THE LOSHEIM GAP-SCHNEE EIFEL-SCHOENBERG ST VITH-VIELSALM

STARTING POINT: LOSHEIM, GERMANY ON PRUMER STRASSE 265, ABOUT 24 KILOMETRES EAST/SOUTHEAST OF MALMEDY, BELGIUM. PARK NEAR THE CHURCH IN VILLAGE CENTRE.

Losheim gives its name to the Losheim Gap, a broad valley that cuts through the Schnee Eifel Ridge, i.e. the high ground, just east of the Belgian – German border. The Losheim Gap constituted the boundary between the United States V and VIII Corps as well as an important route for the planned German attack into eastern Belgium. According to Dr. Hugh M. Cole ‘The Losheim Gap is no pleasant pastoral valley but is cluttered by abrupt hills, some bare, others covered by fir trees and thick undergrowth. Most of the little villages here are found in the draws and potholes which further scoop out the main valley’.

A reinforced Cavalry Squadron of Colonel Mark Devine’s 14th Cavalry Group occupied the Losheim Gap prior to the German attack. To the left of the Cavalry Group ran the corps’ boundary and the right flank of the 99th Infantry Division. The newly arrived 106th Infantry Division, commanded by Major-General Alan W. Jones, to which the cavalry were attached, occupied the central and southern sections of the heavily forested Schnee Eifel.

As you exit Losheim, heading south, running parallel to 265 and to your left is a long stretch of ‘Dragon Teeth anti-tank obstacles of the once vaunted Siegfried Line, often referred to as the ‘Westwall’.

Continue driving south on 265 and in village of Kehr, about 100 metres past the church, take the minor road to the right marked ‘Ausser Anlieger’ (Level with Garage Scholzen). Continue downhill until you reach the village of Krewinkel and upon passing the new church on your left, turn left and drive around the steeple of the old church to your front right. Keep driving until you can turn right again and stop with the old church to your right rear.

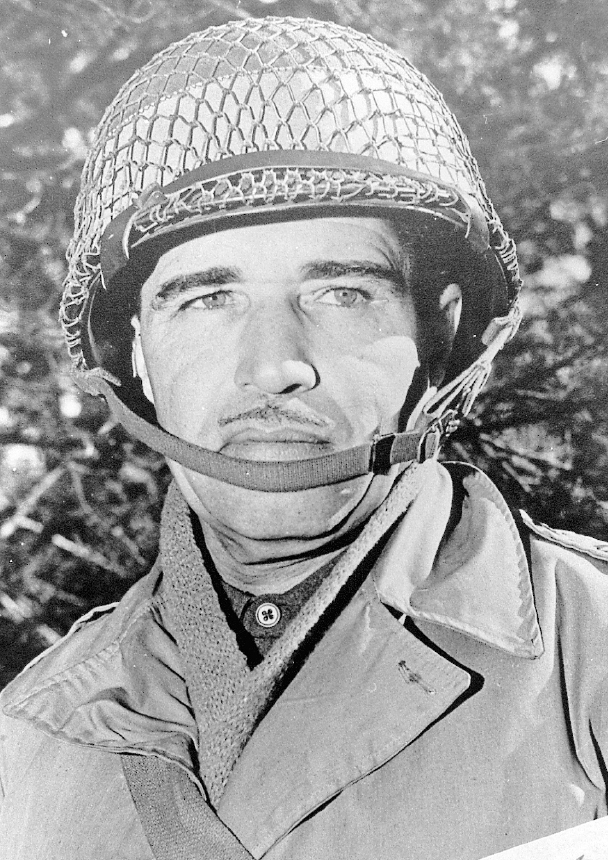

Major General Alan W. Jones commanding general 106th Infantry Division. (Author’s collection courtesy Mrs Alan W Jones).

Krewinkel typifies the small rural villages of the Losheim Gap. The village was occupied by the 2nd platoon of Troop C, 18th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron and a Reconnaissance Platoon of Company A, 820th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Positioned here in the centre of the village, the defenders occupied the various buildings from which excellent observation and good fields of fire covered all approaches to Krewinkel from the east. In the early morning dark under the beams of searchlights reflected off low-hanging clouds to create ‘artificial moonlight’, an assault company of the German’s 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division boldly approached the village in columns of four. The troopers held their fire until the enemy infantry were within twenty yards of the outer strands of defensive wire – then cut loose. The column quickly disintegrated, but the Germans quickly resumed the attack in more open order and were shortly in the village streets. At one point, half the village was in German hands, but eventually the defenders got the upper hand and the enemy withdrew.

Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) machine gun team. They were used as ordinary infantry after they suffered heavy casualties in the invasion of Crete in May 1941.

One of the last to leave shouted in English ‘Take a ten minute break, we’ll be back!’ An exasperated trooper yelled out in reply ‘—— you! We’ll still be here’. At 06.45, an attack from the bald hill (at the time of writing forested) to your left, was met and stopped by heavy fire from the light machine-guns positioned on the northern edge of town. A most welcome re-supply of much needed ammunition arrived on the scene when Troop C’s executive officer arrived in a halftrack, only to be killed on his way back to the nearby village of Afst.

By the time the Germans made their next assault on the village the defenders were well prepared. A few enemy paratroopers made it into the eastern edge of Krewinkel but made no further progress. By late morning, group headquarters informed the cavalrymen in front of Manderfeld that they should withdraw to the ridge line marked by that village and if necessary, to a second ridge two miles behind Manderfeld. The defenders of Afst and Krewinkel made a perilous escape under fire from Germans to either side of the road while other cavalrymen elsewhere were unable to withdraw.

Continue straight-ahead then take the first right returning in direction of Kehr. (At the time of writing after you pass the new church, a barn and farmhouse on the left still bear evidence of gunfire on one gable end. This is the building marked ‘Arty OP’ at the bottom right hand corner of the sketch). In Kehr, turn right onto 265 and continue in the direction of Prum. At Mooshaus turn right in the direction of ‘Roth bei Prum 1km’. Pause briefly prior to reaching Roth.

The house marked ‘ARTY OP’ on sketch.

The forested high ground running parallel to the left side of the road is the central section of the Schnee Eifel along which all three battalions of the 422nd Infantry of the 106th Infantry Division were positioned. The regimental commander, Colonel George Descheneaux, located his regimental command post in the village of Schlausenbach, about midway between the Schnee Eifel and the road you are travelling on. This road leads from Roth, via Auw to connect with the Bleialf-Schönberg road just northwest of Bleialf. In Auw, a minor road branches west to Andler then follows the Our River to Schönberg. If the Germans captured either road this would enable them to envelop the Schnee Eifel defenders. Colonel Charles C. Cavender’s 423rd Infantry had one battalion in the Westwall atop the Schnee Eifel, another bending around the southern nose of the Schnee Eifel and a third, its remaining battalion, back to the west acting as division reserve near Born, north of St. Vith. The regimental command post was in Buchet, a small village on the West Side of the Schnee Eifel and north of the road leading into Bleialf from the east. This road circumvents the south end of the Schnee Eifel then passes through Bleialf toward Schönberg thus permitting envelopment from the south.

Continue into Roth and head for the village church in the centre.

Captain Stanley E. Porche’ and a few men of Troop A, 18th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, supported by two towed tank destroyers, found themselves under attack here in Roth by elements of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division. The attack came along the road from Mooshaus and initially, the cavalrymen held their ground, but the attacking Volksgrenadiers persisted in their attempts to capture the village and the road via Auw to the Our River. About 11.00, Captain Porché radioed Troop A headquarters in nearby Kobsched to inform them that the troops of the 106th Infantry Division farther south were moving back and that the Roth garrison would attempt withdrawal and that Kobscheid should do likewise. Unfortunately, the German grip on Roth proved too strong and later on the afternoon of the 16th the cavalrymen surrendered.

Return to 265 turning right and climbing the reverse slope of the Schnee Eifel. Upon reaching the crest turn right, following the sign for ‘Brandscheid’. As you travel along this road keep an eye open on bends for the remains of concrete bunkers of the Westwall. At the third such bend, (just prior to reaching firebreaks to both left and right) to your left are some of the more obvious remains of such a bunker. Make a pause here.

Volkesgrenadiers advancing during the Battle of the Bulge. (Roland Gaul)

In the early morning hours of 16 December 1944, here, high in the centre of the Schnee Eifel, the 422nd Infantry missed the first rude shock of the pre-dawn attack. It was not part of the German attack plan to engage the 422nd by frontal assault. The enemy penetration just north of Roth during the hours of darkness, quickly brought the assault troops of the 294th Regiment of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division down the road to Auw and onto the American Regiment’s flank and rear. At daylight, small groups of Germans began pressure against the forward battalions of the 422nd in an attempt to fix American attention to their front. Company L, 422nd rushed to the defence of the regimental command post located in a Schlausenbach ‘Gasthaus’.

Resume your journey travelling the length of the 422nd Infantry front line as well as that of a battalion of the 423rd. Continue driving for ten kilometres until you reach the junction with the Prum – Bleialf road where you turn right in the direction of Bleialf. Stop prior to entering the village.

Intense artillery fire laid on the 423rd Infantry at the start of the attack had disrupted telephone communications, but the radio net functioned well. By 06.00, Colonel Cavender had word that his anti-tank company was under small arms attack in Bleialf, the key to the southern route around the Schnee Eifel. When shock troops of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division’s 293rd Regiment struck the 423rd Regimental Anti-tank Company in Bleialf, one group filtered into the village. Another, marching along the railroad, cut between Bleialf and Troop B of the 18th Cavalry Squadron, blocking the latter and destroying the right platoon of Anti-tank Company.

Continue into Bleialf and in the village follow the sign ‘Leidenborn’ to the southern edge of Bleialf. Passing roads to Pronsfeld and Urb respectively. At the ‘Zum Bahnhof’ guesthouse pull over on the left side of the road.

To your front left stands a modern pre-fabricated factory building behind which are the remains of the wartime railroad which at the time had a station (to your front left). Troop B of the 18th Cavalry under Captain Robert G. Fossland was attached to the 423rd Infantry and southwest of the rest of the squadron.

At 06.00 on 16 December 1944, artillery of every calibre and in heavy concentration fell on the forward areas. From their position in Winterscheid, the men of the troop headquarters could see it falling up and down the front line positions. A few rounds fell in the town of Winterscheid, but it was mostly of harassing nature and Captain Fossland made the observation that it did not seem to be concentrated on places, which the enemy would suspect of having American troops in position.

Following the barrage, which seemed to last about an hour, an armoured car patrol of three men, volunteers, attempted to contact the forward platoon positions and supply them with SCR 536 radios. All wire communications with these platoons had been cut, and as yet, the platoons had not opened the emergency SCR 508 radio channels that they held open for such an emergency.

The three volunteers bumped into an enemy patrol of about twelve men in the vicinity of the northern outlet of the Bleialf railroad tunnel and tangled with this group in a brisk fire fight. The Germans took off, but the patrol was skeptical of its chances of getting the radios through in view of indications that there were other German troops in the area.

Daylight came at about 07.15 and with it came the first strong pressure from enemy rifle troops. At about the same time the 508 radio channels to the platoon positions overcame enemy jamming and the Winterscheid headquarters was able to determine the progress and development of the fight to its front. The first attacks to be felt came in the vicinity of the 3rd Platoon, five hundred metres Northeast of Grosslangenfeld, a town one thousand metres south of Winterscheid held by soldiers of the 106th Infantry Division’s Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop.

The next pressure, and seemingly more intense, came against the 1st and 2nd Platoons here in position near the Bleialf railroad tunnel. Defensive artillery and the cavalrymen’s many automatic weapons took a heavy toll on the attacking Germans. The defenders held their position securely, although they were running low on ammunition. During a brief lull in the fighting, Sergeant Wade Bankston and four of his men managed to drive an armoured car from Winterscheid to Bleialf bringing with them some much needed ammunition. Again the Germans attacked and this time no further ammunition reached the beleaguered Americans from troop headquarters in Winterscheid. Captain Fossland called Colonel Cavender to inform him of the situation in Bleialf and Cavender gave him permission to withdraw his three platoons to Winterscheid.

Return in the direction of the centre of Bleialf turning left at the sign for ‘Urb’ and stopping in Winterscheid.

The Troop B withdrawal to Winterscheid was effected under cover of mobile support provided by three armoured cars under the command of 1st Lieutenant Richard Winkler. The withdrawal was made with no additional casualties and the 2nd and 3rd Platoons brought out all their equipment.

Here at Winterscheid, by darkness, the cavalrymen established an all-round defence of the village. Throughout the night of 16/17 December, intermittent rocket and artillery fire struck the village as Captain Fossland’s men struggled to establish a new main line resistance. The 423rd Infantry informed Troop B of the presence of friendly engineers in Bleialf but patrols sent to establish contact failed to find any such friendly troops.

Renewed attempts to establish contact with friendly troops to the north failed on the morning of the 17th and at 10.00 the 423rd Infantry ordered Troop B to withdraw to Mützenich just west of the Bleialf – Schönberg road to set up flank security for the regiment.

Return to Bleialf church and turn left in the direction of Schönberg. Stop at the road junction about one kilometre north of Bleialf.

The road to your right leads Northeast from here via Auw and Roth to the Losheim Gap. Back to your right rear the high-forested ground were the Schnee Eifel positions of the 422nd and 423rd Infantry. From here it is clear that by capturing both ends of this road, the Germans would be in position to spring shut the jaws of a pincer movement west of the Schnee Eifel defenders.

Prior to the battle, American vehicles passing this junction were quite often subjected to incoming German artillery fire and therefore nicknamed this junction ‘88 Corner’. In order to permit the free movement of vehicles between Schönberg and Bleialf, men of the 168th Engineer Combat Battalion built a ‘corduroy’ road bypassing ‘88 Corner’ and known as ‘The Engineer Cut-Off’.

Continue in the direction of Schönberg and upon reaching the second sharp bend in the road (about 1,200 metres) a dirt track joins you from the right. At the time of writing, it is marked ‘Anlieger Frei’ and bears a sign (Land und Forst Wirtsch Verkehr Frei) limiting access to vehicles less than 3.5 tons. Make a brief stop here.

Insignia of the US 106th Infantry Division – the Golden Lions

This track to your right was nicknamed ‘The Engineer Cut-Off’. Engineers of the 168th Engineer Combat Battalion improved this trail so vehicles could avoid coming under fire. On the evening of 16/17 December, Major General Alan W. Jones of the 106th Infantry Division ordered his division reserve, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph F. Puett’s 2nd Battalion, 423rd Infantry forward from St. Vith to help the 589th and 592nd Field Artillery Battalions displace further west.

Colonel Puett ordered 2nd Lieutenant Oliver B. Patton to take a jeep with three men and drive from Schönberg via the corduroy road to locate the artillery battalions, then return to act as guides for the rest of the battalion to move forward.

As Lieutenant Patton, his driver and the other two men negotiated the log road in the inky dark, suddenly they heard the unmistakable sound of a tracked vehicle and shouts in German. Running their jeep into the roadside they sought refuge in the dense undergrowth as several German assault guns and infantrymen passed by.

The danger gone, Lieutenant Patton’s party got their jeep back onto the road and resumed their journey. Upon locating the artillery men and taking one of them as a guide for their return with the rest of the battalion, they drove back to Schönberg without incident. In his book, A Time For Trumpets, Charles MacDonald presumed: ‘The German vehicles and soldiers Patton and his men encountered on the Engineer Cut-Off apparently constituted a patrol and may have subsequently established a roadblock at 88 Corner’.

Continue downhill a short distance, until you reach Ihrenbruck where a minor road to the left leads to Mützenich. Follow this road to the village (about 1km).

Here, at Mützenich, Captain Fossland’s Troop B, 18th Cavalry, joined forces with four officers, forty-three enlisted men and fourteen vehicles of the 106th Infantry Division’s Reconnaissance Troop and six men of the 423rd Infantry. They promptly established positions around the village and prepared to defend it. Cavalrymen often referred to such a position as a ‘sugar bowl’. It lay in the middle of a three-sided depression, commanding the only approach from the east and as such, constituted a veritable ‘sugar bowl’ for the attacking enemy who could take advantage of the high ground and covered approaches that stood on three sides of the position.

Shortly before 14.00, the cavalrymen spotted their first Germans moving northwest toward Schönberg on the Bleialf- Schönberg road. At about 14.00, a German enlisted man from this column came into town from the east under a flag of truce. In fluent English, he spoke with one of Captain Fossland’s lieutenants offering the troopers the chance to surrender, they refused his offer and the German returned from whence he came.

The enemy column continued passing off to the northwest and out of range so Captain Fossland sent three armoured cars to determine the extent and power of the enemy forces on the Bleialf-Schönberg road and stated that Mützenich was no position from which to fight a delaying action. The 423rd responded by asking the cavalrymen to join them in Buchet but Fossland told them the area between them was full of German troops. He requested and was granted permission to move to the vicinity of Schönberg then start a delaying action back toward St. Vith. The 423rd Infantry told Troop B that Schönberg was reported as being in German hands but the cavalrymen nonetheless moved out. The 3rd Platoon took the lead followed by the 1st, headquarters, the 2nd and with elements of the 106th Reconnaissance Troop bringing up the rear.

As the withdrawing Americans reached this spot on the road, a jeep cut into the column between the 1st Platoon and the Headquarters group. Fossland’s men couldn’t believe their eyes, the jeep’s occupants were four or five enemy soldiers armed with Panzerschrecks and MP 40 machine pistols. Immediately, an armoured car of the 1st Platoon fired several 37mm high explosive rounds at the captured vehicle which rolled off the road into the ditch killing the passengers.

Continue in the direction of Schönberg and stop about 1,200 metres further on where you reach a major bend in the road.

The forested area off to the right is known as Lindscheid and is where the retreating troops of the 422nd and 423rd Infantry ended up surrounded prior to their surrender on 19 December 1944.

Continue downhill passing a builder’s yard named ‘Leufgen’ on the left and stopping at a small religious shrine on the right.

Arriving on the outskirts of Schönberg, which had earlier been reported as being in German hands, Captain Fossland halted his column here on the edge of town and ordered Lieutenant Elmo J. Johnston and his leading 3rd Platoon to enter town and determine the situation. Lieutenant Johnston led the platoon in his armoured car followed by two more armoured cars and trailed by the platoon’s six jeeps. They entered town and crossed the Our River bridge turning left in the direction of St. Vith. Upon doing so they spotted a column of American 6 x 6 trucks lined up on the road ahead of them and facing west toward St. Vith. At first glimpse, in the growing dusk, Lieutenant Johnston and his men believed the occupants of the trucks to be American troops but closer examination revealed them to be German. The cavalrymen initially presumed this to be a large group of prisoners awaiting transport to the rear but soon changed their minds when they saw the ‘prisoners’ were armed.

The intrepid Sergeant (later Lieutenant) Donald L. Rubendall of Troop B, 18th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron. (Author’s collection, courtesy of Donald L Rubendall).

The armoured car crewmen immediately realised what lay before them and sprang into action driving along the left side of the column and blasting the loaded trucks with canister shells at a range of five to six feet!

Enemy soldiers leapt in panic from the trucks and tried in vain to scurry to safety, as they scrambled, without weapons for cover. Lieutenant Johnson’s armoured car led the way closely followed by those of Sergeant James R. Hartstock and Sergeant Donald L. Rubendall.

Back on the hill, leading into town, Captain Fossland heard the first reports of contact and the crackle of gunfire over Lieutenant Johnston’s radio just before the Germans knocked out the lead armoured car killing Lieutenant Johnston’s driver, Bennie O. Webb and seriously wounding the Lieutenant. Sergeant Hartstock radioed to say he was stuck, and after this message, Fossland heard nothing more of those two armoured cars.

Meanwhile, Sergeant Rubendall and his crew followed in the wake of the other two, shooting at everything in sight. What Rubendall later described as a ‘Mark IV’ tank lumbered out of a side road from the right and blocked the progress of Rubendall’s vehicle. So sudden was the appearance of this enemy tank that the M-8 armoured car was within five or six feet of the tank when it screeched to a halt. Immediately, Rubendall’s gunner began firing armour-piercing shells point blank at the Mark IV setting fire to the engine compartment.

Slowly, the long 75mm cannon on the tank started to traverse toward the American armoured car. Sergeant Rubendall noticed that the enemy vehicle’s turret was open and threw a grenade at the open hatch in an attempt to get it inside. He missed but noticed that as he threw a second grenade, the turret’s traversing halted as each grenade clanged against the hull. Evidently the enemy tankers were flinching as each grenade hit the outside of their steel monster threatening to pop inside the open hatch. This helped stop traversing of the turret. The intrepid sergeant threw five or six such grenades until he ran out and in desperation grabbed the nearest thing at hand, an empty shell casing, ejected from his 37mm cannon. He hurled it blindly at the tank and as it clanged against the side of the tank Rubendall noticed that once again, the enemy gun barrel stopped its slow traversing toward his M-8 armoured car. Maintaining a steady stream of brass shell casings hurling at the enemy, he covered the actions of his crew as they bailed out and raced back to where they had left the six jeeps only to find the jeep crewmen engaged in a fire fight of their own. Only one of the jeeps made it back out of the village to rejoin Captain Fossland here on the road above town. All the other men in the column scattered and started off toward the south and west in an attempt to reach friendly lines. Rubendall, Jack Borge, Gerald Hurnee, Warren Varner and a medic from the 106th eventually made their way out and participated in the defense of St. Vith rejoining their squadron on New Year’s Day 1945.

Panzerkampfwagen MkIV. This type remained in production throughout the war and became the mainstay tank of the German Army.

After disabling their vehicles by removing or breaking critical parts, Captain Fossland and his men ‘shorted’ their radios and booby-trapped demolished equipment before splitting up into small groups and making their way out on foot.

Author’s note: Broad consensus states that the 18th Volksgrenadier Division only had assault guns and not tanks, in Schönberg that morning. Sergeant Rubendall’s description of the ‘tank’ as having an open hatch on a revolving turret would seem to indicate the presence of at least one German tank in Schönberg – German assault guns did not have revolving turrets. Despite the inability of many WW2 GIs to accurately identify enemy armoured vehicles, and their tendency to refer to all tanks as being ‘Tigers’, it is likely that an NCO in a cavalry reconnaissance unit would be able to differentiate between the two. Rubendall’s description, at a range of a few feet, leaves little doubt as to the true identification of the vehicle in question. It was a tank.

Continue into Schönberg and opposite the church at the traffic circle take the first exit in the direction of Manderfeld. Pass a car dealership on the right and take the third minor road to the right (about 1,500 metres after the ‘T’ junction). At the time of writing, this road is directly after the last house on the right (#55) and just before a bus stop sign (#216).

Upon turning right continue up the incline then stop at the first junction.

It was on the high ground to your right, between here and the Skyline Drive that the remnants of the withdrawing 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments were ultimately surrounded.

Attempts to enter Schönberg drew heavy fire from half track mounted flak and assault guns. As elements of the 1st Battalion, 422nd Infantry attempted to cross the road on the West Side of the Schnee Eifel; they came under heavy machine-gun and assault gunfire, which inflicted large numbers of casualties. Ultimately, by early afternoon on 19 December, Colonel Descheneaux and his 2nd and 3rd Battalions reached the high ground overlooking the Schönberg – Andler road. Below them (and to your left) they spotted a column of vehicles lined up bumper to bumper. No sooner did they begin walking downhill, than they came under a hail of machine-gun and assault gunfire from the Germans on the road that forced them back into the forest.

Oberst Otto Ernst Remer commander of the Führer Escort Brigade. (Author’s collection, courtesy Otto Remer).

When enemy tanks of Oberst Otto Remer’s Führer Begleit Brigade appeared to his rear, Colonel Descheneaux realised that he and his men were completely surrounded. Colonel Puett of the 2nd Battalion, 423rd Infantry, unable to contact Colonel Cavender of the 422nd decided to head for the Andler – Schönberg road only to come under friendly fire when they ran into Descheneaux’s 3rd Battalion. When this firing stopped Puett and his men joined forces with the 422nd.

By this time, the effects of three days of fighting and a severe shortage of food, water and ammunition simply added to the misery of the surrounded Americans.

Colonel Descheneaux decided that the time had come to surrender although a few men decided to try and escape. Colonel Puett’s executive officer, Major William Cody Garlow, a grandson of the famous Buffalo Bill, volunteered to meet the Germans to arrange the surrender. Nearby, Colonel Cavender had reached the same decision. As Major Garlow walked down toward the road between Schönberg and Andler, the surrounded Americans began destroying their weapons.

Men of the US 106th Infantry Division after their surrender to elements of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division.

Close to where you are stopped, Major Garlow met with the Germans and agreed the surrender terms. German Kriegsberichter camera crews made a point of filming the masses of prisoners in a field in nearby Andler as German tanks rolled by on the road, one even sporting a black teddy-bear on its gun barrel.

Lieutenant Johnston and the men of the 3rd platoon, 18th Cavalry Squadron were not the only Americans to enter Schönberg only to find the village in German hands. The executive officer of Battery A, 589th Field Artillery Battalion, 1st Lieutenant Eric Fisher Wood and the commanding officer of Battery B, Captain Arthur C. Brown both had similar encounters with the Germans in those trucks. Captain Brown eventually escaped with a small group of men and the help of a Belgian farmer named Edmond Klein in the village of Houvegnez near Stavelot. Lieutenant Wood, less fortunate, died in the forest just north of the road to St. Vith.

Proceed in the direction of St. Vith and after about 1.5 kilometres stop near the bend as you enter the village of Heuem.

As reinforcements brought in to bolster the 14th Cavalry Group defense, the men of Troop B, 32nd Cavalry were positioned in Andler astride the main German approach road to both Schönberg and St. Vith. At daybreak on 17 December, two of the troop’s reconnaissance teams, about twenty men, were suddenly engulfed by enemy tanks and infantry of the 506th Panzer Battalion, thrown in by Sixth Panzer Army to reinforce its advance toward Vielsalm. This force had detoured south of the inter-army boundary in search of a passable road. Contact was momentary and Troop B hastily withdrew to Schönberg while the enemy tanks went lumbering off to the northwest. In Schönberg, Troop B was hit again, this time by elements of the 294th Regiment, 18th Volksgrenadier Division led in person by the division commander Generalmajor Hoffmann-Schönborn. The cavalrymen headed west toward St. Vith, looking for a defile or cut which would afford an effective delaying position.

They finally reached a favourable point at this sharp bend near Heuem. Here while other troops streamed through from the east, the troop commander, Captain Franklin B. Lindsay, Jr. deployed his six armoured cars and fifteen jeep-carried machine-guns and mortars. For almost two hours Troop B repelled every attempt by the pursuing Volksgrenadiers and enemy armour to pass through Heuem.

Finally at 10:50 the 14th Cavalry Group sent orders by radio for Troop B to withdraw through St. Vith and rejoin the rest of the 32nd Cavalry Squadron northeast of the city.

Continue west along N626 and upon reaching Eiterbach take the first minor road to the right where small wooden signs indicate ‘Eric F. Wood U.S. Monument 2.1 km’. At this distance from the main road on an uphill stretch of road and on the left stands a small stone cross, erected on the spot where Lt. Wood’s body was found in late January 1945.

In numerous accounts of the battle, a number of authors have subscribed to the theory that Lieutenant Wood teamed up with other American ‘stragglers’ to form some sort of guerrilla band which harassed the Germans in the forest around Meyerode continually over the next few weeks. On page 99 of his book Decision at St. Vith, the author Charles Whiting indicates that two local civilian men, discovered Lieutenant Wood’s body and those of ‘several Germans’ on 23 January 1945. Neither Whiting nor any other author who has written about Wood has ever identified or located any dead or surviving Americans supposed to have been in Wood’s group. Whiting goes on to state that ‘the villagers buried him where he had died in the woods’ and goes on to tell his readers that ‘the grave is still there, a quarter of a century later’. Lieutenant Eric Fisher Wood’s grave is in the Henri Chapelle U.S. Military cemetery and the location is G-3-46. Captain Arthur C. Brown, Sergeant Rubendall and the scores of other Americans who found themselves separated from their units had but one goal in mind, that of reaching friendly lines. In 1983, Staff Sergeant Francis H. Aspinwall of Battery A, 589th Field Artillery Battalion wrote:

‘On December 17, I was part of that ‘rabble’ fleeing for safety behind American lines. Let me say, in all honesty, if on that day, had I met Eric Wood, and he had asked, or ordered, me to join his wolf pack, I would have told him he was suffering from battle fatigue and promptly reported the incident to my superiors!’

The stone cross marking the place where local people from Meyerode found the body of Lieutenant Eric Fisher Wood. (Author’s collection).

No one has ever attempted to discover the supply source of this ‘roving wolf pack’, who would, given their supposed guerrilla activity spanning a few weeks, have used up considerable amounts of food and ammunition.

In his book A Time for Trumpets Charles B. MacDonald sums up the Eric Wood legend as follows:

‘For the Belgian civilians, at any rate, there were no doubts. Whether Lieutenant Wood died on December 17 while trying to reach St. Vith or whether he did indeed fight on with a small band of men, the Belgians erected a monument to him in the forest where, they say, he for long continued to fight. Set at the edge of a patch of fir trees along almost eerily silent gravel [now a tarmac trail], it is a touching memorial’.

Turn around and return to Eiterbach turning right onto the main road in the direction of St. Vith. You will climb a hill on which the left side of the road is forested while the right side is open fields. At the top, you pass a minor road leading right to the village of Wallerode. Stop near this junction.

This hill is called the Prummerberg and dominated not only the road from Schönberg to St. Vith but also a minor road from the Our River via Schlierbach to St. Vith. A combined force of engineers from the 81st and 168th Engineer Combat Battalions defended the Prummerberg. The 168th Engineer Combat Battalion command post was located in the schoolhouse at Wallerode. In their attacks toward St. Vith the Germans would use both roads over the Prummerberg as well as the road from Winterspelt via Steinbrück to St. Vith. General von Manteuffel himself placed great importance upon the capture of St. Vith and intended to make his main attack against the town in strength across the open fields between it and Wallerode. Problems of traffic congestion hampered the German advance to the extent that both von Manteuffel and the Army Group B commander, Field Marshall Model took a personal hand in trying to sort out the traffic jam at Schönberg. Lieutenant Colonels William L. Nungesser and Thomas J. Riggs of the 168th and 81st Engineer Combat Battalions respectively, decided that this high ground, about a mile outside of St. Vith, must be defended in order to prevent the attacking Germans from firing directly into the town.

As the engineers began digging in on either side of the road an artillery observation plane flying above the road spotted a German column of infantry led by an assault gun about two miles east of the Prummerberg. Gunners of the 592nd Field Artillery Battalion fired a volley of 155mm shells setting alight the assault gun and dispersing the accompanying infantry. This enemy column would be further delayed by the appearance of three P-47 fighter-bombers, which strafed it repeatedly inflicting heavy casualties. At no time that day did the Germans use more than three assault guns and one or two platoons of infantry in their piecemeal attacks west of Schönberg. The successive concentrations laid by the American artillery on Schönberg and both sides of the road west from 09.00 must have affected enemy movement considerably.

Brigadier General William M. Hoge commander CCB 9th Armored Division at St Vith. General Hoge had led the 5th and 6th Engineer Special Brigades on Omaha Beach on D-Day. His combat command captured the Ludendorf Bridge over the Rhine at Remagen on 7 March 1945. (US Army Signal Corps).

The original German plan of advance called for the mobile battalion of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division to advance upon St. Vith from Wallerode. The bulk of its advance guard toiled through the woods toward Wallerode, arriving there in the early morning. At about 08.00 on the morning of 18 December, the Germans launched a reconnaissance in force northeast of St. Vith, advancing from Wallerode toward Hünningen. Here, only 2,000 yards from St. Vith, two troops of the 87th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron and a few anti-aircraft half-tracks were forced back toward St. Vith. As the cavalry commenced its delaying action, a hurried call went out for CCB 9th Armored Division to send tanks and anti-tank guns to the rescue. Two companies of the 14th Tank Battalion and one from the 811th Tank Destroyer Battalion joined the fight knocking out six armoured vehicles and effectively stopping the German attack.

Late on the afternoon of 17 December, the Prummerberg defenders were joined by men of the 38th Armored Infantry Battalion and Troop B of the 87th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron astride the Schönberg road. On 18 December, the attacking Germans tried three times to rush their way through the foxhole line occupied by the 38th Armored Infantry and Troop B but, aided by engineers and supporting artillery, the Americans drove back these attacks.

Continue in the direction of St. Vith and on the downhill stretch at a sharp bend to the right turn left and back uphill in the direction of Schlierbach. Upon reaching the crest of the Prummerberg, on the left-hand side of the road, you will see the monument to the 168th Engineer Combat Battalion (signposted US Monument). Stop at the monument. When facing it at the time of writing, in the trees to left side of the dirt trail off to your left, a number of slit trenches dug by Company B of the 168th can still be seen.

Veterans of the 168th Engineer Combat Battalion at the Dedication of their memorial atop the Prummerberg. (Author’s collection).

First Lieutenant William E. Holland, commanding officer of Company B, 168th Engineer Combat Battalion participated in the defense of the Prummerberg. Initially, Lieutenant Holland found himself in the woods overlooking the road to Schönberg where he earned himself a Silver Star for his part in stopping a combined attack by infantry and an assault gun of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division. Upon the arrival of reinforcements from General Robert W. Hasbrouck’s 7th Armored Division, the 168th commander Lieutenant Colonel Nungesser informed his company commanders that they were to re-align their front lines with Company B occupying the crest of the Prummerberg.

At one stage in the fighting here, Lieutenant Holland was briefing a Lieutenant in command of two tanks from the 14th Tank Battalion when four German assault guns burst out of the trees about 1,200 yards down the road to Schlierbach. Retired Colonel Bill Holland recalled that incident in a letter to the author:

‘About 14.00, two Shermans with 76mm guns came up the road behind us. The lead tank under the command of a 1st Lieutenant stopped right beside our main line of defense. I jumped up on the tank and was briefing him on the situation when what we thought were four tanks (assault guns) broke from the woods to our front left coming straight down the road towards us. The lieutenant asked me if I was sure they were German and I replied “Hell Yes! Shoot the sons of bitches!” At the time I was not sure if they were friendly or not. He gave his gunner a fire order and I jumped off the tank. He hit the lead “tank” with his first shot, spun it sideways and set it alight. Some crewmembers jumped out and fled while the other three vehicles turned to their left behind a house and back into the woods at full speed. The lieutenant then backed downhill slightly so they couldn’t be hit by direct fire.

‘Things quietened down and I couldn’t help but wonder if we had knocked out a German or American tank. I took a couple of my men with me and we worked our way several hundred yards to the front of the Company B main line of resistance where I could see the knocked out vehicle clearly with my field glasses. There was the prettiest black and white cross on the assault gun that I had ever seen’.

Colonel Holland also recalled the approach of a lone enemy infantryman later in the battle:

‘A single German soldier walked from the woods toward a house [the first house along the Schlierbach road] past the 168th with his rifle at sling arms. I’m not sure if we first yelled at him to surrender, but he ignored us and kept walking toward the house. When he was about 25 yards from the house and about 250 yards from us, I told a small group of men near me to ‘get him’. At least four or five men in prone position with M-1 rifles shot him; I also shot him with my M-1 carbine. There must have been at least eight shots fired but we only hit him once in the leg. He lay there crying, while our medics pressured me into letting them go get him. After five minutes, I relented and told them to do so. I was afraid the Germans would kill them out in the open. They went out and got him without being fired upon. I later learned that he was hungry like many of the attacking troops and was going to the house in search of food’.

On the night of 21 December, at 21.30, the defenders of the Prummerberg received orders from Brigadier General Bruce C. Clarke, then commanding the troops defending St. Vith, to withdraw behind the town. This order proved impossible to execute, so individually, or in small groups the Prummerberg defenders tried to make their way out on foot. Given the then ferocious German attack along the Schönberg road, Lieutenant Holland and the men with him took a small path through the woods (still visible at the time of writing directly opposite the monument) hoping to reach the Steinebrück – St. Vith road.

Continue in the direction of Schlierbach and on the far left side of the village turn right in the direction of Alfersteg on the Our River. Upon reaching the river, turn right just before the bridge passing through Weppeler and past a sign for St. Vith on your way to Steinebrück. In Steinebrück, stop at the ‘T’ junction with the N646 (Prum – St. Vith road).

On 17 December, Generalmajor Friederich Kittel’s 62nd Volksgrenadier Division attacked and by daybreak captured the village of Winterspelt, three miles to the Southeast of Steinebrück. The commander of LXVI Panzercorps General der Artillerie Walther Lucht came to Winterspelt in person to supervise the attack on the bridge at Steinebrück. The 62nd Volksgrenadier Division had suffered heavy losses in its attacks near Heckhuscheid and the division on its left, now pulled out and left the 62nd to go it alone. This seriously damaged Lucht’s ability to exploit the dent hammered into the American lines at Winterspelt. The right regiment of the 62nd advanced almost unopposed north of Winterspelt while the division centre, now composed of Oberst Arthur Jüttner’s 164th Regiment, reinforced by assault guns and engineers, continued beyond Winterspelt to occupy the saddle which overlooked the approaches to Steinbrück.

Brigadier General William M. Hoge’s CCB, 9th Armored Division arrived in St. Vith before dawn on 17 December then began moving forward to the west bank of the Our River.

By 09.30, elements of CCB had crossed the Our at Steinbrück and attacked German infantry dug in on high ground overlooking the village of Elcherath. In subsequent fighting that day, CCB captured Elcherath only to be told by General Jones of the 106th Infantry Division to withdraw back across the Our that night of 17/18 December. The withdrawal completed CCB and the 424th Infantry occupied a seven thousand-yard line from Weppeler to Burg Reuland along with Troop D of the 89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, the latter holding the three thousand-yard sector between Steinebrück and Weppeler.

On 18 December as elements of the cavalry contingent began moving out of the area on their way to help stem the threat developing north of St. Vith, General Hoge cancelled the movement order due to increased enemy pressure here at Steinebrück. As the morning wore on, the Germans increased in number, slipping into positions on the south bank under the cover of exploding smoke shells. To counter this threat the light tank platoon moved into Steinebrück, leaving the American left uncovered. A provisional rifle company from the 424th Infantry west of Steinebrück took off and one of the cavalry platoons had to be switched hastily to cover this gap.

Thus far, the all-important bridge had been left intact, in the hope that part of the 423rd Infantry might free itself from the Schnee Eifel trap.

By noon, the situation was such that the little group of troopers dare delay no longer. On General Hoge’s orders, a platoon of armoured engineers went down and blew the bridge – almost in the teeth of the Volksgrenadiers on the far bank.

An hour later, the platoon west of the village saw an enemy column of horse-drawn artillery moving into position. American gunners west of Lommersweiler answered the cavalry call for aid. An hour later however, some twenty-two enemy guns opened fire in support of an attack across the river, crossing the Our and passing through unoccupied Weppeler to hit the cavalry left flank. Only five Americans escaped. Two or more enemy companies crossed near the blasted bridge and despite the pounding delivered by the 16th Field Artillery Battalion, and the rapid fire from the cavalry tanks, assault and machine-guns, had nearly encircled Troop D. A cavalry request from medium tanks couldn’t be met; General Hoge had no reserve. A Company of the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, however, came in to cover the cavalry left flank. With German infantry now inside Steinebrück and their artillery knocking out the American vehicles one by one, the cavalry withdrew toward St. Vith.

His line no longer tenable, General Hoge consulted General Jones and the two decided that the combat should withdraw from the river to higher ground. Commencing at dark, the move went off unhindered and CCB took up positions two and a half miles southeast of St. Vith blocking the Winterspelt – St. Vith road and the valley of the Braunlauf Creek.

Continue in the direction of St. Vith and upon passing under the viaduct proceed through Wiesenbach, stop with the wooded Volmersberg hill off to the right of the road.

Upon reaching the wooded hill to your right and overlooking the Steinebrück road, the American engineers who’d escaped from the Prummerberg, split into smaller groups. Lieutenant Bill Holland of Company B, 168th Engineer Combat Battalion, took eight of his own men and an artillery observer in an attempt to cross the road only to find that the Germans had posted guards every two to three hundred yards along the road. By then, totally exhausted, the engineers made their way to a house near the highway and surrendered to a group of Germans, that Holland later estimated to number seventy.

The Germans loaded and locked their prisoners in a closed van with wire mesh over its windows and drove out into the woods where the van stopped as the two Germans in the cab argued for minutes, Holland supposed over the fate of their prisoners. The matter apparently resolved, they returned to the road and drove several miles before unloading the Americans at what appeared to be a Regimental Command post for interrogation. The prisoners received no food over the next couple of days.

Continue towards St. Vith and upon entering St. Vith take the third exit at the main traffic circle heading down Klosterstrasse. Go as far as the school and note the monument to the 106th Infantry Division. Return to the traffic circle and take the third exit following signs for Stavelot/Malmedy down the town main street. At the far edge of town across the road from the town cemetery off to your right is a black marble monument to the 2nd Infantry Division.

Prior to the arrival of the 106th, the 2nd occupied positions in the Schnee Eifel east of St. Vith. On 11 December 1944, incoming troops of the 106th replaced those of the 2nd who then moved north to take part in the attack toward the Roer Dams.

Continue in the direction of Stavelot/Malmedy and at the traffic circle in the village of Hünningen, take the third exit following signs for Vielsalm/E-42. Pass under E-42; continue through Rodt to Poteau where you turn left and stop on the left. The large stone house across the street from the road from Rodt served as the temporary command post of the 14th Cavalry Group during its brief time here.

On 22 December, the overall ground commander in the area, Field Marshall Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, informed the 7th Armored Division commander, Brigadier General Robert W. Hasbrouck that his division had done what was expected of it and was hereby ordered to withdraw from St. Vith. The initial plan called for the withdrawing Americans to form an oval-shaped defensive position to be known as the ‘Fortified Goose Egg’ in front of and encompassing Vielsalm. Later, the decision was made for this withdrawal to be made as far as the west bank of the Salm River at Vielsalm. Three roads lent themselves to this withdrawal. This one, the main St. Vith to Vielsalm route through Poteau, a gravel road leading through a forested area called the ‘Grand Bois’ and General Clarke’s headquarters location of Commanster to Vielsalm, and lastly the road leading along the Salm valley into Salmchâteau from the south.

Upon falling back from the Manderfeld area, the 14th Cavalry Group established its command post here in the building diagonally opposite the road from Rodt. Early on 18 December, in keeping with orders from 106th Division, the acting Group commander, Lieutenant Colonel Augustine Duggan intercepted elements of the 18th Cavalry, Troop C of the 32nd and the one remaining platoon of towed 3-inch guns of the 820th Tank Destroyer Battalion. He placed them under the command of Major J. L. Mayes as a task force to comply with orders from the 106th to return to Born, which they had just evacuated, and occupy the high ground.

Task Force Mayes moved out toward Recht at first light on 18 December but had only gone some two hundred yards when German bazooka fire set the leading tank and armoured car on fire. The glare of the burning vehicles silhouetted the figures of enemy infantrymen advancing toward the Poteau crossroads. The cavalrymen pulled back into the village and hastily prepared to defend the dozen or so houses there, while to the north a small cavalry patrol dug in on a hill overlooking the hamlet and made a fight of it. By this time, the remnants of traffic, including vehicles of CCR, 7th Armored Division, milling around the village were leaving.

All through the morning the Germans pressed in on Poteau, moving their machine-guns, mortars, and assault guns closer and closer. At noon the situation was critical, the village was raked by fire, and the task force was no longer in communication with any other Americans. Colonel Duggan finally gave the order to retire down the road to Vielsalm. Three armoured cars, two jeeps, and one light tank were able to disengage and carried the wounded out; apparently a major part of the force was able to make its way to Vielsalm on foot.

US Army Artist Harrison Standley painted this picture of the Poteau road junction after the battle. (US Army collection The Pentagon).

What are definitely among the most well-known photographs and film taken during the battle by either side, are the series of shots taken by German cameramen and cleverly analysed by Jean Paul Pallud on pages 209-224 of his monumental Battle Of The Bulge – Then And Now. These widely published shots were taken on a curve a few hundred yards along the road from Poteau in the direction of Recht.

The German units attacking Poteau on 18 December were elements of the 1st SS Leibstandarte, which, by that evening had left the area. In a counterattack, Colonel Dwight A. Rosebaum’s CCA, 7th Armored Division regained Poteau and deployed around the village with CCR on its right flank.

Poteau lends itself well to defensive action. It stands at the entrance to the valley road that leads to Vielsalm, and mechanised attack from either Recht or Rodt had to funnel through the narrow neck at this crossroads, vehicle manoeuvre off either of the two approaches being almost impossible. Away from the crossroads the ground rises sharply and is cluttered with thick stands of timber. The formation adopted by CCA was based on a semi-circle of ten medium tanks fronting from northwest to east, backed by tank destroyers with riflemen in a foxhole line well to the front. About 10.45 the blocking troops left by the 9th SS Hohenstaufen Panzer Division made an attack. Tank and artillery fire stopped the Germans just as it had on previous days. Perhaps the enemy would have returned to the fray and made the final withdrawal hazardous. However, shortly after noon, some P-38’s of the 370th Fighter Group, unable to make contact with the 82nd Airborne Division control, to which they were assigned, went to work for the 7th Armored Division, bombing and strafing along the road to Recht. The enemy recovery was slow.

American convoy caught on the road from Recht to Poteau and destroyed.

At 13.45 General Hasbrouck sent the signal for CCA to pull out. In an hour the armoured infantry were out of their holes and their half-tracks were clanking down the road to Vielsalm. Forty minutes later the tanks left Poteau, moving fast and exchanging shots with German tanks, while the 275th Field Artillery Battalion fired a few final salvos to discourage pursuit. When the last vehicle of CCA roared over the Vielsalm Bridge (at 16.20) the remaining artillery followed; then came the little force from CCR, which had held the road open while CCA made its withdrawal. Darkness descended over the Salm valley as CCR sped across the Vielsalm Bridge.

Continue in the direction of Vielsalm and on reaching Petit Thier take the first minor road to the left passing through the nearby village of Blanchefontaine. Continue on the same blacktopped road into the woods (bearing left at a white wooden cross) as far as the small white chapel of Tinseux Bois on the right side of the road. Turn around and stop by the large house opposite the chapel.

After abandoning their remaining vehicles and escaping from the village of La Gleize, SS-Obersturmbannführer Jochen Peiper and the remnants of his once strong Kampfgruppe Peiper came to Petit Thier for a few days rest and refit. In 1969, the wartime Catholic priest, Curé Cahay sent the author extracts of the parish records covering Peiper’s arrival in Petit Thier and his having lodged in this house:

‘On the evening of 24 December SS troops arrived in Petit Thier and occupied the more comfortable houses in the village. They said they were waiting for replacement vehicles (which never arrived). Their commander, Peiper, was at Tinseux and after they left, the bodies of some executed Americans were discovered there.’

With the road blocked with burning American vehicles these SS Panzergrenadiers take to the field alongside the road.

The Tool and Weapons Sergeant of Peiper’s Headquarters’ Company, SS-Unterscharführer Otto Wichmann in a post-war statement made of his own free will, spoke of the killing of one such American prisoner here at Tinseux Bois. The man in question had emerged from the woods and surrendered to the Germans whereupon they took him into the house where Peiper, the unit surgeon Dr. Kurt Sickel, and an unidentified Sturmbannführer examined his papers. In his statement, Wichmann describes the prisoner’s fate:

‘Sturmbannführer Sickel motioned with his thumb to me and said in a sharp loud voice, ‘Get the swine out and bump him off’. I then went into the nearby chapel in which the communications platoon was billeted and I borrowed a pistol. I led the prisoner along the road accompanied by Sturmmann Einfalt. At the road fork, I took the right fork, which leads uphill. The American could only walk a few steps at a time; then we had to support him, as he could not continue. We came to a spot on the road and I turned right into the woods. Up to this point we had been leading the American. From there on I had him go to the wood in front of us. However, he did not reach the wood, only up to the edge of the wood approximately fifteen to twenty metres away from the road. I only went a few metres into the field and then I stopped and brought my weapon into position and I shot the American two or three shots. I am a good pistol shot. Normally, I had to test the repaired weapons, as I was the weapons sergeant. After the shooting I went into the chapel and returned the pistol. Then I returned to the stable and we all had lunch.’

Return to Petit Thier turning left at the main road in the direction of Vielsalm. Pause by the church in Petit Thier.

Lieutenant Colonel John P. Wemple commander 17th Tank Battalion, 7th Armored Division on the heights above Recht. (Author’s collection courtesy Colonel Wemple).

Early on the morning of 18 December, Headquarters CCR, 7th Armored Division, set out from Poteau in the direction of Vielsalm. Upon arrival here in Petit Thier, the men of CCR discovered that Lieutenant Joseph V. Whiteman of the 23rd Armored Infantry Battalion, separated from his column on the march south, had heard firing at Poteau. He had rounded up a collection of stray tanks, infantry, cavalry and engineers under the name of ‘Task Force Navajo’ to block the road to Vielsalm. The CCR Commander took over this roadblock and, as the force swelled through the day with incoming stragglers and lost detachments, extended the position west of the village. Thankfully, the German column at Poteau, however, made no attempt to drive on to Vielsalm. The main body of the 1st SS Leibstandarte Panzer Division needed reinforcements. The Panzergrenadier Regiment and the assault guns therefore left their assigned route and turned Northeast to follow the column passing through Stavelot.

Continue toward Vielsalm passing through Ville du Bois and upon entering Vielsalm, pause by the M4A1 Sherman tank on the left before the traffic lights.

This tank commemorates the role of the 7th Armored Division in the Battle of the Bulge.

Continue straight ahead past the traffic lights in the direction of Marche and stop at the junction with N68 (joining you from your right rear at the bottom of the hill).

This is General Bruce Clarke Square, named in honor of the wartime commander of CCB, 7th Armored Division. While not strictly speaking a ‘square’, it features a monument bearing the 7th Armored Division shoulder patch. Upon withdrawal to the far (west) Bank of the Salm River and establishment of the so-called ‘Fortified Goose-Egg’ American troops blew the road and rail bridges over the Salm effectively stopping any further enemy advance across the river in Vielsalm.

Men of the SS-Leibstandarte pause to sample captured American cigarettes.