EXHIBIT 11-1 Archetypal Pricing Organizations

Assembling Talent, Processes, and Data to Build Competitive Advantage

The facts which kept me longest scientifically orthodox are those of adaptation.

Charles Darwin1

Even after creating a pricing strategy that addresses all of the elements contained in the value cascade, pricing leaders often find that much of their organization remains remarkably resistant to changing behaviors. As one senior executive we know remarked: “Given the attention we pour into pricing our products, why do the outcomes still seem like a random walk?”

This executive is not alone. In a benchmarking study2 of more than 200 companies, Deloitte assessed the impact of pricing strategy and execution on profitability and revenue growth. Our research shows that more than 60 percent of sales and marketing managers were frustrated by their organization’s ability to improve pricing performance over time. And more than 75 percent were unsure what they should be doing to drive more effective execution of the organization’s pricing strategy.

In that study, each firm’s pricing strategy was assessed based on key inputs for making a pricing decision such as customer value, costs, competitive conditions or market share goals. Executional capabilities were assessed based on the quality of a firm’s data and tools, the skill level of decision-makers, and the clarity of the firm’s processes. Firm performance was measured on operating profits relative to peer firms within their sector in an effort to eliminate the impact of sector differences. A broad spectrum of firms drawn from a range of sectors including manufacturing, consumer products, health care, financial services, high tech, retailing and services were included in the analysis.

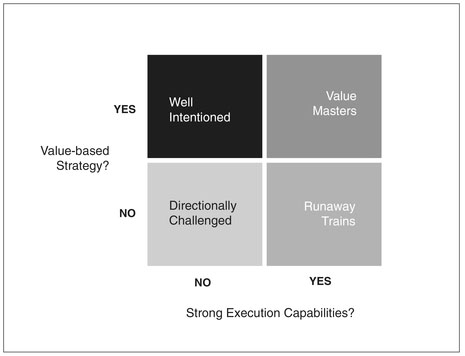

To facilitate this analysis, firms were classified based on the quality of their pricing strategy (value-based or not) and the ability of a firm to execute a pricing strategy (strong or weak). Each firm was assigned to one of four archetypes, as shown in the two-by-two matrix in Exhibit 11-1. There were the “Value Masters” who employed value-based pricing and excelled at execution; “Well Intentioned” firms that were value-based but poor executors, “Directionally Challenged” firms that did not have a value-based pricing strategy and lagged in their executional capabilities; and the “Runaway Trains” that were excellent at execution but did not employ a value-based pricing strategy.

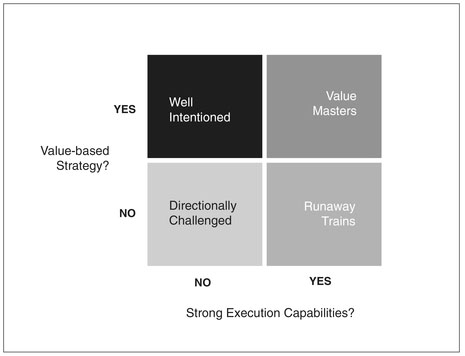

When operating profitability was compared among these four archetypes, the results were clear: Firms that employ a value-based pricing strategy paired with strong execution capabilities, outperform their peers by a significant margin. As shown in Exhibit 11-2, firms that excel on both dimensions were, on average, 24 percent more profitable than their industry average. The worst performers were those that did not link their pricing strategy to value yet executed effectively, hence the moniker “Runaway Trains.”

EXHIBIT 11-1 Archetypal Pricing Organizations

One common trait among each of the “Value Masters” is that they excelled in setting strategic goals and objectives across all elements of the value cascade: They understood how to create value for customers, how to convey the value proposition, build offers for each segment served, design policies that encourage profitable transactions, and had the ability to monitor transaction performance. But good strategy alone is not enough. The highest performing firms in our study also invested heavily in building an organizational structure to support execution of a value-based strategy. These firms exhibited an internal alignment around value: R&D efforts focused on innovations that created value, not just new features; marketing communications messages translated product features and services into benefits to which customers could assign value; and clear policies linked discounts to trade-offs of value and price. Overall, these organizations exhibited a singular focus on their customers and framed decisions based on how they would influence customers’ perceptions of value.

EXHIBIT 11-2 Operating Profit Relative to Industry Peers

So why do most organizations still struggle to implement a strategic, value-based approach to pricing that has proven to be more profitable? While there are many answers to this question, several organizational shortfalls account for the majority of the challenge.

The first organizational challenge involves pricing skills and capabilities. According to one study, only 9 percent of business schools offer a stand-alone course on the topic of pricing,3 explaining in part why only 6 percent of the Fortune 500 have a dedicated pricing function.4 In addition, many industries went through a long period of stable, or in some cases decreasing, input costs that lasted for much of the 1990s and early 2000s. The apparel industry, for example, experienced declines in labor and cotton costs, two of its major input costs, over a 15-year period dating back to 1995. Consequently, pricing was a less pressing issue and many turned their attention to improving other sources of profitable growth. However, as cost shocks simultaneously hit cotton and labor from 2008 to 2012, many apparel companies found that they did not have the know-how to raise prices in an effort to preserve their margins.5

A second challenge is the need to coordinate pricing decisions across functional areas, requiring the input and support of many decision-makers. Even when a company has a pricing function formally tasked with managing pricing, compensation plans that reward sales revenue alone make it difficult for even well-intentioned sales representatives to fight for an additional percentage point of price when that might increase the probability of losing a deal and the associated compensation. Along the same lines, marketers are often incentivized to maintain or grow market share, which can often be accomplished most quickly through price promotions that may erode brand equity and long-term margins. Finance executives are often evaluated on achieving a target margin percentage which leads them to argue against low-margin/high-volume opportunities that could increase return on investment even at the expense of return on sales. Operations executives often focus on maintaining capacity utilization even when that drives down market prices and reduces profits for all. Our research shows, however, that the Value Masters tended to have incentive structures that rewarded profitable pricing decisions.

A third challenge is access to the necessary information and tools to make profitable pricing decisions. The Value Masters in our survey generally had some form of commercial-grade pricing software that expedited the task of analyzing transactional data. Most had alerts that were triggered if discounts exceeded a threshold. Many had historical price-trend data to determine market prices. These systems allowed companies to assess profitability at the customer and product level, identify costly customer behaviors that were worth discouraging, and quickly detect and intervene with customers who were receiving “exceptional” pricing.

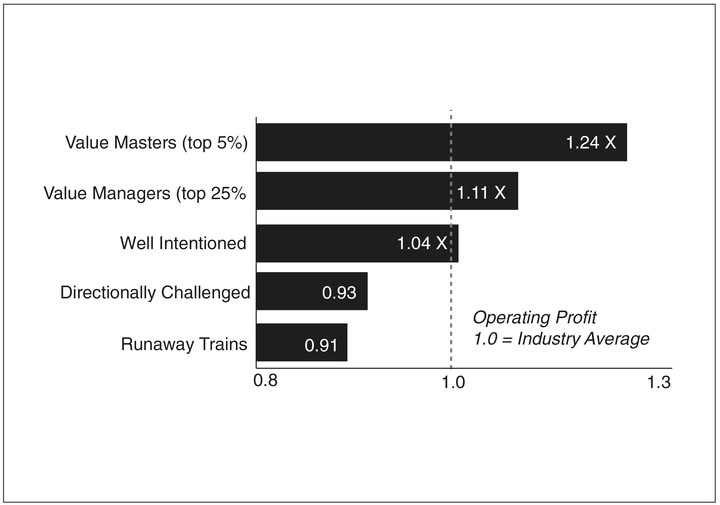

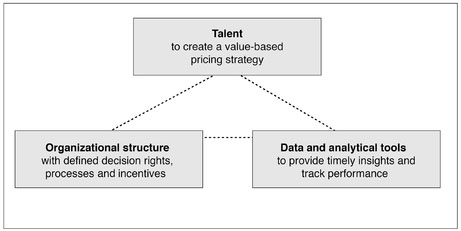

Taken together, there are three underlying investments needed to build a strategic pricing capability. As noted by Dutta et al.,6 these investments can be classified as: (i) The human talent needed to develop a value-based pricing strategy; (ii) an organizational structure with well-identified roles and responsibilities for managing and executing the pricing strategy; and (iii) the data and analytical tools needed to supply the organization with relevant, timely information (Exhibit 11-3).

To succeed, companies need to balance investment in all three elements; investing too much in one at the expense of the others can lead to catastrophe. The airline industry, for example, invested heavily in yield management tools in the 1980s and used this new capability to engage in an extensive price war that in 1991 managed to wipe out the cumulative profits earned by airlines up to that point in their history.7 It can be argued that many airlines overinvested in data and analytics (which enabled the price wars), and underinvested in the other two components of a pricing capability: The ability to innovate profitable new sources of value and establishing an organizational understanding that targeting market share alone is a recipe for disaster.

EXHIBIT 11-3 The Foundation for a Strategic Pricing Capability

Assessing the Maturity of the Pricing Organization

So how can you determine the relative capability of your pricing organization? A quick test would be to ask your top five executives to articulate your firm’s pricing strategy. If you get five different answers, you likely have a problem! And while we raise this point a little tongue in cheek, the responses can demonstrate a lack of maturity in a firm’s pricing capability. What to evaluate:

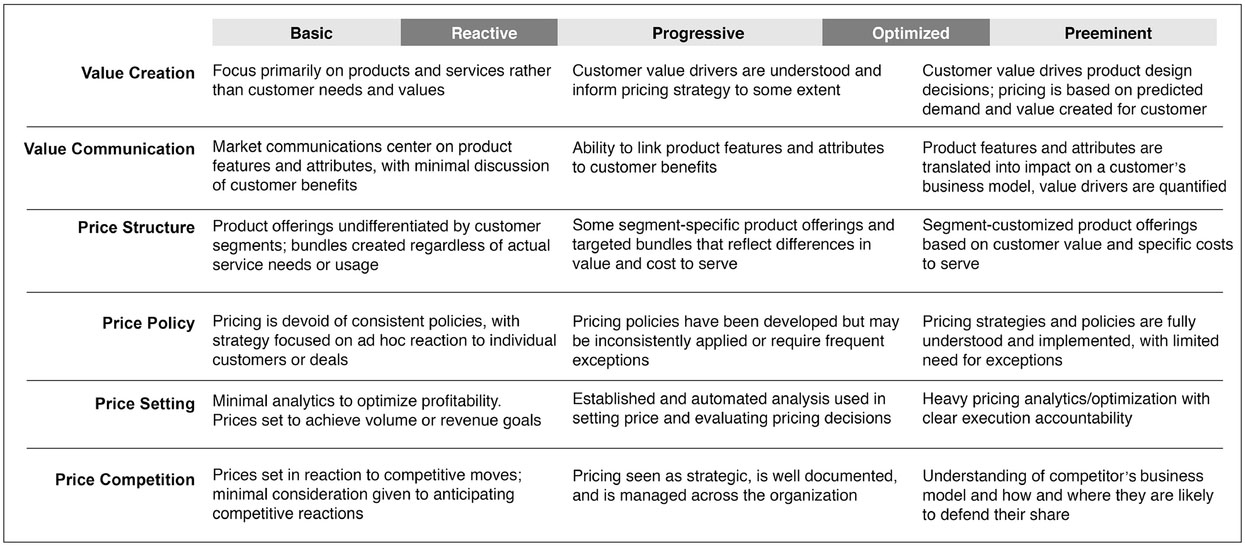

To help inventory a firm’s capabilities more precisely, we use the framework provided by the Value Cascade and assess each element on three dimensions: (i) How well articulated is the strategy that supports each element of the cascade; (ii) what is the degree of organizational alignment behind each and is there someone responsible for managing that element of the cascade; and (iii) are there systems and tools in place to help inform and guide each element of the cascade?

Exhibit 11-4 provides a summary of the capabilities needed to support each element of the value cascade as well as organizational characteristics at each level of maturity. In general, as companies become better at quantifying their value and delivering that value consistently, their financial performance tends to improve.8

EXHIBIT 11-4 Assessing Each Element of the Value Cascade

The best strategy in the world is only as good as an organization’s ability to make it come to life. A frequent barrier to implementing improved pricing strategies—whether it is a new way of configuring the offer design or simply applying more discipline to discounting—is that the change does not align with “the way we do things around here.” Or worse, the idea of creating a pricing function is seen as a threat to the political power of a member of the management team who currently has the ability to adjust prices or approve deals to achieve some short-term, functional objective.

Consider the example of an IT distributor that had long prided itself on developing an array of high-quality services that included best-in-class customer support that includes on-demand technical consulting delivered by inhouse engineers and next-day delivery logistics. These services were included with the purchase of any product and available to any customer. However, a closer look at the customer base revealed that not everyone needed this high level of support—and in fact many price-sensitive customers were defecting to competitors selling a cheaper offering bereft of many expensive services. After careful consideration, this distributor received a recommendation to create a tiered services model whereby customers could either get lower product prices in exchange for lower service levels, or they could retain access to high service levels by paying a small premium on their purchases. The immediate response among senior executives was that “everyone needs the high level of service, it’s just that some customers don’t know it yet.” Only after losing 20 percent of their revenue base to low-cost competitors was this company willing to test a low-cost offering. Once they did, the results were staggering—the low-cost offer enabled the distributor to regain their price-sensitive customers and to do so profitably by offering them a standardized way to buy.

Ultimately, the characteristic that most distinguishes high-performing organizations is the ability to continually refine and re-imagine the process for how value is exchanged between seller and buyer. High-performing companies exhibit the following characteristics:

The ability to challenge norms of how value is exchanged has never been more important. As disruptive forces such as autonomous driving, urbanization, or a low-growth economic environment exert themselves on established businesses, we are seeing massive changes in how value is created, delivered, perceived and captured. In the past ten years, entire industries have had their pricing models upended, in some cases multiple times. Music labels used to control the revenue model by selling albums in physical formats such as records, CDs, and cassettes. In 2001, Apple undid this revenue model when it launched iTunes® to allow for the sale of single songs and by 2011, revenues from digital outpaced physical content sales. In 2016 the dominant revenue model switched yet again to streaming, led by the likes of Spotify, Apple itself9 and others. There are many other industries, including hospitality, transportation, telecommunications, legal services and software that have seen similar upheaval in their revenue models.

One remarkable characteristic of this disruption is that revenue models have typically been reinvented by industry newcomers who often harness disruptive technologies and are themselves unencumbered by industry norms or by the risk of failure. Kodak endured a legendary decline brought on by digital technology, but its demise was not inevitable. In fact, Kodak invented the original digital camera back in 1975. Management’s reaction at the time when Kodak’s revenue was driven by the high-margin sales of paper and chemicals, was “that’s cute but don’t tell anyone.”10 Kodak viewed themselves as being in the paper and chemicals business and had no idea how to monetize the bits and bytes that underpin a digital photo. Yet consumers who valued a cost-effective and convenient way to create a visual record of their life adventures eagerly adopted new offerings from a host of companies that offered digital cameras, storage devices, and file-sharing services that reshaped our relationship with photography. Along similar lines, companies like Uber and Airbnb, unencumbered by decades of industry norms such as selling high volumes of cars to fill plant capacity or putting “butts in beds” to utilize large real-estate investments, have re-imagined how consumer transportation or hospitality needs could be addressed. Of course, newcomers are able to take on more risk; after all, what is the worst that can happen to a start-up company?

That said, successful incumbent companies will continually take calculated risks to reinvent their business and stay ahead of the upstarts. Any incumbent should ask whether their organizational culture is holding back innovative ideas. If an organization is to survive, and even thrive, it is critical that managers continue to challenge themselves on how their own industry may become disrupted by upstarts with new ways of creating and capturing value. Still, some companies are better than others at challenging the status quo.

Amazon is a company that has throughout its history continuously tried new ways of doing things. From a seemingly simple beginning of creating an online bookstore, to replacing books with electronic readers, to creating the world’s largest online department store, to delivering food from local restaurants, the company has shown a willingness to try new things and accept the risk of failure. In 2016, its approach extended to launching a small chain of physical bookstores in recognition of a consumer desire to browse and discover new content.11 Amazon has continually explored new ways to reinvent its own business model.

By contrast, other retailers may be more reticent to try entirely new business models and instead focus on optimizing the deployment of existing assets such as store locations, assortment designs, or floor layouts. There is nothing wrong with this type of learning and experimentation—indeed, there are great gains to be had from optimization efforts in most businesses.12 However managers should be aware that optimization is inherently centered on current business norms and runs the risk of missing opportunities to disrupt the existing business model or the risk of being disrupted.

Exploring New Ways to Manage a Price Increase: Lessons from Netflix

Done poorly, a pricing move can have disastrous consequences. The example of Netflix, the innovative movie rental company, demonstrates that there are effective and less effective ways to raise prices. In July 2011, when Netflix raised prices of its services by up to 60 percent and split its DVD and streaming businesses into two entities, the consumer outrage was immediate. Facing significantly higher prices and the need to use two channels for accessing content, movie watchers everywhere blogged, tweeted, emailed, unfriended, and even wrote old fashioned letters to any organization that would listen.13 The displeasure reached a crescendo when Netflix’s CEO issued a public apology for the price increase. However, the damage was done. More than 10,000 customers posted their displeasure on the company’s blog; 1 million subscribers had cancelled their service; and the company lost more than half of its market value within two months.

By contrast, a more recent price increase by Netflix has been well-received. On May 12, 2014, Netflix implemented a 12.5 percent price increase, gained 1.7 million new subscribers during the quarter in which the increase took effect, and the impact is estimated to total $500 million in incremental revenue by 2017.14

What was different this time around? Netflix segmented their customer base between existing and new subscribers and only applied the increase to new customers. Since existing customers were not subject to the higher price, and new subscribers were opting in, consumers generally did not perceive a “loss” typically associated with a traditional price change. In addition, Netflix had announced its intent to raise prices, and offered guidance that the increase would “be in the $1 to $2 range.” When the increase came in at the bottom of the range, affected consumers were likely relieved that it was not more. Given the range of potential market reactions, it’s no wonder managers often approach price increases with trepidation.

The ability to challenge existing business norms and try new things has enabled Netflix not only to manage the transition from a DVD-by-mail business to a streaming model. It has also enabled Netflix to share in the new value streams created for its customers.

One of the most common reasons why good pricing strategies fail when implemented is that processes and incentives within the organization are inconsistent with the strategy’s objectives. An executive at a global commercial bank recently described the challenge:

At a global level, our leadership team is tasked with managing the profitability of the entire business. We’ve made significant investments in customer service and other value-added capabilities to better serve customers and ensure that our products are at the forefront of the industry. Our stated goals at the corporate level include an ambitious gross margin target that reflects the superior quality of our services.

At the same time, this executive explained that sales were managed at the country level and each country manager was responsible for setting prices to reflect local-market and competitive conditions. Country managers, however, were primarily assessed on achieving volume and share targets. Consequently, country managers viewed pricing as a lever for achieving sales goals, with profits as a secondary consideration. Not surprisingly, prices negotiated by country managers were often below the expectations of global leadership. To make matters even more challenging, country managers often customized discount programs, often in ways that were not supported by the bank’s billing systems. As one might imagine, the end result was complete chaos with hundreds of discounts that could not be tracked by the bank’s operations team, millions of dollars in services that were not invoiced, and an inability to perform even basic profitability analysis of customer accounts.

To break this cycle, the company created a weekly meeting to review all new contracts to ensure some degree of consistency and internal alignment. To further mitigate the price erosion, all parties agreed to adhere to criteria that customers had to meet to qualify for price discounts. While a seemingly simple mechanism, bringing key decision-makers into a conversation led to a common understanding of global objectives yet still allowed the ultimate price to reflect local market conditions.

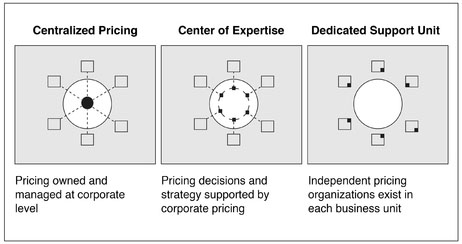

The above example highlights a critical choice facing organizations in designing a pricing function: The degree of centralization. Generally speaking, a more centralized pricing function is effective when a company operates within a single market or has business units operating in similar market contexts. Centralized pricing in these contexts enables the company to invest in developing a core of expertise that can be leveraged across markets. However, the benefits of a centralized pricing function diminish when business units are operating in markets that have significant variations in terms of competitive pressures, product specifications, or customer buying patterns. In those instances, it is often more productive to push decision-making out to the business units while maintaining coordination and support mechanisms more centrally.

These two dimensions of a pricing function, the role played and the degree of centralization, provide the underpinnings for three archetypal organizational structures for the pricing function (Exhibit 11-5). The actual choice of an organizational design may involve some combination of these archetypes because each potential choice involves trade-offs that can enhance or detract from the ability to execute the pricing strategy. Nevertheless, we have found these archetypal structures prevalent across markets.

The first archetype is “Centralized Pricing,” in which pricing decisions are made and managed at the corporate level. This archetype is commonly used in industries such as energy or airlines where the product is highly commoditized and financial success is driven by achieving an advantage in the cost of operation and capacity (yield) management. It is important to note that even in centralized pricing organizations, actual price levels may vary in (controlled) ways across markets; the key is that the pattern of variation is closely managed.

EXHIBIT 11-5 Pricing Structure Archetypes

Where pricing is centralized, the role of the business unit is to collect data and enforce process compliance in support of the pricing decisions made at the corporate office. Large airlines are examples of companies that typically have a highly centralized pricing function. For example, as of this writing, one of the major airlines offered 18 different prices for flights from New York to Miami.15 Multiply this complexity by the more than 325 routes that this airline serves and it is easy to see the complexity of responding to competitive price moves. Adding to the challenge, any change in the price of one route immediately creates shifts in demand that have a cascading effect on other routes and markets served. In addition, given the hyper-competitive nature of the airline industry where competing airlines will quickly respond to price moves, a single pricing mistake has the potential to ignite a price war. Consequently, for an organization like a major airline, it is imperative to manage pricing in a centralized setting to ensure that any price change is considered in a global context.

The second functional archetype is the “Center of Expertise,” which is characterized by the business units maintaining control of the pricing decisions and pricing processes. In this structure, the pricing function provides a vehicle for sharing best practices and supports the development of more effective pricing strategies. The central group will often have specialized skills such as the ability to perform advanced analytics or to build systems capabilities that would not be cost effective to develop for each business unit individually. Often the group assumes the role of functional coordinator. As noted previously, this team will often serve as an internal consulting function focused specifically on pricing that improves pricing outcomes through knowledge transfer. Markets with unique local conditions, such as retail or telecommunications, will often have functional coordinators that assist local area managers in decision-making.

The final functional archetype is the “Dedicated Support Unit” in which each business unit has a dedicated pricing group that is only loosely aligned with corporate pricing (if that function even exists). The role is typically either a functional coordinator or commercial partner. This type of structure is appropriate for diversified businesses with little overlap in market type or customer base.

Formal structure alone is not the only consideration when organizing for pricing; it is also necessary to specify decision rights of managers both within and outside of the pricing function. Allocating decision rights ensures that each participant understands their role and the constraints on what they can and cannot do with respect to pricing. Failure to formally allocate pricing decision rights leads to more inconsistent pricing and greater conflict as managers attempt to influence pricing decisions.

A business services company unwittingly ran into this problem when it created a key account team to augment their traditional sales force to better serve its largest accounts. Unfortunately, there was no coordination between the key account team and the traditional sales force in managing price quoting activity. As a result, large accounts started to receive competing and inconsistent price quotes, which only led these large customers to actively solicit additional quotes in hopes of getting a better deal. Although large accounts grew considerably under the key account program, average selling prices declined rapidly, along with profitability.

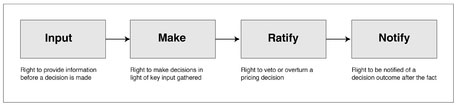

Decision rights, as the name implies, define the scope and role of each person’s participation in the decision-making process as illustrated in Exhibit 11-6. There are four types of decision rights: Input, make, ratify and notify.

Input. Given the large amount of data required to make pricing decisions, many managers are given “input” rights to pricing decisions. As the name implies, input rights enable an individual to be an accepted source of some specified information necessary for the decision. Typically, input rights are granted to individuals from finance, forecasting, and research to provide critical data, such as the additional cost imposed by rush orders, but they are not responsible for commercial outcomes.

Make. In contrast to “input” rights, which can be allocated to many individuals, the “make” decision rights should belong to only one person or committee. This ensures clear accountability for pricing decisions and creates an incentive to follow up on pricing choices to ensure that they are implemented correctly.

EXHIBIT 11-6 Types of Decision Rights

Ratify . Ratification rights provide a mechanism for senior managers to overturn pricing decisions when they conflict with broader organizational priorities. It is essential to separate “make” and “ratify” rights to ensure that senior managers can regulate the decision-making process without the burden of monitoring and analysis that leads to a recommendation. Granting ratification rights to a senior manager balances the need to incorporate her strategic perspective into the decision-making process against protecting her time and ensuring that she does not get bogged down in day-to-day pricing operations.

Notify. Finally, “notification” rights should be allocated to individuals that will use or be affected by the pricing decisions in other decision-making processes. For example, it is quite common to grant notification rights for pricing decisions to members of the product development team so that they can build more robust business cases for new products and services.

Once the organizational structure has been established and decision rights have been defined, the final step for organizing the pricing function involves the creation of clearly defined pricing processes. In many organizations, pricing processes are defined quite narrowly, including only price-setting and discount approval activities. But strategic pricing spans all of the activities that contribute to more profitable commercial outcomes. For example, the negotiation process might not be considered part of the pricing function, but it is one of the most critical determinants of transaction profitability. So too, are decisions about whether and what to charge for services such as rush orders, special packaging and extended terms. Moreover, a process to define and change discount policies proactively is necessary to avoid creating by default a reactive process for approval of ad hoc discounts. It is essential to think broadly when defining pricing processes.

Ensuring that all elements of pricing strategy get regular proactive review makes the investment in formally defining pricing processes a good one. Thankfully, the steps to creating good processes are fairly straightforward and facilitating the creation of them is an important role of the pricing function.

Step 1: Define major pricing activities. This step involves defining the major process activities such as opportunity assessment, price setting, negotiation, and contracting. The objective is to put boundaries around the commercial system so that all relevant activities affecting profitability are included.

Step 2: Map current processes. This step creates a visual depiction of the processes by which pricing decisions are currently made, as illustrated in Exhibit 11-7. Even if there are no formally defined processes currently in place, this is a critical step for finding the source of undesirable pricing outcomes.

Step 3: Identify profit leaks. This step uses a variety of pricing analytics (discussed in the next section of this chapter) to identify where profit leaks—which we define as losses in profitability caused by, for example, unwarranted or unmanaged discounts, incurrence of unnecessary costs, or unmet terms and conditions—are occurring in the current pricing process.

Step 4: Redesign process . This final step creates a series of redesigned pricing processes for each of the major pricing activities identified in Step 1. In order to implement the new processes, it is frequently necessary to revise decision rights to account for new individuals included in the revised process and to account for current decision-makers from whom decision rights have been taken away.

EXHIBIT 11-7 Map of Decision-Making Process for a Manufacturing Company

Measuring performance motivates desirable behaviors, especially when the measures lead to public rewards or financial recognition. Yet, many companies struggle to obtain the desired results from their compensation programs as evidenced by the more than 58 percent of managers in our research who indicated that their incentive plans likely encourage choices that reduce company profits.16 So why is it so difficult to design effective incentive programs? The first and often most challenging barrier involves ensuring that performance measures motivate the right behaviors. Employees engage in complex activities every day, and companies often get caught in the trap of trying to design metrics and incentives to guide all of them. But the inclusion of too many metrics can become confusing and lead to a loss of focus as well-intentioned employees struggle to figure out what to prioritize.

Instead of trying to create an overly complicated set of performance metrics, successful companies often settle on a limited set of metrics that are tied closely to profitability and then hold people accountable for their performance against those measures. Consider the dilemma facing sales representatives, independent dealers, and manufacturers’ representatives who are compensated based on a percentage of sales. Say that a company’s margin is 10 percent on high-volume deals. A sales rep who invests twice as much time with the account, selling value and/or getting the customer to reduce costly behaviors like asking for rush orders or production break-ins, might at best be able to increase the profit earned on the deal by an additional 10 percent of sales— doubling the profitability. Even if all that increase is in price however, the sales rep’s revenue-based commission increases by only 10 percent because the commission is based on a percentage of sales.

In contrast, consider the tactics of a colleague who spends the same amount of time selling two deals of the same size. However, in order to close two deals instead of just one, she economizes her time by not selling on value and as a result only achieves a 10 percent margin. In this case, both sales reps increase the company’s profit contribution by the same amount, but the one who prioritizes volume over profitability earns twice as much commission for doing so. Even worse, if the volume-focused colleague were to offer a 5 percent price cut to close her deals (and thus cutting the profit contribution in half), she would still earn a commission substantially higher, while the sales rep who spent time selling value rather than volume hears about his failure to meet sales goals.

Until you fix these perverse incentives associated with revenue-based measurement and compensation—driving revenue at the expense of profit—it will be difficult to get sales reps to do the right thing. The key to aligning sales incentives with those of the company is to link compensation with profitability. A common objection to doing so is that companies do not want to reveal their costs and because they may have reason in some cases to drive volume even when the immediate payback from sales of that product would be greater from higher margins. For example, selling one product or service cheaply may give the company an advantage in selling other, more profitable products to the same customer. Fortunately, there is a way to incorporate profit contribution into a sales compensation plan to whatever degree is desired without actually publishing costs data.

The text box “Creating a Sales Incentive to Drive Profit” explains how to implement a compensation system that incorporates margins, and other variables, when determining the credit that a sales rep earns for making a sale. More than just theory, tying compensation to profitability in this way aligns the interests of the sales rep with the financial interests of the company. And it encourages salespeople to pay more attention to value drivers linked to innovative product features, quality improvements, and delivery speed. Once the company aligns sales incentives, salespeople ask for “price exceptions” much less frequently, but they begin clamoring for the other things they need in order to succeed at selling value. At one company, for example, sales reps traded in their company sedans for vehicles in which they could transport product to customers who had an urgent need. Why? Because customers with an urgent need and little time to solicit deals from multiple suppliers could be convinced to buy without demanding greater discounts.

Another challenge to the design of an effective incentive plan is the lack of alignment among performance measures across functions. Salespeople paid for generating profitability will be stymied if undercut in their efforts to raise price by others who are measured on achieving market share or volume. For example, a high-tech manufacturer we worked with had given the finance group ratification rights for price-setting to ensure that prices were set with sufficient financial prudence. One financial policy that was strictly enforced was that all products must maintain a minimum 64 percent gross margin or be eliminated from the product portfolio. The financial staff, which was evaluated on the ability to maintain gross margins, routinely vetoed requests for any prices that fell below the 64 percent threshold regardless of the market conditions or the volume. Not surprisingly, the sales organization, whose commission was based on sales volume, had a very low regard for the business acumen of the financial staff. Moreover, the salespeople would spend hours each week devising creative ways to work around the financial staff to get approval for high-volume but lower-margin deals.

The first step to align metrics and incentives across the organization is to document current incentives for all of those that have been granted decision rights in the pricing process. That documentation enables you to highlight potential conflicts that can detract from effective decision-making. Ideally, the next step will be to change the incentive plan so that decision-makers will share common objectives as they make pricing choices. But changing incentives can be time-consuming and involve considerable upheaval in the organization and thus may not always be a desirable option. In these instances, it is necessary to create policies that constrain how pricing decisions will be made and ensure that the policy compliance is tracked with various price-management analytics. For example, it may be too difficult to tie sales incentives to all costs that could affect the profitability of a customer. Generally, sales incentives reflect only variable product costs. In that case, it may be necessary simply to have a policy that limits what is acceptable. For example, rather than including cost-of-capital-to-finance receivables in product margins, it may be more practical to have a policy that limits the ability to offer extended payment terms.

Creating a Sales Incentive to Drive Profit

The key to inducing the sales force to sell value is to measure their performance and compensate them not just for sales volume, but also for profit contribution. Although some companies have achieved this by adding Rube Goldberg-like complexity to their compensation scheme, there is a fairly simple, intuitive way to accomplish the same objective. Give salespeople sales goals as before, but tell them that the sales goals are set at “target” prices. If they sell at prices below or above the “target,” the sales credit they earn will be adjusted by the profitability of the sale.

The key to determining the sales credit that someone would earn for making a sale is calculating the profitability factor for each class of product. To induce salespeople to maximize their contribution to the firm, actual sales revenue should be adjusted by that profitability factor (called the sales “kicker”) to determine the sales credit. Here is the formula:

Sales Credit = [Target Price – k (Target Price – Actual Price)] × Units Sold

In the above equation, k is the profitability factor (or “kicker”).

In order to calculate sales credits varying proportionally to the product’s profitability, the profitability factor should equal 1 divided by the product’s percentage contribution margin at the target price. For example, when the contribution margin is 20 percent, the profitability factor equals 5 × (1.0/0.20). When a salesperson grants a 15 percent price discount, the discount is multiplied by the profitability factor of 5, reducing the sales credit by 75 percent rather than by 15 percent had there been no profitability adjustment. Consequently, when $1,000 worth of product is sold for $850, it produces only $250 of sales credit. But when $500 worth of product is sold for $550 (a 10 percent price premium), the salesperson earns $750 of sales credit ($500 + 5 × $50).

Because salespeople are more likely to take a short-term view of profitability and can always move to another company, the most motivating profitability factor for the firm is usually higher than the minimum kicker value based solely on the contribution margin. Obviously, the importance of this adjustment is directly related to the variable contribution margin. The larger the margin and, presumably, the greater the product’s importance to the firm, the greater the profitability factor’s ability to align what is good for the salesperson with what is also good for the company.

This is not merely theory. Among companies that have moved toward more negotiated pricing, many have adopted this scheme in markets as diverse as office equipment, market research services, and door-to-door sales. Although a small percentage of salespeople cannot make the transition to value selling and profit-based compensation, most embrace it with enthusiasm. Managers should be prepared for the consequences, however, because salespeople’s complaints about the company’s competitiveness do not subside. Instead, salespeople who previously fretted about the company’s high prices begin complaining about slow deliveries, quality defects, lack of innovative product features, the need for better sales support to demonstrate value, and so on. In short, sales force attention moves from reflexive gripes about price to legitimate concerns about value drivers the company does or does not provide to customers. This is a good thing.

If you cannot measure it, you cannot improve it.

Lord Kelvin17

Establishing clearly defined processes and decision rights helps ensure that pricing strategy choices will be made in a consistent and repeatable manner. But to ensure that those decisions will also maximize profits, they must be based on accurate, useful information. All too often, crucial pricing choices are based on anecdotal data that may provide a limited, but unconfirmed, understanding of market conditions.

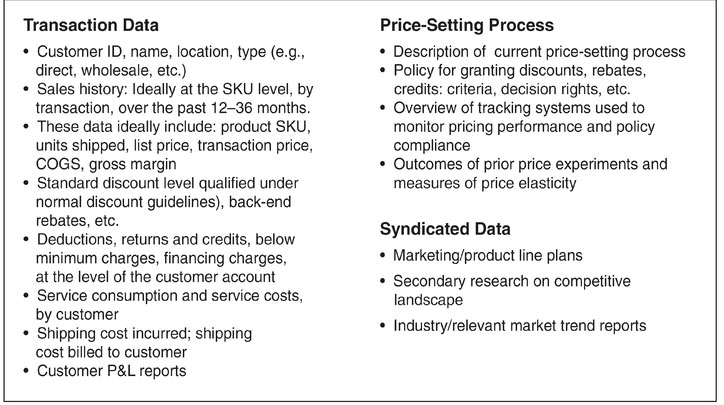

Systems capability for a pricing function requires three key components: (i) Objective data that provides insight into the available pricing opportunity; (ii) a set of protocols for performing analytics that provide relevant, actionable insights; and (iii) tools to perform the calculations and present results in pragmatic ways that generate unambiguous management choices. We discuss each of these components in more detail below.

Some of the data required to inform pricing decisions is quite easy to find. Most organizations, for example, have records of historical sales that contain transacted prices, surcharges for additional services such as shipping, discounts applied, and other descriptors of the transaction. Thinking back to the value cascade, historical transaction data are particularly relevant for evaluating market responses to price changes, identifying sources of “revenue leakage,” such as when discounts are being given to customers who do not qualify for them, or evaluating which customers are most profitable.

Other data sources will be more difficult to obtain. Competitive pricing moves, for example, may be difficult to detect quickly because a competitor may not announce a price cut when they are attempting to gain market share. In this instance, information regarding a competitive price change will typically filter in from customers or field sales representatives. Many retailers have instituted “price match guarantees” in an effort to not only remain price competitive, but also to institute a mechanism to “crowd source” competitive price information in real time.

The array of analytics that can inform pricing decisions is practically endless, covering data about product costs, cost to serve, purchase trends, customer value, transaction prices, and more. It is beyond the scope of this text to detail all of these analytics and demonstrate how they can best be used to improve strategy choices. Therefore, we focus on two categories that have historically proven most useful to pricing strategists: Customer analytics and process analytics. In addition, we will review analytics that gauge the efficacy of the pricing decision processes we described in the discussion of the pricing function earlier in this chapter.

EXHIBIT 11-8 Illustrative Data Sources for Pricing Analytics

Customer analytics focus on understanding customer motivations and behaviors that are relevant to pricing choices. We have already examined one of these analyses with the discussion of value assessment in Chapter 2. In the following discussion, we will focus on the analytics of win–loss data and customer profitability, both key inputs for measuring the success of pricing strategies.

Tracking the frequency with which a company’s offers win or lose to the competition is probably the most valuable piece of information that a company can collect. Amazingly, many do not do so. Instead, they measure performance relative to plan, which is usually based upon extrapolation from past experience when conditions may have been quite different. If overall market demand begins to increase more rapidly than expected, a company can meet its plan but still be losing share to competitors. Failing to recognize quickly that a competitor has improved its product or service, reducing the differentiation value of your offer, will reduce the time available to prevent further loss through either investment in new sources of differentiation or thoughtful, selective price adjustments. On the other hand, a company may fail to achieve expected sales because of an overall decline in market demand even while maintaining its market share. Reacting in that situation with an ill-advised price cut could lead an industry into a price war that compounds the adverse impact of the economic downturn on profitability.

For companies that sell direct, how frequently do customers that request a proposal or that check pricing on a website actually make a subsequent purchase? Comparing current period win–loss ratios with previous periods may require comparing orders from the same geographical area or for purchases with similar end-use application. Significant losses may indicate a need for a price reduction; significant gains may indicate the need for a price increase unless you believe that competitors cannot or will not cut their prices to defend their traditional market shares.

For companies that sell through channels of distribution, market share data is the best indicator of changes in win–loss ratios. However, published market shares usually reflect performance in the all too distant past. To get data that is current enough to act upon, a company can often purchase very current data from samples of stores or from distributors.

Of course, the ultimate goal is not to maximize the share of “wins,” but to maximize profit contribution earned. Looking at win–loss data alone tells something about performance only if prices are unchanged. If the win rate is up but prices have declined, was the gain in volume sufficient to compensate for the decline in margins? If the win rate is down following a price increase, was the contribution lost from the additional lost bids less than what was gained from the higher prices? Similar analyses can be conducted across regions or customer segments to evaluate differences in price sensitivity that can inform future pricing decisions. A similar analysis of changes in the win–loss ratio can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of advertising or a value-communication campaign.

Historically, marketers have long tracked product profitability as a key metric for managing the product portfolio and allocating marketing resources. In recent years, however, customer profitability has emerged as another metric that can be instrumental to marketers seeking to improve profitability. Customer profitability measures are created by assessing prices paid by specific customers and combining them with cost-to-serve measures that allocate costs to customers based upon customer demands and requirements that actually drive them. Creating customer profitability measures often requires some effort because most accounting systems either do not allocate costs at the customer level or do so arbitrarily. But the benefits are generally worth the effort because customer profitability analysis provides actionable guidance to improve the profitability of a customer portfolio.

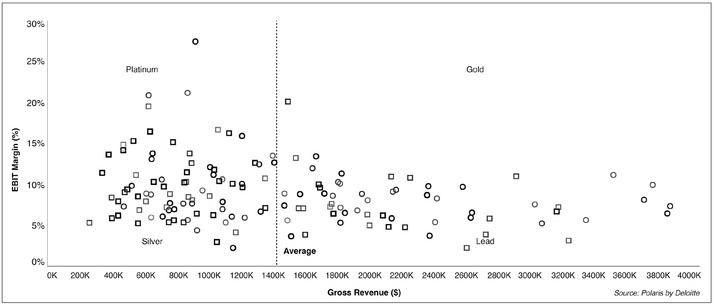

The data drawn from a financial services firm (shown in Exhibit 11-9) shows shows one approach for analyzing customer profitability that charts each customer based on average selling price and cost to serve. There are opportunities for profit improvement in each quadrant, and the fact that customers are charted individually allows for highly targeted actions. The “Platinum” customers located in the upper-left quadrant need to be protected. They are sometimes taken for granted because they pay high prices and do not incur a lot of costs. However, it is essential to understand why these customers are paying a premium and to ensure they are getting good value for that price. Otherwise, they may be lost when competitors discover them and offer a better deal. In contrast, the “Lead” customers in the lower-right quadrant merit a different course of action. The most egregious of these “outlaws” in the lower-right quadrant must be made profitable by either reducing cost-to-serve or raising prices. Raising prices on the unprofitable customers in this quadrant can result in two outcomes; the customer pays the higher price because of the value delivered, or they defect and move to a competitor. This is a low-risk move for the company because it will increase average profitability, and, often, total profitability, regardless of the outcome.

EXHIBIT 11-9 Customer Profitability Map

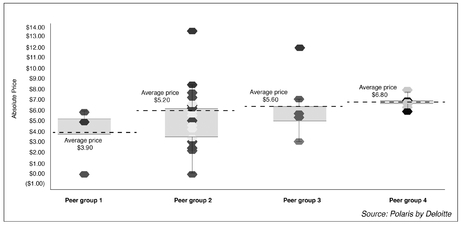

Assessing customer profitability provides high-level guidance for pricing or cost-reduction moves that can improve company profits. Additional profit improvement opportunities can be uncovered by a more detailed individual customer profitability assessment, as illustrated in Exhibit 11-10. This analysis, which details the specific sources of revenue and cost, allows for the comparison of individual customers to segment averages to identify outliers that are consuming too many resources or not generating sufficient revenues. This individual customer profitability analysis, from the same financial services firm, was instrumental in helping management take corrective actions such as increased use of automation and the bulking of claims that helped reduce direct labor costs and processing costs and drove a 37 percent improvement in profitability.

EXHIBIT 11-10 Customer Profitability by Peer Group

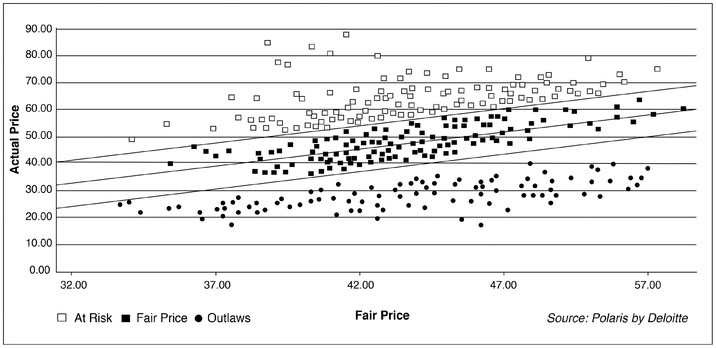

The intent behind process management analytics is to measure unsatisfactory pricing outcomes (such as profit leaks) and trace them back to the pricing process where they can be “sealed.” Whereas customer analytics focus on strategy development period. Analytics reviewing process efficacy can identify profit leaks in the pricing process such as those caused by unwarranted or unmanaged discounts. Process analytics are generally performed on transaction data containing individual records of each transaction’s products, volume, prices, and discounts. The goal is to identify types of customers or transactions that are getting excessive discounts and then to trace the source of those discounts back to the pricing process in order to seal the profit leak by changing decision rights, developing new policies, or simply ensuring that mangers have the right data to make effective decisions. The source of the problem may range from a salesperson granting unwarranted discounts to a pricing policy that is not aligned with market conditions. The process compliance analytics we discuss below, price bands and price waterfalls, will not necessarily reveal what the corrective action for a bad outcome should be. The analytics will, however, help to pinpoint where the problem occurs, which is a useful first step toward correcting it.

EXHIBIT 11-11 Price Band Analysis

Price banding is a statistical technique for identifying which customers are paying significantly more or significantly less than the band of “peer” prices for a given type of transaction. This analysis identifies customers whose aggressive tactics enable them to earn unmerited discounts and customers who are paying more than average because they have not pushed hard enough for appropriate discounts. Exhibit 11-11 graphs the inconsistent, apparently random pattern of pricing that we often encounter at companies with flawed policies. However, the sales force or sales management team responsible might argue that there is a hidden logic to it—a method to the madness. To the extent that they are right, and sometimes they are, the pricing manager’s job is to make that logic transparent to herself and the pricing steering committee. To the extent that the variation is truly random, and therefore, damaging the firm’s profit and price integrity, the pricing committee’s job is to create policies to eliminate it.

There are five steps to a price band analysis:

Once the analysis is completed, the next step is to brainstorm possible causes of the random variation and identify correlations to test those hypotheses. For example, do a minority of sales reps account for most of the negative variation while a different group accounts for the positive? Is the negative-variation minority composed of the newest reps while the group accounting for the positive differences is more experienced? If so, the solution may be to document what the savvy reps know about selling value and sharing that information with the low-performing group. Other explanations for the random variation could relate to the customer’s buying process (is it centralized?), indicating a need for different policies. In one case, price-band analysis revealed a pattern that was ultimately traced to one sales rep in a particularly corrupt market who was taking bribes for price concessions.

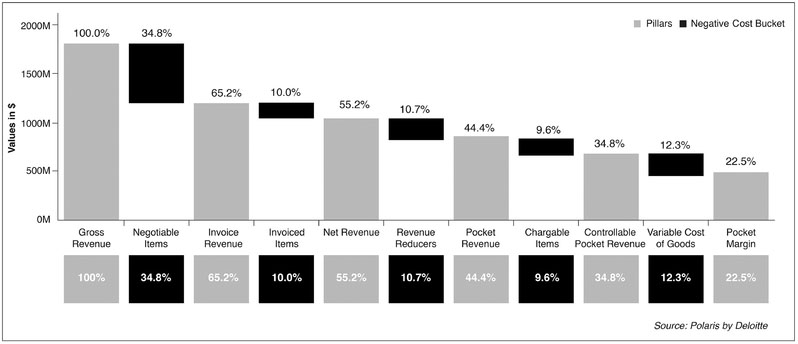

In some companies, the possible sources of lost revenue and profit are many and poorly tracked. In a classic and oft-quoted article, two McKinsey consultants used waterfall analysis to show how simply managing the plethora of discounts can improve company profitability.18 Exhibit 11-12 illustrates this price waterfall analysis. Although the company might estimate account profitability by the invoice price, there are often many other sources of profit

EXHIBIT 11-12 Price Waterfall Analysis

leakage along the way. The “pocket price,” revenue that is actually earned after all the discounts are netted out, is often much less. More important, the amount of leakage could range from very small to absurdly high. In one case, a company that analyzed its pocket prices discovered that sales to some of its customers resulted in more leakages than the gross margin at list price! In addition to the salesperson’s commission, there was a volume incentive for the retailer, a commission for the buying group to which the retailer belonged, a co-op advertising incentive, an incentive discount for the distributor to hold inventories, an early payment discount for the distributor, a coupon for the end customer, and various fees for processing the coupons.

Agreements to let the customer pay later, to let the customer place smaller orders, to give the customer an extra service at no cost and so on, all add up. The result can become a much wider variance in pocket prices than in invoice prices. Because companies often monitor such concessions less closely than explicit price discounts, these giveaways tend to grow. This does not mean that such discounts should be stopped; they often provide valuable incentives and can be effective in hiding discounts while still maintaining the important appearance of price integrity. The danger is simply in letting them go unmanaged, without applying rigid policies on their use. For example, after discovering that sales reps waived shipping charges for customers much more often than necessary, a large distributor imposed policies to require more documentation before such orders were processed. That simple policy change resulted in tens of millions more dollars to the bottom line.

Pricing systems generally need to perform two functions: (i) Support the data analytics described above; and (ii) enable the systematic execution of a chosen strategy.

There are several common software tools such as Excel and Tableau that allow most organizations to analyze their transaction data and assess their pricing performance. These tools can be used to generate the price waterfalls and price bands that were described in the prior section and offer a great starting point for assessing a firm’s pricing outcomes. As a firm scales its pricing practices and starts to standardize its analytics, there may be a desire to invest in specialized commercial pricing software products that are able to ingest real-time transaction data, systematically share outputs across the organization, and create automated alerts and interventions.

In addition, a pricing system should also enable an organization to execute its chosen pricing strategy in an efficient and repeatable manner. As an example of how pricing systems can present limitations, one of the authors recalls chaperoning his son’s class outing many years ago that included a stop at a McDonald’s for lunch. Wanting to impress two dozen third-graders with his pricing expertise, he asked the restaurant manager whether he could receive a 10 percent quantity discount for the class. The manager replied that he would gladly do so, but explained that his cash registers did not allow him to apply a percentage discount—each button on the register corresponded to a specific menu item with a pre-programmed price. So the question was rephrased: Would he be willing to provide 24 Happy Meals for the price of 22 Happy Meals? Reframed as a question of quantity and not percentages, the manager happily obliged because his pricing system allowed him to accommodate such a request. It should of course be noted that some systems limitations are very purposeful—it is not clear that the owner of the franchise would want cashiers to invent new pricing strategies. However, it is useful to consider how choices in systems design can enhance or hinder a company’s ability to execute a given pricing strategy.

Conversely, many of the world’s airlines have invested significantly in systems capabilities that allow them to implement an array of new pricing strategies to capture the value of transporting checked bags, offering window seats, providing in-flight meals or Wi-Fi access, among other services, allowing them to capture over $38 billion in non-ticket revenues in 2014.19

The trick to investing in pricing systems is to ensure that pricing strategy dictates the systems requirements, and not the other way around. For companies that have not yet invested in a clearly articulated pricing strategy, it is likely a mistake to invest in an industrial-grade pricing software system; these systems will offer configuration choices that a less-than-mature pricing organization will be unable to decide on. The reality is that too many companies adopt pricing technology that is seldom used or eventually abandoned. Preparing for change is not about writing a user manual and telling the organization to “go do.” Rather, any systems investment needs to be supported by an organizational culture change that is all about doing things in a new way. To assess a company’s readiness for a new pricing system, it is worth asking a few questions:20

The answers to these questions will help align the organization against the right type of pricing solution; the less developed the answer to these questions, the more likely a simpler solution is appropriate.

In terms of functionality, there are four distinct elements that are addressed by commercially available systems. The functionality that is common across all providers is the ability to perform pricing analytics. Key analytics include the ability to create price waterfalls and price bands that provide an overview of price and margin performance. Another common analytic is segmentation analytics, which can zero in on specific customer types, geographies, product categories and other attributes. Most pricing analytics systems include the ability to build dashboards and alerts to monitor pricing trends and activities.

The second functionality is price optimization, which is the execution of statistical models to calculate the price points that optimize against a given objective such as profit, unit volume or market share. Price optimization is valuable in cases where transaction volumes are large and data about all prices (yours and competitors’) is available. Retail grocery products, airlines seats, and hotel rooms are examples where it is easy to buy data for all retail prices available in the market as well as information about the context (e.g., how the product was displayed in the retail store, whether the travel was booked through an online site, a travel agent, or directly). Price optimization algorithms typically ingest large amounts of historical transaction data that includes price as well as promotions and any other marketing activities to estimate the impact of price on sales, or to estimate the impact of context and marketing efforts on the demand price elasticity.

A third functionality offered by many vendors is price management, which allows the user to set the rules and conditions that can automatically change prices in dynamic fashion. These tools allow the user to manage price lists by market, customer, and product category. Given the rules-based algorithms that adjust prices, this functionality allows firms to automate mass price updates that reflect real-time changes in market conditions. These systems are typically deeply integrated with a firm’s ERP system.

The forth functionality is called deal management, which pulls together the data needed to enable a sales person to negotiate more profitable quotes and contracts, while ensuring that the deal remains within the bounds defined by a firms pricing and discount policies. This functionality allows a sales person to perform scenario modeling for quotes and contracts when negotiating with a customer and can highlight how a customer might qualify for better pricing—by, for example, consolidating orders to minimize shipping costs, or making a slightly larger quantity to qualify for the next volume discount tier. Deal management is also used to capture any pricing approvals and to load the resulting customer-specific prices and terms into the order entry or ERP system.

For a more detailed discussion of pricing technology, we refer the reader to Pricing and Profitability Management by Julie Meehan et al.21

Organizational structure, decision rights, processes, and incentives are important levers that provide managers with the opportunity to make pricing choices in different and more profitable ways. Transforming an organization into one that commits to and executes on the principles of strategic pricing requires that managers act in ways that may run counter to their past experience and training. Some individuals may be resistant to change because they legitimately believe that the new approach is less effective, while others may be resistant because their compensation would be adversely affected under the new approach. Regardless of the reason, individuals must be motivated to go through a potentially uncomfortable transition process before accepting a new pricing strategy.

There are a number of levers that can be used to facilitate adoption of the new approach including clear leadership from senior management and demonstrating successes through trial projects. Successful change efforts require an integrated and consistent use of these change levers to overcome organizational inertia and effect change.

One of the most important actions that leaders can take to encourage adoption of strategic pricing is to truly “talk the talk and walk the walk.” All too often, senior managers indicate strong support for a new pricing strategy and then revert to ad hoc discounts the first time a customer asks for a lower price. Not only must senior leaders avoid falling back on old pricing practices, they must actively seek high-profile opportunities to demonstrate support for the new strategy. A telecommunications company we worked with had invested heavily to develop a more strategic approach to pricing in its consumer markets. The implementation plan included extensive training for the sales team and conducting a couple of high-profile negotiations with the new approach to demonstrate its effectiveness. The company seemed to be on its way to making a successful transition when the COO, who had been a tireless advocate for the strategy, began to respond to pressure from the board to meet sales targets by offering “one-time” discounts to win business. As soon as the regional sales managers learned about these discounts, they demanded the right to negotiate similar discounts. It was not long before these pricing “exceptions” became the norm across the organization and the pricing strategy was abandoned. In this example, the COO missed a critical opportunity to send a clear message about the organization’s commitment to the new strategy and, instead, began the process that left the organization stuck in its old pricing habits.

Senior managers have many opportunities to signal their support of a new pricing strategy. Specific actions they should consider include the following:

Perhaps the most important method for helping managers understand and adopt strategic pricing is the use of demonstration projects that test the new approach and provide an example of “what good looks like.” Successful demonstration projects can be pivotal in building momentum for the new approach and should be given as much exposure as possible. They should be designed to demonstrate the strategy and provide feedback and real outcomes from the commercial teams. They should be focused and of limited duration, or they risk losing the attention of the organization and undermining interest in the new strategy. A good example is when an entertainment company tested a new pricing strategy and price points by selecting a very specific post-holiday period and one focused metric to track growth in total gross profit. By focusing on a discrete period and clearly defining success, the organization built not only interest in the new strategy, but also credibility when it quickly declared the strategy a success and began a full rollout.

A challenge that must be overcome when designing a demonstration project is how to define a baseline for measurement. Skeptical managers across the organization will ask, “How do I know if it was the pricing strategy that drove the outcomes when there are so many moving parts in the market and with our own commercial activities?” The best and quickest way to address this concern is to treat the demonstration project as a price experiment in which two similar groups of customers are selected. One group receives the new strategy and new prices while the other maintains current prices and policies. This provides an objective measure of the effect of the new strategy and builds credibility within the organization. The consumer entertainment company did a thoughtful job of defining a control sample of similar products that were used to establish a baseline against which the new strategy could be tested. The positive results of the test were then distributed to everyone in the sales organization through webcasts and sales meetings. The test contributed significantly to the organization’s acceptance of the new prices.

One of the major benefits of demonstration projects is that the leaders of the project often become internal champions for the change effort. There is no better spokesperson for strategic pricing than someone who has experienced the outcomes first-hand. This is especially true for pricing, where even small barriers are seen as reason for abandoning an effort and sticking with the tried and true. Having more managers express confidence in the new pricing approach legitimizes the effort and provides confidence that it can lead to success. While having the most senior leader supporting an effort can be extremely important to success, there is also great value in having junior managers’ support as they face challenges similar to their peers, giving them strong credibility.

Progressive companies have been doing more than just worrying about pricing— they are actively making pricing a core part of their strategic capabilities. To drive profits in a low-growth economy, many are graduating from attempts to improve tactical price reactions to developing the capability to drive ongoing price improvement proactively. More than ever before, successful companies are building their businesses—including core products, ancillary services, and the business model itself—to support a pricing strategy rather than the other way around. Traditional industry leaders such as General Electric22 and Procter & Gamble23 have made explicit corporate decisions to change their focus from top-line growth to driving profitability growth. As they do so, they are changing not only the prices they charge, they are fundamentally altering the way they go to market, all with the aim of increasing the profitability of a sale.

Building pricing into a source of competitive advantage is one of the most challenging activities facing commercial leaders today. Success requires a combination of structural changes, such as building organizational alignment on the role of pricing, it requires investment in tools and data to inform decisions and monitor their implementation, and it requires building the knowledge base of the organization to understand the objectives of value-based pricing. The degree of change is substantial! We would be remiss if we did not acknowledge that the change process can often take years to complete. However, the data24 clearly show that the financial results justify the effort—firms that successfully complete the transformation to value-based pricing and build the supporting capabilities are significantly more profitable than their industry peers.

1. Charles Darwin, letter to Asa Grey, September 5, 1857. Accessed April 24, 2017 at www.darwinproject.ac.uk/commentary/evolution#quote4.

2. John Hogan, “Building a Leading Pricing Capability: Where Does Your Company Stack Up?” Deloitte, 2014. Accessed at www2.deloitte. com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/ Documents/strategy/us-consulting-building-a-leading-pricing-capabil ity.pdf.

3. P. H. McCaskey and D. L. Brady, “The Current Status of Course Offerings in Pricing in the Business Curriculum,” Journal of Product and Brand Management 16(5) (2007), pp. 358–361.

4. Kevin Mitchell, “The Current State of Pricing Practice at U.S. Firms,” opening speech, Professional Pricing Society Annual Spring Conference, May 30, 2011.

5. Georg Müller, Tom Nagle, and Lisa Thompson, “Everything Manufacturers Want to Know About Raising Prices but Are Afraid to Ask,” Deloitte DBrief presentation, May 28, 2015.

6. Shantanu Dutta, Mark Bergen, Daniel Levy, Mark Ritson, and Mark Zbaracki, “Pricing as a Strategic Capability,” MIT Sloan Management Review (Spring 2002), pp. 61–66.

7. Dirk Beveridge, “After Record Losses, Airline Industry Sees Bleak 1992,” Associated Press, January 6, 1992, via Post Bulletin, Rochester, MN. Accessed at www.postbulletin.com/after-recordlosses-airline-industry-sees-bleak/article_7a0f913d-69c7-5a9d-ad29-99fd04a42472.html?mode=jqm.

8. Andreas Hinterhuber, “Value Quantification Capabilities in Industrial Markets,” Journal of Business Research 76 (July 2017), pp. 163–178. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres. 2016.11.019.

9. Peter Kafka, “Apple and Spotify Are Generating $7 Billion a Year in Streaming Music Revenue,” Recode, December 7, 2016. Accessed at www.recode.net/2016/12/7/13864776/apple-spotify-60-million-subscribers-7-billion-revenue.

10. Vincent Barabba, The Decision Loom: A Design or Interactive Thinking in Organizations (Devon: Triarchy Press, 2011).

11. Leena Rao, “Amazon’s Third Bookstore Will Be in Portland,” Fortune, June 15, 2016. Accessed at http://fortune.com/2016/06/15/amazon-store-portland.

12. James G. March, “Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning,” Organization Science 2(1), Special Issue: Organizational Learnings: Papers in Honor of (and by) James G. March (1991), pp. 71–87.

13. Jason O. Gilbert, “Netflix Price Increase Causes Bigger Subscriber Loss Than Expected,” Huffington Post, September 15, 2011. Accessed at www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/09/15/netflix-price-increase-subscriber-loss_n_964026.html.

14. “The Impact of Netflix’s Price Rise,” by contributors from Trefis, Forbes.com, May 15, 2014. Accessed at www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2014/05/15/the-impact-of-netflixs-price-rise.

15. “Airline Fluctuations: Can a Flight Price Really Change 135 Times?” blog at Cheapair.com, January 21, 2014. Accessed at www.cheapair.com/blog/travel-tips/airfare-fluctuations-can-a-flight-price-really-change-135-times.

16. Hogan, op. cit .

17. Lecture on “Electrical Units of Measurement” (3 May 1883), published in Popular Lectures Vol. I, p. 73 .

18. Michael Marn and Robert Rosiello, “Managing Price, Gaining Profit,” Harvard Business Review (September–October 1992).

19. Martha C. White, “More Fees Propel Airlines’ Profits, and Embitter Travelers,” New York Times, July 27, 2015. Accessed at www.nytimes.com/2015/07/28/business/more-fees-propel-airlines-profits-and-embitter-travelers.html.

20. Questions adapted from “Your Pricing Technology Journey,” Monitor Deloitte white paper, 2016. Accessed at www2.deloitte. com/us/en/pages/operations/ articles/pricing-technology-jour ney.html.

21. Julie M. Meehan, Michael G. Simonetto, Larry Montan Jr., and Christopher A. Goodin, Pricing and Profitability Management (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2011).

22. “GE to Create Simpler, More Valuable Industrial Company by Selling Most GE Capital Assets; Potential to Return More than $90 Billion to Investors Through 2018 in Dividends, Buyback and Synchrony Exchange,” General Electric press release, April 10, 2015.

23. Procter & Gamble 2016 annual report. See also Rachel Abrams, “P&G Sells 43 Beauty Brands to Coty,” New York Times, July 9, 2015.

24. Hogan, op. cit. Also see: Stefan Michel, “Capture More Value,” Harvard Business Review (October 2014).