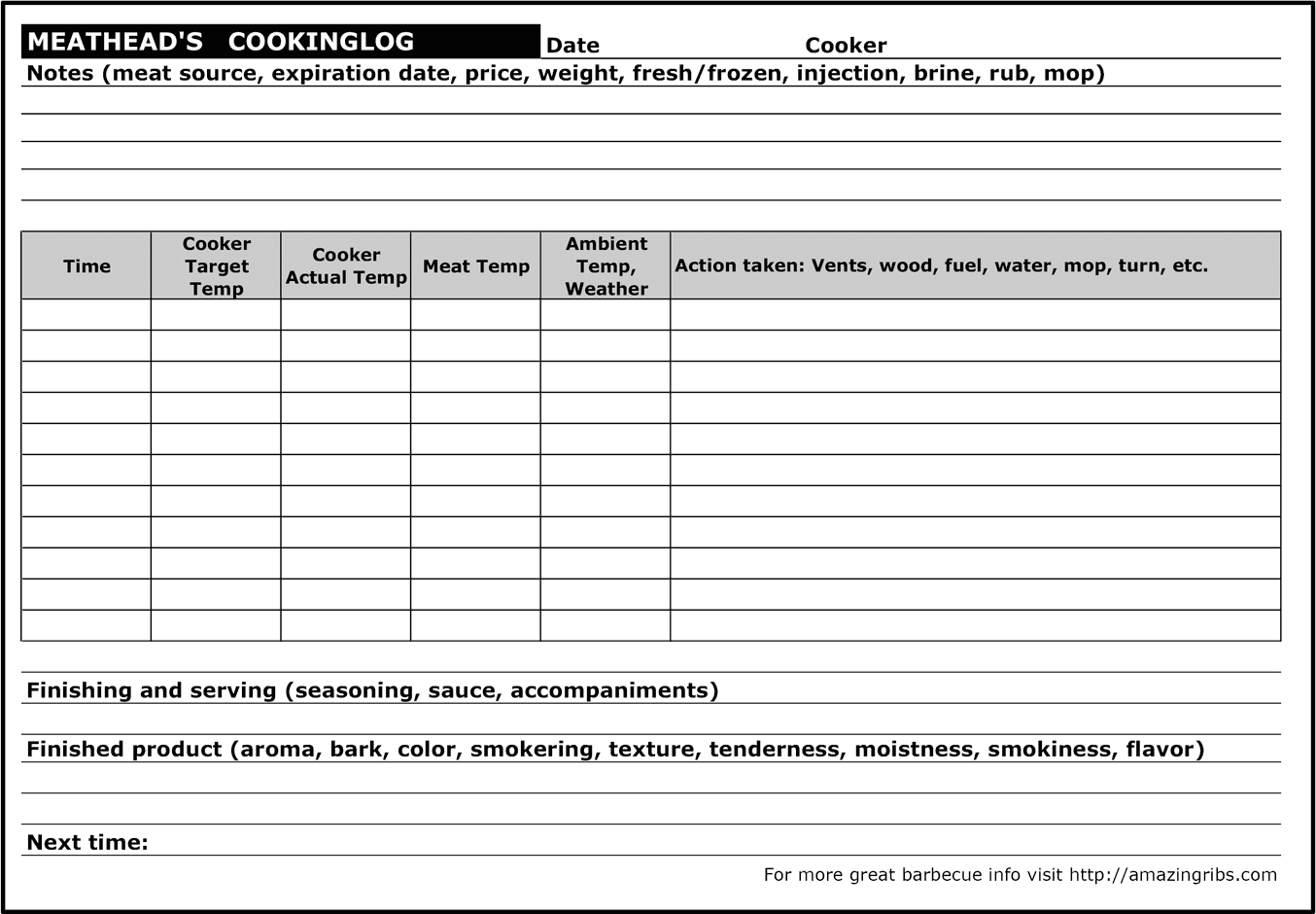

Take notes! Whenever you cook, keep a diary, at least until your methods are instinctive. There are so many variables to master. You should be making notes on the meat, its grade, its weight, where you bought it, how you prepared it, what rubs and sauce you used, the cooker temperature, the ambient air temperature, the wood you used, when you added the wood, and how much. Take a few photos with your camera phone. Below is the diary I use. You can download a PDF or an Excel version at http://amazingribs.com/tips_and_technique/cooking_log.html.

You should check a thermometer’s accuracy soon after you buy it, then once every year, and again if you drop it. Here’s how.

Boiling water. Bring a pot with at least 3 inches of water to a boil and insert the probe in the center, away from the metal. It should read about 212°F. Notice the key word about. The exact reading can vary slightly with air pressure and altitude. Remember that the boiling point of water goes down about 2°F for every increase of 1,000 feet in altitude. In Denver, it is about 203°F.

Ice water. Fill a tall glass with ice cubes (not crushed ice), add cold water, and let it sit for a few minutes. Insert the probe among the ice cubes (not below them) and stir gently, making sure the tip is not touching the ice. The temperature below the ice can be several degrees above 32°F and the temperature of the ice itself can be below 32°F. (The ice-water test does not vary with altitude.)

The cooking chamber of a new grill or smoker often contains dust, grease, oil, metal shavings, or cardboard scraps from the manufacturing and shipping process. Break in a new cooker by wiping down all surfaces with soap and water and rinsing thoroughly. Fire it up, toss in about 8 ounces of wood chips or chunks, and get the cooker as hot as you can for about 30 minutes with all the vents open. This removes all traces of contaminants and lays down a thin layer of carbon on the walls.

Some of the saddest requests we get on AmazingRibs.com are from naïfs who purchased a brand-new grill Saturday and are cooking steaks for twenty, including their in-laws, on Sunday. Instead of cooking tips, they should really be asking for divorce advice. Before you invite the gang over, calibrate your cooker with dry runs. No food needed. You need to practice getting the indirect side of your grill to 225°F and 325°F, and you need to know what warp 10 (maximum heat) is on the direct side. Almost all my recipes call for one of these three temperatures. Figure out how much charcoal you need or what dial settings get you there. Take notes.

The goal is to give you a feel for how your cooker responds to you, and most important, how to hit target temperatures in recipes in all kind of weather. See below for gas grill instructions. To calibrate a charcoal grill, see page 133.

You need to know how to hit your marks: 225°F, 325°F, and warp 10 (maximum heat) in the indirect zone, and you need to know how to get there quickly and easily in all kinds of weather. To gain mastery of your tool you need to fire up your cooker without food, make adjustments that will change the temperature, and take notes in a cooking diary.

You are doing experimental research here, so it is important to apply a vital rule of the scientific method: Change only one variable at a time, and you will learn something factual. Playing with both vents at once, for example, is like trying to control the speed of your car by using both the gas pedal and the brake at the same time.

Controlling temperature on a gas grill or a smoker seems simple: Just turn the knobs. Alas, knobs on gas grills don’t tell you the temperature, so you need to figure that out when you calibrate the grill.

Always ignite the grill with the hood open. Gas can build up under the hood and when you hit the ignition, the lid can blow open. Or worse. Turn one burner on high and leave the others off. Put a thermometer probe above the hot burner, close the lid, and start timing. When the temperature stabilizes, write down the temperature and how long it took to get there. Then move the thermometer probe above the cold burner furthest away, and record the temperature there. If you have three or more burners, add one burner at a time and take measurements at different dial settings. Keep fiddling until you figure out how to get to 225°F and 325°F on the indirect side. Measure the temperature on the upper grate, too.

Now check for hotspots. You’ll need a loaf of white bread. On a piece of paper, draw the cooking surface of your grill, roughly to scale. Divide it into quadrants by drawing a line down the middle of both sides. Turn all burners to medium, close the lid, and let the temperature stabilize. After about 15 minutes, place the bread on the grill in a grid, with 1 or 2 inches between each slice. Move quickly or have someone help you. Close the lid for a few minutes. Then peek at the bread. When they are toasted, quickly flip the bread. You will see that your grill has some hotspots. Mark them on your drawing or just take a picture and print it for future reference. Finish toasting the bread, make some sausage gravy, and chow down.

You want to measure the temperature of your cooker where the food is. But a bubble of cold air surrounds the food at first, so keep the thermometer probe just above the cooking surface, about 2 inches away from the food. Some thermometers come with a handy clip, but if yours doesn’t, use a ball of foil to hold it in place. Just make sure the tip, where the sensitive parts are, protrudes from the foil.

One problem with a lot of grills is that you have to thread thermometer cables under lids, down chimneys, or through vents, and then find a way to attach the probe to the grates without letting the tip touch metal. The lids often crimp or cut the cables, and you’re never quite sure where the tip of the probe is, and if it is touching meat or metal. Then you forget about it, lift the lid, and your thermometer goes flying into the neighbor’s yard. One solution is to drill a hole just above or below the cooking grate and insert the probe through the hole. Make the hole just a bit larger than the probe, and don’t worry if it leaks a little. That small amount of leakage won’t hurt anything. If you wish, look for silicone grommets at your hardware store. Not all probes are the same diameter, but 3/16 inch should work for most. Make sure you route the cable away from direct flame or super-hot grill grates because most cables will melt if exposed to temperatures greater than 450°F.

When measuring the temperature of the meat, test in more than one location, because the composition of the flesh, the rivers of fat, and the bone can fool you. Insert the probe in the center of the side until it almost comes out the other side. To get a reading of the cross-section you just created, pull it back slowly and read the temperatures as you go.

Turning the knobs might not change the actual temperature the way you’d think. Fortunately, you have another tool with which to control temperature. On better grills, you have more than one burner, and that allows you to turn at least one burner off and one burner on, which should help you get to your target temperature. Here’s how to set up a gas grill for two-zone cooking.

If you have a grill with only one burner, or you have more meat than will fit in the indirect zone of your grill, put a water pan beneath the meat. The water will absorb heat and minimize temperature fluctuations. If you keep the cooker temperature at 225°F, the water should not boil because the surface area will allow evaporation that will cool the water, keeping it below 212°F. If the water is boiling, you are running hot. Turn it down.

Here are the two primary methods for using water pans on a gas grill:

Water pans under the grates. Get two disposable aluminum roasting pans that together are, ideally, just about the same size as the interior of your gas grill. They should have 2- to 3-inch-high sides. The pans will get smoke stains on them, so do not use your best roasting pans. Remove your grill’s grates and put the pans on top of the flavor bars, lava rocks, or other heat diffuser. Do not put the pans right on top of the burner tubes. Fill the pans to within 1 inch of their rims with hot water. For smoke, put a pan of wood chips or pellets as close to the flame as possible.

Then place the grates over the water pans and put a thermometer probe on top of the grates just over the water near the meat. Experiment to get the temperature called for in the recipe.

This could take 30 minutes or more with all that water to heat. Adjust the flame up or down, and if you need more heat, fire up another burner. Take notes.

Water pans on top of the grates. If you cannot put pans under your grates, you can put them on top and use wire baking racks or the grates from your indoor oven on top of the pans. Try to keep at least 2 inches between the meat and the water’s surface, otherwise the bottom of the food will be heated by the water temperature, which will be closer to 160°F than 225°F.

If you love the rotisserie chickens from the grocery store, you really need to start cooking them on your grill. You will be surprised at how much better they taste when they aren’t left to dehydrate for hours under heat lamps and when they pick up a little smoke.

When you grill the normal way, it is easy to overcook one side of the food. Rotisserie cooking rotates the food at a steady, slow speed on a spit, ensuring that it cooks evenly on all sides. With continuous rotation, all of the food’s surfaces are exposed to infrared heat that promotes browning. Those surfaces see the heat and then rotate away into a heat shadow, allowing a small amount of the absorbed energy to escape while some of it continues to penetrate the food. Meanwhile, the interior slowly and gently roasts. I recommend rotisserie cooking with the hood open because it slows down the cooking and prevents the exterior layer from building up too much heat and drying out or burning.

As with other forms of cooking, the meat rises in temperature as it heats and juices are squeezed to the surface. On a rotisserie, many of the juices tend to roll around the surface of the meat, basting it, cooling it, and keeping it moist instead of rolling off. Some water still evaporates and drips, of course, leaving behind protein, sugars, fat, and flavor, and creating a great crust, or bark.

When spit-roasting a whole chicken, the wings and drumsticks must not be allowed to flop around or they could burn or even fall off. Place the forks carefully and you won’t need to tie the wings and drumsticks to the rest of the bird.

Some people fear that the metal spear will carry heat to the center of a piece of meat and overcook the roast, but the metal spit inside doesn’t get any hotter than the meat itself, except for a fraction of an inch at the ends.

Check the distance from the spit to the cooking grates. You might need to remove the cooking grates when cooking with the rotisserie so that the meat doesn’t drag on the grates. If you have a rear rotisserie burner, you’ll also want to put a drip pan under the meat and fill it with potatoes or other veggies that will roast and collect the essence of meat that drips from the rotisserie. Put a little water in the pan so the drippings don’t burn. With enough drippings, you can make a delicious gravy for the meat and/or sides.

If you have several chickens on and space is tight, you can run the spear through the sides of the birds. There is no law that says you have to run the spear up their butts. One last warning: The exposed part of that spear is a red-hot poker. You must wear insulated gloves when removing it from the grill and removing the bird from the spear.

If you don’t have a rotisserie burner, it is best to use indirect heat. On a four- or three-burner unit, turn off the center burners and use indirect heat from the two end burners. If you have only one or two burners, use them both and cover them with a drip pan large enough to block the direct heat from the meat. Keep the pan partially filled with hot water and check it regularly. You will get some steam condensing on your food, which will cool it and slow the cooking. As the meat approaches its target temperature, remove the pan and get some dry heat on the surface to firm up the crust or crisp the skin.

Most gas grills use some sort of heat diffuser between the burners and the cooking grates. Sauce and grease can remain on them and the grates. Before you cook a meal, heat the grill all the way to carbonize this gunk. If you skip this step, there can be a lot of greasy soot on your meal. Even with preheating, drippings can cake up on the deflectors, insulating them and reducing their heat output. It helps to pull out the deflectors and scrape them now and then. They take the brunt of the heat and are pretty inexpensive, so replace them when they become warped or corroded. Enamel-coated deflectors corrode with time and need to be replaced, so if there is a stainless-steel replacement, get it. It will last longer.

Inspect lava rocks and ceramic briquets periodically, spreading them around so they are evenly distributed. They are very porous and absorb grease, but when the grease heats up, it usually turns to carbon. Ceramics and lava rocks can often be flipped, but when all sides are full of carbon or loaded with grease, they will need to be replaced.

If you are using water to clean, remove electrical parts like igniters or cover them with plastic wrap and tape. Some new grills have glass or ceramic infrared burners. They need to be handled very carefully. Read the manual.

To clean the inside bottom of the cooking chamber, remove the heat diffusers over the burners and anything else that is easy to remove; scrape below and between the burners with a putty knife.

Clean the louvers that allow exhaust to escape, if only to make sure they are unblocked. These louvers provide draft through the cooking chamber, which pulls oxygen into the combustion system so you get optimum flame.

Gas grills have a system for regulating the flow of fuel from a pipeline or tank, mixing it with oxygen, igniting it, and turning the flow up or down to adjust the temperature. A number of things can go wrong with the process, although they rarely do. You need to maintain the system to keep it efficient and operating at optimum heat, and to make sure it is safe.

Before you do anything, make sure the gas supply is disconnected and the valve is closed.

In order to function properly, the propane tank or natural gas pipe must be connected properly. Keep in mind that for safety, the threaded connection works in reverse of the usual “righty tighty, lefty loosey” rule. Gas connections tighten when you turn them to the left. There is often a flexible hose connecting the gas to the grill, and somewhere along the line there is a flying saucer–shaped regulator (above). Look for cracks, cuts, or kinks in the hose. If there is anything suspicious, replace it. Wipe the threads with a cotton cloth or towel on all sides before mating them. The regulator has a small hole on the top. Make sure it is not clogged. To protect it, turn it so the hole is facing downward.

If you smell or suspect a leak, mix up some soapy water and, with a brush or cloth, paint it on the tubes. Open the tank or pipeline valve and look for bubbles. If you find leaks, turn off the gas immediately and call the manufacturer or a licensed technician experienced in working with gas systems.

On the other end, the hose will probably connect to a brass pipe that carries the fuel to the valves, one for each burner. That connection needs to be tight. The valves are controlled by knobs. Each knob must turn easily. If a valve is acting up, you can remove the knob and look around, but you should not risk breaking it. Contact the manufacturer for instructions on replacing it.

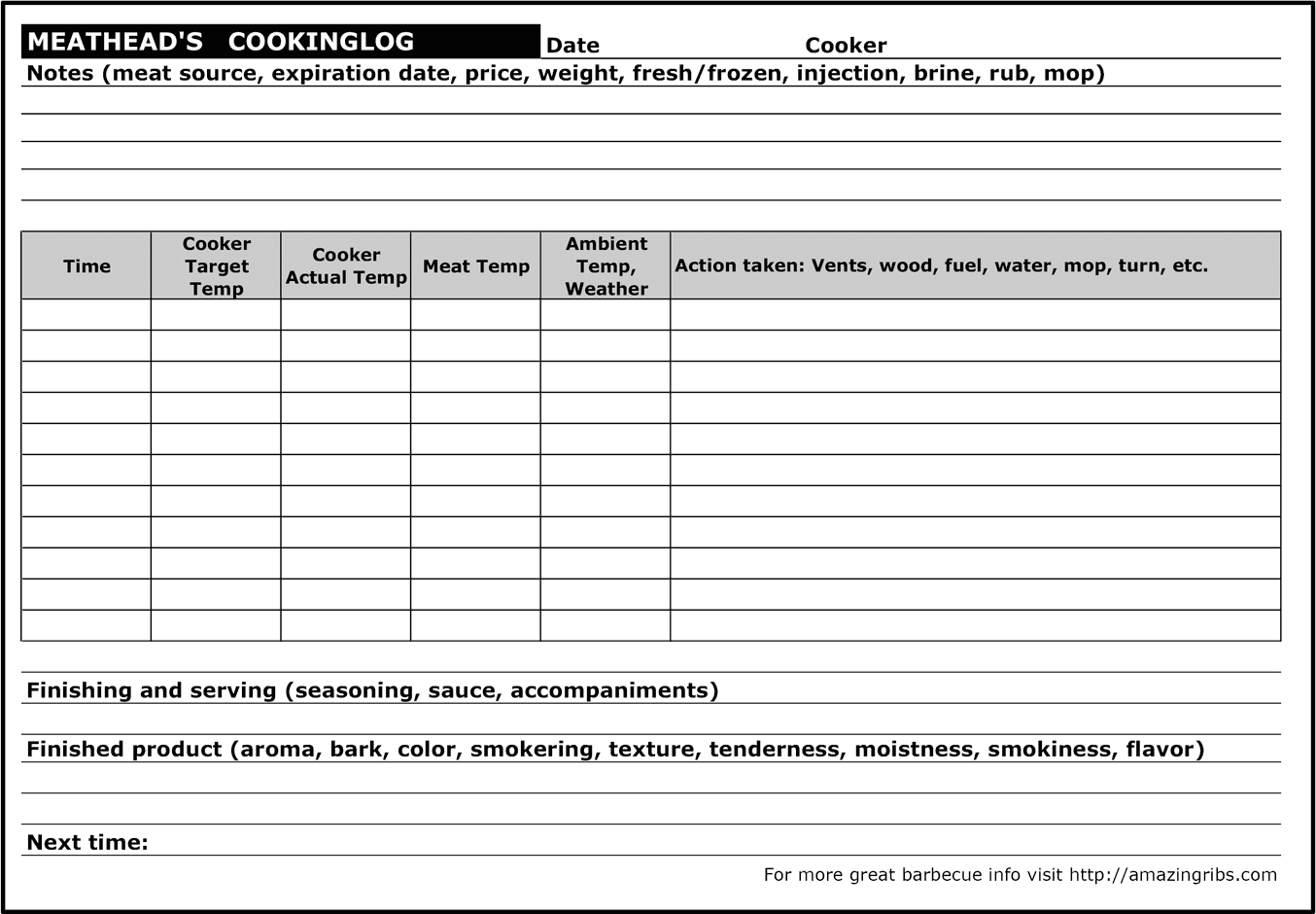

There is usually a short brass pipe coming from the valves. It floats inside the venturi, the adjustable air intake valve shown in blue in the illustration below. It functions like a carburetor, and it is where air and gas mix. Make sure the pipe is centered in the venturi and there are no obstructions like leaves, spiderwebs, or wasps’ nests.

The venturi connects to the burners. They are usually stainless steel, brass, or aluminum pipes with small holes or jets. Inspect the tubes and the gas jets to make sure there are no obstructions. If there are cracks, replace the tubes. If they are clogged anywhere, straighten a paper clip and poke it through the gas jet holes to unclog them. You can even shoot water through the tubes to clear them out.

The factory typically tunes the proper mix, but occasionally it needs adjustment. Loosen the venturi’s set screw, fire up the grill, and rotate the venturi until the flame coming out the burner tube appears blue with little or no orange at the tip. Do this at night so you can clearly see the color of the flame.

There are a number of gauges that attach to the hose near the tank, but I am not impressed. I do like the Grill Gauge (right). It is not much different than the type of scales fishermen use to weigh their catch. Hoist your tank, and the gauge gives you a pretty good guesstimate of how much propane is left. I take mine along when I exchange empty tanks for full ones. You’d be surprised how many are sold underfilled. Regardless, you should always keep a backup tank on hand. You back up your computer, don’t you? It is no fun running out of gas in the middle of cooking.

Here’s another trick: Take a quart of warm water and pour it slowly over the side of the tank. It will warm the thin metal where the tank is empty, while the metal in contact with the liquid propane remains cold. Run your hand down the side to locate the liquid level.

Some gas grill owners find it hard to dial the temperature down to 225°F for low-and-slow cooking. Fiddling with the gas supply system, as some writers suggest doing, can create an explosion or fire, resulting in death and the destruction of your home. I strongly recommend that you hire a professional if you wish to modify your grill’s factory setup. Your local LP gas company will be glad to help for a fee. Frankly, if your grill is running too hot, I recommend that you try to cool it with water pans (see page 118), by leaving the lid slightly ajar, or just by learning to cook at the higher temperatures. Better still, buy a dedicated smoker designed to cook at 225°F (see pages 86–94).

BUSTED! This method blocks ventilation and could cause a dangerous buildup of gases. It forces hot air out through the knob holes and can melt plastic knobs and flexible hoses. It can also crack ceramic and warp metal.

If you can’t ignite the grill, it is usually either an ignition system problem or a gas supply problem. If the igniter does not work, and yours is battery operated, check the batteries. Locate the spark generator, typically a stiff wire, where the spark jumps to the burner. Make sure the spark generator is located properly, usually about ⅛ inch in front of a gas jet. If there is no spark, clean the igniter and check all the wiring to make sure it is connected properly and the spark generator is not touching metal. If it still doesn’t work, you should be able to light the burner with a long match, a long-handled butane lighter, or a match held with tongs. If you need a new igniter, most manufacturers sell replacements.

If the igniter works and the grill still won’t fire up, the tank may be misbehaving. Some propane tanks contain a safety device that slows the flow of gas if it thinks it’s moving too fast. It can be wrong. To outsmart it, turn the tank valve off and disconnect the tank. Open the grill lid. Turn the knobs on the grill to high for 1 minute to bleed off any gas in the pipes and then close them. Reconnect the fuel tank and turn on the valve slowly. It should light now.

If the problem persists, you may have a regulator problem. They occasionally stick and you won’t get enough gas flow. To keep your regulator from sticking, when you are done cooking, make sure that you turn off the control knobs on the grill first, then turn off the tank valve. The next time you want to cook, open the tank valve slowly. If it still doesn’t work, buy a new regulator or try your spare tank.

Mind your propane in extreme weather. The regulator on a propane tank can jam or become contaminated with condensed water on very cold days. In the north, where temperatures can get well below zero, the gas pressure drops too low for the regulator to operate properly. As a result, some gas grills have problems in very cold weather, especially if the tank is not full. At 32°F, there is still plenty of pressure to run the grill, but at –30°F, you will have an issue.

On really hot days, the tank’s safety valve can also vent propane out of the tank. If you are bringing home a full tank on a hot day, don’t put the tank in your trunk because it can vent gas into the trunk and explode. Always carry propane tanks in an open truck bed or in the back seat of your car with the windows open. And don’t store them in your house or attached garage.

Charcoal is lightweight and cheap, and packs more potential energy per ounce than raw wood. It burns more steadily and gives better heat control than wood, and although it produces less smoke, by adding small amounts of wood, you can still get great smoke flavor.

Consisting mostly of pure carbon, also called char, charcoal is made by burning wood in a low-oxygen environment. The process, known as pyrolysis, can take days and burns off volatile compounds such as water, methane, hydrogen, and tar. Burning takes place in large concrete or steel silos and stops before the wood turns to ash. The process leaves black lumps and powder, about 25 percent of the original weight. When ignited, the carbon in charcoal combines with oxygen and forms carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, water, other gases, and significant quantities of energy in the form of light and heat.

Weather plays an important role in hitting your target temperatures. The sun baking on your cooker will make it warmer, reducing your need for fuel. But on a cold day, cold air coming in through the intake vents will cool the coals or gas jets, and you will need more fuel to get to your target temperature. Wind, rain, and snow can also cool the exterior of your cooker, increasing your need for fuel. For more consistent performance, try to protect your cooker from the elements. Some cooks build plywood boxes as weather shields. You can line it with foil or metal and hinge it at the corners so you can collapse it and store it.

Maintaining a steady temperature depends a lot on the ability of your cooker to retain heat. A Weber Kettle is thin metal and has much less heat-retention capacity than a Big Green Egg, which is made from thick ceramic. Get to know your cooker and how it responds to the weather.

Wind can blow so viciously across the top of the chimney of a charcoal or wood-burning pit that it can suck out hot air, creating a bellows effect in the firebox, kicking the temperature up 50°F and altering the smoke flavor. It can also suck in so much cold air that it cools off the cooking chamber. Wind can also blow out a flame on a gas grill and, if you’re not paying attention, it might sit there, flamed out but still pumping gas into the cooking chamber for an hour. Hit the igniter and you could spend the night in the burn unit.

Never roll your cooker into the garage to cook on a windy day or push it up against the side of your house. Love barbecue, but love your family more.

This is a debate that can end in gunplay. Let’s see if we can settle the argument without the author being shot.

Kingsford is by far the largest producer of charoal briquets. Briquets begin as scrap sawdust and chips from mixed woods from timber mills. The company says that it doesn’t use whole trees. The company claims that its suppliers’ mills don’t treat lumber with chemicals to make it weather- and insect-proof, so there is no chance that those chemicals will be in their product. Kingsford’s quality-control staff says they inspect the raw material to make sure there is not too much softwood.

The sawdust arrives by truck, and a bulldozer pushes it into a conveyor that separates large chunks and foreign matter like rocks. Another conveyor moves it to a huge rotating barrel for tumble-drying, which takes the moisture from about 50 percent down to about 35 percent. Then the sawdust goes into special ovens called retorts. With little air in the retort, the wood burns down to char, and comes out at about 25 percent of the weight that went in. It is then crushed.

Kingsford’s standard blue bag of Sure Fire charcoal is mixed with small amounts of anthracite coal (almost pure carbon), mineral charcoal (a form of charcoal found in coal mines), starch, sodium nitrate, limestone, and borax. The slurry is then molded into distinctive pillow-shaped briquets with the K-shaped channels that promote airflow during the burn.

The additives act as binders, improve ignition, promote steady burning, reduce air pollution, and make manufacturing more efficient. Some cooks complain about the additives, but I don’t see anything scary in them. All of these components can be found in nature. Some folks say they can taste the additives in their food. I can’t, and in a previous career, I was a professional wine taster.

Self-igniting Match-Light charcoal, which has mineral spirits added to promote ignition, is a different story. Kingsford and government regulators say it is safe if you follow the instructions, but I can smell the hydrocarbons and fear they can taint the food. I don’t use the stuff.

In 2008, Kingsford introduced Competition Briquets in a brown bag. The company says they are made with only char, starch as a binder, and a bit of borax to help it release from the manufacturing presses. My friend John Dawson of PatioDaddioBBQ.com did a comparison test of regular blue-bag Kingsford and Kingsford Competition. He showed that the Competition briquets ignite slightly faster, burn slightly hotter, and produce less ash, with a burn time that is about the same as that of ordinary briquets. Sensitive palates say Competition tastes better. The problem is they cost almost twice as much as the blue bag.

There are other good charcoals out there. I like Royal Oak and Duraflame Real Hardwood Briquets. Wicked Good 100% All Natural Hardwood briquets are made from just char and starch. They are not widely available.

BUSTED! The folks at Cook’s Illustrated took two typical charcoal chimneys and filled one with lump charcoal and one with briquets. They fitted two identical grills with seven digital thermometer probes each, and learned that by volume, not weight (volume being how most of us measure charcoal, especially if we use a chimney), the two burned at about the same temperature for about 30 minutes, but after that, the briquets held heat longer and the lump turned to ash faster. They repeated the test eleven times, with the same results.

Hardwood lump charcoal is made from scrap wood from sawmills and manufacturers of flooring, furniture, and building materials. Branches, twigs, blocks, trim, and other chunks are carbonized, resulting in lumps that are irregular in size, often looking like limbs and lumber.

Lump’s big advantage is that it burns thoroughly and leaves little ash because there are no binders or other additives. Also, the bags are lighter and easier to handle because the lumps are lighter and shaped irregularly, so there is more air in the bag.

Often, lump charcoal is not thoroughly carbonized. Some of the larger chunks frequently have cellulose, lignin, and other wood components left in them, and when they burn, they give off smoke and flavor. This can be a pleasant addition to your food, but it isn’t controllable. You don’t know from one meal to the next what you’re getting. Top pitmasters prefer to burn charcoal and then add the wood of their choice to produce the quantity and quality of smoke they want.

Lump is harder to find than briquets, more expensive, and burns out more quickly so you need to add more during long cooking sessions. It does not coat with ash as briquets do, so it’s hard to tell when it’s burning at peak temperature. It varies in BTUs per pound; it varies in wood type from bag to bag; and it varies in flavor from bag to bag.

If you use lump, you’ll often find charcoal dust and small crumbs in the bottom of the bag. Discard them. If you pour them in your grill, they can clog the air spaces between the coals, constrict airflow, and choke back your fire by as much as 50°F. Remember, oxygen is just as important as charcoal.

Finally, it is not uncommon to find rocks, metal pieces, and other foreign objects from the lumber operations where the wood is gathered. I am also concerned that some of the wood used to make lump charcoal could contain wood preservatives such as creosote, chrome, copper, pesticides, fungicides, and arsenic (now illegal but found in plenty of scrap from building demolitions).

Bottom line: It’s inconsistent. For this reason, few of the top competition teams use lump.

You’ll find more than seventy-five brands of lump charcoal out there, including everything from hickory, mesquite, and cherry to coconut shell and tamarind. For definitive ratings and reviews of lump charcoal, visit Doug Hanthorn’s website, NakedWhiz.com.

As a cook, you need control and consistency. You get that from briquets, not from lump. There are about 16 Kingsford briquets in a quart, and 64 in a gallon. A Weber chimney holds about 5 quarts, or about 80 briquets. That’s a constant quantity of energy. There are many variables in outdoor cooking, and having a steady, reliable heat source is a big plus.

Harry Soo of Slap Yo’ Daddy BBQ, one of the top ten competition teams, once told me, “I buy whatever briquets are on sale.” Mike Wozniak, of QUAU, winner of scores of barbecue championships, says, “I cook on whatever brand the competition sponsor is giving away for free. Charcoal is for heat, not flavor.”

Pick one brand of briquet, learn it, and stick with it for at least a year until you have all the other variables under control.

Please don’t use starter fluid, mineral spirits, gasoline, or kerosene to start a charcoal fire. They soak into the coals and emit a stink that can be smelled at the other end of your neighborhood, and the fumes can get into your food.

Let’s not even talk about how many sleeves have caught fire while trying to light coals with lighter fluid and a cigarette lighter. If your fire doesn’t get off to a roaring start, please, please, please don’t squirt it with lighter fluid unless you want to see what the inside of the hospital’s burn unit looks like.

Here are some starting techniques that work. Remember that there are really two fuels here, charcoal and oxygen, so make sure all the vents are open wide when you try to light the coals.

The charcoal chimney. With a chimney, there is no chemical aftertaste and no solvent smell in the air, and it’s a lot cheaper and safer than using lighter fluid. A chimney is a tube with an upper compartment and a lower compartment. First you stuff newspaper into the bottom compartment and add charcoal to the top compartment, then you light the paper. After about 5 minutes, grab the handle and give the chimney a shake, so the unlit coals from above land on top of the lit coals on the bottom. That’s about it. In another 10 minutes or so, the coals will be white and ready.

Best of all, a charcoal chimney is like a measuring cup with a fixed amount of fuel (see page 127) that will generate a known quantity of heat. With practice, you learn how many more briquets to add on cold days, and how many fewer on hot days.

Some folks drizzle cooking oil on the newspaper to make it burn longer, but I’ve never found this necessary. Because hot newspaper ash likes to float away and become a fire hazard, I prefer to use a Weber Firestarter, small cubes of paraffin under the chimney (above). You can even make your own firestarters by wadding up half a page of newspaper, dunking it in melted paraffin or candle wax, and letting it dry. Just light the newspaper and it will burn long enough to start the charcoal. The small wad of ash remaining is too heavy to drift off and start a forest fire. If you have a gas grill with a side burner, just turn on the burner and put the chimney on top. No fuss, no muss.

Another cool thing about the chimney: You can cook on it! It makes a hotter wok fire than anything in your kitchen. Just plunk your wok on top and start stir-frying. You can also put a grate on it and grill thin foods right on top of the chimney, a technique I call the afterburner method (see page 247).

One note of caution: Make sure you place the hot chimney on something heatproof after you dump out the coals—and keep it well away from children and pets. The list price is about $20.

Looftlighter. This (pictured top right) is a real boy toy. It is a hair dryer–blast furnace hybrid. Just make a pile of coals, place the red-hot tip of the Looftlighter against the coals, and within 20 seconds you’ll see sparks flying. Pull back a few inches, and in about a minute or two you have a ball of hot coals. Stir, and in about 15 minutes, you’re in biz. Looftlighter is an excellent way to start a chain of coals for the fuse method described on page 132. On the minus side, you need an outlet, you don’t want to use it in the rain, you have to stir the coals, and you have to be careful where you place it when it is hot. It lists at about $75.

The electric starter. This is an electric coil similar to the coils on a hotplate (below). Pour a pile of charcoal in your grill, jam the starter into it, and plug it in. As the coals ignite, remove the coil, and mix the unlit and lit coals together with a fireplace shovel. When you are done, make sure you place the hot coil on something that is not flammable until it cools.

It’s an OK firestarter, but you need access to an outlet, and you don’t want to be using it in the rain. Unlike the Looftlighter, however, you can walk away while it is doing its thing. List prices start at about $15.

Propane torch. Then there’s the real flamethrower. Connect it to a propane tank, hit the spark, and whoosh! Within a few minutes, you can get a whole bag of charcoal glowing, and that makes it popular on the competition circuit. Unlike gasoline or lighter fluid, propane is flavorless and odorless when it burns. It is also good for burning weeds from the cracks in your patio and flushing out enemy woodchucks. This is the kind of tool Carl Spackler would love. The Red Dragon Torch is shown below. List price is about $100.

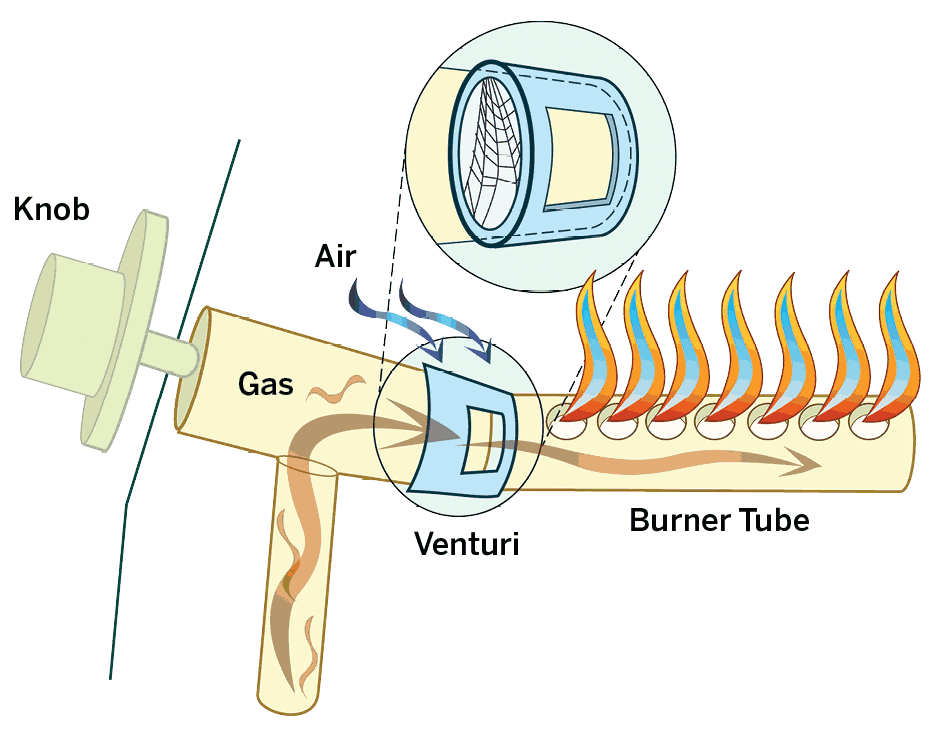

You have two primary ways to control temperature: fuel and air. Most charcoal and wood grills and smokers have two air controls.

The intake damper (right) is near the charcoal or wood, and its job is to provide them with oxygen. The intake damper is the carburetor of your cooker. Close it off and you starve the fire, and it will burn out even if the exhaust damper is open. Open it all the way and the temperature rises. On most grills and pits, you can control temperature mainly by controlling the intake damper.

The exhaust damper (aka flue, vent, or chimney) has two jobs: allow the combustion gases, heat, and smoke to escape and create suction that pulls oxygen in through the intake damper. The exhaust damper (right) needs to be at least partially open at all times in order to do both jobs.

If the temperature starts to get away from you, choke the fire by closing the intake damper. It is more important than the exhaust damper. But don’t expect an instant response. It can take 10 minutes for you to see real movement in the thermometer.

If the temperature drops too low, open the dampers wider. You may need to knock some ash off the coals with a stick or remove ash to keep it from blocking the airflow. If the temperature is still too low, add more coals.

If it is running too hot, and you have already closed the intakes, you can crack the lid. In the picture above, the hot coals are pushed all the way to the left and the meat all the way to the right. The lid is partially off, so hot air from the coals will flow over the meat and out. I have also been known to remove the lid altogether and put a metal pan over the food as a makeshift lid on a hot day when the fire is running hot (as shown below).

Adjusting the quantity of charcoal also controls the temperature. That’s why a chimney and briquets work so well together. With practice, you’ll learn how many coals a full chimney, half chimney, and so on gets you to your target temperature. Each coal is a bundle of energy. Add more, and you add energy.

After you’ve been cooking a while, the coals will start to die, and you will need to add more. Get a feel for what happens when they ebb, and add fully lit coals from the chimney starter as soon as you see the temperature sliding down. You can add unlit coals, but they will belch smoke, and they take some time to get up to temperature. You will need to experiment to learn how many to add and when. The problem is that an hour later, you have to add more. This means you have to watch the thermometer like a bachelor at a beauty pageant. Every cooker design is different, so master your tool by practicing.

For long cooks, there are other ways to stablilize the temperature.

The Minion method. Jim Minion, a caterer, invented this technique for his Weber Smokey Mountain smoker. It involves pouring lit coals on top of the unlit coals at the start of cooking. The hot coals above gradually ignite the unlit coals below as the old coals die out. It works remarkably well and can keep your cooker chugging along at the same temperature for hours, although it does produce some white smoke. The exact amount of lit and unlit coals varies from device to device and from season to season.

The fuse method. For this technique, the coals are laid out in a line, and hot coals are added to the end of the line. The coals ignite like a slow-motion fuse, burning from one end to the other, producing a steady supply of heat for hours. At right is a U-shaped fuse made with bricks.

BUSTED! Here’s how this parlor trick works: Once you get your coals down to glowing embers, fan them to blow away any loose ash. Some people use a hair dryer. Take a steak, pat it really dry, and lay the meat right on the coals. Every time I’ve tried it, small amounts of ash and even whole coals have stuck to the surface, and there have been seriously scorched dry spots. Here’s a better idea: Place a wire rack 1 or 2 inches above the coals. That prevents scorching, dry spots, and ash, while still giving you heat intensity. Live in the Stone Age if you wish, but I’m here to tell you, things are better in the Iron Age.

To get a dark sear on a wet surface like a steak or burger, raise the bottom grate by placing bricks under it and use lots of hot coals. That puts the heat source about 2 inches below the food grate. When you add hot coals, they will be just 1 inch below the meat. Perfect for searing!

Now it is time to practice. Let’s do some dry runs with a good thermometer, but without food.

When coals are fully lit and covered in gray ash, they are at peak temperature. From there, they slowly lose heat as they are consumed by combustion. It will take about 15 minutes for them to ash over, so don’t dump the coals into the grill until 20 minutes after you have lit them. Repeat these steps exactly for each test.

To set the grill up for two-zone, or indirect, cooking, dump one chimney of lit coals on one half the grill and none on the other half. Open all dampers all the way. Put the thermometer probe just above the grate in the middle of the indirect zone. Measure the distance from the edge where you placed the probe and write it down so you can put it in the exact same location on repeat tests. Put the lid on. On a Weber Kettle, place the exhaust damper over the indirect side. Wait for the temperature to stabilize by watching the thermometer; it should take about 5 minutes on a simple metal grill, longer on a kamado.

Now try to control the heat by controlling the oxygen reaching the coals. That means controlling the intake damper only; leave the exhaust damper open all the way. Make a note of how long it takes to stabilize. Now try to get to 325°F, then 225°F.

Move the probe to the center of the direct side, right over the coals, put the lid on, and take a reading when the temperature stabilizes. Make sure you are using a thermometer that can withstand high heat. It can get to 600°F or more on the hot side. Write down the reading.

Then let it die. Clean it out, fire it up again, and try to go right to 225°F. If you can, you are dialed in!

My favorite method of putting out a charcoal fire is to suffocate it by closing all the vents and depriving it of oxygen. It can take an hour or more for the coals to die, but they will go out—as long as your cooker is reasonably airtight. The unburned coals can be used again.

You can extinguish a charcoal fire by dousing it with water, but beware, steam will come rushing up and can scald you. Plus, the hot water and ash will drain out the bottom of your grill and onto your sandals, which could put you in a wheelchair. Wet ashes can also form a concrete-like crust that will corrode your firebox. If you have a ceramic grill, never use water to douse the fire; the rapid temperature change and steam created in the ceramic might crack it.

When the coals are thoroughly dead and dry, any partially burned ones can be shaken to slough off excess ash, dried in the sun, and then used again. But it can take days for coals to thoroughly dry, so if you plan on using the grill soon, don’t douse them with water.

After grilling, empty the bottom of your grill and discard the ashes. Don’t leave it in there for next time. Ash is a great insulator, and it reduces the amount of heat bouncing off the bottom of the cooker. Too much ash can choke off oxygen or be stirred up and coat your food.

BUSTED! Salesmen love to say this. But the vast majority of the heat in a kettle grill radiates directly from the surface of the glowing coals. Some heat may reflect from the sides, but very little reflects off the curved bottom of the bowl. Any heat that hits the bottom of the kettle just bounces back into the coals. So the parabolic shape of the kettle is no more efficient than a square box.

Having a smoker opens up brave new worlds of cooking, but you don’t need a dedicated smoker to make quality smoked meats and vegetables. Most grills can be adapted to the task. That said, it is usually easier to control temperature with a good smoker. Most smoking in my recipes is done at 225°F, and a few at 325°F. Let’s look at how to smoke.

There’s no secret to smoking on a grill. Just use a two-zone setup, keep the heat on the indirect side low, place the food on the indirect side, and place wood on the hot coals. Start by pouring about 1 cup of dry hardwood, fruitwood, or nutwood on the heat source until it smokes, and resist the temptation to add more wood until you’ve tasted the food and learn how much smoke flavor your grill creates and how much you like. You’ll need to experiment with where you place the wood and if you wrap it in foil or put it in some other container.

Every grill design is different, but here’s how to set up the world’s most popular charcoal grill, the Weber Kettle for smoking. If you don’t have one, you can easily adapt these concepts to your grill.

Weber manuals tell you to put coals on both sides and the food in the center (right), but there is a better way that gives you more indirect cooking area and won’t singe the edges of the meat. Push all the coals to one side, and add a water pan or two if possible.

If space allows, place a pan of hot water directly above the coals and another under the food as shown below. Fill the pans with hot water so the coals don’t expend energy just heating up the water.

Position the grate with one of the handles over the coals. There’s a gap under the handle that makes adding more coal and wood chips easy. Weber sells a grate with hinges (see page 101) to make adding coals even easier, and I recommend it.

Readers often write that they are not getting enough smoke because their wood bursts into flame, so they soak their wood or buy fancy gadgets that limit oxygen, hoping their wood will smolder longer and produce lots of smoke.

Stop worrying and stop soaking (see page 22). Remember that the best-tasting smoke, blue smoke, is barely visible, and it happens when wood burns hot and fast. If your wood burns up in a hurry, just add more wood. When you are cooking something quickly like a flattened chicken breast and you need a lot of smoke in a hurry, then reach for a smoldering device like Mo’s Smoking Pouch (see page 111) or make a foil packet.

For smoke flavor on a gas grill, use hardwood chunks, chips, or pellets. On cookers with inverted V-shaped burner covers (flavor bars), you can often just put a big chunk of wood in the gap between them. You can also put chips or pellets in a foil pouch and poke holes in the foil. Place the pouch under the cooking grate, as close to the flame as possible. If the wood won’t smoke because the burners are not hot enough, put the wood onto a burner and turn it on high until the wood smokes, then dial it back. Or try starting the wood with a lighter to get it going. Another trick is to place two charcoal briquets on the heat diffuser above the burners. The charcoal will ignite but won’t be hot enough to significantly change the oven temperature. Put the wood chunks on the hot charcoal and the wood should start smoking within a few minutes.

When you see smoke and the temperature is stable, put the meat on the rack in the indirect zone. You will be amazed at the rich, complex flavors you can get with this simple technique on a gas grill.

The Weber Smokey Mountain is an old design that still is among the best and easiest to use. It certainly is the best-selling smoker. Here are some tips to get the most out of it and its imitators.

If you can, buy a second bottom grate and lay it on top of the one that came with your smoker so the bars are perpendicular to each other, creating a checkerboard pattern. This will prevent coals and wood from falling through.

There are several charcoal configurations that work better than lighting the coals all at once (as is recommended by Weber) because they hold a steady 225°F temperature for much longer. With the Minion Method (page 131), you pour unlit coals in the basket and pour lit coals on top. With the Soo’s Donut Method, you hollow out the center of the charcoal, making a ring, and pour hot coals into the center. With the Fuse (page 132), you line up the coals and light one end (it works best on the larger unit).

Put together the rest of the smoker, positioning the door so it is easily accessible. Line the water pan with heavy-duty aluminum foil to make cleanup easier. Insert the water pan and fill it with boiling water to within 1 inch of the top. Place the cooking grates in position.

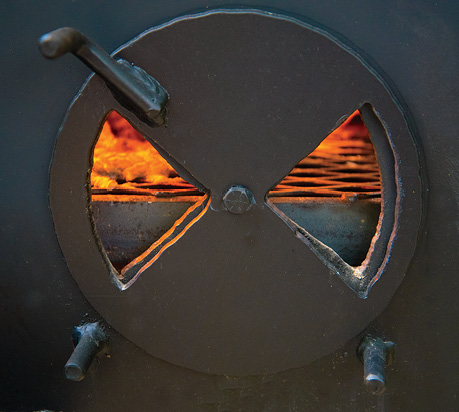

Leave the top vent open all the way at first. Resist the temptation to close it. Regulate the temperature with just the bottom vents. The top vent is needed to create a draft, sucking in fresh air for combustion. If you must, you can close the top vent up to halfway, but no more. Start with the bottom vents open about halfway, more on cold days. When the temperature gets up to about 200°F—and it will get there quickly on a hot day—throttle back the bottom vents to about one third open and keep fiddling with them until you stabilize at 225 to 250°F. Regulating temperature may be a bit trickier on a new unit because it is shiny inside. They can run a bit hot, especially the larger unit. Once it has been broken in and the interior has a dull carbon coat, it will run cooler. When the temperature has stabilized at 225 to 250°F, you can open the side door and drop in some wood on top of the coals. For recipes that call for 325°F, use more lit coals and open the vents to bring up the temperature.

New Weber Smokey Mountains come with a hole drilled in the side for a thermometer probe, but you may want several, so go ahead and drill. Don’t worry, small holes won’t hurt anything and you can always stuff a screw in them to prevent leaking smoke. If you don’t want to drill holes, thread thermometer cables through a top vent hole. Place an oven thermometer probe near the meat. Insert a leave-in meat thermometer probe into the center of large cuts and add the meat. If you can fit it all on one grate, use only the top grate and remove the lower grate to keep it from getting greasy. If you need to use both grates, put the faster-cooking food on top so it is easier to remove. If I want food on both grates to finish together, I rotate the top and bottom grates. The top grate is usually warmer than the bottom one because it sits above the water pan. Placing a pan of beans on the lower grate for catching drips is always a good idea (see page 361).

One of the problems with the 18.5-inch bullet smokers is that they have 15.5-inch grates. Many slabs of ribs, especially St. Louis–cut ribs, just don’t fit. But you don’t have to cut them in half. The picture at right shows how to get two full slabs on a single cooking grate: Use rib racks and bend the slabs to fit. If you do this on both the upper and the lower grates, you can get four slabs on a Weber Smokey Mountain. Another technique is to roll the slab in a circle and run a long skewer through the spot where the ends overlap. This method works fine and keeps the ends from burning.

After the smoke stops, you can gradually add more wood if you know that the meat needs it. There’s always the risk of oversmoking, so until you really know your machine, don’t add any more.

Every hour, check to make sure the water pan has not dried out. When it gets low, carefully add hot water.

Keep an eye on the meat temperature and when it is done, remove it and serve. Then close all the vents to smother the coals and preserve them for the next cook.

When storing a Weber Smokey Mountain, clean it thoroughly, leave the vents open, and take the door off so it will not get moldy inside. Remove all the ash, which can attract moisture and set up like concrete. Put a good cover over the unit, and make sure the cover drops low enough to keep rain out of the lower seam.

If you use a good digital thermometer, you will notice that the dial thermometer in the dome of your Weber Smokey Mountain is not accurate. You’ll also see that the dome temperature is hotter than the top grate, and the top grate is hotter than the bottom grate. By how much? On a nice summer day in the 70s, in the shade with no wind, the dome will be about 10 to 15°F hotter than the top grate, which will be 10 to 15°F hotter than the bottom grate. Your mileage may vary.

Because kamados are so well insulated, they take a while to absorb heat and stabilize, and once they are hot, they are very slow to cool. If you overshoot your target temperature, it may take a while to get it back to where you want it. Sterling Ball of BigPoppaSmokers.com says, “It’s like stopping a semi. You’ve got to brake early.”

If you need to add coals while you are cooking, some models require you to remove the food, the cooking grates, and the deflector plate, which is a pain. But most ceramics are so efficient that you will not need to add fuel even during long cooking.

Some kamado manufacturers recommend that you use lump charcoal instead of briquets. They argue that briquets produce more ash than lump does and that the ash can block airflow. However, there can be a lot of dust in a bag of lump charcoal as well, and that can also hamper airflow. If you’re worried about ash, some briquets—such as Kingsford Competition Charcoal—produce less than others. I prefer briquets for numerous reasons (see page 124).

When you are done cooking, close the dampers. The coals will extinguish quickly, and you can reuse them. Ceramic interiors are more or less self-cleaning. They do not need to be scrubbed. In fact, wire brushes can damage the surfaces. You only need to scrape the cooking grates and brush the ash out of the bottom.

Warning: Kamados and eggs are susceptible to a very dangerous phenomenon: flashback. These cookers are nearly airtight except at the intake and exhaust, and the coals can get starved for oxygen at low temperatures or during shutdown. When you open the lid, oxygen rushes in, and poof: say goodbye to your eyebrows. To prevent flashback fireballs, “burp” the cooker by slowly opening the top damper a bit and waiting a minute. Open the lid slowly and stand to the side rather than the front. Always wear fire-resistant gloves, the longer the better.

Owners of gas smokers often complain about cheap construction, and when you look at the price tag, there’s no argument. Here’s how to improve the performance of a cheap gas smoker.

Never close the upper vents. You need airflow and you need smoke to escape. I know it seems wasteful, but you don’t want to trap stale cooling smoke in the chamber with your dinner.

Turn down the heat. Most of the models I have worked with run hot—in the 250 to 275°F range on the lowest setting. Most meats will smoke fine at that temperature, but I prefer 225°F. To drive down the temperature a bit, try using ice in the water pan or leaving the door slightly ajar. This wastes fuel but will do the job.

Increase the water supply. Using a larger water pan than the one that comes with most units helps stabilize the temperature.

Don’t fiddle with the gas flow. The Internet has several schemes for throttling back the gas flow to lower the temperature. They are risky. You don’t want an explosion.

Use rib holders. Buy at least two rib holders in order to pack in enough meat to feed all the people who will come sniffin’ around.

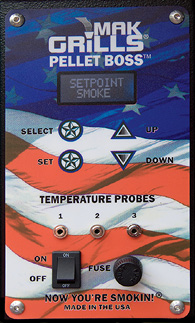

Pellet cookers usually have an auger or another feed mechanism that pushes the pellets into a burn pot, typically a bit larger than the size of a beer can ripped in half. An igniter rod sits in the bottom of the burn pot, and when you turn on the unit, it glows like the element on an electric stove. The auger slowly turns, pushing pellets into the burn pot. As the pellets ignite, a fan feeds them oxygen, and the igniter shuts off. It might draw 300 watts an hour while the igniter rod is on in the first few minutes, then drop down to drawing only 50 watts an hour, less than a standard lightbulb, for the duration of the cooking session.

On the better models, a temperature probe in the cooking area tells the controller the temperature, and if it is below the target, the controller feeds more pellets and blows more air. As with any thermostatically controlled oven, even your indoor oven, the thermostat in a pellet smoker cycles heat on or off as needed. Set it for 225°F, and it cycles on until it hits about 230°F, then it cycles off until the temperature drops to 220°F, then it cycles back on until the temperature comes back up to 230°F, so the average is 225°F.

The small burn pot is covered with a large deflector plate that absorbs the heat and spreads it out below the cooking surfaces. It functions a lot like your indoor stove. The burn pot is small, so there is often a hot spot directly above it. Some units have an optional perforated section above the burn pot that allows you to put meat over direct flame, but the ones I’ve tested still do not sear very well. But this is new technology, so I’m sure they will solve the problem in the near future. Until then, there are two good ways to get an edge-to-edge sear with a pellet smoker: 1) While the meat is cooking, preheat a cast-iron pan or griddle, then turn up the heat and sear the meat directly on the pan, and 2) keep a charcoal grill handy. Even a small hibachi will give you enough infrared heat to get a beautiful sear on a thick steak.

You need to keep the deflector plate clean since it sits right below the food. If you leave sauce and grease on there, it can smolder and deposit soot on your food. Carbon buildup will also diminish its heat transmission. Cleaning it can be a real pain. If you wrap the deflector plate with foil before use and dispose of it after cooking, this problem will never arise.

After 6 or so hours of cooking, you need to vacuum out any ash from the burn cup and the firebox and you’re good to go for the next cook. Don’t worry, the ash won’t mess up your shop vac because there is no grease in the burn cup.

Cooking pellets look like rabbit chow, with the diameter and length of a couple of pencil erasers set end to end. Most are made from oak blended with different hardwoods, each of which imparts a distinctive flavor to the meat. Hickory, maple, alder, apple, cherry, hazelnut, peach, mesquite, and pure oak are among the flavors available. They are all natural, with no petroleum, fillers, chemicals, or glues, and if pellets get wet, they turn back into a pile of soggy sawdust. Be sure to buy cooking pellets, not heater pellets, which can contain softwoods such as pine, treated lumber, and other chemical contaminants that make their smoke potentially hazardous for food. BBQr’s Delight is my preferred brand.

According to Bruce Bjorkman of MAK, maker of my favorite pellet smokers, his cookers use about ½ pound of pellets per hour when set on “Smoke” (about 175°F). At 450°F, the unit’s high temperature, a MAK burns about 2.3 pounds per hour on a nice summer day. On average, that’s comparable to other pellet smokers.

Some owners say the flavor of the smoke is too mild for them. That’s because the wood burns so hot and efficiently. If you want a deeper smoke flavor, use hickory or mesquite pellets, start with cold meat, set the grill to about 200°F for the first hour when it is less efficient and produces more smoke, and then keep the meat moist by lightly painting or misting it with water.

One trick for both grills and smokers at any temperature is to use a water pan, which goes over the heat source. The difference between a drip pan and a water pan is that a drip pan goes under the food, while a water pan goes over the heat source.

Vertical smokers like the Weber Smokey Mountain often come with a pan. A water pan has many important functions:

1. The water in the pan absorbs heat and never rises above 212°F, helping to keep the cooking-chamber temperature down.

2. A water pan blocks direct flame, so you can cook with indirect heat.

3. Water vapor mixes with combustion gases to improve flavor.

4. Water vapor condenses on the meat and makes it “sticky,” encouraging more smoke to adhere.

5. Condensation wets meat and cools it, which slows cooking. This allows more time for connective tissues and fats to melt.

6. Water adds a small amount of humidity to the atmosphere in the cooker and helps keep food from drying out. This effect varies significantly depending on the design of the cooker.

7. Higher humidity in the oven can also help with the development of the smoke ring (see page 15).

Fill water pans with hot water. Cold water will cool your cooker and should only be used if your grill is running hot and you need to cool it down. Fill the pan to just below the lip so you don’t have to keep opening the lid to refill. Put it above the hottest place in your cooker so more water will evaporate.

On a charcoal grill, put the coals on one side and put a water/drip pan on the other. Put the top rack on, put the meat on the top rack above the water/drip pan, and put another water pan on the rack above the coals (shown below).

Pitmasters argue over this. Some like to put beer, wine, apple juice, onions, spices, and herbs in water pans. Some folks like to put sand, dirt, gravel, or terra-cotta in the water pan. But there’s a reason it is called a water pan.

Drink the beer. Drink the wine. Drink the juice. Put the spices on the meat. Just use hot water in the water pan.

Many of the compounds in these other liquids will not evaporate, and even if they do, they have no impact on the flavor of the meat. You may be able to smell them, but the number of flavor molecules in beer, wine, or juice are so few that even if they were deposited on the surface of the food, they would be spread so thinly you would never notice them. The flavors of the spice rub you put on the surface of the meat, the smoke, and the sauce you use are much stronger and will mask any molecules of apple juice or whatever else is in the pan that might end up on the meat. And that goes for drip pans, too. Their job is to collect drippings, not to vaporize flavors.

Many cooks like to put sand or gravel in their water pans. Solids do nothing for the humidity or the flavor. They may help stabilize temperature fluctuations a little, but they will not keep the temperature down like water does. And although water will never go over 212°F, sand and other solids will heat up to whatever the oven temperature is.

To further increase evaporation, fill the pan with those red lava rocks sold at garden stores, and then add the water. Don’t cover the rocks. They are very porous, so they act like wicks, and the large surface area pumps more moisture into the air.

If you line a water pan with foil, cleanup will be a lot easier. When you are done, you will have a pan full of smoky water and possibly fat. Let it cool and the fat should solidify. If it’s taking too long, throw in some ice cubes. Then it is easy to peel off the fat and discard it. I discard the liquid in old bottles or flush it down the toilet (be prepared to clean the toilet after). If you are using charcoal, you could mix the drippings with ash and throw them out with the trash.

A drip pan is different. The purpose of a drip pan is to collect the flavorful juices that come off the meat for use in a sauce or stock. The gas grill shown on page 142 is set up with a drip pan under the meat and it is filled with goodies to make a flavorful stock for gravy. To the left is a small pan with wood chips for smoke. It is resting on a hot burner so the chips will smolder.

If loaded with water, a drip pan can also absorb heat from the fire below, reduce the grill temperature, moderate temperature fluctuations, prevent flare-ups, and add humidity to the cooking chamber. My Ultimate Smoked Turkey recipe (page 307) is a good example of how to use a drip pan. When you’re done, you have a smoked turkey stock that becomes the base for the most incredible gravy.

Keep an eye on your drip pan so it doesn’t dry out and burn all your precious gravy. Keep adding steaming hot water so the liquid is always at least an inch or two deep.

Never use steel wool or metal brushes on a grill or smoker. Use a scrub sponge, warm water, and dish soap. For stubborn stains, try vinegar or diluted ammonia. To remove water spots, try club soda. On stainless, make sure the surface is cool, not hot, and follow the grain. Stainless-steel cleaning solutions do a pretty good job of restoring the luster.

Do not paint the interior where food goes or any surfaces where heat might vaporize the paint. If you need to paint the exterior of a rusted grill or smoker, Professor Blonder recommends Rust-Oleum High Heat Primer, Northline High Temperature Paint, or Cerakote Ceramic Coatings. Brush the exterior with a wire brush, sand, wipe clean with mineral spirits, let dry, and then lay down a light layer of paint. Let it dry thoroughly, and then paint another light layer. Let dry overnight. Be sure to run the grill for an hour or two before using it with food to allow any volatile organic compounds to escape.

Before each cooking session, clean the grates thoroughly (see page 105) and do a little light cleanup to keep your grill or smoker performing optimally, prevent off flavors, and prolong your cooker’s life. Then, at least once a year give your device a more thorough cleaning (two or three times a year if you use it a lot), and clean it if you store it for winter. Check your grill’s manual for any special instructions. If you can’t find it, many manuals are available for download on manufacturer websites.

Clean out the ash. Ash holds moisture and reduces heat, and the combination can chemically attack steel. To make a scoop for removing cold ashes, cut up a plastic half-gallon milk jug and like the one shown at right. You can also use a fireplace shovel. Needless to say, do not remove ashes while they are hot, and always put ashes into a metal can. Gray embers hiding in ash can remain hot for far longer than you’d think.

Charcoal grates. On charcoal grills and smokers, check the lower coal grate for corrosion. If it is warped, don’t try to straighten it out. It will probably crack. As long as it is not preventing airflow underneath, you can keep using it. Replacements are easy to find.

Offset smokers. Grease can pool in the bottom of the smoke chamber of an offset smoker. To prevent messy cleanup, line the bottom chamber with foil before cooking. It is easiest to peel out the foil while the chamber is still warm, but not when it is hot.

Grease pans. Grill manufacturers have different strategies for dealing with drippings and grease. If yours has a grease pan or collector, check it before cooking. It can overflow or catch fire. If there is a grease chute, make sure it is cleaned, too.

Ceramic smokers. Do not wet the interior of ceramic smokers. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

Moving parts. Check, clean, and lube any moving parts like vents and chimneys.

Pellet grills and smokers. Because of their electronics, water is the enemy of pellet smokers, so keep your hose and pressure washer far, far away. Plus, the pellets are made from sawdust, and they will turn into a slurry if they get wet and will then harden like concrete.

Pellets burn very efficiently, so they produce very little ash. A shop vac or handheld vac is all you need, with an occasional scrape of the inside of the lid. (Note that if you use a shop vac, the exhaust on the machine will smell like smoke forever.) Check the vents for creosote blockage. Wipe the tip of the thermometer probe and remove carbon buildup. Keep the deflector plate beneath the food clean. Grease buildup could catch fire.

It’s shocking when you rip the cover off your cooker in the spring to discover the interior covered in white fuzz. Mold loves moisture and grease. Weber Smokey Mountain owners are especially vulnerable to this jolt. To help prevent it, use your cooker often! When you are done cooking, add fresh coals, crank it, and burn off that food and grease residue. Every now and then—especially if you don’t plan to use the cooker for a while—scrape grease off the interior with a plastic putty knife. Store your cooker with the vents open and in a dry place so moist air is not trapped inside. On the Weber Smokey Mountain, remove the side door. If mold invades your cooker, here’s what to do.

1. Discard any charcoal, lava rocks, ceramic briquets, or other porous materials.

2. When it is cool, scrape and scrub everything in sight with a wire brush or a pressure washer. Remove parts and scrape or pressure wash them.

3. Wash everything down with soapy water. Then rinse thoroughly.

4. Finally, fire it up one last time to burn off any mold, grease, and soap residue. Now you’re ready to cook.

To remove mold from a ceramic cooker, do not use chlorine or solvents, do not power- wash, and do not use a metal scraper or a wire brush on the ceramic parts. With ceramics, heat is your only tool to burn off the mold and residue.

BUSTED! The “seasoning” on the inside of a smoker is carbon, grease, and creosote. I don’t worry about a thin coat of carbon, but the flaky schmutz, called “scale,” is carbon that can drop off and land on your food. Scrape it off and vacuum it up. When you clean, work on a surface you don’t mind getting dirty. I use a plastic disposable drop cloth like the ones painters use. The best cooks clean the interior of their cookers regularly. You wouldn’t eat in a restaurant where the ovens were all greasy and dirty, would you?

The next time you hear a charcoal snob say gas grills are for wimps, the proper rejoinder is, “Charcoal is for wimps. Real pitmasters cook with logs.”

If you have mastered smoke roasting with charcoal you may be ready to smoke with logs. Fun and flavor await the patient and practiced outdoor cook.

Direct-heat pits are still used extensively in restaurants throughout Texas and Chicago, and I’ve seen them scattered around the nation in Alabama, Memphis, Kansas City, southern California, and elsewhere. In Texas, the “pulley pit” (right, top) is common. It is a large brick box with a steel cooking grate below a heavy metal lid that is hinged at the back. This weighty cover is tied to a rope that goes through a pulley hanging from the ceiling and is tied to a counterweight to help the pitmaster hoist it open.

In Chicago, the “aquarium pit” (middle) is still in use. It is similar to the pulley pit, but the top is enclosed by thick tempered glass that rises from the bricks and connects to the chimney, making it look like a giant aquarium.

If you want to smoke with logs, the modern way to go is with a high-quality offset smoker (see page 90). Modern units like Johnny Trigg’s Jambo (bottom) have two chambers, one for the food and the other for the fire. They are heavy metal and airtight. The cheap offsets in hardware stores are not suited for “stick burning.”

Some of the best food I’ve ever eaten was cooked over a campfire. The incredible aroma is reason enough to go back to your Stone Age roots and connect with your inner caveman. Wood smoke’s seductive aroma makes marinades, brines, spice blends, rubs, and sauces seem like a waste of time and money.

You can grill with wood over a campfire, over a fire pit, or even on a charcoal grill. But wood can be tricky and takes practice. It requires total involvement and all the senses, which also makes it one of the most fun and rewarding cooking and entertaining methods.

Check with your local fire department before building a campfire in your backyard. There may be an ordinance against it. Check with the neighbors, too. If you raise a stink, they might raise a stink, and neighborly relations are as important to the outdoor cook as good meat. Invite your neighbor over occasionally to cement goodwill.

Campfire. Try to place your fire behind a windbreak such as a fire-resistant building, hill, or stand of trees. Find a spot away from flammable buildings, tents, shrubs, and overhanging branches. Dig a hole 6 to 12 inches deep to contain the coals. Keep the dirt handy so you can smother the fire when you are done. It’s a good idea to enclose the fire pit with big stones, bricks, cinder blocks, or something on which you can place a cooking grate. Rocks reflect heat into the fire, and they keep you and your guests warm. But don’t use wet rocks from the bank of a creek. They can be waterlogged, and when they heat up, they might explode. Never leave a campfire unattended. Keep a bucket of water or dirt handy to douse your fire when you are done or just in case things get out of control.

If you can, make one side of the rock ring higher than the other so part of the grate is higher and further from the coals. That helps you moderate temperature. Leave one side of the fire pit open so you can reach under the grate with a rake or shovel to rearrange the logs and embers when necessary.

Fire pit. You can build a permanent fire pit in your backyard quickly and cheaply with bricks, cinder blocks, flat slate, or, as shown above, concrete garden-wall blocks. They may split over time, but they are cheap. Firebricks will last longer. You can also buy a cooking grate to go over the top.

Fire ring. Used in many campgrounds, a steel fire ring encloses the fire and acts as a windbreak as shown at right.

Collapsible grate. You can use the cooking grate from almost any grill, but manufacturers sell campfire grill grates with folding legs designed specifically for this purpose.

Campfire tripod. My favorite tool is the campfire tripod, with three legs and a cooking grate that hovers above the fire on three chains. You can even skip the grate and hang a cast-iron pot or even a haunch or bird on the chain.

Spit. You can even buy a campfire spit. Some have battery-powered rotisserie motors, or you can crank them yourself.

Hovering grill. Another nice design is a simple pipe that you drive into the ground. The grate slips over the pipe, and it can be raised, lowered, or moved to the side.

BUSTED! Dry leaves and newspaper can produce fly ash, big floating hot flakes that can easily land on your food or set the forest or your house on fire.

Lay fuel out in a two-zone setup. This is especially important for a wood fire because you often need to get the food into a safe zone to avoid burning it. Make sure you have plenty of real estate to move food out of the way of hungry flames.

Getting the fire going is like accelerating a car with a manual transmission. To get into first gear, you need tinder; to get into second gear, you need kindling; and finally, you need firewood to cruise along in third and fourth gear. Ideal tinder is small, pencil-thick dry sticks, pine needles, pinecones, or bark. Kindling is finger-thick sticks and twigs. If you prefer, you can use charcoal instead of kindling. As for firewood, use only dry hardwood, fruitwood, or nutwood logs about the size of your forearm or a little larger. Wet wood and softwoods like pine sputter and put out acrid smoke, which can ruin your meal.

The two best methods to build the fire are the teepee method and the log cabin method. For the teepee, start by piling tinder, build a teepee of kindling around the tinder, and then build a teepee of firewood around the kindling. For the log cabin (below), lay 2 logs parallel to each other, and lay two more on top perpendicular to the first layer. Repeat 3 logs high. In the center, make a pile of tinder, then a pile of kindling on top of the tinder.

If you wish, you can drizzle an ounce or two of cooking oil on the tinder and kindling. Light the fire with long wooden matches or a long-necked butane lighter. You can also use a stick as a match by wetting the end with cooking oil and lighting it.

There are two important things to remember about cooking over a wood fire: Too much heat or too much smoke is bad. A few gentle flames licking the food are OK, but a roaring fire and belching smoke will quickly ruin dinner. The first trick is to start the fire and let it burn down a bit before the food goes on. You want a bed of glowing embers, ideally about 1 inch thick.

Wood burns out quickly. If you are just doing a couple of burgers or steaks, you won’t need to add more. But if you are cooking anything thicker, like a spatchcocked turkey or butterflied leg of lamb, you’ll need to add wood. You can toss a log or two on as needed, usually off to the side to allow it to burn down to embers.

Keep a close eye on the food. Wood fires put out some serious infrared radiation, and fats dripping on hot embers can create an inferno in a hurry. Be prepared to move the food around. Have a safe zone. Don’t let the food get too close to the heat. If the fire is too hot, rake away some embers or raise the cooking surface. If it is too cold, add embers or lower the grate. Getting the hang of it takes practice, but when you do, you’ll beam with pride. If this is your first time, cook meat under 1 inch thick. You don’t want a 1½-inch-thick USDA Prime ribeye to come out tasting like a cheap cigar. Once you know how to tame a wood fire, try thicker cuts.

Pick up a pair of long-handled tongs and well-insulated welder’s gloves (see page 108) for turning the food and moving embers around. As primal and basic as cooking with wood may seem, you still need a good digital food thermometer.

I like to keep a squirt gun on hand to beat back flare-ups. If you use one, beware that they can kick up ash, so it’s a good idea to move the food away before you pull the trigger.

When you’re done cooking, douse the coals with water (stand back: steam can burn you just as badly as flame), cover them with dirt, and discard any dirt or ash that has drippings still on it to discourage wildlife from coming round.

As with a campfire, build a fire with tinder, kindling, and firewood, and let it burn down to embers. Once you have embers, you can move them around to create your classic two-zone setup. As the embers wane, toss small chunks onto the coals. Cook just like you would with charcoal, but watch out—it can get hot in there!

The procedure goes more or less like this: Start with a chimney’s worth of hot charcoal in the firebox. Throw on 3 well-dried logs, each about the diameter of a beer can. Open all dampers and doors and let the dark black smoke pour out as the logs heat up and ignite.

After about 30 minutes, as the flames rise in the firebox, as the smoke color turns white, and as the metal body heats up, you can close the cooking chamber and firebox doors and start the process of stabilizing the temperature. It takes 30 to 60 minutes, longer in cold weather, to get the unit up to temperature and load the metal body with heat. Some cooks like to spray the inside of the cooking chamber with water at this stage to create steam and loosen any grease that may remain from the last cooking session, but it is far better to steam clean after cooking than before.

Begin adjusting the firebox damper until the flames are smaller and your logs have turned black, cracked, and have begun glowing. You still want to see yellow flames. Then start playing with the chimney damper and try to get the temperature in the center of the cooking chamber to about 275°F. Smoking with logs usually needs to be done at a higher temperature than smoking with charcoal, gas, or pellets, because wood needs to burn at a higher temperature in order to create clean smoke.

Don’t close the exhaust damper too much, or you will produce meat that is too smoky, pungent, and bitter. The color of the smoke will tell you how clean your fire is.