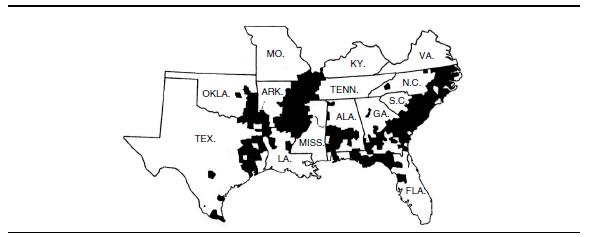

Figure 8.1

MAP OF U.S. COUNTIES WHERE HOUSES WERE SPRAYED WITH

DDT FOR CONTROL OF MALARIA (1946–1947)31

SOURCE: U.S. Public Health Service, Atlanta, Georgia, 1948.

8. Did Rachel Carson Understand the Importance of DDT in Global Public Health Programs?

Donald R. Roberts and Richard Tren

Introduction

Memories of DDT and its controversies have faded. Many who do remember may be tempted to think any talk of need for DDT is an anachronism of a bygone era. Some may remember Joni Mitchell’s classic and catchy song “Big Yellow Taxi,” where she implores farmers to “put away the DDT now, give me spots on my apples, but leave me the birds and bees, please.”

It may be unreasonable to expect Joni Mitchell to sing about the benefits of DDT and the astonishing way in which it saved countless millions of lives from insect-borne diseases. Mitchell was a folk singer and artist, and few people would expect from her a balanced, nuanced, science-based treatment of insecticides. Rachel Carson, however, promoted herself as a scientist; and at its time of publication, Silent Spring was—and even now is still—considered by many as a scientific treatise.

Silent Spring achieved its iconic status largely through its long and involved critique of DDT and other man-made chemicals. However, as we explain in this chapter, Rachel Carson’s poetic vilification of DDT reveals a serious ignorance about the chemical and the way it works. Carson’s interpretation of the development of insecticide resistance is fundamentally flawed, and the book is littered with statements about insect biology and evolution that are false and misleading. She hardly recognizes the great benefits, most dramatically in public health, that DDT provided for mankind—even though those benefits were widely known at the time. Still, a generous and sympathetic historian might excuse this important omission, concluding that Carson genuinely believed that the benefits were overstated and that DDT made the fight against diseases and crop pests more difficult. But excusing Carson on the basis of beliefs reveals a fundamental flaw of Silent Spring. The scientific record shows DDT’s benefits were not overstated, and the fact that it is still needed and remains a superlative disease-control chemical even today attests to its extraordinary benefit to humanity. Any fair examination of Silent Spring will reveal that Carson’s arguments against DDT were scarcely more serious than those of Joni Mitchell, while the lasting legacy of her book for countries and communities reliant on DDT has been devastating.

We have collaborated on this chapter, and on other publications that have strongly defended the use of DDT for malaria control, and have been critical of groups and individuals that seek to prevent or halt the use of this chemical and others in malaria control programs. We each arrived at this common point from divergent paths. Roberts’s interest in DDT evolved slowly in the 1960s and 1970s. He studied malaria and malaria control programs in Brazil during the 1970s. His collaboration with Brazilian researchers on how DDT protected people inside sprayed houses led to a startling finding that DDT functioned mostly as a powerful repellent, stopping mosquitoes from entering houses and transmitting disease while people slept. The research eventually culminated in a major paper detailing a model on how DDT actually functioned to control malaria.1 That research experience changed his professional life because DDT’s spatial repellent action made it unique among all man-made insecticides. Today, the modern arsenal of public health insecticides includes no chemical equivalent to DDT as a spatial repellent or as a chemical that will continue to protect people in houses for months after it is sprayed on inside walls.

Roberts’s search of literature showed DDT’s repellent actions were repeatedly discovered and quantified by field and laboratory researchers, even as early as 1943. Yet those findings were systematically ignored. Environmental activists forced most malaria endemic countries to abandon DDT during the 1980s and 1990s. Disease rates increased as a result. Roberts monitored those changes as they occurred and, in response, became increasingly involved in insecticide advocacy, and DDT advocacy in particular—eventually combining his efforts with those of Richard Tren and others to restore countries’ freedom to use DDT and other public health insecticides in disease control programs.

Tren is an economist. While writing about development and environmental issues, he became engaged and interested in the way in which international treaties and agreements, spearheaded by the rich developed world, affect the poor developing world. In the late 1990s, the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants was being negotiated, and it seemed certain that DDT would be banned completely. The issue of DDT and the fight against malaria provided an excellent example of the way in which first world sensibilities affect third world lives. In researching the issue for a policy paper, in 1999 Tren travelled to northern KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, which was in the grip of a severe malaria epidemic. The epidemic’s primary cause was traced to changes in insecticide use: DDT had been removed from the malaria control program and replaced with insecticides to which mosquitoes rapidly developed resistance. The beds in all the clinics and hospitals in the region were full to overflowing, with many people, including children and pregnant women, forced to sleep on the floor or outside on verandahs. The sight of children dying needlessly made a lasting impression and kept Tren motivated to ensure that malaria programs around the world would be free to use the best and most appropriate tools for their circumstances. Then, as now, this has meant defending the right to use DDT. More than a decade later, the issue of DDT for malaria control remains controversial, and anti-insecticide activist groups along with the U.N. Environment Program are working to shut down all DDT production and use even though there is no true replacement chemical available.

The Advent of DDt

DDT was first created in 1874, 33 years before Rachel Carson was born. It was synthesized by a German graduate student, Othmar Zeidler, as part of a research project and then essentially forgotten until the 1930s, when Dr. Paul Müller re-discovered DDT and its insecticidal properties.

Müller was an employee of J. R. Geigy, a Swiss chemical company that, among other things, was searching for a commercially viable chemical to control clothes moths. In his work on this project, Müller found that flies died when exposed to DDT.2

Shortly after Müller’s discovery, World War II broke out. While most of Europe was struggling under and fighting against Nazi tyranny, the Swiss were using DDT to fight beetles. As early as 1941, Geigy scientists and other Swiss researchers had discovered that DDT was effective against a great many important insects, including body lice. The importance of this discovery should never be underestimated, as one enduring lesson of history is that insect-borne diseases flourish during times of war. Typhus, which is spread by body lice, is a leading example. Under the squalid conditions of war, the disease struck with spectacular ferocity. Typhus killed more soldiers and civilians in World War I than all the shell-fire combined.3

By 1942, the Swiss were reporting remarkable results with DDT, and reported that it killed fleas, mites, lice, and mosquitoes as well as flies.4 In verification of Swiss studies, the Allies found that DDT was toxic to lice at doses that were safe for humans. Furthermore, it remained active against lice for many days after application, depending on personal hygiene. The Americans and the British soon conducted their own toxicity tests, which confirmed the Swiss reports.5

With DDT, the Allies had a powerful tool for preventing deadly outbreaks of typhus,6 and by early 1943, the United States and British governments were working to ramp up DDT production. The U.S. military was projecting even larger DDT requirements for 1944.7 By early 1944, Geigy’s U.S. subsidiary, the Cincinnati Chemical Works, was producing DDT, along with 14 other American chemical companies and several British corporations.8

The advent of DDT in 1943 forever changed the role of typhus in warfare. Later on it would have dramatic impacts on other diseases. In a reflection of the life-saving properties of DDT as an insecticide, Müller won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1948 for his discovery.9

DDt: A Wartime Necessity

One might assume the discovery of a chemical that changed the face and outcome of warfare and revolutionized man’s ability to combat significant diseases like malaria involved extraordinary chemical wizardry. Actually, it didn’t. DDT is a remarkably simple compound, in both structure and production. Here is a technical description of its chemical production:

It was first synthesized by Zeidler on the following lines: 225 parts of chlorobenzene are mixed with 147 parts of chloral or the corresponding amount of chloral hydrate and then 1,000 parts sulphuric acid mono-hydrate are added. Whilst stirring well, the temperature rises to 60° C., and then sinks slowly to room temperature, the mass then containing solid portions. It is poured into a large excess of water whereupon the product separates in solid form. It is well washed and can be crystallized from ethyl alcohol forming fine white crystals having a weak fruity odour.10

And there it is, the most cost-effective insecticide known to man— produced in a simple two-step chemical process. This simple process produces the white crystals that, when sprayed on house walls, can stand guard and protect residents from mosquitoes and malaria for months on end.

DDT gained fame with the beginning of a typhus epidemic in Naples, Italy, in December 1943. The Allies set up DDT delousing stations in January 1944. During that month, 1,300,000 civilians were dusted at two delousing stations (72,000 on the peak day), and within three weeks the outbreak in the city of Naples was completely under control.11

Success against the typhus epidemic in Naples was an unprecedented achievement12 and particularly remarkable because the Swiss had only released the formula for DDT in 1942. From WW II onward, DDT was in common use as a powder for spraying or sprinkling into the clothing of soldiers and refugees for typhus prevention. Almost overnight, DDT went from being unknown to being a critical military necessity.

DDT played an important role in the liberation of concentration camps as well. One example was the delousing of liberated populations from the Belsen concentration camp in 1945. At the time of liberation, typhus had been rampant for four months in the camp, with an estimated 20,000 cases. Those liberated from the camp doubted that British efforts to control typhus would work.13 One former prisoner stated:

After two-three days at the hospital, we have our first encounter with the pesticide DDT. When the English soldiers enter the hospital room with sprayers filled with this product, we all look at them with contemptuous superiority. They’re planning on using this puny white powder to destroy all these millions of lice! But hundreds of the most radically conducted Entlausungs [delousing chambers that ineffectively used heat to kill body lice in clothing] hadn’t helped. Yet, right in front of our eyes, something close to a miracle starts to happen! Slowly, the incessant itching, so painful on our pus-infected, ulcerated skin, starts to vanish, and this great relief finally convinces us that we have really been liberated. O Great, Powerful Benefactor, Inventor of the White Powder!14

For many years after WW II, travelers were commonly provided a small container of DDT powder for sprinkling into underclothes to control body lice, other arthropods, and disease transmission. It became a standard issue for State Department officials.15 In spite of extensive use over many years, with untold millions of individuals directly treated or otherwise exposed, there are no documented cases of harm among WW II soldiers or war refugees who were doused with DDT to prevent typhus, or among U.S. State Department officials who, in later years, also used DDT in their underclothes to prevent typhus when they visited typhus endemic areas.

Critical uses of DDT during and immediately after the war set the stage for DDT to become a peacetime commodity and a game changer for many life style issues of the mid-20th century. We have described DDT’s impact on body lice and typhus, but another ancient burden on humanity was the ever present and vexing problem of bedbugs. Mankind had achieved little progress against bedbugs, as revealed in the following authoritative text from a public health paper published in 1945. Given the importance of the ongoing global re-emergence of bedbug infestations and modern society’s apparent inability to effectively combat the problem, the full description of DDT efficacy in control of bedbugs during that era is presented here:

Bedbugs—The superiority of DDT over all other treatments for bedbugs has now been amply demonstrated. The use of a 5 per cent DDT solution in deodorized kerosene will largely replace the expensive and dangerous hydro-cyanic acid gas fumigation and the less effective insecticide sprays.

The main advantage of DDT over pyrethrum and other sprays is its persistence. DDT sprayed thoroughly on mattresses and bedsteads will continue to kill all bugs coming in contact with it for many months. In tests at the Orlando laboratory of the Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine, infested sleeping quarters were sprayed with a 5 per cent DDT oil solution. The bugs present were exterminated and 25 vigorous bugs were put on the mattress each week for 16 weeks. Not a single living bug was recovered on subsequent examinations, but a large percentage of them were found dead on the floor under the bed.

DDT sprays have been used extensively to combat bedbugs in military barracks. The results have been uniformly and remarkably successful. Tests carried out in cooperation with the National Pest Control Association in about 20 cities have shown 10 per cent DDT dust and 5 per cent kerosene solutions when applied to infested beds and adjacent walls to eliminate the pest.

The spraying of bug-infested theater seats, railway coaches, and Pullman cars has given striking and lasting results.”16

Revealed in this text is a vivid picture of how the bedbug held forth in the everyday lives of people in the mid-1940s, even in the United States. Against that recalcitrant problem, DDT changed completely the balance of power between the “bug” and man’s desire to be rid of it. The key to DDT effectiveness was its persistence, not its toxicity. Other compounds were far more toxic, but far less effective.

DDt and Public Health in the United States

In addition to being an essential tool for protecting deployed soldiers and travelers abroad, DDT also became an indispensable commodity for protecting the lives and health of people in the United States. At the turn of the 20th century, the continental United States was intensely malarious. The disease was an immense cause of human death, human illness, and economic loss. In 1916, malaria was estimated to reduce economic productivity in the United States by $100 million (in 1916).17 The economic loss from malaria in the state of California alone was estimated to be $3 million, and California was not even considered a highly malarious state.18 A conservative estimate of malaria cases for the country as a whole was one million or more cases per year.19

Malaria rates declined gradually in the United States through the first half of the 20th century, with occasional increases as a result of war and other events. The overall decline was in large part due to improvements in housing, better standards of living, and improved control of mosquito-breeding sites, which together reduced contact between man and mosquito. Notwithstanding this trend, during the 1940s, infectious diseases still caused major public health problems throughout the country. In the southeastern states, malaria control was possible only in urban settings where draining and eliminating aquatic habitats for mosquitoes and using larvicides to kill mosquito larvae was cost-effective. In contrast, the only real progress made in poor rural areas was screening houses to prevent mosquitoes from entering and transmitting disease.20

The office of Malaria Control in War Areas was created in 1942 right after the bombing of Pearl Harbor “to prevent or reduce malaria transmission around Army, Navy, and essential war industry areas [in the United States] by extending the control operations carried on by military authorities within these reservations.”21 Spraying houses with DDT quickly became established within the program as the most effective method of stopping malaria transmission in and around military installations in the United States.

Then, beginning in 1945, the MCWA launched its Extended Program of Malaria Control. This program was not limited to military posts, camps, and stations, but instead was extended to more malarious civilian areas.22 It consisted of spraying DDT on interior walls of homes and privies. The spraying program covered large areas of the southern United States. From January 1945 to September 1947, 3.2 million houses were sprayed.23 This number apparently did not include houses sprayed through use of local funds. As described in a 1946 report, “a number of larger cities have contributed sufficient funds to spray the cities in the 2,500–10,000 population group. The entire cost of this type of residual house spraying is paid from local funds.”24 After 1945, investigators discovered they could increase performance and get longer protection by spraying a greater concentration of DDT on house walls. Thus, as a result of the change in formulation, the number of sprayings per house varied from nearly 2.0 in 1945 to 1.5 in 1947.25

The MCWA was a wartime organization. With demobilization of military forces in 1945 and 1946, the MCWA went into a phase of rapid liquidation.26 That led to the creation of the Communicable Disease Center (now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) of the U.S. Public Health Service on July 1, 1946.27 The CDC was created to capture the unique resources and expertise of the MCWA and was tasked with continuing and expanding MCWA programs in all areas of public health in the United States.28

The MCWA’s Extended Program of Malaria Control had already been successful in reducing numbers of malaria cases in areas where houses were sprayed (see Figure 8.1).

To build on that success, the CDC started a National Malaria Eradication Program, commencing operations on July 1, 1947. It was referred to as the Residual Spray Program, and spraying DDT on inner walls of rural homes in malaria-endemic counties was the key component. From July 1947 to the end of 1949, the program sprayed over 4,650,000 houses. On the basis of surveys conducted in 13 southeastern states, the CDC concluded that “over-all control (reduction in houses infested) was approximately 90 percent for the 5-year period [1945–1949].”29

Overall, beginning in 1945,30 millions of houses were sprayed for malaria control throughout the southern United States. DDT spraying broke the cycle of malaria transmission and, in 1949, the United States was declared free of malaria as a significant public health problem.32 Despite this background of accomplishments from the use of DDT, arguments still abound that DDT was not a factor in malaria elimination from the United States.

Figure 8.1

MAP OF U.S. COUNTIES WHERE HOUSES WERE SPRAYED WITH

DDT FOR CONTROL OF MALARIA (1946–1947)31

SOURCE: U.S. Public Health Service, Atlanta, Georgia, 1948.

One such argument is presented in The Fever, in which author Sonia Shah states, “By the time . . . the United States created the Malaria Control in War Areas program in 1942 (which would later become the Centers for Disease Control), the weaknesses of their antimalarial methods didn’t matter anymore. Malaria had already nearly vanished.”33 The author is not alone in this assessment and like her colleagues is seriously wrong in her conclusion. As described above, malaria control was only possible in urban settings; in poor rural areas, the only option was to screen houses to prevent mosquitoes from entering and transmitting disease. Unfortunately, screening required rural people to spend money they didn’t have.

In fact, malaria was still an entrenched problem at the time broad spraying began. As late as 1945, for example, Arkansas reported 1,182 malaria cases. With spraying of houses in 1945, malaria cases dropped to 849 in 1946. Those statistics are for just one of several states with deeply entrenched rural malaria. Broad spray coverage provided other health benefits, too. In 1945, Missouri sprayed 85,000 homes, and from 1945 to 1946, numbers of cases of fly-borne diseases dropped by 66 percent in sprayed areas.

The author of The Fever should have perused some original sources of historical data. As we explain below, Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring when the memory of these successes was much more fresh, and although she gives a restrained nod to DDT’s role in malaria control, she is dismissive of the whole idea of using chemicals in disease control.

The remarkable successes against malaria by 1949 did not mean that house spraying ended. DDT was used in many other public health endeavors.

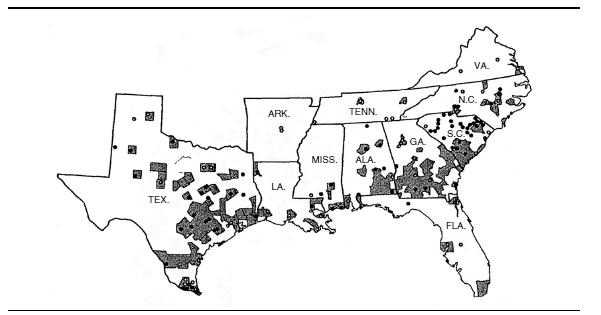

Typhus

Control of murine typhus, which was an important public health problem in southern states, was one such endeavor. Unlike epidemic typhus, which is spread by lice, murine typhus is transmitted by fleas that infest rats. The control of murine typhus was achieved by dusting rat burrows and runways with DDT to kill fleas (oriental rat fleas) (see Figures 8.2 and 8.3).34 Over time, hundreds of thousands of premises were dusted with DDT for control of this disease.

A total of 448,297 residences were dusted with DDT for typhus control in calendar year 1946.37 Dusting of premises continued for several more years and declined only when risk of murine typhus had been greatly reduced or eliminated. Examples of extensive DDT use are 1) from September 1 to November 22, 1947, when 91,083 premises were dusted,38 and 2) from March 20 to July 2, 1949, when 150,705 premises were treated.39

Figure 8.2

MAP OF COUNTIES WITH RESIDUAL DUSTING PROJECTS USING

DDT FOR CONTROL OF MURINE TYPHUS (1946 AND 1947)35

SOURCE: U.S. Public Health Service, Atlanta, Georgia, 1948.

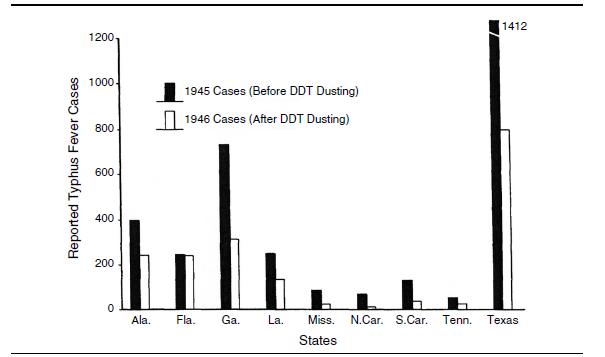

Figure 8.3

COMPARISON OF NUMBERS OF TYPHUS CASES IN U.S.

COUNTIES WITH AND WITHOUT DDT DUSTING (1945–1946)

NOTE: The comparison data for not dusting were drawn from 1945 case data.36

SOURCE: U.S. Public Health Service, Atlanta, Georgia, 1948.

Housefly and Dysentery Control

Although houseflies eventually became resistant to DDT, it was used for a time to control them successfully. Control of houseflies also helped reduce problems of dysentery. Some housefly control was a byproduct of the residual spray program for eradicating malaria. As stated in a Missouri State Health Department publication (cited in a CDC report) in 1946:

[L]ast year the U.S. Public Health Service sprayed 85,000 homes with DDT in the delta country of Mississippi. It was chiefly a malaria control project to kill mosquitoes. But so many flies died as a result of the spraying project that the infant death rate from fly-borne diseases such as dysentery, typhoid fever, diarrhea, and enteritis, was cut to less than one-third that of the year before.

This means that approximately 50 children in Mississippi who otherwise would have died as a result of these diseases are alive today.40

Aedes Aegypti Control

For many years, DDT was sprayed in towns and cities for control of the mosquito that transmits dengue fever and urban yellow fever, Aedes aegypti. Sporadic efforts to control this important vector were converted into a national eradication program in the 1960s.

The United States, along with other countries of North, Central, and South America, first signed a resolution of the Pan American Health Organization to eradicate Aedes aegypti in 1947. The United States signed a similar resolution in 1961. Funds were appropriated to initiate a U.S. eradication program in 1963.41 The CDC coordinated the program, and with rare exception, it was based on spraying DDT as a matter of official public health policy in urban residential areas. The program continued until 1969.42

Plague Control

Like murine typhus, plague is transmitted by fleas, which were controlled effectively with DDT. The insecticide was used even in areas of western Texas and in a broad swath of the western United States for dusting prairie dog colonies and ground squirrel burrows as a means of plague control.43

Scope and Intensity of Public Health Use of DDt in Texas

Most Americans living in the 21st century are likely unaware of the historic extent and severity of malaria, murine typhus, dengue, and yellow fever in the United States. Media reports of West Nile virus outbreaks or of Lyme disease may give some pause to consider the threats posed by disease-spreading insects. Public health agencies respond to these outbreaks, usually with a targeted, local intervention. Given the contemporary response to insect-borne disease outbreaks, few will appreciate the scale of the response in the 1940s and 1950s. But then for most Americans, diseases like malaria, to say little of plague and typhus, are probably viewed like sepia photographs, as curiosities of the past.

The scale and urgency of the responses to malaria and other public health threats by U.S. agencies was enormous, and none of the programs described above that used DDT were trivial in scope. Texans, not known for their timidity or modesty, were residents of just one state that used DDT on a grand scale and to great effect. We review here the sequence of public health endeavors for Texas as an example of what occurred in many disease endemic states in the mid-1940s.

Malaria in San Antonio, Texas, from 1904 to 1908 caused a death rate of 17.5 per 100,000 population. In the interval from 1909 to 1913, the rate was 13.9 per 100,000 population.44 To put these death rates into a modern framework, the rates for malaria infections alone were two- to fourfold higher than the modern death rate for all cancers combined in the 0- to 19-year age group in the United States.45 A comparison of these age groups is justified because, in 1922, the deaths of children under age 5 from malaria were several-fold more than any other 10-year age group except the elderly.46 However, malaria and other infectious diseases did more than just kill people, they also reduced their economic wherewithal.

Even in the 1940s, malaria remained a large public health problem in the United States. As stated in a 1941 update on status of malaria in the United States:

Conservative evidence indicates that malaria is today indigenous in 36 of the United States. These include all of the southeastern states (i.e., Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana); a large portion of Oklahoma and Texas; Missouri (especially the southeastern section; . . .”46

For Texas in particular, malaria remained a formidable public health problem, even in the 1940s. In 1941, the most malarious areas in Texas were “situated chiefly around the Rio Grande, Red and Sabine Rivers.”47 Public health officials believed in 1941 that malaria was “more widespread and probably more prevalent [in 1941] than in 1930.”48

Spraying houses with DDT to control malaria started at least by 1945. Between the latter half of 1945 and mid-1947, more than 200,000 houses in Texas were sprayed with DDT.49 The CDC malaria eradication program, based on DDT spraying, continued beyond 1947, but in 1948 the program was altered. As with the national program described above, spray cycles were reduced from two per year to just one per year. The amount of DDT applied to house walls was 200 mg/ft2, which is about two grams per square meter of wall surface,50 which to this day is the international standard for malaria control treatments.

The numbers of houses sprayed in Texas were 89,600 in 1947; 94,905 in 1948; and 71,870 in 1949.51 For part of 1948 and after, house spraying became less costly and better tolerated by residents because spraying was limited to one time per year opposed to the earlier strategy of spraying at six-month intervals. In 1950, a total of 85,355 houses in Texas were sprayed with DDT.52 As stated in a CDC report for July, August, and September 1952, “a total of 145,138 spray applications have been made this season.”53 Texas was one of the states that continued spraying houses in the 1950s. For example, 23,885 and 41,273 premises were sprayed in 1952 and 1953, respectively.54

Spraying continued in Texas during 1950–1953, in part because malaria was still endemic in South Korea during the Korean War, and several U.S. bases were located in Texas. With the military returning from the Korean War, the United States had to maintain vigilance to prevent large re-introductions of malaria.55

DDT also was used in many other public health endeavors in Texas, including the dusting of premises to control murine typhus. In the 1951 review of murine typhus control, public health officials concluded that “semiannual DDT dusting of rat runs and harborages in rat-infested business buildings and annual DDT dusting in the residential areas” contributed to reduction of rats and prevalence of murine typhus. All told, through those and other preventive measures, Texas reduced the incidence of murine typhus “from 1,844 cases in 1945 to 222 [cases] in 1950.”56 This was an 88 percent reduction in disease.

Aedes aegypti control was essential to halt the spread of dengue and yellow fever, and Texas and CDC initiated DDT spraying to control this mosquito in 1946.57 Spraying DDT in and around the mosquito breeding sites in backyards and next to houses continued throughout the 1940s and 1950s.58 Spraying was intended not only to control mosquito breeding but to eradicate the mosquito.

Funds were appropriated for a national Aedes aegypti eradication program in the fall of 1963.59 The CDC-coordinated program got underway in 1964. As described in a 1964 annual report, the program had two objectives:

It will protect this country against outbreaks of yellow fever and dengue, and it will eliminate this reservoir of Ae. aegypti as a possible source of reinfestation of countries that have rid themselves of the species.60

When the U.S. program was initiated in 1964, a total of 16 countries within the hemisphere had already used DDT to successfully eradicate Aedes aegypti.61 Thus, the second of the two objectives had great significance for many countries in the Americas. Simply stated, eradicating Aedes aegypti from the United States would have ended the export of the mosquito back into Aedes aegypti-free countries.

The U.S. Aedes aegypti eradication program was based on the use of DDT, and southern Texas was one of several pilot test sites. Pressure from environmental activists and resultant government actions were the proximate cause of ending the Aedes aegypti eradication program in 1969; in turn, that action was the proximate cause for the collapse of successful eradication efforts in the rest of the hemisphere. A measure of the devastating, but perhaps indirect, consequences of the 1969 decision to end the eradication effort in the United States is the nearly one million cases of dengue that occurred in Brazil in 2010.62 Furthermore, the tragedy is ongoing, with the reoccurrence of millions of cases each year in countries that were once—through use of DDT—free of dengue and the risk of urban yellow fever.

In summation, the historical record shows how DDT was heavily relied upon in public health programs in the United States. It was indubitably a key element in the successful elimination of malaria, and it was an important contributor to the control of murine typhus, dysentery, and other diseases.

DDT was saving lives in the United States when Rachel Carson was in her early 30s and was editor-in-chief of all publications for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. While her focus was not public health, the facts presented above could not have escaped her attention. This makes the dismissive attitude Carson exhibited toward the public health use of DDT, as we describe below, inexcusable.

Public Health Use of DDt Overseas

The United States was not the only country to gravitate to DDT for use in public health. Many other countries quickly put the magical white powder to work in national public health programs, especially for malaria and, in the Americas, for eradicating Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. DDT’s ability to prevent disease transmission and, in some cases, eradicate the disease vectors led a National Academy of Sciences committee in 1970 to conclude: “To only a few chemicals does man owe as great a debt as to DDT. . . . In little more than two decades, DDT has prevented 500 million human deaths, due to malaria, that otherwise would have been inevitable.”63

The effectiveness of DDT for disease control convinced various countries throughout the world to create national malaria control programs. Their successes eventually stimulated the World Health Organization to coordinate a global eradication program.

DDt and Malaria Control in the Americas

Almost all countries in the Americas started using DDT in their malaria control programs. The experiences of countries like Venezuela and Guyana demonstrate the powerful benefit of spraying house walls with small amounts of DDT. In the mid-1940s and before, malaria rates in countries in the Americas were dangerously high. Venezuela had a national malaria program but was still reporting more than 800,000 cases per year.64 Venezuela started spraying DDT in houses in 1946. The protection was immediate, and malaria rates dropped precipitously in all sprayed areas. From the period 1941–1945 (pre-spray period) to 1948, DDT spraying reduced the number of malaria positive slides per 100,000 people from an average of 1,083 to just 82 for 1948, a 91.25 percent drop in malaria.65

In the neighboring country of Guyana, during 1943–1945, more than 37 percent of the rural population and 27 percent of the urban population were stricken with malaria. Accompanying these high infection rates was a death rate among newborns of 126 per 1,000 live births. Guyana started experimental spraying of DDT inside houses in 1945, expanded the program in 1946, and initiated countrywide spraying in 1947.66 By the 1948–1949 time period, as a result of house spraying alone, infant mortality declined by 39 percent.67 In urban areas, malaria declined by 99 percent. Even in the highly endemic rural areas, malaria infections declined by a stunning 96 percent.68

By the early 1950s, both Venezuela and Guyana had used DDT to eliminate malaria from large areas.69 Soon malaria infections could be found only in sparsely populated forested areas of both countries. Malaria completely disappeared from heavily populated coastal regions and from much of the interior savannas.

Health workers in other countries also recognized the particular value of DDT. The head of malaria control in Brazil characterized the changes that DDT offered in the following statement:

Until 1945–1946 [when DDT became available for malaria control], preventive methods employed against malaria in Brazil, as in the rest of the world, were generally directed against the aquatic phases of the vectors (draining, larvicides, destruction of bromeliads, etc. . .). These methods, however, were only applied in the principal cities of each state, and the only measure available for rural populations exposed to malaria was free distribution of specific drugs.70

In the late-1950s, under guidance from the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization, most national malaria programs were converted into malaria eradication programs.

DDt in National Malaria Control Programs in Africa and Asia

Historical data from many countries outside the Americas also show the huge beneficial impact of spraying houses with DDT. As documented here, many countries started their own malaria control programs. These countries, like those in the Americas, pioneered house spray methods, and laid the groundwork for what would become a WHO-coordinated global malaria eradication program.

Africa

The vector control programs in southern Africa adopted DDT shortly after the end of WW II. Residual spraying with DDT brought rapid reductions in the number of malaria cases. In the Transvaal province of South Africa, hospital admissions “fell from 1,177 cases during the 1945–1946 transmission season to 601 in 1946–1947 coinciding with the availability of DDT in 1946, and falling to 454 in 1948 and to a low of 61 cases in 1951.”71 Similar successes were echoed in other southern African countries where DDT was used. While DDT resulted in plummeting malaria rates in many parts of southern Africa, the spraying programs were not scaled up in most of the highly endemic areas of central Africa where health infrastructure was poor and levels of development remained low. However, it is safe to assume that had donor countries, and the governments of malarial countries, invested in such projects, the impacts would have been dramatic. According to World Health Organization data, pilot projects of DDT spraying combined with distribution of chloroquine in the Kigezi district of Uganda reduced malaria parasite prevalence from 22.7 percent to 0.5 percent between 1959 and 1960. In southern Cameroon, parasite prevalence among children was reduced from 28.5 percent to just over 5 percent in one year using DDT alone.72 WHO reports that equally impressive results were achieved in other countries of the region.

Sri Lanka

After DDT was introduced for control of malaria in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) in 1946 and over a three-year period, the spleen rate (malaria infections cause enlarged spleens) dropped from 77 percent to 2.7 percent, and general infant mortality dropped by 62 percent.73 By 1954, infections had declined from 413 per 1,000 to 0.85 per 1,000 people.74 These statistics reveal reductions in millions of malaria cases per year.

Taiwan

The newly-formed Republic of China (Taiwan) adopted DDT use in malaria control shortly after World War II. In 1945, there were more than one million cases of malaria on the island; by 1969, there were only nine cases.75 Shortly thereafter, the disease was eradicated from the island (and remains eradicated today).76

In summary, extensive use of DDT for malaria control preceded the global eradication program. As shown by the statistics presented above, countries used DDT to combat malaria and greatly improved the health of their residents. Over a third of a billion people were freed of endemic malaria even before the WHO-led eradication effort began.77

DDt and WHO’s Global Malaria Eradication Program

The 8th World Health Assembly in 1955 directed WHO to coordinate a global program to eradicate malaria. As revealed in statistical reports of malaria eradication in the Americas, the program was fully underway in 1959.

Nepal was just one of several countries that benefited from malaria eradication. One report noted that “dramatic, nationwide reduction of malaria [in Nepal] was perhaps the greatest technical and logistic triumph of the 1960s.”78 That triumph over malaria was based largely on use of DDT as the exclusive preventive measure of the eradication program.

Each year in the early 1950s, there were more than two million cases of malaria in Nepal, with a mortality rate of 10 percent. The burden of deaths fell most heavily on children. At that time, malaria was Nepal’s most serious public health problem, and it contributed to increased deaths from other diseases as well. The U.S. Agency for International Assistance started the malaria program in Nepal in 1959. Spraying of houses in the central zone began in 1960. Spraying in the eastern zone was underway in 1964 and in the western zone in 1965.79

Whereas previously more than two million cases of malaria a year had been the norm, only 2,468 cases were found in 1968. Before the malaria control program, life expectancy in Nepal was 28 years. By 1962, life expectancy was 33 years, and by 1970 it was 42.3 years.80 Malaria in Nepal had been an enormous problem in many areas—so bad that it had prevented people from occupying land and producing crops. Once malaria was brought under control, previously unoccupied areas became available for agricultural productivity. As land became available, large numbers of people moved into new areas. The total cost of the multiyear program in Nepal was a mere $13 million, which brought vast improvements in health, dramatically reduced death rates and increased population longevity, and ultimately, vastly increased agricultural productivity and wealth.81

All told, from the mid-1940s to 1969, almost one billion people worldwide were freed from endemic malaria by DDT-sprayed house walls.82 This achievement is unequaled in the history of arthropod-borne disease control. DDT was used to change the global distribution of endemic malaria. In those countries that coupled malaria eradication with economic growth and development, the disease remained banished after spraying stopped.

Today this eradication program is often referred to, disparagingly, as a public health failure. One cannot, of course, deny that the program failed to eradicate the disease from the entire planet and thus did not achieve its ultimate goal. But characterizing the program as a failure ignores the fact that well over a billion lives were spared the burden of endemic malaria, an extraordinary success by any measure. However, DDT did more than just save lives. Life expectancy for people in Nepal grew from 28 years before DDT to 42.3 years by 1970. The house spray program produced, on average, an extension of 14.3 years of human life. The population of Nepal in 1970 was 11.232 million.83 That value times 14.3 years of improved longevity equates to 160,617,600 additional years of human life. And these statistics describe how DDT improved health and life for people of just one country. These simple statistics reveal how the offhand and cheap dismissal of the global malaria eradication program does a grave disservice to the thousands of hard working professionals who were involved in the program. They should instead be lauded; millions of people are alive today thanks to their efforts.

Rachel Carson and DDt for Public Health

Carson would have known of the great public health achievements of DDT and that it was saving lives; indeed she describes some of the programs in Silent Spring. But the bulk of the book is a singular attack on DDT and other insecticides with scarcely any recognition of their actual and potential benefits. Although Carson didn’t actually call for a ban on DDT, it happened nonetheless, thanks to a ruling by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA ban on most uses of DDT allowed its use only in emergencies in the United States—and of course EPA has no jurisdiction in other countries. Nevertheless, disease control programs in developing countries that relied on DDT were shut down. If unintended consequences are defined as outcomes that are unexpected, then we must emphasize that the devastating harm to malaria programs cannot be accurately described as an unexpected consequence of EPA’s action. Historical records show EPA was firmly and repeatedly warned by top public health officials of the United States, the WHO, and the Pan American Health Organization of disastrous consequences of a DDT ban.84 The EPA administrator ignored those warnings and banned DDT anyway. The movement against the public health use of DDT was, in most ways, a direct result of environmental activist pressure against insecticides. In the wake of this activism, lives have been lost, and the struggle to improve human health and well-being has suffered setbacks.

Given her iconic status within the environmentalist movement and the importance of Silent Spring in the fight to ban the use of DDT, it is tempting to blame Carson for the problems that befell malaria control programs as a result of anti-DDT activism. That would be too easy, however. Carson died eight years before the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued its ruling—seen as laudable by some, notorious by others—banning most uses of DDT. Carson states in Silent Spring that it is not her contention “that chemical insecticides must never be used.”85 Toward the end of Silent Spring, in Chapter 16, Carson explains that mosquitoes transmit diseases like malaria and yellow fever and states:

The list of diseases and their insect carriers, or vectors, includes typhus and body lice, plague and rat fleas, African sleeping sickness and tsetse flies, various fevers and ticks, and innumerable others. These are important problems that must be met. No responsible person contends that insect-borne diseases should be ignored.86

These statements, while accurate and important, stand almost alone in over 250 pages vilifying insecticides and generating great fear about modern chemicals, and DDT in particular. The problem we have in excusing Carson’s role in the banning of DDT is that she dismisses the great achievements that resulted from using DDT, and she also gets some basic facts and theories wrong. For these, she can and must be blamed.

Understandably, Silent Spring deals mostly with the agricultural use of insecticides such as DDT. The control of crop pests consumed vastly greater amounts of insecticide than the targeted use of insecticides in public health. Carson was also primarily concerned with the effects of insecticides on wildlife, and as spraying insecticides inside houses results in almost no biologically significant environmental contamination, this use would interest her less. However, as most of the book discusses DDT, it is curious that she ignores the most important use of DDT, from a humanitarian perspective, until one of the final chapters.

Readers of Silent Spring will go through many pages of Carson’s lyrical prose describing one horrifying consequence of using DDT after another. Her words are well chosen to strike fear into any reader’s heart as she describes her speculations about insidious harm to both man and wildlife from the use of modern pesticides. Not until Chapter 15, “Nature Fights Back,” does Carson explain that DDT was used in the South Pacific during World War II to control malaria. Unlike the concentration camp survivor quoted earlier, however, she does not dwell on the life-saving properties of DDT; the reason she brings up this example is to claim that the mosquitoes soon developed resistance to the insecticide.

Her treatment of disease control programs in Chapter 16, “The Rumblings of an Avalanche,” is equally designed to claim that using insecticides like DDT will actually make disease control harder. Carson continues the quotation from above, with this:

The question that has now urgently presented itself is whether it is either wise or responsible to attack the problem by methods that are rapidly making it worse. The world has heard much of the vectors of infection, but has heard little of the other side of the story—the defeats, the short-lived triumphs that now strongly support the alarming view that the insect enemy has been made actually stronger by our efforts. Even worse, we may have destroyed our very means of fighting.87

Later (on page 233), Carson describes the famous use of DDT in Naples, Italy, to control typhus during World War II. Again her reason for describing the usefulness of DDT against body lice is merely to claim that eventually lice developed resistance.

Throughout the book, Carson dismisses the beneficial uses of DDT. In the final paragraphs of Chapter 13, “Through a Narrow Window,” she describes the potential for chemicals to lead to genetic mutations and “strike directly at the chromosomes. . . .”88 Carson concludes this paragraph with, “Is this not too high a price to pay for a sproutless potato or a mosquitoless [sic] patio?”89 Though Carson doesn’t finger DDT as one of the chemicals in this passage, she refers to it elsewhere in the chapter and throughout the book, and it can be taken that DDT was one of the chemicals to which she was referring. The problem with her statements is that at the time she was writing Silent Spring, as now, there is no evidence that DDT acts in this way and “strikes directly at the chromosomes.” While Carson was writing this passage, millions of people were being saved from diseases and were enjoying a longer lifespan, better nutrition, and as a result, a brighter future, thanks to the chemicals she attacks. Yet Carson trivializes these benefits and stokes up fears for which she had little or no evidence.

Unfortunately, Silent Spring is littered with inaccuracies about the way in which DDT works and the biology of insecticide resistance. In her defense, Carson was not alone in misunderstanding the way that DDT functions. However, given that so much of the book is devoted to DDT, this is hardly an excuse.

From the very early uses of DDT in disease control in the 1940s and ever since, scientists and field workers have reported in the peer-reviewed literature and elsewhere that DDT functions as a powerful spatial repellent.90 In other words, DDT stops mosquitoes from entering sprayed houses. In addition to these spatial repellent properties, DDT also acts as a contact irritant so that if a mosquito lands on a surface sprayed with DDT, it will quickly move away. Lastly, DDT also acts as a toxicant, and if exposed to the chemical long enough, the mosquito will die.

These three powerful modes of action are unique among public health insecticides; no other chemical used in malaria control functions in these ways. For these reasons and others, public health professionals value DDT and its remarkable ability to keep disease spreading insects away from people, thereby interrupting transmission of parasites and other disease agents, and saving lives.

Carson, like others, eagerly noted the spatial repellent properties of DDT, explaining, “Some malaria mosquitoes have a habit that so reduces their exposure to DDT as to make them virtually immune. Irritated by the spray, they leave huts and survive outside.”91 Carson was not a medical entomologist and perhaps could be forgiven for misinterpreting the results of DDT spraying; indeed some entomologists and public health professionals fell into the same trap.

The major species of malarial mosquitoes have evolved their patterns over the millennia to feed on humans inside their houses, normally late at night. The fact that disease-spreading mosquitoes exit houses and are kept away from people means that they are no longer transmitting the malaria parasite; this breaks the disease transmission cycle. The evidence from countless malaria programs around the world, over many years, shows that as a result of the spraying, malaria rates plummet. Carson thought that she found some Achilles’ heel of the DDT malaria programs, when in fact she described one of its strongest attributes.

Carson focused on insecticide resistance because she seemed to view it as a cunning way to turn public health triumphs into potential disasters. Insecticide resistance is a problem for vector control programs. In a similar way, resistance to antibiotics is also a serious and ongoing medical problem. In the face of resistance to medicines, however, few people argue that we should eschew them altogether. Rather, well-publicized, well-funded, and popular campaigns seek to invest both public and private funds in the search for new drugs. Although insecticides, when used in public health, save lives just as medicines do, they do not benefit from the same kind of popular support and funding. This has much to do with the negative view that most people have of modern chemicals, thanks in large part to Silent Spring and fear mongering of anti-insecticide advocacy.

Notably, Carson fails to explain that in almost all cases, mosquito resistance to DDT did not result from its use in public health, but from chemical use in agriculture. Resistance in a population is driven by mortality. As the susceptible insects die, those with the resistant genes survive and gradually dominate in the population. Because DDT is, in fact, a weak toxicant and mainly functions as a spatial repellent when used for malaria control, the mosquitoes often do not die from their exposure to DDT. Therefore, the resistant gene is not driven through the population via the force of selective mortality. This is important because then, as now, insecticide resistance is used as an argument against DDT and indeed against other insecticides.

In several instances, Carson writes that as mosquitoes develop resistance to DDT, they become “tough” and that “a process of escalation has been going on in which ever more toxic materials must be found.”92 Carson relies on Darwinian evolution to explain that the use of insecticides results in the survival of the fittest. Yet her understanding of this topic was weak. The mosquitoes are not more “tough,” they are more resistant to a given chemical, and in the absence of that chemical, they are no more fit to survive than nonresistant mosquitoes. In fact, in the absence of the chemical, the mosquitoes may even be less fit than others.

Carson is also wrong in her assessment that resistance requires “ever more toxic materials.” This statement can only be designed to frighten readers, who would rightly be worried about more and more dangerous chemicals in the environment. In reality, the presence of resistance does not call for ever more toxic chemicals; it calls for chemicals that have different modes of action and act differently on the insect. Malaria control professionals now largely agree that combining different insecticides in spraying programs and/or rotating spraying with different classes of chemicals, is a useful means of stopping the spread of resistance through a population. This same principle holds true for management of drug resistance. The modern protocols for the treatment of malaria and other diseases, like tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS, call for combinations of different drugs with different active ingredients.

Silent Spring may have gotten these basic fundamentals wrong, but such was the power of the book that it started a renewed push for the use of biological, supposedly environment-friendly methods of disease control. The final chapter, “The Other Road,” lays out Carson’s vision for a world free of man-made chemicals. Since her death, public health policies have been greatly influenced by her agenda and the idea of insecticide-free malaria control. Despite a dearth of evidence to support this idea, it remains alive and well and continues to undermine malaria control and thereby cost lives. Also, emphasis on biological control has diverted precious resources from the development of new and improved public health insecticides and from research to improve the methodology of chemical use. Instead, those resources have gone to a single-minded program of research aimed at demonstrating efficacy of nonchemical methods of disease control. We cannot blame Carson for changes in public health policy enacted by the global health bureaucracies after she died. However, as countless environmental groups celebrate and almost sanctify Carson’s legacy, it is useful to examine her anti-insecticides legacy with respect to global public health.

Changing Public Health Policies

In May 1970, two years before EPA banned DDT and six years after Carson’s untimely death, the World Health Assembly, the governing body of the World Health Organization, met in Geneva and debated malaria. The WHA sets the agenda for WHO and represents the interests of ministers of health from around the globe. The 1970 WHA adopted a resolution on malaria, which includes a statement recognizing the importance of insecticides for effective control of malaria.93 Furthermore, the WHA urged “the countries manufacturing insecticides to continue to make available to the developing countries insecticides for malaria control.”94 These basic statements were presumably encouraging to malaria control program managers in developing countries who were already seeing growing opposition to the use of DDT and were no doubt deeply concerned about the increasing pressure not to use insecticides—and DDT in particular.

These issues had played out several months prior to the WHA at the WHO executive board meeting in January 1970. During this meeting, a report was presented from WHO’s Regional Committee for South-East Asia. The regional committee had adopted a resolution “which encouraged countries producing DDT to continue to do so until a less toxic and equally effective insecticide became available.”95

The minutes of the executive board include the following:

Dr. Layton [Canada’s representative] said he had been struck by a series of statements made on the question of DDT all within a brief space of time. In the first place, the Director-General [of WHO], in his introduction to Official Records No. 179 (page XVII), had stressed the desirability of continuing to use DDT for malaria eradication. Almost simultaneously, the Canadian Prime Minister [Pierre Trudeau], in a formal statement on the matter, had said that research showed the environment to be widely contaminated by DDT residues; while there was no evidence that the present levels of DDT in the diet had caused injury to humans, it was only prudent, in view of the persistent use of DDT and the lack of clear-cut evidence, to limit contamination of the environment.96

Thus, despite the clear and unambiguous need for DDT voiced by public health experts—including WHO’s director general—Canada’s representative invoked the “precautionary principle” and advocated against the use of DDT. This would not be the last time that developed countries and anti-insecticides groups would use official meetings of WHO to push their agenda, even if it went against the views of disease control experts and undermined malaria control.

The malaria control specialists pushed back against this anti-insecticide activism. One year later, WHO’s Expert Committee on malaria issued its 15th report, which included a resolution stating that the committee recommended . . . “that every effort be made to ensure the continued availability of residual insecticides, particularly DDT, for malaria eradication, which is an essential health activity.”97

However, in a reflection of the growing popular opposition to DDT, by 1972 WHO was subjected to growing criticism in the media for its support of DDT use. The 1972 report, The Work of WHO, reflects the ideological importance of insecticide use. WHO states:

Press cuttings received in 1972 amounted to roughly twice the volume received in 1971. A considerable increase in press coverage of WHO activities was achieved, especially in the African Region. Comment on WHO continued to be largely favourable. Such criticism as was noted related to the Health Assembly’s action regarding the German Democratic Republic [East Germany] and WHO’s position on DDT.98

The report goes on to explain that WHO was counteracting the criticism on DDT and had held a televised debate in the United States, which concluded favorably for the use of DDT in developing countries until a suitable substitute could be found. Notably, the debate about the use of DDT appears to have been as important and controversial for the media as the great ideological battles of the Cold War.

WHO’s technical health specialists continued their defense of DDT, but in many respects, this defense became quixotic. DDT production dwindled, and prices rose after EPA’s 1972 ban (an outcome EPA had been judiciously warned would occur). DDT became increasingly difficult to acquire for use in malaria programs. At the same time, the cost of developing new insecticides kept rising, and the prospect of a new public health insecticide dimmed. By the mid-1970s, WHO understood this well, stating:

The number of new pesticides received in 1975 for evaluation by WHO for use in vector control was considerably lower than in previous years. The great increase in the cost of developing and testing new chemical pesticides has caused industry to limit the number of compounds being developed to those which can be shown to have wide potential use in agriculture as well as in public health.99

The report goes on to explain that “much attention is now being paid to the ecology of vectors and animal reservoirs, the fate of pesticides in the environment and their effects on nontarget species, and the feasibility of using biological or other nonchemical means of control.”100

In his report to the WHO executive board in May 1976, Dr. Jacques Hamon, director at the time of WHO’s Division of Vector Biology and Control, noted that “regrettably, costs of research and development of new products had increased to such an extent that the chemical industry had reduced its research efforts on pesticides because the prospects of recovering the investment by marketing new insecticides were also decreasing.”101

By the late 1970s, WHO began to include biological and environmental controls as more mainstream strategies for malaria control. The 1976–1977 report, The Work of WHO, states:

In recent years vector control has been achieved mainly through the use of chemicals. This approach has given rise to problems such as pesticide resistance, hazards to non-target organisms including man, and environmental contamination. A program of research is now underway to develop better chemical and non-chemical methods of control. The Organization carried out a review of the situation and prepared a statement on pest/vector management systems in collaboration with [the U.N. Environment Programme] and WHO.102

Insecticide resistance was and is a real and pressing problem. However, the impact of resistance to DDT was no doubt overstated because of DDT’s spatial repellent properties. Regardless, the solution to resistance is not to stop the use of pesticides, but to find new pesticides and ensure that resistance is managed and contained. Unfortunately, although development of new public health insecticides is the proper solution, that avenue was blocked by anti-insecticide activism. Instead, efforts were directed at avenues of research that were destined to fail, namely methods of environmental management and biological control. Throughout this period, malaria control based on the sound and effective use of public health insecticides gradually unraveled. In the meantime, layer upon layer of new costs were piled onto research and development of new insecticides, making discovery of a new public health insecticide more and more unlikely. All of this occurred as a direct consequence of the ever-growing influence over disease control by environmental agencies and environmental activists.

During the 1985 75th WHO executive board meeting, Dr. Norman Gratz, WHO’s then-director of the Division of Vector Biology and Control, recognized that chemicals would remain “the mainstay of vector control in the developing and developed world for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, substantial resources had been transferred to biological control; in addition the program had received additional funding through its collaboration with the Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, which would be used for the development of biological control methods and materials.”103 These methods were to include fish in the control of mosquito larvae.

Regrettably, WHO bowed to the increasing public pressure and pressure from the developed nations that pay WHO’s bills. WHO began withdrawing support for DDT and other insecticides in public health. As an organization reliant on donations, WHO also began chasing the money, which by then was flowing towards environmental control and away from insecticides. No one can blame Carson for WHO’s failings, but based on content of Silent Spring, it is fair to say that she would have been pleased with this outcome.

As described in the preceding paragraphs, since the 1970s, numerous WHO reports104 have emphasized the use of biological and other environmental controls. Yet, despite decades of research and funding, the evidence that these methods are able to contribute meaningfully to disease control is largely absent. The 1980 review of malaria control for WHO’s executive board includes a statement that unequivocally points to the growing power of the anti-insecticides movement: “. . . in some countries where coordinated insecticidal spraying could be important in the control of malaria there has been political pressure to restrain its use, although malaria could be seen as an environmental polluter.”105

In 1997, the anti-insecticides movement achieved a significant victory, lobbying strongly for a WHA resolution that called on countries to reduce their reliance on insecticides for public health. Consumers International, a leftist group opposed to insecticides, made presentations during the WHO executive board meeting prior to the WHA. We can find no record of any presentation by disease control specialists at this meeting. The UNEP, which began collaborating with WHO in the 1970s, had apparently succeeded in keeping out anyone with actual experience in controlling disease-spreading insects while allowing in activists with an ideological opposition to insecticides.

Roll Back Malaria, a partnership among various UN agencies, including WHO, as well as donor agencies and the World Bank, developed its Global Malaria Action Plan in 2008. After decades of research on and funding for environmental and biological controls to prevent malaria, the undeniable truth remains that public health insecticides are needed and form the foundation of malaria control. The main methods of delivering these insecticides are either to spray them inside houses or to provide insecticide treated bed nets, under which people sleep. GMAP includes environmental management and biological controls but notes that “their sustainability relies on the ability to conduct continuously reliable surveillance and mapping activities to identify areas where these interventions are most appropriate.”106

Investment, both public and private, in the search for new public health insecticides has been totally inadequate, largely as a result of Carson’s agenda and the growing expense of insecticide development. By comparison, the much-needed funding for new malaria treatments and even for a malaria vaccine has been substantial. In 2004 alone, malaria vaccine development received almost $80 million in funding, and in that same year the search for new malaria drugs received $120 million.107 A recent report published by the Program for Appropriate Technologies in Health reveals that the annual investment in research and development (R&D) for new tools to fight malaria quadrupled between 1993 and 2009 to a level of $612 million. Even though malaria is a vector-borne disease that requires vector control measures, between 2004 and 2009, only 4 percent of total R&D expenditures was devoted to vector control; most funds went toward the search for vaccines and new medicines.108 Included in that 4 percent was funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for the Innovative Vector Control Consortium. That is the only partnership to discover new public health insecticides, and in 2005 it was granted $50 million over a five-year period. While this is a valuable initiative, regrettably the consortium is not investigating or developing any chemicals with the spatial repellant action exhibited by DDT. The prospects of finding a true replacement for DDT, therefore, are slim.

Regulatory barriers and the costs of developing medicines and vaccines have risen, just as they have with insecticides. However, unlike insecticides, WHO, other health agencies, charities, foundations, advocacy groups, and the private sector have successfully lobbied for funding. And unlike insecticides, there is no organized, effective, and richly funded opposition to medicines and vaccines.

Environmental and biological controls—the preferred path sketched out by Rachel Carson in Silent Spring—have failed to provide any credible method of controlling malaria and thereby saving lives. Naturally, the modern day individuals and groups that have taken up Carson’s anti-insecticide crusade claim great successes in insecticide-free malaria control. But these groups, including Pesticide Action Network and the UNEP, hide behind a thin veil of misinformation and are particularly damaging to serious disease control efforts—which require new and effective public health insecticides.

An excellent example of the way in which the success of environmental control of malaria is not only exaggerated, but fabricated, is found in a malaria project in Mexico and seven Central American countries funded and managed by UNEP and the environmental health unit of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). With funding from the Global Environment Facility, UNEP and PAHO set out to show that malaria could be controlled without DDT and indeed without any insecticides. After the completion of the project, in 2008, UNEP, GEF, and the environmental sector of PAHO claimed that their environmentally sound approaches reduced malaria by more than 60 percent. Malaria had declined in these countries, but as we explained in a peer-reviewed paper,109 the decline was due to the widespread distribution of malaria treatments and totally unrelated to UNEP’s efforts. In fact, an epidemiologic review of the UNEP project showed that its environmentally sound methods made absolutely no difference to the transmission of malaria.

Almost 70 years after it started saving lives in war-torn Europe, DDT is still being used in malaria control, mostly in southern Africa and India. The great irony of the anti-DDT and anti-insecticides campaign started by Carson and carried forth by so many others, is that while dampening research into new public health insecticides and diverting resources into a fruitless quest for biological controls, WHO continues to recommend DDT as one of the few effective vector control insecticides. And several malaria programs have few options other than to use it.

Conclusion

Unlike some environmental writers and doomsayers of the time, such as William Vogt or Paul Ehrlich, Carson never advocated against disease control and never specifically suggested that people in poor countries should die to arrest population growth. But Carson did get her facts wrong. And though she may not have intended to harm people suffering from insect-borne diseases, her ideas, as mistaken as they were, have inflicted great and lasting harm. As we have explained in this chapter, the evidence of the great and unprecedented way in which DDT helped save lives and lift people out of the misery of poverty and disease was overwhelming. Carson should have known better than to disparage the disease control successes and use false arguments against insecticides.

Today, we still rely on DDT, and in spite of the political risks to governments involved, it is still being produced and used in malaria control programs. Carson’s scare tactics produced great fears about insecticides, which led to a dearth of investment in new public health insecticides to replace DDT. The ultimate irony is that DDT remains a valuable and necessary tool in our malaria control arsenal precisely because no legitimate DDT replacement has been found. And this, in turn, is a consequence of Carson’s anti-insecticide advocacy.