9: DELIVERING EFFECTIVE TRAINING: CORE COMPETENCIES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the differences between an instructor and facilitator approach to training

- Describe the core competencies that you require to be an effective instructor and facilitator

- Describe the steps involved in on-the-job training instruction

- Understand the factors that you have to consider when making a training presentation to a small or large group of participants

- Understand and use a number of different questioning techniques in a range of training situations

- Understand the role of listening in a training context and be able to practise active listening

- Understand the purpose of feedback in a training situation and be able to use a range of feedback techniques

- Be able to facilitate training situations and use a range of facilitation skills and behaviours

- Prepare written training materials that suit the specific learning purposes you wish to achieve

- Understand and apply a number of non-verbal communication skills in a training situation.

INTRODUCTION

We focus in this chapter on the core competencies you require to deliver effective training. If you are a direct trainer, you are likely to perform an instructor role, either in an on-the-job or course context. You may also be required to adopt a more facilitator role, which requires the use of a different mix of the competencies that we consider in this chapter. The competencies that you require whether you perform an instructor or facilitator role include: instructing, questioning, listening, facilitating, giving and receiving feedback and the role of non-verbal behaviour competencies.

THE DELIVERY CONTINUUM: INSTRUCTION TO FACILITATION

Most direct training activities that you will be required to undertake will fall within the continuum: instruction to facilitation. Below we outline the key features of each concept.

Instruction

When you perform an instruction role, you are involved in programmed learning. This requires the direct transmission of predetermined learning objectives. The delivery task you must perform is to follow the key steps of instruction:

- You are expected to have, and to follow, a set of learning objectives for all parts of the learning event

- You are expected to be comprehensive, yet keep things simple. You are expected to specify what you expect to achieve, to sequence the material and to practice it, to show and tell and to test that these learners are performing to the level you require

- Preparation is a key task that you will be expected to undertake, involving developing materials, presentations and simulations and appropriate tasks to ensure that all objectives are addressed

- You will need to give consideration to how best to create, and maintain, the interest of your learners. Instruction is a didactic activity and your materials will need to be engaging, your tasks and activities motivating and your training room instruction engaging for your learners

- Instruction requires you to be concerned with modelling. You should provide learning through imitation, “Do it the way I do it”. You will also need to be concerned with managing the retention of information and procedures

- Timing is an important issue: keep everything in perspective

- Practice and feedback are core elements. They enable you to manage trial and error. You will need to ensure that practice is realistic and reflects the actual job conditions. Practice will allow you to reinforce the correct ways and eliminate those that are not.

We know from research that effective instructors possess five important characteristics:

- Consistency, managing repeated delivery of the same training activity

- Very organised and focused on detail, in order to ensure that all aspects of the instruction process are effective

- Cognisant of, and taking account of, the learning abilities of your training group

- Demonstrating patience with the core element of the instruction process, which is showing and telling, trial and error

- Maintaining objectivity in assessing the knowledge, capabilities and behaviours of learners.

You will realise that some of the core principles of instruction create tensions and conflict with the principles of adult learning that we outlined in Chapter Three. Adult learners may find the instruction context difficult for a number of reasons:

- They are more likely to vary in terms of experience

- They are likely to get bored easily with didactic and instructor type sessions

- They dislike feeling exposed and seek to avoid embarrassment

- They are likely to feel vulnerable in feedback situations

- They may have negative perceptions of the training room situation, largely derived from their experience at school

- Sometimes they have a dislike of being “taught”.

Therefore, you may prefer to adopt an alternative approach; nonetheless, the nature of your learning objectives may require that you adopt an instructor style.

Facilitation

Facilitation is at the other end of the continuum, involving the use of a range of techniques and methods that enable your learners to discover, to participate and to experience. Facilitation is a role that direct trainers are increasingly required to perform, primarily because of the needs of adult learners and the changing nature of learning activities in organisations, which are increasingly complex and are most amenable to being taught using an facilitator style.

When you perform in the role of facilitator, you manage the learning process through the use of participative methods and reflection on experiences that you share with the learner. You do not assume that learners are empty vessels to be filled up, but are capable and come to the learning situation with capacity for ideas and current skills.

As a facilitator, you will be very concerned to establish and maintain rapport with your participants. You will need to foster an atmosphere of trust, where your learners are free to share opinions and ideas. If you can achieve this atmosphere, you will have eliminated many of the barriers to effective learning. As facilitator, you will be concerned to balance the training content with the process dimensions of your learning group. In order to be fully effective, you will need to develop a good relationship with your learners and fully involve them in activities that facilitate learning.

There are six dimensions of facilitation that you may be required to perform during a training session:

- Planning: You will be concerned to clarify the aims of the learning and the goals. This will most likely be a joint activity

- Meaning: You will be concerned to ensure that participants understand what is going on, so that they will be able to relate it to their own experiences

- Confronting: This is a difficult task, but may be necessary. You may need to get your learners to face up to things that they generally tend to avoid. You will need to raise the learners’ consciousness of key issues

- Feelings: Learners will have feelings and emotions about the learning task, so you will need to think about how to manage them

- Structuring: This is a more formal dimension of your role as a facilitator, where you will be concerned with the structure and form in which the learning should take place

- Valuing: This dimension is concerned with attempts to build a supportive atmosphere. Your aim here is to ensure that participants feel empowered and that you are meeting their needs and interests.

Instructors are generally required to specify right or wrong. This is less likely to be the case with facilitation, where facilitators are usually required to give feedback on ideas, capabilities and behaviour – note, however, that this is less likely to be in a context where there is a need to specify a “one best way”.

In order for you to be an effective facilitator, you will need to be effective on the following competencies, which we address in this chapter, and have already addressed in Chapter Seven:

- Understand individual development and group processes and dynamics. You are less concerned with the subject matter knowledge that you possess

- You will need to understand where your learners are likely to encounter difficulties in learning and how you can facilitate progress

- You will spend a lot of time creating a positive environment for learning. You can achieve this by using some of the participative methods we considered in Chapter Six. Your aim is to develop a supportive, but challenging, relationship

- You will keep the learning process on track, using a combination of questioning, probing, challenging and feedback. Therefore, you will need well-developed interpersonal skills. To interact effectively with your learners, you will need to develop empathy, integrity, and responsiveness and be emotionally stable

- The flip-chart is central to your activities as a facilitator. You will use it to set tasks and summarise, and to get the learners to prepare their presentations. In this context, your skills in listening, questioning and challenging are also important

- You will need to be skilled to observe and respond with effective feedback, which is central to your effectiveness as a facilitator.

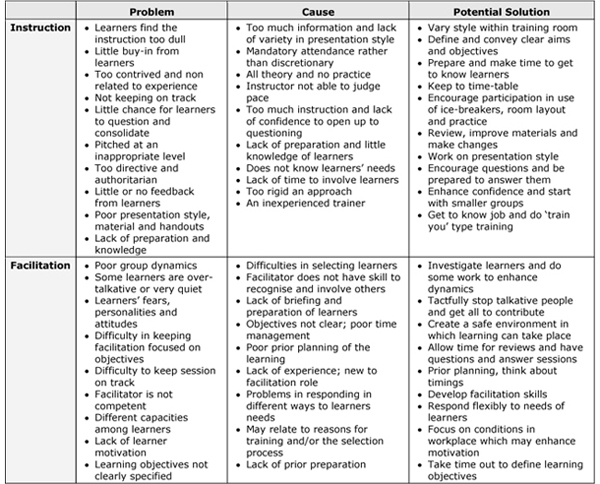

Figure 9.1 provides a summary of the problems that may arise when you are performing either of these roles and some of the strategies that you can use to deal with them.

FIGURE 9.1: PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED WHEN PERFORMING INSTRUCTION & FACILITATION ROLES

DEVELOPING EFFECTIVE TRAINING COMPETENCIES

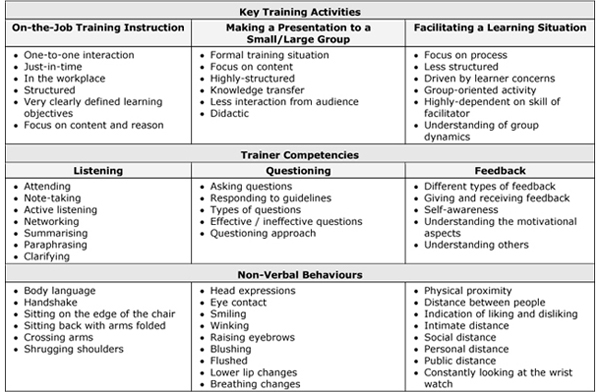

We have outlined the continuum of roles that you may be required to undertake in order to deliver training effectively in an organisation. We have made reference to a number of skills or competencies that you require to be effective. We will spend the remainder of this chapter focusing on three training situations and the competencies that you require in order to perform them. Figure 9.2 provides an outline of these training situations and the underpinning competencies.

FIGURE 9.2: TRAINING ACTIVITIES & ASSOCIATED COMPETENCIES

On-the-Job or Job Training Instruction

On-the-job training is distinguished from other forms of training in that it is:

- Carried out at the work site

- Delivered while the learner is engaged in performing work tasks and activities

- Usually conducted on a one-to-one basis between the trainer and the learner.

We make a distinction between unplanned and planned on-the-job training. Unplanned on-the-job training is ineffective as a training practice – research shows that people cannot learn a detailed task simply by watching others. If the training is unplanned, it is unlikely that it will be organised around what the learner needs to know and do. Learners who observe activities in a poorly-organised work environment will find it difficult to make sense of what they are supposed to be learning and/or understand how the various elements of a task fit together.

If you wish to conduct a structured on-the-job learning, it is important that you base it on a thorough analysis of the work and that you use a high performer as the basis for your analysis. You should use the results of this analysis to demonstrate to a trainee what to do, to tell them about the content of each task and why each task is important.

Organisations are increasingly using experienced employees to act as trainers. Therefore, it is important that you train the employee in how to be an effective trainer. It is also important that you tailor your approach so that the learner has an opportunity to watch or observe, to ask, then perform and solicit feedback. On-the-job instruction is usually conducted with a small number of trainees. It is likely to be, in many cases, a 1:1 situation.

The popularity of on-the-job training is primarily due to the many advantages it has over off-the-job training. We consider it to have five important advantages:

- The trainee learns the actual duties and responsibilities that he/she will be required to perform

- The trainee learns in the actual working environment

- Some productivity takes place during training (although low initially)

- A close bond between the trainee and trainer may be created

- The often-prohibitive costs of off-the-job training (travel, lodging, seminar fees, etc) are avoided.

For these reasons, it is not surprising that trainers look to on-the-job training techniques to satisfy most training needs.

The most common form of on-the-job training is job instruction training (JIT). This method became popular as far back as World War II. It involves you instructing a small group of trainees in the actual work environment on key skills and knowledge that are necessary to perform a task or job.

On-the-job training (OJT) is appropriate:

- When the employee is required to engage in performance immediately, rather than simply acquire information. You can use OJT to demonstrate to trainees how to perform a task in a work-setting, thus helping to reduce the transfer of training problem that is likely to occur if the training takes place off-the-job

- When time is a critical issue, or when you have limited time to organise effective off-the-job instruction

- When you have one trainee, or a small number of trainees, rather than a large cohort.

You should not use an on-the-job strategy, if there are health and safety issues in respect of the trainees or other employees. It is also unwise to use it where it may undermine a learner’s credibility with customers.

We propose a four step approach to job instruction training:

- Step 1. Prepare the Trainee: Important points you should remember when preparing the trainee for training include:

- Realise that the trainee may be anxious. Some anxiety is normal, although too much anxiety may hamper the learning process. Anxiety can be reduced by spending more time getting to know the trainee and assuring them that the objective is to help build skills and confidence. You can take other steps such as comfortable seating and lighting, creating a friendly atmosphere, smiling and using the trainee’s names, encouraging the trainees to talk and ask questions and demonstrating enthusiasm about the task you are to complete

- Find out what the trainee already knows about the job. Discuss relevant experiences the trainee may have had and determine how similar those experiences are to the job or task being taught. You should check the trainee’s current knowledge, identify any taps in knowledge and explore similar training or situations the trainees have experienced

- Put the training into context, by telling the trainees what the job/task is about. Explain how this job/task fits into wider work or the organisation / section and explain how the training relates to the job and other training sessions

- Let the trainee know what is expected, by explaining the desired performance level in straightforward and unambiguous terms

- Communicate the training plan. Let the trainee know what is in store for him/her (explain the training schedule, who will conduct the training, etc)

- Arouse the trainees’ interest, by explaining why this skill/procedure is so important and what the trainees will gain from acquiring it and by stating clearly the training objective, giving the trainees something to aim at

- Introduce trainees to all the materials, tools, equipment and new words they will encounter in the session.

- Step 2. Present the Training: The training can begin once the trainee has been prepared. Key points in this step include:

- Go slowly, and explain thoroughly each step, one element at a time. For each step, clearly state its importance

- Avoid unnecessary jargon and technical terms. Speak in terms that are easily understood and make sure everything you say is understood. Be receptive to any questions from the trainee

- Take your time. The trainee may be seeing the task for the first time. Train at a much slower pace than you would actually perform the task under normal working conditions

- Show the overall task. Complete the task following precisely the procedure you identified in your task analysis; put all the steps into context; give the trainee a mental picture of what they have to do; and talk to the trainee establishing the critical points throughout. Summarise at the end

- Stress the key points, correct procedure, and safety features. Relate what you are doing to the trainee’s past experience.

- Check understanding by repeating the task, with the trainee telling you what to do at each step. Ask questions that get them thinking. Check that they understand why you are performing in this order. Correct any errors as they occur and review the correct procedure. Encourage them to ask questions. Summarise the operation in a second run-through

- Repeat the job or task. Go through the task as many times as necessary to ensure that the trainee understands the process. Again, solicit questions from the trainee. Make sure the trainee understands there are no “dumb” questions.

- Step 3. Tryout: During this step, the trainee actually performs the task or job. Important considerations for this step include:

- Play a coaching role, while the trainee tries out the task or job. A good coach strives to build skill and confidence in the learner, and provide feedback throughout the task. Feedback should be both positive (when the learner does the task correctly) and developmental (when the learner is having trouble with a task)

- If the learner is having difficulty, use constructive criticism to overcome problem areas

- Do not let the trainee form bad habits. Even though different people may perform a job or task slightly differently, look closely for inefficient methods or procedures and correct them immediately

- Communicate with the trainee throughout the tryout. Ask questions to assess the trainee’s understanding of what is being learned. Again, solicit questions

- Part Practice: Let the trainee work through that stage. Have them tell you what they are going to do before they do it. Ask questions to establish they know why they are doing it that way. Encourage them to ask questions throughout. Give praise and constructive feedback. Have them to the task again, without having to tell you about what they are doing. Help them review their performance. Repeat the task with several different examples. Check their confidence and competence.

- Whole Practice: During this component the trainee completes the while practice. Help them review overall performance Return to part practice for areas that are incomplete or need special attention. Repeat whole task with several different examples. Repeat whole task with several different examples. Start with simple and work up to more difficult.

- Step 4. Follow Up: The final step of the JIT technique takes place when the trainee begins to perform the job or task independently. Your job as a trainer continues until the trainee’s performance continually meets expected performance levels. During this step:

- Remember that the trainee may run into unexpected problems. Be accessible and approachable

- Check back occasionally to make sure that things are running smoothly and to ensure that bad habits have not crept in to contaminate the learning

- Continue to give feedback to the employee. Let them know that you are receptive to new ideas and suggestions that may make the job easier or more productive

- Issue them with any notes or manuals

- Check whether they found any of the steps particularly difficult

- Ask for any questions on the process they have covered

- Identify to whom, and where, they can go for further help

- Summarise the whole process covered

- Point out that this is the best method from a number of possibilities. Explain why some alternative methods have been tried but rejected

- Check whether they have discovered any new or different techniques. Try out methods suggested by trainees. Do they produce acceptable results?

- Suggest that they keep an open mind about any possible improvements

- Briefly review the required job performance standards for time, quantity, quality and safety.

Making a Formal Presentation to a Small or Large Group

A second training task you are likely to perform is making a formal training presentation within the context of a training course. You are still performing in an instructor mode. We explain some of the steps that you should consider when enhancing your presentation skills. Mastering the skills to make an effective presentation does not come easily.

Generally, the more rehearsal, the better. One or two rehearsals is usually not enough to master new material. It is a good idea to rehearse the presentation under simulated conditions – in a similar room, with listeners who can give suggestions for improvement. Mental rehearsing, by running through the presentation and the scene in your mind, is also effective. You should time the presentation to determine whether it is necessary to cut or expand the ideas. We know, from research, that practising a training presentation for short periods of time over the course of several days is more successful in reducing anxiety and improving memory than concentrated practice. Distributed practice is more efficient and yields better results than massed practice when mastering your training presentation skills.

There are a number of issues that you should pay attention to:

- Practice Using Visual Aids: This will help you to get used to handling visual aids and give some idea of how long the training will take with the visual aids. You should prepare for the totally unexpected. Consider the situation where the roar of an overhead plane drowns out your voice? What if the microphone goes dead, a window blows open, or the room becomes extremely hot? Compensate for minor disruptions by slowing the rate, raising the volume a little, and continuing. You will encourage listeners to listen to your message rather than be temporarily distracted. For other disruptions, a good rule of thumb is to respond the same way you would if you were in the audience. Take off your jacket if it is too hot, close the window, raise your voice if listeners cannot hear you, or pause to allow a complex idea to sink in.

- Channel Your Anxiety: You should also think about how you will channel your anxiety as you practice. It is common for trainers to report feeling anxious before they speak, it is normal. To manage anxiety, you should channel it into positive energy. Prepare well in advance for the training – develop ideas, support them and practice delivery. This way, even if you are anxious, you will have something important to say. It may help to visualise the speaking situation by closing your eyes, relaxing and thinking about how it is going to feel and what the audience will look like as they watch. You should expect to feel a little momentary panic as you get up to speak, it will evaporate as you progress into the speech. But remember that anxiety about speaking never really goes away. Most experienced trainers still get podium panic. The advantage of experience is that it gets easier; trainers learn to cope by converting their anxiety into energy and enthusiasm, which gives an extra sparkle as you speak

- Convey Controlled Enthusiasm for the Training: Studies of effective trainers used adjectives such as flexible, co-operative, audience-oriented, pleasant and interesting. But only a few of these adjectives related to the content of the presentations. Enthusiasm is the hallmark of a good trainer. Learners will forgive other deficiencies, if you obviously love the subject and are genuinely interested in conveying that appreciation to the learners. Posture, tone of voice and facial expressions are all critical indicators of your attitude. Although enthusiasm is important, it must be controlled and should not be confused with loudness. Avoid bellowing or preaching at learners – it is enough that you can be easily heard and that your tone is sufficiently empathic to convey meaning effectively

- Delivery: Delivery should be used to enhance your training message and to maintain learner attention. Eye contact is the most important tool for establishing audience involvement, as it makes learners feel as if they are involved in a one-on-one, semi-private discussion with you. In Western culture, we value directness and honesty; one of the expressions of these values is direct eye contact.

You can enhance the overall quality of your training presentation if you follow a set of guidelines like the ones that we suggest in Figure 9.3.

FIGURE 9.3: GUIDELINES FOR TRAINER INTERPERSONAL EFFECTIVENESS

Facilitating in a Training Context

As you become more experienced as a trainer, you will most likely move away from an instructor style and perform a more facilitation style. Your role as a facilitator is to help the group to carry out an agreed task. You do not do the task for the group, but make it easier for the group to do its work.

The task in a group is a group task. The main difference between an individual tackling a task alone is that only the individual need relate to the task. In a group, each member has to relate to the task but also has to relate to every other member while doing so. In a group, many differences and similarities can exist – age, sex, background, culture, class, etc. To a greater or lesser extent, these differences and similarities can interfere with, or assist, the group in tackling the task. Group-members will be trying to work at the task, while at the same time trying to have their needs met arising out of the differences and similarities – for example, need to be accepted, to dominate, to complete, to assist, etc.

As a facilitator, you have to be aware of the task that the group has undertaken and at the same time be aware of needs that members have. These needs must be acknowledged and responded to in order that the task is done. To be effective in conducting a facilitated session, there are five practical functions that you should complete:

- Space: As a facilitator you are the person responsible for ensuring that the space where the group will work is in order – enough chairs, light, heat, etc

- Helping the Group to Settle: Your task is to help the group to feel secure enough to be able to tackle the task. You may do this by breaking some of the barriers and helping to build a climate of trust – introductions, a brief comment from each, an ice-breaker, etc. You must demonstrate consistently that you accept each member and trust the group to complete the task

- Ensure that the both Task, and Constraints, are clear: At the beginning of the group session, you should help the group to be clear about the task and the time-frame within which the task has to be achieved. Is the task to share experiences, explore attitudes, arrive at a decision, plan an action, present a proposal? Each member has a contribution to make, so time should be thought of as a shared resource

- Direct/Facilitate the Discussion: This is your main task and it is during the discussion that a range of skills is helpful, including your ability to listen, clarify, empathise, challenge, support, summarise, and question

- Manage Time: You need to help the group to be aware of time as the discussion continues, so that the task is complete within the time allotted.

Some Skills to Ensure Effective Facilitation

To be an effective facilitator, there are a number of important skills that you are expected to use, including:

- Listening and Empathy: Learners need to feel they are being listened to and that their ideas and concerns are recognised as worthy and important contributions. You need to listen attentively to all participants, maintaining eye contact with each speaker; contributions need to be responded to and perhaps recorded for all to see. Discussions need to build on earlier statements; if they do not, it may be helpful to summarise the points, which have been overlooked. It is also essential that you avoid discrimination and, for example, develop alternatives to the exclusive use of male pronouns (he, his, him) – such as ‘he or she’ or alternating use of male and female – in written and oral presentations. This can be essential to the trust and safety of some learners whose contributions are especially important to obtain because they have been systematically ignored in the past, in other settings, if not in the group at hand. Confidentiality is another issue that influences trust levels – if personal histories or opinions are aired, it may fall to you to make sure the learning group agrees about what “confidential” means in this case

- Validation: Learners need to feel validated as equal and important members of the group. You should not be the only one who generously (but honestly) offers comments like “I’m glad to see you here” or “I like that idea”, etc

- Acceptance: Learners need to feel accepted. You should provide opportunity for everyone to introduce himself or herself, if they are not familiar with each other. It is not enough for you alone to know everyone’s names and personal background

- Trust and Safety: Learners need to feel a sense of trust and safety in the group. It is especially important that negative comment be interrupted by you (or other group members). Non-verbal behaviours can communicate a “put down” too; not looking at certain people, or looking bored, can hurt more than words. Butting into a discussion before someone has finished undermines trust; so do side conversations. Comments that imply the superiority of one sex, race, economic class, ethnic group or age group over others are destructive of trust and safety, even though the victim of the remarks probably will not feel safe enough to express the hurt. The learner will probably have intended no harm at all; nonetheless, you should be prepared to interrupt such remarks, tactfully but promptly and firmly

- Participation: Learners need to feel that they are able – and expected – to give suggestions, to lend support, and to take the initiative. It is very difficult to learn how to be a more effective participant in social issues, if training activities encourage passivity. In order to counteract the passive model of learning, which comes from years of sitting in lectures, you need to be encouraging, appreciative and welcoming of each learner’s contribution

- Ask for Help: For most adults, groups have a competitive atmosphere, which make it unsafe to admit that they need help. But the success of a learning group depends on the success of every member in developing skills. So it is essential to be able to ask for help when it is needed, for encouragement when an activity seems difficult or challenging and for appreciation when there are new accomplishments. You can help by modelling these behaviours (by doing them yourself for all to see) or by making a statement encouraging learners to ask for help

- Life Experience: Learners need to know that their life experiences are an important and valuable resource to be drawn upon and shared for their own learning and the group’s learning as well. In particular, those people with less formal education need to be reassured that what they have learned through experience is just as valid and worthwhile (it may be helpful to say this explicitly). Activities and discussion questions should invite sharing of experiences

- Free Release of Ideas: Learners need processes that allow for the free release of their feelings and thoughts. Again, a well-planned activity will provide encouragement for this, with plenty of time for discussion. Activities are the stimulus and the shared experience provides a basis for focused discussion and decisions about how to implement new procedures or ideas

- Humour and Fun: Learners need an atmosphere where they can be taken seriously, while at the same time allowing for laughter, humour, errors and flexibility. Lightness and fun have an important part to play in learning; if people are enjoying themselves, they are also probably open to new ideas. If they are feeling comfortable enough to risk making mistakes, they are likely to experience much more rapid learning

- Resolve Conflicts: Learners need processes that allow for resolution of conflicts without somebody winning at another’s expense. When you identify a situation in which two learners’ ideas are in conflict, it is usually not good enough to point to a “right answer” – it is important to recognise the valid components of the other answer and to strive for a solution that taps the best of both learner’s ideas

- Evaluate Learning: Learners need the opportunity to evaluate their learning and express their satisfaction, dissatisfaction or suggestions for future improvement. This is one of the most important ways in which the learners can take charge of their own learning by guiding the development of future learning plans. Accomplishments deserve to be shared and frustrations need to be communicated, rather than being turned back in on the learner

- Worthwhile Activity: Learners need to feel they are engaged in a meaningful and important activity. In school, we were expected to take it on faith that what the teacher had to say was important. However, in the workplace, it is essential to explain the purposes of learning activities and useful to allow participants to question, clarify and even change the purposes at the start of an activity to ensure that they are motivated and committed to the activities

- New Ideas: Learners need to develop new ideas about the facilitator/participant relationship. In school, the teacher determined content, directed learning, maintained discipline and judged performance. The teacher was older, stronger and usually wiser. There is a tendency to expect the same of facilitators, even if that isn’t appropriate. The facilitator may have chosen the content, but with group input about needs, objectives, and preferred methods. The facilitator creates opportunities for the group. Rather than presenting an image of someone who knows it all, the facilitator can be someone who is eager to learn, with a lot of good ideas about how to learn, where to find out, and how to acquire new skills

- Mutual Responsibility: You and your participants share a mutual responsibility to achieve the desired learning. You can emphasise the democratic nature of learning and can help participants be aware that they are in charge of their learning, that it is their business being conducted, and that each person has contributions to make. You may find times when participants are effectively taking control of their own learning, so that you can literally slip into a back seat or become another participant, in the interest of building independence among the learners

- Overcoming Old Patterns: Learners sometimes need help to overcome old patterns of passivity and feelings of inadequacy. In a discussion session, ask for the thoughts of those who haven’t spoken yet or set a guideline from the beginning that no one speaks twice until everyone has spoken once. It may help to check out in a 1:1 the concerns and reservations of those who hold back

- Relating to “real” situations: Learners need to know how a learning activity relates to “real” situations. Even if the learning activities use the actual problems and situations that the group is confronting, it is important to help participants make their conclusions explicit. This can be done in discussion sessions by raising such questions as “Exactly how will we use the ideas that have come up today?” or “Are we willing to try this new procedure on a regular basis?”

- Check for Attention: Even the best of learning plans will not hold the attention of participants 100% of the time. You can use the attention level as a gauge of how well things are going. When energy droops and people begin to fidget, it is a signal to check whether things are repetitive, off the point or boring. You can also ask the group what is going on. Usually, learners will know what’s up and take the question as an indication of your respect for them, a reminder to them that they can share the situation to meet their needs. Raising the question implies a willingness by you to be flexible – to change the schedule activity, to have a break, to make (or elicit) a summary of what has just happened or to lead three laps around the building

- Locating Learners: Learners need to understand where in the planned sequence of activates the group has reached. An agenda should be posted and/or distributed, explained and referred to periodically. This can help to reduce feelings of being lost and also helps the participants to decide when it is most appropriate to raise a particular question or concern

- Learners in Control: Learners need to have real control over how they spend their time. The agenda should include time estimates for each activity. If necessary, these times can be debated or reviewed at the start. A time schedule is only helpful if it is used. You need to keep an eye on the clock or appoint someone else to do this. If an activity looks like it will run over time, the group should have the opportunity to decide whether to cut it short, drop a later item, or extend the session to include everything. You should try to make realistic time estimates for learning activities, allowing adequate time for the sort of discussion that allows participants to understand and incorporate new skills and information. To some extent, you can move things along and keep discussions tightly focused, but decisions to run over time or omit parts of the agenda should be made by the group. If a sessions are on a tight time schedule, it may be useful to time individual contributions to a discussion.

DEVELOPING YOUR QUESTIONING SKILLS

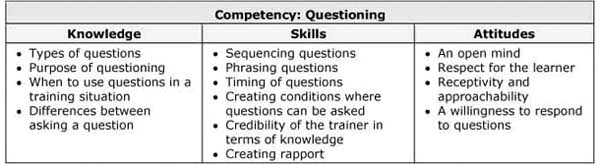

We have discussed three training tasks that you may be requested to undertake from time to time. We have made reference to specific skills that you will need to possess in order to carry out these tasks effectively. We now explain the role of questioning skills and a range of questioning techniques that you can use. In Figure 9.4, we set out the key elements of the questioning competency.

FIGURE 9.4: QUESTIONING: ASSOCIATED KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS & ATTITUDES

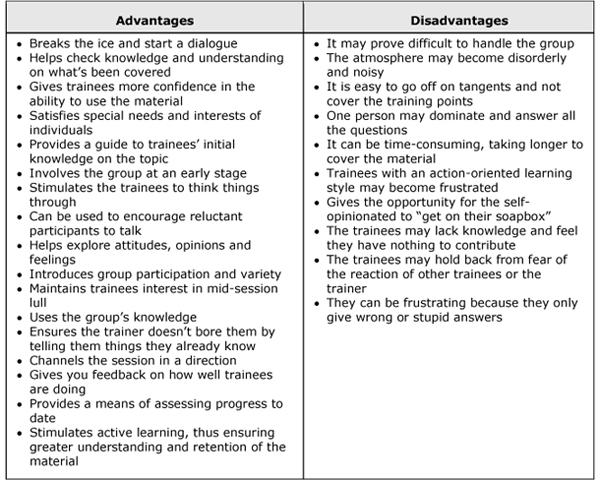

Why Use Questions in a Training Session?

We propose that competency in asking and responding to questions is important for a number of reasons. We also highlight some of the issues involved in practising this competency effectively. Figure 9.5 provides a summary of the advantages and limitations in using questions in a training session.

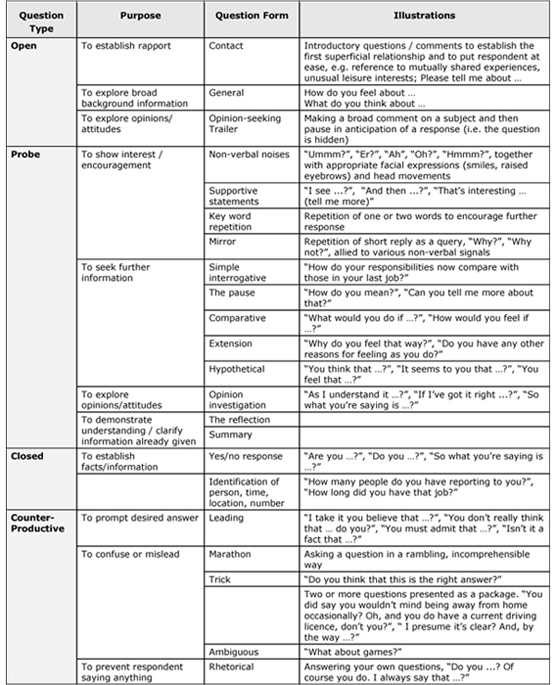

Types of Questions that you can use during a Training Session

To be an effective trainer, you must learn to question for understanding. You must always be an observer of the trainee’s behaviour and be willing to “check out” the trainee’s emotional state and measure learning. The following questioning techniques can aid you in assessing the progress of learning. They are presented in Figure 9.6.

FIGURE 9.5: USING QUESTIONS IN TRAINING SESSIONS: ADVANTAGES & DISADVANTAGES

FIGURE 9.6: DIFFERENT QUESTION TYPES IN TRAINING: PURPOSE & FORM

We will now talk about some specific questioning approaches that you can use in a training situation. You can use the following question formats to enhance the quality of the learning event:

- The “To the Group” Question: In this situation, you ask a question and then wait for an answer from the group. This allows the trainees to think and encourages involvement in the learning process. If there is no immediate answer, you should not rush in; sometimes, a pause is useful and silence has the potential to stimulate the thinking process. If you do not get a response, then ask a direct question of some member of the group

- The Direct Question: You can throw out the person’s name and then ask them a question. By stating the name first, you ensure that you get their attention

- The Combination Question: This question is useful to gain the training group’s attention, so you ask the question of the group, then give the entire group time to think and then name a specific participant to answer it

- Closed-Ended Questions: These questions require an answer consisting of a yes/no or a single word response from the trainee. Closed questions save time and direct trainees to a single answer – for example: “Do you know how to start up the Aligner?” or “Do you know the safety requirements for this module?”

- Open-Ended Questions: These questions require an answer longer than a yes/no or single word response. In general, more information is gained about what the trainee does or does not know by asking open-ended questions. For example: “What are the steps to start up the Aligner?”, “What are the consequences of not following the safety requirements?”, or “What is the purpose of the task you are presently doing?”

- Follow-Up Questions: Quite often the trainee finds a way to leave you wondering whether they really understood the subject. Follow-up questions help you, and the trainee, understand more about what the trainee knows. Here are some examples: “What do you mean when you say …?” or “How do you know that’s true?”

- Redirected Questions: These questions are questions that are asked by the trainee to you, where you then relay the question back to the trainees. This challenges the trainees’ willingness to engage in a critical thinking process

- Probing Questions: Information given by trainees may need to be explored in more detail – make sure that you probe further if you are not clear about an answer. “How many sessions have you carried out?”, “Are you responsible for all aspects of training?”, or “What responsibility do you have for testing understanding?”

- Comparisons: Getting trainees to compare their experience in different training situations is often very useful. “What are the major differences between working in the sales department rather than in production?”

- Behavioural Questions: You may pose this type of question to yourself or the group – for example, what would you say or do in particular situations. Be specific. “When one of your trainees performance deteriorated, what did you do?” or “What did you do in your last job to contribute towards teamwork?”

It is important to emphasise that the ultimate purpose in posing questions is to receive an answer and to lead to a wider understanding by the learners. The objective is not for you to impress the group with the extent of your knowledge, nor to highlight the lack of knowledge on the learner’s part. Questions should be framed in a way that do not embarrass or threaten a learner.

Some Appropriate Questioning Techniques

There are a variety of ways of not asking questions in a training context but the three most often encountered are:

- Creeping Poison: This is where questions are asked in sequence around the group so that an individual can predict that a specific question will be addressed to them. This is an inadvisable method, because it leads to increased pressure – group members can become so preoccupied about the question that they will face that concentration becomes difficult as they await their turn under the spotlight. Additionally, those who have already answered a question may feel that they need not pay attention since the danger of being asked an additional question has receded. However, the advantage of sequential answers is that everyone has an equal opportunity to answer questions and that no one is overlooked or victimised

- Heart Failure: Sometimes referred to as “3P” questioning, which stands for “pose, pause and pounce”, “Heart Failure” is the opposite of Creeping Poison. This is where a trainer questions individuals in the group without any prior warning. The random nature of the questioning technique means that the group has to “keep on its toes” and pay attention; the disadvantage is that the pressure of being put on the spot can result in blind panic, the mind going blank, or an ill-considered or garbled answer

- Popcorn Questioning: Popcorn questioning is less direct and so a less threatening method of questioning. In this approach, you pose a question to the whole group and, as with popping corn, allow the group to heat up gradually, answering questions as soon as they feel confident to do so. By providing the right environment and encouraging a response, answers should be “popping up throughout the group”. Popcorn questioning is useful where individual group members may feel inhibited or where the intention is to enhance team spirit and gain greater participation. The approach is less formal but care must be taken to avoid the same people answering questions each time.

Responding to Answers Provided by Learners

Skill in framing questions in the right way is only part of your skill in questioning in a training context. The second major factor is in responding to the answers that learners give.

When an individual answers a question, it is important for you to realise that the group will be looking at how that answer is received and how they would feel if they were in the respondent’s shoes. Insensitivity on the trainer’s part in handling responses can discourage the group from any further participation. How you react to answers and then respond to them is an important component of your questioning competency. You need to:

- Acknowledge every contribution: Every response deserves some acknowledgement. Ignoring a contribution is an indication that the response was unworthy of comment and will discourage that person and the rest of the group

- Always acknowledge answers immediately: Whether the response is correct or incorrect, you should always acknowledge immediately. Failure to do so could result in learning points being missed or incorrect responses being assumed to be correct

- Acknowledge correct responses: Where the response provided is what was required, you should commend the responder, repeat the answer given and emphasise or expand upon the issue, moving on to further questions if appropriate. For example, “Thank you John. That’s an excellent point. Financial considerations are not the only factor; human factors must also be taken into account. Can anyone think …?”

- Broadly correct responses: If the answer given is broadly correct, emphasise the correct elements and seek further information about the remainder. For example, “Yes, the cost element is one factor here but are there any others we need to consider?”

- Do not dismiss incorrect answers: You should not dismiss incorrect responses without due consideration. Try to find something in the answer given that could be of merit. One approach is to acknowledge the answer given, explore the reasons for reaching that conclusion and/or empathise with the respondent. Then either (1) re-state the question to provide an opportunity to the individual to correct that answer or (2) put the answer given, to the group for comment – for example:

- “Michael, I can understand why throwing complaining customers out might be one way of dealing with the problem but do you think it would provide the best approach to handling customer complaints?”

- “So, Michael, your suggestion would be to throw complaining customers out to discourage further customer complaints. Does the group agree that this would be the best approach to handle customer complaints?”

- Where the answer doesn’t make sense: Many learners understand the question asked, but find it difficult to put their thoughts into words. If the problem seems to stem from the inability of the learner to articulate their thoughts, the solution might be to help clarify the underlying meaning and check back. For example: “Alan, if I understand you correctly, you would want to see more involvement, is that right?” The objective is to clarify or paraphrase the individual’s ideas, not to ignore them and impose your own

- Where the response is completely irrelevant: In some cases, the answers given seem to bear little resemblance to the question asked. Before you start to question your sanity, or that of the group, you should check that the question was understood and, if not, re-state it in a clearer form. The cause might be that some trainees are answering a question that they think you ought to have asked or that they believe you will be asking. In other words, their thoughts have outraced the issues under discussion. A response to this would be to thank them for their contribution and indicate that the topic will be covered at a later stage or that it touches on matters outside the boundaries of the present topic. Such as, “Thank you Derek , but you are way ahead of me. That’s a good point that we will be pursuing later. Could you make sure that I cover it when we look at the topic in the next session?”

As well as being able to ask questions, effective training requires that you are able to answer questions too. It is always a wise idea to establish at the outset when you intend to deal with any problems or questions and, providing the group is made aware of the approach that you will be using, this is largely a matter of personal choice.

There are a number of reasons for asking a trainer questions. The most obvious reason is to seek an answer to a particular issue:

- Genuine request for information: If the question is a genuine request for information, you should answer it concisely and check with the questioner that this provides an answer that meets their needs. If further clarification is required, this can either be given instantly, or you can suggest that the matter could best be discussed during a suitable interval

- Testing credibility: The object of asking a testing question is not about understanding but to probe your knowledge and expertise. Often, the questioner already knows the answer but wants to see how you handle the question. If this is the case, your credibility depends on your honesty. Trainers are not expected to be the fountain of all knowledge but it is often felt that, if they admit that they don’t know, they will lose all credibility. This is not the case: It is infinitely better for you to remain silent and be thought a fool than to open your mouth and prove it beyond all doubt. If you don’t know – you shouldn’t bluff. If you fake an answer and are found out, it will cast doubt upon everything that has been said so far. On the other hand, if you are confident enough to admit that you don’t know, this implies that you feel sure of the accuracy of everything else you said. Providing the questioner doesn’t seek basic information that you should know, the best approach is for you to congratulate the questioner on raising an important issue, admit that an answer does not readily spring to mind and promise to provide a definite response tomorrow, or after the course or later on (you must ensure the promise is fulfilled). The rule here is “if in doubt, find out”

- Displaying knowledge: The purpose of the display question is to impress upon others how knowledgeable the questioner is. All the learner is looking for is confirmation of your intelligence in front of the group and, providing the facts are correct, you can win them over by flattery. “Now that’s an interesting question”. If the information is not accurate, you need to take considerable care to reinforce those areas that might lead to misinformation

- The sidetracking question: The objective of the sidetracking question is to move the learners’ attention into an area that holds greater interest for the questioner. This might be deliberate or unintentional but, in either case, you should resist the temptation to be led off the track. For example, “We will be looking at just that problem tomorrow morning, Rose, so it might be better to save that question for then”

- Challenging questions: Sometimes referred to as the “Gotcha question”, it often takes the form of using information provided by you earlier to contradict the views currently being stated. Your response in this situation is very important. The rule here for you is to never take the criticism or challenge personally, even if (or particularly if) it is meant that way! The correct approach is to pause, admit that the point is an interesting one, and use the time gained to think carefully about your response. If you can’t justify what has been said, then do not try to. Defending the indefensible will mean that, far from winning the person over, you will convince the rest of the group of the validity of your concern. Instead, you should admit your mistake and emphasise the correct solution. Equally, if there is a good reason for the inconsistency of the answers, you shouldn’t use this as an opportunity to score points. If you belittle the questioner in front of the group, at best he will be alienated, at worst he will seek revenge later. You should demonstrate that you are above such things and thus you will gain the respect of the whole group.

Some of the guidelines you can follow when asking questions are presented in Figure 9.7.

FIGURE 9.7: GUIDELINES WHEN ASKING QUESTIONS IN A TRAINING CONTEXT

- Make sure that the question is clear: It is impossible to answer anything correctly if you don’t understand the question. Jargon and technical language should be avoided, which might not be understood and the question phrased unambiguously

- Keep it short: There is little point in asking a question so long-winded or confusing that the respondent has to ask for it to be repeated. Where a question is complicated, it should be broken down into digestible chunks

- Keep it fair: The person questioned should be able to answer the question from the knowledge gained on the course or from knowledge he could reasonably be expected to have already.

- Do distribute questions evenly: The question should be tailored to suit the person questioned. Part of keeping it fair is making sure that individuals don’t feel that they are being victimised and that questions aren’t always addressed to them. Questions are occasionally used as a method of keeping particular group members alert and under control. Although this is an acceptable approach, it should not be carried out in a manner that leaves anyone feeling “picked upon”

- Don’t ask 50/50 questions: Ask questions that require an answer to be thought out, and not just guessed at. Avoid questions like “Which would you press, the red button or the blue button?”

- Don’t ask vague questions: Questions like “What is the first thing you would expect to see in any office?” are too broad to be of any value. Questions should be precise enough to indicate the knowledge required to answer correctly

- Don’t seek public confessions: It is unfair to expect a response to questions such as “Has anyone here ever been ill through stress?”. Questions such as “What sort of illnesses can be attributed to stress?” or “What sort of effects can stress produce?” will often result in a wider and more enthusiastic response

- Don’t ask questions reminiscent of the classroom: Classroom questions are those questions that can be completed in one word, such as “We call this a ...?” with a pause for the group to provide a response

- Don’t answer the question: Trainers are often so concerned that they won’t get the answer they want (or worse yet, any answer at all) that they finish up answering the question themselves. You shouldn’t give up too easily. If the group does fail to react, it might be that they don’t understand what is being asked, so you should phrase the question in another way.

USING LISTENING TECHNIQUES TO DELIVER EFFECTIVE TRAINING

Your second core competency is listening. Your purpose in listening is to make a conscious effort to hear what is really being said, with the intention of creating connection with the trainee and diagnosing their current emotional state. Listening requires you to:

- Be open to discovering the trainee’s true meaning

- Facilitate the trainee having the experience of “feeling” heard and understood.

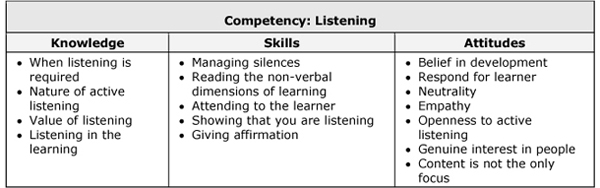

Listening is a skill you will use quite a lot when facilitating. In Figure 9.8, we set out the key elements of the listening competency.

FIGURE 9.8: LISTENING: ASSOCIATED KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS & ATTITUDES

It is generally considered that trainers are poor listeners. Research suggests that they test in the low 25% of skilled listeners. They are likely to immediately forget 75% of what another person has said. Reasons for not being skilled listeners include:

- A lack of formal training in listening

- A historical awareness that trainers get the attention and that talk is power (listening, therefore is not thought of as powerful)

- A tendency to use spare auditory/thinking capacity inappropriately

- Concentration is blocked due to “external” barriers

- Receptivity is blocked due to “internal” barriers.

Defensiveness leads to ineffective communication. Therefore, it is very important that you build and maintain a supportive climate for communication. Supportiveness can be increased where you:

- Indicate your desire to understand and gain more information

- Take a problem-solving approach instead of a judgmental one

- Are spontaneous and direct

- Express empathy

- Have an open attitude and are willing to experiment with ideas, attitudes and behaviours.

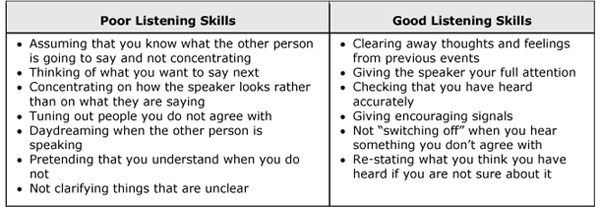

Figure 9.9 sets out examples of good and poor listening in a training context.

FIGURE 9.9: EXAMPLES OF GOOD & POOR LISTENING BEHAVIOUR IN A TRAINING CONTEXT

The following represents a model that you can use to facilitate listening in a training situation

- Step 1: Consciously decide to do the work of Power Listening: Focus 100% of your attention on the learner. Shift physical position so that the learner can access all the information they need. Make eye contact and be in a position to observe the learner’s body language. Separate from external distractions such as the phone, beeper, and tools or work the learner is currently engaged in

- Step 2: Suspend your “internal” judgements: Temporarily let go of your assessment of the learner or the subject matter. Put him/herself in the other person’s position. Be willing to ask “What if he/she has a valid point?”

- Step 3: Scan for the “unseated” message and other clues: Pay attention to the learner’s non-verbal clues, to determine the underlying meaning in the message. Scan regularly for: pauses in breathing; eye movement; emotion; voice level and tone; facial expressions; intuition

- Step 4: Ask clarifying questions: Ask open-ended probing questions that will assist him/her in getting beyond the surface meaning. Whenever your intuition says “there’s something more here” or “there’s something which isn’t understood”, you should be willing to ask questions like: “What exactly did you mean, when you said …”

- Step 5: Summarise understanding of the learner’s “true” message: Endeavour to capture understanding of the “true” message in one straightforward and focused sentence. Deliver it as an open-ended question, such as: “It seems as though you felt embarrassed by not performing the process correctly yesterday and now you are reluctant to learn today’s objective. Is that correct?” If you have captured the essence, the learner will feel assisted, as well as listened to. Even if you are off the mark, the learner will answer the question in a way that will take you closer to the truth.

Active listening requires the possession of a number of important skills, as well as the avoidance of pitfalls. The more important dimensions of active listening are presented in Figure 9.10.

FIGURE 9.10: ACTIVE LISTENING: SKILLS & PITFALLS

USING FEEDBACK IN A TRAINING CONTEXT

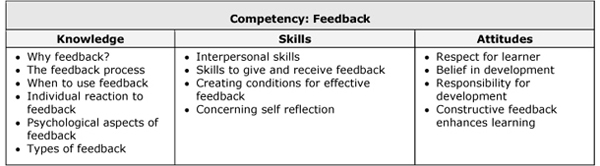

The third core competency for effective training is giving and receiving feedback. The purpose of effective feedback is to build and maintain relationships with learners and to promote learning. In Figure 9.11, we set out the key elements of the feedback competency. Feedback is a competency that you will use a great deal in conducting on-the-job instruction or in facilitating.

FIGURE 9.11: FEEDBACK: ASSOCIATED KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS & ATTITUDES

Feedback is information about the results of someone’s actions. The purpose of feedback in a training context is to build and maintain relationships with learners and to promote learning. Immediate and direct feedback can help you to:

- Acknowledge and reinforce behaviour that meets the job requirement expectations

- Negotiate for a change in behaviour that does not meet the job requirement expectations.

Trainers often fail to give learners honest, direct and descriptive information on how their behaviour impacts on the success of the training. Consequently, learners do not know how others feel, and trainees and trainer do not learn how to interact with each other more effectively. Without feedback, the trainee will not know how they are doing. Without feedback, you cannot make improvements to the material or delivery. When giving feedback, you should:

- Give acknowledging feedback and reinforcement for something well done

- Acknowledge trainees’ responses, whether correct or incorrect, as attempts to learn and follow them with accepting, rather than rejecting, comments

- Reinforce or reward responses with a smile, a favourable nod, and a little attention

- Provide a tangible token for successful completion of a particularly difficult or time-consuming task

- Provide enough “marking off points” that trainees will know where they are in the training and how they are progressing.

You need to avoid situations where you:

- Cause a learner to feel humiliated or embarrassed. It can make a trainee “shut down”, lose enthusiasm or stop learning

- Publicly talk about your trainee’s progress

- Compare one trainee to another

- Laugh at a trainee’s efforts

- Tell the trainee by word or deed that their questions are stupid

- Assume the trainee is not as capable as you would wish. Using statements like: “You couldn’t possibly understand the answer to that question”

- Chastise your trainee for failing.

Some Feedback Techniques for Trainers

There are many different ways to give trainees feedback. The use of feedback is dependent on the type of training situation you are conducting. You will be required to give lots of feedback in a facilitation situation. There are various approaches, but the following can be effective :

- Immediate Verbal Feedback: Typically used in 1:1 training situations where you have the opportunity to deliver the feedback personally to the trainee. Immediate feedback needs to be delivered for acknowledging and reinforcing actions. This can take the form of a smile, a nod, a “good idea” comment, and so on. It is important that you are consistent and acknowledge performance, so that the trainee will feel successful and build confidence. It can be detrimental to a trainee to be ignored or passed over when they have contributed during the day. Immediate feedback needs to be given on a regular basis throughout the entire training session. If trainees are not doing what they should be doing, they need to be informed up-front. Do not save everything until the end. Clear things up as you go. Whatever the feedback, let trainees know where they stand.

- Written Feedback: While verbal feedback is the most effective feedback in a training situation, because it gives the trainee an opportunity to ask questions, it takes a considerable amount of time. Written feedback is an alternative. Criteria for written feedback should be determined by you before the session and communicated to the trainee at the beginning of the lesson. Written feedback needs to be accurate and specific to the topics outlined in the training.

There is evidence that trainers often fail to give trainees feedback for the following reasons:

- Lack of formal training in observing and becoming aware of the interpersonal dynamics of a training situation

- History of receiving poor feedback when the content of the message was personal and intended to be punishing or corrective

- Tendency to think of feedback as either “positive” (the good news) or “negative” (the bad news). This results in trainers wanting to avoid the negative feedback or viewing it as unhelpful. Surprisingly, many trainers also avoid or “brush off” the positive feedback, by saying “I was just doing my job” or “It was nothing, really”

- Fear that a trainee’s feelings may be hurt

- Fear that the trainee will get angry and disrupt the training.

Whatever feedback you provide in the training content should be:

- Helpful: The bottom line is that the purpose for giving feedback must be to build an effective training relationship; it must be helpful not just for you, but for learners as well

- Appropriate: The subject of the feedback must be within the context of the training programme itself. A good common sense rule is to ask the following question: “Does this behaviour have something to do with the training relationship?”

- Well-timed: Feedback is most effective when given at the earliest available opportunity. It is important not to let too much time elapse and not to let feelings or emotions build up

- Solicited: In an ideal situation, it is far better for feedback to be solicited, rather than imposed. When the receiver of feedback has given permission, they are more open to hearing the information. It is even better when the method for giving and receiving feedback has been formally established between the trainee and trainer

- Accurate: It is imperative that the information about the behaviour be descriptive, specific, verifiable, and neutrally presented. You should describe the actual behaviour with facts and information that will allow the receiver to verify the event, actions or words said

- Personally-owned: The behaviour itself can be interpreted several different ways, depending on who observed it and their values, beliefs and experiences. Therefore, it is important for the feedback to be personally “owned” by the giver as their unique response to the behaviour.

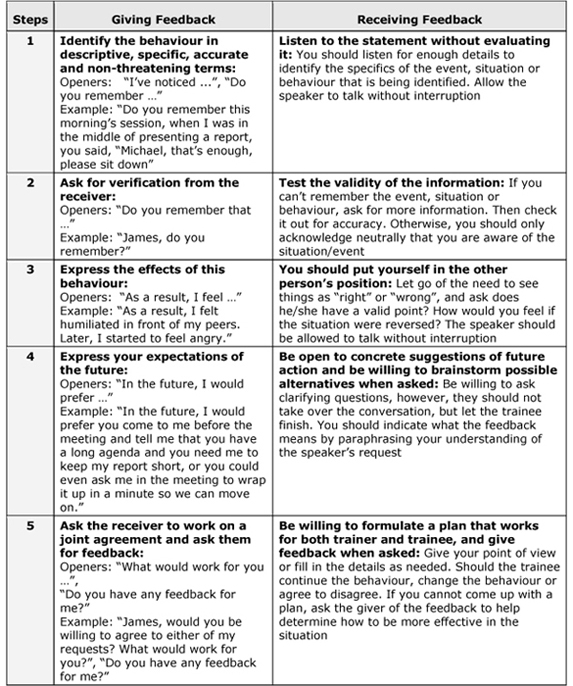

Figure 9.12 presents a model for giving and receiving feedback.

FIGURE 9.12: A MODEL FOR GIVING & RECEIVING FEEDBACK IN A TRAINING CONTEXT

USING NON-VERBAL COMPETENCIES IN A TRAINING CONTEXT

We consider non-verbal competencies to be an important dimension of effective training, underpinning the three previous competencies we have discussed. Although you communicate with your voice, you also communicate with your whole body. Non-verbal behaviour represents a powerful communication tool. Research reveals that only 7% of the meaning participants derive from a trainer’s message comes from what is said; 38% is derived from voice and 55% from body language. Gestures, mannerisms, and expressions can have a major impact on the receipt and understanding of a message.

In Figure 9.13, we present the key dimensions of the non-verbal communications competency.

TABLE 9.13: NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION: ASSOCIATED KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS & ATTITUDES

Competency: Non-Verbal Communication |

||

Knowledge |

Skills |

Attitudes |

|

|

|

Receipt of a Training Message

It is impossible for people to learn when they are nervous, and equally it is impossible for trainers to teach when they communicate nervousness. This does not mean that trainers must avoid training until such time as you can do so without a degree of stress; an element of tension is essential and inevitable in many training situations. What it does mean, though, is that the effective trainer must aim to look relaxed and be in control, even when the reality is a little different. You can do this in a number of ways

- Smile: The simplest and most effective way of demonstrating that you are friendly and approachable is by smiling. This should be a natural relaxed smile, not a nervous giggle, and certainly not a maniacal grin, which makes trainees wonder what is in store for them. The less relaxed you feel, the more important smiling becomes

- Handshakes: Handshakes are a conventional means of breaking down barriers. Your handshake should not be so flaccid that it is asking the participant to shake a wet fish, nor so firm that it becomes a trial of strength

- Posture: The way in which you stand can also provide a very clear indication of the way you are feeling and should indicate that you are in control

- Demeanour: Your whole approach should be one of openness and assurance. Being self-assured is not the same thing as being conceited. Nothing said or done should make trainees feel inhibited, embarrassed or patronised

- Appearance: It is often said that first impressions are lasting impressions and that you never get a second chance to create a first impression. When trainees attend a course, they generally have formed some opinion of what they expect to see. Appearance will form an integral part of this expectation.

Understanding the Training Message

The clarity of your training message being communicated, and the conviction with which it is received by others, can be significantly influenced by the non-verbal signals transmitted during the presentation.

Eyes

The eyes are the most conspicuous channel of communication. In normal conversation, the parties communicating will maintain eye contact for 25% to 35% of the time, and their eye blink rate will be approximately once every 3-10 seconds. During group training, eye contact reduces dramatically and the blink rate increases.

However, listening conventions suggest that eye contact and active listening work in unison. People assume that, if someone is looking at them when they are talking, then that information is intended for them. If, on the other hand, their eye contact is elsewhere, it is felt that the speaker and their message can be disregarded.

This can frequently be seen in group training sessions where a question is addressed to the group and eye contact is made with the group as a whole. The result is a delayed response or no response at all. If the same question is asked while looking at an individual, that person will feel compelled to answer or acknowledge it.

If eye contact is so crucial, why do so many trainers find it difficult? The answer undoubtedly is that because it is so powerful a gauge of feelings that people instinctively avoid eye contact in case others see how nervous or anxious they really are. In actuality, this absence of eye contact confirms that the avoiding party is scared. Gaze behaviour of influential personalities shows that they make more frequent eye contact and hold this contact for a great deal longer than normal.

Far from interpreting the lack of eye contact as diffidence on your part, trainees will see it as demonstrating a lack of confidence, an intention to hide feelings or some form of deceit.

Arms and Hands

Possibly the greatest difficulty you encounter when presenting material is what to do with your hands. In normal conversation, hands might not merit a second thought but somehow, in making a presentation, hands suddenly seem to acquire the capacity to move independently of the rest of the mind or body. They can be seen tying themselves into knots, ferreting about in pockets and discovering nasal orifices they would not dream of exploring ordinarily in polite company.

What is it that causes this transformation? Nervous tension results in excess energy to the system, which needs to find a satisfactory outlet. In the absence of any obvious opportunity to work off this energy release, the body uses the only alternative available, which is to seek out something to toy with.

The following hand movements should be avoided:

- Grooming: There is nothing intrinsically wrong in ensuring one’s tie is straight or hair is in place. However, continuous patting and primping becomes irritating

- Fiddling: As a rule, this involves small objects such as buttons, watches, and rings, though other forms include toying with marker pens, paper clips and elastic bands. If you are conscious of being a “fiddler”, you should reduce the temptation by keeping jewellery, pendants, necklaces, badges, cuff-links, to a minimum. Equally, you should keep well away from easily manipulated objects, such as loose change in trouser pockets

- Stroking: Akin to fiddling is comfort stroking, which invariably takes the form of stroking ear lobes or neck, though more advanced forms include folding arms across the body and hugging oneself

- Wringing: Hand-wringing is a common occurrence and appears to an audience as a plea for clemency (which it often is)

- Scratching: Of all the hand gestures, it is scratching that produces the most powerful response from a training audience. The cause of this scratching seems to stem from a tingling sensation in the nerve endings brought about by a change in the body’s chemistry. The effect is to set the speaker into frenzied scratching, soon mirrored by the rest of the room.

When to Use Hand Movements

Hand gestures should only be used to provide greater understanding to a training group. They should have a purpose, should be natural and should be deliberate.

Many trainers believe that if they make vague hand movements, these will be less obtrusive and therefore more acceptable. Small jerky movements only serve to heighten your self-consciousness. If you want to move your arms, you should do so intentionally and obviously.

The main purposes for using hand movements are as follows:

- Reinforcement: Hand gestures are at their best when they are used to reinforce what has been said verbally. In fact, it seems to be impossible to ask for directions without receiving a verbal description together with a demonstration of winding roads and undulating hills reinforced by hand movements. This process of supporting what is said verbally by using hand movements adds a further dimension to any training presentation and can be viewed as an alternative form of visual aid

- Emphasis: Emphasising hand gestures differ from reinforcement gestures in that they do not attempt to describe a situation but rather to stress its importance. Pointing a finger, table-thumping and chopping the air are all examples of emphasising hand movements. Providing these movements are not over-used, they can help communicate to the group the important learning points.

Feet, Legs and Body

Your standing with learners and their attitude towards you can be strongly influenced by the way that you physically stand before the group. It is very difficult to convey an impression of controlled confidence when you are standing cross-legged and wobbling from side to side. The most authoritative posture is still regarded as standing upright. Not only does this provide good eye-contact with the learners and a command over the room, but it does not constrict the diaphragm in ways that sitting can. An acceptable compromise is to sit on the edge of a solid table. This can have the effect of making the atmosphere less formal without inhibiting vocal projection.

Where an upright stance is used, care should be taken to make it look relaxed and comfortable. Trainers should not look like wooden soldiers nor stand like reluctant nudists with hands clasped in front of their body. Moving about can, in certain circumstances, stimulate and refocus the group’s attention. Equally, movement can become the source of considerable distraction and annoyance – however, this is up to you to judge.

FIGURE 9.15: WAYS OF INCREASING THE VALUE OF NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION IN A TRAINING SETTING

Voice

- Vary your inflection, pace, intonation and pitch (lower pitch is preferable)

- Vary the length of passes

- Avoid a sarcastic tone because it usually backfires

- Breathe!

- Watch the back of the room to check whether participants can hear

Eye Contact

- Good eye contact is vital. Eye contact shows that you know your material. It also allows you to “read the audience”

- Look at the group (People who are perceived as sincere look at their group at least 64% of the time; those who are perceived as insincere look at their group only 21% of the time)

- Look around the group gracefully. Share with whole room

- Use your eyes to encourage quieter members to talk - look at them expectantly, but relieve them if they do not respond

- To increase eye contact, limit reading. Do not read from a training manual.

Facial Expression

- Be friendly

- Smile when appropriate

- Look confident

- Enjoy oneself and have fun with the group

Stance and Movement

- Show energy, yet control. You should be yourself. If you are awkward with your hands, use a lectern, clipboard, and lots of visuals

- Move into the group for emphasis and variety. Walk purposefully

- Consider where to stand, cover both sides of the room

- When asking questions, use the aisles or move into the group

- End strong. Do not start “packing up” material during the participants’ final exercise

Gestures

- Be natural and comfortable with participants

- Use gestures to emphasise key points and spice up conversation

- Use gestures to demonstrate relationships between key points

Overall Body Language

- Show enthusiasm and energy during the programme

- Use your whole body to manage disruptive behaviours - eyes, gestures, movement, etc.

- Hold up your hand to stop someone who interrupts another participant

- When the group wanders, move to the flip-chart and use your hand to refocus the group back to the goal or issue

- Step between two participants who are arguing to cut off their eye contact

- Move to a position in the room where participants must look across others and include them in their eye contact when they speak to you.

BEST PRACTICE INDICATORS

Some of the best practice issues that you should consider related to the contents of this chapter are:

- Even where you have prepared to a high level, you are likely to be nervous before a training situation. If you are a skilled trainer, you will be able to control and harness this nervous energy and translate it into enthusiasm and activity