Chapter 5:

Resistance, Collaboration, and Genocidal Aspirations

During the Second World War, Ukrainians were both victims and perpetrators. They fought both willingly and under coercion on the side of Stalin against Hitler, and on the side of Hitler against Stalin.[1110] According to estimates by historians, 6,850,000 people (16.3 percent of the population), were killed in Ukraine during the Second World War, of whom 5,200,000 were civilians of various nationalities.[1111] When Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, about 2.7 million Jews lived in the territory of present-day Ukraine, or 2.47 million within the borders of the Ukrainian SSR of 1941. During the German occupation of Ukraine, which lasted for some two years in its western territories, and for some three years in its eastern ones, the Germans, with the help of their accomplices, killed more than 1.6 million Ukrainian Jews. Half of them were annihilated in eastern Galicia and Volhynia, whose united territory was much smaller than the rest of the country. Among the 900,000 Ukrainian Jews who saved themselves by escaping with the Soviet Army, there was only a very small number from western Ukraine. The number of survivors in western Ukraine was also low. Whereas 97 percent of the Jews in the Ternopil’ oblast did not survive the Holocaust, 91 percent of the Jews in the Kharkiv oblast survived. In general, among the 100,000 Jews who survived the war in Ukraine in hiding or in Nazi slave labor camps, there were less than 20,000 from eastern Galicia and Volhynia.[1112]

In eastern Galicia 570,000 Jews and in Volhynia 250,000 were annihilated in four stages. The first stage was the pogroms, which cost about 30,000 Jewish lives in both regions, and which were analyzed in the previous chapter in connection with the “Ukrainian National Revolution.” In the second stage, which began during the pogroms and lasted until the end of 1941, Einsatzgruppe C shot about 50,000 Jews in eastern Galicia and 25,000 in Volhynia. The third stage differed between eastern Galicia and Volhynia. About 200,000 Jews in Volhynia were shot close to the ghettoes or in the local fields and forests. The Einsatzkommandos and Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police), who were assisted by the Ukrainian police, finished the murder of Volhynian Jews in late 1942. In eastern Galicia, more than 200,000 Jews were sent to the Bełżec annihilation camp, 150,000 were shot, and 80,000 were killed or died in the ghettos and labor camps. The extermination of the majority of eastern Galician Jews was completed in the summer of 1943. In the fourth stage, about 10 percent (80,000) of all western Ukrainian Jews fought for their lives while hiding in the woods, countryside, towns and cities. Ukrainian nationalists were involved in different ways in all four stages of the murder of the western Ukrainian Jews and committed other massacres of civilians, while pursuing their revolutionary and genocidal ideas.[1113]

The OUN-M and the Question of Eastern Ukraine

During the first weeks after the onset of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the OUN-M, like the OUN-B, also sent task forces to organize a state in Ukraine. Although the OUN-M task forces in western Ukraine were less of a presence and less effective than the OUN-B’s, the OUN-M managed to establish the Ukrainian National Council (Ukraїns’ka Natsional’na Rada, UNR) in Kiev, an administrative organ dissolved by the Germans on 17 November 1941.[1114] In Bukovina, OUN-M members staged pogroms in towns and villages around Chernivtsi.[1115] The OUN-M leader Andrii Mel’nyk was no less eager than Bandera to collaborate with the Germans. On 26 July 1941, the newspaper Rohatyns’ke slovo republished Mel’nyk’s article “Ukraine and the New Order in Europe” including:

We collaborate closely with Germany and invest everything in this collaboration: our heart, feelings, all of our creativeness, life and blood. Because we believe that Adolf Hitler’s new order in Europe is the real order, and that Ukraine is one of the avant-gardes in Eastern Europe, and perhaps the most important factor in strengthening this new order. And, what is also very important, Ukraine is the natural ally of Germany.[1116]

Both before and after the German attack on the Soviet Union, there was ruthless conflict between the OUN-B and the OUN-M. The OUN-M activists Omelian Senyk and Mykola Stsibors’kyi were murdered on 30 August 1941 in Zhytomyr, in all probability by the OUN-B.[1117] According to OUN-B member Myron Matviieiko, his fellow-member Mykola Klymyshyn organized the assassinations.[1118] Taras Bul’ba-Borovets’ wrote that the “Banderite Kuzii” killed Senyk and Stsibors’kyi “by shooting them in the back on an open street.”[1119] The OUN-M used the murders to discredit the OUN-B, claiming that the two OUN-M members were killed by “Cain’s murderous hand from the ranks of the Banderite communist diversion.”[1120] In turn, the OUN-B blamed the Germans.[1121] The RSHA, however, arrested a number of OUN-B members for this killing and established a homicide division in Lviv, headed by Kurt Fähnrich, which investigated the murder. This suggests that the Germans did not kill the two OUN-M activists.[1122] According to German documents, the Ukrainian intelligentsia was outraged by the murders and demanded prosecution of the OUN-B.[1123]

The Germans realized that not all Ukrainians supported the OUN-B’s “Ukrainian National Revolution.”[1124] However, they also noticed that OUN-B activists organized meetings in many parts of Ukraine, collected signatures on appeals to release Bandera, and had a huge influence on the militia, mayors, and administration.[1125] The OUN-B was certainly popular in eastern Galicia and Volhynia, but it was unknown and sometimes even unwelcome in eastern Ukraine.[1126] Eastern Ukrainians were not interested in the ultranationalist, antisemitic, and racist ideology and identity that the OUN-B and other western Ukrainian nationalists propagated. The OUN-B activists who went with the task forces to eastern Ukraine were overwhelmed by the difference in the mentality of eastern Ukrainians. Some of them said that eastern Ukraine was beautiful but that it was not their homeland. They frequently romanticized eastern Ukraine in order to rationalize and accept it. One woman from an OUN-B task force claimed that “the theories of Marxism-Leninism destroyed the soul of the [eastern Ukrainian] nation” and observed that eastern Ukrainians were astonished when they saw OUN-B members praying in a group.[1127] The OUN-B’s posters, which propagated the political ideas of the organization, alarmed the Ukrainians in Kiev.[1128]

Many eastern Ukrainians did not speak Ukrainian. They spoke Russian or a mixture of Russian and Ukrainian. Many of them considered the Russian language to be more civilized than Ukrainian. When the OUN-B activists from the task forces came to central and eastern Ukraine, the population sometimes wondered about the language used by the OUN-B. Eastern Ukrainians preferred reading newspapers in Russian rather than in Ukrainian. Nove ukraїns’ke slovo was the only daily Ukrainian newspaper in the Reichskommissariat and sold poorly. Its forerunner Ukraїns’ke slovo had appeared without German censorship until 10 December 1941 and was more popular.[1129] Eastern Ukrainians sometimes mistook the OUN-B activists for Polish-speaking Germans. The OUN-B activists felt the need to convince the eastern Ukrainians that the OUN-B were also Ukrainians. This happened, for example, to Chartoryis’kyi from the third task force in the Podolian town of Fel’shtyn:

“We’re not Germans!” I explain. “We are your brothers, Ukrainians from the western lands—from Galicia,” I add to be on the safe side. … “We’ve come to visit you and to see if there’s anything we can help you with …”

“So there haven’t been any Germans here?” I ask again.

“No, only you ...”

“But we’re not Germans! We’re just like you. … Can’t you tell by our language?” I asked.

“Yes, it looks like even Germans can talk like us!” one of them answers.[1130]

The document “Instructions for Work with Workers from SUZ [Eastern Ukrainian Territories],” which was drawn up for the task forces that would go to eastern Ukraine, included the information that the eastern Ukrainians were not a different race. It also claimed that “it is difficult to draw a line that would mark where in [eastern] Ukraine a Ukrainian begins and a Muscovite ends” and that eastern Ukrainians had a “psychological Muscovite complex.”[1131] Ievhen Stakhiv went with a task force to eastern Ukraine to mobilize the masses for the “Ukrainian National Revolution.” He informed me in an interview in 2008 that he had realized that eastern Ukrainians were skeptical about and resistant to the OUN-B and its plans for a fascist and authoritarian state, and that it was impossible to win them over.[1132] On the other hand, Chartoryis’kyi of the third task force recalled in his post-war memoirs that some Ukrainians in villages close to Vinnytsia accepted the portraits of Stepan Bandera that the OUN-B members distributed at the propaganda meetings, and that some local Ukrainians even reproduced them.[1133] OUN-B member Pavlyshyn remembered that the local Ukrainians in one village near Zhytomyr thought at first that the OUN-B were Soviet partisans. The village teacher then warned the local people against the OUN-B task force: “Do you know who is standing before you, children? A remnant of Petliura’s army, a German agent. Our Budyonnyi’s army beat them, but didn’t finish them off. Get out of here!”[1134] The Germans noticed that eastern Ukrainians were different from western Ukrainians. They reported that the eastern Ukrainians did not understand “racist or idealistic antisemitism” because they “lack the leaders and the ‘spiritual drive [der geistige Schwung].’”[1135]

After Germany attacked the Soviet Union, another organization that tried to establish a state and applied terror toward Jews and other non-Ukrainians was the Polis’ka Sich, a paramilitary formation of Ukrainian nationalists under the leadership of Taras Bul’ba-Borovets’. This movement set up a “republic” in Olevs’k, a district center in the Zhytomyr region. The “republic” existed until November 1941, when Germans took over the administration. The streets in the area controlled by the Polis’ka Sich were renamed: one became “Polis’ka Sich Street”; another, “Otaman Taras Bul’ba Street.”[1136] The attitude of the Polis’ka Sich to Jews did not differ substantially from that of the OUN. They mistreated Jews and conducted pogroms during the summer of 1941. Together with local Ukrainian policemen and a German Einsatz-kommando, some members of the Polis’ka Sich killed many Jews in Olevs’k in a mass shooting on 19–20 November 1941.[1137]

After the “Ukrainian National Revolution” ended and the situation in Ukraine stabilized, the OUN-M took a different path from that of the OUN-B. The Germans did not ban it or persecute its members. On the contrary, it was the murder of OUN-M members Stsibors’kyi and Senyk that deteriorated the relations between the Germans and the OUN-B.[1138] Although the OUN-M tried not to worsen its relations with the Germans, a number of OUN-M activists were arrested, particularly in Kiev.[1139] The OUN-M did not organize an underground or an army like the OUN-B but tried to integrate its members into the administration. They were active in the UTsK and engaged in the organization of the Waffen-SS Galizien division.[1140] Mel’nyk, the leader of the OUN-M, and a number of other leading OUN-M members were arrested only in early 1944 when they tried to establish relations with the Allies.[1141]

Disagreement

The OUN-B proclaimed a state, and a significant number of western Ukrainians would have agreed to live in such a collaborationist state with Stepan Bandera as their Providnyk or Vozhd’, but Adolf Hitler, and some other Nazi leaders had other plans. In order to win their support for the fight against the Soviet Union, Alfred Rosenberg, Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories, wanted to give the non-Russians some degree of self-government, but Reichskommissar of Ukraine Erich Koch and several other high ranking Nazis, including General Governor Hans Frank, were against Rosenberg’s propositions.[1142] In the longer term the fate of Ukraine was to be regulated according to Generalplan Ost: Germans would be settled in Ukrainian territories, some Ukrainians would be enslaved, and the remainder “eliminated.”[1143] In practical terms the Germans were, however, dependent on the collaboration of the local population in order to control the occupied territories and to annihilate the Jews.

After Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union, the Germans forbade Bandera to leave Cracow for Lviv. Ernst Kundt, under-secretary of state in the General Government, organized a meeting in Cracow on 3 July 1941, in which Bandera and four other politicians from his newly proclaimed government took part. Bandera’s German was not fluent. Horbovyi—Bandera’s lawyer from the Warsaw and Lviv trials—was one of the four politicians and translated for him. Kundt informed his guests that the Ukrainians might feel like allies of the Germans, but they were not. The Germans were the “conquerors” of Soviet territory, and Ukrainian politicians should not behave in an irrational manner by attempting to establish a state before the war against the Soviet Union had ended. Kundt said that he understood the Ukrainians’ hatred toward the Poles and Russians, and the Ukrainians’ eagerness to build a state with a proper army. But if they wanted to remain on good terms with Germany and not to compromise themselves in the eyes of the Ukrainian people, they should “stop doing things” and wait for Hitler’s decision.[1144]

Bandera, who arrived late at the meeting, emphasized that, in the battle against the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian nationalists were “not passive observers, but active members, in the form that the German side allows them.” He explained that he had issued orders to his people to fight alongside the Germans and to establish a Ukrainian administration and government in German-occupied territory. Bandera tried to convince Kundt that the authority of the leader of the Ukrainian people came from the OUN, which was the organization that ruled and represented the Ukrainian people. He had tried to clear his policy with Abwehr officers, but they were not competent to resolve political questions of this nature. Kundt replied that only the Wehrmacht and the Führer were empowered to establish a Ukrainian government. Bandera conceded that such higher sanction had not been received, but a Ukrainian government was already in existence and its goal was cooperation with the Germans. He was not able to provide any evidence whatsoever of German approval and therefore emphasized that Ukrainian military chaplain Dr. Ivan Hryn’okh was present in a German uniform at the proclamation meeting on 30 June 1941 in Lviv.[1145]

The meeting ended with short monologues from each side. Kundt repeated that the proclamation of Ukrainian statehood was not in the German interest and reminded the Ukrainians that only the Führer could decide whether, and in what form, a Ukrainian state and government could come into being. The fact that the OUN-B had informed the German side of its intentions did not mean that the OUN-B had been allowed to proceed.[1146] Bandera admitted that he was acting with authority received from the Ukrainian people, but without the approval of the German side. Seeking reconciliation with Kundt, Bandera finally stated that he believed that only Ukrainians could rebuild their own life and establish their own state, but they could do so only with German agreement.[1147]

On 5 July 1941, Bandera was taken to Berlin and was placed in Ehrenhaft (honorable captivity), the following day.[1148] Stets’ko wrote to Bandera from Lviv, asking what he should do and whether he should inform the masses that the Providnyk had been imprisoned. He also encouraged Bandera to negotiate with the Nazis. Stets’ko survived an assassination attempt on 8 July but was arrested the following day. On the night of 11 July, Abwehr officer Alfons Paulus escorted him by train from Cracow to Berlin. Stets’ko was released from arrest on 12 July, as was Bandera on 14 July, both on condition that they report regularly to the police.[1149] They stayed together in an apartment house on Dahlmannstrasse in Berlin-Charlottenburg.[1150] In Berlin, Stets’ko wrote an autobiography for his interrogators, in which he repeated a point that he had made in his article “We and Jewry” in May 1939:

Although I consider Moscow, which in fact held Ukraine in captivity, and not Jewry, to be the main and decisive enemy, I nonetheless fully appreciate the undeniably harmful and hostile role of the Jews, who are helping Moscow to enslave Ukraine. I therefore support the destruction of the Jews and the expedience of bringing German methods of exterminating Jewry to Ukraine, barring their assimilation and the like.[1151]

While in Berlin, Stets’ko, the premier of the non-existent Ukrainian state, met the prime minister of the provisional government of Lithuania, Kazys Škirpa, who was brought to the German capital for reasons similar to those for Stets’ko’s arrival. On two occasions Stets’ko also met with the Japanese ambassador Ōshima Hiroshi. He was also allowed to go to Cracow, where he met Lebed’, and he was visited in Berlin by the OUN-B member Ivan Ravlyk.[1152] Bandera—the Providnyk of the non-existent state—stayed in Berlin, with identification papers from the RSHA, and a gun to defend himself. He could move in Berlin but was not allowed to leave the city.[1153]

In accordance with an order from Heydrich on 13 September 1941, a number of leading OUN-B members, including Bandera and Stets’ko, were arrested on 15 September, the reason for which was the assassination of Stsibors’kyi and Senyk on 30 August in Zhytomyr. This act had entirely changed the attitude of the Nazis to the OUN-B, who, according to the RSHA, “encouraged the Ukrainian population in Galicia and in the operative area [of the Germans] with extensive propaganda not only to resist the directives of German offices, but also to liquidate political enemies. Until now, over ten members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists under the leadership of Andrii Mel’nyk have been killed.”[1154] According to Lebed’ the Germans had the names and addresses of the leading OUN-B members from the OUN-M.[1155] Following their arrest, Bandera, Volodymyr Stakhiv, and other OUN-B members were first held by the Gestapo at their premises on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse,[1156] and Stets’ko at the Alexanderplatz prison.[1157]

At a meeting organized by Koch on 12 July 1941 in Lviv, all Ukrainian groups except for the OUN-B expressed loyalty to the German authorities. The OUN-B activists came to the meeting and wanted to discuss the questions of Ukrainian sovereignty and the release of their Providnyk. Koch informed them that only the Führer could decide these issues.[1158] According to Lebed’s autobiographical sketch from 1952, he, Iaryi, Shukhevych and Klymiv met with five German officers of the Wehrmacht, a few days after Stets’ko’s arrest. The German officers proposed to the OUN-B members to “improve cooperation on the basis of a transfer of administrative power [to the OUN-B] on the territory occupied by the Wehrmacht” if the OUN-B withdraws the “Declaration of Independence.” The OUN-B refused this proposition.[1159]

As early as the second half of July 1941, the Germans were trying to prevent the printing and distribution of OUN-B papers and other propaganda material.[1160] In late July, the OUN-B leaders in Galicia assured the German side that they were prepared to collaborate, although they were not pleased with the political situation.[1161] In August 1941, Klymiv reminded OUN-B members that the organization was not fighting against the Germans but was trying to improve relations with them, a statement that was reported to Berlin.[1162] At about the same time, the Germans discovered an inscription in Kovel’: “Away with Foreign Authority! Long Live Stepan Bandera!” This indicates that some sections of the OUN-B were ambiguous about Germany and that Bandera was becoming a symbol of opposition to the Germans, even if he himself wanted to collaborate with them.[1163] The German authorities dissolved the OUN-B militia and parts of the OUN-B administration and established a new administration, which, however, still included many OUN-B members.[1164]

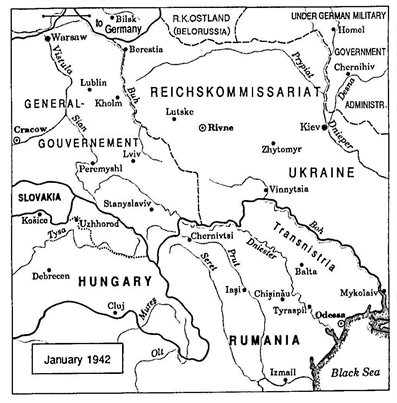

On 19 July 1941, Hitler decided to incorporate eastern Galicia as Distrikt Galizien into the General Government. A direction to this effect was given on 1 August 1941.[1165] Karl Lasch became the governor of Distrikt Galizien; Otto Wächter replaced him in January 1942. Volhynia and most of pre-1939 Soviet Ukraine became Reichskommissariat Ukraine, and were governed by Reichskommissar Erich Koch. Hitler’s decision of 19 July disappointed and frustrated many Ukrainian nationalists who had hoped that all Ukrainian territories would remain united in one political body (Map 5). They interpreted the incorporation of eastern Galicia into the General Government as incorporation into Poland. Bandera and Stets’ko protested in official letters to “Your Excellency Adolf Hitler.” The Providnyk asked the Führer to reverse the division and explained the situation by comparing the Ukrainian nationalists to the National Socialists from the eastern homeland (ostmärkische Heimat).[1166] Stets’ko informed Hitler that he hoped that this administrative division was only temporary. He claimed that the division pained the Ukrainian people, and he asked the Führer to “make up for the pain.”[1167] Sheptyts’kyi also objected,[1168] and Polians’kyi, OUN-B mayor of Lviv, even wanted to commit suicide.[1169]

Relations between the OUN-B and the Nazis were ambiguous until the assassination of Stsibors’kyi and Senyk on 30 August 1941. It was only after the assassination that the Nazis began arresting and shooting OUN-B members,[1170] and that the Gestapo closed the OUN-B offices in Vienna and at Mecklenburgische Strasse 73 in Berlin.[1171] In early October 1941 in Zboiska (near Lviv), Lebed’ organized the first conference of

Map 5. The Second World War in Ukraine, January 1942 – October 1945.

Encyclopedia of Ukraine, 5:726.

the OUN-B. The participants were impressed by the military successes of the Wehrmacht and were certain that Germany would win the war. They therefore decided that the OUN-B should not oppose the Germans but should go underground.[1172]

On 28 October 1941, a group of OUN-B members sent a letter to the Gestapo in Lviv. They stated that Hitler had deceived Ukraine and that America, England, and Russia would allow an independent Ukraine to arise, from the San to the Black Sea. “Long live a great independent Ukraine without Jews, Poles, and Germans,” they wrote and added: “Poles across the San, Germans to Berlin, Jews on the hook.” Finally, the authors stated that Germany needed Ukraine to win the war, and they demanded the release of imprisoned comrades.[1173] After 25 November 1941, the official policy of the Einsatzgruppen was to shoot OUN-B members in secret as looters, and a number of OUN-B members were killed by the Germans in various circumstances.[1174] In December 1941 the OUN-B announced that the Nazis had arrested 1,500 of their members.[1175]

In July and August 1942, 48 OUN-B members, among them Bandera’s brothers Vasyl’ and Oleksandr, were delivered to the concentration camp at Auschwitz. In October 1943, a further 130 OUN-B members were delivered to Auschwitz from Lviv. In the camp, they had the rank of political prisoners. They stayed in KZ Auschwitz I and worked where the chances of survival were good, such as the kitchen, bakery, tailor’s workshop, and storerooms for objects confiscated from new arrivals. They also received food parcels from the Ukrainian Red Cross. Some OUN-B members at Auschwitz were released in December 1944. Some were evacuated in January 1945 to other camps. Of the 48 delivered in 1942, 16 did not survive the camp. In total, more than 30 of the approximately 200 OUN-B members delivered to Auschwitz did not survive, including Bandera’s brothers, Vasyl’ and Oleksandr. The testimonies of the prisoners who survived the camp are ambiguous about the circumstances surrounding the death of Bandera’s brothers.[1176]

According to the OUN-B prisoner Petro Mirchuk, Vasyl’ and Oleksandr died as a result of mistreatment by a Polish Vorarbeiter (foreman) Podkolski, and Oberkapo Józef Kral, a few days after being delivered to Auschwitz. Both of Stepan Bandera’s brothers were mistreated because of their name, which was known to Podkolski and Kral from the Warsaw and Lviv trials.[1177] The Polish doctor Jerzy Tabeau, however, who worked as a nurse in Auschwitz, testified on 12 July 1964 at the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial that one of the Bandera brothers—he did not remember which one—died of diarrhea in the hospital for the prisoners in Auschwitz.[1178] Stepan’s third brother Bohdan was not arrested by the Germans. He apparently died in unknown circumstances in eastern Ukraine, where he had gone with an OUN-B task force after the German attack on the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941.[1179]

A few months before arresting the leading members of the OUN-B, the Germans had detained more than 300 members of the Romanian Iron Guard. The Romanian fascist movement, known as the Iron Guard, was founded in 1927 and first led by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu (1899–1938). His follower Horia Sima (1907–1933) allied himself with General Antonescu and for a short period of time they ruled Romania together, after King Carol II abdicated in September 1940. In January 1941 the conflict between Antonescu and Sima escalated. The Iron Guard legionaries tried to take over power but failed. Hitler decided to support Antonescu in order to secure Romanian support for the war. Over 300 legionaries fled to Germany where the Sicherheitspolizei detained and supervised them. In Romania about 9,000 legionaries were arrested at that time. When Sima fled to Italy in December 1942 from a camp in Berkenbrück near Berlin and asked Mussolini to support the Iron Guard, Hitler was so angry that, according to Goebbels, he first considered sentencing Sima to death. From early 1943 on, Romanian legionaries were detained in concentration camps in Fichtenhain, Dachau, Ravensbrück, and Sachsenhausen.[1180]

After being taken to Berlin in early July 1941, Bandera and Stets’ko offered much less resistance to the Nazis than nationalist historiography and Ukrainian nationalist propaganda portrayed. They tried to repair the relationship with the Germans, encouraged Ukrainians to collaborate with Germany, and tried to persuade the Germans that they needed and should keep the government established by Stets’ko. In an open letter dated 4 August 1941, Stets’ko encouraged Ukrainians to help the German army in its struggle against the Soviet Union and hoped that the Nazis would accept the Ukrainian state, when they eventually controlled all Ukrainian territories.[1181] On 14 August 1941, Bandera wrote to Alfred Rosenberg, Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories, explaining that he was prepared to discuss the German demand to dissolve the government proclaimed on 30 June 1941.[1182] On 9 December 1941, Bandera wrote in a memorandum to Rosenberg: “The Ukrainian nationalists believe that German and Ukrainian interests in Eastern Europe are identical. For both sides, it is a vital necessity to consolidate (normalize) Ukraine in the best and fastest way and to include it into the European spiritual, economic, and political system.” He again proposed collaboration and argued that the Nazis needed the Ukrainian nationalists, because only they could help the Nazis to “bring the Ukrainian masses spiritually close to contemporary Germany.” According to Bandera, the Ukrainian nationalists were predisposed to help the Nazis, because they were “shaped in a spirit similar to the National Socialist ideas.” Bandera also offered that the Ukrainian nationalists would “spiritually cure the Ukrainian youth” who lived in the Soviet Union.[1183]

In spite of Bandera’s propositions, Rosenberg and other leading Nazi politicians were not interested in discussing this and other related issues with him. Meanwhile, the Germans had begun to cooperate with other groups and individuals who were as eager as Bandera to help them. The OUN-B member Stakhiv wrote in his memoirs that when he visited Berlin in December 1941, Bandera gave him a message for Mykola Lebed’, his deputy in Ukraine, informing him that the OUN-B should not fight against the Germans but should try instead to repair German-Ukrainian relations.[1184]

Ukraine without Bandera

The Nazis did not want to collaborate with the hot-headed OUN-B but were interested in working with more moderate Ukrainian nationalists. In contrast to Jews and Poles, Ukrainians were a privileged ethnic group in the General Government. Unlike the Roman Catholic Church, the Greek Catholic Church in the General Government was not oppressed. The Ukrainian intelligentsia thrived in the General Government, where seventy Ukrainian periodicals existed, a government-sponsored school system became reality, and from where students were sent to study at German universities. The Ukrainian politicians tried to “entirely Ukrainianize” the Polish scholarly institute Ossolineum and the Technical University in Lviv. They thereby continued the Ukrainization that had already begun under Soviet occupation. The main cause of Ukrainian discontent in the General Government was the German drive for manpower for farms and factories in Germany. But the UTsK—the most important Ukrainian collaborationist institution—took care of it and convinced Ukrainians to support the German war effort and to work for the common cause.[1185]

Because the Germans wanted to win their loyalty, they applied liberal politics toward Ukrainians in the General Government and played them off against the Poles. Ukraine did not become an independent state as the Ukrainian nationalists wanted, but life for Ukrainians in Galicia under German occupation was not very different from the life of collaborating national groups in states like Slovakia or Croatia. In contrast, the policies toward Ukrainians in Reichskommissariat Ukraine were much harsher. The Nazis treated the Reichskommissariat as a colony and the Ukrainians there were simply to supply the Reich with grain.[1186] All universities were closed down and education was limited to four years of primary school.[1187] In two decades, Himmler planned to have a system of exclusively German cities at the intersections of highways and railroads in the Reichskommissariat.[1188] Because the Ukrainian territories were to be settled with Germans and some Ukrainians were to be enslaved and others “eliminated,” the Nazis regarded the eastern Ukrainians simply as a labor force. If they were not productive or became “superfluous,” they could be starved to death or shot. Erich Koch, head of the Reichskommissariat, claimed that “if this people works ten hours daily, it will have to work eight hours for us.”[1189] Apart from work, Hitler said that he would allow only music for the masses and religious life in Reichskommissariat Ukraine.[1190]

From April 1940 until January 1945, the head of the UTsK, the most important Ukrainian collaborationist institution in the General Government, was Volodymyr Kubiiovych. Prior to the Second World War, Kubiiovych had socialized with members of the OUN in Berlin.[1191] Their goals and political views did not differ greatly but he was more cautious and diplomatic. In April 1941, Kubiiovych asked Hans Frank, head of the General Government, to set up an ethnically pure Ukrainian enclave there, free from Jews and Poles.[1192] In July 1941, on the initiative of the OUN, Kubiiovych asked Frank for a “Ukrainian National Army” or Ukrainian Wehrmacht, which would fight alongside the German Wehrmacht against the Red Army and the “Jewified English-American plutocracy” (verjudete englisch-amerikanische Plutokratie).[1193] In August 1941, Kubiiovych asked Frank to have “a very significant part of confiscated Jewish wealth turned over to the Ukrainian people.” It belonged to Ukrainians and had ended up in Jewish hands “only through a ruthless breach of law on the part of the Jews, and their exploitation of members of the Ukrainian people.”[1194] He thereby used arguments similar to those of Father Josef Tiso and Marshal Ion Antonescu.[1195] The UTsK was obviously pressing for aryanization at all administrative levels.[1196]

The UTsK was associated with the collaborationist newspaper Krakivs’ki visti, which not only republished German propaganda but also encouraged Ukrainian intellectuals to express antisemitic views. In 1943 Bohdan Osadczuk and Ivan Rudnyts’kyi, who would become prominent Ukrainian intellectuals after the Second World War, published articles in Krakivs’ki visti on the NKVD massacres in Vinnytsia in 1937–1938. The campaign in Krakivs’ki visti instrumentalized the Ukrainian victims of the Soviet terror in Vinnytsia in order to mobilize Ukrainians to fight against the Soviet Union. Osadczuk, who covered the German, Ustaša, and other press for Krakivs’ki visti, wrote in August 1943: “The mass graves in Vinnytsia, Hrvatski Narod states, are new proof of the politics of destruction that the Jews from the Kremlin have conducted among the Ukrainian people. The murdered Ukrainians again throw guilt on Stalin and his Jewish collaborators and summon the world to an implacable struggle against the Jewish-Bolshevik threat, which would like to bring upon Europe the same fate that the defenseless victims in Vinnytsia met.”[1197] Rudnyts’yi called the victims of the Soviet terror the “real martyrs for the Ukrainian national idea.”[1198]

During the entire period of German occupation, antisemitism was popular in Ukraine, not only in the “anti-German” nationalist underground but also among many organizations and intellectual circles. In 1941 the brochure “Ukraine in the Claws of Jews” was published. This unsigned German-Ukrainian production contained all kinds of antisemitic stereotypes that were applied to the Ukrainian situation.[1199] In June 1944, Kubiiovych was invited to take part in an anti-Jewish congress planned by Hans Frank.[1200]

In early 1943, Himmler ordered the establishment of a Waffen-SS Galizien division, made up of Ukrainian soldiers, but forbade it to be called Ukrainian. In a speech on 16 May 1944, Himmler claimed that he had called it Galician “according to the name of your beautiful homeland.” He also made comments such as “I know if I ordered the Division to exterminate the Poles in this area or that area, I would be a very popular man.” Hitler justified the Ukrainian division with the assumption that Galician Ukrainians were “interrelated” with Austrians because they had lived for a long time in the Habsburg Empire. The full name of the Waffen-SS Galizien division was the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (14. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS). Of the 80,000 Ukrainians who volunteered for it, only 8,000 were recruited. After Ukrainians from police battalions and other units joined the division, the Waffen-SS Galizien grew to 14,000 soldiers. A significant number of the men who joined the Waffen-SS Galizien had served in Schutzmannschaft battalions 201, 204, and 206, of which at least battalion 201 almost certainly perpetrated atrocities against civilians in “anti-partisan operations” in Belarus. Other recruits had served in the German security police in western Ukraine. Ukrainians in the Waffen-SS Galizien were trained and indoctrinated by Himmler’s SS. They had two hours of education in National Socialist Weltanschauung every week. In August 1943, the soldiers of the Waffen-SS Galizien received blood group tattoos in their left armpits, and 140 men of the division were given additional training in the vicinity of Dachau concentration camp. The soldiers of the Waffen-SS Galizien took the oath: “I swear by God this holy oath, that in the struggle against Bolshevism, I will give absolute obedience to the Commander-in-Chief of the German Armed Forces, Adolf Hitler, and if it be his will, I will always be prepared as a fearless soldier, to lay down my life for this oath.”[1201] It was as late as February 1945 that Pavlo Shandruk, the Ukrainian general of the division, asked the Germans to allow an amendment to the text of the oath. He proposed to add “and the Ukrainian people” but he did not ask to have Hitler’s name removed.[1202]

The establishment of the division was supported by Sheptyts’kyi. At its first parade, Frank and Kubiiovych took the first salute, and Bishop Iosyf Slipyi performed a religious service. In his speech, Kubiiovych appealed to the division to protect Ukraine against communism, as part of the “New Europe.” Vasyl’ Veryha, a veteran of this division, mentioned in his memoirs that Ukrainian policemen greeted the Waffen-SS Galizien soldiers with “Heil Hitler!” and that the response was “Glory to Ukraine!” (Slava Ukraїni!). He did not specify whether the soldiers and policemen raised their right arms. The Waffen-SS Galizien was established to fight against the Soviet army and did so near Brody in July 1944. Shortly before it was officially included in the division, members of the fourth SS police regiment, which consisted of Ukrainians, had murdered several hundred Polish civilians in Huta Pieniacka on 28 February 1944. According to testimony by UPA partisans, the SS police regiment was supported by UPA freedom fighters when they exterminated the Polish village population. In Slovakia, where the Waffen-SS Galizien helped the Germans to suppress the Slovak National Uprising, individuals from the Waffen-SS Galizien may have committed crimes against civilians as well. Two days after the end of the Second World War 1945, the division surrendered to the British Army. On the grounds that they were Polish citizens and with the intervention of the Vatican, soldiers from the division were not handed over to the Soviet Union, as Vlasov’s Russian Liberation Army (Russkaia osvoboditelnaia armiia, ROA) soldiers were.[1203]

The Ukrainian Police and the OUN-B

In accordance with a directive from Himmler in July 1941, the Ukrainian militia, which had been established by the OUN-B after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, was redeployed in August and September 1941 as a Ukrainian police force, known as Hilfspolizei and Schutzmannschaften.[1204] The Germans generally tried to purge the police of OUN-B members, because they needed people who would carry out orders without pursuing their own political purposes. Nevertheless, many OUN members remained in the police, concealing their association with the OUN-B. Volodymyr Pitulei, commander of the Ukrainian police retained many OUN members in the police force, despite the German order to replace them. Some local German officials transferred additional OUN-B militiamen to the Hilfspolizei, not knowing that they were members of or sympathizers with the OUN, or for practical reasons. As a result many OUN-B and also OUN-M members remained in the police and in the course of the following weeks and months many more joined it. According to the OUN-B member Bohdan Kazanivs’kyi there were even many OUN-B members among the commandants of the police school in Lviv in which new policemen were recruited.[1205] In March 1942, the OUN-B local leaders issued orders to their members to join the police en masse. They tried to have at least one OUN-B member in every police unit, in order to control the police force.[1206] The OUN-B also tried to replace OUN-M members in the Schutzmannschaften with its own people.[1207] In early 1943, the “Eastern Bureau” of the Polish government-in-exile reported that “the main organizational core [of the OUN-B] in Volhynia is the approximately 200 police stations.”[1208] The influence of the OUN-B on some of the Ukrainian police was also noted by the Germans.[1209] Eliyahu Yones, who worked in the slave-labor camp Kurowice, wrote in his memoirs that the Ukrainian policemen at his camp were Ukrainian nationalists who were proud to wear blue uniforms and Ukrainian caps.[1210]

In spring 1942, there were over 4,000 Ukrainian policemen in the General Government.[1211] In 1942 in Volhynia, there were 12,000 Ukrainian policemen and only 1,400 Germans.[1212] In terms of violence and antisemitism, the new Ukrainian policemen in the General Government and Volhynia were not very different from the previous Ukrainian militiamen. Eliyahu Yones was seized on 12 November 1941 by Ukrainian policemen in Lviv. After he was beaten and robbed by them, a German officer asked him some questions concerning his occupation. Together with other Jews, Yones then had to stay with his face to the wall, and hands on the wall, for several hours. During this time, the Jews were further beaten and humiliated. After several hours they were driven by truck to a bathhouse, where they had to hand over the rest of their belongings and then:

In the evening, the light was switched on [in a hall of the bathhouse]. Suddenly, we received a new order: “sing.”

In the middle of the hall, many Ukrainian men gathered and later, Ukrainian women also came. They took delight in the singing and it was obvious that they looked forward to the upcoming events.

The Ukrainians mistreated us until the morning hours. Their disgraceful deeds culminated in their taking an old Jew from the row, who kept a big book in his hand, a Gemarah, which he read. They ordered him to put the book on the floor, to step on it, and to dance a Chasidic dance on it. At first he refused, but finally they forced him, while heavily beating him. He began dancing when the Ukrainians around him beat him; they accompanied his dance with cheers.

Then they sat him on the floor and lit his beard, but the beard did not burn. While some Ukrainians experimented with his beard, others took six Jews with beards from our rows, put them next to the old one and also lit their beards. At first the beards burned, but then the fire sprang on the clothes, and the Jews burned to death in front of us. …

The Ukrainians continued their mistreatment. They took from our row a deaf Jew who was bald. His head was their target. They threw against him bath devices made from metal and wood. The competition finished soon, as the head of the deaf man was shot into two parts and his brain flew on his clothes and the floor.

There was a Jew with a crooked foot. The Ukrainians tried to straighten it by force. The Jew screamed loudly, but they did not succeed. They were busy with the straightening of this foot until they broke it. The Jew did not stand up again, probably because his heart was broken as well.

Trembling, we were forced to accompany these mistreatments with singing, and as a reward, we were beaten terribly. …

We were beaten the whole night. In the morning I was one of the twenty-three who survived of a group of about 300 who had come here the previous day. Most were killed by uninterrupted beating.[1213]

Of the twenty-three survivors, twenty died during the following hours and days on account of the injuries they obtained during the night in the bathhouse.[1214] This description of the deeds of the Ukrainian policemen represents only a very small part of what they did to the Jews while patrolling the ghettos and assisting the Germans with deportations, raids, and shootings. In rural areas, there were few if any German policemen and authority was almost entirely in the hands of the Ukrainian police and the local Ukrainian administration.[1215] Holocaust survivor Rena Guz remembered how Ukrainian policemen in the Povorsk (Powórsk) region in Volhynia severely beat Jews, forced them to dance naked, and escorted a group of Jews from the ghetto to the forest, where they made them dig a grave, and then shot them.[1216] Bohdan Stashyns’kyi, from the town of Borshchovychi (Barszczowice), close to Lviv, witnessed the prominent role of the Ukrainian Hilfspolizei in the shooting of Jews in his district on several occasions.[1217] Like the Polish Kripo (criminal investigation department), the Ukrainian Hilfspolizei was responsible for hunting down and killing Jews who escaped from the ghettos and were hiding in the forests. In western Ukraine, the Ukrainian police shot hundreds or perhaps thousands of Jews who tried to survive in the forest or who hid in the villages.[1218]

Many Jews were murdered in Ukraine during the second half of 1942 in particular, as the ghettos were dissolved at that time. Some of the Jews in eastern Galicia (Distrikt Galizien of the General Government) were deported to the Bełżec extermination camp in the course of the Aktion Reinhardt; others were shot. In Volhynia (Reichskomissariat Ukraine) the Jews were shot by units composed of the Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police) and Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service) near the ghettos or in local forests and fields; they were buried in mass graves dug by Soviet POWs (Prisoners of War), local peasants, Ukrainian policemen, or the Jewish victims themselves. The annihilation of the largest number of Volhynian Jews finished in December 1942, and of eastern Galician Jews in July 1943. Dissolving the ghettoes and assisting the Germans by shootings, the Ukrainian policemen seem to have been, in general, no less brutal and eager than the German police or Gestapo officers. For example, during a mass deportation of Jews from the Lviv ghetto in August 1942, a Ukrainian officer of the Hilfspolizei complained that members of Organization Todt obstructed him in completing his duties.[1219]

The role of the Ukrainian police in mass shootings was also a significant one. They helped the Germans identify the Jews with the help of lists that had sometimes been prepared by the local Ukrainian administration or by ordinary Ukrainians—frequently their former neighbors. Then the Ukrainian policemen escorted the Jewish victims to the mass graves, and ensured that the Jews did not escape from the execution site, where they were usually shot by Germans and occasionally by Ukrainian policemen.[1220] In his study on the Holocaust in Volhynia Shmuel Spector cited the description of one of the numerous shootings which happened before the Jews had been moved to the ghettos. The description was left by a survivor who had lost her relatives during this massacre. On the afternoon of 12 August 1941,

Two truckloads of Ukrainian policemen and the Gestapo murderers entered the townlet [of Horokiv in Volhynia]. Within minutes all the Ukrainian youth, which probably had prepared itself in advance, enlisted itself to assist them. For about two hours some 300 men, including children aged 14, were seized in the streets or driven from their homes. In searching for and finding the Jews, the Ukrainian youths demonstrated such diligence and energy that no description can do justice to the ignominy of this people.

The Germans did not take part in the abductions. This was carried out with clear conscience by our Ukrainian neighbors who had lived side by side with the Jews for generations. High school students, sons of the nation of murderers, came to drag out their fellow Jewish students. Within minutes, neighbors who for many years had lived next to a Jewish house, became beasts of prey pouncing on their Jewish neighbors. Within a short time the unfortunate victims, my husband, my brother and my brother-in-law, were assembled in the yard of the militia post where they were kept for several hours.

In the meantime a group of men was led to the Park where they were ordered to dig up a large pit. As soon as the digging was completed, they began bringing the unfortunate victims in groups. They were not yet aware of what awaited them. The Ukrainian militia performed its job splendidly. No one among the unfortunates managed to get away. The job of shooting was performed by the German murderers, whose superior training prepared them for it. At six o’clock in the evening the whole thing was over.[1221]

In some places, however, the Ukrainian police did not only escort and watch but also participated in the shooting. On 6 September 1941 in Radomyshl’, the Ukrainian police assisted Sonderkommando 4a, which shot 1,107 adult Jews. The Ukrainian police themselves shot 561 Jewish youths.[1222] During an NKVD interrogation in July 1944, Iakov Ostrovs’kyi stated that, during two shootings, 3,300 Jews were annihilated. Of these, 1,800 were killed by the Germans and 1,500 by the Ukrainian police.[1223] According to Stanisław Błażejewski, the Ukrainian policeman Andryk Dobrowolski from Małe Sadki in Volhynia boasted that he personally killed 300 Jews.[1224] Joachim Mincer wrote in his diary in 1943 that the “executions in the prison yard” were conducted “mainly by Ukrainian policemen.” He identified the main persecutor as a policeman by the name of Bandrowski who “liked to shoot Jews on the street.”[1225]

From the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 until the summer of 1943, the Ukrainian militiamen and later the Ukrainian policemen learned how to annihilate an entire ethnic group in a relatively short time. Some of them made practical use of this knowledge when they joined the UPA at the request of the OUN-B, in spring 1943.[1226] In March 1943, the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa, AK) observed that Ukrainian policemen in Volhynia sang the words, “We have finished the Jews, now we will do the same with the Poles” and that their economic situation improved during the process of helping the Germans kill the Jews of Volhynia.