|

||

Spices, more than any other food commodity, have helped shape our modern world. In the fifteenth century, Europe awoke to the spices of Africa and Asia. These spices motivated nations to send explorers across vast oceans in search of new sources and new trade routes. By the sixteenth century countries were competing for control over those resources and routes. It catalysed both the making and the breaking of cultures.

In 1667, the Dutch negotiated a trade with the British: the island of Manhattan in exchange for an Indonesian island 1/30th the size – Run (or Rhun). While Manhattan, located at the mouth of the Hudson River, lay at the door to the fur trade, Run had an even more lucrative resource: nutmeg.

If it weren’t for the small evergreen tree Myristica fragrans, the 3km2 (about 741-acre) island of Run, and the other nine volcanic Banda Islands, would probably have been ignored by Europeans. The species is thought to have evolved on these and other islands in the Moluccas, and at the time was found only there. The trees produce up to 20,000 small yellow pear-shaped fruits each season. Though the fruit is edible, it is the pip at its heart that is of real interest – this is nutmeg. Woven around the dark nutmeg seed, in a manner reminiscent of a 1970s macramé plant hanger, is a red fleshy covering known as the aril. It’s a plant’s enticement to animals to eat the seed and help it disperse its progeny. Another well-known aril is the edible flesh of the lychee. The aril surrounding nutmeg is ground into another spice – mace. Two expensive spices with culinary value, hallucinogenic effects and medicinal uses, from a single rare plant found only on a small group of remote Indonesian islands – no wonder battles were fought.

After the British left Banda, the Dutch managed to maintain a nutmeg monopoly for 100 years. It was a French horticulturalist who would eventually bring it to an end. Pierre Poivre (a name so perfect for a chapter on spices that one might think we made it up) managed to smuggle out some nutmeg trees, which he brought back to Mauritius (then the Isle de France) where he was administrator. He planted them in the botanical garden he was building and, with a few flicks of a spade, ended the Dutch nutmeg monopoly.

While nutmeg may have been one of the rarest spices, it was the price of pepper that reflected the state of the economy for centuries. Black pepper is the dried fruit of the Piper nigrum vines of southern India. Pepper made its way out of India thousands of years ago, however, as evidenced by its presence in the nostrils of a 3,200-year-old Egyptian mummy. Pepper became the most widespread seasoning of the Roman Empire; it was transported via secure trade routes from India, up the Red Sea and the Nile River to Alexandria, where it was then shipped to Italy and Rome. Italy maintained a monopoly on the black pepper trade during the Middle Ages, from the fifth to the fifteenth century.

Pepper was of such value that it was often used as currency or collateral, and was sometimes referred to as black gold. Hints of its value linger even in today’s Dutch language – peperduur, which translates as ‘pepper expensive’, is an expression for something that is very costly. After the Italian reign over the pepper trade, the Portuguese got in on the action. With the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, Portugal gained exclusive rights to half of the black pepper-producing land. Yet smugglers continued to move it through the old trade routes via Alexandria and Italy. The Dutch and English moved in and by the end of the fifteenth century black pepper was relatively common in Europe and its price began to decrease. Today, pepper remains a very large portion of the international spice trade. In 2012, the value of the pepper market was estimated at £1.08 billion (US$1.77 billion), with Vietnam exporting around 45 per cent of the world’s pepper. And so it seems fitting that we should begin our sordid story of spice-swindling with pepper.

Pepper is not all it’s cracked up to be

The UK Guild of Pepperers – Gilda Piperarorium – dates back to the twelfth century (circa 1180). Pepper merchants traded in precious black pepper, but also dealt in sugar, dried fruits and alum. This was perhaps the most important of the food guilds as it was the pepperers who were granted the responsibility of holding the king’s weights and measures.

In the fourteenth century the pepperers and spicers joined forces and became the Worshipful Company of Grocers. It was then that this livery company was granted the office of garbling. The word originates from the Arabic garbala, which means to sift, and this is exactly what they did. Using a set of sieves, the Grocers’ Company would check and sift all the spices that landed at the London docks looking for impurities such as gravel, leaves and twigs. They used their knowledge of spices to determine the purity of the product. Every spice was checked by a garbler before it could be sold; it was a compulsory and costly venture and the Grocers’ Company had a monopoly on it.

And so life continued for several centuries until a series of events in the seventeenth century triggered the decline of power for the grocer-garblers. The East India Company sought exemption from garbling, and though it wasn’t granted, it was the first sign that power was shifting from the guilds to big business. Then the pharmacists, who until then had been part of the Grocers’ Company, separated into the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries in 1617. Drugs and oils were being rampantly adulterated and detection of such fraud required chemists rather than garblers, hence their decision to branch off. With the decline of the guilds’ power, new opportunities opened up for the adulteration of spices. By the nineteenth century it was the grocers and merchants themselves who had become the swindlers, earning a reputation for corruption and fraud.

The adulteration of pepper was well known in the early nineteenth century, but chemist Frederick Accum quantified the extent of it. Using only a glass of water, Accum discovered that approximately 16 per cent of pepper sold in London at the time was counterfeit. The artificial peppercorns were made by combining the residue of linseed (after it had been pressed for its oil), common clay and a portion of cayenne pepper. This concoction was then pressed through a sieve and rolled in a cask to achieve the appropriate peppercorn size, shape and appearance. Accum simply tossed the peppercorns into a bowl of water and those that were not pure would disintegrate in the water. In Accum’s time, anyone discovered making or selling adulterated pepper was fined £100 (US$157), which is the modern-day equivalent of about £10,000 (US$15,700).

Less effort was required to adulterate ground pepper. Small amounts of genuinely ground pepper were bulked out with the floor sweepings from the pepper warehouses, known as pepper dust, along with some cayenne. Sometimes an even more inferior product to pepper dust was added, which was known as the ‘dirt of pepper dust’. This was no doubt more dirt and dust than pepper.

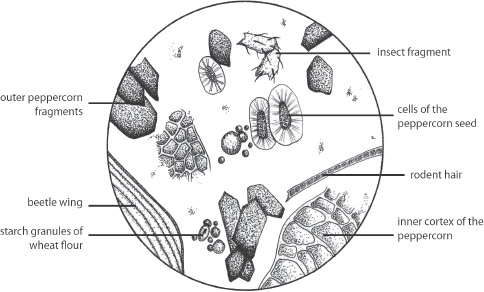

It was the physician Arthur Hill Hassall (we first met him in Chapter 2), wielding his microscope, who opened Londoners’ eyes to all that could be added to ground pepper. Renowned first for revealing the creatures inhabiting London’s water supply in 1850, Hassall turned his lens on food and was dismayed at what he found. It was Hassall who first identified the mite in brown sugar that caused grocer’s itch. The microscope was a new tool in the forensics toolkit.

Hassall studied the genuine form of pepper, cell layer by cell layer. With a keen understanding of what the real product looked like, he quickly set to work identifying the fragments that were of non-pepper origin in the samples of ground pepper that he collected. In all, he identified linseed, mustard seed, wheat flour, pea flour and ground rice amid the pepper fragments.

These days dried papaya seed is the most common adulterant in peppercorns. They are cheap, only a fraction smaller than the real thing and easily available. Just as with Accum’s detection of counterfeit peppercorns, only a glass of alcohol is required to tell the papaya seeds apart, because the papaya seeds float while true peppercorns sink. This isn’t a foolproof method, however, as immature pepper seeds can also float.

Another long-used method of adulterating peppercorns is to coat them with paraffin oil and burnt diesel oil. The coating adds weight to the peppercorns, helps preserve them from fungal infection and also provides them with a black polished shine. In 2014, 18 tonnes of pepper coated in these potentially carcinogenic oils was seized in a single raid of a warehouse in Chennai, India. It was worth about £105,000 (US$165,000). Consumers should be able to identify this pepper easily as it has a distinct oil or kerosene smell and is darker and more polished than the real thing. Yet the Consumer Association of India stated in response to the raid that consumers don’t take the time to check their spices. If people are failing to catch adulteration that is visibly detectable in a whole spice, what hope is there of finding it once these spices are ground?

Papaya seeds make their way into ground pepper too, but it’s difficult to know whether they were added by the grinders or the wholesalers of the peppercorns. Millet and buckwheat flour have also been used to add weight to ground pepper. Though the blatant addition of dirt of pepper dust from Accum’s day may be ended, there are still guidelines as to how much filth can be included in pepper before it is considered an adulterant. The FDA states that pepper can contain no more than 1 per cent of insect-infested and/or mouldy pieces by weight. Nor can it contain more than an average of one milligram (0.03oz) of mammalian excreta per half kilo (per pound). You may also be relieved to learn that the FDA recommends legal action if the average number of insect fragments per 50 grams (1.7oz) of pepper exceeds 474, or if the average number of rodent hairs per 50 grams (1.7oz) exceeds one. Given the nature of spice harvest and storage, it isn’t terribly surprising that a few insects and rodent hairs find their way into the product. But this is surely a case of accidental contamination – poor hygiene practices at worst. It is the intentional adulterants that are far more worrisome, no matter how unappealing mammal excrement in your pepper may seem.

Figure 7.1. The fragments in a ground pepper sample that Hassall may have spied under his microscope, complete with rodent hairs, beetle bits and wheat flour adulterant.

Spent spices, Sudan Red and other spice swindles

Pepper is not by any means alone in its susceptibility to fraud. Indeed, adulterating spices is a relatively straightforward process, particularly when you compare it with making a fake egg, mixing bogus milk or fashioning false mutton. It is a ground product in which foreign bodies can easily be masked. There are economic incentives, as spices are relatively expensive, and they are grown in some of the most impoverished countries in the world by subsistence farmers. There are many opportunities for substitutions between the farmer and the spice rack. The scales are definitely in favour of the fraudster.

What makes consumers more vulnerable to fraud is that many of us are reasonably ignorant of the properties of these exotic plant parts – how they should look and smell and behave as they infuse into our cooking. Such ignorance may have us choosing the paprika that has had its colour bolstered with carcinogenic dyes over the pure product. Our perceptions of purity can even lead us astray with plants more familiar to most of us. Dark green dried oregano, for example, is more visually appealing to consumers. Yet this is often an indication that dried leaves from other plant species, such as Cistus incanus (rockroses grown in the Mediterranean region), have been added to the mixture. The adulterated product is more tempting than the more pallid, yet genuine, product.

The list of adulterants in spices is long. We have highlighted the most interesting ones below, but should you wish to see a more extensive list, we refer you to the USP Food Fraud Database, which is searchable online.

Cayenne

This is a powdered mix of the ground seeds and peppers from different Capsicum species, but mostly Capsicum annuum. This spice has been adulterated with ground rice, mustard seed husk, sawdust, brick dust, salt and turmeric. To cover the addition of these adulterants, the mixture is coloured with red lead (lead (II, IV) oxide), which is used in manufacturing lead batteries and rust-proof primer paints. Chronic exposure to red lead may cause lead poisoning as well as other health implications.

In both whole and powdered form, chillies have had adulterants added to increase their weight or make them appear to be a superior product. Brick powder, sand and dirt have all been used to add weight to chillies. Malachite green – the carcinogenic antifungal that we mentioned associated with fish farms and will mention again below in relation to coriander – has been used to make green chillies appear more vibrant. Sudan dyes, which are red dyes used to colour oils, waxes, shoe and floor polishes, have been used in chilli powder. They are not legal for use in food in the EU owing to their potential carcinogenic properties, allergenic activity and mutation-inducing effects. In 2005, more than 350 food products were removed from UK shelves because Worcestershire sauce used in their production contained chilli powder that had been adulterated with Sudan I.

Cinnamon

This spice is obtained from the inner bark of the tree Cinnamomum verum. The inner bark from other species within the same genus, namely Cinnamomum cassia, is referred to as cassia or Chinese cinnamon and is often sold as cinnamon. Sri Lanka is the world’s biggest producer of cinnamon. The powdered version of this aromatic wonder has been adulterated with coffee husks, sago, wheat flour, potato flour and arrowroot powder. Cinnamon has also had the essential oils that impart its discernable smell and taste removed and then it has been re-dried and sold deceivingly as the intact product. Hassall was the first to be able to detect such tampering as the starch granules in the cinnamon become distorted and irregular when it has been boiled in order to remove these oils.

Coriander

This is the ground seeds from the herb of the same name, although the leaves are referred to as cilantro in some countries. Ground coriander has had rice husk, wood fibre and salt added to increase its weight. The most frequently reported adulterant, however, is cow dung. There are two versions of cow dung – one being organic and produced from the business end of a cow, and the other being synthetic with significant potential to harm human health. Dried cow dung, shaped into cow cakes, is a popular biofuel in India, but it can also be ground up and used as a fertiliser, cleaner, polisher, tooth polish and skin tonic. It even plays an important role in the preparation of Ayurvedic medicines and deity worship. In fact, its many uses have led to a supply shortage and this has triggered the development of synthetic dung powders, namely Auramine-O and malachite green. Both of these chemicals are toxic, particularly Auramine-O, which causes multiple organ failure if inhaled or ingested. Despite being illegal to sell, these chemicals remain relatively accessible and Auramine-O has emerged as a common drug of choice for suicide in India. There appears to be no distinguishing the genuine product from the synthetic – both are referred to as cow dung powder, including when they are named as an adulterant in spices. While a little dried cow dung powder in your coriander may seem somewhat unpalatable, it is a far better option than its synthetic alternative.

Cumin

This foundation for any good curry is the seed of Cuminum cyminum, which belongs to the same family of plants as caraway, celery, carrots, parsley and parsnips. India is the world’s biggest producer and consumer of cumin. It isn’t known as an expensive spice, but low yields inflated prices in early 2015; hot weather delayed planting and farmers shifted to other crops after prices dropped in 2014. Probably due to this short supply and higher value, cumin was at the centre of a food fraud scandal far more dangerous than Horsegate.

In late 2014 and early 2015, a number of ground cumin products in the US and Canada were recalled as undeclared peanut protein was detected in the mix. In response, the UK started testing cumin products and the FSA found undeclared almond protein. Hundreds of products containing the spice – from fajita mixes to falafels – were recalled as a result of the adulteration. Peanut shells and almond husks cost nothing, and when ground up they can be mixed in with ground cumin to bulk it up. Yet this creative cost-saving strategy can be lethal to those with nut allergies as the husks and shells often have remnants of nut attached. US resident Jillian Neal is deathly allergic to peanut products. Luckily a fast response from her family and medical professionals in November 2014 saved her after she ate chilli made with a mix containing the contaminated cumin. While warnings were issued advising allergy sufferers to avoid cumin products, the spice is often not declared on the label as it is used in such small quantities and can be considered a trade secret. But it is not just the ground version of this product that has been involved in fraud. Grass seed coloured with charcoal dust has been sold as whole cumin. Needless to say, if the cumin leaves your hands black after you touch it, you’ve been duped.

Ginger

The rhizomes of Zinziber officinale are used fresh, candied, dried or powdered. When Hassall looked at the ground product under his microscope in the nineteenth century he found two-thirds of the samples he examined were adulterated with one or more of the following products: wheat flour, cayenne pepper, potato starch, sago, turmeric, mustard husk and ground rice. And these adulterants formed the majority of the product.

Nutmeg

There have been no reported cases of people trying to substitute some other nut or seed for whole nutmeg; it seems unlikely people could be so easily fooled. However, much like with cinnamon, there were historical cases of the volatile oils of the nutmeg being extracted through distillation before selling the whole nutmegs. These nutmegs would feel light, dry and brittle in comparison with an unaltered nutmeg. Ground nutmeg has had coffee husks added to increase its weight.

Saffron

Known as the most expensive spice in the world, and rightly so, saffron is the stigmas from the domesticated flower Crocus sativus. The flowers are harvested by hand and it takes nearly 30 hours of labour to harvest the 100,000 stigmas needed to make up a kilogram of saffron, which is worth an average of £6,500 (nearly US$10,000). The world’s largest producer of saffron is Iran. Saffron threads can be bulked up by including wasted bits from the saffron flowers and weight can be added by infusing the saffron with syrups, glycerine, oils, gypsum, borax, starch and other distasteful products. There is an extensive list of items that have been dyed to mimic the vibrant crimson stigmas of the real thing, including parts of other flowers, such as marigolds, carnations, poppies and safflower. Somewhat more daringly, people have disguised beet fibre, capsicum, corn silk, grass, onion and silk fibres as saffron; they have even fashioned threads from gelatin and the fibres of dried animal meats.

The list of dyes used include quinoline yellow, which is a permitted food additive in Europe (E104) and Australia, but is not permitted in food in Canada and the US; ponceau 4R, a synthetic colourant that has been approved as a food colouring in Europe (E124), Asia and Australia, but not in the US or Canada; tartrazine (E102); and sunset yellow (E110). All of these colourants have been linked to hyperactivity in children. More alarmingly, the following dyes, which are considered toxic and/or carcinogenic, have been used to colour fake saffron: methyl orange, which has mutagenic properties sufficient to warrant avoiding direct contact with the substance; naphthol yellow; and red 2G (E128), which Europe banned owing to health concerns in 2007 and which has also been banned in Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, Norway and the US.

Salt

Salt has reportedly been adulterated with white powdered stone and chalk. Chalk can easily be identified by stirring the suspicious salt into a glass of water. If chalk is present, it will turn the water white. In 2012, Polish health authorities ordered the recall of 230,000kg (500,000lb) of food – mainly pickles, sauerkraut and bread – that was suspected of containing industrial road salt rather than table salt. Agencies tested the salt intended for de-icing roads for dioxins and heavy metals and stated that it was not harmful to human health, but they recalled the food anyway as a precaution. Several years earlier, China, the world’s largest salt producer, was mixed up in salt scandals when over 700 tonnes of industrial salt was found on the market. The fraudsters were packaging up industrial salt into small authentic-looking packages for the food market. Industrial salt doesn’t contain iodine as edible salt does. And the heavy metals and dioxins in the industrial version can affect mental and physical development and potentially impair reproductive function. In Shanghai, food cooked using the salt resulted in the death of a 38-year-old man and the hospitalisation of 25 others. The symptoms include nausea, headache, vomiting and a rapid heartbeat. The fraudsters can make about £0.07/kg (US$0.26/lb) on the scam.

Turmeric

The deep yellow turmeric powder that many of us are familiar with comes from the plant Curcuma longa, which comes from the same family as ginger. The rhizomes, which look very similar to fresh ginger, are boiled and then dried before being ground into powder for a number of uses, including cooking. This spice has a long list of adulterants associated with it, including starch, sawdust, rice flour, yellow clay and chalk powder. As with saffron and chilli, it has had a number of unpleasant dyes added to it to mask the addition of these cheap fillers. Sudan dye has been used, as well as lead chromate, which is used to colour paint and can lead to death if inhaled or swallowed. Metanil yellow is the most frequently added dye found in turmeric and, in fact, is the most common illegal food colourant encountered in India. Studies have shown that prolonged consumption of metanil yellow can have long-term health implications, including changes in the nervous system, lung function and organs as well as reductions in fertility. Turmeric is reasonably unique to the spices, however, in that it has a history of being adulterated, but is also an adulterant. It has been added to cayenne pepper, saffron and paprika to enhance their colour.

Vanilla

Vanilla beans are the fruit of orchids of the Vanilla genus, but commercial vanilla is generally derived from the species V. planifolia. The vine-like plant is found in tropical and sub-tropical regions globally, but is thought to have originated in Mexico and Central America. Vanillin is the chemical compound that is largely responsible for vanilla’s characteristic flavour and smell, but there are in fact about 200 aromatic compounds altogether that form the complex flavour of natural vanilla. Real vanilla extract is made by soaking vanilla beans in a solution containing 35 per cent ethyl alcohol in water. It is the second most expensive spice on the market and, therefore, a target for adulteration.

Tonka beans have been used as a vanilla substitute as they contain the chemical compound coumarin, which has a vanilla-like odour and taste. However, it is also moderately toxic, particularly to the liver and kidneys, and has been banned by a number of countries as a food additive. Oddly enough, the compound isn’t found in real vanilla, so it is a good target for detecting adulteration.

There is also artificial vanilla on the market, which is a much cheaper option. Most artificial vanilla is a solution of straight vanillin. It lacks the other 199 compounds in real vanilla that provide the complex flavouring, which makes it a somewhat inferior product. Most vanillin is synthesised as demand for it within the food and beverage industry as a flavouring far outweighs what could be produced by the beans alone. It used to be made from lignin – a main constituent in the cell walls of plants, which is a by-product of the pulp and paper industry. Vanillin is one of the molecules that is infused into alcohol that’s aged in oak casks, as the lignin in the oak breaks down. Most vanillin used to be produced from the waste product from pulp mills – a good use of otherwise worthless material. However, there were environmental concerns about this production method as it required using highly corrosive strong bases that then had to be neutralised later with strong acids – all with environmental implications. Most vanillin today is synthesised from the petrochemical precursor guaiacol, which is a naturally occurring compound that also contributes to the flavour of roasted coffee. It is synthesised for industrial use by methylation of catechol, a common building block for organic compounds. This is a more environmentally friendly method of synthesis, but it is also more expensive. Alternative methods are being explored, including a method developed by scientists at the Universiti Putra Malaysia that converts the lignin in sawdust without the need for harmful chemicals. In 2007, Japanese scientist Mayu Yamamoto won the Ig Nobel Prize for chemistry for extracting lignin from cow dung and converting it to vanillin.

Of course, in terms of food fraud, all of this artificial vanilla can be used to adulterate or replace real vanilla and sell for 200 times the price. By law, if vanilla contains no more than one ounce of synthetic vanillin per unit of vanilla extract, it must be labelled as ‘vanilla flavoured’ or ‘vanilla-vanillin flavoured’. More than that, and it has to be labelled as ‘artificial vanilla’. It is relatively easy to detect whether artificial vanilla has been added to pure vanilla to eke it out as it contains ethyl vanillin, piperonal and sometimes coumarin, compounds not found in pure vanilla.

All of these spices can be adulterated with spent spices – those that have passed their potency period. We all have examples of these in our cupboards, such as a kilo of turmeric from a bulk goods store that was just too good a deal to pass up. It might still look bright and yellow, but the essential oils and volatile organic compounds that gave it the aroma and flavour we so desire have long since dispersed into the atmosphere.

Spice blends, such as garam masala and curry powder, are equally prone to all of these adulterations, with the added complication that it is unclear at what stage in the processing the fraud has been committed – it could have been in the blending process, or in the actual spices that were blended.

Finding the fakes

Unlike some of the food frauds described in previous chapters, the adulterants found in spices are so diverse that an entire tool chest of analytical methods is required to reveal the fraud. While cheap oil is substituted for expensive oil or one species of fish is labelled as another, any number of things, organic or synthetic, can be ground up and mixed into a spice. To make matters even more complicated, spices are very varied in their botanical origins – they are seeds (cumin and coriander), berries (pepper), rhizomes (ginger and turmeric), roots (horseradish), bark (cinnamon), floral parts (saffron) and even floral buds (cloves). Tests that might work for a seed spice may not be appropriate for a root spice. This makes spices a particularly challenging commodity for analysis.

Accum devised some of the first chemical tests to look for adulterants in spices. The detection of red lead in cayenne, for example, could be done by shaking a sample of the spice in a sealed vial with hydrogen sulphide water; if lead was present, it would turn to a muddy black colour (though I’m not sure how many households had access to hydrogen sulphide water). Yet there are still any number of quick tests to look for adulterants that can be done with little more than what can be found in the kitchen cupboard, and wet chemistry methods (generally mixing liquids together in glass beakers) are still used by analytical labs for authenticating spices. There have been numerous efforts in India, on behalf of government agencies and media outlets, to publicise such tests. Here are some examples:

•Metanil yellow is conveniently an acid-base indicator – it changes colour within a certain pH range. Therefore, to test whether it is present in turmeric, add just a few drops of acid, such as citric acid (lemon juice) or hydrochloric acid (found in many drain cleaners). If metanil yellow is present, there should be a colour change from yellow to red that persists. Acetic acid (vinegar) isn’t a strong enough acid to cause the colour shift.

•To determine whether starch has been added to a spice, add a few drops of iodine solution. When iodine comes in contact with the amylose component of starch, a deep blue/black colour forms. If there’s no starch, the iodine will remain orange or yellow. This test won’t work for ginger or turmeric as they are both roots that naturally contain starch.

•Suspicious saffron threads can be soaked in tepid water. Both the genuine product and the dyed fakes will release a yellow colour into the water. The genuine product will continue to slowly release a pure yellow colour while the threads retain their vibrant colour. The fake threads, however, will start to lose their colour and the water will become orange with the intense colouring.

•To test for cow dung in ground coriander, sprinkle it into a glass of water. Dung will apparently float, but more importantly, once it is wetted it should smell as you would expect (not like coriander).

Though most of us don’t have easy access to a microscope, and nor would we know what to look for if we did, it is still a powerful tool in the detection of adulterants. The American Spice Trade Association (ASTA) recommends using microscopic analysis to detect grains, hulls, starch, non-declared herbs, floral waste, buckwheat, millet seed and coffee husks in a number of spices. No doubt it is also the best method of ensuring that the number of rat hairs and insect fragments are within the legal limits too.

Chromatography (commonly linked with mass spectrometry) offers a set of particularly useful tools for detecting spice adulteration. As we have mentioned previously, chromatography is good for pulling apart (and sometimes quantifying) components in a mixture, even if they are extremely similar to one another. HPLC, an analytical technique we’ve mentioned in several previous chapters, is widely used in spice authentication; once again, it is looking for chemical fingerprints of either the pure spice or the adulterant. For example, in the case of saffron, HPLC can be used to detect the three main compounds of the genuine saffron crocus: crocetin esters, which give saffron its yellow colour; picrocrocin, which gives saffron its unique flavour; and safranal, which is responsible for saffron’s aroma. Together, these three compounds determine the quality of saffron. If one of these compounds is missing, particularly picrocrocin, which is unique to the Crocus genus, then it is unlikely to be true saffron and further testing might be required. The analyst may also be looking for a specific marker of a known adulterant – metanil yellow or Sudan dyes in turmeric, chilli or curry powders, for example, will show up as an unexpected spot on the chromatogram.

Gas chromatography (GC), which uses a gas as the mobile phase, is particularly useful for analysing easily vaporised compounds, such as the volatile organic compounds that are responsible for many of the aromas and flavours associated with spices. It can therefore be used to detect whether spices are spent – that is, their essential oils removed. The GC profile of a spice will change over time as the volatile organic compounds dissipate. GC can confirm the presence of papaya seed in pepper as papaya contains the compound benzyl glucosinolate, while pepper does not.1

GC/MS is also used to detect pesticide residues in spices. This is a topic worthy of further discussion, which we will do in Chapter 9 when we discuss fruit and vegetables in more detail, particularly those labelled as organic when they are clearly not. In terms of spices, though, testing in the Pesticide Residue Research and Analysis Laboratory at Kerala Agricultural University in India in 2014 revealed that chilli powder, cardamom and cumin can all be highly contaminated with pesticide residues that are beyond the legal limits. In 50 samples of cardamom tested in 2011, 74 per cent of the samples had pesticide residues, including DDT.2 These pesticides are in the soils where the crops are grown. So, while this contamination is not intentional, it can still be considered a form of fraud as consumers are led to believe that the products they are sold have met certain safety standards, which is obviously not the case. We promise to return to this.

Spectroscopic techniques are another set of tools for authenticating spices. The basic principle behind this group of techniques is that light (usually in the near- or mid-infrared spectrum) is shone on or through the sample being analysed and the light that is reflected back is measured. Any wavelengths of light that are not reflected back or do not pass through the sample are absorbed by the sample. The chemical bonds in the sample get excited by the light radiation and will vibrate and absorb light at different wavelengths depending on the type of bond; a carbon-hydrogen bond will dance to a different radiation tune from a carbon-carbon bond. Also, carbon-hydrogen bonds in an aromatic ring, such as that found in the principal component of cinnamon, cinnamaldehyde, will absorb a different wavelength of light from the carbon-hydrogen bonds outside the ring. In other words, much like people on a nightclub dance floor, the carbon-hydrogen bonds behave differently depending on who’s closest to them.

The output of the analysis resembles the profile of a cave ceiling, with stalactites of varying lengths and widths. The shape, magnitude and absorption band of each stalactite-like peak holds a piece of information about the molecular structure of the compound being analysed. It’s a near-instantaneous molecular signature. Of course, there’s lots of noise in these data as well, so statistics, known as chemometrics, are used to sort out the irrelevant information from the useful information and to tease apart more complex data. These types of methods have proved useful in quantifying the amount of buckwheat or millet in ground black pepper as well as the adulteration of turmeric with chalk powder.

We could continue to list the various analytical techniques, but we fear that if we start throwing around terms like near-infrared hyperspectral imaging you may start to glaze over. The point is that all of these analytical methods are used to separate the compound under investigation into its various constituents. Some of these techniques have advantages over others depending on what is being investigated and the constituent that is being sought. The advantages of these methods in general are that they are fast and cheap to run and the equipment required is standard for most analytical labs. The disadvantage is that the molecular structures of some substances can be indistinguishable. Pure cinnamon and cinnamon adulterated with corn starch, for example, give nearly identical spectra and it is only after secondary processing of the data that very small differences can be seen. Furthermore, it has been shown that the molecular signatures of spices change over time. Hence the term ‘signature’ rather than ‘fingerprint’.

DNA-based methods are also used in spice authentication, particularly for identifying plant-based adulterants. However, extraction of DNA from plants is somewhat less straightforward than from animals. The protocols used to pull the genomic material from the sample not only depend on the plant being analysed but also on what part of the plant is used – seed, root, flower and so on. The methods that we have described in earlier chapters, such as barcoding and PCR, have been used to screen saffron products for non-Crocus sativus species, to separate cinnamon from cassia and other Curcuma species from turmeric, and to identify papaya in pepper. The utility of DNA-based methods will continue to increase as more primers are developed to detect the common adulterants of certain spices – dried red beet pulp in chilli powder, for example. The precision of DNA-based methods, when they work, make them appealing in terms of gathering indisputable evidence about the presence of life-threatening allergens such as nut protein in cumin and other cases of fraud.

The nutty spice incidents were a wake-up call reminding us that spices are arguably the most fraud-vulnerable commodity in our food supply. Vegetarians and vegans who only glanced at the chapters on meat and fish are as subject as omnivores to these fraudulent flavourings. No religion and no culture is immune, though some are obviously more exposed. Spices are in everything. More concerning is that they may not be listed on the label.

In January 2014, a 38-year-old English man with a serious nut allergy died after eating a takeaway curry. The owner of the curry restaurant has been charged with manslaughter by gross negligence and is standing trial as we complete this chapter. As a result, the details are not yet available, but one has to wonder whether adulteration of the spices used in the curry will be a main argument from the defence? With nut protein in cumin, it is really rather a miracle that there have not been more cases of people reacting to their takeaways.

Not only do food forensics have to try and resolve the crime, they also have to be robust enough to stand up to the trial process. Bart Ingredients is one of the spice suppliers that recalled some of their products during the nutty spice fiasco. At the time of writing this chapter, they were raising doubts and questioning the accuracy of the tests being used by the FSA to identify the nut protein. The current methodology is to use ELISA, which you may recall from the meat chapter. The test depends on an antibody to almond protein recognising and binding to any almond protein found in the sample. However, Bart Ingredients has argued that the test can give false positives for almond protein as the antibody can also bind to proteins from the spice mahaleb, which, interestingly, tastes of bitter almonds. Mahaleb comes from the tree Prunus mahaleb – a species of cherry that’s cultivated for the spicy seed at the core of the cherry stone. In small amounts, it is therefore conceivable that there has been some cross-contamination in the growing, processing or storage and transport of these two spices. If found in large amounts, however, one would have to suspect its presence is more intentional.

As of December 2014, new EU legislation was introduced that requires restaurants and takeaways in Europe to inform customers if their food may contain any of the 14 most common food allergens: celery, gluten-containing cereals, crustaceans, eggs, fish, lupin, milk, molluscs, mustard, nuts, peanuts, sesame seeds, soya and sulphur dioxide. This is no simple task if you consider that wheat, nuts, peanuts, mustard and soy have all been found as adulterants of commonly used spices! While the restaurant shouldn’t be blamed because the paprika they used was corrupted well before it came into their hands, it is unfortunately their premises that will be wrapped up in the scandal. It is on their floor that the anaphylactic reaction will occur, their diners that will be affected by the scene and it will be their name in the headlines. It is a thought that must have restaurant owners taking a thorough look at their supply chains.

The European Spice Association, Seasoning and Spice Association and ASTA – all groups that represent spice companies – have developed papers on spice adulteration in an attempt to educate their members on the issue. The task of combating fraud once spices are on the shelves and in other products seems an insurmountable task. It therefore seems as though the industry itself will have to be a leader on this front. A return to the Pepperers’ Guild, if you will, where there is pride (and a premium) in providing a genuine product.

Of all the types of food, we suspect it is spices that are most likely to be embroiled in food fraud scandals in the future. For the last five years, there has been a steady increase in the volume of EU spice imports, growing an average of 4.1 per cent per year. The value of these imports, on the other hand, has skyrocketed with an average price increase of 8.3 per cent per year.

The obvious economic incentives aside, spices are also most prone to the effects of global climate change. The spice trade is largely dependent on the production from developing countries; they provide 57 per cent of total EU imports. These countries are at the forefront of climate change and are already experiencing changing rainfall patterns. These changes are resulting in severe and prolonged droughts in some regions and frequent brutal flooding in others. The eastern Himalayas have seen a steady decline in one of their biggest cash crops – cardamom. Warmer and drier winters have allowed a fungal blight to flourish, killing crops and forcing farmers to turn to less valuable crops.3 Low yields of certain crops will need to raise the fraud alert flags.

Climate change may also provide new opportunities to grow spices where they have not been grown traditionally. The UK, with its insatiable appetite for curry, has already started to consider that land that is currently marginal might become ideal for growing some of the spices currently imported. Capsicum and chilli pepper production has steadily increased in the US as well as in parts of the EU. However, there needs to be sufficient agricultural land or enough financial incentive to switch traditional crops over to these new and potentially risky ventures. There needs to be sufficient demand and plenty of cheap labour available, as many of these crops are labour-intensive, particularly at harvest. The official forecast from the industry is that the demand for spices will continue to outpace the supply.

Spices also present a challenge to consumers in terms of reducing our potential exposure to fraud. Unlike fruit, vegetables and meat, it is nearly impossible to buy locally or even to reduce the number of steps between farm and fork. The best we can hope to do is buy our spices whole wherever possible and spend £10 to £20 (US$15 to $30) on a spice grinder. It is harder to fake a whole spice and they have a longer shelf life in their whole form.

In addition to buying whole spices, we can switch our seasonings to those that can be more locally sourced. In the UK, this would mean fresh herbs over ground spices. This is a big ask and it would mean the end of curry night, but it might lead to new culinary adventures too. There are so many considerations when it comes to the food we eat – health factors, ethical implications, environmental footprint, cost ... and, somewhere in there, taste! Spices are one more thing (if there’s room) to add to our consciousness about food. Just as many people have decided to reduce the amount of meat they eat for environmental or health reasons, perhaps we could consider reducing our dependence on imported spices – even for one meal a week. Who knows, there may even be some beneficial side effects, such as lowering our salt intake, a change our doctors would applaud.