These bits of information from ancient times, which have to do with themes that have supported human life, built civilizations, and informed religions over the millennia, have to do with deep inner problems, inner mysteries, inner thresholds of passage, and if you don’t know what the guide-signs are along the way, you have to work it out for yourself.

—Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth

Nearly every culture on earth has some form of a creation story or myth that it uses to explain its place in the universe and its relationships to its god or gods. As Joseph Campbell wrote in The Power of Myth (1988), these stories are essential for a culture to understand itself and its role in the cosmos and for individuals to know what their gods and their culture expect of them. At one time, myths served the role of explaining how the world came to be, usually with the subtext that it explained how that culture fit within the universe. In our modern technological scientific age, we tend to scoff at the stories that were believed by the Sumerians, Norse, and Greeks, but in their time, those stories served both as a metaphor and allegory for humanity’s place in the universe and a rational explanation for how things came to be.

Many creation stories have common elements or themes that are universal across cultures and time. They often have elements of birth or eggs in them, because these are very powerful symbols of the creation of life in our world. In some versions of the Japanese creation myths, a jumbled mass of elements appeared in the shape of an egg, and later in the story, Izanami gives birth to the gods. In the beginning of one of the Greek myths, the bird Nyx lays an egg that hatches into Eros, the god of love. The shell pieces become Gaia and Uranus. In Iroquois legend, Sky Woman fell from a floating island in the sky because she was pregnant and her husband pushed her out. After she landed, she gave birth to the physical world. There are many Hindu creation stories. In one of them, the god Brahma created the primal waters as the womb for a small seed, which grew into a golden egg. Brahma split it apart and made the heavens from one half and the earth and all its creatures from the other. The Chinook Indians of the Pacific Northwest were created out of a great egg laid by the Thunderbird. Similar stories of a cosmic egg are known from Chinese, Finnish, Persian, and Samoan mythology.

Many stories often have mother and father figures who are responsible for the creation. The mother figure is often some form of “Mother Earth,” and her fertility is symbolic of the earth’s fertility. The Greek creation myths, for example, have the world arising from the mating of the earth goddess Gaia with the sky god Uranus, and their union created the pantheon of Greek gods, who in turn created the physical universe. In Japan, Izanagi and Izanami mated, and the mother goddess Izanami gave birth to three children, Amaterasu, the sun; Tsukiyumi, the moon; and Susano-o, their unruly son. The Australian aborigines believed in the Sun-Mother who created all the animals, plants, and bodies of water at the suggestion of the Father of All Spirits. Primordial parents are found in the myths of many other cultures, including the Egyptians, Cook Islanders, Tahitians, and the Luiseño and Zuni Indians.

Most creation myths, such as the Hebrew, Greek, and Japanese myths mentioned earlier, as well as the Sumerian-Babylonian myths discussed later, have some form of chaos or nothingness at the beginning that is organized or separated into sky and earth by their gods. Other myths, however, imagine a world that existed before our present world, and one of their gods from the earlier world brings our universe into existence. The Bushmen of Africa, for example, imagined a world where people and animals lived together in peace and harmony. Then the Great Master and Lord of All Life, Kaang, planned a wondrous land above theirs and planted a great tree that spread over it. At the base of the tree, he dug a hole and brought the people and animals up from below. In the Hopi myth, there were past worlds beneath ours. When life became unbearable in those worlds, the people and animals climbed up the pine trees to reach new, unspoiled worlds where they could live. This ladder is endless, so some creatures may still be climbing out of this world and into the next. The Navajo creation myth is similar, but instead of climbing pine trees from one world to the next, they climb through a great hollow reed.

The theme of humans breaking some sort of divine edict from the gods and causing pain and suffering by their disobedience is also common. In addition to Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden story, there is the Greek story of Pandora, who was given to Epimetheus as a gift from Zeus, along with a box she was not allowed to open. But Zeus also gave her curiosity, so when she did open the box, she released all the sins and troubles of the world. The African Bushmen were told by their gods not to build fire, and when they disobeyed, their peaceful relationships with animals were destroyed forever. According to the Australian Aborigines, the Sun-Mother created the animals, which she demanded must live peacefully together. But envy overcame them, and they began to quarrel. She came back to earth and gave them a chance to change into any shape they wanted, resulting in the strange combination of animals in Australia. But because the animals had disobeyed the Sun-Mother’s instructions, she created two humans who would rule over the animals and dominate them.

The theme of a great flood that destroys nearly all of life is common to nearly all mythologies. In addition to the Sumerian story of Ziusudra and Babylonian story of Utnapishtim (described later) and the Hebrew legend of Noah (probably derived from the Sumerian or Babylonian account), the Greeks talked of Deucalion, who survived the great flood and seeded the land with the humans after the floodwaters receded. There are similar flood legends in Norse, Celtic, Indian, Aztec, Chinese, Mayan, Assyrian, Hopi, Romanian, African, Japanese, and Egyptian mythology. Scholars suggest that this may be because most cultures that live near large bodies of water (which nearly all do, except those in the mountains) have experienced some catastrophic flood in their distant past. It also wiped out much of their culture and tradition, so that flood achieves legendary status when its story is told generation after generation. Only a few cultures or religions, including the Jainists of India and the Confucianists of China, have no creation myth whatsoever.

This brief thematic summary does not do justice to the details and the imagery of the original myths or to the power of the language in which they were written. If you have never done so, I strongly recommend that you pick up a book of comparative mythology or examine some of the many texts that are now available on the Internet. Through all this discussion, we have seen how mythologies often reflect universal themes about human existence and about how humans fit into the universe. None of these stories is necessarily “true” or “false”—they are products of their own cultures and were essential to those people for giving their world a context. All humans hunger for an understanding of their origins, so they generate some sort of story to explain those origins. Once that story has been passed from generation to generation, it acquires its own sort of reality or “truth,” and it is important to the members of that culture so that they understand their own role in the world and their relationship to their gods.

As Michael Shermer (1997:30) sums it up, “Does all this mean that the biblical creation and re-creation stories are false? To even ask the question is to miss the point of the myths, as Joseph Campbell (1949, 1982) spent a lifetime making clear. These flood myths have deeper meanings tied to re-creation and renewal. Myths are not about truth. Myths are about the human struggle to deal with the great passages of time and life—birth, death, marriage, the transitions from childhood to adulthood to old age. They meet a need in the psychological or spiritual nature of humans that has absolutely nothing to do with science. To turn a myth into science, or science into a myth, is an insult to myths, an insult to religion, and an insult to science. In attempting to do this, the creationists have missed the significance, meaning and sublime nature of myths. They took a beautiful story of creation and re-creation and ruined it.”

When on high heaven was not named,

And the earth beneath did not yet bear a name,

And the primeval Apsu, who begat them,

And chaos, Tiamat, the mother of them both

Their waters were mingled together,

And no field was formed, no marsh was to be seen;

When of the gods none had been called into being,

And none bore a name, and no destinies were ordained;

Then were created the gods in the midst of heaven,

Lahmu and Lahamu were called into being…

Ages increased…

—Enuma Elish, about 3000 B.C.E.

The origin of the Hebrew creation stories in the Bible has been studied for nearly 200 years and is well known and accepted by most Bible scholars. In the 1860s and 1870s, archeologists excavated several ancient Sumerian cities in Mesopotamia (what is now Iraq) and found clay tablets written in cuneiform. This is the oldest written language on earth, created with marks in soft clay made by a wedge-shaped stylus. Some of the stories date back at least to 4000 B.C.E., and most were recycled by the mythology of the Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian cultures that replaced the Sumerians in Mesopotamia. The longest and best known of these stories is the Enuma Elish (in Babylonian, the first two words of the story, translated “When on high…”), which describes a creation epic that bears remarkable similarity to Genesis 1, including a formless void and chaos, with gods dividing the waters from the land and naming the creatures. Since the story predates any of the Hebrew creation stories by centuries, there is little doubt that the early Hebrews were influenced by this powerful epic accepted by all Mesopotamian civilizations for over two millennia. Psalm 74 also borrows heavily from the Enuma Elish, where Yahweh destroys the Leviathan and splits its head open in an almost word-for-word copy of the way in which Marduk, the chief god of Babylon, splits open the head of Tiamat, the goddess of the ocean.

Another source is The Epic of Gilgamesh, which dates to about 2750 B.C.E. The Sumerians had a hero called Ziusudra (called Atrahasis by the Akkadians and Utnapishtim by the Babylonians), who is warned by the earth goddess Ea to build a boat because the god Ellil was tired of the noise and trouble of humanity and planned to wipe them out with a flood. When the floodwaters receded, the boat was grounded on the mountain of Nisir. After Ziusudra’s boat was stuck for seven days, he released a dove, which found no resting place and returned. He then released a swallow that also returned, but the raven that was released the next day did not return. Ziusudra then sacrificed to Ea on the top of Mount Nisir. The story is nearly identical to that of Noah’s flood, not only in its plot and structure, but also in the details of its phrasing. Only the names of the characters and gods and a few details have been changed to suit the differences between the monotheistic Hebrew culture and the polytheistic cultures of the Sumerians, Akkadians, and Babylonians.

Two centuries of detailed study by scholars has also revealed the way in which the Bible was put together. In its original Hebrew, the Old Testament (especially the first five books, or Pentateuch) show unmistakable signs of different authors writing different parts, and then someone later patching the whole thing together. Someone reading a later translation (especially the outdated King James translation) cannot pick up these differences easily, but they are obvious to those who read Hebrew. In high school, I was troubled by the contradictions between what I learned in my Presbyterian Sunday School and what I had learned from science; I decided to find out about the Bible myself. Not only did I read many books about biblical scholarship, but I also learned to read Hebrew so I could decipher Genesis on my own, making my own judgment about translations. In college, I also learned ancient Greek, and I can still read the New Testament in the original text and recognize when someone is mistranslating or misinterpreting the original.

To Hebrew scholars, the most obvious signs of different authorship are their choices of certain phrases and words, especially the word they use for God. One source is known as the “J” source, after Jahveh, a common name for God. This name is also spelled and pronounced “Yahweh” or “YHWH” for those who dare not speak God’s name (since early written Hebrew had no vowels or even the modern system of vowel points, only the consonants are used). This name was mispronounced and misspelled as “Jehovah” by later authors. The authors of the J document were priests of the southern kingdom of Judah, who wrote sometime between 848 B.C.E. and the Assyrian destruction of Israel in 722 B.C.E. They use terms such as “Sinai,” “Canaanites,” and phrases such as “find favor in the sight of,” “call on the name of,” and “bring out from the land of Egypt.” The J authors were probably religious leaders associated with Solomon’s temple, very concerned with delineating the guiding hand of Jahweh in their history but not so concerned with the miraculous.

The second main source is known as the “E” document, after their name for God, Elohim, “powerful ones” in Hebrew. The priests who composed the E document were interested in different issues, used a different set of phrases, and can be traced to the northern kingdom of Israel, sometime between 922 B.C.E. and the Assyrian conquest in 722 B.C.E. The E authors use such terms as “Horeb” instead of Sinai, “Amorites” instead of Canaanites, and the phrase “bring up from the land of Egypt.” Most scholars think that the E authors were Ephraimite priests, who were more interested in the righteousness that God requires of his people. When people sinned they must repent. Moses is the central focus of these accounts, along with miraculous aspects of their history.

A third source, the “P” source, or Priestly Code, was apparently written by Aaronid priests around the time of the Babylonian captivity in 587 B.C.E. It is the youngest of the sources of the Old Testament. The P source emphasizes the role of Aaron and diminishes the role of Moses in the early books of the Bible. This source frequently uses long lists and is characterized by long boring interruptions to the narrative and cold unemotional descriptions. To Hebrew scholars, the P source is also distinctive in its low, clumsy, inelegant literary style. The P source views God as distant and transcendental, acting and communicating only through the priesthood. According to P, God is just but also unmerciful, using brutal, abrupt punishment when laws are broken.

Sometime during the reign of King Josiah around 622 B.C.E., the Hebrews began combining these different traditions along with other sources (such as the “D” source of the Deuteronomic code). All of these documents date from the period before Judah was captured, Jerusalem burned, the Temple destroyed, and the Hebrews dragged off to captivity by Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon in 587 B.C.E.

Verse by verse, scholars can tease apart the way in which each book of the Old Testament was woven together (see Friedman 1987 or Pelikan 2005). As a result, the Bible is full of internal contradictions that make it impossible for anyone who reads it closely to take it literally, but only makes sense in the context of different sources being blended together. For example, Genesis 1 (largely from the P source) gives the order of creation as plants, animals, man, and woman, but Genesis 2 (from the J source) gives it as man, plants, animals, and woman. According to Genesis 1:3–5, on the first day, God created light, then separated light and darkness, but according to Genesis 1:14–19, the sun (which separates night and day) wasn’t created until the fourth day. Genesis 6–7 gives the story of Noah twice, once from the J source and once from the P source, with verses from the two sources intermingled so that they sometimes contradict each other. Genesis 6:5–8 are from the J source, but Genesis 6:9–22 are from the P source. Then Genesis 7:1–5 are from the J source, and Genesis 7:6–24 are alternately from the J and P sources every other line or so (Friedman 1987:54). This leads to many contradictions, such as Genesis 7:2 (from the J source), saying that Noah took seven pairs of each clean beast in the ark, but Genesis 7:8–15 (from the P source), saying he took only one pair of each beast in the ark. In Genesis 7:7, Noah and his family finally enter the ark, and then in Genesis 7:13 they enter it all over again (the first verse from the J source, the second from the P source). According to Genesis 6:4, there were Nephilim (giants) on the earth before the Flood, then Genesis 7:21 says that all creatures other than Noah’s family and those on the ark were annihilated—but Numbers 13:33 says there were Nephilim after the Flood.

Many more examples could be cited, but the basic point is clear: the Bible is a composite of multiple sources that did not always agree on details. This was no problem to the ancient Hebrew culture, which used the Bible for inspiration but was not concerned with literal consistency. It is a big problem for modern fundamentalists (most of whom have never read the Bible in the original Hebrew or Greek, so they are in no position to argue) who believe that every word of the Bible is literally true. Most nonfundamentalist Christians, Catholics, Jews, and Muslims have accepted what scholarship has shown us about the origin of the Bible and use it as a book for understanding their relationship to their God but not as a science textbook or literal account of history. As Joseph Campbell and many other later authors have pointed out, these religious stories are important to believers for their meaning and symbolism and connection to the inner mysteries of life, not as detailed literal accounts of events. Only in our modern scientific age, with its obsession with literalism and detail, have fundamentalists made such a gross error about the spirit and meaning of the Scriptures (see papers in Frye 1983).

It not infrequently happens that something about the earth, about the sky, about other elements of this world, about the motion and rotation or even the magnitude and distances of the stars, about definite eclipses of the sun and moon, about the passage of years and seasons, about the nature of animals, of fruits, of stones, and of other such things, may be known with the greatest certainty by reasoning or by experience, even by one who is not a Christian. It is too disgraceful and ruinous, though, and greatly to be avoided, that he [the non-Christian] should hear a Christian speaking so idiotically on these matters, and as if in accord with Christian writings, that he might say that he could scarcely keep from laughing when he saw how totally in error they are. In view of this and in keeping it in mind constantly while dealing with the book of Genesis, I have, insofar as I was able, explained in detail and set forth for consideration the meanings of obscure passages, taking care not to affirm rashly some one meaning to the prejudice of another and perhaps better explanation.

—Saint Augustine, The Literal Interpretation of Genesis 1:19–20

The United States is home to a unique and peculiar form of religious extremism known as creationism. As a movement, it has almost no following in Canada, Europe, Asia, or most of the rest of the world, but in America it has had a long influence on science education and public understanding of evolution (fig. 2.1). As a result, most Americans still don’t understand or accept the evidence of evolution.

FIGURE 2.1. The “intelligent design” movement is simply a disguise for creationism to sneak into public schools and avoid the constitutional separation of church and state. (Cartoon by Steve Benson, copyright © Creators Syndicate)

Ironically, the creationist movement is not only a uniquely American phenomenon, but it is also the latest form of backlash against the inevitable forces of change and modernity. For most of the past 2,000 years, people did not question the literal accounts of creation in the first books of Genesis. Even as early as 426 C.E., however, the great Christian philosopher Saint Augustine wrote that the Genesis account of creation was an allegory and should not be interpreted literally, as adherence to a literal reading of Genesis might discredit the faith.

As more and more scientific discoveries were made, some of the literalistic readings of the Bible had to be rethought. Once people accepted that the spherical earth revolved around the sun, it was no longer plausible to think that Joshua had made the sun stand still, that the earth was flat, or that it was the center of the universe, as described in the Bible. By the mid-1700s, enough facts about nature had accumulated that many educated people doubted the literal accounts of the Bible. During the French Enlightenment of the mid-1700s, writers such as Denis Diderot, Voltaire, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau rejected the Roman Catholic Church’s dogma, and in 1749, the great naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, the count of Buffon, even speculated that the earth was 75,000 years old, that life evolved, and that humans and apes were closely related.

By the early 1800s, the idea that Genesis was a literal account of earth’s history was widely questioned by educated people, especially in England, France, and Germany. As a backlash to this widespread skepticism, a number of ministers and naturalists tried to write accounts that reconciled nature with the Bible (the Bridgewater Treatises) or tried to use the apparent design and perfection in nature as evidence of a divine designer (natural theology). But literal belief in Genesis was already widely discredited long before Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859.

Darwin, of course, changed the terms of the debate entirely, polarizing the Western world into those accepting evolution and those rejecting it. At first, the argument was intense, as the shock of Darwin’s ideas began to sink in, but by the time Darwin died in 1882, the fact that life had evolved was no longer controversial in any European scientific or intellectual community. Darwin’s ideas had become so respectable when he died that he was buried with honors in the Scientists’ Corner of Westminster Abbey, right next to Isaac Newton and other famous British scientists.

Most American scholars and scientists also came to terms with Darwin by the 1880s or created their own form of compromise between their own religious beliefs and the idea that life had evolved. For example, in 1880, the editor of one American religious weekly estimated that “perhaps a quarter, perhaps a half of the educated ministers in our leading Evangelical denominations” believed “that the story of the creation and the fall of man, told in Genesis, is no more the record of actual occurrences than is the parable of the Prodigal Son” (Numbers 1992:3). At the same time, a skeptical analytical approach known as “higher criticism” was being applied to the Bible itself, and scholars (especially in Germany) were able to show by careful analysis of the original texts and their language that the Old Testament is a composite of several schools of thought in Hebrew history, not the words of Moses and the Prophets.

Higher criticism alarmed the devout biblical literalists even more than Darwinism and evolution, so in 1878, ministers met in the First Niagara Bible Conference. Beginning in 1895 and concluding by 1910, they had published 90 pamphlets that were known as The Fundamentals of their faith (hence the term “fundamentalist”). Most of The Fundamentals concerned the miracles of Jesus, his virgin birth, his bodily resurrection, his death on the cross to atone for our sins, and finally, that the Bible is the directly inspired word of God. Fundamentalism was largely a reaction to the higher criticism of the Bible, and its early proponents were not quite as strongly against evolution, because evolution was already widely accepted not only by scientists but also by most ministers. A. C. Dixon, the first editor of The Fundamentals, wrote that he felt “a repugnance to the idea that an ape or an orangoutang was my ancestor” but was willing “to accept the humiliating fact, if proved” (Numbers 1992:39). Reuben A. Torrey, who edited the last two volumes of The Fundamentals, acknowledged “for purely scientific reasons” that a man could “believe thoroughly in the absolute infallibility of the Bible and still be an evolutionist of a certain type” (Numbers 1991:39). Although the early fundamentalists were not happy with evolution, they were willing to live with it; they were not as stridently opposed to the idea as they would be a generation later. More importantly, evolution was accepted by most of the science textbooks of the time, so even if the parents were fundamentalists who rejected evolution, their children accepted it. Even in the conservative Baptist South, evolution was taught without much resistance in many educational institutions (Numbers 1992:40).

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.

—First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

“Creation science”…is simply not science.

—Judge William Overton, McLean vs. Arkansas

The first two decades of the twentieth century were a time of global turmoil, with the progressive politics of Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, the bloodshed of World War I, and the great influenza epidemic of 1918. Then came the Roaring Twenties and a national conservative backlash. It was also a “return to normalcy” as Warren Harding promised when he won the presidency in 1920. With the conservative backlash came Prohibition. This did nothing to stop alcohol consumption in the United States, but it did make profitable careers for gangsters and moonshiners and the owners of illegal speakeasies. Another conservative movement, however, was the backlash against evolution by the resurgent fundamentalist movement. The movement was led by William Jennings Bryan, one of the most popular and powerful political figures in the United States, who had run for president on the Democratic ticket three times and lost. By the 1920s, however, Bryan was in his sixties, in failing health, and beginning to promote conservative causes that were becoming popular in the 1920s. Bryan campaigned vigorously for laws to outlaw the teaching of evolution. By the end of the 1920s, more than 20 states had debated such laws, and five (Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Florida) had banned or curtailed the teaching of evolution in their public schools. It went so far that the U.S. Senate debated, but never passed, a resolution that banned radio broadcasts favorable to evolution.

Ironically, Bryan himself was not a biblical literalist. He confided to a friend shortly before his death that he had no objection to evolution, as long as it didn’t include man (Numbers 1992:43). He was also less than literal about the meaning of Genesis 1, subscribing to the common “day-age” theory that each “day” in Genesis 1 was actually a long period of geologic time, or “age.” Nevertheless, he became the national spokesman for a witch hunt that hounded many biologists out of their jobs in Southern universities and destroyed the careers of many other scientists.

The climax of the creationist movement in the 1920s was the infamous Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925, long called the “trial of the century” until the O. J. Simpson trial eclipsed it in notoriety. Not only was it a titanic struggle between two of the giants of the time, Bryan and the legendary defense attorney Clarence Darrow, but it was also one of the first trials to be covered live on radio and in newsreels, beginning the modern trend toward celebrity trial journalism. Among the press covering the trial was none other than the famous satirist and essayist H. L. Mencken, who wrote many savage columns and editorials for the Baltimore Sun, ridiculing the biblical literalism and backward habits and racism of the South.

The trial itself was originally planned as a publicity stunt by the town fathers of Dayton, Tennessee. Anxious to rake in tourist dollars, garner attention, and provide a test case to challenge the recently passed Tennessee Butler Act, or “monkey laws,” that banned the teaching of evolution, the civic leaders recruited a local high school teacher, John T. Scopes, to be their guinea pig. Scopes volunteered to take time off from teaching gym to teach biology for one day so that he could test the law, although later he admitted that he wasn’t sure he had actually taught anything about evolution. He did, however, use the classic textbook, Hunter’s Civic Biology, which mentioned evolution prominently. Once the trial was underway, Darrow’s defense plans collapsed because Judge John T. Raulston would not allow the testimony of any of the expert scientific witnesses whom Darrow had brought. The judge ruled that the case only concerned whether Scopes had broken the law, and witnesses challenging the law itself were irrelevant. In desperation, Darrow turned this defeat into one of the greatest legal tours de force in history. He baited Bryan into taking the stand as an expert witness on the Bible. Under a blistering cross-examination (vividly portrayed in the famous play and movie Inherit the Wind), Darrow got Bryan to admit to many of the logical absurdities of a literalistic interpretation of the Bible. Bryan could not explain how Joshua had gotten the sun (and therefore the earth) to stand still or where Cain had gotten his wife (when there were only supposed to be four people on earth, Adam and Eve and Cain and Abel), or the many other problems with a literal interpretation of the Bible. Even more devastating, Bryan admitted under oath that the “days” of Genesis were not 24-hour days but could be long geologic “ages,” a revelation that shocked most of his fundamentalist followers. Soon, fundamentalism and the monkey law itself were subject to ridicule. Bryan died a week after the trial, which occurred during a torrid heat wave and aggravated his already failing health. More importantly, the fundamentalist monkey laws had taken a bad beating in the press and in the public eye, and most Americans were embarrassed that our nation had been portrayed as so scientifically backward.

The trial itself, however, was inconclusive. The judge mistakenly levied a $100 fine on Scopes that was supposed to be levied by the jury, so his verdict was thrown out on this technicality. As a result, it was not possible to take the case to higher courts and have a verdict examined on appeal. Scopes never had to pay the judge’s fine. Eventually, Scopes went to college and became a successful oil geologist. Meanwhile, the Tennessee monkey law stayed on the books for decades and was not declared unconstitutional until 1968. In that year, Susan Epperson, a young biology teacher in Arkansas, got her case heard before the Supreme Court, who then struck down all laws forbidding the teaching of evolution—43 years after the Scopes trial!

By 1929 the Great Depression had changed the mood of the country, and creationism was no longer in the forefront. Fundamentalists were more concerned about issues like sex education, and no further legal cases challenging the monkey laws were filed, although the old laws remained on the books. Instead, the fundamentalists focused their attention on making sure evolution vanished from the biology textbooks, which it did shortly after the Scopes trial (due to pressure by a few determined creationists on textbook publishers and on local school boards). Creationism and evolution existed in an uneasy truce until the Soviets shook America with the launch of Sputnik in 1957. Then Americans were shocked to discover how far behind our science and technology had fallen, and by 1958, the Republican Congress and Eisenhower administration had begun pouring big money into scientific research and science education. Science also became more and more respected by the American public, especially after the technological advances of World War II, the atomic bomb, and eventually the space race. Federal funding from scientific research went from 0.02 percent of the gross national product during the Hoover administration (1929–1933) to 1.5 percent of the GNP by 1960. With this new emphasis on science came biology textbooks that reflected the new ideas in evolution represented by the neo-Darwinian synthesis of the 1940s and 1950s (see chapter 4). The new generation of science textbook authors was not as cowed by creationist pressure to dilute or eliminate coverage of evolution when the nation was facing a crisis in science education, in large part caused by the lackadaisical coverage of science in public schools.

The newly Darwinized biology textbooks roused the creationists from their inactivity. In 1961, John C. Whitcomb and Henry M. Morris published The Genesis Flood, which represented a whole new approach of creationists to not only discredit evolution but also geology (see chapter 3). By 1963, they had founded the Creation Research Society near San Diego, followed by the Institute for Creation Research (ICR), which was the main base of operations for fundamentalist creationists until its founders and leaders all died, and it was eclipsed by other groups and faded into irrelevance. Through their books, debate appearances, and public speeches, they raised awareness of their literalist views to a new level, although they had no impact on the community of science yet.

Creationists, however, still faced one major hurdle: the Constitution and the legal system. By 1968, the Supreme Court had struck down all the old anti-evolutionary “monkey laws,” and the creationists no longer had the backing of conservative legislatures as they had in the 1920s. Because they could no longer legally exclude evolution from the classroom, they tried a tactic of demanding equal time for their ideas. However, in court case after court case, they were turned back, because their ideas were clearly religious in origin, with no scientific content, and the Constitution prohibits the government from establishing a state religion or favoring one religion over another. Led by fundamentalist lawyer Wendell Bird, the creationists changed tactics yet again. They began calling their ideas “scientific creationism” and claimed that their ideas were as scientific as evolution and deserved equal time in science classes. Of course, this is simply “bait and switch,” because the creationist literature is full of references to God and the Bible. They even published two editions of the same textbook, one of which was labeled “Public School Edition” and deleted the overt references to God and Bible, but otherwise the text was the same.

Their main spokesmen seemed to be talking out of both sides of their mouths. In public, they argued that “creation science” is good science, but when speaking to a religious audience, they let their fundamentalist beliefs show. For example, Henry Morris (1972: preface) writes, “Creation, on the other hand, is a scientific theory which does fit all the facts of true science, as well as God’s revelation in the Holy Scriptures.” On page 58 of the same book, he writes “we conclude that special creation theory is the best theory, strictly on the scientific merits of the case.” Yet the ICR’s principal debater and spokesman, Duane Gish, wrote (1973:40) “we cannot discover by scientific investigations anything about the creative processes used by the Creator,” and “creation is, of course, unproven and unprovable by the methods of experimental science. Neither can it qualify as a scientific theory” (8).

The climax came when Arkansas and Louisiana passed bills that mandated “equal time” for creationism in science classes, and these laws were promptly challenged in federal court. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), challenging the Arkansas law, put not only distinguished scientists and philosophers of science on the witness stand, but also a group of ministers and theologians, and parents of children in the school district. In fact, the lead plaintiff challenging the law was a minister, the Reverend Bill McLean of Little Rock. The witnesses showed example after example of how there was no difference between “creation science” and religion, and how the nature of science forbids any belief system that twists the facts to fit its preexisting conclusions. The creationist case was further hampered by the fact that they had no credible scientific witnesses to bring to the stand. One of their star witnesses, the maverick British astrophysicist N. Chandra Wickramasinghe, openly scoffed at the idea of creation science. On January 5, 1982, Judge William R. Overton gave his ruling on McLean vs. Arkansas Board of Education. Judge Overton saw through the thin disguise of creation science and ruled that the Arkansas law “was simply and purely an effort to introduce the Biblical version of creation into the public school curricula.” According to Overton, the law “left no doubt that the major effect of the Act is the advancement of particular religious beliefs.” The law that required balanced treatment “lacks legitimate educational value because ‘creation science’ as defined in that section is simply not science.” In 1985, Federal Judge Adrian Duplantier ruled in a summary judgment (thus not requiring even a trial or witnesses) that Louisiana’s equal time law was also unconstitutional. In the 1987 Edwards vs. Aguillard case, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 7–2 vote, upheld the decisions of the lower courts, and the creationists lost their last legal battle in this round.

For about ten years, the creationists stayed away from the courts and stopped trying to force their way into education by legal means. Instead, they focused their energies on school boards and textbook publishers. Every week, those of us in the front lines of the creationism battle heard news of another school district that was under pressure to teach creationism or put anti-evolutionary stickers in biology textbooks. Most of these battles were eventually decided against the creationists, but they are a determined and well-funded minority that has nothing but time, energy, and money to push their cause, while most scientists are too busy doing legitimate research to pay attention to the problem.

The evidence, so far at least and laws of Nature aside, does not require a Designer. Maybe there is one hiding, maddeningly unwilling to be revealed. But amid much elegance and precision, the details of life and the Universe also exhibit haphazard, jury-rigged arrangements and much poor planning. What shall we make of this: an edifice abandoned early in construction by the architect?

—Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot

The label “scientific creationist” was seen as a fraud by Judges Overton and Duplantier and by the Supreme Court. So the creationists resorted to a new strategy: “intelligent design” (commonly abbreviated ID). In order to find a way to make their ideas constitutional and legal, they had to try to eliminate any signs of religion from their dogmas, not simply dress up biblical ideas as “scientific creationism.” In the 1990s, a new generation of creationists came up with a different strategy that focused on the apparent “design” in nature, arguing that it requires some sort of “intelligent designer.” Led by Berkeley lawyer Phillip Johnson, Lehigh biochemist Michael Behe, and former Baylor professor William Dembski, they published a number of books that promoted their views. They argued that nature was full of things that not only showed intelligent design but also were “irreducibly complex” and could not have evolved by chance. They pointed to a number of examples, such as the flagellum and the eye, which they believed could not be explained by chance events or by gradual evolution.

In most ways, their arguments are recycled from over two centuries ago, when many devout naturalists ascribed to the school of thought known as “natural theology.” (Ministers were often naturalists back then because they had lots of time for studying nature as evidence of God’s handiwork, and there were no professional scientists.) The most famous advocate of natural theology was the Reverend William Paley, who in 1802 wrote Natural Theology, the classic treatment of the subject. His most famous metaphor is the “watchmaker” analogy. If you were to find a watch on a beach, you would immediately recognize that it was “intricately contrived” and infer that it had a maker. To Paley, the “intricate contrivances” of nature were evidence that there was a Divine Watchmaker, namely God.

In its day, the natural theology school of thought was very influential, and Darwin himself knew Paley’s book almost by heart. Yet the basic arguments had been discredited even before the time of Paley. In 1779, the Scottish philosopher David Hume published Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, which demolished the whole argument from design. Using dialogues between characters to voice different points of view, Hume puts the standard natural theology arguments in the mouth of a character called Cleanthes, then he tears them down in the words of a skeptic named Philo. Philo notes that pointing to the design in nature is a faulty analogy, because we have no standard to compare our world to, and it is possible to imagine a world much better designed than the one in which we live. Even if we concede that the world looks designed, it does not follow that the designer is the Judaeo-Christian God. It could have been the god of another religion or culture, or the work of a committee of gods, or a juvenile god who makes mistakes. Jews and Christians simply assumed that if there was a Designer, it must be their God, but there is no compelling evidence to show that it wasn’t some other god.

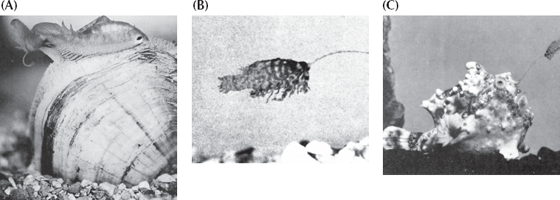

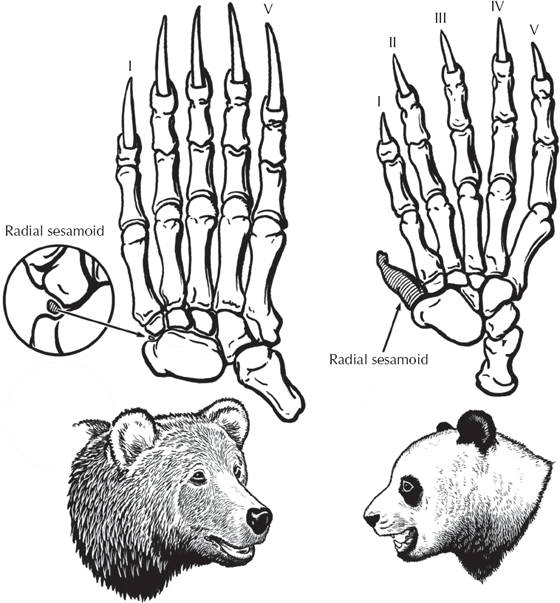

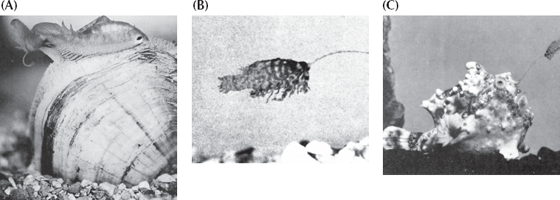

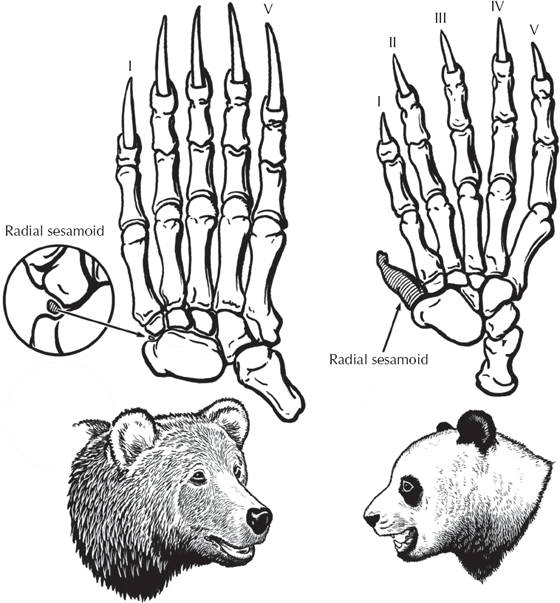

More importantly, evidence was already in existence in Hume’s and Paley’s times that did not reflect well on the Divine Designer. For all the examples of beauty or symmetry in nature, one could also point to many examples where nature is poorly designed or jury-rigged so that it just barely works, or where nature shows astonishing cruelty that does not reflect a caring, compassionate God. Stephen Jay Gould pointed to examples such as Lampsilis (fig. 2.2A), the freshwater clam that sticks a brood sac full of eggs out of its shell that looks vaguely like a fish. It’s not a very good fishing lure, but it’s good enough to get fish to bite it and transfer the eggs to their gills, where they are passed on to another generation. Similarly, the anglerfish (fig. 2.2B and C) has a crude fringe on the tip of a spine above its eyes that looks vaguely fishlike, and when flicked around, is just good enough to lure prey close enough to be gulped down. Again, it’s not a very good facsimile of a fish, but it’s good enough to lure prey within reach. Gould’s favorite example is the panda’s “thumb” (fig. 2.3). Pandas, like most cats, dogs, bears, and members of the order Carnivora, have all five fingers united in a paw, yet pandas are almost the only carnivore that eats plants (bamboo). Consequently, pandas have modified a wristbone, the radial sesamoid, into a crude thumb-like device, which is not jointed and not very flexible or strong, but just strong enough to allow pandas to strip off the leaves from the bamboo as they eat. Once again, a clumsy, poorly designed jury-rigged device—good enough to allow the survival of pandas (although we’re now driving them to extinction due to habitat destruction in China), but evidence of a very clumsy designer at best.

FIGURE 2.2. Nature is full of examples of jury-rigged adaptations that work just well enough to serve a purpose but are not perfectly designed. (A) The freshwater clam Lampsilis has a brood pouch that looks somewhat like a fish and lures fish to bite it. When they do, the clam’s larvae then hook onto the fish’s gills and complete their life cycle. (Photograph by J. H. Welsh, from the cover of Science magazine, v. 134, no. 3472, 1969; copyright ©1969 American Association for the Advancement of Science. Reprinted with permission.) (B and C) The anglerfish has a spine above its mouth with a fringed tip that looks vaguely fishlike. When prey comes near to bite the lure, the anglerfish sucks its victim into its mouth. (Photos from Pietsch and Grobecker, Science 201:369–370, 1978; copyright ©1978 American Association for the Advancement of Science. Reprinted with permission.)

FIGURE 2.3. The panda, like all Carnivora, has all five fingers forming a paw, but unlike other Carnivora, it eats bamboo. Consequently, it has modified a wristbone, the radial sesamoid, into a crude “thumb” that enables it to strip the leaves off bamboo. It works just well enough to feed a panda; it is not beautifully designed, but crude, clumsy, and jury-rigged. (Drawing by Carl Buell)

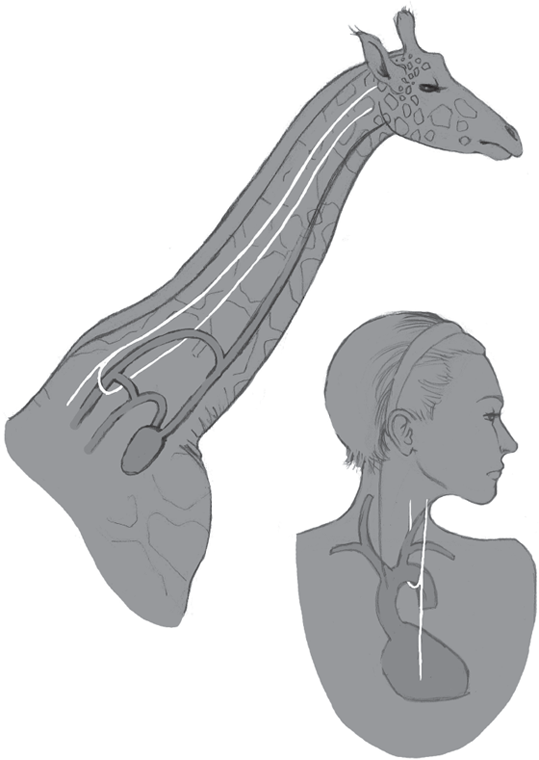

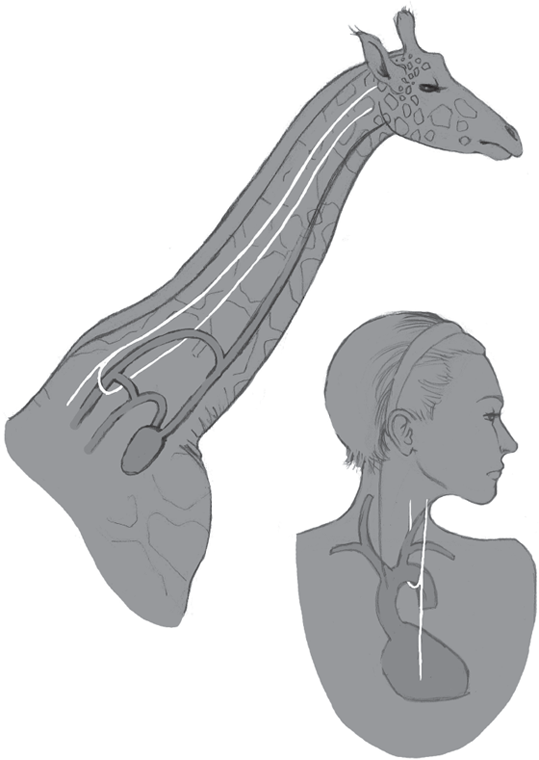

Examples of poor or at least very puzzling design can be accumulated endlessly. Many cave-dwelling fish and salamanders have the rudiments of eyes but are completely blind. If God specially created these creatures to live in totally dark caves, why bother to give them nonfunctional eyes in the first place? Even more peculiar is the course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which connects the brain to the larynx and allows us to speak. In mammals, this nerve avoids the direct route between brain and throat and instead descends into the chest, loops around the aorta near the heart, then returns to the larynx (fig. 2.4). That makes it seven times longer than it needs to be! For an animal like the giraffe, it traverses the entire neck twice, so it is 15 feet long (15 feet of which are unnecessary!). Not only is this design wasteful, but it also makes an animal more susceptible to injury. Of course, the bizarre pathway of this nerve makes perfect sense in evolutionary terms. In fish and early mammal embryos, the precursor of the recurrent laryngeal nerve attached to the sixth gill arch, deep in the neck and body region. Fish still retain this pattern, but during later human embryology, the gill arches are modified into the tissues of our throat region and pharynx. Parts of the old fishlike circulatory system were rearranged, so the aorta (also part of the sixth gill arch) moved back into the chest, taking the recurrent laryngeal nerve (looped around it) backward as well.

FIGURE 2.4. The recurrent laryngeal nerve branches from the spinal cord and sends nerve impulses to the vocal cords, as well as to other parts of the esophagus (digestive tube) and trachea (breathing tube). During embryology, it is associated with the front part of the gills in a fish, so it loops over the aorta, the artery that supplies most of the blood to be pumped by your heart. But fish don’t have necks, so this pathway is short. In fish, it travels from the brain past the heart to the gills. For humans, this same nerve must loop from the spinal column at the base of the head, down through the neck and to the heart, where it still loops around the aorta, then back up through the neck to reach the throat, where it controls your voice box. In a giraffe, the nerve branches out from the spinal column just below the head. It then must travel more than 7 feet down the neck, where it can loop around the aorta, and then 7 more feet back up the neck to reach the throat region and control the vocal cords and other parts of the esophagus and trachea. That’s a total of 15 feet of unnecessary length!

In fact, the more one looks at nature, the more one finds examples of clumsy or jury-rigged design because, unlike a Divine Designer, evolution does not require perfection. Any solution that ensures the survival of an organism long enough to breed is sufficient. We humans are classic examples of an organism not optimally designed to our current lifestyles. Our backs and our feet are not well adapted to walking upright, as those of us who suffer with back and foot pain know. Our knees are poorly constructed and easily damaged, as those who have had knee surgery can attest. Our eyes are designed backward, with several layers of cells and tissues blocking and distorting the light hitting the retina in the back of our eye before the light finally reaches the photoreceptor cells on the very bottom layer. We have vestigial organs, such as our tiny tailbones, tonsils, and appendix, the latter two of which no longer perform an important function but can become infected and be deadly to us. These only make sense if they were inherited from ancestors who had functioning versions of these organs. Our genome is full of nonfunctional DNA, including inactive pseudogenes that were active in our ancestors. Humans, like most primates, cannot make vitamin C and must get it from their diet. We still carry all the genes for making vitamin C but no longer use them, probably because our primate ancestors got it from their fruit-rich diets instead. Finally, ask any ID advocate: Why did God give men nonfunctional nipples?

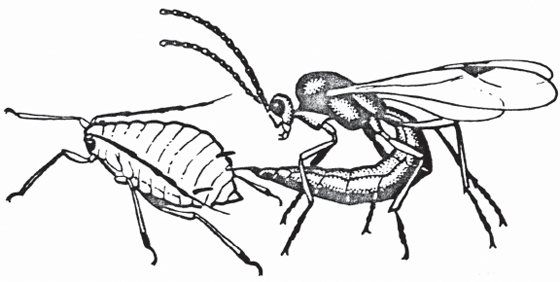

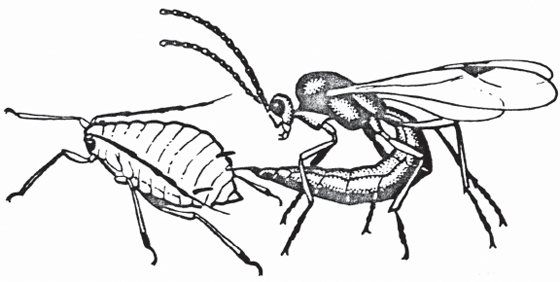

ID creationists may want to think twice before pointing to God’s handiwork as evidence of a benevolent God, because it is full of examples of not only poor or incompetent design but also outright cruelty. The most famous example is the family of wasps known as the Ichneumonidae, which consist of about 3,300 species who all reproduce in a distinctive way. The female wasp (fig. 2.5) stings a prey animal with her ovipositor and lays her eggs inside the paralyzed prey. After the eggs hatch, the larvae slowly eat the living prey animal from the inside, destroying the less essential parts first and only eating the essential parts (and killing the host) at the very end, when they are ready to hatch out of its dead shell. (Shades of the creepy extraterrestrials in the movie Alien.) The Victorians were horrified when this example became well known and were at a loss as to how to square this fact of nature with their idea of a benevolent God who looks after the tiny sparrow and cares about all of his creation. As Charles Darwin wrote,

I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created parasitic wasps with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of Caterpillars.

But that has long been a problem for those who would believe in a God who is all-knowing and all-powerful. If so, why does he allow innocents to suffer and die? Why can’t he stop great natural disasters? What about the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which killed about a quarter of a million innocent people? This is the classic “problem of pain” (theodicy) that has always tortured Christian apologetics, but many skeptics consider it good evidence against a Divine Designer who watches his handiwork closely. As Darwin himself put it (in an 1856 letter to Thomas Henry Huxley): “What a book a devil’s chaplain might write on the clumsy, wasteful, blundering low and horridly cruel works of nature!”

FIGURE 2.5. The cruelty of the reproductive habits of the ichneumonid wasps horrified the Victorians and mocked the idea of a benevolent God. The female wasp stings its prey and paralyzes it; then she inserts her eggs into the body of the living prey. The eggs then hatch into larvae, which eat the prey from the inside, consuming less essential organs first and only killing the victim at the very end—at which point, the prey’s body becomes a cocoon containing the baby wasps about to hatch.

Reading the ID creationists closely, you find that they don’t offer any new scientific ideas or a true alternative theory of life competing with evolution. All they argue is that some parts of nature seem too complex for them to imagine an evolutionary explanation. This is the classic “god of the gaps” approach: concede to science that which it has already explained but reserve to supernatural forces that which hasn’t been explained—yet. Back in the Middle Ages, people thought that God made the heavens run and the stars and planets move until Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, and Johannes Kepler showed that it could all be explained by natural laws and processes without divine intervention. So theology retreated from explaining that part of nature, and it has been retreating ever since. But nature is always full of things that we have not explained. Explaining the unexplained is the goal of science—to continue solving those unsolved mysteries, not to stop and throw up our hands and say, “Oh, well, I can’t think of an explanation now, so God must have done it.” As Michael Shermer (2005:182) points out, the ID approach is actually quite arrogant: if the ID creationists can’t think of a natural explanation, then they are asserting that no scientist can either, and the problem cannot be solved. Needless to say, giving up on hypotheses and testable explanations, shrugging our shoulders, and going home while saying “God works in mysterious ways” is not how science operates.

ID creationists actually concede that they don’t have a real alternative theory to evolution. Leading ID creationist Paul Nelson said at a meeting at Biola College in Los Angeles in 2004: “Easily the biggest challenge facing the ID community is to develop a full-fledged theory of biological design. We don’t have such a theory right now, and that’s a problem. Without a theory, it’s very hard to know where to direct your research focus. Right now, we’ve got a bag of powerful intuitions, and a handful of notions such as ‘irreducible complexity’ and ‘specified complexity’—but, as yet, no general theory of biological design.” Nor is their “research program” legitimate. During cross-examination in an ID creationism trial in Dover, Pennsylvania, Behe was forced to confess, “There are no peer-reviewed articles by anyone advocating for intelligent design supported by pertinent experiments or calculations which provide detailed rigorous accounts of how intelligent design of any biological systems occurred.” Behe also conceded that there were no peer-reviewed articles supporting some of the other claims that systems (such as the blood-clotting cascade, the immune system, and the bacterial flagellum) were irreducibly complex or intelligently designed. Their entire literature consists of books and articles published by their own supporters or for the general trade book market, where there are no scientific standards of peer review. (The one exception I’m aware of is discussed later in this chapter.)

But all this talk about intelligent design is actually a smokescreen for what is still fundamentally a religious dogma. For public consumption, the ID advocates may say that the designer need not be the Judaeo-Christian God but could also be an alien or some other supernatural entity. Dembski claims that “scientific creationism has prior religious commitments whereas intelligent design does not.” But in reality, the ID creationists are all evangelical Christians, who clearly have used intelligent design as a smokescreen (fig. 2.1) for their real agenda: get religion into science classrooms and evolution out—or weaken it, at least. In public, they try to hide these religious convictions, but when speaking to their fellow fundamentalists, they let their true colors show. In an article in the Christian magazine Touchstone, Dembski wrote, “Intelligent design is just the Logos theology of John’s Gospel restated in the idiom of information theory.” In 1999, Dembski wrote, “Any view of the sciences that leaves Christ out of the picture must be seen as fundamentally deficient…. The conceptual soundness of a scientific theory cannot be maintained apart from Christ.” On February 6, 2000, Dembski told the National Religious Broadcasters: “Intelligent Design opens the whole possibility of us being created in the image of a benevolent God…. The job of apologetics is to clear the ground, to clear obstacles that prevent people from coming to the knowledge of Christ…. And if there’s anything that I think has blocked the growth of Christ as the free reign of the Spirit and people accepting the Scripture and Jesus Christ, it is the Darwinian naturalistic view.” At the same conference, Phillip Johnson said, “Christians in the twentieth century have been playing defense. They’ve been fighting a defensive war to defend what they have, to defend as much of it as they can. It never turns the tide. What we’re trying to do is something entirely different. We’re trying to go into enemy territory, their very center, and blow up the ammunition dump. What is their ammunition dump in this metaphor? It is their version of creation.” In 1996, Johnson said, “This isn’t really, and never has been, a debate about science…. It’s about religion and philosophy.” One of the ID creationist authors, Jonathan Wells, is a follower of the Reverend Sun-Myung Moon and his Unification Church (which is vehemently anti-evolutionary). As Wells wrote, “When Father chose me (along with about a dozen other seminary graduates) to enter a Ph.D. program in 1978, I welcomed the opportunity to prepare myself for battle.”

Ironically, most ID creationists accept some microevolutionary change and conventional geology and the great age of the earth, and regard the “young-earth” literalist creationists of the ICR or Answers in Genesis as irrelevant dinosaurs, relicts of the past. In 2005, Dembski actually debated the dean of the old-guard creationists, Henry Morris, where Dembski said, “Thus, in its relation to Christianity, intelligent design should be viewed as a ground-clearing operation that gets rid of the intellectual rubbish that for generations has kept Christianity from receiving serious consideration.”

Even though the ID creationists pretend to be dispassionately following the truth, when you look closely at their internal documents, it is clear that they are waging outright warfare on science by whatever dirty tactics and PR techniques that are necessary. Brown and Alston (2007) in their book Flock of Dodos: Behind Modern Creationism, Intelligent Design, and the Easter Bunny detail some of the more dishonest activities of the Discovery Institute and print in full the infamous “Wedge Document” of the ID creationists, which details their devious political and PR strategy to force their viewpoints on the American scientific community and educational system. (Although ID creationists tried to hide it, the Wedge Document is easy to find online with a simple search. Nothing ever vanishes in cyberspace). As Brown and Alston summarize, the Discovery Institute “is willing to mischaracterize the results achieved by real scientists in order to achieve short-lived propaganda victories, and it is willing to continue to do so even after these real scientists object and even after it has apologized and promised to stop doing so. Above all, it is willing to cloak its true socio-political goals behind a consciously-crafted veil of dispassionate scientific inquiry, even while denouncing science itself. If the Discovery Institute tells a lie, it does so in order to advance the Truth. Because the Discovery Institute fights for morality, it is above morality. Indeed, the intent of the Discovery Institute is simple enough. Con men are rarely complicated” (136–137).

If the words of the ID creationists were not evidence enough, we can always heed the warning of “Deep Throat” (in All the President’s Men): “Follow the money.” The ID movement is largely based at the Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture (CRC), a part of the Discovery Institute in Seattle. The CRC receives most of its funding from right-wing evangelical and religious organizations and from rich individuals and foundations whose expressed goals are to promote evangelical Christianity. These include $750,000 from the Ahmanson Foundation, whose executor, Howard Ahmanson Jr., said that his goal was “the total integration of biblical law into our lives.” The MacClellan Foundation gave $450,000 to promote “the infallibility of the Scripture”; they give grants to organizations “committed to furthering the Kingdom of Christ.” The Stewardship Foundation gives $200,000 a year, and their goal is “to contribute to the propagation of the Christian Gospel by evangelical and missionary work.” Most of the 22 organizations funding the CRC were politically and religiously conservative, according to the New York Times. The Times also reported that the CRC received $4.1 million in 2003 and spends about $50,000 to $60,000 a year on about 50 researchers. That money buys a lot of airtime on radio and TV and provides funding for their advocates to speak and debate around the country and publish their books, get hearings at various conservative school boards—and file lawsuits promoting their ideas.

By 2005, ID creationism had reached a peak in publicity, when they made the cover of Time magazine and received the endorsement of President George W. Bush. They also got their ideas heard by the conservative Kansas State Board of Education (which endorsed them) and tried to push their ideas onto the Dover, Pennsylvania, school board (which also tried to follow them, until sued by the parents in the district). In December 2005, however, they suffered a great defeat in the case of Kitzmiller et alia vs. the Dover Area School District. Federal Judge John E. Jones III, a traditional Christian appointed by President Bush in 2002 (and not a liberal activist judge), saw through their smokescreen and ruled that ID creationism was clearly an unconstitutional establishment of a particular religion in public schools. His 139-page ruling was very thorough and detailed. Judge Jones castigated the evangelical Christian school board that rammed through the creationist curriculum and drew the lawsuit by the parents of the students. In his words, “The breathtaking inanity of the board’s decision is evident when considered against the factual backdrop which has now been fully revealed through the trial. The students, parents, and teachers of the Dover Area School District deserved better than to be dragged into this legal maelstrom, with its resulting utter waste of monetary and personal resources.” Judge Jones was particularly irritated by the hypocrisy of the ID creationists, who attempted to sound secular when the Constitution was involved, but crowed about their religious motives when not in court. “The citizens of the Dover area were poorly served by the members of the board who voted for the intelligent design policy. It is ironic that several of these individuals who so staunchly and proudly touted their religious convictions in public would time and again lie to cover their tracks and disguise the real purpose behind the intelligent design policy.” And in another passage, “We find that the secular purposes claimed by the board amount to a pretext for the board’s real purpose, which was to promote religion in the public school classroom.” Still later he wrote, “Any asserted secular purposes by the board are a sham and are merely secondary to a religious objective.”

The judge also pointed out that the ID advocates had tried to paint evolution as atheism, which was preposterous. “Both defendants and many of the leading proponents of intelligent design make a bedrock assumption which is utterly false. Their presupposition is that evolutionary theory is antithetical to a belief in the existence of a supreme being and to religion in general.” Finally, the judge was puzzled by the fact that there was no real theory behind intelligent design creationism, just criticisms of evolutionary biology and a vague god of the gaps idea. In Judge Jones’s words, “Defendants’ asserted secular purpose of improving science education is belied by the fact that most if not all of the board members who voted in favor of the biology curriculum change concealed that they still do not know, or nor have they ever known, precisely what intelligent design is.”

Brown and Alston (2007) dissect the absurdities of the Dover trial. Their first chapter gives a detailed account of the trial and uses the court transcripts and the creationists’ own words to expose their lying and dishonesty. Brown and Alston quote extensively from the confused and convoluted testimony of William Buckingham, the creationist school board chairman who openly promoted his religious motivations before trial, then lied under oath repeatedly to cover his tracks, apparently at the instructions of the lawyers from the Discovery Institute. As Brown and Alston sum it up, “To know William Buckingham is to know the millions of our fellow Americans who are ignorant not only of the theory they’d like to discredit, but also of the pseudo-theory with which they’d like to replace it; who, knowing full well that they lack the basic data to make a decision between the two, do so anyway and loudly at that; and who lie through their teeth when asked exactly what it is that motivates them to do these sorts of things in the first place. William Buckingham lied because he believed it was necessary to do so in order to preserve the truth as he saw it—that literalized Christianity is the one true religion, and that Darwinism is its greatest threat” (26).

During the course of the trial, the witnesses for ID creationism were repeatedly exposed for their bad science, and the documents that were introduced show the clear imprint of having been recycled from older creationist documents. The most striking evidence of this was the discovery of different editions of the textbook Of Pandas and People (Davis and Kenyon 2004). Early drafts were full of conventional creationism, but when a federal case struck down young-earth creationism for the final time, the authors just cut and pasted a few phrases here and there to remove the references to “God,” “creation,” and “creationism.” In one place, the plaintiffs’ legal team exposed a tell-tale palimpsest: the phrase “cdesign proponentsists,” where the phrase “design proponents” has been clumsily and incompletely pasted over the word “creationists.”

At the time of Judge Jones’s decision, analysts thought that the Dover verdict would be the death knell for future attempts by ID creationists to win victories by legal means, because in most cases courts follow precedents established by other courts (especially if they are thorough and well-reasoned). But ID creationism was extinguished even more completely than anyone could have imagined. Even though the Discovery Institute keeps pushing it, no school district has tried to adopt any ID school materials in the 11 years since the original Dover decision. Even more surprising, the entire notion of ID creationism has abruptly died from American discourse. A simple Google Trends search of terms like “intelligent design” done by Nick Matzke shows that it virtually vanished from the Internet after 2006, with almost no real discussion since then. “Intelligent design” creationism is really and truly dead.

Since the Dover decision, the Discovery Institute refused to accept this, and keeps on cranking out books and literature and propaganda. As Nick Matzke (2015) wrote:

Of course, the Discovery Institute is still around, still desperately trying to re-write history, claiming that they never supported teaching ID in public schools (when they clearly did, as even the Thomas More Law Center noted), that they never supported what the school board in Dover was doing (never mind that it was the DI’s care package of ID materials, particularly Icons of Evolution stuff, that ginned up the school board in the first place, which was exactly the intent of all of the emotional language about “fraud” etc. in Icons), that the Dover Area School Board was a bad place for a test case because of obvious religious motivations (never mind that ID is and always has been mostly a wing of apologetics for conservative evangelicals, and in fact that audience is still the only one where ID events, books, etc. have much of an audience today), and that ID isn’t creationism relabeled.

Now the Discovery Institute is trying to put on a brave face and claim that “intelligent design” is alive and well. On the tenth anniversary of the Dover decision, their site had a long post bragging about their “accomplishments” in the past ten years that is a monument to special pleading and selective misuse of facts. They mostly brag about how their lawyers have won nuisance suits against real scientists and real museums who crossed them, and about their books (mostly by Stephen Meyer, one of their leading authors), which have been roundly criticized and mostly ignored by the real scientific community for their scientific incompetence, dishonesty, and outright deception.

And what about their actual scientific research program? Back in the late 1990s when the Discovery Institute was founded, their Wedge Document proposed to get 100 scientific articles published in the next ten years. Now, almost 20 years later, their latest post touts their “80 peer-reviewed publications” as if it’s some great accomplishment. Most productive individual scientists have at least that many papers, and the Discovery Institute is a giant propaganda mill with many contributors. In fact, I have more than 300 peer-reviewed publications, almost four times their total, all by myself. Moreover, if you look through the list in the Discovery Institute post, it is almost entirely papers for their own house journal BIO-Complexity, or unreviewed online fringe sites like the Journal of Cosmology, or some other predatory online journals that will publish anything for a fee. Only one or two articles are found in reputable journals, and the titles of those articles indicate that their content isn’t really about ID at all.

Ironically, the point is largely moot in Dover, Pennsylvania, because in November 2005, the citizens of Dover (embarrassed by all the negative publicity) voted the conservatives off the school board and voted in a new school board that was opposed to teaching intelligent design in its schools. Naturally, this new school board did not wish to appeal the judge’s ruling, but applauded it—but they were still stuck with the legal bills that the folly of the old school board had generated.

Creation is, of course, unproven and unprovable by the methods of experimental science. Neither can it qualify as a scientific theory.

—Duane Gish, “Creation, Evolution, and the Historical Evidence”

Creation isn’t a theory. The fact that God created the universe is not a theory—it’s true. However, some of the details are not specifically nailed down in Scripture. Some issues—such as creation, a global Flood, and a young age for the earth—are determined by Scripture, so they are not theories. My understanding from Scripture is that the universe is in the order of 6,000 years old. Once that has been determined by Scripture, it is a starting point that we build theories upon.

—Kurt Wise, 1995

Ultimately, creationism has nothing to do with science, except that the creationists want to replace a valid scientific idea with their own religious dogmas. It is all about politics and power and promoting their cherished ideas whatever the cost. Creationists don’t do normal science, don’t publish their anti-evolutionary ideas in peer-reviewed scientific journals, don’t present their results at legitimate scientific meetings, and more importantly, don’t even begin to follow the basic precept of science: there is no final truth, and all ideas must be subject to testing and falsification. Creationists have their conclusions already determined. The ICR even makes their members swear a loyalty oath that predetermines their conclusions. No real scientist would ever do this, since in real science, the conclusions must remain tentative and subject to change. Creationists will do whatever it takes to twist and jumble and distort the evidence to support their case. Indeed, the term “creation science” is an oxymoron, a contradiction in terms, like “jumbo shrimp.” Creationists are not really doing science as long as their conclusions are predetermined and they are unwilling to test and falsify their conclusions. The quotes from Duane Gish above and cited earlier in the chapter clearly confess this.

As Shermer (1997:131) pointed out, the creationists have much in common with the neo-Nazi Jew-hating Holocaust deniers, who refuse to acknowledge that millions of Jews were killed by the Nazis. Like the creationists, Holocaust deniers pretend to be legitimate objective scholars and deny their underlying motives in public, but in private they reveal their true anti-Semitic hatred that drives them to distort and deny the truth. The principal strategy of Holocaust deniers is to find small errors in the scholarship of historians (or scientists, in the case of creationists) and imply the entire field is wrong, as if scholars never disagreed or made mistakes. Holocaust deniers often quote other people out of context (Nazis, Jews, other Holocaust scholars) to make them seem as if they are supporting the deniers’ position; creationists do the same to evolutionists’ publications. The existence of a debate over details is used by the Holocaust deniers to suggest that the Holocaust didn’t happen, or the scholars can’t get their stories straight, and creationists do the same to the legitimate scientific debate among evolutionary biologists. However, as Shermer says, the Holocaust deniers can at least be partially right in that the number of Jews killed may be revised, but the creationists cannot. Once you introduce supernaturalism to the debate, it is no longer scientific.

Because they have lost every battle in the courts, creationists resort to other tactics: pressuring school boards, intimidating textbook publishers, harassing people who oppose them, and disguising their religious motives by such flimsy ruses as intelligent design. Because their unscientific ideas could never pass peer review in scientific journals or make it into a university curriculum, they publish their own books and journals, and create their own educational institutions to reflect their dogmas. Because their ideas would not withstand the scrutiny of peer review in scientific meetings, they seldom attend real scientific meetings but preach to the choir instead.

The exceptions to these statements prove the rule. In August 2005, Stephen Meyer’s ID creationist article on the “Cambrian explosion” appeared in the obscure Journal of the Biological Society of Washington. According to reports, the peer reviews were scathing and recommended rejection of the article, but the editor, Richard Sternberg, had creationist sympathies and let it be published anyway. Once the rest of the editorial board and the Smithsonian scientists became aware of what had been slipped past them, they repudiated the article, and the editor resigned. To my knowledge, this is the only openly creationist paper that has ever appeared in a legitimate scientific peer-reviewed journal—and only because the editor was sympathetic to their cause and violated journal policy by overruling his reviewers. The other papers published by Fritz, Baumgardner, Austin, and creationist “flood geologists” don’t appear in peer-reviewed scientific journals, only in the creationists’ own publications. Any of their writings that do appear in a legitimate peer-reviewed journal concern some minor issue (such as the polystrate trees of Yellowstone or the fossil concentrations in some places), and nowhere do the authors reveal their creationist agenda in the research.

Likewise, creationists do not present their arguments at legitimate professional meetings of respected scientific societies; they use stealth tactics instead. Forrest and Gross (2004) describe the sneaky efforts of an ID creationist, Paul Chien, to organize a conference in China, ostensibly about the amazing Precambrian and Cambrian fossils that have been found there. But respected scientists, such as Dr. David Bottjer of the University of Southern California and Dr. Nigel Hughes of University of California–Riverside, arrived only to find that the meeting was funded by the Discovery Institute and full of ID creationist speakers. The whole conference was a deliberate ruse to get the papers of legitimate scientists published alongside those of creationists and to lend creationists some respectability.

Whenever they do try to engage the scientific community, creationists do so through a debate format. At first, this seems like a fair strategy, because for many fields we have a long tradition of using debate to explore evidence and clarify ideas. But in fact, the debate format does nothing to sort out the evolution/creation dispute, except to resolve who has better rhetorical and debating skills. Creationists are very skilled at this, since they do it all the time and have a lot of practice. By contrast, scientists never actually engage in a true formal debate (complete with pro and con positions, moderator, rebuttals, etc.) at scientific meetings. In addition, creationists dictate the terms of the debate by constantly attacking their evolutionist opponents with one charge after another, jumping from astronomy to thermodynamics to paleontology to biology to anthropology. This is known as the “Gish Gallop,” after Duane Gish, who was a master of this tactic. The scientists opposing the creationist debaters cannot possibly answer all of the misconceptions and distortions of complex concepts that they have introduced in the short debate format, because they can’t teach an audience the actual science as fast as the creationists can distort it. When the evolutionist debater tries to go on the offensive, the creationist quickly dodges the question and continually tries to make his or her (mostly religious) audience believe that they must believe the creationist or become an atheist. When a scientist with good debating skills (especially one with religious convictions who can’t be called an atheist) pins them down, creationists crumble, because their knowledge of scientific subjects is superficial and learned by rote, so they really don’t understand what they are talking about. But their skill in debating is such that they seldom get pinned down or rattled for very long. Most scientists won’t even bother to debate them, because it’s a no-win situation; everyone who attends the debate has already made up their minds. In addition, most scientists are poorly trained at debating, and we don’t want to treat creationists as scientific peers (they aren’t) and dignify their arguments with the pretense of a debate. Plus, we all have much better things to do, such as real scientific research. Consequently, creationists taunt scientists and claim they are afraid to defend evolution.

Stephen Jay Gould said it best,