‘Fat is one of the most fascinating organs out there . . . we are only now beginning to understand fat.’

Dr Aaron Cypess, Harvard Medical School1

THINK ABOUT FAT and what image comes to mind?

Perhaps a lump of shiny white lard, the orange grease soaked into the cardboard of a discarded pizza box, or maybe the congealing sludge you pushed to the side of your plate in disgust as a child?

When it comes to humans, fat is often seen as the outward manifestation of gluttony and greed; as Nature’s punishment for the sin of overindulgence, visited upon the guilty in the shape of beer bellies, muffin tops, love handles, dimpled thighs, bulging waists and flabby buttocks. It is something to agonise over and ‘burn off’ by means of rigorous dieting and vigorous exercising.

To regard fat in this way is, however, to do an exquisitely complex and vital organ a considerable injustice. Over the past thirty years, scientists have come to appreciate that it is far from being simply an inert storehouse for energy. Like the heart, brain, liver, and kidneys, fat is a living, metabolically active organ.2 It produces and secretes a variety of powerful hormones into the bloodstream and is in constant communication with every other part of the body. What fat ‘says’ during these exchanges, and how its messages are received, is no less important than lifestyle choices in determining whether we stay slender, put on weight or become obese.

Fat, or adipose tissue, consists primarily of cells called adipocytes (also known as lipocytes), which specialise in storing energy. There are also a smaller number of other cell types in fat, including those from which adipocytes evolve, called preadipocytes and fibroblasts, which form the basic structure of cells and tissues. There are two types of adipocytes, named white and brown fat due to their respective appearances. Of these, White Adipose Tissue (WAT) is present in the greatest quantities in a human body, and plays the more significant role in weight gain.

In the late 1980s, Pentti Siiteri, a biochemist at the University of California, San Francisco, known to friends and colleagues as ‘Finn’, identified adipose tissue as an endocrine organ.3 Derived from the Greek endo, meaning ‘inside’ and krinein meaning ‘secrete’, such systems comprise the glands, cells and tissues which metabolise and exude a wide variety of hormones directly into the bloodstream.

The interactions between hormones and their target cells might be likened to software programs. By regulating metabolism and modulating reactions to different foods they run our bodily processes. While we cannot consciously control hormonal responses, for example by instructing the pancreas to release more insulin, we can and do exert significant influence over them via our behaviour; by the amount and intensity of the exercise we take, the quality of our sleep, the amount of stress we experience and by what we eat.

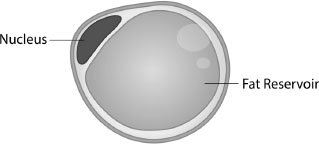

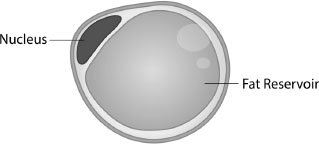

Hormones produced by white adipose tissue (WAT) play a critical role in metabolism by balancing energy needs and controlling the cell’s sensitivity to insulin.4 Its colour, and hence its name, derives from the fact that each cell consists of a large drop of pure white lipid (liquid fat made up of triglycerides and cholesterol ester) surrounded by a membrane. The average adult has around 30 billion white fat cells, accounting for around 20% of male and 25% of female body weight. This fat gobbet takes up so much space that the cell’s nucleus is squeezed into a thin rim around the periphery (See Figure 5.1).

In a person of normal weight, WAT cells have a diameter of around 0.1 micron, but are capable of expanding by up to four times their normal size when storing excess fat. If they become too large they can divide and so increase the number present in the body. This, however, only seems to occur during childhood and adolescence. It’s not that overweight adults have more fat cells; theirs are just larger.

White Adipose Tissue serves four key functions:

1) It provides thermal insulation, enabling the body to maintain core temperature within very close limits.

2) It produces hormones that control metabolism and some aspects of sexual activity.

3) It stores excess calories and releases them when hunger strikes. It does this in response to insulin, produced by beta cells in a region of the pancreas called the Islets of Langerhans.5

4) It plays a critical role in inflammation, the body’s response to stress. Inflammation of fat cells is one of the key stages in the development of Type II diabetes, which has made the role of inflammation and fat a key priority in obesity and diabetes research.6

WAT is found in various locations around the body, but precisely where it is deposited varies according to sex and age. Women tend to accumulate it on their hips, legs, and buttocks, while men store it mainly around their waist. Researchers term the resultant pear shape in women as gynoid and the resultant apple shape in men as android. There is also a third shape, termed androgynous, where the overall distribution of fat is neither typically male nor typically female but somewhere between the two, leading to a more rectangular shape.

Excessive WAT around the abdomen, termed visceral fat, poses a far greater risk to health than fat stored beneath the skin. While hormones secreted subcutaneously circulate to every part of the body, those produced by visceral fat cells flow into the portal artery and travel directly to the liver, where they can cause serious damage.

Unlike in cowboy movies, where the man in white is always the good guy, in our body it is white fat that is the villain – when either deficient or present in excess, that is. Too much white fat is associated with a wide range of diseases, and associated with metabolic syndrome. The term metabolic syndrome (MetS) describes a cluster of health problems that emerge in response to the body’s inability to cope with excessive fat tissue, problems such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and chronic inflammation. Yet, a lack of adipose tissue is not desirable either; although extremely rare, lipodystrophy is a condition marked by an individual’s inability to store fat appropriately. Curiously, the same problems associated with obesity ensue; an individual who suffers from this condition often has problems with insulin resistance and a fatty liver.7

Adipocytes produce a variety of hormones, referred to collectively as adipokines or adipocytokines. Adeps is the Latin for fat, kytos the Greek for container (in this case, a cell), and kinein Greek meaning ‘to move’. Metabolic syndrome develops when adipokine secretion runs out of control, leading to such obesity-linked problems as inflammation, elevated lipid levels (hyperlipidemia) and vascular disease – all risk factors in heart disease – and Type II diabetes, previously summarised. Three of the most important adipokines are resistin, adiponectin and peptin.

First identified in 2001 by endocrinologist Mitchell Lazar and his team at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, resistin’s main role is in regulating metabolism.8 Levels of resistin in the blood have been shown to rise in conjunction with an increase in white adipose tissue around the waist, and to decline when weight is lost.9 Increased levels are also associated with a rise in diabetes risk; its name refers to a suggested link to insulin resistance. Currently, however, this idea has not received general acceptance in the scientific community.

Resistin has been demonstrated to cause high levels of bad cholesterol (low-density lipoprotein or LDL) in the human liver and also to degrade its LDL receptors. As a result, the liver is less able to clear ‘bad’ cholesterol from the body. Resistin also accelerates the accumulation of LDL in the arteries while adversely affecting the impact of statins, the main cholesterol-reducing drug used in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Discovered by four independent groups of researchers, in the mid-1990s, adiponectin is known to the scientific community by a variety of names – Acrp 30 (adipocyte complement related protein of 30 kDa), apM1 (adipose most abundant gene transcript 1), adipoQ and GBP28 (gelatin binding protein). Manufactured by a gene located on a chromosome which is reported to have a link to obesity (chromosome 3q27), its function is to regulate fat and glucose metabolism.10 Adiponectin levels vary in inverse relation to obesity, which has naturally caused significant interest among obesity researchers.

Adiponectin plays a role in the diseases present in the metabolic syndrome. Low levels of adiponectin in the blood, which are found in around a quarter of the population, are associated with insulin resistance, Type II diabetes, coronary artery disease, vascular disease, hypertension and obesity.11

Koji Ohashi and his colleagues at Osaka University’s Graduate School of Medicine and the Molecular Cardiology Whitaker Cardiovascular Institute at Boston University found that in mice, low adiponectin levels were associated with a rise in systolic blood pressure. When levels were topped up, the pressure declined. ‘These data suggest,’ reports Koji Ohashi, ‘that . . . low production of adiponectin might relate to the pathophysiology of hypertension.’12

Mother’s milk contains large amounts of adiponectin, which might explain the finding that babies who are breastfed have a reduced risk of obesity later in life. We will also have more to say about the crucial importance of human milk in the next chapter where we describe its vital role in the growth of gut bacteria.

Because adiponectin acts directly on the brain, its effects are rapid and profound. When, in 2004, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine injected it into mice, the rodents lost weight, not because their appetites had been curbed but because their metabolic rate had been increased. ‘The animal burns off more calories, so over time loses weight,’ wrote Rexford Ahima, then Assistant Professor of Medicine at Penn. Diabetes Center. ‘Here we have another fat hormone that can cause weight loss but without affecting intake.’13

While studying diabetes, Professor Philipp Scherer and his colleagues at the University of Texas in Dallas worked with a group of mice that had been genetically engineered to secrete about three times the normal amount of adiponectin, limiting the amount reabsorbed by the body. As a result these animals ate so voraciously they almost doubled their weight within just a few months. The one thing they singularly failed to do, despite their obesity, was become diabetic.

‘The continual firing of adiponectin generated a “starvation signal” from fat that says it is ready to store more energy,’ explains Professor Scherer. ‘The mice became what may be the world’s fattest mice, but they have normal fasting glucose levels and glucose tolerance.’14

The million-dollar question was – why?

The answer came when Philipp Scherer and his team examined the way body fat had been deposited in the mice. While they found an abundance stored directly beneath their skin, there was very little in organs such as the liver. This led them to speculate that the unusual distribution might explain why the grossly overweight animals remained in such good health. Excessive fat in the liver can make the organ less sensitive to insulin, which as we have already discussed can lead to diabetes. ‘This indicates,’ writes Scherer, ‘that the inability to appropriately expand fat mass in times of overeating may be an underlying cause of insulin resistance, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.’

This discovery also suggested that the subcutaneous fat cells in individuals with low adiponectin levels failed to signal that they were ready to accept more fat. Adiponectin may also play a vital role in directing where fat is stored and this, in turn, plays a crucial role in the development of pathologies associated with metabolic syndrome. The mice that secreted high levels of adiponectin had fat reserves in all places in their body apart from their organs. Thus, adiponectin may protect an individual from cumulating fat in locations more hazardous to health, such as the liver, heart and muscle tissues. It is not just how much fat is being stored but where it is deposited that makes a difference between health and disease. ‘It is a little bit like real estate,’ remarks Scherer, ‘location, location, location.’15

The story of leptin begins with the world’s fattest mouse and ends with a discovery that forever changed the way scientists view obesity. It started in 1958, at the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine. This low-storey, red brick biomedical research centre can fairly be described as the kingdom of the mouse. Not only has the lab sequenced the entire mouse genome, it also produces more than 5,000 strains of genetically modified mice which are used in medical research all around the world. However, of the 5,000 strains known to scientists as the Jackson, or JAX, mouse, one strain in particular is among the most intensively researched and academically famous rodents of all time, having been used to gain a better understanding of obesity and diabetes.

It was in 1958 that a 27-year-old biochemist named Douglas Coleman joined the Jackson Laboratory. He was intending to stay for just a couple of years, but was to remain there for his entire professional career. The laboratory, he later explained, ‘provided a rich environment, including world-class animal models of disease, interactive colleagues, and a backyard that included the stunning beauty of Acadia National Park.’16

Coleman took his first degree, in chemistry, at McMaster University, where he also met his future wife: ‘the only girl to graduate in chemistry in the Class of 1954’, then went on to complete a PhD in biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin. His early researches were into muscular dystrophy and the newly emerging field of mammalian biochemical genetics. He had little or no interest, at that time, in studying obesity. Then, in 1965, something unexpected happened in the mouse colony at the Jackson Laboratory, a chance event which was to change his professional life forever and set in motion research that was to occupy him for much of the next thirty years.

A massively obese mouse was born.

When Coleman first started working there, the Jackson Laboratory was already home to what was then the world’s most important murine strains, known as the obese mutant mouse. Named the ob/ob mouse (‘ob’ stands for obese), it was the result of a chance genetic mutation. Seven years later a second spontaneous mutation occurred producing a second strain of obese mice. Like the ob/ob mouse, these animals ate voraciously and grew rapidly but, unlike the ob/ob mice, they also suffered from Type II diabetes. This, as we saw in Chapter 4, is caused either by the pancreas failing to manufacture sufficient insulin or because the cells of the body have become resistant to it. Obesity in this second strain was found to have arisen as the result of two defective copies of a gene, which researchers dubbed ‘db’ for diabetes, leading to them being named db/db mice.17 The ob/ob and the db/db mice appeared outwardly identical to an observer, in terms of both looks and behaviour.

Douglas was given the task of discovering what the precise biological difference was between these outwardly similar mice. The fact that both strains were morbidly obese led him to wonder whether these similarities might be due to a common factor circulating in their blood. To test this theory he performed an operation, known as parabiosis, in which he surgically attached a db/db to a normal mouse in such a way that they shared the same blood supply. Within a week, despite the animals being given all they wanted to eat, the normal mouse was dead. It had perished not as a result of surgical complications but from starvation. Its Siamese twin partner, the db/db mouse, had not only survived but also grown even fatter. Douglas repeated the experiment on numerous occasions with exactly the same outcome. Each time, after about seven days, the blood glucose concentrations in the normal mice had fallen to starvation levels.

‘The normal mice not only consistently lacked food in their stomachs and food remnants in their intestines but also had no detectable glycogen in their livers,’ Douglas Coleman recalls. ‘In marked contrast, the diabetes partners consistently retained elevated blood sugar concentrations, and their stomachs and intestines were distended with food and food residues.’18

When he performed the same surgery on two genetically normal mice, however, both remained well and active for months afterwards. At which point he experienced what he later called his ‘Eureka!’ moment.

‘These results led me to conclude that the db/db mouse produced a blood-borne satiety factor so powerful that it could induce the normal partner to starve to death.’19 There was something in the blood of the db/db mice that told the bodies of the normal mice that they were full and required no extra energy when, after a few days, precisely the reverse was true.20

Despite these clear results, many of his colleagues, as well as researchers in other laboratories, refused to accept them. They remained firmly wedded to the prevailing doctrine that obesity was a consequence of lifestyle, not hormones; that it was overwhelmingly due to the fact that overweight people ate unhealthily and exercised infrequently, if at all. Over the next few years, however, more and more researchers came around to the view that obesity also had an underlying physiological cause.

The hunt for the satiety factor then became a race. Drug companies knew that, if it could be found and marketed as the ultimate slimming pill, it would make a fortune. After all, the US weight-loss industry alone produces annual revenues in excess of $20 billion.21

Over the next few years many possible candidates were suggested as the satiety factor (cholecystokinin, somatostatin and pancreatic polypeptide, for example). However, after rigorous experimentation, each was discarded.

The breakthrough was finally made not in Douglas Coleman’s Bar Harbor laboratory, but a short flight down the East Coast in New York City. At 5.30 on the morning of 8 May 1994, Jeffrey Friedman, a forty-year-old molecular geneticist at Rockefeller University, identified the factor and the gene that produced it.

‘It was astonishingly beautiful’, he says, talking about the X-ray film that identified the gene involved. It is an image that now takes pride of place on the wall of his office.22

Jeffrey Friedman never intended to be a researcher. He wanted, and expected, to follow his father into medicine. Born in Orlando, he spent most of his childhood in Long Island, New York, where his father practised as a physician. ‘The world of my parents’ parents was essentially the world of immigrants,’ he says. ‘And in that world, you did whatever you could to get your feet on the ground. And in my family, the highest form of achievement was being a doctor.’

So, young Jeffrey set out to study medicine. Despite doing extremely well at school, this did not prove an easy ambition to realise. After receiving rejections from seven colleges, he was finally accepted on a six-year programme at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and Albany Medical College of Union University in upstate New York. An MD by the time he was twenty-two, Jeffrey then began a residency at Albany Medical Center Hospital, with no concrete plans about how to spend a gap year between leaving that job and embarking on a fellowship at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

‘One of my professors thought I might like research,’ Jeffrey remembers. ‘Why he thought I might have some particular aptitude, I can’t really tell. He said, “I have this friend at Rockefeller, why don’t you go spend a year with her and see if you like research?” I didn’t know what else I was going to do. My mother thought I should go spend the year as a ship’s doctor!”23

Rejecting her advice, Jeffrey joined the laboratory headed by Professor Mary Kreek and almost immediately fell in love with her research into the way molecular biology could provide a road map for understanding behaviour.

‘That was 1981 and it was beginning to be evident that molecular biology was going to have a big impact, so instead of going to the Brigham for a fellowship, I abandoned medicine and decided to get a PhD with Jim Darnell . . . one of the leaders in molecular biology.’24

Though he did not know it, Friedman was giving himself all the preparation he needed to make one of the most important discoveries in the history of obesity – and biological – research. Soon after establishing his own laboratory at Rockefeller in 1986, Friedman started to hunt for the elusive satiety factor. It proved a long and difficult search, requiring many years of meticulous experimentation. ‘Today, it would take about a week to do what we did in the lab,’ Friedman told us. ‘Back then, it was a process of about eight years.’25

He described to us how, late one Saturday night, he was looking at blots with RNA (ribonucleic acid)fn1 from the fat tissue of normal and mutant mice. Blot analysis is a method for transferring biological material, such as protein, DNA or RNA onto a cell membrane. The chemical reaction is registered on photographic film, providing scientists with a way to determine the gene expression levels of particular genes.

After preparing a blot while investigating a new, unknown hormone, he went home but, unable to sleep, got up at around five in the morning, returned to his bench and developed the blot. What he saw made him almost pass out in surprise.

‘When I looked at the data, I immediately knew that we had cloned ob, that is, the gene which had made the first JAX mouse so fat in the first place. When I saw it, I was in the darkroom, and I pulled up the film and looked at it under the light and got weak-kneed. I sort of fell backwards against the wall. This gene was in the right region of the chromosome, it was fat specific, and its expression was altered in two independent strains of ob mice.

‘Before this, we didn’t know where ob would be expressed – and while fat was one of the tissues I considered, in principle the gene could have been expressed in any specialized cell type anywhere that had no obvious relationship to fat. But, on the other hand, seeing a gene in the right region expressed exclusively in the fat . . . that gets your attention. We saw RNA in the normal animal – but a ten times increase in fat from the mutant animal? At first that might be puzzling, but that’s when I knew we had identified a gene. The fact that one animal didn’t make any RNA, and the other showed an increase in RNA, meant there had to be a change in genetics.’

At six in the morning Friedman telephoned his wife and, wild with excitement, told her ‘We did it!’26

Later that day, he met up with friends for a drink: ‘We opened a bottle of champagne, and I told them, “I think this is going to be pretty big.”’ It was the moment every scientist dreams of. But what Jeffrey Friedman could not then know was just how important his discovery was to prove.

‘It’s the truth to say it’s the closest thing to a religious experience I’ve ever had,’ Jeffrey Friedman told us. ‘A lot of scientists will explain things to be beautiful. In our case it’s a few blobs on an X-ray, but its clarity was incredible. At first, it seems odd to use an aesthetic description for a scientific reality, but it’s really the only way to explain that moment of discovery. I had a result that was aesthetically beautiful, it described how nature has learned to monitor too many calories that lead to fat accumulation; the answer is through making a hormone.’

Having pinpointed the gene responsible, his next task was to give it a name. Initially he intended to call it simply the ‘obesity gene’ but the Nobel Prize-winning French endocrinologist Roger Guillemin challenged his choice as inappropriate. After visiting Friedman at the laboratory, to learn about the discovery at first hand, Guillemin returned to Paris and wrote Friedman a letter: ‘I really liked what you had to say, but I have one quibble: you refer to these as obesity genes, but I think they are lean genes because the normal allele keeps you thin. But calling them lean genes sounds awkward. The nicest sounding root for ‘thin’ is from Greek, so I propose you call ob and db ‘lepto-genes’.”27

Friedman played around with this suggestion and finally decided to name the hormone he had identified as the satiety factor ‘leptin’. It was a discovery that many scientists regard as one of the most important advances of the twentieth century, and was the result of years of painstaking research and some extremely obese mice.

The discovery of leptin has allowed a far more humane and accurate portrayal of the disease of obesity. It is a condition in which the victims are physiologically – rather than exclusively psychologically – unable to control the amount they eat.

Leptin, 80% of which is secreted by subcutaneous white adipose tissue, has been dubbed the ‘hunger hormone’, and with good reason.28 Its function is to constantly monitor and regulate energy levels, a task it accomplishes in three main ways:

By counteracting the effects of a substance called neuropeptide Y, a potent appetite stimulus secreted by certain cells in the gut and by the hypothalamus, an organ buried deep within the brain.

By counteracting the effects of anandamide, another appetite stimulant.

By promoting the synthesis of a hormone with the tongue-twisting name of α-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone, which acts as an appetite suppressant.

Levels of leptin in the blood are directly related to the severity of obesity. When present in sufficient quantities and when brain and gut are receptive to its signals, leptin turns off the desire to eat the moment that energy needs have been met. In everyday parlance, our appetite ceases once we have eaten enough to sustain normal bodily function.

However, when leptin levels are too low and/or the brain and gut are, for some reason, unable to receive its signals, this ‘off’ button is never pressed, our hunger is never satisfied and our desire to carry on eating becomes uncontrolled and relentless. The situation is worsened by the fact that leptin is manufactured in inverse proportion to the amount of fat already in store. In other words, the fatter an individual, the less leptin they secrete and the more urgently and persistently their brain demands food.

‘When peripheral signals – such as leptin and insulin – are not released,’ says Nora Volkow, Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, ‘or your brain becomes tolerant to them, you don’t have a mechanism to counter the drive to eat . . . It’s like driving a car without brakes.’29

Leptin doesn’t just control energy intake and body weight. It also plays a role in such diverse processes as the immune response, bone development and cell growth. It even influences the time taken for wounds to heal.30

There is also evidence that it may affect the ease with which we breathe. Leptin encourages inflammation, and is found in higher levels among asthmatics, regardless of the extent of their obesity. Perhaps most surprisingly of all, leptin has a significant influence over fertility, sexual desire and the onset of puberty. To understand why a hormone whose primary function is the control of appetite should be involved in this most intimate of human behaviours we need to step back through time.

As we explained in Chapter 4, the lives of our earliest ancestors were marked by periods of famine interspersed with occasional feasts. When the crops were harvested, when fruit had ripened on the trees and when hunters returned with a fresh kill, the whole tribe could gorge themselves. But when food was scarce and there was insufficient energy available to meet all the body’s needs, the brain had to allocate what resources it had to the most essential activities: breathing, pumping blood, filtering urine and digesting what little food was available. With survival at stake, leptin was used to slow down or close down all activities that were not immediately essential, such as reproduction, sex drive, puberty, menstruation and even fighting off disease.

Thin, undernourished girls and boys, for example, reach puberty at a later age than do well-nourished girls and boys. Indeed, under extreme circumstances they may remain prepubescent for years. In women, menstruation will cease entirely under starvation conditions.

So the effects leptin has on the chemistry of the body are wide-ranging and significant. But it was its relationship with appetite which interested many people first and foremost. It seemed like it might be the magic bullet that would banish obesity without any need for dieting.

After all, if weight problems are largely caused by a leptin deficiency, then surely introducing it into an overweight person, perhaps by a pill or injection, would immediately diminish their appetite, allowing the excess pounds to drop away. Sadly, but perhaps not unexpectedly, given the complexity of human metabolism, it is not that simple.

Two years after Jeffrey Friedman’s discovery of leptin in mice, the first proof that the hormone also played an important role in humans was found; in 1997 researchers reported on their findings from studying two morbidly obese children.31

After being injected with leptin, these youngsters reduced their eating significantly and rapidly lost weight. Excited by the apparent potential of leptin in the treatment of obesity, Amgen – a biotech company – paid Rockefeller University $20 million to license the hormone. They gambled that, with increasing numbers of people becoming overweight or obese, such a treatment would prove highly lucrative, as well as offering a significant improvement in public health. A large clinical trial was started, in which leptin was injected into overweight adults. The results were disappointing; although a small group of obese patients did lose significant amounts of weight, the overall magnitude of the effect was minimal.32 Shortly afterwards, Amgen suspended research into leptin for treating human obesity. Their $20 million gamble had failed.

If Jeffrey Friedman was disappointed by the outcome of the Amgen trials he was not surprised: ‘Even before Leptin was tested in obese patients, we knew from animal studies that this hormone was not likely to be a panacea for every obese patient and that the response seen in ob/ob mice wasn’t going to be the typical case for obese humans. Leptin levels are elevated in obese humans, suggesting that obesity is often associated with leptin resistance and raising the possibility that increasing already high levels was going to be of arguable benefit.’33

Clearly, obesity is not simply an issue of leptin deficiency in the blood plasma, if injecting the hormone doesn’t actually change anything and if there are elevated levels of leptin in obese humans anyway. Rather, the issue must be leptin resistance. This occurs when receptors in the brain either no longer respond to signals from the hormone or do so with insufficient sensitivity.

But what causes this problem in the first place?

While the situation is still not entirely clear, the finger of blame seems to point firmly in the direction of diet. Animals in the wild, which do not usually stray far from their evolutionary ‘diets’, have properly functioning metabolisms in which the leptin pathway is preserved. Most modern humans, by contrast, now have a diet significantly different from what was eaten in even the fairly recent past. The result is that millions are metabolically challenged by seriously disrupted leptin pathways.

This being the case, the key to developing a successful antiobesity treatment involving leptin is likely to lie in finding ways of increasing the sensitivity of receptors in the brain to leptin, or by preventing resistance.

And the fast-growing field of personalised medicine, where treatments are developed to match a patient’s unique genetic make-up, may have something to contribute. It could allow doctors to identify which individuals will respond positively to injections of the hormone, like the small subgroup in the original Amgen trials. At the same time, research is being undertaken into other agents that might be combined with leptin to enhance its effectiveness with a wider group of people.34

There is a type of adipose tissue, known as brown fat, or brown adipose tissue (BAT), which has been observed to do something truly remarkable in laboratory mice: it protects the animals from becoming obese by burning more calories the more they eat. In human terms this is the equivalent of losing weight by overindulging on French fries! It’s definitely worth looking at BAT in greater depth.

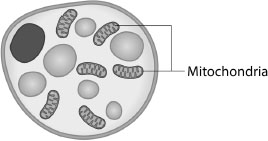

The distinctive colour of brown fat cells is due to the fact they contain a uniquely large number of organelles called mitochondria, which appear brown because they contain iron (see Figure 5.2). The function of mitochondria is to convert oxygen and food energy into cell energy or, in the case of brown fat, into heat. While brown fat occurs in rodents throughout their life, scientists once believed it was only present in humans during infancy and early childhood, when it helps maintain body temperature. The accepted medical wisdom was that by adulthood so little remained in the body as to have no significance.35 This is now known to be false.

The world-renowned Joslin Diabetes Center is located in Boston’s leafy Joslin Park, a brief stroll from the city’s ‘Emerald Necklace’, a series of parks and waterways covering more than a thousand acres. It was here, in 2009, that researchers announced a potentially game-changing discovery in the understanding and treatment of obesity. They had analysed almost two thousand body scans in the search for brown fat in adults. The results were published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. 36

They were striking. ‘Not only did we find active brown fat in adult humans, we found important differences in the amount of brown fat based on a variety of factors such as age, glucose levels and, most importantly, level of obesity,’ explains Dr Aaron Cypess of Harvard Medical School, a research associate at the centre.

‘What is of particular interest is that individuals who were overweight or obese were less likely to have substantial amounts of brown fat,’ says Ronald Kahn, Head of the Section on Obesity and Hormone Action at Harvard Medical School, another member of the research team. ‘Likewise, patients taking beta-blockers and patients who were older were also less likely to have active brown fat. For example, individuals both over age 64 and with high BMI scores were six times less likely to have substantial amounts of brown fat.’37

Brown fat was detected mainly in younger, leaner subjects in the regions of the neck and collarbone and was found much less frequently in overweight or obese individuals. Women had detectable regions of brown fat twice as often as men. Although the amount of brown fat found did not represent a high proportion of total body fat, being only 8% in women and 3% in men, the researchers also noted that the real amount was likely to be considerably higher; scans are capable of detecting brown fat cells of a certain size and activity, but almost certainly fail to identify smaller, less active deposits.

This matters, since even small amounts of brown fat could play a significant role in combating obesity. Somebody weighing 65 kg (143 lb), for example, might have only 65 to 80 grams (7 to 28 oz) of brown fat, compared to between 9 kg (19 lb) and 14 kg (30 lb) of white fat. However, if maximally stimulated, this could be capable of burning off at least 100–200 calories a day, which would be sufficient to lose almost half a kilogram (1 lb) of (white) fat each week.38

There is evidence that certain activities – such as spending time in the cold – can somehow activate brown fat, leading to increased caloric burn and a shift in other metabolic and hormonal functions. In a recent investigation into energy expenditure of men with and without brown fat, it was shown that exposure to cold activated brown fat and subsequently led to an increase in resting metabolism of 15% among those men with the extra reserves of brown fat, compared to those who did not have it.39

There is currently a burgeoning field of research dedicated exclusively to whether brown fat can be cultivated, and if so, how. While it continues to be an important therapeutic target, researchers are hesitant to proclaim the benefits: ‘Research papers say cold will “turn on” brown fat and cold will change the hormones that regulate body weight, but it doesn’t give you that next step that says sleeping in the cold will make you a fashion model,’ explained Steven Smith MD, one of the researchers at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute, where significant research is being conducted in this field.40

By finally recognising fat’s key role as an active organ, medical researchers have helped to demolish decades of dogma surrounding the causes of obesity. While sadly society still has quite a long way to go before it catches up with the facts, we now know with certainty that obesity is far from solely being linked to lifestyle choices. It is a serious and potentially life-threatening medical condition and should not be stigmatised as simply the just reward for gluttony and weakness of will.

fn1 RNA and DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) are the nucleic acids which, together with proteins and carbohydrates, make up the three major macromolecules that are essential for life.