2 The early service music

Kenneth Kreitner

Eight sacred works are attributed to Anchieta in the manuscript Segovia s.s. This is significant enough in itself, if only because it adds three pieces—two unica and one sole attribution—to his worklist, and because he is by far the most often cited Spanish composer there. More important for our deeper understanding of Anchieta’s life and works, Emilio Ros-Fábregas’s recent and persuasive dating of the Segovia manuscript to 1498 and a bit after enables us to say with gratifying security that these eight compositions fall into the first decade or so of his documented career and thus allows us to divide his works broadly into early and not-necessarily-early.1 It is a distinction, however rough-hewn, that at the moment cannot usefully be made for any of his Spanish contemporaries, and it is very welcome indeed in Anchieta’s case.

Of those eight, two are mass movements and three are motets; they will be examined in subsequent chapters. The other three fall into the category of service music, music clearly based on chant and intended to be dropped into slots normally occupied by chant in the liturgy. They make a good place to begin our survey of Anchieta’s works, and they are, despite their sometimes small dimensions and unpretentious appearance, a significant part of his output.

Conditor alme siderum

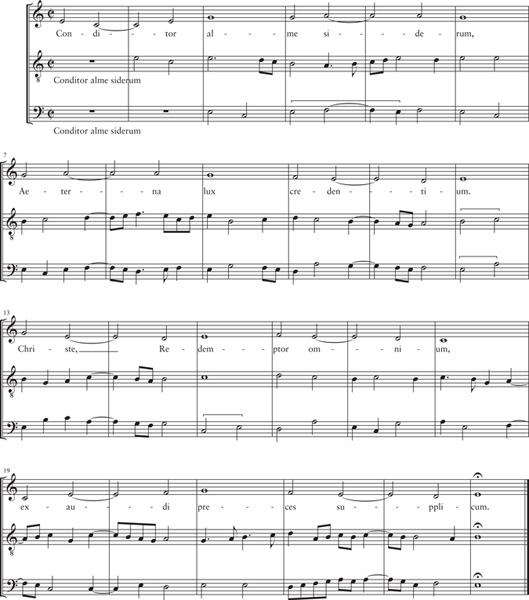

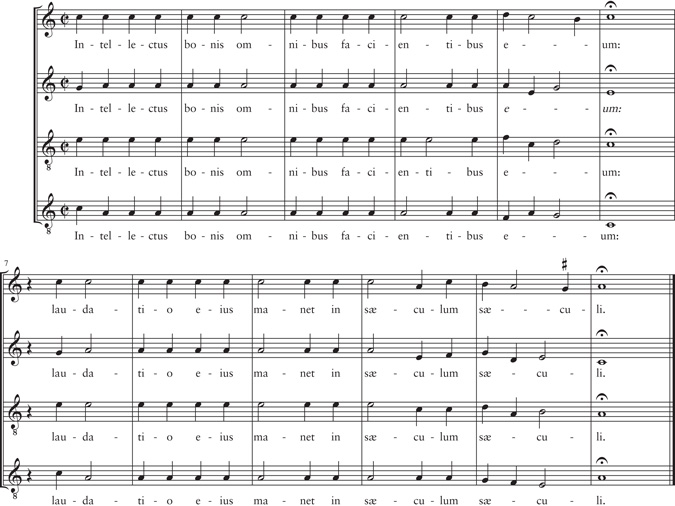

The simplest and shortest of these compositions is the hymn Conditor alme siderum (no. 7 in the worklist, Appendix 1); indeed, at twenty-five bars, it is short enough to include in its entirety (Example 2.1).2

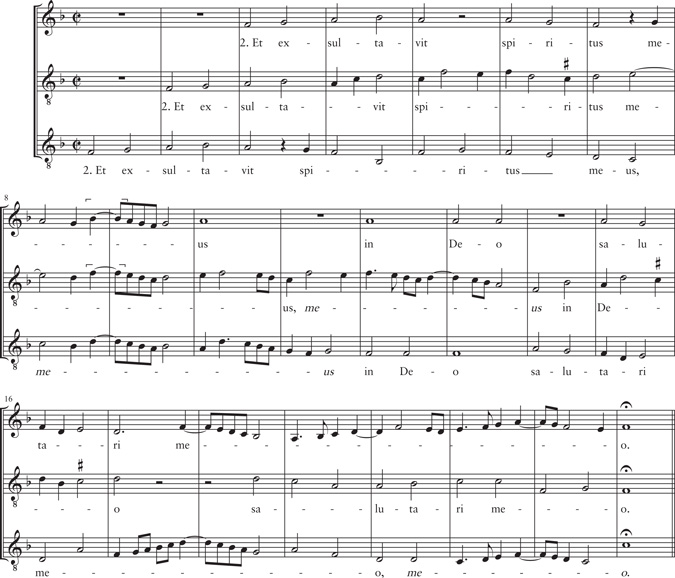

Its basic structure is clear. The first verse of the familiar Advent hymn is put into the superius, in mezzo-soprano clef, in alternating semibreves and breves for a sort of rhythmic mode 2, as in a number of contemporary mensural versions of the chant itself,3 but slow so that every second breve is syncopated over the (modern) barline, confounding the steady duple meter of the accompanying voices. The new accompanying voices, in alto and baritone clefs, move much faster, in minims and semiminims mostly, beginning with a bit of imitation based on the cantus firmus, then moving more or less independently, beholden to each other more than to the chant. At the end of each phrase of the chant (mm. 6, 12, 18), they participate in a momentary cadence, then right away launch themselves into their own next phrase before the cantus firmus resumes.

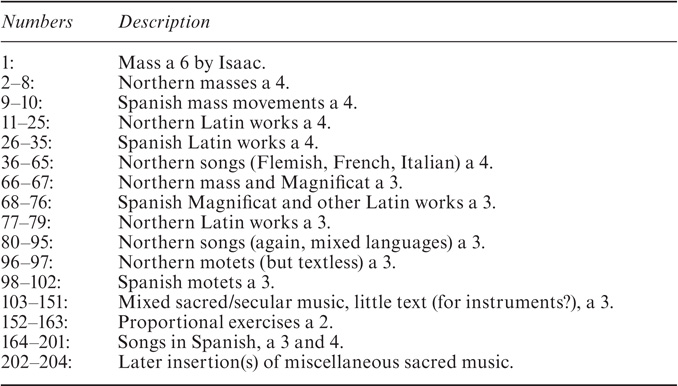

Anchieta’s Conditor alme siderum may be more a tidy piece of craftsmanship than a profound masterpiece. But there is actually a little more to the story than that—which, in turn, invites a slightly longer look at the Segovia manuscript, so central to our understanding of our composer in general. Segovia s.s. is unusual among Spanish Renaissance manuscripts, really among Renaissance sources anywhere, in that it mixes sacred and secular music, northern and local, and a variety of languages. It was clearly not a conventional cathedral manuscript, nor a conventional songbook, and its modest appearance shows that it was intended for practical use, not for presentation; my own belief is that it was copied for a recreational and/or pedagogical situation, at a Spanish court where young people were taught music and used it to amuse themselves.4 It has—at least as it survives, though its first few folios are missing—no tabla or other explicit clue to its organization, but the internal orderliness of the manuscript makes it clear just the same that it was carefully assembled to be easy to get around in: it separates quartets, trios, and duos; northern and local music; Latin and vernacular; mass and non-mass; and Spanish songs and everything else, something like in Table 2.1.5

The northern compositions, by Josquin, Obrecht, Isaac, Brumel, and the like, tend to be carefully attributed, but the Spanish compositions, even some songs by Encina, are almost all anonymous—anonymous, that is, unless they are given to Anchieta. Anchieta gets no fewer than nine attributions, for what prove to be eight compositions (one, as we shall see shortly, seems to be split and attributed twice); otherwise, there are only two others to Spaniards.

Anchieta, in short, is somewhere near the center of this manuscript. Opinions differ as to the exact nature of their relationship,6 but the point for the moment is that whoever put Segovia together evidently knew and respected Anchieta and his music, and that whoever sang and played from it must have grown to see him, much as we see him today (though partly, of course, also because of this one book), as the clear leader among Spanish church musicians in the 1490s. This brings us at last back to folio 169 recto, only the top half of which is occupied by Anchieta’s Conditor alme siderum. The bottom half is given to another setting of Conditor, marked “alius” in the margin and attributed to “Marturia,” who is probably the Catalan organ-builder and abbot Marturià Prats, documented from 1466 (when he was a choirboy; so he must have been born in the 1450s or thereabouts, and thus not far from Anchieta’s age) to 1514.7

Table 2.1 Organization of Segovia s.s

Marturià is a minor composer in surviving output, but not, evidently, in talent: his one other attributed composition, a textless work in Barcelona 5 that probably originated as a motet, is mature and impressive, and it really is a shame that it has lost its words. His Conditor alme siderum (Example 2.2), on the other hand, is much simpler. In fact, it is startlingly similar to Anchieta’s setting above it: their superius parts are identical (and thus perforce exactly the same length) and their lower lines use the same clefs and the same active, playful, meandering style. Marturià’s even begins with a bit of imitation like Anchieta’s.

So why are they both here? If this were a cathedral manuscript, we might suppose that they were copied together for convenience in an alternatim performance; but it isn’t, and in any case both have the same words and not, say, verses 1 and 3. More likely, I think, they are on the page together for a pedagogical purpose, for ease of comparison; certainly, at any rate, they provide a study in craftsmanly imagination, two approaches to the same problem that are broadly similar but different in every detail. Indeed, I have privately wondered whether what we are seeing here is Anchieta himself as a teacher, showing a student (like Prince Juan, though this manuscript itself was evidently copied after his death) how to learn from and parody another composer’s work, and that this is why the two verses evidently traveled together and the one kept Marturià’s name in Segovia s.s.8

Domine non secundum/Domine ne memineris

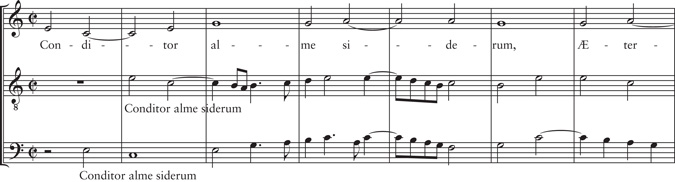

On folio 168v, facing those two hymns, is a three-voice setting, TTB clefs, of Domine non secundum, the first verse of the tract for Ash Wednesday,9 attributed to Anchieta. A four-voice setting, TTTB clefs, of the second verse, beginning Domine ne memineris, is found earlier in the manuscript, on folios 97v–98, also attributed to him; no setting of the third verse, Adjuva nos, is there, nor does any survive anywhere in the Spanish sources from this period.

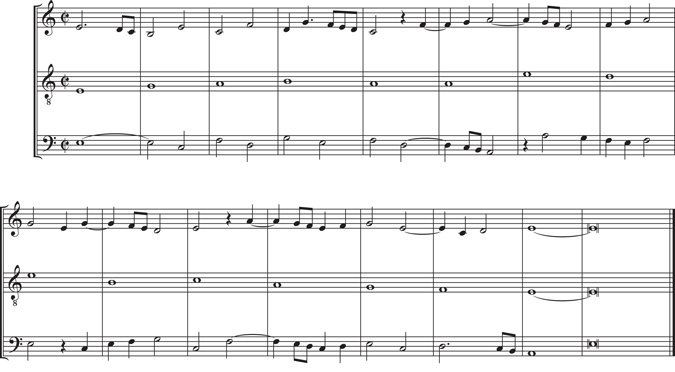

So the first question is whether we have two pieces of music here, or one, or two-thirds of one. My own non-dogmatic answer is that these are two movements of a single work, and that this work is complete (worklist no. 10). Certainly they seem comfortably to belong together: they are stylistically similar, and their unusual cleffing draws them together, and apart from Anchieta’s other works, further.10 And they have a precise analogue in the Domine non secundum of Madrid in Paris 4379, which also sets only the first two verses of the tract, and also with the first a 3 and the second a 4, suggesting that both settings share a Spanish tradition of the 1490s otherwise unseen.11 I believe the movements got separated in Segovia in order to put the one among trios and the other among quartets: another sign, if such be needed, that the manuscript was intended for educational or household use rather than for the liturgy.12 They may well have been sung separately in church sometimes—there was indeed a custom in some Spanish dioceses that split the verses of the tract up and performed them on different days of the week during Lent13—but it seems clear that they were conceived as a pair and make the most sense as a single, self-sufficient unit. The beginning and end (Examples 2.3 and 2.4) will give an idea of the sound of the two sections, and of the whole.14

Domine non secundum is different from Conditor alme siderum in a number of conspicuous ways: for one, it is almost seven times as long, 173 bars total.15 For another, the close voicing, with no high voices at all, and slow pace give it a dark and ascetic sound very distinct from the hymn and well fitted to the solemn and penitential text—at least to our ears today, and apparently to theirs too: for what it may be worth, among the Spanish sacred music in Segovia s.s., only four pieces have top voices in alto or tenor clef, and while one of these is an alleluia, the others are two Lamentations and a setting of O crux ave.16

Like Conditor, Domine non secundum is also a cantus firmus composition, but here the chant is put into the tenor: it is divided into verbal phrases by notes with fermatas (as in m. 13, and as in m. 149, right before the beginning of Example 2.4), and, in general, it is treated quite literally in steady breves at the beginnings of phrases, and paraphrased, with more semibreves and little groups of shorter notes, toward the ends, where the chant tends to have melismas. And the outer voices surround it with a dense soup—becoming bigger and even denser when the fourth voice kicks in—of sonority very different from the playful, improvisatory lower voices of Conditor. There are a few more active spots in the middle, but the general sound is well represented by the examples: a smooth wash of almost-but-not-quite-homophonic harmony, with the other voices moving only a little faster than the tenor and with a noticeable profusion of breves in all the parts. If Conditor alme siderum is a specimen of what I have elsewhere called, as one of my archetypes of late-fifteenth-century Spanish church polyphony, the chant accompaniment, Domine non secundum is, with a few exceptional passages, an example of what I have called smoothed-over homophony.17

What the hymn and the tract do have in common is less obvious, but also significant: they both, at least once a phrase gets going, are very sparing with the rests. The examples here happen to have no rests at all, but that misleads only a bit: in the 240 polyphonic bars of the first verse (eighty bars of music × three voices), there are only 13/4 bars of rest total, and in the 372 of the four-voice section, fewer than twenty, a little over 5%. This too is in keeping with the prevailing church-music styles of the Spanish 1490s, for example in the sacred works of Alonso de Alba, who died in 1504,18 and it gives this music a distinctive and impressive sound, especially when paired, as here, with the close-packed low clefs. It is a kind of music that doesn’t look like much to the eye, especially to the eye primed for the variety and imitative complexity of Josquin or Isaac or Obrecht, but I confess that Domine non secundum carries, in its dark relentlessness, an uncanny power for me, and I find it easy to imagine the electrifying effect it must have had, springing up suddenly in the austerity of the Lenten mass.

Domine non secundum and Conditor alme siderum are the only two compositions of Anchieta’s in Segovia that do not reappear, some decades later, in Tarazona 2/3, and it is reasonable, if speculative, to ask why not. In the case of Conditor, the answer may be purely practical: the Tarazona hymns, arranged together at the beginning of the manuscript in a church-year cycle, are all in four voices, and Anchieta’s hymn is in three.19 (The Tarazona cycle has no hymn for Advent, and none by Anchieta.)

The absence of Domine non secundum has no such obvious explanation. Tarazona 2/3 does not have a section of tracts, nor of any other mass propers except alleluias (which are another coherent cycle, in three voices), but surely it could have been slipped in among the motets, and its penitential character would have fit in well with the many mournful works in that repertory.20 And while its musical style may have seemed unfashionable to write by Tarazona 2/3’s time, that style was clearly still being sung—in fact, the Alba pieces I just compared it to are all to be found in that very manuscript.

It may actually have been a liturgical fashion that was changing: polyphonic settings of this tract remained popular in Rome from the 1490s well into the sixteenth century,21 but Spain may have been different. In addition to Madrid’s setting of the first two verses in Paris 4379—clearly by a Spaniard, even if his exact identity is subject to debate22—there is another setting of the first verse only, with a different ending, in Segovia s.s., in a very homophonic style, and attributed to a mysterious “Ffarer,” whose name could be Hispanic, though the piece itself is in a section of northern music.23 And three polyphonic versions of a particular mass proper is, on reflection, a lot in this context. But none of the major sources that we normally associate with the Peñalosa generation after 1500—not Tarazona 2/3, not Seville 5-5-20, not Tarazona 5, not Toledo 21 (which is full of morose music), not Coimbra 12—contains a single Domine non secundum. There may, in other words, have been little practical use for it by the time Tarazona 2/3 was copied.

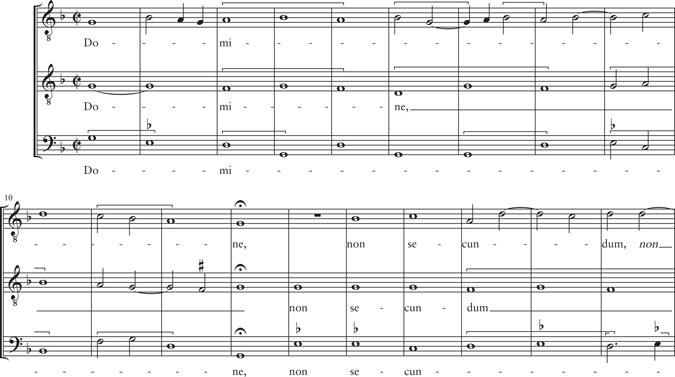

The Magnificat a 3

Anchieta has left two separate settings of the Magnificat. One, in four voices, is preserved only in Tarazona 2/3, and it is probably a later work; we shall return to it in Chapter 6. The other, the Magnificat a 3 (worklist no. 12), is found both in Tarazona 2/3 and in Segovia s.s., so that it must have been written before the turn of the century.24 Like most Magnificats of the era, it sets only the even verses of the canticle in polyphony, leaving the odd verses to be sung in chant. (For comparison, of the fifteen Magnificats in Tarazona 2/3, none sets all twelve and only two set the odd verses.) It is based on a Magnificat tone in F with a reciting tone on A,25 audible mostly, though not always, in the superius. Anchieta puts his three voices in mezzo-soprano, alto, and tenor clefs, for a compact total range of just a half-step more than two octaves. All of this—the three voices, the monotonous model, and the narrow range—would seem to restrict the composer’s options; Anchieta’s response is to make his six verses as different as he can within those external limitations.

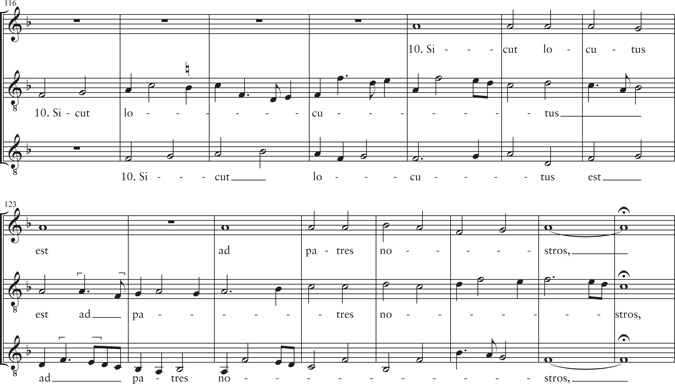

Four of the six verses are divided by a medial fermata, again typical of the earliest layer of Spanish Magnificats;26 verse 10, the first half of which appears as Example 2.5, is perhaps the most traditional, with the F-G-A opening of the chant paraphrased in a little imitation in the tenor and bass, then the rest outlined in whole and half notes in the superius.

This verse is relatively straightforward, with the chant, especially the reciting tone, very clear. Example 2.6 shows, in contrast, the opening verse, in which Anchieta paraphrases the chant more freely, with an imitative beginning and, on the word “meus,” an elegant arch structure in all three voices, of a sort that we shall see often in his later works too. Yet the outlines of the chant are still clearly perceptible in the superius, with a rest (m. 11) substituting for the fermata as in most of the other verses.

This is some of the most artful and skillful counterpoint in the Magnificat a 3, and it registers, to modern ears at least, as Anchieta beginning his canticle with a kind of subtle bang. The middle verses, like verse 10, are more straightforward, and then he ends it with a flashier bang: the first half of verse 12 is a tenor-bass duo—the only duo of more than a couple of bars in the whole work—and the second half is back to three voices and suddenly in triple meter for the first time, for a little notching-up of excitement right at the end.

The Magnificat, sung every day at the end of Vespers, was, of course, a text frequently set to music in the Renaissance—though not so much in Segovia s.s., which has only three others (by Agricola, Josquin, and Brumel). It presents the composer with a different sort of problem from a hymn or tract: you have half a dozen verses to set, each with the same not-particularly-interesting tune, but different in length, so you need to do the same thing six times, similar enough to be recognized as a whole work of art, different enough to accommodate the different words and to distinguish the individual verses, and always with the Magnificat tone more or less audible somewhere. Later in his life, the four-voice Magnificat would show Anchieta as a full member of the Peñalosa generation; in the 1490s, he already brings a considerable level of craft and invention to the task.

Libera me Domine

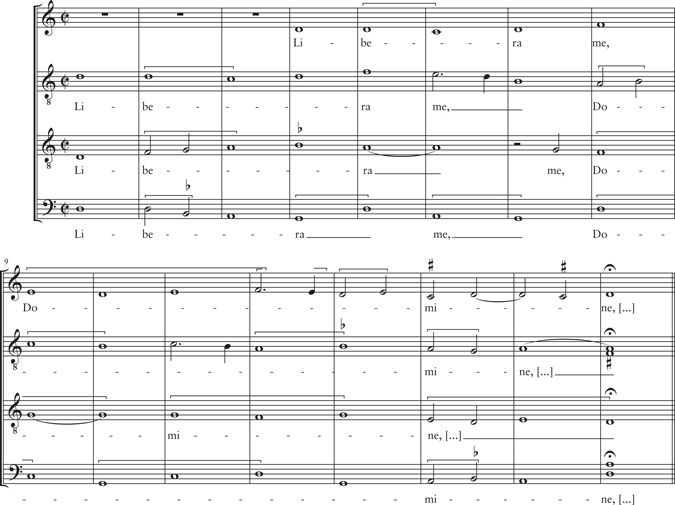

Libera me Domine (worklist no. 11) is a setting of one of the responsories for the dead.27 It survives today in some ten manuscripts, of which three—Tarazona 2/3, Tarazona 5, and Toledo 21—are from near Anchieta’s lifetime. It is anonymous (or nearly so28) in all but Tarazona 2/3, but there seems no good reason to question the attribution in this well-trusted source. In all three of the early manuscripts, and several later ones, it is paired with another responsory for the dead, Ne recorderis, in a setting attributed to Francisco de la Torre, and in Tarazona 2/3 they both follow Pedro de Escobar’s Requiem mass.

You may notice one conspicuous omission here: Libera me does not appear in Segovia s.s.—Ne recorderis does, but in the section added later—so that we cannot say with certainty that it was in existence at the time Segovia was copied. Some years ago, I, among others, suggested that these two responsories and the Escobar Requiem were all written for the funeral of Prince Juan in 1497.29 Part of the reasoning there has been undone by subsequent research, as it emerges that Escobar was not, as we had thought, a member of the Castilian royal chapel at that time;30 however, Anchieta certainly was, indeed was working for the prince himself, and as Tess Knighton has suggested in Chapter 1, Prince Juan’s funeral and its elaborate and widespread ceremonies still seem a likely occasion for the composition of Libera me.31 Certainly its style fits better with the Segovia music than with Anchieta’s later, large-scale sacred works.

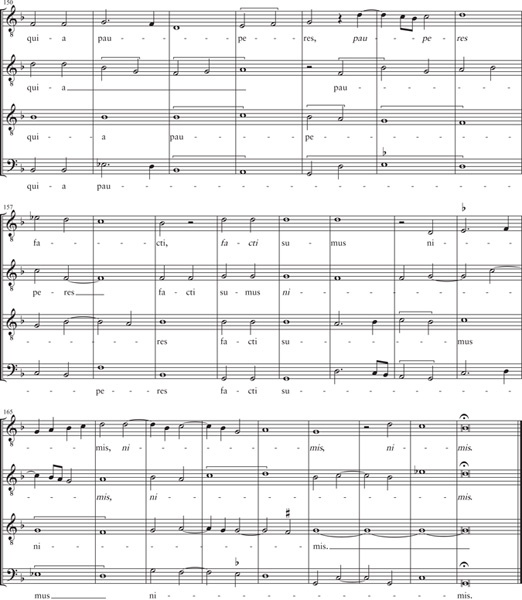

Anchieta’s setting of Libera me was meant for alternatim performance, with short bits of polyphony written to alternate with longer passages of chant. And here is where the case, as Grayson Wagstaff has ably outlined, becomes complicated: the sources do not agree on which parts to include, nor their proper order, and things are further confounded by a system of repetitions that seem to have varied from place to place.32 So it is hard to know exactly what is Anchieta’s work. Fortunately, the version in Tarazona 2/3, which is the one edited by Rubio—indeed, he seems to have seen no other—preserves as many sections of polyphony as any, and the centrality of its source makes it a better specimen than most.

The piece is essentially a harmonization of its chant,33 which appears plainly in the superius, mostly in breves (whole notes in my transcription), and thus does not bear many clear fingerprints from its composer. Example 2.7 presents the first polyphonic period, which is common to all the versions, as a specimen of its dark and blocky sound—yet with little touches like the vorimitation in the alto that suggest a deliberate compositional effort rather than a quasi-improvisation.

For all of the problems it presents, Libera me remains an exceptionally fine example of what service music was about in Spain at the end of the fifteenth century: it was written to fit into and adorn the liturgy for some important funeral, whether of Prince Juan or someone else. It was not meant as a display of compositional skill so much as it was made to be used. And used it was: several of its sources were copied in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and Felipe Rubio Piqueras wrote in 1925 that it was still being sung, “terribly tragic and of an unearthly expression,” in Toledo cathedral on All Soul’s Day and at the funerals of archbishops. “As many times as it is heard,” he goes on, “so many times it reminds us of the fateful moment that approaches us.”34 It may be the one work of Anchieta that has been in someone’s repertory continually from his time to ours.

Some problems of attribution

Anchieta is unusual among Renaissance composers in the number of works that have been ascribed to him, not by his contemporaries or by the generations right after, but by scholars of our own time. These modern attributions are, at the very least, part of Anchieta’s historiography; their effect on the shared public impression of his works (such as it is) is harder to gauge. But clearly some of them are more convincing than others—hence the sections toward the end of certain chapters here entitled “Some Problems of Attribution.”35

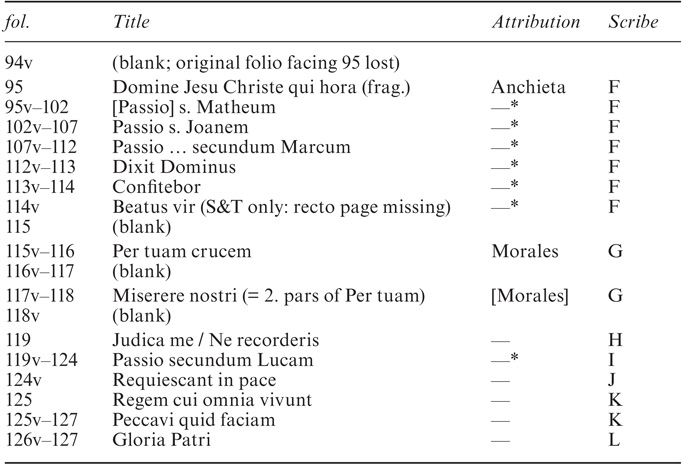

Seven such problems attend the service music, and they are all contained within one source, Valladolid, Parroquia de Santiago, s.s.36 The Valladolid manuscript spans a considerable length of time and was contributed to by many scribes; portions appear to have been assembled piecemeal, sometimes from individual bifolia. A fair amount dates from the early seventeenth century, but some may be older. Table 2.2 below shows an inventory of the broad section that concerns us here.37

Table 2.2 Inventory of Valladolid (Santiago) s.s., ff. 86v–127

As the table shows, most of the music in this section is anonymous; there is one motet attributed, correctly, to Morales and one, correctly, though it is now fragmentary, to Anchieta—his famous Domine Jesu Christe qui hora, of which only the recto page, which fortuitously has the attribution, survives. The seven works with the asterisks are the questions here: in a series of articles and editions, the eminent Spanish scholar Dionisio Preciado has attributed them, too, to Anchieta.38

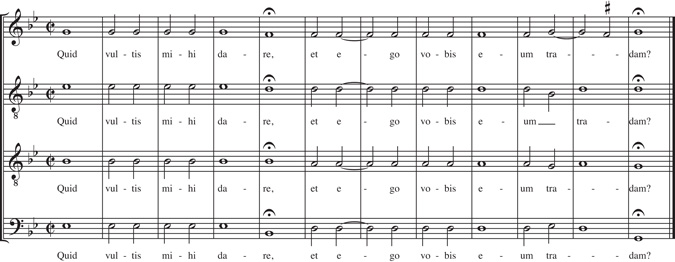

Passions and psalms, though from different testaments, are both made up of short coherent sections, and one of each will suffice to show the nature of both. The Passions work in a way typical for Passion settings of the early Renaissance: the text is taken from the Bible, in Latin, and the roles of the Evangelist (the narration) and Jesus are given to soloists; Preciado includes their monophonic music, from the Passionarium Toletanum of 1516, in his edition. The manuscript, however, gives only the turba portions, the direct speech of others—the disciples, the crowd, Judas, Pilate, and so forth—always in four parts (even for individual characters), in passages ranging from three to sixty-two measures long, but most well under twenty. Example 2.8 shows the third polyphonic section of the Matthew Passion, in which Judas asks, “What will you give me, and I will deliver him unto you?”39

All three of the psalms (numbers 109, 110, and 111 in the Vulgate) give verse 1 in monophony and provide polyphony for verses 4, 7, and 10; for 109 and 111, verse 10 is part of the doxology.40 Example 2.9 shows the last verse of the middle psalm.

I mean these two specimens to do no injustice to the works as a whole. The psalms never get significantly more complicated than this, the Passions only very seldom;41 both of these repertories, in other words, consist almost entirely of harmonized reciting tones leading into elementary cadence structures. The seven compositions are like one another, but they are really nothing like Anchieta’s firmly attested music—which leads us back to the question of their authorship.

Preciado’s contention essentially was that the ascription to Anchieta of the motet Domine Jesu Christe qui hora on folio 95 recto was meant, or sufficed, to identify some of the works after it as well. And while it is true that Domine Jesu Christe, as we shall see in Chapter 3, was a famous motet and is about the crucifixion (or at least its immediate aftermath) and might conceivably make a fitting introduction to a set of Passions, that is about as far as I am willing to go. The leap to supposing that the Matthew, Mark, and John Passions have the same composer is one that I am reluctant to make without corroborating evidence, and the even greater leaps to the psalms and to the Luke Passion (which is separate from the others and has a different scribe) seem even riskier—especially in view of the dissimilarity of the music to anything we know for sure is by Anchieta. They are fascinating pieces of music, if only because they represent kinds of music that were probably sung often back then without attracting much attention today, and we should be grateful for Preciado’s fine editions and commentary. But there is simply no good reason to believe that they are Anchieta’s work, or even from his lifetime.

*********

Service music of this kind does not normally display a Renaissance composer at his most brilliant: its utilitarian origins, as something to snap into a slot normally occupied by chant, usually show, so that in some ways what Anchieta has done in these four pieces seems closer to arranging than to the kind of composition that goes into a mass or a motet. But let me put it more positively than that. What we are seeing in the early service music is Anchieta connecting with, and building onto, something that is much harder to see 500 years later—the culture of improvised polyphony that flourished in the Iberian Peninsula before and during his time.

Improvised music is obviously impossible to capture fully afterward. But in recent years, a number of scholars have chipped away at the edges of this particular mystery to reveal just how important, how widespread, and how sophisticated the practice was in Renaissance Spain, and to draw at least some preliminary outlines of what it was like.42 The treatises and other commentary from this period distinguish three types of sacred polyphony, called fabordón, contrapunto, and canto de órgano:43 the first two are improvised over (or around) a line of chant, fabordón with simple block chords, and contrapunto with more elaborate running lines, faster than the cantus firmus. Canto de órgano, or written polyphony, supposedly follows the same rules as contrapunto, differing only—they say, perhaps a bit disingenuously—in the manner of production. And the treatises go into various levels of detail about how contrapunto was to be done. One of the best is Matheo de Aranda’s Tractado de canto mensurable, published in Lisbon (but in Castilian) in 1535—after Anchieta’s time, but clearly meant to document a practice of long standing. Example 2.10 shows one of Aranda’s three-voice contrapunto examples:44

Such pedagogical specimens must be interpreted with care: this is not, of course, an actual improvisation but a teacher’s ideal of an improvisation of a certain type, meant to make a particular point. But, taken together, Aranda’s discussion and examples45 give a vivid idea of church singers rendering a chant line into steady unchanging breves (he prints the tenor line in black breves, mimicking chant notation46) and improvising quicker lines above and below in a somewhat lick-ridden style, always aware of their intervals and of the rules. That this style of music was actually sung in real life in the 1490s is attested to by a pair of very similar alleluias, both anonymous, that got written down in Segovia s.s.,47 and that this kind of music was sung all over the peninsula, in the courts, the cathedrals, and the parish churches, is shown in a great many ecclesiastical documents; ability to improvise and teach contrapunto was a standard skill specified, for example, in chapelmasters’ contracts.48

Anchieta’s early service music is clearly a step above and away from the tradition as outlined by Aranda, for starters because he tends to paraphrase his chant model rather than put it into only breves, and because he prefers to put it in the superius, not the tenor. This is canto de órgano, to be sure; but notice that in Conditor alme siderum he does use a rigid cantus firmus, and that in Domine non secundum and Libera me he is still at pains to evoke the fundamental sound of improvised contrapunto by keeping his cantus firmi mostly in breves and paraphrasing them more toward the ends of phrases than at their beginnings. It is useful, I believe, to think of these three works—and Marturià’s hymn, and a number of the anonymi in Segovia and elsewhere—as unmissing links between the more or less hidden improvised traditions of fifteenth-century Spanish churches and the written polyphonic repertory that was already starting to take shape in the 1490s. A more modern approach to polyphony can be seen in the three-voice Magnificat, with its freer treatment of its chant tone, and in the motets and mass movements that were being written around the same time—as the next chapters will show.

Anchieta’s early service music may not be our favorite music of his today. But it represents a solid connection with the tradition he inherited, and a firm step into the future he would help create. This is music that is, in the end, well worth signing one’s name to: at least some of it would be sung well into the sixteenth century, and at least Libera me would be sung for centuries beyond. But all that said, these early liturgical settings are strikingly different from the motets in Segovia s.s., both in terms of function and compositional approach.

Notes

1 On the dating of Segovia s.s., see Emilio Ros-Fábregas, “Manuscripts of Polyphony from the Time of Isabel and Ferdinand,” in Tess Knighton, ed., Companion to Music in the Age of the Catholic Monarchs (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 404–68, especially 429–42, and at 435, and idem, “New Light on the Segovia Manuscript: Watermarks, Foliation and Ownership,” in Wolfgang Fuhrmann and Cristina Urchueguía, eds., The Segovia Manuscript: A Spanish Music Manuscript of c. 1500 (Woodbridge: Boydell, forthcoming). The book as a whole offers a much richer understanding of many aspects of this important source. My own previous chapters on Anchieta and the music of Segovia s.s., Chapters 6 and 7 of Kenneth Kreitner, The Church Music of Fifteenth-Century Spain, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Music 2 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2004), supposed a somewhat earlier date and proposed that Segovia was copied for Prince Juan, who died in 1497 (see Chapter 1 above). This obviously must be modified somewhat in view of Ros-Fábregas’s subsequent work.

2 It was also published in Samuel Rubio, ed., Juan de Anchieta: Opera Omnia (Guipuzcoa: Caja de Ahorros Provincial de Guipuzcoa, 1980), 107–08. See also Kreitner, Church Music, 106.

3 The hymn also appears in a number of more or less contemporaneous peninsular chant sources in mensural notation: see, for example, Bruno Turner, Toledo Hymns: The Melodies of the Office Hymns of the Intonarium Toletanum of 1515: A Commentary and Edition (Marvig: Mapa Mundi, 2011), p. 21, no. ITHM 001. The Intonarium’s reading is almost identical to Anchieta’s, even keeping the A on the seventh note (“-de-” in m. 5), differing only in the eighteenth note (“-su” in mm. 13–14), where it has an F-E ligature instead of the long E. On the performance of Spanish mensural hymns generally, see idem, “Spanish Liturgical Hymns: A Matter of Time,” Early Music 23 (1995): 473–82. The hymn, in unmeasured notation and with the text beginning Creator alme siderum, may be found on pp. 324–26 of the Liber Usualis.

4 I expand on this idea further in Kenneth Kreitner, “What Was Segovia For?,” forthcoming in Fuhrmann and Urchueguía, The Segovia Manuscript.

5 This table is contracted and simplified from one in ibid. Item numbers are taken from the classic and still standard inventory of Segovia in Higinio Anglés, ed., La música en la Corte de los Reyes Católicos, I: Polifonía religiosa, Monumentos de la Música Española 1 (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1941, 2/1960), hereafter abbreviated MME 1, 106–12, which, however, evidently counts the anonymous In passione positus as the secunda pars of Anchieta’s Virgo et mater (no. 27 in the inventory). It is a matter of legitimate debate—see Chapter 3, for more—but if In passione is indeed a separate piece, then it should be number 28, and all subsequent compositions should be renumbered. For convenience and clarity, however, we have decided to stick with the MME 1 inventory in our references here, and to call In passione number 27bis.

6 See the various essays in Fuhrmann and Urchueguía, The Segovia Manuscript, for current debate. The classic early study of the manuscript, Norma Klein Baker, “An Unnumbered Manuscript of Polyphony in the Archives of the Cathedral of Segovia: Its Provenance and History,” 2 vols. (PhD diss., University of Maryland, 1978), still offers a great deal to think about and includes a good many editions not otherwise available.

7 For biographical information on Marturià Prats, see especially Tess Knighton, Música y músicos en la corte de Fernando el Católico, 1474–1516 (Zaragoza: Institución “Fernando el Católico,” 2001), 336; Richard Sherr, “The Roman Connection: The Spanish Nation in the Papal Chapel, 1492–1521,” in Tess Knighton, ed., Companion to Music, 364–403 at 367 and 401, Ros-Fábregas, “Manuscripts of Polyphony,” at 443–44; and Francesc Villanueva, “Una perspectiva prosopogràfica del oficis musicals de la Catedral de València en temps de Guillem de Podio, 1480–1505,” Anuario Musical 72 (2017): 9–50.

8 See also Kreitner, Church Music, 83–84, for a somewhat longer specimen, lined up vertically against Anchieta’s setting. The whole hymn is edited in Baker, “Unnumbered Manuscript,” II: 966–68. Anchieta and Marturià may have actually met when Prince Juan and his parents visited Barcelona in 1493; see Antonio Rumeu de Armas, Itinerario de los Reyes Católicos, 1474–1516 (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1974), 203–06.

9 Liber Usualis, 527–28.

10 They are, in fact, his only secure sacred music with a top voice in a clef other than soprano or mezzo-soprano.

11 So far as I know, there is no published edition of Madrid’s piece; see Kreitner, Church Music, 56–58, for an excerpt and my previous commentary. This tradition has recently been explored by David Burn in a paper, “The Anatomy of Chant-Based Polyphony around 1500,” read at the conference “The Anatomy of Polyphonic Music around 1500” (Cascais, June–July 2018); I am grateful to Dr. Burn for sending me a copy of the paper in advance of publication.

12 Rubio, in Anchieta: Opera Omnia, 83–86 and 87–92, edits them as separate pieces, but says in his notes (p. 39) that “Estas dos piezas, no obstante encontrarse separadas in el manuscrito que las transmite, deben ser consideradas como una.”

13 Robert J. Snow, A New-World Collection of Polyphony for Holy Week and the Salve Service, Monuments of Renaissance Music 9 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 35–38.

14 The edition is my own, after Segovia s.s. The manuscript, particularly in the three-voice section, has a number of errors, which are silently corrected here.

15 My figure counts a number of internal longs at the ends of phrases, which are treated as final longs, as one measure and not two.

16 These are no. 31 (O crux ave, ARTB), 72 (Alleluia, TTR), 74 (Aleph: Quomodo obscuratum, TRB), and 75 (Aleph, Viae Sion lugent, TRB).

17 Kreitner, Church Music, 156 et passim.

18 Kenneth Kreitner, “The Music of Alonso de Alba,” Revista de Musicología 37 (2014): 19–51, and since then, Burn, “Anatomy of Chant-Based Polyphony.”

19 On this group, see especially Rudolf Gerber, “Spanische Hymnensätze um 1500,” Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 10 (1953): 165–84; idem, Spanisches Hymnar um 1500, Das Chorwerk 60 (Wolfenbüttel: Möseler, 1957), which edits them all; and Juan Ruiz Jiménez, “Infunde amorem cordibus: An Early 16th-Century Polyphonic Hymn Cycle from Seville,” Early Music 33 (2005): 619–38.

20 See, for example, Howard Mayer Brown, “Música para la pasión de Cristo de Anchieta y otros: Música española hacia 1500 en un concierto pan-europeo,” in III Semana de Música Española “El Renacimiento” (Madrid: Festival de Otoño de la Comunidad de Madrid, 1988), 223–48; and Kenneth Kreitner, “Spain Discovers the Motet,” in Thomas Schmidt-Beste, ed., The Motet around 1500: On the Relationship of Imitation and Text Treatment? (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012), 455–71.

21 See Richard Sherr, “Illibata Dei virgo nutrix and Josquin’s Roman Style,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 41 (1988): 434–64, especially the Appendix, “Domine, non secundum peccata and a Roman Motet Tradition,” pp. 455–62; Warren Drake, ed., Ottaviano Petrucci: Motetti de passione, de cruce, de sacramento, de Beata Virgine et huiusmodi B, Monuments of Renaissance Music 11 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 43–45; and Jesse Rodin, Josquin in Rome (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), especially 272–75 and 293–305.

22 Kreitner, Church Music, 56–60.

23 It is edited by Baker in “Unnumbered Manuscript,” II: 789–97.

24 It is edited in Rubio, Anchieta: Opera Omnia, 109–19, under the title Magnificat [Sexti toni], after Tarazona 2/3 but with good notes to the variants in Segovia; my examples here are edited from the earlier source. See also Kreitner, Church Music, 115–16.

25 Rubio supplies chant for the odd verses, but does not explain his source: it appears to combine the first-mode Magnificat tone (Liber Usualis, 207) for the first half-verse, and the sixth-mode one (ibid., 211) for the second. This does admittedly correspond to what Anchieta seems to be using, though the chant is paraphrased too much to be absolutely sure. Indeed, the whole question of local traditions in liturgical chant is a matter of urgent concern for future scholars; throughout this volume, we shall use the Liber as our standard reference, and where there seem to be substantial differences with the known Spanish chant melodies, we shall note them, but at the moment the situation is too fluid and chaotic to make more than the most rudimentary connections.

26 Kenneth Kreitner, “Two Early Morales Magnificat Settings,” in Owen Rees and Bernadette Nelson, eds., Cristóbal de Morales: Sources, Influences, Reception, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Music 6 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007), 21–61, at 29.

27 It is edited by Rubio in Anchieta: Opera Omnia, 93–101, after Tarazona 2/3. The best account of this piece, to date, is George Grayson Wagstaff, “Music for the Dead: Polyphonic Settings of the Officium and Missa pro defunctis by Spanish and Latin American Composers before 1630” (Ph.D. diss., University of Texas, 1995), Chapter 4, especially pp. 160–75, whence almost all my historical data here are derived.

28 Actually it is given by the tabla to Toledo 21 to Francisco de la Torre, but as Wagstaff, in ibid., 165–66, points out, this is a very plausible error, since its predecessor in the source, Torre’s Ne recorderis, is labeled on the page with Torre’s name in a prominent banner, while Libera me has nothing. In Tarazona 5, it is also anonymous on the page, but two sixteenth-century inventories of the cathedral’s music collection give it to Anchieta and Josquin, for reasons now obscure: see Pedro Calahorra, “Los fondos musicales en el siglo XVI de la Catedral de Tarazona: I. Inventarios,” Nassarre 8 (1992): 9–56 at 28, item 309.

29 Kreitner, Church Music, 142–48.

30 Francesc Villanueva Serrano, “La identificación de Pedro de Escobar con Pedro de Porto: Una revisión a la luz de nuevos datos,” Revista de Musicología 34 (2011): 37–58. Also, since the publication of my book, Juan Ruiz Jiménez has made a strong case that the Escobar Requiem was written for, or at least according to the customs of, the cathedral of Seville: see especially Juan Ruiz Jiménez, La librería de canto de órgano: Creación y pervivencia del repertorio del Renacimiento en la actividad musical de la catedral de Sevilla (Granada: Junta de Andalucía, 2007), 37–38, 281–83; and idem, “‘The Sounds of the Hollow Mountain’: Musical Tradition and Innovation in Seville Cathedral in the Early Renaissance,” Early Music History 29 (2010): 189–239, at 233–34.

31 See also Tess Knighton, “Music for the Dead: An Early Sixteenth-Century Anonymous Requiem,” in Tess Knighton and Bernadette Nelson, eds., Pure Gold: Golden Age Sacred Music in the Iberian World: A Homage to Bruno Turner (Kassel: Reichenberger, 2011), 262–90, at 280–86.

32 Wagstaff, “Music for the Dead,” 167–72.

33 Compare Liber Usualis, 1767–68. As Wagstaff points out, Anchieta’s original is evidently similar but not quite identical to the version in the modern Roman publications.

34 F. Rubio Piqueras, Códices polifónicos toledanos: Estudio crítico de los mismos con motivo del VII centenario de la catedral primada (Toledo: Medina, 1925), 44, also quoted in Wagstaff, “Music for the Dead,” 163–64: “terriblemente trágico y de un expresivismo ultraterreno; cuantas veces se escucha, otras tantas nos habla del más allá fatídico que se nos acerca. Se ejecuta en los funerales de los Arzobispos y en el día de finados. Muchos atribuyen a Morales la paternidad de esta obra, pero no le corresponde no hay sino ver el Códice para saber que es de Francisco de la Torre.” In this last observation, Rubio is, of course, mistaken, fooled by the attribution (in Toledo 21, subject of this entry, but see above at note. 28) of Ne recorderis; it is significant, however, that the work is well respected enough to be mistaken for Morales.

35 We are especially indebted here to Eve Esteve and her willingness to share her paper, “Works for the Office by Juan de Anchieta,” read at the 2012 Medieval and Renaissance Music Conference (Nottingham, July 2012), and for her kind permission to use it in advance of publication.

36 Its Census-Catalogue siglum is VallaP s.s.; this is not to be confused with VallaC s.s., at the cathedral, also an important source for Morales.

37 On this manuscript, sometimes called the Diego Sánchez codex after the name of a scribe signed at the beginning and dated 1616, or the Santiago codex after the name of the parish church, see especially Juan Bautista Elústiza and Gonzalo Castrillo Hernández, in Antología musical: Siglo de oro de la música litúrgica de España: Polifonía vocal, siglos XV y XVI (Barcelona: Rafael Casulleras, 1933), xix–xxiv; Pedro Aizpurua, “El códice musical de la parroquia de Santiago de Valladolid,” Revista de Musicología 4 (1981): 51–59; and most recently Nuria Torres, “The Santiago Codex of Valladolid: Origins, Contents and Dating,” Fontes Artis Musicae 61 (2014): 173–90. My table is based in part on her table on pp. 184–87. I am grateful to Dr. Torres for sending me not only an advance copy of the article, but a copy of her master’s thesis, Nuria Torres Lobo, “El códice de Santiago de Valladolid” (Master’s thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2012), and her photographs of the folios in question, and for a long and fruitful correspondence on this source, which she has seen and I have not.

38 Dionisio Preciado, “Las pasiones polifónicas del códice musical de Valladolid son de Juan de Anchieta, y las primeras completas conocidas en España,” Nassarre 8 (1992): 57–68; Dionisio Preciado and Pedro Aizpurúa, eds., Juan de Anchieta (c.1462–1523): Cuatro Pasiones polifónicas (Madrid: Sociedad Española de Musicología, 1995), with an edition of all four passions; and Dioniso Preciado, “Juan de Anchieta (c.1462–1523) y los salmos del Códice Musical de la Parroquia de Santiago de Valladolid (CMV),” in David Crawford and G. Grayson Wagstaff, eds., Encomium Musicae: Essays in Memory of Robert J. Snow (Hillsdale: Pendragon, 2002), 209–29, with an edition of all three psalms.

39 Matthew 26:15, Douay-Rheims translation. Because of the limited ranges, the manuscript provides two flats for the altus and bassus voices, only an E-flat for the superius, and only a B-flat for the tenor.

40 In the case of Beatus vir, the page with the altus and bassus lines is lost; they are reconstructed by Preciado in “Anchieta y los salmos,” 226–29.

41 For example, in the passage beginning “Domine memento mei,” from the St. Luke Passion, edited by Preciado in Anchieta: Cuatro Pasiones, 255–56.

42 The most comprehensive overview of this subject known to me is Giuseppe Fiorentino, “Unwritten Music and Oral Traditions at the Time of Ferdinand and Isabel,” in Tess Knighton, ed., Companion to Music (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 504–48. See also idem, “Folía”: El origen de los esquemas armónicos entre tradición oral y transmisión escrita (Kassel: Reichenberger, 2013), Chapters 8–9; Santiago Galán Gómez, “La teoría de canto de órgano y contrapunto en el Renacimiento español: la Sumula de canto de organo de Domingo Marcos Durán como modelo” (PhD diss., Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2014); and Stephen Rice, “Aspects of Counterpoint Theory in the Tractado de canto mensurable (1535) of Matheo de Aranda,” in M. Jennifer Bloxam, Gioia Filocamo, and Leofranc Holford-Strevens, eds., “Uno gentile et subtile ingenio”: Studies in Renaissance Music in Honour of Bonnie J. Blackburn (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009), 63–73.

43 All of these terms have common but misleading cognates in modern musical terminology: they do not quite correspond to fauxbourdon, counterpoint, or organum.

44 Matheo de Aranda, Tractado de canto mensurable: y con contrapuncto [etc.] (Lisbon: Galhard, 1535), facsimile downloaded from IMSLP.org (19 December 2014). The book itself is unpaginated; my example is from p. 42 of a 71-page pdf. See also Fiorentino, “Unwritten Music and Oral Traditions,” 520.

45 For more transcriptions, see Rice, “Aspects of Counterpoint,” 68 and 72, and Fiorentino, “Unwritten Music and Oral Traditions,” 520–21.

46 Some others are actually in black semibreves.

47 Kreitner, Church Music, 94–95; they are edited by Baker in “Unnumbered Manuscript,” II: 872–77 and 878–86. See also Fiorentino, “Unwritten Music and Oral Traditions,” 522.

48 Fiorentino discusses several of these in ibid.