The desire to link anonymous masterpieces with famous names, whether of artists or of patrons, is deep-rooted, as can be seen with the number of works of art which cluster around such names as Nicholas of Verdun and Abbot Suger. The magnificent illuminated bible at Winchester Cathedral has long been associated with one of the most celebrated art patrons of the age, Henry of Blois, bishop of Winchester from 1129 to 1171. Indeed, the bible has been associated with three of the outstanding personalities of the age. Not only has Henry of Blois been credited with its inception, but St Hugh of Lincoln and King Henry II have also been connected to it, at a later stage in its production. Current scholarly opinion tends to accept Henry of Blois’ involvement, while questioning the bible’s association with St Hugh and Henry II. In this paper I propose to re-examine the evidence for both claims.

The Winchester Bible needs little introduction.1 Originally in two volumes, it contains no marks of provenance earlier than the 17th century, but it is generally assumed to have been at Winchester since the 12th century. The text was written by a single scribe in a superb, rounded script (colour plate IV) characterised by Neil Ker as typical of the middle decades of the 12th century, up to c. 1170.2 Evidence from other giant bibles suggests that it would have taken a single scribe three or four years to copy the text.3 In places, the original scribe corrected his own work, the corrections often standing out in darker ink. Subsequently, a second scribe made further corrections and emendations to the text of the Old Testament as far as the end of Psalm 71, a little way into the second volume of the manuscript as originally conceived. He also completed the text of Malachi at the very end of volume one which the first scribe had left incomplete, and he wrote a single bifolium (ff 131 and 134) at the start of the book of Isaiah, apparently to replace a damaged or lost original (colour plate V). The hand of the second scribe has also been identified in another great bible, known as the Auct Bible or the Bodleian Bible from its shelf-mark in the Bodleian Library (MS Auct. E. inf. 1–2). Close analysis of the two by Neil Ker demonstrated that the scribe corrected the texts of these two bibles together, so he must have had them both in the scriptorium at the same time. The second scribe wrote in a more angular script which is characteristic of the last decades of the 12th century, though he seems to have attempted to match his additions in the Winchester Bible to the style of the original scribe so as to minimise the visual differences between the two. Ker dated his work probably no earlier than 1170. The fact that the two replacement leaves at the start of Isaiah were inserted as a bifolium, not as separate folios, indicates that the manuscript was still unbound at this time, and this is corroborated by the fact that the quire signatures, used to ensure that the quires were bound in the correct order, are also in the hand of the second scribe (colour plate IV). The bible must have remained unbound in the scriptorium for a number of years.4

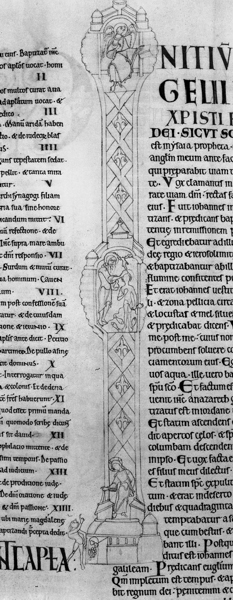

The illuminations tell a more complex story. Several artists of the highest calibre were employed, but even so, many of the illuminations were left unfinished. The seminal analysis by Walter Oakeshott published in 1945 has stood the test of time well, expanded and elaborated in later studies by Oakeshott himself and by other scholars. The precise relationships between the different artists have still not been fully elucidated, but it is generally accepted that the illuminators can be divided into an earlier and a later group. The first consists of the so-called Master of the Leaping Figures, who worked in a vigorous style using curvilinear damp-fold draperies characteristic of the middle decades of the twelfth century (colour plate IV), and another artist known as the Apocrypha Master, whose illuminations are in a distinct style which also finds parallels in the mid 12th century (colour plate VI top). Both of these artists left most of their illuminations unfinished (Figure 11.1), and many of them were completed by the four later artists to whom Oakeshott gave the names the Amalekite Master, the Morgan Master, the Master of the Genesis Initial and the Master of the Gothic Majesty. Between them, they completed all the initials in volume one (colour plates IV and VI, Figures 11.2 and 11.3), along with a handful at the start of volume two (colour plate VII). Their illuminations are characterised by figures (often set against a gold ground) which are less vigorous but more monumental in appearance, with facial types reminiscent of Byzantine or Byzantinising works of art. Their work is generally dated no earlier than 1170. The initial at the start of the book of Isaiah on the bifolium supplied by the second scribe (f. 131) is by the Master of the Gothic Majesty, indicating that he at least was working with or after the second scribe (colour plate V). Oakeshott also identified two distinct types of rubrication. The earlier type, characterised by square capitals, is distributed across both volumes and is associated with the work of the first scribe and the first two artists (Figure 11.1). The later rubrics, which are found only in volume one, are characterised by rounded, uncial forms. In places these replace the work of the earlier rubricator, and it appears that the second rubricator worked in association with the second scribe and the second group of artists in bringing volume one to completion (colour plates IV and V).

The intricacies of the relationships between the two scribes, the two rubricators and the various illuminators are not our main concern, but the question of dating is important. On stylistic grounds the work by the Master of the Leaping Figures and the Apocrypha Master was originally placed by Oakeshott between 1140 and 1160, with the later initials extending in date as late as 1225. In his later publications he placed the start of work on the Bible around 1160, and its abandonment no later than 1190.5 The narrower dating has found widespread acceptance, and the project as a whole is now generally placed within the period c. 1155–90, still a broad enough time-span to allow different interpretations of the progress of the work and the relationships between the different elements in the bible. The initial campaign, including the work of the first scribe, the first rubricator, the Master of the Leaping Figures and the Apocrypha Master, is usually dated c. 1155–70. The four later artists along with the second scribe and the second rubricator are generally dated between 1170 and 1190. But it remains to some extent an open question whether there were two distinct phases of work, with a gap of some years in between; or whether the task of creating the bible continued gradually over a number of years with interruptions as new men were brought in to carry on the project. The illumination of the bible did not necessarily run pari passu with the work of the two scribes or the two rubricators. It should also be remembered that the dates quoted above carry all the provisos that need to be attached to stylistic dating, both palaeographical and art-historical. The same applies to the other manuscripts in which the hands of the Winchester Bible scribes and illuminators have been identified, none of which is precisely dated. An analysis of the relationships between these various manuscripts is beyond the scope of the present study, but some further discussion of the relationships between the different illuminators in the Winchester Bible is given in Appendix 1.

Henry of Blois is remembered for his munificent gifts of relics, vestments, jewels and precious liturgical fittings to Winchester Cathedral and elsewhere. The Henry of Blois enamelled plaques in the British Museum give an indication of the quality of the works commissioned by him. The great Tournai marble font in the cathedral is associated with Henry, as are some high-quality sculptural fragments. He is famously said to have purchased veteres statuas while in Rome and taken them back with him to Winchester, though quite what the expression refers to is debatable. Taken as a whole, the evidence shows Henry to have been, in Jeffrey West’s words, ‘a patron who sought to add to the spiritual wealth of the communities in his care by gifts of relics and the ornaments, objects and vestments necessary to the religious life and the celebration of the holy mysteries’. In this, he conformed to the pattern expected of wealthy senior ecclesiastics, albeit with greater largesse than most. He was the kind of man who might well have been involved in the production of a magnificent illuminated bible for his cathedral.6

Two pieces of evidence have been cited for Henry’s involvement. In his 1981 monograph, Oakeshott wrote, ‘When he died, he left an endowment for the scriptorium of St Swithun’s [i.e. Winchester Cathedral]… . It would be hard to believe that Bishop Henry was not, in some way, even if that was only financial patronage, responsible for launching the project for a great bible.’ Noting that the endowment was made early in the year of Henry’s death, he added, ‘It is perhaps not fanciful to read into this his anxiety that the bible should be completed.’ The thrust of these remarks has implications both for the chronology and for the patronage of the bible. Other writers have made similar comments, but often without Oakeshott’s caution, with the result that Henry’s involvement is widely taken for granted, even sometimes stated as fact.7

Oakeshott cited Lehmann-Brockhaus, who printed a single clause from one of Henry of Blois’ charters granting the church at Ellendon in Wiltshire to the prior and brothers of Winchester Cathedral for the writing of books and the maintenance of the organs.8 A reading of the complete charter puts the matter in a rather different light. The clause in question comes from a lengthy charter dated 6 January 1171 confirming the rights and endowments of the cathedral priory. The potential for disputes between bishops and monastic cathedral chapters over the allocation of endowments is demonstrated by the case of Henry of Blois’ erstwhile protégé, Hugh du Puiset, bishop of Durham between 1153 and 1195. He was involved in a long-drawn-out and bitter dispute with the monks of Durham which involved, inter alia, the forgery by the monks of charters designed to prove their case.9 At Winchester there had been disputes between the bishops and the monks about the division of endowments earlier in the century. Henry of Blois’ charter therefore provided an authoritative summary statement of the position at the end of his episcopate which could be referred to in the future should any disagreement arise. The grant of the church at Ellendon ad libros conscribendos et organa reparanda is merely a confirmation of a previous charter by Henry of Blois dated 1142x1143. This specifies that the church had been granted to the cantor (precentor) of the cathedral and to all of his successors in office ad conscriptionem librorum et ad reparationem organorum et ad alia queque eidem monasterio necessarie supplenda. It was, in fact, concerned not just with books (which were a standard responsibility of precentors), but with the provision of all the equipment necessary for the proper running of the liturgical life of the cathedral. Furthermore, in this earlier charter Henry of Blois was explicit that he was restoring the church at Ellendon to the cathedral for the purpose ad quod antiquitus fuerat constitutum. Two earlier charters survive from Henry’s predecessor, William Giffard, dated 1107 and 1128x1129 respectively, both recording the grant of the church at Ellendon ad libros faciendos.10 In short, the phrase in the 1171 charter is merely a confirmation of a long-standing arrangement designed to provide an endowment for the office of precentor in perpetuity. It is only tangentially relevant to the Winchester Bible.

More recently, it has been suggested that evidence for Henry’s involvement can be found in the manuscript itself. The initial on f. 3, which accompanies St Jerome’s letter to Pope Damasus, shows Jerome, on the left, presenting his work to the pope (colour plate VI bottom). It is attributed to the Genesis Master, and can almost certainly be dated after Henry of Blois’ death.11 Damasus is represented as a medieval bishop, in the guise (it has been suggested) of Bishop Henry, with the book beneath his arm representing the Winchester Bible itself. The black crosses on his vestments have been thought to refer to the Hospital of St Cross which Henry of Blois had founded in 1136.12 However, the ecclesiastic on the right is not vested as a bishop. He is an archbishop wearing a pallium, a thin strip of white cloth worn on top of the other vestments which was held in place by pins terminating in small crosses. The pallium was granted by the popes to archbishops as a sign of their rank, to distinguish them from bishops. Although he had ambitions to raise the see of Winchester to an archbishopric, Henry of Blois was never more than a bishop, and never wore the pallium. Prior to the introduction of the papal tiara, popes were regularly represented in art in archiepiscopal robes with a normal mitre. The figure on the right is Pope Damasus robed as an archbishop. A similar iconography can be found in other manuscripts of the period, such as the presentation miniature in the Helmarshausen Gospels of c. 1140, which shows Pope Damasus similarly attired.13 The Winchester Bible initial is not an allusion to Henry of Blois.

The only discernible link between Henry of Blois and the bible is a coincidence of time and place. This is not to say that Henry of Blois had nothing to do with it. It is hardly credible that he would have been unaware of such a prestigious project being undertaken at the heart of his diocese during his lifetime. But the nature of any involvement requires further consideration. Having been an active protagonist during the civil war on the side of his brother, King Stephen, he went abroad at the start of Henry II’s reign. After his return in 1158 he focussed his attention on ecclesiastical and episcopal affairs.14 It could be that he commissioned the bible for his cathedral around this time. Or it may be that he commissioned it for his own use in the first instance, perhaps to be kept at the bishop’s palace next door at Wolvesey, which he redeveloped on a grand scale.15 In due course he could have given or bequeathed it (still unfinished) to the cathedral. A comparable case would be the Puiset Bible of c. 1180, which was given to Durham Cathedral by Bishop Hugh du Puiset.16 Alternatively, the project could have been initiated by the monks of St Swithun, the monastic community at the cathedral. Not long before, the wealthy Benedictine monastery at Bury Saint Edmunds had commissioned the magnificent Bury Bible. The sacrist, called Hervey, covered all the costs of the bible for his brother Talbot, the prior;17 but such an expensive undertaking could not have been carried out without the approval of the abbot, Anselm (1121–48). The mention of the sacrist is interesting. In Benedictine communities, responsibility for books within the monastery lay with the cantor (precentor). However, a few books fell within the purview of the sacrist. He was responsible for the high altar and any relics, treasures and ornaments associated with it. These would be kept securely in the sacristy when not required at the altar itself. Among them might be books which had assumed the status of relics through their antiquity or association with a particular saint, or which were categorised as treasures for the adornment of the high altar on account of their exceptional quality.18 The sacrist’s involvement suggests that the Bury Bible was envisaged as just such a book. At Winchester, the head of the monastic community was the prior, and a commission of this kind could well have originated with him, or with the cantor, or with the sacrist.19 On this hypothesis, Henry of Blois could have provided additional funding, or could have used his extensive contacts to find scribes and artists of the calibre required. But the cathedral priory could have had the resources to carry out the project on their own, in which case Henry’s role may have been no more than to advise, support and encourage. Winchester was one of the very few cities in England in the mid-12th-century which had a community of resident artists and craftsmen with all the skills required for the production of illuminated manuscripts. The 1148 survey of Winchester, which was carried out for Henry of Blois, reveals in extraordinary detail the numbers, names and locations of property-holders within the city. Leatherworkers were comparatively numerous, and one man is described as a parchment-maker. There were four property-owning painters named Henry, Richard, Roger and William, who may have worked on manuscript illumination as well as monumental painting. Even if such men were not of the calibre of the Winchester Bible artists, they would have provided a potential source of supply for pigments and other painting materials. Gold for the illuminations could have come from the goldsmiths. There were an unusual number of these resident in Winchester, no doubt as a consequence of the fact that the royal treasury was based there. Another property-holder in 1148 was Gisulf the king’s scribe, and there must have been many other scribes of one level of ability or another among the many clerks employed in the royal administration in Winchester (which was effectively the Angevin capital in England), quite apart from monastic scribes at the cathedral priory and in the other religious houses.20 The picture which emerges is one of a sizeable community of artists, craftsmen and scribes living and working within a stone’s throw of the cathedral. There must have been regular contacts between them and the monastic community. The enormous bible project must have been a regular topic of conversation not just among the monks but among interested parties in the wider community, including those who were employed by the king. Henry II himself may well have known about it.

So the bible emerged out of a context in mid-12th-century Winchester which was well-endowed materially, rich in artistic tradition, and able to draw on a wide range of contacts at the highest levels of society. If the name of Henry of Blois has tended to be attached to it in modern times, that is largely because of the reputation which he has gained as a patron of the arts. But in truth the extent of his involvement is quite uncertain. The commission could have emerged from various different sources, and its realisation over some decades must have been a collaborative affair. At this distance in time it is a hazardous business attempting to define the extent of Henry’s involvement – if indeed he was involved at all. For it is not impossible that the bible was only begun after his death. The widely accepted pre-1170 date for the first phase of work is based on palaeographical and stylistic criteria. But there are few fixed points in the history of mid-12th-century manuscripts of this calibre; and while it is not so difficult to establish a date before which certain stylistic or palaeographical features do not appear, it is very difficult to determine when they went out of fashion. A project of such ambition and quality is likely to have been entrusted to experienced hands, and one cannot exclude the possibility that the scribe of the main text, the first rubricator and the first illuminators were mature men who had learned their trade in the middle decades of the century and continued to work in the same styles into the 1170s.21 It would be as well to keep an open mind.

We come now to an incident from the 1180s which is recounted in the Magna Vita of St Hugh of Lincoln by Adam of Eynsham (Book II, Chapter XIII). It involves Henry II and the monks of Winchester Cathedral (St Swithun’s Priory) as well as St Hugh, who at the time was prior of the Carthusian monastery at Witham in Somerset. Henry of Blois’ successor as bishop of Winchester, Richard of Ilchester (1173–88), is not mentioned. The story was discussed by Oakeshott and has often been referred to by manuscript scholars, but it has never been subject to close analysis. To appreciate its nuances, it is necessary to read the whole story. The Latin text, printed in Appendix 2 to this paper, and the English translation which follows, are taken from the 1961–62 edition by Douie and Farmer. Some minor amendments to their translation are printed in italics, and an alternative translation of the passage between asterisks is given later.22

How he worked hard to obtain manuscripts of religious works, and concerning the Bible of the monks of Winchester which was given to the king and by him to Witham, which Hugh restored to its original owners, and the close friendship between these two religious communities.

‘It is right to relate briefly one of the deeds of this man who was filled with a double love for God and his neighbour, since it shows so strikingly the intense charity which burned so brightly in him. When the buildings required by the customs of the order were almost finished and the number of brethren was complete, the good shepherd concentrated upon the training of the souls committed to his care in their holy profession. He devoted much labour to the making, purchase and acquisition by every possible means of manuscripts of religious works, since these were a great assistance in this task. It was a favourite saying of his that these were useful to all monks, but especially to those leading an eremitical life, for they provided riches and delight in times of tranquillity, weapons and armour in times of temptation, food for the hungry and medicine for the sick.

Once in private converse with the king, the lack of books happened to be mentioned. When he was advised to do his best to get them copied by professional scribes, he replied that he had no parchment. The king then said, ‘How much money do you think I should give you to make up this defect?’ He answered that one silver mark would be enough for a long time. At this the king smiled. ‘What heavy demands you make on us,’ he said, and immediately ordered ten marks to be given to the monk who was his companion. He also promised that he would send him a Bible containing the entire corpus of both Testaments.* The prior returned home, but the king did not forget his promise, and tried hard to find a really magnificent Bible for him. After an energetic search he was at last informed that the monks of St Swithun had recently made a fine and beautifully written Bible which (it was said) was to be used for reading in the refectory. He was greatly delighted by this discovery, and immediately summoned their prior, and asked that the gift he desired to make should be handed over to him, promising a handsome reward. His request was speedily granted. When the prior of Witham and his monks received and examined the Bible given to them by the king they were not a little delighted with it. The correctness of the text pleased them especially, even more than the delicacy of the penmanship and the general beauty of the manuscript.*

One of the monks of Winchester happened afterwards to come to Witham for the sake of edification. The prior, with his accustomed courtesy, entertained him, and gave him the spiritual counsels he had desired. His guest unexpectedly informed him how earnestly the lord king had deigned to ask his prior for the Bible. ‘We are especially glad,’ he said, ‘that he should have given it to you, venerable father. If you are completely satisfied with it, all is well; but if not, and if it differs in any particular from your usage, we will, if you like, speedily make you a far better one, corresponding to your requirements in every detail. For we took considerable pains to make this one correspond to our own use and customs.’ The prior was amazed, for he had not known before how the king had obtained it. He immediately said these words to the monk. ‘Did the lord king indeed defraud your monastery of such an essential fruit of your labours? My dearest brother, your book shall be restored at once. I beg you most earnestly and humbly to ask your brethren to forgive us for the fact that it was because of us, although we were unaware of it, that they lost their book.’ The monk, terrified at what he had heard, implored him in horrified tones not to think or say such things. It would be fatal to his own church that Hugh should on any pretext decline a royal gift which had so fortunately won for them the king’s favour. This amused the prior, who answered: ‘Is it true that you think that you are much more in his favour than usual, and do not regret that his goodwill towards you was purchased by this magnificent gift?’ As he asserted that all his fellow monks were well content with the transaction, Hugh added, ‘To make your satisfaction lasting the restitution of your precious masterpiece shall be kept secret by all of us. If you do not agree to receive this Bible secretly, I shall restore it to the man who sent it here, but if you take it away now, I shall never tell him.’ There was no more argument. The monks received their book, as if it had been a newly acquired gift. They were delighted with the book, but still more with the courtesy and great generosity of the sender.

This action, as I have already said, demonstrated clearly the fervour of the twin loves which consumed the heart of this saintly man, since for his own advantage he would not deprive the monks of a masterpiece created for the glory of God, lest this might injure the divine honour even a little, or defraud those who had worked for it of what was profitable to them. His kindness and example were alike beneficial to his neighbours. From the reading of the book they received instruction, and were also inspired to imitate his brotherly charity, and both these things increased their devotion to their Creator. All his deeds, words and thoughts were directed to this very end, to assist his neighbour, and thus both of them should please God. Nor in his pious and righteous intention was he deceived of his hope. From this time onwards there grew up an especially warm friendship between both communities, the monks of Winchester and the hermits of Witham, which with God’s help should long endure.’

The Magna Vita was written about ten years after Hugh’s death (†1200) by Adam of Eynsham, a Benedictine monk who had been his chaplain for the last three years of his life. Adam’s Vita is generally considered one of the most reliable of saints’ lives, and to give an exceptionally vivid and accurate picture of St Hugh. In Book II Chapter XIV, immediately after the story of the bible, Adam says that he was urged to write the Vita by two senior former monks of Winchester, Robert, prior of St Swithun’s from 1187 to 1191, and Ralph, the former sacrist. Both of them had transferred to Witham and become Carthusians.23 They must have been privy to the story, both from the Winchester perspective and from the point of view of the Carthusians. Indeed, the implication is that it was one of them who negotiated with St Hugh for the bible’s return. There is therefore no reason to doubt the essential veracity of the story; but equally it may not have been the whole story. The purpose of the Vita was to honour its subject and edify the reader, and Adam does not hesitate to point out the moral of the episode, namely St Hugh’s intense love of God and neighbour. The fact that it concerns a manuscript is fortuitous, and the information provided about the bible is incidental. Much may be left unsaid. To avoid confusion, in the discussion which follows, the bible in the story will be referred to as the Witham Bible.

The story belongs to the period when Hugh was prior of Witham. He arrived there in the winter of 1179/80 and left in the summer of 1186, after his election to the see of Lincoln in May of that year. But it can be dated even more precisely. Witham had been founded by Henry II as part of his penance for the death of Becket. Book II of the Vita is constructed around three episodes in which Hugh goes to see the king and comes away with money for the fledgling community: first, to complete the purchase of the site and start building; second, to finish the buildings; and third, to acquire books – the incident with which we are concerned. Books were an essential part of the equipment of a new monastery and a legitimate call upon the resources of a founder. Now Henry II was in England on just three occasions in the relevant period, and the three episodes fit neatly with Henry’s visits. The third of these took place between 10 June 1184 and 16 April 1185, and this must be the date of Henry’s conversation with Hugh about manuscripts. On 10 April 1185, John, the prior of Winchester (†1187) and thus the de facto owner of the bible, was at Henry II’s court at Dover. According to Eyton’s painstaking analysis of the movements of the king and the members of his entourage, this was the only occasion when Prior John witnessed a royal charter, in spite of the fact that he must normally have been at Winchester when the king was in residence there. On 16 April Henry left for Normandy, and one wonders whether he might have summoned Prior John in order to wrap up the business of the bible before he left the country.24 In any case, the final conversation between St Hugh and the Winchester monks must have taken place before Hugh left for Lincoln in summer 1186. So the episode recounted in the Vita took place between the summer of 1184 and the summer of 1186.

Establishing the date of this incident is relatively easy; discerning its implications for manuscript studies is a more delicate matter. It is not certain whether the Witham Bible was the one we know as the Winchester Bible. Oakeshott initially believed so, and was followed in this by a generation of manuscript scholars. Then, in his 1981 monograph, he changed his mind and argued that the Auct Bible was the one sent to St Hugh; and this seems to have become received wisdom. Like the Winchester Bible, the two-volume Auct Bible contains the complete text of the bible in a script datable to the middle decades of the twelfth century, and its earliest illuminated initials belong to the same period. These initials are of high quality, but not historiated. Whether the Auct Bible was written at Winchester or at some other centre, such as St Albans, has been disputed, but, as already noted, it definitely seems to have been at Winchester at an early date, when the second scribe of the Winchester Bible emended the texts of the two bibles together. Around the same time, further initials were added to the Auct Bible in a style similar to that of the Morgan Master.25 So both bibles would potentially fit Adam of Eynsham’s description of a bible which had been worked on recently, and which was characterised by the elegance of its script, its careful emendations and its overall beauty. Oakeshott states – and places great emphasis on this – that ‘the story specifies (and also must, surely, imply, to make sense of it) that the book had been completed’. Since the textual corrections, the rubrications and the illuminations of the Winchester Bible were left unfinished, he argued that this ruled it out. The text of the Auct Bible, on the other hand, was corrected throughout.26 However, Adam of Eynsham was neither an art historian nor a textual scholar, and he was writing not from the point of view of a cataloguer, but as a hagiographer. His readers (apart from a few elderly monks of Winchester and Witham) would not have been familiar with the Witham Bible, nor did they need to be. Adam states that Henry II offered to send a bible which contained the entire corpus of both Old and New Testaments. The text of the Winchester Bible is complete. As Larry Ayres pointed out long ago, this is surely what mattered most.27 There is nothing in the text of the Vita that specifies that the Witham Bible was complete in Oakeshott’s sense. The verb conficere used to describe the creation of the manuscript simply means ‘make’. It is nowhere either stated or implied that the manuscript was complete in every respect. For that, perficere would have been more appropriate. The word conficere is used in two other places in Chapter XIII of Book II of the Vita, in each case simply referring to the creation of a new manuscript without any implication of total completion. First, at the start of the chapter, we are told that St Hugh devoted particular effort to making or purchasing manuscripts, or acquiring them by any other means (sacris codicibus conficiendis, comparandis, et quibus posset modis acquirendis). Second, during the conversation between St Hugh and the monks of Winchester, the latter offer to make him a replacement manuscript (conficiemus).28 The Winchester Bible cannot be ruled out on the grounds of (supposed) incompleteness.

The Vita has often been cited as evidence that the great twelfth-century illuminated bibles could have been designed for use in the refectory.29 This has always seemed improbable. A bible kept on a lectern on the floor of the refectory would have been exposed to physical damage, to spillages of food and drink, and to greasy fingers. On the other hand, if the refectory had a raised pulpitum built into the wall, as was often the case, the manuscript would have been invisible to all but the lector. Oakeshott thought (no doubt correctly) that the exceptional decoration of the Winchester Bible excluded such a mundane use for it – and this was another reason for his belief that it was the Auct Bible which was sent to Witham. But this is to miss the point of the story. Contrary to appearances, the Vita does not say that the Witham Bible was intended for use in the refectory. This is not a quibble about the absence of the word ‘refectory’: the phrase in qua … debuisset is a deliberate echo of the Rule of St Benedict, and the words ad mensam edentium fratrum unquestionably do refer to the refectory. The point is this: the text indicates that Henry II was led to believe that the Witham Bible was intended for use in the refectory. The key is in the verb, debuisset. The use of the subjunctive here means that it is reported speech, part of the message that was conveyed to the king. If its intended use in the refectory had been a simple statement of fact, the verb would be in the indicative. In English, this nuance can be conveyed by adding ‘it was said’ or some such phrase, as I have done in the translation above. In support of this reading, it may be noted that the main verb, suggeritur, is curiously oblique: not ‘the king was told’, but ‘it was intimated (or suggested) to the king’ that the bible was intended for use in the refectory. The difference is subtle, but substantial.

The 12th century was a time of intense discussion about the varieties of religious orders, about the differences between canons and monks, between Benedictines and Cistercians, about the roles of the military orders and of hermits. The Carthusians, with their special blend of the eremitical and coenobitic, had only just established themselves in England with the foundation of Witham, and their unique characteristics may not have been widely understood. The protagonists in the story, however, and many of Adam’s readers would have been well versed in the differences between Benedictines and Carthusians and their implications. Against this background the story takes on a new significance. Henry II had set his mind on the Witham Bible. The Winchester monks were desperate to keep it, but did not dare oppose the king directly. Instead, they tried a diversionary tactic. They put it about that the bible was intended for use in the refectory. Why? Because Benedictines ate in the refectory every day and listened to readings while they ate; whereas the Carthusians had their meals separately, in their individual cells, in silence. Only on Sundays and major feast-days did they eat together in the refectory. On these occasions they did have readings, but the readings were integrated into a broader sequence of readings which extended across the daily offices in such a way as to ensure that the monks read the entire bible every year. Only a small minority were read in the refectory. This sequence was unique to the Carthusians, and they developed a distinct type of bible to match, marked up to show the cycle of readings. An early English Carthusian bible of the second quarter of the 13th century is annotated in this manner, with a few of the readings being marked in refectorio, because they were the exceptions. This bible must have come either from Witham or from nearby Hinton (founded in 1227), the only other Carthusian house in England at the time.30 So the rationale of the response of the Winchester monks to Henry II was that the Witham Bible would have been an inappropriate gift for St Hugh. It was (they claimed) intended for use in the refectory; but the Carthusians seldom ate in their refectory, and on the few occasions when they did, they did not use a standard bible, but one which had been specially prepared for their own cycle of readings. The subterfuge failed to deflect the king. Perhaps he was oblivious to the differences between Benedictine and Carthusian practice; or perhaps he saw through the story and carried on regardless. Hugh, on the other hand, could use the subterfuge to his own ends. He must have known that the circumstances of the gift were questionable, that this was no mere off-the-shelf bible, but a magnificent manuscript that must have been years in the making. And in any case, it did not answer his need for books for everyday use. Both the Winchester and Auct Bibles are so massive and unwieldy that it is hard to see what practical use the Carthusians could have made of either.

The sub-text to the discussion with the Winchester monk (which should be read as Adam of Eynsham’s literary dramatisation of some very delicate negotiations) is that both parties understood the situation implicitly and were tip-toeing their way around an unspoken but potentially explosive truth.31 Great stress is laid on the question of whether the Witham Bible corresponded to Carthusian usage or not. If not, the Winchester community promised to make another one which did – presumably one that was customised for the Carthusians along the lines of the 13th-century manuscript from Witham or Hinton. That explains why the replacement bible would be ‘better’, i.e. much more useful to the Carthusians. The Latin is longe meliorem, ‘far better’, and not, as Oakeshott and the published translation would have it, ‘far finer’, or, as some have glossed it, ‘even bigger’, wrongly implying that Hugh would be impressed by an even grander or more beautiful manuscript. The dynamic of the story does not require that the Winchester monks should actually have supplied a replacement bible: nor is it said that they did. The discussion of monastic custom and usage was merely a way to find a form of words which would enable the Winchester monks to recover their manuscript without either being humiliated or offending the king. All the same, both parties realised that it would be prudent not to reveal that the Witham Bible had been returned to Winchester. So the whole business about the bible being intended for use in the refectory was merely a stratagem. While it failed to divert the king from his intention, it did provide Hugh with a means to solve a high-stakes version of a familiar problem: how to dispose of a valuable but unwanted gift without offending the giver.

So we should not be fooled into thinking that the Witham Bible was a refectory bible. On the contrary, the likely role of the sacrist in the bible’s return points in a different direction: that it was the kind of book which would have adorned the high altar and would have been kept in the sacristy along with the church treasures.32 After it was sent back to Winchester it must have been kept hidden at least until Henry II’s death in 1189 and probably for some years thereafter. It would have been impossible to carry on working on it without word getting out. This is the key to identifying the Witham Bible. As is well known, the textual emendations and the illuminations of the Winchester Bible were never completed. The second scribe stopped emending the text at the end of Psalm 71. It is striking that the latest phase of illumination by the Byzantinising artists ceases at much the same place. The last work by the Genesis Master is to be found in the double Beatus initial of Psalm 1 on f. 218, where he painted over drawings by the Master of the Leaping Figures. The Morgan Master appears for the last time in the double initial to Psalm 101 on f. 246 (colour plate VII top), where his painting over the drawings by the Master of the Leaping Figures was left unfinished. Similarly, the final work by the Master of the Gothic Majesty was also left unfinished, namely the double initial to Psalm 109 (f. 250) (colour plate VII bottom) and the immediately following initial to Proverbs (f. 260), the latter once again over a drawing by the Master of the Leaping Figures.33 The unfinished initials by the Morgan Master and the Master of the Gothic Majesty thus appear within a few folios of each other, shortly after the point where the second scribe abandoned his textual corrections. All of this suggests that the work on the Winchester Bible was interrupted suddenly, never to be resumed. The story of the Witham Bible provides a perfect explanation both for the interruption to the work on the Winchester Bible, and the failure to resume it subsequently. Had it been the Auct Bible which Henry II sent to St Hugh, the illumination of the Winchester Bible could have carried on to the end.34 The opposite applies to the Auct Bible. Ker noted that there was a change in the process of emending the text of the Auct Bible at the end of Psalm 68 verse 8. Up to that point the emendations were first noted down in the margin, then the original text was corrected, and then the marginalia were erased. However, from this point onwards, the emendations in the margin were no longer erased. As Ker commented, ‘It is remarkable that the corrections written in the margins of the “Auct” Bible have been erased only up to a point near to that at which corrections in the Winchester Bible cease.’ It would seem that the correction of the Auct Bible was interrupted at the same point. However, unlike the Winchester Bible, the corrections in the Auct Bibile were completed, as were the illuminations.35 It is hard to see how the work could have been completed had the Auct Bible been the Witham Bible. Oakeshott’s original intuition was correct. It was the Winchester Bible which was sent to Witham.

The abandonment of work on the Winchester Bible can therefore be dated between June 1184 and the summer of 1186, perhaps around the time of Henry II’s departure from England in April 1185. This falls within the period usually assigned on palaeographical and stylistic grounds to the latest contributions to the bible, and it gives us an unusually precise date for the individuals who were employed on it when the project came to a halt. These are, first, the second scribe, who was responsible for the bifolium at the start of the book of Isaiah (colour plate V) and the second set of textual emendations up to the middle of the book of Psalms. He also worked on the Auct Bible. Second, the second rubricator, who was responsible for the decorated lettering in the uncial style, which appears only in volume one (colour plates IV and V). And third, two at least of the illuminators, namely the Master of the Gothic Majesty and the Morgan Master, who both left initials unfinished. The Genesis Master left no initials unfinished. His work appears mostly in volume one, but he also completed the pair of Beatus initials at the start of the Psalms in volume two (f. 218) which had been begun by the Master of the Leaping Figures. It may just have been a coincidence that he left no unfinished initials. Alternatively, it may be that he stopped working a short while earlier. There would have been no difficulty having three or four individuals working on the Psalms at the same time, assuming that the manuscript was still unbound. Henry II’s intervention would explain why the different contributors all apparently stopped work at about the same time. The book would then have had to be bound before being sent to Witham.

But why was the Winchester Bible chosen? Douie and Farmer translated the second paragraph of the story to mean that Henry II initially had no particular copy of the bible in mind, and only learnt about the Winchester Bible during the course of the search. Oakeshott translated the passage in a similar sense,36 and this has been accepted in the subsequent literature. However, the Latin can be translated in a different way:

‘The prior returned home. The king did not forget his promise. He made earnest enquiries about a very fine bible to give him. Eventually, as he kept asking insistently, it was indicated to him that the monks of St Swithun had made the outstanding bible recently with handsome workmanship to be read from while the brothers were eating at table. When he learned this, the king was very pleased. He summoned the prior of that church to come as quickly as possible, and asked for the gift which he desired to be given to him, promising generous compensation. His request was speedily granted. And so the prior and brothers of Witham received the book as a gift from the king. When they examined it, they too were greatly pleased with it, particularly appreciating the elegance of the script, as well as the overall beauty of the work, and its painstaking corrections.’

In many ways it would make much better sense if Henry had already set his mind on the Winchester Bible from the outset. As we have seen, he may well have known about it for some years. There would have been plenty of ordinary manuscripts of the bible in Winchester at the time, around the cathedral priory, at Hyde Abbey and the other religious houses, perhaps even in stock at the book-sellers. Any one of these would probably have been more useful for the Carthusians on a daily basis, and could have been acquired much more easily and cheaply. Even the Auct Bible, which is by any standards a magnificent manuscript, would have caused less resentment within the cathedral community.37

Whichever reading we prefer, why would Henry have insisted on such an extravagant and problematic gift? A clue is provided earlier on in Book II of the Vita. As well as business meetings to do with Witham, Hugh used to meet Henry individually for private conversations. He had an unusual rapport with the king, and Adam of Eynsham devotes part of Book II of the Vita to this theme.38 He was the only person who could assuage Henry’s anger when he was in a dark mood, sometimes even teasing him in public. On one celebrated occasion, arriving late for a meeting and finding the king in a fury, he disarmed him by reminding him of his descent from the bastard William the Conqueror. In private meetings he gave Henry personal advice and spiritual counsel, sometimes citing the examples of illustrious men of former times. Never was Henry more in need of it than following the rebellion and death of his son and heir, Henry the Young King, in 1183. The discussion about the manuscripts took place during Henry’s first visit to England since the death of the Young King. It was probably just one of a number of conversations, of which no record does (or could) survive, in which Hugh sought to calm the king’s anger and soften his grief. Or, as Adam of Eynsham puts it, ‘At this time the king had often to face misfortunes of every kind, which he bore with more resignation owing to the consolations of this holy man.’ We perhaps have here a motive for Henry’s determined generosity in the matter of the bible, whose gift went far beyond the normal obligations of a monastic founder.

Against this background, the iconography of the Morgan Leaf merits further scrutiny.39 Inserted into the previously-written opening at the start of the First Book of Kings (alias I Samuel), it contains a sequence of images from the stories of Samuel and David (colour plates IX and X). The Old Testament contains numerous tales of the doings of the ancient kings of Israel and Judah, which provided precedents or parallels for the behaviour of medieval monarchs, and could be used to point a moral. The Books of Kings were a favourite place for historiated initials on the theme of kingship. There was also a tradition of narrative cycles from the life of David. However, this is the only narrative cycle of the story of Samuel and David in English 12th-century bibles; and the only other bible with an extant full-page illumination at this point, the Bury Bible, is completely different.40 The individual scenes on the Morgan Leaf can be paralleled in continental manuscripts, but the selection of scenes is unique to the Winchester Bible; and it is this choice which may provide a clue to their significance. The essential narrative of the Morgan Leaf is not difficult to follow. The recto illustrates the story of Samuel. Starting at the bottom left with Hannah’s prayers for a son, it continues down the right-hand column with scenes of Samuel’s childhood in the Temple and his calling by God, concluding with his anointing of Saul to be the first king of Israel. The verso depicts scenes from the life of David. In the first register David confronts and kills Goliath and puts the Philistines to flight, watched by Saul and the army of the Israelites. David’s triumph provoked Saul’s jealousy, and in the second register Saul is shown trying to kill David with a spear while he plays the harp. This is followed by the anointing of David by Samuel in the presence of Jesse and his brothers. The bottom row starts with the death of Absalom, and the narrative concludes with David’s grief on hearing the news, when he uttered his famous lamentation ‘O my son Absalom, O Absalom my son’. The appositeness of this choice of scenes to Henry II is striking. He too succeeded to the throne as a young man after a period of conflict with the incumbent monarch, King Stephen, who, like Saul, had been properly anointed king but had fallen from favour. On the verso, Samuel’s anointing of David is shown after the duel with Goliath and the final appearance of Saul, whereas in the Old Testament his anointing comes first. This may merely be a narrative device to simplify the story of David’s succession; but it may also have been done in order to strengthen the parallel with Henry II, who was only anointed and crowned king after Stephen’s death. Thus far the narrative is taken from the First Book of Kings. Of the many episodes from David’s kingship recorded in the Second Book of Kings, the only one represented on the Morgan Leaf is the armed revolt of Absalom leading to his death and David’s outpouring of grief.

So familiar is the Morgan Leaf that it is easy to overlook the fact that the image of David’s grief at the death of Absalom which concludes the cycle is the first surviving representation of this scene in English art. Indeed, only a handful of earlier examples are recorded from western Europe. The story cannot fail to evoke the revolt and death of Henry II’s own son, Henry the Young King. Having been anointed and crowned king in the presence of his father at Westminster in 1170, Henry the Young King became increasingly frustrated. As a crowned monarch, he could reasonably have expected to exercise royal functions, yet Henry II refused to relinquish any of his powers to his son. In 1173–74, the Young King, supported by his brothers, took up arms against his father. His campaign was not crowned with success, and he was forced to make accommodation with his father. However, ten years later, the Young King was in armed revolt against Henry II once more, this time dying on campaign in June 1183 before he had reached the age of thirty. Henry II was grief-stricken.41

The Young King’s revolts were the most painful open sore to afflict Henry II in his later years, and caused profound disquiet across the Angevin Empire. Contemporaries were not slow to compare Henry the Young King to Absalom, and Henry II himself is said to have cited precedents in the Old Testament for kings who exacted terrible revenge on their enemies. Yet in the event, for all his grief, Henry II treated the Young King and his supporters with surprising leniency, and favourable comparisons were made with King David, who had shown no such clemency to Absalom’s counsellors.42 Against this background, it is hard not to read the Morgan Leaf in the light of contemporary events.

What passed between St Hugh and Henry II during their private conversations must forever remain a matter of speculation, but it is not fanciful to suppose that the biblical precedent of David and Absalom was discussed. Both Hugh and Henry used works of art to reflect on contemporary issues. Some years later, while at Fontevrault with the soon-to-be-crowned King John, Hugh gave him a sermon on the fate that awaited evil kings while standing in front of a sculpted tympanum of the Last Judgement at the entrance to the church. Hugh pointed out some crowned kings among the damned, and urged John to avoid a similar fate. In response, John pointed to some kings standing among the saved and said that he intended to be numbered among them. Adam of Eynsham concludes with a comment of St Hugh’s about the purpose of Last Judgement sculptures: they were placed at the entrance to the church so that those who were about to enter should recognise the final fate which awaited them, pray for forgiveness, and thereby escape the torments of the damned and win everlasting joy. It is a rare contemporary statement of the didactic functions of portal sculptures, and gives an insight into the way in which Hugh envisaged works of art being employed to convey a spiritual message.43 Henry II ordered an image of an eagle being mobbed by four of its young to be painted on the wall of one of the chambers of his palace at Winchester, as a permanent reminder of the rebellion of the Young King and his brothers.44 The impact of the Morgan Leaf, when freshly painted by the Morgan Master in the early 1180s must have been immediate. Had Henry II seen it, he could hardly have ignored its relevance to his own situation. Had he associated it with the words of spiritual consolation that he had received from St Hugh, this might explain why he was so determined to send him the Winchester Bible – the only manuscript in England, to our knowledge, to have contained an illuminated cycle which would have spoken so directly to his own predicament.

Whether or not a scenario of this kind explains the story of the Witham Bible, this reading of the Morgan Leaf has wider ramifications. The Morgan Leaf was created in two stages. The drawing on both recto and verso was the work of the Apocrypha Master, who also began to paint the scenes on both sides, but the painting was completed by the Morgan Master. The story of David and Absalom was just as relevant to Henry II after the first revolt of the Young King in 1173–74 as it was ten years later. The imagery makes little sense in any contemporary context prior to 1173, when the Young King was still the apple of Henry’s eye. This suggests a possible date for the Apocrypha Master’s work on the Winchester Bible in the mid 1170s. It also offers a plausible approach to the interpretation of the other two full-page drawings by the Apocrypha Master in volume two of the bible (Figures 11.4 and 11.5). The books of Judith and Maccabees are not the most obvious candidates for full-page illuminations, as Oakeshott recognised. He explained them on the grounds that the full-page illuminations were not part of the original scheme for the bible, but were only conceived when the first scribe was well on through the second volume.45 Whether or not this is correct, it still does not explain why Judith (f. 331v) and Maccabees (f. 350v) were singled out for special treatment, rather than any of the New Testament which follows on immediately after Maccabees. Judith is one of the least well-known books of the bible, and it is mostly illuminated with no more than an initial, generally showing Judith killing Holofernes. Interest seems to have focussed on Judith as a type for the church. Narrative cycles are unusual, and no other 12th-century bible has such an extensive one. As with the Morgan Leaf, iconographical parallels can be found for the individual scenes in the Judith and the Maccabees pages, but the full cycles are unusual in the context of 12th-century bible illuminations.46 Both concern the defence of Jerusalem in the face of infidel aggressors and focus on the roles of heroic individuals. Judith’s assassination of Nebuchadnezzar’s general, Holofernes, enabled the Israelites to defeat the invaders in battle before they reached Jerusalem, whereas the Maccabees page depicts the divine revenge on King Antiochus for setting up idols in the Temple at Jerusalem through the intervention of Judas Maccabeus, who laid down his life for the cause. Both stories find resonances in the Crusading spirit of the times. As part of his penance for the death of Becket, Henry II agreed in 1172 to pay for one hundred knights under the command of the Templars to assist in the defence of the Holy Land. Henry’s own participation in the Crusades was also under discussion in these years and he continued to allocate annual sums for the purpose (while cannily refusing to let them be spent). He himself was supposed to set off on Crusade to the Holy Land within a year, though he repeatedly found reasons to postpone his departure.47 As a set, the Morgan Leaf and the full-page illuminations to Judith and Maccabees with their bloody scenes of conflict and battle contrast markedly with the complex theological miniatures in the Bury Bible and the Lambeth Bible. A key to their significance, it may be suggested, is to be found in the political and military events of the mid-1170s.

This topic would merit further investigation. Meanwhile, it brings us back to the question of the origin of the Winchester Bible and the identity and role of its patron or patrons. As we have already seen, there are no firm grounds for connecting the original commission with Henry of Blois, and the dating of the first phase of work is debatable. If the narratives of the Morgan Leaf and the Judith and Maccabees pages were composed with a view to contemporary events, it means that the work of the Apocrypha Master should be dated to the mid-1170s. This is slightly later than the date usually assigned to him, but only by a few years. The date of the start of work would then depend on our assessment of the relationship between the Apocrypha Master and the Master of the Leaping Figures, and between the two of them and the first scribe. This is explored further in Appendix 1. It is usually assumed that the Winchester Bible was a purely ecclesiastical initiative. The possibility of Henry II’s involvement in its making seems never to have been explored, but it deserves consideration. As noted above, the bible project cannot have been unknown to members of the royal administration in Winchester. Did Henry II not merely know about it, but contribute to it, financially or in some other way, perhaps through his international contacts? Winchester was not just his English capital; it had a particular personal significance for him. It was at Winchester in November 1153 that the settlement was agreed which brought an end to the civil war and paved the way for Henry to ascend to the throne on the death of King Stephen a year later. The agreement was negotiated with the help of the two leading churchmen of the day, Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury and Henry of Blois, and it was Theobald who, Samuel-like, anointed and crowned King Henry a year later.48 In 1172, Henry the Young King was crowned a second time in Winchester Cathedral, and his young wife Margaret was anointed, consecrated and crowned queen of England. Had Henry II at any point felt inclined to make a thank-offering to the cathedral, the bible would have been an obvious focus for royal patronage. If he were involved, it would help explain his insistence on the Winchester Bible being sent to Witham and would make his intervention perhaps a little less high-handed, a little less like robbery. There are many avenues still to be explored.49

To conclude: the Winchester Bible continues to fascinate and tantalise with its combination of outstanding scribes and artists, its enigmatic origins and high-level connections, and the still elusive process of its creation. Much that has been taken for granted needs to be re- assessed.50 The Winchester Bible was the bible sent by Henry II to St Hugh at Witham. It was not a refectory bible, but more probably a sacrist’s book designed to adorn the high altar. The date of its inception remains unclear. The involvement of Henry of Blois, so widely assumed, has still to be demonstrated, while the iconography of the full-page illuminations by the Apocrypha Master would be consistent with a date after his death in the mid-1170s. The abandonment of the project in 1185 (or a few months before or after) provides a precious fixed date in the history of 12th-century manuscripts. It has significant implications for our understanding of the careers of the illuminators (several of whom have been identified in other manuscripts). And it has wider ramifications. The late-12th-century wall-paintings in the Holy Sepulchre Chapel in Winchester Cathedral are close in style to the Morgan Master’s illuminations, though opinion is divided as to whether the wall-paintings are actually to be attributed to him. A date of c. 1185 would seem appropriate.51 Even more important are the celebrated wall-paintings from the chapter house at Sigena, which are remarkably close in style to the work of the Morgan Master in the Winchester Bible.52 Oakeshott indeed concluded that the paintings at Sigena were probably created by the Morgan Master working with some of the other artists who had been employed at Winchester, including the Gothic Majesty Master. The royal nunnery of Sigena was founded in 1188 on the site of an earlier hospital. Placing the conclusion of work on the Winchester Bible in 1185, rather than the 1170s as some have suggested, brings the work of the Morgan Master and the Gothic Majesty Master very close in date to the Sigena paintings. Susanne Wittekind is currently exploring the circumstances of Sigena’s foundation and the impact of its connections with the kingdom of Aragon on its buildings and decoration. In the present volume, Neil Stratford has demonstrated how the mission of the Patriarch of Jerusalem to England in 1185 (seeking assistance for the beleaguered kingdom of Jerusalem) occasioned direct personal links between the court of Henry II and Sigena. Although it is not known for certain whether the patriarchal mission visited Winchester or not, the links between them is symbolised by the appearance of Prior John of Winchester at the royal court at Dover on 16 April 1185 as the members of the mission waited to set sail with the king. The timing was exactly right. With the Winchester Bible project coming to a sudden close, the artists would have been on the look-out for new employment. It would seem that Henry II’s intervention in the matter of the manuscript not merely resulted in the cessation of work on the Winchester Bible, it also had the effect of making available a team of outstanding artists to work on the wall-paintings at Sigena.

When at court, Hugh avoided getting sucked into administrative business (Vita, Bk II, Ch. VII), so his appearances there cannot be traced in charter witness lists or other such documents.

The relationships between the different artists in the Winchester Bible are complex and difficult to grasp. Tabulating the distribution of their work across the bible makes it easier to discern certain patterns. The accompanying Table is based on the work of Walter Oakeshott, who had a longer and closer acquaintance with the bible than any other scholar, supplemented by the listings by Kauffmann and Donovan.53 It lists the illuminated initials in the order in which they appear in the bible, including some which have been cut out from volume one, and spaces where initials were planned but never executed. Oakeshott was able to attribute the underdrawings of almost all the painted historiated initials, but he was not always able to identify the designers of the painted decorative initials. The surviving full-page illuminations are also listed, including the Morgan Leaf; but full-page illuminations whose existence has been inferred but not proven are excluded. The contributions of the different artists are shown as follows:

The sections allocated to the various artists are indicated by boxes, bold for the first phase of work, double line for the second. The original division into two volumes is indicated, the foliation is continuous throughout.

The first two artists to work on the bible were the Master of the Leaping Figures and the Apocrypha Master. Both of them left unfinished initials which were completed by four later artists. The relative chronology of the earlier and later artists is therefore not in dispute. The Master of the Leaping Figures worked across almost the entire manuscript and contributed to more of the initials than anyone else. In most cases, however, he never progressed beyond the stage of the underdrawings, some of which are themselves unfinished (Figure 11.1). A few of them were gilded but not painted. He only painted six of the surviving initials (colour plate IV), one of them being the double initial to Psalm 51. He was responsible for most of the unfinished decoration of volume two, namely the drawings for a series of initials at the start of the volume, from Psalm 1 (f. 218) to II Chronicles (f. 303), and another major sequence from II Maccabees (f. 363) through almost to the end of the New Testament (Philemon on f. 459). His contribution to volume one is, in its present state, less significant and more sporadic, consisting only of eight or nine initials between Exodus (f. 21v) and Micah (f. 205). However, he has probably suffered disproportionately from the mutilation of this volume.

The Apocrypha Master appears for the first time with the Morgan Leaf and the initial to I Kings (f. 88). He then has four initials in a row from Daniel (f. 193) to Joel (f. 200v) (colour plate VI top). Another set of initials runs from Zephaniah to Zechariah, all on folios 209 and 210. Lastly, he appears in volume two between f. 331v (the full-page Judith miniature) and f. 350v (the full-page Maccabees miniature). The Apocrypha Master painted only three of his own initials (ff 198, 200v and 342), but all of his other drawings for initials were painted over by the later artists. Of the four full-page illuminations which he designed, he started to paint only the Morgan Leaf. This was completed by the Morgan Master,54 but the Judith and Maccabees pages remain unpainted and demonstrate the quality of the Apocrypha Master’s drawing.

The Master of the Leaping Figures and the Apocrypha Master left very similar patterns of work in the bible. Both left most of their drawings unpainted, and neither artist painted any of the other’s drawings.55 Both worked on discrete sets of initials which do not overlap. In volume one each group consists of between four and six initials in a row, whereas in volume two the great majority are the work of the Master of the Leaping Figures, with just one, important contribution by the Apocrypha Master in the Old Testament Apocrypha. Some of the initials which were left blank in this first phase of work also fall into groups, on ff 1–5 and ff 169–90. These various groupings bear no obvious relationship to the text of the bible, but they do relate to the physical structure of the manuscript. The bifolios are assembled for the most part in standard quires of eight, and there are a few single leaves. The divisions between the groups reflect the quire structure. The first three blank initials are all on the first quire. Thereafter, for most of volume one, the successive groups cover a number of quires, reflecting the length of the texts. Then, towards the end of the volume, where the texts are shorter, the two artists alternate on successive quires. The initials for Daniel to Joel by the Apocrypha Master on ff 193–200v all belong to a single quire. The Master of the Leaping Figures drew the initials on the next (rather mutilated) quire (ff 201–08); and the Apocrypha Master reappears with a sequence of initials on the following quire, which completes volume one. In volume two, the Master of the Leaping Figures drew the initials from Psalms to II Chronicles. Then, after a gap of sixty folios, he drew the very last initial in the Old Testament Apocrypha, II Maccabees, on f. 363, followed by all of the New Testament initials.

On the assumption that the lost initials in volume one followed the same pattern, their designs can be attributed with reasonable confidence to one or the other of the two early artists, as suggested in the Table. The Isaiah initial by the Master of the Gothic Majesty (f. 131) (colour plate V), which appears on the replacement bifolium written by the second scribe, presumably replaced an original initial designed by the Master of the Leaping Figures.

Within the discrete groups worked on by the two early artists, there are a few initials which they never started. The ones in volume one were filled in by the later artists, whereas all but one in volume two remain blank to this day. At first sight these initials seem to be scattered randomly across the manuscript, but on closer inspection a rationale does emerge. Most of them are what might be described as secondary initials – that is to say, they are either purely decorative, non-historiated initials; or they relate to subordinate divisions within the text; or both. The initial I to Ruth (f. 85v) is purely decorative (and when eventually designed by the Morgan Master was extended downwards well below the accompanying text in order to make it more impressive). The initial on f. 204, which was left blank by the Master of the Leaping Figures and subsequently created by the Genesis Master, is likewise decorative rather than historiated. It also marks the preface to Jonah, rather than the start of the actual biblical text, and it is noticeable that the initials to the other prefaces to the minor prophets towards the end of volume one are all decorative (f. 197v, f. 209v, f. 210 and f. 210v).56 These were all designed (but not painted) by the Apocrypha Master. One other initial which was left out by the Master of the Leaping Figures is the double initial to Psalm 109 (f. 250). This is the theologically important Trinitarian initial referring to the opening words of Psalm 109 (Dixit dominus …), which was designed (but left unpainted) by the Master of the Gothic Majesty (colour plate VII bottom). The system of marking these four psalms with elaborate initials has a number of precedents and parallels. However, in terms of the divisions of the text of the book of Psalms, the initial to Psalm 109 can be considered a secondary one compared to those which commence the three sets of fifty psalms (Psalms 1, 51 and 101). A similar case is the prayer of Habbakuk of f. 208, at the end of a quire worked on by the Master of the Leaping Figures. This is a secondary initial marking a section of text within the book of Habbakuk, as also are the decorative initial to Daniel chapter 5 on f. 193 by the Apocrypha Master, and the initial to the prayer of Jeremiah marking the start of chapter five of the Lamentations (f. 169) (Figure 11.2). It is also noticeable that the final, largely unilluminated initials to the end of the Old Testament and the Apocrypha between ff 316 and 351 include blank initials to the prefaces to Job, Tobias and Judith, and to the books of Tobias and I Maccabees, both of which are marked ad placitum (‘as you please’). These initials all seem to have been considered of lesser importance even though this is the section of the manuscript which includes the two famous full-page drawings by the Apocrypha Master on ff 331v and 350v.

Thus, taking into account what we can deduce about the missing initials and the secondary initials, we can say that the Master of the Leaping Figures and the Apocrypha Master both began all the major historiated initials within the sections which they worked on, with only a few exceptions. In volume one these are the initials to Leviticus and Numbers on ff 34v and 44, and perhaps Micah on f. 205, all in sections worked on by the Master of the Leaping Figures. The Malachi initial on f. 213v is at the very end of volume one, where the text was for some reason left unfinished by the first scribe. He stopped writing halfway through a word at the bottom of column one, and this probably explains why the Apocrypha Master left the initial blank. The second scribe added in the missing section of text as far as f. 214, and the initial was created by the Genesis Master in this second phase. In volume two there are a number of blank initials between Job (f. 316v) and I Maccabees (f. 351), with only the Ezra initial (f. 342) drawn and painted by the Apocrypha Master. His two unfinished full-page drawings to Judith and Maccabees are also in this section, and it may be that this was where the Apocrypha Master abandoned work on the bible. Otherwise, in volume two, the Master of the Leaping Figures drew all of the major initials except those to I Chronicles, Acts, Hebrews and the Apocalypse.

So, between them the Apocrypha Master and the Master of the Leaping Figures designed most of the initials in the bible. In volume one up to the Joel initial on f. 200v, the initials were divided between them in alternating groups of similar size, whereas the last two groups of initials at the end of the volume, which correspond to single quires, have more. The blank initials between ff 167 and 172 also form a group which for some reason does not seem to have been allocated to either artist. At any rate, it does not interrupt the pattern of alternation between the two. In volume two, the alternation continues, but in a different rhythm. The Master of the Leaping Figures designed a long set of initials between Psalm 1 and II Chronicles, followed by another sequence from II Maccabees onwards. The Apocalypse Master did just one initial (Ezra) and drew the designs for the two full-page illuminations to Judith and Maccabees. However, if all of the blank initials between Job and I Maccabees had been allocated to him; and if we count the full-page illuminations as the equivalent of perhaps six initials, then the division of labour between the two artists was much more balanced, and over the manuscript as a whole works out at about half each.

Within their allocated sections, both artists worked in similar fashion. Both prioritised the main initials over the secondary ones, and left some initials blank; both prioritised the design drawings over the painting; both painted just a handful of their initials, distributed through the manuscript in no obvious pattern. All of this suggests that the unbound quires of each volume were allocated to the two artists so as to give them approximately equal shares; that they both addressed their task in similar fashion; and that this modus operandi provided much greater flexibility than would have been possible with a linear progression through the illuminations of each volume.

A corollary of this is that the process of illumination would not have started in earnest until the text of volume one was complete, or nearly so – perhaps indeed not till the first scribe had finished the whole bible. This implies a gap of at least a year or two between the start of work on the text and the illuminations, perhaps longer. This helps make sense of some other features in the manuscript. Much of the puzzlement that has been felt by some commentators on the bible stems from certain assumptions about the process of its creation – assumptions which are questionable. If it is assumed that the illuminations ‘ought’ to have been created in order from Genesis through to the end, the pattern of work of the two artists is inexplicable. If it is believed that the entire cycle of illuminations was conceived in detail at the outset, and that the first artist(s) worked in close collaboration with the first scribe, then certain features are hard to explain. The initials, for instance, do not always correspond in outline to the spaces left for them by the scribe. Some overlap the text slightly, some fail to fill the spaces (Figure 11.1 and colour plate IV). But similar discrepancies can be found in other illuminated manuscripts of the period, even of the most lavish kind, and are not surprising when illuminators were working on pages of text written in advance. Inconsistencies in the bible in the display lettering which accompanies the initials can also be paralleled elsewhere. Such features need not be considered serious anomalies, or evidence of significant deviations from a pre-existing plan. Rather, they are indicative of a normal, on-going process of production involving scribes, illuminators and rubricators, whose work was not always precisely co-ordinated.57