6. Rachel Carson’s Health Scare

Roger E. Meiners

Rachel Carson begins Silent Spring by reminding her readers of a simpler, happier time: “There was once a town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings.”1 But as “A Fable for Tomorrow” continues, she forecasts a grim future: children stricken while playing and dying within a few hours, no fish living in the stream, chicks not hatching, few birds heard, no bees pollinating, and vegetation turning brown and withered. Although she explains that the story is just a fable and no town had suffered such a fate, she cautions, “Yet every one of these disasters has actually happened somewhere, and many real communities have already suffered a substantial number of them.”2 This “grim specter has crept upon us almost unnoticed” and “may easily become a stark reality we all shall know.”3 To catch a reader’s imagination and attention, it is hard to imagine a more effective opening.

The view of a formerly healthy and happy America expressed at the opening of Silent Spring was not new, as Desrochers and Shimizu discuss in Chapter 3. And as Nelson discusses in Chapter 4, some people today take as an article of faith that heaven on earth has been despoiled by modern technology. Nostalgia is a powerful theme— nostalgia for a time when families gathered to read in the evening by candlelight and everyone communed with nature, suggesting we have been fools to think we could improve upon the natural state of affairs enjoyed by our ancestors. But nostalgia ignores the improvements to living standards that accompany the disruptions of change.

When Rachel Carson was born in 1907, life expectancy was about 49 in the United States, the same as enjoyed in Guinea-Bissau and Chad today.4 When Carson was writing Silent Spring, life expectancy in the United States had risen by more than 20 years.5 Americans were healthier and wealthier than ever. She knew that. But her world view was a glass half empty and going dry. Exactly why were we headed for the environmental cliff? Carson writes, “This book is an attempt to explain.”6 This chapter considers the major human health issue she raised.

Better Living through Chemistry

Chapter 3, titled “Elixirs of Death,” opens with the following ominous statement:

For the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals, from the moment of conception until death. In the less than two decades of their use, the synthetic pesticides have been so thoroughly distributed throughout the animate and inanimate world that they occur virtually everywhere.7

Subsequent chapters elaborate on this theme with respect to the impact of pesticides on birds and other creatures. Carson believed that “natural cancer-causing agents are still a factor in producing malignancy; however, they are few in number.”8 What explained the increase in cancer she observed in her lifetime? She believed it was the effect of pesticides and other man-made (synthetic) chemicals:

No longer are exposures to dangerous chemicals occupational alone; they have entered the environment of everyone—even of children as yet unborn. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that we are now aware of an alarming increase in malignant disease.

The increase itself is no mere matter of subjective impressions. The monthly report of the Office of Vital Statistics for July 1959 states that malignant growths, including those of the lymphatic and blood-forming tissues, accounted for 15 per cent of the deaths in 1958 compared with only 4 per cent in 1900. Judging by the present incidence of the disease, the American Cancer Society estimates that 45,000,000 Americans now living will eventually develop cancer.9

The U.S. population in 1960 was 180 million, hence the title of Chapter 14, “One in Every Four.”

The 20th century saw an increase in cancer deaths and death rates in the United States as in other developed countries. However, Carson ignored major factors in evaluating the matter. First, the population by 1958 was 175 million, compared to 75 million in 1900. Thus, all else being equal, the number of deaths (but not death rates) would have increased. Second, the 20th century saw a continual decline in all-cause death rates (see Figure 6.1). Consequently, life expectancy had increased from 47.3 years in 1900 to 69.6 years in 1958.

Relatively few young people die from cancer. The risk of death from cancer increases sharply with age.10 Because people were living longer, cancer was becoming a more common cause of death until near the end of the 20th century, when improved diagnosis and treatment stemmed the tide, along with the gradual decline in smoking.

Figure 6.1

U.S. CRUDE DEATH RATES FOR ALL CAUSES AND CRUDE

DEATH RATES FOR CANCER (PER 100,000 POPULATION)

SOURCES: Jiaquan Xu et al., “Deaths: Final Data for 2007,” National Vital Statistics Reports 58, no. 19 (2010), www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/ nvsr58/nvsr58_19.pdf; “Leading Causes of Death, 1900–1998,” www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/lead1900_98.pdf; and Health, United States, 2010, (Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2011),www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus10.pdf#032.

Because of its increasing prevalence, cancer was high on the public health agenda in the 1950s.11 There was substantial debate at that time over the cause of the increase in cancer death rates—was it smoking or some other substance?

Silence on Tobacco Smoking

Silent Spring entirely ignores the debate. Carson indicts manmade “new chemical and physical agents” against which man has “no protection” as these “powerful substances . . . easily penetrate the inadequate defenses of the body.”12 Not once does she mention that smoking tobacco might be a carcinogen. The closest Carson comes to suggesting a connection to smoking and cancer is when she mentions that arsenic compounds are known to cause cancer. She suggests that use of arsenic-based pesticides (which was common in the pre-DDT era) in tobacco farming could lead to increased cancer, not because of smoking but because of exposure to arsenic.13

The relationship between smoking and cancer was under active debate when Carson was writing Silent Spring. For example, between January 1, 1959, and March 31, 1962, the New York Times carried 133 articles dealing with “smoking” and “cancer.” These pieces carried headlines ranging from, “War on Smoking Asked in Britain; Royal College of Physicians Links Cancer of Lung to Heavy Cigarette Use; Curb on Ads Is Sought; Report Also Terms Tobacco Factor in Heart Disease, Bronchitis and TB”14 and “New Study Adds Data on Smoking, Confirms Cancer-Tobacco Link,”15 to “Experts on Cancer Voice Differences on Heavy Smoking.”16

Perhaps Carson overlooked this controversy because she adopted as her cancer guru Dr. Wilhelm Hueper, a protagonist in the debate over the cause of increasing cancer. Originally from Germany, Hueper was a distinguished pathologist who did major work on occupational and environmental cancer that is heralded for its quality.17 However, at the time Carson was writing, he firmly believed environmental contaminants were the culprits; tobacco smoking was not a concern.18

From today’s vantage point, most people would scoff at Hueper’s ideas. However, an Internet search of his name yields evidence of adherents who still preach that doctrine: chemicals cause cancer. There is a conspiracy between the government, chemical makers, and research scientists who are on their payrolls. Books, such as The Secret History of the War on Cancer,19 tell all about the corporate profiteers and their toadies in government who suppress the truth about cancer. Science makes little difference for those who hold such ideas as a matter of faith (see Chapter 4).

Given the state of knowledge at that time, Hueper had reasons for his skepticism of the tobacco hypothesis.20 Talley et al. suggest that the controversy over the role of tobacco in cancer was not considered settled until publication of the Surgeon General’s report, Smoking and Health, in 1964.21 Other observers claim that the controversy in the scientific community over smoking as a major cause of cancer was settled well before official government recognition was pronounced.22

Carson, ignoring tobacco, clearly implies that many entomologists supported the use of chemical pesticides for pecuniary reasons:

The major chemical companies are pouring money into the universities to support research on insecticides. . . . Inquiry into the background of some of these men reveals that their entire research program is supported by the chemical industry. Their professional prestige, sometimes their very jobs depend on the perpetuation of chemical methods. Can we then expect them to bite the hand that literally feeds them? But knowing their bias, how much credence can we give to their protests that insecticides are harmless?23

It seems to have escaped her that her cancer guru, Hueper, as a professional researcher at a university that received grants, could have been susceptible to the same failing. In any case, her statement about the researchers constitutes an ad hominem attack on people with opposing viewpoints rather than an argument based on the science and the facts. It is difficult to believe she was unaware that the majority of the relevant cancer researchers were sure tobacco was a major culprit among the causes of cancer, despite tobacco company funding of some research.

The Contribution of Environmental Contaminants to Cancer

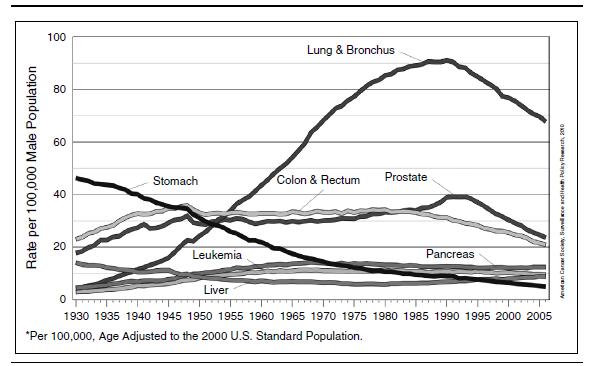

Various quotations from Silent Spring indicate that Carson believed that man-made carcinogens in the environment were responsible for the bulk of the increase in cancer during the 20th century and that, in the future, cancer could strike “one in every four” Americans. However, once cancer death rates are adjusted for the aging of the population, and confounding factors such as smoking and diet are considered, cancer death rates did not show upward trends.24 Cancer death rates for nonsmokers aged 35–69 declined at least from the 1950s onward, at just about the time they should have been increasing if synthetic pesticides (such as DDT) were the major cause of cancer.25

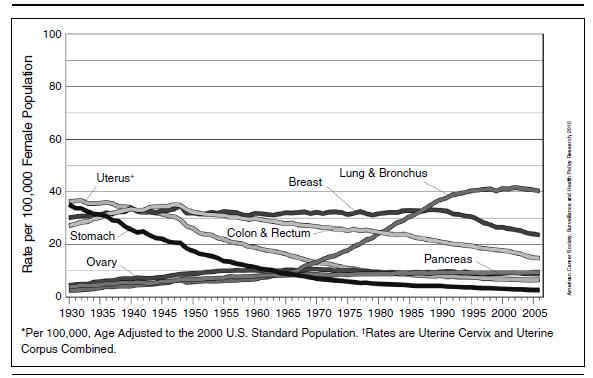

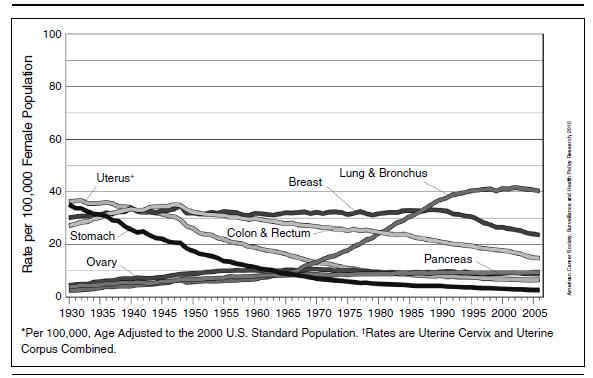

Similarly, age-adjusted cancer death rates for all cancers, excluding lung and bronchus, declined from 1950 to 1990 for all age groups except those above 85.26 The decline ranged from 71 percent for the 0–4 year age group and 8 percent for the 74–85 year age group.27 The declines would have been greater if only nonsmoking-related cancers were considered, since smoking is also implicated in cancer of the mouth, esophagus, pancreas, bladder, leukemia, and possibly colon,28 as suggested by Figures 6.2 and 6.3.

Figure 6.3

AGE-ADJUSTED CANCER DEATH RATES (FEMALES, BY SITE,

1930–2006)

NOTE: Due to changes in ICD coding, numerator information has changed over time. Rates for cancer of the lung and bronchus, colon and rectum, and ovary are affected by these coding changes.

SOURCE: American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts & Figures, (2010), http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/ documents/document/acspc-026209.pdf.

Carson did not have the benefit of the Internet to look up the graphs here, which were compiled by the American Cancer Society, but she did have available the annual mortality data cited by the Cancer Society for 1930 and forward. A leading killer of women was cancer of the uterus. Carson could have eyeballed the data to see the trends. For example, the data for 1936 lists 16,280 deaths from malignant uterine cancer.29 By 1956, the raw (not age-adjusted) number was 9,690.30 Could Hueper and Carson have been blind to the fact that lung cancer among men was the only form of cancer rising rapidly among men in the 1950s, while among women it barely moved? They breathed the same air. We now know, as did most researchers by 1960, that lung cancer jumped because the percentage of men who smoked increased significantly during World War II. The share of women addicted to tobacco did not rise as rapidly until the liberating 1960s, so lung cancer shows up later among women.

In their authoritative paper on the causes of cancer in the United States, published 19 years after Silent Spring, Richard Doll and Richard Peto31 estimate that less than 1 percent to as much as 5 percent of cancer deaths were due to pollution (with a best estimate of 2 percent). For occupational exposures, they estimate a range of 2 to 8 percent (best estimate of 4 percent). They also calculate that the share of cancer deaths due to tobacco was 30 percent and to diet, 35 percent.

Although the Doll and Peto estimates are generally accepted, not all researchers agree with them. Clapp et al. note that other scholars estimate that occupational hazards could contribute as much as 10 percent of cancer incidents.32 In a later survey article in Nature in 2001, Peto provides fresh estimates of the share of cancer deaths that could be attributed to specific causes and avoided through appropriate interventions (see Table 6.1).33 Peto’s estimates show that more than half of cancer deaths among nonsmokers are unavoidable (based on current knowledge). For smokers, the corresponding figure is 25 percent. Smoking accounts for 60 percent of cancer deaths among smokers. Reduced air pollution, better occupational controls, and sunlight avoidance could lower cancer deaths by 1 percent among smokers and 3 percent among nonsmokers.

Table 6.1

U.S. CANCER DEATHS AVOIDED BY ELIMINATING KNOWN RISKS

| |

Deaths (percent avoided after removing each cause) |

| |

|

| Cause |

Current Smokers |

Nonsmokers |

|

| Smoking |

60 |

– |

| Known infections |

2 |

5 |

| Alcohol |

0.4 |

1 |

| Sunlight |

0.4 |

1 |

| Air pollution |

0.4 |

1 |

| Occupation |

0.4 |

1 |

| Lack of exercise |

0.4 |

1 |

| Diet (overweight) |

4 |

10 |

| Other dietary factors |

4–12? |

10–30? |

| Presently unavoidable |

25 25 |

>50 |

|

SOURCE: Julian Peto, “Cancer Epidemiology in the Last Century and the Next Decade,” Nature 411 (2001): 390–95.

More recently, in a survey of cancer trends in France, Boffetta et al. come to qualitatively similar conclusions.34 They attribute 2.4 percent of cancer deaths in France to occupation, 0.7 percent to ultraviolet light, and 0.2 percent to pollution. By contrast, they attribute 23.9 percent to smoking, 6.9 percent to alcohol, and 3.6 percent to infectious agents.

In sum, the scientific evidence of a half-century has not borne out Carson’s notion that man-made environmental carcinogens would cause an explosion of cancer. Why did she think this was happening? She believed it was because of “man’s search for a better and easier way of life” and “because the manufacture and sale of such chemicals has become an accepted part of our economy.”35 That is, unless we returned to the days of (alleged) harmony with nature, we would pay the price.

What accounts for the disparities between Carson’s prognostications about cancer and the current understanding of the causes of cancer? Perhaps she was misled by a misconception combined with a hypothesis. The misconception was that natural carcinogens “are few in number and they belong to that ancient array of forces to which life has been accustomed from the beginning.”36 The hypothesis may have been that since these new synthetic pesticides were designed to kill various organisms, they could cause biological changes in humans, and humans had not yet developed defense mechanisms against their toxic effects.37

Since publication of Silent Spring, however, research has shown that 99.99 percent of the carcinogens we ingest are natural in origin.38 Plants manufacture them to defend against pests that would otherwise injure or kill the plant. That is, they are the products of plants’ self-defense mechanisms. That does not mean that natural carcinogens do not harm humans. Belladonna and many other plants are toxic. Just as natural species produce chemicals to defend themselves from harm, human beings often rely on synthetic pesticides to help protect them from harm. This harm includes death and disease from vector-borne diseases, such as malaria, and loss of food supply (which is the first line of defense in ensuring and maintaining public health).

At the high doses at which chemicals are tested for carcinogenicity in rats, about half of natural chemicals are carcinogens—the same percentage as for synthetic chemicals.39 The high doses in these animal studies cannot, without heroic assumptions, be extrapolated downward to the much smaller doses received by the general public. Similarly, much of the data on acute and chronic doses that Carson relied on came from studies in occupational settings where, typically, much higher doses than the general population is exposed to are found.40 Even if rats are a good model for human beings when it comes to cancer—which is debatable—the contribution of synthetic chemicals to cancer among the general population is slight, and certainly nothing approaching “one in every four.” As Boffetta et al. note:

Many chemicals have been postulated as human carcinogens (pesticides, dioxin, endocrine disruptors, etc.). The clinical and experimental data are, however, not consistent with a substantial role of pollution in human cancer. Moreover, the concentrations to which the public is exposed are very low and biological data show that great caution is required before extrapolating from high to low exposure. . . . Even if the action of air pollution [including fine particles] is taken into account, the total proportion of cancers attributable to pollution would not exceed 1%, a figure consistent with that reported in Nordic countries and the UK.41

Leukemia

Silent Spring singled out leukemia for special attention:

There is, however, one presently known exception to the fact that a long period of latency is common to most malignancies. This exception is leukemia. Survivors of Hiroshima began to develop leukemia only three years after the atomic bombing, and there is now reason to believe the latent period may be considerably shorter. . . .

Within the period covered by the rise of modern pesticides, the incidence of leukemia has been steadily rising. . . . In the year 1960, leukemia alone claimed 12,290 victims. Deaths from all types of malignancies of blood and lymph totaled 25,400, increasing sharply from the 16,690 figure of 1950. In terms of deaths per 100,000 of population, the increase is from 11.1 in 1950 to 14.1 in 1960. The increase is by no means confined to the United States; in all countries the recorded deaths from leukemia at all ages are rising at a rate of 4 to 5 per cent a year. What does it mean? To what lethal agent or agents, new to our environment, are people now exposed with increasing frequency?42

However, an analysis by Gilliam and Walter (published several years before Silent Spring) of trends in age-specific leukemia death rates suggests that the increase commenced in the 1920s (or earlier), before organochlorines such as DDT came on the scene.43 These death rates moderated after about 1940, with the greatest reduction in the younger age groups.44 Gilliam and Walter’s take-away message is that the “trends . . . provide no support whatsoever for a theory which postulates a sharp increase within the last 15 years in leukemogenic factors affecting the environment of Americans in general. On the contrary, the data suggest that such exposure has either become stabilized or has actually decreased during this period, if exposure to environmental factors is in fact responsible for the disease.”45

Consistent with the Gilliam and Walter study, Milham and Ossiander later showed (in a study responding to the assertion that another factor of modernity—electricity—caused leukemia) that the increases in age-specific death rates for childhood leukemia (in males) slowed down in the 1940s and peaked in the 1960s.46 Although this paper was published long after the appearance of Silent Spring, the data through the 1950s were available in public health reports at the time Carson was writing.

The Ultimate Fear: Cancer in Children

Carson raised the specter of an increasing toll of cancer among children: “A quarter century ago, cancer in children was considered a medical rarity. Today, more American school children die of cancer than from any other disease.”47 (Emphasis in original.) It is hard to imagine anything more disturbing to parents than this claim.

There are several problems with this assertion. Table 6.2 shows mortality rates from all-causes and cancer among children less than 1 year old, ages 1–4 years, and ages 5–14 years for 1900, 1935, and 1960. The major reason cancer deaths in these age groups loomed larger in 1960 than in 1935 or 1900 was less the increase in cancer death rates than the dramatic decline in all-cause death rates. Common “childhood diseases” which had killed many children were being brought under control. For instance, for the 5–14 year age group, deaths dropped from 150 per 100,000 in 1935 to 50 per 100,000 in 1960. Over the same period and for the same age group, cancer death rates increased from 2.0 to 6.8 per 100,000, a big increase in percentage terms from a relatively low base but one that is dwarfed by the large reduction in the broader context of all-cause death rates.

Table 6.2

ALL-CAUSE AND CANCER MORTALITY RATES AMONG CHILDREN

(PER 100,000 POPULATION, AGES 0–14 YEARS, 1900–1960)

|

| Age Group |

Year |

< 1yr |

1–4 yrs |

5–14 yrs |

|

| All-cause |

1900

1935

1960 |

16,240

5,740

2,880 |

1,980

370

110 |

390

150

50 |

| Cancer |

1900

1935

1960 |

3.2

3.1

7.2 |

2.9

4.1

10.9 |

1.8

2.0

6.8

|

|

NOTE: Rates are based on population in each age group.

SOURCES: Public Health Service, Vital Statistics Rates in the United States, 1900–1940 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1947), pp. 181, 250; Public Health Service, Vital Statistics of the United States, 1960 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1963), pp. 5–182, 5–192; and U.S. Bureau of Commerce, Statistical Abstracts of the United States 1961 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1961), pp. 29, 58.

Another problem with Carson’s argument in Silent Spring is that cancer is not one disease but a class of diseases. Thus, to compare all-cancer death rates with the death rate for other diseases is somewhat misleading. There is also no way of knowing if some children who died of cancer in 1960, when diagnoses were better than in earlier years, might have been classified differently in the past. That is, an individual death may involve multiple causes, but only one cause is entered in the record for statistical purposes. In earlier times, a child with cancer might well have succumbed to pneumonia or some other disease, so cancer rates may actually have been higher than reported—and not as readily recognized as in later years. Although death statistics are quite accurate, the cause-of-death statistics are a bit less accurate, and likely less so the further back in time one goes.

Even if the cancer numbers are accepted as accurate, the timing of increases in cancer death rates is inconsistent with the narrative in Silent Spring regarding DDT:

[T]he first exposures to DDT date from about 1942 for military personnel and from about 1945 for civilians, and it was not until the early fifties that a wide variety of pesticidal chemicals came into use. The full maturing of whatever seeds of malignancy have been sown by these chemicals is yet to come.48

As seen in Figure 6.1, overall cancer death rates had been increasing at least since 1900, long before DDT and other synthetic organic pesticides came on the scene. In fact, the increase in the crude cancer death rate started to moderate in the early 1950s, just after DDT and organochlorines came into widespread use.

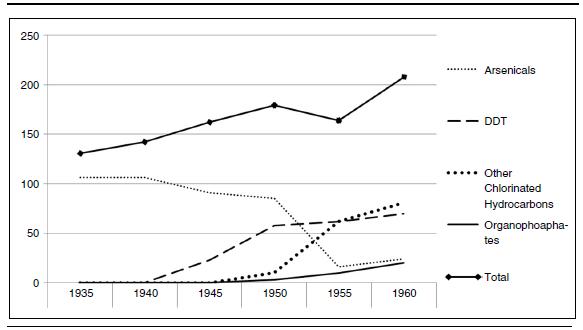

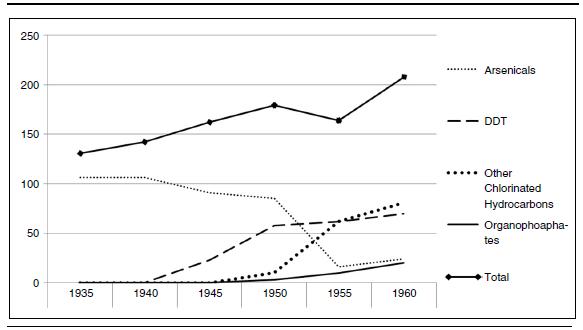

Evolving Pesticides

The use of arsenic-based pesticides waned as the new organochlorines (later largely replaced by organophosphates) came on the market. As shown in Figure 6.4, DDT and other organochlorines were rapidly displacing pesticides containing arsenic (as well as lead and other metals) by the 1950s.49 Carson did not care for any of the new products. “Can anyone believe it is possible to lay down such a barrage of poisons on the surface of the earth without making it unfit for all life? They should not be called ‘insecticides,’ but ‘biocides.’”50 She did not expressly advocate banning the products, but the implication was clear; and, as Desrochers and Shimizu discuss in Chapter 5, she was sure there were natural alternatives.

As Carson notes in Silent Spring, “One of the earliest pesticides associated with cancer is arsenic, occurring in sodium arsenite as a weed killer, and in calcium arsenate and various other compounds as insecticides. The association between arsenic and cancer in man and animals is historic.”51 Moreover, arsenic compounds were implicated in more than cancer—they were associated with conditions of the liver, skin, and gastrointestinal and nervous systems.52 One of the major arsenical pesticides was lead arsenate.53 Because arsenic compounds had long been in use, Carson portrayed the human health-related problems associated with them as being known with relative certainty.54 The consequences of organochlorines such as DDT were still speculative.55 The displacement of pesticides containing arsenic (and other heavy metal) compounds by organochlorines may have provided a public health benefit. But Carson did not explore whether the change, which she knew was occurring, might provide a silver lining to what she saw as a dark cloud.56 The failure to consider this possibility is a lapse in scientific logic.

Figure 6.4

VOLUME OF CONVENTIONAL INSECTICIDE/MITICIDE ACTIVE

INGREDIENT USAGE IN THE UNITED STATES (MILLIONS OF

POUNDS, 1935–1960)

NOTES: The major categories shown do not create the total; other minor categories are not included. Data are once every five years.

SOURCE: Adapted from Arnold S. Aspelin, Trends in Pesticide Usage in the United States, Part 4 (Raleigh, NC: Center for Integrated Pest Management, North Carolina State University, 2003), p. 19.

One of Carson’s criticisms of pesticides in general, and DDT in particular, is that they are temporary fixes: sooner or later target pests will develop resistance, and the pesticide will become ineffective.57 Pesticide users know that, so most use the products judiciously. Overusing a pesticide would not only be more costly but also reduce its long-term effectiveness. Similarly, the likelihood of resistance provides an incentive for pesticide manufacturers to advocate prudent use to stretch the period over which they can sell their product and develop substitutes. If pests indeed became resistant, the pesticide’s use would be curtailed, which would allow the environment to cleanse itself.

Domestic DDT use had begun to decline in the late 1950s, prior to publication of Silent Spring, partly because of its decreasing cost-effectiveness relative to other options, partly because of regulations in a few states. Proof that discontinuing the use of a pesticide will indeed cleanse the environment of its pollutant load is seen in trend data for various organochlorines—DDT and its residues, aldrin and dieldrin—indicating that their concentrations have declined in the environment, in human adipose tissue, and in human breast milk by as much as an order of magnitude or more since their use was phased out (for whatever reason).58

Weak Analysis

The reader of Silent Spring would be led astray on the significance and contribution of pesticides to cancer in the United States. Carson’s lopsided view stems, in part, from her reliance on Wilhelm Hueper as her cancer guru. His views reinforced her prejudice against pesticides (confirmation bias). Her reliance on Hueper, however, is less of a problem than her silence regarding the possible role of smoking. That constitutes a sin of omission.

Other problems with the book’s cancer narrative are twofold: it failed to explore more fully the consequences of (a) replacing arsenic-based pesticides, (e.g., lead arsenate, a known carcinogen) with pesticides whose carcinogenicity was uncertain, and (b) the development of resistance to specific pesticides on the future pollution burden in the environment and in organisms. Carson compounded these failings by ignoring the effects of a longer life expectancy on cancer rates, the spatial distribution of cancer rates between rural and urban populations, and the backdrop of rapid elimination of many of the biggest causes of deaths, which automatically magnified the relative importance of cancer. Had she considered these elements, her perception of the urgency of the pesticide problem perhaps might have diminished. Contrary to the suggestion in a July 1962 New York Times editorial—that Carson might have good reasons for ignoring the benefits of pesticides59—there was little scientific basis for these oversights.

Since Carson’s condemnation of DDT, numerous studies have been done to establish the relationship, if any, between DDT (and its metabolites, DDD and DDE) and cancer. As the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry reports, “Issues inherent to epidemiological studies, such as the role of cofounders [sic60] for example, make it difficult to draw definite conclusions about exposure to DDT/DDE/DDD and cancer. However, taking all factors into consideration, the existing information does not support the hypothesis that exposure to DDT/DDE/DDD increases the risk of cancer in humans.”61 Notably, the Environmental Protection Agency classifies DDT, DDE, and DDD as probable human carcinogens; the International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies them as possible human carcinogens; and the Department of Health and Human Services has determined that they may be anticipated to be human carcinogens.

Thus, even after more than a half century of work, the status of DDT as a carcinogen remains shrouded in uncertainty, suggesting that public policy might better focus on substances where the evidence of a marked negative effect is clearer. As Roberts and Tren explain in this volume, DDT continues to be an effective weapon in many locales and situations against malaria and other vector-borne diseases. Efforts to discontinue its use for public health purposes are misguided and clearly not based on the evidence of DDT’s benefits when it is properly applied.62

Ambivalence about the Use of Chemical Pesticides

In Silent Spring, Carson explains that she is not against the use of chemical pesticides, only their overzealous application by users unaware of their “potentials for harm”63—and who could disagree with that? But she attributes only horrors to pesticides and notes that even exposure to “one molecule” might be problematic.64 Carrying this thought to its logical conclusion, she argues that

to establish tolerances is to authorize contamination of public food supplies with poisonous chemicals. . . .

But if . . . it is possible to use chemicals in such a way that they leave a residue of only 7 parts per million (the tolerance for DDT), or of 1 part per million (the tolerance for parathion), or even of only 0.1 part per million as is required for dieldrin on a great variety of fruits and vegetables, then why is it not possible, with only a little more care, to prevent the occurrence of any residues at all? This, in fact, is what is required for some chemicals such as heptachlor, endrin, and dieldrin on certain crops. If it is considered practical in these instances, why not for all?65

For practical purposes, a “no-residue” policy is tantamount to a no-use policy. Essentially, Silent Spring’s rhetorical question was an articulation of the Delaney Clause (a zero-risk standard imposed on the Food and Drug Administration that was so impractical Congress had to repeal it). It lives on in present day environmentalists’ version of the precautionary principle, as Katzenstein and Marchant discuss in their respective chapters.

Can this apparent contradiction within Silent Spring—between acknowledging a role for pesticides while arguing for a no-residue policy—be reconciled? Perhaps, if “no residue” meant no measurable residue based on the detection technology available in the early-1960s (and no one could have anticipated that subsequent advances in technology would lower detection levels by orders of magnitude). But even that rationale runs counter to the “one molecule” narrative.

From a practical perspective, the contradiction could be reconciled by attempting to balance the risks of not using pesticides against those of using them. Many of Carson’s disciples are reluctant to do such balancing, as is evident from the events preceding the decision to allow a public health exemption for DDT in the Stockholm Convention’s ban on persistent organic pesticides and continuing efforts since then to eliminate DDT completely. This campaign continues despite the broad range of public health benefits that DDT can provide.66 Given Carson’s contradictory statements, it is unclear whether she would oppose an attempt at balancing.

Endless Threats

During Carson’s life, the use of chemicals and metals in the United States rose from the modest levels that would be expected of a country with a low standard of living in 1900 to the higher levels needed for ordinary people to enjoy a better life by 1960. Figure 6.5 shows that between 1900 and 1960, despite the five-fold increase in the use of primary metals (ranging from aluminum to beryllium to cadmium to indium to mercury to selenium to tin to zinc) and a 30-fold increase in the use of nonrenewable organic compounds (ranging from asphalt to lubricants to petroleum coke to benzene to ethylene to xylene), U.S. life expectancy increased steadily (from 49.2 years in 1900 to 69.9 years in 1960). Cancer increased over those decades as well, but little evidence attributes that rise to the substances tagged by Carson. Whatever public health problems may have been created or exacerbated by the mass production and use of metals and nonrenewable organics, technological developments and economic progress reduced public health problems overall.

Figure 6.5

U.S. TRENDS IN USE OF SYNTHETIC ORGANIC CHEMICALS AND

PRIMARY METALS COMPARED TO LIFE EXPECTANCY (1900–1960)

SOURCES: Grecia R. Matos, “Use of Minerals and Materials in the United States from 1900 through 2006,” U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2009–2008, http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2009/3008/; and National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Decennial Life Tables for 1989–1991, vol. 1, no. 3 (Hyattsville, MD: CDC, 1999), http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/lifetables/life89_1_3.pdf.

These data cast doubt on the premise inherent in the question in Silent Spring: “The question is whether any civilization can wage relentless war on life without destroying itself, and without losing the right to be called civilized.”67 This rhetorical question suggests another: whether any civilization that hobbles new technology that could reduce hunger and disease, on the chance that the new technology might have negative consequences—essentially giving up a real bird in hand for a hypothetical bird in the bush—should lose the right to be called civilized.

Conclusion

Desrochers and Shimizu (Chapter 5) identify several shortcomings in Carson’s Silent Spring that stem from major omissions. These include her silence on the benefits of chemical pesticides, such as higher agricultural production—which reduced hunger in a world of chronic starvation and limited the loss of wildlife habitat. Another flaw is her reliance on anecdotes rather than systematic analysis of available information. But perhaps the book’s biggest failing is its discussion of cancer.

Carson attempted to create in the reader’s mind the impression that pesticides (and other man-made chemicals) were the drivers of the increase in cancer deaths in 20th-century America. At the time she was writing Silent Spring, the causes of cancer and the relative role of various potential causes were widely debated. Yet Carson was silent on that debate. She focused on the views of a researcher whose ideas matched her own. She omitted any discussion of the role of smoking and compounded that sin by engaging in unbalanced speculation on how pesticides and other pollutants might lead to an increase in cancer (accompanied by a few well-told anecdotes).

She overlooked relevant factors affecting the overall impact of organochlorine pesticides on cancer rates. For example, she should have considered the net result of replacing arsenic-based pesticides— known carcinogens—with organochlorine pesticides of uncertain carcinogenicity. Besides ignoring risk tradeoffs, Carson also overlooked key factors that magnified the 20th-century increases in cancer death rates relative to all-cause death rates. The spectacular reduction of many causes of death meant that cancer death rates automatically accounted for a larger share of deaths. That increase in share was further exaggerated because people were living longer and because cancer deaths are compounded with increasing age. An increasing cancer death rate can be a sign of society’s success in reducing deaths from diseases that are more prone to strike younger people. This is one reason why, despite increases in cancer deaths, life expectancy has continued to improve in the half century since the publication of Silent Spring.

Today we know that—contrary to Carson’s speculation—while man-made pollutants (in general) and chemical pesticides (in particular) can increase cancer deaths, they contribute only a small fraction of total cancer deaths and an even smaller fraction of all-cause deaths. As life expectancies continue to increase and medical science advances, the share of deaths attributable to cancers will also likely increase—we must all die of something eventually.

Finally, although Carson claimed that she was opposed not to chemical pesticides but only to their misuse, her book suggests that exposure to even “one molecule” might be problematic, and her rhetoric is consistent with a zero-residue policy. This apparent inconsistency might be resolved by balancing the risks of not using pesticides against the risks of using them. Many environmentalists today oppose such balancing and indulge in one-sided application of the precautionary principle to justify a ban on life-saving chemicals. It is unknown whether Carson would be among them.

The National Academy of Engineering, a part of the National Academies, uses Silent Spring in its online ethics training for engineering and research: “Undaunted by the chemical companies’ hostility and by the public’s high enthusiasm for pesticides, she wrote a book called Silent Spring, which caused a major shift in public consciousness about the environment.”68 If the scholarship evidenced in Silent Spring is a paragon of judicious research then we have fallen victim to what Robert Nelson in his chapter calls a “secular religion” in the guise of science.

25

25