1 The life of Juan de Anchieta

Tess Knighton

The present attempt to piece together Anchieta’s life, and the place of his extant works within it, draws as much as possible on primary documentary source material, from payment documents to correspondence by the composer as well as royal ambassadors and members of the royal family he served, and accounts by contemporary chroniclers. Inevitably, this documentation is incomplete, and the correspondence contingent on political and social realities and circumstances that are often difficult to read accurately after so many centuries. Wherever possible, the main aim has been to contextualize the primary sources that refer directly in some way to Anchieta through a wider selection of contemporaneous documentary material relating to the institutions where the composer worked, in order to provide as “thick” a description as possible of the composer’s biography (see Appendix 2 for details of his itinerary while in royal service).1 The subsidiary aim to make the account as coherent as possible, despite the inevitable gaps in documentation—or indeed because of them—may well prove illusory; hopefully, one day, further information will come to light to elucidate those areas that are still in shadow.

Not all Anchieta’s colleagues in the royal chapels were able to acquire as much wealth, status, and travel experience as the Basque composer, though many facets of his life would have been shared by them or at least been familiar to them. The demands made by the itinerant nature of court life, the search for financial security and social standing through obtaining ecclesiastical benefices, preferably in one’s home town or region, and the difficulties that almost inevitably ensued, can be seen as paradigmatic for a singer-composer of his time. Anchieta’s professional status as a musician could hardly have been higher, but he appears to have made little impact on the international musical stage, which gives rise to important questions about the European integration of musicians born in Spain and the distinctive qualities of the music they composed. Yet, if he was indeed the composer of the motet O bone Jesu, attributed in a printed source to Loyset Compère, at least one of his surviving works entered the mainstream and was taken for a composition by a Franco-Netherlandish composer. Other works may have traveled beyond the Pyrenees anonymously, as will be discussed in Chapter 3. He was one of the relatively few Spanish composers of his time to have traveled extensively outside the Iberian Peninsula, and one of the very few to have been represented in the main section of the Segovia manuscript alongside his Franco-Netherlandish contemporaries. On a personal level, Anchieta owned property (an impressive house built in the mudéjar style that still stands in his native Azpeitia), fathered an illegitimate son even though he was a priest, and strove to secure eternal salvation through the endowment of various masses. He was, in other words, a man of his time, as well as an extraordinarily gifted musician. His surviving works are relatively few and surely represent only a fraction of his output; several manuscripts that assuredly contained works by him have been lost. This is his story.

Anchieta’s date of birth and early years (1450s?–1489)

Most biographers of Anchieta have agreed that he was born around 1462, although no incontrovertible documentary evidence for this has yet been found.2 The date of 1462 was proposed by Adolphe Coster based on the belief that Anchieta’s parents were Martín García de Anchieta and Urtayzaga, a member of the Loyola family, who died in 1464.3 However, Anchieta’s more recent biographer, Juan Plazaola, has pointed out that this identification of the composer’s mother is erroneous, and that she was, in fact, María Veraizas (Verayças) de Loyola.4 María Veraizas de Loyola was the sister of Ignatius of Loyola’s grandfather, making Anchieta the future saint’s first cousin once removed. Juan had an elder brother, Pedro García de Anchieta, who, Coster assumed, based on Urtayzaga’s supposed marriage to Anchieta’s father in 1460, was born in c1461, and a younger sister, María López de Anchieta, born c1463. Both Juan’s siblings play a part in his later career and legacy, as does his close relative St. Ignatius of Loyola, born of a different generation in October 1491. The date of marriage of Anchieta’s parents is not now known, and so the composer’s date of birth is thrown open, and may go back closer to the middle of the fifteenth century,5 which would perhaps sit more easily with the reference to him as being old and unable to reside at court in Charles V’s royal cédula of 15 August 1519 (see later in the chapter). “Old” being a relative term, this is hardly conclusive, though it would make better sense if he was older than the age of fifty-seven posited by Stevenson on the basis of a birth date of c1462.6 The exact place of Anchieta’s birth is also undocumented, but is believed to have been at the Anchieta family solar in Urrestilla in the valley of the river Urola near Azpeitia, in the historical region of Guipúzcoa and the present-day Basque Country.7 Ignatius de Loyola was born only a few kilometers away in 1491. Intermarriage between the Anchieta and Loyola families, as in the case of Anchieta’s parents, had helped to diminish the age-old feuds and rivalries between them,8 although certainly not completely, as will be discussed later.

If Anchieta can be assumed to have been born in the 1450s, he could well have been over thirty when he entered the Castilian royal chapel on 6 February 1489.9 This would seem a reasonable assumption, since he would have had to have achieved sufficient skill and experience as a musician to warrant this prestigious royal appointment, but it should be emphasized that even this supposition remains speculative. It would seem likely that he had already been ordained as a priest by this time since he served as “capellán y cantor.”10 However, nothing is known about how he was trained as a musician. Anglés—and almost every biographer since—assumed that, the style of Anchieta’s music being decidedly “Spanish,” he must have been taught by Spanish musicians.11 Certainly, there is no evidence that he studied outside the Iberian Peninsula, as did, for example, the composer Juan de Cornago, who traveled to Paris to study law,12 but North European musicians were quite commonly to be found working in Spanish cathedrals and courts in the fifteenth century and their polyphonic repertory circulated there.13 Anchieta’s music shows awareness of the international Franco-Netherlandish repertory—both sacred and secular14—notably in those works included in the Segovia manuscript (c1498), before he traveled to Flanders. His sojourn there and subsequent period of employment in Queen Juana’s chapel alongside Franco-Netherlandish composers such as Pierre de La Rue, Alexander Agricola, and Marbrianus de Orto would have brought him into direct contact with their music. It is nevertheless true that his surviving works reflect specifically Spanish traditions of composition.

It would thus seem likely that he was trained in the cathedral milieu of the Spanish kingdoms, as were so many of his colleagues in the royal chapels. Suggestions as regards his musical training have included entry as a choirboy in Pamplona cathedral,15 the see to which the small town Azpeitia belonged to in the fifteenth century. However, Anchieta’s name has not as yet come to light in the surviving documentation of Pamplona cathedral, nor can the period of study at Salamanca University, or even the training in the royal chapels, both suggested by Coster,16 be substantiated.17 Likewise, Anchieta’s name has not been found, to date, among the musicians in the service of Enrique IV’s chapel.18 Anchieta’s musical training, wherever it took place—cathedral or chapel—would have followed well-established lines: he would have been taught plainchant (and memorized a large body of chants), polyphony and the art of contrapunto, or improvisation through adding vocal parts to a given melody, whether plainchant or song, according to established rules.19 Anchieta would presumably have served in a cathedral or chapel as a singer, and perhaps risen to the position of cantor or chapelmaster, before being employed in the Castilian royal chapel.

Anchieta’s entry and service in the Castilian royal chapel (1489–1495)

Anchieta was appointed a chaplain and singer at the end of the Catholic Monarchs’ sojourn of several months in Valladolid (Appendix 3a); on 7 February 1489, the day after his formal appointment, the court moved on to nearby Medina del Campo, en route for Córdoba and the continuation of the reconquest of the kingdom of Granada.20 It was common practice for royal singers to be recruited from institutions local to the place where the monarchs stayed as part of the dynamic of the itinerant existence of the royal households,21 so that an early connection with Valladolid should not be ruled out. It is also possible that Anchieta deliberately traveled to that city, where the court had been based since September 1488, to seek employment there. Following his appointment, in the spring of 1489, Anchieta would have journeyed with the queen’s royal entourage to southern Spain, and specifically to the encampment outside Baza, where he surely composed the romance En memoria d’Alixandre to mark the embassy of the Sultan Beyazid II (1447/8–1512).22 This four-voice ballad—which will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 5—is Anchieta’s earliest (and probably his only) datable work and shows that he was an accomplished composer at the time he entered royal service; he must have quickly assumed the role of an official court composer.

The details of Anchieta’s years in the service of the Castilian royal chapel until Isabel’s death in 1504 are well established, and reiterated by every biographer following Barbieri’s introduction to the Palace Songbook of 1890; the following summary brings together all the information gathered from the royal archives to date. Initially, Anchieta was paid an annual salary, as chaplain and singer, of 20,000 maravedís (in the Castilian royal chapel, this corresponded to 8,000 maravedís as a chaplain, and 12,000 maravedís as a singer); he also received an annual clothing allowance (vistuario) of 5,000 maravedís. He clearly rose rapidly in esteem in the Castilian royal chapel, his salary increasing to 25,000 maravedís in 1492 (with a yearly clothing allowance of 6,000 maravedís), and to 30,000 maravedís a year later, in August 1493.23 In 1496, while in the service of Prince Juan, he was due to be paid 35,000 maravedís (although this amount had still not been paid three years later). Other amounts paid to the singer-composer as “favors he has received” (see Appendix 3a) included 8,000 maravedís for his annual clothing allowance and additional sums from the prince’s household on becoming his music master (15,000 maravedís in 1495, and 25,000 maravedís in 1496). Since Anchieta apparently continued to receive 30,000 maravedís for his service in the queen’s chapel, he was earning up to 55,000 maravedís before the prince died in 1497, far more than other royal singers. Non-specified payments were also made: 12,250 maravedís in 1493, and 10,000 maravedís in 1498.24 The treasurers of the royal household indicated that between the years 1491 and 1498, he received through royal favor (mercedes) a total of 66,000 maravedís, a substantial amount.

It might be tempting to see these extra payments as relating to rewards for specific compositions, particularly that for 1493, around the time when he might have composed the Missa Ea judíos a enfardelar attributed to him by Francisco Salinas, following the expulsion of the Jews by the Catholic Monarchs the previous year. Salinas claimed that the song “was commonly sung when the Jews were expelled by the Spaniards” (“quæ cum ab Hispanis Iudæi fuerunt exterminati, vulgò canebatur”), and that “Juan de Anchieta, who was not un-famous in his own day, composed a mass on this tune” (“Ad cuius thema missam Ioannes Ancheta tunc non in celebris symphoneta composuit”). It would be very helpful to know if this work was indeed commissioned by Ferdinand and Isabel from Anchieta, but Salinas was writing much later in the sixteenth century (his De musica was published in 1577), and no other evidence for the existence of the work has yet come to light: it is quite possible that Salinas was mistaken about its existence and/or authorship (see Chapter 4).25 In any case, it is more likely that the sum of 25,000 maravedís, which was divided between Anchieta and the Chantre de Alcalá in 1493, related to their role as receivers (receptores) or treasurers of the royal chapel.26 Certainly, two further payments in 1493 made by the queen’s personal treasurer, Gonzalo de Baeza (see Appendix 3b),27 can be identified as monies distributed among the royal chaplains for serving on special feast days: thirteen gold ducats (4,875 maravedís) for Epiphany, and 8,000 maravedís for those who celebrated the liturgical hours during Lent. The role of receptor was a responsible one, the designated chaplain (or chaplains) being elected for the period of a year, during which time he (they) would have to reside constantly with the court. Anchieta must have fulfilled the role successfully in addition to his musical duties, and come to the notice of the head chaplain (capellán mayor), and thus probably to the queen herself, as, only two years later, he was appointed chapelmaster to the heir to the throne, Prince Juan.

In the service of the heir to the throne (1495–1497)

In his will, Anchieta described himself as having been chapelmaster (“maestro de capilla”) to Prince Juan, and, interestingly, the post-mortem inventory of his possessions includes a royal provision that served as a kind of appointment certificate (“and other documents that the said Abbot [Anchieta] had as chapelmaster and the annual amounts he received in that position as specified in the provisions”) (Appendixes 3g and 3i).28 Although the document mentioned by Anchieta in his will does not appear to survive, his appointment as chapelmaster to Prince Juan is generally given as 1495; certainly he was paid for serving in the prince’s household from that year.29 The prince turned sixteen in 1495, and his own independent household was established;30 the following year, his parents set about bestowing titles and lands on him: Prince of Asturias and Prince of Girona, as well as Lord of Salamanca, Toro, Logroño, Ronda, Loja, and other towns.31 In 1496, the prince was granted his own residence at the castle of Almazán, a small town conveniently situated between Castile and Aragon.32 In the summer of 1496, the monarchs, with the heir to the throne, spent three months in Almazán in the palace of the Mendoza family, and the prince remained there until his wedding to Margaret of Austria in Burgos the following year. In Almazán, he continued his studies with his tutor fray Diego de Deza, and, among other pastimes, played chess,33 as well as developing his twin passions for hunting and music. In his Libro de la Cámara del Príncipe don Juan, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo (1478–1555) provides a description of the personnel who made up the prince’s household and noble company in accordance with his royal status as heir to the throne, and summarizes his princely accomplishments: “And in truth his Highness [Prince Juan] was much given to music and hunting and he was very knowledgeable in all things related to them.”34 This followed closely the recommendations for princely pastimes described in detail by the humanist Rodrigo Sánchez de Arévalo in his Vergel de los príncipes (1454), commissioned by Juan’s half-uncle, Enrique IV.35 Music was, however, barely mentioned in the more serious-minded Diálogo sobre la educación del príncipe don Juan, believed to have been commissioned by Isabel from Alonso Ortiz in the early 1490s.36

When Anchieta joined the prince’s household, the employment of musicians and a high degree of musical activity were already established.37 From 1490, a number of instrumentalists were assigned to the prince in the Castilian royal household by the queen, who, according to long-standing tradition, was responsible for the entourage and education of the royal children.38 At least four trumpeters were employed to herald the prince’s presence, including the black trumpeter Alfonso de Valdenebro.39 From 1490, a singer-player by the name of Juan Bernal (tañedor e cantor) was paid in the prince’s household, together with a small group of instrumentalists that included a rebec-player, Juan de Madrid (who was specifically mentioned by Fernández de Oviedo), the vihuelist Pedro García, the dulzaina-player Jaime Rejón, the tambourine-player Pedro de Narbona, and the organist Juan Rodíguez de Brihuega.40 It is not clear whether the organist played in both chamber and chapel, but it would seem likely. Apart from a number of chaplains, about four chapel boys (moços de capilla) were also employed in the prince’s chapel from 1490: Martín de Valdés, Johan Vásquez, Antonio de Andino, and Francisco de León, with the expected turnover of personnel in the years to 1497.41 These boys were probably also trained by Anchieta in the singing of polyphony, as will be discussed later.

The structure and etiquette of Prince Juan’s household, in which Anchieta played no small part, is brought to life in detail and with extraordinary vividness by Fernández de Oviedo, who served the prince as a page (moço de camara) from about 1491 until the prince’s untimely death in 1497. In about 1535, Fernández de Oviedo was, commissioned by Charles V to write a detailed eyewitness account of Prince Juan’s household to serve as a model for the Castilian-style casa he aimed to establish for his own heir, Prince Philip.42 The result, which Fernández de Oviedo worked and reworked over a number of years, was finally completed in 1548, with the full title of Libro de la cámara real del príncipe D. Juan e officios de su casa e servicio ordinario. Fernández de Oviedo was fortunately for music historians, a rather prolix writer who loved a good anecdote and some serious name-dropping, and he added the concluding section headed “Minstrels and various musicians” (“Menestriles e diversos músicos”) on the rather whimsical premise that his account might not end like a tragedy (“por que no sea tragedia”) in the light of the young prince’s tragic death. This section provides an invaluable insight into the prince’s passion for music, and into Anchieta’s working environment in the mid-1490s (see Appendix 3c). Although this passage has been cited in both Spanish and English translation on several occasions,43 it is worth presenting in full here for its unusually detailed eyewitness description.

My Lord Prince Juan was naturally inclined to music and he understood it very well, although his voice was not as good, to all intents and purposes, as he was persistent in singing; but it would pass with other voices. His chapelmaster was Juan de Anchieta, who taught him in the art, and he established the custom that during the siesta, especially in summer, the said Juan would go to the palace with five or six boys from his Highness’s chapel, skilled boys with fine voices, among whom was Corral, who later became an excellent singer and tiple, and the prince sang with them for two hours, or however long he pleased to, and he took the tenor, and was very skilful in the art.

In his chambers he had a claviorgan, the first ever seen in Spain, and it was made by a great master of Moorish origin from Zaragoza in Aragon, called Moferrez, whom I knew; and he had organs, and harpsichords, and plucked and bowed vihuelas and recorders, and he knew how to play and handle all these instruments.

He had musicians who played the tambourine, and the psaltery and dulzainas, and a harp, a very pretty small rebec that was played by one Madrid, from Carabanchel, a village near Madrid, who was a weaver. And as if in jest, music called him, I mean he took to the rebec and without being shown how to play it, he became an excellent player of that instrument and became rich serving His Highness.

The prince had very fine minstrels: sackbuts, shawms, cornetts, and trumpets, four or five pairs of drums, and for each of these types of instrument, very skilful musicians were employed in his household, as should be the case in the service of such a noble prince.

Although this passage might appear to be a conventional panegyric to the prince’s love for music, Fernández de Oviedo’s not exactly complimentary comment about the prince’s singing voice lends a high degree of verisimilitude,44 and as Bonnie Blackburn has noted, the writer was himself musically trained.45 More importantly, almost all the details provided by Fernández de Oviedo can be verified from court records: Anchieta was employed as the prince’s chapelmaster from at least 1495; musicians—including choirboys, singers, minstrels, and instrumentalists—were employed in his household from at least 1490; a boy singer by the name of Antonio de Corral subsequently served as a singer in the Castilian royal chapel from January 1499, and, following Isabel’s death toward the end of 1504, in the Aragonese royal chapel, and was rewarded with many ecclesiastical benefices by the monarchs.46 A rebec-player called Juan de Madrid, from Carabanchel, also served the prince and was highly rewarded,47 and the monarchs commissioned at least one claviorgan from the keyboard-maker Mahoma Mofferiz of Zaragoza.48

This accuracy of detail in the names of musicians who served the prince, and some of the instruments in his chamber, suggests that Fernández de Oviedo’s account of the summer afternoons spent singing polyphonic songs also accurately reflects an established practice at Prince Juan’s palace in Almazán. This description evokes a characteristic fifteenth-century a cappella musical ensemble of a small number of choirboys on the top line (or tiple), and one voice per part on the lower vocal lines (Prince Juan on tenor and Anchieta on contra).49 Clearly, the many three-voice songs composed by musicians serving in the royal chapels, including Anchieta, and now preserved in the Palace Songbook, would have been particularly suitable for these occasions. The somewhat derogatory comments on the quality of the prince’s voice are not incompatible with his apparent skill in singing the tenor part. Possibly, Prince Juan sang an existing melody in the tenor while the other voices improvised around it.50 It has generally been assumed that, in addition, Anchieta taught the prince to play a number of the instruments listed in his chambers,51 although it is perhaps more likely that such instruction would have been undertaken by the various instrumentalists employed in his household. There is one small indication, however, that Anchieta may have played the organ: he would seem to have had an organ in his house in Azpeitia. An inventory of the parish church of Azpeitia dated 1 August 1530 refers to “the organ that was in poor condition in the house that belonged to Juan de Anchieta, formerly abbot of Arbas, that was there, according to the inventory taken at the time [1529].”52

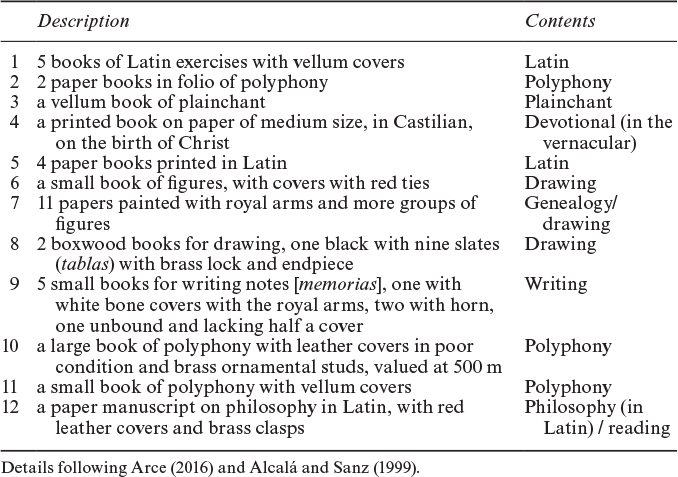

The prince was presumably taught mensural notation by Anchieta, and written musical materials can be associated with him. Inventoried among Isabel’s possessions after her death were several items she had kept, presumably out of a mother’s sentiment, from the time of her son’s education, including a number of books and scholarly exercises (see Table 1.1).

Books purchased on behalf of the prince for his education included a pre-Nebrija Arte de gramática, a volume of St. Isidore, an illuminated “libro de horas de nuestra señora” (bought in 1487), Lorenzo Valla’s Elegantia linguae latinae (bought in 1489), the commentaries of St. Thomas (bought in 1493), and the copy of Aristotle’s Éticas copied by the prince’s scribe, Francisco Flores.53 Flores copied several richly illuminated books for the prince, as well as, in 1490, the Cartujano—Ludolph of Saxony’s Meditaciones vita Christi—which was supplemented by the prayers of St. Bonaventure acquired two years later. The high profile of these devotional books is of considerable importance as regards the type of motet text chosen by Anchieta (see Chapter 3).

Table 1.1 Books and notebooks used in Prince Juan’s education according to an inventory drawn up at Arévalo in 1505

As regards the music books, the prince appears to have had at least four books of polyphony and one of plainchant among those of his possessions that passed back to his mother at the time of his death. Unfortunately, these books do not survive, and the inventory descriptions are too generic to allow for interpretation of their contents: possibly the folio-size books contained sacred polyphony, and the small book was dedicated to songs. Some of these books were sold in Arévalo in 1505 following Isabel’s death:

Five folders of Latin exercises from when the prince was learning Latin, with vellum covers, and two paper books in folio of polyphony and another of plainchant on vellum, and a book of medium-sized paper, printed in the vernacular which begins “the first book telling the birth of Our Lord,” and four small books, printed on paper, in Latin, the first beginning “Que peritabiun [sic] nominis,” of four and a half gatherings (pliegos), which are not worth anything. The folders and exercise books were valued at 3 reales.

[Marginal note:] the books of polyphony were sold to Arnao de Velasco for 3 reales.54

The marginal note in the inventory indicates that the prince’s music books were sold to Arnao de Velasco, son of the contador mayor of the Castilian household.

In addition to Fernández de Oviedo’s anecdotal descriptions of musical activity in the prince’s chambers, the payments for music and musicians recorded in the accounts of Isabel’s personal treasurer, Gonzalo de Baeza, and the various post-mortem inventories, contemporary chronicles and verse allude to the ubiquitous presence of music and musicians at events such as Prince Juan’s marriage to Margaret of Austria in Burgos on 4 April 1497.55 There can be no doubt that Anchieta was present at the wedding celebrations, and it would be surprising if he made no contribution to them. Possibly, this was the occasion for which he composed the Missa sine nomine in which he cites L’homme armé, the emblematic melody so closely associated with the Habsburg dynasty, in the Agnus Dei.56 Juan del Encina certainly made a major contribution to the couple’s spectacular entry into Salamanca in September, presenting his eclogue Triunfo de amor with its concluding villancico Ojos garços ha la niña, surely intended as a paean to the princess’s beautiful eyes.57

Juan’s early death in October 1497 brought an end to the intense musical activity of his court, although music was to form an important part of the prolonged exequies, begun in Salamanca and continued with the transfer of the prince’s body for burial in the monastery of St. Thomas in Ávila on 16 and 17 October.58 Contemporary descriptions of the exequies mention the singing of responsories at certain key moments of the ceremony, and Anchieta may well have composed his setting of the responsory for the dead Libera me, Domine in this context. Polyphonic settings of the responsories for the dead were a specific feature of the exequies of members of the royal family and high-ranking clergymen in Spain,59 and while it cannot be proved that Anchieta’s Libera me, Domine and Francisco de la Torre’s Ne recorderis were composed for Prince Juan’s funeral, the political significance and depth of sentiment occasioned by the loss of the heir to the throne would have demanded the added solemnity of polyphony at his funeral. Polyphony is known to have been sung during the exequies of Ferdinand’s father, Juan II of Aragon, in 1479, and at the funeral of Cardinal Mendoza in Toledo cathedral in 1495.60 Anchieta’s setting of Libera me became part of the musical canon of royal and other funerals that involved the performance of polyphony (see Chapter 2).

It has long been supposed that the earliest Spanish polyphonic setting of the Requiem mass was composed for Prince Juan’s exequies, since Pedro de Escobar, the composer to whom it is attributed in its only surviving source, was thought to have worked in the Castilian royal chapel at the time. However, recent research has shown this not to have been the case, and it has been suggested that the Requiem mass should be more closely associated with Seville cathedral, where Escobar is known to have worked between 1507 and 1514.61 Escobar’s whereabouts in 1497 are now unknown, but it is still possible that his Requiem was performed for exequies held for the prince in some part of the peninsula. The outpouring of grief that spread throughout the kingdoms on receipt of the terrible news seems to have reached an unprecedented intensity, and it is interesting that in various towns and cities, polyphonic music formed part of the exequies held in cathedrals and churches. For example, three singers are known to have been employed expressly for the exequies held for the prince in the collegiate church in Daroca.62 Prince Juan’s death resulted in an extraordinary outpouring of elegiac literature and music. Encina’s romance Triste España sin ventura (Palacio, ff. 55v–56), and related villancico A tal pérdida tan triste (Palacio, f. 224v), were performed at the end of his Tragedia trobada, a sustained lament occasioned by the prince’s untimely death.63 Among many other examples, the court poet Comendador Román also produced his Décimas sobre el fallecimiento del príncipe nuestro señor.64 In death, as in life, Prince Juan was surrounded by music and verse produced by court poets and musicians, and Anchieta bore witness to it all. Whether he composed any other work for the event is not known; elsewhere, I have suggested that he may have composed a lament for the composer Alexander Agricola, who died in Spain in the early autumn of 1506 (see later in the chapter).65

In the service of queens and princesses (1497–1504)

After Juan’s death, Anchieta continued to be paid in the Castilian royal chapel until Queen Isabel’s death in 1504, and subsequently he served the prince’s sister Juana. However, it has not been sufficiently emphasized that immediately after Prince Juan’s death, he continued in the service of Margaret of Austria during her two-year sojourn in Spain.66 Anchieta’s later correspondence with Margaret, dating from 1516 (discussed later), reveals that he considered himself to have been her chapelmaster while she remained in Spain.67 The double matrimonial contract between Maximilian I and the Catholic Monarchs had seen Juana set sail for Flanders in the autumn of 1496 to marry Philip the Fair, while Anchieta was still in her brother’s service. The fleet returned in the spring of 1497 with Margaret, who traveled with her own household, although which, if any, musicians were in her retinue is unknown. After Juan’s death, the pregnant Margaret remained in Spain. All hopes were pinned on the possibility of an heir to the throne, but the monarchs’ grief was to be compounded when, in early December 1497, their granddaughter was stillborn. Margaret stayed in Spain before returning by sea to Flanders in the autumn of 1499, chaperoned by the monarchs’ close advisor, the then Bishop of Córdoba, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca. During this time, Anchieta served as Margaret’s chapelmaster, together with at least one other musician from the Castilian royal household in her service: Bernaldino de Vozmediano.68 According to Fernández de Oviedo, Vozmediano was one of the choirboys who sang with Prince Juan, and he was paid as a mozo de capilla in the Aragonese royal chapel from 1492.69 Vozmediano was officially appointed as a singer in the Castilian royal chapel on 15 September 1498, although he was paid for the two years, from 1497 to 1499 “por quanto los dos años antes siruio a la Prinçesa doña Margaryta, e le fueron pagados.”70 His salary was 20,000 maravedís as “capellán y cantor,” and Fernández de Oviedo described him as a “contralto” during his time in the service of Prince Juan. A few years later, on 12 July 1501, Vozmediano was appointed quartermaster (aposentador) for the Castilian royal chapel, for which he was paid an extra 10,000 maravedís a year; he was also paid 3,870 maravedís on 22 April 1501 “for expenses incurred with some messengers from Flanders” (“de gastos que hizo con unos mensajeros venidos de Flandes”)—so, he seems to have maintained some Flemish contacts. As will be mentioned later in the chapter, Vozmediano also served as Anchieta’s proxy on at least one occasion, and the two musicians thus clearly knew one another.

It is not known what other musicians originally in the service of Prince Juan might have served Margaret during her sojourn in Spain, initially in Almazán and later with the royal court in Granada, but it can perhaps be assumed that at least some of them did. In an inventory of her possessions dating from the time of her departure from Spain, a printed book of French dances is listed among other books given to her by her mother-in-law (“de molde, en francés, libro de danças”).71 This direct connection between Anchieta, Prince Juan, and Margaret of Austria while she was in Spain from 1497 to 1499—both princess and her chapelmaster would have been in the Alhambra in Granada in the summer of 1499—may well prove significant for at least some of the Franco-Netherlandish repertory included in the Segovia manuscript, which was compiled around this time.72 The repertory by Franco-Netherlandish composers such as Ockeghem, Obrecht, Tinctoris, Agricola, Josquin, and others might well have traveled from Flanders with Margaret, and been transmitted by a Spanish musician such as Anchieta closely associated with the Burgundian court repertory, although recent hypotheses about the compilation of the manuscript itself have tended to distance it from royal circles.73

Reward by ecclesiastical benefice

Anchieta’s correspondence with Margaret of Austria in 1516 concerned an abbacy in Guipúzcoa (see Appendix 3e), and this raises another important aspect of Anchieta’s court career before—and after—he traveled to Flanders, and of the system of reward and patronage in the royal chapels: royal presentation to ecclesiastical benefices. This form of reward, well established by the fifteenth century, was mutually beneficial to royal patron and servant alike, and undoubtedly helped to secure the services of the best singers to increase the prestige of the princely chapel.74 Many such royal presentations fell foul of the residency requirements of the relevant church authorities and were often contested over a number of years, by no means always resolving in favor of the royal chaplain or chapel singer, who quite often accepted another, less-contested benefice in exchange. Ferdinand and Isabel—through their ambassadors in Rome—vied with other princes to secure the right to presentation so that they could reward the members of their chapels in this way. However, in this matter, they had a notable advantage over princely rivals: according to laws established by Alfonso X, the monarchy held the right of patronage to benefices established in cathedrals or parish churches built in previously Muslim-held territories, a right for which they sought papal recognition in the form of an indult that officially renewed this concession.75 Lucas Marineus Siculus, royal chaplain, historian, and teacher of Latin to the members of the royal chapels, describes how members of those institutions would ensure they were at court at the time these presentations were made and how the king tended to grant more benefices to those who had already obtained one through royal presentation.76

Anchieta was one of many members of the royal chapels to benefit from the indult granted by Alexander VI in 1492 following the completion of the Granadine campaigns; that same year, on 28 May, he was presented with a canonry in the newly founded cathedral of Granada.77 These canonries were valued at 40,000 maravedís per annum,78 but no value is listed in the summary of royal favors granted to Anchieta up to 1498 (see Appendix 3a), suggesting that he had not been confirmed in the position, or at least had not received monies from it, by that time. However, in the document of presentation to another benefice in the diocese of Salamanca, dating from 12 June 1499, Anchieta is addressed as “canonico Ecclesiae Granatensis,”79 which would indicate that he must have secured the canonry not long afterward. Stevenson, following the biography put together by Uriarte for Barbieri in 1884, suggests that Anchieta was appointed in about 1497 to this canonry without requirement of residency, and held it for about two years;80 yet, there is no subsequent mention of the title in connection with Anchieta, and he was probably forced to renounce the canonry, perhaps in return for another benefice (such as that of Villarino), within a relatively short space of time.81 The devout and assiduous first Archbishop of Granada, Hernando de Talavera, although previously a royal confessor and closely allied with the monarchs,82 was not easily swayed when it came to royal presentations: he refused to accept the singer of the Castilian royal chapel Pedro Ruiz de Velasco as a prebendary in Granada cathedral on the grounds that he was “a child and knew very little”; when Antonio de Corral—Prince Juan’s choirboy with the pretty voice—was presented by the queen, shortly before her death, to a canonry in Almería cathedral, the king subsequently persuaded him to exchange it for another benefice, which yielded him 12,000 maravedís per annum, so that the singer might remain in royal service.83

It is thus clear that even royal presentation to an ecclesiastical benefice could not ensure that the post—nor its income—was attained, and the battles between cathedral chapters and the monarchs over the non-residence of royal chaplains and chapel singers were legion and protracted.84 Under Alexander VI’s second indult of 1494, Anchieta was also presented to a canonry at Ávila Cathedral, as well as to the first simple benefice to fall vacant in the town and diocese of Osma.85 The summary of royal favors from about five years later originally stated that the composer had not yet acquired the canonry: “he was presented for a canonry at Ávila in the indult, which has not yet fallen vacant” (Appendix 3a). However, a later note was added to the effect that Cristóbal de la Concha, sacristan of the Castilian royal chapel, claimed that Anchieta had received it and that, if it were served (that is, if Anchieta were to be resident), it was worth the substantial sum of 60,000 maravedís per annum. As in the case of the Granada canonry, no record of Anchieta serving as a canon at Ávila has yet come to light, and, again, he was probably forced to renounce it within a short period of time. Non-residency would have proved a major stumbling block to Anchieta holding a cathedral canonry for any length of time, even though in 1508 (and possibly earlier in previous papacies), Ferdinand secured papal license to grant members of his chapel up to a year’s absence from the royal chapel to attend to their ecclesiastical posts.86 It is thus interesting that a marginal note in the summary of royal favors indicates that Anchieta’s position was considered, at least by the sacristan, as appropriate (“convenible”) overall (Appendix 3a).87

Other kinds of ecclesiastical positions held more potential and more flexibility for the absentee member of the royal chapel, and Anchieta did successfully acquire another benefice, possibly in compensation for the Granada canonry: the préstamo (or part of a prebend) of Villarino in the see of Salamanca, valued at the substantial sum of 35,000 maravedís per annum (more than the basic annual salary [30,000 maravedís] as a chaplain and singer in the Castilian royal chapel). This benefice had previously belonged to the Bishop of Astorga, Juan de Castilla y Enríquez (1460–1510), who had been the monarchs’ papal legate to Alexander VI, and who was appointed to the bishopric of Astorga in 1493, and to that of Salamanca in 1498.88 By the late 1490s, the benefice appears to have been held by Alfonso Fernando de Luque, a cleric from Jaén, who renounced it in favor of Anchieta.89 On 12 June 1499, Anchieta took possession of the benefice through his proxy, Bernaldo de Vozmediano, with the customary ceremonial that included the ringing of the wheel of bells.90 As mentioned earlier, Vozmediano was one of Anchieta’s colleagues in the royal chapel who also served Margaret of Austria.91 This valuable préstamo was held by Anchieta for the rest of his life, and, as will be discussed in more detail later, was to play a critical role in the establishment of a Franciscan convent in his hometown of Azpeitia.

It was generally the ambition of singer-chaplains serving at court to obtain benefices in their hometown or region, and, probably at about the same time as the Villarino benefice, Anchieta achieved exactly this when he was appointed rector of the church of San Sebastián de Soreasu in Azpeitia following the death of the previous incumbent, Juan de Zavala, in 1498.92 Coster suggests that the appointment came as a gift from Anchieta’s cousin, the church’s patron Beltrán de Oñaz, whom—according to Coster—the royal chapel singer had apparently helped to secure the marriage between his (Oñaz’s) son, Martín García de Oñaz, and Magdalena Araoz, a maid-of-honor to Queen Isabel, but there is no documentary evidence to confirm the singer’s personal intervention in the marriage.93 In 1503, Anchieta took five months’ leave from the royal chapel, probably to take formal possession of the rectorate,94 and during that time he appointed Domingo de Mendizábal as his vicar to discharge his duties in the parish. Coster believed that it was possibly during this prolonged visit to Azpeitia that Anchieta may have met his relative, the young Ignatius of Loyola, who would have been about twelve years old, and that possibly he advised him about entering royal service as a singer, but again this is supposition on Coster’s part.95 Both the position of rector in Azpeitia and Ignatius were later to cause Anchieta serious problems.

Anchieta’s first period of royal service from his appointment in 1489 until the death of Isabel in November 1504 can only be considered as highly successful. His monetary and other pecuniary rewards were substantial, with the accumulation of valuable ecclesiastical benefices, including a prestigious position in his hometown Azpeitia, and he must have been a figure of considerable prestige and wealth by the time of his visit there in the summer of 1503. Of all the musicians in the Castilian household, he must have been the most eminent, and his musical ability had been recognized through the composition of pieces for occasions of particular importance to the monarchy (notably in 1489, possibly in 1492, and quite probably in 1497). During these years, Anchieta worked alongside other composers in the Castilian and Aragonese royal chapels, among others including Fernando Pérez de Medina, Pedro de Porto, Lope de Baena, Juan Álvarez Almorox, the Tordesillas brothers, and, from 1498, Francisco de Peñalosa.96 After the death of the queen in November 1504, Anchieta was not taken into the Aragonese royal chapel, as were at least ten other singers from Isabel’s chapel,97 because he was already in the service of her daughter Juana in Flanders.

Anchieta and the Burgundian chapel (1504–1506)

Queen Isabel died on 26 November 1504, but it seems that Anchieta was paid only for the first three months of the second tercio of 1504 (May to July),98 suggesting that he may have traveled with Juana to Flanders in the summer of that year, not to return to Spain for almost two years. While in Flanders, he was paid by Philip from the Burgundian household accounts, and he would have been in direct contact with the singers of the Burgundian chapel, many of whom he would already have met in Toledo in 1502. This prolonged sojourn in Flanders, followed by two more years serving alongside his Franco-Netherlandish colleagues in Spain between 1506 and 1508 (see later in the chapter), must have had an impact on the Spanish composer. Although it is the music of Anchieta’s younger colleague, Francisco de Peñalosa, that demonstrates not just knowledge but also profound assimilation of the works of Josquin and other northern composers, it is difficult to believe that Anchieta was not involved in the transmission of northern polyphonic repertory to Spain. An analysis of the extant data relating to Anchieta’s time in Flanders reveals some interesting details, not least that he was appointed music master to Juana’s children, including the future Charles V.

In May 1504, Juana, who had been detained in Castile against her will by her mother following the early departure of her husband Philip (27 February 1503), finally began her journey back to Flanders; she left her fourth child, Ferdinand, born on 10 March 1503, with his grandparents. Anchieta probably traveled with her, or he may have set sail a few months later on 28 October 1504, in the entourage of the Bishop of Córdoba, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca (1451–1524).99 According to the Burgundian account books, he appears to have been paid as a chaplain and a singer, as well as music teacher of the Habsburg children, throughout 1505.100 Both the bishop and the composer were involved in the intrigue surrounding Juana in Flanders, following the death of her mother in November 1504 and the ensuing battle for supremacy over the Castilian crown between her husband Philip and her father Ferdinand. Fonseca, together with the Castilian ambassador at the Burgundian court, Gutierre Gómez de Fuensalida, and Ferdinand’s private secretary, Lope de Conchillos, strove to gain access to Juana to have her sign the papers that would nominate her father as governor of Castile.101 The Flemish courtiers, including Adrian of Utrecht, sought to prevent this by virtually incarcerating Juana in the ducal palace in Brussels; Anchieta, in his role as music master, was one of the few Spanish servants to be allowed frequent access to the queen’s chambers, and attempts were made to secure his services as a mediator on behalf of Philip’s cause, and possibly, as Mary Kay Duggan suggested, as a spy against Ferdinand.102

As Gómez de Fuensalida wrote to the king in March 1505:

A meeting of the Great Council was held on Good Friday [1505] … and a friend told me that many matters were discussed, including the following: that they should strive to gain the queen’s agreement with the king, her husband, so that she would not write anything to Your Highness without them knowing about it, and that Juan de Anchieta would be a good intermediary for this, as the queen passes her time singing, and he could, under that guise, tell her everything they wished. The said Juan is as great an enemy of Your Highness as if the Archbishopric of Toledo had been taken from him.103

Whether Anchieta was a spy for Philip or not, the reason for his alleged animosity toward Ferdinand is not clear; perhaps he was influenced by the Flemish courtiers—or just watching his back—given that Philip was legally King of Castile and officially the musician’s employer, or possibly he had expected to be recalled from Flanders following Isabel’s death and made chapelmaster of the Aragonese royal chapel. Some years later, as will be discussed later, when Juana was confined to Tordesillas and Ferdinand was acting as governor of Castile, Anchieta would be appointed to the king’s chapel and rewarded with an abbacy.

During his time in Flanders, Anchieta was officially tutor (maistre d’ escolle) to the Habsburg children: Leonor (b. 15 November 1498), Charles (b. 24 February 1500), and Isabel (b. 18 July 1501).104 He may well have begun some musical instruction with the seven-year-old Leonor and possibly with the five-year-old Charles; perhaps Juana’s children became familiar with something of their Spanish musical heritage.105 In his capacity as “maistre d’escolle de Monsr le prince de Castille et de Mesdames Lyenor et Ysabeau ses seurs, enffans du roy de Castille,” Anchieta was granted a one-off payment toward the end of September 1505 of one hundred livres in order to pay off his debts in Flanders and return to Spain (see Appendix 3d).106 It is not clear whether Anchieta managed to settle his accounts and return to Spain before Philip and Juana set sail for Castile in early January 1506; it seems likely that, with plans for the journey underway during the last months of 1505, he waited to travel with the fleet.

The question of Anchieta’s travel plans for his return to Spain is of some importance, given that the Flemish fleet was to be forced to make an unscheduled visit to England in which the Basque singer would have been involved if he journeyed with them. The only piece of “evidence” embedded in the historiographical tradition that would contradict his traveling with the Flemish fleet relates to his intervention as rector of the parish church of Saint Sebastián de Soreasu in the appointment of a beata to the local hermitage of the Third Order of Franciscans. This is first presented in Eugenio de Uriarte’s notes for Barbieri as occurring in March 1506,107 that is, before the Flemish fleet had reached Spain. Stevenson, and subsequent biographers, have tended to repeat this “fact,”108 although no evidence has been found to indicate that Anchieta was actually in Azpeitia at that time, and Stevenson himself assumes that Anchieta was in England.109 Lizarralde refers to the active intervention of Anchieta’s vicar, Domingo de Mendizábal, in events around this time,110 suggesting that the composer was absent and that his intervention must have taken the form of correspondence. Indeed, Lizarralde includes details of Anchieta’s request a year or so earlier to the Vicar General of Pamplona, Juan de Santa María, for all parishioners and residents of Azpeitia who had not confessed and taken communion in the parish church within the year prior to 10 May 1506 to be excommunicated.111 At that time, Mendizábal declared that the five beatas at the hermitage had not confessed and had continued to take communion in their own oratory; he went to where they were celebrating mass and ordered them to stop.112 It would seem, therefore, that as late as May 1506, Mendizábal was acting on Anchieta’s behalf, and the composer could have traveled with the Flemish entourage.

The return to Spain (via England) (1506–1508)

According to the anonymous account of this journey from Flanders to Spain,113 Philip had hoped to set sail before Christmas 1505, but the necessary provisions took longer to assemble than planned, and the wind changed several times before it was favorable.114 By 7 January 1506, the assembled company of Flemish courtiers and servants of the Burgundian household had boarded the ship in Flushing in Zeeland, awaiting the arrival of the King and Queen of Castile. Mass was celebrated at 2 am on Thursday, 8 January, following which the fleet of between thirty-six and forty ships set sail and, despite some variable weather, including snow, made reasonably good progress until, having left the English Channel, they were becalmed. A terrible storm broke out on the night of 13 January, and the southeasterly winds blew the ships back toward the Cornish coast. About half the ships, including the vessel under the captainship of Juan de Metteneyre that carried the members of the Burgundian chapel,115 were washed up in the bay of Falmouth, Cornwall. Was Anchieta on this ship with his colleagues of the Burgundian chapel? Confusion reigned over the next ten days as news was sought of the safety and whereabouts of the ship bearing Philip. It was finally located in the Bay of Portland, near the coast of Dorset, although the fleet had been severely depleted, and, according to the anonymous chronicler, the king had thought he was going to die. However, they landed safely at Melcombe Regis, near Weymouth, and word was sent to Henry VII of the unscheduled royal visit.116

The welcome for Philip was prepared, with great assembly of nobles and ostentatious display, at Windsor Castle; indeed, Philip’s journey from the south coast was delayed by over two weeks, so that preparations could be made. Henry VII finally met Philip with a league from Windsor, and the elaborate ceremonial began. The festivities are described in somewhat conventional, but nicely rhetorical, terms by the anonymous chronicler; it is clear that they were designed to impress the unexpected visitors:

the two kings entered the beautiful castle of Windsor, and there is no need to ask whether his [Philip’s] entourage was well received and fêted, or whether there was a lot of fine wine and meats of good quality, or whether all the musical instruments were heard, or whether the castle was well decorated and adorned with rich tapestries of gold cloth and silk, or whether there was a large amount of gold and silverware throughout the castle, or whether all the princes, knights, gentlemen and officials belonging to the King of Castile’s entourage were honored and welcomed there.117

The festivities continued until 26 March 1506. Although it is difficult to determine from the Flemish chronicle alone, Anchieta was probably present in Windsor at some point. Juana only entered Windsor on 10 February, and left early, bound for Falmouth, where Philip’s fleet was to assemble to continue the onward journey to Spain. She met her sister Katherine of Aragon, but only briefly, probably for political reasons. Katherine had arrived in Windsor at almost the same time as Philip, and she, the Princess Mary (who also played the lute for Philip), and some other ladies danced before him.118 Thus, if Anchieta was in Juana’s entourage, he would have spent scant time in Windsor. It would seem unlikely that Philip would have met Henry VII without his own chapel, even though the chaplains and singers would also have had to make the journey to Windsor from Falmouth. Assuming that Anchieta did travel with the Flemish fleet, and assuming he traveled from the south coast to Windsor, he would have experienced the elaborate ceremonial of the English court.

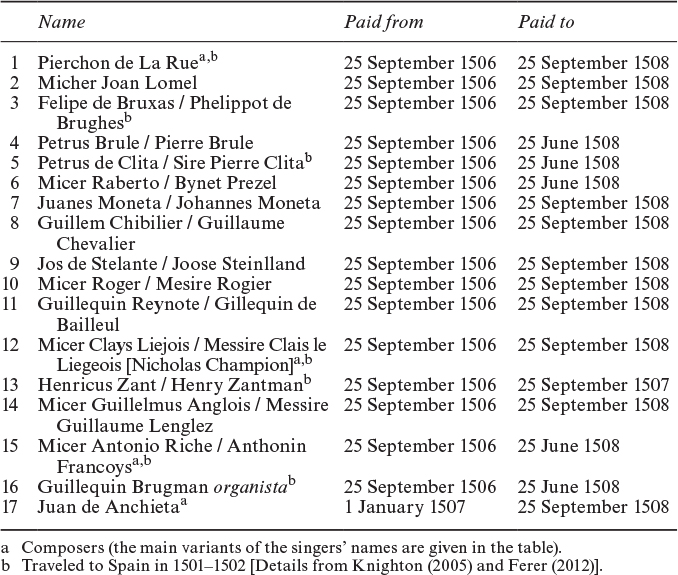

The Flemish ships finally left Plymouth on 22 April 1506, and reached La Coruña four days later. The composer was to remain closely connected with the Burgundian chapel for several more years. Following Philip’s sudden death on 25 September 1506, his Flemish singers, headed by La Rue, were paid in the Castilian household; from at least the beginning of 1507,119 Anchieta was the only musician of Spanish origin to be paid alongside them (see Table 1.2).120

Table 1.2 Flemish singers paid alongside Anchieta from September 1506 to September 1508

It can be seen that from the sixteen musicians who traveled with Philip the Fair to Spain in 1506, ten stayed the full two years before returning to Flanders, where they rejoined the chapel of Philip and Juana’s eldest son, Charles.121 Initially at least, the primary function of the Flemish music chapel was to perform the music for Philip’s exequies, including the Office and Mass for the Dead and the funerary responsories; it is likely that La Rue composed his Requiem mass for this occasion,122 and Anchieta’s ubiquitous setting of the responsory Libera me, Domine would surely have been performed in this context. Juana paid the singers well: 45,000 maravedís per annum, or 15,000 maravedís above the highest paid singers in the Castilian royal chapel in her mother’s time. Her preferential treatment toward these Flemish singers drew comment, not always entirely favorable because of their exaggerated payments and exclusive privileges, and her refusal to sign other more important documents of state were considered indicative of a weak, indecisive, and probably unbalanced mind.123 The Italian humanist Peter Martyr of Anghiera (1457–1526) commented on the sequence of events in his correspondence. In a letter dated 22 November 1506 to the Archbishop of Granada and the Count of Tendilla, Martyr wrote:

They could wrest neither signature nor word from her… As yet she has not touched a single paper save the pay vouchers of the Flemish singers who alone of Philip’s entourage were admitted to her household; for she takes great delight in their musical melodies, an art which she learnt at a young age.124

Peter Martyr’s words are echoed in an anonymous Flemish account of the time:

she will deal with nothing, whatever it may be, other than her retention of the majority of the singers of her former husband, and she treats them very well, always paying them for three months in advance, and she often gives them robes or horses and other items, and she takes no pleasure in anything else.125

Like her brother Juan, Juana was taught by Anchieta, and there is no reason to doubt that she appreciated the music of her husband’s Flemish choir, whom she rewarded so well. Moreover, the Flemish choir was essential to the realization of the prolonged exequies held for Philip. Juana determined that his body, in accordance with his title of King of Castile (and with significance for the position of her son Charles as his legitimate heir to the Crown), should be taken to Granada for burial, as had occurred with her mother in 1504.126 The weather, the delayed return of Ferdinand from Naples (and the resulting political implications), and her own pregnancy (her daughter Catalina was born on 14 January 1507) all conspired to delay the realization of her wish. As the weeks and months went by, and Philip’s embalmed body remained unburied, Juana seems to have become almost obsessed with the Flemish singers whose music, according to Martyr, soothed her melancholy state of mind; in June 1507, Martyr wrote to the Duque del Infantado:

The Queen wanted none of the clergy present except the Flemish, whom she chose as singers from her husband. By the hour their music calms her and brings solace to her melancholy travails as a widow.127

Juana’s melancholia and her apparent incapacity to take up the reins of government contributed to the return to Castile of her father Ferdinand and her political sidelining followed by enclosure at Tordesillas.128 The Flemish choir continued to be paid until 25 September 1508, although several members, including Bynet Prezel, Anthonin Françoys (de Riche), and the organist Guillequin Brugman, left to return to Flanders during the summer of that year.129 Anchieta thus spent the best part of two years working alongside La Rue and his colleagues; the musical implications of this extended period of co-service is considered in the corresponding chapters on his music. One work that may date from this period in which Anchieta in effect formed part of the Burgundian chapel is the anonymous motet Musica, quid defles?, a lament on the death of Alexander Agricola, which took place in August 1506.130 Although preserved anonymously in a much later source—Georg Rhau’s Symphonia jucundae of 1539—there is no doubt that the work was composed on the occasion of Agricola’s death (its subtitle reads “Epitaphion Alexandri Agricolae symphonistae Regis Castellae”) and, as is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3, the musical idiom is very close to that of Anchieta’s other motets.

Anchieta in Tordesillas (1508–1512)

In the years after the Flemish singers finally left Spain, Anchieta continued in royal service, moving from Juana’s employment to that of her father and, following his death in 1516, to that of her son Charles who traveled to Spain the following year. The pay documents show that he was paid as a “capellán e cantor” in the Castilian royal household, while the Flemish singers remained in Spain, and in the years after Juana’s withdrawal to Tordesillas until he was pensioned off by Charles V and free to take up full-time residence in Azpeitia.131 The extent to which Anchieta resided in Tordesillas during these years, especially after his appointment as a singer and chaplain in the Aragonese royal chapel in 1512, is hard to determine. While the dismantling of Juana’s Flemish chapel was likely a deliberate and symbolic act to indicate her lack of power following her father becoming governor of Castile on his return to the kingdom,132 she must have continued to find solace in music and also, in established royal tradition, provided for the musical education of her daughter Catalina (born on 14 January 1507): was Anchieta also to serve as her music teacher?

The remnants of Juana’s court were established, on Ferdinand’s orders, at Tordesillas in the autumn of 1508, and although between 1508 and 1512 Anchieta continued to receive the high annual salary (45,000 maravedís) granted to the Flemish singers—the payments being authorized by her father—some biographers have suggested that he spent much of his time in Azpeitia.133 During these years, Anchieta was quite active in his capacity as rector of St. Sebastián de Soreasu, notably in terms of the lawsuit between him and the new lay patron of the church, though he may well have been involved only at a distance.134 After the death of Loyola’s father Beltrán de Oñaz in 1507, the position of lay patron was inherited by his firstborn son, Martín García de Loyola (Ignatius’s elder brother), who disputed Anchieta’s right to appoint his successor as rector—the composer clearly had in mind his nephew, García de Anchieta, while Martín García de Loyola was preparing the way for his own son (see later)—and collect income from tithes and altar collections. All Anchieta’s claims were dismissed in a royal cédula dated 30 October 1510.135 In August of that year, Anchieta had also intervened in the election of the serora of the hermitage of Santa María Magdalena in Azpeitia, but was he actually there? The pay lists for the royal household of Juana “la loca” are continuous throughout 1508 to 1514, and Anchieta appears to have collected his salary payments himself.136 Thus, if he did visit Azpeitia from time to time during this period, he did not stay there long.137

Little is known about musical life at Tordesillas.138 Juana had been taught by Anchieta and was apparently an accomplished musician; Gómez de Fuensalida’s correspondence reveals that she spent her time singing in her chambers in Flanders. She also appears to have played keyboard in her retrete; her chamberlain, Hernando de Mena, was one of several servants of the chamber who testified to Juana’s carelessness with her valuable possessions: “often some jewellery and other items were left on a table in the chamber when her highness sat down to play” (“muchas veces estaban algunas joyas e otras cosas sobre una mesa en el retrete donde su alteza se asentaba a tocar”).139

A few musicians were employed at Tordesillas in addition to Anchieta, both in chapel and chamber. From 1 September 1508, Juana’s official chapel constituted a head chaplain, the Bishop of Málaga, Domingo Ramírez de Villaescusa, and ten chaplains.140 The chaplain Alonso de Alba (not the composer of that name, who had died in 1504) served as sacristan and was responsible, for example, for the arrangements for the construction of the monument in her chapel in Holy Week.141 The organist Martín de Salzedo, who was paid until the early 1520s when Charles recruited him for his own chapel, presumably participated in the celebration of the liturgy at Tordesillas.142 A small organ (realejo) from the early sixteenth century survives at Tordesillas, and Salzedo may have played that instrument.143 Other keyboard instruments were inventoried at Tordesillas in 1509, notably a claviorgan (“vn claviorgano con sus fuelles en su caxa”) and a clavichord (“vn monacordio metido en su caxa”) with a tuning device (“vn templador de monacordio”), and these instruments were still there at the time of her death, together with a vihuela (“Vna cajyta de ceti carmesi y dentro otra caxa de madera blanca con unos aljofarios y vna bihuela todo como la mano”).144 By 1555, these instruments were in poor condition, and were handed over to the camarero Alonso de Ribera “to dispose of them as he feels best” (“para que dispusiese del[los] como le paresciese”).145

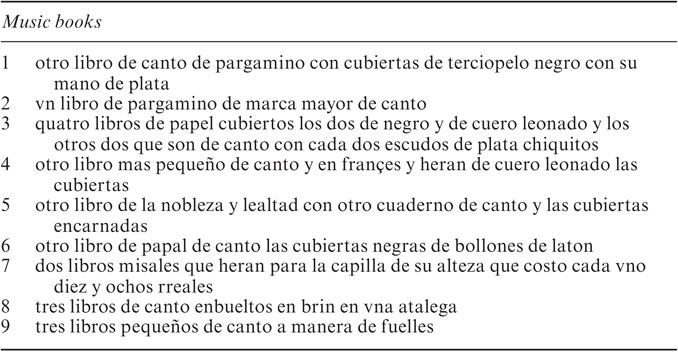

While Juana never had a polyphonic chapel after 1508,146 chamber musicians were employed in her household at Tordesillas, and these included the singer Gabriel de Texerana (“Gabriel el Músico”), the vihuelist Martín Sánchez and his son Juan, a recorder player, as well as the organist Martín de Salzedo, though it is not altogether clear whether these musicians were there during Anchieta’s time.147 Texerana was first paid in the Aragonese household in 1496, and appears in the pay lists of chapel singers between 1500 and 1502, after which his immediate whereabouts are not known: in 1516, he entered the household of Ferdinand’s cousin, Fadrique Enríquez, Admiral of Castile, whose court was based at nearby Medina de Rioseco.148 He then served Juana at Tordesillas from 1523 until his death in 1528.149 The vihuelist Martín Sánchez served at Tordesillas and the organist Martín de Salzedo from at least 1517,150 though they may have been there earlier. By at least 1523, Martín Sánchez is recorded as being in the service of Princess Catalina.151 Thus, it is not clear if Anchieta was the only musician at Tordesillas during the period 1508 and 1512, but at least some of his music would have been copied into the music books owned by Juana in 1509. Table 1.3 lists the music books inventoried in Tordesillas in 1509.152

Table 1.3 Music books belonging to Juana “la loca” (1509–1555)

These music books, all apparently lost, must surely have contained works by Anchieta. Several of the music books were bound in black velvet or leather, and may have contained repertory related to the music for the dead, sung for Philip the Fair. One book contained French-texted chansons, which presumably dated from Juana’s years in Flanders. The entry referring to “the book of nobility and loyalty with another music book” (“la nobleza y lealtad con otro cuaderno de canto”) is curious, and not easy to interpret. It is not clear what happened to these music books; by the time of her death in 1555, most of them would, like the instruments, have been in a poor state of repair.

Anchieta in the service of the Aragonese royal chapel (1512–1516)

In the years 1508–1512, Anchieta appears to have remained in active service at Tordesillas while dispatching business related to his parish church in Azpeitia. However, on 15 April 1512, while Ferdinand’s court was at Burgos, he was admitted to the Aragonese royal chapel with an annual salary of 30,000 maravedís, supplemented in the Castilian household accounts with the 45,000 maravedís he had previously been receiving from Juana. Whatever previous animosity—if any—the composer might have held toward Ferdinand while serving Juana in Flanders had clearly dissipated by 1512. If it can be assumed that Anchieta actually served in the Aragonese royal chapel during the last four years of Ferdinand’s life, he would have formed part of a body of over forty singers that included its leading light, Francisco de Peñalosa. The previous year, Peñalosa had been appointed music master to Ferdinand’s grandson and namesake, the young Prince Ferdinand.153 Other composers in the Aragonese chapel at that time included Alonso de Mondéjar, Juan Ponce, and Alonso (or possibly Pedro) Hernández de Tordesillas, and Anchieta would also have met up again with his former choirboys and colleagues Bernaldo de Vozmediano and Antonio de Corral.154

Always a beneficiary of royal largesse, Anchieta continued to reap the rewards of being in royal service. In April 1513, while the court was at the Jeronymite monastery of La Mejorada near Valladolid, Anchieta was presented to the abbacy of Arbas in the see of Oviedo, a position that came under royal patronage.155 An Augustinian community already existed at Arbas in northern León when a hospital was founded in about 1116 on the pilgrimage route between Oviedo and Santiago de Compostela. King Alfonso IX of León (1171–1230) lodged there, and in 1216 endowed the construction of the church of Nuestra Señora de Santa María de Arbas next to the pilgrim hospital. In 1419, it was secularized. Thus, although geographically the abbey notionally fell under the see of Oviedo, it had, from earliest times, been independent from it and came under royal right of presentation. It is not known how much income Anchieta secured from this prestigious dignity, but throughout the remainder of his life he adopted the title of Abbot of Arbas.156 In the codicil to his will, Anchieta mentioned that the income from the abbacy was collected on his behalf by Jorge de Valderas, resident of León (see Appendix 3h).157

After King Ferdinand’s death (1516–1519)

Between April 1512 and January 1516, Anchieta was thus serving as chaplain-singer in the Aragonese royal chapel, although he is thought to have been absent at least some of this time in Azpeitia, notably in the early part of 1515, as will be discussed later.158 This period of royal service brought further recognition and rewards, but after only four years, his highly remunerated position was disrupted. Following Ferdinand’s death on 22 January 1516, the choir of the Aragonese royal chapel, with well over forty singers being paid in the royal household, was summarily disbanded,159 and many of them were left without employment or forced to fall back on ecclesiastical benefices they had received through royal patronage. Peñalosa, for example, returned to his disputed canonry at Seville cathedral, although he quickly found favor at the papal court.160 Anchieta, who for so long had served Juana, must have realized that the nominal Queen of Castile was in no position to secure his future, even though he had continued to be paid in the Castilian royal chapel. He thus appealed directly to Margaret of Austria in Flanders, reminding her that he had served her as chapelmaster during her years in Spain,161 and asking for her intervention in securing an abbacy in his native Guipúzcoa: clearly, at this point, certainly past fifty and possibly in his sixties, he seems to have been thinking about his retirement plans.162 He laments the death of the king, but moves quickly on to the purpose of his missive (see Appendix 3e for the original text):

I would rather have written to Your Highness with better news and with happier matters to relate, but I ask Your Highness that you receive it in accordance with the moment and with God’s will. Your Highness will know the King Our Lord has died and that his death was as his life—a saint would not have died with greater Catholicism, and God have mercy on his soul. No doubt you will already have heard this from many others, but I wanted you to know all that I know for my own part, and I beg Your Highness to remember me, for much time has passed, and the office I used to hold for the prince and Your Highness [illegible], and I have placed my hope in all things with Your Highness; and a servant of Lady Beaumont will ask you on my behalf for an abbacy and I ask you very humbly that you approve it on your command. I therefore close by praying that Our Lord will protect and maintain your life, and keep and increase your royal estate in accordance with the desire of your excellent heart. Most excellent Lady, I humbly kiss the feet and hands of Your Majesty.

J. Anchieta, A. de Arvas163

Margaret must have agreed to her former chapelmaster’s request, for Anchieta’s brother, Pedro Garcia de Anchieta, subsequently wrote to inform her that the presentation was being contested in Rome:

Pero Garcia de Anchieta, brother of Joanes de Anchieta, Your Highness’s chapelmaster, having kissed your hands, informs you that an abbacy in the province of Guipúzcoa that Your Highness asked for Joanes is now at the centre of litigation in which a Bishop Loaysa, servant in Rome, asked for the favor without realizing that no-one other than a native of the province can possess the said abbacy and that this was a condition of its foundation; and since Joanes was born in the said province and since Your Highness has first favor, I ask you very humbly that you intervene in this instance so that Joanes does not lose his right to it, and that you communicate this to the chancillor and Monsieur de Chèvres, not forgetting that he was your chapelmaster.164

Faced with the diaspora of the Aragonese royal chapel, Anchieta was clearly anxious to secure a position and income in the region of his birth, but there is no evidence to suggest that he ever secured an abbacy in Guipúzcoa. Nevertheless, he did continue to find royal favor. Charles V, having assumed the Spanish throne and traveled to Spain in 1518, recalled the composer’s “many and good services”;165 clearly, he personally remembered his first music master, and perhaps he had received reports of Anchieta from the singers of his Flemish chapel. In a royal decree dated 15 August 1519, Charles ordered the mayordomo and accountants of his mother’s household to continue to pay Anchieta his full salary of 45,000 maravedís, even though this went against the efforts being made to reorganize the queen’s household, and even though the singer was not necessarily residing at court:

Joanes de Anchieta, chaplain and singer of Her Highness [Juana], has told me that he had and has an annual salary and expenses in the queen’s household of 45,000 maravedís, which sums were always paid him until the Catholic King, my lord and grandfather, died (may he rest in peace), whether he resided in Her Highness’s court or in his house, and from that time he has not been paid, and now he has been told that with the reform of the said household it was agreed that in recompense for the 45,000 maravedís, he should be paid only 25,000 maravedís, which he considers to be demeaning, and he asked me that, notwithstanding the reform, I order that he should be paid the 45,000 maravedís in full, or whatever my favor would be; and I, bearing in mind the many and good services that the said Joanes has rendered me and that he is now too old to reside at our court, believe it right to order you, notwithstanding the reform and that he does not reside at court, that he be paid the said 45,000 maravedís this year, from the date of my decree and in future years … of which I grant him favor whether residing and serving at our court or not residing, as he wishes….166

Anchieta continued to be paid his salary of 45,000 maravedís until his death almost four years later in July 1523, even though for most of that time he was too ill to serve at court: on 20 September 1520, and again in May 1521, he is described as being unwell and residing at home with Charles V’s permission.167 In 1523, in the months leading to his death, the wording in the pay documents was changed to “aunque no aya rresidido porque está viejo y enfermo.”168

Anchieta served various members of the Trastámara and Habsburg dynasties—Queen Isabel, her children, notably Prince Juan and Princess Juana, Margaret of Austria, her brother Philip the Fair, and his children, notably Charles V, and Juana as queen—and received favors from them all. In his will, he mentioned his position as chapelmaster to Prince Juan, and endowed three annual masses for his principal benefactors, Ferdinand and Isabel, thus recognizing, in the face of his impending death, the prestige and wealth he had acquired through their patronage. Anchieta’s royal career took him to Flanders and probably England, and brought him into contact with not only the singers of the Castilian, Aragonese, Burgundian, and probably English chapels, but also with those of the cathedrals, monasteries, and collegiate and parish churches of the Spanish kingdoms through the peripatetic nature of the court, with which he traveled and resided until he became too old and sick to do so. The contact with and exchange of polyphonic repertory between him and those serving in these various institutions must have been considerable.

Anchieta and Azpeitia (from c1500–1518)

Anchieta, like other members of the royal chapels, sought to secure ecclesiastical positions and benefices in his home territory. This helped to maintain connections with family and friends, and, in Anchieta’s case—and very possibly others in an age when clergymen quite often fathered children—he had his own family to support. In this quest for preferment, Anchieta was, to a large extent, successful while still in royal service, gaining the income from the benefice in Villarino, the rectorate of the parish church of San Sebastián de Soreasu in his native Azpeitia and the abbacy of Arbas, even though, along the way, he was not able to take up canonries in Granada and Ávila, nor did he acquire the disputed abbacy in the Guipúzcoa region he had hoped to obtain with Margaret of Austria’s intervention. His appointment to the rectorate in Azpeitia was not made through the patronato real but lay in the gift of his cousin, Beltrán de Oñaz, grandfather of Ignatius of Loyola and the parish church’s patron, who was sixty-one at the time of Anchieta’s appointment.169 The previous incumbent as rector, Juan de Zavala, died in 1498, so Anchieta could not have been appointed until after that time.

As mentioned earlier, Coster suggested that he secured the rectorate, having contributed in some way to the marriage of another of Oñaz’s sons to a royal maid-of-honor.170 While this is purely speculative, such quid pro quos in cases of preferment were common practice. San Sebastián de Soreasu, which belonged to the See of Pamplona, was, at the time of Anchieta’s appointment, the only parish church in the region, although some twelve hermitages existed in and around Azpeitia. The church was well endowed, with about seven benefice-holders, two chaplains, and an organist, whose income had to be paid for by the patron from the tithes gathered from the local community.171 The Anchietas owned a solar or manor in nearby Urrestilla, and by the first half of the fifteenth century represented one of the leading families of the region, together with the Loyolas.172 The age-old feud between the principal families had been, to some extent, resolved by the marriage of Anchieta’s father, Martín García de Anchieta, to María Veraizas de Loyola, though resentments and rivalries continued to simmer under the surface, and appear to have erupted in around 1515, with near-catastrophic results for the renowned royal musician, as will be discussed later. Anchieta’s appointment to the rectorate itself was to revive a considerable amount of tension, not least when he decided to build a chapel of some magnificence.173