Chapter 7

Then Shall They Be Gods

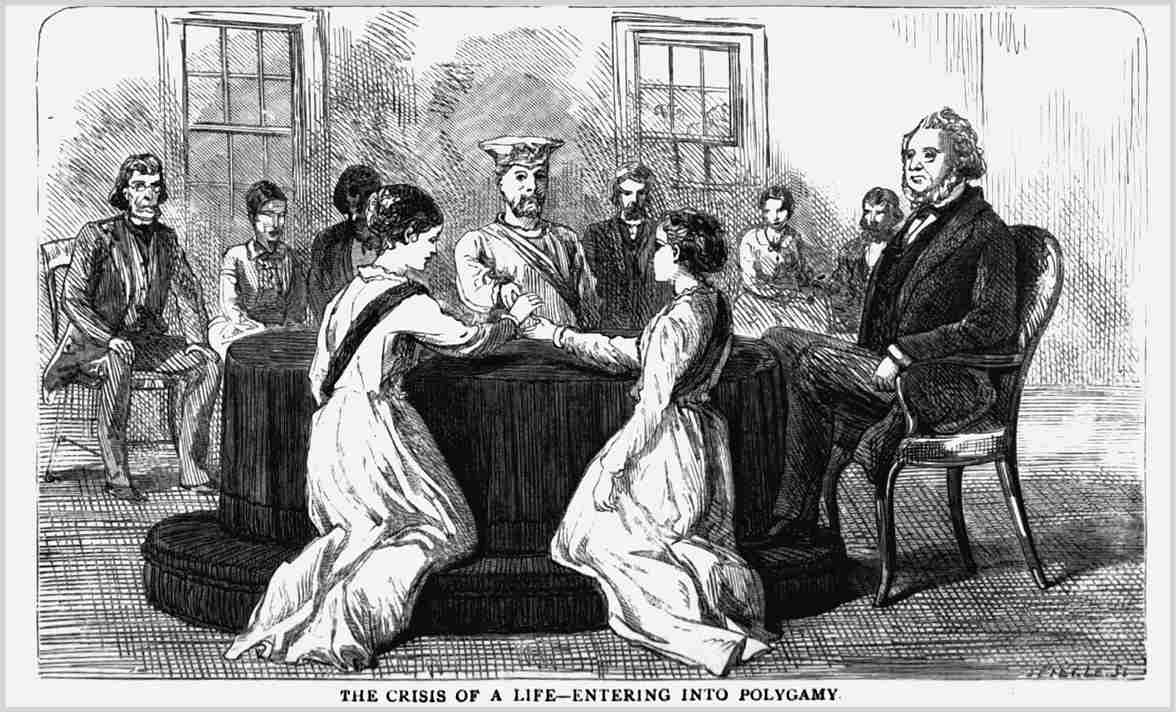

Fanny Stenhouse’s memoir about her twenty years’ experience as a polygamous wife to a Latter-day Saint was one of many sensational depictions of Mormon marriage as a form of slavery for women, a portrayal that members of the LDS Church vehemently disputed.

The summer air in Nauvoo, Illinois, was thick with gossip about sex.

It was 1842, and the followers of Joseph Smith, the prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, had lived in Nauvoo only since 1839. The Latter-day Saints, or Mormons, had followed Smith from upstate New York to Kirtland, Ohio, and then to Independence, Missouri, where local authorities grew increasingly wary of Smith’s plans to build an autonomous society. When mobs threatened Smith, he and his followers once more went in search of an enclave of their own. They believed they found it in Nauvoo (formerly called Commerce), which occupied land that the U.S. government had seized from the Sauk people in the 1810s and sold to white speculators. Smith was optimistic. Here, he declared, the Mormon church would build its Zion according to the divine revelations he had received and which had become the Book of Mormon, their sacred text. Wilfred Woodruff, one of Smith’s closest associates (and future church president), envisioned the nascent settler community as “the kingdom of God.” At first, only Smith’s closest confidants knew that the Zion they were building included unorthodox sexual arrangements.1

The beginnings and eventual demise of Mormon polygamy prompted a transformation in how the federal government responded to sexual nonconformity, one step in the dramatic investment of local, state, and national government agents in the regulation of sexuality from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s. Sex and sexuality during these hundred years became increasingly integral to American governance, with the Comstock Act to ban “obscenity,” police vice squads arresting suspected sex workers or “deviants,” and progressive reformers looking for ways to reform “delinquent” youth. Individuals began to see their desires as sources of their personal identities—and challenged regulations that got in the way of expressing them. Young people socialized more often in mixed-sex groups, away from their families, and enjoyed the recreational pleasures that money could buy. Sexual modernity celebrated the individual pursuit of pleasures and considered a person’s desires to be a reflection of their fundamental nature. Fantasies of racial difference, whether in the response to the LDS church or through the emergence of queer subcultures in American cities, shaped the creation of that modern sexuality, too.

Mormon polygamy was one of several dramatic attempts to widen the parameters of sexual morality in the nineteenth-century United States. The iconoclasts considered in this chapter—not only within the LDS church but also among free lovers and the Oneida Perfectionists—led the first collective efforts in the United States to build the world anew by rewriting the rules about sex. Their challenges to convention far surpassed the provocative booklets that Fanny Wright distributed about contraception or Sylvester Graham’s lectures about the solitary vice. Mormons, free lovers, and Oneida Perfectionists defied laws that privileged monogamous marriage, and each claimed to liberate women from traditional marriage’s oppression. Ironically, their efforts prompted the U.S. government to assert its authority over intimate relationships in ways that amplified white men’s marital authority, just as the government was also demanding marital monogamy among Indigenous people.

When Smith and his followers arrived in Nauvoo, the U.S. government was a whisper of the size it would attain by 1896, the year that Woodruff received a new revelation calling for an end to the church’s unconventional marriage practices. State legislatures, not Congress, set and enforced laws related to marriage, divorce, and sex (as they still do). But as the government in Washington expanded its enforcement powers across the nineteenth century, adding agencies to administer the Civil War and care for widows and the wounded after it ended, it also asserted a new role as an arbiter of the nation’s sexual morality. The federal government’s investment in marital monogamy was unprecedented.

In places governed by federal authorities, such as the Utah Territory, where Smith’s followers later settled, and on Indian reservations, Washington legislators and bureaucrats attempted to do in the second half of the nineteenth century what missionaries had pursued in the seventeenth and eighteenth: eliminate polygamy through incentives or, if necessary, force. The government demanded that Mormons, Indigenous people, and other nonconformists adhere to a monogamous marital norm. In reality, fidelity and monogamy were hardly the rule in the mid-nineteenth-century United States. Westward migration promised both land and personal reinvention, as tens of thousands of people rode or walked in search of opportunity. Untold numbers of Americans committed de facto bigamy when they deserted spouses and moved across the ever-growing expanse of U.S. territory to marry again. Men enjoyed greater freedom to travel and were far more common sights along the rough roads and unmarked trails west, but women picked up and left their homes too. (Gender-variant people made these journeys as well, often arriving at their destination as the woman or man they understood themselves to be, a subject that Chapter 8 discusses.) When agents of the U.S. government forced Indigenous people to live on single-family farms rather than reservations or arrested Mormon men for adultery, they insisted they were doing it for the people’s own good.2

The alarming reports emanating from Nauvoo inspired a series of federal actions—military deployments, legislation, and judicial decisions—that asserted the responsibility of national leaders over intimate living arrangements. Critics of polygamy portrayed it as a kind of slavery that subjected women to powerful men’s obscene desires. A great deal of erotic fantasy circulated in these ostensible arguments against polygamy. But monogamy did not win the day on the strength of these arguments alone. The Latter-day Saints held out for decades and relented only after the federal government stripped them of nearly all their assets. These intense conflicts over sexual behavior contributed to an idea of sexuality that was just beginning to take shape. Like many Americans, the Mormons understood desire as a reflection of a person’s soul. But over time, the national preoccupation with polygamy helped magnify sex’s importance to American governance and, eventually, to individual identity.

In a clandestine temple ceremony in 1841, a member of the all-male LDS priesthood “sealed” Smith and Louise Beman in “celestial marriage” that would endure, they believed, for eternity. The following year, Eliza Snow, one of Smith’s most faithful followers and a leading figure within Mormon women’s organizations, was also sealed in celestial marriage with Smith. Sisters Zina Jacobs and Presendia Buell each already had a husband when they received the priest’s blessing for their sealing with Smith. Mormons soon learned that a woman married “for time” to a Gentile (as they described the unconverted) or to a fellow Latter-day Saint could yet marry “for eternity” a man whom Smith had anointed a priest in a special temple ceremony. To Smith and his followers, temporal laws mattered little compared to God’s blessings (mediated through his prophet, Joseph Smith). By 1844, Smith had wed more than thirty women, and about 100 of his 12,000 followers (perhaps 3,000 of whom were women of childbearing age) practiced celestial marriage.3

In this life, Smith was already married to Emma Smith, who initially knew nothing about these covert rituals. When Emma got wise to her husband’s behavior, she was furious, possibly even threatening to have extramarital affairs. According to one of Joseph’s friends, “She thought that if he would indulge himself she would too.”4

Critics within the growing Mormon community sounded the alarm. They amplified the rumors of extramarital sex and bigamous marriage, and they portrayed Smith as a louche seducer. Newspaper exposés written by Gentiles and former Latter-day Saints alleged coercion and abuse, including the story of a woman trapped in a room for two days until she assented to a plural marriage.5

Formerly faithful disciples rejected polygamy and urged a return to Smith’s prophecy “as originally taught.” Smith refused. He led both his church and the Nauvoo government, had a militia that reported to him, and foresaw the creation of a Mormon theocracy. When the Nauvoo Expositor, a dissident press, voiced critiques, Smith had the Nauvoo city council, which he controlled, declare the newspaper a public nuisance, and its presses were destroyed.6

On June 27, 1844, Smith, his brother Hyrum, and other members of his inner circle were arrested and taken to Carthage, the county seat, on charges of destruction of public property. Outraged over Smith’s combined affronts to monogamous marriage and the rights of Gentiles, a mob stormed the jail and shot into the second-story cell that held Joseph, Hyrum, and their companions. Injured, Joseph leapt from a window to his death below.7

Brigham Young, a close disciple of Smith, claimed the mantle of prophecy from his mentor and led the Saints out of Nauvoo. Beginning in 1847, thousands of Latter-day Saints made the “trek” to the Great Salt Lake Basin, hoping to elude agents of both state and federal law enforcement. When the area that Young and his followers settled became part of the Utah Territory in 1850, the church once again had to contend with federal authority.8

Latter-day Saints in the Utah legislature created a novel legal system that exempted the spouses within polygamous marriages from common-law prohibitions on bigamy. They also established wider grounds for divorce. Laws governing marriage in the rest of the United States still limited married women’s legal personhood; coverture restricted married women’s rights to property and wages. Mississippi’s legislature in 1839 and New York’s in 1848 passed Married Women’s Property Acts that allowed wives to own property in their own names, but these laws were exceptions. New York did not allow wives to retain their wages until 1860. These impediments to women’s equality had dire consequences for women in abusive marriages. The temperance movement that formed in the 1840s drew attention to the predicament of wives whose husbands suffered from “habitual drunkenness.” These women, activists argued, needed options foreclosed by the legal principle of marital unity, which presumed that a husband owned his wife’s body. Some mid-nineteenth-century judges even continued to define rape as “tolerable cruelty” that did not abrogate a husband’s marital rights.9

Missionaries for the LDS church pointed to the limitations of American marriage law. They advertised polygamy as one of the benefits of conversion—a virtuous union that, they argued, gave women more rights than traditional marriage did. New converts poured in from Canada and Europe, and for many of them, men and women alike, polygamy was part of the draw. The prospect of entering a marriage in which one man had licit sexual relations with more than one woman appealed to them. Polygamy, they argued, was a purer expression of human sexuality than monogamy because it prevented naturally lustful men from seeking out sex workers or carrying on clandestine affairs. Others viewed polygamy as a religious duty, a sacred obligation that proved their devotion to divine truths. Some women left the church because of polygamy, but most stayed.10

Women who converted to the Mormon church before Joseph Smith introduced celestial marriage often had the most difficult adjustments. Vilate Kimball was forty-three years old in January 1850 when she gave birth to her tenth child. This was Vilate’s final pregnancy, but that year and the next, her husband, Heber, fathered nine more children by eight other wives. When Vilate complained, Heber urged her to appreciate the larger purpose of celestial marriage: “What I have done is according to the mind and will of God for his glory and mine so it will be for thine,” he explained. As one of Joseph Smith’s original apostles, Heber reminded Vilate that celestial marriage was from God: it sanctified the temporal patriarchy that oversaw all aspects of both Mormon religious practice and government.11

White Americans had long associated polygamy with the “heathens” of Indigenous nations and “infidels” in Arabia. The boundary between moral monogamy and licentious polygamy was marked by racial as well as religious differences. Anti-Mormon diatribes portrayed Smith, Young, and their followers as heathens and harlots who pretended to promote a well-ordered patriarchy when they in fact cultivated an immoral “harem” beset by sexual anarchy. “This Bluebeard of Salt Lake City,” one paper warned, had been “lecturing his own harem” to accept polygamy. Young, the article continued, “bawls to his sultanas . . . to depart, if they are not contented . . . But where are these Hagars to go?” The message was clear: Christian self-control, combined with the superior intellect allegedly possessed by those of European descent, should enable Christian men to control their lust.12

Latter-day Saints argued that it was monogamy that caused sexual immorality. Polygamy in this life, they explained, enabled patriarchs and the women who devoted themselves to bearing and raising their children to achieve exaltation in the hereafter. Their philosophy of marital sex combined a celebration of bountiful reproduction with criticism of what they considered sexual excess. Polygamy’s defenders argued that plurality prevented prostitution, even as they denied that they practiced polygamy out of lust. Man’s desires originated with God, they said, in the call to be fruitful and multiply, so it was duty, not desire, that called them to plural marriage. To critics who condemned Latter-day Saints for making virtuous women into prostitutes and trapping them within harems, the church’s defenders countered that polygamy honored women by making marriage and motherhood available to nearly all.13

One of the most damning criticisms of Mormon polygamy compared it to “free love,” a phrase first employed by northeastern and mid-Atlantic newspaper editors in the 1820s to describe adulterers, bigamists, and polygamists—anyone having sex with a person of another sex to whom they were not married. Marriage reformers themselves disagreed about free love’s meaning. A few free lovers were “varietists,” embracing a romantic philosophy that did away with commitment, while others advocated for the ability to exit an unhappy marriage and remarry according to one’s affections. Any of these options would have necessitated massive changes to American divorce law, which varied dramatically from state to state in the mid-nineteenth century just as it had in the 1790s when Abigail Abbot Bailey’s husband deserted her in New York, where divorce was difficult to obtain. By the 1850s, Connecticut and Indiana were both considered “havens” for dissatisfied spouses due to their relatively liberal divorce laws. South Carolina, by contrast, provided no means of legal divorce.14

Like the health reformers who warned about the hazards of the solitary vice, free lovers preached restraint. Sex radicals throughout the United States asserted that because marriage without love was the real adultery, lack of affection should be grounds for legal divorce. Some went further in their critique of marriage by warning, as temperance reformers did implicitly, that women in abusive marriages experienced rape.15

Two of the most notorious free-love radicals were Mary Gove Nichols and Thomas Low Nichols, whose book Marriage (1854) argued against marital monogamy. Having endured an awful first marriage to a man whose sexual demands she found loathsome, Mary Nichols was inspired by the lectures of Sylvester Graham to take to the lecture circuit herself. She wrote and spoke about the necessity that wives be able to refuse sex with their husbands. Here the similarity to Graham ended. When Mary and Thomas married in 1848, their wedding vows pledged fidelity of love but not sex. Thomas took an even more remarkable position about the naturalness of sexual self-expression, writing in support of consensual sex between men. However commonly men had sex with men in the mid-nineteenth century, Nichols’s position was exceptional. In 1853, Mary and Thomas resided at Modern Times, a utopian community on Long Island of about one hundred people drawn to its founders’ ethos of “individual sovereignty.”16

These free lovers prioritized women’s right to sexual consent and mutual pleasure but deplored “sensualism,” by which they meant loveless lust. Love, not marriage, they argued, sanctified sex. Free lovers additionally sought an end to the sexual double standard by legitimating women’s sexual desires, endorsing coitus interruptus or postcoital douching to unburden women of the fear of continual pregnancies. Their inclusion of women’s pleasure in the campaign for women’s equality was radical. Not until the twentieth century would movements for women’s equality in the United States return to these ideas about the importance of women’s sexual gratification.17

These nuances aside, “free love” was more often invoked to tarnish another person’s reputation than to affirm a new kind of sexual liberty. Dozens of antipolygamy novels characterized free love and the Mormon church as catalysts for sexual chaos. To be sure, when Brigham Young argued that marriage required affection, and that a marriage without it offered grounds for divorce, he sounded much like free lovers on the East Coast. Augusta Cobb, who left a husband in Boston to marry Young, similarly explained “that the doctrine taught by Brigham Young was a glorious doctrine for if she did not love her husband it gave her a man she did love,” a sentiment that echoed free lovers’ principles. (Back in Boston, her husband divorced her on grounds of adultery.)18

“Free love” and polygamy became epithets during the sectional crisis of the 1850s and 1860s. For decades, northern critics of slavery had decried the “harems” that white Southern elites formed with enslaved women. In 1856, the Republican Party platform condemned the “twin relics of barbarism,” slavery and polygamy, blaming each for elevating the powers of corrupt patriarchs. This ideology esteemed male-female marriage, by contrast, as the antithesis of the sadism and suffering they associated with Mormon households. Apologists for the South, meanwhile, cast Northerners as dissolute free lovers. The New York Herald, which favored the pro-slavery Democratic Party, in 1857 insinuated that white men in the antislavery movement had “free love” in mind when they supported Black women’s abolitionist societies.19

One of the founders of Modern Times, Stephen Pearl Andrews, took what we would today consider a libertarian approach to sex, arguing for removing the state from intimate decisions. Ready to take on any of free love’s opponents, Andrews found a new voice for his theories in the early 1870s when he met Victoria Woodhull. Much like Mary Gove Nichols, Woodhull had survived a miserable first marriage and remarried, setting up an unconventional household in New York City that included her first husband, Calvin Woodhull (who was an ailing alcoholic), and her second husband, Col. James Harvey Blood, as well as her mother, children, and sister Tennessee Claflin. Woodhull and Claflin worked their way into the good graces of millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt, who gave them enough money to open a brokerage (the first in the United States owned by women) and launch a newspaper. Andrews began to provide Woodhull with content for the paper, often published under Woodhull’s name, to circulate his free love ideas. Woodhull was a believer; “Yes, I am a free lover,” she announced in 1871, an unscripted moment during a lecture otherwise authored by Andrews. Like Andrews, she was a varietist who believed that for sex to be pure it must be a spiritual meeting of two souls.20

Yet even radical free lovers held fairly conventional views on the importance of sexual purity. They typically had little to say about race or slavery, aside from invoking it as an analogy for women’s status within marriage. Instead, they addressed their philosophy to a presumptively white audience. Nor did free lovers challenge ideas about the fundamental differences between men and women. They assumed that men had much stronger desires for sex than white women did. Despite accusations of debauchery, free lovers were, to the contrary, usually opposed to masturbation and libertinism. Male sexual excess resulted, they believed, when husbands ignored their wives’ desires. Mutual love, by contrast, would nurture a healthy sexual restraint and reinforce sexual purity.21

A communal experiment led by John Humphrey Noyes in Oneida, New York, lay much further outside the mainstream. Calling themselves Bible Perfectionists, the Oneidans never numbered more than a few hundred people, although the abundant newspaper coverage they received brought them considerable attention. Noyes trained at Yale Divinity School but was expelled when he declared to his classmates that he had discovered the way for men and women who had been reborn in Christ to become morally “perfect,” incapable of sin. From the late 1840s through the late 1870s, the Oneida Community practiced “Bible Communism” in their housing, wages, child rearing, and male-female sexual encounters. Much as free lovers had, Noyes compared marriage to slavery, an exclusive arrangement that subjected individual affection to the whims of state control. Unlike free lovers, Noyes abolished monogamy in his community. He taught his followers that spiritual perfection rendered secular marriage laws irrelevant.22

Noyes created a radical sexual system he called Complex Marriage. Every adult male in the Oneida community was a potential sexual partner of every adult or adolescent female there. Noyes and other adult males sexually initiated girls once they reached puberty, and he argued that the Bible did not prohibit sex between nieces and their uncles. Complicating matters, Noyes dictated every male-female pairing. Fanatical about his rule that all adolescent girls and women remain available to all adolescent boys and men, Noyes broke apart couples when the partners grew too attached or exclusive—“sticky,” in the community’s terminology. Sexual frequency and variety were intrinsic to his theology; intercourse should not occur only for the purposes of procreation, he explained, but instead was essential for moral communal life. Noyes preached that sex elevated lovers to heights of spiritual perfection. Such a system, of course, would require men to have sexual intercourse frequently and with as many adolescent girls and adult women as possible while avoiding perpetual pregnancies, which put women’s lives at risk. (Noyes’s own wife, Harriet, had five difficult pregnancies that resulted in only one live birth.)23

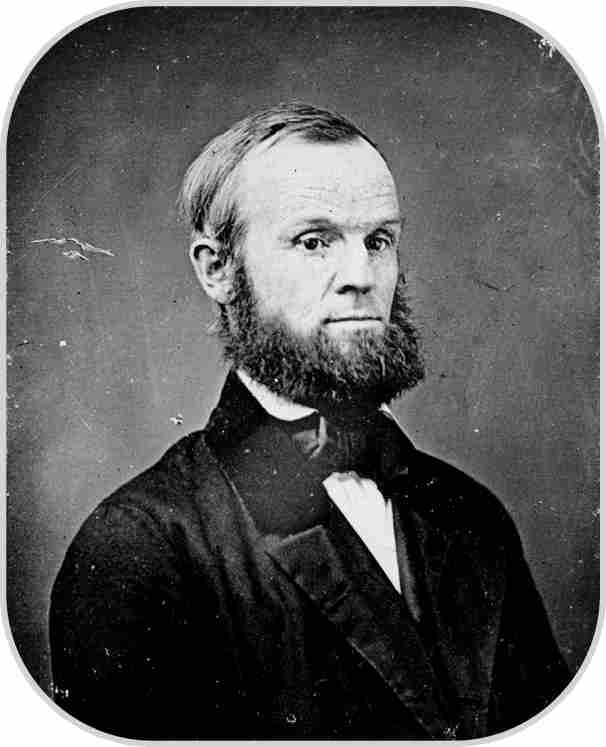

John Humphrey Noyes (1811–1886), pictured here in the 1850s, was the leader of the Bible Perfectionists in Oneida, New York. In Noyes’s view, intercourse should not occur for the purpose of procreation only but also for personal enjoyment and the pursuit of spiritual perfection. In fact, most sex had at Oneida was not reproductive; Noyes demanded his male followers practice coitus reservatus by not ejaculating during intercourse and thus avoiding unwanted pregnancies.

It was not simply that Noyes controlled who would have sex with whom; he also wanted to regulate how men and women had sex. Ejaculation, he warned, was “a momentary affair, terminating in exhaustion and disgust.” He urged his male followers to practice coitus reservatus, controlling their desire by not ejaculating during intercourse. Men who mastered this technique, he explained, could enjoy “social” or “amative” sex, in which the male partner stopped before the “going over the falls” of the “ejaculatory crisis” and orgasm. Like a sort of tantric sex coach, Noyes taught men to “choose in sexual intercourse whether they will stop at any point in the voluntary stages of it, and so make it simply an act of communion, or go through to the involuntary stage, and make it an act of propagation.” Noyes believed that this practice would enhance rather than dim the enjoyment of sex. He argued that it was the “action of the seminal fluid on the internal nerves of the male organ,” not orgasm, that produced male pleasure. Noyes said nothing about how women experienced penetrative “presence” or about any connection between the man’s “muscular exercise” and a female partner’s pleasure.24

Noyes apparently found ejaculation a revolting and demoralizing experience. Nor did he advocate for masturbation as a healthy way for men to release their sexual energies, calling it a “useless expenditure of seed.” Contemporary anti-masturbation reformers such as Graham and Sarah Mapps Douglass would have agreed with that much, but they held few other beliefs in common. While Graham and Douglass recommended marital “continence,” or restraint, Noyes had other ideas.25

The sexual system at Oneida was pedantic and intrusive, but for enthusiastic members of the community, it was a source of tremendous sexual satisfaction. Tirzah Miller was Noyes’s niece—and one of his favorite sexual partners. After one encounter, when Miller would have been about twenty-five and Noyes about fifty-seven, he praised her for being a sexual partner with “an immense . . . power to please sexually”: “I always expect something sublime when I sleep with you.” She returned the compliment. When her uncle declined to have sex with her or her friend Mary one evening in order to sleep with two younger women, Tirzah wrote that she was “glad we were out of the way, so that those other girls could get the same benefit from association with him that we had.” The following evening, when he asked Tirzah to once again share his bed, she was euphoric: “I never realized so much as I have to-day what a life-giving thing it is to have fellowship with him. I had an unusually nice time.” Miller was known among the members of the community for her sensuality, and she appreciated the myriad opportunities that her uncle’s philosophy afforded her for sexual experiences with a variety of men.26

Scandalized observers of the Bible Communists and of the Latter-day Saints characterized them both as harems and the women who lived in these communities as prisoners, and readers of these pages might agree. Such an interpretation renders Tirzah Miller’s enthusiasm for the Oneida system and Augusta Cobb’s eagerness to become one of Brigham Young’s plural wives as delusional responses to a charismatic but predatory leader. Those two things may have been true, to varying extents. But it would be wrong to deny the agency of at least some of the women who gravitated toward and stayed in these religious groups for any period. Among the sexual options available to them at the time, they chose polygamy and Complex Marriage.

Among the most controversial innovations at Oneida was “stirpiculture,” a proto-eugenic experiment Noyes began in the 1860s. He permitted certain men and women to have procreative sex if he believed they would conceive a spiritually elevated child. Generations of selective breeding would bring his community closer to perfection, the pinnacle of which, he taught, was immortality. Noyes suggested that his system gave women a measure of control to “bear children only when they choose,” but he alone decided which male-female pairs should take part. Quite often, he chose himself: he was the father of ten of the sixty-two children born of this plan between 1869 and 1879.27

Complex marriage and stirpiculture strained Oneida’s cohesion. Some community members preferred the option of sexual exclusivity, while others simply wanted Noyes to stop determining their partners. After Noyes died in 1886, his nephew took control of the community, moving quickly to conceal evidence of stirpiculture from public view. A new generation of leaders remade Oneida as a profitable manufacturing center, its eponymous silverware cleansed of associations with sexual experimentation. Yet while Bible Communism fell apart, the Mormon church endured, albeit by making dramatic concessions to mainstream sexual norms.28

Polygamy locked Utah’s territorial government out of statehood. In 1862 Congress passed the Morrill Act for the Suppression of Polygamy, which criminalized bigamy in the territories and dis-incorporated the Mormon church. The law was unenforceable, and it was never challenged in court. Pressure on Mormon leaders intensified as Congress debated laws that would punish polygamists by confiscating their property, compel polygamous wives to testify against their husbands, and imprison polygamous husbands. The U.S. government grew more determined than ever to eradicate polygamy within its borders, marking it as a sign of “barbarism” unsuited to American democracy.29

Whether polygamy degraded women animated the national debate over women’s suffrage and Utah statehood. Women suffragists highlighted the stories of ex-Mormon women. They described the tyranny of patriarchal governance and the need for women to have an equal political voice. These activists characterized white women like themselves as innately more chaste than men and thus in need of the protective shield of the franchise. The Utah Territory granted suffrage to adult women in 1870, largely as a rebuke to critics who likened polygamy to female enslavement. To the shock and consternation of women’s suffrage advocates and anti-polygamists, Mormon women did not use the franchise to end polygamy but instead continued to defend it as a system that protected them from the misery of celibacy, enabled them to fulfill their obligation to procreate, and guarded Mormon men and women from the “degradation” of prostitution. Even better, LDS women argued, polygamy made men more virile and healthier while enriching their prospects for the afterlife.30

Difficult years followed for the Latter-day Saints. A series of congressional acts and court decisions threatened their property, disenfranchised most of the faith’s male adults, and dissolved the territorial militia. Perhaps even more damaging to Mormon morale, federal courts unleashed a torrent of sex-crime charges against them. Among the approximately 2,500 cases brought against members of the church between 1871 and 1896, more than 95 percent involved charges of fornication or bigamy. While many church leaders (who were all men) went “underground” to evade prosecution, from 1887 to 1890 more than two hundred Mormon women were indicted on fornication charges for pregnancies that resulted from relationships not sanctioned by legal marriage. In 1887, Congress passed the Edmunds–Tucker Act, which made adultery, incest, and fornication into federal crimes. By 1905, about 140 people in the New Mexico territory had been arrested for adultery. Those imprisoned, however, were overwhelmingly Hispanos who were not members of the Mormon church.31

The federal government extended its marital authority over Indigenous North Americans too. Many Indigenous people shared with the Latter-day Saints a tradition of polygamous marriage. Both groups populated the imaginations of white Christian Americans as bloodthirsty and uncivilized. Congress passed the Dawes Severalty Act the same year that it passed the Edmunds–Tucker Act. The Dawes Act was intended to end the reservation system and destroy Indigenous cultures by splintering communal lands into individual “allotments.” The law also sought to change families from within. It trained Indigenous men in various forms of wage work and sent home economics specialists to instruct Indigenous women in Euro-American domestic arts. At a time when other white Americans called for the extermination of Native Americans, “assimilationists” touted the salutary effects of the patriarchal household. As white “friends of the Indian” asked a reservation agent in 1890, peppering him with questions about life on the reservation, “Do they not sometimes grow manly, under the influence of having a family to work for?” The Dawes Act, much like the treatment of polygamous Mormons, inscribed sexual monogamy into federal law.32

The Kiowa people who lived on the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache (KCA) reservation in Indian Territory (today, principally Oklahoma) confronted those pressures. For white reformers and federal agents, Kiowa toleration of women’s premarital sexual autonomy, polygamy, and serial monogamy indicated cultural inferiority. For centuries, the Kiowa had organized their community according to topadoga (kindreds), in which the eldest brother was the leader. A topadoga might encompass twelve or fifty tipis, and their composition fluctuated when disputes, social visits, or marriages sent some people from one topadoga to another. Sororal polygyny (marriage to two or more sisters) strengthened the family unit and provided men with additional female laborers for the strenuous but essential work of preparing buffalo hides for trade.33

Much as white Europeans had two and three centuries earlier, assimilationists concluded both that Indigenous women were mistreated and that they were promiscuous. They disparaged Indigenous men as debauched. Yet while Juana Hurtado had managed, in the first half of the eighteenth century, to ignore Franciscan efforts to control her sexual choices, by the late nineteenth century the force of American military power and the desperate poverty of many Native people made such resistance nearly impossible. To be “assimilated” into the general U.S. population, the Kiowa needed to change their sex lives.34

The Dawes Severalty Act broke apart topadoga and created male-headed, single-family households. Only single men or men who led a marital, single-family household received a land allotment. The Code and Court of Indian Offenses, which was enacted on the Kiowa reservation in 1888, explicitly outlawed polygamy.35

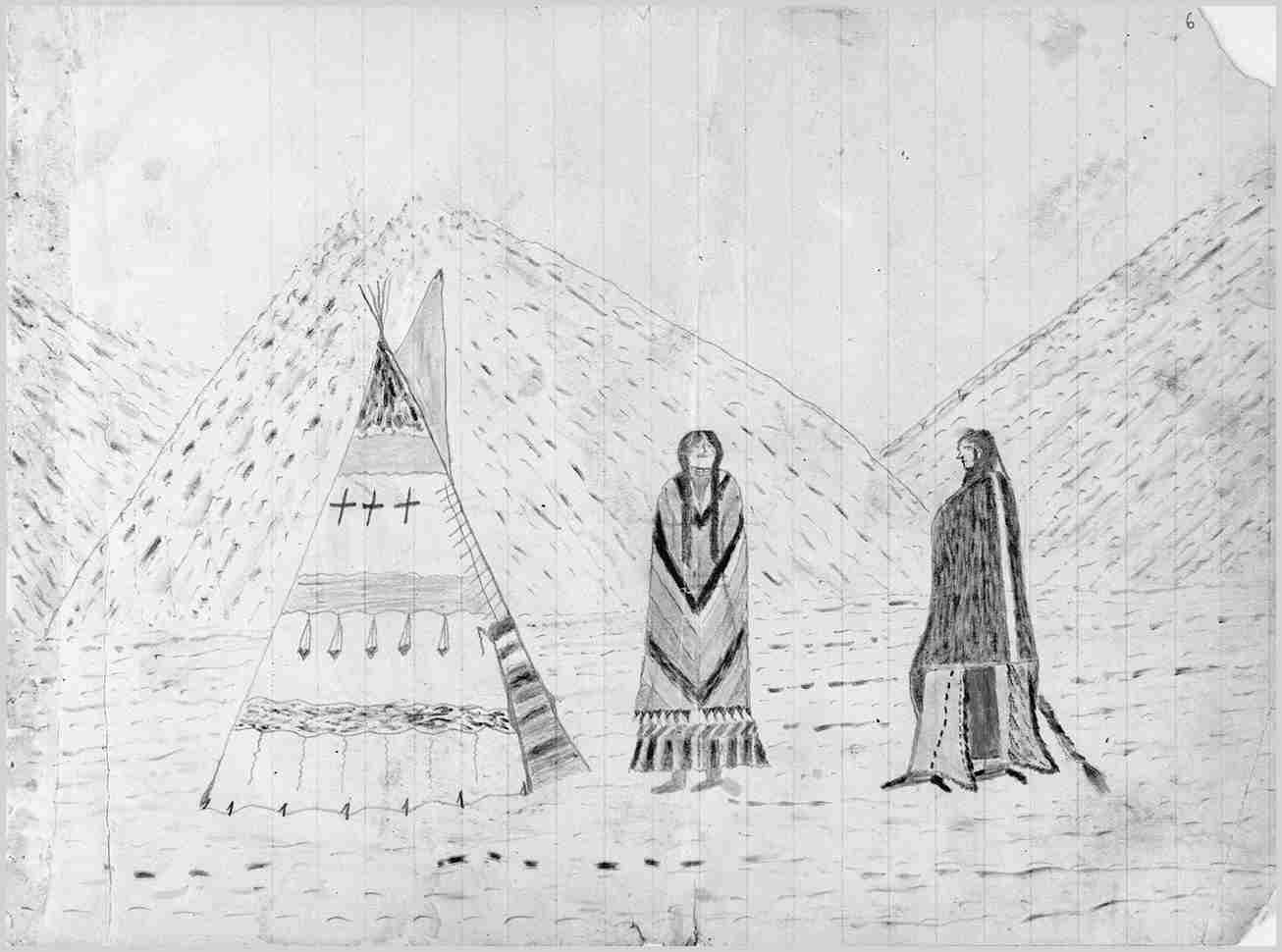

But sexual practices and family forms long valued by Kiowa people did not simply vanish, replaced by parceled lots or federal requirements. During the 1880s, a Kiowa artist drew scenes of their people in a plain ledger book, an item given as a gift by a soldier or missionary, or perhaps stolen, a small response to the theft of land. With colored ink, the Kiowa artist depicted reservation life across the ledger’s pages. In one striking domestic scene, two figures, one male and one female, stand outside a painted tipi. The female figure, positioned near the tipi’s entrance, wears a multicolored blanket, adorned with a chevron of blue, pink, white, and yellow above rows of vibrant patterns. She faces the viewer, while the male figure, more distant from the tipi, looks at her. He is wearing a striking blue blanket or robe above a bright yellow-and-red patterned skirt. Matrifocal households appear to have endured; perhaps the man has arrived to live in the woman’s tipi. The household also appears to be monogamous, as no other women are present to suggest more than one wife. Colored stripes adorn the tipi’s flap, and while three crosses also decorate the tipi, there is little else to suggest Christian ideas dominated the imminent consummation of this conjugal household.36

A Kiowa artist living on the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache (KCA) reservation created this domestic scene, likely between 1880 and 1890, on the pages of a ledger book. It appears to depict a wife welcoming her husband to her home. The U.S. government forced the Kiowa to abandon their long-standing practice of sororal polygamy in order to receive meager but life-sustaining government rations.

Officially, the Latter-day Saints became monogamists in 1896, when church president Wilfred Woodruff banned the practice of polygamy in exchange for an end to what he and his flock saw as federal harassment. Only then did Congress admit Utah as a state. Marital monogamy, as defined by the Protestant men who dominated all aspects of the U.S. government, was the price of citizenship. (The Fundamentalist Latter-day Saints were Mormons who refused to renounce polygamy. They broke away from the main church body and operated in secrecy.)

Yet even as Mormons and Indigenous peoples were being accused of sexual deviance, the values of white Protestant America were changing. Divorce rates climbed steadily upward in the second half of the nineteenth century. Ideas about women’s bodily autonomy animated the pages of sex radical journals—whose readership stretched from New York to Kansas to the Oregon territory—and the socially conservative temperance movement, where women obliquely emphasized the hazards that a drunken husband presented to his wife. Newspaper editors disparaged “free love” and described the scandal of polygamy, but in doing so they circulated images and ideas far beyond the tight-knit communities of Modern Times, Oneida, or Salt Lake City. Theories about the proper aims of sex stirred up heated debates, but all might agree that sex had become a subject of urgent public concern.