6: TRAINING DESIGN: STRATEGIES & METHODS

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the main elements of the instructional sequence

- Explain the alternative instructional strategies that you can use to deliver your training

- Understand the types of learning objectives that are appropriate for each learning strategy

- List the different types of training methods that you can use

- Explain the advantages and disadvantages of different learning methods

- Understand when particular learning methods are appropriate

- Understand the guidelines to follow when using ice-breakers or buzz-groups.

INTRODUCTION

In Chapter Five, we discussed two elements of the training design process: formulating learning objectives and developing training content. In this chapter, we explain the overall instructional strategy that you can select, and the types of training methods that are appropriate.

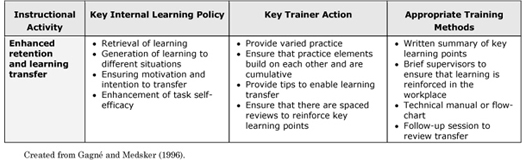

The training or instructional strategy refers to decisions you make on your overall approach. For example, do you need to deliver a theory session, a skill session, or some session concerned with knowledge, results and procedures? We define learning methods as the specific means you intend to use to deliver the training. For example, if you are required to plan a session where you need to present specific information to a large group of trainees, or where the training involves a 1:1 situation, you may use a lecture for the former and mentoring or coaching for the latter.

We provide you with specific advice and guidelines on these two components of the training design process.

THE ELEMENTS OF INSTRUCTION

We discuss a number of instructional strategies later in this chapter. In this section, we explain the main elements of the instructional sequence. These key elements are concerned with:

- Gaining the attention of your learners

- Informing your learners of the objectives

- Structuring the recall of previous learning

- Presenting your training content

- Providing guidance to the learner

- Eliciting performance from the learner

- Providing feedback

- Assessing learner performance

- Ensuring retention of the learning and its transfer.

These instructional events are the same irrespective of the learning outcome. If your training fails, it is likely that you omitted one or more of the steps – for example, in training for skills, a common error is to include no practice or insufficient practice.

Step 1: Gaining the Attention of the Learner

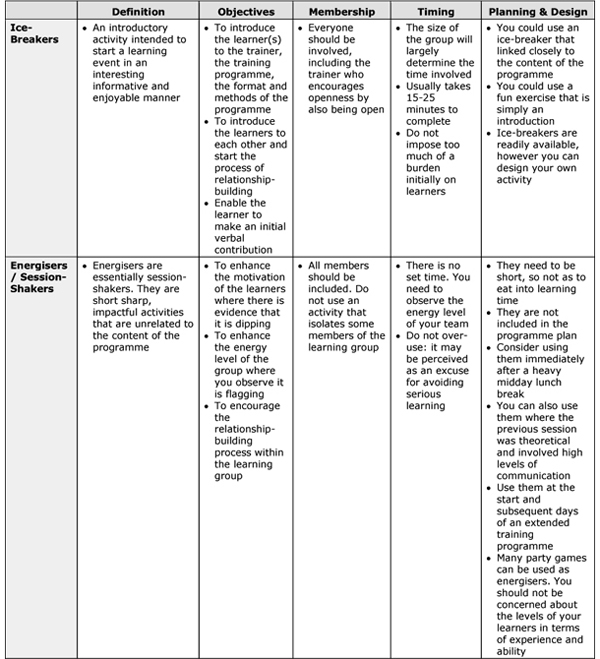

Your first task during training is to gain the attention of your learners. You can do this in a number of ways: by introducing an icebreaker, by gesturing or by the tone of your voice. You could also relate an experience or situation to your learners to gain their attention and emphasise the importance of the content that you intend to cover. You can use some form of ice-breaker, energiser or session-shaker. Figure 6.1 provides some guidelines for their use.

Step 2: Inform your Learners of the Training Objectives

The reason for ensuring that this step is completed is simply this: when your learners understand the learning objectives, they create expectations and these are likely to persist over the duration of your session or programme. It is very important that you seek to connect the learning objective to the motivation of your learners. You can also enhance the motivation of your learners through the recall of a relevant experience.

We know from learning theory that your learners are more likely to understand the objective, if you make the performance component clear. You can state the objective verbally as well as including it in the written materials.

There are different strategies that you can use for different types of objectives:

Learning Objective |

Trainer Strategy to Inform Learners of Objective |

Knowledge Objectives |

|

Verbal Information |

|

Motor Skills |

|

Intellectual Skills |

|

Attitudes |

|

Step 3: Integrating Previously Learned Material

You will facilitate and enhance the learning of new material, if you take steps to integrate material that your learners have learned previously. For example, if you are focusing on knowledge objectives, then it is useful to refer to previously learned concepts or rules. The same rule applies to verbal information. You could, for example, provide an outline or summary or ask your learners to recall an experience that is relevant to the new information. You could also use questioning techniques or some form of handout to achieve this task.

If your learning objectives focus on motor skills, you could use a mental procedure that explains the execution of the task. In the case of intellectual skills, you will need to summarise previously learned rules or principles. The recall of previously learned attitudes is more complicated, so you may need to provide an appropriate example to illustrate your attitude. The example needs to be brief and focused.

Step 4: Presenting Your Content to the Learners

At this point, you will present the new content to your learners. If you are focusing on intellectual skills, for example, then you should explain the dimensions of the skill and use examples to illustrate the key components or dimensions. You will need to show how the skill differs from other related skills. You should organise verbal information in a sequence that is most meaningful to your learners. If you are training in motor skills, then they need to be demonstrated, pointing out the important dimensions.

We provide you with more guidance on presentation and direct instruction in Chapter Nine.

FIGURE 6.1: USING ICE-BREAKERS, ENERGISERS/SESSION-SHAKERS & BUZZ GROUPS

Step 5: Providing Guidance to Your Learners

The purpose of this step is to ensure that your learners encode the content. You want to ensure that the new content is made as meaningful as possible. You can achieve this step in a number of ways:

- Provide your learners with concrete and relevant examples that illustrate more abstract ideas

- Provide further elaboration on each idea that you presented in Step Four

- Provide some examples and get your learners to analyse each example

- If you are teaching rules, then you could provide a set of problems and get your learners to identify which rules apply.

We provide more guidance when we focus in more detail on specific instructional approaches.

Step 6: Getting your Learners to Perform

You have now come to the point where you require your learners to demonstrate what they have learned. This step is often called practice. You have a number of options depending on the particular learning objective that you have in mind:

- If your objective is concerned with verbal information, you could ask them to state the verbal information in the correct sequence

- If the focus is on intellectual skills, you could give your learners a problem and ask them to apply or demonstrate the skill

- If your objectives are more cognitive in nature, the most appropriate strategy is to give your learners an unfamiliar or complex problem and have them derive an appropriate solution

- For motor skills, the best strategy is to get your learners to execute the performance

- If your skill is particularly complex, it may not make sense to get the learners to practice the total skill or complete task.

Step 7: Provide Feedback to Your Learners

When your learners have participated in practice, your next task is to communicate to your learners the extent to which the performance were satisfactory.

It will often be the case that the feedback is built-in and immediate. Corrective or formative feedback is important, because it concerns the manner of performance and it provides advice to the learner about how to improve.

Step 8: Assessing the Learning

Your end result in any training situation is to ensure that a particular standard is achieved. You will help to ensure that the standard is achieved through guidance, corrective action, and shaping, and repeated practice to ensure that the learning is reinforced.

At some point, you will find it appropriate to conduct an assessment or administer a test, whose purpose is to ensure that the learner can perform the task consistently. The learner should complete this task without assistance and to a preset standard of quality. You should select a test that matches your learning objective and is not overly difficult.

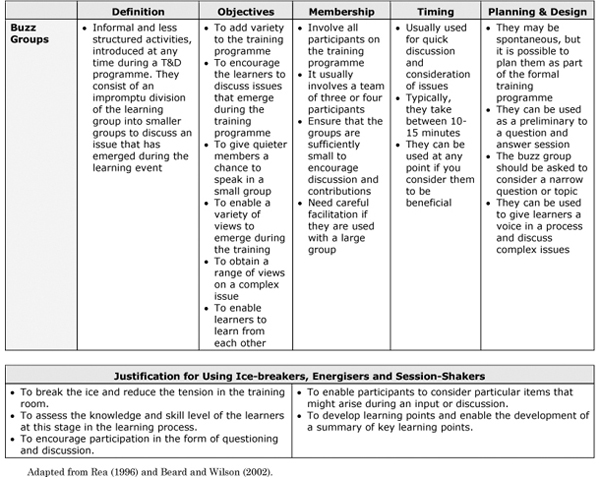

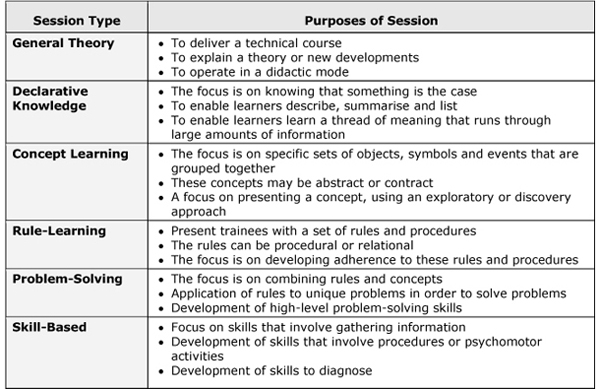

Step 9: Enhancing Retention and Learning Transfer

We define retention as “the ability to reproduce a learned behaviour or component of knowledge after a period of time has elapsed”. Transfer of learning is the ability to use the learned skill in a different context. We consider the issue of transfer in Chapter Twelve.

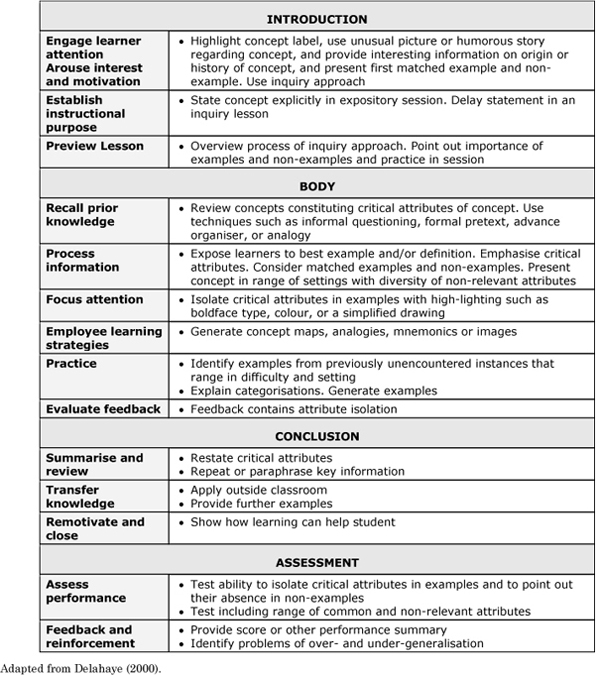

We will now consider six different instructional strategies that focus on different types of learning objectives. Figure 6.2 provides a summary of the strategies.

FIGURE 6.2: INSTRUCTIONAL ACTIVITIES, ASSOCIATED ACTIONS & LEARNING METHODS

MAKING DECISIONS ON YOUR TRAINING OR INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGY

Your instructional strategy refers to the overall approach you intend to use to achieve your learning objectives and deliver your training content. Your training or instructional strategy provides your overall framework. It will have a major influence on the training methods you will use, the types of training materials you will need to support your strategy and the amount and types of visual aids.

You can adopt one or more of seven generic training or instructional strategies. You may use a combination of strategies within one training course, depending on the nature of your learning objectives. Figure 6.3 provides a summary of each of these instructional strategies.

FIGURE 6.3: SUMMARY OF INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES

A General Theory Session

If you wish to deliver a theory session, then your instructional strategy will be a general theory session. You might typically be expected to deliver such a session as a technical training course or as part of a management development programme. Theory sessions should be short, because the didactic nature of the session may reduce learner interest and motivation. An effectively-designed theory session will comprise:

- Introduction

- General body

- Conclusion.

The Introduction

The introduction will perform the following functions:

- Gain interest: This is where you grab the trainees’ attention, by using a joke, a cartoon, a graph on the overhead projector, a controversial statement, a story of common interest, or a startling question, relevant to the training subject

- Check current knowledge: You should know the quantity and the quality of the trainees’ knowledge, so that you can pitch the presentation at the right level. To find out the level of current knowledge, you can ask a few questions or try a written test. You should have made basic inquiries about the trainees before the session. If you had contact with the trainees recently, you will already know what they know. If you have access to training needs analysis data that will also help

- Orient: This is where you set the scene: Explain the session title and relate it to the trainees’ current relevant knowledge and experience. If there has been a previous relevant session, go over the information presented in that session, preferably by using questioning techniques

- Preview the session: You might lose the element of surprise here, although best practice recommends that you should preview the session

- Motivate: Why should the trainees sit and listen to you? They will not, unless you motivate them and create the need to learn. To satisfy that need, they will then listen to you.

In the introduction, you should show the trainees that the subject matter of the session is important. The message is: If they acquire this knowledge, they can make a contribution to themselves and to the organisation. You should show the learners how this particular learning fits into the total picture, since they will want a general idea of where they are going. In addition, telling the trainees what ground they will cover in the session provides a target, establishes appropriate expectations about the content of the session, and allows trainees to check the programme for themselves. The simplest and most direct way of achieving this is for you to tell the trainees the learning objective(s) of the session.

The Body of the Session

In this portion of the session, you transfer the bulk of the information to the trainees. You should plan to break this into logical segments, and a time or priority order may provide the pattern. For example, one fact may have to be learned before the second fact can be understood. The most effective method is to develop each segment around an objective.

Once you define the number and sequence of segments in the body of your session, you can build them into the three logical steps of explanation, activity and summary (EAS):

- The E (Explanation) Step: In this step, you give trainees new facts or allow them to discover new facts. The easiest and most common method is to “tell” the information, although it is often the least efficient method. We know from research that trainees use only about 11% of their learning capacity if a trainer relies entirely on hearing to get the message across. In addition, you will find it difficult to keep their interest long enough. The most satisfactory method is to make use of the trainee’s sense of sight through visual aids, along with telling. A more challenging method, and one that requires more skill, is to use questioning techniques to elicit the information from the trainees

- The A (Activity) Step: Learning by doing describes the A step. Within one session, the E and the A cover the same content, with the E completed from a trainees-receiving-new-information point of view, while the A is completed from the trainees-doing-it point of view. It may be difficult to achieve this component, if your material is very theoretical.

The A step should closely resemble the on-the-job behaviours you require. This resemblance will increase the meaningfulness of the activity and thus reinforce the message in the E step.

The A step provides four important advantages for you as a trainer:

- First, it indicates to the trainee how much of the information he or she has retained and thus highlights weaknesses

- Second, the quality of the activity tells you whether the E step was satisfactory. It makes no sense to go on to the next explanation, if the preceding explanation has not been understood or cannot be applied by the trainees

- Third, the A step separates one explanation from the next explanation and thus stresses structure within continuity

- Finally, if you have made each EAS segment equivalent to one objective, then this will provide you with a good structuring device.

- The S (Summary) Step: In this step, you bring all the key pieces together and tie up loose ends. It provides you with an opportunity to ask for questions from the trainees before going into the next EAS segment.

Conclusion

This is a difficult component to complete. Your conclusion should incorporate five basic items:

- Review or Recap: Briefly, go over the main themes in the session. Emphasise important or key points

- Test to ensure that learning has taken place. Make the test either oral or written, or require some performance activity that will demonstrate the level of learning achieved

- Link to subsequent sessions on the programme

- Clarify and allow time for questions to clear up any problems or misunderstandings

- Finish, leaving the trainees in no doubt that it is complete – for example, ask the question, “Before I finish, do you have any final questions?”.

We now set out in Figure 6.4 some guidelines that you can follow when completing a general theory session.

FIGURE 6.4: GUIDELINES FOR CONDUCTING A THEORY SESSION

A Declarative Knowledge Session

Many training activities, especially in the technical or scientific area, involve declarative knowledge, which involves “knowing that” something is the case. When you set an objective such as “”to understand a particular component of content”, you are talking about declarative knowledge. Words that are used to describe declarative knowledge include: “explain”, “describe”, “summarise” and “list”.

A declarative knowledge session may consist of three categories:

- Labels and names, which involves the pairing of information; making a connection between two elements

- Facts and lists, which may describe a relationship or which may be learned as individual facts, seemingly apart from other information

- Learning a thread of meaning that runs through an extensive body of information.

Declarative knowledge sessions can prove difficult to design. You need to be an experienced trainer to design and use this type of instructional strategy. This type of session will usually be conducted with trainees who have moderate to high cognitive ability levels. Figure 6.5 sets out the components of a declarative knowledge session.

A Concept Learning Session

Many management development and technical training programmes require participants to understand concepts. Concept learning focuses on sets of specific objects, symbols or events that are grouped together on the basis of shared characteristics and which can be referred by a particular name or symbol. Concrete concepts are known by their physical characteristics, whereas abstract concepts are not perceivable by their appearance. Many management concepts such as the “learning organisation” and “total quality management” are concepts of an abstract nature.

You have two general approaches available to instruct on concepts:

- An inquiry, exploratory or discovery strategy, where you present the learner with examples and non-examples of the concept, and use these to prompt the learner to discover the concept underlying the examples

- An expository strategy, where you present the concept, its label and its critical aspects early in a session. An expository strategy does not present many examples and non-examples; however, it follows a discussion of a best example and how it embodies the characteristics of the concept. You then encourage learners to develop their own examples, but not until you have examined critical attributes of the concept.

FIGURE 6.5: STRUCTURE FOR A DECLARATIVE KNOWLEDGE SESSION

You can use the instructional strategy set out in Figure 6.6 for concept sessions.

FIGURE 6.6: STRUCTURE FOR A CONCEPT LEARNING SESSION

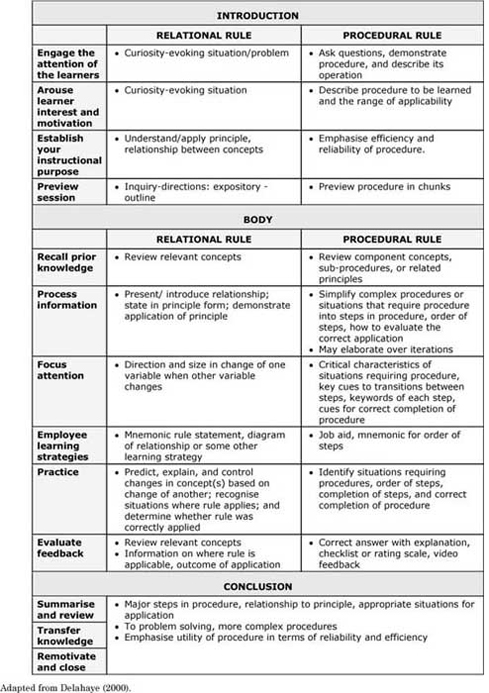

A Rule Learning Session

Many training events focus on rules, which constitute a major part of operator training, manual handling, health and safety, employment law, codes of behaviour as part of an induction course. You will most likely have to conduct this type of session on numerous occasions.

In a training context, rules may be of two types:

- Relational rules set out the relationship among two or more concepts

- Procedural rules are a generalised series of steps initiated in response to a particular circumstances to reach a specified goal.

You can use an inquiry approach to train learners on rules.

You might follow this sequence:

- Present learners with a puzzling situation that shows the relationship among the variables in question. You may demonstrate or describe the situation

- You can ask the learners questions about the situation that they answer in the form of “Yes” or “No”. Questions should eventually move on from questions verifying the nature of the situation to questions gathering data about the situation

- At the conclusion of the session, learners should be able to state a formal principle or rule about the relationships of the concepts involved

- Learners should be encouraged to discuss the inquiry process itself, including those approaches that were more beneficial.

Typically, you would use this approach when training managers on the application of, say, employment laws. You should be aware that this strategy is time-consuming and requires considerable expertise. Before you start training on a procedure, the steps of the procedure must be clear. You should verbally describe the procedure following these guidelines:

- The procedure steps should be described in clear, unambiguous sentences

- Each operation step should represent a single elementary action

- When possible, each step should be dichotomous, resulting in the selection of one of two possible paths

- Decision steps should be stated in the form of a question

- Operation steps should be stated as imperative sentences.

Use the approach in Figure 6.7 for a rule-based session.

FIGURE 6.7: STRUCTURE FOR A RULE-BASED SESSION

A Problem-Solving Session

Problem-solving sessions are commonplace in training programmes and are defined as focusing on skills to combine previously-learned rules. This type of session yields new learning, because the learner is able to react to problems of a similar class in the future.

One of the most effective strategies for training in problem-solving involves the presentation of carefully-sequenced problem sets. The first set of problems should be the most fundamental of those to be learned. Trainees may learn these rules well in advance of the problem-solving instruction or just prior to it. After learners have received instruction on selecting and combining the rules to solve a class of problems, then you may provide additional rules and combine these rules with the earlier ones to solve a larger class of problem(s).

A simulation can be used in a problem-solving session. A simulation is an activity that attempts to mimic the most essential features of the reality by allowing learners to make decisions within the reality without actually suffering the consequences of their decisions. Case studies and case problems may present a realistic situation and require the learner to respond as if they were the person who is solving the problem in reality.

We suggest that you use the sequence set out in Figure 6.8 when conducting a problem-solving session.

FIGURE 6.8: STRUCTURE FOR A PROBLEM-SOLVING SESSION

A Skill-Based Session

There are three generic types of skills that you may be required train on. First, the most basic type of skill involves gathering information (usually by sight) and acting on it (usually with some type of muscle movement). This is called a psychomotor skill.

The second type of skill involves procedures, or psychomotor activities linked in a series. The order of the psychomotor activities is crucial. Aspects of driving a car (starting up, turning a corner) are examples of procedural skills. The main learning aid here is a job breakdown or checklist that specifies the order in which component psychomotor skills must be performed.

The third and more complex type of skill involves diagnosis. All forms of troubleshooting and problem definition involve diagnostic skills. Discovering the reason why a car will not start is an example. The main learning aid is a logic chart, or algorithm.

If you know the types of skills included in a session, it will help you in two important ways:

- You become more aware of the aspects of the skill that should be emphasised (for example, order in procedures, logic in diagnosis)

- You are reminded of the appropriate learning aids that should be prepared while planning the session.

When applying a theory-session model, you must sometimes contrive an activity that enables you to decide whether or not the trainee has attained the training objective.

The situation is a little easier when working with a skill-session model, because the trainer can actually see the trainee performing the task and applying the content of the session directly. In the skill-session model, the physical activity (the behavioural component of the objective) is what the session is all about.

When planning a skill session, you should break down the task into a series of closely-linked steps of physical activity. If the trainee practices this series over and over, he/she will become more proficient at the task (as measured in time and quality). Consequently, the basis of any skill session is a task analysis – a breakdown of a task into skill steps.

Task Breakdown

The task breakdown is usually written directly from information gathered during a training needs analysis. It is basically a step-by-step definition of the task, arranged so that each skill step is a building block on which to place the subsequent skill steps. Adequate performance of all steps ensures adequate learning of the task.

In addition, the breakdown should support each step with explanatory points, which answer the “how”, “why”, “when” and “where” and describe also the vital tasks involved in the task. Explanatory points should also emphasise safety aspects.

Research shows that a trainee should be able to perform the specified task in less than 10% of the total length of the sessions. Thus, if the trainer has a 40-minute session, he/she will probably have time to present, and the trainees have time to learn, a 4-minute task.

The Training Objective(s)

When you complete the task breakdown, you will find that you have already done the basic work toward preparing the training objective(s). You should make the training objective(s) of the session clear.

We now explain the structure of a skill session for a simple task. Like the theory-session model, a skill-session model has three component parts:

The Introduction

There are four tasks that you should consider in the introduction:

- Orient: Announce the topic of the skill session, and then show trainees how this particular task fits in the total process. You should not make the explanation too detailed. If the skill session is a follow-up to a theory session, you should summarise the knowledge gained in the theory session, preferably by using questioning techniques

- Motivate: Why is this session so important? Why should the trainees perform the task in the manner you have specified? The answers to these questions must be logical, and not just “because the instruction manual says so”. You should show the trainees that the acquisition of the skill to do this task is important to them

- Measure current knowledge: This is the most important component of the introduction. How does the trainer know that trainees can use a screwdriver correctly? Do they have basic keyboard or typing skills? At times, the trainer may have to find out whether there are any left-handed trainees on the programme. This usually occurs when certain physical/directional manipulation is necessary

- State complete training objective(s): State the objective(s) clearly and precisely. You should include a time standard within which the trainees must complete the task. This gives the trainees something concrete to aim at and makes it easier for the trainer to judge whether or not the instruction has been successful. Furthermore, the trainees thus have an easily remembered standard that they can take back to the job. If the end-of-training standard differs from the standard required after subsequent practice on the job, point this out to trainees and specify both standards.

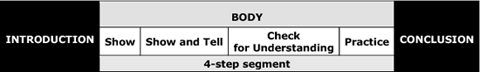

The Body

Where trainees are learning a simple task, the body of a skill session consists of four complete and separate steps:

- Show: You should perform the task as set out in the task breakdown within the time limit set in the statement of objectives. This gives the trainees an easy introduction to the task and also gives them a mental picture and a standard to work toward. This demonstration is silent, but you can draw attention to particularly important points on safety. The length of this component depends on the task. When you have finished this step, you should quickly tidy up the work area in preparation to start the task again

- Show and Tell: You should SHOW and TELL each skill step as set out in the task breakdown. Emphasise safety factors and particularly difficult or tricky parts. You should stress each skill step, and pause between each so that the trainees know that every skill step has a separate identity

You need to make sure that every trainee can see the “show and tell” clearly. You may encounter the problem of left-handed versus right-handed trainees. If this happens, stand the right-handed trainees behind you and place the left-handed trainees in front. Make provision for the trainees to ask questions, and constantly check that they all understand each step or explanatory point as you progress

You must be aware that you are also a model. Throughout the session, you must follow all the correct methods and maintain good housekeeping and safety standards

- Check for understanding: This is the initial feedback (both for you and for the trainees). A useful technique here is to ask the trainees to name each skill step. You could actually perform the task to the trainees’ instructions. Do not let one trainee name all the steps – give all trainees an opportunity. The trainer must be certain at the end of this stage that all the trainees know the steps and key points, and make sure the trainees stress the importance of all the safety features mentioned during the session. When you are sure that the trainees know all the skill steps, they are ready for the final stage

- Practice: Trainees should practice for at least 50% of the total time allocated for the body of the session. Thus if the skill session body is 20 minutes, then the practice step alone must last at least 10 minutes. Before the trainees begin the practice step, you should have provided them with three basic items:

- A task breakdown sheet. This should show each step and the explanatory points for each step. Include drawings, if they will make the points clearer

- The correct tools and equipment to complete the skill. Check that these operate within the safety requirements

- Sufficient material. The trainees will most probably need three or four attempts before they become proficient within the standard stated in the objective. Therefore, provide sufficient material for the task to be carried out a number of times

You should supervise the trainees continually throughout the practice period and be vigilant for unsafe practices, untidy housekeeping, and incorrect methods. Errors should be corrected in a constructive manner, and you should watch for a trainee who is confused or lost, and spend more time with them.

The practice step is your opportunity to give individual instruction, so make the most of it. The previous three steps (show, show and tell, and check for understanding) are group-oriented, so you have to aim at the average trainee. You can use the practice step to help learners who are experiencing difficulty with the skill and to give learners who have mastered the skill additional challenging tasks to maintain their interest.

The Conclusion

You should briefly review the steps and key points (using questions). You can write these on a white-board for emphasis and to encourage trainee participation throughout the conclusion. In particular, check:

- Whether they found any of the skill steps particularly difficult. This will reinforce these steps for the trainees and let the trainer know which steps to emphasise next time

- Whether they have discovered any new or different techniques. This is a fertile field for ideas for the next time and also gives the trainees a sense of having contributed. If they create a realistic alternative technique, they will leave the session with that particular skill greatly reinforced. In addition, this quick check can identify trainees who identify possible shortcut techniques during training and decide to do it “their way” back on the job. Frequently, the trainer can point out to the trainee why the shortcut is not acceptable and prevent negative outcomes such as increased costs for the organisation, to (in extreme situations) permanent injury or death for the employee.

You should review briefly the standards of time and workmanship, and emphasise the most important safety factor; check if there are any questions and provide a definite finish to the session. Some of the guidelines you should follow when delivering a skill-based session are shown in Figure 6.9.

FIGURE 6.9: CHECKLIST FOR CONDUCTING INSTRUCTION

SELECTING APPROPRIATE TRAINING METHODS

We have so far focused on your overall instructional strategy. We now consider the next design decision that you have to make: What methods of learning should be used to achieve the learning objectives and fit into the instructional strategy? You have a large choice of methods to select from.

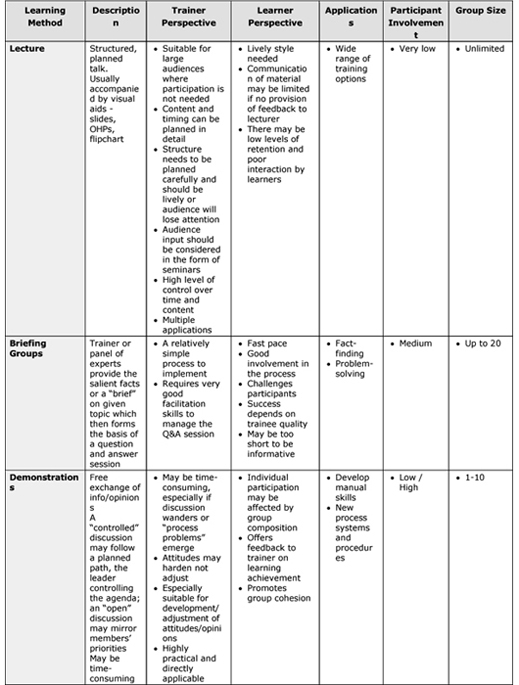

Group-Oriented Didactic Learning Methods

Most formal training events take place in a group setting. Therefore, during the course of your career, you are likely to use a number of group-oriented training methods. These methods are didactic in nature and place a strong emphasis on your expertise knowledge of the subject matter and your delivery skills. They include:

- Lectures: We define a lecture as a talk or verbal presentation given to a small or large audience. Your objective is to convey aspects of your knowledge to the learners, which they are then expected to absorb and retain. The absence of any involvement, other than listening by learners, means that the process is essentially a passive one, and you have little or no opportunity for the group to interact. In order to be effective using this method, you need to be an expert on the subject and communicate this with authority to the audience. You should ensure that the lecture does not become a monologue, but rather something that your learners can identify with and participate in.

- Briefing Groups: Briefing groups are often used in training and non-training situations because they are an effective means of two-way communication. Briefing groups provide a mechanism for cascading information. This allows for discussion within groups; managers can get immediate reaction and feedback. The characteristic of a briefing group is this continuity of communication and feedback

- Formal Talks: Formal talks, presentations and lessons are very popular training methods. The concentration level of the learner will most likely vary depending on the individual, the content and the skill of the trainer. This method is quite effective provided it is supported by handouts to highlight the significant learning points. It is preferable that you also provide practise for learners so you reinforce the learning event.

- Demonstrations: You can use a demonstration, followed by a practice session, when you are conducting manual and social skills training. In a demonstration, you show the complete exercise (the overview) and then the individual components. The trainees then copy your individual movements one at a time and you correct mistakes. You and the participants can then discuss each learner’s performance and provide feedback and guidance. You must ensure that all the learners can see the demonstration. This is very often overlooked

- Seminars and Workshops: You should use a seminar or workshop with small groups of learners (ideally no more than 15). The method of instruction you use should be Socratic rather than formal instruction, with the whole group working out answers to a series of questions. Your role will differ between a seminar and a workshop. In a seminar, your role is to achieve a predetermined result. Therefore, you will take more control. In a workshop situation, the focus is on tackling real questions, where there are no predetermined answers and so you will use a more facilitative style in the workshop content. Both methods will be effective (if skilfully set up and facilitated). The learners are required to work out the answers for themselves; therefore, they perceive ownership of the situation. Learners are then more likely to remember what they have learned and you are more likely to achieve transfer.

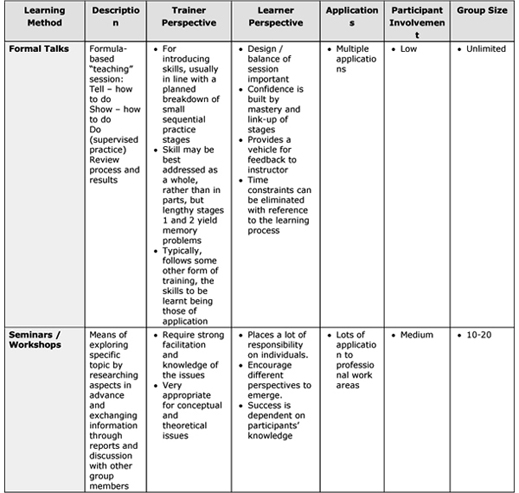

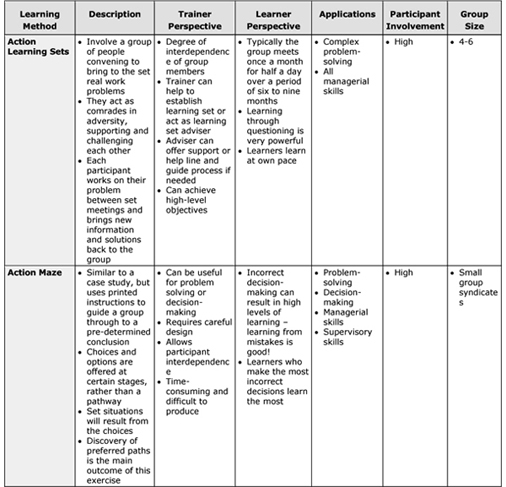

Figure 6.10 presents the advantages and disadvantages of these more didactic methods from your own perspective and that of your learners.

FIGURE 6.10: ADVANTAGES & DISADVANTAGES OF GROUP-ORIENTED, DIDACTIC LEARNING METHODS

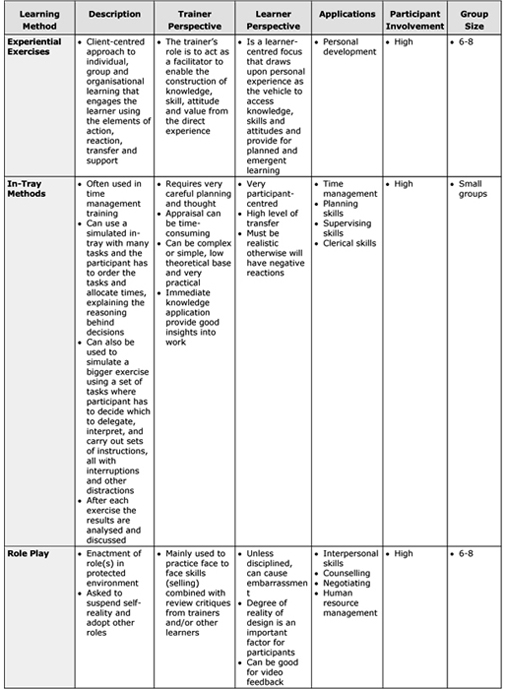

Group-Oriented Experiential Learning Methods

Your learning objectives may require that you use more experiential learning methods. These methods factor in the experience of the adult learner and they allow for significant amounts of participation by the learner in the learning event. Experiential learning methods make significant demands of your facilitation skills. There is a strong focus on process and significantly less on your subject matter knowledge. As you develop your confidence as a trainer, you will need to become more competent using methods such as role-plays, case studies, in-tray exercises and brainstorming.

Role-plays

Role-plays are very useful in a training situation. They usually involve presenting the trainee with a scripted scenario or situation and asking them to act out a particular role with the intention of reaching a conclusion. If you are to gain the maximum benefit from a role-play in a learning situation, it is important that the incidents you include as part of the role-play are realistic. You will need to give yourself time to prepare an outline brief of the personalities involved and ensure that the circumstances closely reflect those encountered in the working environment. The brief you prepare should be sufficiently detailed to make it clear to your learners the learning issues involved. It should also be sufficiently flexible so that the learner can improvise and give it a personal interpretation.

Role-plays need careful facilitation. The objective of the role-play is on behaviour, not on the acting talents of the learner. You will need to brief your learners on what they should look out for and focus them on the relevant content and process issues. You can ask your trainees to assume the role of observers and to record their observations of the behaviour demonstrated. You should provide your learners with a structured observation sheet to enable them to record systematically their observations.

Case Studies

These are very frequently used in management training and development programmes and are a very popular and effective method. Case studies are built around the notion that the trainee is presented with a record of a set of circumstances, which may be based on an actual event or an imaginary situation.

There are three variations of the case study method that you might find appropriate:

- A case study, where you provide trainees with a set of facts, real or imagined, and their task is to diagnose a particular problem(s)

- Case studies where the learner’s task is to identify problems but also to go into problem-solving mode and generate appropriate solutions

- Case studies that provide the learner with both the problem and the solution but ask the learners to be evaluative, comment on the actions taken and assess the implications.

The variation that you will use will depend on your learning objectives and the capabilities of your learners.

The complexity of the issues will dictate whether you incorporate the case study into the training programme as a short 30 to 60 minute exercise or opt for a more complex learning event. With managerial grades, your course might be built around the case study itself and last for several days.

Irrespective of the case study variation that you use, the learning will be achieved by providing information on an issue or series of issues. This information might be in documentary form, (such as a report) or it could be communicated through oral or visual means (such as a video or slide presentation). Once your learners have been provided with the raw data to examine, you can begin the process of analysis.

“In-tray” Exercises

This method is most relevant in the context of management or graduate training. “In-tray” exercises consist of a paper-handling simulation based on the contents of a typical company employee’s in-tray. The learning objective is for the trainee involved to be projected into the position of the person responsible for dealing with the in-tray items and then to resolve all the work it contains. On completion of the exercise, you will review the learner’s progress and provide feedback.

You can use “In-tray” exercises in two situations:

- As a diagnostic tool to discover how the group member would handle the work outstanding in the tray

- As an evaluative method to test how well the trainee would put into effect the skills learnt on the training course.

In the first situation, each learner is given a series of items to sort through and take action on as they feel appropriate. The exercise would also be carried out independently. The final step is to reconvene as a group to review the decisions or actions taken and to assess their effectiveness.

The approach is similar where the in-tray is used as an evaluative method. The items in the in-tray – files, letters, and memoranda – are reviewed individually and action taken by the person involved. The main difference lies in the fact that, prior to undertaking the task, the trainee will be given advice on the best means of dealing with the particular problems that the tray highlights. You will judge the trainee on their ability to handle the complexity in the exercise. It is important to emphasise that providing the feedback at this stage of the exercise is an essential ingredient in the learning process.

You will need to give a significant amount of time if you propose to use an in-tray exercise.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is essentially a loosely structured form of discussion. Its main function is to provide you with a practical means of generating ideas without participants becoming embroiled in unproductive analysis. Its success rests on two important principles:

- The first is founded in synergistic theory, that a group can provide more high quality ideas by working together than the same people would produce working independently. This is because the group interaction produces cross-fertilisation, in which an idea presented on its own, which normally would be dismissed as impractical, is adapted, adopted and improved by someone else to provide a more feasible approach

- The second principle is that, if a group is to produce ideas, it is imperative to avoid subjecting these ideas to evaluation too early on such that the evaluation inhibits creative thinking. Creative thought passes through three stages: the generation of the idea; the evaluation or analysis of that idea; and the application of the idea to the chosen situation. If others sit in judgement after each idea is proposed, then analysis by paralysis sets in and the flow of ideas dries up. Creative thoughts can be stimulated in an environment where judgement is postponed after all the possible solutions have been provided.

There are six ground rules for running a brainstorming session.

- No criticism: The free flow of ideas can only take place where there is no fear of being criticised. Criticism in this context is given a wide interpretation, so that this will clearly preclude an outright attack on a proposal, but it also extends to cover indirect ridiculing of someone’s idea or being very patronising about it. It is also important not to imply that an idea has no merit by ignoring any contribution or by betraying cynicism through such non-verbal gestures as a dismissive shrug or raised eyebrows

- Encourage ideas: In order to ensure that there are enough ideas for cross-fertilisation to take place, the group must feel that their contributions are valued. The emphasis should be on the quantity of suggestions and not the quality. There will be sufficient opportunity at the evaluation stage for individuals to voice their feelings about any particular suggestion

- Equal participation: It follows that, if everyone should feel that their suggestion is worthy of consideration, then everyone should be entitled to put forward their ideas. The fairest way to prevent one or two more dominant group members from monopolising the group is to establish a system where each person is asked for a contribution in turn. This might make the process more regimented but this is more than compensated for by the involvement of the whole group

If a member of the group is unable to make a suggestion at any point, this should be indicated by the individual concerned and should be accepted without comment and the process continued. (It is quite likely that while no idea springs to mind this time round, subsequent recommendations might trigger a thought for the next time)

- Free association: In order to gain the maximum number of suggestions, there should be no boundaries on what is suggested. Any idea (no matter how outrageous or farfetched it might seem) is worthy of inclusion. The logic behind this is that an idea, which seems completely impractical, could provide the basis of a worthwhile idea in somebody else’s mind

- Record all ideas: It isn’t just the suggestions that are important but also the opportunity to reflect on them in the hope of inspiring further ideas. In order to allow this to happen, all the ideas should be recorded on a flip-chart or white-board, and in the words used by the participants. Otherwise, further clarification could interrupt the flow of thought and be viewed by some group members as seeking justification before acceptance

- Allow time to incubate: Once the ideas have been set down, there should be some time to contemplate suggestions.

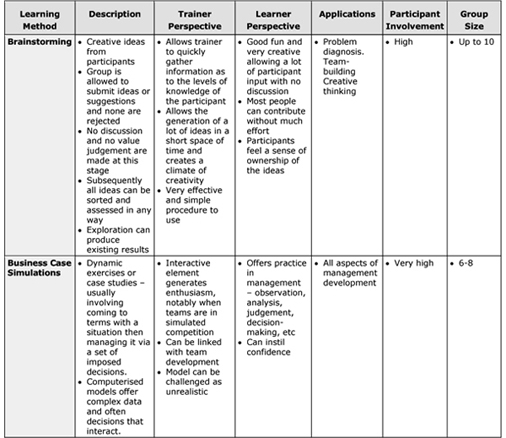

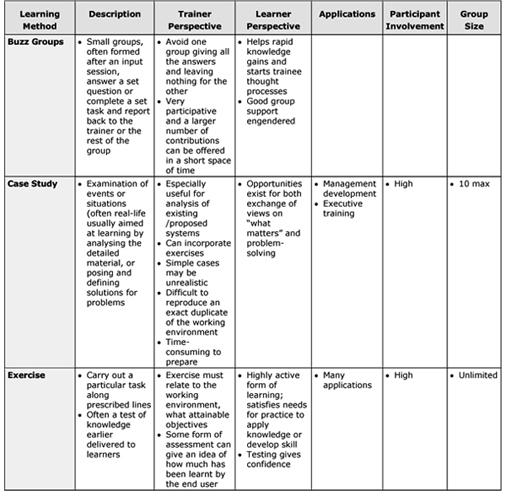

Figure 6.11 presents a summary of the advantages of each method from your own perspective, as a trainer, and from that of a trainee/ learner.

FIGURE 6.11: ADVANTAGES & DISADVANTAGES OF GROUP-ORIENTED EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING METHODS

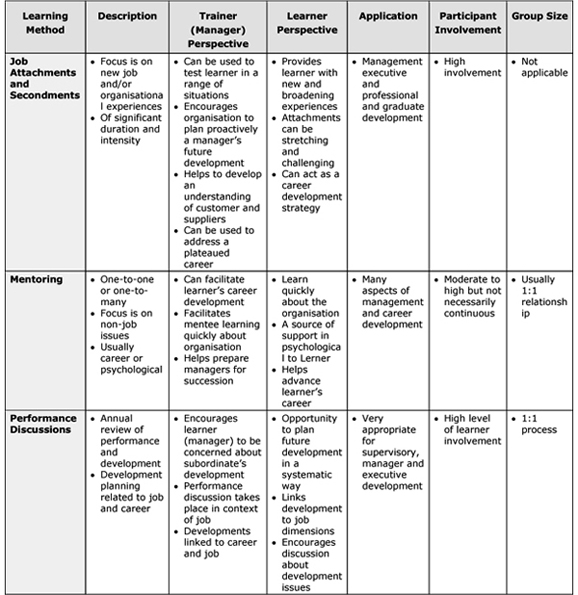

One-to-One Learning Methods

You are most likely to use 1:1 learning methods in an on-the-job training context. They are frequently used for management training and development or where you are training operators on production skills. The more frequently used 1:1 methods include coaching, mentoring, counselling and performance discussions. We discuss the practical application these methods in Chapter Ten.

Coaching

Coaching is most frequently used to develop managerial skills and prepare leaders for more senior positions. You may be asked to perform the role of a coach, although this role will usually be performed by managers. If you are a direct trainer, you may have to coach operators in a production skills training content or in areas such as handling customers.

Coaching can be either an informal or formal process. Coaching as an informal process is an everyday occurrence in organisations. When managers are asked if they coach their staff, very often the reply will be that they do not because they do not associate their assistance in helping the employees with the term coaching but simply as “part of the job”. Formal coaching is used as a learning experience for employees and is considered one of a manager’s most important responsibilities. Managers often find it difficult to adopt a formal coaching role due to: lack of time, inappropriate managerial style or lack of coaching skill on their own part.

Mentoring

Mentoring is a similar process to coaching, in so far as the employee can seek guidance and advice in terms of expertise, experience and understanding. A mentor is usually from another line function and will not be the direct manager of the learner and is usually a few more levels senior. This eliminates any possibility of conflict in terms of the development of, or problems encountered by, the individual or protégé.

It is preferable that the mentor is given clearly defined terms of reference – for example, who makes the ultimate decision if the mentor considers that the employee needs to attend a formal training session to support the informal on-the-job learning? Does the direct line manager allow the learner to attend, even though the suggestion did not originate with the direct manager? Can the manager insist on the employee’s attendance? Constraints, if they exist, should be communicated to the mentors when they take on the mentoring role.

Mentoring can be used with new graduates who are participating on fast-track training programmes. It is also of high value in the development of supervisors and managers.

Counselling

Counselling is often not considered a training method, although it has many components to it that facilitate learning, including discovery, acceptance of responsibility and willingness to change.

Counselling can take many forms in training situations – for example, a manager may “counsel” an employee if a performance level is not being reached or as a result of a misdemeanour of some kind. Another example is if an employee is experiencing emotional or financial difficulties, or if there were “outward” signs of stress.

Counselling skills are important skills for managers and form part of their development process. The essential skill in counselling is that of actively listening and not relating one’s own experience, and thereby assisting the individual to sort out the problem. Counselling does not mean offering advice or anecdotes, which concentrate on one particular response to such problems but instead offering employees alternative solutions so that they can make choices and arrive at their own decisions. Counselling should enable the employee to make decisions and, in some cases, assist in the release of potential energy for change and development for the organisation’s benefit.

Whereas coaching and mentoring are job-related, counselling may cover a wider range of issues and difficulties, including problems outside the working environment that could affect the standards of the employee’s performance. It is important for managers to recognise their capability with regard to counselling, and to know when it is necessary to encourage and advise the individual to seek professional counselling outside the organisation. Unless a manager is professionally trained as a counsellor, giving advice and guidance can sometimes lead to further problems.

Counselling may be a once-only session, or it may be conducted over a lengthy period, depending on the particular problem.

Counselling should create a freedom to express a problem in an atmosphere of confidentiality. There are inherent challenges however, because a manager may have to decide at some point to break the confidentiality because the knowledge he/she has learned about the individual could impact on the organisation in some way – for example, an employee might confess to a misdemeanour that could have an adverse affect on the organisation and its profitability.

Performance Discussions

Performance discussions can be learning-oriented. The developmental component of performance discussions depends on the manner in which they are carried out. They have a number of development dimensions. They are an important mechanism to encourage and develop managers to achieve performance standards. Performance discussions should be ongoing. Many performance discussions occur in an informal way as part of the work that an employee undertakes.

Performance discussions are more effective when the performance is assessed against previously set and agreed criteria. An open dialogue has to be created to allow the exchange of ideas without fear of recrimination or the threat of job loss or demotion, and positive outcomes will only be achieved if both the manager and the employee can be honest with each other.

Job Attachments and Secondments

Job attachments to a variety of departments are considered an excellent method of developing managers’ and graduates’ skills. They also help them to discover the areas in which they want to make their main career. Traditionally, technician and graduate engineering apprentices have to work in a variety of departments for a period of six months or so in each. The attachments frequently include sales and finance, as well as the specialist areas of plant maintenance, production, research, and design and product development. This breadth of experience is necessary, if graduate engineers are to gain membership of one of more chartered institutions.

The Japanese practice of rotating young professionals through many departments is widely extolled as producing well-rounded general managers. The Japanese tend to spend several years doing a real job in each department, so they usually are in their 30s before gaining their first management appointment.

Secondment is another form of attachment but differs insofar as it involves moving from one location to another, usually to another organisation or at least to a different site. Secondments are frequently used to develop professionals who may need experience in another organisation or professional context to enhance their skills. Secondments are valuable because they allow for cross-fertilisation of ideas.

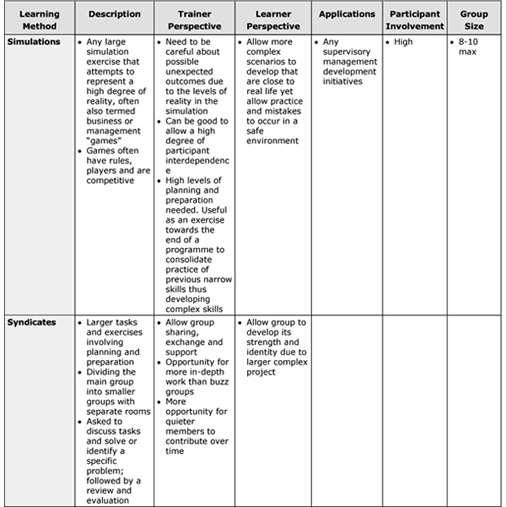

Team-Based Learning Methods

Action Learning

Action learning is increasingly used in supervisory or management development. It seeks to avoid the pitfalls associated with more formal methods, because it uses the actual job of managing and supervision as a vehicle for learning. Action learning is associated with Revans, who holds that learning should begin with the everyday management of problem-solving.

Action learning focuses on both the individual and the team. Through an action learning process, learners actively challenge one another’s ideas, they encourage each other to espouse theories and perceptions that they may not have voiced to date and the process helps learners to consciously think about other ideas and concepts that may be applied.

You should consider using action learning when:

- You want to develop managers to solve complex problems and to challenge organisational assumptions

- You are sure that you have the commitment of your organisation’s leaders to time resources and people to the process

- The problem or opportunity is a genuine one and not some form of puzzle

- You wish to achieve team and organisation learning objectives.

Action learning can achieve a number of purposes, including:

- To voluntarily work on problems of managing and organising

- To work on problems that involve the set members

- To analyse individual perceptions of the problem in order to provide other perspectives and identify courses of action

- To take action that is reported back to the learning set to allow further reflection

- To support and challenge members to encourage effective learning and action

- To raise awareness of group processes and encourage improved teamwork. The learning set sometimes has a facilitator who helps members develop the skills of action learning

- To encourage three levels of learning:

- About the problem

- About oneself

- About the learning process and “learning to learn”.

If you consider using action learning as a method of learning, there are six elements that you should consider.

Element 1: Forming Action Learning Groups

One or more action learning groups (also known as action learning sets) are formed. Each group is composed of four to eight members from different functions or departments. By diversifying its membership in this way, the group can take advantage of different perspectives in addressing organisational problems. Each group includes learners who care about the problem to be addressed, who know something about the problem, and who have the power to implement the solution recommended by the group or to monitor the work of others in implementing that solution.

Element 2: Undertaking Projects, Problems or Tasks

One of the fundamental beliefs underlying action learning is that learners learn best when they take meaningful action to solve important organisational problems and then reflect on and learn from the actions taken. Several criteria are used to determine whether a problem is appropriate for an action-learning group to address:

- Reality: The problem must be current, be of genuine significance to the organisation, and require a tangible result by a specific date so that the investment of time and funds is justified

- Feasibility: The problem must be within the competence of the group to solve

- Richness in potential learning: The problem must provide learning opportunities for the group members and its solution must offer possible applications to other parts of the organisation.

Element 3: Questioning and Reflecting

Action learning focuses on the right questions rather than the right answers. The assumption is that what people do not know is as important as what they do know. In action learning, the group members tackle a problem by first asking questions that clarify the exact nature of that problem; next they reflect on the problem and identify possible solutions; then they choose that action to take.

The classic formula for action learning is L = P + Q + R, where L is learning, P is programmed instruction (knowledge in current use, in books, already in one’s mind, and so on), Q is fresh questioning and R is reflection (pulling apart, making sense of, trying to understand).

When the members of an action-learning group begin to address a problem, they ask and answer the following questions:

- What goal is the organisation seeking to accomplish?

- What obstacles are keeping the organisation from accomplishing this goal?

- What can the organisation do about the obstacles?

- Who knows what information is needed?

- Who cares about having a solution implemented?

- Who has the power to implement the solution?

Element 4: Making a Commitment to Action

There is really no learning unless action is taken on the problem that a group addresses, and no action should be taken without learning from it. The group members either must have the power to implement their solution(s) or must be assured that others will assume responsibility for implementation. Action enhances the learning, as it provides a basis and anchor for the critical dimension of reflection.

Implementation is part of the contract between an action learning group and the organisation. If the group members merely prepare reports and make recommendations, their commitment, effectiveness, and learning are diminished. Unless a solution is implemented and the group members reflect on that implementation and its effectiveness, there will be no evidence that something better or different can be done. Consequently, there will be no indication that real learning has taken place.

Element 5: Discussing what has been learned

Solving an organisational problem provides immediate, short-term benefits to the organisation. The greater, long-term benefit, however, is the learning that the group members acquire about themselves, about the effectiveness of their group, and about ways in which that learning can be applied throughout the organisation. Therefore, time must be set aside for group members to discuss what they have learned as individuals and as a group and how that learning can be used in other parts of the organisation.

Element 6: Analysing the Learning Experience

It is advisable for each action learning group to have a facilitator (also known as a set advisor). This person may be either a member of the working group or a non-member, whose sole task is to help the group members reflect on what they are learning and how they are solving problems. The facilitator assists the group members in analysing how they have listened, reframed the problem, provided feedback to one another, handled differences, fostered creativity, and so on. He or she should be competent in working with the processes vital to action learning: questioning, emphasising, learning, avoiding judgement, focusing on the task, and providing air time (time to talk) for every member. If no facilitator is involved, the group must still analyse their learning experience for themselves.

There are a number of practical issues that you may need to consider when implementing action learning as a method. These steps that follow are advisable if you are to maximise the potential of the method:

- Step 1 – Hold an information workshop: An organisation-wide workshop shows both managers and non-managerial employees how action learning works. External consultants or knowledgeable staff members explain and demonstrate the basic principles and dynamics of action learning

- Step 2 – Establish Projects: One or more projects involving organisational problems are identified to be addressed by action learning groups. The projects chosen are ones that will be 1) meaningful to potential group members and their jobs and 2) important to the organisation as a whole. The problems must be ones for which employees can offer several viable solutions, not ones that could be better solved by experts

- Step 3 – Form Action Learning Groups: Action learning groups are formed, each consisting of four to eight members from diverse backgrounds and representing different kinds of functional expertise. A facilitator also may be assigned to each group, although this is not absolutely necessary. If a facilitator is assigned, that person should be someone whom the members do not already know, so that he or she can act independently of the group’s culture

- Step 4 – Work on Problems: Each action-learning group meets on a periodic basis (daily, weekly, or every two weeks) over a period of several weeks to several months. Each meeting requires a full day or a few hours, depending on the nature of the problem being addressed and the constraints of the members’ schedules and responsibilities

- Step 5 – Record Findings: An action group’s learning is developed as a result of discussing and resolving its problems. In each group, the members use such techniques as feedback, brainstorming, reflection, discussion, and analysis to reach a solution. What they discover and experience during this process is recorded

- Step 6 – Reflecting on the Work: After a group completes its project, its members reflect on their work, either with or without the assistance of a facilitator. Their objective is to learn as much as possible about how they identified, assessed, and solved the problems; what increased their learning; how they communicated; and what assumptions shaped their actions.

Figure 6.12 provides a summary of the ground rules for operating an action learning set, while Figure 6.13 provides a summary of the advantages and applications of one-to-one learning methods.

FIGURE 6.12: GROUND RULES FOR OPERATING AN ACTION LEARNING SET

- Ground rules may be developed by members

- Ground rules may be changed following discussion by the members

- Equal time should be allotted to each member

- Action plans should be agreed

- All members should make a commitment to attend

- Each member’s project is dealt with in turn

- Members need to develop the skill of listening and receiving information

- The facilitator should clearly explain what he or she is looking for from the presentation so that the other members can focus their attention

- Feedback should be conducted in a constructive and supportive spirit, which may require the development of these skills

- Issues discussed in the set should be confidential

- It is valuable when identifying a problem to be used for action learning to be clear what it is about and what measures are going to be used to judge the level of achievement.

- Identify the benefits associated with addressing the problem. If you cannot identify any then there will be little motivation to resolving the issue and the energy will dissipate.

- Choose a problem that is important to you and your organisation. If the problem is perceived to be trivial then it will not occupy your attention and energies nor will it be something the organisation will actively support in terms of time and resources.

- Set yourself benchmarks to assess your progress in resolving the problem; this may also be done through consultation with other people who may have a vested interest in your quest.

- Try and forecast possible difficulties that might arise, and work out strategies for overcoming these. One of the reasons the problem exists is probably that there are a number of difficulties that have previously prevented any action being taken on the problem.

- It is essential to the success of the action-learning programme that there is commitment and openness across the organisation and particularly from the top. Without support, attempts to address problems will be stifled and pushed to the periphery where they will be forgotten about.

Adapted from Beard and Wilson (2002).

FIGURE 6.13: ADVANTAGES & DISADVANTAGES OF ONE-TO-ONE & TEAM-BASED LEARNING METHODS

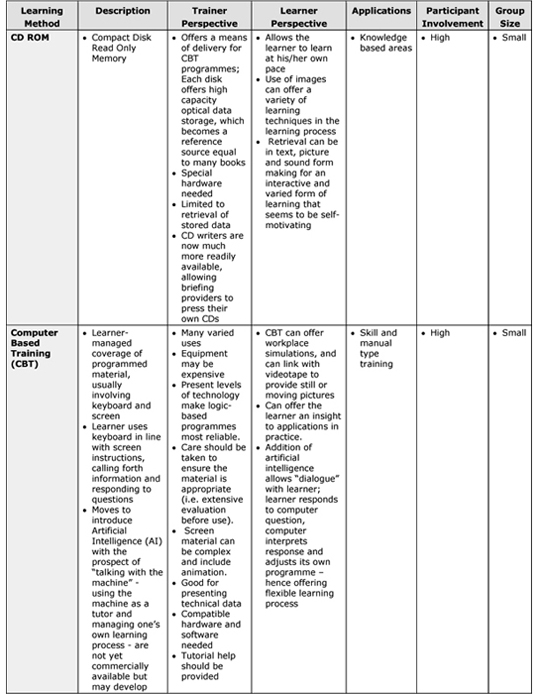

Technology-Based Methods

Open Learning

Open learning is used increasingly in organisations. The earliest open learning approaches were texts of the “teach yourself” type and postal correspondence schools. Many colleges now run open learning centres in parallel with more traditional courses. Some companies have set up open learning centres, so that employees at all levels can follow a variety of vocational and general education courses.

The growth in open and distance learning reflects a change in working practices. First, fewer employers are prepared to give day release to employees and, even if they do, the employees may not feel able to do their jobs in four days a week. Secondly, employees frequently have evening commitments that prevent them from attending conventional courses; many people prefer to study on their own with occasional lectures and tutorials.

One of the disadvantages of any open-learning package is that the learner may drop out because of the lack of personal contact on an ongoing basis either with a tutor or other learners. However, the more progressive open-learning providers have developed high-contact programmes to overcome this.

Programmed Learning, Computer-Based Training And Interactive Videos

These represent specialised forms of open learning. In Programmed Learning, students are tested when every point is made, either by a write-in or multiple-choice question. The aim is to ensure that the student normally answers the question correctly, but that the questions are not trivial. Programmed learning can be presented either in books or on machines. The problems are that programmes take a long time to write and that few authors can achieve the appropriate adult-to-adult tone.

Computer-based training is automated programmed learning. It has the advantage that it is relatively easy to write branches that fill in gaps or correct errors in the student’s knowledge. The disadvantages are that a computer screen holds relatively few words and that writing requires a skilled trainer.

Interactive video is programmed learning combined with moving pictures. It is potentially a very powerful teaching medium. Effective programmes have been written on social skills, such as how bus drivers should deal with difficult passengers. However, at present there are several technical limits to the amount of material that can be presented on a disc.

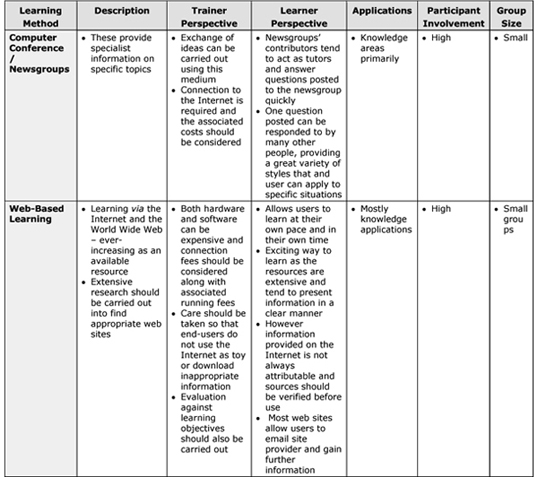

Figure 6.14 presents the advantages and limitations of project and technology-based methods from you and your learner’s perspectives.

FIGURE 6.14: ADVANTAGES & DISADVANTAGES OF TECHNOLOGY-BASED METHODS

BEST PRACTICE INDICATORS

Some of the best practice issues that you should consider related to the contents of this chapter are:

- The T&D annual plan, and plans at unit and operational levels are implemented through well-chosen learning experiences and processes across the organisation

- The T&D process ensures active involvement of stakeholders throughout the design, delivery and evaluation of planned learning experiences

- Such experiences include not only formal training and education programmes, but also a wide range of development methods and processes that can be tailored to the needs of individuals and teams

- Learning initiatives to enhance and improve performance continuously, respond in appropriate ways to identified T&D needs

- Best practice is regularly incorporated into the design and delivery of planned experiences. Major initiatives are benchmarked to ensure excellent and efficient use of resources

- Induction and basic skills training at all organisational levels are the shared responsibility of managers and mentors, with relevant support from specialist training and development staff

- High quality induction and basic skills training are well integrated. They are systematically and consistently applied across the organisation for all new entrants, and for those new to jobs and roles

- T&D coverage meets needs for continuous development and flexibility, and for change. It ensures timely responses to new business activities and processes, and to the emergence of critical issues in the workplace

- Career planning and development is an integral part of the organisation’s T&D strategy to stimulate and enhance performance in the workplace

- Benchmarking can also help you identify learning methods and activities that may be valuable in your organisation. To do this, you should:

- Identify clearly the activity or process where there is a need to improve performance in your organisation

- Identify a similar process either elsewhere in your organisation, or in another organisation, where they achieve more satisfactory outcomes. Concentrate on finding a similar process or activity, not content. Think creatively – for instance, when the UK Prison Service wanted to improve how it dealt with queues of prisoners it benchmarked its process with the Post Office Counters

- Analyse how people in your organisation learn to deal with the process, and how people in your selected benchmark organisation learn to deal with the same process

- Consider how the learning process in the benchmark organisation could be transferred to your organisation.

- You should balance your learning methods in any one session to ensure that there is a good combination of active and passive methods.