CHAPTER 6

SAVING “THE REMNANT”

“This question of Armenian relief is one which excites a great deal of feeling.”

– Lord Robert Cecil, Eastern Committee Meeting, British Foreign Office, December 9, 1918

Promises by those who signed war declarations in August, 1914 that the conflict would be over by Christmas proved impossible to keep. By spring 1915 when the Armenian massacres broke out, the war already had the makings of a protracted struggle that relentlessly drew in military personnel and civilian populations across Europe, Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Britons were told to prepare themselves for the sacrifices that went with fighting a world war. The disastrous invasion of Gallipoli yielded thousands of military casualties, making the Eastern Front and the Middle East an important focus of the war and a symbol of the struggle that lay ahead.

At the same time, news of civilian massacres shocked but also offered a reason to continue to fight Germany and its ally, the Ottoman Empire. Information on what was happening in Turkey reached Britain through reports, images and, of course, Bryce's Blue Book. Advocacy organizations held public meetings and a host of publications responded to the killings with both outrage and offers of support. Religious and secular organizations, once inspired by Gladstone's untiring advocacy on behalf of Armenian causes in Britain, now sought broader international appeal. New organizations cultivated trans-Atlantic and European-wide connections to provide aid and advocate on behalf of a project Lord Bryce called “saving the remnant” of the Armenian people.

Britons might not be able to do anything about the bloodletting on the fields of Belgium and France, but some believed that they could help to mitigate the worst of the war's effects on innocent civilians. This chapter traces the public and private humanitarian response to the Armenian Genocide which focused on doing just that.

The New Philosophy of Aid Work

Historians have argued that the war indelibly changed humanitarianism by making it a global movement focused on saving a fragile and vulnerable humanity.1 In practical terms, massive human suffering on the battlefield and on the civilian front required a new kind of response in terms of philosophy, scope and scale. The question of what could be done for victims was understood to be part of a larger political and humanitarian problem that had no easy solution. While politicians at Whitehall equivocated in their dealings with the unprecedented scale of civilian causalities of war, activists launched a campaign to intervene in the immediate crisis on the ground. The “first international human rights movement,” in the words of Peter Balakian, found its clearest expression in the humanitarian response to genocide.

Peace arrived in Europe with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. The final settlement with Turkey came four long years later in 1923. After the signing of the Armistice at Mudros in 1918, fighting on the Eastern Front was supposed to have stopped. The first attempt at negotiating peace between Turkey and the Allies in 1920 with the Treaty of Sèvres was an abysmal failure and fighting in the East continued. The final settlement would not come until the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne three years later. In this no man's land between war and peace, humanitarian relief agencies attempted to fulfill public and private commitments made to Armenians and other Ottoman minorities during the war.

The founding of the League of Nations after the signing of the Versailles treaty internationalized the problem of the stateless refugee. When the war ended, the largest refugee emergency to date followed in its wake. This was the most dramatic immediate aftereffect of genocide. The urgent task of getting aid to those who needed it guided the form that the response ultimately took. Humanitarian organizations, previously focused on feeding and protecting survivors of the massacres, turned to the task of supporting resettlement efforts on behalf of the millions of refugees forced to leave the former Ottoman Empire, which collapsed after the war. They left to settle primarily in Russian lands and the newly mandated territories of the Middle East created from former Ottoman lands that resulted from territorial adjustments made after the war.

The immensity of the crisis, coupled with war weariness at home, meant that relief efforts often faltered along with the failed effort to find political solutions to the Armenian crisis. “Ever since the deportation of the Armenian people in 1915,” affirmed the Armenian Fund which the government charged with overseeing refugee resettlement, “the problem of refugees has been upon the conscience of the Allies … our responsibility cannot be forgotten.” In the postwar moment, “Relieving the desperate plight of the scattered remnants of the Turkish Armenians” emerged as a key motivation for humanitarian efforts.2 This focus on relief work as the primary way to resolve what observers called “the tragedy of the Near East” would have important implications for how humanitarian intervention came to be defined as a policy of neutral aid.

Humanitarian Relief in a Warzone

English people have always taken an interest in the Armenian nation and the sums of money that have been raised … show that the people of this country however great the present needs may be in other directions have not lost sight of such a worthy cause in the face of new needs.3

Old advocacy organizations found new energy and a sense purpose in the continuing war crisis. The British Armenia Committee used their “first-hand knowledge of Armenia and the East” to step up advocacy efforts in Parliament.4 Bryce's Anglo-Armenian Association made the case for helping Armenians because they were loyal allies. Religious and secular advocacy organizations such as the Eastern Question Association, the Friends of Armenia and the Anglo-Armenian Association considered work on behalf of Armenians as part of a larger humanitarian calling that went beyond upholding treaty obligations. New organizations emerged to deal with and, in some cases, coordinate relief efforts.

Thus, aid work during the war became the outward expression of the difficult to sustain ideal that the British Empire had an obligation to support a common humanity. This notion took particular hold in Britain and in the United States and inspired new relief organizations that had as an express purpose the amelioration of human suffering through charity work. Promises to keep aid neutral would, some believed, overcome political obstacles that necessarily went along with providing humanitarian assistance in the midst of a combat zone.

War made relief work on enemy territory appeared impractical but not impossible. British consulates had an established track record performing aid work in Adana and in the Russian-Ottoman borderlands. This consul network along with mainly American missionary schools meant aid workers could draw on a sizable Anglo-American presence to realize their projects. In Britain, the Lord Mayor's Fund coordinated efforts among the dozens of aid organizations set up to help Ottoman Armenians, Assyrians and Greeks during the war. It was organized in September 1915, after a meeting in the House of Commons was called in response to a “wave of indignation and horror” sweeping across Britain about the massacres “to establish a special relief fund, on a wide national basis, to supplement the existing pro-Armenian Committees.”

That following month the Lord Mayor held a public meeting at Mansion House, London to establish the fund. Those present at the meeting included a “distinguished company” of politicians and private citizens. The list of attendees included many long-committed advocates for the Armenian cause. Lord Bryce, Prof. Rendell Harris, Anuerin Williams, T.P. O'Conner, Lord Cecil, Lord Gladstone and Rev. Harold Buxton (nominated as Secretary) together inaugurated the humanitarian relief fund, with the Lord Mayor of London serving as president.5 Registered under the War Charities Act of 1916 with offices in Victoria Street, London it was known by its official and rather clumsy name, the Armenian (Lord Mayor's) Fund. It raised over £50,000 for relief work in its first six months of operation.6

In the US, the Armenian and Syrian Relief Committee, later known as Near East Relief, formed the same month as the Lord Mayor's Fund in Britain.7 “Extraordinarily harrowing” reports had started reaching the US from Turkey that August: “The stream of refugees still flows,” read a cable sent in late August, “There is a shortage of bread … The majority of the refugees are ill.”8 US Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Henry Morgenthau, upon hearing these reports, began “urging the formation of a committee to raise funds and provide ways and means for saving the Armenians.” As he told his State Department colleagues, “The destruction of the Armenian race in Turkey is rapidly progressing.” Morganthau's message made its way to James Barton, Secretary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in Boston who subsequently organized a committee to raise funds to send to the Ambassador “for relief purposes.”

The organization quickly raised $100,000 in its first month of operation and offered a way for Americans to support the war from a safe distance.9 US neutrality in the war made humanitarian relief the only tangible way to show what amounted to growing American sympathy for war victims and Allied efforts against the Central Powers. In Britain, fighting a war that resulted in both huge military and civilian casualties spread resources for humanitarian aid thin. These factors were coupled with the US’ large population, which included a relatively small but active Armenian–American diaspora. By the early 1920s, almost 100,000 Armenians had settled in the United States.10 Public and private philanthropic organizations together raised hundreds of millions of dollars for relief work immediately after the war, making the extraordinary success of US fundraising efforts possible.

These funds focused on emergency aid and supported projects that brought relief to those displaced by the fighting. The wartime emergency necessitated this approach of providing ameliorative neutral aid particularly for the US, which would not enter the war until late 1917. Humanitarian work had to be apolitical and getting things done was often a matter of making accommodations to make sure that aid reached the needy. The Armenian Fund and Near East Relief emerged as the umbrella agencies for relief work in Britain and the US respectively. The “Armenian Fund,” as the Lord Mayor's Fund came to be known, gathered together relief monies, issued reports and distributed aid to other relief agencies in the Near East during and after the war. Near East Relief was incorporated by the US Congress in 1919 and did the same for US relief efforts during the war. Older funds on both sides of the Atlantic willingly worked in cooperation with the new fund. The London-based branch of the International Organization of the Friends of Armenia had set up operations in eastern Anatolia in 1897. It was the successor to the Westminster Fund run by the cohort of British consuls sent to Turkey in response to the Hamidian massacres.11

The war necessitated that humanitarian relief work broaden its focus on ameliorating the effects of the Armenian massacres in a more sustainable way. This meant mobilizing the media and stepping up advocacy efforts. For the Friends of Armenia, which previously operated as a philanthropic aid society run by a small aristocratic coterie, this represented an important shift. Since its founding in the late nineteenth century, the Friends of Armenia had relied on a network of patrons made up mostly of prominent British ladies. By the time of the Armenian crisis, its female patrons had transformed the organization into a full-fledged humanitarian relief society. It had its own newspaper, published pamphlets in coordination with the Armenian Information Bureau and raised its visibility in the communities most directly affected by the massacres in eastern Anatolia. Near East Relief later effectively deployed these same tactics with the publication of its own journal, The New Near East, and produced highly successful film and media campaigns that helped raise awareness and funds.

Friends of Armenia could operate primarily as an emergency aid organization during the war, thanks in part to improved fund-raising and the coordinated efforts of organizations like the Armenian Fund. Support from prominent British officials also mattered. But the war put pressure on the mission as well as the approach to humanitarian relief. Originally founded to influence “public opinion” on the Armenian question, Friends of Armenia had a practical mission “to support as many as possible of the children left orphans through the massacres” of the mid-1890s. This relief work took the form of “industrial centres” where women “who had lost their bread-winners might be able to support themselves.” The idea, popularized by Burgess (see Chapter 3), was to have the needy work in factories making goods for sale on the European and American market. The money would go back to supporting the workers and fund the business centers.

The war made it difficult, if not impossible, in many places to continue this work. Friends of Armenia nevertheless maintained a presence in these districts by cooperating with the Armenian Fund and other international philanthropic agencies. Clinging tightly to Victorian notions that aid should not be given but earned, they used money raised to keep their model of industrial relief work afloat. In 1917, the Friends of Armenia convinced the Armenian Fund that providing employment to women was the most “useful form” that humanitarian aid could take. As the report concluded, “Industrial relief has the great advantage over other methods that it does not tend to demoralize the recipients and make them dependent on charity, an effect which the giving of money inevitable produces.”12

Though the idea of running a factory in a warzone so as not to make massacre victims “dependent on charity” sounds strange and even cold-hearted, it continued as one of the preferred means of distributing aid during the war. This business model of charity work kept money coming in and sustained a number of projects in a time and place where humanitarian aid work was looked on with suspicion and, in some cases, hostility, by the Ottoman authorities. NER also used this strategy. By March of 1917, NER reported employing 2,500 women spinning cotton and wool. They knitted 25,000 pairs of stockings for distribution and made 6,000 quilts “for the utterly destitute” refugees in the cities of Yerevan and Alexandropol, located in the Caucasus. According to NER, “For two years all the clothing and bedding which were given in large quantities to the refugees were made by other refugee women in the industrial workshops.” The organization gave seed and draft animals to refugees in more stable rural regions to help them become “self-supporting.”13

Relief work also continued in the cities. “Constantinople itself was full of refugees and destitute people of all nationalities,” remembered NER head James Barton. By 1917, it maintained three orphanages, a hospital and eleven soup kitchens and distributed over 1.4 million food rations. Work camps also were established. When the British expeditionary force moved across Persia from Baghdad toward the Caspian Sea in 1918, they found themselves involved with the approximately 50,000 refugees who had marched from far-away Urmia, organized into “partially self-supporting” “industrial camps.” 3,000 workers, mostly women, “employed washing, carding, spinning, weaving and making garments” worked under the supervision of American aid workers and the temporary protection of the British military.14

The Friends Mission in Constantinople, run by the British Quakers, long understood the importance of cooperation and accommodation when it came to helping Armenians in Turkey. Director Ann Mary Burgess used her connections with the British consular staff at Constantinople, including Andrew Ryan and Robert Graves, to keep her Constantinople factory going during the war. Walking a fine line between aid worker and foreign missionary, she was able to stay on in Constantinople during the war, despite the fact that Britain had declared war on the Ottoman Empire and attempted an invasion in 1915.

Mission work made Burgess potentially a controversial figure.15 She managed successfully to cooperate with the authorities during the war because of her status as a business woman and trusted member of the community. On the occasion of her “semi-jubilee” at the Mission on the eve of World War I, a celebration was held and attended by business, political, and religious leaders of the Armenian and Constantinople British community. Sir Louis Mallet, the British Ambassador, heartily expressed his congratulations and good wishes. A long list of Armenian community leaders further praised what they called Burgess' important work on behalf of Armenians.16

The Friends Mission's political and cultural ties allowed relief work to continue among refugees during the worst of the massacres. By the time the war started, Burgess' charity business had been operating for almost 20 years. Her influence in British government circles led to a reversal of an Ottoman governmental order that demanded she cease relief work activities and leave the country. Turkish authorities in the end commandeered the school for army barracks and the hospital. Only the orphanage remained unoccupied.17 Burgess, having survived the experience of the Hamidian massacres and sectarian violence after the Young Turk Revolution treaded carefully and worked with non-partisan aid groups such as the Red Cross to sustain the day-to-day activities of the mission.

The mission responded immediately to wartime massacres. Burgess put her factories to work to ameliorate what she called the “sorrow surging round” claiming that, “In this time of sorrow and poverty, our work has been a great boon. Of course the women can only have enough work given them to cover the cost of their bread, seeing the numbers are so high.”18 Even as the massacres spread, the Friends Mission continued its work until after the war. Burgess and her 400 Armenian factory workers maintained a busy production schedule despite wartime shortages that made it hard to get materials. Silk and wool rugs and embroidery work still found its way to customers in England and America thanks to sympathetic agents who served as brokers.19

Coordinating humanitarian work in a warzone on a large-scale, nevertheless, posed profound challenges. When local officials banned relief work in parts of Syria, aid workers had to find new ways to engage in “inconspicuous relief activities” in villages plagued by typhus and cholera. Aid workers allegedly asked mothers “to select from their children those who are to be granted the opportunity to live” which “inevitably condemned to death” the rest of the family.20 As conditions continued to deteriorate, Ottoman officials tacitly agreed to look the other way if local committees distributed the aid in the place of American aid workers. Instability in the Caucasus region made relief work unbearably difficult throughout the war and after.

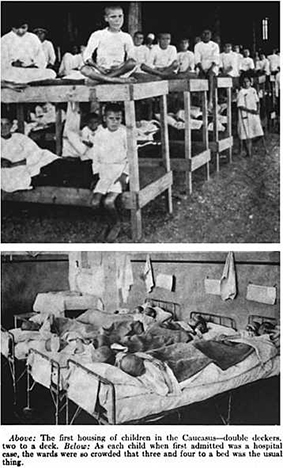

Here coordination between American and British efforts was most evident. While the US had a large number of missionary outposts scattered throughout the Ottoman Empire which provided education and community services dating back to the late nineteenth century, it did not have a significant diplomatic, commercial or missionary presence in the Caucasus. This borderland region between Russia and Turkey which provided an important corridor between the Caspian and Black Sea saw terrible fighting in the first part of the war. This created a mass exodus of refugees, mainly women and children: “The Turkish frontier … is chocked with groups of sick and destitute refugees … The whole country is overflowing … There seems no end to these solid columns moving forward in a cloud of dust. The majority are women and children, barefoot, exhausted and starving.”21 (Figure 6.1) Together, British Quakers and the Lord Mayor's Fund “joined forces with the Americans in a common program” to provide humanitarian relief starting in October 1916 until May 1918.22

Figure 6.1 Refugees as depicted by Near East Relief. James Barton, Story of Near East Relief (New York, 1930).

Ultimately, the success of the business of wartime relief work hinged on the ability to raise funds and maintain transatlantic networks while operating under the radar of Ottoman officials. Humanitarian aid organizations brought together a community of unlikely allies that included aid workers, missionaries, businessmen, diplomats, orphans, widows and commercial and philanthropic patrons who operated in an enemy warzone during one of the worst civilian crisis of the war. “The sad thing is Armenians in Asia Minor are still suffering worse things than death,” lamented Burgess when the massacres started. “We have a room full of widows and orphans who make dolls, donkeys, elephants, rabbits, etc. all day long.” Despite extraordinary challenges she resolved to complete her work: “we are not likely to rest and I do not think we shall wear out for some time yet if when we do I trust the work will go on.”23 The Armenian community mobilized during the crisis as well. In Jerusalem, orphans who arrived in 1922 were taken to the Armenian quarter and then adopted by members of the community. Many left evidence of their arrival etched in the stone buildings surrounding the church (Figure 6.3).

That same year in the midst of the postwar crisis, Burgess reluctantly moved her operations to Greece with the help of a £500 check from the Friends of Armenia. Taking her factory furniture and industrial goods, along with 130 workers, Burgess set up shop on the island of Corfu in “an old Fortress built by the British.”24 The Friends Mission in Constantinople transformed into a refugee camp in Greece where the art of rug making served a new refugee community after the war.

Red Crosses, Military Missions

The ideal of neutral aid did not neatly square with the realities of Total War. Humanitarian relief work necessarily found itself entwined with Britain's wartime mission. The Armenian Red Cross was founded by prominent Liberals and patrons of the Armenian cause in Kensington in December 1914. Viscountess Bryce, the wife of Lord Bryce, served as President of this genteel organization.25 When word of the massacres reached Britain that next spring, the Armenian Red Cross began to focus in earnest on refugee relief and aid to the small army of Armenian volunteers helping the Allied cause. In the coming months, the Armenian Red Cross united the humanitarian and military causes in a single purpose. As one appeal for funds put it, the Armenian Red Cross and Refugee Fund had as its purpose to stem “the torrent of misery caused by the war among the Armenian population of Turkey and Persia … and to provide medical necessaries for the Armenian volunteers fighting on behalf of Russia.”26

The 1915 massacres rekindled what the organization understood as a sacred obligation of Britain to the Armenians as a leader of the Great Powers whose “jealousies and intrigues” indirectly brought about the current crisis. “The very least Great Britain can do,” read another appeal by the Red Cross Committee, “is to try and make amends to the innocent survivors, who after enduring persecution from their birth, have, from no fault of their own, lost their homes, together with all that made life worth living.”27 The Armenian Red Cross used newspaper advertisements, sermons and public lectures to launch its relief campaign. Over 1,800 subscribers raised thousands of pounds for relief work in the first year.

One way of getting aid to needy people was by using Britain's allies. Because of the Russian alliance it made sense for the organization to send funds to the British Consul General in Moscow. He then forwarded aid to the spiritual leader and patriarch of the Armenian Orthodox Church, the Catholicos at Etchmiadzin, and the Mayor of the Armenian-dominated city of Tiflis for dispersal by local relief committees.28 Photos of refugees “being fed by members of the Moscow committee” appealed “to British hearts and consciences more than any words can do.”29 Supplies reached affected areas via allied transport ships located on the Russo-Turkish border where most of the refugees had settled. Items included drugs, bandages and surgical dressings sent via neutral Sweden; warm garments were carried free of charge on Russian steamships.

Donations came from as far away as New Zealand and Japan. British schools, colleges and labour organizations also got involved. Children wrote to the Red Cross to say that they “forego coveted treats or prizes that they might send the equivalent for feeding refugees.” One donor wanted to adopt a baby from the Caucasus while another requested that the organization send a worthy Armenian to serve as a companion for a devoted Armenian nurse.30 Armenian refugees also came to the organization seeking work. Others wrote asking if the organization could help them find lost relatives.

Emily Robinson, a woman raised in the Gladstonian liberal tradition, guided the work of the Armenian Red Cross. Her father ran the Daily News during the mid-1890s and had sent out correspondents to cover the Hamidian massacres.31 Robinson published a series of pamphlets where she referred to Armenia as “the last rampart of Christendom in the East” and argued that Britain and her allies were fighting the war to secure a “lasting peace” guaranteed “not by a Treaty of Paris, London, Vienna or Berlin but by a consensus of opinion in civilized Europe and the United States.” Supporting the Armenian cause was analogous to defending Belgium after the German invasion in 1914.32 “Armenians are our allies as much as the Belgians,” one early fundraising campaign stated. “The only difference being that whereas Belgium has suffered for seven months, Armenia has suffered for five centuries.”

Parallels to news of the rape, murder and kidnapping of Armenian girls were made to the “Rape of Belgium” that helped rally the British to war in the first place.33 News of thousands of girls kidnapped during and after 1915 linked the brutal tactics of Germany in Belgium with its Turkish ally.34 Humanitarian work on behalf of these women and girls led to a special commission set up after the war by the League of Nations to reunite families torn apart by the mass deportations.35 Robinson wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury of her work on behalf of “the Christian women and children forcibly detained since 1915 in Turkish harems.” “White slave traffic is a crime here and is punished as such in European countries,” she continued much as W.T. Stead might have done. “It seems it has only to be conducted on a wholesale scale and by Turks to be quite permissible.”36

The Armenian Red Cross raised tens of thousands of pounds for relief work. It did this by casting Armenia as both victim and hero. Red Cross appeals referred to Armenians as allies who bravely fought alongside Britain and Russia along the Eastern Front. This had little foundation in fact. Both spiritual and secular leaders at the beginning of the war issued a statement upon receiving an Allied request for help declaring that Armenians as loyal Ottoman subjects would not rise up against the Empire. Though effective symbols, these heroes of the Red Cross narrative were little more than an ill-equipped and poorly organized band of international volunteers who largely came from diaspora communities in Europe.37

The ARC used any and all efforts of this small group of mainly Russian national volunteers to make the claim that Armenians both deserved and had earned British support. Assist “us in helping a nation which has done so much to help itself,” one report entreated.38 The Red Cross pointed to heroic deeds of the volunteers as evidence: “After the disruption and collapse of the Russian-Caucasian Army, Armenian volunteers rushed to Transcaucasia to the rescue from all parts of the world and manfully stopped the breach at fearful sacrifice to themselves thus effectively protecting the flank of the British Mesopotamian army from attack by the Turks.” According to the Armenian Red Cross, “This important service of theirs deserves the highest reward the Allies can give.”

The volunteers provided propaganda for the humanitarian cause. Though the assistance of Russian Armenians in the Allied war effort made sense since Russia had sided with Britain, the existence of this relatively insignificant force used by the ARC to further its own aims has been used by some historians as proof that Armenians rose up in rebellion against the Ottoman Empire and thus deserved their fate.39 Views of observers at the time paint a different picture. Armenians were willing to face “fratricidal strife,” according to Churchill, in order to honor their commitments to their respective Ottoman or Russian governments.40

Unofficially encouraged by high ranking officials at the Foreign Office, the Armenian Russian volunteers were largely supported by privately raised money. The Allies felt nervous about arming an untested and badly organized force of volunteers north of the Russo-Turkish border whose loyalty to the Entente some questioned. The Foreign Office refused an offer of help from diaspora Armenian volunteers mainly from Europe and the US during the campaign to open up the Dardanelles in the spring of 1915 organized in France by Nubar Pasha. When the Gallipoli invasion seemed doomed to failure by late summer 1915, it tacitly consented to allow these volunteers to help the Russian campaigns in the Caucasus.41 This untenable situation rendered this international brigade of men of Armenian ethnicity largely ineffective. As the Armenian Red Cross characterized the status of the approximately 8,000 volunteers: “They have been equipped and are maintained by Armenians all over the world at a cost of 6,000 pounds per day. At the present they have no doctor and there are only five untrained Armenian ladies assisting as nurses.”42 The ARC declared that it would split all money raised between four columns of volunteers and over 100,000 destitute refugees living just over the Russo-Turkish border.43

Aid organizations tied Britain's wartime interests with humanitarian aid both to raise funds and support the war effort. Historian J.A.R. Marriott argued that to understand the Armenian crisis required “not merely sympathy but knowledge; a real study of foreign affairs.”44 Providing aid for Armenians meant seeking a clear understanding of what the massacres meant in the larger context of the war. In 1916, the Lord Mayor's Fund launched a British Relief Expedition to the Caucasus “to supervise and coordinate the medical and relief work” amongst Armenian refugees led by a prominent committee member, Noel Buxton. The LMF maintained that the defense of Armenians would effectively counter the Turkish attempts “to exterminate them,” which, he maintained, resulted from ethnic hatred, imperial politics and German intrigue.

The Armenians, it was argued, stood “as the direct obstacle” to the implementation of the exclusionary nationalism “encouraged by Germany” that had led to the war and massacre.45 Thus, supporting orphanages, setting up industrial work centers to employ refugees and starting hospitals and schools was an important way to stand up to Germany. These arguments helped the Armenian Fund to collect tens of thousands of pounds during its first year of operation from donors from all over Britain. Only £1,000 went to displaced Muslim refugees, which was supposed to show that the fund, set up primarily to help Armenian refugees, “drew no distinction of race and religion.” The reality was that most aid dollars went directly to displaced Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians.

By the end of the war, Anglo-American humanitarian organizations raised hundreds of thousands of pounds for relief work and thousands more for political advocacy and education programs. British advocacy groups active during World War I included: The Friends of Armenia, with branches in Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England; the Armenian Bureau of Information, the Lord Mayor's Fund of Manchester; Armenian Orphans Fund (Manchester); The Religious Society of Friends, Armenian Mission; The Armenian Refugees Relief Fund run by the Armenian United Association of London; and the Armenian Ladies Guild of London.46 These organizations raised awareness and kept the Eastern Front on the minds of Britons and Americans during some of the worst years of the war.47 This work continued after the war when longer-term relief campaigns replaced short-term emergency aid as the primary motivating force behind humanitarian activism.

Refugees and Relief

The refugee crisis dominated the business of relief work after the war. “The Armenian nation has lost during the war as many lives as the great British Nation,” the Lord Mayor's Fund asserted in 1919.48 “What ought we do?” The answer on the surface seemed straightforward: “make facts known,” support Government-supported relief measures, make personal sacrifices and abstain from “luxury” and “give generously” to humanitarian relief agencies.49 But, as relief agencies and donors discovered, the massive postwar refugee crisis could not be solved through lofty self-sacrifice or promises of neutral aid.

At the end of the war, “Christian Minorities,” one observer wryly noted, “became synonymous with the word refugees.” Most of these refugees were on their way to the Middle East which came to occupy the southern lands of the former Ottoman Empire. The Armistice between Britain and Turkey signed at the Port of Mudros in the Aegean Sea in October 1918 opened up Mesopotamia and Persia, later to become Allied-controlled mandated territories, to more permanent settlement efforts for this population.50 The mission shift from emergency relief to resettlement happened almost immediately after the Ottoman defeat in the war resulted in the empire's complete collapse.

Near East Relief led the extension of the humanitarian footprint throughout Anatolia and the Middle East during the 1920s.51 It was a crisis of epic proportions. Over one million Greek, Armenian and Assyrian refugees flooded Greece from the Ottoman Empire immediately after the war. Many more would follow after 1923 when the Treaty of Lausanne officially ended the war in the East and dictated the “exchange” of Muslim and Christian populations between Greece and the Ottoman Empire. Greece willingly took in all refugees expelled from the Ottoman Empire as a condition of the Lausanne negotiations. By the mid-1920s, 20 per cent of Greece's population held refugee status.52

More refugees flooded the Middle East, now organized as a collection of weak client states ostensibly under international supervision. Here, refugees attempted to rebuild their lives in regions once part of the Ottoman Empire. The Treaty of Versailles designated the southern lands of the empire as “mandates” in the possession of Britain and France and supervised by the League of Nations. The carving up of these territories between Britain and France began with the secret Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916. Under the Versailles Treaty agreement which officially created a system of mandates that closely followed Sykes-Picot, Britain and France controlled the Middle East. This meant that, in addition to vast oil reserves, these powers took custody of a weary and dispossessed humanity.

British ports welcomed relatively few refugees to settle in Britain and funded only a handful of resettlement projects in the Middle East. The British tightened immigration policy before the war and again after the war and essentially closed its doors to immigrants living in its new mandates.53 France took in the highest numbers of postwar refugees, the result, in part, of an acute domestic labor shortage.54 With limited effect, it supported making the Syrian mandate which it controlled into a homeland for displaced Ottoman Christian refugees. France hoped that this move would win it a demographic advantage over long-standing Arab communities in the region.

Greece, as a state with a majority Orthodox Christian population and geographically at the heart of the crisis, let Armenian, Assyrian and of course Greek refugees stay. It looked for help from Britain, France and the United States, countries with strong historic and cultural ties to these new stateless peoples and was eventually granted a relatively small loan to fund internal relief projects. But this was not enough to fund the estimated £12.3 million needed to mitigate the effects of the refugee crisis.55 Private aid projects attempted to fill the hole in Greece's refugee budget during this time.

Providing humanitarian relief in former Ottoman lands proved more difficult. The lack of stable central governments in the newly designated Syrian, Palestinian and Mesopotamian mandates, coupled with the uncertainty of the postwar settlement with the Ottoman Empire, stood in the way of effective distribution of aid and resettlement projects. Unlike in the case with Greece, the Allies could not pretend to make the refugee crisis go away by loaning money to the barely functioning governments of new Middle East mandates flooded with people who had no place left to go.

Private charities based in the West adjusted to these new postwar realities and began to focus on getting aid money to individual needy communities the Middle East. New organizations like Save the Children were founded while older established organizations led by Near East Relief, the Lord Mayor's Fund and Friends Relief rushed to fund projects that helped in the long, slow project of refugee resettlement. Alongside Near East Relief, the Society of Friends and Save the Children were the largest British-based relief organizations working in the region at the time. Founded in 1919, Save the Children took an early interest in the refugee crisis and the Near East and would eventually absorb other British aid organizations including the Armenian Refugees Lord Mayor's Fund.56

These organizations often worked together, raising money and administering funds throughout the Middle East and Europe during this period.57 Aid poured into Damascus, Aleppo, Constantinople and other cities and towns which experienced an acute refugee crisis. These organizations ran orphanages, distributed food aid, building and farming materials and provided western expertise.58 NER launched a campaign during this time to raise $30 million “to meet the rehabilitation refugee and child needs in the Near East” of the estimated half million refugees who arrived in the region right after the war.59

US-based aid agencies could not shoulder the burden of refugee relief without the help of Britain. NER sent a commission to London for a ten-day conference to see how to proceed after the signing of the armistice since “most of the territory in which the Committee was operating was at that time under the military control of England, France and Italy.” Lord Bryce “opened his London house” and helped the commission form contacts with the Foreign Office, the Admiralty and the Army to facilitate relief efforts. A similar envoy went to France, which also supported public and private relief efforts in the region. British help was understood as particularly important to the Americans since Britain controlled the Allied Mediterranean fleet and most of the communication, commercial and political apparatus of this territory at the time. The mission was a success from the perspective of aid agencies. The American delegates reached an agreement with British authorities granting relief organizations “the free use of the warehouses, docks, wharves and railways under British control in the Near East. The Foreign Office also gave its assurance that officers and men in all areas would cooperate with the relief forces.”60

Private aid organizations like NER necessarily relied on British political, commercial and economic networks after the war. British consuls, previously employed as temporary aid workers, if they were willing, still had a role to play. But now they were joined by organizations that professionalized aid while attempting to work with local officials and international aid organizations. Manchester Guardian war correspondent Philips Price saw this firsthand on a visit to Persia after the war. This led to his suggestion when he got back home that relief funds raised by the Archbishop of Canterbury “be sent to the British consul at Tabriz for use of the British and American committees in cooperative relief service.”61

But the British government itself, while allowing the use of its commercial, military and political networks, provided little by way of monetary aid. In the Caucasus, the US government appropriated relief funds for Armenia. NER acknowledged that the British army “generously distributed relief supplies from their army stores, and also assisted in the matter of transportation and relief supplies.” Officers gifted $300,000 in supplies to assist the work of NER among refugees. Aid organizations also depended on the British military for protection whenever possible. British Indian troops occupied Baku and Tiflis in 1918–19 and were reported by NER to have had “a salutary influence and tended to stabilize the political, if not the economic situation.”62

British officials liked the idea of watching over American aid distribution in the Middle East and the Caucasus. For them, it allowed an element of control over an unsettled region in an uncertain time. No one knew for sure, even after the signing of the armistice with Turkey in October 1918, when the final peace would come or the form it would take. In the four-year interim before the signing of the Lausanne Treaty, the “Eastern Committee” set up by the War Cabinet in March 1918 took responsibility for the Armenian question. Committee members included Lord Curzon and Lord Cecil, who made no secret of their sympathy for the plight of Armenians. As Curzon put it to the House of Lords in 1922, “At every stage, at every meeting that I have attended, the battle of the Armenians has been fought with strenuous and loyal activity by the representatives of Great Britain, and I am divulging no secret, and making for myself no unreasonable claims, when I say that no more active defender of their interests on those occasions has been found than myself.”63

The agenda turned to negotiating a settlement with Turkey by the end of the year. Curzon opened the December meeting citing Britain's obligation to Christian minorities in the Treaty of Berlin and presented a plan to create an Armenian homeland in the south-eastern region of Cilicia, the heart of historic Armenian cultural life. Other Committee members wanted an even bigger Armenia, which they believed would serve as a buffer between Turkey and Russia.64

While the committee was busy discussing plans to carve up the Ottoman Empire – the plans for an Armenian state in eastern Turkey never materialized – Lord Cecil raised the issue of American humanitarian aid. The Committee agreed that support for relief work had the potential to get public opinion on the side of the peace settlement. It was at this meeting that he noted “the great deal of feeling” that Armenian relief inspired among the public.65 Lord Cecil wanted support from the committee for an American offer to distribute aid to refugees in British mandated territories. The committee rejected this proposal, believing that the Americans would take advantage of the situation and ultimately challenge British influence in the region. After some debate, it eventually was agreed that the US supply the money through relief organizations. Britain, however, maintained as much control as it could over the infrastructure and ground support necessary for the distribution of the millions of American dollars flowing into the Caucasus and Middle East.

Refugees on the Move

Things only got worse for refugees after the signing of the peace treaty between Turkey and the Allies in 1923. The settlement officially destroyed the Ottoman Empire, leaving those displaced by massacre and deportation as stateless refugees who could make no claim of belonging to any empire or nation. Turkey emerged from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire as a powerful adversary of the Allies under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, who embraced an exclusionary nationalism that left little room for non-Muslim minority communities in the new Turkey. After the Mudros armistice ostensibly ended the fighting, the Treaty of Sèvres was signed by Ottoman officials at Constantinople in 1920 and included clauses that explicitly protected the rights of Ottoman minorities.

In the end, fighting between Kemalist troops and the Allies continued and rendered the Sèvres Treaty a paper tiger. Greece and Turkey came to blows after Greece invaded the western coast of Anatolia with the help of British naval support in the Mediterranean. In 1922, Mustafa Kemal successfully pushed Greece out of Anatolia by burning the city of Smyrna and defeating the Greek army during the Greco-Turkish war (1919–22). This allowed Turkey, though technically defeated in World War I as part of the Central Powers, to come to the peace conference in Lausanne, Switzerland from a position of strength. The purpose would be to revise Sèvres and the minority protection provisions that the Kemalists refused to accept. President of the Lausanne conference, Lord Curzon, announced that one of the most important issues of the conference would be overseeing “unmixing populations.”66 What to do with the millions of refugees made homeless by the war in the East haunted men like Curzon, who had used the liberation and protection of the Armenians and other vulnerable populations as a justification for war and the continued British presence in the Middle East.

The refugee question became increasingly entangled with the affairs of the British Empire. The eastern settlement was arguably Curzon's most important and controversial legacy as Foreign Secretary. By the time he left the Foreign Office in 1924 he clearly left his mark on almost every aspect of early twentieth-century British imperial and foreign policy. He seemed to have his fingers in everything and succeeded in seamlessly tying together foreign and domestic concerns in the minds of the British public. For Curzon, what was good for the colonies and now the mandates was good for the metropole. He served as Viceroy of India from 1899–1905 and later as a member of Lloyd George's tightly controlled and highly centralized War Cabinet. Between 1919 and 1924, Curzon ran the Foreign Office. In each of these roles he argued for the importance of the Middle East in maintaining British imperial power as a gateway to India. Proudly aristocratic in sensibility and outlook, he did not always see eye to eye with the Liberal Prime Minister. Lloyd George, however, largely gave Curzon free reign in matters related to eastern policy during and after the war.

Curzon believed in the “Great Game,” which held that the main thrust of British foreign policy should be defending India from the intrigues of the Russian and the Ottoman Empires. When it came time to decide if Britain should fight Turkey to defend Greek claims in Anatolia after the war, Curzon came to blows with Lloyd George's pro-Greek policy, which held that Britain had an obligation to support Greek claims to lands in Turkey predominately settled by Christian minorities. Though Curzon sympathized with plight of Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians, his focus never strayed from supporting a policy that bolstered British power in the East. He eventually won the battle with Lloyd George over going to war with Turkey on the side of Greece which he opposed. It was a position he would maintain when negotiating the final peace settlement in Lausanne.

But still there loomed the problem of the refugees. Public opinion would not let Curzon and the British government forget what one historian has called the “problem of colossal dimensions” that took root in the Near and Middle East after the war.67 While the refugee crisis affected all of Europe, Armenians and Assyrians were a particularly difficult case. As former subjects of the now-extinct Ottoman Empire, they belonged to no recognizable nation state immediately after the war. Nor could they go back to their ancestral homes located in some of the now most troubled regions of the Middle East.68 The first attempt at peace had failed in 1920 with the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres, which provided some provision for stateless refugees. When Turkey came to the table again in 1923, Curzon believed that negotiators would not agree to anything that supported the interests of this population.69

Curzon was right, but it was not only Turkey that wanted Christian minorities out of Anatolia. The infamous population exchange provision written into the peace agreement was ultimately negotiated by League of Nations' High Commissioner for Refugees, Dr Fridtjof Nansen. The bizarre decision to “trade” Muslims in Greece with the remaining Christians in Turkey allowed for the continued presence of only a small community of Christian minorities in Constantinople.70 The ethno-religious diversity destroyed by war and genocide gave way to internationally sanctioned divisions based on sectarian lines. At the time, this idea fit well with Curzon's belief that one of the tasks of making peace was “unmixing” national and ethnic groups.

But the virtual elimination of the entire Christian population in Anatolia put pressure on the surrounding regions which were not prepared to host the massive number of refugees.71 In addition to Greece, Armenians and Assyrians eventually settled in British mandated territories in Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq), settlements in Yerevan, the core of the future Russian territory of Armenia, and French mandated territories in Syria. The question of taking refugees in Europe largely was sidestepped by the Treaty of Lausanne. Resettlement would happen in Greece and the former lands of the Ottoman Empire, not Europe.

Britain made it clear that it did not want to take responsibility for the masses of people made stateless by the war. Curzon now faced accusations by critics that he failed to make good on promises to protect Armenians massacred at Cilicia. This was the region he earlier proposed as home of the Armenian state. When the French withdrew their efforts to secure the region for Armenians by force in 1921, it fell to the hands of Kemalist forces. “What would you have us do?” he angrily replied in a heated exchange with Aneurin Williams. “It is a practical impossibility to accommodate them in Cyprus, Egypt, Mesopotamia or Palestine.” He made it clear to Williams, who had come to him to ask for aid where he stood: “there is no money to defray accommodation were it available.”72 Curzon began facilitating plans to transfer Armenian refugees to other places.

The Foreign Office got to work trying to convince New Zealand, Australia and Canada to take refugees no one seemed to want. Hardworking refugees would settle the land, the argument went, and expand the empire: “Many of these Christian refugees are industrious people accustomed to pastoral and agricultural pursuits and constitute desirable immigrants.”73 Australia would have none of it. The Australian government, not the British Empire, would determine its own immigration policy. It turned Foreign Office overtures down flat: “the migration policy of the Commonwealth is confined to British people under the Empire Settlement Act.” Australia would not consider taking Armenian refugees. In New Zealand, they relented “to consider individual applications” but balked at the suggestion by Curzon's Foreign Office to take significant populations of Greek, Armenian or Assyrian refugees.74 Canada eventually took a group of orphan children but chose not to participate in any mass resettlement scheme.75

International Solutions?

This left the League of Nations, still in its infancy, and private charity to deal with the refugee crisis in the Near East. In 1922, Nansen, the world's first High Commissioner for Refugees and architect of the population exchange plan, won the Noble Peace Prize for his efforts on behalf of displaced peoples. Hundreds of thousands of Ottoman Muslims displaced by the war and the Treaty of Lausanne's population exchange received assistance. The genocide raised the stakes for dealing in particular with the “living remnant” of Armenian survivors.76 Greek Muslims forced to move, it rightly was believed, would be welcomed in Kemalist Turkey. It was regarding the displaced Armenian and Assyrian population that postwar schemes for resettlement in the Near East took their most urgent form.

Promises of one million pounds granted by the British Government to solve “the Armenian problem” never materialized. That job was left to the Lord Mayor's Fund, which began taking what it called “the first steps toward the liquidation of Allied obligations to the Armenian People.”77 Save the Children launched one of its very first global relief campaigns on behalf of Armenian children in 1919. The British Armenian Committee lobbied the public, Parliament and government officials to support the work of Armenian aid organizations. Specific campaigns to rescue children kidnapped during the genocide made prominent by the Lord Mayor's Fund found the support of high profile figures including the Bishop of London.78 Still, in 1928, Friends of Armenia continued to implore the British public and politicians in their aid campaigns to answer the question, “What are you doing for Armenia?”79

How did this system of private relief, which relied on cooperation from government and international institutions, actually work? Media played an important part in postwar resettlement and aid campaigns. Advertising in newspapers and magazines, publishing pamphlets and speaking tours all contributed to raising awareness about the plight of refugees. Appeals became more sophisticated and broad-based. Both the Society of Friends and Save the Children embraced film, a technology and media form still in its infancy, as an important tool in representing their anti-hunger and anti-poverty campaigns to the public. The Quakers and Save the Children made films to raise funds to ameliorate immediate want and hunger through establishing humanitarian aid efforts on behalf of refugees willing to help themselves.80 The Society of Friends was satisfied to “leave the work in the hands of the many societies giving active help” in the Near East but extended their own “All British Appeal” for the Near East to raise funds for Save the Children to administer.81 These funds “promoted the self-help principle” whenever they could, setting up workshops to employ refugees in the business of knitting, making carpets and weaving fabrics that were later sold to support relief efforts.82 Some advocates, including Emily Robinson of the Armenian Red Cross, continued to argue that the British government bore responsibility for refugee resettlement, calling Armenians “our smallest ally.” “Armenians,” she concluded need “justice not charity.”83

During the early 1920s, the Lord Mayor's Fund supported a wide range of relief programs among Armenians under the approval and sometimes watchful eye of the British government.84 The British Relief Mission, created in 1922, coordinated private and public relief throughout the Middle East.85 Refugee policy took shape in fits and starts after the war. The refugee camp emerged as an important, if not always effective, tool in the attempt at resettlement. In December 1918, the British established a refugee camp 30 miles north-east of Baghdad at Bakuba.86 Lieutenant Dudley Stafford Northcote, a Cambridge graduate from a prominent aristocratic family, ran the camp during its three years in existence.87 Northcote, along with five British soldiers, was responsible for the feeding, supervision and security of 1,300 Armenian and Assyrian refugees who had fled the killing fields of eastern Anatolia.

Northcote had no previous experience with relief work when he took up his post at Bakuba. As he told his mother in a letter, looking after refugees was “quite a change from soldiering.”88 By spring 1919, the camp housed 45,000 refugees. Northcote took his job seriously, learning Armenian and participating in the daily life and rituals of the refugees, which included an Armenian wedding.89 But he always knew that ultimately his job would be to “repatriate” refugees. The only question was where. Britain and France still wrangled over the details of administering Syria, Mesopotamia, Lebanon and Palestine as “mandates.”90

In August 1920, Northcote got an order to start the repatriation project in the British mandate of Mesopotamia, part of modern day Iraq. He moved refugees to a transitional camp outside of Basra called Nahr Umar. The local population, it turned out, did not like the idea of thousands of refugees making claims to their land. This put the refugee camp in a desperate situation. With nowhere to settle permanently, the refugees stayed on in the camp. The LMF stepped in with £6,000, which bought three more months for the refugees. When money finally ran out, it left the camp's inhabitants in terrible straits. In the end, the British and Iraqi governments and philanthropic organizations together contributed £300,000 to resettle Assyrian refugees permanently in a region people at home now referred to as Britain's “Mespot.”

Then there was the problem of the promised Armenian homeland. League of Nations' Refugee commissioner Nansen and US President Woodrow Wilson designated Yerevan in the Caucasus as a national homeland for Armenians in 1920. It was proposed that the nation would start as a mandate under European, or possibly American, control. Curzon pressed for establishing an Armenian state on a small 11,500 square mile piece of land in December 1920. Proposals for an Allied mandate for the region were initially put forth at the San Remo conference in April 1920 that served as a precursor to the Sèvres Treaty. The mandate never happened and the state of Armenia that eventually emerged was doomed to failure. After two short-lived years of independence it became the Soviet Republic of Armenia in 1922. Today, the region is part of the country of Armenia which won independence after the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s.91 Transporting thousands of Armenian refugees from the camp in Basra to Yerevan where no infrastructure or basic provisions existed to support such a large influx of people with few resources of their own proved near impossible.

The situation was made even more difficult when the British government suddenly cut off funds to support resettlement. In 1921, the government announced that the camp would close due to expense. Refugees willing to leave the Basra camp voluntarily were promised a small food ration. Northcote was appalled and publicly refused to send “women and children out of their tents” into the desert. The BAC successfully lobbied the Colonial Office for more time and launched a public campaign on behalf of the refugees.92 The LMF hired Northcote and took charge with the consent of British officials and escorted the refugees to Yerevan in the company of LMF secretary, Rev. Harold Buxton.

Famine conditions in Yerevan, coupled with the overwhelming flow of refugees, coming in at over 1,000 persons per day, made it a harrowing experience for the new settlers, who had little comfort or support after the aid workers left.93 After another £45,000 of donations came in from public and private agencies including Save the Children, the British government and the LMF, Nahr Umar was closed for good.

Northcote never really got over the experience and could not stop thinking about the refugees he left behind. When he came back home he sold lace work made by refugees in Britain and sent the money back to Yerevan.94 Though aid workers understood that “relief must sooner or later come to an end,” the continuing crisis was not easy to forget. Relief organizations throughout the 1920s appealed “to the philanthropy of the people of our Empire to help.” The need ultimately overwhelmed anything private philanthropy could support. Something more was needed, but the British government did not step up relief efforts. Instead it began disengaging from its already small role in helping stem the postwar emergency in the East. The work of private relief societies ultimately earned Britain high praise from League of Nations' refugee relief agencies. But private aid, in the assessment of the British-based Royal Institute of International Affairs, could not compensate for ineffective government policy. Britain, in short, had not done its bit for refugees when compared to other countries: “It is doubtful, however, if this international work, largely personal and periodic is a sufficient contribution when measured by the stand of those made by other countries.”95

Lord Curzon took these charges personally, becoming cross with those who disagreed with his handling of the Armenian crisis. “You cannot expect this country … to concentrate within a ring of British bayonets a large number of destitute refugees and so to organise an Armenian national existence at immense expense to the British taxpayer,” Curzon wrote derisively to BAC member Aneurin Williams, who again had lobbied the British government on behalf of the Armenians. “You really must trust the government who are just as humane as you are, to do their best.”96 In the wake of the Nahr Umar debacle, no one could blame Williams for his skepticism or his lack of trust in Curzon and the Foreign Office.

It was during this time that Quaker Marshall Nathaniel Fox began working through the Nansen office and the Society of Friends to resettle refugees. Though Fox and the Friends Armenian Committee realized that they could not solve the crisis, they continued to work on behalf of the refugees and cooperate with international and government led schemes. They enlisted the help of other religious organizations, including Anglican Bishop Charles Gore who visited the Armenian camps in Beirut and Aleppo in 1925 and played a central role in establishing the United British Committee that joined the efforts of Armenian aid organizations. This work drew on the Friends' long history of performing humanitarian aid work in collaboration with other relief organizations in the Near East. Gore himself was closely associated with Gladstone and claimed an “intimate friendship” with Lord Bryce, who belonged to his college at Oxford. As Bishop Gore wrote after visiting the Quaker camps in Aleppo, “we have the remnant of the Armenians to work for, to pray for and to hope for.”97

British Quakers founded a number of region-specific aid committees during the war, including the Armenian Committee, which worked tirelessly during the war to raise hundreds of thousands of pounds for relief work through the Friends Emergency & War Victims Relief Committee.98 This organization, according to one historian, distinguished itself from earlier, more “severely practical” relief efforts and “had a strong Utopian strain which grew stronger as the war went on.” Aid would help victims while ushering in a period of profound “social change.”99 In the Middle East after the war this translated into an ambitious resettlement program that attempted to create self-sustaining communities of Christian minorities alongside already existing Muslim-majority settlements and towns.

Fox, who headed the Friends refugee program, maintained the air of a missionary and deeply believed in this utopian vision. Before taking on the role of aid worker, he had served as the head of the Brummana High School in Lebanon. In his unpublished “Account of the Work with Armenian Refugees” he described conditions while making the case for supporting resettlement schemes. The organization advocated “the planning of land colonies near the sea in Syria to draw off the refugee populations of the Armenian camps.” This new development would take pressure off the “scheme of sending further refugees to Russian Armenia,” a region now plagued by famine and an appalling lack of resources.100 Friends appealed to the League of Nation Mandate Commission and received the support of prominent British politicians, including Lord Cecil. Photographs of the houses built under the ambitious resettlement schemes in Lebanon and Syria held at Friends House archives in London reveal the scope and scale of this vision. Rows and rows of relatively well-built homes housed families displaced by war and massacre. Meanwhile, Near East Relief continued to aid refugees through its own projects (Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.2 Orphans who arrived in the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem carved their names and the date of their arrival in the stone of the seminary walls. Some of the names can still be partially deciphered: “Mesrob” “Hovsep” “Parsegh” “Har”. Image and translations courtesy of Adom H. Boudjikanian.

Figure 6.3 Caring for refugees. From Barton's book about NER with accompanying caption intended to describe the extent and scope of need. James Barton, Story of Near East Relief (New York, 1930).

New settlements were located in regions where settlers could farm and make a living, if not by practicing their trade, then by producing artisan goods for the local and European market with the assistance of industrial workshops run by aid organizations. Schools, community centers and churches, too, were part of these resettlement areas. Fox felt cautiously or, perhaps, naively optimistic as the resettlement plan took shape. In 1927, he wrote to a supporter back home from Lebanon of his concerns over finding “none who could or would teach Mathematics.”101 Getting Armenian refugees to learn Arabic in order to assimilate in their new communities ultimately would prove a much more urgent concern. But for Fox, the integration of Armenians hinged on creating infrastructure to create educated and economically viable communities. Assimilation would come as a matter of course.

The scheme to resettle the over 100,000 “homeless Armenians” already living in Syria in 1926 relied on international cooperation. The British Friends developed a program to “create agricultural colonies and to construct urban quarters.” Nansen's office in Geneva oversaw the work and the French, as the mandatory power in charge of administering Syria, provided permission and funds for the settlement. Of the over £96,000 spent on this project, nearly half came from France with the remaining money from American, British and League of Nations funds which donors expected eventually would be paid back by the refugees themselves. Work focused on Aleppo, Beirut, Damascus, and Alexandretta where large concentrations of refugees already were located.

In Beirut, the Central Relief Committee purchased a 50,000 square meter piece of land along the banks of the Beirut River. Though by no means luxurious, the building of 20 “pavilions” with private funds provided shelter to 160 families. This collection of whitewashed two-story buildings were surrounded by private gardens and, “constructed entirely of reinforced concrete, comprised eight apartments of two rooms each, with independent kitchens and water-closets.” More houses took shape. The quality of these dwelling improved as “the cost of building material diminished.” Some new homes were made of sturdy “cement and stone.” The idea was to create a self-sustaining settlement made up of “strongly built, respectable dwellings” for Armenians currently housed in the refugee camps.102

By the early 1930s, Fox and his colleagues began to worry that they would not be allowed to complete their mission. In a report to the Nansen Office in Geneva, he expressed concerns that the deadline set to evacuate the camps “before the end of 1933” would leave 15,000 Armenian refugees without anywhere to go. Donors began asking for “the return of the portion of their funds” once they heard that the League planned to withdraw its support.103 William Jessop, the head of the Near East Relief foundation, wrote in a confidential report in November 1931 that his “visit to Syria in October showed again very forcibly the lamentably inadequate provision that has so far been made to tackle the Armenian Refugee situation in that country.” While expressing hope that the settlement in Beirut would find success, he warned against what he called the “welter of conflicting interests” in Syria where rumors that the French planned to abandon the mandate recently began to circulate. French withdrawal, Armenian leaders suggested, would “make it impossible for many to remain in Syria,” especially along the Turkish border.104

News of the Turkish government's expulsion of over 30,000 Armenians the previous year justified these concerns. These new refugees after having their property seized found their way to Syria with passports stamped “not allowed to return.”105

Conclusion

With more desperate refugees streaming into the Middle East every day, no one knew what to expect when in the early 1930s the mandates seemed certain to expire. Some refused to believe that Britain and France would ever leave. But the uncertainty took its toll on the newly settled refugees left in limbo by Europe's two remaining great empires. Relief projects slowly came to a halt after the 1930s and the internationalism promoted by the League of Nations and private aid organizations could not fill the void. Neutral aid work played an important role in promoting the spirit of international cooperation around helping refugees, but it did not solve the problem.

The British remained at the center of these networks because of the important role that they continued to play in the Middle East after the war. Controlling the region alongside France through the mandate system reinforced the sense of responsibility that long characterized British dealings with the Armenians specifically and Christian minorities in general. This Victorian sensibility that evoked obligations to the Treaty of Berlin influenced and helped structure the humanitarian project during and after the war. The universalist claims that the Allies should embrace a suffering humanity in the wake of a disastrous world war, so clearly embraced by the US, led by the idealistic President Wilson in his “Fourteen Points” and manifest in the activities of Near East Relief, did little to help those trying to make a home for themselves in the newly formed Middle East.

Assessing the failure of the application of humanitarian claims and interventions on behalf of those caught in the cross-fire of imperial rivalries and world war requires looking closely at the rhetoric of international cooperation that attempted to promote a coherent and lasting humanitarian legacy for civilian victims. Organizations like Near East Relief, Save the Children, Friends Relief, Friends of Armenia and others raised money and cooperated with another under the banner of “no politics” in the hopes that aid would go directly to refugees and avoid getting tied up with postwar boundary making and geopolitics.

But the larger costs of such apolitical positioning soon became clear as government support for projects disappeared. Donors and those receiving aid had little recourse to make claims on international and national institutions for help. Humanitarianism with the politics left out in the case of the Armenian refugees obscured the causes of what created the humanitarian crisis in the first place. As Lilie Chouliaraki argues, this kind of narrowly focused humanitarianism can sometimes do more harm than good, isolating the giver of aid in what she calls a “happy bubble” where subscribing to a cause replaces real action on behalf of victims of sexual violence, torture and even ultimately genocide.106

The war brutally exposed the ambiguities of the nineteenth-century humanitarian ideal. To serve Armenia was about serving civilization, to paraphrase the old Gladstonian dictate, but it had necessarily if not always obviously been a political act. Aid workers, individual donors and relief organizations looked for ways to square the circle of disaster relief and find a solution that would end the suffering of the communities they deemed worthy of support. Although the Victorian frame of mind was slowly fading, it continued to influence how the British Empire understood the politics of intervention. It would result in producing the most political of acts: the world's first war crimes tribunals to try Turkish officials for “crimes against humanity.”