Of all the decisions you make when starting a business, probably the most important one relating to taxes is the type of legal structure you select for your company.

Not only will this decision have an impact on how much you pay in taxes, but it will affect the amount of paperwork your business is required to do, the personal liability you face, and your ability to raise money.

The most common forms of business are sole proprietorship, partnership, corporation, and S corporation. A more recent development to these forms of business is the limited liability company (LLC) and the limited liability partnership (LLP). Because each business form comes with different tax consequences, you will want to make your selection wisely and choose the structure that most closely matches your business’s needs.

If you decide to start your business as a sole proprietorship but later decide to take on partners, you can reorganize as a partnership or other entity. If you do this, be sure you notify the IRS as well as your state tax agency.

tip

![]()

![]()

If you operate as a sole proprietor, be sure you keep your business income and records separate from your personal finances. It helps to establish a business checking account and get a credit card to use only for business expenses. This will be invaluable at tax time and help you keep your accounts in order.

Sole Proprietorship

The simplest structure is the sole proprietorship, which usually involves just one individual who owns and operates the enterprise. If you intend to work alone, this structure may be the way to go.

The tax aspects of a sole proprietorship are appealing because the expenses and your income from the business are included on your personal income tax return, Form 1040. Your profits and losses are recorded on a form called Schedule C, which is filed with your 1040. The “bottom-line amount” from Schedule C is then transferred to your personal tax return. This is especially attractive because business losses you suffer may offset the income you have earned from your other sources.

As a sole proprietor, you must also file a Schedule SE with Form 1040. You use Schedule SE to calculate how much self-employment tax you owe. In addition to paying annual self-employment taxes, you must make estimated tax payments if you expect to owe at least $1,000 in federal taxes for the year after deducting your withholding and credits, and your withholding will be less than the smaller of: 1) 90 percent of the tax to be shown on your current year tax return or 2) 100 percent of your previous year’s tax liability. The federal government permits you to pay estimated taxes in four equal amounts throughout the year on the 15th of April, June, September, and January. With a sole proprietorship, your business earnings are taxed only once, unlike other business structures. Another big plus is that you will have complete control over your business—you make all the decisions.

There are a few disadvantages to consider, however. Selecting the sole proprietorship business structure means you are personally responsible for your company’s liabilities. As a result, you are placing your assets at risk, and they could be seized to satisfy a business debt or a legal claim filed against you.

Raising money for a sole proprietorship can also be difficult. Banks and other financing sources may be reluctant to make business loans to sole proprietorships. In most cases, you will have to depend on your financing sources, such as savings, home equity, or family loans.

“Success seems to be connected to action. Successful people keep moving. They make mistakes, but they never quit.”

—J. WILLARD MARRIOTT, FOUNDER OF MARRIOTT INTERNATIONAL INC.

Partnership

If your business will be owned and operated by several individuals, you’ll want to take a look at structuring your business as a partnership. Partnerships come in two varieties: general partnerships and limited partnerships. In a general partnership, the partners manage the company and assume responsibility for the partnership’s debts and other obligations. A limited partnership has both general and limited partners. The general partners own and operate the business and assume liability for the partnership, while the limited partners serve as investors only; they have no control over the company and are not subject to the same liabilities as the general partners.

Unless you expect to have many passive investors, limited partnerships are generally not the best choice for a new business because of all the required filings and administrative complexities. If you have two or more partners who want to be actively involved, a general partnership would be much easier to form.

One of the major advantages of a partnership is the tax treatment it enjoys. A partnership does not pay tax on its income but “passes through” any profits or losses to the individual partners. At tax time, the partnership must file a tax return (Form 1065) that reports its income and loss to the IRS. In addition, each partner reports his or her share of income and loss on Schedule K-1 of Form 1065.

Personal liability is a major concern if you use a general partnership to structure your business. Like sole proprietors, general partners are personally liable for the partnership’s obligations and debts. Each general partner can act on behalf of the partnership, take out loans, and make decisions that will affect and be binding on all the partners (if the partnership agreement permits). Keep in mind that partnerships are also more expensive to establish than sole proprietorships because they require more legal and accounting services.

![]() Howdy, Partner!

Howdy, Partner!

If you decide to organize your business as a partnership, be sure you draft a partnership agreement that details how business decisions are made, how disputes are resolved, and how to handle a buyout. You’ll be glad you have this agreement if for some reason you run into difficulties with one of the partners or if someone wants out of the arrangement.

The agreement should address the purpose of the business and the authority and responsibility of each partner. It’s a good idea to consult an attorney experienced with small businesses for help in drafting the agreement. Here are some other issues you’ll want the agreement to address:

![]() How will the ownership interest be shared? It’s not necessary, for example, for two owners to equally share ownership and authority. However, if you decide to do it, make sure the proportion is stated clearly in the agreement.

How will the ownership interest be shared? It’s not necessary, for example, for two owners to equally share ownership and authority. However, if you decide to do it, make sure the proportion is stated clearly in the agreement.

![]() How will decisions be made? It’s a good idea to establish voting rights in case a major disagreement arises. When just two partners own the business 50–50, there’s the possibility of a deadlock. To avoid a deadlock, some businesses provide in advance for a third partner, a trusted associate who may own only one percent of the business but whose vote can break a tie.

How will decisions be made? It’s a good idea to establish voting rights in case a major disagreement arises. When just two partners own the business 50–50, there’s the possibility of a deadlock. To avoid a deadlock, some businesses provide in advance for a third partner, a trusted associate who may own only one percent of the business but whose vote can break a tie.

![]() When one partner withdraws, how will the purchase price be determined? One possibility is to agree on a neutral third party, such as your banker or accountant, to find an appraiser to determine the price of the partnership interest.

When one partner withdraws, how will the purchase price be determined? One possibility is to agree on a neutral third party, such as your banker or accountant, to find an appraiser to determine the price of the partnership interest.

![]() If a partner withdraws from the partnership, when will the money be paid? Depending on the partnership agreement, you can agree that the money be paid over three, five, or ten years, with interest. You don’t want to be hit with a cash-flow crisis if the entire price has to be paid on the spot in one lump sum.

If a partner withdraws from the partnership, when will the money be paid? Depending on the partnership agreement, you can agree that the money be paid over three, five, or ten years, with interest. You don’t want to be hit with a cash-flow crisis if the entire price has to be paid on the spot in one lump sum.

Corporation

The corporate structure is more complex and expensive than most other business structures. A corporation is an independent legal entity, separate from its owners, and as such, it requires complying with more regulations and tax requirements.

The biggest benefit for a business owner who decides to incorporate is the liability protection he or she receives. A corporation’s debt is not considered that of its owners, so if you organize your business as a corporation, you are not putting your personal assets at risk. A corporation also can retain some of its profits without the owner paying tax on them.

warning

![]()

![]()

Many cities require even the smallest enterprises to have a business license. Municipalities are mainly concerned with whether the area where the business is operating is zoned for its intended purpose and whether there’s adequate customer parking available. You may even need a zoning variance to operate in some cities. Expect to pay a nominal license fee of around $30.

Another plus is the ability of a corporation to raise money. A corporation can sell stock, either common or preferred, to raise funds. Corporations also continue indefinitely, even if one of the shareholders dies, sells the shares, or becomes disabled. The corporate structure, however, comes with a number of downsides. A major one is higher costs.

Corporations are formed under the laws of each state with its own set of regulations. You will probably need the assistance of an attorney to guide you. In addition, because a corporation must follow more complex rules and regulations than a partnership or sole proprietorship, it requires more accounting and tax preparation services.

Another drawback to forming a corporation: Owners of the corporation pay a double tax on the business’s earnings. Not only are corporations subject to corporate income tax at both the federal and state levels, but any earnings distributed to shareholders in the form of dividends are taxed at individual tax rates on their personal income tax returns.

One strategy to help soften the blow of double taxation is to pay some money out as salary to you and any other corporate shareholders who work for the company. A corporation is not required to pay tax on earnings paid as reasonable compensation, and it can deduct the payments as a business expense. However, the IRS has limits on what it believes to be reasonable compensation.

![]() The ABCs of LLC

The ABCs of LLC

Limited liability companies, often referred to as “Lacs,” have been around since 1977, but their popularity among entrepreneurs is a relatively recent phenomenon. An LLC is a hybrid entity, bringing together some of the best features of partnerships and corporations. The advantage of an LLC over a sole proprietorship is that the owner is not personally responsible for the liabilities of the company if appropriate business formalities are followed.

Like a sole proprietorship, earnings flow to the owner, are taxed only at the personal level, and are subject to the self-employment tax. While somewhat more complex than a sole proprietorship, establishing an LLC is relatively simple. There is no limitation on the number of shareholders an LLC can have. In addition, any member or owner of the LLC is allowed a full participatory role in the business’s operation; in a limited partnership, on the other hand, partners are not permitted any say in the operation.

warning

![]()

![]()

Any money you’ve invested in a corporation is at risk. Despite the liability protection of a corporation, most banks and many suppliers require business owners to sign a personal guarantee so they know corporate owners will make good on any debt if the corporation can’t.

S Corporation

The S corporation is more attractive to small-business owners than a regular (or C) corporation. That’s because an S corporation has some appealing tax benefits and still provides business owners with the liability protection of a corporation. With an S corporation, income and losses are passed through to shareholders and included on their individual tax returns. As a result, there’s just one level of federal tax to pay.

warning

![]()

![]()

Like an LLC, the owner of an S Corp is not personally responsible for the liabilities of the company. One note of caution is that if the formalities of setting up and running an S Corp are not followed, the owner’s protection from the liabilities of the company may be forfeited.

In addition, owners of S corporations who don’t have inventory can use the cash method of accounting, which is simpler than the accrual method. Under this method, income is taxable when received and expenses are deductible when paid (see Chapter 37).

S corporations can also have up to 100 shareholders. This makes it possible to have more investors and thus attract more capital, tax experts maintain.

![]() Corporate Checklist

Corporate Checklist

To make sure your corporation stays on the right side of the law, heed the following guidelines:

![]() Call the secretary of state each year to check your corporate status.

Call the secretary of state each year to check your corporate status.

![]() Put the annual meetings (shareholders and directors) on tickler cards.

Put the annual meetings (shareholders and directors) on tickler cards.

![]() Check all contracts to ensure the proper name is used in each. The signature line should read “John Doe, President, XYZ Corp.,” never just “John Doe.”

Check all contracts to ensure the proper name is used in each. The signature line should read “John Doe, President, XYZ Corp.,” never just “John Doe.”

![]() Never use your name followed by “dba” (doing business as) on a contract. Renegotiate any old ones that do.

Never use your name followed by “dba” (doing business as) on a contract. Renegotiate any old ones that do.

![]() Before undertaking any activity out of the normal course of business—like purchasing major assets—write a corporate resolution permitting it. Keep all completed forms in the corporate book.

Before undertaking any activity out of the normal course of business—like purchasing major assets—write a corporate resolution permitting it. Keep all completed forms in the corporate book.

![]() Never use corporate checks for personal debts and vice versa.

Never use corporate checks for personal debts and vice versa.

![]() Get professional advice about continued retained earnings not needed for immediate operating expenses.

Get professional advice about continued retained earnings not needed for immediate operating expenses.

warning

![]()

![]()

If you anticipate several years of losses in your business, keep in mind you cannot deduct corporate losses on your personal tax return. Business structures such as partnerships, sole proprietorships, and S corporations allow you to take those deductions.

S corporations do come with some downsides. For example, S corporations are subject to many of the same rules corporations must follow, and that means higher legal and tax service costs. They also must file articles of incorporation, hold directors and shareholders meetings, keep corporate minutes, and allow shareholders to vote on major corporate decisions. The legal and accounting costs of setting up an S corporation are also similar to those for a regular corporation.

Another major difference between a regular corporation and an S corporation is that S corporations can only issue one class of stock. Experts say this can hamper the company’s ability to raise capital.

In addition, unlike in a regular corporation, S corporation stock can only be owned by individuals, estates, and certain types of trusts. In 1998, tax-exempt organizations such as qualified pension plans were added to the list. This change provides S corporations with even greater access to capital because a number of pension plans are willing to invest in closely held small-business stock.

Putting Inc. to Paper

To start the process of incorporating, contact the secretary of state or the state office that is responsible for registering corporations in your state. Ask for instructions, forms, and fee schedules on incorporating.

It is possible to file for incorporation without the help of an attorney by using books and software to guide you. Your expense will be the cost of these resources, the filing fees and other costs associated with incorporating in your state.

If you do it yourself, you will save the expense of using a lawyer, which can cost from $500 to $5,000 if you choose a firm that specializes in startup businesses. The disadvantage is that the process may take you some time to accomplish. There is also a chance you could miss some small but important detail in your state’s law.

One of the first steps in the incorporation process is to prepare a certificate or articles of incorporation. Some states provide a printed form for this, which either you or your attorney can complete. The information requested includes the proposed name of the corporation, the purpose of the corporation, the names and addresses of those incorporating, and the location of the principal office of the corporation. The corporation will also need a set of bylaws that describe in greater detail than the articles how the corporation will run, including the responsibilities of the company’s shareholders, directors, and officers; when stockholder meetings will be held; and other details important to running the company. Once your articles of incorporation are accepted, the secretary of state’s office will send you a certificate of incorporation.

![]() In Other Words

In Other Words

If you are starting a sole proprietorship or a partnership, you have the option of choosing a business name, or dba (“doing business as”), for your business. This is known as a fictitious business name. If you want to operate your business under a name other than your own (for instance, Carol Axelrod doing business as “Darling Donut Shoppe”), you may be required by the county, city, or state to register your fictitious name.

Procedures for doing this vary among states. In many states, all you have to do is go to the county offices and pay a registration fee to the county clerk. In other states, you also have to place a fictitious name ad in a local newspaper for a certain length of time. The cost of filing a fictitious name notice ranges from about $40 to $125. Your local bank may require a fictitious name certificate to open a business account for you; if so, a bank officer can tell you where to go to register.

In most states, corporations don’t have to file fictitious business names unless the owner(s) do business under a name other than their own. In effect, incorporation documents are to corporate businesses what fictitious name filings are to sole proprietorships and partnerships.

Rules of the Road

Once you are incorporated, be sure to follow the rules of incorporation. If you fail to do so, a court can pierce the corporate veil and hold you and the other business owners personally liable for the business’s debts.

“Nobody can be a success if they don’t love their work.”

—DAVID SARNOFF, CHAIRMAN OF RCA

It is important to follow all the rules required by state law. You should keep accurate financial records for the corporation, showing a separation between the corporation’s income and expenses and those of the owners.

The corporation should also issue stock, file annual reports, and hold yearly meetings to elect company officers and directors, even if they’re the same people as the shareholders. Be sure to keep minutes of shareholders’ and directors’ meetings. On all references to your business, make certain to identify it as a corporation, using Inc. or Corp., whichever your state requires. You also want to make sure that whomever you will be dealing with, such as your banker or clients, knows that you are an officer of a corporation. (For more corporate guidelines, see “Corporate Checklist” on page 123.)

Setting up an LLC

If limited liability is not a concern for your business, you could begin as a sole proprietorship or a partnership so “passed through” losses in the early years of the company can be used to offset your other income. After the business becomes profitable, you may want to consider another type of legal structure.

To set up an LLC, you must file articles of organization with the secretary of state in the state where you intend to do business. Some states also require you to file an operating agreement, which is similar to a partnership agreement. Like partnerships, LLCs do not have perpetual life. Some state statutes stipulate that the company must dissolve after 30 years. Technically, the company dissolves when a member dies, quits, or retires.

If you plan to operate in several states, you must determine how a state will treat an LLC formed in another state. If you decide on an LLC structure, be sure to use the services of an experienced accountant who is familiar with the various rules and regulations of LLCs.

Another recent development is the limited liability partnership (LLP). With an LLP, the general partners have limited liability. For example, the partners are liable for their own malpractice and not that of their partners. This legal form works well for those involved in a professional practice, such as physicians.

The Nonprofit Option

What about organizing your venture as a nonprofit corporation? Unlike a for-profit business, a nonprofit may be eligible for certain benefits, such as sales, property, and income tax exemptions at the state level. The IRS points out that while most federal tax-exempt organizations are nonprofit organizations, organizing as a nonprofit at the state level does not automatically grant you an exemption from federal income tax.

![]() Laying the Foundation

Laying the Foundation

When making a decision about which business structure to use, answering the following questions should help you narrow down which entity is right for you:

![]() How many owners will your company have, and what will their roles be?

How many owners will your company have, and what will their roles be?

![]() Are you concerned about the tax consequences of your business structure?

Are you concerned about the tax consequences of your business structure?

![]() Do you want to consider having employees become owners in the company?

Do you want to consider having employees become owners in the company?

![]() Can you deal with the added costs that come with selecting a complicated business structure?

Can you deal with the added costs that come with selecting a complicated business structure?

![]() How much paperwork are you prepared to deal with?

How much paperwork are you prepared to deal with?

![]() Do you want to make all the decisions in the company?

Do you want to make all the decisions in the company?

![]() Are you planning to go public?

Are you planning to go public?

![]() Do you want to protect your personal resources from debts or other claims against your company?

Do you want to protect your personal resources from debts or other claims against your company?

![]() Are family succession issues a concern?

Are family succession issues a concern?

e-fyi

![]()

![]()

To help sort through the business structure maze, you can order free IRS publications—Partnerships (Publication 541), Corporations (Publication 542), and Taxation of Limited Liability Companies (Publication 3402)—by downloading them from the IRS website at irs.gov.

Another major difference between a profit and nonprofit business deals with the treatment of the profits. With a for-profit business, the owners and shareholders generally receive the profits. With a nonprofit, any money that is left after the organization has paid its bills is put back into the organization. Some types of nonprofits can receive contributions that are tax deductible to the individual who contributes to the organization. Keep in mind that nonprofits are organized to provide some benefit to the public.

Nonprofits are incorporated under the laws of the state in which they are established. To receive federal tax-exempt status, the organization must apply with the IRS. First, you must have an Employer Identification Number (EIN) and then apply for recognition of exemption by filing Form 1023 (Application for Recognition of Exemption Under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) or Form 1024 (Application for Recognition of Exemption under Section 501(a)) with the necessary filing fee. Both forms are available online at irs.gov. (For information on how to apply for an EIN, see Chapter 41.)

The IRS identifies the different types of nonprofit organizations by the tax code by which they qualify for exempt status. One of the most common forms is 501(c)(3), which is set up to do charitable, educational, scientific, religious, and literary work. This includes a wide range of organizations, from continuing education centers to outpatient clinics and hospitals.

The IRS also mandates that there are certain activities tax-exempt organizations can’t engage in if they want to keep their exempt status. For example, a section 50l(c)(3) organization cannot intervene in political campaigns.

Remember, nonprofits still have to pay employment taxes, but in some states they may be exempt from paying sales tax. Check with your state to make sure you understand how nonprofit status is treated in your area. In addition, nonprofits may be hit with unrelated business income tax. This is regular income from a trade or business that is not substantially related to the charitable purpose. Any exempt organization under Section 501(a) or Section 529(a) must file Form 990-T (Exempt Organization Business Income Tax Return) if the organization has gross income of $1,000 or more from an unrelated business, and pay tax on the income.

“To be successful in business, you need friends. To be very successful, you need enemies.”

—CHRISTOPHER ONDAATJE, CANADIAN FINANCIER AND PHILANTHROPIST

If your nonprofit has revenues of more than $25,000 a year, be sure to file an annual report (Form 990) with the IRS. Form 990-EZ is a shortened version of 990 and is designed for use by small exempt organizations with incomes of less than $1 million.

Form 990 asks you to provide information on the organization’s income, expenses, and staff salaries. You also may have to comply with a similar state requirement. The IRS report must be made available for public review. If you use the calendar year as your accounting period (see Chapter 41), file Form 990 by May 15.

For more information on IRS tax-exempt status, download IRS Publication 557 (Tax-Exempt Status for Your Organization) at irs.gov.

Even after you settle on a business structure, remember that the circumstances that make one type of business organization favorable are always subject to changes in the laws. It makes sense to reassess your form of business from time to time to make sure you are using the one that provides the most benefits.

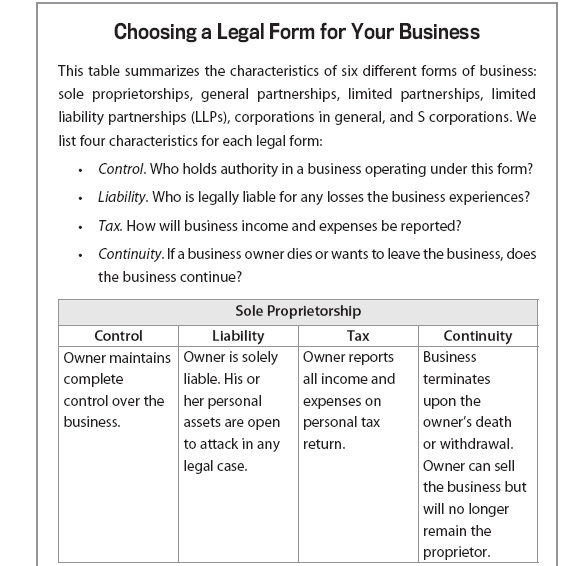

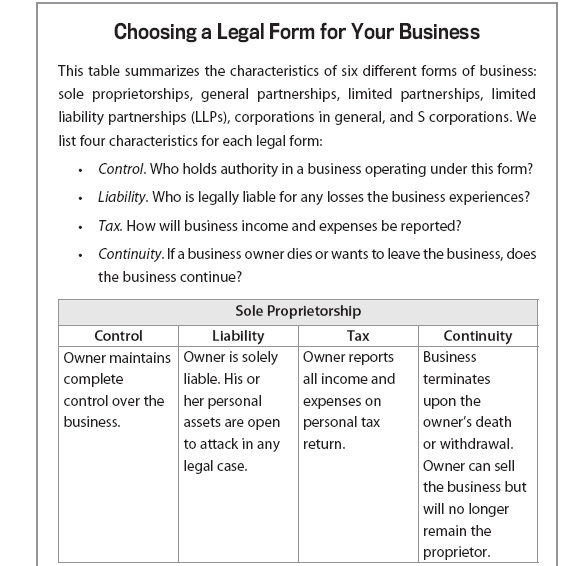

Figure 9.1. Choosing a Legal Form for Your Business