During the reign of Alfonso II, king of Aragon and count of Barcelona (reigned 1162–96), the palace chancery in Barcelona produced a massive two-volume cartulary that has come to be known as the Liber Feudorum Maior (Barcelona, Archivo de la Corona de Aragón, Real Cancillería, Registros, núm. 1). Alfonso commissioned this book to consolidate the documentary evidence of his authority in the kingdom of Aragon, the counties of Catalonia, and the recently acquired county of Provence. It was the end product of an immense archival project spearheaded by the dean of Barcelona Cathedral, Ramon de Caldes, who oversaw the collection, organisation and transcription of over 900 documents.1 The resulting manuscript was virtually unprecedented: the Liber Feudorum Maior (hereafter LFM) is one of the earliest extant lay cartularies (most others having been produced by monastic and cathedral scriptoria to document ecclesiastical privileges and territorial holdings), and one of very few examples of its genre to be enhanced with illuminations.2 The novelty of the LFM as a cartulary both secular and illuminated prompted its creators to develop innovative iconographic strategies for the illustration of its various charters, which document an array of socioeconomic arrangements, including treaties, agreements (convenientiae), oaths, judgements, donations, sales, wills and betrothals. Most of the cartulary’s illustrative programme is dedicated to scenes of homage or vassalage, represented through the repeated depiction of figures kneeling and offering their clasped hands to a seated lord (Figure 25.1).3 It also includes scenes of treaties, the bestowal of castles, a marriage, the exchange of gold coins for land and an enigmatic circular composition featuring an enthroned couple surrounded by a radially arranged group of gesticulating courtiers (Figure 25.2).4

The LFM’s best-known image, however, is its extraordinary frontispiece, which ostensibly re-enacts the patronage of the book itself (Figure 25.3 and cover). Beneath a characteristically Iberian polylobed arch, King Alfonso and Ramon de Caldes sit to either side of a pile of charters, selecting source material for their cartulary.5 To the right, an amanuensis in secular garb works on a new sheet of parchment that will presumably be incorporated into the new codex. To the left, six courtiers attend the proceedings, though their collective gaze is fixed not directly on the action within the chancery, but slightly upward: they appear to be admiring the elaborate, turreted architectural frame that describes the urban environment in which Alfonso’s palace is embedded. Thematically, the frontispiece can be compared to the medieval tradition of presentation scenes: illuminations that depicted codices – the very codices of which they were themselves a part – being presented to a secular patron or recipient, or to a saintly dedicatee.6 Like presentation scenes in general, the LFM frontispiece self-reflexively constructs a mythologised origin story for itself, but with a very different set of implications regarding the role of the patron, who is shown not as the book’s recipient but as an active agent in its production. This is a significant iconographic shift, for the illuminator might easily have opted to (or been instructed to) represent the archivist Ramon de Caldes deferentially presenting the work he had overseen to the king, who had commissioned it. Instead, the painting depicts the cartulary not as a gift intended to glorify a ruler, nor as a luxurious commodity purchased by a client, but as both an in-house project and a work in progress – one with which the patron was closely involved.

The frontispiece might thus be interpreted as the pictorial ‘signature’ of Alfonso as the cartulary’s patron. However, unsolved mysteries surrounding the manuscript’s chronology complicate such a reading. Much early scholarship on the LFM presumed that it had been completed before King Alfonso’s death in 1196 at the age of thirty-nine – an assumption stemming largely from its prologue, which appears on the verso of the frontispiece.7 This eloquent prologue, written by Ramon de Caldes himself, addresses King Alfonso as the cartulary’s patron and recipient, implying that it was completed before his death. If the painting on the folio’s recto eschews the formula of a presentation scene, the prologue on the verso has been interpreted as a kind of textual translation thereof. To be sure, there is no doubt that the work of transcription took place during Alfonso’s reign; according to the palaeographic study of Anscari Mundó, the primary scribal campaign was complete by 1192, with various additions made in later years.8 But several art historical studies have suggested that its illustrative programme should be dated decades after his death. These assessments cite as evidence the stylistic characteristics shared by the LFM and the Las Huelgas Beatus (also known as the Later Morgan Beatus – Figure 25.4).9 This manuscript, made for the royal foundation of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas, a community of Cistercian nuns just outside Burgos (Castile), includes a colophon stating that it was completed in September 1220. A rare and valuable clue for art historians attempting to date illumination through formal analysis, the ‘magic number’ 1220 has in turn been applied to objects perceived to be related to the Las Huelgas Beatus, including the LFM. The illuminations of the Barcelona cartulary have likewise been dated to the early 13th century by several scholars in recent decades.10 If, following these style-based analyses, the LFM was illustrated as late as the 1220s, its pictures would significantly postdate King Alfonso’s death. This has profound implications for our understanding of his cartulary’s patronal history, as well as our interpretation of its frontispiece. Should this miniature be understood as a tribute to a dead king rather than the ‘signature’ of a living patron? If so, whom should we credit as being responsible for the cartulary’s illumination?

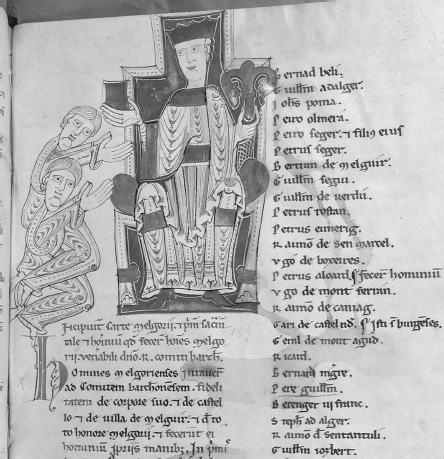

Patronal analysis of the LFM is further complicated by the fact that it was illustrated in two radically different styles. One, which I call ‘style A’, is rooted in the Romanesque pictorial traditions of 12th-century Iberia, especially Catalan liturgical manuscripts (Figure 25.1).11 Style A is characterised by an emphasis on draughtsmanship over colour – a two-dimensional linearity that renders figures in a hieratic, anti-illusionistic manner, with facial features and clothing stylised to have an elaborate ornamental rather than naturalistic effect. The other, which I call ‘style B’, is exemplified by the LFM’s frontispiece and circular composition (Figures 25.2–25.3). This set of illustrations, which was carried out by at least two artists, points towards the novel formal developments associated with the so-called Year 1200 and Gothic styles. Figures are comparatively elongated and their gestural interactions are more nuanced and diverse. Whereas surfaces in style A are articulated with schematic meanders and geometricised shapes, in style B drapery is defined through the application of bold pigment overlaid either with striations and swirls or textile patterns. The question remains, however, as to the amount of time that might have elapsed between these two campaigns. The LFM was certainly meant to be illustrated from its inception, for its scribes allotted spaces for images as they executed their work in the early 1190s. It is reasonable to assume that the style-A illustrations were carried out in these same years or immediately thereafter. We must then consider whether there was a significant break in production, with the artists responsible for style B working on the manuscript as late as the 1220s, as certain scholars have suggested.

My own investigations have led me to conclude that the tendency to assign the year 1220 to the LFM as either an approximation or a terminus ante quem should be re-evaluated. Despite their stylistic similarities, there is no evidence that the cartulary of Barcelona and the Beatus of Las Huelgas shared a hand. David Raizman, the foremost expert on the Las Huelgas Beatus, has concluded as much:

‘Similarities are of a generalized rather than specific type, and appear superficial upon closer inspection, related only in their adaptation or transformation of Byzantinizing tendencies… . Differences in drawing, poses and heads, and especially in modeling, are too great to suppose an identity of authorship between these two manuscripts.’12

Moreover, we can point to other illuminated books dated to the late 12th century that are no less similar in style to the LFM. Two manuscripts now in the National Library of the Netherlands, dated by Walter Cahn to c. 1180 and the late 12th century respectively, exhibit resonances with LFM style B that remain unexplored: a psalter which can be connected either to Fécamp or Ham (The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, MS 76 F 13) and a psalter fragment connected to the Abbey of Saint-Bertin in Saint-Omer (Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, MS 76 F 5) (Figures 25.5–25.6).13 While these manuscripts may not share a hand with the LFM, the commonalities evident in their treatment of bodily proportions, facial features, drapery and architectural frames testify to a shared stylistic vernacular – one passed from masters to students/assistants and disseminated on both sides of the English Channel and into the Iberian peninsula by itinerant artists. The Fécamp Psalter would represent an early incarnation of this idiom, and the Las Huelgas Beatus a late example. As for LFM style B, I contend that the scenario of patronage at the court of Barcelona makes a dating of c. 1200 more likely than c. 1220.

With this chronological shift in mind, we should return to the curious coexistence of the LFM’s two pictorial styles. How might we ‘diagnose’ this stylistic juxtaposition? One possible explanation is that the death of the manuscript’s patron resulted in an interruption in its illustration and a subsequent change in style; we might then speculate as to who would have stepped in to take up the project and hire the second group of artists.14 Following this hypothetical scenario, there are three likely candidates for the role of ‘substitute patron’. The first and perhaps most convincing is Ramon de Caldes (d. 1199), who as the head of Alfonso’s chancery was responsible for the compilation and is lionised in the frontispiece. Assigning the role of ‘patron’ to Ramon, however, might not be entirely appropriate in the sense that he would not have provided funds himself, but may have distributed them as an intermediary between the crown and the artists. Whether before and/or after Alfonso’s death, Ramon may also have directed the cartulary’s iconographic programme, and even memorialised himself by requesting his presence in the chancery scene. In any case, it is difficult to imagine Ramon featuring so prominently in the frontispiece had it been painted twenty years after his death.15 The monumental treatment afforded Alfonso’s archivist in this painting only makes sense in the context of his direct involvement in the making of the cartulary. There is, however, a second possibility, which is that work on the cartulary was taken over by Alfonso’s wife, Queen Sancha of Castile (d. 1208), who served as regent following the death of the king and was the primary patron of the Hospitaller monastery of Santa María de Sigena in Aragon, known for its Byzantinising chapterhouse frescoes. It may be Sancha herself who is depicted in the manuscript’s other full-page illumination, the radial throne scene (Figure 25.2); if the queen regent did indeed take over the decoration of the cartulary, she might have instructed the painters to memorialise her and her dead husband with this apotheotic composition. A third possibility is that Alfonso’s son and successor, King Pedro II el Católico (d. 1213), commissioned a second series of illuminations after he came of age.16 The text of the LFM was, in fact, updated during his reign, with Pedro’s scribes making use of the blank folios that had been strategically included to ensure that the manuscript could be kept up-to-date.

On the other hand, having wrested the LFM from its ties to the year 1220, we might consider an alternative scenario: that there was no ‘patronal break’ at all, nor any significant chronological separation between LFM styles A and B. To some extent, the tendency to temporally distance the cartulary’s two styles is informed by art historical narratives that presume a linear, teleological model of stylistic progress – according to which ‘Gothic’ is regarded as the successor to, and an improvement on, ‘Romanesque’. In the case of the LFM, the coexistence of two distinct illustrative modes has prompted art historians to reveal a conspicuous bias in favour of one over the other: specifically, the more naturalistic style B over the more abstract style A. This preference dates back to the survey of medieval Catalan painting written by Josep Gudiol i Cunill (1872–1931), who described the more Romanesque illustrations in the LFM as ‘the most barbarous [style] imaginable’ – the product of a ‘very bad hand’ that can’t help but create ‘deformed’ figures.17 Regarding the image illustrating the oath of fealty made by the men of Melgueil (today Mauguio) to the Count of Barcelona (fol. 85r; Figure 25.1), Gudiol writes: ‘If ever the men of Melgueil saw the drawing in question, they would be none too pleased to find themselves represented in such an excessive manner’.18 Gudiol’s comments are extreme almost to the point of comedy, and I think we can rest assured that the medieval citizens of Melgueil are not rolling in their graves over their depiction in Alfonso’s cartulary. Yet the derogatory attitude underlying his assessments has survived even today, with recent art historians describing the style A illustrations as ‘archaising’, ‘mediocre’ and ‘inferior’ to style B, which is lauded as ‘superior’ or of ‘higher quality’.19

Such assessments amount to an erroneous conflation of style and quality, one that is at odds with the trajectory of art history in recent decades, as value judgements concerning artistic beauty and quality have been justifiably problematised. I propose that the LFM’s stylistic pluralism should instead be interpreted as a demonstration of medieval viewers’ ability to appreciate a variety of representational strategies, even within a single work of art. The Barcelona cartulary is hardly unique among medieval works in incorporating multiple styles, whether carried out in quick succession or over the course of long stretches of time: the mid-12th-century Winchester Psalter and the Parma Ildefonsus of c. 1200 also combine Romanesque and Byzantinising illuminations, while the cloisters of Silos, San Juan de la Peña and Elne integrate different sculptural styles.20 Given the persistence of Romanesque pictorial and architectural traditions on the Iberian peninsula, we might view LFM style A as an alternative contemporary style rather than an archaising or outmoded, let alone faulty, one.21 One particular idiosyncrasy of the LFM supports this reading: remarkably, on two folios (23r and 109r) we find both styles combined within a single illustration (Figure 25.7). In each case, the artist responsible for style B painted multiple vassals over the single vassal drawn by his predecessor. The fact that only the left half of the illustration was painted over, and the enthroned lord left behind, suggests that medieval audiences were untroubled by certain styles being ‘retardataire’ or ‘archaising’ (to use terms frequently employed by art historians). Whether this repainting was done weeks or years after the execution of the original images, we cannot be certain. But in either case, we should view this cartulary’s two styles not as different stages of a teleological formal development, but rather as equally legitimate, coexisting artistic expressions.

While the precise chronology of its decorative programme remains elusive, the LFM’s incorporation of the unreservedly Romanesque style A and the comparatively modern style B brings to the fore issues of patronal intent and the medieval reception of style. Questions concerning the cartulary’s patronage also have methodological implications. Is it preferable to date artworks and buildings through formal analysis, or by focussing on cultural and socioeconomic factors such as patronage? Can a social history of art lead to more accurate conclusions than the ‘old-fashioned’ style-based methods of the discipline? Over the past several decades, art historians have sought to problematise the Romantic view of the artist as creator-genius; medievalists, facing a dearth of artists’ signatures, have in many cases adopted the study of patronage as a means of analysing artworks as products (and perpetuators) of social and economic forces.22 Problems arise, however, when the role of the patron is aggrandised, and he or she is upheld as the primary author-genius responsible for an artwork; one thinks of the debates over the role of Abbot Suger at Saint-Denis, for instance.23 Dare we declare the death of the patron as the literary theorist Roland Barthes did for the author?24

In several recent studies, historians of art and architecture have sought to destabilise assumptions about patronage and agency. Jill Caskey has spoken of an expanded ‘patronal field’ in which works were commissioned by individuals acting within the context of a larger ‘cultural fabric’.25 Stephen Perkinson has identified patronage as more ‘diffuse’ than is often assumed, involving not only the commissioners who supplied funds for projects but ‘conduit[s]’ responsible for distributing those funds to labourers such as scribes and artists; such intermediaries might themselves exercise control over imagery to some degree.26 And Aden Kumler has encouraged us to consider patrons not just as initiators but as ‘effects’ of artworks, following Foucault’s model of the ‘author-function’, according to which an author is not so much an individual creator as a discursive entity giving rise to ‘a series of egos or subject-positions’.27 These and other studies have been helpful in critiquing and nuancing art historical narratives of patronage, but we should also avoid applying the term too broadly. There is, I believe, a value in maintaining a narrow economic definition of the patron as a provider of capital, while framing medieval artistic production in terms of a multiplicity of different types of makers: scribes, artists, designers, masons, architects and patrons alike.28 This resists the modernist tendency to seek an overarching creator-genius responsible for a given artwork or building, while also noting the special power of the individual who possesses the material means to commission art and architecture. Patronage thus remains a useful line of inquiry because it helps us glimpse how rulers constructed their identities and their legacies in order to support their ideological aims. But as recent studies have emphasised, we must bear in mind that the making of medieval art involved complex interactions between donors, designers, artisans and audiences, with each party exercising a varying degree of control depending on the circumstances.

The collective nature of medieval artistic production is brilliantly illustrated by the frontispiece of Alfonso’s cartulary, which highlights the extent to which royal patronage was an institutional activity rather than an individualised one (Figure 25.3). The network of gazes and gestures performed by the various figures clearly articulates the contribution of each: the king commands the production of the cartulary; the dean of the cathedral serves as archivist and designer; the amanuensis transcribes the documents and converts them into a codicological format; and the six courtiers testify to the legitimacy of the entire process and, by implication, represent the cartulary’s future readers. Given its emphasis on patronage as process, this illumination might be compared to the well-known image in the Toledo Bible Moralisée depicting that book’s patron(s) and producers (colour plate XXII).29This full-page miniature – which dates to the late 1220s or 1230s and is therefore later than the LFM – is organised according to an ‘upstairs/downstairs’ architectonic scheme, with the royal figures responsible for the commission at the top and the manuscript’s creators below. Each of the four figures is isolated within a discrete space defined by a trefoil arch: reading left to right and top to bottom, we find the book’s patron, Blanche of Castile, Queen of France; its likely recipient, her son, King Louis IX; a secular cleric consulting a codex and issuing iconographic instruction; and finally a lay artist completing the mise-en-page of one of the folios.30 As Aden Kumler has noted, the composition describes the creation of the manuscript as ‘embedded within, and productive of, a profoundly relational social, intellectual, and aesthetic economy’.31 The book is portrayed not as the product of a single artistic or patronal genius, but as a truly collaborative endeavour.32

This collaborative dimension is heightened in the LFM frontispiece, which dispenses with architectural divisions and presents the participants within the same ambit (Figure 25.3). By constructing an ostensibly realistic glimpse into Alfonso’s chancery, the illuminator unites the book’s various makers according to their common goal. The king’s open right hand, like Blanche’s left hand, demonstrates his agency as the book’s patron, while the sceptre in his left underscores his royal prerogative to commission a project of this type. And much like the cleric in the Toledo Bible, the Augustinian canon Ramon consults a text and raises an index finger, indicating that he is actively articulating his plans for the codex. The parchment Ramon holds aloft, like those piled below (as well as that on the scribe’s desk), bears legible Latin script, all of which correspond to texts copied within the LFM itself.33 While most of these meta-documents are oaths and agreements, that in Ramon’s right hand is identifiable as a judgement (iudicium). The fact that it is the only judgement in the painting invites us to interpret it as a canny allusion to the wisdom Ramon has exercised in the selection and arrangement of the cartulary’s contents.34

While King Alfonso is indisputably the cartulary’s patron, we might identify Ramon de Caldes with Beat Brenk’s notion of the ‘patron-concepteur’ – the intellectual director or designer of a given project as opposed to the provider of funds.35 That Ramon had the intellectual sophistication required for such a task is made clear by the erudition of his prologue, in which he creates playful patterns with word order and quotes the Justinianic Corpus Juris Civilis. Each side of the folio thus highlights Ramon as a spokesman for the cartulary: the recto depicts him speaking, while the verso records his words. Moreover, both recto and verso, image and text distribute credit for the book to both Alfonso and Ramon. The prologue specifies that the king was responsible for the cartulary insofar as he expressed a wish (viva expressistis voce) that Ramon compile the documents drawn up during his own reign and the reigns of his ancestors, to preserve the memory of past deeds and prevent future conflict.36 Ramon then goes on to describe in detail his methods of compilation, barely able to contain his pride at having completed this massive project in such an organised and comprehensive fashion, but careful to insist – in feigned humility – that he elaborates thus ‘not to boast, but to express the truth’.37 For it is ultimately to the glory of the patron that he has dedicated his labour, to ensure eternam magnarum rerum memoriam – the ‘eternal memory of great things’.

I would like to thank Manuel Castiñeiras, Abby Kornfeld, Therese Martin, and Kathryn Smith for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this essay. I am also grateful to the staff of the Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, especially Albert Torra, for allowing me to view the Liber Feudorum Maior on two separate occasions over the course of my dissertation research.