CHAPTER 4

Political Strategies for Degrowth

In the early 2020s the international movement faces key political questions around the distinction of degrowth as a discrete movement, its political role and what that means in terms of political strategies for its future. Is it a problem that degrowth seems to have been more widely influential – rather than narrowly unique and crucial – within the plethora of movements and campaigns burgeoning this century? If so, can one conclude that degrowth’s main role is simply to form a campaign, that is, to provide a solid critique of ‘growthism’ whether in capitalism or productivist market socialism? Alternatively, might degrowth strategically align with ecosocialist and post-capitalist visions, as a leading movement offering clear ways forward in our uncertain future?

In a generic sense, there are streams within degrowth with distinctive views on how the movement ought to organise internally and promote itself politically. Horizontalist, direct democracy and grassroots power-sharing streams are influenced by anarchism and gender politics. They conflict with more formal policy-oriented streams bent on proposals that might be considered seriously within contemporary political and policy discourses, by government bureaucrats and politicians. While some focus on novel disruptive models of marketplace enterprises, say, using digital peer-to-peer networking, others regard formal engagement and debate within mainstream and heterodox economics as crucial. Such distinctions become sharper when attempts are made to cohere around degrowth imaginaries, form degrowth agendas and take transformative steps forward.

How might the movement best articulate pragmatic strategies of ‘doing’, experimenting and prefiguring a degrowth society, engaging with parliamentary representation, collaborating with the union movement, and crucial non-violent direct resistance in terms of rapacious capitalist growth? Ultimately, matters of internal organisation and external relations are two sides of the same coin and essentially political. Deepening the analysis in chapter 3, this chapter on political philosophy and strategy lays the groundwork for debates on the degrowth agenda, the ‘degrowth project’, which is the focus of chapter 5.

ON INFLUENCE AND LEADERSHIP

In Lyon (France), three years after the launch of the slogan ‘degrowth’ and the enthusiastic campaigns around it, a general state of the movement (Etats Généraux de la Décroissance) meeting was organised in March 2005. More than 400 people joined the debate on how to organise the evolving degrowth movement. At this stage it seemed logical to follow the classic way, that is, organising a central structure, which would become both a platform and contact point for those within and outside degrowth. Yet this approach proved to be the first of a long series of failed attempts to formalise degrowth in conventional ways.

The degrowth movement is not readily organised using traditional forms. If degrowth has proved an explosive slogan in mainstream society, so too attempts to centralise its political structure have regularly led to fireworks, with horizontalism and autonomy winning out. This happened a few months after the general state of the movement meeting in France with the creation, and demise, of the Degrowth Party (already mentioned in chapter 3). The same stories can be told of developments in Italy and Belgium. Even if very influential, attracting large numbers of advocates and adherents, many practitioners, a lot of media and scholarly attention, degrowth has failed to materialise as a large mass movement in, of and for itself.

However, Paul Ariès has cautioned the degrowth movement about focusing on its own growth, saying it risks ending up like the frog in the Aesop fable that, in trying to prove it could be as big as an ox, burst.1 In his popular talks Ariès often reminds the movement that, as long as degrowth ideas are spreading, then activists ought to be satisfied and simply proud of that influence, that they should not worry about not being able to point to a singular organisation and central headquarters for degrowth. In fact, as critics of the mainstream system and its dominating power structures, the degrowth movement needs to be careful not to reproduce the mistakes of capitalism’s violent and arrogant domination, for instance by adopting its institutional forms. At the same time, creating some kind of appropriate and coherent form of organisation for the degrowth movement is necessary.

So, how might activists within the degrowth movement co-create such a structure, and shared processes that are genuinely effective and not counter-productive? How can the right balance be found between, on the one hand, being visible and impactful in the so-called real world yet, on the other hand, avoiding the risks of negatively centralising power within, and as, a movement? To be sure, the degrowth movement cannot solve contemporary political challenges using the same political tools and thinking that created the growth demise but, what are the alternatives?

The degrowth movement is not alone in facing these questions – they exist for all contemporary, emancipatory and emerging movements, from international anarchist movements to worldwide Occupy movements, from los indignados (M-15) in Spain to the French yellow vests (aka ‘yellow jackets’), from the ZAD (Zone à Défendre) to Extinction Rebellion.

Change the world without taking power

After facing several tough organisational failures, the French degrowth movement consciously decided to ‘own’ its apparently disorganised nature and use it as a strong point for reflection. The movement focused on questioning a conventional sense of ‘power’ and how power manifests itself in various social and economic situations. Work on the concept and practice of ‘autonomy’ by authors such as Cornelius Castoriadis (1991) and John Holloway’s Change the World without Taking Power (2010) has played an important role in degrowth activists’ thinking.2 In particular, Holloway’s definitions of power as ‘power over’ and ‘power to’ encouraged those who experienced the state of the degrowth movement as a ‘failure’ to acknowledge the very real negatives of being successful in gaining power in conventional number-busting and leadership ways, that is, of wanting to have and exert power over others.

The vast majority of the degrowth movement feels freer and more confident in experimenting with a decentralised and horizontal network of small collectives and projects. These approaches are effective in creating power to, and avoid the destructive centralisation of power where all the movement’s energy and effort is absorbed by gaining and maintaining power over. However, we still struggle, say, particularly with organising international degrowth conferences and associated media, to decide on common communication tools and questions around endorsing and formalising representatives for the movement. These challenges are always heightened in conventional everyday contexts where media, politicians and potential members of the movement ask us about contact points and sources for communications.

A DECENTRALISED HORIZONTAL NETWORK

The conscious decision to avoid conventional hierarchical power games must not mean abandoning power. The movement’s perceptions and practices of power exist within a socio-political context that resists radical anti-systemic ideas such as degrowth. The movement exists to make a point and create socio-political change. Therefore, a balance has to be continuously negotiated between, on the one hand, the necessity to act within the system at the same time as, on the other hand, acting ‘outside’ and against the system.

Compromising too much ends in co-option, reappropriation or falling into a plethora of other counter-productive traps. Yet being purist, fundamentalist or intransigent has dangers too. For instance, if considered solely from a mainstream perspective, it would be very convenient for capitalist forces to isolate degrowth into weak and small, apparently irrelevant, islands of radicalism. Therefore, the movement needs to engage in mainstream society in very strategic and self-aware ways. Correcting misconceptions of the movement need not be defensive acts but, rather, present opportunities for activists to explain the real meanings of degrowth and how degrowth is practised.

Fatal compromises have been made by other actors wanting greater influence. For instance, some large non-government organisations accepted funding from corporations only to find their activities compromised as a result. Moreover, certain green parties hell-bent on political power pushed representatives into government who, in fact, proved to be without sufficient skills, numbers or space to enact systemic change. Similarly, individualistic, narcissistic and purist actions – exhibited in certain types of survivalism where people focus on self-sufficiency and on building bunkers and accumulating stores to sit out an emergency – typically end up isolated. Such approaches oppose the degrowth spirit of mutual solidarity and support, of caring and collective sufficiency.

Ever since degrowth emerged, members of the movement have consciously walked a tightrope, sometimes engaging within the mainstream system, at other times existing outside it. Although not conventionally organised, the degrowth movement does have a clear organisational form as an open, decentralised and horizontal network. The movement aims to be free of the power-over strategies that conventional structures facilitate. On the one hand, members are offered experiential freedom to engage with and be accepted within the system so that they are listened to, have visibility and have a real-life influence. On the other hand, members are also free to engage in anti-power ways.

The movement maintains a culture that values freedom of speech and engagement in discourses over various differences. The movement finely balances being radical – through comprehensive root-and-branch anti-systemic critiques and experimenting with alternatives for broad-scale change – while avoiding extremism. Instead, the movement as a whole entertains and engages in both revolutionary and reformist tactics.

CULTURAL HEGEMONY AND CRITICAL MASS STRATEGY

Radical critiques of both failed revolutions and reformist strategies point out that it is not enough to simply seize and assume state power. The degrowth movement has integrated the Italian intellectual and politician Antonio Gramcsi’s concept of ‘cultural hegemony’ into its strategic thinking.3 Indeed, a main challenge for the degrowth movement is to radically influence society in cultural ways. Here the multi-pronged approach of applying the wisdom of that set of thoughts undergirding degrowth (chapter 2) through articulated spheres of action (chapter 3), plays a central role in decolonising the dominating capitalist imaginary – opening up people’s consciousness to the possibility of creating an alternative world. Being active in the world makes degrowth real, enables fruitful conversations with observers and critics, and offers ways to integrate new members into the degrowth network (Figure 4.1).

The main goal of degrowth and related movements is to hypothesise, experiment with and co-create the conditions for change that ultimately leads to a critical mass supporting postgrowth. The main goal is not to take power and exert power over because that runs a serious risk of the movement becoming a self-interested servant of its own power. The aim, instead, is to influence, engage with and incorporate, sufficient numbers of people to radically transform society. This is how the movement can change the world, neither by taking power nor by abandoning power to the reigning political and economic elites.

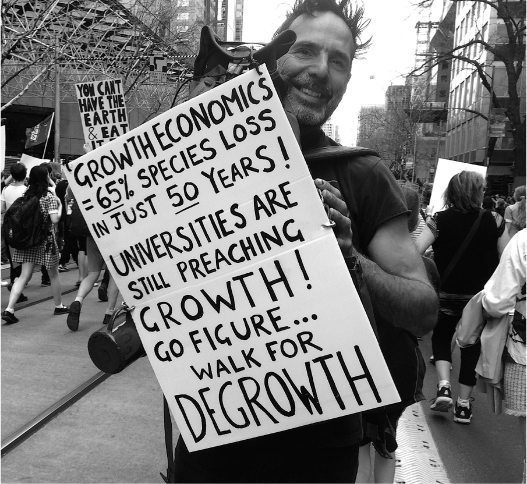

Figure 4.1 Activist Patrick Jones at a climate change rally, Melbourne 2019

Photographer: Meg Ulman (Australia)

The authoritarian temptation

In analysing failures of utopian political thinking in the past, degrowth activists have identified a pitfall in the temptation to become authoritarian. Indeed, environmentalists occasionally express the fear that degrowth could develop into a type of eco-fascism. However, ever since it began, the degrowth movement has very clearly and openly distanced itself from such tendencies: ‘Degrowth is democratic or it doesn’t exist.’ Experience has clearly shown that happiness cannot be imposed from the top down. Here the case of Thomas Sankara, who could be considered a pioneer of degrowth, is enlightening. In a popularly supported coup d’état in 1983, Sankara seized power over the French colonial Republic of Upper Volta state. He renamed his landlocked country in West Africa ‘Burkina Faso’, which translates as Land of Incorruptible People.

Sankara immediately implemented anti-capitalist, anti-imperialistic, ecological, feminist and emancipatory reforms, many in line with a degrowth political agenda. He forbade female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy, appointed women to high governmental positions, and implemented educational and social programmes. Sankara supported agroecology techniques for reversing desertification, engaging in this effort French degrowth pioneer Pierre Rabhi. Rabhi later tried to run for the 2002 presidential election in France under the banner of degrowth. The country became self-sufficient in food within four years of Sankara assuming power. Lost in history is his inspiring speech to the Organisation of African Unity Summit in Addis Ababa in 1987 (a few months before his assassination) when he raged against the country’s odious debt:

Under its current form, i.e. imperialism-controlled, debt is a cleverly managed re-conquest of Africa, aiming at subjugating its growth and development through foreign rules. Thus, each one of us becomes the financial slave, which is to say a true slave.4

Sankara was, and still is, an inspiring visionary. But alone he was unable to culturally transform his society, as indicated in the following symbolic anecdote.

Sankara wanted his people to be autonomous and to feel proud of their culture, so he instructed public employees to wear traditional tunics woven from Burkinabé cotton and sewn by Burkinabé craftspeople. But, soon afterwards, he noticed that the public servants had not abided by his request. He ordered impromptu checks throughout his ministries and punished those who didn’t wear traditional local clothing. In fact, under such duress, most staff members kept buying and wearing western clothes but each hid a traditional faso dan fani in their office to quickly put on, if they were subjected to a check.

One could make a class analysis here, or any number of other observations, but the salient fact is that the office workers had not culturally appropriated Sankara’s great idea. Advanced in a hierarchical top-down way, his progressive reform failed. The authoritarian approach is a recipe for disaster. This is a clear case where an engaged, consciousness-raising and voluntary process driven by a decentralised, grassroots movement is likely to be more successful.

THE STRATEGY OF THE SNAIL

If a top-down approach is tempting, that is partly because we desire urgent, indeed immediate, change in order to face our massive climate, and biodiversity, emergency. This makes us prone to anxiously rush into transforming society as quickly as we can. However, the degrowth movement’s response to the urgency of our conjunctural crises is to slow down, that is, ‘to make haste slowly’. This strategy has evolved as such for two reasons.

First, even if it sounds counter-intuitive, we have learnt this approach from people dealing with catastrophes. Rescue workers and firefighters focus on a pre-prepared and methodical step-by-step approach so that they can glean all the significant relevant factors before acting appropriately in response to the emergency they face. These disaster professionals offer a model to the degrowth movement, which makes it less likely that we add to the chaos but rather, using intentional and deliberative processes, make haste slowly.

The main challenge for the degrowth movement is the temptation to follow the system’s destructive and sterile rhythms. Instead, the response of the degrowth movement follows along the lines of the characters in the 1973 film L’An 01 (The Year 01). The characters very consciously decided to come to a collective halt. Then, slowly, they reintegrate only those activities that prove absolutely necessary. Directed by Jacques Doillon, Alain Resnais and Jean Rouch, the film’s message is ‘Let’s stop everything, and think about it: we’re not sad!’ (‘On arrête tout, on réfléchit et c’est pas triste.’)

Therefore, in the degrowth movement’s Platform for Convergence proposed by attendees of a gathering in 19 September 2009 (see Appendix 1), we find the following statement:

In contrast with the classical strategy of taking power as a prerequisite to any change, we propose a radical and coherent idea: The Strategy of the Snail.

… the Strategy of the Snail implies that it is an illusion that acceding to power – whether in a reformative or revolutionary manner – is a prerequisite for changing the world. We do not want to ‘seize power’ but to act against the dominant structures and ideas by weakening their various powers and to create, without delay, conditions which will enable us to give full meaning to our lives.5

In this platform, the degrowth movement made a very clear statement of revolutionary transformation, so no-one need be anxious that a ‘snail’s pace’ would mean any less radical change. An intention stated further down in the platform, which is reproduced in Appendix 1, is to make ‘an immediate exit from capitalism’. Indeed, this aim leads on to our second reason for adopting a strategy of slowness.

In a modern society of spectacle, disruption and novelty – where there is massive social pressure to ‘click’, ‘like’ and ‘retweet’ – the strategy of stepping aside from immediate action and reaction definitely seems to risk the degrowth movement being written off. Nevertheless, for strategic reasons, degrowth activists believe that a carefully planned qualitative transformation will, ultimately, be the most effective way to successfully slow society down. The key dynamic behind growth is the money-makingmore-money dynamic central to capitalist economies and societies. In this dynamic, where money seems intertwined with time, and time with money, there is an unstoppable urge to speed everything up. Thus, the decision to slow down is a qualitative counter-systemic strategy essential within the degrowth transitionary process. Slowing is, to some extent, qualitatively and quantitatively commensurate with degrowing.

Indeed, each of the strategies formed to progress degrowth must be read in multidimensional and contextual ways to gain a deep understanding of their authentic meaning. The strategy of slow conveys the message that, when faced with great challenges, being still and reflecting can save time otherwise wasted by acting impetuously on an inaccurate analysis leading to inappropriate action. At the same time, slow is clearly anti-systemic, which is sufficient reason for the strategy to be necessary and effective.

A STRATEGY OF NON-VIOLENCE

The question of whether to be, or not to be, violent has returned to the centre of current debates, given the frightening acceleration of climate change, and biodiversity loss, and the inability of current global capitalism to enact significant change. Questions around whether to act violently or not, and how to define precisely what acts are, or are not, ‘violent’, have been at the heart of debates on strategy by occupiers of the area planned for a mega-airport, la Zone à Défendre in the fields of Notre-Dame-des-Landes, north of Nantes (France), as described in chapter 3, a site of resistance for decades. Similarly, such questions arise constantly in movements like Extinction Rebellion, which is international, and with national uprisings such as the yellow vest movement in France.

The degrowth movement reflects on past actions and tries to learn lessons from cases regardless of their success or failure. The central questions raised with respect to violence often rotate around how best to be radical, how to avoid an extremist response and how to find the most effective strategies. A key risk of acting violently, while at the same time criticising the violence of the system that the movement opposes, is to find that public support quickly withers once the struggle turns violent.

Perhaps the right balance is found, instead, through determined, subtle and smart strategies? The degrowth movement is clear about rejecting any kind of violence, just as it is clear about rejecting any kind of authoritarianism. But here we need to define what we mean by ‘violence’. Civil disobedience, direct action, sabotage, blockades, attacks against corporate symbolic property (say destroying a repulsive advertisement) are non-violent defences or mere provocations – if cleverly and collectively implemented – in order to open political debate, and as long as no-one is injured.

We have compassion for the despair protesters feel in a street demonstration that might compel them to attack the police or a bank as a veritable form of defence because the system of law and order and the financial system procedurally act as forces against them. Moreover, we simply don’t live in the appropriate conditions for a dispassionate and solutions-oriented debate. Violence exists systemically, and systematically, within the capitalist societies in which we live. Historically violence has been an everyday tool of dominance, first to repress; second, to discredit movements; third, as a pretext to repress and isolate even more violently through injury, death and imprisonment. Thus, the circumstances in which people act, the societal powers people oppose, are already characterised by violence in terms of limitations imposed by police and police force and potential use of the military.

Within repressive environments such violence is readily accepted and the mere threat of violence is enough to discipline people not to challenge the status quo. Thus violence can emerge quickly, sometimes as the only form of defence. Even if an activist movement is not initially violent, if it is anti-capitalist, forces in the dominant system readily feel justified in provoking protesters associated with such movements. Therefore, the degrowth movement stands with a strategy of non-violence, also preferring non-violent communication strategies, so that we can genuinely claim that, if violence occurs, the dominant system will be the guilty party.

This question on degrowth positions with respect to violence and non-violence is framed by more general questions about how the movement can be radical, and tackle problems at their roots, without falling into counter-productive extremism.

TO BE RIGHT WHEN ONE IS ALONE, IS TO BE WRONG

More than ever, it seems, people exist within bubbles of ‘truth’, reinforced by social media provided ‘free’ to optimise advertising opportunities and money-making. Social media data and algorithms feed people’s habits and preferences so that they see what they want to see and read news that contains messages that they are already likely to favour. People tend to develop a bubble of friends with whom they feel comfortable so that they are not challenged to grow, to be tolerant or to change. People existing in these conditions rarely meet others who disagree with them and thus easily dismiss them if they do. Degrowth advocates are challenged by this classic condition of alienation and respond with strategies of listening to, and engaging with, people whose imaginaries, ways of life and sets of values radically differ from their own. Such people are potential allies of degrowth. They help advocates understand better what capitalism is, and feels like, and help them to form and revise ideas about what degrowth might become. This strategy challenges everyone in the movement and prevents them from forming and living in a degrowth bubble of comforting ideas and people.

One might well ask whether this concept of people having a strong tendency to live in bubbles is really how they experience reality. Polls and voting associated with Brexit (Britain withdrawing from the EU), US President Donald Trump, the French right-wing populist and nationalist politician and lawyer Marine Le Pen, and Hungary’s ‘de facto supreme leader’ Prime Minister Viktor Orban certainly suggest that this is the case. This state of affairs is also illustrated by the extent of mass media advertising and customised news and social networks both revealing and developing cultural and symbolic divisions in society. These online tools might be considered mass destruction weapons for democracy and dialogue, stretching across divisions that seem to become more entrenched along with rising economic gaps and deepening political divisions. Consequently, many feel more comfortable and compelled to travel by air to another part of the world than they do to get on a bike, or travel in a public bus, in their neighbourhoods where they live.

The degrowth movement needs to be skilful and find bridges to connect with people in cultures which may look and feel irreconcilable to degrowth advocates and activists but with whom we might find, or forge, a lot in common. Shared interests can often be found underneath the jargon used by both sides, and by discovering a common language to identify our commonalities. As examples of forging common ground, let’s take the yellow vest movement and the question of bike use in Hungary.

Yellow vest movement

The yellow vest movement arose in October 2018, sparked by a government-planned so-called ecological tax on petrol, which threatened to raise fuel prices. The French state had underestimated the financial pressure that such a hike in fuel prices would put on those on a low income – especially those in rural areas – whose daily work and social life depends on using vehicles. Thus the yellow vest movement arose, organising numerous petitions circulated through mass social media, and started to block roundabouts all over France.

Apparently denouncing what was presented as a transitional reform to reduce greenhouse gases and oil dependency, the yellow vest movement was initially mocked, even demonised, by a large swathe of ‘more educated’ French, who typically lived in urban areas. But the protesters quickly fraternised and politicised their movement to avoid the trap set by Macron’s government to push them toward the far right, where they would be contained and isolated. Throughout 2019, the yellow vests emerged as a movement for social and environmental justice, clearly illustrating the point already appreciated by those in the degrowth movement that there can’t be an ecological transition without simultaneously improving social equity.6

From a rebellion against a discrete plan to raise taxes on petrol, proposals emerged from the yellow vest movement to prevent tax evasion by the rich, to set a maximum income, to tax aeroplanes and to redevelop regional train networks. As it happened, such top-down approaches from the yellow vests, that would so clearly rely on regulation and imposed constraints without either consultation or consent, were violently rejected within the broader movement, and were thus ineffective. But degrowth activists connected with the yellow vest movement to engage in dialogue and apply deliberative processes with more direct forms of democracy, respect and consideration. Advocating for these kinds of processes seems to have enhanced parallel political agendas with potentially much broader support and greater chances for success.

Contradictions in context: Hungarian bike cultures

We learnt similar lessons from the existence of dual bike cultures in Hungary, a country that boasts the third highest bike use in Europe after Denmark and the Netherlands. Hungary is unique because it has two radically different bike cultures: one urban and one rural; one chosen and enjoyed, one forced and painfully endured.

Critical Mass and later the I Bike BP movement both strengthened and made more visible the bike culture in Budapest and other large cities of Hungary. It has even become trendy to have a nice bike and ride up and down the city! People choose it, it improves their quality of life, health and happiness, and creates a sense of autonomy, pride and self-satisfaction. But, in rural areas where bikes are used more frequently than in cities, bike riding is commonly considered humiliating. You use a bike because you don’t have enough money to buy a car and pay for the petrol that a car needs in order to be used.

Both urban and rural practices of bike riding align with an environmentally friendly political agenda for transport. But, the personal experience of bike riding can be very different, with enthusiasm and enjoyment of life at one end of the spectrum, and humiliation and frustration at the other end. When you consciously decide to get rid of your car and use a bike, you very rarely return to regular car use because your bike has become a very convivial tool in your life. On the contrary, when riding a bike is imposed as a form of austerity or thrift, as soon as you get the opportunity to get a car, you buy one. Advertising suggests that a car is more convenient and easy to use than is often the case and, humiliatingly, suggests that if you don’t have a car, ‘you are a loser without status’.

Here, again, we see the importance of constructing a positive and emancipatory narrative to contribute to a new cultural hegemony around convivial and freely chosen degrowth. Neither economic nor political force works. The degrowth movement accepts that matters of social justice need to go hand in hand with sustainability measures for one planet footprints to become attractive, and even feasible, for many people.

This is where the concept, practice and experience of ‘open relocalisation’ becomes relevant.

OPEN RELOCALISATION

Degrowth is about localising production and consumption, which often means ‘relocalising’ in practice. It is clearly desirable in ecological terms to minimise the transport of people, goods and services. It is totally absurd to have to travel to shop for goods and services that could be produced and consumed locally. It is equally wasteful to transport numerous products from a variety of places if they could be produced locally.

More significantly, relocalisation helps to break through some of the obscurity and illusions endemic to consuming goods and services that have been produced far away. When you go to a supermarket you often have to buy products without any clear understanding of how they were made. You do not know whether or not, or to what extent and in what ways, their production exploited ecological systems, say by using materials and non-renewable energy. The labels do not provide information about the conditions under which the people making them worked and were paid. This is not a moralistic statement but an alarming observation of the depth of secrecy in a private and competitive system of production for trade.

To relocalise production enables us to know how the things we consume have been sourced in terms of their materials, labour and energy use. Otherwise we are at risk of becoming a victim of being evil without directly doing evil – in the sense of Hannah Arendt’s notion of the ‘banality of evil’ – of living in a false consciousness that all is well with the world.7 The point is simple: Would anyone buy certain clothes, carpets or shoes if they had been able to observe the working conditions of the mere children who produced them? Would you consume a food product if you were aware of the specific mistreatment of animals that were involved with bringing it to your plate? Would you leave electric lights or appliances on longer than necessary if either the oil refinery or the rare earth mine for the so-called renewable electricity system that supplied your electricity was located in your neighbourhood or local region? Local production enables us to gain greater knowledge and real freedom to choose exactly what we buy.

In contrast to either top-down regulation or the free market perpetuation of unfair practices exploiting people and planet, a degrowth political strategy and vision focuses on radically transforming production, consumption and associated financial and commercial practices. In chapter 3 we discussed cooperative forms of working and communal distribution already being implemented by certain degrowth advocates, for instance through community supported agriculture and cooperatively organised housing, workshops and repair centres.8 Such forms of self-governing production and distribution enable greater transparency and responsible decision-making over material inputs and waste, equipment and working conditions. Generalised, they would mean that we could make genuine choices to purchase ethically produced goods and services.

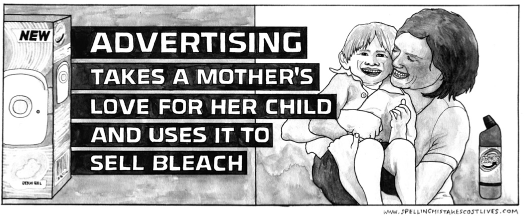

Yet degrowth-oriented regulations would be useful in certain circumstances. The power of advertising is widely accepted, for instance, bans of tobacco cigarette advertising have been introduced in many countries the world over. Regulating – even democratically elected bans on – advertising might be a very effective degrowth measure. The impacts of advertising are notoriously subtle and advertising contributes to cultures of growth by integrating a person’s sense of identity with consumerism (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Advertising

Artist: Darren Cullen (UK)

Should we permit sport utility vehicles (SUVs) in cities where it is absurd, wasteful, unnecessary and environmentally destructive for a few tons of metal to use so much road and parking space just to move one or two humans (each around 65 kg) at an average speed that ends up comparable with cycling or travelling in a horse-drawn carriage?9 Similarly, isn’t it wasteful and inhumane to use petrol that is only supplied to us due to our governments having standing armies or supporting militaries where that oil has been sourced and refined? To curtail such practices, especially initially, top-down regulations could be used. Pete Seeger celebrated the City of Berkeley’s Zero Waste Commission in his ‘If it can’t be reduced’ song, where he went several steps further (see Figure 4.3).

However, taking a constructive approach, once degrowth was established, open relocalisation using degrowth forms of production would enable us to re-evaluate our basic needs, practices, production and consumption while understanding the real human and environmental costs of purchases and facilitate us in consciously making enlightened choices. We will continue this discussion of open relocalisation in terms of practical proposals in chapter 5.

Figure 4.3 Pete Seeger – ‘If it can’t be reduced…’

Source: Twitter shared image, 2019

A SILENT TRANSFORMATION OF SOCIETY?

In February 2016, the left-wing French monthly Politis decided to produce a special edition assessing the impact of the degrowth movement. Politis interviewed most of the key French degrowth actors, asking them why such a relevant idea, that had attracted so much passion initially, appeared to have lost its appeal. The journalists focused on why degrowth had failed to maintain its originally spectacular visibility and to establish any clear and mainstream organisational form. However, as this investigative line raised further questions, a new narrative formed: perhaps what was really happening was an invisible underground revolution?

Ultimately, the Politis special edition appeared with the title ‘Degrowth: A Silent Revolution’.10 In short, the initial line of investigation was turned upside down or, better, right side up. The inquiry ended up revolving around the extent to which degrowth and associated movements had influenced political debates, so that even though ‘degrowth’ had not been absorbed as mainstream, it seemed that it was no longer a provocative idea. Perhaps degrowth did not need to become organised because its campaign was already obsolete?

Yet, if degrowth had become less controversial and more culturally tolerable, was it more politically acceptable? If degrowth was startling and attracted the limelight when it publicly emerged in the early 2000s, had the main point and ideas of the movement simply become clearer and begun to be seen as more rational over the last two decades, especially given the context of the global financial crisis, the increasing environmental crises, and debates on sustainability and climate change? Or, perhaps it was the strong critique of growth that degrowth advocates had managed to convey, or that was now easier to comprehend, rather than the constructive principles of a degrowth project, a degrowth future, that had become acceptable?

Although there is more than a grain of truth in the argument of a silent revolution, the argument needs to be muted because a genuine degrowth society is so far from being realised. Certainly, visible transformative steps have taken place in terms of consciousness, as confirmed by several public opinion polls. Surveys released in Europe in the autumn of 2019 showed that, with respect to utopias capable of addressing twenty-first-century challenges, it was the degrowth utopia that had most support from French people. First, in October 2019, Odoxa published a survey initiated by mainstream institutions – the British multinational insurance company Aviva, an economic weekly Challenge and the news media company BFMTV/Paris – to reveal that 54 per cent of French people surveyed supported degrowth, compared with just 45 per cent supporting ‘green growth’.11

Second, in November 2019, the Observatoire Société et Consommation (aka ‘Obsoco’ or Society and Consumption Observatory) – with the support of the public environment and energy agency Agence de l’Environnement et de la Maîtrise de l’Énergie, the public investment bank Banque Publique d’Investissement (Bpifrance) and the E. Leclerc Chair in Future of Retail in Society 4.0 at the ESCP European Business School – invited those that they had surveyed to choose between three ‘utopias’. In response, 55 per cent supported degrowth, 29 per cent preferred a security-styled utopia with top-down management of ecological impacts (in reality a type of eco-fascism) and just 16 per cent chose a techno-liberal utopia offering innovative transhumanism, green solutions and technologies within a liberal economy. In Le Monde, the Professor of Economy and co-founder of Obsoco Serge Moati concluded that, to a large extent, the idea of degrowth had been liberated from its negative images and associations, at least in France.12

Is there any evidence of similar changes of heart taking place in any other parts of the Western world exposed to degrowth ideas and practices? In 2016, Obsoco published the results of a similar survey that had been conducted in Italy, Spain and Germany, as well as France. Those results already showed such tendencies: 47 per cent for degrowth, 36 per cent for a ‘collaborative economy’ (based on digital platforms where users and providers engage in peer-to-peer transactions in activities such as car and accommodation sharing, time-banking and crowd funding) and only 17 per cent for transhumanism.13

Cultural changes are visible in trends associated with eating habits, such as eating less meat and eating more local, seasonal and organic food; avoiding flying; reusing, repairing and sharing; and becoming cyclists and walking more. We observe the success of books and films about local initiatives, such as the 2015 film Demain (Tomorrow), screened in French cinemas to more than 1 million people and translated into more than 20 languages.14 This documentary shows how a new world driven by local citizen initiatives, like local currencies and alternative educational practices, is already under way.

These trends are related to other factors. First, even if denial persists at some level, there is much greater awareness of environmental challenges, especially climate change, loss of biodiversity and species extinction. The most recent reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) are alarming enough, but more regular, extreme, intensive and prolonged climatic phenomena are making the crisis visible through events such as highly destructive and fatal bushfires and tornados.15

More debate on the limits of a neoliberal economy has arisen as a result of the 2007–8 global financial crisis and its consequences; the scandals around tax evasion revealed in the 2014 Luxembourg Leaks and the massive 2016 leak of documents known as the Panama Papers; the rising inequalities highlighted by Thomas Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2017); and the social movements in Latin America, Europe, the Middle East and beyond, struggling for greater social justice. Last but not least, in the 2010s, we have observed an increasing number of radical critics developing novel concepts – already referred to in previous chapters – of the precariat and of bullshit jobs, concepts formed from unequivocal evidence of suffering due to abysmal or senseless working conditions.

A PEDAGOGY OF CATASTROPHES OR THE SHOCK DOCTRINE?

Naomi Klein’s book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (2007) describes how the neoliberal political agenda might deepen the catastrophes that our societies face by implementing even more exploitative reforms. Klein’s ‘shock doctrine’ refers to situations where crises and catastrophes mainly bolster the neoliberal political agenda, thanks to its cultural hegemony and dominant media capacities. Recent examples include the phenomena of French president Emmanuel Macron (2017–), Marine Le Pen (president of the National Rally (2011–) and presidential candidate in both the 2012 and 2017 presidential elections), Boris Johnson and the ‘success’ of Brexit, and Donald Trump’s headline-grabbing one-liners in his term in the White House, 2017–20. Yet French philosopher Jean-Pierre Dupuy’s 2004 book Pour un Catastrophisme Éclairé: Quand l’Impossible est Certain (For an Enlightened Catastrophism: When the Impossible is Uncertain) speculates on how upcoming shocks and even catastrophes might offer ‘opportunities’ for social change agents to enact new realities.

Significantly, the terrifying increase of natural disasters of record proportions worldwide seems to have impacted more on popular debates on climate change and a preparedness to engage with serious imaginaries for our future than the increasingly detailed and alarming scientific works and recommendations that have appeared in the last decade. Observing the silent transformation under way, we can see these developments as offering pedagogical opportunities and possibilities for radical changes. Here, the strategic challenge for the degrowth movement is to become adroit at engaging in, and with, such cultural and political conditions – to develop a veritable pedagogy of constructive responses to catastrophe and to resist more ‘shock therapy’ from the state.

STRATEGIC READINESS: THE DEGROWTH AGENDA

With the undoubted rise in social consciousness, and with the severity of conditions that require action, writing in 2020 we find reason for hope. Unfortunately, at the same time, the global acceleration of both environmental destruction and socio-political and economic inequalities is depressing. As a planetary species, humans are still edging towards the precipice. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock has just been set to 100 seconds to midnight.16 Capitalism continues its violent exploitation of people and planet. We face the collapse of thermo-industrial ‘civilisation’. Yet, attendant anxieties create more profitable avenues for manipulative and demagogic political agendas.

So, where to for degrowth? What items are on our political agenda? These questions, and more, are the focus of the following chapter. What does our ideal platform look like? What strategies do we need to address the main psychological and political barriers to adopting degrowth? As cultural support for degrowth grows, what are the necessary and optimal conditions to realise a degrowth model of post-capitalism?