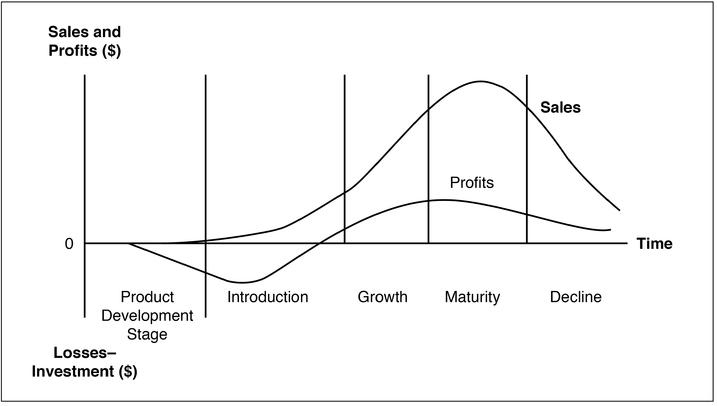

EXHIBIT 10-1 Sales and Profits Over the Product’s Life, from Inception to Demise

Adapting Pricing to Accommodate Common Challenges

If you always do what you’ve always done, you will only get what you’ve always got.

Anonymous

There are infrequent, yet common, strategic pricing challenges that can damage profitability unless recognized and managed appropriately. Appropriate management generally requires changing goals and patterns of organizational behavior to reflect a change in circumstances. Someone with cross-functional authority—perhaps someone in top management, perhaps an empowered manager of strategic pricing—must recognize the challenge and create an organizational or a cross-functional process to address it. The purpose of this chapter is to identify some of those challenges, enabling you to anticipate and thus to manage them proactively. They are as follows:

While the discussions that follow describe practices for dealing with each of these challenges, they also illustrate how understanding pricing issues that we have dealt with individually—customer value, competition, costing, and internal organization—can reveal still more opportunities for profit improvement when considered collectively.

The market for a product category passes through predictable phases, each with its own challenges for pricing (see Exhibit 10-1). Innovations, which offer customers new benefits that they could not achieve previously, require convincing customers that they should include the new category in the set of things they purchase. Growth in a product category requires aligning value with price across emerging market segments. Maturity requires making choices designed to maintain margins in the face of increasing competition and customers with enough accumulated experience to confidently evaluate the features and benefits of competing brands. Recognizing the need to adjust proactively to a changing market is key to sustaining relatively high margins and profits over the entire life cycle of a product category.

EXHIBIT 10-1 Sales and Profits Over the Product’s Life, from Inception to Demise

The number one pricing challenge when launching an innovation is to establish a price level that reflects and communicates the unique value created by the new “technology.”1 Not all new products are innovations from a customer perspective, since most new products simply offer more of the same benefits as their earlier substitutes or offer the same benefits at a lower cost. When a new technology enables customers to achieve entirely new benefits, it creates a new category of purchases. Since the category is new, most potential customers lack direct experience from which to infer value. A small subset of potential customers is likely to be induced to try an innovation because they can afford the risk and may know more about the science or technology of the category. Everyone else is unlikely to buy it, regardless of the price, because they have no experience enabling them to infer the heretofore unexperienced benefits and because they have no anchor by which to determine whether the price is “expensive” or “cheap” relative to value received.

The first automobiles, vacuum cleaners, electric stoves, automatic teller machines, and desktop computers, as well as the first offers of acupuncture sessions to treat illness, initially had to overcome considerable buyer apathy despite what ultimately proved to be substantial benefits. Why? Because an innovation requires buyers to change patterns they have learned from experience for how best to satisfy their needs. By definition, most customers know little about an innovative product or service and how it might address unmet needs in new ways that produce new benefits, let alone what the value of those benefits might be. Hence, successful launches of innovations hinge upon a company’s ability not only to create good value, but to develop customers who understand at least the potential of the product to create value for them.

An important aspect of that process is called information “diffusion.” Most of what individuals learn about innovative products comes from seeing and hearing about the experiences of others.2 The diffusion of that information from person to person has proven especially influential for large-expenditure items, such as consumer durables, where buyers take a significant risk the first time they buy an innovative product. For example, an early study on the diffusion of innovations found that the most important factor influencing a family’s first purchase of a window air conditioner was neither an economic factor such as income nor a need factor such as exposure of bedrooms to the sun. The most important factor was social interaction with another family that already had a window air conditioner.3 This finding has been replicated with dozens of innovations ranging from consumer electronics to business computers.

This diffusion process is extremely important in formulating pricing strategy for two reasons: First, empirical studies indicate that demand does not begin to accelerate until the first two to five percent of potential buyers adopt the product.4 The attainment of those initial sales is the hardest part of marketing an innovation. Obviously, the sooner the seller can close those first sales, the sooner she will generate positive cash flow and grow the market to its long-run level of demand. Second, “early adopters” are not generally a random sample of buyers. They are people particularly suited to evaluate the product before purchase. In most cases, they are also people to whom the later adopters, or “imitators,” look for guidance and advice.

Even early adopters, who may understand the technology and the potential benefits of an innovation, usually know little about how to value them in monetary terms. Value communications and effective promotional programs can readily influence which attributes drive those initial purchase decisions and how those attributes are valued. Identifying the early adopters and making every effort to ensure that their experience is positive is an essential part of marketing an innovation.5

The implication is that, in contrast to the launch of new products into mature markets, innovative products that create new markets are unlikely to win much additional volume by setting prices low, since neither “imitators” nor “early adopters” are price sensitive when making their first purchase. The “imitators” are not going to become early adopters simply because of a low price, since they lack a reference for determining what would constitute a fair or bargain price. “Early adopters,” on the other hand, are likely to place the highest value among all segments on the product’s potential benefits; that is what motivates them to try new, unproven products and services. The goal of pricing an innovation is to establish a reference price, via sales to early adopters, that communicates their belief that the innovative product or service offers differentiating benefits that are worth a premium price. That price, however, must not exceed a level that would cause early adopters to conclude after purchase that the product’s price was not justified by value received. Their endorsement and, if the product is a consumable, their repeat purchase, is what ultimately will drive growth as imitators, seeing the behavior and satisfaction of the early adopters, gain confidence that a purchase in the category is worth the risk.

So how can one drive initial adoption of an innovation if low pricing is unlikely to be very effective? Instead of setting prices low, one is far better off setting prices initially as if the only market for the product were those customers in the “early adopter” segment. The high margin from making a successful sale gives the firm a high incentive to mitigate hurdles than might otherwise prevent purchase. For example, one of those hurdles is often that channel intermediaries do not want to carry, let alone promote, a product that does not already have a market. In such situations, a large, even if temporary, wholesale price discount combined with resale price maintenance (see Chapter 12, pages 299–312) creates a high margin to motivate channel intermediaries. For consumer packaged goods, the discount may be offered in return for displaying the innovative product on an aisle “end cap” or other highly visible location. Sellers of innovative B2B technology products offer discounts for a limited time to influential channel partners who in return offer a high level of technical support that minimizes the risk of product adoption.

To motivate the early-adopter end customers, the goal is to overcome all the non-price hurdles to purchase. To mitigate fear that an innovative product or service might not actually generate the promised benefits, the seller might offer a high level of new purchase support, as Apple does with its Apple Stores® staffed by “geniuses” who enable potential buyers to recognize and personally experience the benefits of its product innovations both before and after purchase. For consumables, such as software products or memberships to a newly opened gym, the seller can offer limited free trials. For example, Tableau’s innovative data visualization software gives potential buyers 30 days of free use before requiring a payment to purchase continued access. It is important to note that in these cases, while the word “free” is used to motivate trial, the product is not in fact being discounted for a sustained period. In fact, the customer is being framed on the price that reflects value, and expects to pay that price once product performance is demonstrated and the benefits are experienced, or at least anticipated.

For innovative products that are infrequently purchased or experiential products, companies sometimes offer money-back guarantees that the product will be accepted for return for a refund if the customer is not fully satisfied. In the most extreme cases, companies selling high-margin innovations will even guarantee benefits whenever they are easily and objectively measurable. Pharmaceutical companies launching innovative drugs with relative high prices, such as chemotherapies, will sometimes offer the payer a complete refund for any patient who fails to respond to treatment.6 Another example comes from BulbHead, a seller of innovative lighting solutions. One of their top-selling items is a “Star Shower Motion” that consists of a laser light that is planted in front of a house and projects a decorative kaleidoscope of light onto it. One challenge facing potential buyers is that the product has been so popular that it has led to the less scrupulous holiday revelers stealing these lights from people’s lawns. To mitigate this potential barrier to purchase, BulbHead offers to send a replacement to any purchaser who has lost a Star Shower to theft.7 Of course, these types of offers can be expensive ways to make initial sales, but not nearly as expensive in the long run as offering a low price that is only minimally effective in driving sales but very effective in anchoring future price expectations at a needlessly low price point.

The end-customer retail price for the growth stage is normally less than the price set during the market development stage. In most cases, new competition in the growth stage gives buyers more alternatives from which to choose, while their growing familiarity with the product enables them to better evaluate those alternatives. Both factors will increase price sensitivity over what it was in the development stage. Moreover, even if a firm enjoys a patented monopoly, reducing price after the innovation stage can speed the product adoption process and enable the firm to profit from faster market growth.8 Such price reductions are usually possible without sacrificing profits because of cost economies from an increasing scale of output and accumulated experience.

Price competition in the growth stage is not generally cut-throat. The growth stage is characterized by a rapidly expanding sales base. New firms can generally enter existing markets and can expand without forcing competitors’ sales to contract. For example, sales of Apple’s iPhone® continued to grow, despite continual loss of some market share to new entrants during growth of the smartphone category. Because new entrants can grow without forcing established firms to contract, the growth stage usually will not precipitate aggressive price competition. Watch out, however, for the following situations that can presage unanticipated price competition:

In the cases above, price competition can become bitter as firms sacrifice short-term profit to sustain market share that they hope will become profitable as market size continues to increase.

Whether or not price competition becomes intense, the most profitable and generally viable pricing strategies in growth involve segmentation. In the introduction phase, all customers are new to the market but over time customers naturally segment themselves between those who are making their first purchase and those who are knowledgeable and experienced users of the new technology. Experienced buyers know enough to compare products based on online descriptions. Consequently, they can get better pricing than less experienced buyers, who may require the help of a retailer to select and configure the product.

In addition, different segments of the market emerge during the growth stage that will get different amounts of value from a product and/or will require different levels of costs to serve them. Innovative pharmaceuticals are a case in point. In most cases, end consumers pay only a fixed amount for a drug regardless of the cost to the healthcare system—which in some countries is a governmental department and in others is an insurer. The different types of payers range from those that exercise little control over what doctors prescribe, to those that create financial incentives for doctors and patients to select one drug in preference to another, to those that will pay for only a limited subset of drugs listed on an “approved formulary” list, leaving patients to pay the full cost of using a drug not on that list. The challenge when a market is highly segmented is to design a structure of discount criteria for contracting with these different types of payers that maximizes total profit contribution as described in Chapter 4.9

Many products fail to make the transition to market maturity because they failed to achieve strong competitive positions with differentiated products or a cost advantage earlier in the growth stage.10 In the growth stage, the source of profit is sales to an expanding market. In maturity, that profit source becomes nearly depleted. A strategy in a mature market that is predicated on continued expansion of one’s customer base will likely be dashed by competitors’ determination to defend their market shares. Having made capacity investments to produce a certain level of output, competitors will usually defend their market shares to avoid being overwhelmed by sunk costs.11

Pricing latitude is further reduced by the three additional factors that increase price competition as the market moves from growth to maturity:

All three of these factors have worked to reduce the prices of cellular phone services and of laptop computers by well more than half in competitive developed markets.

As discussed in Chapter 7 on Price Competition, effective pricing of commoditized products in maturity usually focuses not on valiant efforts to buy market share but on making the most of whatever competitive advantages the firm has to sustain margins. Even before industry growth is exhausted and maturity sets in, a firm does well to seek out opportunities to maintain its margins in maturity, despite increased competition among firms and increased sophistication among buyers. The five situations described below are good places to look for margin enhancement opportunities in mature markets despite the competitive pressures:

1. UNBUNDLING RELATED PRODUCTS AND SERVICES In the growth stage it is important to make it easy for potential buyers to try the product and to ensure that customers encounter no problems in experiencing the benefits. Consequently, it makes sense to sell everything needed to achieve the benefit as a bundled package. During decades of rapid growth in the customer base for video games, Nintendo launched uniquely popular video games—like “Super Mario”—that could only be played on its own video consoles. But as smartphones became more powerful, the growth in gaming shifted from dedicated players to mobile devices. To sustain its growth, Nintendo began in 2016 to unbundle its popular software IP from its video player—creating “Super Mario Run” for the iPhone.12 Although the price to download Super Mario to a mobile device is relatively low, the cost of sales and delivery is also low while the market is huge. Nintendo also for the first time licenses its creative IP for a theme park ride. Nintendo illustrates how, at the same time a market suffers from saturation, the existing base of loyal customers usually creates opportunities to grow by unbundling and leveraging the assets to grow in tangential markets.

As a market moves toward maturity, bundling normally becomes less a competitive defense and more a competitive invitation. As their numbers increase, competitors more closely imitate the differentiating aspects of products in the leading company’s bundle. This makes it easier for someone to develop just one superior part, allowing buyers to purchase other parts from the leading company’s other competitors. If buyers are forced to purchase from the leading company only as a bundle, the more knowledgeable ones will often abandon it altogether to purchase individual pieces from innovative competitors. Unless the leading company can maintain overall superiority in all products, unlikely in the maturity stage, it is generally better to focus on the products and services for which one can deliver a better value profitably, and let knowledgeable customers buy other parts from competitors. In the personal computer industry, the most successful companies built their products to accommodate whatever brand of printer or other peripheral products the customer might prefer.

2. IMPROVED ESTIMATION OF PRICE SENSITIVITY Given the instability of the growth stage of the life cycle, when new buyers and sellers are constantly entering the market, formal estimation of buyers’ price sensitivity is often a futile exercise. Estimates of price–volume trade-offs during growth frequently rely on qualitative judgments and experience from trial-and-error experimentation. In maturity, when the source of demand is repeat buyers and when competition becomes more stable, a firm can better gauge the incremental revenue from a price change and discover that a little fine-tuning of price can significantly improve profits. Most large consumer packaged goods companies have gained a competitive advantage relative to smaller competitors by investing in the capability to track and maintain actual sales data of their products at the retail level. This has enabled them to more finely optimize their competitive pricing strategies by package size, geography, and channel.

3. IMPROVED CONTROL AND UTILIZATION OF COSTS As the number of customers and product variations increases during the growth stage, a firm may justifiably allocate costs among them arbitrarily. New customers and new products initially require technical, sales, and managerial support that is reasonably allocated to overhead during growth, since it is as much a cost of future sales as of the initial ones. In the transition to maturity, a more accurate allocation of incremental costs to sales may reveal opportunities to significantly increase profit. For example, one may find that sales at certain times of the year, the week, or even the day require capacity that is underutilized during other times. Sales at these times should be priced higher to reflect the cost of capacity, creating an incentive for customers who can shift their demand to periods when capacity is underutilized. Examples of this tactic include discounted gym memberships that restrict access to off-peak hours, lower shipping costs if the recipient can accept delivery at off-peak hours, or “early bird discounts” at restaurants for diners willing to eat before the evening rush.

More important, a careful cost analysis will identify those products and customers that are simply not carrying their weight. If some products in the line require a disproportionate sales effort, that should be reflected in the incremental cost of their sales and in their prices. If demand cannot support higher prices for them, they are prime candidates for pruning from the line.13 The same holds true for customers. If some require technical support disproportionate to their contribution, one might well implement a pricing policy of charging separately for such services. While the growth stage provides fertile ground in which to make long-term investments in product variations and in developing new customer accounts, maturity is the time to cut one’s losses on those that have not begun to pay dividends and that cannot be expected to do so.14

4. EXPANSION OF THE PRODUCT LINE Although increased competition and buyer sophistication in the maturity phase erode one’s pricing latitude for the primary product, the firm may be able to leverage its position as a differentiated or as a low-cost producer to sell peripheral goods or services that it can price more profitably or by establishing charges for “discretionary” services. Although car rental margins are slim because they are easy to compare, the rental companies earn highly profitable margins from sales of the related addons: insurance, GPS systems, child safety car seats, and fuel purchase options. Credit card companies make money on the over-limit and late payment charges, the foreign currency fees, and the fees charged to retailers, even when they barely break even on the annual fee and the interest charges that drive a consumer’s choice of a card.

5. REEVALUATION OF DISTRIBUTION CHANNELS Finally, in the transition to maturity, most companies begin to reevaluate their wholesale prices with an eye to reducing dealer margins. There is no need in maturity to pay dealers to promote the product to new buyers. Repeat purchasers know what they want and are more likely to consider cost rather than the advice and promotion of the distributor or retailer as a guide to purchase. There is also no longer any need to restrict the kind of retailers with whom one deals. The exclusive distribution networks for Apple, HP, and even IBM have given way to low-service, low-margin distributors such as discount computer chains, off-price office supply houses, warehouse clubs, and direct sales websites. The discounters who earlier could destroy one’s market development effort can in maturity ensure one’s competitiveness among price-sensitive buyers. Airlines discovered, to their financial benefit, that the same principle applies to services. Once airlines realized that nearly all seats were filled by people who had experience traveling and so knew where they wanted to go, and probably even the names of airlines who would take them there, they could stop paying travel agents to book tickets. The few passengers who need help, say to book a vacation in an exotic location, still pay for the service. All others book directly with the airlines, online or by phone, saving the airlines millions in fees and even generating booking fees on their own.

Although there is no difference in principle between managing prices in a foreign or domestic currency, it is much more challenging in practice, when managing revenues in a foreign currency while incurring costs in a home currency. The reason is that floating currency exchange rates cause unplanned changes in prices and in costs relative to competitors. Even between economies very closely integrated, such as the United States and Canada, exchange rates can change by much more in a year than would be typical for changes in domestic prices. On July 1, 2014, $100 of Canadian dollar sales could be exchanged into $92.87 of U.S. dollar revenue for a U.S.-based firm. One year later, the same $100 of Canadian sales could be exchanged for only US$79.62 of revenue, a 14 percent reduction in U.S. dollar terms without any change in Canadian dollar prices.15 That difference was larger than the entire gross margin of many exports. Such currency fluctuations can easily drain the profitability of an entire market, or massively improve it, in a short period of time.

There are two considerations that a firm needs to take into account when deciding how to respond to a change in exchange rates: one specific to the firm’s strategy for export to a foreign market, the other specific to how a shift in an exchange rate impacts the relative competitive position of firms in that specific market. Since companies can have different strategies for sales in different markets, and can face different sets of competitors, there is no one simple formula for adjusting prices for changes in exchange rates. There is, however, a right approach given the circumstances the company faces for each exchange rate change in each market.

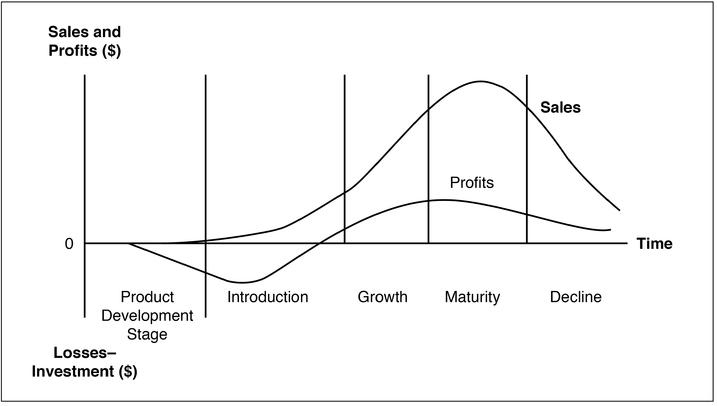

Exhibit 10-2 summarizes two alternative strategies for foreign market sales, which we have labeled “Opportunistic” and “Committed.” The firm’s choice of a foreign sales strategy should in part determine its approach to pricing for foreign sales. Is the firm’s objective simply to win profitable incremental sales in a foreign market, or to build a valuable brand franchise in that market? While these two objectives may be compatible in the same market for a short time, they will almost never be compatible at all times. In the former case, the firm may largely abandon a market when the depressed value of its currency makes sales less profitable than elsewhere, while in the latter case, the firm will attempt to maintain its competitive position in a market even at times when optimizing price for that market alone produces little or no immediate contribution to the firm’s overall profit. Companies selling commodities such as industrial chemicals and paper will usually adopt an opportunistic strategy, relying on local partners to actually sell their products, and set prices relative to their home currency price or to a price that they set in their home currency for exports. Companies with highly differentiated brands, such as luxury auto and industrial equipment suppliers, will usually follow a “committed” strategy, make investments in a market commensurate with that commitment, and set prices relative to the prices of competing products within that market.

For an opportunistic market, currency hedging may play a limited role if there is a significant gap between when sales are made and products are delivered. A company that sells elevators worldwide, often with contracts in the buyer’s currency and often for delivery a year in the future when a new building is near completion, hedges all contracted revenue by buying “puts” sufficient to cover all foreign currency sales for which it has made a price commitment. While that is adequate for implementing an Opportunistic strategy, it leaves a company with a Committed strategy still vulnerable since the latter is making an implicit commitment to keep prices competitive, even for customers to whom it has not yet made a sale.

EXHIBIT 10-2 Alternative Strategic Choices for Foreign Market Sales

A Committed company will need to hedge even more revenues. It may opt to hedge a large portion of its entire expected revenues in currency markets for a couple years forward, a costly but prudent strategy. Eventually, however, commitment will include making manufacturing investments in foreign markets to balance changes in the value of revenues with changes in the value of costs. The five largest auto manufacturers in the U.S. all have production capacity, and thus incur costs, in Canada as well. This creates a natural hedge for at least a large portion of their Canadian revenues since, if the Canadian dollar declines, more cheaply produced Canadian cars and car parts can be imported to the U.S. earning higher margins just as margins decline from sales that generate Canadian dollar revenues. It is important to note that a Committed seller will have to manage grey markets—or redistribution of its products—to ensure that buyers do not take advantage of arbitrage opportunities which can undermine investments that a seller has made in local production, retail presence, and aftermarket support.16

Unfortunately, commitment is not the only consideration for determining the right way to manage pricing in response to changes in exchange rates. One must also consider how any particular movement in an exchange rate affects your firm’s costs relative to your competitors in that market. Is the change in the exchange rate caused by a change in economic conditions affecting your firm’s home market currency or by conditions affecting the currency of the market where you will generate revenues? Why should it matter? Because something that affects the value of the foreign currency will affect it relative to all major currencies. All major competitors incurring manufacturing costs in a currency other than the currency of that particular foreign market will be similarly affected. For example, when the value of the Brazilian real declined by more than 20 percent in 2015 compared to the U.S. dollar, exporters of products to Brazil experienced a drastic decline in the revenue and profitability of their Brazilian sales measured in terms of their home currencies, whether those home currencies were euros, British pounds, Japanese yen, South Korean won, or American dollars.17 When every competitor is facing a loss because of a weakening of the buyers’ currency, they all have the same incentive to recover their losses by letting their foreign currency prices rise, and they can do so without fear of becoming less competitive.

The same magnitude of a shift in exchange rates has a very different strategic implication if caused by a strengthening of an exporter’s home currency. If the U.S. dollar appreciates due to a tightening of monetary policy relative to that in other major currencies, only exporters incurring costs in the U.S. dollar will experience a decline in dollar revenue and profits earned from sales in the foreign market. Since the profitability of exports costed in euros or yen will remain unchanged by the dollar’s appreciation, U.S. exporters cannot expect competitors from other countries to raise their prices to match the increases American firms would need to maintain their U.S. dollar margins. In the reverse situation, when a company’s home currency depreciates, it will gain a cost advantage in serving foreign markets relative to competitors incurring costs in other currencies. Thus, the company’s leaders might well expect that they could gain share from cutting foreign currency prices to reflect the decline in its relative cost, since foreign competitors will not have the same newly acquired cost advantage.

These two factors—the strategic goal of the exporter in a particular foreign market and the impact of the currency change on competition—create a two-by-two of market conditions implying four different responses for adapting to changes in currency exchange rates. Exhibit 10-3 illustrates these four options.

EXHIBIT 10-3 Stratagies for Managing Foreign Exchange Rate Adjustments

STRATEGY: OPPORTUNISTIC; COMPETITIVE IMPACT: SIMILAR The easiest way to pursue this strategy is to quote prices in terms of the home country currency, or in terms of another major currency in which the firm incurs its cost, letting the cost in the buyer’s local currency adjust automatically. This often means that a local distribution intermediary buys in the currency of the exporter and then quotes prices in local currency. In either case, prices in the local currency adjust quickly to changes in the exchange rate. If there is a delay between when sales are made and product is to be delivered, either the exporter or the distributor (usually the former) hedges the revenues associated with the sales commitment. With competitors adjusting their local currency prices to reflect an exchange rate change, the firm making a full local price adjustment to an exchange rate change can expect to maintain a similar market share profitably. If a committed competitor is willing to maintain local prices, that competitor will suffer in terms of cash flow to invest in the market. A firm without commitment is better off maintaining only whatever level of sales it can continue to make as profitably as it could in any other market. This is a strategy pursued by many non-branded oil refiners making gasoline and heating oil. They ship their product into whatever wholesale market offers the best price at time of shipment.

STRATEGY: COMMITTED; COMPETITIVE IMPACT: SIMILAR Geographic markets sufficiently attractive for one company to adopt a committed strategy are also ones where at least some of a firm’s competitors are likely to have done likewise. With everyone once again having similar incentives, one might easily assume that the impact of changes in a foreign currency’s strength would be the same in committed markets as in ones where a firm has adopted an opportunistic strategy. But that assumption would generally be wrong. When companies make a financial investment to develop and distribute a brand in a market, they will not quickly abandon the market when those customers’ currencies are weak or seek to exploit them when those currencies are strong. Their goal is to build brand awareness and reputation for the long term.

Recall from Chapter 7 the different ways that price competition impacts a large-share firm differently than a small-share competitor. If a local currency weakens, making the local market shrink and sales in that currency less profitable, smaller competitors are more likely to find that their profit contribution no longer covers the ongoing fixed costs of their commitment—local sales offices, promotional expenditures, and service. Thus small-share firms may be tempted to hold prices hoping to win enough additional revenue to survive. The challenge for the large firm is to adopt competitive strategies that makes it difficult for its smaller competitors to avoid either raising their prices or withdrawing. The adjustment to higher pricing may be delayed but eventually such strategies should enable local market prices to adjust to the strength of the currency in the same way that they would in a market where all competitors operate opportunistically.

STRATEGY: OPPORTUNISTIC; COMPETITIVE IMPACT: UNIQUE Being uniquely impacted by an exchange rate shift in a market where you have an opportunistic strategy involves primarily accepting that either sales or profit must change radically: the faster the better for the firm’s profitability. A strengthening of a firm’s home currency will make it less competitive in foreign markets; a weakening will make it more competitive. If major competitors are not facing the same exchange rate issue, they will be unlikely to make adjustments that are in parallel with your firm’s new costs, margins, and corresponding objectives. Consequently, the impact of changes in local currency prices is likely to be much larger, since it will likely involve losses or gains in market share. That may not be a problem if the firm’s home market or other foreign sales markets are large enough relative to the firm’s foreign sales to adjust to a change in available supply. The strengthening of a firm’s home currency may reflect strong growth that could absorb sales lost in foreign markets due to reduced competitiveness.

Unfortunately, a firm uniquely impacted by a strengthening home currency will face the problem of becoming less competitive in all of its foreign currency markets simultaneously. If foreign sales consume a substantial portion of the firm’s output, it logically may make sense to salvage as much export sales as possible to optimize any remaining contribution from those opportunistic markets. In that case, the firm should lower its export price to partially offset some of the impact of home currency appreciation. Determining how much it should discount its export price would require calculating breakeven sales changes associated with such a discount and determining whether the volumes that could be retained are sufficient to justify the discount.

STRATEGY: COMMITTED; COMPETITIVE IMPACT: UNIQUE The default assumption in “committed” markets is that the firm will set prices in local currency and not adjust them automatically to changes in exchange rates, adjusting only if competitors are adjusting their prices. But, in contrast to the case where the market currency has weakened, an appreciation in a firm’s home market currency is unlikely to trigger price increases by competitors who incur costs in other currencies that have not appreciated. A company can, for the next year or so, buy a Put option or sell the expected foreign revenue forward to avoid the risk of such an adverse movement in exchange rates. But such a temporary solution works only for a temporary problem. There is no simple solution to incurring costs in a currency that has strengthened relative to all others when one has investments in export markets that would be lost if the firm were to withdraw its brand, even temporarily.

When change in the value of a home currency uniquely affects your firm in a foreign market, adapting requires a change in strategy, not just in price. Fortunately, when general appreciation in a firm’s home currency makes foreign revenues worth less, it also makes foreign investments cost less. By investing in production capacity where the currency is weaker, a firm can rebuild its margins and partially insulate future profitability from swings in the relative value of currencies. Ideally, the firm should look for such opportunities in countries whose currencies tend to weaken when its own home country currency strengthens.

In the process of developing local production capacity, the firm might also develop versions of its products better adapted to the needs and ability to pay in more price-sensitive markets.

Managing pricing when market demand slumps is an essential skill for a pricing strategist in some industries. The economics for many products and services are largely determined by the ability to manage fixed costs, often by ensuring full plant utilization. For example, in capital-intensive industries such as beer brewing, higher education, or airlines, the means of production— whether a manufacturing plant, tenured professors, or an airplane—represent significant fixed costs. Consequently, declines in revenue often precipitate a much larger decline in profitability because these fixed costs, by definition, remain the same. The key to managing downturns successfully is to think clearly about how the downturn is affecting value, not just volume, for different customer segments and to use that knowledge to adjust pricing to drive revenue-generating changes in the mix of your customer base.

Sometimes markets slump for reasons that are not temporary. For example, new technologies make old ones obsolete. When there is a decline in demand for an entire category of products or services, such as when digital technology replaced photographic film and when air travel replaced long-distance trains, the shrinking of the market is permanent. The goal for the company with the strongest advantages in cost or product differentiation is to restructure the business quickly to serve a smaller market, focusing on a more targeted segment of customers who remain loyal to the old technology. For competitors without advantages in the declining market, the goal should to refocus assets elsewhere as quickly as possible, making pricing decisions in the declining market purely to generate short-term cash flow.

More interesting, and more common, are the cases where a market slump is cyclical and likely to be temporary. There are many industries that are highly cyclical, with demand that swings by much larger percentages than changes in growth of the economy as a whole. When an economic recession replaces 2 percent economic growth with a 2 percent decline, the demand for automobiles and airline seats declines by multiple times as much. Learning to manage pricing to minimize losses during downturns and to quickly recover profitability during upturns is key to a firm’s long-term survival in such industries.

The basic mistake by marketers who are ignorant about pricing is to cut prices across the board when demand falls. Price differences do affect inter-brand choice, especially during recessions when both business and consumer buyers become more price sensitive, a price cut may quickly gain some market share. But if, as can usually be expected, competitors match any cut to protect their market share, any sales gain is likely to be short-lived but industry revenues and profit contribution will remain depressed by even more than the initial decline in unit volume. The goal of any pricing actions should be the opposite: to sustain as much revenue and contribution as possible—both during the recession and the recovery. But how?

Answering that question requires understanding how the general economic decline affects the value perceived by your customers, and how that impact differs by customer segment. There are two reasons why demand may decline during economic recessions: because the number of customers is reduced or because the value of your differentiation is lower. One or both can reduce sales. Most revenue earned by major airlines comes from business travelers. During a recession, many of those business travelers have fewer opportunities to sell their products and so need to make fewer business trips—but the value of the trips they do make, including the differential value of flying on a carrier with direct and frequent flights, is not reduced. If perceived value is the same despite the reduced number of sales opportunities, it makes no sense to reduce prices for the changeable, flexible airline tickets that business travelers commonly demand. It may, however, make sense to reduce prices for ticket types used for discretionary travel, the demand for which is more sensitive to price than business travel. When businesses are planning internal meetings, they will compare the cost to holding the meeting in different locations. An airline (or a hotel) wishing to drive more discretionary business travel to a location where it has much capacity may offer a larger group travel discounts for tickets (or rooms) when sales are forecast to be far from capacity. To drive discretionary leisure travel, the airline might offer more of its capacity through tour operators who are required to offer the highly discounted flights only as part of leisure travel packages, thus precluding their use by business travelers.

To reiterate, determining when and how much to discount during an economic downturn should not depend on how much demand has fallen. What is important is how perceived value is affected and whether a lower price can truly reinvigorate demand. When value is reduced because of a slump in economic conditions, reducing price to reflect that change in value can stimulate category demand, but it is important to do so in a way that does not undermine the ability to charge a value-based price when demand and value recover. A client of ours had a chemical additive that increased the production capacity of a manufacturing plant, including both equipment and labor, by nearly 15 percent. Without their additive, the plant simply had to operate at a slower pace. The company easily launched the product with very profitable margins during a period of strong economic growth, when customers were operating their plants at capacity. When a recession occurred, however, demand for its product collapsed, despite the fact that its customers had maintained about 75 percent of their previous production.

An economic value estimation showed that the value of the additive was maximized when plants were operating near full capacity. But when manufacturing capacity was underutilized, the saving associated with our client’s innovative product was only the labor associated with being able to complete work in a shorter period of time. In that case, there was no incremental, avoidable cost of physical capital saved by increasing the efficiency of plant operations. Consequently, to maintain use of the product during the recession, the company would do well to reduce its price. The problem, of course, was how to ensure that the lower price did not become the price that buyers would continue to expect when demand made the product much more valuable.

The solution to this problem, as is often the case, was to create a value-based pricing metric. Instead of cutting the list price, the company offered to “share the pain” of the downturn. For customers agreeing to exclusive two-year contracts that rolled over each month unless canceled, the company agreed to give rebates retroactively for purchases in any month when industry data showed capacity utilization below 90 percent. Since the rebates were equal to nearly half of the selling price and since industry capacity utilization was nearer to 70 percent, the rebate structure made continued use of the product cost-effective. But the 24 month contract meant that when the recession ended and full production resumed, the price of the additive could reset to the original, higher price.

Another alternative to addressing declining demand in a downturn is to raise the value of the offer rather than cutting the price. Hyundai did this during 2009 when U.S. auto sales had fallen by 21.2 percent. Hyundai’s research revealed that the reason many consumers were holding off buying a car was not that their incomes had fallen—consumers were still mostly employed (the unemployment rate went from 5 percent in December 2007 to a peak of 10 percent in October 200918)—rather, it was a fear of becoming unemployed and the perceived risk of committing to a long-term car payment. To overcome that fear, Hyundai introduced the “Hyundai Assurance” program whereby a car financed or leased from Hyundai could be returned without any further obligation in the event that the purchaser became unemployed. The program was very effective and did not require additional discounting; Hyundai achieved a 14 percent year-to-year sales increase while the rest of the industry experienced a 30 percent decline.19

A frequently overlooked opportunity to use costs as a source of advantage occurs when the company can manage the prices of its upstream suppliers. These upstream suppliers might be independent companies or independent divisions of the same company that set the prices of products that pass between them. This situation, known as transfer pricing, represents one of the most common reasons why independent companies and divisions are sometimes less price competitive and profitable than their vertically integrated competitors. Most discussions regarding transfer pricing involve setting internal transfer prices between profit centers to minimize taxes across multiple tax regimes. The goal in that case is to find justifications (e.g., countries or states) for allocating costs to profit centers where taxes are relatively high, thus minimizing the tax obligation there, so that the firm can realize profits in a tax regime where tax rates are relatively low.20 That is not the purpose of our discussion here nor is it at cross-purposes. As described in Chapter 9 on Financial Analysis, there is no reason why one’s system for allocating costs for pricing need be the same as the system for allocating costs for financial reporting, since they have different purposes. The goal in allocating costs and revenues for pricing is to create incentives to maximize the collective profitability of the entire chain of profit centers that creates a product or service.

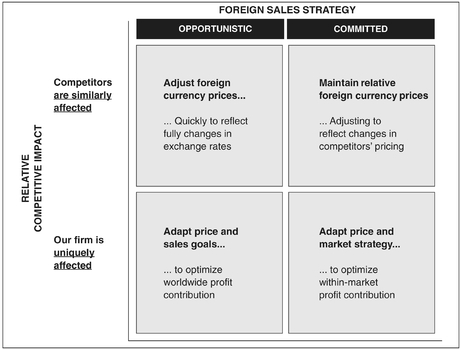

Exhibit 10-4 illustrates this often-overlooked opportunity. Independent Manufacturing Inc. sells its product for $2 per unit in a highly competitive market. To manufacture the product, it buys different parts from two suppliers, Alpha and Beta, at a total cost per unit of $1.20. The parts purchased from Alpha cost $0.30 and those from Beta cost $0.90. Independent Manufacturing conducts a pricing analysis to determine whether any changes in its pricing might be justified. It determines that its contribution margin (price minus variable cost) is $0.60, or 30 percent of its price.21

EXHIBIT 10-4 Inefficiencies in Transfer Pricing

It then calculates the effect of a 10 percent price change in either direction. For a 10 percent price cut to be profitable, Independent must gain at least 50 percent more sales (Chapter 9 presents the formulas for performing these calculations). For a 10 percent price increase to be profitable, Independent can afford to forgo no more than 25 percent of its sales.

Independent’s managers conclude that there is no way that they can possibly gain from a price cut, since their sales will surely not increase by more than 50 percent. On the other hand, they are intrigued by the possibility of a price increase. They feel sure that the inevitable decline would be far less than 25 percent if their major competitors followed the increase.

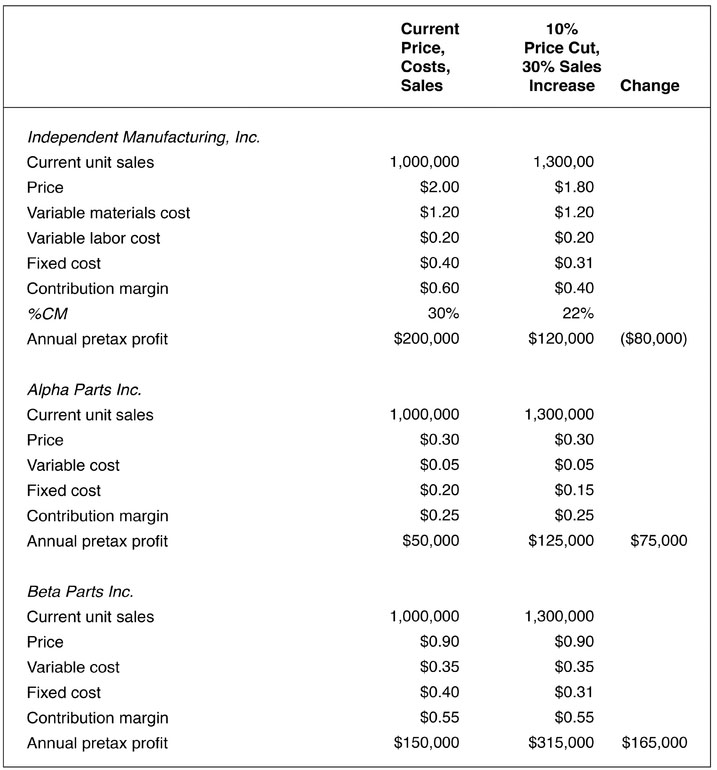

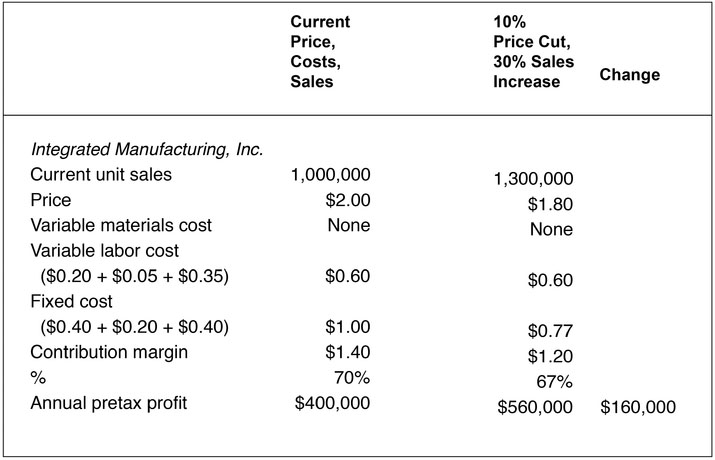

As Independent’s management considers how to communicate to the industry the desirability of a general price increase, one of its major competitors, Integrated Manufacturing Inc. announces its own 10 percent price cut. Independent’s management is stunned. How could Integrated possibly justify such an “irrational” move? Integrated’s product is technically identical to Independent’s, involving all the same parts and production processes, and Integrated is a company with a market share equal to Independent’s. The only difference between the two companies is that Integrated recently began manufacturing its own parts.

EXHIBIT 10-5 Efficiency from Cost Integration

That difference, however, is crucial to this story (see Exhibit 10-5). Assume that Integrated currently has all the same costs of producing parts as Independent’s suppliers, Alpha and Beta, and expects to earn a profit from those operations. It also has the same costs of assembling those parts ($0.20 incremental labor plus $0.40 fixed per unit). Moreover, Integrated enjoys no additional economies of logistical integration. Despite these similarities, the two companies have radically different cost structures, which respond quite differently to changes in volume and which cause the two companies to experience price changes differently. Integrated has no variable materials cost corresponding to Independent’s variable materials cost of $1.20 per unit. Instead, it incurs additional fixed costs of $0.60 per unit ($0.20 plus $0.40) and incremental variable costs of only $0.40 per unit ($0.05 plus $0.35). This difference in cost structure between Integrated (high fixed and low variable) and Independent (low fixed and high variable) gives Integrated a much higher contribution margin per unit than Independent’s margin. For Integrated, $1.40, or 70 percent of each additional sale, contributes to bottom-line profits. For Independent, only $0.60, or 30 percent of each additional sale, falls to the bottom line. Integrated’s breakeven calculations for a 10 percent price change are, therefore, quite different. For a 10 percent price cut to be profitable, Integrated has to gain only 16.7 percent more sales. But for a 10 percent price increase to pay off, Integrated could afford to forgo no more than 12.5 percent of its sales.

It is easy to see why Integrated is more attracted to price cuts and more averse to price increases than is Independent. For Integrated, sales must grow by only 16.7 percent to make a price cut profitable, compared with 50 percent for Independent. Similarly, Integrated could afford to lose no more than 12.5 percent of sales (compared with as much as 25 percent for Independent) and still profit from a price increase. How can it be that two identical sets of costs result in such extremely different calculations? The answer is that Independent, like most manufacturers, pays its suppliers on a price-per-unit basis. That price must include enough revenue to cover the suppliers’ fixed costs and a reasonable profit if Independent expects those suppliers to remain viable in the long run. Consequently, fixed costs and profit of both Alpha and Beta become variable costs of sales for Independent. Such incrementalizing of non-incremental costs makes Independent much less cost competitive than Integrated, which earns more than twice as much additional profit on each unit it sells.

Independent’s cost disadvantage is a disadvantage to its suppliers as well. Independent calculates that it requires a 50 percent sales increase to make a 10 percent price cut profitable. Independent, therefore, correctly rejects a 10 percent price cut that would increase sales by 30 percent. With current sales of 1 million units, such a price cut would cause Independent’s profit to decline by $80,000. Note, however, that the additional sales volume would add $240,000 ($75,000 plus $165,000) to the profits of Independent’s suppliers, provided that they produce the increased output with no more fixed costs. They would earn much more than Independent would lose by cutting price. It is clear why Integrated sees a 10 percent price cut as profitable when Independent does not. As its own supplier, Integrated captures the additional profits that accrue within the entire value chain (Alpha, $75,000; Beta, $165,000) as a result of increases in volume.22

Once Independent recognizes the problem, what alternatives does it have, short of taking the radical step of merging with its suppliers? One alternative is for Independent to pay its suppliers’ fixed costs in a lump-sum payment, perhaps even retaining ownership of the assets while negotiating low supply prices that cover only incremental costs and a reasonable return. The lump-sum payment is then a fixed cost for Independent, and its contribution margin on added sales rises by the reduction in its incremental supply cost. Boeing and Airbus sometimes do this with parts suppliers, agreeing to bear the fixed cost of a part’s design and paying the supplier for the fixed costs of tooling and setup. They then expect a price per unit that covers only the supplier’s

variable costs and a small profit. As a result, the airplane manufacturers bear the risk and retain the rewards from variations in volume, giving them a larger incremental margin on each additional sale and so a greater incentive to make marketing decisions, including pricing decisions, which build volume.

An alternative approach is to negotiate a high price for initial purchases that cover the fixed costs, with a lower price for all additional quantities that cover only incremental costs and profit. Auto companies use this system; allowing a supplier to be a sole source with high margins up to a certain volume, presumably enough to recover design and development costs. Beyond that volume, they make the design public and usually expect all suppliers to match the lowest price on offer. In Independent Manufacturing’s case, it might negotiate an agreement with Alpha and Beta that guarantees enough purchases at $0.30 and $0.90, respectively, to cover their fixed costs, after which the price would fall to $0.10 and $0.50, respectively.

Both of these systems for paying suppliers avoid incrementalizing fixed costs, but they do not avoid the problem of incrementalizing the suppliers’ profits. They work well only when the suppliers’ profits account for a small portion of the total price suppliers receive. Lump-sum payments could be paid to suppliers to cover negotiated profit as well as fixed costs. This is risky, however, since profit per unit remains the suppliers’ incentive to maintain on-time delivery of acceptable quality merchandise. Consequently, when a supplier has low fixed costs but can still demand a high profit because of little competition, a third alternative is often used. The purchaser may agree to pay the supplier a small fee to cover incremental expenses and an additional negotiated percentage of whatever profit contribution is earned from final sales.

It is noteworthy that most companies do not use these methods to compensate suppliers or to establish prices for sales between independent divisions. Instead, they negotiate arm’s-length contracts at fixed prices or let prevailing market prices determine transfer prices.23 One reason is that it is unusual to find a significant portion of costs that remain truly fixed for large changes in sales. In most cases, the bulk of costs that accountants label fixed are actually semifixed; additional costs would have to be incurred for suppliers to substantially increase their sales, making those costs incremental. One notable case where costs are substantially fixed is in the semiconductor industry. The overwhelming cost of semiconductors is the fixed cost of product development, not the variable or semifixed costs of production. Consequently, integrated manufacturers of products using semiconductors, such as Samsung, have often had a significant cost advantage. Similarly, Tesla has recognized that if the cost of batteries remains such a large part of the cost of electric cars, a firm that can internalize the fixed costs to make its own batteries will have a large advantage over one that buys batteries at a variable cost.

Most decisions that people, including managers, make are made from habit. When the decision turns out to be the right one in most cases, it gets applied without thinking. When changes occur or when a new market involves forces that do not fit the pattern of one’s experience, it is important to recognize that traditional strategies need to be rethought. Pricing an innovation is different from pricing an established product, and pricing in maturity is different from pricing in a growing market. Setting prices in foreign currencies when costs are incurred in domestic currencies requires consideration of issues that are not usually part of the pricing decision process. Pricing when a market faces a substantial, but temporary, downturn in demand requires a quick response both to project margins from the current, albeit shrunken market, while driving incremental revenues from new sources. Establishing transfer prices, for sales or purchases, can substantially affect a firm’s competitive viability in those situations where the suppliers’ prices cover largely fixed costs. While these are challenges that many companies encounter over years in business, there are no doubt other less common ones that a thoughtful pricer should look out for. There are no tried and true rules for pricing that apply to all situations, even in the same industry. Whenever facing a situation that feels different, it is wise to reevaluate how the forces that drive your usual success in pricing are different and what changes may be necessary in your strategy to accommodate them.

1. We use the term “technology” in the general sense of a concept by which benefits are created. Most innovations are, in fact, enabled by “technology” in the more narrow sense of the word. But occasionally an innovative “technology” is something intangible, like an innovative business model that no one thought of previously. For example, in the middle of the last century, now famous companies like McDonald’s and Holiday Inn were innovators in developing and applying the innovative technology of “franchising.” The technology of franchising enabled investors with little or no prior knowledge of the industry to enter and enjoy instant success by leveraging a very standardized model—something that was not achievable previously.

2. See Everett M. Rogers and F. Floyd Shoemaker, Communication of Innovations, 2nd edn. (New York: The Free Press, 1971); Frank M. Bass, “A New Product Growth Model for Consumer Durables,” Management Science 15 (January 1969), pp. 215–227.

3. William H. Whyte, “The Web of Word of Mouth,” Fortune 50 (November 1954), pp. 140–143, 204–212.

4. Rogers and Shoemaker, op. cit., pp. 180–182.

5. See Everett M. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations (New York: The Free Press, 1962), Chapters 7 and 8; Rogers and Shoemaker, op. cit ., Chapter 6; Gregory S. Carpenter and Kent Nakamoto, “Consumer Preference Formation and Pioneering Advantage,” Journal of Marketing Research 26 (August 1989), pp. 285–298.

6. Thomas Nagle, “Money-Back Guarantees and Other Ways You Never Thought to Sell Your Drugs,” PharmaExecutive (April 2008).

7. “Maker of Blockbuster Star Shower Holiday Lights Will Help Theft Victims by Replacing Lost Items Free,” PRNewswire, November 21, 2016. Accessed at www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/makerof-blockbuster-star-shower-holidaylights-will-help-theft-victims-by-replacing-lost-items-free-300366889.html.

8. See Abel P. Jeuland, “Parsimonious Models of Diffusion of Innovation, Part B: Incorporating the Variable of Price,” University of Chicago working paper (July 1981).

9. Nagle, op. cit.

10. William K. Hall, “Survival Strategies in a Hostile Environment,” Harvard Business Review (September 1980).

11. This problem can even result in a period of intensely competitive, unprofitably low pricing in the maturity phase, if, as sometimes happens, the industry fails to anticipate the leveling off of sales growth and thus enters maturity having built excess capacity.

12. “It’s a-Me! How Super Mario Became a Global Cultural Icon,” The Economist, December 24, 2016.

13. See Philip Kotler, “Phasing Out Weak Products,” Harvard Business Review 43 (March–April 1965), pp. 107–118.

14. Theodore Levitt, “Marketing When Things Change,” Harvard Business Review 55 (November–December 1977), pp. 107–113; Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, (Free Press, 1998), pp. 159, 241–249.

15. OANDA currency converter website. Accessed at www.oanda.com/currency/converter.

16. For a more detailed discussion of grey markets and how to manage them, please refer to the discussion in Chapter 4 on Price Structure.

17. Vinod Sreeharsha, “Sharp Drop in Currency Adds to Growing List of Woes in Brazil,” The New York Times, September 24, 2015. Also see: Joe Leahy, “Exports from China to Brazil Collapse as Recession Deepens,” Financial Times, February 26, 2016; and Raquel Landim and Eduardo Cucolo, “Drop in Imports Helps to Increase Brazil’s Trade Surplus, the Largest since 2011,” Folha de S. Paulo, January 5, 2016.

18. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “The Recession of 2007–2009,” BLS Spotlight on Statistics, February 2012. Accessed January 6, 2017 at www.bls.gov/spotlight/2012/recession/pdf/recession_bls_spotlight.pdf.

19. Randall Beard, “Learning from the Hidden Success Factors of the Hyundai Assurance Program,” Marketing with Impact blog, October 9, 2009. Accessed January 6, 2017 at https://randallbeard.wordpress.com/2009/10/19/hidden-success-hyundai-assurance.

20. For additional discussion of the goals of, and legal constraints on, transfer pricing in financial reporting, see John McKinley, “Transfer Pricing and Its Effect on Financial Reporting: Multinational Companies Face High-Risk Tax Accounting,” Journal of Accountancy, October 1, 2013. Accessed January 6, 2017 at www.journalofaccountancy.com/issues/2013/oct/20137721.html.

21. $CM − $2.00 − $0.20 − $0.60 %CM = $0.60/$2.00 × 100 = 30%

22. An integrated company does not automatically gain this advantage. If separate divisions of a company operate as independent profit centers setting transfer prices equal to market prices, they will also price too high to maximize their joint profits. To overcome the problem while remaining independent, they need to adopt one of the solutions suggested for independent companies.

23. For a related perspective, see Thomas W. Malone, “Bringing the Market Inside,” Harvard Business Review 82(4) (April 2004), pp. 106–115.