Long, long before you and I were born, there were dinosaurs all over the earth, except in New Zealand. Dinosaurs lived and loved in the Mesozoic Era, or Age of Reptiles, which began 200,000,000 years ago and lasted until 60,000,000 years ago. (There are people who know these things. Does that satisfy you?)…. The brain of a dinosaur was only about the size of a nut, and some think that is why they became extinct. That can’t be the reason, though, for I know plenty of animals who get by with less…. The Age of Reptiles ended because it had gone on long enough and it was all a mistake in the first place.

—Will Cuppy, How to Become Extinct

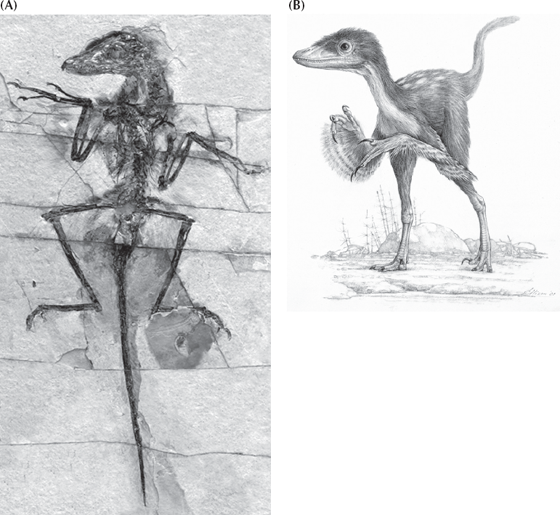

Dinosaurs are big business these days, with millions of dollars of merchandise featuring their likenesses, four of the highest-grossing movies ever made (the Jurassic Park-Jurassic World series), and dozens of documentaries on cable television. Almost every kid between ages 4 and 12 is fascinated with them. Most of the public knows or cares nothing about prehistoric life except for the dinosaurs, and many use the word “dinosaur” for any extinct beast (including prehistoric mammals and many other creatures not even remotely related to dinosaurs). Some people still have the Flintstones or the comic strip B.C. as their mental image for prehistory and believe that dinosaurs and humans coexisted. With the exception of the birds (fig. 12.1), which are dinosaurs (as we shall soon prove), all the rest of the nonbird (“nonavian”) dinosaurs were extinct by 66 million years ago, and our own family did not appear until 5–7 million years ago, so at least 58 million years separate nonbird dinosaurs and humans. Some creationists have tried to perpetuate this myth by claiming that there are human tracks mixed with dinosaur tracks in the Paluxy River bed in Texas, but that has been debunked by creationists themselves, and most of them consider it an embarrassment (Morris 1986; see Glen Kuban’s review at paleo.cc/paluxy/sor-ipub.htm).

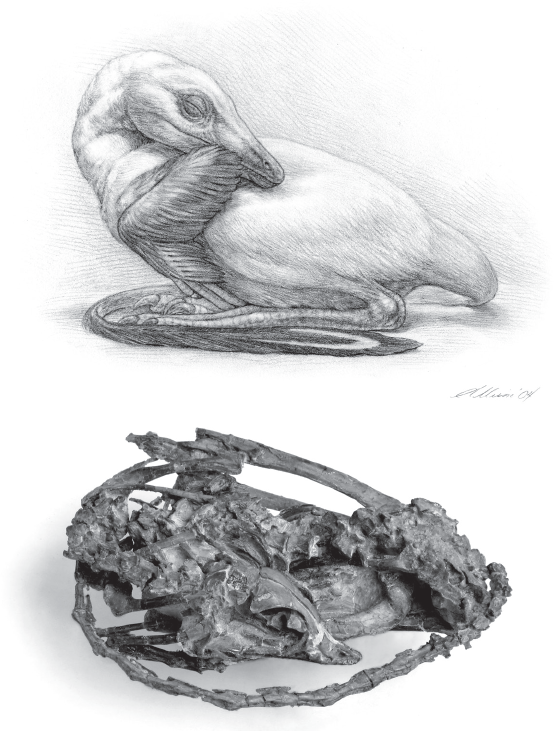

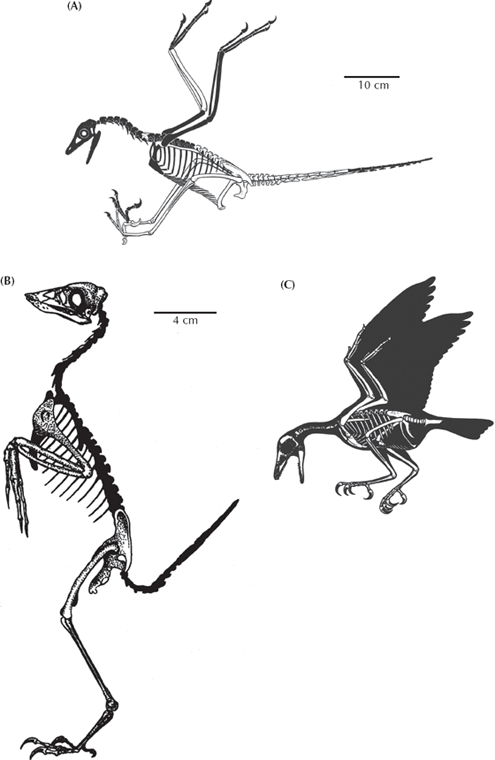

FIGURE 12.1. (A) The famous specimen known as “Dave” or more formally, Sinornithosaurus, a feathered nonflying dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Liaoning beds of China. (B) Reconstruction of Sinornithosaurus in life. (Photo and drawing courtesy M. Ellison and M. Norell, American Museum of Natural History)

Nevertheless, creationists know that the public only cares about dinosaur and human evolution, so they feel obligated to trot out examples of cool-looking dinosaurs in their books and debates and at the “Creation Museum” in Kentucky, and then claim that there are no transitional forms for any dinosaur. Not only is this a blatant lie, but it shows that they have not done the least bit of homework, for even the kiddie books about dinosaurs illustrate many transitional forms and primitive members of the major families.

Considering how rare dinosaur fossils are (especially in comparison to the marine invertebrates we discussed in chapter 8), it is remarkable that we have any transitional dinosaur fossils at all. But enough specimens are preserved to show that we now have the transitions between nearly every major group of dinosaurs, plus many other remarkable fossils that show other types of transitions, such as carnivorous dinosaurs becoming herbivorous.

Of all creatures that have ever lived, the dinosaurs are of greatest fascination to man, particularly to children. This is perhaps because of their spectacular size in many cases…. and because they possessed so many unusual anatomical features. The fossil record of dinosaurs speaks out as clearly for creation as would be possible for creatures now extinct.

—Duane Gish, Evolution: The Fossils Still Say NO!

When I debated Duane Gish at Purdue University on October 1, 1983, I had seen his presentation the week before, so I knew he would show some dinosaur slides (mostly from century-old Charles R. Knight paintings, which are grossly out of date) because his audience would find them far more interesting than “mammal-like reptiles” or “fishibians.” So I prepared my own segments (the first and third half hours of the first 2 hours of a 4-hour debate) to rebut his misleading information about dinosaurs before he even got to it. Did he change his presentation or acknowledge the fact that I had just shown the transitional forms whose existence he denied? No, like a robot he gave exactly the same slides and same lecture that he had delivered the week before, without any apparent awareness that I had blown his examples to pieces. I don’t know what he was thinking, but many of the people who came up afterward and told me that I had won the debate said that his dishonest treatment of dinosaurs convinced them.

Gish (1978, 1995) and the other creationist authors never learn, but (just like their misleading presentation of the second law of thermodynamics) they keep on plugging the same false statements about dinosaurs because dinosaurs are impressive and interesting to their audience, which cares only about dinosaurs and no other prehistoric animals. If you read through the dinosaur chapter in Gish (1995) closely, the entire argument consists of out-of-context quotations from really old, outdated books, especially popular trade books, which are highly oversimplified. Gish never bothered to read more specialized books on dinosaurs, probably because he wasn’t trained to do so and couldn’t tell one bone from another. And that raises the most important point. Gish had absolutely no qualifications to interpret dinosaur fossils or to make judgments about them. He may have tried to glean what impressions he could from reading children’s books and quoting them out of context, but he was no more qualified to make pronouncements based on such simplistic book reports than your average high school kid. (Remember, his Ph.D. was in biochemistry and completely irrelevant). More importantly, reading children’s books (rather than studying the actual specimens) is not science nor is it even true research. If Gish really cared to find out whether there were transitional dinosaur fossils or not, he would have gotten the proper training in vertebrate paleontology and gone and studied the fossils for himself. Otherwise, his statements about fossils he has never studied are just baloney.

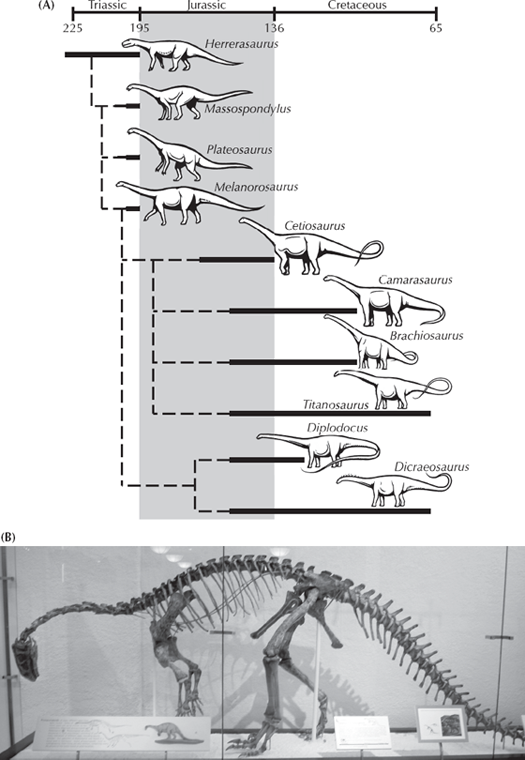

Let’s look at just a few of the many examples of dinosaurs that Gish claimed have no transitional forms. The first one he always shows is the large long-necked sauropod he called “Brontosaurus.” He apparently had not learned that paleontologists had stopped using that name decades ago; the proper name has been Apatosaurus for over a century. (Even most of the children’s books have stopped using Brontosaurus and correctly use Apatosaurus now). In our 1983 debate, he showed a few outdated slides of Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus (one of the stars of Jurassic Park), then zoomed on to his next examples, claiming that there were no transitional forms between them and other dinosaurs. He even made the same claim in his 1995 book (1995:124).

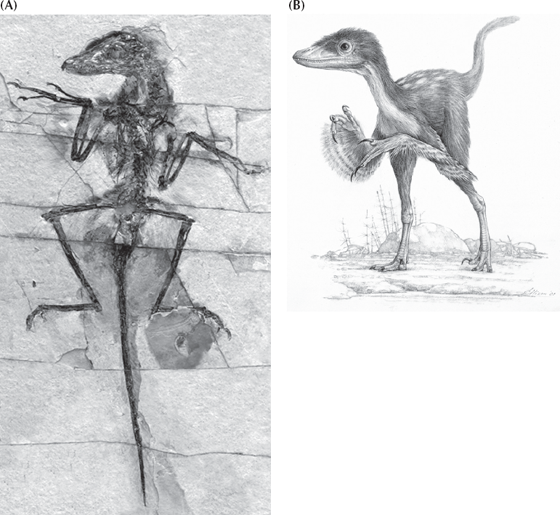

Apparently Gish never bothers to read even the children’s books closely. Nearly every book about dinosaurs illustrates a group of Triassic creatures called prosauropods, whose very name (translated as “before the sauropods”) implies that they are primitive relatives of the larger sauropods (fig. 12.2A). The best known of these is Plateosaurus from the Triassic of Germany (fig. 12.2B), but there are another dozen genera found in Triassic beds all over the world. Most of these creatures were only about 5–8 meters (15–25 feet) long, one-fourth the size of the giant Jurassic sauropods, but larger than their ancestors. They have the beginnings of a long neck and long tail but not yet the incredible neck or tail of the giant sauropods. The limbs are classic sauropod in the construction of their fingers and toes, yet they are not as robust, and the forelimbs are long and delicate enough that they apparently could alternate between quadrupedal walking and rearing up on their hind legs in a bipedal stance to use their hands. Only when the sauropods reached huge sizes were they forced to walk entirely on all fours, and their limbs also become much more massive in support of their huge body weight.

FIGURE 12.2. The prosauropods were transitional forms between smaller primitive bipedal dinosaurs like Eoraptor and the sauropods. (A) Family tree of the sauropods. (Drawing by Carl Buell) (B) Plateosaurus was capable of both bipedal and quadrupedal locomotion and had a neck and tail intermediate in length between smaller dinosaurs and the huge long-necked sauropods. (Photo courtesy R. Rothman)

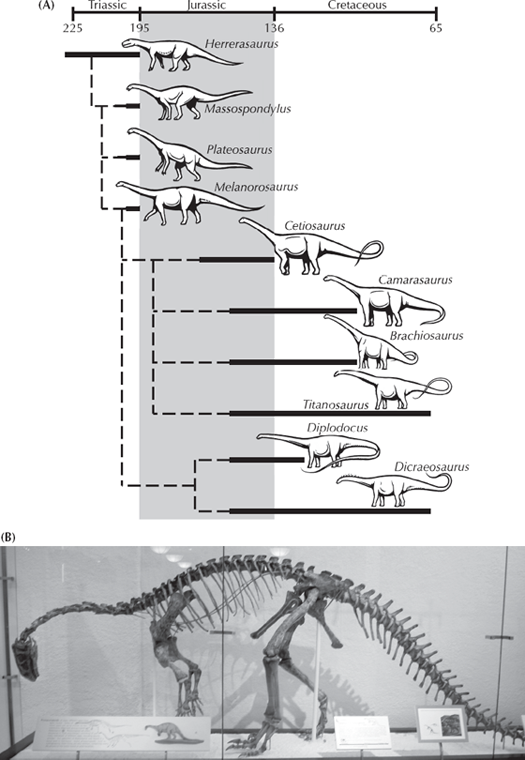

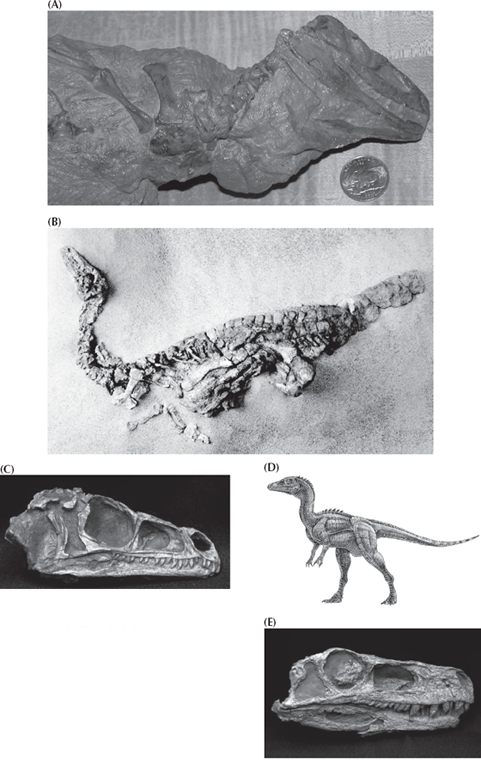

Even more primitive than Plateosaurus was Anchisaurus from the Triassic of Connecticut, Arizona, and South Africa. It was only 2.5 meters (8 feet) long, just slightly larger than a human, and had a still shorter neck and tail and even more delicate limbs and feet. In fact, it is the perfect transitional form between the more lizard-like early saurischian dinosaurs, such as Lagosuchus (which were much smaller, as we shall soon see). Yet despite its outward appearance, its skull bears all the distinctive hallmarks of sauropods, and it already shows many of the specializations in the vertebrae and especially in the hands and feet that will later come to mark the sauropods. The early saurischians (the “lizard-hipped” dinosaurs) were primarily bipedal, but Anchisaurus seems to have been capable of both stances, and Plateosaurus was even heavier and more likely to be quadrupedal. We have not only a smooth increase in size from the earliest known dinosaur Eoraptor (fig. 12.3B-D) to Anchisaurus to Plateosaurus to the larger sauropods but also a smooth transition in the anatomical features and in the stance from bipedal to quadrupedal as well.

FIGURE 12.3. (A) Partial skeleton of a primitive archosaurian relative of dinosaurs known as Euparkeria from the Early Triassic of South Africa. (Photo by the author) (B–D) The earliest and most primitive known dinosaur, Eoraptor from the Late Triassic of Argentina. (B) A complete articulated skeleton; (C) close-up of the skull; (D) reconstruction of Eoraptor in life. (E) Skull of Herrerasaurus, another primitive dinosaur from the Late Triassic of Argentina. (Photos (B–E) courtesy P. C. Sereno, University of Chicago)

The other main branch of the saurischians was the theropods, or the predatory dinosaurs. These are all familiar to us from the giants like Tyrannosaurus rex and the Jurassic predator Allosaurus, but there are dozens of different genera and species of all shapes and sizes. Among the more aberrant were the “ostrich dinosaurs,” which had long legs, long necks, and toothless beaked heads much the living ostrich, but they also had a long bony tail (which no living bird has). Gish (1995:124) briefly mentions some of the primitive theropods but clearly has not kept up with the times.

Despite Gish’s denials, some of the primitive theropods are actually excellent transitional forms (fig. 12.3). They ranged from only 70 centimeters (2 feet) long (Compsognathus) up to 3 meters (10 feet) long (Coelophysis), so most were about the size of a chicken up to the size of an adult human (fig. 12.4). Unlike their big theropod descendants, they were lightly built, with small heads, long necks, and slender gracile limbs and tails. Yet their skulls and especially their hands (with their unique combination of only three fingers: the thumb, index, and middle finger) and feet had all the anatomical specializations seen in later theropods.

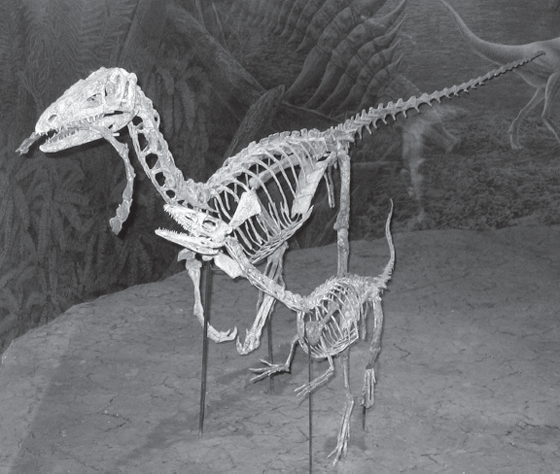

FIGURE 12.4. There are many transitional forms between the earliest dinosaurs like Eoraptor and the more advanced groups. This is Coelophysis, one of the smallest and most primitive carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. (Photo courtesy L. Taylor)

From primitive theropods like Coelophysis, we can trace the theropod lineage even farther back to Eoraptor (fig. 12.3B–D), Staurikosaurus, and Herrerasaurus (figure 12.3E), which are built much like Coelophysis but do not yet have all the distinctive specializations of theropods. To a casual observer, they look very similar, but to a paleontologist with anatomical training, the differences are clear. Eoraptor, Staurikosaurus, and Herrerasaurus lack the highly specialized three-fingered hand (some still had the full five fingers), the relatively unspecialized vertebrae (both sauropod and theropod vertebrae are very specialized and distinctive), a sliding jaw joint, the fully recurved predatory teeth, and the distinctively theropod modifications of the ankle and foot found in Coelophysis and more advanced theropods. Finally, we can trace creatures like Eoraptor, Staurikosaurus, and Herrerasaurus back to primitive nondinosaurian archosaurs like Euparkeria (fig. 12.3A), which superficially resembles the earliest dinosaurs but lacks the unique specializations that all dinosaurs have, such as the open hip socket or the distinctive features in the skull.

Thus we can trace both sauropods (through the primitive prosauropods) and theropods (through the primitive creatures like Coelophysis) to a common saurischian ancestor along the lines of Eoraptor, Staurikosaurus, and Herrerasaurus, and from there to more primitive archosaurs that were not dinosaurs, like Euparkeria. You could not ask for a nicer series of transitional forms. Apparently, Gish never heard of any of these.

And there’s a cool final twist to this story of predatory dinosaurs. In 2005, my friend Jim Kirkland and others announced the discovery of a remarkable new fossil known as Falcarius utahensis from the Jurassic of Utah (fig. 12.5). This strange creature is a member of an even stranger group known as therizinosaurs, whose exact position within the dinosaurs has long been controversial. These beasts have many of the hallmarks of theropods like Velociraptor, including long clawed fingers on the hands and a long neck and tail for balancing. But they had toothless beaks and were apparently herbivorous. In recent years, the consensus was that therizinosaurs were indeed theropods that had somehow returned to plant eating. The discovery of Falcarius provided the “missing link” in this dietary transition because it retains many “raptor” dinosaur features yet is the most primitive therizinosaur with a toothless herbivorous beak. Thus it was a classic transitional form not only in linking therizinosaurs anatomically to raptors but also in showing how they made the remarkable transition from carnivore back to herbivore.

FIGURE 12.5. Transitional fossils among the dinosaurs. This is the therizinosaur Falcarius, which shows the transition between carnivory and herbivory in this peculiar theropod group, shown next to Dr. Jim Kirkland, who discovered and described it. (Photo courtesy J. Kirkland)

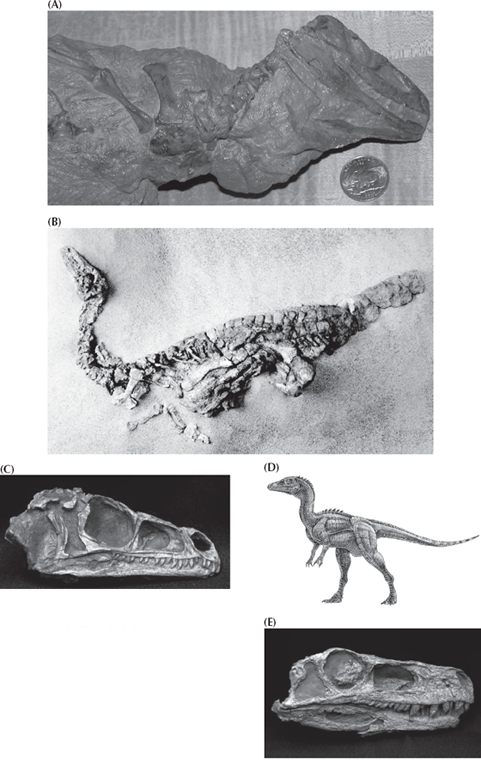

The other main branch of dinosaurs is the Ornithischia, which includes nearly all the herbivorous dinosaurs (except sauropods): the duckbills, the iguanodonts, the turtle-like armored ankylosaurs, the spiky stegosaurs, the bone-headed pachycephalosaurs, and the frilled and horned ceratopsians. The earliest ornithischians include primitive Triassic forms such as Lesothosaurus, Fabrosaurus, and Heterodontosaurus, which are small bipedal dinosaurs that look superficially like Eoraptor or Coelophysis (fig. 12.6). But on closer inspection, they show all the hallmarks of the ornithischians: part or all of the pubic bone in the hip is rotated back parallel to the ischium; the cheek teeth are deeply inset inside the jaw, suggesting that they had cheeks to confine their food in their mouths while they chewed; and they have a unique extra bone at the tip of the lower jaw known as the predentary bone. All these features are unique to the Ornithischia, yet we can see the transitional forms like Heterodontosaurus already had them in the Triassic while they still resembled the other primitive dinosaurs of the time.

FIGURE 12.6. Heterodontodosaurus, the most primitive known ornithischian dinosaur. Although it looked superficially like Eoraptor and Coelophysis in its small size and bipedal stance, it had the unique predentary bone, backward rotated pubic bones, and other hallmarks of the ornithischians. (Photo courtesy R. Rothman)

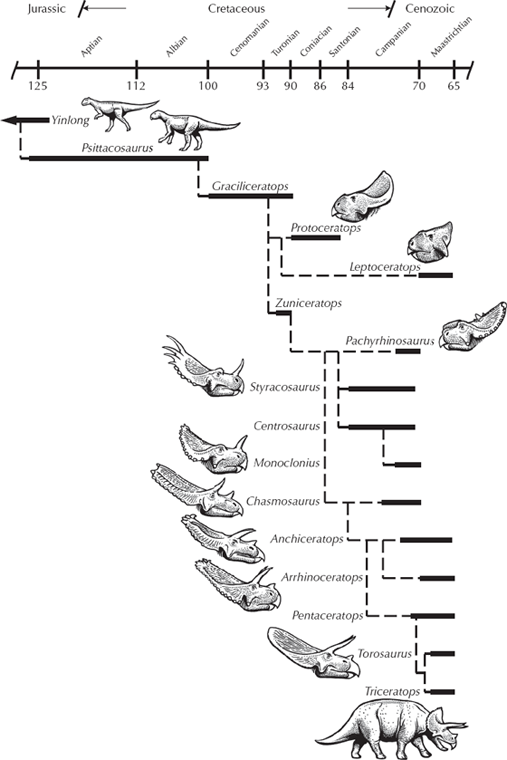

The other example that Gish always trotted out is Triceratops, one of the last of the horned dinosaurs or ceratopsians. Even in his 1995 book (pp. 119–122) he talked about it and a few other ceratopsians, claiming there are no transitional forms—and completely missing the point of everything he has read! Ceratopsians provide yet another classic case of transitional forms between highly specialized forms, such as the horned and frilled ceratopsians, and much more primitive forms that resemble the common ancestor with other dinosaur lineages.

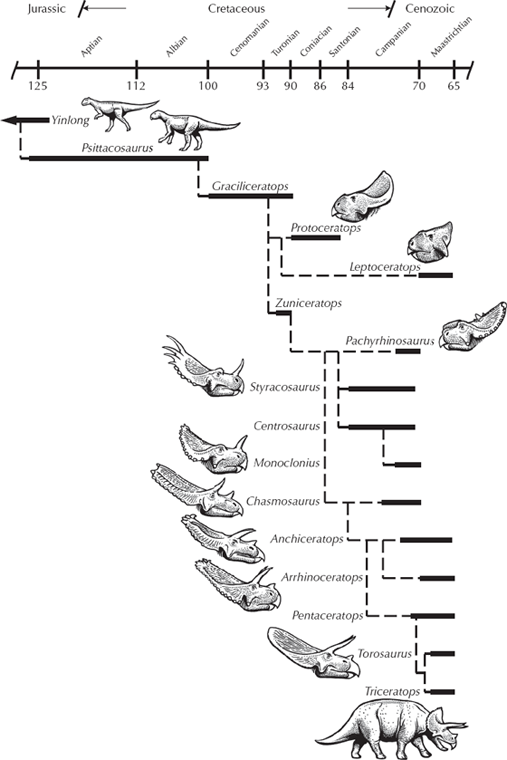

In the case of the Ceratopsia, the transition is clear. All of the creatures with horns can be traced back to the very well known Protoceratops, which has the frill over the neck and the distinctive bones in the beak and lower jaw but lacks the horns (fig. 12.7). From the very beginning, paleontologists pointed to Protoceratops as a nice transition between horned ceratopsians and more primitive dinosaurs, but Gish apparently couldn’t figure this out. He cites one out-of-context quotation from the first edition of Weishampel et al. (1990) about the distinctiveness of the Protoceratopsidae (completely missing the point that this does not make them any less a good transitional form), and he also mentions that they occur in the Late Cretaceous, so they can’t be ancestral. First, paleontologists are not looking for ancestors but for sister groups (see chapter 5). Second, Protoceratops occurred in the early Late Cretaceous, millions of years before all of its presumed descendants among the Ceratopsia in the late Late Cretaceous.

FIGURE 12.7. The evolutionary tree of the horned dinosaurs from Yinlong and other primitive marginocephalans. (Drawing by Carl Buell)

And we have even better transitional forms. Bagaceratops (fig. 12.7) has a slightly smaller frill and beak compared with Protoceratops, and its body is not fully quadrupedal. Archaeoceratops has an even smaller frill and beak, and a body that is much lighter and most likely bipedal. Psittacosaurus (the “parrot lizard”), which was so named because it had a parrot-like beak (composed of the rostral bone unique to the Ceratopsia) and the beginnings of a frill over the neck, is much more lightly built with a bipedal, gracile skeleton rather than the heavier skeleton of Protoceratops. This creature not only shows the transition from frill-less skull to one with a small frill to the larger frill of Protoceratops, but it also shows the transition from a light bipedal body (typical of nearly all the primitive dinosaurs) to the heavier quadrupedal body of the more specialized groups.

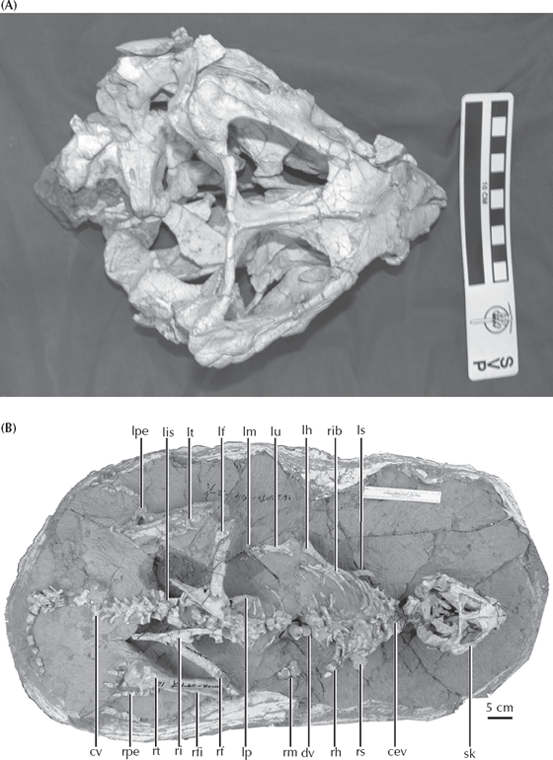

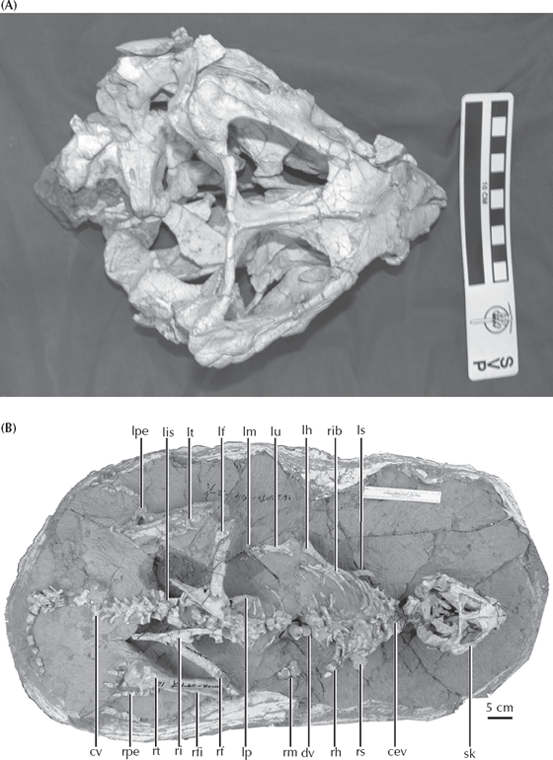

Finally, the most amazing transitional fossil in this sequence was revealed with the 2004 discovery of Yinlong (fig. 12.8) from the much earlier beds of the Late Jurassic of China (Xu et al. 2006). Its name means “hidden dragon” in Mandarin, in reference to the popular movie Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which was partially filmed near the locality where the fossil was found. Yinlong consists of a beautifully preserved skeleton of a bipedal dinosaur not too different in proportions from Psittacosaurus. It has the rostral bone unique to ceratopsians on the tip of its upper beak. However, its skull roof has a unique configuration of bones found in the “bone-headed” dinosaurs, the pachycephalosaurs, which are famous for having a thick dome of bone in their skulls protecting their tiny brains. Paleontologists have long argued that ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs are closest relatives, based on the fact that they both have a frill of bone around the back margin of the skull (hence their name, “Marginocephala,” or “margin heads”). But with Yinlong, we have a beautiful transitional fossil that shows features of both ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs before their lineage split into the two families that every kid recognizes.

FIGURE 12.8. (A) The primitive marginocephalan Yinlong, which shows skull features linking both horned dinosaurs (ceratopsians) and the bone-headed pachycephalosaurs. (B) The complete articulated skeleton of Yinlong. For explanation of labels see Xu et al. (2006) (Photos courtesy J. Clark, George Washington University)

As usual, Gish hadn’t done his homework or bothered to read more recent sources. The fact that he cited an out-of-context quotation from Weishampel et al. (1990) shows that he could apparently read a more authoritative source, but either he could not read well enough to also discover that the other transitional forms like Psittacosaurus are mentioned in the same chapter or his biases were so strong that he can only find short snippets that fit his prejudices. Either way, he completely missed the forest for the trees. And he definitely hasn’t looked at the fossils himself or acquired the training necessary to understand what he was looking at. During our debate, I nailed him on this point. After he blathered on and on about no transitional ceratopsians, I showed him not only the examples just discussed but gave my personal testimony. When I was a graduate student, most of the good specimens of Psittacosaurus and Protoceratops had been cluttering up my office in the American Museum of Natural History for months because my officemate, Dan Chure (recently retired after almost 40 years as the paleontologist at Dinosaur National Monument), had been studying the specimens for his thesis. Not only did I know more about these transitional fossils than Gish, but I have actually studied them as well.

We could go on and on debunking creationist falsehoods about dinosaurs. Anyone with a moderate interest in the subject can peruse the chapters in some of the books listed at the end of this chapter (such as Norman 1985; Weishampel et al. 2004; Fastovsky and Weishampel 2005) and see the beautiful intermediate fossils for nearly every group that Gish denies have transitional forms. There are excellent specimens of primitive relatives of duckbill dinosaurs (they are called ornithopods), of primitive armored ankylosaurs known as nodosaurs (with very limited armor and very primitive delicate skeletons compared to the huge Ankylosaurus), and of primitive stegosaurs, such as Scelidosaurus, which has limited armor, smaller size, delicate limbs, and a very primitive skeleton compared with Stegosaurus. We can trace all of these ornithischian dinosaurs (plus the ceratopsians) back to the most primitive forms, such as Heterodontosaurus (fig. 12.6) and Fabrosaurus from the Triassic. These creatures, in turn, looked very similar in their external features to Eoraptor and Herrarasaurus, the earliest dinosaurs, except for a few subtle differences, such as the presence of a predentary bone at the tip of the lower jaw and a primitive ornithischian hip structure. If one reads the literature carefully and with an open mind, these transitions are obvious. If you read with the denial filter of Gish, who only found quotes out of context that seem to support his view, you will get the distorted, misleading version that he presents.

And if the whole hindquarters, from the ilium to the toes, of a half-hatched chick could be suddenly enlarged, ossified, and fossilised as they are, they would furnish us with the last step of the transition between Birds and Reptiles; for there would be nothing in their characters to prevent us from referring them to the Dinosauria.

—Thomas Henry Huxley, “Further Evidence of the Affinity Between Dinosaurian Reptiles and Birds”

In 1861, just 2 years after Darwin’s book was published, a remarkable specimen was found in the limestone quarries of Solnhofen in Bavaria, southern Germany. These quarries had been excavated for years because they produced nice flat slabs of extremely fine-textured limestone that could be etched with acid to form the lithographic plates that printers used to make book illustrations. Occasionally, these limestones would also yield exquisitely preserved fossils as well, including the tiny dinosaur Compsognathus (the “compys” of Jurassic Park fame) and some of the first good pterodactyls. But in 1860, an impression of a fossil feather was found, and six months later, workers found a partial skeleton of a peculiar creature that had feathers but bones like a dinosaur.

Naturally, this specimen caused a sensation, and the British Museum in London outbid all the others to acquire it. As soon as it reached London (it is still known as the “London” specimen for where it now resides), it was the responsibility of Richard Owen, curator of the British Museum, and the man who named the “Dinosauria,” to describe it. It had already been named Archaeopteryx (“ancient wing”), and although Owen basically described it as a bird, he could not help but see all the dinosaurian characteristics of the skeleton. But because he was one of the last reputable biologists to resist evolution, he made no effort to connect this fossil with its relatives.

However, the dinosaurian characteristics did not escape Owen’s rival, Thomas Henry Huxley, who by this point had become “Darwin’s bulldog” and was making speeches and publishing works that supported Darwin’s theory. Having been one of the first to do anatomical studies of modern birds, and having studied a number of dinosaurs like Compsognathus, Huxley could not help but notice that Archaeopteryx was a classic “missing link” between birds and dinosaurs. At a famous presentation in front of the Royal Society in 1863, he proposed that birds were descended from dinosaurs and listed 35 features shared only by nonavian dinosaurs and birds (17 of these are still used by modern paleontologists). By 1877, an even better fossil was found, the classic “Berlin specimen” (see page 151), which is the best preserved of the 12 known specimens. By then, the Germans had come to realize the importance of Archaeopteryx. German industrialists bought it and made sure it stayed in Berlin, where it is now on display in the Museum für Naturkunde. It even survived the bombing during World War II. I have seen both the original London and the Berlin specimens close up, and it is like a pilgrimage to the Holy Grail to see such amazing and historic fossils rather than photographs or casts.

After Huxley’s efforts, the dinosaur-bird hypothesis declined in popularity as another paleontologist, Harry Govier Seeley, challenged it. In 1926, the artist Gerhard Heilmann proposed that birds originated from more primitive archosaurs (then known as “thecodonts”), and his influence dominated for half a century. Heilmann did not have much evidence to contradict Huxley’s hypothesis, except that he argued that none of the known theropod dinosaurs that could be related to birds had clavicles or collarbones, yet all birds have their clavicles fused into the “wishbone,” which serves as an important “spring” in the flight stroke. (Clavicles have since been found in a number of theropods, removing this objection; they are just delicate and rarely preserved). Of course, this is pure ancestor worship. Heilmann’s preferred candidates (such as Euparkeria) among the archosaurs are simply primitive with respect to all dinosaurs. In the process, he ignored all the derived similarity between dinosaurs and birds that Huxley had demonstrated, largely because most paleontologists thought of dinosaurs as big and specialized and couldn’t imagine birds originating from these huge land animals. Heilmann’s thinking was also dictated by scenarios about how birds evolved flight by gliding from branch to branch (the “trees down” hypothesis), and large terrestrial dinosaurs don’t fit that scenario.

The “birds as dinosaurs” hypothesis remained unfashionable until the 1970s, when Yale paleontologist John Ostrom (a good friend of mine, he died in 2005) looked at the specimens in Europe again. He found one specimen in the Teyler Museum in the Netherlands that had been misidentified as a pterosaur in 1855, but when he looked closer, he saw faint feather impressions and knew he had another specimen of Archaeopteryx. Meanwhile, a specimen in the Eichstatt Museum found in 1951 had been misidentified as the Solnhofen dinosaur Compsognathus, until F. X. Mayr found feather impressions on it 20 years later. The fact that a small dinosaur and Archaeopteryx could be so easily mistaken for each other was a revelation for Ostrom. He revived Huxley’s hypothesis and added a long list of evidence to support it further. He was influenced by the fact that in the 1960s he had discovered and described the highly specialized dinosaur Deinonychus (misidentified as “Velociraptor” in the Jurassic Park movies), which shows amazing anatomical similarities to the earliest birds.

After Ostrom’s initial papers, the controversy over the “birds are dinosaurs” hypothesis raged for several years but quickly resolved because the evidence soon became overwhelming. Hundreds of specialized shared-derived characters support the hypothesis (Gauthier 1986), and there are no competing hypotheses with even a fraction of that support. All but a tiny minority (less than 1 percent) of paleontologists are convinced by the data, especially with the discovery of feathered nonavian dinosaurs from China that we shall discuss shortly. Those few who insist that “birds are not dinosaurs” have no competing hypothesis with any strong support, and their case consists largely of trying to nitpick individual characters that occur both in birds or dinosaurs. They do not address the overwhelming evidence of most of the characters. Indeed, they don’t use or seem to understand cladistics, which is part of the problem. Another part of the problem is that they are wedded to the “trees down” hypothesis of the origin of flight and cannot imagine terrestrial dinosaurs evolving flight from the “ground up.” Ken Dial (2003) showed that their emphasis on the “trees down” origin of flight is misguided. Many birds, such as chukar partridges, use the lift of their wings to help them run up steep inclines but seldom use them for flight. It is easy to see how dinosaurs (which already had feathers for insulation, as we will see later) could have adapted these structures to make climbing steep inclines easier, and from there began to develop short glides and eventually true flight.

But evolutionary scenarios must not drive the analysis, and scientists still have to abide by the rules of science and provide positive evidence and well-supported alternative hypotheses, not “just-so” stories. As detailed by Norell (2005:215–229), their attacks on the widely accepted hypothesis mostly amount to ridiculous and often self-contradictory sniping, without proposing an alternative hypothesis of their own. In that respect, they resemble the creationists, who attack one tiny detail of the subject without addressing all the rest of the evidence.

New discoveries have further reinforced the point that theropod dinosaurs were birdlike not only in their anatomy but also in their behavior. In the 1990s, expeditions from the American Museum of Natural History to the Gobi Desert in Mongolia made some remarkable discoveries, including nests of eggs of the dinosaur Oviraptor. These eggs were so common in Mongolia that the original American Museum expeditions in the 1920s had attributed them to the most common dinosaur of these beds, the primitive horned Protoceratops (fig. 12.7). When bones of a small theropod were found near some nests, they were given the name Oviraptor (“egg thief”). But the recent expeditions show that this name is slanderous: Oviraptor wasn’t stealing the eggs—it was their mother! In some cases, the female Oviraptor skeleton was entombed in brooding posture right on top of the eggs as they were both buried in a sandstorm and fossilized. The details of this brooding posture and the way in which it was preserved show that many theropod dinosaurs acted more like birds than like reptiles.

Fastovsky and Weishampel (2005:261) point to another problem: the media. The debate has been unnaturally prolonged by media attention. The origin of birds has been a topic of great public interest for the past 20 years, so much so that the leading proponents are frequently interviewed for newspaper articles and TV specials. The rules of journalism require that “equal time” be given to representatives of each viewpoint. So the supports of the basal diapsid origin of birds often have as much airtime as the supporters of birds as dinosaurs, even though the latter represent probably more than 99 percent of working vertebrate paleontologists.

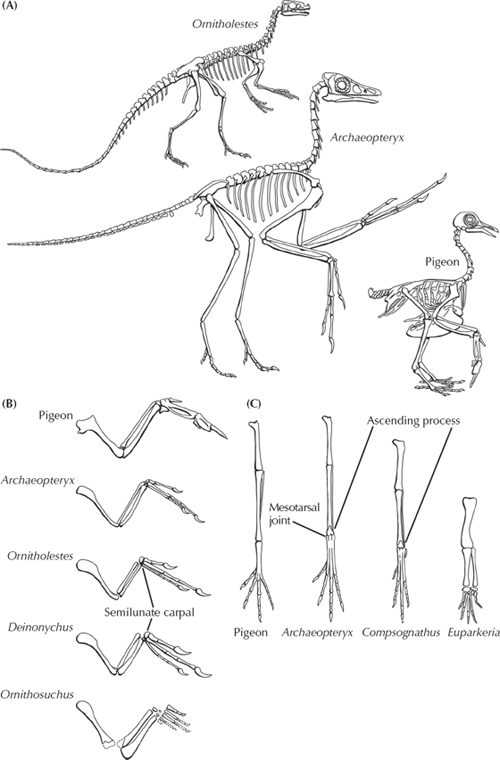

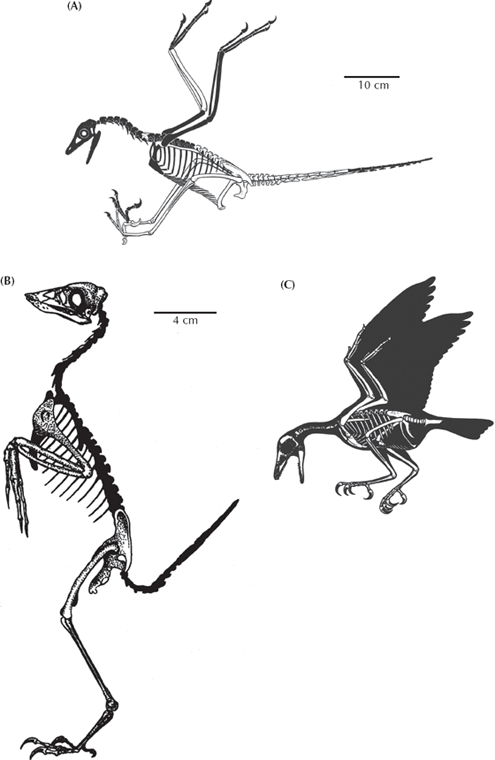

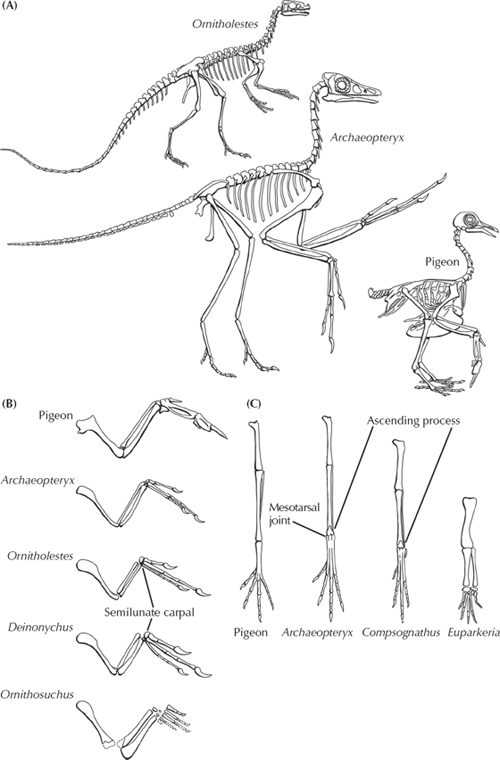

Before we deal with the creationist distortions about Archaeopteryx, let us review the evidence that convinced 99 percent of legitimate scientists that birds are dinosaurs. Much of this evidence is visible in Archaeopteryx itself (fig. 12.9A) and pointed out by Huxley from the beginning. Darwin could not have asked for a better transitional form than Archaeopteryx. As we saw earlier, most of its skeleton is so dinosaurian that one specimen was mistaken for the little theropod dinosaur Compsognathus. Like most theropod dinosaurs (but no living birds), it had a long bony tail, a highly perforated skull with teeth, theropod (not birdlike) vertebrae, a strap-like shoulder blade, a pelvis midway between that of typical saurischian dinosaurs and later birds, gastralia (rib bones found in the belly region of dinosaurs), and unique specializations in the limbs. The most striking of these are in the wrist. Birds and some theropod dinosaurs, such as the dromaeosaurs (Deinonychus and Velociraptor and its kin), all have a half-moon-shaped wristbone formed of fusion of multiple wristbones known as the semilunate carpal (fig. 12.9B). This bone serves as the main hinge for the movement of the wrist, allowing dromaeosaurs to extend their wrists and grab prey with a rapid protraction and retraction. It so happens that exactly the same motion is part of the downward flight stroke of birds. Archaeopteryx had the same three fingers (thumb, index finger, and middle finger) as most other theropod dinosaurs, and the middle digit (the index finger) is by far the longest. In addition, the claws of Archaeopteryx are very similar to those of theropod dinosaurs.

FIGURE 12.9. (A) Comparison of the anatomical features of Archaeopteryx with a more advanced bird, and with a small theropod dinosaur like Ornitholestes. (B) Anatomy of the forelimb of birds and dinosaurs, showing the semilunate carpal, or wristbone. (C) Anatomy of the hind leg of birds and dinosaurs, showing the mesotarsal joint and ascending process of the astragalus.

The hind limbs of Archaeopteryx also have many dinosaurian hallmarks. The most striking of these is in the ankle (fig. 12.9C). All pterosaurs, dinosaurs, and birds have a unique ankle arrangement known as the mesotarsal joint. Instead of the typical vertebrate ankle, which hinges between the shin bone (tibia) and the first row of ankle bones (as your ankle does), pterosaurs, dinosaurs, and birds developed a hinge between the first and second row of ankle bones, or within the ankle (mesotarsus). The first row of ankle bones thus has little function except as a passive hinge, and in many taxa, it actually fuses on to the end of the shin bone as a little “cap” of bone. The next time you eat a chicken or turkey drumstick (which is its tibia bone), notice that inedible cap of cartilage at the less meaty “handle” end of the drumstick is actually a relict of the dinosaurian ancestry of birds! In addition, part of this first row of ankle bones has a bony spur that runs up the front of the tibia (the ascending process of the astragalus), another feature unique to saurischian dinosaurs and birds. Finally, the details and the structure of the toe bones and the short hallux, or big toes, are unique to theropod dinosaurs and birds as well, although Archaeopteryx did not have the opposable big toe that would have enabled it to grasp branches well.

With all this evidence that Archaeopteryx is basically a feathered dinosaur, why call Archaeopteryx a bird at all? In fact, it has only a few uniquely birdlike features not found in other theropods: the big toe is fully reversed, the teeth are unserrated, and the tail is relatively short but the arms are long compared to most other theropods. All the other features of Archaeopteryx, including the feathers and the fused collarbones or “wishbone,” have now been found in other theropod dinosaurs, although some say that the feathers of Archaeopteryx are more advanced than those in theropods and have the asymmetry that suggests that Archaeopteryx could fly.

In light of all this overwhelming evidence, it is bizarre to read how the creationists distort and misrepresent Archaeopteryx. In their minds, the created “kinds” have to be distinct, and transitional forms cannot exist, therefore they will do whatever it takes, no matter how dishonest and unscientific, to try to discredit Archaeopteryx. Because Archaeopteryx had feathers, in their minds it must be part of the bird “kind,” so the creationists will simply say that it’s a bird and either distort or not even address the long list of dinosaurian features in the specimen. For example, the creationist books by Davis and Kenyon (2004:104–106), Sarfati (1999:57–68; 2002:130–132), Wells (2000:111–135), and Gish (1995:129–139) mostly quote out-of-date sources to try to discredit Archaeopteryx and the “birds are dinosaurs” hypothesis. Or they quote old papers by the tiny handful of crank scientists like Alan Feduccia and the late Larry Martin, who disagreed with 99 percent of the profession—but they don’t mention the devastating counterarguments against the ideas proposed by Feduccia and Martin. Gish (1995) and Sarfati (1999) argue that Archaeopteryx teeth are not like those of theropod dinosaurs but like those of other toothed birds (which is not true, by the way—they have both primitive similarities with theropod teeth and their own derived features), but this whole argument misses the point: no living birds have teeth, yet if fossil birds like Archaeopteryx had them, it links birds and dinosaurs. (Recall from chapter 4 that birds still have the embryonic genes for teeth, but these are normally suppressed during development). Gish (1995) and Sarfati (1999) briefly mention the long tail of Archaeopteryx and then blithely say that some reptiles and some birds have long tails and some have short ones. The point is that no living bird has a long bony tail (all the tailbones of living birds are fused into the “parson’s nose,” or pygostyle, and the tail is supported by feather shafts instead), yet Archaeopteryx, which even Gish admits is a bird, has the long bony tail of dinosaurs. Gish attempts to discredit the three bony clawed fingers of Archaeopteryx by pointing to the hoatzin birds of Central America, which also have these three fingers while they are chicks (although he fails to mention that their configuration is entirely different). But one isolated atavism does nothing to discredit the fact that the hand of Archaeopteryx is fundamentally dinosaurian. No other living birds besides the hoatzin chicks have this type of hand, which is highly specialized and in no way resembles the hand of Archaeopteryx. In short, every time Gish, Sarfati, and the other creationists mention a feature that makes Archaeopteryx a dinosaur, they distort the evidence, show their ignorance of the anatomical details, or fail to mention counterarguments or details that would discredit their case. Nowhere do the creationists discuss the other 100 or so anatomical characters, including such unique dinosaurian features as the mesotarsal joint and the semilunate carpal. On those grounds alone, their arguments are worthless and only show how poorly creationists understand the anatomy of these creatures.

The creationists are so wedded to the idea of distinct “kinds” that they cannot even conceive of intermediate forms. Gish was embarrassed during several debates in just this way. When his opponent put up an image of the forelimb of a modern bird and of a theropod dinosaur (fig. 12.19B) and challenged Gish to sketch the likely intermediate anatomy, Gish declined (because he knew it was a trap). Sure enough, his opponent then revealed the forelimb of Archaeopteryx as a perfect intermediate between birds and dinosaurs. Gish then mumbled something irrelevant and tried to change the subject. Even more dishonestly, he went on with the same deception at the next debate venue, never correcting mistakes when he was shown to be lying.

The intelligent design creationist authors are even more subtle and misleading. They use a few out-of-context quotations that do not apply to this case and fall back on the old misconception that evolution must be a smooth gradual “chain of being” within a single lineage. Davis and Kenyon (2004:106) write that Archaeopteryx “is transitional only if it is part of lineage—one of series of generations in which in-between stages led gradually from one group to another” (illustrated clearly in their figs. 4–11, p. 106). In one sentence, they have shown their complete misunderstanding of the fundamental concepts of evolution. Archaeopteryx does not have to be part of single, gradually evolving lineage to be a transitional form—those are all misunderstandings about evolution discredited decades ago. It only needs to be one of many species that show transitional features on the bushy, branching tree of life. And in this respect, Archaeopteryx could not be a better intermediate transitional form. Wells (2000) claims that paleontologists have “quietly shelved” Archaeopteryx and that it is not an “ancestor” because modern birds are not descended from it. This completely misses the point. Archaeopteryx does not have to be an actual ancestor to show us how birds evolved from dinosaurs. It has all the transitional features that one might expect from the sister group or “collateral ancestor” of birds (and has no unique specializations that would preclude it from being the actual ancestor). And nobody has “quietly shelved” it—it is still being published on and studied and mentioned in the ever-burgeoning field of Mesozoic bird paleontology.

Finally, Davis and Kenyon, Sarfati, Wells, and Gish all argue that because Archaeopteryx and its dinosaurian kin are the same age (or some of the dinosaurian sister taxa appear later than Archaeopteryx), then the dinosaurs cannot be ancestral to the birds. As we have said over and over, evolution is a bush, not a ladder. Archaeopteryx and other theropods are sister taxa, and their relationships are supported by shared derived characters. Age relationships are irrelevant (especially in such rarely fossilized animals as small dinosaurs and birds). They shared common ancestors back in the Middle Jurassic, when we have a very poor record of terrestrial vertebrates worldwide, so that by the Late Jurassic, the lineages have just split apart, and both theropods and Archaeopteryx were living side by side.

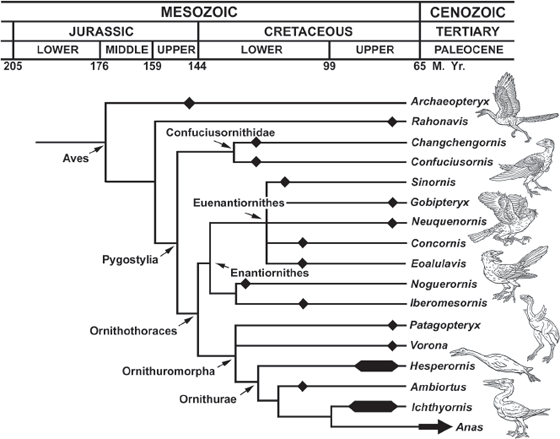

But all these arguments of the creationists, as well as the “birds are not dinosaurs” minority like Martin and Feduccia, are now rendered entirely obsolete by an amazing array of new discoveries that have occurred in the past 20 years. If Archaeopteryx were still the only transitional dinosaur-bird fossil, it would be sufficient, but it is not alone any more. An amazing array of new transitional bird fossils and feathered nonbird dinosaurs have been discovered and described (figs. 12.1, 12.6, 12.10, and 12.11) that fill in most of the gaps between theropods and advanced birds, so now we have a wealth of transitional forms, of which Archaeopteryx is just one link.

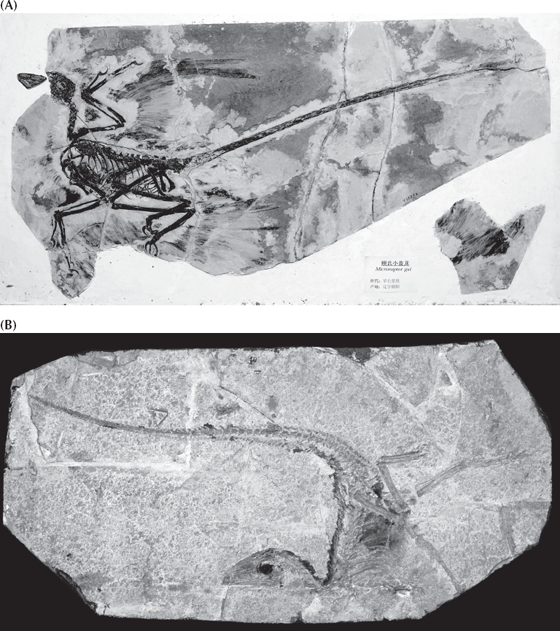

FIGURE 12.10. Meilong, a feathered dinosaur from the Liaoning beds that is preserved as an extraordinary three-dimensional specimen coiled up in a sleeping position. (Courtesy M. Ellison and M. Norell, American Museum of Natural History)

FIGURE 12.11. Feathered nonflying dinosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous Liaoning beds of China, which show the early stages of evolution from dinosaurs to birds. (A) Microraptor, which had feathers on both its hands and legs, although it is still controversial whether it flew. (B) Sinosauropteryx, the first feathered nonavian dinosaur to be discovered, with its beautiful preservation of hairlike feathers (especially visible along the spine). (Photos courtesy M. Ellison and M. Norell, American Museum of Natural History)

The most earth-shaking discoveries come from the famous Lower Cretaceous Liaoning fossil beds of China, which have now become one of the world’s most important fossil deposits. These delicate lake shales preserve extraordinary features in fossils, including body outlines, feathers, and fur, as well as complete articulated skeletons with not a single bone missing. In the past 20 years, a major new discovery has been announced from these deposits every few months, and almost all previous ideas about birds and dinosaurs were quickly rendered obsolete by these discoveries (for a summary, see Norell 2005). The most amazing fossils of all were a number of clearly nonflying, nonavian dinosaurs with well-developed feathers (figs. 12.1, 12.10, 12.11, and 12.12). These include incredible complete specimens such as Sinosauropteryx, Protarchaeopteryx, Sinornithosaurus, Caudipteryx, the large theropod Beipiaosaurus, and the tiny Microraptor.

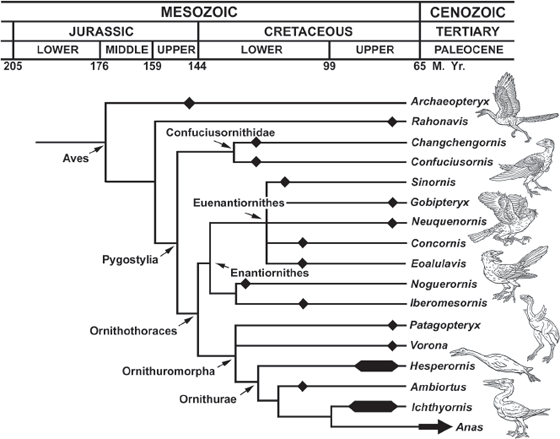

FIGURE 12.12. The family tree of Mesozoic birds, emphasizing some of the recent fossil discoveries. (Courtesy L. Chiappe)

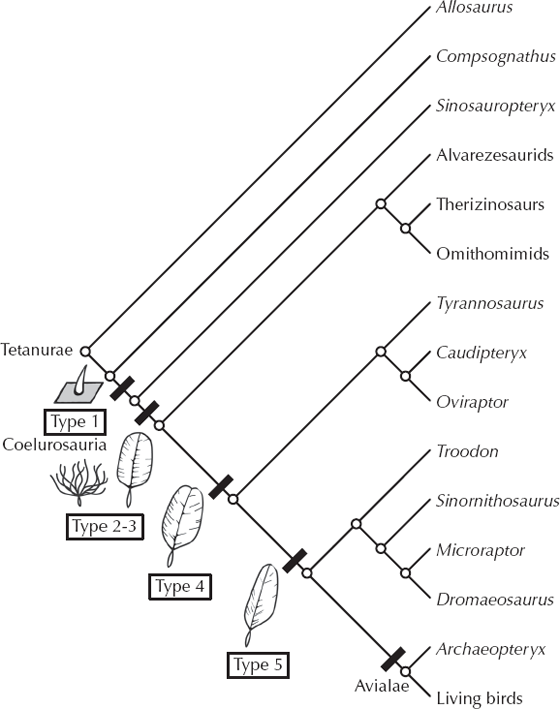

Most of these non-bird dinosaurs clearly do not have flight feathers or other indications that their feathers were used for flight. Instead, they show that feathers were apparently a widespread feature among theropod dinosaurs (and perhaps in other dinosaurs and archosaurs as well, especially pterosaurs). Feathers, then, did not evolve for flight but were already present in theropod dinosaurs, presumably for insulation, and were later modified to become flying structures.

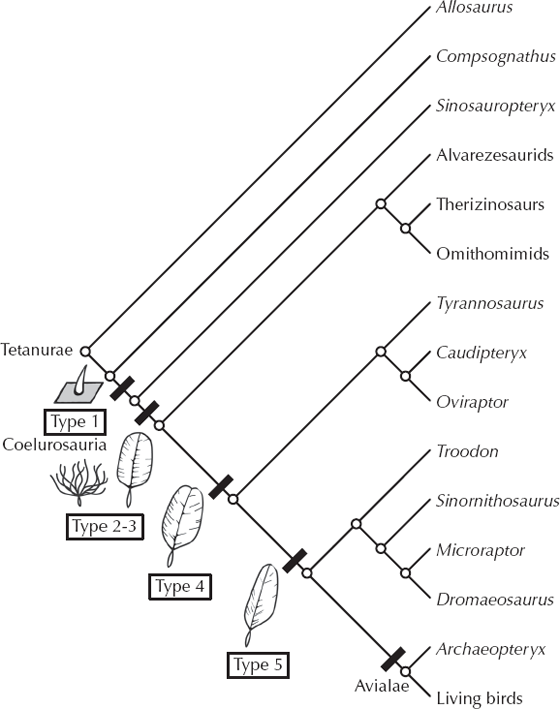

Prum and Brush (2003) have completely rethought the origin of feathers and showed that they are not modified scales (as once believed) but from a similar embryonic primordium with different Hox genes controlling development. Type 1 feathers (fig. 12.13) are simple hollow pointed shafts, which appear in the primitive theropod Sinosauropteryx. Type 2 feathers are simple down with no vanes, and type 3 feathers have a vane and shaft, but no barbules linking them together like Velcro. Both of these types are found in the large therizinosaur Beipiaosaurus, suggesting that they were present in almost all theropods (fig. 12.13). Type 4 feathers have barbules that link the vanes of the feather into a continuous surface, but the shaft is symmetrically aligned down the middle of the feather. This kind of feather appears in Caudipteryx, which suggests that these occurred in higher theropods (including Tyrannosaurus rex) as well. The classic asymmetric flight feather with the shaft near the leading edge of the vane first appears in Archaeopteryx, and for this reason many scientists think that Archaeopteryx was one of the first to modify the long heritage of feathers for true flight.

FIGURE 12.13. The evolution of feather types from simple pinshafts to down plumes to complex flight feathers with asymmetric vanes and shaft. On the basis of their appearance in various feathered nonflying dinosaurs from Liaoning, we can demonstrate that most predatory dinosaurs (including T. rex) probably had feathers of some sort. (Modified from Prum and Brush 2003)

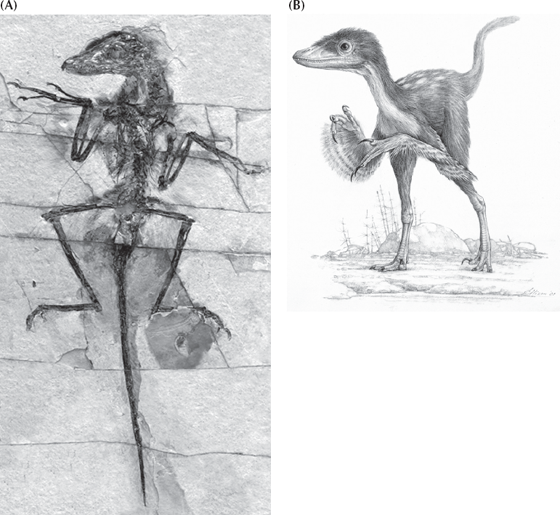

Moving up from Archaeopteryx on the cladogram of birds (fig. 12.12), we come to Rahonavis from the Cretaceous of Madagascar (Forster et al. 1998). About the size of a crow (fig. 12.14A), it had the primitive sickle-like claws on the hind feet, the long bony tail, teeth, and many other theropod features, but it also had birdlike features such as the fusion of its lower back vertebrae with the pelvis (the synsacrum), holes in its vertebrae for all the blood vessels and air sacs found in living birds, fingers with quill knobs, suggesting that it was feathered and could fly (no surprise here), and the fibula (the smaller shin bone) that does not reach the ankle. Birds have reduced the fibula to the tiny splint of bone that you bite into when you are eating a chicken or turkey drumstick, but Archaeopteryx has a fully developed fibula like that of dinosaurs.

FIGURE 12.14. In addition to Archaeopteryx, there are now dozens of new transitional birds from the Mesozoic, each of which shows a mosaic of evolutionary changes from more dinosaur-like creatures like Archaeopteryx to forms that are similar to modern birds in many ways. (A) Rahonavis from the Cretaceous of Madagascar, which still has the teeth, long clawed fingers, and long bony tail of Archaeopteryx, but the hip vertebrae are fused to the hip bones (synsacrum) as in modern birds. (After Forster et al. 1998; copyright © 1998 Association for the Advancement of Science) (B) Confuciusornis from the Cretaceous of China, which has fused the tail vertebrae into a pygostyle, and lost its teeth but still has the long dinosaurian fingers. (After Hou et al. 1995; used by permission of the Nature Publishing Group) (C) Sinornis, a primitive enantiornithine bird from the Cretaceous of China, which still has teeth, an unfused tarsometatarsus, and an unfused pelvis but had shorter fingers, a fully opposable big toe for perching, a broad breastbone for flight muscle attachment, and an even shorter pygostyle in the tail. (From Sereno and Rao 1992: fig. 2. Used by permission of the Nature Publishing Group)

The next step is marked by Confuciusornis and its relatives (fig. 12.14B), which has a unique feature found in all higher birds: the pygostyle, formed by the fusion of all the old dinosaurian tail vertebrae into a single “parson’s nose.” These higher birds have also increased the number of lower back vertebrae fused to the synsacrum and elongated the bones that reinforce the shoulder, which improved flight. They also are the first birds with a toothless beak. Following this transitional form is another branch point that leads to the extinct Enantiornithes, or “backwards birds” (so named because their leg bones ossify in the reverse direction from that found in modern birds). These include Iberomesornis from the Cretaceous Las Hoyas locality in Spain, Sinornis from China (fig. 12.14C), Gobipteryx from Mongolia, Enantiornis from Argentina, and several others. All of these birds are more specialized than Archaeopteryx, Rahonavis, or Confuciusornis in that they have reduced the number of trunk vertebrae, have a flexible wishbone, made the shoulder joint better for flying, fused the hand bones into a bone called the carpometacarpus, and the finger bones into a single element (the meatless bony part of the chicken wing that you never eat).

Continuing up the cladogram, we come to several Cretaceous birds such as Vorona from Madagascar, Patagopteryx from Argentina, and the well-known aquatic birds Hesperornis and Ichthyornis from the chalk beds of Kansas. These birds are united by at least 15 well-defined characters, including the loss of the belly ribs or gastralia, reorientation of the pubic bone to the modern birdlike position parallel to the ischium, reduction in the number of trunk vertebrae, and many other features of the hand and shoulder that improved flight performance. Ichthyornis is even closer to modern birds in having a keel on its breastbone for the flight muscles and a knob-like head on the upper arm bone that made the wing more flexible. Finally, the clade that includes all modern members of class Aves is defined by the complete loss of teeth and a number of other anatomical specializations, such as the fusion of the leg bones to form a tarsometatarsus.

How do creationists respond to this flood of new discoveries? Most of the time, they don’t. Even recent books like Sarfati (1999, 2002) and the constantly updated creationist websites completely ignore them. Wells (2000) ignores nearly all of them except for one specimen, named “Archaeoraptor,” which was a composite forged out of two real fossils by an unknown Chinese fossil dealer. Smuggled out of China, the specimen was bought and made into a big deal by amateur dinosaur illustrators (and by National Geographic, which wanted to get a scoop without waiting for the specimen to be tested by peer review). As soon as well-trained paleontologists looked at the specimen, they quickly detected that it was a composite of two different specimens put together to enhance its sale price, and the specimen was never even formally published in a peer-reviewed journal. Wells (2000) slanders the entire profession by suggesting that one artful hoax (which was quickly exposed as soon as real paleontologists looked at it) implies that all the fossils from China are faked or that qualified paleontologists are easily suckered by fakes. As the facts of the story show, Wells is wrong on all counts.

If this welter of new bird fossils and anatomical characters seems a bit overwhelming, your impression is correct: the past two decades have produced such an explosion of new fossils and new ideas that everything we thought we knew about Mesozoic birds before 1990 is obsolete. Each year brings astonishing new specimens that further transform what we thought we knew about avian evolution. Since the final picture is still taking shape, we cannot tell how many more changes we’ll make in our cladograms of birds before the discoveries start repeating themselves. But one thing is abundantly clear: we now have dozens of beautiful transitions from dinosaurs to birds. The creationist books that focus only on Archaeopteryx and distort the fossil record are so laughably outdated by the new discoveries that their writings are only fit to line the bottom of a birdcage.

For Further Reading

Benton, M. J., ed. 1988. The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods. Vol. 1, Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds. Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon.

Benton, M. J. 2014. Vertebrate Palaeontology. 4th ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. New York: Freeman.

Chiappe, L. M. 1995. The first 85 million years of avian evolution. Nature 378:349–355.

Chiappe, L. M., and G. J. Dyke 2002. The Mesozoic radiation of birds. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 33:91–124.

Chiappe, L. M. and L. M. Witmer, eds. 2002. Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chiappe, L. M., and Meng Qingjin. 2016. Birds of Stone: Chinese Avian Fossils from the Age of Dinosaurs. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Currie, P. J., E. B. Koppelhus, M. A. Shugar, and J. L. Wright, eds. 2004. Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Dial, K. 2003. Wing-assisted incline running and the evolution of flight. Science 299:402–405.

Dingus, L., and T. Rowe. 1997. The Mistaken Extinction. New York: Freeman.

Dodson, P. 1996. The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Fastovsky, D. E., and D. B. Weishampel. 2005. The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fastovsky, D. E. and D. B. Weishampel. 2016. Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History. 3rd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Forster, C. A., S. D. Sampson, L. M. Chiappe, and D. W. Krause. 1998. The theropod ancestry of birds: new evidence from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Science 279:1915–1919.

Gauthier, J. A. 1986. Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds. California Academy of Sciences Memoir 8:1–56.

Gauthier, J. A., and L. F. Gall, eds. 2001. New Perspectives on the Origin and Early Evolution of Birds. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Hou, L.-H. Z., Zhou, L. D. Martin, and A. Feduccia. 1995. A beaked bird from the Jurassic of China. Nature 377:616–618.

Long, J., and H. Schouten. 2008. Feathered Dinosaurs: The Origin of Birds. New York: Oxford University Press.

McGowan, C. 1983. The Successful Dragons: A Natural History of Extinct Reptiles. Toronto: Stevens.

Naish, D., and P. Barrett. 2016. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

Norell, M. 2005. Unearthing Dragons: The Great Feathered Dinosaur Discoveries. New York: Pi.

Norman, D. 1985. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. New York: Crescent.

Ostrom, J. H. 1974. Archaeopteryx and the origin of flight. Quarterly Review of Biology 49:27–47.

Ostrom, J. H. 1976. Archaeopteryx and the origin of birds. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 8:91–182.

Padian, K., and L. M. Chiappe. 1998. The origin of birds and their flight. Scientific American 278:28–37.

Pickrill, J. 2014. Flying Dinosaurs: How Reptiles Became Birds. New York: Columbia University Press.

Prothero, D. R. 2013. Bringing Fossils to Life: An Introduction to Paleobiology. 3rd ed. New York: Columbia University Press.

Prum, R. O., and A. H. Brush. 2003. Which came first, the feather or the bird? Scientific American 288:84–93.

Schultze, H.-P., and L. Trueb, eds. 1991. Origins of the Higher Groups of Tetrapods: Controversy and Consensus. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Shipman, P. 1988. Taking Wing: Archaeopteryx and the Evolution of Bird Flight. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Weishampel, D. B., P. Dodson, and H. Osmolska, eds. 2004. The Dinosauria. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Xu, Xing, C. A. Forster, J. M. Clark, and J. Mo. 2006. A basal ceratopsian with transitional features from the Late Jurassic of northwestern China. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 273:2135–2140.