3

PETRIFIED FOREST NATIONAL MONUMENT

The dog poisoner, the library mutilator and thief, the despoiler of our monuments-these three should be boiled in oil (beginning at zero).

Charles F. Lummis

Closing the petrified forests to settlement was one thing; offering the sites real protection was another. Establishment of a Petrified Forest National Park was a possibility, presuming that the collections of fossil logs could meet the ill-defined requirements for a national park. Failing that, new legislation was needed to extend federal protection to natural sites like Petrified Forest. In fact, these ancient forests were not unique in suffering at the hands of thieves and vandals. Throughout the Southwest, hundreds of prehistoric ruins-America's antiquities-faced similar threats. Within the next decade, archaeological sites, along with historical places and objects of scientific interest, all fell under the protection of the federal government when Congress passed the 1906 Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities. 1

In the meantime, local residents remained concerned about theft and vandalism in the forests, and the stamp mill, though not operating, represented an overwhelming threat to the integrity of any future national park. 2 The owners never started the mill, and the reason has never been fully explained. If Congressman John F. Lacey of Iowa is correct, this "commercial vandalism" was averted only because another suitable stone was found in Canada. 3 At the same time, jewelry and lapidary companies were losing interest in petrified wood as a semiprecious commodity, primarily because it was so difficult to cut.

S. J. Holsinger, special agent for the General Land Office, conducted a thorough examination of Petrified Forest in 1899 and was grateful to learn that comparatively little fossil wood was then being shipped out. More important, he found enthusiastic support among local residents for establishing a federal reserve to protect the petrified wood, the only opponent being Adam Hanna. Holsinger's own examination of the sites convinced him that the region deserved such protection, and he suggested the name of Chalcedonia National Park-the first official notice that the area deserved protection.4 The budding national park movement caught the attention of Charles Lummis, who praised the effort in Land of Sunshine. Protecting the petrified forests would represent an important step in preserving numerous sites in Arizona and New Mexico from the "relic-seekers and money grabbers," he proclaimed. The Arizona Graphic agreed, adding that the next generation would not find a pound of petrified wood if the government did not protect it. 5

Holsinger was not the only federal agent roaming around Chalcedony Park in 1899. In response to the Arizona Legislature's memorial, GLO Commissioner Binger Hermann went to the Smithsonian Institution for information about the site's potential as a national park. The Smithsonian called on Lester Frank Ward, a paleobotanist with the U.S. Geological Survey and associate curator of the National Museum, to visit the forest and determine whether it should be designated as a national park.

Ward arrived in Holbrook on November 9, 1899, and on the following day proceeded to the petrified forests to begin his work. His subsequent report was precisely what Arizona park proponents wanted, for Ward stated that the earlier descriptions by Möllhausen, Marcou, Newberry, and other early explorers had understated both the scientific importance and the popular appeal of petrified forests. The fossil trees truly were among the country's natural wonders, and Ward recommended that the government not only preserve them but advertise the sites for American tourists.6

The petrified trees in northeastern Arizona were millions of years older than those found in Yellowstone and in California. Ward placed them in Mesozoic time and probably of Triassic age, as compared to the Tertiary age (66 million to 1.6 million years old) of the others. Blocks of petrified wood of Triassic age occur in other locations, but the Arizona deposits were much more extensive and were the only ones, according to Ward, that deserved the designation of forest. Ward also was impressed by the unique forms and varied colors exhibited in Chalcedony Park and the nearby deposits. These, he noted, were the major attractions for visitors. The state of mineralization placed some of these specimens in the category of gems and precious stones. Chalcedony and agates were common, many approaching the characteristics of jasper and onyx. 7

Ward added an additional important argument in support of protecting the ancient forests. The stone trees were a source of wonder for visitors. Already mere curiosity had attracted thousands of people to Petrified Forest, and however aimless it might appear, Ward was convinced that curiosity formed the "true foundation of all discovery and progress" and should be carefully nurtured. Here was a natural site that might stimulate the imagination of visitors and expand their perception of the country's ancient natural environment.

The number of visitors and relic hunters naturally would increase, necessitating measures to reduce vandalism and theft. He realized what local residents had known for years-that visitors would take as many specimens as they could carry, although these would likely be only smaller fragments. Ward's report identified the crucial dilemma that would always confront personnel at Petrified Forest: how to facilitate public access to the remarkable collection of fossilized logs while at the same time protecting them from those very visitors. (See also chapter 4 on Ward.)

Ward's observations identified both the scientific value and the popular appeal of Petrified Forest, and he also suggested a framework for interpretive programs to stimulate and guide the natural curiosity of visitors. Yet a critical ingredient of national parks did not figure in his writings on Petrified Forest, or in any of the commentaries of nineteenth-century visitors. Monumental scenery (or variations of that theme), perhaps the feature that most dearly identified the existing six national parks, never appeared in descriptions of Petrified Forest. The fossil forests were remarkable and exhibited their own beauty-but not on the scale of the other parks. Consequently, early arguments for a Petrified Forest National Park would have to rest on other considerations-namely the need to protect this resource from vandals, thieves, and entrepreneurs. Lack of magnificent scenery did not always preclude the park designation. The definition of what constituted a national park remained fluid in the early twentieth century, and a number of small reserves in fact acquired park status.

Because he spoke with the disinterested voice of science, Ward provided critical support for the establishment of a national park to embrace Chalcedony Park and the deposits of petrified wood in the vicinity. Promoters naturally relied on his report as they sought to advance their cause over the next few years. Even before the Smithsonian Institution published Ward's report, "The Petrified Forests of Arizona," Congressman John F. Lacey of Iowa introduced a bill in the Fifty-sixth Congress in 1900 to establish Petrified Forest National Park. A veteran supporter of measures to support wildlife and forests, Lacey also became interested in the preservation of prehistoric ruins in the Southwest and actively promoted legislation to protect these American antiquities. He was a natural advocate for Petrified Forest, which he praised in Congress as "a more wonderful scene than even the Grand Canyon itself." But the focus of his comments was on its vulnerability. "The Grand Canyon of the Colorado and the sunny climate of Arizona can take care of themselves," he told members of the House of Representatives, "but the Petrified Forest will be destroyed unless it is protected by law." 8

Lacey's comments convinced House members, but the bill failed in the Senate. Two years later, in 1902, the Iowan was back in the House of Representatives with essentially the same bill. This time he defended the measure on the basis of the future park's location adjacent to the Santa Fe line, emphasizing that increasing numbers of tourists would visit the place if decent facilities were available. Further, the forest was located in an "atmosphere of the purest and cleanest air ever breathed." The surrounding land was of practically no value, he added, therefore, preserving it would not interfere with any settlement in the area. Lacey's bill embraced about two townships and included an important provision authorizing the secretary of the interior to acquire private holdings within the proposed park through land exchanges. The Santa Fe Railroad owned alternate sections in the area, but Lacey again assured his colleagues that there were no settlers and that the land was "utterly worthless for any agricultural purposes." In so defending park status for Petrified Forest, Lacey employed a theme that conSistently has been used in behalf of national parks-the useless scenery argument. Parks were fashioned only from terrain that held no value for miners, lumbermen, ranchers, or farmers, even though the scenery itself might be spectacular. The requirement of uselessness was an unwritten policy, but no other qualification outweighed it. 9

The bill engendered no debate and little questioning from Lacey's colleagues in the House. It passed easily and was forwarded to the Senate, where it died in the Committee on Public Lands, as had its predecessor. Another measure failed in 1904. Lacey introduced a similar version in 1906, noting that the House had passed bills to establish Petrified Forest National Park in the Fifty-sixth, Fifty-seventh, and Fifty-eighth Congresses. "For some reason I have never been able to learn why," he complained, "the bill has not received favorable action at the other end of the capitol." It had the support of the Interior Department and the General Land Office, and the House Committee on Public Lands also strongly recommended its passage. 10 But this measure, too, died in the Senate Committee on Public Lands.

In the course of debates on Lacey's Petrified Forest bills, congressmen had raised few questions. Only in 1902 did his colleagues press Lacey for any major revision, and then their concern focused only on that bill's land exchange provision. Serano E. Payne of New York, along with a few others, worried that private landowners within the proposed park's boundaries might trade their worthless land for more extensive or more valuable acreage elsewhere. But Lacey included restrictions that virtually eliminated that prospect. That same issue might have arisen in the Senate Public Lands Committee and may explain why the bill never made it out of committee. Arizona then was still a territory, represented in Congress by a Single nonvoting delegate. With no effective representation in either house, Arizonans who favored the measures simply lacked the political influence to push the measure through Congress.

The Petrified Forest bills likely were casualties of the still loosely defined guidelines for establishing national parks. At that early date, a full decade before the establishment of the National Park Service, the federal government had not evolved a coherent set of guidelines for national parks. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Congress had authorized a number of new parks that ranged from Yosemite, Crater Lake, and Mount Rainier to the "inferior parks" at Platt, Wind River, and Sully's Hill. The latter small, "unworthy" parks, historian John Ise complained, simply did not meet the standards embodied in the other "superlative" national parks. In 1906 Congress established Mesa Verde National Park to protect the cliff dwellings in southwestern Colorado, but carefully restricted its acreage to include only the prehistoric sites. The diversity of those national parks underscores the vague requirements that Congress applied to expansion of the country's park system. "If the government had a plan for the parks it was establishing," Joseph Sax has observed, "it certainly was casual about it." 11

For its part, Congress could exhibit a reluctance bordering on stubbornness when considering new parks; at other times it greeted new park proposals with apathy. An earlier bill for Crater Lake National Park engendered no serious opposition when proponents first introduced it, historian H. Duane Hampton has pointed out. Yet sixteen years elapsed before the legislation received approval in 1902. Similarly, the proposed Mesa Verde National Park encountered no opposition in 1891, but its adherents petitioned Congress until 1906 before the new park was finally authorized. Had the 1906 Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities been on the books earlier, Robert W. Righter has speculated, Crater Lake and Mesa Verde would have been deSignated national monuments and then quickly "upgraded" to national parks. This "monument-to-park" device represented a handy way to circumvent a belligerent, reluctant, or merely apathetic Congress. Petrified Forest lost its last bid for national park status just after Congress passed the Antiquities Act. Consequently it was an obvious candidate for preservation under the new law. 12

The energetic Congressman Lacey was among the key figures in shaping that legislation. During the same years when he had shepherded the park measure through the House, he also actively supported bills to protect American antiquities. Throughout the Southwest, theft and vandalism were common occurrences in the isolated prehistoric ruins that dotted the region. Such depredations eventually stimulated a movement to protect all places that contained archaeological sites. That endeavor, if broadened to include scientific and natural sites, might also contribute to the preservation of the Petrified Forest. Although Lacey and others had always praised the valuable deposits of fossil wood there, the site also included a number of important ruins.

Scientists and academics from eastern universities and museums increasingly added their powerful support to the antiquities movement, and they could count on assistance from the Bureau of Ethnology and the Archaeological Institute of America, among other professional organizations. Similarly, the Office of Indian Affairs and the Geological Survey both were concerned about such vandalism on federal lands. Secretary of the Interior Ethan Allen Hitchcock was sympathetic to the movement, as were GLO Commissioners Binger Hermann and W. A. Richards. But the federal government could provide no real protection for archaeological sites, any more than it could safeguard the deposits of petrified wood. Commissioner Richards withdrew some sites from settlement and appointed temporary custodians to look after them, charging these new officials to post notices against trespassing. The General Land Office could punish trespassers, if they were caught. But the agency lacked the personnel to make arrests.

Nor did Congress provide much immediate assistance. Four bills to protect American antiquities were introduced in 1900, but none were successful. Measures proposed in 1904 and 1905 fared no better 13 Despite setbacks in Congress, proponents of a vigorous federal policy of protecting cultural and natural sites persevered. Edgar L. Hewett of the Bureau of Ethnology, in particular, worked closely with federal officials and Congressman Lacey. In 1902, Hewett guided Lacey on a visit to Santa Fe and to the cliff dweller sites in the Pajarito region, providing the congressman with a firsthand introduction to archaeological sites in the Southwest. 14 The knowledge Lacey gained proved valuable in drafting legislation to protect antiquities.

In 1904, Hewett provided an assessment of the archaeological sites in the Southwest; by that date the very abundance of ruins had attracted numerous dealers, souvenir hunters, and vandals. Thousands of pieces of excavated pottery had been shipped from Holbrook alone, he observed, and dealers in the vicinity had extensive collections for sale. 15 Any person familiar with Petrified Forest might have added a similar statement about specimens of fossil wood.

To halt the trade and the damage it caused, Hewett recommended that the Department of the Interior employ inspectors or custodians to protect all ruins in the public domain. Further, he cited the need for legislation to create national parks and monuments and to restrict excavations of ruins, solely in the interest of science. When Hewett introduced the designation of monument, he actually added a new category of federal reserve. The precise origins of the phrase are uncertain, although Hewett obviously was thinking of a federal site that was smaller and more restricted than the familiar national parks. "If a single cliff dwelling, pueblo ruin, shrine, etc., could be declared a 'national monument' and its protection provided for," he argued, "it would cover many important cases and obviate the objections made to large reservations." 16 Like his colleagues in the antiquities movement, Hewett realized that Congress was not anxious to expand the country's neophyte park system by adding numerous small parks. The new national monument category, then, represented an alternative means to preserve and protect smaller sites. Further, the very title of national monument reflected the country's enduring quest to further buttress its cultural identity. Alfred Runte has speculated that Americans substituted the dwellings of prehistoric Indians for Greek and Roman ruins in the New World. 17

When the American Anthropological Association and the Archaeological Institute of America met jointly in 1905, Hewett had ready a draft of his bill for the protection of American antiquities and presented it to the gathering. He had wisely drawn the measure to appeal to a broad spectrum of interested parties-not only to scientists and academics but to bureaucrats and concerned citizens as well. It required the various federal departments to watch over the ruins they administered and included objects of historic and scientific interest in addition to prehistoric structures. Hewett's proposed law gave the president the power to establish national monuments by proclamation, subject only to the provision that such sites be no larger than necessary for their proper care and management. 18

On January 9, 1906, Lacey introduced Hewett's bill in the House, and Colorado's Thomas Patterson proposed the same measure in the Senate. It cleared both houses, and on June 8, Theodore Roosevelt Signed the measure, known officially as An Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities. It included the essential provision that Hewett had earlier presented to his colleagues-presidential authority to proclaim national monuments, defined as "historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest." These new monuments were to be confined to "the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected." 19

The Antiquities Act not only opened a broad range of sites for designation as national monuments; it also granted the president considerable discretion. Since congressional approval was not required, the only legal restriction was the stipulation that monuments be selected from unappropriated public domain or from land acquired as a gift from a private donor. Inclusion of sites considered to be "of scientific interest" clearly expanded the scope of the law, and in Theodore Roosevelt preservationists had a president who was inclined to interpret his authority liberally and to implement it immediately. On September 24, he established Devil's Tower in Wyoming as the country's first national monument, and on December 8, he expanded the list to include Petrified Forest, Montezuma Castle, and El Morro.

The Chalcedony Park of northeastern Arizona now became Petrified Forest National Monument, haVing met the requirements of a scientific site, at least to the satisfaction of the president. The new monument included the deposits described by Lester Frank Ward, embracing ninety-five square miles (60,776 acres) between the Puerco River and the Little Colorado. 20 For Arizonans, the monument deSignation represented the culmination of a quest begun eleven years earlier with the Territorial Legislature's Memorial NO.4. True, there would be no Petrified Forest National Park, but the Antiquities Act at least extended federal protection to a vulnerable natural site that Congress consistently had refused to consider for park status. There always was the possibility that, at a more favorable time, the monument might be raised to a national park. 21

Proponents recognized that designation as a monument afforded Petrified Forest and other sites only minimal protection. Congress had not bothered to allocate any money for the administration of the new reserves; indeed, no funds were forthcoming until after passage of the National Park Service Act a decade later. Consequently the newly created monuments languished under ad hoc administration and supervision. Often, custodians appointed by the GLO could do little more than cover the terrain with warning signs in the hope of deterring vandals and thieves.

The new law had been shaped by the desperate need to protect archaeological, historic, and scientific sites, and its authors consequently had not elaborated on the role that these monuments might play in the country's expanding park system. National parks, following precedents at Yosemite and Yellowstone, not only protected scenery and wildlife but also served as places of resort and recreation for Americans. The Antiquities Act prescribed no similar function for national monuments, although most of them attracted at least some tourists. A number of monuments, such as Zion, Bryce Canyon, and Grand Canyon, possessed sufficient scenic resources to warrant elevation to national parks in a comparatively short time.

Where this left Petrified Forest is not clear. The Santa Fe Railroad guaranteed a substantial number of visitors, and after World War I automobiles vastly expanded the number of tourists at the reserve. Because of excellent rail and highway access, Petrified Forest often attracted more people than did some of the national parks. Yet no one had considered how to convey the significance of the reserve's ancient environment to American tourists. Lacking such an interpretive plan, Petrified Forest always faced the prospect of becoming little more than a tourist attraction along the Santa Fe line and the National Old Trails Highway and its successor, Route 66.

While Congress was considering the Petrified Forest National Park bills and the various antiquities measures, the General Land Office looked for ways to protect the deposits of petrified wood. In 1900 the commissioner appointed special agent Holsinger as temporary custodian there and ordered him to place notices warning against trespassing. On a brief visit in the spring of 1903, Holsinger talked with AI Stevenson, proprietor of the recently built Forest Hotel at Adamana, hoping to determine the extent of theft from the various forests. He learned that each visitor carried off about ten to fifteen pounds of specimens. The 1902 guest register at the hotel indicated that 823 people had visited the Petrified Forest from Adamana and perhaps another hundred came from Holbrook. Based on these figures, the custodian calculated that visitors had carried away more than four and a half tons of specimens and chips that year. The figure represented only a small part of the damage, HolSinger told the commissioner. Visitors picked up specimens from the most accessible sites in the forest and thereby seriously marred its beauty. "Photography and vandalism appear here to stalk hand in hand," he lamented. "The visitor first secures a photograph and then must have a specimen from the object of the photograph." 22

Instead of hiring a resident custodian for Petrified Forest, the General Land Office resorted to appointing volunteers to serve as assistant custodians. Eventually a permanent official would take over, but in the meantime the volunteers could be given badges similar to those issued to personnel at Yellowstone and Yosemite. The solution was hardly ideal, but it was better than nothing. Otherwise, Holsinger warned, there would be no official "to stay the hand of the vandal or the greed of the specimen hunter." In the end, the combination of volunteer custodians and the agent's visits might be sufficient to reduce vandalism and theft 23

Predictably, the arrangement failed to prevent vandalism. In fact, there was no easy solution to the GW'S dilemma in the early years of the century. The country possessed a number of parks and monuments, but the Interior Department had neither a bureaucracy to oversee the reserves nor a ranger force capable of patrolling them. The national parks offered no administrative model for implementation at the monuments. When civilian officials at Yosemite and Yellowstone proved unsuccessful, for example, Washington resorted to administration by the army. But the theft and vandalism at Petrified Forest-or any other monument-did not warrant such dramatic measures.

Commissioner W. A. Richards recognized the shortcomings of the volunteer custodians; still the GLO could not spare one or two of its agents to police Petrified Forest. For the commissioner, like many others, designation of the reserve as a national park seemed to be the "only salvation," and Richards urged the Secretary of the Interior to support any legislation that would accomplish the goal 24 National parks, after all, received annual appropriations to cover the costs of administration and protection. But this remote site in northeastern Arizona seemed destined to remain a national monument, continuing from year to year under the ad hoc supervision of unpaid, untrained custodians.

By 1907, Al Stevenson was nominally in charge of Petrified Forest. When George P. Merrill of the United States Museum visited the forest, he was dismayed to find no regulations posted and visitors from Holbrook removing specimens at will. Stevenson was not to blame for the conditions, Merrill acknowledged, for he was a well-meaning individual who knew the forests thoroughly. But he had no appointment, no authority, and no salary 25 C. W. Hayes of the USGS was equally distressed by conditions a year later. Only the "more or less disinterested action of Al Stevenson" was responsible for preservation of the monument, he reported. Petrified Forest was easily accessible from the Santa Fe's stations at Adamana and Holbrook, and the railroad now was advertising the reserve extensively. Increased numbers of visitors meant more theft and damage, since the custodian could do little to prevent such activities. 26

Federal officials who visited Petrified Forest National Monument invariably praised Stevenson, recognizing that he operated with little support or authority. Hayes suggested that Stevenson be given the position of"curator," and credited his "wholesome supervision" with minimizing depredations 27 Knowing that his hotel and tours of the Petrified Forest depended on the condition of the roads, Stevenson undertook repairs and constructed two small bridges at his own expense. But these improvements brought him no favors from Washington. He received no compensation for his expenditures on roads and bridges, and when he asked for a grazing lease in 1910, the Secretary of the Interior flatly refused him. 28

Merrill returned to Petrified Forest in March of 1911 to examine the condition of the various forests and to advise the government on policy concerning excavations and collection of specimens. His visit had an additional, and more important, purpose-to determine whether the monument should be reduced in size in keeping with the restrictions of the Antiquities Act. Accompanied by AI Stevenson, Merrill spent several days going over the reserve and locating the major deposits of petrified wood. His survey convinced him that Petrified Forest ought to be reduced from its original ninety-five square miles to only about forty and a half square miles. The restricted boundaries did not exclude any major deposits, though some collections of logs were scattered about the terrain outside the monument. These were not particularly unique or likely to attract tourists, Merrill felt. And since the government was not out to corner the market on fossil logs, these inferior deposits were best left outside the monument.29

Merrill was essentially correct, although his recommendations were narrowly focused on meeting the Antiquities Act's limitations on the size of monuments. Few scientists-and virtually no politicians or bureaucrats-then defined boundaries with reference to the environment, nor did they think in terms of ecosystems. The reduced boundaries therefore included the most easily accessible and well-known deposits. First Forest, just six miles south of Adamana, includes the Agate Bridge and such sites as the Eagles' Nest, the Snow Lady, and Dewey's Cannon. Second Forest, two and a half miles farther south, covers about two thousand acres and embraces some of the largest, most colorful intact trees in the monument. And Third Forest, at the southwestern edge of the reserve some thirteen miles from Adamana, is the location of the longest whole trees, ranging up to two hundred feet in length. The fossil logs there are particularly colorful, and visitors described the area as Rainbow Forest. A smaller collection of logs called Blue Forest (now Blue Mesa) remained outside Merrill's boundary lines, as did the famous Black Forest in the Painted Desert.3o

In reducing the monument's size the Interior Department was simply adhering to the specification in the 1906 Antiquities Act that the limits of national monuments should not extend beyond the smallest area necessary for proper care and management. When Roosevelt proclaimed Petrified Forest National Monument five years earlier, the Interior Department had no idea of how much land was required to ensure the protection of the petrified wood. Initially, the government erred on the side of generosity, assuming that ninety-five square miles would be sufficient to protect the various deposits until a thorough geological survey could be made. Merrill contributed the requisite information, and on July 31, 1911, President William Howard Taft signed a proclamation reducing the monument's size to conform to his recommendations. Some of the land withdrawn from entry in 1896 and 1899 fell within the acreage now excluded by Taft, so the earlier withdrawal orders were revoked and the land opened to settlement.31

Reducing the size of Petrified Forest did nothing to stem vandalism and theft. Al Stevenson, now offiCially custodian, received one dollar per month for his efforts in behalf of the monument, but his real interest, understandably, was operating his Forest Hotel and tours of the forests. In 1907, an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 people visited Petrified Forest, and Stevenson allowed each person to carry away about eight pounds of specimens as souvenirs. Given the limited supervision, both Stevenson and the General Land Office acknowledged the futility of any prohibition against removing specimens, since such a ruling never could be enforced. The Santa Fe Railroad also contributed to the problem through its advertising, distributing a brochure that actually invited visitors to help themselves to specimens. The General Land Office objected, and the Santa Fe changed the pamphlet to include a notice about penalties-fines or imprisonment-for injuring, destroying, or appropriating petrified wood or objects of antiquity. 32

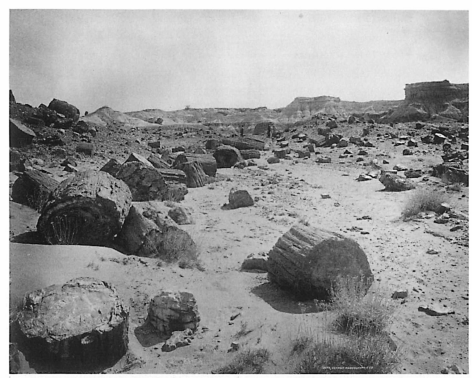

1889 photograph of Petrified Forest by William Henry Jackson (Courtesy of the Cline Library, Special Collections and Archives, Northern Arizona University)

Western railroads like the Santa Fe had supported the establishment of national parks, realizing that transporting tourists to these reserves would enhance corporate profits. The relationship between the railroads and the national parks was clearly pragmatic. Tourism was profitable in itself, and there was always the possibility that onetime visitors might return as settlers. In turn, the western lines promoted western scenery and brought the region's national parks to the attention of more Americans. The development of national parks had coincided with the marketing strategy of the railroads, Alfred Runte points out in Trains of Discovery. Following completion of the first transcontinentals, the lines worked hard to stimulate interest in the spectacular scenery of the West. As early as 1903, the Santa Fe began acquiring paintings of the Grand Canyon, Petrified Forest, and other southwestern sites to adorn its stations and executive suites. National parks and monuments that were easily accessible to the main line were the primary attractions in promotionalliterature.33

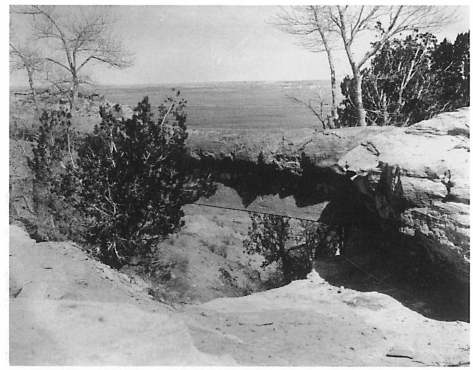

Agate Bridge. Note the concrete support that was put in place in the 19 30S. (Photograph from the J. C. Clarke collection, courtesy of the Museum of Northern Arizona)

Railroads made no secret of their economic motivation, but preservationists, including John Muir, acknowledged the value of their support. Corporate leaders may not have shared Muir's aesthetic ideals, but they nevertheless acknowledged a common goal of preservation. Railroad tourism provided parks with their economic justification, which was a vital argument in sustaining funding. The railroads' attention to parks reflected major social changes in the years around the turn of the nineteenth century. From the 1880s on, more American families enjoyed more leisure time and had more money to spend on it. This emerging mass market competed with the new rich of the East Coast and Midwest for the attention of railways and the tourist industry. Both realized that profits could accrue from serving the middle class along with their traditional, wealthier clientele.34

By 1912 the Santa Fe was advertising "stop-overs" at Petrified Forest National Monument. Since the General Land Office proVided little information about the monument, the railroad's brochure and a short article by Charles Lummis in the company's Santa Fe Magazine were among the few sources of information about the monument available to tourists. Indeed, the Santa Fe's pamphlet contained one of the few accessible, early maps of the area. The stopover at Adamana was particularly convenient; the six-hour journey was a leisurely one that left the Forest Hotel late in the morning and returned at dusk, after tourists had taken in most of the nearby sites. Those with more time could arrange to see the Second and Third Forests further south, or even journey beyond the monument boundaries to the Blue Forest or the Sigillaria Grove, both of which were recent discoveries by the naturalist John Muir.

"Today this is all yours," Lummis proclaimed. "You can sleep on a Santa Fe Pullman til time to get up. You transfer to a comfy hotel, and Stevenson shows you these pages of the past." 35 Visitors were conveyed through the forests aboard a twelve-passenger coach pulled by four horses. The route followed a natural highway, packed hard by frequent travel and blown free of sand. Tourists who took advantage of the Santa Fe stopovers at Adamana and Holbrook were assured "the unfailing joy of a wide horizon, the bluest of blue skies, and an air whose breathing is like a draught of wine." 36

Whatever the condition of the monument's "natural highway," the General Land Office could claim no credit. Although Stevenson had performed some maintenance in the monument, the GLO did not think "serious road building operations" were necessary to make the reserve accessible to most wheeled vehicles. Given Petrified Forest's location in arid northeastern Arizona, Washington officials were convinced that the land was dry and stony for most of the year and required little maintenance beyond minor grading and bridging washes. 37 Local residents knew better, and as automobiles led to greater visitation, the matter of road maintenance became nearly as aggravating as the chores of preventing vandalism and theft.

Chester B. Campbell accepted the one-dollar-a-month custodian's job in January of 1913 and also took over operation of the Forest Hotel. About 1,500 tourists had visited the First and Second Forests between July I and October 1, 1913, according to the hotel's guest register. Campbell wanted roads repaired and suggested that the government drill a well in Dry Creek between the two forests. But when he raised these points with Roy G. Mead of the General Land Office, his notions were brushed aside abruptly. 38

Lacking federal support, Campbell initiated his own construction projects, improving the old trail between First and Second Forests into an adequate wagon road and building a parallel automobile road. Over the years he installed culverts, filled sandy washes, hauled brush, and built bridges, all at his own expense. "If I have spent $ 1 .00 on the roads," he informed Horace Albright, then assistant to Stephen Mather at the Interior Department, "I have spent to date $2000." In return, Campbell wanted to lease the roads from the government, with the option for annual renewal. Primarily, he wanted to protect himself against competitors. Anyone with an automobile could convey tourists along Campbell's roads and across his bridges, benefiting from his work and expenses, and then simply abandon the endeavor when business fell off. 39

Campbell also intended to build two "sightly houses" as shelters for visitors and to pipe water from a spring near Agate Bridge. The Interior Department had no objections to the projects, so long as the spring and rest areas remained free and unrestricted to all visitors. But the department could not lease the roads to Campbell or to anyone else. A complaint to Stephen Mather at the Interior Department brought no results, so Campbell acquiesced and contented himself with the growing number of visitors who stayed at his hotel and booked tours in his vehicles. About 5,700 people visited the monument in 1915, and he anticipated a substantial increase the following year. 40

While Campbell battled with the Interior Department over roads, bridges, and repairs to the Agate Bridge, substantial administrative changes were occurring in Washington as a result of the passage of the National Park Service Act of 1916. The law created a new agency, the Park Service, which acquired title to all national parks and monuments administered by the Department of the Interior. More important, it was empowered to promote and regulate the use of these diverse reserves.

What this new agency promised for Petrified Forest was not at all clear, though Campbell could hope for improvements over the limited attention his monument had received in past. By 1916 Petrified Forest was one of twenty-one national monuments administered by the Interior Department (another dozen fell under the authority of the Forest Service, and two were run by the War Department), and even after President Taft had reduced its size to forty and a half square miles, it remained among the largest of such reserves. Further, its close proximity to the Santa Fe line at Adamana guaranteed it a growing number of visitors, and Campbell could only guess how many more visitors would be arriving by automobile. Measured by the conditions in 1916, the future could only be better. In that year, each monument had only $166 to cover its costs. The entire National Park Service budget was only $30,000. In the words of one writer, "the Park Service was barely operational." 41