Winners act while losers agonize over what to do.

However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.

—WINSTON CHURCHILL

FORMULATING A STRATEGIC STATEMENT HAS BECOME A corporate ritual, a way to keep bad spirits at bay. Stakeholders have grown to expect a clear and workable strategy emanating from the top of the corporation. Customers and suppliers, employees, and—most important—shareholders and bondholders demand proof that top management knows what it’s doing in the form of a strategy. Strategies are supposed to give each department, unit, and individual throughout the organization a sense of direction and a path to achieving good performance, financial or otherwise. And sometimes strategies are indeed beautiful, especially when they contain the attributes that we expect to find in business leaders: vision, boldness, and grandiosity.

But strategy making can and does become an obsession. Too often, American, European, and Japanese multinationals suffer from a new type of corporate malaise—too much strategizing. Top managers agonize over how to formulate the perfect strategy, and when they hit upon one that captures their imagination, they get infatuated with it. Even worse, when they see performance declining, they tend to focus on changing the strategy instead of honing in on what is likely the real culprit—execution.

In his best-selling book, From Good to Great, Jim Collins concludes that “there is absolutely no evidence that the good-to-great companies invested more time and energy in strategy development and long-range planning.”1 Indeed, in company after company, Collins found that the same strategy could lead to very different results depending on who the managers were and how they exercised leadership.

So why do executives spend so much time worrying about strategy? Why do they enjoy strategy making so much? For starters, strategizing is a good method for escaping from the nitty-gritty aspects of reality. It can even become a form of daydreaming. Execution is simply not the kind of task that the top brass finds attractive or worthy of its time. Unlike strategizing, execution requires attention to detail, precision, and constancy. Little surprise, then, that managers at so many established firms favor delegating the many nuisances involved in execution. They prefer to do the big thinking while other, often lesser paid employees are told to worry about the day-to-day.

In reality, CEOs should be deeply engaged in execution, or else change their title. Strategy determines where a business wants to go, but execution is the art of getting there. Execution means being prepared to put in practice a value proposition aimed at doing well what is good for customers—delivering products and/ or services efficiently and on time. Clearly, the winning approach involves executing before strategizing. Benetton and Matsushita are ready examples of companies with strategizing run amok.

Benetton, the Italian fashion firm once admired for its colorful sweaters and global reach, has tried at least six strategies for cracking the American market over the past decade. Management first tried exports from Italy, which turned out to be too expensive because of high manufacturing and transportation costs, and simply not in tune with consumer preferences across the ocean. Try as Benetton might, most American males simply won’t buy brightly colored sweaters.

Next, the company tweaked the designs and the distribution channels, also to no avail. Then they brought in provocative billboard ads from Europe, featuring worthy causes like preventing AIDS or improving race relations, and Americans found them offensive or a naked attempt to exploit sensibilities for profit. Still later, Benetton enlisted Sears and a South Korean manufacturer in a joint venture that fell apart in the wake of the backlash against some of the controversial posters. Most recently, management has made an attempt to imitate competitors by opening megastores.

There was nothing intrinsically wrong with any of these various strategies, but the fact remains that none of them boosted the company’s fortunes in the U.S. market, the world’s largest. And here’s why: top management disengaged itself from execution, did not follow up on details, and did not help middle management fully grasp the positive and negative feedback loops of each new strategy. They thought that their job was done once the strategizing was completed.

“The United States is very competitive and requires a specific strategy,” argued Vice President Alessandro Benetton in 2010, after 20 years of losses in the American clothing market. “We are considering some alternative in terms of a specific plan for the United States.”2 But while Benetton trots out new schemes, hoping to experience a strategic epiphany, brands like H&M and Zara have surged ahead. The value of their brands now exceeds Benetton’s many times over.

Another example of a business that tragically neglected to emphasize execution: once upon a time people praised Matsushita’s 250-year strategic plan. It was visionary, audacious, even epic, and it seemed to set the company on a path toward unending domestic and international growth, catapulted by the wonders of its powerful brands: Panasonic, Technics, and JVC. Such an ambitious plan certainly motivated employees by infusing their daily routines with purpose and meaning. Perhaps, then, the Japanese consumer electronics and electrical appliances giant—now known as Panasonic—should be admired for an unwavering belief in long-range planning and grand strategizing. But is it really wise to make decisions today that could tie up resources into the distant mists of time, especially in a rapidly changing global economy? To be fair, the company founder’s faith in far-sighted planning was matched by a compulsive attention to detailed implementation and execution on the factory floor, where humans and machines transformed raw materials into products with mass appeal. Konosuke Matsushita instilled in his employees the values of precision and perfection. What’s more, Panasonic offered a unique value proposition: products of high quality at an affordable price.

But American and European observers and managers took note of the company’s strategy and long-range planning rather than of its more mundane capability to implement and execute, with dire consequences for many of Panasonic’s Western rivals. Thus, Phillips and the now-defunct AEG spent years trying to come up with a long-term strategy for success in consumer electronics and household appliances, without focusing on what really made Panasonic work: operational excellence. European and American appliance makers failed to match the Japanese zeal for manufacturing excellence.

In time, too, the Japanese company forgot its own formula for success. Managerial turnover at the top, embarrassing product quality problems, and a rapid decay in design and marketing capabilities made Panasonic vulnerable to new competitors, and its market share and financial performance plummeted at the hands of South Korean and Chinese electronics and appliance companies. But make a note of why this happened, frame it, and hang it on the wall behind your desk: the issue wasn’t that Panasonic had long forgotten its 250-year strategic plan. Rather, it lost ground in the marketplace because it failed to implement and execute with the passion that made it one of the greatest companies of the twentieth century. Top management was, well, sitting complacently at the top, unlike the founder’s team of decades past, who spent most of their time on the factory floor and visiting retail outlets, constantly looking for ways to improve both products and operations. Panasonic executives simply forgot the lesson that execution is everything. Strategy formulation needs to be preceded and followed by execution.

The fact is, mundane execution has become much more important than strategizing in the fast-changing global economy of the twenty-first century. Most companies that call for a strategic reorientation of their business are really trying to cope with impending disaster as other companies that are better executors eat market share away from them. Strategizing can also lead to blind alleys. When companies define a market or a product as strategic, what they are frequently thinking is “We are going to lose money, but we really want to keep on trying.” Thus, grand strategies often lock companies into a path toward competitive decline. The very rigidity of such plans chokes creativity and limits growth in new areas.

Don’t get us wrong: there is a place for strategy in the corporation, but it should not come at the expense of execution. Top management needs to pay attention to both, without delegating the latter. Critically, many of the best strategies are emergent—that is, rooted in practice instead of imposed from above. Innovation in new products and in new ways of making and selling them involves experimentation. Corporations learn by doing, formulating and adapting their strategies as they go. Strategy should not precede and supersede execution, especially when uncertainty is rampant. In this unstable and uncertain global economy, execute first, then strategize based on what you learn along the way. Spending months or years formulating what you believe might be the best strategy is a self-defeating exercise in a world that changes so fast and is mired in the unexpected.

While multinationals in the developed world have been busy strategizing, nimbler emerging market firms have been executing their way into leadership positions in industries as diverse as bakery, aircraft, and IT services. No obvious commonalities exist across these three very different types of businesses. The one key thread running through them is precisely the importance of execution for competitive success. The winners from emerging markets did not fall into the trap of overstrategizing because they started out by looking for a low-cost and relatively unsophisticated way to get into the game. Their path to success was by excelling at execution and by adopting a real-time approach to strategy. They came up with winning strategies through learning by doing and experimentation. Their winning sequence could be yours: execute, strategize, then execute again.

Let’s begin with bread—one of the world’s most important staple foods, providing billions of people with a large proportion of the energy and nutrients they need. Bread has contributed to the culture, language, and idiom (“breadwinner,” “breaking bread,” etc.), and plays a key ceremonial role in several religions. Bread is also a dynamic industry in which innovation and knowledge are relevant to competitive success.

Bread is not only a big business, worth over $400 billion annually, but also one that is becoming more complex and sophisticated as consumers increasingly expect variety and convenience, and lean toward both indulgence and healthy choices. Notwithstanding the fact that rice remains the dominant staple in China and the rest of East Asia, bread is also more and more a global product. Individually wrapped bread-product variants are selling increasingly well in parts of the world where traditional bread has never been able to gain much market purchase.

While the Europeans are the biggest bread eaters, American firms brought modern mass production, distribution, and marketing to the industry, and nobody did it bigger than the Sara Lee Corporation. Once known as the Leading Fresh Bread Brand in America and the Cheesecake Company, Sara Lee was seemingly invincible, and not only in baked goods. The company deployed its marketing prowess across a bewildering array of industries and widely divergent premium brands, including apparel, beverages, coffee, meat, snacks, tobacco, leather goods, personal care, shoe-care products, and even some household items.

By the late 1990s, though, the giant was showing feet of dough. Investors demanded a new strategy, one that would enable the firm to overcome its lackluster performance in the wake of enhanced competition. Sara Lee responded by divesting from “noncore” businesses and focusing on “core” ones, such as food, beverages, and personal-care products, a strategy that few people would take issue with. Yet even this didn’t work. In 2001, sales exceeded $17 billion; by 2010, they were down to less than $11 billion, and the company had shed nearly 75 percent of its employees.

What went wrong? The answer is actually fairly simple: the company was not motivated to execute. Too much energy spent thinking about what was core and what wasn’t did not solve the far more mundane problem of performance—of making, distributing, and selling bread. Succeeding in the low-margin bread business meant looking for ways to be more efficient in production, nimbler and quicker in distribution, and more persuasive in marketing and sales. Sara Lee executives didn’t have the patience for all of that—and they thought that the bread business was not that interesting or core anyway. “Bread is fundamentally a very difficult business,” noted Tim Calkins, an analyst for Strong Brands. “It is capital-intensive and very dependent on operational excellence, getting the right amount of bread to the right stores at just the right moment…. Faced with a difficult, lowmargin and slow-growth business Sara Lee elected to give up and sell it off.”3 The buyer was Bimbo, a Mexican firm that thus consolidated its position as the world’s largest bread company, including such iconic products as Thomas English Muffins, Pan Bimbo, and Mrs. Baird’s breads.

Bimbo had an entirely different approach. “We’re not buying Sara Lee’s unit for what it’s worth today, but for what it’s going to be worth tomorrow,” Bimbo CFO Guillermo Quiroz said at the time.4 In fact, he had good cause to be optimistic.

While Sara Lee had lost its sense of direction and purpose by expanding into too many businesses, Bimbo knew that “focusing on what you can do well” and excelling at execution is crucial. Because executives paid attention first to detail, the company eventually managed to produce, distribute, and market both global and local bread products using 100 efficient local plants, tens of thousands of trucks, and over one million points of sale in 18 countries.5

Bimbo once owned flour mills and other factories producing some of its inputs but sold most of them to concentrate its efforts on bread itself. Now Bimbo runs its factories 24/7 in a business that requires speed and precision because of the short shelf life of most bread products. But the company’s most significant competitive advantage, the one that sets it apart from other large bakeries, including Sara Lee, is its time-tested methodology for managing a complex distribution network involving tens of thousands of points of sale in each national market. As executives put it, Bimbo’s success is all about “a little vision with a lot of planning.”6

This is a company that does not waste too much time strategizing—worrying about the vision thing. Instead, executives spend most of their time actually running and improving operations, from the baking ovens to the shelf at the small store around the corner.

The company has also developed strong marketing capabilities, including a portfolio of over 150 local brands (including, in the United States, Arnold and Stroehmann’s breads, and Entenmann’s cakes and pastries), as well as the global Bimbo label. And its global reach means that it can as easily appeal to Hispanics in the United States as well as to Chinese consumers craving Mexican-style foods.

Being a truly global bread company isn’t easy. Consumer tastes and dietary needs differ massively from country to country. Brand awareness is also a national issue. People even have distinct preferences as to single- versus multiple-portion packaging. And different cultures eat their bread at different times of the day and together with different types of other foods. In some countries, people love to buy their baguette at the small shop around the corner, while in others large stores are the norm. Competition is tough—you cannot patent a product variant.

Producing the bread on a global scale isn’t easy either. Transportation cost and short shelf life require manufacturing close to the customer. Costs for raw materials are on the increase because of climate change, droughts, and the diversion of crops toward biofuels production. In many countries governments regulate the quality and price of staple foods, and protect domestic producers. To top it off, timely distribution to the consumer requires negotiating with truckers’ unions and anticipating traffic problems. Note that none of those issues involves strategy per se—they’re all about execution. Sara Lee had neither the energy nor the stamina to deal with it all.

In all fairness, bread was probably a business that Sara Lee never should have entered in the first place. Unlike many emerging market companies, Sara Lee executives were under pressure to deliver profitability in the short run. “The bakery division accounts for 20 percent of Sara Lee’s revenue, but only 5 percent of consolidated operating income,” argued Morningstar analyst Erin Swanson. “We’ve long believed that the domestic bread business was Sara Lee’s Achilles’ heel … but we weren’t convinced the firm would look to dispose of the business when it wasn’t firing on all cylinders.”7 Sara Lee eventually gave up rather than make full use of its capabilities in a business it really did not care that much about. As a result of the disposal of the fresh bakery division, “Sara Lee is indeed a simpler, stronger and a better company,” commented CEO Marcel Smits. “The bakery business is not the main driver of our profit.”8

Bimbo is family owned and focused on being a bread-only company, a fundamentally different kind of company from Sara Lee. But its ambition is just as great. In fact, Bimbo is the only bread company with operations on three continents, a predicament that has many advantages. “We know best practices in baking,” explained CEO Daniel Servitje, the son of the founder. “We travel around the globe looking closely at all practices in baking plants. We can compare everywhere, and we can detect a good number of opportunities to raise productivity.”9 In a world in which food and water will soon become more scarce and expensive than energy, Bimbo stands to win big.

The company was founded in 1945 in Mexico City by Lorenzo Servitje, an immigrant from Spain. His father had established a cake shop. After opening his own bakery, he partnered with several family members to launch the company with 39 employees and five delivery vehicles, selling four types of bread. Expansion throughout Mexico took place in the 1960s before spreading to Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s. Expansion to the United States was preceded by exports. The company also entered into a joint venture to distribute Sara Lee products in Mexico. In 1996, Bimbo made its first acquisition in the United States, followed by over a dozen others and culminating in the purchases of the U.S. bakery operations of Weston Foods and Sara Lee.

Acquisitions, though, are the lesser part of Bimbo’s success story. Any business with sufficient cash or leverage can buy its way into a bigger market share, at least initially. Making the acquired company or distribution channel work better and more efficiently is the real challenge.

“I believe in hard work, humility and leaders who have their ear to the ground and understand the nitty-gritty of their operations and markets,” observed Daniel Servitje. “Conditions are constantly changing, so it’s very important to keep a firm grip on the day-to-day realities.”10

From the earliest days of its growth, it seems, the company understood that its distribution system had to run like a Swiss watch. Just-in-time deliveries would reduce the amount of unsold bread returned to the distributors by the retailers, so Bimbo gave them computers—Sara Lee never thought about that. It is hard these days to find CEOs who believe that their job is about truck delivery routes and schedules. Most would much rather spend their time thinking about the next acquisition or the next asset disposal. In the mundane reality of bread making and selling, execution is the cornerstone of profitability.

Bimbo also shows that execution goes beyond efficiency and standardization. The company has learned to differentiate its product offerings by segment and geography. For instance, Bimbo constantly tweaks its recipes to play to the health-conscious consumer. It has eliminated trans fats from all of its offerings worldwide and launched new organic and healthy brands. In China, where growth cannot come from bread loaves, the company focuses on bread-based snacks, wrapped separately. One of the company’s best-selling products is juanqu, rolled bread with layers of beef floss. “It is similar to steamed huajuan, a traditional Chinese food, but it is still bread,” said César Cruz, a Bimbo manager in Beijing.11

A key issue with selling fresh bread in China, according to Bimbo executives, is that many consumers equate fresh with living. Thus, it is necessary to fine-tune the marketing to explain exactly in which ways a packaged food can be considered to be fresh. Bimbo has learned that China’s young urban consumers are the most receptive to its products and is planning to expand the market beginning with that socio-demographic group. Another peculiar challenge involves distribution logistics: the company uses tricycles to deliver its products to small outlets located in the older parts of town where streets are too narrow for trucks. Familiarity with large, chaotic urban settings throughout Latin America helped Bimbo respond to these challenges. Here, too, Sara Lee had neither the experience nor the motivation to enter the Chinese bread market.

Just as they are with so many other products, Asia’s emerging economies are the new frontier for baked goods. China is fast becoming one of the world’s largest markets for them, and growth is driven by both volume and value. India’s market is expected to dovetail with China’s, and Bimbo is uniquely positioned to take advantage of this growth in both countries, given that the markets are crowded with small competitors ripe for consolidation. But this is an opportunity open only to those willing to deal with intricate and tedious details of execution.

The company’s experience in China since it launched its first product in 2007 “has been full of learning, unlearning, experiences, challenges and failures,” admitted Jorge Zárate, Bimbo’s general manager in China. Some products did not work in the market as planned. “I believe that we still have a long way to go and many things to discover.”12

Zárate is not shy about Bimbo’s goals in the world’s soon-to-be largest economy: “Short term is expansion, to deeply understand our clients, [our] consumers, and our competitors, and to develop a local talent [pool]. Medium term is to continue growing and expand as a national brand. In the long term we see China as one of the primary sources of growth for Bimbo Group, as well as a source of innovation and talent to other opportunities.”13 Here we see a strategy wrapped around implementation. You execute to figure out what strategy works, and then you pursue it relentlessly by focusing on execution itself.

Zárate is right: if you can succeed at the improbable task of selling bread-based products in China, you can both leverage product innovations in other markets and redeploy the pool of talented managers that made the impossible happen so that the firm can meet other challenges around the world. Companies often forget that what makes some of them great is not collecting the low-hanging fruit but reaching out to the sky. Thus, Bimbo got the basic sequence right: get down to business, see what works and what doesn’t, improve execution, learn as you go, and then strategize by building your company’s future on the proven basis of the experience gained. Once you have a strategy, don’t forget about following up on the details of execution.

If you think that bread is a difficult industry, consider aircraft manufacturing. Imagine yourself competing in an industry in which every new product launch puts the entire corporation at risk. Moreover, your customers are among the most unpredictable, idiosyncratic, and cash-strapped in the world. One day they place orders for hundreds of millions of dollars, and the next they downsize the contract or cancel it altogether. To make matters even more complicated, airlines are always asking for customized cabin designs, specific engines, and other expensive features. And they have made a habit of placing some orders with you and others with your main competitor, which goes to international court every other year accusing your company of obtaining illegal subsidies, dumping, or worse.

The airlines, of course, are also between a rock and a hard place. They face stiff competition from one another, unpredictable weather, sharp seasonality of demand, irascible passengers who are very price sensitive, strong pilot unions, and rising fuel costs they have no choice but to absorb. It is a business in which most companies teeter around the breakeven point, but few give up. Hence, excess capacity is rampant, and profitability is next to mission impossible. Where airlines win (or at least survive) is by increasing their margins—filling up their planes with as many passengers as possible and turning them around fast, charging additional fees for quality and service, and cutting costs—and better aircraft can help on all three counts. A well-designed, easily serviced jet can carry more passengers and be used for more flights during the same day. Passengers prefer a comfortable, spacious cabin with reduced engine noise. Fuel efficiency and low maintenance costs can make a huge contribution to the airlines’ bottom line as well.

Welcome to the wonderful world of aircraft manufacturing, where execution is also key to success. The industry is divided into two main segments. Boeing and Airbus dominate the market for large aircraft with 110 or more seats. The “regional” segment of aircraft with fewer than 110 seats is also a duopoly: Embraer of Brazil and Canada’s Bombardier. Long gone are Fairchild Dornier, British Aerospace, and Fokker.

Bombardier was the first manufacturer to respond to the airlines’ desire for a regional jet to replace the cramped, noisy, and uncomfortable turboprops used on short commuter routes with high flight frequency. Back in the late 1980s, the Canadians stretched a business jet into a small airliner seating 50 passengers, the CRJ-100. Embraer followed with two new jets specifically for the segment, the ERJ-135 (37 seats) and the ERJ-145 (50). Both manufacturers eventually sold a thousand-plus units of their new regional jets to Continental Express, American Eagle, and other commuter airlines eager to use smaller planes to avoid union restrictions on the crewing of larger jets. And with that, the regional jet market was born. “Twenty years ago no one could see a jet operating with 50 seats being economically viable,” remembered former CEO Maurício Botelho. “Technology developed and today we see thousands of such regional jets.”14

But while Bombardier and Embraer made the regional-jet market virtually in tandem, the race to the top wouldn’t stay tied for long. Bombardier got mired down with quality problems in landing gears and delivery delays. Meanwhile, Embraer was focusing on operational excellence and pulling away from its chief competition. The firm designed low-maintenance jets in anticipation of cost pressures in the airline industry. Next, it designed regional planes, such as the 190 and 195 series, that rivaled their larger counterparts in terms of performance and cabin comfort, while cutting the operational and maintenance costs to the airline.15

Within a few years, Embraer had become the darling of both aircraft connoisseurs and airline passengers. In 2001, Botelho won the Aeronautics/Propulsion Laureate Award given annually by Aviation Week & Space Technology, the leading aerospace magazine, for “correctly reading the transformation of the commuter airline industry from turboprops to jets—an insight not gleaned by many established European and American manufacturers—and by focusing on a single overarching objective: customer satisfaction.”16

Airline executives concur. Embraer is “a company that has proved they know how to build airplanes that the market will want,” argued David Neeleman, founder of JetBlue Airways. “Thanks to the Embraer 190, combined with our narrow-body fleet, we can enjoy the benefits of wider market coverage and develop greater business opportunities, while offering the same level of comfort to our passengers,” said Formula One legend Niki Lauda, founder of Austria’s second-largest airline, Niki.17 Over 80 airlines in more than 50 countries fly Embraer jets.

Given that Embraer was once state-owned, many people dismiss its success as the result of government largesse. But this rapidly emerging multinational has been winning the old-fashioned way: by attaining the best efficiency and delivery ratios in the industry, beating out competitors in Europe and the United States burdened by higher costs and lower operating performance.

As with Bimbo, Embraer’s recipe for success is disarmingly simple. Start by focusing on what you can do best along the value chain, invest in training your human resources, then encourage them to make improvements throughout the manufacturing process.18 One key outcome was to cut assembly times. For instance, Embraer managed to bring down assembly times for its wildly successful ERJ-170 aircraft from 6.5 to 3.6 months.

How did the company actually do it? By adopting Toyota’s famous supply-chain principles. For its older 145 series of planes, Embraer relied on 350 suppliers, four of which were risk-sharing partners. For the 170/190 series, the company cut those numbers to just 38 suppliers, of which 16 shared risks, while offering customers flexibility and performance both before and after the sale. Once Embraer fine-tuned this approach, Bombardier started to lose market share, without being capable of improving its own assembly efficiency and in the face of several embarrassing quality problems. Orders poured into Brazil from airlines around the world, including British Airways, Air France, and major American carriers.

Like Bimbo, Embraer also lacked the kind of technological advantage that made Fairchild, Fokker, or Bombardier formidable competitors. As an emerging market company, it had to create the supplier base almost from scratch in a location with few other advantages save for labor cost. The path to success necessarily required outstanding operations and stellar execution. The company started by making relatively simple planes until they could catch up technologically. By then, neither Fairchild nor Fokker were in a position to survive given their higher costs. Bombardier has stayed in the game, but in an increasingly precarious position.

To make sure the company stays on top, Embraer executives have also set up a network of assembly and service operations in China, Europe, and the United States. Embraer established a majority equity joint venture in China in 2002, with two companies controlled by Aviation Industry Corporation of China (Avic). This move was aimed at reducing its dependence on the U.S. market for export sales while simultaneously gaining a foothold in a market projected to grow fast.

Like other multinationals, Embraer took a road into China that was not carpeted with roses. The joint venture’s deliveries were plagued by delays due to red tape when it came to securing supplies and obtaining certification for the planes. Production of the relatively antiquated ERJ-145, a 50-seater, came to an end in 2010 after assembling a mere 41 units over a period of seven years. Embraer would have liked to retool the plant to assemble the 190 series, which averages 100 seats, but Avic balked at the idea, fearing competition with its own regional jets.

Embraer’s Chinese experience is hardly unique—archrival Bombardier sourced fuselages from China for export but could not sell a single plane domestically in seven years—but the setbacks in China could well be a blessing in disguise, a lesson in executing that is in the short term as important as planes sold.

Indeed, now that it is climbing out of its own adolescence, Embraer’s biggest challenge is to anticipate the impact of the new entrants into the regional segment. Mitsubishi of Japan, an exceptionally capable company, plans to mount a major challenge to the established duopoly by 2014 and has reached an agreement with Boeing to jointly offer customer support. Like Embraer, for the past three years Mitsubishi has been discussing with potential customers even small details such as the overhead luggage compartments.

Russia’s Sukhoi and Avic, Embraer’s old China partner, are also launching a line of regional planes, but both must deal with some fundamental problems, including shedding bad habits acquired during decades under state central planning. While Embraer also started as a state-owned firm, it was privatized in 1994. That leaves Sukhoi and Avic years behind the Brazilian company when it comes to marketing, customer support, and ramping up production to profitable levels.

Almost stereotypically—given Russia’s reputation for building unsafe, uncomfortable, and underperforming aircraft—quality problems beset the first delivery of Sukhoi’s 100-seat Superjet to Aeroflot, prompting the airline to ground the plane. “Yes, it is a Russian aircraft,” said a spokeswoman for the parent company rather defensively. But “it is made in cooperation with world-leading suppliers,” in reference to the French and Italian partners that collaborate with Sukhoi.19

For their part, the Chinese have one key advantage over other new entrants in the field: the country is already a vital node in the global supply chain for the aeronautics industry. But the Chinese also face one significant obstacle: they seem to view the regional jet market as a way station on the way to a bold, even visionary strategy aimed at the large-aircraft segment. “The Chinese people must use their own two hands and their wisdom to manufacture internationally competitive large aircraft,” declared Prime Minister Wen Jiabao in 2008. “It is the will of the nation and all its people to have a Chinese large aircraft soar into the blue sky.”20

That’s understandable—the Chinese have big dreams in every direction these days. But focusing on the stars is not the best attitude to have when what matters is patient execution and attention to detail. Emerging market firms, it turns out, are not immune to the “strategy thing,” especially when government asks them to pursue goals that go beyond the purely commercial to include national status and pride. Note the difference with Embraer: “We will never make a move toward a larger aircraft on pure strategic vision or something like that,” asserted CEO Frederico Fleury Curado.21

Embraer is one of the most inspiring business stories from emerging economies. “This is the only company in the entire world that has successfully entered the market for building aircraft since 1960,” observed airline analyst Richard Aboulafia, “and it’s the only company that’s entered the jetliner market since World War II for regional aircraft. That’s an extraordinary achievement.”22 Stellar execution made Embraer the great company that it is today. It also is a forward-looking company, being the first manufacturer to fly a jet powered by ethanol.

The global IT services business is worth some $300 billion and dominated by companies that took advantage of their position as hardware manufacturers to become IT service providers. Hewlett-Packard, Fujitsu, and Xerox managed that kind of transition while their traditional hardware businesses declined, but IBM has been the one that really excelled in this transition, both as measured against its own American peers and as weighed against a whole slew of upstart, emerging market rivals. IBM’s IT services revenue is about $40 billion, while the two emerging market multinationals among the sector’s top 15, India’s Tata Consultancy Services and Wipro, are merely one-eighth the size of Big Blue.

As uncomplicated as it seems, putting the business model of IT outsourcing into practice is quite demanding. It involves designing, operating, managing, and/or supporting the information and communication systems of clients. These companies also run their clients’ business processes, such as logistics, human resources, and customer relationships. Simply put, IT is all about execution. From its inception some 50 years ago, success in the IT sector depended more on labor productivity than on capital requirements—people, not machines, were the crucial factor. Companies had to set up shop next to their clients, and most large clients were in Europe, Japan, or the United States. Emerging markets could well have been located on another planet as far as this industry was concerned.

And then an asteroid struck Earth in the form of the telecommunications revolution, transforming IT services outsourcing beyond recognition and dissolving many of the traditional competitive advantages of the incumbent players from Europe and the United States while placing emerging market companies in the middle of the playing field. Emerging economies became relevant because of their lower costs and the new possibilities offered by the new telecommunications technologies. A software engineer halfway around the globe from the client could work on a customized service application while the system was down for maintenance overnight. Even better, a team of engineers with different kinds of expertise and located in different parts of the world could now collaborate in real time to offer clients a customized and integrated solution. This momentous change forced existing players to start behaving as if they were companies from emerging economies—or else go into extinction. It was a tough fight because emerging market firms already had their feet on the ground and knew how to exploit their newly acquired opportunity around the world.

No wonder IT outsourcing became the business craze of the day, shifting the boundaries of the corporation, embedding it in global networks, and catapulting some emerging economies like India’s to global celebrity. The corporate world had already seen the outsourcing of blue-collar jobs; now white-collar occupations were also subject to a similar delocalization, driven by the lower costs for expert labor in emerging economies. Companies learned that their value chain could be diced and sliced years before Wall Street started to apply a similar recipe to subprime mortgages.

It was in this primeval soup of rapidly changing technologies, corporations hungry for cost cutting, and large pools of skilled engineers and other experts that Tata Consultancy Systems, Wipro, and Infosys started to make a name for themselves.

Consider the example of Infosys, the second largest of the three in terms of number of employees and the value of IT services exported. It was founded in 1981 by N. R. Narayana Murthy and six engineers in Pune, India, with just $250 of startup capital. The company rapidly moved to Bangalore in search of a more munificent environment for IT services. Step-by-step, Infosys improved its client base, opened an international office in Boston, and started to build a competitive advantage based not only on wage differentials but also on quality. During the 1990s, Infosys realized the importance of providing end-to-end services to its clients instead of accepting jobs involving subsystems of IT. This move implied being able to not just undertake labor-intensive projects but also reengineer entire internal processes of its clients at the least-possible cost. A daunting challenge to be sure for this young, small, and relatively inexperienced Indian firm when compared with the large corporations whose systems it was expected to overhaul, streamline, and optimize.

In order to win customers, Infosys had to make its programmers be available 24/7—close enough to them to understand their needs while still able to match the expertise and efficiency levels of other providers around the world. To meet this challenge, Infosys adopted a self-styled Global Delivery Model that enabled project managers to locate each task exactly where it could be performed most efficiently. The company also managed separately activities that required constant interaction with the client from those that could be undertaken in a “scalable, talent-rich, process driven, technology-based, cost-competitive development centers in countries like India,” according to the founder. “The customer gets better value for money because, in a typical project, only about 20 to 25 percent of the effort is added near the customer in the developed world, and 75 to 80 percent of the value is added from countries like India where the cost of software development is lower.”23

Over the years, Infosys built an infrastructure of 65 offices and 63 development centers in India, the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, China, the Middle East, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Poland, and several other countries. Infosys initially designed this model for software development, then extended it to consulting services more broadly. “We believe that 35 percent of the consulting effort can be done in India, such as proposal preparation, presentation preparation, research, and analytics,” said Murthy. “Similarly, in the case of our business process outsourcing organization, equity research for a major European bank can be done in Bangalore. The bank is getting better value for money, and they’re able to compress the cycle time.”24

In many ways, Infosys offers arbitrage. It helps clients tap into different pools of technical skills and capabilities located around the world and offers their services at the lowest possible price and on a timely basis so that cycle times can be shortened for this era of 24/7 global hyper-competition. “The most important ingredient is talent,” S. D. Shibulal, CEO and managing director of Infosys, told us at the company’s lush, sprawling training campus at Mysore, the largest of 10 facilities in India with capacity to house 14,000 engineers while they undergo training for six months, learning how to get technical jobs done more efficiently.25

On the surface, emerging market IT players like Infosys would seem to have almost unassailable advantages over their developed-market competitors. Their entire ethos, after all, has been built around cost-efficient operations, and they are uniquely positioned to use a large pool of relatively low-priced talent coupled with new digital technologies to offer low-cost solutions to clients located worldwide. So do American and European firms even stand a chance? Yes, if they can forget to some extent their own pedigree. No one offers a better example of that than one of the most pedigree-rich firms in the world: IBM.

Big Blue was a technology powerhouse in many ways. It boasted the invention of the ATM, the hard disk drive, the airline reservation system, and the first computer to defeat a world chess champion, to name but a few breakthroughs. It amassed the largest patent portfolio in the industry, and five of its employees won the Nobel Prize. But during the 1980s the world of technology and computing changed faster than IBM itself. By 1993, the once all-powerful company was on the verge of splitting itself into small pieces, given the poor performance of its personal computer division. Despite enjoying a quasi-monopoly position in mainframe computers and having defined the industry standard for personal computers, the open architecture of the IBM PC and the stubborn escalation of commitment to the OS/2 operating system, which failed at becoming an industry standard, made it impossible for the company to compete with a new generation of fiercely entrepreneurial PC companies.

Desperate for a new direction, shareholders demanded that heads roll. A new CEO, Lou Gerstner, was hired from outside the computer industry. He immediately proposed turning the company into a full-range IT services provider, including software, systems design, and consulting.

Here’s the important point, though: Gerstner didn’t come up with a new strategy drawing on abstract and grandiose ideas. Nothing could be further from the truth. As an outsider, Gerstner immediately realized that IBM was not listening to the customer, was not focused on implementation as opposed to sophisticated products, and was not excelling at execution. His experience in consulting alerted him to the primacy of process and execution. He was also keenly aware of the importance of being customer-centric. Gerstner’s insight was radical because it entailed a revolutionary idea for a company like IBM—namely, paying attention to the customer’s needs on an individualized basis.

Big Blue had grown to dominate the global computer industry by being a technology leader and by setting the standards for both customers and competitors. In other words, it was a company accustomed to imposing its vision, strategy, and products on buyers. Gerstner proposed to listen to customers and to offer each of them an individualized solution to their entire information-processing needs, years after emerging market firms had pioneered the idea.

IBM’s glory days had enabled the company to build a worldwide presence. Its capabilities as a large and integrated multinational corporation were second to none. Gerstner thought IBM could leverage this legacy to help other firms operate globally as effectively and efficiently as his company had in its incarnation as a computer hardware provider. He wanted IBM to help other large corporations make the most of their business operations in the context of the revolutionary changes taking place in the world of information and telecommunications technology. A first important step in realizing the new IBM was to shed divisions that could not contribute to servicing customers by meeting their IT needs. This process of refocusing around software and services initiated by Gerstner eventually led IBM to dispose of the PC business, which was sold to China’s Lenovo in 2004 shortly after his departure as CEO. Simultaneously, Gerstner acquired companies to fill in the gaps in IBM’s capabilities, including Lotus and Price Waterhouse Coopers’ consulting business.

Implementing Gerstner’s customer-centric view of the company was far from easy. For a company accustomed for decades to enjoying a monopoly position in the market, adopting a strategy of providing ad hoc integrated solutions for clients required a major turnaround, large-scale mental and behavioral change, and sustained attention to execution. In his memoir, Gerstner wrote that “fixing IBM was all about execution. We had to stop looking for people to blame, stop tweaking the internal structure and systems. I wanted no excuses. I wanted no long-term projects that people could wait for that would somehow produce a magic turnaround. I wanted—IBM needed—an enormous sense of urgency.”26

The turnaround IBM began under Gerstner is even more remarkable when you look at how its one-time competitors in the computer hardware business have coped with their own diminishing futures. HP, for instance, acquired Compaq in a huge and ultimately failed bet for reviving its presence in the hardware industry. Despite the vast amount of resources pooled in the wake of the HP-Compaq merger, the company was still unable to be as innovative as Apple has been. After years of decline, HP is finally getting out of the business of making computers and trying to gravitate toward IT services. To ease the transition, HP paid astronomical premiums to acquire consulting and software firms such as EDS and Autonomy to make up for lost time, but even that might not be enough. When you’re caught in quicksand, thrashing around just makes you sink faster.

IBM could have continued acting like the large, established company that it was, buying and selling businesses hoping that some combination would eventually stick—exactly the strategy HP was eventually forced to pursue. Instead, Gerstner asked his managers to behave like Infosys and other emerging market competitors—like firms, that is, with no other option but to excel at execution. But you can push the emerging market analogy only so far.

After all, IBM already had a global presence and all those Nobel laureates. Infosys had to build its reputation as a global IT services provider from scratch so that it could overcome the natural, initial reluctance of clients to outsource noncore but critical IT activities to an unknown company whose headquarters was thousands of miles away. Clients needed to know that the company was not only technically competent but also trustworthy. That required executing in a different but equally critical way—in building values and reputation.

“I think if you ask me what distinguishes Infosys from many other companies, it is the following: We have a very strong value system,” argued Murthy. “In fact, when I address new hires, the main thing I talk to them about is the value system. I tell them that even in the toughest competitive situation, they must never talk ill of customers. For heaven’s sake, don’t short change anybody. Never ever violate any law of the land.”27

Here, too, attention to detail has clearly paid off because Infosys is widely admired today for its corporate governance practices and its reputation for honoring its commitments to clients.

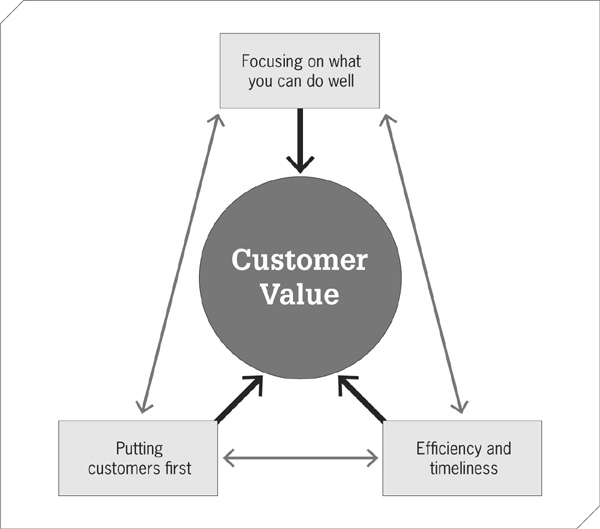

The first business message from emerging markets is loud and clear: stellar execution pays off, whether the industry is a traditional one like baking or is all about high-tech gadgetry like aircraft. As depicted in Figure 1, good execution begins with focusing on what you can do well, putting the customer first, attaining world-class efficiency in your operations, and delivering to the customer on a timely basis. Once you learn how to execute well, then you can develop, adapt, or upgrade strategy on the fly, incorporating what you’ve learned through execution—and proceed to execute again. But by all means, do not strategize without building a strong execution foundation first.

FIGURE 1

Execution leads to customer value.

The paired examples of IBM and Infosys, Bombardier and Embraer, and Sara Lee and Bimbo illustrate that a great strategy is not enough, and that too much strategizing without attention to execution can wreck a company. Indeed, oftentimes, the best strategies emerge from execution: How can you possibly identify what will work without first seeing it work? Execution is one of the most significant business challenges of our time, especially when so many companies from emerging markets are taking over the world with disarmingly straightforward strategies and simple recipes to achieve success.

Eike Batista, the founder of EBX, the world’s fastest-growing mining and energy group, likes to say that X stands for both execution and for multiplying shareholder returns. He likes to remind everyone that he is an engineer, and that execution is what has enabled him to become the world’s seventh-wealthiest person.28 “Execution is really the critical part of a successful strategy,” Gerstner wrote in his memoir. “Getting it done, getting it done right, getting it done better than the next person is far more important than dreaming up new visions of the future.”29 Amen.