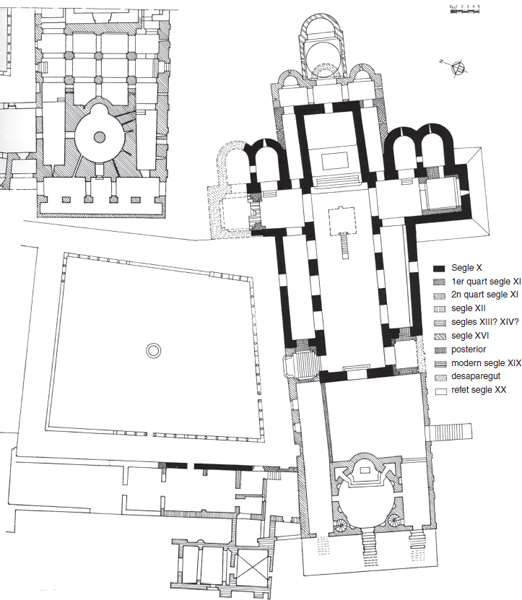

Figure 13.1

Sant Miquel de Cuixà: Plan of the abbey (R. Mallol)

Sant Miquel de Cuixà was one of the outstanding Catalan monasteries, particularly between the 10th and the 12th centuries. Founded in the 9th century and closely associated with the counts of Cerdanya, it enjoyed successive moments of splendour before starting to fade in the late 12th century.2 As a result of the French Revolution, the monastery was secularised, after which its archives and many of its treasures were dispersed, some of them finding their way onto the international art market.

Fortunately, the monastic church survived. This was constructed in the second half of the 10th century and was consecrated during the abbacy of Guarinus in 975.3 Although the church was built by conservative local labour, it is large and incorporates an innovative east end with multiple altars, which historiography has related to that of Cluny II. The well-known charter mentioning the consecration of this building is an interesting text, the work of Miro (Bishop of Girona 971–84 and Count of Besalú 965–84), who was also the author of the charter of the consecration of Santa Maria de Ripoll in 977. Written in a grandiose if refined style, it set a standard for later texts of a similar nature.4 Material testimony of the consecration is the high altar stone, a large piece of reused Roman marble, which today stands on modern supports.5

For Cuixà, the second half of the 10th century was a period of intense contact with Italy that involved journeys to and from Rome, Venice and Monte Cassino on the part of the circle formed by Abbot Guarinus, Count Oliba Cabreta and the aforementioned Count-Bishop Miro.6 Illustrious guests from Venice also visited the monastery, particularly the fugitive Doge Pietro Orseolo (†988), who ended his days as a hermit at Cuixà, where he was buried and would come to be venerated as a saint.7

From 1008, the Abbot of Cuixà was Oliba, a member of the family of counts of Cerdanya-Besalú, who simultaneously and until his death (1046) was abbot of the monastery of Ripoll. In 1018, he also became Bishop of Vic. Oliba was one of the most notable figures of the first half of the 11th century.8 It was during his mandate that the monastery at Ripoll became a rich and active cultural centre. Throughout a long career, Oliba promoted a number of major architectural projects, essentially at the places he governed, either as bishop (Vic Cathedral) or as abbot (abbeys of Ripoll and Cuixà).9 All were major undertakings, evidently indebted to the prestigious models that Oliba had seen on his travels to Rome.10 In addition, the documentary sources tell us that he was also responsible for a number of discrete artistic projects involving liturgical furnishings (the altar canopies in Ripoll and Cuixà)11 and perhaps a series of paintings in the monastic church of Ripoll.12 It should also be noted that it was during Oliba’s abbacy that the most important illustrated bibles to have survived from Ripoll were produced.13

Oliba was the addressee of the valuable and well-known text written by the monk Garsies of Cuixà between 1043 and 1046 which, among other things, describes the architectural patronage of Guarinus and Oliba in considerable detail.14 It is an anniversary sermon and, despite the nature of the text (a kind of ekphrasis that imitates the pompous style of the 975 act of consecration), it has been proved to be highly reliable.15 The measurements given for the altar stone, for example, are as they are in reality. In his text Garsies also mentions the monastery’s origins, and reports on its extraordinarily large collection of relics.

Oliba’s activity in Cuixà was respectful of what already existed. It has been said, and it is interesting to note this now, that Oliba deliberately conserved the previous building because of its association with Guarinus.16 Whatever view we take of that claim, Oliba surrounded the main apse with an aisle that opened onto three apse chapels to the east, he monumentalised the ends of the transepts with two enormous towers and he constructed a building on two levels a few metres to the west of the west façade. This consisted of a centralised sanctuary dedicated to the Trinity above a circular crypt dedicated to the Mother of God, the latter another work by Oliba influenced from Rome.17 The crypt was probably inspired by that at Santa Maria Maggiore, and which also invoked Christ’s birthplace. It is no coincidence that the Cuixà crypt was known from the outset as the crib (praesepium; pessebre in Catalan; Figures 13.1 and 13.13).18

In the main church, Oliba erected a canopy above the altar that had been retained from the church of Guarinus. We can be sure of this thanks to Garsies’ text, and I will specifically refer to it later. Although Garsies made no reference to any other liturgical furnishings, it is hard to believe that there were no altar frontals of precious metal, as we know existed in other abbeys of a similar status. The inventories that provide us with so much information about Ripoll have not been conserved in the case of Cuixà, and the documentary references are scarce and imprecise.19

Oliba died in 1046 and was buried at Cuixà (sepultus est in Cocxano monasterio Sancti Michaelis),20 which by that date had become a wealthy monastery associated with a series of uomini illustri: the Abbots Guarinus and Oliba; the Counts of Cerdanya, who founded the monastery and included Oliba Cabreta, who is said to have ended his days as a monk at Monte Cassino; and the aforesaid Venetian Doge and saint, Pietro Orseolo.

A century later, Abbot Gregorius (c. 1120–46) promoted a new artistic era at Cuixà. The works which were undertaken, in all likelihood, during his abbacy can be understood in a context that was almost as splendid and ambitious as that of Oliba’s period in office. The historiographical reputation of the great 11th-century abbot–bishop have rather overshadowed Gregorius, and reduced him to a background figure.

Fate has been unkind to Gregorius, depriving us of information about his person: we do not know when or where he was born, or anything about his family. And his name, unusual in Catalan onomastics of the era, makes this even more intriguing. We have a rich collection of charters that can be associated with Oliba, while for Gregorius – at least for now – we have to be content with scant and fleeting references in documents for which he is never the subject. Sometimes Gregorius doesn’t even make it into general historical or artistic studies of 12th-century Catalonia, while the name Oliba is omnipresent, meaning his figure has become almost mythologised.21 Of the latter we conserve news and proof of his magnificent task of artistic promotion (ranging from important buildings to extraordinary illustrated manuscripts), while works possibly commissioned by Gregorius remain undocumented. To add to the difficulty, what little information there is on Gregorius is neither clear nor uncontested, as the documentary sources are only known in later copies.

Thus it is not easy to reconstruct a life of Gregorius or assess the role he played. But let us review what we do know about him, and what works can be attributed to his abbacy at Cuixà. What we can say, with all due caution, is that the start of his abbacy may be placed around 1120, and that he apparently died on 25 March 1146.22 At some time after he became Abbot of Cuixà he was appointed Archbishop of Tarragona. Certain historians assert that this happened in 1137, basically because this was the year when the previous Archbishop of Tarragona, Bishop Oleguer of Barcelona and future saint, died. However, Gregorius did not receive the pallium until 1144, as we know from a bull of Pope Lucius II granted at the Lateran Palace only days after acceding to the pontificate.23 At this date, the Archbishopric of Tarragona was in a far from stable state. The consolidation of the conquest of Tarragona from the Muslims had been difficult, as was the restoration of the metropolitan see. It is thought that neither the first archbishop of the restored see, Sunifred, Bishop of Vic, nor the second, Oleguer, Bishop of Barcelona – both of whom retained their respective episcopal offices – even took up residence in Tarragona. The same may have happened to Gregorius, and it may not have been until the accession of his successor, Bernat Tort (1146–63), that things changed. Tarragona’s archiepiscopologia have almost nothing to say about Gregorius.24 At the time, then, the office of Archbishop of Tarragona must have been honorific rather than effective, and Gregorius probably maintained his close links with Cuixà.25 The Cronicon Rivipullense II recorded his death, referring to him as archiepiscopus Terragon(ensis) et abbas Cuxanensis. We do not know where he was buried, and although this cannot yet be demonstrated, it is reasonable to assume that it was at the abbey of Cuixà and not at Tarragona.26 His abbacy must therefore have lasted for twenty years, long enough to be able to engage in what was to become a notable artistic activity at the monastery. This is known indirectly from a chronology of the abbots of Cuixà written in the 14th century, where it is specified that Gregorius ‘fecit claustra marmorea et postea fuit archiepiscopus Tarraconensis’ (‘made the cloister in marble and afterwards became archbishop of Tarragona’), a reference that is usually put forward to attribute the construction of the cloister to his abbacy.27

Approximately half the cloister is still in Cuixà (Figure 13.2), while the rest is mainly in the United States (New York, The Cloisters).28 It is a praiseworthy project, not just because of its size but also its pioneering nature. It is considered the first sculpted cloister in Catalonia, and probably marks the beginning of what historically are known as the Roussillon workshops. The distinctive designs employed at Cuixà spread to other parts of Languedoc and Catalonia, becoming progressively diluted. The cloister at Cuixà is built of a characteristic pink marble from the nearby quarries at Vilafranca de Conflent, giving it its attractive colouring.

It is all the more remarkable when we note that it may have been during Gregorius’ abbacy that a magnificent marble tribune decorated with carved reliefs may also have been built. Though this was dismantled at the end of the 16th century, and only fragments survive, we can get an idea of its overall appearance by examining the tribune at the neighbouring Augustinian priory of Santa Maria de Serrabona, although that at Cuixà was probably bigger. As Eduardo Carrero has argued, the Serrabona tribune is still in its original position, and has always stood half-way along the nave, not at the western end as has usually been supposed. The Cuixà tribune will have occupied a similar location, near the presbytery.29 Both structures give a notable role to sculpture, and share a common ornamental and iconographic repertoire, which eschews narrative imagery as was generally the case in buildings associated with the Roussillon workshops. Both are also made from the same pink marble as was used in the cloister at Cuixà. In terms of its material, ornamental profusion and type, there is no question that the tribune of Cuixà was as original as it was spectacular, as on a lesser scale is that of Serrabona (Figure 13.3). What survives, as with the cloister, is now divided between Cuixà and the United States.30 Some of its elements ended up being used to frame two doors: the main door into the monastery and that of the abbot’s house (Figure 13.4) as can be seen in 19th-century engravings.31 During the 1950s restoration, these were transferred to the door between the church and the cloister, their current location (Figure 13.5).

Although we have practically no documentation on Gregorius, we do have a portrait. This is a marble relief representing an ecclesiastic with a mitre and crozier and wearing a pallium (Figure 13.6). He is holding a book on which we can read ABBAS and in the arch that frames him is the inscription GREGORIVS [A]RCHIEPIS[COPUS] (the second word in mirror writing). In a clear example of the dispersal of Cuixà’s property, the plaque was found in 1986 at the Salon des Antiquaires in Toulouse, and was returned to the abbey. Its provenance was subsequently confirmed, as it was described when still at the monastery.32 It has been speculated that the relief may have been originally sited in the cloister, since documents attribute its construction to Gregorius, and there are examples where the abbot responsible for a cloister is commemorated within the cloister. However, Ponsich suggested that it will have come from the tribune, a suggestion that has recently been confirmed by Anna Thirion, who proposed that Gregorius will have been set on its western façade, facing the nave and accompanied by symbols of the evangelists, all looking towards the Agnus Dei framed within a medallion.33 This appealing location would allow Gregorius to ‘sign’ his work and perpetually offer it to Christ.

Although most authorities have dated the tribune to the 1140s, it has recently been argued that it was created in the 1150s or 1160s, after the abbacy of Gregorius, rendering his portrait commemorative.34 However, no account has been taken of the manuscripts produced at Cuixà during the abbacy of Gregorius, abbotship, though these may offer important insights into the dating of the tribunes.

Proof that the Cuixà scriptorium was active during the abbacy of Gregorius is a Commentary on the Psalms (Perpignan, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 3) whose colophon (f 176) tells us that it was commissioned by him: Abbas Gregorius, prudens, discretus, honestus, me scribi iussit (Figure 13.7).35 The deliberately eye-catching style of this colophon (colourful, with large letters and a more intricate layout) uses a script that is comparable to that of the tribune inscriptions referring to the evangelists Matthew and Luke and on the representation of Gregorius. The colophon and the carvings even share some palaeographic details, such as the uncial h set amongst capital letters. This is not the only case where epigraphic inscriptions and highlighted texts from a manuscript have been related. Another well-known example is Moissac, where the similarity in both form and content of the commemorative inscription on the western face of the central pillar in the western gallery to the colophon of a manuscript has been pointed out.36

At Cuixà there are other significant links between sculpture and manuscript illumination. It is interesting to note that several ornamental motifs used in both tribunes are also found in manuscripts which must have been illuminated at the monastery. One is a late-12th-century liturgical Gospel Book (Perpignan, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 2), whose link to Saint Michael of Cuixà is confirmed by its calendar of saints’ days, (fols. 185–204v), which includes the feasts of Saints Flamidien and Nazarius, both of them represented by relics kept at the monastery.37 But the manuscript which is most notable in respect of the ornamental repertoire it shares with the tribunes is an illustrated Gospel Book (Perpignan, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 1).38 This must belong to the time of Gregorius, as it seems to be contemporary to the aforementioned Commentary on the Psalms, undoubtedly commissioned by this abbot.

The Gospel book opens with a Maiestas Domini (fol. 2) (Figure 13.8), which, like many of the manuscript’s illustrations, is uncoloured. Conversely, it is the only illumination that includes abundant foliate decoration. Close similarities can be recognised between this ornamental repertoire and what can be seen in both tribunes (both Serrabona and Cuixà). Thus the motif that resembles a cornucopia from which stems burst forth, on the spandrels of the image of the manuscript, is clearly present in several variations at both tribunes (Figures 13.8 and 13.9). The same occurs with the border formed by a series of quatrefoils, and, which we find again, transformed into a floral motif by the addition of a central button, with the same sequential repetition on the tribune at Serrabona and on the remains of the one at Cuixà. Finally, a palmette set within a semicircle between the feet Christ in the Christ in Majesty reappears under the hooves of some quadrupeds on the tribune at Serrabona (Figures 13.8 and 13.10).39

There is more to say about the relationship between this manuscript and the abbey. It includes, among its first folios, a series of images that, as I argued some time ago, cannot be understood as anything other than representations of the abbey’s main places of worship, associated with the figures of the Abbots Guarinus and Oliba.40 Moreover, apart from the illustrations which could be considered conventional for Gospel Books (like the Maiestas, canon tables and some Gospel episodes) there are three (fols 2v, 3 and 14v) that are as original as they are exclusive to this manuscript. They are full page and are to be found at the beginning of the book, which is indicative of their importance. The first (fol. 2v) is an early example of a Gnadenstuhl Trinity, or Throne of Grace (Figure 13.11). This must be related to the Church dedicated to the Trinity erected by Oliba to the west of the monastic church and praised by Garsies, of which vestiges remain. Underneath this is the crypt dedicated to the Mother of God, as invoked in another miniature in the manuscript (fol. 14v; Figures 13.12 and 13.13). In this case, the unidentified subjects surrounding the Virgin and Child could be martyrs buried in a circle around her feet, as was described by Garsies.41 It is tempting to relate them to specific individuals, above all the two depicted without a halo: one a bishop or arch-bishop and the other wearing a crown. Any suggestion is necessarily speculative, but it is tempting to suggest these might have been intended to represent Gregorius and Ramon Berenguer IV.

The third of the images (fol. 3; Figure 13.14) shows a concentric circle, with the Agnus Dei at the centre, surrounded by the busts of sixteen haloed figures. Four other busts are set on the cardinals of the outermost circle, with the symbols of the evangelists, enclosed in medallions, at the corners. This folio must refer to the high altar of the monastic church, and most probably alludes to its now missing canopy. According to Garsies, it was Oliba who erected this canopy, just as Moses had built the mercy seat (propitiatorium). It featured sculpted images of the symbols of the four evangelists on the exterior (at the angles one supposes) and an image of the Agnus Dei in an elevated position, where it could be contemplated by the evangelists and apostles of the interior.

Garsies devotes a long description to the canopy.42 This may have something to do with an aspect of his life which has been neglected in the scholarly literature: his participation in the design of the ciborium, which Garsies himself explains in the first part of the sermon, where he states that he was responsible for the paintings and the figures of the evangelists (Propitiatorii quoque coloribus et evangelistarum figuris si asignavi). In his ekphrasis, he constantly alternates description with symbolic interpretation. This and the complex style of the text – ‘confused and over-elaborate’ in the words of Junyent – make it almost impossible to precisely visualise the structure. First, Garsies refers to the supports, four red marble columns topped by white capitals with diverse foliage and flowers. Then he expands on the symbolic reading of the colour red as the blood of the martyrs, and the purity of white, and has recourse to the stereotype of likening the bases to the doctors of the church:

Bases, inquam, iuxta unius hominis incessum quatuora calce procul altaris posuit, totidemque columnas e marmore rubicundi coloris e singularibus saxis in pedibus septem voluntaria fortitudine erexit […] et in columnis martyrum gloriam praemonstrans, qui corporis pasioni rubicundi, spiritus puritate candidi […] … doctorumque caterva qui constantia fortitudinis vel zelo rectitudinis in basibus sustentant plebemiunctam summo capiti in unitate fidei. Super capita etiam columnarum, ut candorem eclesiasticae castitatis imprimeret, ac spiritualium gratiarum flores proficientibus meritis, vanos timores tolleret, ex albo marmore capitella statuit, foliato corpore et flores diversarum modum.

He goes on to describe the roof:

Desuper autem, ut ordo habebat, de lignis sectis in utraque parte propitiatorii contra se invicem positam columnas habentes tres semi cubitos ambientes arcus infra iuncturas vel secto et serrato ligno virtutes sanctorum innexuit, quae mutuo sibi quasi ad fenestras versa vice alter in altero proficuos fructus in arboream sustollerent firmitatem. Inter iuncturas autem arcus in arcemque ascensus fenestras in omni genere specierum sive operum multitudine diligentissima pictura variatas substraxit.

It seems clear that this was a structure of some complexity, made of wood, with columns and arches, suggesting, perhaps, a two-stage roof with an intermediate tier of little columns. This caused Puig i Cadafalch to offer a reconstruction based on Roman ciboria of the Romanesque era, like those of San Clemente in Rome, San Nicola in Bari or at the basilica at Castel Sant’Elia.43

Finally, Garsies refers to the carved and painted motifs, possibly his own work as we have seen, on the ceiling:

Inter iuncturas autem arcus in arcemque ascensus fenestras in omni genere specierum sive operum multitudine diligentissima pictura variatas substraxit. Sculpsit quoque in giro per quadrum, ita ut facie a faciem se viderent, dolatili ligno imagines quatuor evangelistarum, subiitque eos infra status formae superioris et reclinationem arcus inferioris, sic ut aspectus eorum in quatuor mundi partes evangelii grata concordaret, altiori vero gradu Agnum eorum aspicerent. Interiori namque ambitu, non ad pompam et claritudinem vulgi opulentissimus praesul, sedin laudem duocdcim apostolorum bonique illorum magistri virtutem pretiosi ligni ordines XIII adfixit, ut apostoli inter semitas iustorum abintus filium hominis in spiritu gloriae suae illustrarent, ac sancta animalia exterius, Agnum Dei per cuncta tempora in una dominatione stantem proferrant, et intus vel fortis aeterni regis tribunal et solium mysterii revelationibus familiariter adornarent, atque pia munera offerentes in Christo unum corpus efficerent. Omnem enim materiam intrinsecus et extrinsecus in proceram celsitudinem fecit surgere, et manibus artificium faciem angulosque sic exornavit ut nusquam iunctura paginis apparet.

If we accept that the folio from the Cuixà Gospels recreates the canopy over the main altar, it would appear to have had a domed or polygonal interior, embellished with an Agnus Dei surrounded by different figures, probably apostles and martyrs. A similar arrangement is found in the canopy at San Pietro al Monte in Civate (from around 1100) where the Lamb is worshipped by martyrs, on the basis of Chapter 7 of the Apocalypse, with the four winds on the pendentives and – as at Cuixà – the symbols of the evangelists carved on the exterior (Figures 13.15 and 13.16).44

Apart from Civate, we know of another canopy which had paintings inside its ceiling. This stood above the main altar in the cathedral of Compostela, and was erected by Archbishop Gelmírez, after his return from a trip to Rome. It has not been preserved but, as at Cuixà, we have a fairly detailed description, in this case in the Codex Calixtinus. As Serafin Morelejo pointed out, both descriptions reveal that the canopies had many features in common: namely the Lamb, the Evangelists, the virtutes sanctorum and the apostles, which in Compostela were sitting in a circle (sedent per circuitum).45 Furthermore, the canopy of Gelmírez was painted on the interior (deintus vero est depictus, deforis autem sculptus et depictus), as is the case at Civate and as I think also happened at Cuixà.

We do not know when the Cuixà canopy disappeared: it may have been during the course of the reforms carried out at the end of the 16th century, when the church of the Trinity was demolished and the tribune dismantled.46 Attempts have been made to associate with it four fine Corinthian capitals preserved at The Cloisters Museum in New York and originating from Cuixà.47 They are made of white marble (not pink) and their size does not match the dimensions of either the cloister or the tribune. This, coupled with the fact that the decoration matches the description of Garsies (ex albo marmore capitella statuit, foliato corpore et flores diversarum modum), makes them ideal candidates to be from the canopy. However, several authors hold that the capitals at the Cloisters are much later, of around 1150, placing them a century after from the canopy.48 On the other hand, a base of pink marble still preserved at Cuixà may have formed part of the piece.49

As we have already seen, Garsies specifies that the canopy was supported on red marble columns crowned with white capitals decorated with leaves and flowers. The colours symbolised, respectively, the blood of the martyrs and spiritual purity. Various ancient Christian authors (such as Prudentius) had previously associated particular colours with martyrs, and with material elements of the sanctuaries that protected their bodies.50 It is significant that when canopies are represented in the Ripoll bibles, the columns are reddish (Rodes Bible, vol. II, fols. 129v and 130v – colour plate XV, top), as are those of the canopy over the altar under which the souls of the martyrs are housed (Rev. 6, 9) in the painting in the apse at Sant Quirze de Pedret (Solsona, Museu Diocesà i Comarcal – colour plate XV, bottom).51

At Cuixà, access to pink marble from the nearby quarries in Vilafranca de Conflent, which ranged in colour from pale pink to red, was a happy circumstance that afforded the monastery access to stone with a chromatic range pregnant with symbolic potential. There is an intriguing possibility that these marble colours were deliberately exploited on Oliba’s ciborium, not only to represent the martyrs’ blood as alluded to by Garsies when he described their columns, but also to emulate the canopies with porphyry columns that Oliba would have seen on his travels to Rome, as Immaculada Lorès has proposed.52 This brings us back to Gregorius, and the period when Vilafranca marble was used in the cloister and the tribune, and points to other possible works commissioned by this abbot.

A fountain currently on display in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and another now in a private property at Èze en Provence (Alpes-Maritimes), are both made of the same pink marble, and are believed to correspond to Gregorius’ abbacy.53 The presence of two fountains in a plan of the monastery drawn up in 1779 (one in the cloister and the other in a small cloister or garden between the abbot’s house and the infirmary) could account for the existence of two. The Philadelphia fountain (Figure 13.17) consists of a circular font supported on six strong colonettes with foliated capitals. The font is embellished with a blind arcade, ‘seemingly mirroring the arcade of the cloister in the midst of which the fountain stood’, as Walter Cahn pointed out.54 Today it stands in a modern catch basin in imitation of the one represented in a 19th-century engraving of Cuixà.55

The two ‘fountains’ thought to have come from Cuixà conform to a type of cloister laver that was widespread in the Romanesque era.56 What we know about 12th-century cloister lavers, extant or otherwise, indicates that they were important elements of the cloister garth, and had a value over and above their practical function. In keeping with this, they received particularly careful treatment and were usually made of quality materials. The Moissac font, which has not survived, is mentioned in the chronicle of Abbot Aymeric of Peyrac (1377–1406): ‘lapidem fontis magni claustri predicti fecit aspotari’. It specifies that it was made of marble (lapis fontis marmoreus) and was attributed to Abbot Ansquitil (1086–1115), the builder of the cloister.57 At Conques a magnificent cloister laver made of dark green serpentine survives, a special and valued stone obtained from the quarry at Firmy, some 20 kms from the monastery. Serpentine had also been used to carve elements of the funerary monument of Abbot Bégon (1087–1107), including the plaques that record his epitaph, and describe him as the promoter of the cloister – Hoc peragens claustrum, quod versus tendit ad austrum.58 Finally, of particular interest is another font, also made of serpentine from the same source as the Conques example, and today located in the Place Saint-Géraud in Aurillac (Cantal), in front of the Romanesque hospital. It comes from the former monastery of Saint-Géraud, an important Cluniac house, and is one of the two lavers that we know were there: one in the cloister and the other in front of the abbot’s domus.59 The Breve chronicon Auriliacensis abbatiae, written around 1120, specifies: ‘Petrus de Roca […] claustra quae prius ligna fuerant, lapidea extruxit, marmorea altaria aedificavit. Cum diversa montanorum loca peragrasset, invenit lapidem marmoreum longe ab Auriliaco, de quo geminas conchas fabricavit, unam in claustro, alteram ante domum Abbatialem’.60 The existence of two fonts at Aurillac parallels Cuixà and supports the proposition that at the Catalan abbey too, one of lavers stood in front of the abbot’s residence.61 Both the Moissac and the Conques lavers, as well as those at Aurillac, were commissioned by the very abbots who had built the respective monastic cloisters and are made of quality materials. All also seem to date from the first quarter of the 12th century. By virtue of typology, material and circumstance the laver in the cloister at Cuixà fits perfectly into these contexts.

In addition to the Cuixà laver, the Philadelphia Museum conserves a seat in which the pink marble is at the red end of its chromatic range (Figure 13.18). Although it is not certain that it came from Cuixà, and it has even been claimed that the cross on the back of the throne is a forgery, the seat would seem to be 12th century.62 Could this also be related to Gregorius? He had outdone his already illustrious predecessors in the abbacy by obtaining the rank of archbishop, as proclaimed by the awkward inscription on the relief with his portrait. Achieving the role of archiepiscopus made him an ideal candidate to order a seat (a cathedra), which he could not use at the purely official see at Tarragona, but was possible at his abbey. Moreover, the intense colour is reminiscent of porphyry. For some time, the Church had appropriated the symbolic prestige of this material (and its substitutes). Especially in Italy (and even more so in Rome), where it was still being used in the guise of spolia columns furnishings and liturgical objects, the latter including ecclesiastical seats. It was precisely in the 1130s that the sedes porphyreticae were installed in the Lateran. These were twin Roman seats that would be used for papal coronations and which, despite their name, were not made of porphyry, but of rosso antico.63

Since the beginning of the 12th century and as a result of the Gregorian reform, Rome had been conducting an intense renewal of its churches, which frequently involved the embellishment of the presbytery with a new pavement and new liturgical furnishings. A prime example, which became a model in Rome and its region, is San Clemente, which at the time of Cardinal Anastasius (c. 1100–c. 1125) had been equipped with a new pavement and a canopy, plus a schola cantorum and a marble chair, both reusing previous material of special significance.64

In Cuixà it seems likely that Gregorius undertook an extensive refurnishing of the church which involved a choral tribune, a chair and quite possibly a mosaic pavement. Xavier Barral has already suggested that a few fragments of mosaic discovered in the 1960s may have come from the monastic presbytery and date to the time when the tribune was constructed.65 The presbytery of the church of the monastery of Ripoll also housed a mosaic, probably dating from the 12th century, of which some remnants and a drawing have been preserved.66 The fragments from Cuixà and Ripoll show several technical and material similarities that allow them to be considered as contemporaneous.

Our lack of knowledge about the life and movements of Gregorius make it hazardous to speculate about his exposure to art and architecture elsewhere, but he must have visited Rome at least once, as he received the pallium from Pope Lucius II in 1144. This is late in his abbacy (Gregorius died two years later) but it does not preclude an earlier journey to Rome. At the start of the 12th century, Archbishop Gelmírez of Compostela launched an important programme of renovation of the presbytery of the Cathedral of Saint James that included, among other features, the canopy referred to previously.67

Still conserved today in the cloister at Cuixà, flanking the door that leads to the church, are two pink marble pillars on one of whose faces are represented, respectively, the Apostles Peter and Paul. There are undoubtedly related by material and production with the sculptures of the tribune, which is where they originate (Figure 13.5).68 Like the statues of Peter and Paul on the door at Ripoll or the former west portal at Sant Pere de Rodes, they invoke and vindicate the link with Rome.

Memory is important in all monasteries and the record of the consecration of 975 and the anniversary sermon of Garsies took the form of chronicles which were highly commemorative in nature. And although bibliographic activity at Cuixà has been overshadowed by that of Ripoll, it was clearly outstanding. It should be noted that Catalan historical writing can be first discerned at Cuixà in the late 10th century, to be transferred from there to Ripoll in Oliba’s times. Also, in the final third of the 11th century, a Vita of Pietro Orseolo was composed on the basis of earlier texts that must also have been written at the abbey.69 Moreover, as can be deduced from numerous indications, the history of the founder of the dynasty of the Counts of Barcelona, Wilfred the Hairy, was written at Cuixà before being included in the first version of the Gesta Comitum Barcinonensium.70 It has been argued that Abbot Gregorius was the author, or inspirer, of this literary-historical work extolling the legendary dynastic origins of the then powerful House of Barcelona. It was presumably thanks to these links that Count Ramon Berenguer IV appointed him Archbishop of Tarragona.71

The mid-12th-century saw the compilation of the Cartulari major which, as happened with many cartularies, included several false documents, among them the opening two charters, which claimed that the founder and first abbot of Cuixà, Protasius, had accompanied Charlemagne to Rome for the imperial coronation.72 In any event, the author of the falsification had a reasonable knowledge of history and was in good company in giving the monastery a legendary Carolingian origin, a practice then endemic throughout France and the Catalan counties.73 Thus, from the late-10th-century until the 12th century, the writing of history had a prominent place at Cuixà.

Just as Guarinus may have preserved the memory of the original monastic oratory of Saint Michael in his ambitious apse, Oliba respected its shape with his intervention. The altar consecrated in 975 was sheltered by a canopy in Oliba’s day, around 1040. To its west, a century later, Gregorius built the choral tribune and perhaps also added a seat of honour. In the tribune, the image of Gregorius would have stood beside that of the angel of Matthew, a possible visual metaphor which has been related to the terms in which Garsies’ sermon described his predecessor Guarinus: ‘angelus vel cœlestis homo’, while the tribune itself establishes a dialogue with Oliba’s canopy.74

Thus, the works that Gregorius commissioned equated him with his illustrious predecessors (Abbot Guarinus and Bishop-Abbot Oliba) while, in turn, he rendered tribute to their works. Moreover, Gregorius undertook a renovation that was materially and ideologically inspired by Rome. No text comparable to that of Garsies has been conserved from Gregorius’ period, unfortunately. But the aforementioned Gospel Book, which was probably illustrated under his auspices, to a certain extent does serve this function. What Garsies evokes with words, the Cuixà Gospels records in images.

The artistic chapter which the virtually unknown Gregorius seems to have inspired at Cuixà, with its still poorly defined parameters, looks as rich as it is interesting. And its inspiring referents – Cuixà’s monastic past and the present of the Rome of Gregorian reform – make it even more attractive. Gregorius died in 1146, exactly one hundred years after Oliba. This centenary, which we assume was beyond the abbot and archbishop’s ability to control, constitutes an incomparable climax to his abbacy.