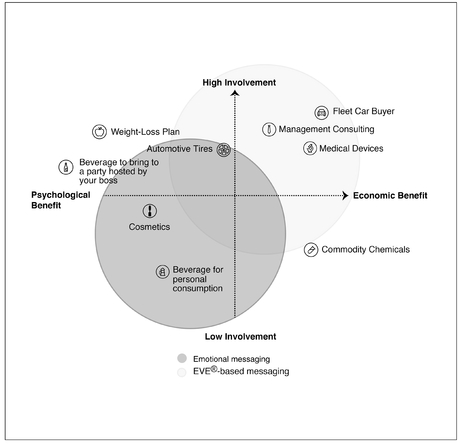

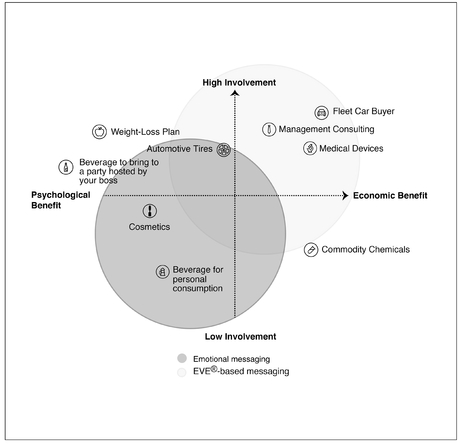

EXHIBIT 3-1 Purchase Involvement and Benefit Types for Products and Services

Strategies to Influence Willingness-to-Pay

Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing.

Oscar Wilde1

In Chapter 2, we argued that developing an effective pricing strategy requires understanding the value of your offer in order to set profit-maximizing prices across segments. Yet even the most carefully constructed value-based pricing strategy will fail unless your offer’s value, and how it differs from a competitor’s, is actually understood by potential customers. Although getting a good value is often one of the most important purchase considerations, customers who do not recognize your differential value are vulnerable to buying inferior offerings at lower prices supported by loosely defined performance claims. The role of value and price communications, therefore, is to convey your value proposition in a compelling manner to accomplish three goals: Enable customers to fully understand the benefits; improve their willingness-to-pay; and increase the likelihood of purchase.

In our research, we have found that business managers rated “communicating value and price” as the most important capability necessary to enable their pricing strategies.2 Ironically, the same study found that the ability to communicate value is also one of the weakest capabilities in most sales and marketing organizations. In retrospect, these results are not surprising because effective value and price communications require a deep understanding of customer value (which many firms lack) combined with a detailed understanding of how and why customers buy (another shortcoming) to formulate messages that actually influence purchase behaviors.

Both sellers and buyers have made value communication complicated. Among sellers, value communication often gets substituted by “feature communication,” whereby sellers point to extensive product specifications in the hopes that the buyer is able to recognize where and how these features might deliver some benefits. Mobile phones are often advertised to have “64GB memory” or “4G connectivity,” yet few sellers translate these features into customer benefits such the ability to store a specific number of pictures or relative improvements in reception quality. As a result, the seller forces the customer to divine the potential benefits that these features convey. Invariably this leads to a loss in fidelity especially among the less-experienced buyers and those lacking the time to perform research.

Simultaneously, the buyer, especially in B2B settings, is not incentivized to figure out the relative value propositions. When confronted with a choice between a cheap offer and a more expensive one with hard-to-understand benefits, the easiest path for a purchasing agent is to simply buy the lowest priced offer. He can easily justify the decision based on the cost savings, summarize his decision in a quick memo, and get home early for his son’s baseball game. On the other hand, to buy the more expensive offer, the agent needs to understand why his organization prefers it, document the economic benefits of using it, and write up a memo summarizing why the price premium is justified. This effort takes time and may require the agent to stay late at the office. A major goal for value communication is to provide the agent with the information needed to justify paying a higher price.

A third challenge in value communication is that marketers often assume that market demand is fixed and that the market alone will determine the price that a buyer is willing to pay. Yet this assumption is not true. Even in the most commoditized of markets, there are ways to differentiate an offering and reframe how buyers make price comparisons. Buying a set of new tires for the family minivan is a task rarely greeted with any enthusiasm. When confronted with an array of choices at the tire store and lacking any knowledge of the category, many consumers will treat the products as a commodity and instinctively select a lower-priced tire offered in the store. However, after the same consumer notices a Michelin advertisement, with a plump baby sitting in the middle of a tire with an admonition to “Remember what is riding on your tires,” automotive tires suddenly get reframed as important safety devices, and the premium charged for a Michelin tire is but a small payment for improved safety.

A fourth challenge is that in order to sell on value, you need to sell to the person that recognizes the value. Especially in business-to-business environments, there are usually multiple stakeholders involved in a purchase decision, and each stakeholder values different aspects of the offer. When selling flexible packaging materials to a CPG company, plant managers will value the technical support, the brand manager will be interested in the graphics capabilities that allow a product to stand out on a grocery store shelf, and the procurement group wants to understand the costs savings over the incumbent supplier. A seller needs to break down their value story into discrete messages and deliver the most relevant story to each stakeholder in the buying process.

The purpose of this chapter is to explain how to develop compelling messages that convey the value of key product characteristics of your offering to the right people. This chapter will explore how to leverage quantifiable benefits defined by the Economic Value Estimation (EVE ®) model as well as how to use principles of behavioral economics to create messages that resonate more powerfully. We will also discuss how to adapt the message across different types of products and different purchase occasions. And importantly, will show how effective value communication can influence willingness-to-pay, shape market demand, and make it easier for the buyer to justify paying a price premium for more value.

Value communication can have a great effect on sales and price realization when your product or service creates value that is not otherwise obvious to potential buyers. The less experience a customer has in a market or the more innovative a product’s benefits, the more likely it is that the customer will not recognize nor fully appreciate the value of a product or service. For example, without an explicit message from the seller, a business buyer might not realize that a nearby distribution center offering shorter delivery times could reduce or eliminate the cost of carrying inventories or even recognize how quickly inventoried items depreciate. Properly informed, the customer would see how much money faster delivery saves, justifying a price premium.

In addition, a buyer’s perceptions of value are shaped by the way information is conveyed. For example, by highlighting that the cost of a pharmaceutical drug is covered by insurance, the role of price becomes less relevant and the buyer is able to focus on other aspects of the message such as the relative efficacy of the drug.

The first step in developing a value message is determining which customer perceptions to influence. We start with an understanding of the value drivers that are deemed most important to a customer segment. The goal is to help the customer recognize the linkages between a product’s most important differentiated features and the salient value drivers. The two dimensions that frame a communications strategy are: (i) The type of value delivered—economic or psychological; and (ii) the degree of buyer involvement—do they actively seek information to make detailed comparisons or do they make a decision based on what is known in the moment? Exhibit 3-1 summaries these dimensions.

Understanding the type of value sought has a significant implication for the communication strategy. Measurable monetary benefits such as profit, cost savings, or productivity motivate many purchases and translate directly into quantified value differences among competing offers. But for other purchases, especially consumer products, psychological benefits such as comfort, appearance, pleasure, status, health, or personal fulfillment play a critical role in customer choice. Although the value of both psychological and monetary value drivers can be quantified, the way in which that data should be used in market communications differs. For goods in which monetary value drivers are most important to the customer, value quantification should be a central part of the message because the data calls attention to any gaps between the customer’s perceptions of value and the actual monetary value of the product. For psychological benefits the value messaging will focus on how a product will make the customer feel, much like the tire example cited earlier.

It is important to note that virtually every purchase has an economic and a psychological element to it—for example, the purchaser of an electric car may feel significant benefits from the virtues of protecting the environment, yet justifying the price premium will require communication of the potential fuel and operating cost savings during ownership. Likewise, purchase of a weight-loss program may be primarily driven by psychological factors such as a desire to improve one’s physical appearance or to feel more physically fit. However, there is also a potential economic factor in play. In this case, research has shown that obesity can lead to earnings that are lower for both men and women,3 so attaining a healthy weight can have monetary benefits as well.

EXHIBIT 3-1 Purchase Involvement and Benefit Types for Products and Services

Another example of combining financial and psychological value messages occurred when a medical device manufacturer had to justify a substantial price premium for its drug-coated coronary stent used to keep clogged arteries open. The company priced its stent at $3,500—twice the price of traditional uncoated stents and well in excess of the cost of the drug used to coat the stent. Such aggressive pricing aroused critics in the medical professions and in the media who accused the company of price gouging and challenged the company to reconcile the value of the new product with its price. The manufacturer did so by explaining the economic benefits to medical professionals. Stent implantation surgery costs more than $30,000, including the cost of the stent. But in 20 percent of cases, an uncoated stent reclogs in less than a year, requiring a repeated procedure at another $30,000 cost. With its new drugeluting stent reducing the likelihood of reclogging, the surgery repeat rate fell to around 5 percent. Thus, the objective differentiation value from the smaller reclogging rate was $4,500: The 15 percent rejection rate difference multiplied by the cost of a second surgical procedure. In addition, patients received substantial psychological value in avoiding the risk and discomfort of a repeat procedure, a benefit the company emphasized to the public. The combination of economic and psychological justification enabled the company to not only win a larger reimbursement from payers when surgeons used its drug-eluting stent but also to defuse the initial hostility and resistance to its price.

The degree of buyer involvement varies dramatically from one product category to the next as well as across purchase occasions. The level of involvement tends to increase when the purchase is more expensive. A $5 purchase may not require much consideration, but spending an hour evaluating alternatives before spending $5,000 would seem merely prudent. And for larger purchases, the level of due diligence can increase; a fleet buyer planning to purchase 2,000 cars may even consider buying several models and testing them for three months to fully understand the relative differences across each model. Involvement also increases when the item purchased is being used in a high visibility environment. For example, purchase of a six-pack of beer might be quite routine when it is for personal consumption. However, when a six-pack is purchased as a gift for the host of a garden party, the level of thought and consideration rises. If the host happens to be your boss, you may opt for a more expensive brand than your usual choice. If the recipient is a beer connoisseur, you may choose an unusual microbrew. If the party has a salsa theme, you may choose a brand brewed in Mexico.

Low-involvement goods whose benefits are mostly psychological include many consumer packaged goods, cosmetics, or apparel (although the authors fully recognize the existence of some consumers who are very passionate about these categories and treat them as high-involvement purchases). Many of these products are sufficiently low in cost that consumers do not find it worthwhile to conduct extensive research prior to making a purchase. Instead, simply trialing multiple brands over time is the more efficient way to establish a personal preference. For products of this nature, the role of value communications will focus on the psychological benefits as well as creating offers that make it easier to try out the product. Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign conveys little about the economic value of its products, but reinforces the psychological: Buying our products lets you be the athlete you want to be! The messaging is further reinforced by the Nike stores that allow consumers to “get close” to their favorite athletes through unique in-store experiences.

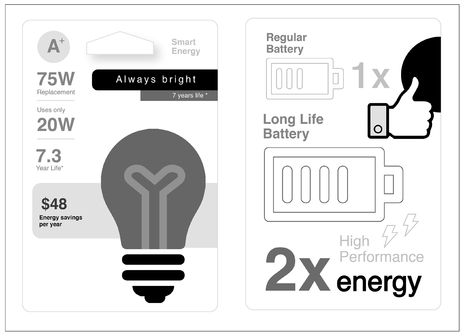

Many low-involvement products can have benefits that are predominantly economic. For example GE’s energy efficient light bulbs are supported by the “Energy Smart, Bright from the Start” campaign in which each package of GE compact fluorescent bulbs contains a claim about the cost savings a consumer could achieve through reduced power consumption as well as improved longevity—and commensurate reduction in replacement costs—associated with the bulb (Exhibit 3-2).

EXHIBIT 3-2Economic Value Messages for Low-Involvement Goods

An example of a product that falls in the upper-left quadrant of Exhibit 3-1 would be the purchase of the weight-loss program referenced earlier. Engaging in such a program is usually the outcome of a careful personal decision and requires the evaluation of many competing offers such as gym memberships, dietary supplements, pre-packaged meal programs or, in some cases, even surgical interventions. The potential psychological benefits are enormous and for most consumers take precedence over the economic benefits. The role of celebrity endorsements such as Oprah Winfrey’s promotion of Weight Watchers, customer testimonials such as actress Kirstie Alley for the Jenny Craig weight-loss program, or trial membership at a gym may make it easier to try the product.

Finally, high involvement products that deliver primarily economic benefits include services such as management consulting and university educations, as well as products such as airplane engines and surgical devices. A key decision criterion in the purchase of each of these products is their relative economic benefit in the form of labor efficiency, future earnings potential, fuel savings, or treatment costs. At the same time, given the cost and magnitude of potential benefits, purchase in any of these categories tends to be a high involvement activity. The decision is carefully deliberated with consultation of many involved in the purchase decision; data is collected on the relative performance levels of each alternative; and an evaluation of benefits relative to any cost differentials is carefully studied.

An interesting observation is that as customers gain expertise, the level of involvement can change, and so does the value messaging. A technophile can read the feature specifications for a laptop computer and quickly infer how it will perform various tasks. A more typical buyer, however, would have to do considerably more research and test various offerings to make the same inferences. As a result, less sophisticated buyers often develop strategies to lower search costs such as purchasing a known brand or relying on the advice of an expert. The endorsement of an expert can be very powerful, even in business markets. For example, Kaiser Permanente, a western U.S. health maintenance organization, has a reputation for being a well-informed buyer of cost-effective medical products. The company often tests drugs and devices itself and will not buy a more expensive product without economic justification.4 Consequently, when other hospitals and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) learn that Kaiser Permanente has adopted a more expensive product or service, they may assume that its price premium is cost-justified.

Most market research on willingness-to-pay relies heavily on the assumption that purchase decisions are motivated by considerations of value delivered—whether economic or psychological. What distinguishes useful from misleading research is the extent to which the researcher accounts for differences between the assumptions of this basic model and the way customers in a particular market actually make decisions. Unfortunately, many researchers design a study assuming full knowledge of the prices and features of common substitutes without first determining how much consumers actually know about the substitutes when making a purchase. These studies may show how well-informed consumers may choose, but are rarely reflective of actual market conditions.

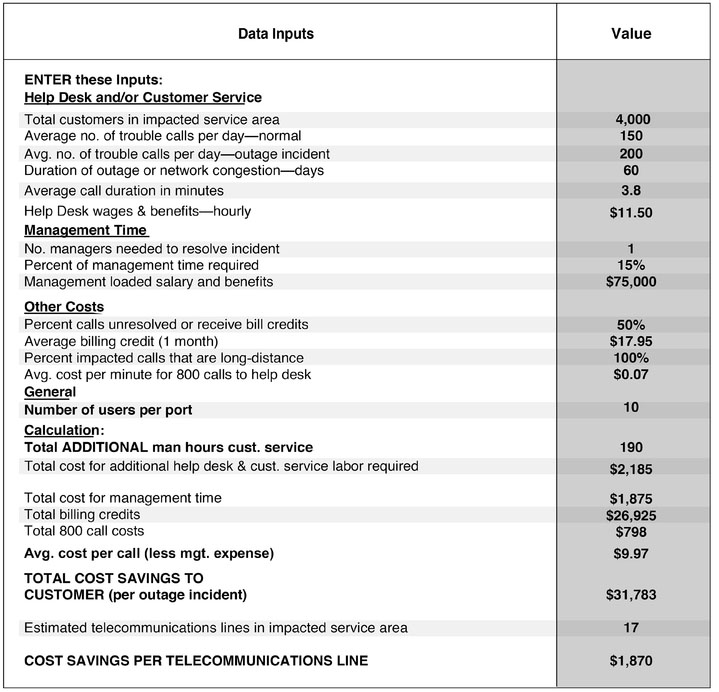

When the benefits are mostly economic, value communication needs to be a central part of the message in order to educate the customer on the actual value delivered. One of the best ways to convey economic value is to leverage the EVE ® model that was described in Chapter 2. Exhibit 3-3 shows an example of a value-based selling tool used by salespeople to develop a customer-specific estimate of the value from installing a piece of telecom equipment that reduces the service outages and the corresponding number of calls from affected customers to a service center. While this example is only illustrative, notice that the data and assumptions, derived from the value estimation model, are well documented and quite detailed. While inexperienced salespeople sometimes fear that they will be challenged if they make value claims, more experienced salespeople relish the opportunity to engage in give-and-take conversations about precisely how much value their product creates. Only in that context can a salesperson justify a price premium that might otherwise seem unacceptable to a business buyer who is not the actual user of the product. A key benefit of the EVE® model is that it can be displayed on a salesperson’s laptop or tablet, as an interactive tool where key customer parameters as well as the characteristics of competitive products can be entered to illustrate the value proposition.

EXHIBIT 3-3 Spreadsheet Value Communication Tool

When the important value drivers for a purchase decision are psychological rather than monetary, it is best to avoid incorporating quantified value estimates into market communications because value is subjective and will vary from individual to individual. However, one should not conclude that subjective values, such as those that a customer might reveal in a conjoint research study, cannot be influenced by communication. There are two ways to do this. One is to focus the message on high-value benefits that the customer might not have been thinking about when considering the differentiating features of the product. The second is to raise perceptions of the product’s performance benefits that cannot be easily judged prior to experiencing them. Batteries all look and feel the same, even after one begins to use them. Not until they are entirely consumed can one actually know the life, and even then one would have no comparison unless two brands were bought and used in identical devices. It is perhaps no surprise that a certain leading battery maker has developed a battery powered toy rabbit into an iconic marketing mascot as a way to explain the long life of its batteries. The advertisements do not need to make any explicit mention of pricing or relative battery life; the ability of the toy to operate seemingly forever is enough to convey the message.

Estimating economic value to the customer is fundamental to marketing in general and to pricing in particular, but it is just one facet of the role of price in customer decision-making. When dealing with knowledgeable and sophisticated purchasers (such as specialized purchasing agents or a dedicated bargain hunter), economic value analysis can describe and predict buyer behavior quite adequately. However, most customers, even those in B2B environments, do not make purchase decisions exactly as economic value analysis would indicate. Although getting good value is usually a critical purchase consideration, customers will not always choose the very best value. And in cases where economic value is not apparent such as the purchase of a bottle of wine, buyers will revert to heuristics and market signals when making purchase decisions.

The role of non-economic factors becomes more important when the expenditure is small or when someone else is paying the bill, the effort of diligently evaluating all the alternatives is not worth the effort. At other times, being aware of alternatives or being unable to evaluate them before purchase makes finding the best deal too difficult or risky. Occasionally, the desire to impress others leads buyers to choose high-priced offerings as is sometimes the case with luxury automobiles. Considerations like these often mitigate the importance of economic value relative to the importance of psychological factors such as prestige, convenience, safety, or fairness.

These considerations tend to fly in the face of traditional economics which has always posited that economic actors (buyers and consumers) are rational and fully informed about competing offers. The exploding field of behavioral economics has shown that people rarely fulfill the criteria of being well informed or rational. Instead, buyers often depart from economic rationality in systematic and predictable ways. In other words, buying decisions and the corresponding evaluations of price points are replete with market and business process inefficiencies. As noted behavioral economist Richard Thaler describes it:

[Economically rational actors] are really smart. They know as much about economics as the best economist. They make perfect forecasts, have no self-control problems and are complete jerks. They’ll steal your money if they can and get away with it . . . Most of the people that I meet don’t have any of those qualities. They have trouble balancing their checkbook without a spreadsheet. They eat too much and save too little. But nevertheless they’ll leave a tip at a restaurant even if they don’t plan to go back.5

Applied to the world of pricing, creating an effective strategy to convey the psychological values of an offering requires consideration of several critical effects influencing buyer behavior that have been developed in the literature on behavioral economics. Following is a summary of the most common effects and their influence on a buyer’s perception of value and their consequent sensitivity to price.

True value is what is perceived by consumers who are fully informed of alternatives, understand the benefits of differentiation, and act in rational ways. In the real world, however, such customers are few and far between. Either they do not have enough time to make informed decisions, are floundering in data, or do not understand the consequences of poor choices. As a result, they will resort to heuristics and other mental shortcuts to help guide the decision process. Restaurateurs in resort areas face less pressure to compete on price, in spite of the higher concentration of restaurants in those areas because their transient clientele is usually unaware of better alternatives. Instead they focus on the “signals” that influence how tourists choose—convenient locations, good signage, and close relationships with local concierges who can steer customers to favored restaurants. Local residents view the restaurants near resorts as “tourist traps,” precisely because they can charge higher prices than restaurants less visible to tourists but patronized by a more informed clientele.

One of the most common shortcuts is to find a competitive reference product—often a highly visible and high-cost brand in the market—to assess relative value. By managing a customer’s understanding of the relevant competitive alternatives, a seller can significantly influence the customer’s willingness-to-pay. Woolite laundry detergent has successfully defended a significant price premium compared to conventional detergents by reframing their product as an alternative to dry cleaning. In other words, by shifting the customer’s attention to the cost of a dry cleaner and reminding audiences that Woolite is intended for the more delicate clothes in one’s wardrobe, the brand is viewed as a bargain relative to a drycleaner instead of a premium against conventional detergents.

Presented with an array of choices, and absent much knowledge of the category, customers’ perception of value is influenced by the range of prices available to them at the time of purchase. Most will choose options in the middle of the assortment. They engage in an internal debate on not being too cheap, nor appearing too extravagant and as a result tend to make an intermediate selection. For example, a business machine company with three models in its line found the sales of the top-end model disappointing. The company believed that many customers would benefit from the additional features of the high-end model, yet customers were buying the mid-tier model. Management’s initial assumption was that the high-priced model must be too expensive. After interviewing customers however, they learned that most did not think that the product was overpriced. Rather, they simply could not overcome the objections of the financial controllers that the company did not need “the most expensive model.” The solution: The company introduced a fourth, even more expensive model to its line. The new model sold poorly, but sales of the previously top-end model increased dramatically.

We see similar strategies play out on restaurant wine lists. We often amuse ourselves thinking about which customer might be the one ordering the $3,700 bottle of 2010 Chateau Petrus on the menu. The reality is that this offering is rarely purchased. In fact, it is often not even in the wine cellar! Its inclusion on the wine list serves merely as a decoy to signal to the diner considering a $30 bottle that this establishment is really the kind of place where a $70 bottle is more appropriate.

Buyers are less sensitive to the price of a product as the added costs (both monetary and non-monetary) of switching a supplier rises. The reason for this effect is that many products require that the buyer make product-specific investments to use them. If those investments do not need to be repeated when buying from the current supplier, but do when buying from a new supplier, that difference is a switching cost that limits inter-brand price sensitivity. For example, an airline may be reluctant to change suppliers, from say, Boeing to Airbus planes, because of the added cost to retrain their mechanics and to invest in a new stock of spare parts. Once an airline begins buying from a supplier, it may take a very attractive offer from a competitor to induce them to switch. Similarly, even personal relationships can represent significant intangible investments that limit the attractiveness of a competing offer. For example, busy executives must invest considerable time in developing rapport with their accountants, lawyers, and childcare providers. Once these personal “investments” are made, they are reluctant to repeat them simply because another otherwise qualified supplier offers a lower price.

This is the switching cost effect: The greater the product-specific investment that a buyer must make to switch suppliers, the less price sensitive that buyer is when choosing between alternatives. Since this effect is most often attributed simply to inertia, it is easy to underestimate its predictability and manageability.

In a recent project involving a food ingredient that was coming off patent, buyers at large CPG companies immediately demanded that prices come down to match the price of the new generic supplier. On the surface, their demands made a lot of sense – the generics were indeed identical, right down to the molecular structure. However, a closer analysis revealed that there were significant switching costs. Any new supplier would have to go through a rigorous qualification process that typically took three to six months to complete, involved factory audits, and pilot runs. Supply chain logistics would need to be redesigned to reflect that the generics were produced abroad and not locally. And because the generics had a long route to market, any customer would have to establish a local warehouse with buffer inventory in case there was a disruption to a shipping channel. When these significant switching costs were considered, the economic incentive to switch to a lower-cost supplier evaporated and the incumbent was able to continue charging a price premium.

The concept of economic value assumes that customers can actually compare what the alternative suppliers have to offer. In fact, it is often quite difficult to determine the true attributes of a product or service prior to purchase. For example, when a child suffers from a fever, a parent may be aware of the many alternate flu remedies that are cheaper than their usual brand and claim equal efficacy. But if they are unsure that these brands are technically identical to the one they usually buy, or if they doubt that the cheaper brand will be as effective, they will not consider them perfect substitutes. Consequently, they will often continue to pay higher prices for the assurance that their regular brand offers what the substitutes do not: The confidence accumulated from past experience that their brand can do what the others only promise to do.

Branded grocery products are often packaged in unusual shapes and sizes making price comparisons with cheaper brands difficult. When, however, stores offer unit pricing (showing the price of all products by the ounce or gallon), grocery shoppers can readily identify the cheaper brands. In one study of unit pricing, the market shares of cheaper brands increased substantially after stores ranked brands by unit price.6

These examples illustrate the difficult-comparison effect: Buyers are less sensitive to the price of a known or reputable supplier when they have difficulty comparing alternatives. Rather than attempting to find the best value in the market and risk a poor value in the process, many purchasers simply settle for what they are confident will be a satisfactory purchase. Their confidence in a brand’s reputation may be based on either their own experience with the brand or on the experience of other people whose judgement they trust. Examples of suppliers whose profitability rests on the trust that consumers associate with their names include McDonald’s, KitchenAid, and Marriott. The trust for which buyers will pay price premiums is not that sellers of these brands will necessarily provide the highest quality, but rather that they will consistently provide the good value-for-money that buyers come to expect from them.

The same principle applies to business markets. Industrial buyers are commonly thought to seek many suppliers whom they play against one another for lower prices. In fact, industrial buyers usually follow such a policy only for those products whose quality and reliability they can easily evaluate at the time of purchase. When products are difficult to evaluate and the cost of failure is high, industrial purchasers are at least as brand loyal, and as price insensitive, as are household buyers. In fact, for purchases that are relatively risky and difficult to evaluate (such as new plant construction, consulting services, or incorporating a new technology into an existing product formulation), industrial buyers will often develop loyal relationships with a list of approved suppliers with whom they have had a satisfactory experience.7 They will not even consider purchasing from an unknown supplier, even though that supplier claims to offer the same quality at a lower price. The cost of switching a supplier—both real economic costs as well as personal career risks—should be important factors for any seller of a product that is suddenly facing a low-cost competitor.

A buyer’s price sensitivity is influenced by the importance of the benefit that they are trying to derive from their purchase. Many years ago IBM used the slogan “No one ever got fired for buying Big Blue,” a message that was aimed, not at the user of their business machines, but at the purchasing agent to remind him that he faced a very personal risk if he procured a less well-known brand that did not deliver the desired performance.

The importance of the end result is a critical driver of the end-benefit effect. The greater the risk and the higher the cost of failure, the more salient this effect becomes. Consider the Boeing 787 jetliner. One of the significant innovations in its design is that it is constructed from a composite material that is lighter and stronger than aluminum. One interesting aspect of working with composites is that mechanical fasteners such as rivets are no longer used to join parts together. Instead, significant assemblies like the wings are attached to the fuselage using glue.8 And while the glue is very similar to the adhesives you might find in a hardware store, given the high stakes of failure, the glue purchased by Boeing is aircraft grade, which is subject to substantially higher quality controls, additional certifications, and costs significantly more.

Generally, price represents nothing more than the money a buyer must give to the seller as part of the purchase agreement. For a few products, however, the price means much more and the old adage, “ you get what you pay for ” has special resonance. These products fall into three categories: Image products, exclusive products, and products without any other cues to their relative quality. In these cases, the price is more than just an attribute, it is also a signal of the value that a buyer can expect to receive. In such cases, a customer’s willingness-to-pay is influenced by the price-quality effect, which states that buyers are positively influenced by a higher price, because it may signal better quality.

A buyer might use price as a quality signal for a number of reasons. Consider what motivates the purchase of an obvious image product such as a Rolex watch. In terms of tangible value—the ability to keep accurate time— a smartphone incorporates all sorts of new technologies that have increased the accuracy of timekeeping since the invention of the chronometer by John Harrison who created Sea Watch No. 1 (H-4) in 1759, the first device to track time accurately enough for nautical navigation.9 While the Rolex uses many of the same design principles of Harrison’s invention (and loses or gains up to 2 seconds per day due to the limits of mechanical devices), the time on a smart-phone is continually updated to an atomic clock via its cellphone tower network. And a smartphone costs less than one-tenth of the price of a Rolex! But buyers of a Rolex do not purchase the watch as a cost-effective timekeeper any more than they buy a Porsche as cost-effective transportation. They buy these items in part to communicate to others that they can afford them. They pay a premium for the confidence that their Rolex’s uniquely expensive method of production ensures its continued value as a status of wealth.

Consumers often value such symbols when the product reflects on them personally. Consequently, brands that can offer the consumer prestige in addition to the direct benefits of consumption that can, and must, command higher prices than less prestigious products. In many luxury goods categories, a consumer’s price sensitivity decreases to the degree to which they value the recognition or ego gratification that the premium brand gives them.

One of the authors regularly marvels at the many advertisements for prestige goods that are placed in the Sunday New York Times. Are these advertisements intended to prompt the reader to purchase a luxury good for a spouse? Perhaps. But another conjecture is that the ads are placed on behalf of consumers who have already purchased the luxury good. That is, the purchase of an expensive prestige good enters the buyer into an implicit agreement with the seller whereby the seller agrees to communicate to buyer’s friends and neighbors just how special (and expensive) their recent purchase was.

A prestige image is only one reason that buyers might find a more expensive purchase more satisfying. The exclusivity that discourages some people from buying at a high price can, in addition to image, add objectively to the value. Many professionals—doctors, dentists, attorneys, and hairdressers— set high prices to limit their clientele enabling them to schedule clients farther apart. This ensures that each one will be served without delay at the appointed time, a valuable service for busy people. Some business travelers choose to fly first class, not because of the leg room or the food, but because the high price reduces the probability of sitting next to a noisy child or a loquacious vacationer who might interfere with the work they must do on the flight.

Often, the perception of higher quality at higher prices reduces price sensitivity even when consumers seek neither prestige nor exclusivity. This occurs when potential buyers cannot ascertain the objective quality of a product before purchase and lack other cues such as known brand names, country of origin, or a trusted endorsement to guide their decision. In these cases, consumers will often rely on the relative prices of the offerings as a cue to a product’s relative quality, apparently assuming that a higher price is probably justified by a correspondingly higher value.

In an experiment performed at Cal Tech,10 researchers found that increasing the stated price of a wine resulted in higher taste test ratings by consumers. When presented with wines that were priced at $5, $10, $35, $45, and $90 per bottle, consumers consistently preferred the $90 wine to the $5 wine, and preferred the $45 bottle to the $35 bottle. The catch, however, was that while subjects were told that they would taste five different wines, they in fact only tasted three. The $90 wine actually retailed at that price, but was represented to subjects as both a $90 as well as a $10 bottle wine. When it cost $90, subjects loved the wine; at $10 they did not like it as much. The additional fascinating finding from this research was that all subjects were connected to an MRI machine while they were doing the wine tasting, and the brain scans showed that when sampling the expensive wine, the medial orbitofrontal cortex—the part of the brain that registers pleasure—showed higher activity than when subjects were tasting the lower-priced wines. Finally, in a follow-up experiment where subjects tasted the wine samples without any price information, the cheapest wine was most preferred.

Price can also influence the actual effectiveness of a product. In an experiment where students about to take an exam were offered an energy drink that was sold either at regular price or at a discount, those who paid full price performed better on the exam.11 Even though everything else was identical—product, packaging, and branding—simply selling the item at a discount led to a poorer test performance relative to those who purchased their energy drink at full price. It makes one wonder whether it is a good idea to label off-brand drugs as generics and convince consumers that they will benefit from the cost savings over the branded version. Perhaps it could be a better idea to label generics as “ brand-equivalent, clinically-approved therapy,” and charge consumers a little more?

The expenditure effect states that buyers are more price sensitive when the expenditure is larger, either in dollar terms or as a percentage of available budget. As the expenditure increases, the potential return to shopping around for a better deal increases. On the other hand, small impulse purchases are simply not worth any effort to ensure that the price is a good deal. This partially explains why large transactions such as buying a full case of soda is cheaper – and even accompanied by additional promotions – while the purchase of a single can of soda from the cooler in the checkout line is significantly more expensive on a per-unit basis and rarely discounted.

The effect of the expenditure size on price sensitivity is confounded in consumer markets by the effect of income. A family with five children may spend substantially more on food than a smaller family, yet still be less price sensitive if the cost of food accounts for a smaller portion of the large family’s high income. This relationship between a buyer’s price sensitivity and the percentage of income devoted to the product results from the trade-offs buyers must make between conserving their limited income and conserving the limited time they have to shop. Higher-income buyers can afford a wider variety of goods but cannot always afford more time to shop for them. Consequently, they cannot afford to shop as carefully as lower-income buyers and so they accept higher prices as a substitute for time spent shopping.12

The expenditure’s size relative to income is also a constraint on both a business’s and a household’s primary demand for a product. A young man may long for a sports car believing that a Porsche clearly has differentiating attributes (such as handling and engine performance) that justify its premium price relative to similar cars. However, at his low income he is not making a purchase decision among sports cars. His budget is currently consumed by more important expenditures such as food, rent, and education. Until his income rises, or the price of sports cars drops, his preference within the category is not relevant.

Successful marketers of premium products will reframe premium prices in a different context to lower the buyer’s price sensitivity. Life insurance is a product that is particularly useful for a young family that has significant long-term financial obligations in raising children, yet is at a life stage where their present budget can’t cover all of their future needs. By offering different coverage levels and by breaking down an annual cost into quarterly payments—or even a daily cost “only $0.37/day!”—the purchase can be framed in a manner that makes it seem much more affordable even to a cash-strapped young family.

Although the portion of the benefit accounted for by the product’s price is an important determinant of price sensitivity, so is the portion of that price that is actually paid by the buyer. People purchase many products that are actually paid for in whole or in part by someone else. Insurance covers a share of the buyer’s cost of a doctor’s visit or prescription drug. Tax deductions are designed to reduce the price sensitivity to engaging in beneficial behaviors such as investing in an education, purchasing equipment for a business, or charitable giving. When travel is paid for by an employer, employees might choose an airline with better amenities, not necessarily the lowest cost. When a child chooses a college to attend, he or she may be more likely to select an expensive private school if they have a scholarship or a wealthy relative willing to cover the cost of tuition. In each case, the smaller the portion of the purchase price buyers must pay themselves, the less price sensitive they are. The effect of partial or complete reimbursement on price sensitivity is called the shared-cost effect.

The shared-cost effect is a fundamental design principle built into the federal tax code. By offering tax breaks and credits for taking out a mortgage, having a child, or purchasing health care, the government is essentially willing to share the cost of engaging in behaviors that are deemed beneficial to society.

It should also be noted that sharing the cost does not always lead to greater demand. Consider how a spouse would react if, after celebrating a special occasion at a nice restaurant, their partner paid for the dinner using a discount coupon. Unless the spouse is an economist or an accountant, sharing the cost of the meal with the restaurant would probably be viewed as rather unromantic.

The value of a transaction—both economic and psychological—is also influenced by the structure of the financial terms and structure of the deal. Suppose you are about to purchase a car from a dealership where you know that haggling over prices is the norm. As a smart consumer, you have looked up the dealer’s wholesale costs to determine the “price floor,” you’ve logged onto TrueCar, an information website for car buyers, to review recent transaction prices, and you have formulated in your mind what you think would be an aggressive, low-priced offer to start the negotiations. Consider the scenario in which, upon hearing your offer, the dealer tells you that your price is far too low, counters with a higher price, and engages in several rounds of negotiations before you mutually agree on a price that is between your opening offer and the dealer’s initial price. In this instance, even though the final transaction price is higher than your opening offer, you generally feel confident that you got a good deal because the negotiations were laborious and resulted in the dealer moving down from his opening offer.

By contrast, consider the same scenario as described above, except in this instance, upon hearing your opening offer, the dealer immediately accepts your offer. In this instance, your reaction is more likely one of dread that your offer was too high—after all, why else would the dealer have accepted the deal so quickly? The transactional value in this second scenario is likely lower than in the first. And yet from an economic perspective, you are better off in the second scenario.

Transaction value suggests that buyers are motivated by more than just the “acquisition utility” associated with obtaining and using a product. They are also motivated by the “transaction utility” associated with the difference between the price paid and what the buyer considers a reasonable or fair offer for the product. Transaction utility is framed by the difference between the actual price paid and the reference price, which is the amount that the buyer would consider reasonable or fair. In the car-buying example above, the reference price in both instances is a price higher than the buyer’s opening offer—the underlying expectation for the buyer is that their opening offer would be considered unreasonably low to the dealer and that the ultimate price will be higher. Thus in the first instance, when the dealer counters with a higher price, the reference is set at a relatively high number. Any discount from that initial counter-offer is seen as a discount off of the reference and contributes to a positive transaction value. In the second scenario, however, the immediate acceptance of the initial offer implies that the dealer may have accepted an even lower offer—and signals to the buyer that he is probably overpaying relative to the implied reference price. The transactional value has now become negative, even though the transacted price is lower than in the first scenario.

The concept of a “fair price” has bedeviled marketers for centuries. In the Dark Ages merchants faced a death penalty for exceeding public norms regarding the “just price.” In the more recent communist period, those who “profiteered” by charging more than the official prices—even though the state was unable to meet demand—were regarded as criminals. Even in modern market economies, “price gougers” are criticized in the press, hassled by regulators, and boycotted by the public. After Hurricane Sandy hit America’s East Coast, the governor of New Jersey, a state particularly hard hit, issued a warning: “During emergencies, New Jersians should look out for each other, not seek to take advantage of each other,” and reminded citizens that price gouging was illegal and would warrant harsh penalties, even though economic theory would suggest that prices should naturally rise during periods of supply shortages.13

There is no precise definition of what is considered fair. It is a community-held norm that is not guided by factors such as profitability (oil companies are routinely accused of unfair price gouging even though their profits are below the U.S. industry averages), absolute value (makers of medical devices and pharmaceuticals are often accused of unfair pricing even when their products are demonstrably shown to save lives) or supply (national sports leagues will sell tickets to championship games at face value, even if there is clear excess demand).

And notions of fairness can change over time. A car dealer charging a premium that is more than the price on the manufacturer’s window sticker for a popular new model will quickly be accused of gouging, even if the adjusted price is a market-clearing price. By contrast, in the airline and hospitality industries where demand-based pricing has been practiced for several decades, consumers have become used to the idea that prices are linked to relative demand and no longer flinch when prices rise threefold or more for popular travel dates.

Markets will routinely view the pass-through of input cost increases as fair even if these cost increases pose an economic burden on the buyer. The reason is that it is generally accepted that sellers are allowed to preserve their profits in the face of rising costs. It is also generally considered fair for a seller to retain the benefits of input cost changes—there is no societal norm (at least in the United States) that would compel a seller to share his or her cost efficiencies with their customers.14

However, a sense of unfairness enters the moment that a seller exerts any market leverage to increase prices. It is one of the reasons why price increases by public utilities—which, by virtue of being sole suppliers, are always viewed with great suspicion and subject to significant regulatory review to ensure that the utility is not merely using its market power to compel customers to pay more.

The form of a price change can have significant impact on perceptions of fairness. The elimination of a discount is viewed as a fair way to raise prices in cases where demand has risen. However adding a surcharge above the regular price is viewed negatively even if the net economic impact on the buyer is the same. Passing through a price increase via a change in product size—such as when the once-standard 64-ounce container of orange juice was reduced to 59 ounces—is generally seen as fair, perhaps because these forms of price change are less noticeable.

Fairness is often framed by the “shadow of the future.” For one-time transactions, consumers tend to be more willing to accept market rate pricing. However when they anticipate future interactions with the seller, the norms of fairness are applied more rigorously. Home Depot will not raise prices of building supplies after a hurricane, while one-off entrepreneurs who make bulk purchase in other markets and truck it in to the hurricane area will charge what the market will bear. Both are acting in a profit-maximizing manner, however Home Depot’s ability to realize short-term premiums is constrained by the long-term memory of the customer that Home Depot hopes to continue serving long after the short-term jobbers have gone back home.15 And yet consumers are willing to do business with both sellers.

EXHIBIT 3-4 Distribution of Value Across the Organization

The buying process frequently involves more people than just the customer since others participate by providing information, facilitating search, and influencing the purchase decision. Multiple participants are, in fact, the norm for purchases of high involvement goods characterized by complex offerings and, often, higher prices. Multiple participants are also common in most business markets where purchasing is managed by professional procurement managers using sophisticated information systems and aggressive negotiation tactics. The addition of individuals to the buying process complicates the job of value communications because it forces marketers to adapt and deliver multiple messages at different points in the process.

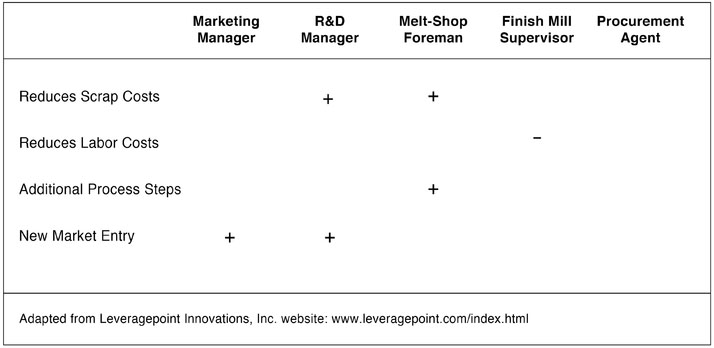

To illustrate how value communications can be adapted for multiple individuals in the buying process, we turn to the example of a chemical company attempting to sell the value of a new chemical additive for a steel mini-mill. Suppose that the chemical provided an incremental $18 per ton in monetary value for the steel producer. However, the $18 is an aggregate, company-level estimate that is not equally relevant to the different stakeholders in the customer organization (see Exhibit 3-4). For example, the marketing manager may appreciate the total value estimate, but he is impacted directly only by the fact that the chemical additive enables him to penetrate new market segments. The melt shop foreman will value the reduced scrap rate, worth $2 per ton, but he will be less pleased about the $5 per ton cost created by the additional process steps needed to incorporate the additive into the steel slurry. In the end, the finish mill supervisor may be negatively disposed toward the product because it lowers his organization’s financial performance, even though the overall value is positive. Finally, the value impact for the procurement agent is neutral because her functional area has no operational involvement with the additive; she is only involved in negotiating the price.

The need to adapt marketing communications to the product and the customer’s context makes creating effective value communications more challenging today than ever before. It is not sufficient to adapt the content of the message to the customer’s learning needs at different stages of the buying process. You must also ensure that it is delivered to the right person at the right time in the buying process. Accomplishing this task requires meaningful insight about what value is created, how that value is generated across the organization, and when the participants in the buying process are ready to receive the value messages. Our research shows that successful value communications requires close coordination between marketing and sales—a trait lacking in many of the organizations we surveyed. For those companies that make the investment to strategically communicate value, the return, in the form of more profitable pricing, can be substantial.

Although price is often more important to the seller than to the buyer, the buyer can still reject any price offer that is more than he or she is willing to pay. Firms that fail to recognize this fact and base price on their internal needs alone generally fail to attain their full profit potential. An effective price communications strategy requires a nuanced assessment of the quantifiable benefits that a customer can realize from the transaction, as well as a careful understanding of the psychological factors that might influence a customer’s decision. For most products, an economic value analysis does not fully capture the role of price in the individual decision-making. Most customers do not approximate the image of a fully informed “economic individual,” who always seeks the best value in the market regardless of the effort required. Therefore a pricing professional’s analysis must go beyond the economic value to an understanding of how the buyer’s understanding of value—and their willingness-to-pay—can be shaped and influenced through the effective leveraging of the psychological aspects of pricing described in this chapter.

1. Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1890.

2. John Hogan, “Building a Leading Pricing Capability: Where Does Your Company Stack Up?” Deloitte, 2014. Accessed at www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/strategy/us-consulting-building-a-leading-pricing-capability.pdf.

3. Charles L. Baum and William F. Ford, “The Wage Effects of Obesity: A Longitudinal Study,” Health Economics, 13 (2004), pp. 885–899.

4. Steve Banker, “Kaiser Permanente and Their Journey to Transform Their Supply Chain,” Forbes. com, October 8, 2014. Accessed at www.forbes.com/sites/stevebanker/2014/10/08/kaiser-permanente-and-their-journey-to-transform-their-supply-chain/#b1f3115109e8. Also see Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, accessed at www.dor.kaiser.org/external/dorexternal/about/index.aspx.

5. “The Importance of Misbehaving, A Conversation with Richard Thaler,” Deloitte Review, 18 (2016), pp. 56–69. Accessed at https://dupress.deloitte.com/dup-us-en/deloitte-review/issue-18/behavioral-economics-richard-thaler-interview.html.

6. J. Edward Russo, “The Value of Unit Price Information,” Journal of Marketing Research, 14 (May 1977), pp. 193–201.

7. Charlie Brown, “Too Many Executives Are Missing the Most Important Part of CRM,” Harvard Business Review, August 24, 2016.

8. “Boeing’s New 787 Dreamliner: How It Works,” Popular Mechanics, August 3, 2006. Accessed at www.popularmechanics.com/flight/a809/boeing-787.

9. Marine timekeeper H4, at Royal Museums Greenwich, Greenwich, London, UK, online image accessed at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/79142.html. Also Dava Sobel, Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (New York: Walker Books, 2007).

10. Hilke Plassman, John O’Doherty, Baba Shiv, and Antonio Rangel, “Marketing Actions Can Modulate Neural Representations of Experienced Pleasantness,” Proceedings from the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(2) (January 2008), pp. 1050–1054.

11. Baba Shiv, Ziv Carmon, and Dan Ariely, “Placebo Effects of Marketing Actions: Consumers May Get What They Pay For,” Journal of Marketing Research, XLII (November 2005), pp. 383–393.

12. Andre Gabor and Clive Granger, “Price as an Index of Quality—Report on an Inquiry,” Economica, February 1966, pp. 43–70. Also R. E. Alcaly, “Information and Food Prices,” Bell Journal of Economics, 7 (Autumn 1976), pp. 658–671.

13. David Futrelle, “Post-Sandy Price Gouging: Economically Sound, Ethically Dubious,” Time, November 2, 2012. Accessed at http://business.time.com/2012/11/02/post-sandy-price-gouging-economically-sound-ethically-dubious.

14. Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler, “Fairness and the Assumptions of Economics,” Journal of Business, 59(4), part 2 (1986).

15. “The Importance of Misbehaving, A Conversation with Richard Thaler,” pp. 56–69.