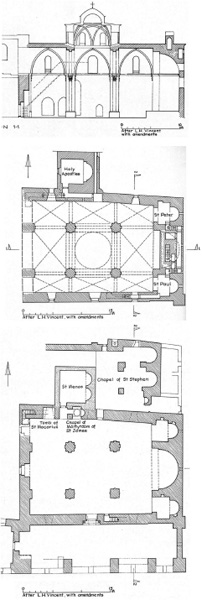

Figure 8.1

Jerusalem: Saints James Cathedral, plans and section (after Pringle)

The Cathedral of Saints James in Jerusalem (Սրբոց Յակոբեանց Վանք Հայոց in Armenian) belongs to the Armenian Church and is one of the most venerated churches in the Holy Land (Figure 8.1).1 It is the principal church of the monastery of the same name, as well as acting as the cathedral of the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem. It occupies a significant part of the Armenian Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem, and is bounded to its west by the street of the Armenian Orthodox Patriarchate (known in the middle ages as the street of Mount Sion), which in turn connects the Jaffa and Sion Gates. A monastery shares the cathedral precinct, along with the residence of the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem, a number of household buildings, a library and educational institutions.

According to tradition, the Cathedral of Saints James is the burial place of the ‘brother of Christ’, James the Just, and the place where the Apostle James the Great (son of Zebedee) was decapitated and where his head was buried – hence the plural Saints James of the dedication. The site also houses a tomb of Macarius, Bishop of Jerusalem (314–33).2 The first actual building to have been created here is believed to be the Chapel of St Menas, adjacent to the cathedral on the north, founded by a patrician woman named Bassa in 444.3 Also in the 5th century we hear that the dean of the cathedral was an Armenian priest, Andreas Melitenetsi.

The construction of the cathedral is not mentioned in surviving written sources, though there is an account of the then relatively new church given by the German pilgrim John of Würzburg (c. 1162–65): ‘In the same place, not far from monastery of St Sabas … a large church [was] built in honour of St James the Great, where Armenian monks live and have a large hospital for bringing together the poor of their nation. There also the head of the same Apostle is held in great veneration: for he was decapitated by Herod, and his disciples took his body by divine providence to Galicia in the kingdom of Spain, having placed it on board of a ship in Jaffa, while his head remained in Palestine. The same head is still shown in that church to visiting pilgrims.’4 Numerous later pilgrim accounts prove that the cathedral was always Armenian, in spite of arguments to the contrary by Greeks and Georgians. In the 18th century, especially, there were claims that the monastery of Saints James had originated with and initially belonged to the Georgian Church.5

To understand the current state of the cathedral, written sources on the extensive restoration of the church and monastery during the patriarchate of Gregory the Chain-Bearer (1715–49) are of great importance.6 An inscription records repairs to the cupola in 1812, while work was also undertaken after the earthquake that struck Jerusalem on 23 May 1834.7 For these later repairs there is an account by the Greek monk Neophytos of Cyprus: ‘The Armenians surpassed [the Latins and the Greeks] in the question of building. They built on very solid foundations a new narthex to the church of St James and joined it to the Church; by other additions they made an enclosure for the women. The church was thereby greatly enlarged. The cupola of the Church was formerly open and covered with glass like the Baths, but now they finished it off in stone. The windows of the cupola were previously closed, like those of the Katholikon [in the Holy Sepulchre], and these were now opened. They painted the church and decorated it with many pictures.’8

As Nurith Kenaan-Kedar remarked in her study of Armenian architecture in Jerusalem, the cathedral of Saints James ‘has never been systematically studied as an individual architectural project’.9 The following study doesn’t materially change this, but it examines the building in relation to its probable patron and in the light of the importance of medieval Jerusalem as a meeting place of cultural traditions.10

A number of scholars have already suggested that the cathedral was constructed during the reign and with the encouragement of Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem (1131–61).11 Claude Mutafian notes the warm reception given to the Armenian Catholicos Grigor III Pahlavuni in Jerusalem in April 1141.12 For Denys Pringle this visit of the Armenian Catholicos to attend a synod held in the church of Mount Sion involving the Latin Patriarch, William I, the papal legate, Alberic, bishop of Ostia, William of Tyre and others, was probably the ‘spur for the Armenian rebuilding of the cathedral church of St James, which must have been well advanced by the time that King Toros II visited King Amalric in Jerusalem around 1163’.13 Folda felt that ‘in the context of amicable relations and with the special interest of the queen [Melisende]’, the church was erected in the 1140s, adding that as a patron of church construction in Jerusalem in the mid-12th-century, Melisende was in a position to persuade masons who had worked at the Holy Sepulchre into working on Saints James Cathedral.14 Nurith Kenaan-Kedar also argued for Melisende as a donor to both Catholic and Armenian churches.15

If Melisende was the patron, what of the architecture? Kenaan-Kedar thought the masons like the architecture were Armenian, an opinion shared by Claude Mutafian, who saw the building as typically Armenian, and compared it to a number of 12th-century churches in Armenia.16 However, as Denys Pringle has observed, the matter is not quite so straightforward. Pringle makes the important archaeological point that the piers and arches of the original 12th-century narthex ‘bear the diagonal dressing and masonry marks typical of twelfth-century Frankish workmanship’.17 Pringle concludes, ‘While the layout of the building was evidently dictated by the requirements of the Armenian liturgy, the masonry marks on the south façade, the style of the capitals and south doorway, and the form of the vaulting all suggest a heavy involvement of Frankish masons in its construction.’18

I shall propose that earlier evaluations of Saints James Cathedral as a church that mixes Cilician (or wider West Armenian) and Romanesque architectural styles in a creative and purposeful manner well represents the building.19 But what can we say about the role of Queen Melisende in its construction? There is no direct evidence for her participation. However, Mutafian’s proposal that work on a new cathedral of Saints James could have been precipitated by the visit of the Catholicos Grigor III Pahlavuni to Jerusalem, and that both Melisende and he could be regarded as the primary patrons and initiators seems entirely plausible.20 Such a magnificent church as St. James is unlikely to have been begun without the approval of the Catholicos, while the (probable) engagement of stonemasons from the Holy Sepulchre is unlikely to have been initiated without the Queen’s support.

My conclusions are preliminary, in large part because study of the 12th-century fabric is compromised by the prevalence of late and post-medieval decoration (Figure 8.2). The lower parts of the walls are covered by ornamental glazed tiles (1727–37) from Kütahya in Asia Minor (a city famous for the production of painted faience).21 Above this level, up to the level of the capitals, the walls are covered by two tiers of oil paintings on canvas, dating from the 18th and 19th centuries. The arches and vaults are plastered and white-washed. The mosaic floor dates to 1651. The altar has been moved to the space beneath the cupola and enclosed within an openwork grating where it supports an icon of Virgin and Child. The apse thus revealed is decorated in exquisite oriental style, though the lower section of the wall is covered by a blind arcade made up of carved marble slabs (1727–37), inside the frames of which are depicted bunches of flowers. Entrances to the chapels are through double-valve doors inlaid with wood and ivory of 1371. The altar zone and the space beneath the cupola, along with many of the lateral wall surfaces, are resplendent with numerous silver lamps, chandeliers and large porcelain eggs suspended from chains on which are painted figurative and ornamental designs along with dedicatory inscriptions. These are part of a larger tradition for the decoration of shrines, entirely typical for Armenians in Jerusalem.

As such, we cannot see the original internal surfaces of the building. This circumstance, taken with the absence of a full-scale archaeological study, has obviously hindered research.22

The cathedral consists of a spacious, slightly elongated four-pillar hall with three apses to the east. It is fully vaulted, with a dome supported on four arches over the central bay, and groin vaults around this central core (Figure 8.3). Overall the church measures 28 m from east to west and between 18 and 20 m north to south (excluding the narthex). The central bay is a square with sides of 6.40 m.23 The aisles are appreciably narrower than the central nave, and that to the north is irregular and tapers towards the east, narrowing by 1.20 metres from west to east.24 The groin vaults over the nave bays are square while those over the aisle are approximately rectangular. The triapsidal east end (the altar zone) is contained within a solid masonry block, meaning the apses are square on the exterior and semi-circular on their inner surfaces. The block includes the principal apse, with a narrow bema flanked by two small apsidal pastophoria. Initially, these lateral chambers were open to the aisles, though the relatively low arches at the aisle ends allowed for small upper chapels to be created, reached through a narrow passage in the thickness of the south aisle wall that begins at a door in the central bay of the south aisle.25 The principal entrance to the church was through a sculpted portal that brought one into the middle of the south aisle. This portal was sheltered within a narthex that ran the length of the church, originally open to the street through four arches, but in 1666 it was walled in to create the Etchmiadzin Chapel. Pringle speculated that, prior to the 17th century, there may have been an altar at the east end of the narthex, and that the space may have been used for baptisms from an early date.26 If this were so, we would suggest that the baptismal niche to the left of the altar space also dates from the 12th century. Creating a baptismal niche in the northern wall of the church, close to the altar, is common in Armenian churches from as early as the 4th century.27

The most interesting and unusual feature of the building is the deployment of a type of dome, or cupola, set above an annular cornice that in turn sits over the pendentive crossing (Figure 8.4).28 Fundamental to this composition are six arches that intersect to form a six-rayed star with a hexagon at its centre. A small dome appears over the hexagon, bounded by the intersecting arches. Given the way that the six arches intersect, twelve triangular severies are created outside the central hexagon, each one of which is covered by a flat ceiling (and roof). Those triangular compartments that are located in the points of the star (six in total) are decorated with ornamental cones in relief, perhaps intended to symbolise celestial bodies, while the shallower triangular compartments which sit between the points are left plain and open onto six large windows set into the drum. This whole complex composition is in turn contained within a drum, or tholobate, which rises to the height of the springing of the inner dome.

From the exterior, the drum is articulated by a blind arcade, divided into 24 parts. There is one smaller dome above this structure, corresponding to the inner cupola and topped by a modern roof. The windows of the drum are inscribed within six arches that are taller than the blind arcades and rise to an ogee head. However, the window arch mouldings differ from those of the blind arches, which they cut into just above springing level (Figure 8.5). The latter peculiarity makes it clear that the window heads post-date the blind arches. However, there is currently no concensus on the overall architectural evolution and date of the present drum and dome. Following Vincent and Abel, Pringle is disinclined to date the current internal arrangements to the time of the building of the church. He interprets a note on the renovation of the dome in 1812 as suggesting the intersecting arches were built at this date; at the same time, he hints at the possibility that the small inner dome was only added in the 1830s, after the earthquake. While noting that similarly elaborate cupolas can be found in medieval Armenian architecture, as well as in Spain, Pringle follows earlier European archaeologists in expressing doubt over the issue. ‘If the dome of St James’s could indeed be shown to be twelfth century, the latter [earlier Armenian vaults] would perhaps offer the most plausible source of inspiration, though it also seems possible that it is an antiquarian creation of the early modern period.’29

Taking the question of the date of the small inner dome first, it does indeed seem likely that this was created after the earthquake of 1834. That there was originally a single opening in some sort of tower-like central structure is mentioned in the accounts of numerous pilgrims. The earliest is that of John Poloner in the early-15th-century. ‘In the middle, it [the Armenian church] has four square columns. It has no windows, except for a rounded glass one at its highest point, but has 300 or more lamps.’30 And Anselm Adorno described the building as ‘a most beautiful church having a tower carried at its highest point, rounded and with a broad aperture’.31 Finally, the cathedral is undoubtedly represented in a manuscript of 1726 from Ottoman Galiopoli now in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. Here one sees the cathedral’s flat roof, with a blind arcade articulating the drum and an oculus marking its ‘dome’ (Figure 8.6).32 Thus, it seems reasonably clear that the original upper oculus was closed after 1834 to be replaced by a dome, and that this is the most likely date at which six windows were cut into the drum. However, there is no reason to suppose that alterations were made to the intersecting arches at the same time. Although the drum can only be inspected at close quarters from the exterior, and the interior is anyway coated in post-medieval plaster and paint, our preliminary conclusion is that the internal arrangement of intersecting arches, together with the cylindrical drum and external blind arcading all date from the middle of the 12th century.

The plan of the cathedral draws on a type of four-columned cross-domed church that was well-established in the eastern Mediterranean and can be found in both Armenian and Byzantine traditions. The fact that the lateral pastophoria were open to the nave brings the building closer to Byzantine churches, but the existence of chapels above these and the use of compound piers rather than columns in the main elevation are entirely characteristic of medieval Armenian churches. In the 11th and 12th centuries churches in Armenia were aisleless, and employed compound responds (the only exception to this is Ani Cathedral of the last quarter of the 10th century). However, the plans of numerous, mostly ruined, Armenian churches in the Cilician Armenian kingdom, and cities to the east and south of it, differ from those of the Armenian Highlands. A now ruined and probably 12th-century church in Cilician Anazarva (Anavarza, Turkey) is a good example. This was aisled, with tall side apses open to the aisles and an overall plan firmly contained within a rectangular outline – all features found in the Armenian Cathedral of Saints James in Jerusalem. As with Anazarva, most surviving Armenian churches in Cilicia are striking in the way they adapt long-standing Armenian traditions into an essentially Byzantine context.

That is why, when one discusses the Armenian sources of the architecture of Saints James in Jerusalem, the Mediterranean-Armenian tradition is important. Links between the creative centres of Great Armenia and the architecture of the Cilician Armenian kingdom were weak, while the architecture of Armenian Cilicia was more or less completely integrated into the architectural culture of the Middle East. Comparisons of the imposts, cornices and archivolts of the Cathedral of Saints James with those of a Cilician Armenian church, such as that in the fortress of Anavarza, alongside 10th-to-13th-century monuments in the Armenian Highlands, reveals a much greater similarity between Jerusalem and Anavarza than to those of Highland Armenia.

If we then move away from the ground-plan and look instead at the upper levels of the cathedral, we are easily reminded of another cultural sphere – one much closer to a western European architectural environment – that of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. The vaults, for example, are supported on pointed arches, carried on simplified Corinthian capitals of a sort widely used in Romanesque churches. And while at first sight the compound piers used at Jerusalem are not unlike those used in Greater Armenia more generally, as at Ani Cathedral (Figure 8.7), the particular form of the piers, as well as the type of hollow chamfer used for the imposts and continued as a stringcourse around the base of the apses, seems to belong to the Romanesque tradition. Among surviving churches of Jerusalem, similar forms can be found in the Holy Sepulchre and in the mid-12th-century church of St Anne by the pools of Bethesda.33 The common springing point for both the arches and the groin vaults, excluding the central cupola bay, was also typical for the most part of Romanesque churches – both basilican and centrally-planned. Four-column churches built or reconstructed in Jerusalem under the Crusaders differed from Byzantine four-column churches. Beside the cathedral of Saints James, the chapel of St Helen in the Holy Sepulchre complex (which also now belongs to the Armenian Church) similarly springs groin vaults over the lateral bays from the same level as the pointed arches, and maintains a consistent height across the aisle bays.34 Earlier four-pillar churches in the eastern Mediterranean had conceived the type as a centrally-planned cross-domed church with four tall vaulted arms inside a square. Before moving on it may be worth pointing out that there is one type of building, represented by the probably late-11th-century church of San Vittore alle Chiuse (Marche, Italy).35 That arguably sits between Byzantine cross-domed churches and the sort of basilican version of a four-pillar church that we see in Jerusalem. Only a more precise dating would enable us to understand whether buildings such as San Vittore, centrally-planned though with a cupola surrounded by eight consistently tall groin-vaulted bays, had been constructed in Europe before they appeared in Jerusalem.

Thus, the combination of a Byzantine or Armenian type of four-columned church with a ‘western’ system of arches and vaults can be seen in both the Chapel of Saint Helen and the Cathedral of Saints James. One minor point at issue which sits between the plan and the elevation is the status of the capitals. These are now effectively corbels at the top of the piers with their undersides visible (Figure 8.8). In ‘classical’ Romanesque architecture a capital would be supported by a half-column or pilaster. The unusual conformation at the Armenian Cathedral has led scholars to suppose that the supporting half-columns or pilasters were cut back in the late-18th-century, when painted canvasses were placed on the faces of the piers.36 This view was endorsed by Denys Pringle: ‘The capitals that support the pointed transverse arches defining the bays, however, indicate that the piers originally had a projecting pilaster or shaft on each face.’37 It is impossible to check whether this is so today, since permission to remove any one canvas has not been forthcoming. But although the capitals obviously do project from the face of the piers, there is no sign of a corresponding projecting base. Thus, I would suggest the capitals were initially unsupported and simply corbelled out from the pier face. It is worth recalling that in the early 15th century John Poloner maintained the church ‘had four square columns’.38

Notwithstanding the above, several architectural details – the slightly pointed arches, the Corinthianesque capitals, and the south portal – do point to a Romanesque tradition. Nurith Kenaan-Kedar has cast doubt on one aspect of this – the use of a type of radial voussoir with a convex face and soffit cut as a narrow rectangular ashlar block with rounded faces, which she terms a ‘goudron frieze’. This, she believes, has antecedents in the 6th-century architecture of Greater Armenia, and to be an ultimately Armenian or north Syrian form whose use in Crusader Jerusalem was deliberately allusive.39 My 30 years of study in the field of Armenian architecture has furnished me with few, if any, analogues for the shapes used in in the cathedral’s south portal. The so-called ‘goudron frieze’ does not appear in Armenia, but it is typical of buildings in Crusader Jerusalem; most notably at the Holy Sepulchre, where it can be found on the western doorway to the Latin Patriarchate, as well as at the church of Saint Anne, both of them built in the mid-12th-century. The actual origins of the form remain uncertain. Its appearance on the Bab-al-Futuh in Cairo, completed in 1087, is probably significant, and may account for the popularity of the design in Sicily, where its first appearance was probably on the tower of the Martorana in Palermo. It is also used in the cloister at San Juan de Duero in Soria (Spain), and it is possible that the derivation is Mediterranean and the ultimate origin is Islamic Egypt. There is, however, a western French version – used in the same form as it is found in Jerusalem at Saint-Sulpice, Marignac (Charente-Maritime) of c. 1120, while tapered variations – conceived as truncated radial mouldings, can be traced back to the late-11th-century at Saint-Jouin-de-Marnes (Deux-Sèvres).40

Thus, the south portal at Saints James is typically Romanesque, like the Corinthianesque capitals and carved row of lambs on the west face of the north-east pier, lending support to Pringle’s conclusion – a conclusion with which I agree – that Frankish masons were heavily involved in the construction of the church.41

Even those specialists who think the intersecting arches and hexagonal opening are post-medieval cannot resist citing medieval analogues for the composition. Vincent and Abel mistakenly compared the cupola to work at the monastery at Haghpat (Armenia), thinking it was a building of the tenth century, whereas they, perhaps, meant the zhamatun of the church of Surb Nshan, though even here such roofing appeared only as a result of the renovation of 1209.42 Following Arzumanyan, Pringle pointed to the dome of a church in the monastery of Khorakert (Armenia), which is indeed formally close, though without further comment, before moving on to discuss the cupola in front of the mihrab in the Great Mosque of Cordoba (961), along with 12th-century Spanish and French Christian derivatives of the Andalucian domes, as in the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Torres del Rio (Navarra).43 While not neglecting the above examples, Kenaan-Kedar speculates that the form might be pre- Islamic, and traceable back to the architecture of 6th-century Great Armenia, though her argument remains unsubstantiated.44

The large group of Spanish and French Romanesque churches that deployed domes on intersecting arches has been investigated by Javier Martínez de Aguirre.45 He sees the expansion of the composition in Europe as being related to perceptions of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, as the vault-type appears in buildings either dedicated to the Holy Sepulchre or designed in emulation of it. The vault-type is among their most interesting peculiarities, and appears at Torres del Rio (Rioja), Saint-Croix at Oloron-Sainte-Marie, L’Hôpital-Saint-Blaise (both Pyrénées-Atlantiques, and San-Miguel de Almazán (Castilla y Leon) in all of which it takes the form of an eight-pointed star.46

Though the earliest appearance of this kind of vault in Spain was in the great mosque at Córdoba, a similar pattern was used over the central section of the mosque of Bab-al-Mardum in Toledo, dated by inscription to 999. After the conquest of the city the mosque was given to the Knights of the Order of St John, who transformed it into the Chapel of the Holy Cross (Ermita de la Santa Cruz) and added the apse. Thus, the building was known as the church of the Holy Cross until 1186, when King Alfonso VIII took it from the knights. Martínez de Aguirre suggests that the conversion of the mosque created a link between the Islamic vault that was the centerpiece of the original building, and the recollection of the Holy Land in the imagination of the Hospitallers.47

As such, it was the central dome in the church of the Holy Cross in Toledo that inspired a number of interpretations of the form elsewhere in Spain and south-western France, all of which appeared after the construction of the Cathedral of Saints James in Jerusalem. Because all other Armenian examples of the form are also dated to a later period, we ought to consider whether a translation of the ‘star-vault’ idea from distant Spain to Jerusalem might have been possible. Given that the dedications of the relevant Spanish churches were connected to the Holy Land, and as pilgrimage from Spain to the Holy Land was significant and intertwined with the most venerated shrine in Spain as Santiago de Compostela, it may be worth recalling the legend of the discovery of the body of Saint James the Great in Spain, while his head was left in Jerusalem and buried on Mount Sion. According to the Historia Compostelana, the body of James has been transported to Compostela by his disciples from the place where it had been thrown outside the walls of Jerusalem.48 As Spanish pilgrims and crusaders in Jerusalem had an obvious interest in the relic held in the Armenian cathedral, it is not impossible that a Spanish source could have informed the patron(s) or designer(s) of Saints James about the unusual form of the cupola of the church in Toledo.49 They could have conveyed the idea that the dome rose above intersecting arches whose points were formed a star. Then, in a nod to Armenian tradition, where the six-pointed star was a venerated symbol, the design was transformed into a hexagon (Figure 8.9). In the 12th century, these stars were used at the base of Armenian stone crosses known as khachkars, where they were carved in relief on ornamental disks as a symbol of Golgotha.50 If one accepts this, as a possibility at least, then Armenian tradition did have an impact on the dome, though only in the number of ribs.

However, looking back across the Mediterranean, it is noteworthy that no star-vaults, inherited from Moors, were constructed in Spain before the creation of the ‘dome’ at Saints James. Perhaps the construction of the Armenian Cathedral was the stimulus for these re-interpretations of the cupola at Toledo. It is also interesting that the rotunda in Torres del Rio was built on the Road of Santiago, the great pilgrimage route that connected the Holy Land with Santiago de Compostela – or, to put it another way, the road which connected the head of St James with his body. Can we be sure that the builders of Spanish and French star-vaults took them to refer to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the Holy Sepulchre only? As we have seen, the ‘quotation’ was of an originally Islamic form used in mosques. Its meaning was transformed through the conversion of a mosque into the church of the Holy Cross. Could there have been other meanings – other impulses – behind the adoption of the form? And if so, could one of these have been an association with the cult of St James as it had been promoted in Jerusalem? In that case, the Armenian Cathedral of Saints James may have been the initiator of a tradition of star-vault construction across the whole of the Christian world.

If the intersecting star vaults of Spain are eight-sided, in Armenian churches they are always made hexagonal. The source for all other Armenian examples was, obviously, the cathedral of Saints James. The first example could be the dome of the church of the second half of the 12th century in Khorakert.51 However, it was not the adoption of the form in Armenian churches that is striking. The composition flourished when it was translated into a type of building known as a zhamatun – that is a narthex that functioned as a mausoleum, or covered cemetery. This Armenian building type was seemingly first created at the monastery of Horomos (1038), and from the second half of the 12th century was actively developed. As early as Horomos, the type was associated with top lighting and was arranged as a type of tall stone tent with an upper oculus above a four-columned hall. I consider the form to be a citation of the Anastasis Rotunda in Jerusalem.52 Later, regardless of the overall shape of the ‘stone tent’, the dome came to be articulated with edges or ribs to form a six-rayed star with an upper oculus, as in the monasteries of Khoranashat and Neghuts (Figure 8.10) – an obvious reference back to the cupola of the cathedral (and martyrium) of Saints James.

The ‘dome’ is the outstanding feature in the architecture of the cathedral of Saints James. And just as its interior treatment seems to have been carefully thought out and relates it to a larger architectural tradition, so with its exterior blind arcade. The 24 arches supported on paired columns looks directly to the dome of the Cathedral at Ani, the former capital of Armenia. The detailing of the paired columns at Jerusalem, their bases and capitals, leaves no doubt that they were intended to evoke forms that had been used in Armenia since the 7th century. The bulbous capitals and unmoulded abaci are unmistakeable, though even Ani does not have quite the elegance of Jerusalem (Figure 8.5 and colour plate III). That is why it is likely that Armenian masons will have worked alongside the Latins.

It is possible – even perhaps probable – that Melisende played a role in the construction of the cathedral of Saints James in Jerusalem. Her status as a ruler of a Crusader Kingdom in combination with her Armenian descent in some ways mirrors the architecture of the cathedral. This similarly combines Armenian and Eastern Christian sources and pulls them into a broadly occidental or Latin tradition, as is beautifully illustrated by the use of groin vaults around a central ‘domed’ square. The presence of relics of St James may also have been a factor in promoting a building that acted as a bridge between the architectural traditions of East and West. The importance of the building from an Armenian perspective is that it demonstrated how well-developed regional preferences for raised drums, bulbous capitals, four-pillar plans, pastophoria with upper chapels, and open oculi could be incorporated into a church that does not look out of place in the Mediterranean. We can only guess whether the impetus for this came directly from Melisende, or whether it was a decision of the senior clergy within the Armenian Church in Jerusalem. But there must have been close supervision for this sharing of forms from different architectural traditions to work – especially so given their execution by Frankish masons, and in all likelihood, masons who had worked at the Holy Sepulchre.

The Armenian cathedral helps us understand the 12th-century architecture of the Holy Land and its position with regard to the local traditions of the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Given its potential to shed light on a process of cultural exchange, a full-scale archeological study of the Armenian cathedral is much to be desired.