5 The songs

Tess Knighton

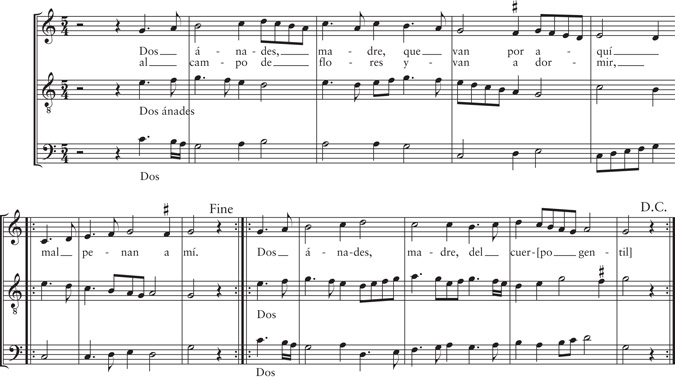

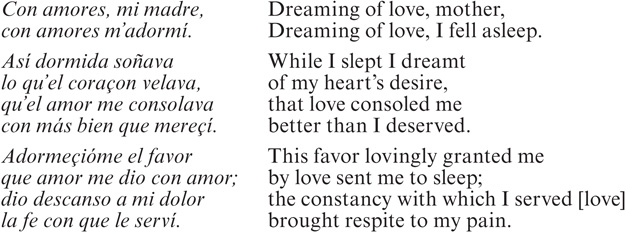

Only four songs are securely attributed to Anchieta, but each is representative of the different genres and styles of song that were cultivated in court circles in the years around 1500. All are preserved uniquely in the Palace Songbook (the Cancionero Musical de Palacio, often abbreviated simply Palacio or CMP). Two—Dos ánades, madre and Con amores mi madre—belong to the popular song tradition that was adopted and adapted by court composers who wrote polyphonic settings that were, to some extent, “courtlified.” This combination of popular refrain with more complex musical settings and often a more sophisticated style in the strophes is characteristic of the amalgamation of courtly and popular elements found in the songs of Juan del Encina, a hybrid style he developed while serving at the Duke of Alba’s court near Salamanca in the 1490s.1 It seems unlikely that Anchieta composed these songs, which adopt the unusual  1∕5 time signature discussed later, before that time. These popular song texts were widely diffused in the sixteenth century.

1∕5 time signature discussed later, before that time. These popular song texts were widely diffused in the sixteenth century.

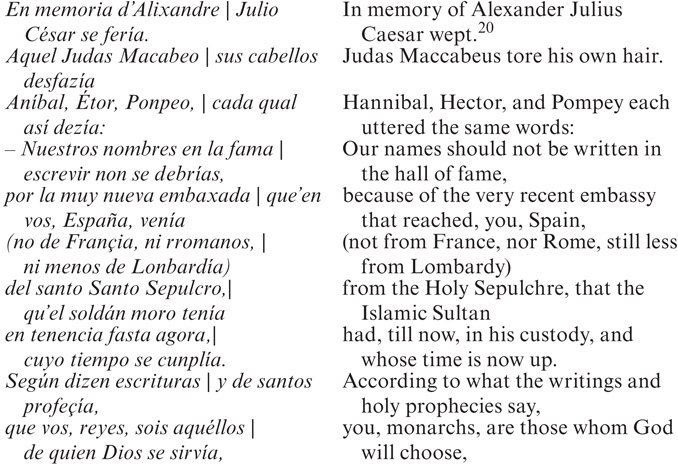

En memoria d’Alixandre is a romance and one of a number of ballads in the Palace Songbook to extol the Catholic Monarchs’ victories during the Reconquest of Granada. The particular exploit recounted in Anchieta’s romance can be accurately dated and thus serves as an indication of his role as a court composer; clearly, he was expected to compose such pieces on his appointment to the Castilian royal chapel. The Granadine romance, given the circumstances and expectations of its creation, can be seen as a kind of Staatsmusik in the vernacular, a form whose purpose was not only to spread news and entertain, but also to promote the image of the monarchs.2 Donsella, madre de Dios is a typical sacred villancico that reflects the shift—already observed in Anchieta’s motets—in spiritual and devotional tendencies in court circles in the 1490s (see Chapter 3).3 It formed one of the almost thirty pieces listed under the heading of “Villançicos omnium sanctorum” in the original tabla of the Palace Songbook.

The language (Castilian), verse forms, and musical style used in Anchieta’s songs place them in the specific court context of the time of the Catholic Monarchs; their creation and function was similar to that of other European courts of the time.4 The centrality of song to court culture is well expressed by Diego de San Pedro in his sentimental novel Cárcel de amor (Seville, 1492), where he describes the twenty reasons why men are indebted to women. The seventeenth reason is that “women inspired music and made [men] take delight in it, composing sweet songs, performing lovely ballads, singing polyphony, refining and enriching everything to do with song.”5

Although Encina’s style came to dominate, song-settings in the CMP range from the simplest sequences of homophonic chords with repeated harmonic patterns, to more complex, contrapuntally conceived pieces.6 Almost all the songs in the CMP are constrained by the repetition schemes of forme-fixe structures, with an estribillo (refrain) and mudanza (verse), based on an ABBA musical repetition scheme.7 The A section typically consists of two to five clearly delineated musical phrases, depending on the number of lines in the estribillo, and the B section (mudanza) of two musical phrases that were immediately repeated before returning to the A section (or vuelta).

The villancico, disparaged earlier in the fifteenth century for its rustic origins,8 was thematically very diverse, including poems of courtly love as well as bawdy ditties and popular dance songs. The villancico en cosaute (usually with a two-line refrain) remained especially close to dance and improvised song traditions even when cultivated in court circles.9 The singing—and dancing—of cosautes were participatory entertainments at court, which included the improvisation of poetic lines to simple, well-known melodic formulae by the courtiers themselves, as is clear from the description of entertainments at the court of the Constable of Castile in Jáen toward the end of the reign of Enrique IV.10 King Enrique, Isabel’s half-brother, may well have been in part responsible for increased interest in and appreciation of song; royal chroniclers described his penchant for and skill in singing, notably romances and songs, and “it was a pleasure to hear [them].”11

The success of song as part of courtly entertainment in the second half of the fifteenth century was almost certainly heightened by the introduction of literary and musical puns and coded messages, often full of sexual innuendo, and/or making oblique reference to individual members of a closed circle of the elite.12 In order for these witticisms and double entendres to be appreciated by the listener, the poetic texts needed to be clearly audible, whether performed by a soloist with instrumental accompaniment, or in relatively simple polyphony.13 The long narrative of the romance was traditionally communicated by a solo voice accompanied by a plucked-string instrument, and this mode of performance was undoubtedly adopted in other song types.14 From about the 1450s onward, there was also an increasing vogue in court circles for the polyphonic canción, which called for all-vocal performance in some contexts, and eventually evolved into the simpler, homophonic, largely syllabic villancico in which the text was easily heard.15

The standard form of the romance generally had no refrain and was based on the repetition of four musical phrases, clearly punctuated by cadences (with the final chord of each phrase marked by fermata) for each hemistich of the poetic text as many times as required by the text.16 It was thus essentially a strophic forme fixe rather than being through-composed,17 and allowed little or no development of the expressive relationship between words and music. Nevertheless, some evidence of a musico-textual dialectic can be found in the choice of mode, and in small details such as harmonic or chromatic inflections or changes in texture.18 This small-scale and limited notion of word-painting is sometimes found in the canción / villancico form where the last line (or lines) of the estribillo and the vuelta is repeated with the same musical phrase (or phrases). Anchieta’s songs, in particular, display notable sophistication and subtlety despite their musical concision.

Anchieta’s romance

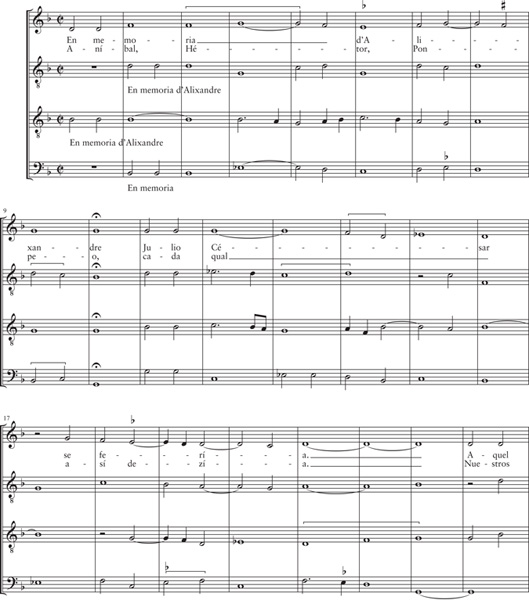

En memoria d’Alixandre (no. 20 in the worklist, Appendix 1)—4vv, romance19

Francisco Asenjo Barbieri in his preliminary study was the first to draw attention to the event for which Anchieta’s romance was originally composed: the diplomatic visit in the summer of 1489 of the ambassadors of the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Beyazid II (1447–1512), to the army camp where Ferdinand’s troops had laid siege to the Andalusian town of Baza.23 The sultan had sent two Franciscan friars from Jerusalem to Rome to request Pope Innocent VIII, to intervene with the Catholic Monarchs and persuade them to abandon their offensive in the kingdom of Granada. Their continuation of this attack would, the sultan claimed, lead inevitably to reprisals that would include the destruction of the Holy Sepulchre and monasteries and convents in the Holy Land, as well as the persecution of Christians. According to the royal chroniclers’ accounts of the friars’ subsequent mission to Ferdinand outside Baza, the king countered with an offer to provide the sultan with Sicilian troops and money to aid his own war in Egypt. The embassy went on to visit Isabel in Jaén, although she later joined the camps outside Baza, heralded by trumpets, drums, and ministriles altos,24 where victory was attained in December 1489.25

Anchieta, who entered the Castilian royal chapel in February 1489, only a few months prior to the diplomatic visit in Jaén, must have been commissioned to write the romance by the queen, either in Jaén or Baza.26 Its messianic vision of the taking of Jerusalem formed an integral part of royal image-making at the time:27 Ferdinand was seen as a latter-day crusader, skillful in arms, while Isabel was the devout queen whose prayers were deemed equally effective.28 Reference in the ballad text to great military leaders of Classical Antiquity and the Old Testament was intended to extol King Ferdinand’s military prowess to the extent that he might achieve the reconquest of Jerusalem itself.29

The historical Reconquest ballad had its roots in the traditional frontier ballad, with narrative elements on both sides of the winner-loser divide, but it was exploited by the Catholic Monarchs—or their advisers—as a more official genre that combined the traditional format and verse structure with a notated polyphonic form of expression developed and performed by members of the royal chapels to add solemnity and prestige.30 This reflects a practice well established by the reign of Enrique IV (r.1454–1474);31 in 1462, he commissioned a ballad to be written during his Granadine campaigns and then ordered his chapel singers to set it to music “so that it would be better remembered.”32 Polyphonic settings of romances survive in the CMP by Francisco de la Torre, singer in the Aragonese royal chapel from 1483 to 1494, and his colleague in the Castilian chapel, Anchieta.33 The task of writing these “official” ballad texts was probably assigned to Hernando de Ribera, who was employed as court poet (“trobador”) in the Aragonese royal household from August 1483 until at least August 1501, and whose duties included recording events in verse immediately after they occurred.34 According to the royal chronicler Lorenzo Galíndez Carvajal, Ribera was a native of Baza and

wrote about the Granadine wars in verse; [he wrote] the truth, as I often heard the Catholic King say, so it must be true, for when an event or something worthy of note happened, he put it into rhyming verse and read it at his highness’s table, where all those who were involved in the deed approved or corrected it, according to what had really occurred.35

It seems likely, therefore, that Ribera—or another court poet—wrote the verse for En memoria d’Alixandre, and that Anchieta’s polyphonic setting lent it greater impact, although it could also have been performed to a plucked-string accompaniment in more “private” moments. In his Compendio historial (written in 1479 and presented to Queen Isabel in 1491), Diego Rodríguez de Almela recorded:

in order to be more at their leisure when they lunched and dined, and when they wanted to go to bed, they [princes of old] also commanded that their minstrels and singers came with their lutes and vihuelas and other instruments so that they might play and sing the ballads that were devised to tell of celebrated knightly deeds.36

Rodríguez de Almela, talking of “kings and princes of the past,” refers to the tradition of performing romances with instrumental accompaniment; this mode of performance continued throughout the sixteenth century,37 and could also apply to Anchieta’s En memoria d’Alixandre.

According to José Romeu Figueras, the polyphonic version of En memoria d’Alixandre, preserved uniquely in the Palace Songbook at ff. 76v–77, formed part of the original layer of the manuscript in the second stage of its copying around 1500; it is included in the over forty romances listed under the generic heading “Romançes” in the original tabla of CMP.38 Emilio Ros-Fábregas places the inclusion of the romances at the heart of the earliest stage of copying, on watermarked paper that he dates from the late 1490s.39 Either way, Anchieta’s romance would seem to have been copied in the decade after the events it describes, suggesting that it—along with the other Granadine ballads listed earlier—still had validity as record of the king’s heroic deeds in the kingdom of Granada.

The text of En memoria d’Alixandre in the Palace Songbook consists of twenty-one lines, and may possibly be incomplete, although the final extant lines, with the apotheosis of Ferdinand’s future victory in Granada indicated by the celebrations in Rome, at which all would sing “Gloria in excelsis,” seems an appropriate enough ending.40 The traditional caesura dividing each line into hemistichs is observed by Anchieta, who provides four musical phrases for each two full lines of text; each of these full lines ends with a cadence on G (Example 5.1). As Maricarmen Gómez has pointed out, the first phrase of the melody bears a striking resemblance to that of an anonymous ballad-setting in the CMP Morir se quiere Alixandre (CMP, no.111). The mode (transposed Dorian with one flat) is the same, and in both songs the melody falls to a lower tessitura after a declamatory opening, although the melodic contours in phrases 2 to 4 are rather different.41 It is fair to assume that Morir se quiere Alixandre was well known in court circles: it was cited twice by Antonio de Nebrija in his Arte de gramática, printed in Salamanca in 1492, and again in Jerónimo Pinar’s Juego trovado, which the poet dedicated to Queen Isabel in 1496.42 It seems likely that Anchieta knew this ballad and deliberately cited the first phrase of its melody to make the connection with the reference to Alexander the Great in a traditional narrative romance, and by so doing reinforce still further the greatness in the Roman manner of Ferdinand’s achievements in the kingdom of Granada.

The four musical phrases repeated throughout Anchieta’s four-voice version of En memoria d’Alixandre are not set in a completely homophonic manner, and the opening offers a fleeting moment of imitation that is not sustained after the first two breves (see Music Example 5.1). Nevertheless, it shares the declamatory, almost recitational quality of Morirse quiere Alixandre and most other romances, with each melodic phrase beginning with repeated notes. Musical phrases 1, 3, and 4 are punctuated by a simultaneous cadence marked by a fermata; phrase 2 has a more sustained, but equally clearly marked, cadential point, even though it is not marked by a fermata in the manuscript and the bass note is held over to the start of phrase 3 to lend a sense of continuity.

Textural elaboration is complemented by a degree of sophistication in the harmonic realization of the transposed Dorian-mode melody; Anchieta’s setting is altogether more subtle than the essentially homophonic three-voice setting of Sobre Baza estava el rey.43 Anchieta adds a degree of ambiguity at the opening, with the harmony moving from B-flat through E-flat to C, before a cadence on C-G. The second phrase appears to be going in the direction of a cadence on D, but the prolongation takes it back to G (D-G), out of which the third phrase grows organically. This third phrase returns to the B-flat area suggested at the opening, before the final phrase cadences firmly on G (D-G). The transposed Dorian mode was a popular choice among the cancionero composers, and the rousing and positive character attributed to it by most theorists—whether Spanish or Italian—would be appropriate enough for the confidence and optimism conveyed by the text.44

Anchieta’s setting of En memoria d’Alixandre is more extended and subtle than many of the other romances in the Palace Songbook, without compromising the audibility of the text essential to the ballad’s narrative and image-making function. As an “official” ballad, probably performed by the singers of the royal chapels, it would have had a direct and sonorous impact at court festivities and celebrations: a vocal counterpart to the emblematic sounds of the trumpets and drums.

A plea to the Virgin Mary

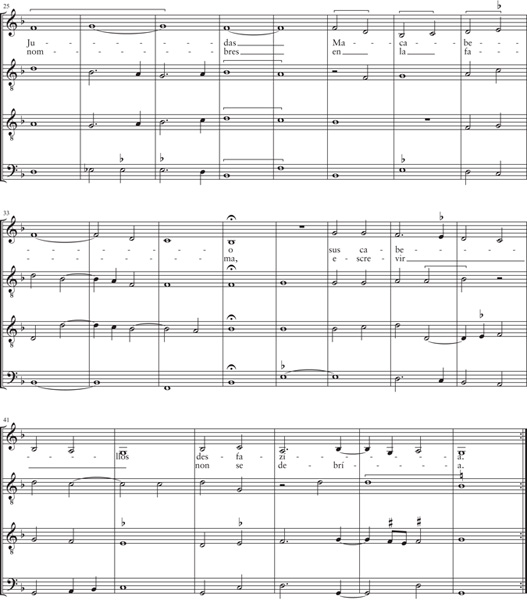

Donsella, Madre de Dios (worklist no. 18)—3vv, devotional villancico45

Romeu Figueras considers Anchieta’s Donsella, Madre de Dios to have been copied among the devotional songs included as the fourth addition made by the original scribe to the Palace Songbook in around 1505.48 This seems a reasonable dating, although it should be noted that there is little concrete evidence to support it. Nor is there any clue as to the author of the text, but—if not by Anchieta himself—the poet clearly had connections in court circles since his verses reflect spiritual trends developed in that context at the end of the fifteenth century. As Romeu Figueras notes, the poem marks the transition from the medieval paean to the Virgin Mary to the late fifteenth-century exegetical approach of experiencing and identifying with the Passion through the eyes of Christ’s mother in the manner of the Latin sequence Stabat mater.49 The Virgin Mary is presented, with reference to the hymn Ave maris stella, as a lodestar to guide the human sinner through repentance to redemption by following the stages of Christ’s death and burial just as St. John guided her along the way to Golgotha. Each of the four verses narrates her fateful journey to the Crucifixion, where her heart breaks at her Son’s suffering (strophe 2). The third strophe alludes to Christ’s descent into hell as the earth is plunged into darkness, while in the fourth, the narrative continues with his burial by Joseph of Arimathaea and Nicodemus in a place of incomparable beauty that anticipates his resurrection and which fills the listener with hope and expectation.

If the song is complete as it survives in its unique source, it would have been suitable for performance during Holy Week, and in particular on Good Friday and/or Holy Saturday. Its reference to details of the Passion according to St. John and, in particular, to John at Mary’s side, recalls the text of Anchieta’s motet Virgo et mater (see Chapter 3). The listener is invited to witness events through the Virgin’s experience, but is not urged to share in and so empathize with the physical suffering of Christ, as was the aim of the earlier Franciscan-based devotio moderna movement, but rather to comprehend those events through the intercession of the Virgin as guiding star.50 At the same time, the song follows the gospel narrative, inviting the listener to reach a greater understanding of its—and the Passion’s—central message: the redemption of mankind through Christ’s death on the cross. This narrative quality suggests that the verses were written in the last decade of the fifteenth century, around the same time as the translation of Ludolph of Saxony’s Vita Christi by fray Ambrosio Montesino between 1499 and 1501 at Isabel’s request;51 Romeu Figueras noted the song text’s transition from a medieval prayer to the Virgin, to the newer tendency toward a more Christocentric devotional practice.52 As Cynthia Robinson has commented, the narrative and descriptive approach to Christ’s suffering of the medieval Franciscan tradition became influential at court in the last decade of the fifteenth century.53 Anchieta may well have known Montesino, who, from 1492, was active in the court milieu as royal confessor. Donsella, Madre de Dios may even have been written by Montesino, whose collection of devotional verse entitled Coplas sobre diversos devociones y misterios de nuestra santa fe católica was first printed in Toledo in 1485, and later, in 1508, re-edited (as Cancionero de diversas obras de Nuevo trovadas) at the king’s request.54 His poems combine a strong sense of descriptive narrative designed to awaken an emotional response in the reader / listener to heighten contemplation (and so understanding) of the events of the Passion.55

There seems little reason to doubt that Anchieta composed this devotional villancico while he was in the service of the Castilian royal chapel, and very probably in the 1490s. Furthermore, it shares several musical features with the ballad En memoria d’Alixandre, notably its mode, the transposed Dorian, even if it is a more concise setting for only three voices (Example 5.2). The texture is similar, essentially homophonic, but not entirely so, with the two lower voices moving in parallel at the third or sixth at the relatively extended cadence points, where the melody becomes briefly more melismatic. The choice of mode was again probably deliberate: the anonymous copyist(s) of the theoretical notes bound with the copy of Gaffurius’s Practica musicae (1497) held at the Biblioteca Universitaria in Salamanca included a brief guide to composition, observing that it was “essential for every musician who wishes to compose to look at the text because there are eight modes,” the characteristics of which are then concisely summarized.56 Despite the lack of consistency between theorists as to the character of the modes, this text suggests—as do others—that the choice of mode was of some importance to composers. The Dorian mode, according to the anonymous copyist, was equally well suited to “deprecaciones” (prayers) and would thus be appropriate to Anchieta’s Marian villancico. As in his Dorian romance, B-flat is an important marker of harmonic contrast, notably in Donsella, Madre de Dios, at the “interrupted” cadence toward the end of the first phrase, and at the start of the B section.

Donsella, Madre de Dios, somewhat unusually for a villancico, has a two-line refrain, corresponding to two musical phrases for the estribillo and vuelta (A; ab), and a further phrase, repeated, for the mudanza (B; c). The two-line refrain limits scope for textual expression, but Anchieta nevertheless appears to introduce a deliberate articulation of the text at the beginning of the strophe (mudanza), where the repeated plea that articulates the prayer, “Guïadnos,” is set to sustained chords and followed by a rest in the superius (see Music Example 5.2).57 Even though this opening phrase is subsequently set to different words in line two of the mudanza of each strophe, it would have had an impact on the listener through clear articulation of the poetic structure, which, at the same time, highlighted the central message of guidance by the Mother of God. In addition to the parallel movement between the lower voices in the preparation of cadence points, the texture is characterized by a repeated syncopated rhythm of minim–two quavers–minim that lends the brief piece a subtle sense of cohesion. The combination of clefs—ATB—suggests that this Marian prayer may well have been sung by adult members of the Castilian royal chapel during the observance of the hours during Holy Week as stipulated by its calendar of sung feasts.58 Very possibly, it was sung in contemplation of the Monument erected in the chapel to hide the host on the triduum of Holy Week. Its elegantly simple, dramatic style is characteristic of the slightly more elaborate, courtlified song-settings of the composers of the royal chapels from around the 1490s onward.

Two popular song settings

At first glance, the two popular song settings attributed to Anchieta—Con amores, mi madre (CMP, no. 335) and Dos ánades, madre (CMP, no.177)—are markedly different from his image-making romance and devotional villancico. Both were copied into the Palace Songbook after its original redaction, probably, according to Romeu Figueras, at some point in the first two decades of the sixteenth century.59 It is thus more difficult to gain a sense of chronology in these two pieces, and they could have been composed at almost any point during Anchieta’s extended period of royal service. Both also invoke the popular theme of a young girl confiding in her mother about her dreams or experiences of love, and both are notated in an unusual quintuple rhythm. Five quintuple-meter songs were copied in the Palace Songbook at about the same time, but no direct association between theme and meter can be ascertained.60 While the estribillo of Con amores, mi madre is clearly of popular origin, the strophes have the language and conceits of a more formal courtly song. In his De musica libri septem of 1577, Salinas dedicated a chapter (Book VI, Chapter 13) to quintuple meter, extrapolating from St. Augustine and Aristotle, that quintuple rhythms were generally eschewed by sophisticated court poets but were commonly found in popular song in the vernacular.61 In 1978, Juan José Rey suggested that Anchieta’s quintuple-meter songs might have had roots in the zortzico, a popular song from the Basque country typically transcribed in 5/8.62 If this were the case, there would certainly be an intriguing connection on the part of the composer and the popular song forms of his native region which established a mini-vogue for this meter in courtly song.

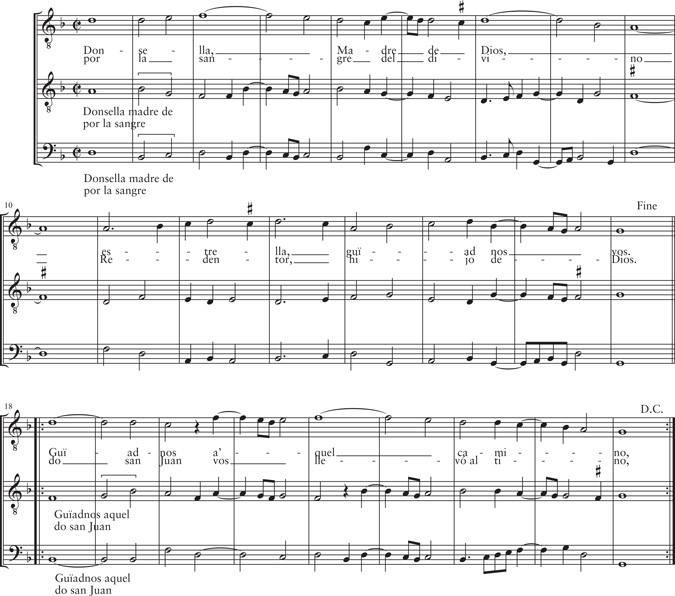

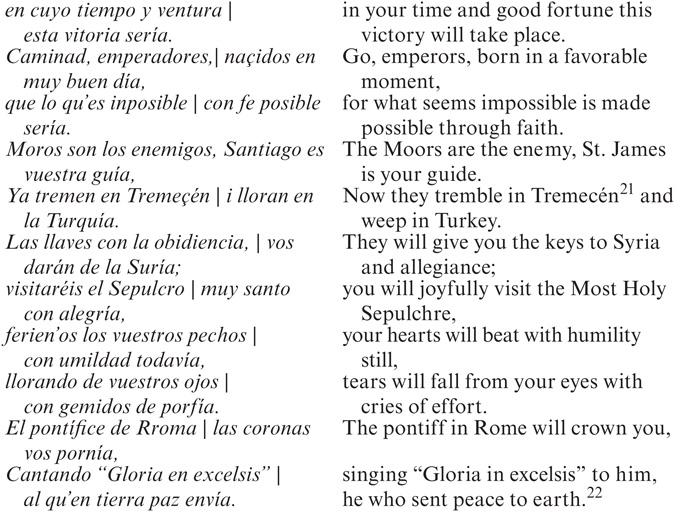

Con amores, mi madre (worklist no. 17)—4vv, villancico63

The popular refrain, with a young girl confiding in her mother about her dreams of love, makes way for a more courtly approach, though still from the female viewpoint, lending the standard theme of unrequited love another dimension. Her dream is that her love will be fulfilled, even to a greater extent than she feels she deserves; love has granted her this sweet dream, and the pain caused by her love being unreciprocated is assuaged by her own constancy. It seems that Anchieta’s musical setting deliberately also highlights this juxtaposition of popular and courtly, with a simple melody of just two phrases, with a vocal range of an octave, while his setting is more elaborate (Example 5.3). First, he extends the second phrase of the melody by repeating it sequentially down a tone, thus also reiterating the second line of the refrain. This little repetition, marked by a signum congruentiae in all four voices, is unexpected and gives greater structural interest to what would otherwise be a very brief and repetitive song, for the setting of the mudanza comprises only the first melodic phrase repeated, giving the overall pattern of a modified villancico: abb’aaabb’. In addition, the overall four-voice texture is quite complex, with independent movement in all three of the lower voices throughout and not just in the build-up to cadence points. As in his other song settings, Anchieta often has a pair of voices moving in parallel thirds and sixths, but here the rhythmic momentum is maintained through the melodic dotted figure being diffused through the texture as a whole. The song is firmly in the Lydian mode,64 with the first phrase anchored in F; it is articulated by a rest in all voices after the cadence. The second phrase moves to D, and is linked to the sequential repetition by the three lower voices, even though a rest occurs again in the superius. A striking downward scale covering the interval of a sixth in the altus brings momentum to the close of the estribillo. Indeed, the whole piece is filled with an irresistible sense of rhythmic energy, combined with an attractive melodiousness, that accounts for its popularity among modern audiences.

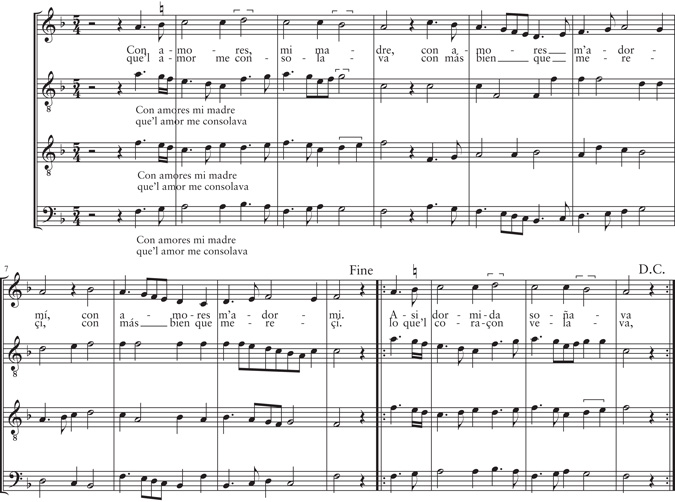

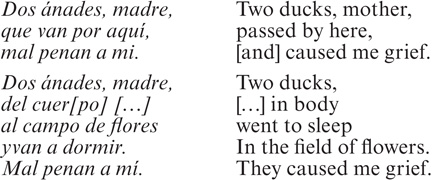

Dos ánades, madre (worklist no. 19)—3vv, modified villancico65

The popular roots of this song are evident in both text and structure, and the text certainly enjoyed wide popularity throughout the sixteenth century and beyond, being cited in the literature on many occasions. The text in the Palace Songbook is incomplete: the second line of the verse lacks the last three syllables.66 Romeu Figueras considered Dos ánades, madre to be a cosaute with a three-line estribillo and a distich with assonantal rhyme on the stressed –i on the even hemistichs. As mentioned earlier, performance of the cosaute, with its roots in popular tradition, in court circles involved a high degree of improvisation, at least as far as the text was concerned; this might account for the missing word after “cuer[po]” in the only surviving written source. Further verses might well have been improvised, each starting with the repetition of “Dos ánades, madre,” as well as the exact repeat—text and music—of the third line of the refrain which is indicated to be sung twice each time. In all, only about ten words would need to be improvised for each strophe.

In literary sources throughout the sixteenth century and beyond, the song was associated with a carefree attitude, usually sung, with the addition of a third duck, “tres ánades,” by an individual while walking or traveling along. Sebastián de Covarrubias, in his Tesoro de la lengua castellana (1611), gives quite a detailed explanation under the heading “Ánade”:

It is in the duck’s nature to move in water; meaning that one goes cheerily, without thinking about work, we say that one goes along singing “Tres ánades madre,” which is an ancient and very widespread song that goes: “Three ducks, mother, / passed this way, / and caused me grief.”67

Gonzalo Correas, in his Vocabulario de refranes y frases proverbiales y otras formulas communes de la lengua castellana (1627), agreed with Covarrubias that the song referred to “doing something with ease” and to “pleasure and a carefree attitude.”68

Anchieta’s three-voice setting of Dos ánades, madre is similar to that of Con amores, madre with lively rhythmic activity and independence of the different vocal parts (Example 5.4). Upward and downward scalar figures, seemingly scattered among the three voices, characterize his version; possibly the original melody is presented in a slightly elaborated form.69 The mode is mixolydian (G), which drew a mixed interpretation from the theorists; the Salamancan copyist considered it appropriate for victory, while other writers on music associated it with bravery, playfulness, and even anger.70 The setting is very concise, but it is difficult to see how it might have been improvised polyphonically, even if the text had originally lent itself to participatory entertainment.

It is likely that Anchieta composed more songs than the four that have survived in the Palace Songbook, but these nevertheless provide a good sample of his skills as a song composer, and it is tempting to think that they may have been performed in the setting of Prince Juan’s palace in Almazán (see Chapter 1).

Notes

1 Jane Whetnall, “Secular Song in Fifteenth-Century Spain,” in Tess Knighton, ed., Companion to Music in the Age of the Catholic Monarchs (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 60–96, especially at 84–89.

2 Ramón Menéndez Pidal, Romancero hispánico (hispano-portugués, americano y serfardí), 2 vols. (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1940), II: 23, 25.

3 See Cynthia Robinson, Imagining the Passion in a Multiconfessional Castile: The Virgin, Christ, Devotions, and Images in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013), especially at 317–84.

4 For a comparison with Italy, see Reinhard Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 1380–1500 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 570–85.

5 Cited in Menéndez Pidal, Romancero hispánico, II: 27: “La decisiete razón es porque [las mujeres] nos conciertan la música y nos hazen gozar de las dulcedumbres de ella, por quien se asuenan las dulces canciones, por quien se cantan los lindos razones, por quien se acuerdan las voces, por quien se adelgazan y fertilizan todas las cosas que en el canto consisten.”

6 Roy O. Jones and Caroline Lee, eds., Juan del Encina: Poesía lírica y cancionero musical (Madrid: Clásicos Castalia, 1975), 7–51.

7 The classic study of fifteenth-century Spanish song forms is Isabel Pope, “Musical and Metrical Form of the Villancico: Notes on Its Development and Its Rôle in Music and Literature in the Fifteenth Century,” Annales Musicologiques 2 (1954): 189–214. See also David Fallows, “A Glimpse of the Lost Years: Spanish Polyphonic Song (1450–1470),” in Josephine Wright and Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., eds., New Perspectives in Music. Essays in Honor of Eileen Southern, Detroit Studies in Musicology / Studies in Music, 11 (Warren, MI: Harmonie Park Press, 1992), 19–36; and Whetnall, “Secular Song in Fifteenth-Century Spain.”

8 Whetnall, “Secular Song in Fifteenth-Century Spain,” 79–84.

9 José Romeu Figueras, “El cosaute en la lírica de los cancioneros musicales españoles de los siglos XV–XVI,” Anuario Musical 5 (1950): 15–61. Pepe Rey describes this kind of semi-improvisatory form as the “villancico en cosaute”; see Pepe Rey, “Música coral vernácula entre el Medioevo y el Renacimiento,” Nassarre, XVIII, 1–2 (2001): 23–63.

10 See Maricarmen Gómez Muntané, “La música laica en el reino de Castilla en tiempos del condestable Don Miguel Lucas de Iranzo (1458–1473),” Revista de Musicología 19 (1996): 25–45; and Tess Knighton, “Spaces and Contexts for Listening in 15th-Century Castile: The Case of the Constable’s Palace in Jaen,” Early Music 25 (1997): 661–77; and Giuseppe Fiorentino, “Unwritten Music and Oral Traditions at the Time of Ferdinand and Isabel,” 504–48, especially at 528–32.

11 “[El rey] cantaba muy bien de toda música, ansí de la iglesia como de romances e canciones, e había gran plazer de oírla”; this description was included by the chronicler Diego Rodríguez de Almela in his Compendio Historial, cited by Menéndez Pidal, Romancero hispánico, II: 24.

12 See the classic, and highly influential, study by Keith Whinnom, La poesía amatoria de la época de los Reyes Católicos (Durham: University of Durham, 1981); see also Roger Boase, Secrets of Pinar’s Game. Court Verse and Courtly Ladies in Fifteenth-Century Spain (Leiden: Brill, 2018), and Knighton, “Spaces and Contexts.”

13 Much later in the sixteenth century, Francisco de Salinas, in his De musica libri septem (1577), commented on the question of audibility in both these modes of performance (Book VI, Chapter 1); see Ismael Fernández de la Cuesta (trans.), Francisco de Salinas, Siete libros sobre la música (Madrid: Editorial Alpuerto, 1983), 500.

14 Maricarmen Gómez [Muntané], “Some Precursors of the Spanish Lute School,” Early Music 20 (1992): 583–93.

15 Tess Knighton, Música y músicos en la corte de Fernando de Aragon, 1474–1516 (Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, 2001), 153–57; Whetnall, “Secular Song in Fifteenth-Century Spain,” 75–79.

16 On the performance length of romances and other songs in court circles, see Emilio Ros-Fábregas, “Melodies for Private Devotion at the Court of Queen Isabel,” in Barbara Weissberger, ed., Queen Isabel of Castile: Power, Patronage, Persona (Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2008), 81–107.

17 There are a few notable exceptions in the CMP: see Tess Knighton, “A New Song in a Strange Land? Garcimuños’s Una montaña pasando,” in Fabrice Fitch and Jacobijn Kiel, eds., Essays on Renaissance Music in Honour of David Fallows: Bon jour, bon mois, bonne estrenne, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Music 11 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2011), 186–96.

18 Tess Knighton, “Approaches to Text-Setting in Castilian-Texted Devotional Songs c. 1500,” in Marie-Alexis Colin, ed., French Renaissance Music and Beyond: Studies in Memory of Frank Dobbins (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), 427–53.

19 Versification: assonantal rhyme on –ía in second hemistich; eight + eight syllable lines, marked by a caesura;

Musical structure: A, consisting of four musical phrases (abcd) repeated for whole of text.

20 According to Plutarch’s lives (second century AD), Julius Caesar wept on reading Alexander’s biography since Alexander had achieved many triumphs at an age when Caesar had, according to his own estimate, done nothing memorable. Plutarch’s Vitae parallelae siue Vitae illustrium uirorum was translated into Castilian by Alonso de Palencia and published in Seville in 1491; Queen Isabel owned a manuscript copy (“escripto de mano, en romançe”); see Elisa Ruiz García, Los libros de Isabel la Católica. Arqueología de un patrimonio escrito (Salamanca: Instituto de Historia del Libro y de la Lectura, 2004), 488–89.

21 Tlemcen, a province in Algeria.

22 See Maricarmen Gómez Muntané, “En memoria d’Alixandre de Juan de Anchieta en su contexto,” Revista de Musicología 37 (2014): 89–106, at 105–06.

23 Francsico Asenjo Barbieri (ed.), Cancionero musical de los siglos XV y XVI (Madrid: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Francisco, 1890), no. 328, 165–66. Barbieri was followed by José Romeu Figueras, La música en la Corte de los Reyes Católicos, IV-2: Cancionero Musical de Palacio, vol. 3-B, Monumentos de la Música Española 14-2 (Barcelona: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1965), hereafter abbreviated MME 14-2, 39–40, and, most recently, by Gómez Muntané, “En memoria d’Alixandre.”

24 The royal chronicler Andrés Bernáldez describes the queen’s arrival on the scene: “Los moros fueron mucho maravillados de su venida en invierno, e se assomaron de todas las torres e alturas de la cibdad, ellos y ellas, a ver la gente del recebimiento e oír las músicas de tantas bastardas e clarines e trompetas italianas e cheremías e sacabuches e dulçainas e atabales, que parescían que el sonido llegava al cielo”; see Knighton, Música y músicos, 151.

25 See Gómez Muntané, “En memoria d’Alixandre,” 91–92. A detailed contemporary description is found in Andrés Bernáldez, Memorias de los reinados de los Reyes Católicos, ed. Manuel Gómez-Moreno and Juan de M. Carriazo (Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1962), 206–10.

26 An anonymous three-voice setting, Sobre Baza estava el rey (CMP, no. 135), relates to the same event.

27 Menéndez Pidal, Romancero Hispánico, II: 24–25. Menéndez Pidal suggested (ibid., II: 31) that Francisco de la Torre’s setting of Pascua d’Espíritu Santo, which describes the surrender of Ronda in 1485, was performed a few days later on the feast of Corpus Christi on 2 June 1485 when “solemn ceremonies were held with the instrumental musicians and singers of the king and other nobles” (“fízose muy solene fiesta con los instrumentos músicos e cantores del rey e de los grandes señores”) (Bernáldez, Memorias, 162).

28 See Pedro M. Cátedra, La historiografía en verso en la época de los Reyes Católicos. Juan Barba y su “Consolatoria de Castilla” (Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 1989), and José Manuel Nieto Soria, Orígenes de la monarquía hispánica: propaganda y legitimación, c.1400–1521 (Madrid: Librería-Editorial Dykinson, 1999), 35.

29 As Maricarmen Gómez Muntané has pointed out in “En memoria d’Alixandre,” 95, four of the figures cited in the romance—Alexander the Great, Hector, Julius Caesar, and Judas Maccabeus—formed part of the nine “greats” of the chivalric hall of fame listed by Jacques de Longuyon in his Les voeux de Paon (1312). The list varied over time and according to author, but such military leaders were commonly—and very deliberately—associated with Ferdinand; see Tess Knighton and Carmen García Morte, “Ferdinand of Aragon’s Entry into Valladolid in 1513: The Triumph of a Christian King,” Early Music History 18 (1999): 119–64, at 131–33.

30 Other examples in the Palace Songbook that refer directly to the campaign in the Kingdom of Granada are: ¡Setenil, ay Setenil! (CMP 143, without music, 1484); Pascua d’éspritu Santo (CMP, no. 136, Francisco de la Torre, 1485); Sobre Baza estava el rey (CMP, no. 135); Por los campos de los moros (CMP, no. 150, Francisco de la Torre); Caballeros de Alcalá (CMP, no. 100, Lope Martínez); and Una sañosa porfía (CMP, no. 126, Juan del Encina, 1491?).

31 The earliest known example of the polyphonic ballad of royal propaganda is the anonymous Lealtat, ¡o lealtat! of about 1466, bound into a copy of the Hechos del Condestable Don Miquel Lucas de Iranzo. Robert Stevenson was the first to edit and discuss this piece in his classic study Spanish Music in the Age of Columbus (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1960), 204–06. Anchieta’s ballad is also briefly discussed in Strohm, The Rise of European Music, 576–77.

32 Ramón Menéndez Pidal, Flor nueva de romances viejos (Madrid: Tipografía de la Revistas de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos, 1933), 16. See also Tess Knighton, “The a cappella Heresy in Spain: An Inquisition into the Performance of the cancionero Repertory,” Early Music 20 (1992): 560–81, at 578; and Gómez Muntané, “En memoria d’Alixandre,” 93–95.

33 Menéndez Pidal, Romancero Hispánico, II: 30–31.

34 Knighton, “Música y músicos,” 158–59.

35 Knighton, “The a cappella Heresy,” 578. Lorenzo Galíndez Carvajal, “Anales breves de los Reyes Católicos,” Martín Fernández de Navarrete, ed., in Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España, xiii (Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1842), 243–44: “… que escribió la guerra del reino de Granada en metro; y en la verdad, según muchas veces yo oí al Rey Católico, aquello decía él, que era lo cierto; porque en pasando algún hecho o acto digno de escrebir lo ponia en coplas y se leía a la mesa de Su Alteza, donde estaban los que en lo hacer se había hallado, e lo aprobaban o corregían, según en la verdad había pasado.”

36 Ramón Menéndez Pidal, Poesía juglaresca y juglares, Publicaciones de la Revista de Filología 7 (Madrid: s.p., 1924), 376–77: “… por estar más desocupados quando comían e cenavan y quando se acostar querían, mandavan otrosi que los menestrilles e juglares viniesen con sus laudes y vihuelas y otros ynstrumentos para que con ellos les tañessen e cantasen los romançes que heran ynventados de los fechos famosos de cavallería.”

37 For the earlier tradition, see Gómez [Muntané], “Some Precursors of the Spanish Lute School.”

38 José Romeu Figueras, La música en la Corte de los Reyes Católicos, IV-1: Cancionero Musical de Palacio, vol. 3-A, Monumentos de la Música Española 14-1 (Barcelona: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1965), hereafter abbreviated MME 14-1, 7–13, and Higinio Anglés, ed., La música en la Corte de los Reyes Católicos, II: Polifonía profana: Cancionero Musical de Palacio, vol. 1, Monumentos de la Música Española 5 (Barcelona: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1947), hereafter abbreviated MME 5, 22.

39 Emilio Ros-Fábregas, “Manuscripts of Polyphony from the Time of Isabel and Ferdinand,” 404–68, especially at 415–28. Ros-Fábregas suggests that this core part of the manuscript was begun at the court of the Duke of Alba in Salamanca.

40 This “prophecy” finally came to pass in January 1492. For the celebrations in Rome, see M. Dolores Rincón González, Historia Baética de Carlo Verardi (drama humanístico sobre la toma de Granada) (Granada: Universidad de Granada, 1992).

41 Gómez Muntané (“En memoria d’Alixandre,” 97) points out that the structure of Morir se quiere Alixandre is not apparently that of a straightforward romance, although the piece is listed under “Romançes” in the tabla.

42 See Romeu Figueras, MME 14-2, 300–01, and Gómez Muntané, “En memoria d’Alixandre,” 97. See also Boase, Secrets of Pinar’s Game.

43 Strohm (The Rise of European Music, 578) describes Anchieta’s En memoria d’Alixandre as “a musically more interesting romance.”

44 Jack Sage’s unpublished paper, “Mode, Meaning and Metre in Spanish Renaissance Song” offered a preliminary study of the significance of the choice of mode in the cancionero repertory, an aspect taken further in Knighton, “Approaches to Text-Setting.”

45 Versification: two-line refrain (estribillo) with the rhyme scheme a-a, with four strophes rhyming b-b-b-a, and eight-syllable lines;

Musical structure: ABBA.

46 Presumably a reference to the sign prepared by Pilate to be nailed to the Cross: “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” (John 19: 19).

47 A reference to Joseph of Arimathaea and Nicodemus who, according to the gospel of St John, laid Christ’s body to rest in the tomb (John 19: 38–42).

48 Romeu Figueras, MME 14-1, 7–13.

49 Romeu Figueras, MME 14-2, 465.

50 Knighton, “Approaches to Text-Setting,” 438.

51 The translation was printed at Alcalá de Henares from 1502 to 1503.

52 Romeu Figueras, MME 14-2, 465, and idem, MME 14-1, 82, where he notes that this song and several others are written “in a dramático and affective manner, often with realistic and vivid elements, all very well suited to awakening the emotions and tears of the devout…” (“en estilo dramatico y afectivo, con frecuentes trazos realistas y vivos, todo muy apto para despertar la emoción y las lágrimas del devoto…”).

53 Robinson, Imagining the Passion, 359–60.

54 Knighton, “Approaches to Text-Setting,” 428.

55 Erna Ruth Berndt, “Algunos aspectos de la obra poética de Fray Ambrosio Montesino,” Archivum: Revista de la Facultad de Filología, Universidad de Oviedo 9 (1959): 56–71.

56 Tess Knighton, “Gaffurius, Urrede and Studying Music at Salamanca University around 1500,” Revista de Musicología 34 (2011): 11–36; eadem, “Approaches to Text-Setting,” 432–33.

57 Ibid., 438.

58 Knighton, “Música y músicos,” 244: “A Sabbato primo in cuaresma usque ad pasche Dicuntur omnes hore.”

59 Romeu Figueras, “La música en la corte,” MME IV-1, 7–13; he proposes the fourth inclusion for “Con amores, mi madre” and the fifth for “Dos ánades, madre.”

60 Three other pieces in quintuple meter were copied into the Palace Songbook at about the same time: Escobar, “Las penas, madre” (a 3) (CMP, no. 59); Encina, “Amor con fortuna” (a 4) (CMP, no. 102); and Diego Fernandes, “De ser mal casada” (a 4) (CMP, no. 197). The first of these is popular tone, while the other two are more courtlified. A further song in the Palace Songbook—the anonymous “Y haz jura, Menga” (CMP, no. 296)—is notated in duple time, but can be interpreted in quintuple meter; see Juan José Rey, Danzas cantadas en el Renacimiento español (Madrid: Sociedad Española de Musicología, 1978), 32–33.

61 Fernández de la Cuesta, De musica libri septem, 583–95, especially at pp. 584–85; see also Rey, “Danzas cantadas,” p. 32.

62 Rey, Danzas cantadas, 33; more recent commentators tend to follow Rey, see Jon Bagües, “Juan de Anchieta: Estado actual de los estudios sobre su vida y obra,” Cuadernos de Sección. Música 6 (1993): 9–24 at 22; and Juan Plazaola, Los Anchieta. El músico, el escultor, el santo (Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero, 1997), 96. In his edition of the Cancionero Musical de Palacio, Anglés generally transcribed these pieces in 12/8, 6/8, or 3/4, with the exception of “Con amores, mi madre” which he presents in 5/4.

63 Versification: two-line refrain n-a; two strophes: b-b-b-a; c-c-c-a; eight- syllable lines;

Musical structure: modified villancico: A (abb') A' (a) A' (a) A (abb').

64 The Lydian mode was consistently held by the theorists to be moderate and cheerful, which corresponds in a generalized way with the text.

65 Metrification: n-a-A n-b-n-b-A; six-syllable lines; musical structure: modified villancico; ABBA; abcc a’a’ abcc.

66 Romeu Figueras suggested that it should be completed “cuer[po gentil],” with an assonantal rhyme with the fourth line “yvan a dormer.” Romeu Figueras, MME, IV-2, 333. In his edition, MME 5, 206, Anglés simply has “del ca[mpo],” while Maricarmen Gómez has “de las [praderas],” without any explanation; see Maricarmen Gómez Muntané, “Une nueva transcripción de Dos ánades, madre de Juan de Anchieta,” Nassarre 12 (1996): 135–39, at 139.

67 Sebastian de Covarrubias, Tesoro de la lengua castellana, o española (Madrid: Luis Sánchez, 1611), 67–68: “Es propio del anade andar en el agua, para dezir que vno va caminando alegremente, sin que sienta el trabajo, decimos que va cantando Tres ánades madre, es una coplilla antigua y comun que dize: Tres anades mades, passan por aqui, / mal penan a mi.”

68 See Margit Frenk, Corpus de la antigua lírica popular hispánica (siglos XV a XVII), 2nd edn. (Madrid: Editorial Castalia, 1990), 86–87.

69 Earlier scholars such as Rafael Mitjana and Juan Bautista Elústiza suggested that the melodic line should be that of the tenor, while Miguel Querol rejected this in favor of the melody in the superius, which is surely correct, although he transcribes it in 2/4; see Romeu Figueras, MME 14-2, 333.

70 Knighton, “Approaches to Text-Setting,” 432.