Chapter 13 Scientists and Technologists

Knowledge is power.

–– Lord Francis Bacon.1

Bacon was right. But power to do what? If a young scientist wanted to produce a happier world, what topic would she choose to research?

Clean energy

My number one topic would be clean energy. In 2012, I was sitting on a plane next to the former British Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell and the conversation turned to climate change. Since this is the most urgent problem facing humankind, I asked Gus why there was so little research on cheap clean energy. After all, scientists faced with the Nazi threat had produced the atom bomb within five years. And, faced with the Soviet challenge, they had put a man on the moon in less than ten. If scientists can do these things so quickly, they can surely find ways to produce clean energy that is cheaper than energy from coal, gas and oil.

That is the key to counteracting climate change. Once clean energy becomes cheaper to produce than dirty energy, the coal, oil and gas will simply stay in the ground. International agreements are important for resetting priorities – and regulations, taxes and subsidies help a lot. But the ultimate solution to climate change will be the science of how to produce, store and distribute cheap clean energy.2

So what are the scientists up to? Incredibly, until recently only 4 per cent of publicly funded research in the world has been on clean energy.3 That is all that our governments have been spending on the greatest material problem facing mankind. But, you might say, the private sector can solve this problem – didn’t they invent the iPhone? Well, actually, no they didn’t. Most of the components of the iPhone were invented through publicly funded research,4 as were most of the main technological advances of the last hundred years: the computer, semi-conductors, the internet, broadband, satellite communications, genetic sequencing and nuclear power. With clean energy research, as with these other discoveries, the uncertainty and risk is so great that the private sector cannot fund much of the basic work. It needs public money to get many more brilliant scientists to work on these problems.

So, in response to my question, Gus O’Donnell suggested asking David King, who as it happened was going to the same conference as us. David King was the British government’s Chief Scientific Adviser under Tony Blair. He, more than almost anyone, was responsible for Britain’s pioneering Climate Change Act of 2008, which committed the country by law to progressive reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.5 In answer to our question, David replied that there was no good reason (except political will) why the world should not double its public spending on clean energy research in a very short time.

Thus was born what became Mission Innovation, a global commitment in 2015 by the twenty leading countries to double their clean energy research in a coordinated way by 2020. We launched the proposal in 2015, calling it the Global Apollo Programme, to highlight the parallel with the original Apollo moon landing.6 We also invited the great naturalist David Attenborough to speak at the launch of our proposal. By sheer chance he had been asked a few days earlier to meet with President Obama. Over tea with the President he had commended the proposal, and the President soon gave his support, together with nineteen other leading countries including India and China. It was called Mission Innovation and Bill Gates and other business people also promised $1 billion of private money to follow through on implementing the discoveries made by the programme.

The programme is already well under way.7 Soon its member countries will be spending $25 billion annually on clean energy research. That is really big money – comparable to what was spent on the original Apollo programme. So now at last we have the money to inspire and energize a whole generation of scientists to work on one of the world’s key problems.

The challenge is fascinating and the opportunities immense. For example, the sun provides the earth with 5,000 times more energy than we need. Photovoltaic panels can trap the energy, even when the sun is not shining. The cost of these panels is tumbling, in the same way that the price of computer chips has been falling. Further breakthroughs are also possible using new materials. But then the energy has to be stored for the night-time and for the winter, and a whole range of new storage methods need to be tested. Finally, a new generation of smart grids is needed, as well as electric vehicles and better carbon-free ways of heating and cooling our buildings.

This work is central to the happiness of future generations. If we allow the temperature of the world to reach 2 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level, it is likely to stay at that level – or above – for a century or more, because that is how long greenhouse gases stay in the atmosphere.8 If this happens, there will be major increases in the number of droughts, floods and tempests, leading to mass migration from the worst-affected areas and, inevitably, conflict. Eventually, if that temperature continues long enough, the Greenland ice cap will melt and sea levels will rise by some 7 metres.9 The climate of the planet, which has been stable since the Stone Age, will be altered – precipitating changes in our living conditions which are very difficult to forecast.

In the face of uncertainty, what do people usually do? They insure themselves. That is the case for action to preserve our current climate. And it is why scientists concerned with human betterment should be flooding into clean energy research.

But sceptics argue that the consequences of climate change are far into the future, and in economic analysis we apply a heavy discount rate to future changes. That may be reasonable if we are talking about future changes in income.10 For future generations will be richer than we are, and so a loss of income to them will matter less for their happiness than an equal loss of income for us. But when it comes to happiness itself, things are different. Future happiness matters no less than present happiness.11 And happiness is influenced by much more than income. For example, happiness requires peace and security;12 and in many areas of the world climate change will imperil both.

The Paris agreement of 2015 went a small way to improve things. But the central forecast is still that the temperature will be an extra 2 degrees higher between 2060 and 2070,13 and an extra 3 degrees by 2100.14 So scientists of the world, unite. We need you to save the situation, and to preserve life on earth as we know it.

Science and human need

What else should scientists be working on? And who should decide this? In Britain the decision is made by the scientists and researchers themselves (the so-called Haldane principle). In consequence, decisions about spending resources are mainly driven by curiosity about how life and the universe work. That is a good approach because science so often produces benefits undreamed of by the discoverer. Newton would never have guessed that his principles would produce satellite communications. Like every scientist he was driven by the urge to understand the world.

Even so, it is worth asking how a young scientist wishing to improve human happiness would choose which problems to focus on. In the case of social science the answer is easy. Social science should focus on what causes happiness and misery – both directly and indirectly (through wars, dictatorships and the like). In particular, we now need thousands of controlled experiments (like the few we have described in this book) to discover the most cost-effective ways to improve people’s happiness.

When it comes to natural science, I am not qualified to make detailed suggestions. However, one obvious approach is to ask, ‘What are the biggest causes of existing human suffering?’ As we have seen, these include:

- pain (physical and mental) and premature death

- poor quality of work.

These are worthy subjects for science in the twenty-first century.

Pain and death

The most obvious triumphs of humanity in recent centuries have been the reduction of physical pain and the extension of human life. Over the twentieth century, average life expectancy in the world rose from forty to seventy years. Most infectious diseases were either eliminated (like smallpox) or dramatically reduced in scale. In rich countries today most people in severe pain (or undergoing surgery) are now treated with painkillers; others buy them at the chemist. It has also become possible to reduce much mental pain with medication or psychological therapy.

Nevertheless, suffering on a large scale continues. Some of this is because of lack of money: we simply do not apply known remedies. But much of it is because we do not know what to do. We have no total cures for most non-communicable diseases (including asthma, arthritis, diabetes, most cancers and many heart conditions). All we have are treatments which ameliorate the conditions. The same is true of schizophrenia, personality disorder, substance abuse, bipolar disorder and many forms of depression. Tackling these problems is a top priority for natural science and, to my mind, more important than improving the productivity of the economy. In fact in the twenty-first century the most valuable aspects of economic growth will be what happens inside our bodies and minds, rather than outside us.

We can only guess at what these advances will be. Our bodies are likely to become full of gadgets (or linked up to them) to make us feel better and live longer.15 They will also contain replacement parts for different organs. But, more important, we must hope for better ways of treating mental illness – both new psychological treatments and better medication to relieve mental (and physical) pain.16 Ultimately the body and mind are one; we can help the body by treating the mind, and we can help the mind by treating the body.

Does all this mean that we will become less human? On the contrary, we will be more like we want to be. Most people on antidepressants report that they are now more like their ‘real selves’, not less so.17

But we cannot avoid two big problems resulting from our success. The first is the suffering caused by our enhanced ability to preserve life, but at very low quality. If people in terrible pain want to die, they should be allowed to undertake an assisted suicide, subject to strict legal safeguards – as we argued in Chapter 8. Equally, if parents want to preserve a severely premature baby for a life of unbearable suffering, doctors need the right to say No, on behalf of the child.18 The second problem is the pressure on medicine to enhance our capacities positively, as well as to reduce our suffering. We reject doping in sport. But should we also reject cognitive enhancers or aids to physical activity or positive living? If there are no bad side-effects, I cannot see why we should object to any of this.

A more extreme question is this. Suppose we could use DNA to predict a person’s probability of happiness, which we can already do with some degree of accuracy.19 Should we allow doctors to offer in vitro fertilization for, say, four eggs and then choose the best embryo (with, for example, the DNA predisposed for the greatest happiness)? I suspect that eventually it will happen.20 The most obvious danger is that parents will select on grounds of sex, producing an imbalance of sexes in the population.

Artificial intelligence and robots

What about work? As we have seen, most people enjoy their job less than they enjoy most other things, including housework. This is a disturbing fact about rich countries. Equally, in poor countries many people undertake back-breaking toil, in which their feelings are numbed by exhaustion for much of the time. So should we welcome AI and robots?

Artificial intelligence will certainly displace some mental activities that are quite interesting: for example, much medical diagnosis. But robots will mainly replace drudgery – routine activities, physical or mental. As we argued in Chapter 11, this will not cause an upward trend in unemployment. It will of course cause massive changes in the structure of employment. But this is what has happened throughout modern history: looms replaced weavers; tractors and cars replaced horsemen; washing machines replaced laundrywomen; and so on. Yet no upward trend in unemployment resulted. The changes were hard on those affected, and many of them had long spells out of work. But, despite massive population increases over two centuries, the unemployment rate has not risen. This is because the labour market operates like other markets, and (apart from structural impediments) the workers seeking work get hired – at some wage or other.21 The main issue for the future is at what wage. Clearly, AI and robotics will increase the demand for technologists, whose real wages will rise. And they will reduce the demand for less skilled people, whose real wages will fall, unless their supply falls even faster. These trends make better education for the less able students even more crucial.

What about hours of work? AI and robotization are likely to raise the average wage. In consequence we can expect average hours of work to fall, as people choose more leisure. But how will they spend their leisure time? They will enjoy it a lot more if they have had a broad education, which includes music, dance, drama and art. In the age of robotics, there is no case for a productivity-above-all-things system of education. As people become less preoccupied with money, they will only be happy when they find other purposes in life – either social or aesthetic.

Social media and data

Not all technology is unambiguously good and this applies particularly to social media. Here the positive potential is clear, but there are also many elements of danger:

- the polarization of opinion and the spreading of misinformation, often anonymously

- the transmission of hate speech and cyber-bullying, often anonymous

- the generation of anxiety and depression

- the invasion of privacy.

I will concentrate here on the last two dangers.

Platforms like Facebook and Instagram have become central to the lives of billions. They appeal to something basic in every human – the wish to be informed, to know what’s going on, to be connected and to communicate. They have many advantages. But there are also some huge problems.

The first is the usual problem of comparisons. The more you know about other people, the more you can compare them with yourself. This is made worse by some extraordinary forms of measurement – the number of friends or followers and the number of ‘Likes’.

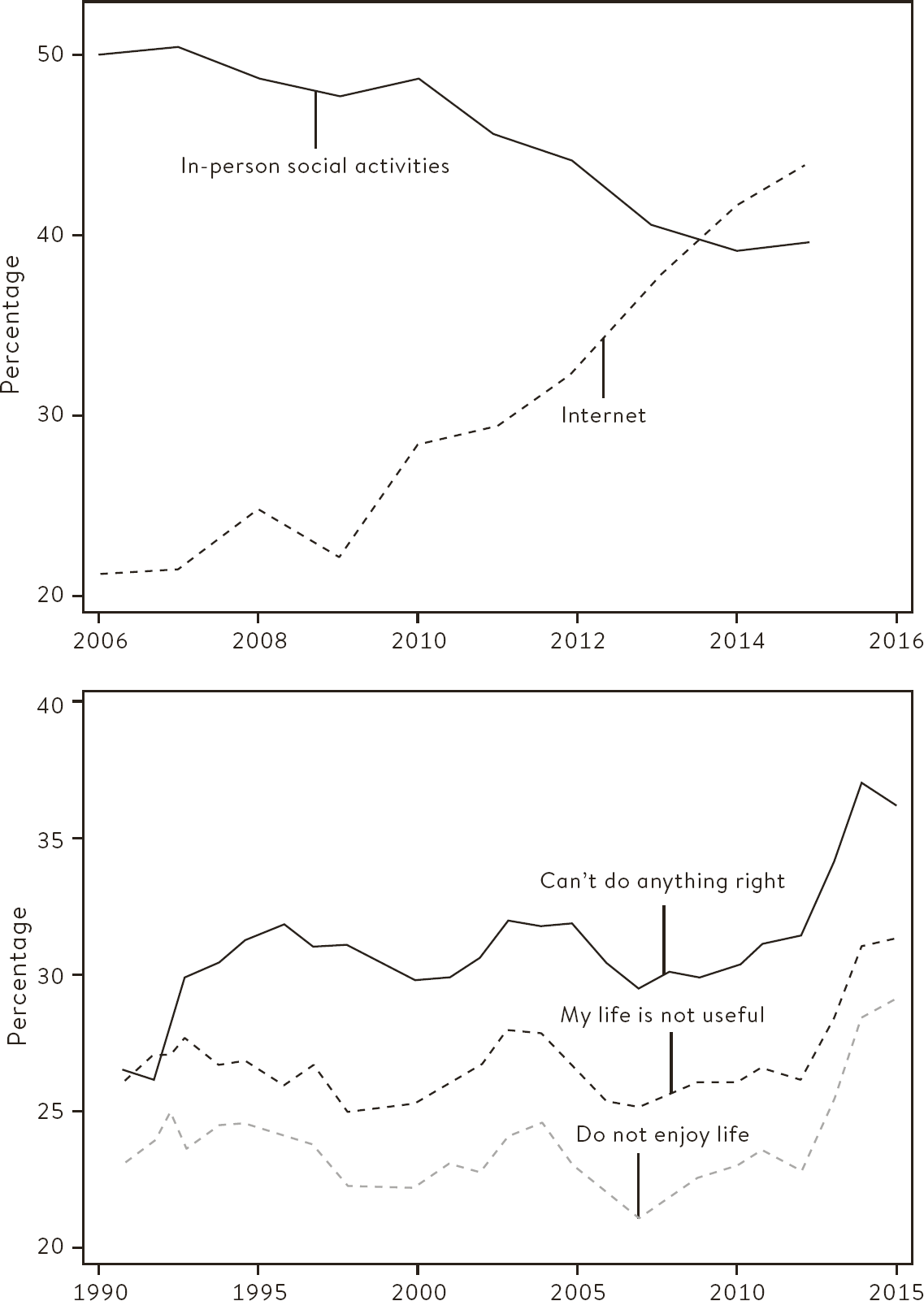

The consequences for adolescents do seem to be quite serious. In a remarkable book, Jean Twenge has produced dozens of diagrams which tell a similar story. As the top graph in Figure 13.1 shows, time online took off from 2010 onwards, mainly due to increased use of Facebook.22 This led to an inevitable decline in face-to-face activities. But more important were the consequences for mental health. As the lower graph shows, there was a sharp increase in the number of young people who stopped enjoying life. Also (not shown) many more of them felt ‘left out’ and ‘lonely’.

Of course, correlation does not prove causation. But, in an ingenious randomized experiment, one group of 516 Danish adults were asked to stop using Facebook for a week, which they largely did. At the end of the week, when compared with the control group, their average life-satisfaction had increased by 0.4 points (out of 10). This is a lot. Some 9 per cent fewer of them were lonely, and some 11 per cent fewer of them were depressed.23 And in two other studies people were followed over time. After using Facebook they became less happy, and after socializing face to face they became happier.24

(top) Percentage of eighteen-year-olds spending ten or more hours per week online and percentage undertaking four face-to-face social activities (bottom) Percentage of thirteen-to eighteen-year-olds experiencing negative thoughts in last twelve months

What an ironic outcome. The medium which aims to put people in touch with each other has led, instead, to more people feeling left out. Instead of living their own lives, many people have become obsessed with the lives of others – and how those lives compare with their own.

For this reason they also have to take great care how they present themselves. Instead of just seeing things and enjoying them, they have to post pictures of them. In many cases this is a generous deed, but in other cases it is a form of self-advertisement. Whereas earlier generations were urged not to show off, social media now invites people to do just that. The result is both anxiety for the show-off and deflation for everyone else.

Young women suffer worst because they use social media more than men. Moreover, aggression by males is typically more physical in nature and can be avoided for much of the day, while aggression by females tends to be more verbal and, if online, it’s with the recipient 24/7.25 So what is the solution? Social media will require major regulation, like most other aspects of life. All new technologies eventually get regulated. In 1930 the car (a new-fangled device) killed 7,300 people in Britain. By 2016 this number had been reduced to 1,700, largely by regulation. Regulation must be a part of the response to the internet.26 But individuals also have to learn how to use the new technology better.27

A second major danger associated with social media is the power that it gives to those who control these platforms. This power comes from the direct access that they have to us and the knowledge they have about us. They earn their income through giving advertisers access to us and through selling data about us to banks, retailers, researchers and many others. The same is true of Google and smart phone suppliers. This use of data requires strict regulation.

One final reflection. We live in a society that is driven more and more by data. This helps us to understand the world better and to be more efficient. Science is based on data, and more and bigger data means better science. Moreover, to manage anything we need data – to know what we are achieving. We need data to manage a business and to manage a heart condition.

But, in the end, a body is more than a system of equations and so is a business. In the end, these are lived experiences. To get people to take happiness seriously, we measure it. But the measurement is only a proxy for the reality – for the subjective feeling of being alive. Measurement has an honoured place, but we are lost if it takes away the fun of life – and the magic.

Conclusions

Technology moves fast, and in 1940 no one foresaw the rise of the internet. So we can hardly guess at the technology which children born today will experience by the end of the century. But we know one thing. Basic human nature does not change. We have the same core needs as our Stone Age ancestors. We want food, shelter and physical safety. We want to be healthy and to live long. We want to love and be loved, to be respected and to be needed. We want to feel competent, independent and in control. And that’s about it.

Whatever happens to technology, we will manipulate our environment to achieve these primary goals. That is what humans do. In the past we did not surrender to big business: we regulated it. In the future, we will not surrender to artificial intelligence, or to the internet giants. We will regulate them too and we will not surrender to the machine. The scientists and technologists will create the possibilities, but it is society that will decide the way we go.