Effectively Managing Your Finances

Now that you have the framework for establishing a bookkeeping system and for creating financial statements, what’s next? In this chapter, we will explore how to analyze the data that results from an effective financial management and control system. Additionally, we’ll consider the key elements of a good budgeting system. The financial analysis tools we will discuss are: gross profit margin and markup, break-even, working capital, and financial ratio analyses. In the section on budgeting, we will look at when, what, and how to budget as well as how to perform a sensitivity analysis.

“Success is the ability to go from one failure to another without the loss of enthusiasm.”

—WINSTON CHURCHILL

Gross Profit Margin and Markup

One of the most important financial concepts you will need to learn in running your new business is the computation of gross profit. And the tool that you use to maintain gross profit is markup.

The gross profit on a product sold is computed as:

Sales – Cost of Goods Sold = Gross Profit

To understand gross profit, it is important to know the distinction between variable and fixed costs. Variable costs are those that change based on the amount of product being made and are incurred as a direct result of producing the product. Variable costs include:

![]() Materials used

Materials used

![]() Direct labor

Direct labor

![]() Packaging

Packaging

![]() Freight

Freight

![]() Plant supervisor salaries

Plant supervisor salaries

![]() Utilities for a plant or a warehouse

Utilities for a plant or a warehouse

![]() Depreciation expense on production equipment and machinery

Depreciation expense on production equipment and machinery

Fixed costs generally are more static in nature. They include:

![]() Office expenses such as supplies, utilities, a telephone for the office, etc.

Office expenses such as supplies, utilities, a telephone for the office, etc.

![]() Salaries and wages of office staff, salespeople, officers, and owners

Salaries and wages of office staff, salespeople, officers, and owners

![]() Payroll taxes and employee benefits

Payroll taxes and employee benefits

![]() Advertising, promotional, and other sales expenses

Advertising, promotional, and other sales expenses

![]() Insurance

Insurance

![]() Auto expenses for salespeople

Auto expenses for salespeople

![]() Professional fees

Professional fees

![]() Rent

Rent

Variable expenses are recorded as cost of goods sold. Fixed expenses are counted as operating expenses (sometimes called selling and general and administrative expenses).

Gross Profit Margin

While the gross profit is a dollar amount, the gross profit margin is expressed as a percentage. It’s equally important to track since it allows you to keep an eye on profitability trends. This is critical, because many businesses have gotten into financial trouble with an increasing gross profit that coincided with a declining gross profit margin. The gross profit margin is computed as follows:

Gross Profit ÷ Sales = Gross Profit Margin

There are two key ways for you to improve your gross profit margin. First, you can increase your prices. Second, you can decrease the costs to produce your goods. Of course, both are easier said than done.

An increase in prices can cause sales to drop. If sales drop too far, you may not generate enough gross profit dollars to cover operating expenses. Price increases require a very careful reading of inflation rates, competitive factors, and basic supply and demand for the product you are producing.

The second method of increasing gross profit margin is to lower the variable costs to produce your product. This can be accomplished by decreasing material costs or making the product more efficiently. Volume discounts are a good way to reduce material costs. The more material you buy from suppliers, the more likely they are to offer you discounts. Another way to reduce material costs is to find a less costly supplier. However, you might sacrifice quality if the goods purchased are not made as well.

tip

![]()

![]()

As you start your business, it will be important to track external financial trends to ensure you are headed in the right direction. It also will be critical to compare your company’s performance to others in your industry. If you are a member of a trade association, the group should offer comparative industry data. Information may also be available from your CPA or banker.

Whether you are starting a manufacturing, wholesaling, retailing, or service business, you should always be on the lookout for ways to deliver your product or service more efficiently. However, you also must balance efficiency and quality issues to ensure that they do not get out of balance.

Let’s look at the gross profit of ABC Clothing Inc. (see page 615) as an example of the computation of gross profit margin. In Year 1, the sales were $1 million and the gross profit was $250,000, resulting in a gross profit margin of 25 percent ($250,000/$1 million). In Year 2, sales were $1.5 million and the gross profit was $450,000, resulting in a gross profit margin of 30 percent ($450,000/$1.5 million).

It is apparent that ABC Clothing earned not only more gross profit dollars in Year 2, but also a higher gross profit margin. The company either raised prices, lowered variable material costs from suppliers, or found a way to produce its clothing more efficiently (which usually means fewer labor hours per product produced).

Computing Markup

ABC Clothing did a better job in Year 2 of managing its markup on the clothing products that they manufactured. Many business owners often get confused when relating markup to gross profit margin. They are first cousins in that both computations deal with the same variables. The difference is that gross profit margin is figured as a percentage of the selling price, while markup is figured as a percentage of the seller’s cost.

Markup is computed as follows:

(Selling Price – Cost to Produce) ÷ Cost to Produce = Markup Percentage

Let’s compute markup for ABC Clothing for Year 1:

($1 million – $750,000) ÷ $750,000 = 33.3%

Now, let’s compute markup for ABC Clothing for Year 2:

($1.5 million – $1.05 million) ÷ $1.05 million = 42.9%

While computing markup for an entire year for a business is very simple, using this valuable markup tool daily to work up price quotes is more complicated. However, it is even more vital. Computing markup on last year’s numbers helps you understand where you’ve been and gives you a benchmark for success. But computing markup on individual jobs will affect your business going forward and can often make the difference in running a profitable operation.

In bidding individual jobs, you must carefully estimate the variable costs associated with each job. And the calculation is different in that you typically seek a desired markup with a known cost to arrive at the price quote. Here is the computation to find a price quote using markup:

(Desired Markup x Total Variable Costs) + Total Variable Costs = Price Quote

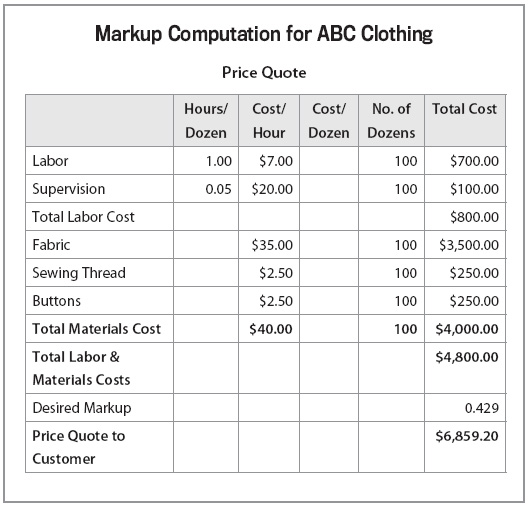

Let’s again use ABC Clothing as an example. ABC has been asked to quote on a job to produce 100 dozen shirts. Based on prior experience, the owner estimates that the job will require 100 labor hours of direct labor and five hours of supervision from the plant manager. The total material costs based on quotes from suppliers (fabric, sewing thread, buttons, etc.) will be $40 per dozen. If ABC Clothing seeks a markup of 42.9 percent on all orders in Year 2, it would use a markup table (like the one on page 630) to calculate the price quote.

aha!

![]()

![]()

When you set up your computerized bookkeeping system to create automatic monthly financial statements, make sure you also automate your business’s financial ratios. There’s no sense in having to compute them manually when the information is available on your PC. Reviewing financial ratios monthly will help you keep an eye on your business’s financial trends.

What if you are a new business owner and don’t have any experience to base an estimate on? Then you will need to research material costs by getting quotes from suppliers as well as study the labor rates in the area. You should also research industry manufacturing prices. Armed with this information, you will have a well-educated “guess” to base your job quote on.

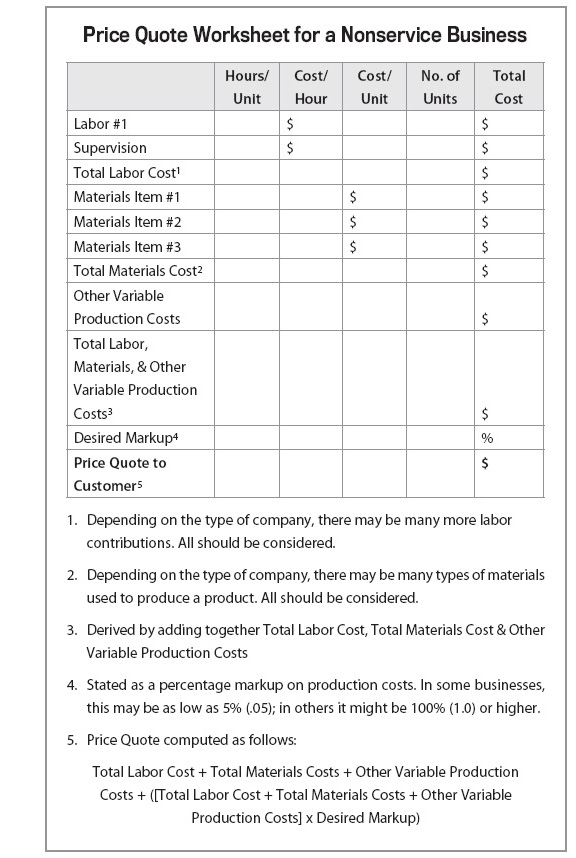

How you use markup to set prices will depend on the type of business you are starting. If you are launching a manufacturing, wholesale, or retail operation, you will be able to compute markup using the aforementioned formulas to factor in all the variables in the cost of producing or generating the items you will be selling. Markup can also be used to bid one job or to set prices for an entire product line.

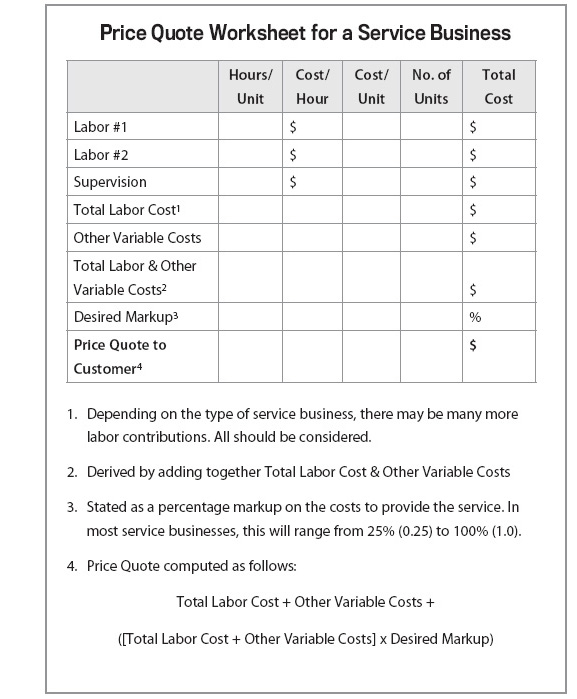

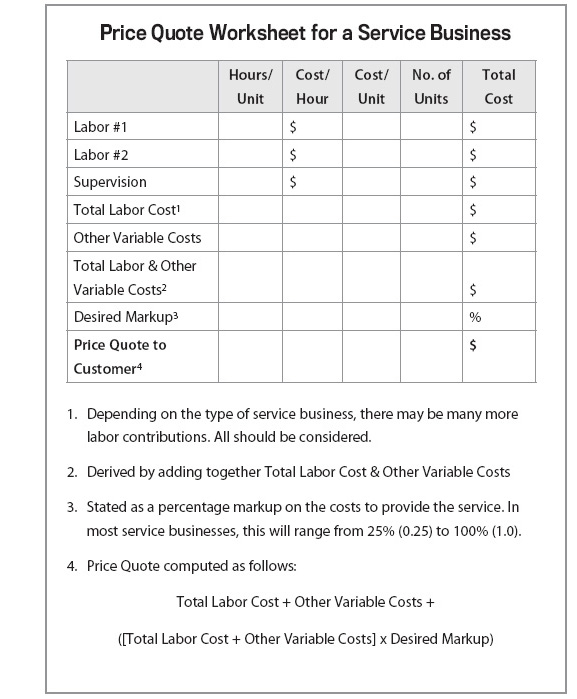

If you are starting a service business, however, markup is more difficult to calculate, particularly for new business owners. With most service businesses, the key variable cost associated with delivering the service to your customers will be you and your employees’ time. In computing proper markup for a service business, you must pay close attention to the time spent to provide the service to customers, as well as to market prices of the services provided. In starting a service business, you will need to research the going rate paid to employees and the market prices for the services you will be providing.

Figure 39.1. Markup Computation for ABC Clothing

warning

![]()

![]()

You must include break-even analyses as part of your pricing policy to ensure you’re making money on every unit you sell and that you’re able to be profitable based on your costs and sales. If you’re not profitable, you won’t stay in business. It’s as simple as that.

For instance, if you are starting a staffing service, you will need to know what rate is typically paid to employees in this industry as well as the market rate charged to your customers for temporary labor. This will enable you to compute the proper markup in setting your price to ensure that you will be profitable.

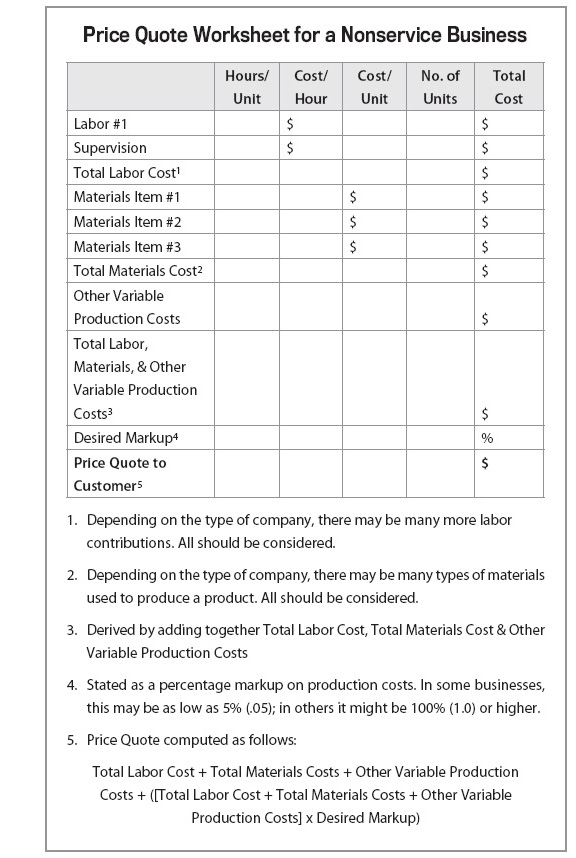

Figure 39.2. Price Quote Worksheet for a Service Business

(See the “Markup Computation” chart on page 630 for how the price quote was calculated for ABC Clothing, and use the worksheets above and on page 632 to come up with quotes for your own business.)

Figure 39.3. Price Quote Worksheet for a Nonservice Business

Break-Even Analysis

One useful tool in tracking your business’s cash flow will be the break-even analysis. It is a fairly simple calculation and can prove very helpful in deciding whether to make an equipment purchase or in knowing how close you are to your break-even level. Here are the variables needed to compute a break-even sales analysis:

![]() Gross profit margin

Gross profit margin

![]() Operating expenses (less depreciation)

Operating expenses (less depreciation)

![]() Total of monthly debt payments for the year (annual debt service)

Total of monthly debt payments for the year (annual debt service)

Since we are dealing with cash flow, and depreciation is a noncash expense, it is subtracted from the operating expenses. The break-even calculation for sales is:

(Operating Expenses + Annual Debt Service) ÷ Gross Profit Margin = Break-Even Sales

Let’s use ABC Clothing as an example and compute this company’s break-even sales for Years 1 and 2:

*This represents the principal portion of annual debt service; the interest portion of annual debt service is already included in operating expenses.

Break-Even Sales for Year 1:

($170,000 + $30,000) ÷ .25 = $800,000

Break-Even Sales for Year 2:

($245,000 + $30,000) ÷ .30 = $916,667

It is apparent from these calculations that ABC Clothing was well ahead of break-even sales both in Year 1 ($1 million in sales) and Year 2 ($1.5 million).

Break-even analysis also can be used to calculate break-even sales needed for the other variables in the equation. Let’s say the owner of ABC Clothing was confident he or she could generate sales of $750,000, and the company’s operating expenses are $170,000 with $30,000 in annual current maturities of long-term debt. The break-even gross margin needed would be calculated as follows:

($170,000 + $30,000) ÷ $750,000 = 26.7%

Now let’s use ABC Clothing to determine the break-even operating expenses. If we know that the gross margin is 25 percent, the sales are $750,000, and the current maturities of long-term debt are $30,000, we can calculate the break-even operating expenses as follows:

(.25 x $750,000) – $30,000 = $157,500

Working Capital Analysis

Working capital is one of the most difficult financial concepts for the small-business owner to understand. In fact, the term means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. By definition, working capital is the amount by which current assets exceed current liabilities. However, if you simply run this calculation each period to try to analyze working capital, you won’t accomplish much in figuring out what your working capital needs are and how to meet them.

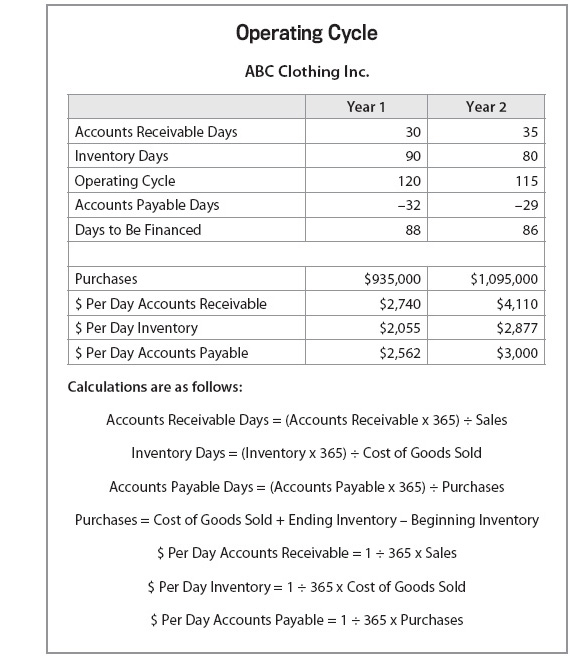

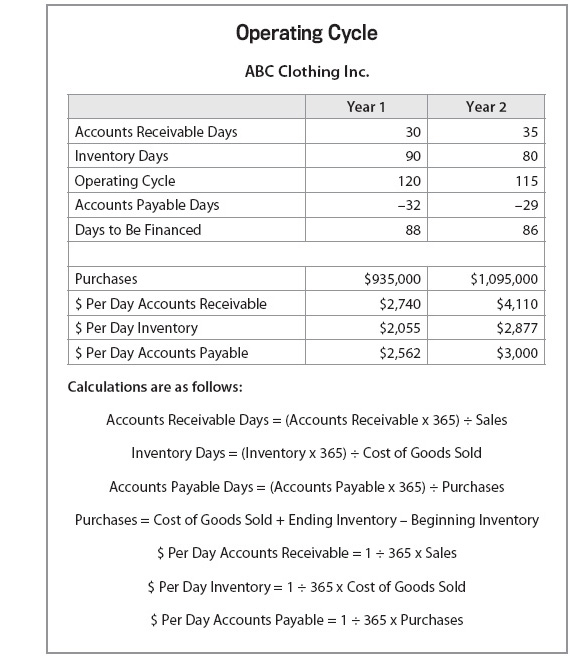

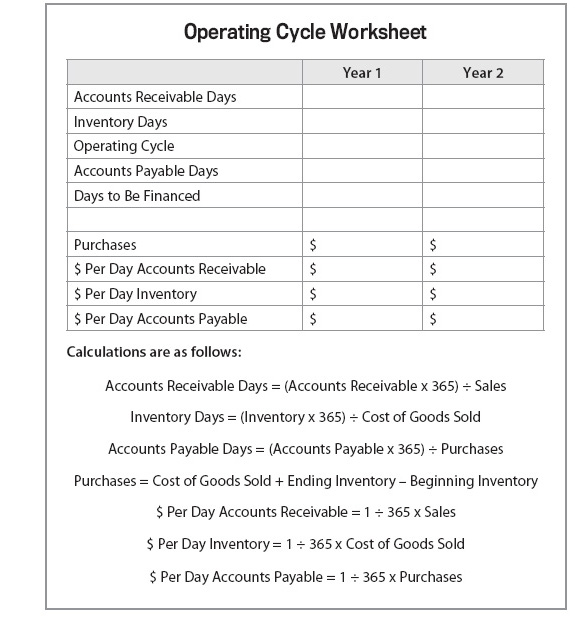

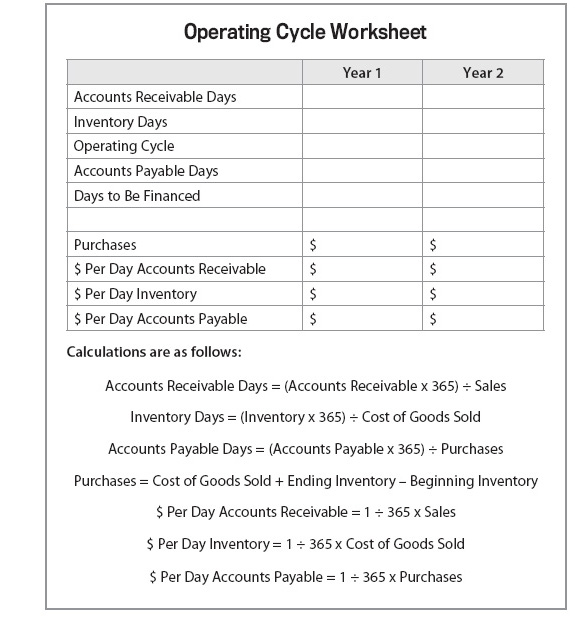

A more useful tool for determining your working capital needs is the operating cycle. The operating cycle analyzes the accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable cycles in terms of days. In other words, accounts receivable are analyzed by the average number of days it takes to collect an account. Inventory is analyzed by the average number of days it takes to turn over the sale of a product (from the point it comes in your door to the point it is converted to cash or an account receivable). Accounts payable are analyzed by the average number of days it takes to pay a supplier invoice.

Most businesses cannot finance the operating cycle (accounts receivable days + inventory days) with accounts payable financing alone. Consequently, working capital financing is needed. This shortfall is typically covered by the net profits generated internally or by externally borrowed funds or by a combination of the two.

Most businesses need short-term working capital at some point in their operations. For instance, retailers must find working capital to fund seasonal inventory buildup between September and November for Christmas sales. But even a business that is not seasonal occasionally experiences peak months when orders are unusually high. This creates a need for working capital to fund the resulting inventory and accounts receivable buildup.

Some small businesses have enough cash reserves to fund seasonal working capital needs. However, this is very rare for a new business. If your new venture experiences a need for short-term working capital during its first few years of operation, you will have several potential sources of funding. The important thing is to plan ahead. If you get caught off guard, you might miss out on the one big order that could put your business over the hump.

Here are the five most common sources of short-term working capital financing:

1. Equity. If your business is in its first year of operation and has not yet become profitable, then you might have to rely on equity funds for short-term working capital needs. These funds might be injected from your own personal resources or from a family member, a friend, or a third-party investor.

2. Trade creditors. If you have a particularly good relationship established with your trade creditors, you might be able to solicit their help in providing short-term working capital. If you have paid on time in the past, a trade creditor may be willing to extend terms to enable you to meet a big order. For instance, if you receive a big order that you can fulfill, ship out, and collect in 60 days, you could obtain 60-day terms from your supplier if 30-day terms are normally given. The trade creditor will want proof of the order and may want to file a lien on it as security, but if it enables you to proceed, that should not be a problem.

3. Factoring. Factoring is another resource for short-term working capital financing. Once you have filled an order, a factoring company buys your account receivable and then handles the collection. This type of financing is more expensive than conventional bank financing but is often used by new businesses.

4. Line of credit. Lines of credit are not often given by banks to new businesses. However, if your new business is well-capitalized by equity and you have good collateral, your business might qualify for one. A line of credit allows you to borrow funds for short-term needs when they arise. The funds are repaid once you collect the accounts receivable that resulted from the short-term sales peak. Lines of credit typically are made for one year at a time and are expected to be paid off for 30 to 60 consecutive days sometime during the year to ensure that the funds are used for short-term needs only.

5. Short-term loan. While your new business may not qualify for a line of credit from a bank, you might have success in obtaining a one-time short-term loan (less than a year) to finance your temporary working capital needs. If you have established a good banking relationship with a banker, he or she might be willing to provide a short-term note for one order or for a seasonal inventory and/or accounts receivable buildup.

In addition to analyzing the average number of days it takes to make a product (inventory days) and collect on an account (accounts receivable days) vs. the number of days financed by accounts payable, the operating cycle analysis provides one other important analysis.

tip

![]()

![]()

If you decide to hire a factoring company, you could Google “Factoring” to start your search, but a safer bet is to call your bank for a recommendation. You might also want to seek recommendations from your industry’s trade associations or local business chamber of commerce.

From the operating cycle, a computation can be made of the dollars required to support one day of accounts receivable and inventory, and the dollars provided by a day of accounts payable. Let’s consider ABC Clothing’s operating cycle (see page 637). Had the company maintained accounts receivable at Year 1 levels in Year 2, it would have freed up $20,550 in cash flow ($4,110 x 5 days). Likewise, the ten-day improvement in inventory management in Year 2 enhanced cash flow by $28,770 ($2,877 x 10 days).

You can see that working capital has a direct impact on cash flow in a business. Since cash flow is the name of the game for all business owners, a good understanding of working capital is imperative to making any venture successful.

Figure 39.4. Operating Cycle

Building a Financial Budget

For many small-business owners, the process of budgeting is limited to figuring out where to get the cash to meet next week’s payroll. There are so many financial fires to put out in a given week that it’s hard to find the time to do any short- or long-range financial planning. But failing to plan financially might mean that you are unknowingly planning to fail.

Business budgeting is one of the most powerful financial tools available to any small-business owner. Put simply, maintaining a good short- and long-range financial plan enables you to control your cash flow instead of having it control you.

Figure 39.5. Operating Cycle Worksheet

The most effective financial budget includes both a short-range month-to-month plan for at least a calendar year and a long-range quarter-to-quarter plan you use for financial statement reporting. It should be prepared during the two months preceding the fiscal year-end to allow ample time for sufficient information-gathering.

tip

![]()

![]()

Everything’s rosy, huh? Business owners tend to overestimate their income and underestimate expenses. So when preparing your budget, it’s always a good idea to have an objective third party review your information to make sure you’re being realistic.

The long-range plan should cover a period of at least three years (some go up to five years) on a quarterly basis, or even an annual basis. The long-term budget should be updated when the short-range plan is prepared.

While some owners prefer to leave the one-year budget unchanged for the year for which it provides projections, others adjust the budget during the year based on certain financial occurrences, such as an unplanned equipment purchase or a larger-than-expected upward sales trend. Using the budget as an ongoing planning tool during a given year certainly is recommended. However, here is a word to the wise: Financial budgeting is vital, but it is important to avoid getting so caught up in the budget process that you forget to keep doing business.

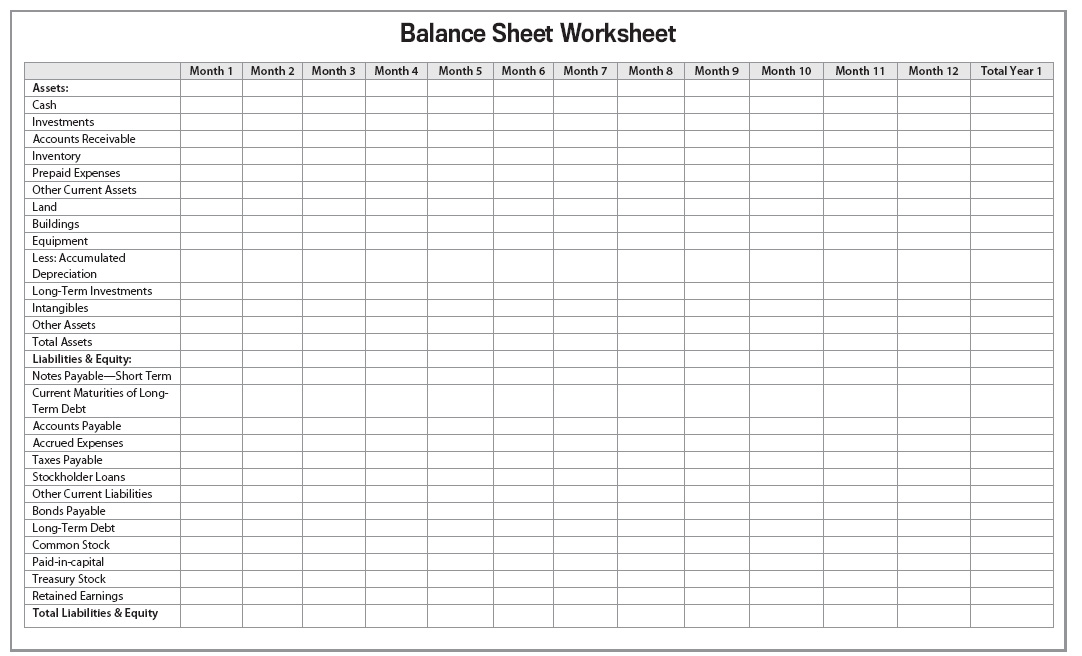

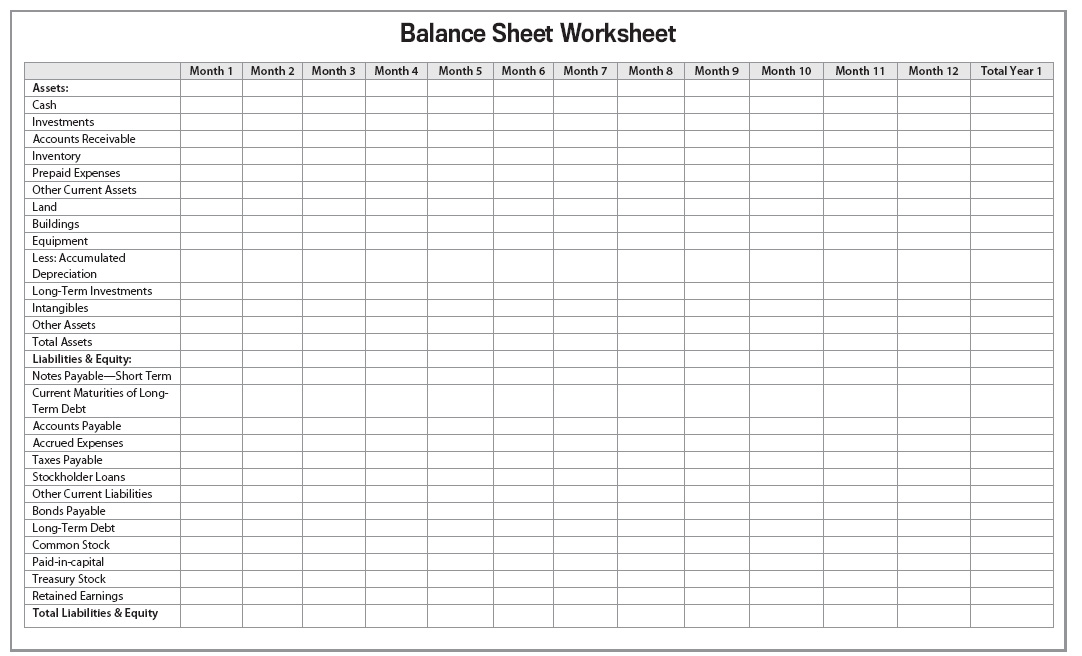

What Do You Budget?

Many financial budgets provide a plan only for the income statement; however, it is important to budget both the income statement and balance sheet. This enables you to consider potential cash-flow needs for your entire operation, not just as they pertain to income and expenses. For instance, if you had already been in business for a couple of years and were adding a new product line, you would need to consider the impact of inventory purchases on cash flow.

Budgeting only the income statement also doesn’t allow a full analysis of the effect of potential capital expenditures on your financial picture. For instance, if you are planning to purchase real estate for your operation, you need to budget the effect the debt service will have on cash flow. In the future, a budget can also help you determine the potential effects of expanding your facilities and the resulting higher rent payments or debt service.

tip

![]()

![]()

Budgeting shouldn’t be approached as something to do when you have time but instead as a priority and part of your overall business financial management plan. Breaking your budget into monthly increments eases the process, making it less overwhelming. Make some general financial goals for the year, then determine how you can achieve them through a monthly budget.

How Do You Budget?

In the startup phase, you will have to make reasonable assumptions about your business in establishing your budget. You will need to ask questions such as:

![]() How much can be sold in Year 1?

How much can be sold in Year 1?

![]() How much will sales grow in the following years?

How much will sales grow in the following years?

![]() How will the products and/or services you are selling be priced?

How will the products and/or services you are selling be priced?

![]() How much will it cost to produce your product? How much inventory will you need?

How much will it cost to produce your product? How much inventory will you need?

![]() What will your operating expenses be?

What will your operating expenses be?

![]() How many employees will you need? How much will you pay them? How much will you pay yourself? What benefits will you offer? What will your payroll and unemployment taxes be?

How many employees will you need? How much will you pay them? How much will you pay yourself? What benefits will you offer? What will your payroll and unemployment taxes be?

![]() What will the income tax rate be? Will your business be an S corporation or a C corporation?

What will the income tax rate be? Will your business be an S corporation or a C corporation?

![]() What will your facilities needs be? How much will it cost you in rent or debt service for these facilities?

What will your facilities needs be? How much will it cost you in rent or debt service for these facilities?

![]() What equipment will be needed to start the business? How much will it cost? Will there be additional equipment needs in subsequent years?

What equipment will be needed to start the business? How much will it cost? Will there be additional equipment needs in subsequent years?

![]() What payment terms will you offer customers if you sell on credit? What payment terms will your suppliers give you?

What payment terms will you offer customers if you sell on credit? What payment terms will your suppliers give you?

![]() How much will you need to borrow?

How much will you need to borrow?

![]() What will the collateral be? What will the interest rate be?

What will the collateral be? What will the interest rate be?

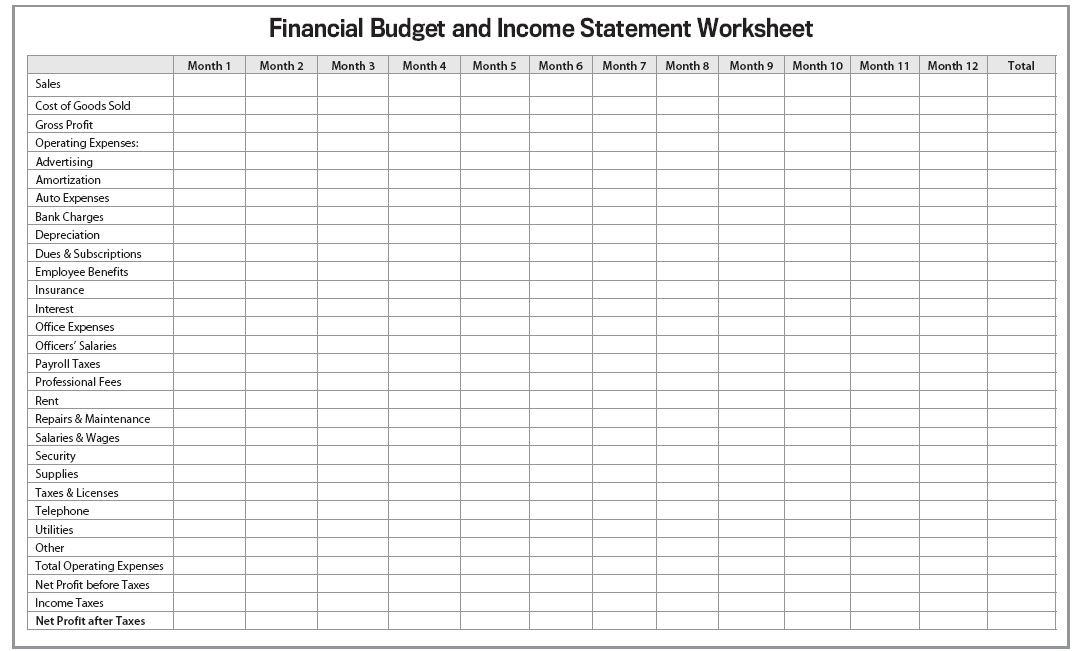

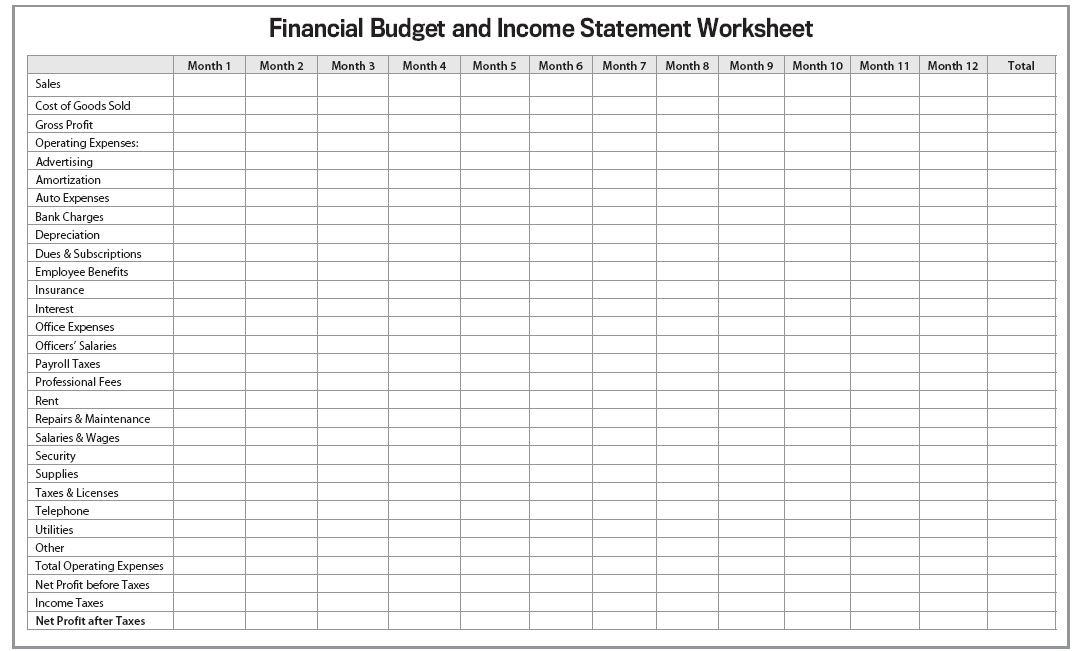

As for the actual preparation of the budget, you can create it manually or with the budgeting function that comes with most bookkeeping software packages. You can also purchase separate budgeting software such as Quicken or Microsoft Money. Yes, this seems like a lot of information to forecast. But it’s not as cumbersome as it looks. (See page 647 for a financial budget and income statement worksheet; you should find a similar format in any budgeting software.)

![]() How Do You Rate?

How Do You Rate?

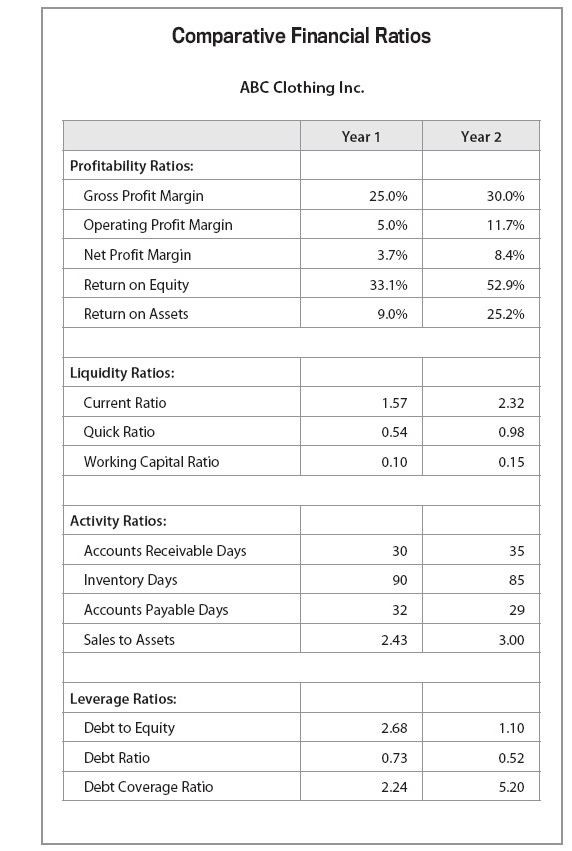

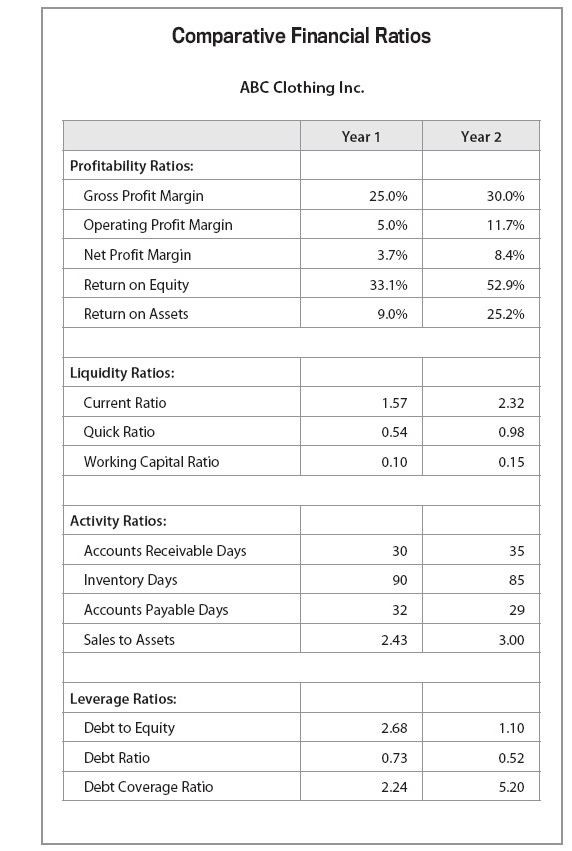

Ratio analysis is a financial management tool that enables you to compare the trends in your financial performance as well as provides some measurements to compare your performance against others in your industry. Comparing ratios from year to year highlights areas in which you are performing well and areas that need tweaking. Most industry trade groups can provide you with industry averages for key ratios that will provide a benchmark against which you can compare your company.

Financial ratios can be divided into four subcategories: profitability, liquidity, activity, and leverage. Here are 15 financial ratios that you can use to manage your new business. (See page 643 for sample financial ratios for ABC Clothing Inc.)

Profitability Ratios

Gross Profit ÷ Sales = Gross Profit Margin

Operating Profit ÷ Sales = Operating Profit Margin

Net Profit ÷ Sales = Net Profit Margin

Net Profit ÷ Owner’s Equity = Return on Equity

Net Profit ÷ Total Assets = Return on Assets

Liquidity Ratios

Current Assets ÷ Current Liabilities = Current Ratio

(Current Assets – Inventory) ÷ Current Liabilities = Quick Ratio

Working Capital ÷ Sales = Working Capital Ratio

Activity Ratios

(Accounts Receivable x 365) ÷ Sales = Accounts Receivable Days

(Inventory x 365) ÷ Cost of Goods Sold = Inventory Days

(Accounts Payable x 365) ÷ Purchases = Accounts Payable Days

Sales ÷ Total Assets = Sales to Assets

Leverage Ratios

Total Liabilities ÷ Owner’s Equity = Debt to Equity

Total Liabilities ÷ Total Assets = Debt Ratio

(Net Income + Depreciation) ÷ Current Maturities of Long-Term Debt = Debt Coverage Ratio

The first step is to set up a plan for the following year on a month-to-month basis. Starting with the first month, establish specific budgeted dollar levels for each category of the budget. The sales numbers will be critical since they will be used to compute gross profit margin and will help determine operating expenses, as well as the accounts receivable and inventory levels necessary to support the business. In determining how much of your product or service you can sell, study the market in which you will operate, your competition, potential demand that you might already have seen, and economic conditions. For cost of goods sold, you will need to calculate the actual costs associated with producing each item on a percentage basis.

For your operating expenses, consider items such as advertising, auto, depreciation, insurance, etc. Then factor in a tax rate based on actual business tax rates that you can obtain from your accountant.

On the balance sheet, break down inventory by category. For instance, a clothing manufacturer has raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods. For inventory, accounts receivable, and accounts payable, you will figure the total amounts based on a projected number of days on hand. (See page 638 for the calculations needed to compute these three key numbers for your budget.)

Figure 39.6. Comparative Financial Ratios

![]() Smarter to Barter?

Smarter to Barter?

Remember how pioneers would trade a deer skin for a musket? It was called bartering. Today, the concept is back in a big way—especially online. The companies are everywhere on the net: itex.com, bbubarter.com, u-exchange.com.

The barter industry is growing rapidly, with barter sales increasing from $40 million in 1991 to more than $20 billion in 2000. The International Reciprocal Trade Association reports that approximately $16 billion in transactions were conducted in North America in 2008, while the U.S. Department of Commerce estimates that 30 percent of worldwide commerce is bartered. Bartering can be an invaluable tool for a startup company.

Bartering can be good for your business in good times, but it can be even better in bad, and, let’s face facts, most startups have their share of downtimes. The main advantage to going the barter route is that if you have unwanted inventory, you can use it to trade rather than spend money you don’t have and pile more onto your already stretched-too-thin budget.

Here’s how bartering works: Let’s say a landscaper needs a root canal. The landscaper belongs to a bartering organization and learns that a local dentist is also part of the same organization. But it turns out the dentist doesn’t need any landscaping done. OK, fine. So the landscaper instead does work for a small public relations firm and a restaurant management consultant. For that work, he has been banking “bartering dollars,” enough to pay for other members’ services, like a dentist, who will then use those bartering dollars to get something from another member. Meanwhile, to belong to a bartering organization, you’re paying a monthly membership fee of $10 to $30.

Who determines what each service or product is worth? You pay the fair market value, which is determined by buyer and seller. But beware: There are some dishonest barterers out there who will charge higher prices to members or not give a service or product that was part of a deal. You need to keep track of bartering purchases and provide clients with Form 1099-B so you can file it on your taxes.

Consider each specific item in fixed assets broken out for real estate, equipment, investments, etc. If your new business requires a franchise fee or copyrights or patents, this will be reflected as an intangible asset.

On the liability side, break down each bank loan separately. Do the same for the stockholders’ equity—common stock, preferred stock, paid-in-capital, treasury stock, and retained earnings.

Do this for each month for the first 12 months. Then prepare the quarter-to-quarter budgets for Years 2 and 3. For the first year’s budget, you will want to consider seasonality factors. For example, most retailers experience heavy sales from October to December. If your business will be highly seasonal, you will have wide-ranging changes in cash-flow needs. For this reason, you will want to consider seasonality in the budget rather than take your annual projected Year 1 sales level and divide by 12.

![]() Where Credit Is Due

Where Credit Is Due

When you book a credit sale in your business, you must collect from the customer to realize your profit. Many a solid business has suffered a severe setback or even been put under by its failure to collect accounts receivable.

It is vital that you stay on top of your A/R if you sell on credit. Here are some tips that will help you maintain high-quality accounts receivable:

![]() Check out references upfront. Find out how your prospective customer has paid other suppliers before selling on credit. Ask for supplier and bank references and follow up on them.

Check out references upfront. Find out how your prospective customer has paid other suppliers before selling on credit. Ask for supplier and bank references and follow up on them.

![]() Set credit limits, and monitor them. Establish credit limits for each customer. Set up a system to regularly compare balances owed and credit limits.

Set credit limits, and monitor them. Establish credit limits for each customer. Set up a system to regularly compare balances owed and credit limits.

![]() Process invoices immediately. Send out invoices as soon as goods are shipped. Falling behind on sending invoices will result in slower collection of accounts receivable, which costs you cash flow.

Process invoices immediately. Send out invoices as soon as goods are shipped. Falling behind on sending invoices will result in slower collection of accounts receivable, which costs you cash flow.

![]() Don’t resell to habitually slow-paying accounts. If you find that a certain customer stays way behind in payment to you, stop selling to that company. Habitual slow pay is a sign of financial instability, and you can ill afford to write off an account.

Don’t resell to habitually slow-paying accounts. If you find that a certain customer stays way behind in payment to you, stop selling to that company. Habitual slow pay is a sign of financial instability, and you can ill afford to write off an account.

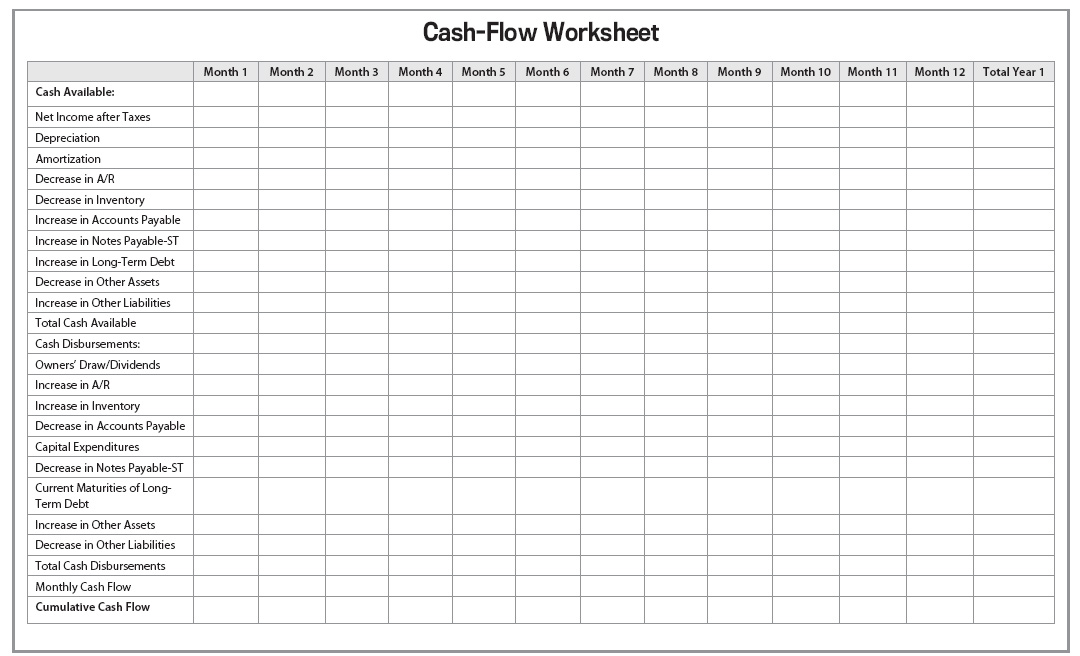

As for the process, you need to prepare the income statement budgets first, then balance sheet, then cash flow. You will need to know the net income figure before you can prepare a pro forma balance sheet, because the profit number must be plugged into retained earnings. And for the cash-flow projection, you will need both income statement and balance sheet numbers.

Whether you budget manually or use software, it is advisable to seek input from your CPA in preparing your initial budget. His or her role will depend on the internal resources available to you and your background in finance. You may want to hire a CPA to prepare the financial plan for you, or you may simply involve him or her in an advisory role. Regardless of the level of involvement, your CPA’s input will prove invaluable in providing an independent review of your short- and long-term financial plan.

In future years, your monthly financial statements and accountant-prepared year-end statements will be very useful in preparing a budget.

Sensitivity Analysis

One other major benefit of maintaining a financial budget is the ability to perform a sensitivity analysis. Once you have a plan in place, you can make adjustments to it to consider the potential effects of certain variables on your operation. All you have to do is plug in the change and see how it affects your company’s financial performance.

Here’s how it works: Let’s say you’ve budgeted a 10 percent sales growth for the coming year. You can easily adjust the sales growth number to 5 percent or 15 percent in the budget to see how it affects your business’s performance. You can perform a sensitivity analysis for any other financial variable as well. The most common items for which sensitivity analysis is done are:

Figure 39.7. Financial Budget and Income Statement Worksheet

Figure 39.8. Balance Sheet Worksheet

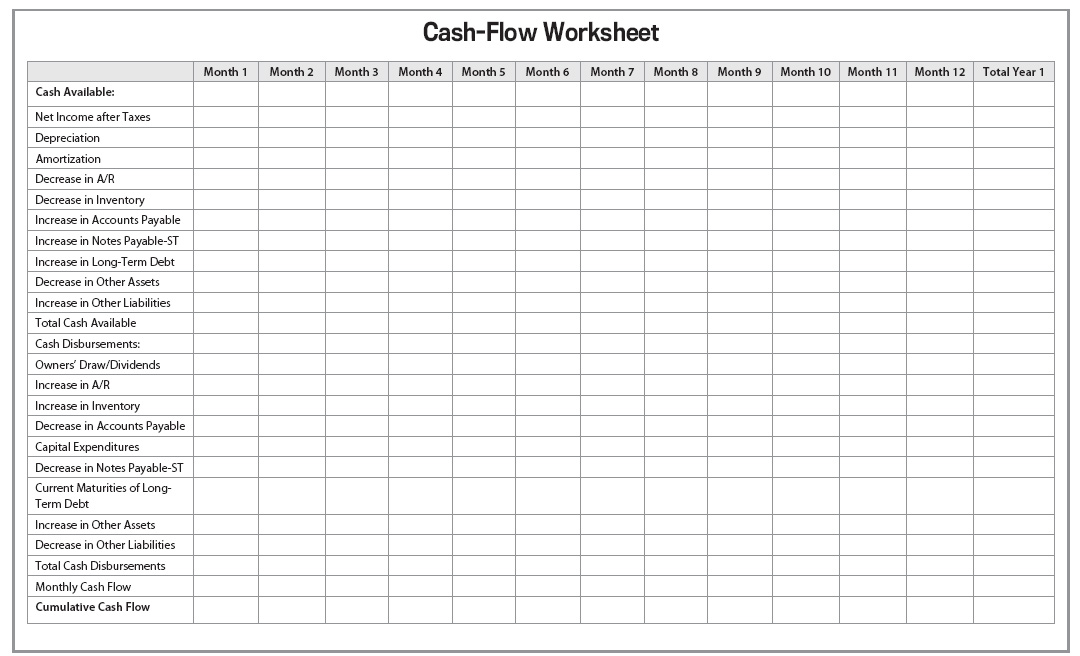

Figure 39.9. Cash Flow Worksheet

![]() Sales

Sales

![]() Cost of goods sold and gross profit

Cost of goods sold and gross profit

![]() Operating expenses

Operating expenses

![]() Interest rates

Interest rates

![]() Accounts receivable days

Accounts receivable days

![]() Inventory days

Inventory days

![]() Accounts payable days on hand

Accounts payable days on hand

![]() Major fixed-asset purchases or reductions

Major fixed-asset purchases or reductions

![]() Acquisitions or closings

Acquisitions or closings