Immature male Black Sicklebill beginning to acquire full adult plumage (detail). Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour.

Immature male Black Sicklebill beginning to acquire full adult plumage (detail). Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour.

Genus Epimachus & Genus Drepanornis

If a contest could be arranged to choose the most beautiful of all the birds of paradise – and the various competitors made to display in all their finery – it would prove virtually impossible to select a true champion. There are so many candidates, and each might lay a legitimate claim to the title. Among the plume birds, those with red plumes, yellow plumes, white or blue might all find supporters. The Superb Bird with its immaculate, soft black feathering and iridescent breast shield is an entirely different, but equally deserving, contender; so too is the exquisite King Bird with its breathtaking red, set off by deep green and pristine white feathers. Other entrants can be selected according to taste.

If, however, the criteria for the contest were to be slightly altered, and the competition became one to select the most spectacular species, there could be only one serious candidate – the adult male Black Sicklebill. With its funereal colouring, its great feather fans and axe-shaped plumes tipped by crescents of metallic-seeming colours, it is a fantastic, almost unreal-looking, creature. As well as the features already described, it has a black tail almost a metre (3 ft) long, speckled with iridescent glosses and sheens of blue and green, a back spangled with similar colours, black lace-like plumes at its flanks, and a long, slender, down-curved beak that seems to counterbalance the pointed tail.

Two male Black Sicklebills and a female. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart and John Gould from Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88).

As might be expected, all this ornamental finery serves a purpose, and is put to extravagant use when the bird performs his display.

When William Hart tried to make sense of the peculiar arrangement of fans and tufts, and imagine how they might be used, he came up with two wonderful images, one for John Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88), and then a second, just a few years later, for Richard Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

As works of perceptive imagination, and as decorative tours de force, they are remarkable, a tribute to the artist’s inventive capability. Sitting in England, thousands of kilometres from New Guinea and any living examples, Hart had only imported, preserved skins for reference – dried and lifeless. So strange and eccentric is the arrangement of the ornamental feathers on the Black Sicklebill that Hart was, in reality, confronted by a mass of virtually indecipherable plumes and structures.

From this unpromising resource, he was required to create convincing images showing the bird’s beauty to the best possible effect, to breathe some kind of life into the meagre materials that he had to hand, and to depict how the feathers might be used in display. The fact that his interpretation is not strictly correct hardly lessens his achievement. Hart probably believed that the positions and attitudes he created were as extreme as any painter would dare to envisage, but, as with other birds of paradise, the fantastical use to which the birds put their feathers is way beyond any reasonable expectation. It is impossible to imagine it, without actually seeing living birds perform.

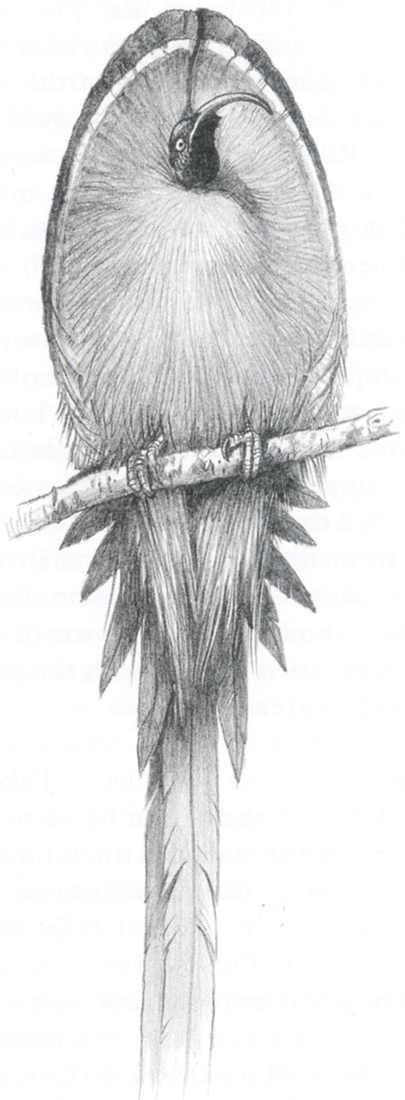

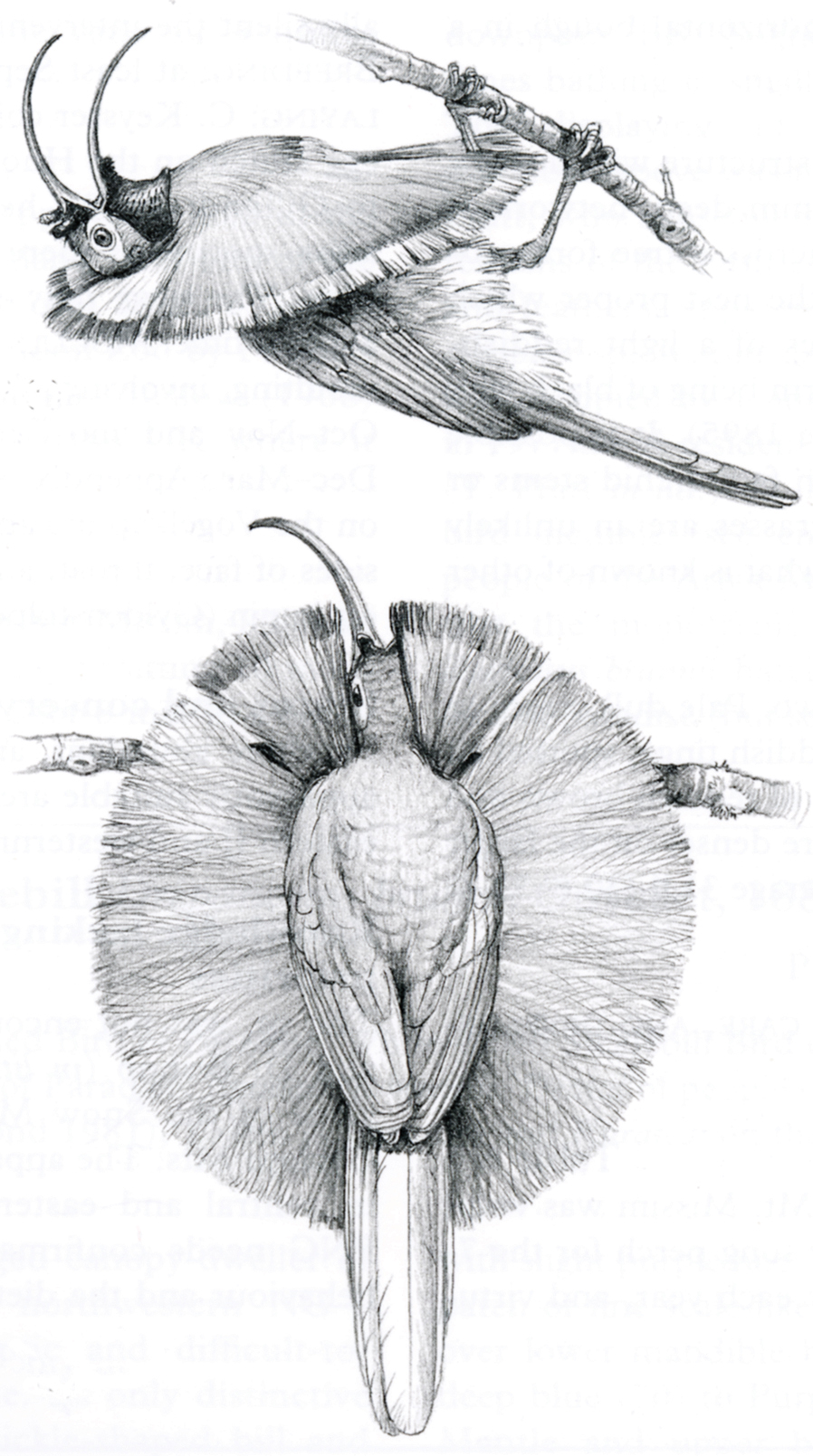

At the height of this display the male bird raises his flank feathers above his head like two great sails or sheets, and for a moment looks like a cartoon ghost from a child’s nightmare – but black not white. Then he continues to raise them until they meet to form a perfect elipse. Lower down, the plumes and feathers shape themselves in such a way that his head (with a wide-open beak) is framed at the centre of a great iridescent-fringed oval. Meanwhile, the extremely long tail hangs straight down. Sometimes he slowly leans to one side and takes up an almost horizontal position, at the same time holding the oval frame around his head and accompanying the whole with a strange, soft rattle.

Two stages in the display of the Brown Sicklebill, a very close relative of the Black. Both species perform in a similar manner.

The climax to the display. Pencil drawing by William Cooper (c.1990).

The plumage of the female is arranged in a much more conventional fashion, but even though comparatively modestly attired, she is a subtly marked and beautiful bird.

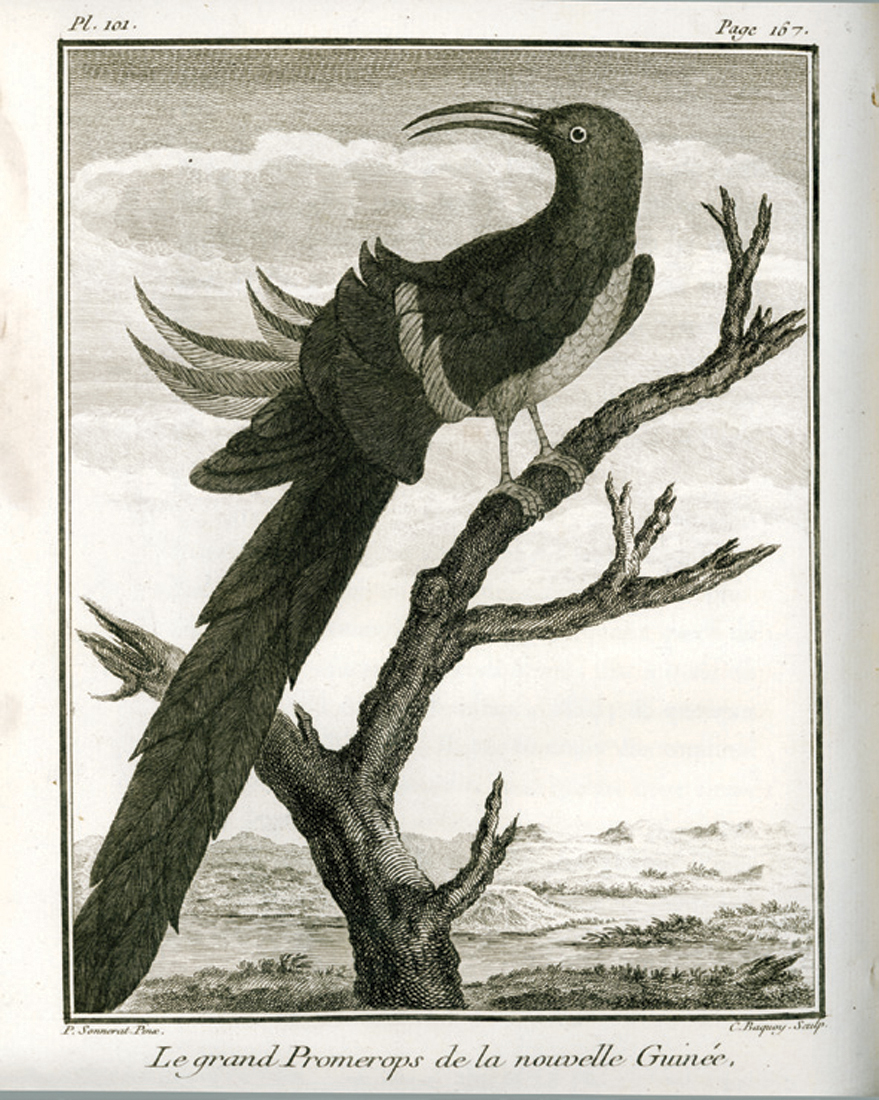

Black Sicklebills are birds of the mountains and as such they didn’t come to the attention of Europeans until well into the eighteenth century. The first mention in western literature is in François Valentijn’s Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien (1724–26), but Valentijn’s comments are extremely brief, and the species wasn’t properly described until considerably later. Eighteenth-and early nineteenth-century naturalists regularly called it a ‘promerops’, a word they used to indicate various groups of unrelated birds that sported long, slender beaks – bee-eaters, hoopoes and sugar birds among them. The Black Sicklebill seemed to fall loosely into this category, and to account for the discrepancy of its comparatively large size it was often called ‘the Great Promerops’. Gradually, however, there was general acceptance that the species was indeed a bird of paradise, and the term promerops is now applied only to the sugarbirds.

Before the end of the eighteenth century the species had been scientifically named Epimachus fastosus – Epimachus referring to its scimitar-shaped bill, fastosus meaning proud – and a fairly comprehensive series of specimens had arrived in Europe. This series included females and immature males, surprising arrivals in view of the fact that it was only the ornately feathered males that were usually collected and traded by Papuan hunters. However this situation came about, there is no doubt that a series of skins was imported into France around the beginning of the nineteenth century, and that at least some of these were skilfully stuffed. The proof lies in several watercolour paintings by Jacques Barraband, who copied the stuffed birds with a delicacy that is breathtaking.

But despite the fact that the species was becoming familiar in Europe via the medium of imported specimens, it would be decades before any European or American could claim to have seen living birds in the wild.

Male Black Sicklebill. Engraving from Pierre Sonnerat’s Voyage à la Nouvelle-Guinée (1776).

When the mountains of New Guinea did at last begin to be explored by intrepid travellers, there came a surprise. The Black Sicklebill had a close, but quite distinct, relative. Living at even higher altitudes, it was slightly smaller, its bill was more slender, and the general colouring of the adult male was brown, not black. Appropriately it became popularly known as the Brown Sicklebill. Discovered by the German collector Carl Hunstein (1843–88) in the mountains of southeast New Guinea during 1884, it was scientifically named Epimachus meyeri in honour of Adolf Bernard Meyer (1840–1911), then Director of the Staatliches Museum für Tierkunde, Dresden, an institution that was busily assembling an important bird collection.

Immature Black Sicklebill beginning to acquire full adult plumage. Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

Male Black Sicklebill. Jacques Barraband. Watercolour, c.1802, 87 × 52 cm (35 in × 21 in). Private collection.

Female Black Sicklebill. Jacques Barraband. Watercolour, c.1802, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

Two display positions of the male Buff-tailed Sicklebill. Pencil drawing by William Cooper (c.1990).

Later, the species was found to live in many high-altitude localities across mainland New Guinea, and these mountainous areas, which made the bird’s domain inaccessible for so many years, still help to preserve it today. Much of the territory it inhabits lies above heights at which land is being turned to agricultural use, and so for the time being the species’ future seems secure. The same cannot be said for the Black Sicklebill which – although a mountain species – lives at altitudes increasingly used for farming; it is now one of the most endangered of all birds of paradise.

But these two species aren’t the only paradise birds with sickle bills. Just a few years before the Brown Sicklebill’s discovery, another species with a long down-curved beak had been found. Although also a mountain dweller with various similarities to its larger relatives, it was sufficiently distinct for ornithologists to put it in a separate genus. The first specimens to reach Europe came from the Arfak Mountains and were sent by the explorer Luigi Maria D’Albertis. The species was named Drepanornis albertisi in his honour – Drepanornis meaning ‘sickle bird’, albertisi after Signor D’Albertis. Its popular name is the Buff-tailed Sicklebill, and it was eventually found to occupy a very fragmented range across the highlands of New Guinea, being entirely absent in many seemingly suitable areas. In display male birds use some of the devices common to several birds of paradise: they raise their flank plumes to make an almost perfect circle around the head and body, and open their mouths wide. But they also hang in a completely inverted position from their chosen display perch.

Soon after the discovery of this species came another surprise. In the coastal lowlands of the more remote parts of northern New Guinea, there lived a relative, the only Sicklebill that is not a mountain dweller. Named Drepanornis bruijnii after a Dutch merchant who first brought the species to attention, it has become known as the Pale-billed Sicklebill; but even today few travellers and naturalists reach its home grounds, and both Drepanornis species remain comparatively little known.

There is one more twist in the story of the Sicklebills. A great mystery surrounds a bird known as Elliot’s Bird of Paradise. It has come to be regarded as a hybrid but its true nature is uncertain, and although the story starts in 1871, it has no satisfactory ending. In the autumn of that year a strange bird skin was received by a London taxidermist named Edwin Ward among a consignment of exotic bird specimens imported from Singapore.

Male and female Brown Sicklebills. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

Male and female Pale-billed Sicklebills. W. T. Cooper, c.1976. Watercolour, 60 cm × 47 cm (24 in × 17 in).

Male and female Buff-tailed Sicklebills. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart and John Gould from Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88).

It was clear that it bore some connection with the only Sicklebill species then known – the Black – but it was smaller in size and showed many plumage differences. The naturalists who saw it were in no doubt. It was a new species that belonged in the same genus as the Black Sicklebill, and it was given the name Epimachus ellioti after the American ornithologist and bird of paradise fanatic Daniel Giraud Elliot. The timing of the specimen’s arrival was fortuitous. It coincided with the weeks during which Elliot was putting the finishing touches to his Monograph of the Paradiseidae, for which Joseph Wolf was providing illustrations with help from his friend and assistant Joseph Smit (1836–1929). At the time of the strange Sicklebill’s arrival Wolf had virtually finished all the pictures needed, but there was just enough time remaining for him to produce an illustration of the new bird, and the resulting plate was included in Elliot’s book.

Wolf’s picture is splendidly decorative but, despite his reputation for accuracy, it is curiously misleading. The satin-like mottling he shows bears little resemblance to the appearance of the actual specimen and it is difficult to understand why Wolf painted in the way he did. Perhaps he simply fell in love with the wonderful image that was developing under his brush and couldn’t bring himself to modify it. But the inaccuracy is a fact that has passed virtually without comment, probably because in all the years of the specimen’s existence very few people have actually seen it.

The preserved skin passed into the hands of John Gould, and his artist William Hart produced a picture for Gould’s Birds of New Guinea. This image is more accurate but, perhaps because it is less spectacular, it has been regarded as inferior.

At Gould’s death the still unique skin was bequeathed to the Natural History Museum, London. Then, a second specimen turned up. Like the first, it lacked locality data, other than a rumour that it might be from northwest New Guinea. During 1890 it was acquired by the industrious Herr Meyer for his wonderful collection in Dresden. A third anomalous specimen, now in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, was subsequently imported, and this may be an immature individual although it has never been acknowledged to be so.

There the matter rested for almost 40 years. No-one questioned the legitimacy of Epimachus ellioti as a species, and it was confidently expected that its home grounds would eventually be discovered in some remote place. As the years passed this possibility receded, and fears were expressed that the species might be extinct.

In 1930 the influential German ornithologist Erwin Stresemann (1889–1972) expressed his belief that the specimens were the result of hybridisation between two familiar species, the Black Sicklebill and the Arfak Astrapia. He lacked conclusive evidence, but such was his reputation that this determination was accepted almost without question. The reputation was certainly well founded, but in this case there are major flaws in his argument. First, the combination of parents he suggested was one he had already used to account for another anomalous form (known as Astrapimachus astrapioides), one that bears convincing marks of both species in its plumage. A second problem with the proposal is that Elliot’s Bird of Paradise is a third smaller than either of its supposed parents, and additionally it bears no real marks that might link it to the Arfak Astrapia.

Elliot’s Bird of Paradise. Hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from G. D. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Elliot’s Bird of Paradise. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart and John Gould from Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88).

Stresemann’s remarks had curious repercussions. Not only was the form dismissed from lists of accepted species and ignored by later researchers, but the original specimen was deemed of such little consequence that experts at the Natural History Museum in London tossed it into a box alongside other apparently worthless specimens with the intention that it should be destroyed. Its survival is down to a stroke of good fortune. No-one at the museum ever got round to carrying the box to the dump! It lay with the trash for many years until a curator by the name of Michael Walters re-located it and saved it for posterity. Whatever its actual status, thanks to Mr Walters this historic relic is now safely under lock and key in the museum’s collection of type specimens.

If the form is indeed a hybrid, there is a more likely pairing than the one selected by Stresemann. Affinity with Sicklebills is evident, so the Black might remain under suspicion, but its partner could have been a Long-tailed Paradigalla (Paradigalla carunculata), one of the species that lacks ornamental plumage. There is a rather distinctive structure to the tail that is reminiscent of a paradigalla, and there are also small facial wattles that might link it to that species.

And there the matter rests. Elliot’s Bird of Paradise may be a species that is now extinct. It may be a bird with a very limited range awaiting rediscovery in some unexplored corner of New Guinea. Or it may be a hybrid. But it is probably not the hybrid that Stresemann believed it to be.

‘Astrapimachus astrapioides’, a hybrid between the Black Sicklebill and the Arfak Astrapia that shows clear features of both parents. Hand-coloured lithograph by Henrik Gronvold from Novitates Zoologicae (1911).