (including all 20 found in living systems), so apparently organic compounds have been produced in many other places in the universe. Some scientists even speculate that the earth was “seeded” with organic compounds from space and that sparked the origin of life, although given how easily they are made here on earth, we don’t need this more complex hypothesis.

FIGURE 6.3. An apparatus like this was used by Stanley Miller and Harold Urey in 1953 to simulate the synthesis of complex organic compounds on the early earth. The system was evacuated of air, then the large flask held an “atmosphere” rich in carbon dioxide, water, nitrogen, ammonia, and methane (but no oxygen). Sparks from electrodes simulated lightning. The product of this reaction then flowed through the condenser and accumulated in the flask, which became a brew of “primordial soup.” After about a week, the clear solution had turned into a thick murky brown sludge full of newly synthesized organic compounds, including many of the amino acids necessary to build life. (Photo courtesy S. Miller)

In the 1980s and 1990s, scientists thought that ammonia and methane were not common in the early atmosphere. This does not invalidate the Urey-Miller experiment. It only makes the task of creating organic materials a bit harder. Many later experiments have been tried with atmospheric compositions lower in methane and ammonia, and they still produced the same results as the original experiment. Since that time, scientists have returned to thinking that the early earth’s atmosphere was indeed rich in methane, and probably ammonia, too, so this criticism is no longer valid (Fegley and Schaefer 2005). In fact, the presence of amino acids in many meteorites tells us that a wide variety of atmospheric conditions throughout the universe are capable of producing them, not just the original conditions of the Urey-Miller experiment. But the creationists like Wells only want to focus on old outdated objections to experiments that may or may not be representative of current thinking. As we shall see throughout this book, creationists ignore more recent results if they can criticize outdated results and appear to invalidate a whole field of study.

So the initial building blocks are incredibly easy to produce, and it’s a fair assumption that the earth’s oceans had plenty of amino acids and other simple organic molecules floating around. The next step is a bit more difficult: assemble the simple building blocks of life into longer-chain molecules, or polymers. Amino acids link up to form longer polymers we know as proteins, which are the fundamental components of most living systems (fig. 6.4A). Simple fatty acids plus alcohols link up to form lipids, the “oils” and “fats” so common on earth. Simple sugars like glucose and sucrose link together to form complex carbohydrates and starches (fig. 6.4B). Finally, the nucleotide bases (plus phosphates and sugars) link up to form nucleic acids, the genetic code of organisms, known as RNA and DNA (fig. 6.4C).

FIGURE 6.4. The next step in the origin of life is arranging the smaller building blocks into longer, more complex chains (polymerization). The common reactions include linking together a number of amino acids to form proteins, the basic building blocks of life; polymerizing simple sugars into complex carbohydrates, the basic component of cell walls and also a critical energy source in metabolism; and linking together sugars, phosphates, and nucleosides to make nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), the basic genetic code of all life. (Modified from Schopf 1999: fig. 4.12)

There are lots of ways of approaching this complex problem of linking simple molecules into polymers like proteins, lipids, starches, and nucleic acids. Using the primordial soup approach has produced some successes. In the 1950s, Sidney Fox showed that splashing amino acids on hot dry volcanic rocks produced most of the proteins found in life instantly. In the presence of formaldehyde, certain sugars readily form complex carbohydrates. Some of Stanley Miller’s early experiments produced the components of nucleic acids, such as the nucleotide base adenine (by heating aqueous solutions of cyanide) and adenine and guanine (by bombarding dilute hydrogen cyanide with ultraviolet radiation).

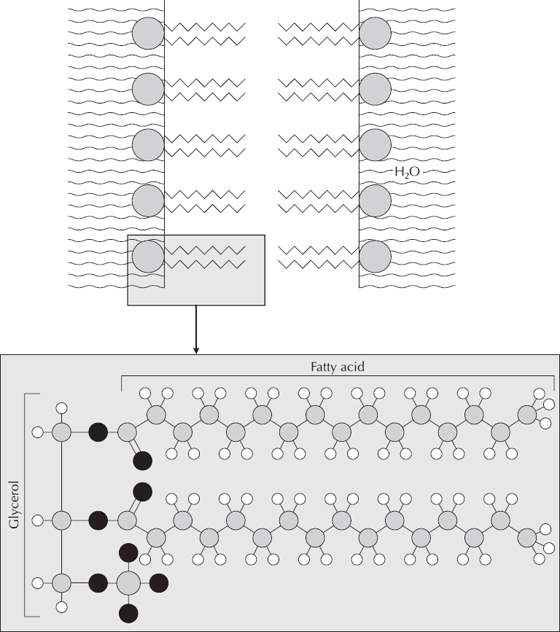

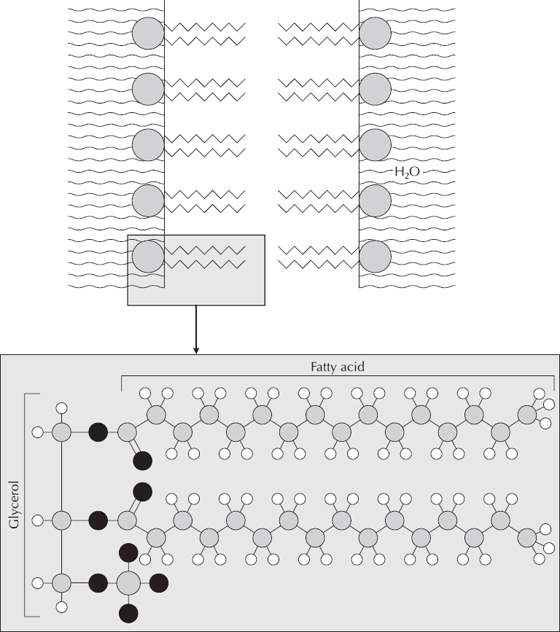

It is even easier to polymerize lipids. We all know that “oil and water don’t mix,” but most people don’t know why this is so. Fatty acids are polar molecules, with a “head” end that is naturally attracted to water and a “tail” end that is repelled by water (fig. 6.5). As soon as fatty acids are mixed with water, the individual molecules naturally line up with their heads facing the water and their tails pointed away. These then clump together to form an oil droplet (lipid in excess water) or a water droplet in oil. Once these droplets form, they have an automatic outer membrane of fatty acids that link together to form a lipid. In fact, the cell wall of most simple cells is composed of the same kind of lipid bilayer. When these lipid droplets are dried and then rehydrated, they form spherical balls that also concentrate any DNA present up to 100 times. Thus, little lipid bilayer droplets with nucleic acids trapped inside have all the properties of “protolife.” In fact, Sidney Fox produced just such structures that he called proteinoids, and Oparin produced droplets he called coacervates. These structures behave much like living cells, holding together when conditions change, growing, and budding spontaneously into daughter droplets. They selectively absorb and release certain compounds in a process similar to bacterial feeding and excretion of waste products. Some even metabolize starch! Even though they are not living, they have most of the properties of living cells—all without much more than simple chemical reactions plus heat.

FIGURE 6.5. Some organic chemicals have properties that enable cells to form naturally without complex organic reactions. Lipids, the building blocks of fats and oils, have an end that repels water and an end that bonds to water. The properties that repel or attract lipids to water naturally line them up and then combine them to form membranes. Whenever oil mixes with water, it forms a natural membrane that encloses a droplet, comparable to the lipid bilayer membrane that surrounds all cells.

Their bacterial plight was pathetic

It’s hard to be unsympathetic

Volcanic heat diminished

Organic soup finished

Their solution was photosynthetic

—Richard Cowen, History of Life

For origin of life research, the biggest challenge is how to assemble longer and more complex polymers, especially the long proteins that are so important for life. Most of the primordial soup chemical experiments have produced only shorter proteins. But a number of scientists have suggested that we’ve been going about it in the wrong way. Mixing chemicals randomly in a beaker will only link things together so much. For a longer, more complex polymer, you need a “scaffold” or “template,” some other material that will attract and line up all the organic molecules in the same direction until they are closely packed like dancers in the mosh pit in a hot nightclub. Once they are all lined up facing the same way (toward the stage) and closely packed, it is easy to link them up side by side and make complex organic polymers—just like the dense mass of people on the dance floor can easily link up and form a solid carpet of arms who can pass bodies above them.

There are many possibilities for natural substances that could produce just such a template for organic molecules. The best-known candidates are the minerals known as zeolites, which are complex silicate minerals typically formed by the breakdown of volcanic glass in hot gas bubbles left in lava. Zeolites have a complex, repetitious mineral structure that helps them catalyze organic reactions and make these reactions go much faster. In fact, they are heavily used in industrial settings for just that purpose, especially in petroleum refining, in filtration, and in absorbing chemicals (hence their use in kitty litter). All it would take is a few zeolites in a primordial soup, and the amino acids could be lined up into much more complex proteins.

An even more daring idea was posed by Alexander Graham Cairns-Smith, who suggested a template more humble than zeolites: common clay. Just as God supposedly created Adam and Eve out of clay, Cairns-Smith argues that the complex open-layered structures of clay minerals (which are sheet silicates, like micas) are ideal for absorbing organic molecules and lining them up along the clay mineral structure. The basic sheet structure of clay minerals is repeated again and again, with small imperfections in the crystals, comparable to mutations in the genetic code. In fact, Cairns-Smith takes the idea one step further. He argues that life began as clay minerals that copied themselves over and over again (with the mutations) during the crystallization process. Clays can grow, modify their environment, and replicate in a very low-tech version of life. Cairns-Smith then argues that the high-tech nucleic acids that had been lined up along these replicating clay “life forms” then underwent a genetic takeover event, and organic “replicators” replaced silicate-based replicators.

Naturally, these highly speculative ideas are very controversial but not impossible given what we know about the chemistry of clays and organic molecules. But there is one more possible template to consider: the mineral pyrite, or iron sulfide, FeS2, better known as “fool’s gold.” Gunter Wächtershäuser has shown that pyrite crystals have a positive charge on the surface that could attract the negatively charged ends of many organic molecules. Once they are attracted, lined up, and packed close to one another, the organic molecules could easily link together to form complex polymers. Once linked together, they could unzip from the pyrite template and float as free biochemicals.

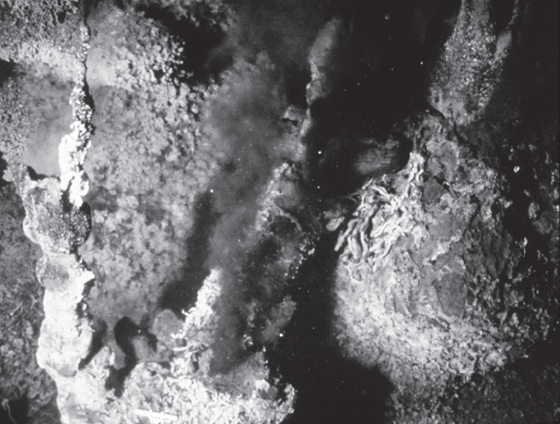

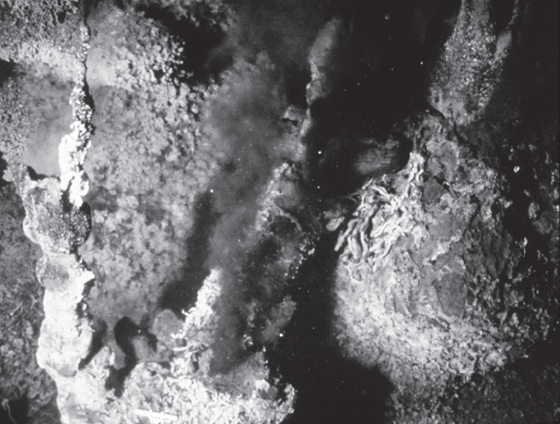

The strength of this suggestion is that it fits another astonishing scientific discovery: the “black smokers” at the bottom of the sea (fig. 6.6). In 1977, scientists using small submarines floated over the midocean ridges on the deep seafloor, where seafloor spreading takes place and new oceanic crust is generated. They were astonished to find places where the volcanic heat was superheating the seawater and producing submarine hot springs, with jets of near-boiling water shooting upward through chimneys (known as “black smokers”) composed of pyrite, calcium sulfate, lead sulfide, and zinc sulfide. Living in this hot, dark environment is a dense population of sulfide-reducing bacteria, some of the most primitive life forms on earth, which take hydrogen sulfide (H2S, which produces the “rotten egg” smell) and metabolize it, using it instead of water as the source of their hydrogen. These bacteria thus use chemosynthesis to power life because there is no light and therefore no possibility of photosynthesis or plant life (in contrast to most other environments on earth). Feeding on this bacterial population was a huge community of bizarre animals never seen before, including gigantic clams, huge tube worms, weird crabs, and some animals that were entirely new to science. I vividly remember working in the lab as a graduate student at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Cape Cod in the summer of 1978 and attending a presentation of these remarkable discoveries given by the very scientists who had just left the submarine. This amazing chemosynthetic community is totally different from the plant-based photosynthetic ecologies elsewhere on earth. The most important clue is that it is inhabited by the most primitive life forms known on earth, the sulfide-reducing Archaebacteria (fig. 5.6). To many scientists, this suggests that the simplest forms of life arose not on the surface in Darwin’s “warm little pond,” but in a deep-sea hot spring, where they would have been protected if impacts vaporized the shallow oceans.

FIGURE 6.6. In the deep volcanic rift valleys of midocean ridges, fresh lava erupts as the oceanic crust pulls apart. The hot magma heats the seawater percolating through it to superheated temperatures, forming plumes of boiling water and dissolved minerals known as “black smokers.” The main precipitate of this reaction is pyrite (iron sulfide, or “fool’s gold”), which is also a good template for bonding together complex organic materials. Consistent with the hypothesis that life originated in deep-sea vents, biologists have found that the genetically simplest forms of life, the Archaebacteria, are common in the black smokers. These are the base of a food chain that includes a huge community of giant clams, tube worms, crabs, and many other unique creatures found only in these dark submarine communities. Since there is no light at this depth, this entire system relies not on photosynthesis, but on chemosynthesis, with sulfur-reducing bacteria (rather than plants) at the base of the food chain. (Photo courtesy NOAA)

But there is one other issue that has been widely argued among scientists working on the origins of life: What was the first genetic material? Today, the information for reproduction and making more copies of living organisms is encoded in the nucleic acids, RNA or DNA, of each cell. The nucleic acids then code for certain strings of proteins, which are the stuff of life. But nucleic acids are far more complex and difficult to produce than are proteins, which we saw are among the easiest long-chain biomolecules to generate. Protein biochemists like Sidney Fox have long advocated that it would be easier for the first self-replicating organism to make its genetic code out of readily available protein chains (which still execute the commands of the nucleic acids today). At some later point in time, more complex nucleic acids were produced that eventually hijacked the system of replication from one protein to its descendants.

On the other hand, many scientists have suggested that this is a highly unparsimonious and implausible hypothesis: build a genetic code of proteins first, then replace it with another more complex one. Instead, they argue, it makes more sense to evolve the genetic code in nucleic acids from the very beginning, even if nucleic acids are harder to produce in chemical reactions than are proteins. Thus, we have a classic “chicken or the egg” problem. Which came first: the protein replication system or the nucleic acid replication system?

Fortunately, there is a way to resolve this conundrum. In 1968, DNA co-discoverer Francis Crick first suggested that the earliest protocell was a strand of RNA. In the early 1980s Tom Cech and other scientists discovered certain types of RNA, known as ribozymes, that perform multiple functions. It was such a momentous discovery that they won the 1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for it. These molecules act not only as a genetic code, but also catalyze reactions and bond together proteins. In fact, the functional part of the ribosome in the cell, which translates the RNA into proteins, is a ribozyme. Thus, ribozymes perform not only their familiar role as replicators, but also the role that proteins play. Further research led to the idea that the simplest scenario for the origin of living, self-replicating systems would be an “RNA world” (a term first proposed by Walter Gilbert in 1986, but Francis Crick, Leslie Orgel, Carl Woese, and others first argued that it was plausible back in the late 1960s). The very first self-replicating form of life would be a single-stranded RNA, perhaps enclosed in a lipid bilayer membrane, and perhaps using simple carbohydrates for food storage. Using both its replication powers and enzymatic powers, it would make more copies of itself and perform the role of the proteins as well until later more complex reactions involving many different proteins could evolve.

Every year, more discoveries are made that add details to our understanding of the origin of life and the RNA world. For example, coding sequences of amino acids are easily built on small RNA templates in normal prebiotic conditions (Lehmann et al. 2009). Experiments show that the first ribozymes in RNA world were much longer and more stable (Santos et al. 2004; Kun et al. 2005). Other experiments have shown that nucleotides easily merge in water to form RNA over 100 nucleotides long (Costanza et al. 2009). Pino et al. (2008) demonstrated that RNA molecules link up into long chains easily under normal earth conditions. And finally, a range of experiments have shown that new genes have been produced repeatedly by evolution (Long 2001; Long et al. 2003; Patthy 2003).

The “RNA world” hypothesis is now accepted as the most likely scenario for the origin of the first self-replicating system that can be truly called “life,” although there are still additional conundrums that are being worked on: How did the RNA world get replaced by the DNA world of today? And what preceded the RNA world? Could it have been (as some suggest) a PNA world (peptide-nucleic acid) system that had amino acids in the nucleic acid chains instead of the sugar ribose? Or something else? Like any good scientific problem, the solution of one mystery then leads to additional new and more interesting problems to solve. This is how science should operate.

What scientists don’t do is point to a complex system, say they can’t imagine how it could have arisen by natural causes, and throw up their hands in surrender as creationists do. Instead of claiming the origin of life is impossible to solve, and falling back on untestable, unscientific, god of the gaps arguments, scientists have made enormous progress showing how life must have arisen. We may never watch life evolve from non-life in a test tube (although we are coming close), but we certainly have good experimental evidence about how nearly all the steps took place, so the problem does not require any supernatural intervention or other cop-out to solve.

We are symbionts on a symbiotic planet, and if we care to, we can find symbiosis everywhere. Physical contact is a nonnegotiable requisite for many differing forms of life.

—Lynn Margulis, Symbiotic Planet

Creationists love to point to the complexity of the eukaryotic cell (fig. 6.7), with all its diverse organelles (such as mitochondria, chloroplasts, flagella, and so on), and try to persuade their nonscientific audiences that evolution could never construct such an amazing arrangement. What they don’t mention is that the solution to how to make a complex eukaryotic cell has been known for decades and that it doesn’t require anything more complex than living together in peace and harmony. If we were to try to take a simple prokaryote like a bacterium and develop all the organelles from scratch within it, such a task would seem improbably difficult. But in 1967, Lynn Margulis proposed a radical idea that solved the problem (independently and unknowingly reviving an obscure older idea suggested by K. S. Merezhkovsky in 1905) and gave us a much simpler solution: endosymbiosis. Instead of “inventing” mitochondria and chloroplasts and the rest from scratch, Margulis argued that these organelles were originally independent prokaryotic cells that came to live within the walls of a larger cell in exchange for food or protection (fig. 6.8). Chloroplasts apparently started out as cyanobacteria, which are photosynthetic even though they are prokaryotes without organelles. Purple nonsulfur bacteria have much the same structure and function as mitochondria, and apparently that’s where these organelles came from. The flagellum has the identical 9 + 2 fiber structure (nine sets of microtubule doublets surrounding a pair of single microtubules in the center) as the prokaryotes known as spirochetes, which cause syphilis. As each of these smaller prokaryotes came to live within a larger cell, they sublimated their functions to that of their host, so that the cyanobacteria became chloroplasts that are now homes for photosynthesis, and the purple nonsulfur bacteria became mitochondria and performed the role of the energy converter for the cell.

FIGURE 6.7. Prokaryotes, such as the Archaebacteria and true bacteria, are small cells only a few microns in diameter. Their genetic material (DNA) is not enclosed within a nucleus but floats within the cell, and they lack organelles. Eukaryotes (all other living organisms) have larger, more complex cells, with discrete nuclei containing their DNA. They also may have a number of other organelles, including mitochondria, chloroplasts, Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, cilia, flagella, and other subcellular structures.

FIGURE 6.8. According to Lynn Margulis, complex eukaryotic cells arose from two or more prokaryotic cells that combined to live symbiotically. Cyanobacteria are apparently the precursors of the photosynthetic chloroplasts, which provide photosynthesis in plant cells. Purple nonsulfur bacteria have the same structure and genetic code of the mitochondria, which provide energy in the cell. And the flagellum has the same structure as the prokaryotes known as spirochetes, which are also responsible for causing syphilis.

In addition to the detailed similarities of these prokaryotes to the organelles, Margulis pointed to many other suggestive lines of evidence. Organelles are not usually enclosed within the eukaryotic cell membrane but separated from the rest of the cell by their own membranes, strongly suggesting that they are foreign bodies that have been partially incorporated within a larger cell. Mitochondria and chloroplasts also make proteins with their own set of biochemical pathways, which are different from those used by the rest of the cell. Chloroplasts and mitochondria are also susceptible to antibiotics like streptomycin and tetracycline, which are good at killing bacteria and other prokaryotes, but the antibiotics have no effect on the rest of the cell. Even more surprising, mitochondria and chloroplasts can multiply only by dividing into daughter cells like prokaryotes and thus have their own independent reproductive mechanisms; they are not made by the cytoplasm of the cell. If a cell loses its mitochondria or chloroplasts, it cannot make more.

When Margulis’s startling ideas were first proposed 50 years ago, they were met with much resistance. But as biologists began to see more and more examples of symbiosis in nature, the notion became more plausible. We humans have many symbiotic bacteria living in and on us. Our intestines are full of the bacterium Escherischia coli (E. coli for short), familiar from petri dishes and those news alerts about sewage spills or contaminated kitchens. These bacteria actually do most of our digestion for us, breaking down food into nutrients in exchange for a home in our guts. Most of our fecal matter is actually made of the dead bacterial tissues after digestion, plus indigestible fiber and other material that we cannot metabolize. There are many other examples of endosymbiosis in nature. Termites, sea turtles, cattle, goats, and many other organisms have specialized gut bacteria that help break down indigestible cellulose so these animals can eat plant matter wholesale. Tropical corals, large foraminifera, and giant clams all house algae in their tissues that produce oxygen and help secrete the minerals for their large skeletons.

The strongest evidence came when people started studying the organelles more closely and found that not only did they have the right structure to have once been independent prokaryotic cells, but they also have their own genetic code! Mitochondria and chloroplasts both have their own DNA, which has a different sequence than the DNA in the cell nucleus. This would make absolutely no sense unless mitochondria and chloroplasts had once been free-living prokaryotes that reproduced independently. In fact, the mitochondrial DNA is different enough and evolves at a different rate from nuclear DNA, so it can be used to solve problems of evolution that the nuclear DNA cannot. This evidence would make no sense if the eukaryotic cell had tried to generate the organelles from scratch (they would not have a genetic code if that were true), and certainly it makes no sense in a creationist explanation of the cell as having been created the way we see it. If so, then why did God give the organelles their own DNA as if they had once been free-living prokaryotes? The creationists may fall back on Gosse’s Omphalos idea again, but that’s not science.

The final clincher is that we have many living transitional forms that show that this process is occurring right now! The simpler eukaryotes, such as the freshwater amoebae Pelomyxa and Giardia (famous for causing dysentery in hikers who drink contaminated water), lack mitochondria but contain symbiotic bacteria that perform the same respiratory function. In the laboratory, scientists have observed amoebae that have incorporated certain bacteria in their tissues as endosymbionts. The parabasalids, which live in the guts of termites, use spirochetes for a motility organ instead of a flagellum. Thus, from the wild speculation of 1967, Margulis’s idea is now accepted as the best possible explanation of the origin of eukaryotes and organelles. Lynn Margulis has even received the National Medal of Science for her groundbreaking and daringly original ideas.

One final point: Margulis showed that the eukaryotic flagellum was derived from the syphilis-causing spirochete prokaryotes. It so happens that the flagellum is one of the ID creationists’ (e.g., Behe 1996) favorite examples of “irreducible complexity.” Behe argues that the structure of the flagellum is too complex to explain by evolution. Apparently, he is completely unaware that this distinctive 9 + 2 structure of the flagellum already exists in nature in the structure of the prokaryotic spirochete, a much simpler life form than the eukaryotic cell. As Miller (2004) has shown, even the biochemical processes are the same. The basal body of the flagellum has been found to be similar to the type III secretion system, which many bacteria use to secrete toxins. This example of co-option is regarded as strong evidence against Behe’s example of “irreducible complexity.”

In what manner the mental powers were first developed in the lowest organisms, is as hopeless as how life itself first originated. These are problems for the distant future, if they are ever to be solved by man.

—Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

As this quote shows, even Darwin was reluctant to speculate in print about the origin of life (although he did so privately in his letter to Hooker). The evidence of evolution from the fossil record since life originated is very clear (as the next few chapters shall show), but scientists must speculate and use chemical and physical experiments to try to reconstruct the origin of life. Nonetheless, we have seen that scientists have made enormous strides in the past seven decades, from the first Urey-Miller experiment to the many abiotic syntheses of amino acids; to the many mechanisms that allow us to assemble complex polymers of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids from simpler components using templates like zeolites, clay, or pyrite; to Margulis’s endosymbiotic origins of the eukaryotic cell. Not every problem has been solved or every answer revealed, but the research on the origins of life is a relatively young, healthy field of science with much more to learn and much more to do. Given the progress that has been made so far, we seem to be close to having many of the steps in the origin of life nailed down scientifically.

Yet you would never know this from the creationist literature. The creationists view the origin of life as a weak spot in evolutionary theory and love to attack it because it is complicated and difficult to discuss or defend in a debate format. They know that most of their readers have no science background, are impressed and baffled by all that talk of cells and biochemistry, and are easily persuaded to believe simplistic arguments about stuff they don’t intuitively understand. Typically, creationists wow the audience with a presentation on the complexity of the cell and its many biochemical mechanisms and challenge the evolutionist to assemble this fantastically complex system by chance.

As many others have shown, there are many simple clear-cut answers to this challenge. First of all, we have just run through the steps that show us how to gradually build life from the simplest chemicals to amino acids to proteins and other polymers to prokaryotic cells to eukaryotic cells, all using relatively small steps that could be driven by natural selection. None of the steps require extraordinary conditions, and none are outside the realm of plausibility. In most cases, each step can either be simulated in the lab or seen in examples of the process (such as endosymbiosis) still working in nature today. Second, no evolutionary biologist says that this all arose by chance. As we discussed in chapter 2, chance may supply the raw material of variation on which selection acts, but selection is definitely a nonrandom agent (the “monkey with the word processor” analogy we used earlier). Creationists will point to some complex biochemical pathway and claim that it is “irreducibly complex” and cannot be built by natural selection. But many biochemists have torn these arguments apart because nearly every biochemical process or pathway exists in multiple forms from simple to complex, and it is easy to show that just by adding on a few steps here and there, you can start with a simple pathway (which is still adaptive) and improve it until it is as complex as the Krebs cycle. Finally, creationists invoke the fallacy of pointing to a finished product and arguing after the fact that the odds needed to produce this structure are astronomical. As we already discussed in chapter 2, you can never argue the probability of something after the fact because almost every event is extremely improbable if we start with the initial conditions and build forward—and yet these “extremely improbable” events have happened!

If the reader still feels uncomfortable with the speculative nature of the research into the origins of life, we can put the whole issue aside for now. Whether or not you agree that we can explain life’s origins by naturalistic methods, the fact that life has evolved since its origins is not subject to dispute but proven beyond a reasonable doubt by an amazing convergence of evidence from the fossil record, molecules, and the embryology and anatomy of organisms. We will focus on that evidence in the remaining chapters.

For Further Reading

Cairns-Smith, A. G. 1985. Seven Clues to the Origin of Life. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cone, J. 1991. Fire Under the Sea: The Discovery of the Most Extraordinary Environment on Earth—Volcanic Hot Springs on the Ocean Floor. New York: Morrow.

Costanza, G., S. Pino, F. Ciciriello, and E. Di Mauro. 2009. Generation of long RNA chains in water. Journal of Biological Chemistry 284:33206–33216.

Fry, I. 2000. The Emergence of Life on Earth: A Historical and Scientific Overview. Piscataway, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Hazen, R. M. 2005. Gen-e-sis: The Scientific Quest for Life’s Origins. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry.

Knoll, A. H. 2003. Life on a Young Planet: The First Three Billion Years of Evolution on Earth. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Kun, A., M. Santos, and E. Szathmary, E. 2005. Real ribozymes suggest a relaxed error threshold. Nature Genetics 37:1008–1011.

Lehmann, J., M. Cibils, and A. Libchaber. 2009. Emergence of a code in the polymerization of amino acids along RNA templates. PLoS ONE 4: e5773.

Long, M. 2001. Evolution of novel genes. Current Opinions in Genetics and Development. 11:673–680.

Long, M., E. Betran, K. Thornton, and W. Wang. 2003. The origin of new genes: glimpses from the young and old. Nature Review of Genetics 4:865–875.

Margulis, L. 1981. Symbiosis in Cell Evolution. San Francisco: Freeman.

Margulis, L. 1982. Early animal evolution: emerging view from comparative biology and geology. Science 284:2129–2137.

Margulis, L. 2000. Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution. New York: Basic.

Miller, K. 2004. The flagellum unspun: the collapse of “irreducible complexity.” In Debating Design: From Darwin to DNA, ed. M. Ruse and W. Dembski. New York: Cambridge University Press, 81–97.

Miller, Stanley L. 1953. A production of amino acids under possible primitive earth conditions. Science 117:528–529.

Nutman, A. P., V. C. Bennett, C. R. L. Friend, M. J. van Kranendonk, and A. R. Chivas. 2016. Rapid emergence of life shown by 3700-million-year-old microbial structures. Nature 537:535–538.

Patthy, L. 2003. Modular assembly of genes and the evolution of new functions. Genetica 118:217–231.

Pino, S., F. Ciciriello, G. Costanzo, and E. Di Mauro, E. 2008. Nonenzymatic RNA ligation in water. Journal of Biological Chemistry 283:36494–36503.

Schidlowski, M., P. W. U. Appel, R. Eichmann and C. E. Junge. 1979. Carbon isotope geochemistry of the 3.7 × 109 yr old Isua sediments, West Greenland; implications for the Archaean carbon and oxygen cycles. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 43:189–200.

Schopf, J. W. 1999. Cradle of Life. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Schopf, J. W. 2002. Life’s Origin: The Beginnings of Biological Evolution. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Shapiro, R. 1986. Origins, A Skeptic’s Guide to the Creation of Life on Earth. New York: Summit.

Wächtershäuser, G. 2006. From volcanic origins of chemoautotrophic life to Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 361:1787–1806.

Wächtershäuser, G. 2008. Origin of life: life as we don’t know it. Science 289:1307–1308.

Wills, C., and J. Bada. 2000. The Spark of Life: Darwin and the Primeval Soup. New York: Perseus.