Chapter 11

A Society of Queers

Members of the Bohemian Club relished the company of other educated, cultured men. Admission to the secret society, founded in 1872, cemented one’s status as an elite man in late-nineteenth or early-twentieth-century San Francisco.

The Chinese servant at 2525 Baker Street in San Francisco watched a gathering of white gentlemen and their younger companions sip cocktails and wine on an evening in February 1918. Several of the carousing guests wore kimonos. The attire reflected “Japonisme,” an elite, white fascination with Japanese arts and culture. A few of the men had met one another while pausing in front of stores that displayed Japanese art. They might as well have announced to a stranger that they enjoyed the works of Irish playwright Oscar Wilde, another way for a man to signal his interest in queer sex.1

Japonisme was by no means limited to gay men, but it was often seen as feminine and thus, for men, abnormal. In 1914, guests at a men’s party in a Venice Beach home each received a pair of slippers and a kimono upon arrival. Halfway across the country, weekend guests of Robert Allerton, heir to a Chicago stockyard fortune, attended lavish Saturday-night dinners “in costume,” wearing robes and kimonos that Allerton collected during his travels throughout Asia. Of course, not all people enamored of these styles were gay, and not all gay men cared for Chinese or Japanese art. The “Latin” culture of Miami, a city marketed as a tourist destination, drew queer men attracted by a tropical aesthetic. Yet by demonstrating an interest in “the Orient,” a man could indicate that he fit within an emerging understanding of “temperamental” men, who valued art and music, loved one another, and desired the company of other men. They may have agreed with a young man arrested in Long Beach in 1914 who explained that he belonged to a “society of queers,” or a growing community of like-minded people who, among other things, adored the famous female impersonator Julian Eltinge and engaged in what local and state laws defined as deviant sex acts.2

We know very little about the “Chinese servant” who tended to the needs of the men at 2525 Baker Street, compared to what we know about the white men in this “society.” Newspapers did not report his name. He may have been born in the United States and been a citizen, he might have had a white parent, and he might even have been a Japanese or Korean person misidentified in newspaper reports. He listened as the guests discussed plans to attend a party or perhaps stop by the Bohemian Club, an exclusive gathering place for “all gentlemen, and no ladies.” He observed that some men left the first-floor living area for an upstairs bedroom. The gentlemen on Baker Street took little notice of him; they probably presumed, as white Americans often did, that, like most “Orientals,” the Chinese man had more than a passing familiarity with sexual deviance and was paying them no mind.3

Unfortunately for the white men at 2525 Baker Street (and neighboring 2527, where the party continued), the servant was a plant, sent by the San Francisco Police Department’s “morals squad.” He gathered evidence of illegal “vice” at what became known in the press and in court as the Baker Street Club. In 1915, California had become the first state to criminalize fellatio and cunnilingus as felony “sex perversions,” whether involving same-sex or male-female pairings, and it was under that statute that the men were charged in 1918. (Male-female pairs were hardly ever prosecuted under this or similar state statutes that criminalized oral sex.) The accused faced a maximum of fifteen years in prison. The case eventually implicated thirty-one men, including wealthier businessmen, clerks, and members of the U.S. military. After a police court dismissed several of the cases for lack of corroborating evidence, the district attorney called a grand jury to investigate. Four men fled before they could be arraigned; one went as far as Honduras.4

And yet at the end of a three-year ordeal, all the men involved were acquitted, and those who had been imprisoned were released. In a 1919 ruling that delved into the origins and scientific meanings of the word “fellatio,” the California Supreme Court determined that its definition remained unsettled and vague. It was Latin rather than the plain English that the state constitution required of its laws. The justices consulted the works of sexologists Havelock Ellis and Richard von Krafft-Ebing, who described fellatio as a practice involving a man and a woman rather than one between two men. (The California assembly revised the relevant section of the state’s criminal code in 1921 to define “oral copulation” between any two people as a felony.) Newspaper accounts about the Baker Street Club never mentioned the words “homosexuality” or “fellatio,” writing instead about unspecified vice so vulgar that one judge dismissed women from the jury pool because he believed the “revolting character of the testimony” would upset them.5

The story of the kimono-clad white men of the Baker Street Club helps explain the emergence of the very idea of distinct sexual identities in the early twentieth-century United States. Nineteenth-century theories about the sexual “invert,” as we saw in Chapter 8, defined certain men and women as members of a third sex, their masculine and feminine traits an “inversion” of what a “normal” person assigned male or female at birth presumably exhibited. Same-sex-desiring and queer people in the early twentieth-century United States created identities and communities that reflected this attention to gender, but they increasingly emphasized sexual desire as the defining aspect of their difference. They called themselves and one another queers, homosexuals, gay men, lesbians, bulldaggers, lady lovers, fairies, sissies, pansies, and a variety of other terms that emphasized an erotic interest that defied heterosexual norms. Several of these terms, such as “bulldagger” and “fairy,” highlighted gender, and they also referenced differences of class and race.

The police who raided 2525 Baker Street and the judges who heard the resulting cases were often perplexed by what, exactly, had transpired there. But the evidence their intrusions revealed provides us with clues as we try to understand the past. Combined with first-person accounts of queer women’s experiences, particularly Mabel Hampton’s reminiscences of Harlem, the complex and vibrant queer subcultures of the early-twentieth-century United States come into view.

Urban police departments charged with cleaning up their city’s “vice districts” began to search for evidence of “deviant” sexual activity. One arrest might expose an entire network of men seeking and having sex with other men—or, at times, those believed to belong to the “third sex.” Police often targeted public or semi-public spaces, including migrant labor camps and shipping docks. The arrest of nineteen-year-old Benjamin Trout for petty crime in Portland, Oregon, in 1912 led to his disclosure that men purchased queer sexual pleasures in the city’s parks, hotel restrooms, and downtown streets. Trout scratched out a living on the margins of Portland’s economy, part of a transient labor force that extended from Alaska down the Canadian coast to Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and California and that drew wage-seekers from Europe, Mexico, Asia, and other parts of the United States. But many of the men he met for sex were white and middle-class, the kinds of people who were expected to call for “municipal reform” to “clean up” urban vice districts, not seek out sex there. The Portland Vice Scandal ultimately implicated about fifty men on charges ranging from “indecent acts” to sodomy and oral sex. Newspapers printed the accused men’s names and home addresses, shaming them while offering a clear warning to others about the potential consequences of “degenerate practices.” Dozens of suspects initially evaded arrest by fleeing the city until an international manhunt located them and returned them to Portland to stand trial. Several of them lived on the margins of Portland’s economy, picking up work when they could and “tricking” (trading sexual favors for money or goods) when they couldn’t. These men slept outdoors or rented inexpensive rooms. One of the arrested men, mortified that his sex life had been made public, died by suicide at the YMCA.6

These and other police investigations revealed the distinct vocabulary that characterized queer male sexual encounters in American cities and among migrant laborers. Some terms originated in the social world of male sex workers, while others indicated a person’s gender presentation or preferred sex acts. Feminine men who performed oral sex on other men were called fairies in New York but were more derisively described as “cocksuckers” in California. A “pogue” was a man who wanted to be “browned,” or anally penetrated, while “two-way artists” were men who enjoyed both oral and anal sex with men. (The second half of this chapter discusses the experiences of queer women in more detail.)7

Fairies developed their own lexicon: they called the men interested in a longer-term relationship with them “husbands” or “jockers.” Their terminology distinguished normatively masculine men who had relationships with boys and adolescents as “wolves” and the youths they pursued as “punks” or “lambs,” language that compared these sex partners to predators and prey. Yet outside of these specific subcultures, well into the twentieth century, Americans did not group all of the people involved in these sex acts as comparably “queer.” They considered the people who had atypical gender presentations—mannish women and feminine men, like fairies—to be the “perverts.” For a time, at least, the general public did not necessarily associate sexual deviance with normatively gendered women and men who engaged in queer sex.8

When newspapers reported on police raids, they also revealed that men of different classes preferred different forms of sex. In Portland, middle-class white men purchased oral sex from younger, laboring men, some of whom had immigrated from Greece. By contrast, when working-class men in Portland had sex with one another, they typically engaged in anal sex or in “interfemoral” or “thigh” sex, rubbing one person’s penis between another person’s thighs. Sailors were associated with sodomy and oral sex, especially after arrests and convictions brought the prevalence of sailors’ sex with other men to public attention.9

As in other parts of the country, newspapers and attorneys in the Pacific Northwest nevertheless blamed working-class, foreign-born, and transient men for spreading their deviant “habits” to the white middle classes. The allegations did not describe any of these men as “homosexuals” with a particular sexual identity but rather associated sexual deviance with economic precarity, racial difference, and social dislocation. Most of the men arrested in the Portland Vice Scandal were found not guilty for lack of corroborating evidence. Guilty pleas and convictions still sent at least seven of the accused to prison.10

Vice squads exposed all men involved to public humiliation, but in an era rife with anti-immigrant fervor, men considered “foreign” by virtue of their country of origin or their religion (or both) seem to have received harsher sentences when convicted of criminal sexual conduct. Critics warned that sexual deviance was yet one more bad habit that foreigners were introducing into the country. Forty-four percent of the men arrested for queer sex in Portland between 1870 and 1921 were foreign-born, with a comparable percentage of foreign-born men convicted of queer sex in Washington State during that period.11

In California, local law enforcement led the charge against “sodomites” among the “Hindus,” a term they applied to South Asian men regardless of their faith. Transient and otherwise indigent men were especially vulnerable to this intrusive policing; their “vagrancy” affirmed police associations of homosexuality with social outsiders, even as the very facts of their poverty left them with fewer options to have sex privately. One example was the case of Stanley Kurnick and Jamil Singh, both ranch hands in the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys. On February 10, 1918, two police officers patrolling downtown Sacramento observed Kurnick, age nineteen, with the “Hindu” (Singh), who was forty years old, having a conversation on a street corner. Singh offered Kurnick 75 cents to go with him to a boardinghouse. Following a lead from an informant, the police located Kurnick’s room later that night. An officer “looked through the keyhole and saw a boy lying face downward on the bed with his clothes partly off” and the “Hindu” also partially undressed, lying on top of the boy, “going through the motions . . . [of] having sexual intercourse.” Officers broke open the door and arrested both men. Singh was sentenced to seven years in San Quentin, but the judge charged Kurnick, whom he considered “probably of low mentality,” as “an accessory to the carnal act of the Hindu” and sent him to juvenile court, even though Kurnick was not a minor. “Hindus” and “Orientals” were presumed to be sexually immoral threats to white “Americans.”12

Transmasculine people also suffered from the attention of these new vice squads. In 1913, police in Brooklyn arrested Elizabeth Trondle for “masquerading in men’s clothes.” While detained at the Raymond Street Jail, Trondle wrote to President Woodrow Wilson, a letter that newspapers throughout the United States reprinted. “I am a woman in trouble and I want my rights,” Trondle wrote. “I want a permit from you or some one else to wear the costume I have adopted. I am tired of being kicked around and poorly paid.” A judge explained that he sentenced Trondle to three years at the Bedford Hills Reformatory for Women “because I believe she is a moral pervert.” Trondle was not accused of a criminal sex act, but the judge’s words reveal the ways in which unconventional gender was increasingly associated with sexual deviance.13

All signs of gender nonconformity or displays of queer desire increased the risk of arrest for “lewd acts.” New immigration policies were predicated on the idea that queerness was a visible trait, discernible from one’s clothing, affect, and speech. At Ellis Island, immigration inspectors turned to psychiatrists working for the Public Health Service when they suspected that a prospective immigrant might be a degenerate. The psychiatrists were confident that they could see evidence of degeneracy on the person’s body, conflating smaller-than-average male genitals or intersex bodies with perversion. Immigration officers believed that perverts would invariably lead a life of dissipation and crime, and that effeminate men were “prone to be moral perverts.” They concluded that all such people were likely to become “public charges” (to depend on public welfare) and were thus ineligible for legal residency.14

An older man’s affectionate interest in a younger man had occasioned little concern in decades past. Groups such as the YMCA and church ministries were premised on the idea that adult men formed close bonds with male youth to guide their personal development. The new visibility of “queer” communities, coupled with actual evidence from widely reported police raids that YMCAs could be sites of sex between men, cast those relationships in a different light. By the 1920s, tenderness toward a younger man or interest in the arts might each render a man vulnerable to suspicions of queerness.15

A new concept of sexual identity was gradually reshaping American life in the 1910s and 1920s. White, middle-class men who desired sex with men began to call themselves “queers,” a term that they understood to designate their sexual interests but not their gender identity; a queer man might be primarily masculine or feminine. Queers differentiated themselves from “fairies,” who were more often younger and less financially secure, and who were more likely to teasingly call one another by conventionally female names and assume a conventionally female affect. Fairies and queers generally celebrated the arts, paid attention to fashion, and valued refined manners. Some queer men tried on fairy effeminacy as part of their discovery of their sexuality, while others expressed anger at fairies for drawing attention to the desires that increasingly put them at risk of arrest or social ostracism. Queer men were more often able to pass for straight in their working lives (or in their marriages to women), leaving fairies to remain the most visible representatives of sexual nonconformity.16

Some queer women also began to understand themselves as a group apart. Middle-class and elite white women were the first to adopt a self-conscious identity as “queer” or “gay” women. Few used the word “lesbian” until the 1930s. (One study found that “lesbian” became a more common term of self-identification in San Francisco only in the 1960s.)17

But by the 1910s, groups of women began to recognize one another as members of a group defined by desire. Unlike the invert, whose sexual interest in women was explained by her masculinity, no particular gender presentation determined whether a woman was gay. In Chicago and New York, gay women lived in affordable rooming houses and studio apartments in lower-income neighborhoods, as well as in areas such as Greenwich Village in New York that were known for their sexual permissiveness.18

Lesbian identity was less appealing for Margaret Chung (1889–1959), the first American-born woman of Chinese descent to become a physician. Chung had intense romantic affairs with white writer Elsa Gidlow in the 1920s and with the white, Jewish actress Sophie Tucker in the 1940s. When Chung and Gidlow met in 1926, Chung wore “a dark tailored suit with felt hat and flat-heeled shoes,” attire that helped her blend in with her overwhelmingly male colleagues but that she also enjoyed; she completed the look by carrying a “short sport cane.” Gidlow, who was new to San Francisco, believed that she had found a “sister-lesbian” who was even more alluring because of “the ambiguity of this blend in her of East and West.” She pursued Chung, bringing her flowers and poems, and they kissed and expressed their love for each other. Orientalist stereotypes infused Gidlow’s attraction to Chung.19

Associations between gender nonconformity and queerness also transformed popular entertainments in the early twentieth century. In the mid-1920s, a “pansy and lesbian craze” attracted straight “slummers” to overtly queer performances in cabarets, tearooms, and speakeasies. Chicago’s Dill Pickle Club hosted lectures by a “guy named Theda Bara talking about his life as a homosexual” and a woman who presented a “paper from Lesbos” about the possibilities for women’s domination over men. After Prohibition bankrupted many reputable restaurants, after-theater dinner clubs stocked with smuggled booze and operated by organized crime syndicates lit up Times Square in New York City and Chicago’s Near North Side. Speakeasies featured female stripteases and queer lounge acts. Some slummers may have visited these venues as part of their own process of self-discovery: two young women spent the evening at a Chicago speakeasy popular with lesbians after one of them read The Well of Loneliness (1928), British author Radclyffe Hall’s novel about a child named Stephen, assigned female at birth, who self-identifies as a masculine “invert” and falls in love with their neighbor’s wife. By 1930, part of the point of going to see a female or male impersonator in one of the more mainstream theaters in Times Square, for instance, was to demonstrate a sophisticated appreciation for “queer” performances.20

These urban explorers observed a queer world amid transformation. Like the fairy, the pansy was a male-bodied person who exhibited feminine manners and interests, and both words were initially pejorative. But while a fairy was understood to be a feminine man who took the receptive role in sex, the pansy was a bit different: an atypically gendered man who, more importantly, had sex with other men. Small nuances in the meanings of these two words reveal a shift in how queer people were perceiving themselves and being described by others. It was the pansy’s sexual desire for men, more than his feminine attributes, that defined him. The lesbian similarly emerged as a woman whose most salient character trait was her sexual interest in women.21

The idea that “normal” men were masculine and desired sex only with women (and vice versa) was a response to this understanding of queerness. “Heterosexual,” a term coined in the 1860s by sexologists, still required a definition when it appeared in advice columns in the 1920s. It was a concept that came into focus for many Americans as they began to recognize pansies and lesbians as representatives of a seemingly opposite sexual type. Popular psychologists and advice columnists offered instruction about how to help children develop a “normal, heterosexual” disposition.22

The categories of homosexual and heterosexual represented a novel way of grouping people according to the sex of a person’s object of desire. It was a binary that foreclosed older terms that had recognized gender-fluid and queer desires. Fairies and “mannish” lesbians bore the weight of intensifying American homophobia, their proudly public displays of alternative gender identity a visible marker of what was increasingly understood to be an intrinsic, fundamental difference.

Mabel Hampton, a Black Winston-Salem native, moved to West Twenty-Second Street in New York City in 1920, when she was in her late teens. The possibilities at first seemed limitless. An unprecedented number of single women lived apart from their parents in the early twentieth century. They moved to the furnished-room districts in Chicago and New York City or piled into shared apartments, as Hampton did. The privacy of these spaces provided young people with opportunities to socialize, have sex, and live independently. Factory and store owners paid women about half as much as they paid men; Hampton eked out a living in domestic service and as an occasional cabaret dancer. She already knew that she desired women—that she was a lady lover, as the Black press referred to women who were intimate with other women. By accident or design, her next-door neighbor was a lady lover, too, who threw parties in her four-room basement apartment.23

Hampton created a life for herself centered around Black women, their white friends, and the pleasures they made for themselves. Openly lesbian and gay characters appeared in theatrical productions and films in the 1920s (although voluntary “codes” imposed in the 1930s curtailed the representation of queer characters in film). Hampton went again and again to see the 1920s play The Captive, entranced and thrilled by its portrayal of two women in love. She attended drag balls in Harlem, perhaps the annual event at the Hamilton Lodge that drew about 1,500 spectators. Many of these balls included a “parade of fairies,” a procession of transwomen and drag queens who competed for the most outrageous costume. Hampton saw fairies perform campy parodies of feminine behavior on and off Broadway. Vaudeville star Mae West staged a play called, simply, Sex, set in a Canadian brothel, about a sex worker, her pimp, and her sailor-client. The show opened in the spring of 1926 in New York City and ran until a police raid led to the arrests of twenty cast members in February 1927. West served a ten-day sentence at the Women’s Workhouse on Welfare Island, but she was undeterred: her next theatrical undertaking was a play called Drag. Everywhere, the sexual innuendo Comstock had tried to eliminate from the public square now played across screens and stages.24

Hampton and her friends could not afford to go to most of the clubs that white men and women frequented. Nor would many of these clubs have admitted them even if they could have afforded the prices: the only Black people permitted in the Cotton Club and other popular venues were employees or were light-skinned enough to “pass” for white. Hampton and her friends gathered instead in one another’s apartments. Sometimes these were “rent parties,” where the hosts accepted a small amount of cash from each guest to raise money toward what they owed their landlord, as well as the cost of food and drink. (Residential segregation in American cities, including New York, pushed Black people into overcrowded tenements with high rents, usually collected by white landlords.) At parties that doubled as a form of mutual aid, Hampton and her friends danced the Charleston and “did a little bit of everything.” Hampton learned the rules of sexual exclusivity as she sought dance partners and lovers. “The bulldykers used to come and bring their women with them, you know. And you wasn’t supposed to jive with them, you know. You wasn’t supposed to look over there at all. They danced up a breeze.”25

One lover took Hampton to an apartment owned by A’Lelia Walker, one of the wealthiest Black women in the United States. A’Lelia’s mother was Madam C. J. Walker, whose line of hair straighteners and face creams had made her the first Black female millionaire in the country. A celebrated hostess of Harlem Renaissance salons for queer writers and artists, A’Lelia Walker also threw sex parties that encouraged exploration. Hampton recalled a party at which all of the guests were naked. A’Lelia Walker had three marriages with men, and she may have also had an intimate relationship with her secretary, Mayme White, who lived with her for the last five years of her life. (A’Lelia Walker died in 1931 at the age of forty-six.)26

Hampton also attended gatherings known as “buffet flats,” where illegal liquor, sex for hire, gambling, and dancing offered a “buffet” of options for the sexually curious. These hedonistic parties drew the attention of the “Committee of Fourteen,” an influential citizens’ association in New York City. Raymond Clymes, the only Black investigator on the Committee of Fourteen, located sixty-one apartments functioning as buffet flats in 1928. Clymes shared his findings with police. His 1929 report about the cabarets, speakeasies, and buffet flats he visited may have led to an uptick in arrests of Black women in Harlem for prostitution that year.27

The audacious gender nonconformity and sexual assertiveness of Black blues singers captivated Hampton. Song lyrics teased “sissy” men and masculine women. Some Blues songs warned that a “natural” man who failed to satisfy his woman would lose her to the more gratifying charms of a mannish lesbian or “bulldagger.” Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, the “Mother of the Blues,” teasingly hinted at her desire for women in her song lyrics (especially in her 1928 hit, “Prove It on Me Blues”), and she privately dated women throughout her two marriages to men. Ethel Waters, the star of Black Swan Records, the first Black recording label, lived in Harlem with her girlfriend Ethel Williams, where they were known to entertain other same-sex couples. Williams toured with Waters as one of her dancers, but Black Swan’s promotional materials portrayed Waters as a single woman too busy with her career to search for a husband. Bessie Smith, the “Empress of the Blues,” had numerous affairs with women in her touring company.28

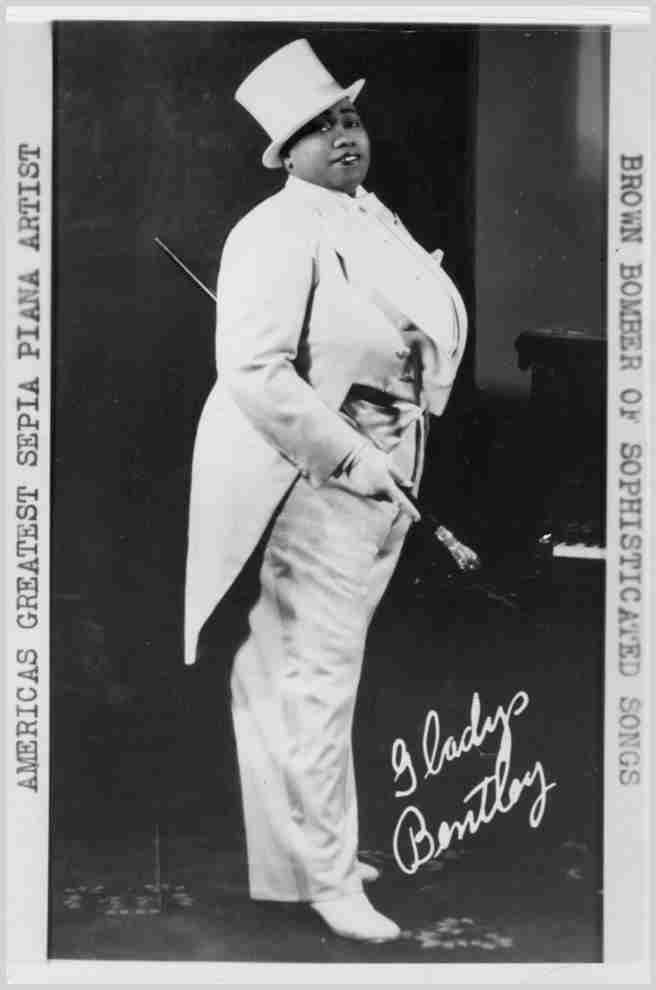

One of Hampton’s older companions introduced her to the famous singer Gladys Bentley, who performed in a tuxedo and flirted with women in the audience. Hampton admired Bentley and other masculine-presenting “butch” Black women who wore trousers not only onstage but in the streets. Hampton “dressed nicely” in trousers, a tie, and a Panama hat and wore her hair short. Later in life, she referred to herself as a “stud,” an affectionate term for masculine-presenting women after World War II, at a time when “butch” and “femme” became the identifiers of choice among many working-class lesbians.29

Gladys Bentley (1907–1960) performed blues songs in a top hat and tails and flirted with women in the audience. Known as a “lady lover” in the Black community, Bentley was an inspiration to Mabel Hampton and other Black women who adopted a more masculine self-presentation.

An arrest in 1924 interrupted Hampton’s enjoyment of those pleasures. She insisted at the time and afterward that the situation had been a setup. She and a female friend, she claimed, were chatting in an apartment while they waited for their male dates to take them to a cabaret. No sooner did the men arrive than two white police officers loomed in the doorway and announced that they were raiding the home on suspicion of prostitution. “I couldn’t figure it out,” Hampton later said. “I didn’t have time to get clothes or nothing.” Hampton was attracted only to women, but she stuck to her story. A year later, when attempting to negotiate parole, she told prison officials that the date she had been waiting for on the night of her arrest was someone she had been seeing for a month and that he had marriage on his mind.30

That may have been true. Or maybe she was helping her friend use the house for the “purposes of prostitution.” She herself was possibly involved in an exchange of sex for cash. The refusals of landlords to lease decent properties to Black people forced many Southern migrants to live in urban neighborhoods that were also home to gambling dens and brothels. White entrepreneurs moved their “vice resorts” to these neighborhoods, confident that law enforcement would not follow them there. But once police officers understood certain neighborhoods to be “vice districts,” they started arresting Black teens and women for solicitation on flimsy premises, such as observing the teen or woman walking down a city street alone or entering a building with a man. In Hampton’s case, she might have engaged in occasional sex work, participating in an underground economy to supplement the meager wages that a working-class woman could otherwise earn. Whatever the reason for Hampton’s presence in the apartment that evening, she was charged with being an accessory to sexual solicitation. The court gave Hampton the same sentence Trondle had received: three years at the Bedford Hills Reformatory for Women.31

Hampton stayed in one of two cottages at Bedford designated for Black women. The prison had formally instituted racial segregation in 1917 after a State Board of Charities investigative committee discovered “harmful intimacy” between Black and white female prisoners. The study was but one of several reports about interracial sex in women’s reformatories and prisons during the 1910s. White social scientists portrayed Black women as the masculine aggressors in these relationships, with white women as the passive, feminine objects of their attention. These stereotypes characterized Black women as unfeminine, primitive, and dangerously seductive, yet another example of the long and terrible history of stigmatizing Black women as undeserving of respect.32

At Bedford, Hampton found comfort in the beds of Black women. “It was summertime,” she later recalled about one fellow inmate, “and we went back out there and sat down. She says ‘I like you.’ ‘I like you too.’ . . . We went to bed and she took me in her arms and I went to sleep.” Hampton was released on parole after thirteen months, on the condition that she live with her aunt in New Jersey and stay away from New York City. Such arrangements were common in delinquency cases, which approached rehabilitation as a project requiring family support and gainful employment. Hampton’s aunt complained to the parole board that her niece continued to attend parties in the city. Unable to tolerate her aunt’s criticisms and unwilling to stop enjoying nights out on the town, Hampton voluntarily served out the final five months of her sentence at Bedford.33

Mabel Hampton may have lied about her “date” on the night of her arrest, but among friends and neighbors, her identity as a lady lover was well known. She and her friends understood themselves as part of a community defined by their own understandings of queer desire. They accepted gender nonconformity, shared experiences of same-sex attraction, and pursued pleasure—sexual and otherwise—as an expression of their inner selves.

Hundreds of speakeasies and illicit entertainment venues flourished in New York City throughout the 1920s. Civic reformers soon blamed queer performers and clubs for much of the city’s sexualized culture. A pushback against the pansy craze in New York began in 1931, as police shut down Times Square venues that featured female impersonators or drag balls, which they blamed for crime and “disorderly” conduct. Police raided even more clubs with queer acts and patrons following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. The State Liquor Authority (SLA) in New York, one of many new state-level liquor-control boards across the United States, authorized its agents to revoke the liquor license of any “disorderly” establishment. The mere presence of gender-nonconforming people, sex workers, lesbians, gay men, or gambling was enough to force a bar to close. Between the 1930s and 1950s, the SLA shut down hundreds of New York City bars that welcomed (or simply ignored the presence of) gay and lesbian patrons. In Chicago, a mayor cracked down on female impersonators and striptease acts as he ran for reelection in 1934. As the relative openness of queer nightlife in New York and other northern cities declined in the 1930s, new leisure markets expanded in places farther south and west, where visible queer cultures flourished.34

In San Francisco and Miami, the repeal of Prohibition created conditions ripe for the expansion of bars that accepted queer patrons and for nightclubs that featured queer acts. The cities’ economies depended on tourism, and each had a reputation for being a “wide-open town,” where anything was possible. (Miami also competed for tourists with Caribbean cities, especially Havana, that had vibrant nightlife scenes.) One important shift in San Francisco was the end of organized crime’s control of the city’s clubs and bars after repeal. Gender-transgressive nightclubs like Mona’s and Finocchio’s opened near the central theater district. Police in San Francisco could still harass gay and lesbian patrons and bar owners, but there was no analogue there to the powerful SLA in New York. Rather than a liquor-control board, California established a fiscal agency that could accept fees for liquor licenses but had no enforcement powers to take away licenses from “disorderly” establishments.35

Hampton and other queer Black people, meanwhile, confronted overt hostility from Black leaders. Adam Clayton Powell Sr., the pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem and one of the most influential Black men of his day, preached in 1929 that “Homo-sexuality and sex perversion among women” had become “one of the most horrible, debasing, alarming and damning vices of present day civilization.” Worse, he continued, it spread by “contract and association” and “is increasing day by day.” Powell concluded that a decline in sexual morality was decimating the Black population. In the mid-1920s, Marcus Garvey, a dynamic Jamaican immigrant who led the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), condemned both birth control and same-sex sexuality as forms of genocide. Powell’s and Garvey’s condemnation of homosexuality added a new layer to middle-class Black warnings about the effects of undisciplined sexual behaviors on the survival of the Black population.36

By the mid-1930s, queer people relied upon longstanding strategies to hide their desires from the broader public. In a scene reminiscent of Alice Mitchell’s plans with Freda Ward, two Black women in New York City got married in 1938 when one of them put on trousers so that they could pass as straight at City Hall, filling out forms and getting their premarital blood test without anyone the wiser. The officiating minister was the only man present at a private ceremony at the couple’s home. And while he asked the partners to state whether they “took this woman” and “took this man” to be their lawfully wedded wife and husband, he knew that two women kissed when he proclaimed that it was time to “kiss the bride.” Hampton, who attended the wedding, presumed that the minister was gay as well. In her reminiscences about the wedding, Hampton recalled a ceremony between lesbians, and it’s very possible that the marriage partners also understood themselves that way. It is equally possible that the partner dressed as a groom was what eighteenth- and nineteenth-century people called a female husband or what we more recently describe as a transman.37

Hampton’s own domestic life changed after she received a flyer from a Black woman named Lillian Foster in 1932. It announced Foster’s upcoming rent party, “A Sunday Matinee given by Lillian,” at her apartment on West 130th Street. The flyer promised: “Hard times are here, but not [to] stay. So come, sing and dance your blues away.” Hampton went, entranced by Foster, who “always looked like a fashion plate.” She stayed for the next forty-six years, until Foster’s death in 1978 parted them.

Mabel Hampton’s defiant assertion of sexual selfhood illuminates Black women’s contributions to “modern” sexuality, a sense that sexual desire constitutes an essential part of one’s being, and that seeking sexual pleasure is necessary for one’s full humanity. Like the white men of the Baker Street Club, she belonged to a community centered on queer desire and accepting of gender nonconformity. These early decades of the twentieth century enabled queer communities to cohere in many American cities, even as police began to target homosexuality as a perverse source of urban vice. But Hampton described same-sex love and erotic expression in ecstatic terms. “Joan,” she told her friend Joan Nestle years later, “there are some women I can’t touch because the desire burns my hand like a blue flame, those women, those women!”38

Mabel Hampton (1902–1989) moved to New York in 1920 when she was seventeen years old, finding a home among other “lady lovers,” first in Greenwich Village and later in Harlem. A flyer advertising a rent party in the home of Lillian Foster in 1932 changed Hampton’s life. They were lovers and partners until Lillian Foster’s death in 1978. In this undated photo, Lillian Foster drapes her arm over Mabel Hampton’s shoulder.