The beginning of the 11th century witnessed a renewal of interest in the apostolic life within cathedral chapters. In Old Catalonia, the restoration of diocesan jurisdiction that had been lost since the Muslim Conquest brought with it the revival of a communal life under a rule. These rules included not only the various versions of that approved by the Council of Aachen, but also miscellaneous rules drawn from a variety of patristic texts – known collectively as the Rules of the Holy Fathers – some of which have clear Iberian origins. Bishops Aeci of Barcelona (995–1010), Oliba of Vic (1017–46), Pere of Girona (1010–50) and Ermengol of Urgell (1010–35) attempted to restore communal life in their cathedrals.1

What prompted these peninsular bishops to reorganize the life of the cathedral community, in some cases stipulating for the first time that both canons and bishops should live communally? To my mind, the revitalisation of communal life that took place in Barcelona, Girona and Urgell was a direct response to the progressive relaxation in clerical lifestyle that had taken place in the ancient sees of Old Catalonia. This 11th-century reform initiated a cyclical pattern of rigour and relaxation that culminated in the definitive secularisation of cathedral chapters between the 13th and 16th centuries. In the immediate aftermath of reconquest, cathedral chapters were reorganised as part of a larger movement of urban replanning and renewal. By the start of the 11th century, the progressive relaxation of the customs of communal life prompted a structural reform of cathedral chapters. Between the 11th and 12th centuries, communal life decayed yet again, until, by the middle of the 12th century, we find the first references to cathedral chapters organised secundum regulam Sancti Augustini. This last coincided with the restoration of the sees of Lleida, Tortosa and Tarragona in southern Catalonia.

These institutional reforms had direct consequences for the physical fabric of cathedrals themselves. In Girona, the bishop and chapter decided in 1019 to build a domus canonice, destined for the regular life of the canons, referred to since the first half of the 11th century interchangeably as clericis or canonicis (Figure 4.1).2 Bishop Aeci of Barcelona did the same in 1009, when the claustra, located next to the cathedral, and the buildings constructed within it, were given over to the canons’ communal life. Meanwhile, in Seu d’Urgell, the sainted Bishop Ermengol restructured the cathedral chapter in 1010, thus continuing the reforms undertaken by his predecessor Salla, as is recorded in the surviving documentation.

All of these new architectural ensembles had their origins in much earlier structures, which we can date to around the 7th century thanks to documentary evidence that alludes to these cathedrals before their 11th-century reconstruction. Miquel dels Sants Gros has used the extant group of churches in Terrassa in order to reconstruct a series of buildings that no longer survive, but whose presence is attested in documentary sources. Thus, we can consider the cathedrals of Vic, Seu d’Urgell and Girona, together with the churches of Terrassa, within a larger European context. Working from later documentation that details the 10th-century restoration of the group of three churches in Terrassa, Gros has analysed the function of two, concluding that Sant Pere acted as a parish church, while Santa María served the clergy (colour plate I).3

The third church in this group poses problems. A centrally-planned church dedicated to St Michael, the lack of documentary sources or archaeological investigation of this site led the architect in charge of its restoration, Josep Puig i Cadafalch, to interpret the building as a baptistery.4 This reinterpretation of the third church of Terrassa effectively brought the ecclesiastical complex into line with other early medieval sites. Intense archaeological work at the end of the 20th century, however, has resulted in a radical revision of Puig i Cadafalch’s baptistery.5 In summary, there had been a basilica dedicated to the Virgin Mary on the site from the 5th century. This building was enlarged and given an adjoining baptistery. In the 6th century, two more churches were built to the north of the main basilica. The centrally-planned church of St Michael, decorated on three sides with a colonnaded porch, clearly had a funerary function, while the third church, dedicated to St Peter, functioned as the parish church. All three churches were connected by liturgical celebrations, and were enclosed by a common wall which encompassed their graveyards and the bishop’s residential quarters at the southeastern corner of the complex. Finally, another funerary complex, interpreted as an episcopal chapel dedicated to Saints Justus and Pastor, has been identified along the southern flank of the church of Santa María.

From the 9th century, we have evidence of a group of four churches in the town of Elne, dedicated to saints Peter, Mary, Eulalia and Stephen, the last of which may have had a funerary function. The church of St Peter was long considered the first cathedral in the lower part of the town, before it was moved to the upper part at an unknown later date. St Eulalia took over the functions of the cathedral, and the church of St Stephen stood alongside the apse of St Eulalia until the 18th century.6 The pre-11th-century cathedral of Vic offers an interesting puzzle. There is clear evidence of a cathedral complex dating from the 9th century, which consisted of three churches and two unique dedications. A donation by the Frankish king Eudes in 889 indicates that there was a church built in honour of the Virgin and St Peter.7 The double dedication is unremarkable for this period, but in 947 we have a reference to construction works at the church of St Peter. A few years later in 952 and again in 981, two donations refer clearly to two separate churches in the city of Vic: one dedicated to St Peter and the other to the Virgin.8 Moreover, the First Martyrology of the cathedral refers to the feast of the dedication of the church of Santa María in the 10th century.9 The evidence thus complicates our ability to distinguish which of these two churches functioned as the cathedral church, and which functioned as the conventual church, perhaps for the exclusive use of the cathedral’s lesser clergy. When the cathedral complex was rebuilt in the 11th century, both these functions were brought together in the church of St Peter, while the new church dedicated to the Virgin raises other issues, as we shall see. By the middle of the 11th century, there are no more documentary references to the double dedication to St Peter and the Virgin. From this moment on, documents refer to a sole foundation dedicated St Peter.

The third church in the ecclesiastical complex of Vic was dedicated to St Michael Archangel. The church of St Michael seems to have been located along the southern flank of St Peter, near the current location of the cloister. Its origins date back to the 10th-century episcopacy of Guadamir (948–57), and one of the cathedral martyrologies refers to the dedication of the church of St Michael during this time.10 At the start of the 11th century, the church was still the beneficiary of a bequest pro edificio suo, and Bishop Borrell was buried in its crypt in 1017. But these three churches – St Peter, Santa María and St Michael – were not the only ones in the cathedral complex of Vic. A 985 donation refers to five separate foundations, including St Peter and four others that were ‘subject’ to it: the foundations of Santa María and St Michael that we just discussed, as well as two others dedicated to John the Baptist and St Felix.11 Eduard Junyent has suggested that these dedications should be understood as references to spaces within the interior of the church of St Peter, perhaps as chapels associated with a hypothetical tripartite apse, consecrated on the 19th of May at some point in the middle of the 10th century.12 But, what more can we say about these two dedications to John the Baptist and St Felix? Surviving documentation suggests that we are dealing in Vic with a possible baptistery dedicated to John the Baptist and a relic deposit dedicated to St Felix, both of which would have been located near the apse of Sant Peter. A parallel to this arrangement is the Visigothic cathedral of Valencia, which also had a baptistery and a martyrium dedicated to St Vincent, located on either side of the presbytery.13 While the arrangement proposed for Vic is certainly plausible, for the moment we do not have enough archaeological evidence to be certain. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the chapels of the Romanesque transept were dedicated to John the Baptist and Paul (north), and Felix and Michael (south), thereby incorporating dedications from before the episcopacy of Oliba into the fabric of the cathedral.

In Girona, the Cathedral of Santa María had a space dedicated to St Michael, in which the cathedral clergy were supposed to pray in memory of Count Borrell II of Barcelona. Scholars have assumed this to be a separate space, independent of the old cathedral of Girona, even identifying it with archaeological remains uncovered in the northwestern corner of the cathedral cloister. I would like to counter this prevailing interpretation. Documentary sources are decidedly laconic with respect to the space dedicated to St Michael, infra domum sancte Marie sedis Gerunde. Not only do these sources fail to make clear whether or not we are dealing with an independent architectural space, they even suggest that we might interpret the dedication as that of an altar or chapel located in the interior of the main church, something which does, in fact, figure in later documentation.14

In Barcelona, mention of a cathedral dedicated to the Holy Cross and St Eulalia might lead us towards an interpretation similar to that which we have proposed for Girona (colour plate II). However, the translation of the body of St Eulalia in 878 from the church of Santa María into the cathedral tells us that the dedication to Eulalia involved not the ad hoc construction of a new building, but rather the installation of a new saint in the existing cathedral, and the subsequent rededication of the building. Similarly, Francesca Español has interpreted documentary references to a church of the Holy Sepulchre, located near the western façade of the cathedral, as indicating not an independent structure but rather a space associated with the western portion of the cathedral, as we find in Vic and Girona. The architectural form of this space was liturgically conditioned, and thus we see that the tower above the Holy Sepulchre in the Romanesque cathedral was also contemplated in the Gothic project for a monumental western ciborium. The organisation of space in Barcelona was therefore akin to that proposed by Carol Heitz for the Abbey of Centula, which had a similar structure located at the western ‘foot’ of the church, transformed during the late Gothic period into an antechamber with a central tower.15 A curious cruciform church that has been identified among the chaotic remains of the northeastern part of the cathedral complex presents even more problems.16 There is much that remains unknown about the form this building took, but tombs found in its vicinity suggest that the area around the putative church had a funerary function. What is clear is that the dedication to the Holy Sepulchre in Barcelona dates back to an early period. If documentary references to the structure in the western façade of the cathedral go back no earlier than the late 12th century, perhaps we are dealing with a process involving the integration of separate structures into the body of the cathedral, such as we have outlined in Vic. Finally, from the 10th century, there are references to churches dedicated to Mary and Peter, as well as a possible baptistery dedicated to John, in Seu d’Urgell. This complex of churches was radically reconfigured in the 11th century, as we shall see.

Returning to the 11th-century period of institutional and architectural renewal with which we began, we see that the figure of Bishop Oliba of Vic has traditionally been credited with a decisive role in the renewal that swept through the sees of Old Catalonia, as well as many of its monasteries. However, these renewals were not exclusively dependent on his individual agency, as the cases of Vic, Ripoll and Sant Pere de Rodes indicate.

Let us review each of these cases of reform. In Barcelona in the year 1009, Bishop Aeci granted his recently reformed chapter the claustrum situated between the cathedral and the episcopal palace. According to documentary descriptions, this claustrum was surrounded by a wall made of stones and lime, filled with fruit trees and a vineyard, within which was the refectory, still under construction in the early 11th century.17 Matters are complex in Barcelona. The reinterpretation of the archaeological remains uncovered near the northern flank of the cathedral have led some to conclude that the palace of Barcelona’s bishops was located here until the 12th century (colour plate II), even identifying the monumental late antique remains still visible beneath the floor of the city’s museum as this episcopal palace. According to proponents of this view, the palace was moved to the southern side of the cathedral complex in the 12th century, but the earlier site remained episcopal property until the start of the 14th century, when the remains of the old building were granted by Bishop Pons de Gualba (1303–34) to King Jaime II in order to expand the neighbouring royal palace.18 This hypothesis, suggested long ago by the classic historians of the see of Barcelona, has been taken up again by contemporary scholars. The details of the 14th century grant do not, however, support this interpretation. While the document describes how Bishop Pons de Gualba donated a house to the king so that he could expand the royal palace, the house in question was simply episcopal property, not the episcopal palace itself. Indeed, an earlier document of 1271 refers to the great possessions of the bishops next to the cathedral and the royal palace.19 If we bear in mind that most of the houses that surrounded the cathedral were the property of the bishop and canons, the bishop’s 14th-century donation becomes simply the sale of a house in his possession rather than the sale of his old palace. On the other hand, as the early eleventh-century document of Bishop Aeci suggests, the bishop of Barcelona’s residence was already located near the south flank of the cathedral by 1009. The claustrum donated by Bishop Aeci to his chapter was the same space in which a cloister was subsequently built, and the episocopal palace appears in this document in the same location where it stands today.

Meanwhile, the construction of the Romanesque cathedral must have been carried out with full awareness of the important cult centred on the relics of St Eulalia. During the construction of the new Romanesque cathedral, St Eulalia’s funerary monument was installed alongside the main altar of the Virgin Mary. Early sources tell us that the altar that accompanied the tomb monument was used for the celebration of the morning mass, the early office that, like Matins and other Marian and funerary offices, was carried out by those who could not attend the main mass owing to other obligations.20 However, the surviving portions of the cathedral ordinary indicate that the morning mass was celebrated at the high altar, dedicated to the Holy Cross, which is exceptional in the context of cathedral liturgies more generally ‘Non dicitur per ebdomadari missa in altari Sancte Eulalie … dicantur missa matutinalis in altari Sancte Crucis sub missa uoce cum diachono et subdiachono’.21 Pope Clement VII (1523–34) granted indulgences to those who visited the tomb of St Eulalia for Saturday morning mass, along with the offices for the Virgin that were celebrated there, as well.22 Although they refer to the Gothic cathedral, these later texts are valuable because they emphasize the close relationship between the matutinal altar, the nearby high altar and the presbytery. It is worth noting that it was common to find the matutinal altar immediately behind the high altar. This was an ideal space for the tombs of saints, creating a retro-chapel for the celebration of matutinal masses and the elaboration of the cult of important relics.23 This appears to have been the model chosen for the Cathedral of Barcelona. In Barcelona, the apse was centred around two altars, the main altar dedicated to the Holy Cross and the matutinal altar dedicated to the Virgin Mary, while the tomb of St Eulalia occupied the area closest to the curve of the apse. On the south side was the seating area for the officiant and his ministers, next to the bishop’s cathedra. In front of this area was the canons’ choir, surrounding the altar, as we see in Vic, Girona, Roda de Isábena, Lleida and Zaragoza, among others.24

In Vic, the new Cathedral of Sant Pere was consecrated on 31 August 1038. Santa María, which may have functioned as a conventual church, was incorporated into the fabric of the new cathedral complex, taking the form of a large rotunda dedicated to a commemorative cult of the Virgin Mary (Figure 4.2). It is precisely this commemorative function, here to the Nativity in Bethlehem, that shapes the architectural form of the church of Santa María of Vic, which was reconstructed as a centrally-planned building alongside the western façade of the Cathedral of Sant Pere. Though the rotunda was destroyed in the 18th century, thanks to archaeological excavations we have a sense of the 11th-century situation of the building within the larger cathedral complex during the celebrated episcopacy of Oliba (1018–46).25 Oliba’s church of Santa María had a circular plan some ten and a half metres in diameter, and a western apse. This building was then reconstructed in the mid-12th-century, leaving a large circular church that was destroyed in the modern era.26 The construction at Vic was contemporaneous with the extension of the monastic church of Sant Miquel de Cuixà, in particular its western rotunda. This architectural similarity makes even more sense when we bear in mind the close liturgical relationship between the principal cathedral church of Sant Pere and Santa María at Vic which, although documented in liturgical texts from the 13th century, can easily be pushed back in time to earlier centuries.27 We may suppose that processions at Cuixà were similar.

In Seu d’Urgell, the capitular buildings were constructed in an L-shaped plan, to the south-east of the original cathedral. During the episcopacy of Ermengol, Seu d’Urgell became the most significant – and the most recently reconstructed – ecclesiastical complex for the old Catalan counts. Its reconstruction, dating from the early 11th century, maintained two main churches, to which was added the third church of Sant Miquel (conceived as a church for the minor canons) and two small churches dedicated to the Holy Sepulchre and to St Eulalia (Figure 4.3). As we see with St Michael at Fulda, the Holy Sepulchres of Cambrai and Paderborn, or with St Maurice in Constance, the Holy Sepulchre at Seu d’Urgell was constructed at the initiative of a private individual (a certain Miró Viven) for his own personal funerary purposes. From this point on, the churches formed an integrated complex organised around spaces and dedications related to pilgrimage: St Peter’s in Rome, the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, St Eulalia in Barcelona and St Michael at Monte Gargano. The sites were all connected by liturgical routes to the main church dedicated to the Virgin Mary.28

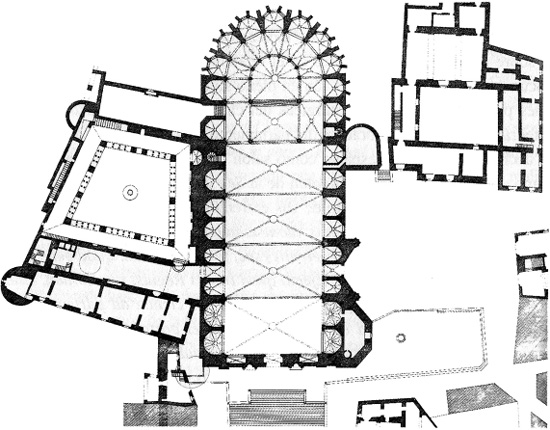

In the cases of Seu d’Urgell and Vic, we encounter a phenomenon of reconstruction that seems to build upon a pre-existing arrangement of ecclesiastical buildings within the overall topography of a cathedral complex. This phenomenon is documented in all of the sees from an early date, while material testimony still survives in the old cathedral of Terrassa. The model followed for the reconstruction of these sees involved the integration into a single building of dedications that seem to have once been independent structures. Such is the case with the dedication to the Holy Sepulchre in Barcelona. Strangely, during the 13th and 14th centuries, the Cathedral of Barcelona underwent a process of fragmentation, whereby cult spaces metamorphosed into independent chapels surrounding the perimeter of the cathedral (Figure 4.4).29 This process seems to have been born out of the communal life of the chapter and out of the need to bring into a single building several diverse functions. These included the needs of the chapter, and the parochial function of the bishop’s church, as well as a variety of smaller funerary churches, baptisteries or commemorative buildings. As Carol Heitz has shown, the period before the 12th century saw the progressive integration into a single building of cult spaces that had previously been distributed throughout the cathedral complex. This brought with it the articulation of the interior space into areas reserved for the clergy and for the laity, the latter becoming the site for processions that before had connected the distinct architectural spaces of the cathedral precinct.30

In conclusion, let me leave you with a final thought. Only thirty years separate the reforms of the chapter of Barcelona from those at Seu d’Urgell. During this brief period, four bishops reorganised their chapters and reconstructed their cathedrals. We are clearly dealing with a time of widespread reform, and Oliba of Vic was far from the only protagonist in this story. Three other bishops participated in the reform process, and the documentary, art-historical and archaeological records reveal a monumental landscape far different from the fragmented geography of cult sites that we see in Terrassa or at other pre-reform sees. Only Seu d’Urgell seems to conserve a distribution of sacred sites more in accordance with earlier models of urban organisation, with a cathedral complex consisting of a central main church, Santa María, surrounded by four smaller churches. A glance at the dedications of this second complex of Urgell makes clear its dependence on and relationship to the most important cult and pilgrimage sites of medieval Europe. Along with the Cathedral dedication to the Virgin Mary, there is the church of Saints Peter, Paul and Andrew, a church dedicated to St Michael and the Archangels, another to St Eulalia of Barcelona, and finally a dedication to the Holy Sepulchre. Josep Guidiol’s foundational study of Catalan pilgrimage to the holy places emphasizes the dedications we find at Seu d’Urgell: Jerusalem and its Holy Sepulchre, Rome – particularly the basilicas of St Peter and St Paul – St Michael on Monte Gargano.31 When the tiny church of the Holy Sepulchre was founded in Seu d’Urgell, Jerusalem was still in Muslim hands. Was the construction of this Catalan version of the Holy Sepulchre, like so many other versions of this monument, a response to the difficulties of pilgrimage to the Holy Land? It would be remarkable if a visit to the churches of Urgell counted as a pilgrimage, as we see documented in papal bulls relating to the Christian recapture of the city of Tarragona (because the reconquest of the Iberian peninsula was also cast in terms of a crusade), or in the beautiful 1080 diploma of consecration for the church of Tolba. Visits to Tolba and donations of alms commuted the pilgrimage to the Holy Land, St Peter’s in Rome, Santiago de Compostela, the Church of the Virgin Mary in Le Puy, uel in aliam peregrinationem.32 Among the dedications to St Peter, St Michael and the Archangels, the Holy Sepulchre and St Eulalia, the absence of the dedication to Santiago among the churches of Urgell stands out. We do, however, have numerous testimonies of pilgrims to Santiago from Urgell, including Bishop Ermengol himself. At the same time, one of the altars in the Romanesque cathedral was dedicated to the Apostle James, while the meteoric rise of cult of Ermengol immediately following his death was also linked to the cult of St James. This connection to St James was made clear in both the topography of the cathedral, with its neighbouring altars, and in the iconography associated with the sainted bishop, replete with references to the legendary hagiography of James.33

Reflecting on the complex of dedications and their relationship to pilgrimage, early 11th-century Seu d’Urgell could be seen as a symbolic mappa mundi of the most important devotional centres of the time. If we again consider the question of atria, terra ad cibarium, and the urban landscape, we must imagine a principal church dedicated to the Virgin Mary set within a defined space, perhaps surrounded by a wall, around which were located four churches whose dedications are profoundly indicative of the contemporary religious imagination. At the same time that they demonstrate the desire to bring together the most important sacred spaces of the time. During this same period, another ecclesiastic, Bishop Oliba of Vic, was behind the creation of two of the most striking and evocative buildings of the age: the Marian rotundas at the west ends of the churches of St Michael in Cuixà and St Peter in Vic, both of them noteworthy for their commemorative function. Similarly, within a few years, chapels dedicated to the Holy Sepulchre were created for the upper story of the west ends of the cathedrals of Barcelona, Girona and Vic. In these circumstances is it so very difficult to imagine an urban topography of sacred spaces, focussed on the cathedral and its immediate vicinity at Seu d’Urgell? Most, though not all, the separate cult sites at Urgell were finally integrated into the main body of the cathedral during the 12th and 13th centuries, thereby vitiating the unique sacred topography of the 11th century. But whether accidental or not, the built environment of the Cathedral of the Virgin Mary in Seu d’Urgell consisted of an ensemble of churches dedicated to the Holy Places, linked via a complex stational liturgy which, although altered and transformed, survived until the beginning of the Early Modern period.